FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Modtech Engineering Pty Limited v GPT Management Holdings Limited [2013] FCA 626

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

MODTECH ENGINEERING PTY LIMITED (ACN 006 993 022) Applicant | |

AND: | GPT MANAGEMENT HOLDINGS LIMITED (ACN 113 510 188) First Respondent GPT RE LIMITED (ACN 107 426 504) Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to further order, pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act), and on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the following evidence is to remain confidential on the Court file and is not to be disclosed to any other parties or persons without the express consent of the parties or order of this Court:

(a) the Affidavit of Benjamin James Yang Phi affirmed on 13 June 2013 and its annexures;

(b) the Affidavit of Benjamin James Yang Phi affirmed on 19 June 2013 and its annexures; and

(c) paragraph 8 of the Affidavit of Benjamin James Yang Phi affirmed on 19 June 2013.

2. By 4:00pm on 25 June 2013, the parties file a minute of proposed orders together with an amended Settlement Distribution Scheme to give effect to these reasons for judgment.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1408 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | MODTECH ENGINEERING PTY LIMITED (ACN 006 993 022) Applicant

|

AND: | GPT MANAGEMENT HOLDINGS LIMITED (ACN 113 510 188) First Respondent GPT RE LIMITED (ACN 107 426 504) Second Respondent

|

JUDGE: | GORDON J |

DATE: | 21 JUNE 2013 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 This proceeding is a “shareholder class action” commenced pursuant to Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act).

2 The applicant, Modtech Engineering Pty Limited (Modtech), a former holder of stapled securities in the respondent companies (collectively GPT), brought the proceeding on its own behalf and on behalf of persons who purchased GPT securities between 27 February 2008 and 6 July 2008 (the Relevant Period) and continued to hold those securities after that date.

3 Modtech alleged that, by reason of various matters, a forecast issued by GPT on 27 February 2008 overstated the distributions per security (DPS) expected in 2008 and, as a result, securities purchased during the Relevant Period were purchased at an inflated price. Modtech alleged various matters affecting the likelihood of GPT achieving the stated DPS should have been disclosed. When GPT issued a downgrade on 7 July 2008, its security price fell. Modtech alleged it suffered loss. GPT denied they are liable to Modtech or to any group member and denied that Modtech or any group member was entitled to the relief sought or any other relief.

4 The trial of the proceeding was heard over 16 days between 6 March and 9 April 2013. Judgment was reserved.

5 On 8 May 2013, the parties notified the Court that they had agreed terms of a proposed settlement and a Settlement Deed. Under the Settlement Deed, GPT will pay a Settlement Sum of $75 million, inclusive of interest and legal costs. The parties to the Settlement Deed were Modtech, GPT, Slater & Gordon Limited (Slater & Gordon) and Comprehensive Legal Funding LLC (ARBN 132 369 003) (CLF). CLF provided commercial litigation funding to Modtech for the proceeding.

6 Modtech has filed an application seeking approval of the compromise pursuant to s 33V of the Act.

RELEVANT LAW

7 Section 33V of the Act forms part of the statutory scheme established by Pt IVA which regulates what are described as “representative proceedings” but are generally known as “class actions”. Section 33V provides as follows:

Settlement and discontinuance—representative proceeding

(1) A representative proceeding may not be settled or discontinued without the approval of the Court.

(2) If the Court gives such an approval, it may make such orders as are just with respect to the distribution of any money paid under a settlement or paid into the Court.

8 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chats House Investments Pty Ltd (1996) 71 FCR 250 at 258 Branson J said the following of s 33V:

The purpose intended to be served by s 33V(1) is obvious. It is appropriate for the Court to be satisfied that any settlement or discontinuance of representative proceedings has been undertaken in the interests of the group members as a whole, and not just in the interests of the applicant and the respondent. …

9 In Lopez v Star World Enterprises Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 104 Finkelstein J described the task of the Court, to ascertain whether the compromise is a fair and reasonable compromise of the claims made on behalf of the class members as a whole, as “onerous”: at [16].

10 In Williams v FAI Home Security Pty Ltd (No 4) (2000) 180 ALR 459 at [19], Goldberg J observed:

Ordinarily the task of a court upon an application such as this, is to determine whether the proposed settlement or compromise is fair and reasonable, having regard to the claims made on behalf of the group members who will be bound by the settlement. Ordinarily in such circumstances the court will take into account the amount offered to each group member, the prospects of success in the proceeding, the likelihood of the group members obtaining judgment for an amount significantly in excess of the settlement offer, the terms of any advice received from counsel and from any independent expert in relation to the issues which arise in the proceeding, the likely duration and cost of the proceeding if continued to judgment, and the attitude of the group members to the settlement.

11 His Honour referred to a nine-factor test adopted in the United States in considering whether to approve settlements as fair and reasonable. The nine factors were: (1) the complexity and duration of the litigation; (2) the reaction of the class to the settlement; (3) the stage of the proceedings; (4) the risks of establishing liability; (5) the risks of establishing damages; (6) the risks of maintaining a class action; (7) the ability of the defendants to withstand a greater judgment; (8) the range of reasonableness of the settlement in light of the best recovery; and (9) the range of reasonableness of the settlement in light of all the attendant risks of litigation.

12 In Darwalla Milling Co Pty Ltd v F Hoffman-La Roche Limited (No 2) (2006) 236 ALR 322 at [50], Jessup J observed:

It is not, I consider, the court’s function under s 33V of the Federal Court Act to second-guess the applicants’ advisers as to the answer to the question whether the applicants ought to have accepted the respondents’ offer; the court’s function is, relevantly, confined to the question whether the settlement was fair and reasonable. There will rarely, if ever, be a case in which there is a unique outcome which should be regarded as the only fair and reasonable one. In settlement negotiations, some parties, and some advisers, tend to be more risk-averse than others. There is nothing unreasonable involved in either such position and, under s 33V, the court should, up to a point at least, take the applicants and their advisers as it finds them. Neither should the court consider that it knows more about the group members’ businesses than the applicants, or more about the actual risks of the litigation than their advisers. So long as the agreed settlement falls within the range of fair and reasonable outcomes, taking everything into account, it should be regarded as qualifying for approval under s 33V.

(Emphasis in original.)

Jessup J proceeded on a different basis from Goldberg J. His Honour observed at [33] that each case should be dealt with on its own particular merits and stated at [35] that he could see no particular warrant for incorporating into Pt IVA the requirements or rules of an overseas jurisdiction: see also Taylor v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 2008 at [58]-[64].

13 In Haslam v Money For Living (Aust) Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) [2007] FCA 897 at [20] I expressed the view that Goldberg J’s analysis:

… provided and continues to provide a useful guide in considering applications for approval under s 33V … It should, in appropriate cases and subject to the circumstances of any particular case, continue to be employed as a useful guide.

I remain of that view.

14 Recent cases have restated these as applicable principles: see eg Richards v Macquarie Bank Limited (No 4) [2013] FCA 438; Hadchiti v Nufarm Limited [2012] FCA 1524; Brisbane Broncos Leagues Club Ltd v Alleasing Finance Australia Pty Limited (No 2) [2012] FCA 1112; Kirby v Centro Properties Ltd (No 6) [2012] FCA 650; Hobbs Anderson Investments Pty Limited v Oz Minerals Limited [2011] FCA 801 and Pharm-a-Care Laboratories Pty Ltd v Commonwealth of Australia (No 6) [2011] FCA 277.

ANALYSIS

Constitution of the Court

15 Where a representative proceeding has been heard and judgment is reserved (as in the present case), the proper course is that the trial judge should only hear an application pursuant to s 33V with the consent of the parties: Dorajay Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Leisure Limited [2009] FCA 19 at [4]-[9]. Here, the parties consented to that course.

The proposed settlement

16 There are two aspects to the proposed settlement – payment of the Settlement Sum under the Settlement Deed and what is described as the “Settlement Distribution Scheme”. Each will be considered in turn.

Settlement Sum under the Settlement Deed

17 Substantial material in support of the application for approval has been provided to the Court. That material demonstrated the fairness and reasonableness of the payment of the Settlement Sum as the compromise between group members and GPT. In particular, confidential opinions from experienced, competent and respected solicitors and counsel that the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable and in the interest of group members as a whole have been filed with the Court. Those opinions have been considered. The opinions addressed the factors identified in [11] above. As the trial judge of the substantive proceeding, the opinions refer to and reflect the various issues and difficulties associated with the factual and legal issues in those proceedings which occupied the 16 hearing days. Those issues and difficulties are in addition to, and to some considerable extent, amplified by the fact that if the proceedings were to go to judgment, appeals were inevitable. Although the opinions are not determinative, they individually and collectively provide a strong basis for concluding that the payment of the Settlement Sum under the Settlement Deed is fair and reasonable for group members as a whole. For those reasons, I would approve the settlement on the basis that the payment of the Settlement Sum under the Settlement Deed is fair and reasonable for group members as a whole.

18 The Settlement Deed is confidential. It provides that the Settlement Sum is to be distributed in accordance with the Settlement Deed and the “Settlement Distribution Scheme”. It is to that document, the Settlement Distribution Scheme, I now turn.

Settlement Distribution Scheme

19 The Settlement Distribution Scheme establishes the procedure for distributing the Settlement Sum to group members if approval is granted by the Court. Initially, confidentiality was claimed in respect of the Settlement Distribution Scheme. At the hearing, Counsel for the Applicant accepted that upon approval of the payment of the Settlement Sum under the Settlement Deed, there was no longer any reason to maintain confidentiality in respect of the Annexure to the Settlement Distribution Scheme. Counsel accepted that the balance of the document was not confidential. As these reasons for judgment will explain, an amended Settlement Distribution Scheme will need to be prepared and provided to the Court.

Group Members, Funding and Legal Costs Agreements

20 Before turning to some aspects of the Settlement Distribution Scheme, certain facts should be stated. Approximately 92% of group members (including Modtech) executed a Litigation Funding Agreement (LFA) with CLF to fund the proceedings. The 92% was calculated by reference to their estimated loss under a “Loss Assessment Formula”. The LFA between CLF and group members provided that, in consideration for the benefits extended to group members under the LFA, CLF was to receive a commission of between 25% and 30% of net recoveries after reimbursement of litigation costs. The commission varied depending on the amount of shares in GPT acquired by the group member during what was defined as the “Claim Period”.

21 Those group members also executed a Legal Costs Agreement (LCA) with Slater & Gordon . There was evidence before the Court that the content of the LFA and LCA was relevantly the same for all group members who signed those agreements. The LCA set out the basis for Slater & Gordon charging fees in the proceedings on a time-recorded basis. The LFA specified the hourly rates for the lawyers and other staff working on the matter and an estimate of the legal costs and disbursements.

Aspects of the Settlement Distribution Scheme

22 The Settlement Distribution Scheme provided that:

1. Slater & Gordon’s legal costs be approved by the Court and then deducted from the Settlement Sum prior to individual group members’ entitlements being calculated (defined in the scheme as the Applicant’s Costs): [13.1(a)] and [18] of the Settlement Distribution Scheme. This means that the court-approved legal costs will be shared on a pro rata basis by all group members irrespective of whether they executed a LCA with Slater & Gordon;

2. a “funding commission” will be deducted from the individual entitlements of all group members and paid to CLF, irrespective of whether the group members executed a LFA (Funding Commission Deduction): [12.3] and [13.5(b)] of the Settlement Distribution Scheme; and

3. an amount representing a claim by Modtech for compensation for the time or expenses incurred by Modtech in prosecuting the Proceeding on behalf of all group members (defined in the scheme as Applicant’s Expense Claim) was to be deducted from the Settlement Sum prior to individual group members’ entitlements being calculated: [13.1(c)] of the Settlement Distribution Scheme. The Applicant’s Expense Claim was to be paid to Modtech and / or reimbursed to CLF, “as the case may be”.

23 Each aspect requires consideration. The Court does not rubber stamp a settlement. The role of the Court is onerous: Lopez v Star World Enterprises Pty Ltd at [16].

Applicant’s Costs

24 The first aspect, the Applicant’s Costs, raises two distinct issues. First, the amount approved by the Court will be shared (or at least the liability for payment of those costs will be shared) on a pro rata basis by all group members irrespective of whether they executed a LCA with Slater & Gordon. That proposal is not of concern. The legal costs were incurred and achieved a settlement for all group members. The group members who did not sign a LCA with Slater & Gordon should not be entitled to receive a windfall by reason of their refusal to sign a LCA. To put the matter another way, the legal costs are fixed. Those legal costs should be borne by those who benefitted from those legal costs being incurred – the group members as a whole.

25 That leads to the second issue – the quantum of the professional costs and disbursements incurred by Slater & Gordon. Slater & Gordon seek the quantum to be approved by the Court.

26 The rationale for the court’s “surveillance” over costs as between solicitor and client was explained by Tadgell J in Redfern v Mineral Engineers Pty Ltd [1987] VR 518 at 523 in the context of a taxation:

The court’s surveillance over costs as between solicitor and client is assumed with a view to preventing any unfair advantage by solicitors in their charges to their clients. It stems, it seems, from the notion that ordinarily a solicitor is presumed to be in a position of dominance in relation to [a] client as a result of [their] presumed knowledge of the law and of what may and may not be properly charged by way of fees. Were a strict view not taken it might be open to a solicitor to overreach his client or otherwise act oppressively towards [the client] on the matter of costs.

27 This is not a taxation. But it is unique. The solicitor is acting for itself – it seeks an order that its costs be approved by the Court and paid to it. There is no contradictor. The group members who are to share the liability for the fees and disbursements are unable to oppose the application. They are unable to oppose the application because although four group members obtained access, on a confidential basis, to the Settlement Distribution Scheme, that document did not record the amount of fees and disbursements the subject of the approval application or the how the sums were quantified. In addition, no group member has had access to the confidential affidavit of the costs consultant retained by Slater & Gordon that was filed in support of the application and set out the amount of fees and disbursements Slater & Gordon sought to have approved by the Court. The inability of the group members to act as a contradictor provides a further example of the “position of dominance” referred to by Tadgell J. Indeed, given the increasing number of class actions, it may be time for there to be a requirement that any LCA, or equivalent, between group members and a firm of solicitors should be approved by the Court before it is binding on the group members. Such requirement would be consistent with the Court’s ability to approve or supervise the form of costs agreements entered into between solicitors acting for a representative party and group members in relation to a representative proceeding commenced under Pt IVA of the Act: see s 33ZF of the Act and Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Ltd (1999) 94 FCR 167 at 175-176.

28 The Court, and the solicitors, have important, and distinct, tasks where the court’s approval is sought for fees and disbursements to be deducted from a settlement sum.

29 First, the solicitors have responsibilities that apply before, during and after, the approval process. As Allsop CJ and Middleton J most recently said in Madgwick v Kelly [2013] FCAFC 61 at [47]:

Solicitors are entitled to charge professional fees for undertaking the professional responsibilities of running the case, as officers of the Court, with all the attendant responsibilities (including duties to the Court) that that entails. No one, the solicitors included, should ever lose sight of those responsibilities.

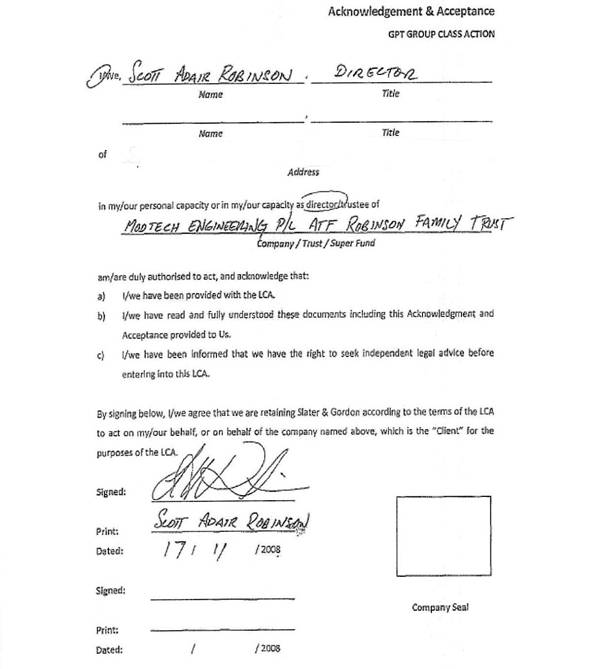

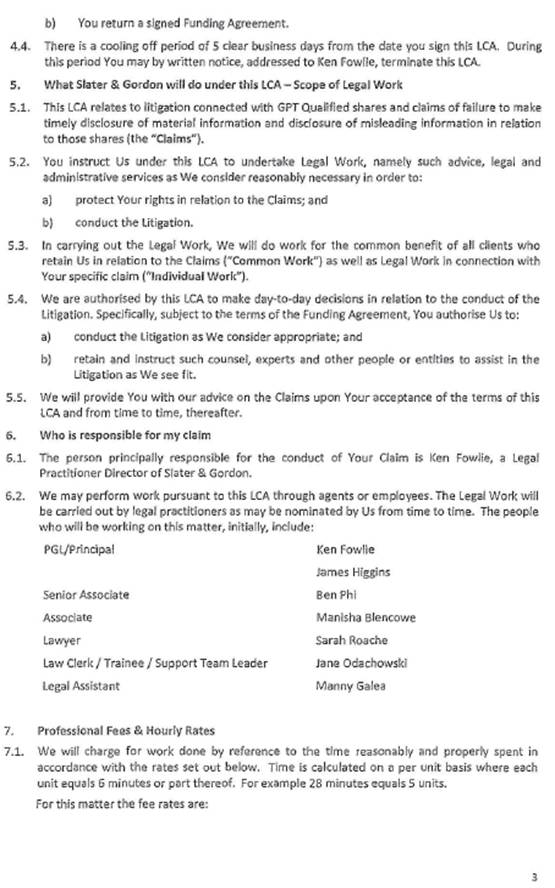

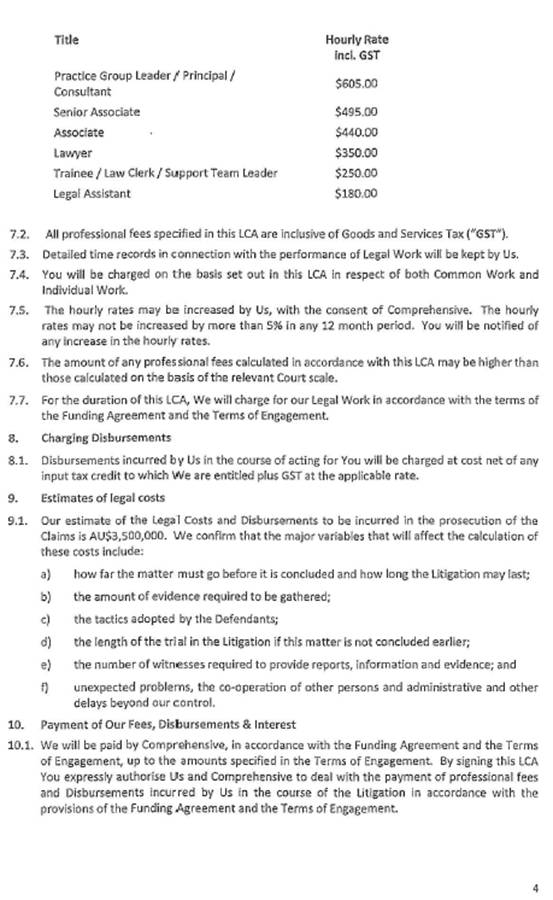

30 Here, there is a costs agreement (the LCA) between 92% of the group members and Slater & Gordon. That agreement contained specific terms and conditions on the fees and disbursements that could be charged by Slater & Gordon and the rate at which they could be charged. For present purposes, the LCA defined the “Scope of Legal Work” and included a section entitled “Professional Fees and Hourly Rates” which set out the basis for charging for work done. A copy of the LCA is Annexure A to these reasons for judgment. It will be necessary to return to consider some of these terms.

31 What then must the Court, and the solicitor, do when the Court’s approval is sought for fees and disbursements to be deducted from the Settlement Sum?

32 First, the role of the Court requires explanation. It has two aspects; the test to be adopted by the Court and then the material necessary to undertake the assessment. The task of the Court is not a taxation. The questions for the Court in assessing the fees and disbursements claimed by Slater & Gordon are twofold:

1. are the fees and disbursements of an unreasonable amount having regard to, inter alia, the nature of the work performed, the time taken to perform the work, the seniority of the persons undertaking that work and the appropriateness of the charge out rates for those individuals; and

2. if the work is unreasonable in the circumstances, can the group members be considered to have approved (explicitly or impliedly) the costs claimed.

33 As explained by Hodgson J in AGC (Advances) Ltd v West; AGC (Advances) Ltd v Cranston (1984) 5 NSWLR 301 at 303 (in the context of a taxation):

… taxed costs may be allowed even though they are of an unreasonable amount and even though they may have been unreasonably incurred if, in either case, this has happened with the approval of the client. There appears to be a qualification on this that, even if the client has approved, they are liable to be disallowed if they are of an unusual nature and such that they would not be allowed on a party and party basis, if it is also the case that the costs were not reasonably incurred and if it also be the case that no prior warnings were given to the client that the costs might not be allowed on a party and party basis.

Notwithstanding that qualification, the position remains that there is the possibility, if costs are assessed on a solicitor and own client basis, that they may be allowed even though they are of an unreasonable amount and unreasonably incurred where this has been approved by the client and I might add that an approval may be expressed or implied.

See also Dal Pont GE, Law of Costs (LexisNexis Butterworths, 2003) at [5.2]; Quick et al, Quick on Costs (Thomson Reuters, subscription service) at [20.1240] (update 78).

34 The next question is the material necessary to undertake that assessment. In Re Medforce Healthcare Services Ltd (In Liq) [2001] 3 NZLR 145, the Court considered the principles to be adopted in fixing a liquidator’s remuneration. It stated (at 155):

In our view the exercise which must be undertaken by the Court in fixing the reasonable costs of the liquidator is similar to that which is undertaken when approving solicitor and client costs or costs for legal aid purposes. In each case what is required is enough information to enable an assessment to be made as to whether the costs charged are reasonable.

As a minimum it seems to us that what is required is a statement of the work undertaken during the course of the liquidation, together with an expenditure account sufficiently itemised to enable the charges made related to the work done. The detail would have to be sufficient to enable a judicial officer to determine whether the personnel involved in the liquidation and their respective charge-out rates were appropriate to the nature of the work undertaken. Their information may in some cases raise concerns as to whether there has been overservicing or overcharging. If there are suggestions of this in the information provided, the Court can request further information.

(Emphasis added.)

See also Re Korda; in the matter of Stockford Ltd (2004) 140 FCR 424 at [48].

35 Two important matters referred to by the Court in Re Medforce should be restated. It is the judicial officer (not an independent costs expert) that is required to determine whether the fees and disbursements are reasonable. Second, the information to be provided to that judicial officer must be “sufficient” to enable that judicial officer to undertake that assessment.

36 In Lopez, Finkelstein J stated (at [16]):

[I]t [approving solicitors’ fees and disbursements] is a task in which the court inevitably must rely heavily on the solicitor retained by, and counsel who appears for, the applicant to put before it all matters relevant to the court’s consideration of the matter.

(Emphasis added.)

That statement is beyond question. But there is no one way to satisfy that obligation; the manner in which the solicitors seek to do that will vary from case to case: cf Venetian Nominees v Conlan (1998) 20 WAR 96 at 102-104. It does not require a bill of costs in taxable form. It does, however, require sufficient information to be put before the Court to enable the judicial officer to undertake the analyses identified in Re Medforce. The form and content will be a matter for the solicitors retained in each proceeding.

37 The requirement that sufficient information be provided to the Court by the solicitors seeking approval of their professional fees should not be onerous. Client reporting is an integral part of modern litigation. Clients want to know what solicitors are doing on a particular matter and where their legal costs are being spent. Indeed, it is now standard practice for law firms to manage these client expectations through the use of legal practice management software. That software is usually flexible enough to enable the software to require practitioners and staff working on a particular matter to allocate time to a specific task with annotations or a short narrative which describes the task in sufficient detail to explain the nature of the task. This kind of information could usefully be provided to the Court to assist it in assessing the reasonableness of the fees and disbursements claimed by a solicitor. Of course, that information is unlikely to provide a complete answer. It will require review and, possibly, consideration of, inter alia:

1. whether the work in a particular area, or in relation to a particular issue, was undertaken efficiently and appropriately;

2. whether the work was undertaken by a person of appropriate level of seniority;

3. whether the charge out rate was appropriate having regard to the level of seniority of that practitioner and the nature of the work undertaken;

4. whether the task (and associated charge) was appropriate, having regard to the nature of the work and the time taken to complete the task; and

5. the ratio of work and interrelation of work undertaken by the solicitors and the counsel retained.

This list is not complete. The relevant enquiries will vary from case to case.

38 What then did Slater & Gordon do in this case? In an attempt to justify the reasonableness of its professional costs and disbursements, Slater & Gordon engaged a costs consultant, Mr Linsdell, to provide an expert opinion on:

i. The reasonableness or otherwise of the legal costs and disbursements incurred for work conducted on behalf of [Modtech] up to the date of settlement in this proceeding;

ii. The reasonableness or otherwise of the estimate of the costs and disbursements likely to be incurred for work conducted on behalf of [Modtech] from the date of settlement until the distribution of settlement proceeds.

39 In carrying out that review, Mr Linsdell did not prepare a bill of costs. Mr Linsdell’s method of assessing the costs and disbursements claimed was described by him as an “assessment of costs”. It was explained by him as follows:

18. An assessment involves reviewing the file of the solicitor and/or reviewing time recording ledgers and accounts, and assessing the costs incurred pursuant to the costs agreement and by reference to the type of costs likely to be allowed on a solicitor/own client Taxation of costs.

19. The costs agreement must be considered to ensure it is fair and reasonable.

20. The costs agreement limits the costs which can be recovered by the solicitor given the agreement defines the work for which the solicitor is able to render a fee.

21. The costs consultant is then able to form a view, based on the individual amounts claimed for each piece of work performed on the file, of the total value of work done on a fair and reasonable basis.

22. In my experience, assessments of costs do not differ substantially from Bills of Costs in their accuracy and the overall calculation of the quantum of professional costs and disbursements.

23. However, assessments of costs are able to be performed within a compressed timetable and at a significantly reduced cost.

24. Given the scope of my instructions, number of documents involved and the limited time frame I had to prepare this report, I have taken a global approach to the assessment undertaken, rather than conducting a detailed assessment.

25. In doing so I have reviewed the costs actually charged by Slater & Gordon, and proposed to be charged, by reference to the costs agreement and my understanding of the test which would be applied on a solicitor/own client Taxation.

26. That test is that the costs are to be allowed unless they are unreasonable.

(Emphasis added.)

The “instructions” referred to in [24] of the extract, in fact, were two letters from Slater & Gordon to the costs consultant dated 12 and 13 June 2013 respectively.

40 Mr Linsdell’s assessment was divided into two headings – “Matter to Date Costs” and “Proposed Approval Costs”. The first category, “Matter to Date Costs”, was itself divided into two sub-categories: professional costs and disbursements. Mr Linsdell’s affidavit set out, in summary form, the conclusions he reached in determining a specific sum as an appropriate allowance for professional costs and a specific sum as an appropriate allowance for disbursements. Mr Linsdell did what was asked of him in the time available.

41 During the course of the hearing, a number of concerns were expressed about the adequacy of the material Slater & Gordon put before the Court as the basis for the Court approving the Applicant’s Costs. The following is not an exhaustive list. The list cannot be exhaustive because I am not satisfied that the Court has had put before it all matters relevant to the Court’s consideration of the issue. In particular, I do not accept that the affidavit sworn by the costs consultant (retained by Slater & Gordon) and filed in support of the approval application is sufficient. It must be recalled that it is the Court, not a costs consultant, that must approve the professional fees and disbursements.

42 What then are the concerns? First, the amount now claimed (and the subject of the approval application) is substantially in excess of the professional costs and disbursements that Slater & Gordon estimated in the LCA would be incurred in the prosecution of these proceedings. Slater & Gordon did not explain why their estimate (by a factor of about three) was so wrong. In fact, the affidavit filed by the costs consultant does not identify the total fees and total disbursements claimed by Slater & Gordon.

43 Next, the affidavit includes the statement that the costs consultant has only allowed those costs which he considers were reasonably incurred on a solicitor / own client basis. But that statement is not particularised. In addition, the nature or extent of the review undertaken by the costs consultant is of concern. His affidavit disclosed that he undertook a “global approach to the assessment rather than a detailed assessment”. His affidavit disclosed that:

In the course of my review I have been provided with unrestricted access to the files and papers of Slater & Gordon and have, subject to the time constraints, endeavoured to carefully review and consider the files and papers of Slater & Gordon. The files and papers of Slater & Gordon include:-

• 424 page billed time report

• 23 page billed disbursements report

• 26 correspondence folders

• Approximately 135 folders of expert reports, briefs to experts and associated documents

• Approximately 508 folders of briefs to Counsel and Mediator

• Approximately 83 folders of Court and associated documents

• Approximately 71 miscellaneous folders

In addition to the above hardcopy material voluminous material exists in electronic format. The electronic material I have had access to for review and consideration includes:

• Discovery database comprising approximately 11,317 documents of the Applicant and Respondents’ discoverable documents and documents produced by Third Parties under subpoena which totals approximately 65,900 pages in total

• Electronic court book comprising approximately 4320 documents

• Electronic file containing 9,538 individual items including correspondence, Court documents and general documents

• Electronic file containing the client data base listing all group members and then further broken up into RGN (sic) details, trading data, file notes and individual documents

44 However, of considerable concern is the statement by the costs consultant that:

I have not made any allowance for, or reduced the costs claimed for, work performed where:-

• The number of employees performing the task was excessive, or there had not been an appropriate division of work between the employees;

• the work performed was not within “the scope of work” for which costs could be claimed under the LCA and LFA;

• the work performed would not entitle the solicitors for the Applicant to claim costs on a reasonable basis; or

• the nature of the work performed was unclear.

(Emphasis added.)

The obvious question is – why not? This was not explained.

45 Then later in the affidavit, the costs consultant stated:

I reduced, or disallowed the costs claimed, in a number of areas, including:

i. Where the costs incurred appeared to relate purely to administrative tasks such as:

i. Diarising events

ii. Hyperlinking items in databases

iii. Searching databases

iv. Training employees

v. Updating correspondence files

vi. Filing

vii. Creating folders

viii. Labelling

ix. Attendance to catering

ii. Where the costs claimed related to the preparation of the LCA and LFA;

iii. Where the costs claimed related to the preparation of confidentiality agreements; and

iv. Where there appeared to be an excessive number of conferences and preparation for conferences.

The affidavit did not disclose the methodology adopted in identifying these items or the amount attributed to them which the costs consultant disallowed. In fact, nowhere does Mr Linsdell identify the people who worked on the matter, their role and their hourly charge rate. Indeed, it is by no means clear whether the hourly charge out rates listed in the LCA were used or any increased hourly charge rates, being the increased rates pursuant to cl 7.5 of the LCA. There was some suggestion that the rates had been increased by 5% on 1 July 2012. There was no material before the Court which demonstrated notice of that increase had been given to the group members, as cl 7.5 of the LCA required.

46 In that context, the hourly charge out rate adopted by the costs consultant in relation to the fees charged by Slater & Gordon in relation to discovery is of particular concern. The costs consultant explained what he did as follows:

51. The allowance I have made compares favourably to the costs allowed on a party/party basis and pursuant to the Scale of costs effective from 1 August 2011 which enables costs for perusal of documentation to be calculated pursuant to an hourly rate.

52. I base the assertion provided at paragraph 51 above on the fact that there were approximately 65,900 pages of documents produced by way of discovery and subpoena.

53. Allowing for 100 pages to be reviewed per hour, I calculated a total of around 659 hours for reviewing these documents.

54. The maximum attendance rate under the Scale of Costs is $550 per hour making a total of $362,450.00. A loading is then to be applied to this figure for skill, care and attention. In a case of this size, I consider such a loading to be up to 50%.

55. I consider, on a party/party basis and pursuant to the scale of costs, Slater & Gordon would be able to recover approximately $543,675.00, with respect to the review of discoverable material alone.

56. This accounts for approximately 13% of the allowance I have made for the entire professional costs claimable in the proceeding on a solicitor/own client basis, instead of a party/party basis, and pursuant to the LCA, not the scale of costs, and does not include the significant correspondence entered into to formulate a discovery plan.

47 This analysis raises a number of issues that require review. The costs consultant refers to the scale of costs. That scale applies in a taxation of costs: r 40.29 and Sch 3 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). The maximum attendance under that scale is $550 per hour. I accept that the scale may be of some assistance in assessing reasonableness but it must be recalled that the group members agreed in the LCA to a different and binding scale of hourly fees. The fee rate agreed to in the LCA for any person other than a “Practice Group Leader / Principal / Consultant” (including senior associates) was less, and in some cases substantially less, than $550 per hour as reflected in the table below:

Title | Hourly Rate (incl GST) |

Practice Group Leader / Principal / Consultant | $605.00 |

Senior Associate | $495.00 |

Associate | $440.00 |

Lawyer | $350.00 |

Trainee / Law Clerk / Support Team Member | $250.00 |

Legal Assistant | $180.00 |

48 It would be surprising, to say the least, if the review of most (let alone every) document was undertaken by a “Practice Group Leader / Principal / Consultant”. The rate adopted by the costs consultant would appear to be inappropriate – it was not agreed. Even if it was relevant as a method of assessing reasonableness, the rate adopted by the costs consultant raises serious questions about the seniority of staff undertaking discovery.

49 Next, the costs consultant does not appear to identify who reviewed the documents, what rate was charged and whether the amount charged was reasonable. I put to one side the additional loading of 50% applied by the costs consultant. The LCA did not provide for loading. However, even if it was permitted, if the costs consultant did not undertake the analyses just identified (which is not meant to be exhaustive), it is difficult to identify any basis on which to impose a loading, let alone a loading of 50%, for skill, care and attention. Especially is that so when the rate used was not the agreed rate and is a rate which would usually be excessive for a substantial part of the review of documents.

50 Finally, of no less concern is the fact that the costs consultant does not appear to recognise, and then go on to explain, that the amount he considers as an appropriate allowance for professional costs is in excess of the amount identified in the letters of instruction as the amount claimed by Slater & Gordon. That concern is heightened when it is recalled that he reduced or disallowed certain professional costs: see [45] above.

51 The aspects of the cost consultant’s affidavit relating to Slater & Gordon’s claim for disbursements raises similar issues.

52 In the circumstances of this case, the Court cannot approve the deduction of the Applicant’s Costs (which are in fact Slater & Gordon’s costs) from the Settlement Sum and then the payment of those costs to Slater & Gordon. Instead, the Court will approve that an amount of $9,338,865.00 be deducted from the Settlement Sum and placed into an interest bearing account maintained by Slater & Gordon.

53 A Registrar (or Registrars) of the Court will be appointed to assess the Applicant’s Costs on a solicitor / own client basis. The procedure to be adopted by the Registrar in assessing that claim will be determined by the Registrar in light of these reasons for judgment and consistent with the overarching purpose set out in s 37M of the Act – to facilitate the just resolution of disputes as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible and according to law. The Registrar will necessarily have to confer with Slater & Gordon (and possibly the costs consultant) to ascertain the content and form of the information Slater & Gordon is able to provide and which the Registrar will require to undertake the assessment. The Registrar will not have the power to fix the costs. The Registrar will conduct an assessment and provide a report to the Court. Slater & Gordon will be provided with a copy of the report. Once the report has been provided by the Registrar, the matter will be relisted to enable the Court to consider the report and to receive any submissions from Slater & Gordon. At that time the Court should be in a position to consider Slater & Gordon’s application for approval of the Applicant’s Costs. The amount ultimately approved by the Court will then, by separate order, be paid to Slater & Gordon with the interest earned on that amount. The balance (if any), including the interest accrued on that amount will then be distributed to group members on a pro rata basis.

54 Other categories of costs were identified by the costs consultant – (1) “Proposed Approval and Subpoena Costs” (totalling $412,500.00 at the upper end of the range) and (2) “Proposed Distribution Costs” (estimated at between $120,000 and $300,000). The first category will form part of the assessment by the Registrar, such amount having been included in the amount to be deducted from the Settlement Sum set out at [52] above. The second category is yet to be incurred and will not form part of that assessment. That amount will need to be subject of a separate application and approval by the Court.

Funding Commission Deduction

55 The Settlement Distribution Scheme also provides that a funding commission will be deducted from the individual entitlements of all group members and paid to CLF, irrespective of whether the group members executed a LFA: [12.3] and [13.5] in the Settlement Distribution Scheme. The Court does not approve that aspect of the Settlement Distribution Scheme. That statement requires explanation.

56 As noted above, approximately 92% of group members (including Modtech) executed a LFA with CLF to fund the proceedings. The LFA between CLF and group members provided that, in consideration for the benefits extended to group members under the LFA, CLF was to receive a commission of between 25% and 30% of net recoveries after reimbursement of litigation costs. The commission varied depending on the amount of shares in GPT acquired by the group member during what was defined as the “Claim Period”. The LFA was a written contract between a group member and CLF.

57 CLF, as a litigation funder, made a commercial decision to fund these proceedings on the terms and conditions set out in the various LFAs. Relevantly, it made a commercial decision to fund these proceedings by entering into a LFA with 92% of group members. Not 100% of the group members, just 92% of the group members. The question which arises is why should CLF be entitled to receive between 25% and 30% of the amount recovered by those group members who chose, for whatever reason, not to enter into a LFA (defined, erroneously, in the Settlement Distribution Scheme as “Informally Funded Registered Group Members”)? The deduction of the funding commission was never part of a commercial bargain reached by CLF with these so called Informally Funded Registered Group Members. In fact, for whatever reason, the Informally Funded Registered Group Members decided to do the direct opposite and not enter into a LFA. What has changed? I can identify no reason why the LFA should now be imposed on the Informally Funded Registered Group Members. They have not agreed to it.

58 That does not mean that the Informally Funded Registered Group Members should get a windfall. On the contrary. The amount of the so called “funding commission” (calculated on the amount of shares in GPT acquired by the group member during the “Claim Period”) should be deducted from each of their individual claims. However, instead of being paid to CLF, those amounts should be added back into the Settlement Sum and distributed pro rata to all group members. This approach may require an additional step or two in the calculation of an Individual’s claim but the result is fair and reasonable to all.

59 These concerns were discussed with Counsel for Modtech. He submitted that the Funding Commission Deduction for Informally Funded Registered Group Members should be approved for the following reasons:

1. Modtech, had agreed to it;

2. notice of the deduction had been given to all group members and no objection had been lodged. For those reasons, it should be inferred that the group members consented or were at least indifferent;

3. this class action was unusual because although it started as a closed class it was, for good reasons of public policy, subsequently opened;

4. on 11 October 2012, Informally Funded Registered Group Members were notified that the damages payable to them would be reduced by the amount of funding commission that “they would have paid had they obtained litigation funding”; and

5. it had been approved in a previous class action: see Pathway Investments Pty Ltd v National Australia Bank Ltd (No 3) [2012] VSC 625.

60 None of these matters, individually or collectively, provide a basis for approving the Funding Commission Deduction for Informally Funded Registered Group Members as proposed in the Settlement Distribution Scheme. The fact that Modtech has agreed to it is irrelevant. The role of the Court is to consider whether the settlement is fair and reasonable for all group members. The first time that group members were notified of the Funding Commission Deduction for Informally Funded Registered Group Members was in the Notice of Proposed Settlement served on the group members pursuant to orders of the Court dated 30 May 2013. The fact that no notice of objection has been lodged is a relevant, but not determinative, consideration. As was conceded by Counsel for Modtech, the notice given to group members in this case was different (having regard to the timing of the notice and the stage of the litigation) to that considered in Pathway Investments. For that reason, Pathway Investments may be put to one side. Whether such an order should be made is a matter to be addressed in each case. For the reasons set out above (see [56]-[57]), it is difficult to conceive of a circumstance in which it would be appropriate.

61 The Settlement Distribution Scheme will need to be amended. Once it is amended, it can be provided to the Court and be approved by it.

Applicant’s Expense Claim

62 The claim was described as an amount representing a claim by Modtech for compensation for the time or expenses incurred by Modtech in prosecuting the Proceeding on behalf of all group members (defined in the scheme as Applicant’s Expense Claim) which was to be deducted from the Settlement Sum prior to individual group members entitlements being calculated: [13.1(c)] in the Settlement Distribution Scheme. The Applicant’s Expense Claim was to be paid to Modtech and / or reimbursed to CLF, “as the case may be”.

63 The claim was explained by Ben Phi of Slater & Gordon in the following terms:

[37] Under ordinary principles governing the recovery of a litigant’s costs, the time spent by a litigant in such activity (as opposed to costs expended through legal representatives) is not recoverable from other parties under an order for the costs of a proceeding.

[38] In the present case, however, a claim is made for certain expenses on account of time devoted to the litigation by the Applicant’s director, Mr Scott Robinson. In representative proceedings, expenses incurred by an Applicant in connection with common issues in the proceeding have been approved as expenses appropriate to be met out of group proceeding settlement proceeds.

[39] Mr Robinson has devoted a considerable amount of time to this litigation over almost five years, from the time that Modtech Engineering Pty Ltd agreed to act as the representative applicant in late 2008, until the current date. He has spent this time:

a) reviewing communications from Slater & Gordon as to the proceeding;

b) conferring with Slater & Gordon and counsel as to the proceeding;

c) providing instructions in relation to significant matters in the litigation, including instructions forming the basis of his affidavit, filed in the proceeding;

d) identifying and collating documents to be produced via discovery, two separate tranches of which were requested by the Respondents;

e) attending the private mediation between the parties in February 2013;

f) preparing for his attendance at Court, and attending Court, to give evidence in the proceeding; and

g) reviewing the terms of the proposed settlement and executing the Settlement Deed.

[40] The majority of the time devoted by Mr Robinson to this litigation can properly be characterised as time expended on matters for the benefit of all group members. This level of attention far exceeds what would have been required of Mr Robinson, had the proceeding been advanced for the benefit of [Modtech] alone.

[41] The time expended by Mr Robinson undertaking tasks associated with this proceeding can reasonably be expected to have been devoted to other income-producing activities.

[42] Mr Robinson is an experienced engineer, property developer and business owner. I am informed that he has calculated his hourly rate by reference to the taxable income of $930,347 that he earned in the 2005/2006 financial year, and on the assumption of a 40-hour working week over a period of 48 weeks, Mr Robinson’s hourly rate is $485 (including GST). I have reviewed a copy of the relevant tax return and consider that this rate is reasonable. I am further informed by Mr Robinson that this was the last tax return filed by him prior to the commencement of the Applicant’s trading in GPT securities, and that the taxable income attested to represents the source of the funds used by the Applicant to invest in GPT securities.

…

[44] The Applicant’s Expense Claim totals $53,530.85. While the claim is at the high end of the range of similar expenses approved in other class actions, having regard to the particular features of Mr Robinson’s involvement, including the duration of his involvement, and his position, I consider the Applicant’s claim in respect of Mr Robinson’s expenses to be reasonable, and properly referable to benefits received in the litigation by the represented group as a whole.

64 This claim raises a number of issues. First, the claim is not made by Modtech but by the principal of Modtech, Mr Robinson. Second, the claim is based on Mr Robinson’s taxable income in the 2005 / 2006 financial year – the last year before he commenced trading in GPT securities. The problem with this is that the amount claimed relates to work undertaken from November 2008 up to and including May 2013. How Mr Robinson’s prior income provides a proper basis for this claim was not explained. It is by no means clear that the 2005 / 2006 financial year was a “usual” or appropriate year. Indeed, the manner in which the hourly rate was calculated has not been disclosed.

65 In substance, Mr Robinson’s application is an application for reimbursement for lost wages, salary or fees as a result of his involvement in the litigation. In some circumstances, a witness may seek the cost of their attendance at a hearing: see, for example, s 47F of the Act and Milfull v Terranora Lakes Country Club Ltd [2006] FCA 801. That cost is usually assessed by the production of relevant up to date financial information which identifies the loss of wages, salary or fees. The current application has not been made on that basis.

66 The expenses are also difficult to assess. A review of the invoice provided by Mr Robinson includes items which, on their face, seem excessive. By way of example, daily parking charges of $61.00, $51.00 and $41.40 are listed. Parking in the city is expensive. The real issue is whether these expenses were necessary to be incurred and are reasonable.

67 The solicitor must place before the Court all matters relevant to the Court’s consideration of whether to approve such a claim: see [37] above. In assessing the amount claimed by Mr Robinson, the Court has not been provided with any material to enable it to determine the reasonableness of the costs and expenses listed in the invoice. In the absence of such material, it is not appropriate for the Court to approve the Applicant’s Expense Claim or to approve for it to be deducted from the Settlement Sum prior to individual group members’ entitlements being calculated.

68 Finally, the order sought required the Court to approve that the Applicant’s Expense Claim be paid to Modtech and / or reimbursed to CLF, “as the case may be”. The reason for this arrangement was not explained. At the hearing, the Court was told that CLF had already paid to Mr Robinson the amount of the Applicant’s Expense Claim. Subsequent to the hearing of the application, Slater & Gordon filed further affidavit material going to the reasons for this arrangement. As set out in that affidavit, CLF’s agreement to the “pre-payment” to Mr Robinson was a commercial decision for them. CLF recognised that:

... it would bear the cost of any shortfall between the amount of the pre-payment and the amount of the Applicant’s Expense Claim (if any) approved by the Court.

69 CLF was prepared to take on this risk, in part, having regard to “applicant expense reimbursement orders being made by the Court in previous representative proceedings”. Presumably, CLF had in mind Darwalla Milling, where the settlement distribution scheme provided for certain “reimbursement payments and out-of-pocket expenses” by way of compensation for the time expended by the applicants and nominated group members in preparation of the evidence in the case in the interests of group members as a whole, and by way of reimbursement of the out-of-pocket expenses which two of the claimants incurred in relation to that preparation. Justice Jessup noted that there were good reasons why the court “should pause before approving payments of this kind” (at [75]):

First, although the claimants are not fiduciaries apropos the generality of group members, they have chosen to remunerate themselves, albeit modestly, ahead of the distribution to group members of a sum which has been calculated by reference to the estimated loss and damage suffered by the latter. The sensitivity of the position in which the claimants find themselves in these circumstances is obvious. Second, although courts have long-established procedures, and scales, by reference to which to assess the propriety and quantification of parties’ claims to be compensated for the legal costs and expenses made necessary by successful litigation, the same cannot be said of the payments with which I am presently concerned. I am denied the advantage of court scales and taxation procedures. I have only the claimants’ own evidence on the matter of the reasonableness of the payments, and of the necessity for the work and outlays to which they relate. Third, the court is denied the benefit of the contribution of a contradictor in relation to these payments. Although the same may be said of the settlement distribution scheme as a whole, the problem is particularly acute where the court has only the say-so of those who claim these benefits with respect, for example, to the time occupied on the work to which their claims relate and the hourly rates by reference to which particular categories of personnel should be compensated.

70 In Darwalla Milling, as in this case, the reimbursement claims were calculated by reference to the time spent by the claimants on particular tasks or attendances and nominal hourly rates. Two aspects of the claims gave Jessup J reason for concern: see at [80]-[81]. The first arose from “a general cautionary feeling” about the basis of calculation of the claims:

At the point of quantifying the amount of time spent by each of the claimants, the court has nothing but the say-so of the claimant concerned. There is no audit of the process or the result, and the applicants’ solicitors are in no position to certify as to the extent or nature of the attendances upon which the claims are based. Likewise, at the point of placing a money value on each hour, I have no reason to suppose that the standard rates supplied by the applicants’ solicitors are appropriate (apart, that is, from the claimants’ own say-so). As I have mentioned, there are no scales or taxation procedures. At both of these points, although the calculations are supported by spreadsheet records which look detailed enough as far as they go, there is very considerable generality in the way that some of the items are identified. If there is a risk that the real value of fair and reasonable compensation claims might be something less than stated in the spreadsheets, I am inclined to think that the claimants themselves should wear that risk. In other words, given that those who maintained the records on which the claims are based and then made the claims are the same parties as would stand to benefit from the granting of the claims, I consider that the court should be astute to identify any possibility of over-estimation and to make an appropriate allowance therefor.

The second concern for his Honour was that:

… the evidence upon which the applicants relied … did not sufficiently discriminate between time and expenditure which related to the organisation and preparation of the claimants’ own cases, on the one hand, and time and expenditure which had a truly representative purpose, on the other hand. I took then, and I still take, the view that it would only be time and expenditure of the latter category for which a reasonable case for compensation or reimbursement out of the corpus of the settlement sum might reasonably be made.

71 This second concern prompted the applicants in that case to file further affidavit material and written submissions identifying: (a) the categories of work in respect of which the claims were made; and (b) of those categories, those in respect of which it could be said that the work was undertaken for the benefit of the group members as a whole. It was only upon the provision of this further material that his Honour was in a position to approve of the claim made. Although Jessup J ultimately approved of a reimbursement payment, it did not include amounts claimed which could not be said to be solely for the benefit of group members as a whole. Moreover, I note that in Darwalla Milling, Jessup J had regard to the fact that the reimbursement amount actually claimed was approximately half the amount of the nominal value of the claims.

72 In the present case, Counsel for Modtech has sought leave to file supplementary affidavit material in relation to the Applicant’s Expense Claim. I would not grant that leave. To minimise delay, the sum of $53,530.85 will be deducted from the Settlement Sum and placed into a separate interest bearing account and dealt with in the same manner as the Applicant’s Legal Costs. In those circumstances, the affidavit will be unnecessary. The Registrar or Registrars will determine the information they require to assess the claim.

73 The Settlement Distribution Scheme will need to be amended to address the change in the way in which the Applicant’s Expense Claim is to be addressed. Once it is amended, it can be provided to the Court and be approved by it.

conclusion

74 For those reasons, I will make confidentiality orders under s 37AF of the Act in relation to identified affidavits and direct that, by 4:00pm on 25 June 2013, the parties file a minute of proposed orders, together with an amended Settlement Distribution Scheme, which gives effect to these reasons for judgment. Those orders should reflect the fact that the Registrar(s) should provide the necessary reports to the Court by no later than 26 July 2013.

I certify that the preceding seventy four (74) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Gordon. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A