FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kosciuszko Thredbo Pty Limited v ThredboNet Marketing Pty Limited [2013] FCA 563

|

Date of last submissions: |

30 November 2012 |

|

Place: |

Sydney |

|

Division: |

GENERAL DIVISION |

|

Category: |

Catchwords |

|

Number of paragraphs: |

|

|

Solicitor for the Applicants: |

King & Wood Mallesons |

|

Counsel for the Respondents: |

Mr KP Smark SC with Ms C Champion |

|

Solicitor for the Respondents: |

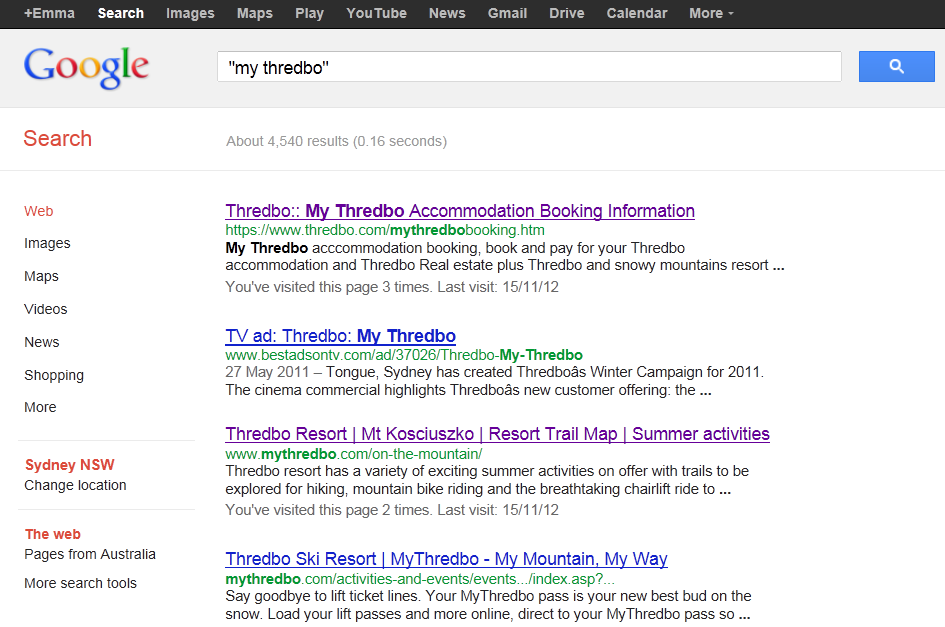

Hazan Hollander |

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be adjourned to Monday 17 June 2013 at 9.30 am to enable the parties to formulate by agreement orders arising from the findings contained in this judgment.

2. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

NSD 611 of 2012 |

|

BETWEEN: |

KOSCIUSZKO THREDBO PTY LIMITED (ACN 000 139 015) First Applicant THREDBO RESORT CENTRE PTY LIMITED (ACN 003 896 026) Second Applicant |

|

AND: |

THREDBONET MARKETING PTY LIMITED (ACN 097 622 869) First Respondent GLENN SMITH Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

COWDROY J |

|

DATE: |

11 June 2013 |

|

PLACE: |

SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 In this proceeding Kosciusko Thredbo Pty Limited and Thredbo Resort Centre Pty Limited (together referred to hereunder as ‘KT’) seek declarations, injunctive relief and damages against ThredboNet Marketing Pty Limited (‘ThredboNet’) and against the second respondent, Mr Glenn Smith (‘Mr Smith’), the sole director and shareholder of ThredboNet.

2 KT claims that the conduct of the respondents in registering domain names containing the word ‘Thredbo’, registering company and business names containing the word ‘Thredbo’, and controlling and operating websites whose content is similar to KT’s website, constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to ss 18(1) and 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘the ACL’), and passing off of KT’s business.

3 Second, KT claims that the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in connection with ThredboNet's business is a breach of subleases entered into between KT and Mr Smith. The respondents assert that such breaches are in relation to a clause that constitutes an unreasonable restraint of trade.

4 The respondents otherwise refute KT’s claims and submit that KT’s conduct should result in them being estopped from maintaining those claims.

5 The Court must determine the following issues:

1. Does the word ‘Thredbo’ have a secondary meaning such as to identify ‘Thredbo’ only with KT’s business?

2. Are the websites of the respondents sufficiently similar to those of KT so as to constitute misleading or deceptive conduct, or additionally to constitute passing off?

3. Do restraint provisions in the subleases between KT and Mr Smith preclude ThredboNet from using the word ‘Thredbo’ in connection with the respondents’ accommodation business?

4. If KT is successful in relation to questions 1, 2, 3 or 4, is KT estopped from obtaining the declaratory orders and relief it seeks?

6 For the reasons set out hereunder, the Court has concluded that the answers to the above questions are:

1. No.

2. No, except for the use of a hyperlink and website address known as the Genkan link.

3. No.

4. Relief is available to KT in respect of the Genkan link.

FACTS

7 KT holds an area of approximately 956 hectares under a head lease (‘the Head Lease’) in an area of the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales located within the Kosciusko National Park. The Head Lease was originally granted to a predecessor of KT on 29 June 1962 by the Minister for Lands of the State of NSW, who was then administering the Kosciusko State Park Trust.

8 On 18 February 1987 KT took an assignment of the Head Lease over the land, which includes the site of the Thredbo Village and Thredbo Resort (‘the Resort’). The Head Lease was renewed on 13 March 2007 and requires KT, as lessee, not to use the demised premises except for the purpose provided for in the Head Lease, being ‘the conduct of an Alpine and Summer tourist resort and Village’ and incidental purposes.

9 The Thredbo Village and the Resort provide year-round recreation and sporting facilities, primarily for skiing and snowboarding in winter months, and for hiking, fishing, tennis, golf, bushwalking and similar recreational activities in the summer months.

10 KT operates all the infrastructure services for the Thredbo Village and the Resort including the operation and maintenance of a sewerage system, water supply, road maintenance, sanitation services and pathways. KT also operates various recreational facilities. From 1987 to 2012 KT has expended well in excess of $150 million on several projects for equipment and infrastructure in and around the Thredbo Village and on the adjoining slopes. KT also conducts the operation and maintenance of all mountain infrastructure including ski lifts and all uphill transport, slope grooming (summer and winter), snow making, walking tracks and mountain access roads.

11 KT operates and manages the Thredbo Ski School and Thredbo Snow Sports. It employs all instructors for skiing and snowboarding lessons, whether group or private. It conducts the sale and hire of ski clothing, accessories and all ski and snowboarding equipment.

12 KT operates and manages the Thredbo Alpine Hotel (‘the hotel’), Thredbo Alpine Apartments and an accommodation complex know as Riverside Cabins. Through its affiliated company, Thredbo Resort Centre Pty Limited (‘TRC’) (the second applicant), it conducts and manages the Thredbo Reservation Centre (‘the Centre’) which arranges accommodation and hotel bookings. The Centre provides information relating to Thredbo Village, and of all the facilities available at the Resort.

13 TRC conducts a travel agency and a reservation centre for the accommodation managed by KT in Thredbo. TRC also conducts bookings for 16 other properties in Thredbo, located in Thredbo Village and its surrounds. Such properties are held by owners who have a sublease from KT. Whilst not required to do so, they have appointed KT to manage the properties.

14 TRC has an arrangement with two other booking agencies, Visit Snowy Mountains and Australian Alpine Resorts, such that in the event that a customer seeks to book accommodation which is not operated by KT, TRC will book that accommodation and obtain a commission. Accommodation bookings for the hotel and for properties managed by KT may be made by telephone, or by using KT’s website at www.thredbo.com.au or by sending an email to reservations@thredbo.com.au. Visitors may also book accommodation in person at the reservation centre.

15 The operations of KT are widely advertised in print media, by television and cinema promotions, and by the use of electronic media. KT is the registered owner of 14 business names, company names and domain names. In particular, it has used, and uses the domain name www.thredbo.com.au which it describes as the ‘official website’.

16 TRC has created a separate email address reservations@thredbo.com.au for the promotion of its accommodation services. TRC also uses the names ‘Thredbo Central Reservations’. Each of KT’s business names contains the word ‘Thredbo’. ‘Thredbo Reservations’ is registered and KT uses as its central email address reservations@thredbo.com.au.

17 KT has also developed a Facebook page for the promotion of its business. The Facebook page highlights a range of activities conducted in Thredbo Village.

18 As a result, KT claims significant goodwill and reputation in the name ‘Thredbo’ and assert that as a result of KT’s connection to Thredbo and reputation, the name ‘Thredbo has acquired a second meaning or independent reputation, or a ‘brand name’.

The Respondents’ business

19 ThredboNet and Mr Smith conduct an online business engaged in the managing and leasing of rental accommodation in Thredbo. As the respondents’ business interests are relevantly identical, they will be referred to as one, and for convenience, the respondents’ conduct will be referred to as that of Mr Smith.

20 From approximately 18 years of age Mr Smith would travel with friends from Sydney to visit the snowfields at Thredbo and Perisher Valley. When he returned to Australia from overseas in 1992 he resumed skiing in Thredbo and joined a ski lodge. He estimates that he visited Thredbo approximately 8 to 10 times per year with his wife and children.

21 Mr Smith became interested in acquiring a lodge at Thredbo and in 1997 he purchased the sublease of a property known as Mosswood 3. Such property was held by sublease from KT. It was a residential property and it was acquired as a rental investment. It was initially managed by TRC, but shortly after the 1997 ski season Mr Smith assumed management of the lodge. He received inquiries, made bookings, advertised the property and attended to a customer database.

22 In 1999 Mr Smith and his wife purchased another property known as Littleton. Mr Smith sold Mosswood 3 in approximately 2002. On 2 July 2002 Mr Smith and his wife acquired an assignment of the sublease for a property known as Fire Dreaming and these premises were used by Mr Smith for holiday rental accommodation. In early 2003 Mr Smith and his wife separated and on 15 October 2004 such sublease was transferred to Mr Smith. In 2006 Mr Smith acquired the sublease of another apartment known as Snowstreams 4 with a colleague, Wayne Donald Walgers. The property is also used for rented holiday accommodation.

23 Mr Smith incorporated ThredboNet on 26 July 2001 to facilitate the management of the properties situated in Thredbo Village and the surrounding area. Some of these are owned by third parties, others are owned by Mr Smith. The number of properties so managed has expanded. Initially five properties were managed by ThredboNet, but this has increased to approximately 50 properties.

24 ThredboNet’s operations include the promotion of its properties under its management; taking bookings; liaising between the tenant and the owner; providing checking in and checking out information; collecting rent from the tenant and remitting the rent to the owner. In 2007 Mr Smith became a licensed real estate agent and in 2009 ThredboNet received a real estate licence enabling the respondents to hold deposits for bookings on trust.

25 Mr Smith has registered and or used numerous email addresses and domains including www.book@thredbo.com, www.thredboreservations.com.au, www.thredbo.accommodation.com; www.thredbo-accommodation.com.au, www.thredbo.com (which address has been used by Mr Smith in conjunction with slogans ‘This is Our Thredbo’, ‘My Thredbo’, ‘The Best of Thredbo’), www.thredbonet.com, and a Facebook page www.facebook.com/ThredboReservations.

26 Since late 2011 clients of ThredboNet have received a series of emails from ThredboNet providing an encrypted link to a secure page at that address which include references to ‘book@thredbo.com’, the Thredbo Reservations Facebook page, the business ‘Thredbo Reservations, PO Box 149, Thredbo Village’, and ‘Thredbo Accommodation Service’. Mr Smith has acquired the domain www.thredbo.com, and has created links using the words ‘My Thredbo’ such that the address www.thredbo.com/mythredbo.com exists.

27 In late May 2011 Mr Smith first commenced using the website www.thredbo.com. KT asserts that from late 2011 Mr Smith actively promoted his business, as is evident from changes made to his other internet names used in conjunction with his businesses. In particular, KT claims that Mr Smith, since late 2011, has made alterations to his websites www.thredbonet.com and www.thredboreservations.com.au to give them the closer appearance of KT’s website. Such alterations include the use of red and white colours similar to KT’s website, using a font in captions similar to that of KT, and by adopting slogans such as ‘This is Our Thredbo’, in contrast to KT’s slogan ‘This is My Thredbo’.

28 As part of its passing off claim, KT alleges that as a result of its business activities there is a secondary meaning in the word ‘Thredbo’ such that it distinguishes its goods and services. Therefore it is claimed that the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ by the respondents in their business constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct and or passing off.

Basis of the secondary meaning claim

29 The Court will first consider whether a secondary meaning exists in the word ‘Thredbo’ as claimed by KT.

30 KT relies on the historical evidence concerning the foundation of the Resort, the existence of the Head Lease and of the power of KT to enter into sub-leases in support of its claim that it now has a secondary reputation in the name Thredbo. KT also relies upon the fact that its predecessor in title, Lend Lease, had continuously operated Thredbo Village since 1957; that in 1987 the business was sold to KT; that since 1987 KT has spent very substantial sums of money on the Village and Resort, and that KT has continuously used the name Thredbo in promoting its business and services as detailed earlier in this decision.

31 KT also relies upon the claim that it has, and at all material times has had, substantial goodwill and reputation in the Thredbo domain name and website. KT has been awarded numerous tourism awards. For example, in 1997, 1998 and 1999 KT was awarded the Best Year Round Alpine Resort Award. In 1999 KT was awarded the Major Tourist Attraction of the Decade Award. Its goodwill is claimed to have been developed through the use of media in print, online and ‘on the ground’ advertising.

Geographic origins of Thredbo

32 The Court has received evidence from KT concerning the history of Thredbo Village. Of particular assistance is a book entitled ‘Starting Thredbo’ by Geoffrey Hughes who is stated to be one of the founders of KT. The Court has also been assisted by the evidence contained in the affidavit of Rebecca Richardson, a town and urban planner, concerning the origins of the location in which the Thredbo Village is now located.

33 Ms Richardson’s investigations reveal that the Yaitmathang, the Wolgalu, the Waradgery and the Ngarigo Aborigines occupied the Snowy Mountains. The earliest evidence of Aboriginal occupation dates back approximately 8,700 years. The Southern Alps became a place for the aboriginal people for hunting, for congregation and for ceremonies. Summer visits to the peaks of the Snowy Mountains by local Aboriginal tribes and even those from further afield are well documented. European discovery commenced in 1823 when a party led by Captain Currie and Major Owens viewed the Snowy Mountains. Thereafter graziers began to use the grasslands. Pastoral leases have existed since approximately 1820, along the Crackenback River (now known as the Thredbo River) and continued until the mid-1900s when environmental impacts caused pastoral leases to be revised or revoked. Gold mining took place in Kiandra between 1860 and 1872, during which time prospectors converged on the Crackenback River in the hope of collecting gold. The publication of the Thredbo Historical Society entitled ‘Accordions in the Snow Gums: Thredbo’s Early Years’ by Helen Swinbourne refers to cattle droving in the area known as the ‘Thredbo Valley’.

34 Between 1906 and 1909 the then Premier of New South Wales introduced tourism to the Snowy Mountains with the establishment of Hotel Kosciuszko, Yarrangobilly Caves House and The Creel-at-Thredbo. The latter, which was a fishing lodge, was located at the junction of the Crackenback and Snowy Rivers. A photograph of the lodge displays its name ‘The Creel-at-Thredbo’. It was located several kilometres distant from the site of the current Thredbo Village. In 1976 the name of the Crackenback River was changed to its current name, the Thredbo River.

35 The name Thredbo has been attributed to the Aboriginal inhabitants of the Snowy Mountains. The earliest maps (prepared in 1881) held by the Surveyor-General’s office in Sydney include a map of the County of Wallace. Within that county there is a parish known as Thredbo Parish. A text written by Alan Andrews in 1998 refers, inter alia, to an account of an expedition which took place between 3 and 19 February 1840 by Stewart Ryrie. There is reference to the fact that Ryrie followed the ‘Little Thredbo River’ and that even though Ryrie had no Aborigine with him to help him with names, that location was known as ‘Thredbo’.

36 The evidence also suggests that ‘Thredbo’ was used in newspaper articles contained in the Sydney Morning Herald as early as 1852. In 1907 following the introduction of tourism to the area, reports referring to ‘Thredbo’, the geographic locality, were common.

37 The date of the preparation of the first detailed map of the Parish of Thredbo is not known. A plan of the Parish dated 1898 held by the NSW Division of Land and Property Information of the Parish of Thredbo shows the Crackenback River and its junction with the Snowy River. A 1940 map of the County of Wallace showing its parishes, including the Parish of Thredbo, shows the same features. It is apparent that there was no settlement indicated on any of the maps at the site of the current Thredbo Village. The Thredbo Village lies to the south of the Thredbo River (as it is now named) within the Parish of Thredbo.

38 The name ‘Thredbo’ is registered as a geographic location by the Geographical Names Board of New South Wales, a department of the New South Wales Government. The Board was established under s 3 of the Geographical Names Act 1966 (NSW) and is responsible for standardising the names of geographic locations. The record held by the Board for Thredbo Village states ‘Thredbo’ to be of Aboriginal origin.

Origins of Thredbo Village

39 ‘Starting Thredbo’ records numerous facts relevant to the establishment of the Village. Its origins resulted from the interest of European skiers and Australian skiers which developed from about 1947. In 1946 Elyne Mitchell toured extensively across the Kosciuszko snowfields and wrote a book entitled ‘Australia’s Alps’. In it she wrote:

The valley of the Crackenback, below Dead Horse (Gap) is one of the few places in our hills where a small alpine village would not be incongruous. The slopes of Rams Head Range are like many of the ski runs above the smaller European villages; there are plenty of rides and valleys descending from the main peaks and it is well tucked away from the wind - the curse of Australian skiing. There is a feeling of peace rather than the constant sense of wilderness.

40 In the Australian and New Zealand Ski Year Book of 1947, Venn Wesche wrote:

One day, there will of course, be a road up the (Thredbo or Crackenback) river from Jindabyne, and a lift up to the top from a tourist hotel at Friday Flat.

41 In the early 1950’s, a European worker engaged in the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, Tony Sponar, became aware of the Snowy Mountains Electricity Authority’s proposal to construct the Alpine Way. Mr Sponar had set up a downhill skiing course for downhill races at an area known as the George Chisholm course located close to the current site of the present village. Mr Sponar believed that if access was provided from a proposed roadway known as the Alpine Way to a site suitable for the bottom station of a chairlift to the top of the escarpment on the Rams Head Range, the possibilities for future skiing would be viable.

42 In September 1954 at the request of Mr Sponar, Sydney architect Eric Nicholls made enquiries of various chairlift manufacturers in Europe and in the United States for an installation at Thredbo. Mr Sponar, Mr Charles Anton, Mr Nicholls and Mr Geoffrey Hughes then considered the possibility of commencing a resort in the Thredbo Valley and they created a registered business name entitled ‘Kosciuszko Chair Lift and Thredbo Hotel Syndicate’ (‘the syndicate’).

43 In the winters of 1955 and 1956 Messrs Sponar, Anton and Hughes made exploratory trips to and in the Thredbo Valley to identify the most suitable site for a resort. They made extensive investigations of the Rams Head Range escarpment, and of the area known as Dead Horse Gap. Finally they located a site at the bottom of the slopes, with a substantial water supply, being the site around which Thredbo Village has been developed.

44 The syndicate then entered into an option for a 99 year lease with the Kosciusko State Park Trust. From this lease, subleases were to be offered for a 25-year lease term with an option to renew for a further 25 years. Early in August 1958 a chairlift was opened, and the Thredbo Ski School commenced.

45 In 1960 the financial affairs of the company improved as skiing became more popular in the Village. Under the Option for Lease, the syndicate was required to build a 100 guest bed hotel by 13 November 1962 to obtain its 99-year lease. The cost of such development was prohibitive for the syndicate. Accordingly, following negotiations, Lend Lease became the operator of the Thredbo Resort.

Has KT established a secondary meaning in ‘Thredbo’?

46 Ms Suzan Elizabeth Diver is the Communications Manager of KT. She has held the position for 17 years and previously was the Media Manager of KT. Ms Diver provided evidence relating to KT’s use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in its marketing.

47 From 1955 until present day, KT has used a variety of logos, all of which contained either the words ‘Thredbo’ or ‘Thredbo Alpine Village’. Ms Diver has provided an affidavit which exhibits voluminous printed material, all of which prominently feature the word ‘Thredbo’. Her affidavit asserts that KT ‘is the owner of the ‘Thredbo Brand’’.

48 Two logos have predominantly been used by KT in promotional material since 1987. The first, used from 1987, depicts a sphere with a mountaintop divided in two. On the left side there is the appearance of a mountaintop with green and the outline of vegetation. The right hand side depicts the mountaintop with a skier, in white with a blue background. Beneath the sphere is the words ‘Thredbo Alpine Village’.

49 From 2003, KT has used the ‘Thredbo Mountain logo’. It depicts a red mountain top with the word ‘Thredbo’ written in crayon font as shown below. This logo, as depicted immediately hereunder, has predominantly been used in red, however it has also being depicted in white or blue on a red background.

50 The Thredbo Mountain logo was accepted for registration as a trademark (1409243) by IP Australia on 15 December 2011, but is subject to opposition proceedings filed by the first respondent on 20 March 2012.

51 Since 2012, KT has adopted a further logo (the ‘new logo’) as set out below. It was red colour for the printed text and the lower left triangle, with shades of blue for the background mountain scenery.

52 Ms Diver has been involved in drafting the text and content for the winter and summer catalogues or planners since the early 1990s. Such brochures are distributed by either KT or TRC. KT maintains a mailing list. There are approximately 22,000 customers on the mailing list, who all received the 2012 Thredbo Winter Brochure.

53 Many of the promotional brochures published by KT have been relied upon in support of KT’s proposition that ‘Thredbo’ has acquired a secondary meaning. Ms Diver provided evidence of typical Thredbo Winter Brochures. The 1998 Planner referred to Thredbo as ‘Australia’s Ultimate Winter Resort’, providing the Thredbo Resort Centre as the place of contact to make a reservation. The 1994 Planner described Thredbo as ‘More than Simply the Best Place to Ski’, and provided details of KT’s accommodation, ski schools, lifts and a Village guide.

54 The 2004 Planner prominently displayed on its first page the www.thredbo.com.au website, and KTs Thredbo Mountain logo. The third page displays a central telephone number, the web address www.thredbo.com.au, and the contact email address: reservations@thredbo.com.au.

55 KT advertises its facilities as year round, and publishes a Thredbo Summer Brochure to advertise a range of summer activities. Its website www.thredbo.com.au, and its Mountain logo are prominently displayed, with the words ‘year round reservations’ on the last page giving details of accommodation options.

56 The 2012 Thredbo Winter Brochure identified a range of products and services available, including a ‘My Thredbo’ online service, operated via www.thredbo.com.au. Such service allows visitors to the Resort to arrange their lift passes and skiing requirements online before arriving in Thredbo. The Brochure also displays on the front page the Thredbo Mountain logo, and the address of the KT website.

57 www.thredbo.com.au has been in operation for 15 years. Such website is referred to in brochures published since 1997, and in cinema and television advertising since winter 1998. The website was visited close to two million times in the period 23 July 2011 to 23 July 2012. It also promotes the ‘Thredbo e-store’ which allows visitors to purchase online products such as lift passes and ski hire, children’s programs and gift cards. The information also includes details for the Thredbo Snow Sports School which offers a range of ski lessons and training programs at Thredbo. Also promoted is ‘Thredbo MyMoney’, a system similar to paid coupons which can be used throughout outlets operated by KT in Thredbo.

58 Ms Diver has also been involved in ancillary advertising materials such as postcards that feature the Thredbo logos, as well as bumper stickers which may feature Thredbo logos and tag lines from Thredbo’s advertising campaigns such as ‘What goes on in Thredbo stays in Thredbo.’

59 Social media is also used to promote KT’s activities. Ms Diver regularly updates the Thredbo Facebook and Twitter accounts. The Facebook page of Thredbo Resort contains images of the slopes in Thredbo, the Thredbo logo and comments from its patrons. An extract from KT’s Twitter account produced in evidence displays the Thredbo logo. KT relies upon a measure of its popularity as being reflected in 48,900 ‘likes’ on its Facebook page, compared to only 100 on the respondents’ Facebook page entitled ‘Thredbo Reservations’.

60 KT also advertises locally and Ms Diver is responsible for scripting advertisements. Advertisements are edited and provided to local television stations in Canberra, the south coast of New South Wales and Wollongong. Such advertisements usually contain videos identifying activities on offer at the relevant period of the year, and portray one of KT’s advertising slogan or logo ‘My Thredbo’, as depicted immediately below.

61 Christopher Joseph McGlinn, the Director of Marketing at Amalgamated Holdings Ltd (the parent company of KT and TRC), provided evidence of the extensive marketing of KT’s operations in cinema and film advertising, and of the often humorous or risquÉ tone used to promote Thredbo as a place of fun and recreation through the available sporting and social facilities available in Thredbo. The facilities are referred to as those in ‘Thredbo’, with KT’s website www.thredbo.com.au being displayed.

62 KT organises ‘staff presentations’ for the benefit of its employees. A video of the staff presentation in 2012 contained on a DVD has been made available to the Court. It contains interviews with employees who work in various departments in KT, including bars and restaurants, reservations, ticket sales, ski instructors, equipment hire, and elsewhere. The video demonstrates that the ‘branding’ of Thredbo is prominent in KT's operations. All KT employees wear uniforms that bear contemporary versions of the Thredbo mountain logo or the My Thredbo logo. Vehicles owned by KT display the Thredbo mountain logo. Ski instructors employed by KT wear red and white ski suits, being colours associated with KT's advertising for the last decade. Children participating at the Thredbo ski school also wear Thredbo branded vests bearing the KT logo.

63 Photographs, as attached to the affidavit of Benjamin Paul Arnall, show some extent of the advertising by KT at Thredbo. The logo of KT including the name ‘Thredbo’ is shown on maps, posters, souvenirs, uniforms, official cars, signs, lockers and skis.

64 KT operates seven snow cameras (also known as ‘snow cams’ or ‘live cams’) at Thredbo. These have been placed in permanent positions and capture the levels of snow at various times and various locations across the Resort. The cameras are regularly checked and maintained to provide a good image, which is uploaded to www.thredbo.com.au. The new Thredbo logo is superimposed on to the snow camera footage so that viewers will be aware that it is KT’s product.

65 In June 2011 KT launched its ‘My Thredbo’ advertising campaign in conjunction with the commencement of the Winter 2011 season. The advertising was displayed in and around Thredbo, and on KT’s website www.thredbo.com.au. The website, as referred to previously, www.thredbo.com.au/mythredbo enables a person to pre-arrange their ski passes and obtain exclusive concessions. The ‘My Thredbo’ slogan was promoted prominently in KT’s electronic newsletter from early June 2011.

66 Reginald Douglas Searle Bryson, the Chief Executive Officer of Brand Council Pty Ltd (‘Brand Council’), which is a strategic consultancy business specialising in brand creation, testified that he was involved in the development of the ‘Thredbo Brand’ from 1984 to 2004. Mr Bryson was involved in many of the advertising campaigns and conducted research to assess consumers’ beliefs and attitudes towards skiing holidays and consumers’ perception of Thredbo.

67 Mr Bryson stated that in the early period of his involvement, Thredbo was considered to be an elitist resort and that many Australian consumers did not identify with the ‘Thredbo Brand’. Mr Bryson worked closely with colleagues to create a 32 page booklet entitled ‘Thredbo Alpine Village, the First Resort for First Time Skiers’. The concept of the book was to promote the ‘Thredbo Brand’ as a friendly resort which was affordable. Mr Bryson states that the booklet was an advertising success.

68 Mr Bryson testified that based upon his 40 years experience in the advertising industry and advising clients on brand enrichment and image positioning, he considered that ‘notional values or dimensions associated with the Thredbo Brand’ distinguish it as one of the few ‘resort brands in Australia’. The other resort brands he suggested were Hamilton Island, Uluru and internationally, Disneyland.

69 KT is the proprietor of numerous businesses in Thredbo including Thredbo Card, Thredbo Newsagency, Thredbo Snowsports, Thredbo Sports, Thredbo Alpine Village, Thredbo Alpine Hotel, Thredbo Childcare Centre, Thredbo Club Card, Thredbo Leisure Centre, Thredbo Resort Centre, Thredbo Ski Resort, Thredbo Ski School, Theredbo Central Reservations, Thredbo Alpine Village Resort.

70 KT submits that the secondary meaning or reputation of the word ‘Thredbo’ need not be exclusive of the word's geographic meaning; the secondary meaning or reputation that KT relies upon can exist with its geographic name. KT argues that the word Thredbo’s secondary meaning distinguishes its goods or services even though the word carries a geographic descriptive meaning: Clark Equipment Company v Registrar of Trademarks (1964) 111 CLR 511 (‘Clark Equipment’) at 514.

71 KT submits that the brand name ‘Thredbo’ is, by all of the above evidence, established in KT, thus giving KT an exclusive right to use ‘Thredbo’. It submits that it is immaterial that a consumer may not know the identity of the entity who is the owner of the name, as considered in Powell v Birmingham Vinegar Brewery Co Ltd (1897) RPC 720 by Lord Herschell at 715 and by Lord Halsbury at 729.

Principles relating to secondary meanings

72 Generally, a secondary meaning or ‘independent reputation’ can be acquired in a word or mark which has a generic or descriptive meaning, as discussed in Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 222 (‘Peter Bodum’), where Greenwood J, in reference to the shape of a Coca-Cola bottle said at [9]:

Whether a secondary meaning or independent reputation exists in the features or shape of a particular product or its get-up is, it is said, a question of fact to be determined having regard to all the relevant contextual circumstances.

73 The more descriptive a word or mark is however, the greater the difficulty a claimant has in demonstrating distinctiveness in such mark: see McCain International Ltd v Country Fair Foods Ltd [1981] RPC 69 (CA); Yarra Valley Dairy Pty Ltd v Lemnos Foods Pty Ltd (2010) 191 FCR 297; Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at [335]-[336]; connect.com.au Pty Ltd v Goconnect Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 178 ALR 348 (‘Goconnect’) at [58]-[60].

74 It is a well established principle that a generalised descriptive name ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business: see Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd (1946) 63 RPG 39.

Principles relating to secondary meanings involving geographic names

75 It has been long accepted that significant hurdles exist for a claimant who seeks to establish a secondary meaning in a geographic name. In Clark Equipment, the High Court considered whether the word ‘MICHIGAN’, which had been used as a mark for 20 years in Australia was capable of distinguishing the applicant's products. At 513 Kitto J said:

That ultimate question must not be misunderstood. It is not whether the mark will be adapted to distinguish the registered owner’s goods if it be registered and other persons consequently find themselves precluded from using it. The question is whether the mark, considered quite apart from the effects of registration, is such that by its use the applicant is likely to attain his object of thereby distinguishing his goods from the goods of others.

76 At [514]-[515] his Honour said:

It is well settled that a geographical name, when used as a trade mark for a particular category of goods, may be saved by the nature of the goods or by some other circumstances from carrying its prima facie geographical signification, and that for that reason it may be held to be adapted to distinguish the applicant’s goods. Where that is so it is because to an honest competitor the idea of using that name in relation to such goods or in such circumstances would simply not occur: see per Lord Simonds in the Yorkshire Copper Works Case (3). This is the case, for example, where the word as applied to the relevant goods in effect a fancy name, such as “North Pole” in connexion with bananas: A. Bailey & Co. Ltd v. Clark, Son & Morland Ltd. (the Glastonbury Case (1)) (see also the Livron Case (2)), or where by reason of user or other circumstances it has come to possess, when used in respect of the relevant goods, a distinctiveness in fact which eclipses its primary signification. Cf. in the case of a descriptive word: Dunlop Rubber Co.’s Application (3). But the probability that some competitor, without impropriety, may want to use the name of a place on his goods must ordinarily increase in proportion to the likelihood that goods of the relevant kind will in fact emanate from that place. A descriptive word is in the like case: the more apt a word is to describe the goods, the less inherently apt it is to distinguish them as the goods of a particular manufacturer.

77 His Honour concluded by observing at [515]:

The consequence that the name of a place or of an area, whether it be a district or a county, a state or a country, can hardly ever be adapted to distinguish one person’s goods from the goods of others when used simpliciter or with no addition or save a description or designation of the goods, if goods of the kind are produced at the place or in the area or if it is reasonable to suppose that such goods may in the future be produced there.

78 The principle in Clark Equipment has been followed repeatedly. Courts have shown a distinct reluctance to find that a geographic name has developed distinctiveness such that other traders or persons are prevented from using the name. In Weitmann v Katies Ltd (1977) 29 FLR 336, Franki J said at 342 in relation to the claim for protection of clothing labelled ‘Saint Germain’:

Since “Saint Germain” is applied to an area in Paris, to some extent it falls within the category of geographical words. The origin of the words “Saint Germain” in my opinion makes it rather difficult for these words to acquire a secondary meaning.

79 In Colorado Group Ltd v Strand Bags Group Pty Ltd (2007) 164 FCR 506, the Full Court found that the word ‘COLORADO’ as used by the first appellant on items such as backpacks, handbags, purses (even though registered as a trade mark) was not inherently adapted to the appellant’s goods from the goods of other persons. At [29] Kenny J said:

I agree in substance with Allsop J that it is likely that another trader will want to use the word “Colorado”, legitimately, with regard to his goods, for the sake of the geographical reference which it is inherently adapted to make or the connotations that that geographic reference invokes. Accordingly, I agree in the conclusion of Gyles and Allsop JJ that the word “Colorado” alone is not inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services of the first appellant from the goods or services of other persons.

80 At [128] Allsop J (as he then was) said:

I have difficulty in accepting that the word “Colorado” is inherently adapted to distinguish backpacks, or even bags, wallets and purses. It is not a fancy or made up word. It is the use of a name being a State of the United States of America which has well-known mountains and is a rugged holiday area. In my view, the honest trader could well wish to make use of the signification of the word for geographic reasons – especially in relation to backpacks, or to raise a connotation from the geographic attributes of that State. In my view, the primary judge was wrong to conclude that the word was inherently adapted to distinguish.

81 In Bavaria NV v Bayerischer Brauerbund eV (2009) 177 FCR 300, Bennett J referred to the observations of Kitto J in Clark Equipment Co, observing at [66]:

The question whether a trade mark is adapted to distinguish a party’s goods is:

tested by reference to the likelihood that other persons, trading in goods of the relevant kind and being actuated only by proper motives – in the exercise, that is to say, of the common right of the public to make honest use of words forming part of the common heritage, for the sake of the signification which they ordinarily possess – will think of the word and want to use it in connexion with similar goods in any manner which would infringe a registered trade mark granted in respect of it.

[Clark Equipment Company v Registrar of Trade Marks (1964) 111 CLR 511 at 514 per Kitto J].

This has led to the rejection of a word of prima facie geographical signification, particularly when it is used simpliciter and where goods of the kind for which it is sought to be registered are produced at the place or in the area (Clark Equipment at 515-516), or if it is reasonable to suppose that such goods in the future would be produced there (Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Oxford (Trading as Oxford University Press) v Registrar of Trade Marks (1990) 24 FCR 1 at 23 per Gummow J). This is because other traders have a legitimate interest in using the geographical name to identify their goods and it is this interest which is not to be supplanted by permitting any one trader to effect trade mark registration (Clark Equipment at 514-515). Justice Gummow in University of Oxford came to the view that, if a court is in doubt as to the likelihood of another trader legitimately wishing to use a mark, the application should be refused (at 25). In Clark Equipment, Kitto J held that the word MICHIGAN was not adapted and was not capable of becoming adapted to distinguish earth-moving and other equipment. Similarly, OXFORD was refused for printed publications (University of Oxford) and COLORADO refused for bags (Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd (2007) 164 FCR 506). In each case, the registration sought was of a word mark that connoted a geographical location.

82 The case concerned Bavaria as a trademark for beer and other beverages. At [67] Bennett J said that Bavaria NV ‘appears to accept that there are difficulties with the word ‘Bavaria’ being adapted to distinguish its beer’ on the basis of Kitto J’s reasoning in Clark Equipment but found that because the trademark contained the reference to ‘Holland’ and included individual heraldic and declarative elements, the trademark was distinguishable and therefore registration was permissible: see [74]-[75].

83 In Kenman Kandy Australia Pty Limited v Registrar of Trade Marks (2002) 122 FCR 494, Stone J said at [145]:

Signs that are descriptive of the character or quality of the relevant goods or which use a geographical name in connection with them cannot be inherently distinctive because the words have significations or associations that invite confusion and because registration of a trade mark using such words would preclude the use by others whose goods have similar qualities or which have a connection with the relevant areas.

84 Stone J also said at [156]:

… trade marks were held to be inherently adapted not because of any positive content but because they had no associations or significations that prevented them from being inherently adapted to distinguish a trader's goods.

85 Certainly the evidence of Mr Bryson establishes that Thredbo is promoted as being a resort and a place of fun and excitement. However, in the absence of a registered trademark, promotion of a name does not by itself give rise to an exclusive use of that name or badge of origin. In British Sugar PLC v James Robertson and Sons Limited [1996] RPC 281, Jacob J referred to this fact at 302:

There is an unspoken and illogical assumption that “use equals distinctiveness”. The illogicality can be seen from an example; no matter how much use a manufacturer made of the word “Soap” as an unsupported trade mark for soap the word would not be distinctive of his goods.

86 In rare instances, such as those considered in J. Bollinger v Costa Brave Wine Co Ltd (No 2) [1961] 1 WLR 277 (‘Bollinger’) it may be possible to establish a brand name in a geographic region. However the circumstances in Bollinger are entirely different to those now under consideration. In that decision, the House of Lords found that the wine producers from the location known as ‘Champagne’ in France had developed such a unique reputation as to warrant protection of their goodwill from trades of other areas using the name ‘Champagne’: see summary in Erven Warnink BV v J Townend & Sons (Hull) Ltd (No 1)) [1979] AC 731 at 745, 747. Lord Diplock referring to the Bollinger decision, observed in Warnink at 747 that it was essential that the product have ‘recognisable and distinctive qualities’ and have generated the necessary goodwill to warrant protection.

Finding: Secondary meaning

87 There is no question that KT has been responsible for the expenditure of many millions of dollars in developing the Resort and Thredbo Village. However there was no evidence adduced from members of the public concerning a distinction which they might have drawn between Thredbo, namely the geographic location, and the Thredbo Resort. Further, there is no evidence from the public to suggest that the public identifies ‘Thredbo’ as equating to the Thredbo Resort or Village. Further, the evidence of Mr Bryson, the evidence of the publications and media publicity of KT, and of the infrastructure organised by KT and of the Village and the Resort, do not fulfil the special requirements to establish exclusivity in the geographic name, such that ‘Thredbo’ has assumed such a reputation that it only applies to the undertaking of KT.

88 No clear picture emerges from the promotional material that Thredbo, namely the geographic place, should be treated as distinct from Thredbo Village or Resort. The use of Thredbo in connection with the ‘Village’ and Thredbo ‘Resort’ defines the location of the Village or Resort as being at the geographic place, Thredbo.

89 The 1994 brochure promotes the Thredbo Village and its facilities but the word ‘Resort’ does not appear. The word ‘Resort’ is mentioned, briefly, in the 1996 brochure, and in the 1997 brochure but rarely mentioned until 2000 when there is a reference to ‘in the Resort’.

90 The 2001 brochure states: ‘THREDBO is a fully self-contained resort…’ and subsequently states ‘THREDBO is around a 6 hour drive from Sydney or Melbourne…’. The 2002 brochure refers to Thredbo as a ‘world class year round holiday destination’ and refers to Thredbo as a self contained resort. In the introduction under the heading ‘Welcome to Thredbo’ it states:

From the moment you arrive in THREDBO you’ll be taken with the unique village atmosphere…

Whatever you need you’ll find it all in THREDBO.

91 The 2003 brochure states:

THREDBO is a mountain for everyone…

92 Subsequently it refers to:

You’ll certainly get a lot out of your day in THREDBO, Australia’s ultimate winter resort.

93 The examples above do not draw a significant distinction between the geographic place and KT’s Resort.

94 The Court has considered the logos, but concludes that none of them have depicted KT’s Resort such as to create a secondary signification. The word ‘Thredbo’ does not necessarily connote solely the Resort. The Thredbo Valley, the Thredbo River, and commercial and residential activities with which KT is not connected exist at Thredbo. KT’s chosen business name is synonymous with the geographic location, but there are no features of the word ‘Thredbo’ which distinguish the geographic place name from KT’s name. Similarly, the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in KT’s website at www.thredbo.com.au does not give rise to a secondary meaning.

95 Having reviewed all the evidence, and the principles embodied in Clark Equipment, the Court is unable to conclude that the applicant has discharged the burden of proof that the word ‘Thredbo’ has acquired a secondary meaning, namely that the use of the word ‘Thredbo’ in its business names, internet names and logos has become so distinctive such that KT has a right to use it to the exclusion of all others. Thredbo is a recognised geographic place, and the locality has been known as Thredbo well before the Resort was developed.

96 The authorities referred to above provide a salutary reminder of the difficulties encountered when exclusivity is claimed in respect of a geographic name. The fact that ‘Thredbo’ is known as a place, and not merely the Village or KT’s Resort, disentitles KT’s claim that it has established a secondary meaning in the word ‘Thredbo’ so that it has the exclusive right to use such word.

MISLEADING OR DECEPTIVE CONDUCT

97 There are three broad issues for the Court to consider with respect to KT’s claim that the respondents have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct. The first is the alleged similarities between the appearance and content of the websites of the respondents as compared to that of KT. This includes the overall get-up of the respondents’ websites, the use of ‘Thredbo’ in the domain names of the respondents, and the use of the slogan ‘This is our Thredbo’. The second issue is the incorporation of KT’s slogan ‘My Thredbo’ by the respondents into a hyperlink for accommodation reservations. Finally, the Court will consider the alleged similarities between KT’s Facebook page and that of the respondents.

98 Before addressing these issues however, a background to KT’s claim for misleading or deceptive conduct will be considered.

Background to KT’s claim for misleading or deceptive conduct

99 The Court was provided with electronic copies of KT’s website www.thredbo.com.au as well as the various websites operated by the respondents of which KT complains. Each of the websites will be briefly described in order to assess the conduct of the respondents which allegedly breaches ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

KT’s website: www.thredbo.com.au

100 www.thredbo.com.au is described by KT on its website as ‘the official Thredbo website’. The website has been live since 1997, and was in cinema and television advertising, brochures, signage and other material soon afterwards. Since 2003 the website has utilised colours in red, white and blue. The Thredbo Mountain logo then used has already been referred to above, and is repeated hereunder.

101 Prior to 2012, each page of KT’s website displayed the Thredbo Mountain logo prominently. This changed in 2012 when the new logo was adopted. It too is displayed on each page of KT’s website prominently.

102 Ms Robin Mary Maes, Director of Digital Media at Amalgamated Holdings Ltd stated that electronic direct marketing and social media, including the Thredbo Resort Facebook page, are important for the promotion of Thredbo and that it is important to maintain ‘the richness of the content’ of www.thredbo.com.au to ensure it ranks highly in search engine rankings.

103 Since 2012, KT’s redesigned website continues to use many of the features used by its former website. Its tag line is red on blue ‘MY THREDBO’. Prominent imagery and scenery of Thredbo also appears. Similar imagery appears on KT’s Facebook page.

104 The background of the homepage of the website features a variety of seasonal images of people enjoying activities such as mountain biking, hiking, skiing and relaxing, as well as landscape photographs of the Thredbo area. The website is divided into seven broad categories of subpages: ‘weather and conditions’; ‘on the mountain’; ‘in the village’; ‘accommodation’; ‘bookings and tickets’; ‘activities and events’; and ‘about Thredbo.’ When a viewer clicks on one of these categories, further subpages drop down to provide information relevant to the category.

105 The website provides comprehensive information about Thredbo Village and the Resort. The website also contains links to an ‘e-store’, where one can buy lift passes and other products for their vacation. The ‘Accommodation’ category displays a webpage where one can insert the proposed dates of their travel and see what accommodation is available at what prices.

Development of the respondents’ websites

106 In 2000 Mr Smith, who has extensive experience with electronic media, created a website, www.thredbonet.com, to promote the properties he owned in Thredbo. To maximise tenancy rates for the properties managed by ThredboNet, Mr Smith developed websites for Thredbo properties managed by ThredboNet. The evidence shows that the website appearances have been updated from time to time. From 2004 to 2010 Mr Smith registered more than 20 different domain names.

107 ThredboNet uses an automated booking system, called Genkan, designed by a software developer especially for holiday rental properties. A company search of Genkan Pty Ltd records that Mr Smith is a director of that company. Genkan Pty Ltd is advertised as having the ability to ‘build and edit email or SMS marketing campaigns personalised directly from your Genkan database’. In this way, the system was developed to respond to email requests for accommodation, take deposits, send payment reminders to customers and send the customer booking information. Arrival information is forwarded to the customer together with an SMS which provides the access code to the property and check-in information.

108 The system also sends an email to the client which contains a link to a website where the client can review all details of their booking. This facility avoids the use of password and username by the client. From 2009 until late May 2011, the link sent to the clients had the domain name www.thredboreservations.com. However, following the acquisition by Mr Smith of the domain name www.thredbo.com, that address was used in substitution. A link was provided to enable the client to readily access the booking and to enable any alterations to be made on a web page entitled ‘My Thredbo Booking’. An example of such link was provided in evidence as follows: http://www.thredbo.com/mythredbo.htm?action=booking_manager&edit=1&agent=THRE&bl=db1f83fb5fe9218e92ec696c283904e1d7d5b66a.

Description of www.thredbonet.com and www.thredboreservations.com.au

109 In early 2001 Mr Smith launched www.thredbonet.com and it did not change significantly in appearance until 2011. The original version which was tendered to the Court had a homepage with a predominantly blue background. In 2011, the website was revised. At the time of the hearing, a banner appeared at the top of the page and the word ‘Thredbo’ was written in red lower case letters. Immediately below, the phrase ‘accommodation specialists’ appears in black writing on a white background. In the bottom right hand corner in a different font is the slogan ‘The Best of Thredbo…’. The background image for the banner changes each time the page is entered or refreshed, but an example appears immediately below. The main body of the homepage contains a list of accommodation available for hire. The homepage also contains snow cam images of the Thredbo area. KT’s logo appears on the snow cam images.

110 Subpages of www.thredbonet.com provide a calendar of availability for various properties, more information about self-contained chalets and properties for sale.

111 www.thredboreservations.com.au was launched in 2009. In 2011, the website was altered to be substantially the same as www.thredbonet.com. However, different properties are advertised and www.thredboreservations.com.au does not contain snow cams.

Description of www.thredbo.com

112 In May 2011, Mr Smith purchased the domain name www.thredbo.com in an online auction for $10,000.00. KT was aware of the auction, but formed the opinion that the vendor was attempting to inflate the price of the domain name, and was seeking an extravagant price. Accordingly KT decided not to bid.

113 The version of www.thredbo.com which was tendered to the Court has a homepage which has a predominantly white background. In a banner on the top of the page the word ‘Thredbo’ is written in the same red font as on www.thredbonet.com. The words ‘accommodation specialists’ are written in white. The banner contains rotating images of the Snowy Mountains, an example of which is shown below:

114 One version of the website tendered in evidence contained the slogan ‘This is our Thredbo’ in a script font in the lower right hand corner of the top banner. The main body of the webpage provides basic information about Thredbo. That section of the website states:

Thredbo is Australia's premier ski and alpine resort, Thredbo is open all year round. The ski season opens on the queens birthday [sic] weekend in June and closes early October. Thredbo has 13 ski lifts rising from 1380 metres in the valley to over 2000 metres at the top of Karels. Over the summer months Thredbo is transformed from white to green, from skiers to walkers venturing to Australia's highest peak, Mt Kosciuszko.

115 Below that, the webpage displays further information about accommodation and real estate available in Thredbo. The bottom portion of the webpage contains a list of properties available for rent in a manner similar to www.thredbonet.com.

116 A navigation menu is shown on the left side of the webpage. The navigation menu contains links to pages which provide more information about the accommodation availability and pricing, as well as last minute specials available. The website also contains terms and conditions for booking of accommodation through the website. In the first line of the terms and conditions, the following is stated:

In providing booking services Thredbonet Marketing Pty Limited ABN 44 097 622 869 (“Thredbonet Marketing”) acts as an agent for various property owners and Thredbonet Marketing does not accept or undertake any personal liability when acting in this capacity.

117 The webpage also contains information about activities which can be enjoyed in Thredbo, including activities which are operated by KT. Further the webpage contains information about dining options in Thredbo.

Description of www.accommodationthredbo.com.au

118 www.accommodationthredbo.com.au has a homepage which is on a predominantly blue background. The website provides information about accommodation available in Thredbo in a format similar to www.thredbonet.com. There is no additional information about the other features of the Thredbo area other than the accommodation available within it. The individual pages for the accommodation on offer describe the features of the Thredbo Village and Thredbo Resort (e.g. the nearby slopes at Friday Flats).

Description of www.realestatethredbo.com.au

119 This is the homepage for ‘Discover Thredbo Real Estate’. The homepage is on a predominantly blue background. It provides more in depth information, such as valuations, upcoming inspections and property management about owning (more correctly, subleasing) property in Thredbo Village. In addition, the homepage contains this statement:

The National Parks and Wildlife Service administers the lease area on behalf of the State Government, the landlord to Kosciuszko Thredbo P/L, KT, who is the head lessee. You, the individual property owner are therefore a sub lessee of KT. KT are your “local council”, and provide all municipal services including water and sewage for an annual “bed license” [sic] payment.

Description of www.thredbo-accommodation.com

120 At the top of this website’s homepage, the address is written in a plain blue font. The background of the website is primarily white. The majority of the webpage is taken up by advertisements for properties available for rent in a similar fashion to www.thredbonet.com.

Description of www.discoverthredbo.com

121 This website’s homepage features a predominantly dark blue background. It appears to be designed as a sort of ‘gateway’ to other websites operated by the respondents. For example, there are links to the respondents’ specific accommodation and real estate websites. There are also links to employment opportunities with the respondent.

122 One of the pages within the website does provide information about ski lift prices and dates and prices for activities coordinated by KT. However, this page does not appear to have been updated since 2007.

Other websites

123 There are other websites that KT has referred the Court to. However, the primary complaint with the remaining websites is that the domain name contains the word ‘Thredbo’. Due to the finding above regarding use of the word ‘Thredbo’, the Court does not need to consider these websites further.

Similarities relied upon by KT

124 The similarities of the respondents’ websites to www.thredbo.com.au which KT relies upon for injunctive relief are:

that the respondents’ domain names include the word ‘Thredbo’;

that the respondents’ websites www.thredbonet.com and www.thredboreservations.com.au contain text essentially in red colour on a white background in shades virtually identical to that of KT’s website;

that www.thredbonet.com and www.thredboreservations.com.au use script font (similar to the crayon font used by KT in its My Thredbo logo, adopted in about April 2011), in respect of the slogan ‘The Best of Thredbo’ and again in respect of the slogan ‘This is our Thredbo’ on www.thredbo.com;

that the respondents' websites contain information on activities in Thredbo which is similar to the information contained in KT's website;

that www.thredbo.com shows scenery of Thredbo similar to that used by KT in its website; and

that the respondents use a link that incorporates the words ‘My Thredbo’ in relation to accommodation reservations.

125 Prior to 2005 KT has used the colour red in association with their services. In 1994 the Thredbo ski school information leaflet showed a ski instructor wearing red uniform. The Thredbo summer planner for 2004 and winter planner for 2005 both prominently show the Thredbo mountain logo in red on the front cover and throughout the publication. A book entitled ‘Thredbo 50, 1957 to 2007’ by Jim Darby shows red being the predominant colour used by KT.

126 Mr Bryson compared www.thredbo.com.au with the respondents’ website www.thredbo.com. Mr Bryson said of the respondents’ website:

(a) the website has an “official” or “legitimate” imprint, creating the overall impression that “Thredbo Accommodation Reservations” is connected with KT and the official Thredbo Brand. This is particularly due to the use of the domain name www.thredbo.com to advertise precisely the same or very similar services as that advertised on the Official Thredbo Website;

(b) it utilises the colours red and white which as noted above I associate with the Thredbo Brand;

(c) it goes well beyond the “booking agent’s” website as it provides the consumer with much more information than mere accommodation options at Thredbo, for example it contains pages with respect to “Last Minute Specials” and “Thredbo Winter Weekends” (analogous to the packages available through the Official Thredbo Website), pages with respect to “Eating Out in Thredbo” (analogous to the section of the Official Thredbo Website concerning Restaurants and Retail in Thredbo) and the section entitled “Thredbo Weather” (analogous to the “Live Cams” section in the Official Thredbo Website which depicts the weather in Thredbo through live feed from seven different snow cameras).

127 Finally KT submits that the respondents actively encourage the belief that their business is that of KT because the www.thredbo.com page title contains the words ‘Resort Information’.

Evidence of Confusion

128 KT has relied upon evidence which it submits establishes confusion in the mind of the public and therefore evidence of passing off. Michael Damien Brooks gave evidence that during November 2011 he had booked accommodation for himself and his family in premises known as ‘Elevation 5’, following receipt of an email from Mr Smith. The email relevantly stated:

Thredbo Reservations and www.thredbo.com are pleased to announce a new fresh, new and easy approach to paying for your Thredbo ski accommodation. What we had endeavoured to achieve is to remove the two large payments, (deposit and final payment) and offer you the option of spreading the load and making 7-8 monthly interest fee payments between now and ski season to secure your accommodation for 2012.

…

5 simple steps

1. Visit www.thredbo.com

2. Check availability and pricing

3. Select your accommodation

4. At checkout select “Winter Payment plan”

5. Pay 10% deposit with your credit card.

…

Guests taking up this option will on arrival at the property receive a www.thredbo.com “welcome pack” and be privy to other special offers throughout the 2012 ski season.

…

For more information visit www.thredbo.com or www.lastminute.com

THREDBO RESERVATIONS

PO Box 149 Thredbo Village

Ph: 02 64 576281 email book@thredbo.com web: www.thredbo.com

129 Having received such email, Mr Brooks visited the www.thredbo.com website and formed the impression that it was the website of, or was associated with KT. Mr Brooks testified that he formed such opinion because the domain name of the website contained the word ‘Thredbo’ which he had associated with KT; the use of the page title ‘Thredbo accommodation reservations’; the phrase ‘Thredbo reservations’ in the email; the colour red being used on the website and in the email; and the content of the website which contained the menu of activities in Thredbo.

130 As a result, Mr Brooks made a booking on 19 November 2011 at ‘Elevation 5’ for the period from 8 July 2012 to 15 July 2012 at a cost of $7,081.13. Upon arrival for the holiday on 8 July 2012, Mr Brooks and his family were disappointed to find that the accommodation had been double booked with the result that he was obliged to make alternative arrangements. Mr Brooks believed that KT was responsible and he inquired at KT’s office to find out what had caused the booking to be dishonoured. Only then did he ascertain that KT did not make the booking. In a letter of complaint dated 20 July 2012 to ThredboNet, Mr Brooks testified to the unsatisfactory response he received when he attempted to make contact with the respondents’ booking service.

131 A further example of claimed confusion is contained in the evidence of Nicole Louise Thrum who works as a consultant at TRC. In October 2011, Ms Thrum received an email of the same type sent by Mr Smith to Mr Brooks promoting payment by instalments for accommodation. The email had been forwarded to her by a person seeking accommodation in Thredbo who sought more information about the promotion. Ms Thrum informed the inquirer that the website used for the booking did not belong to KT.

132 Another example relied upon to show confusion is the evidence of Ms Jessica Elsie Christiansen, who is also a consultant at TRC. On 23 July 2012 a female guest telephoned her to complain about the accommodation at a lodge known as Mitta Mitta. Upon further investigation it became apparent that the booking was made through the respondents and not through KT.

133 Further, on 8 July 2012 Ms Christiansen received a complaint from a male guest seeking access to Snowman Apartment. This guest could not obtain access to the property because the door code was not operative. Again upon inquiry it was discovered that the accommodation was booked through the respondents and not KT.

134 Evidence of a similar kind was provided by Susan Elizabeth Ward who is the manager of TRC. Ms Ward confirmed that she had seen the emails referred to in the evidence of Ms Thrum. She also testified that on 20 July 2012 two women visited the TRC to complain about the standard of cleanliness at their accommodation located at Snowstream 4. The women believed that they had made the booking through KT. On investigation it was established that the respondents had made the booking. A diary note of that incident was tendered to the Court.

135 Lastly, KT relies upon the fact that a letter sent by the Consumer, Trader and Tenancy Tribunal (‘CTTT’) to KT’s post office box at Thredbo Village was addressed to Thredbo Reservations. Such letter relates to a complaint between a consumer and the respondents’ business. KT relies upon the wrong address as demonstrating confusion either at the instance of the consumer or of the Tribunal.

136 Mr Smith provided evidence to show that the double booking of the property the subject of Mr Brooks’ reservation occurred as a result of a misunderstanding between him and the property owner of ‘Elevation 3’ and denied responsibility for the mistake. Mr Smith stated that he had no knowledge of complaints received from any other person who may have booked accommodation through his company.

Principles applicable to misleading or deceptive conduct claims

137 The principles applicable to s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (now repealed) also apply to the considerations under ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the ACL. Those principles are well established: see Hornsby Building Information Centre Proprietary Limited v Sydney Information Centre Limited (1978) 140 CLR 216 (‘Hornsby Building Information Centre’); Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177; Equity Access Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corp (1989) 16 IPR 431. The relevant authorities have been conveniently referred to in S&I Publishing Pty Ltd v Australian Surf Life Saver Pty Ltd (1998) 88 FCR 354 at 361-363.

138 In summary, the principles to be applied are as follows:

(1) There will be no contravention of s 52 unless the error or misconception which occurs results from the conduct of the corporation and not from other circumstances for which the corporation is not responsible: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 1; 149 CLR 191 at 199–200 per Gibbs CJ and at 209–11 per Mason J; Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 91; 55 ALR 25; Tobacco Institute of Australia v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations (1993) ATPR 41–199 and cf Argy v Blunts & Lane Cove Real Estate Pty Ltd (1990) 26 FCR 112 at 132 ; 94 ALR 719.

(2) Conduct will be misleading and deceptive if it leads into error: Parkdale at CLR 198.

(3) Conduct will be likely to mislead or deceive if there is a “real or not remote chance or possibility” of misleading or deceiving regardless of whether it is less or more than 50%: Global Sportsman at FCR 87.

(4) Conduct causing confusion or uncertainty in the sense that members of the public might have cause to wonder whether the two products or services might have come from the same source is not necessarily misleading and deceptive conduct: Parkdale at CLR 200; Bridge Stockbrokers Ltd v Bridges (1984) 57 ALR 401 at 413 per Lockhart J; Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177.

(5) In a case such as the present an applicant must establish that it has acquired the relevant reputation in the name or get up such that the name or get up has become distinctive of the applicant's business or products: Sheraton Corp of America v Sheraton Motels Ltd [1964] RPC 202; BM Auto Sales Pty Ltd v Budget Rent A Car System Pty Ltd (1976) 12 ALR 363.

(6) Conduct may be misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive notwithstanding that the corporation said to engage in that conduct acted honestly and reasonably and did not intend to mislead or deceive: Parkdale at CLR 197 per Gibbs CJ; Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 223 ; 18 ALR 639 per Stephen J; Global Sportsman at FCR 88. Logically, a finding that conduct had been intentionally engaged upon will be irrelevant in determining whether that conduct is misleading or deceptive. It may perhaps be imagined that conduct engaged upon with the intent to mislead or deceive may fail in its purpose and not be found misleading or deceptive. Nevertheless, where the intention to mislead or deceive is found, it logically would be likely that a court would more easily find that the conduct was misleading or deceptive: cf Australian Home Loans Ltd v Phillips (1998) ATPR 41–626 and New South Wales Dairy Corp v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co Ltd (1989) 86 ALR 549 at 558.

(7) In many cases it will be necessary to consider the class of persons to whom the representation was directed: Parkdale at CLR 199 and Taco Bell at 202.

(8) There is no proposition of law to the effect that intervention from erroneous assumption between conduct and misconception destroys the necessary chain of causation with the consequence that the conduct cannot be regarded as likely to mislead or deceive: Taco at 200; Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (1998) 156 ALR 316 at 344–5.

(9) The test of whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive is an objective one for the court to determine. It is ultimately a question of fact.

139 It is important to observe that in respect of the fourth principle above mere confusion in the mind of a consumer does not equate to conduct which is misleading or deceptive. In Hornsby Building Information Centre, Stephen J relevantly stated at 228-229:

When, as in s. 52(1), the focus is upon the misleading of others rather than upon the injury to a competitor, it becomes of particular importance to identify the respect in which there is said to be any misleading or deception. The particular feature of the Hornsby Centre's conduct of which the Sydney Centre complains as being misleading and deceptive is not simply the use of its corporate name, so similar in part to its own name, but rather that by that use others are led to believe that the Hornsby Centre is a branch of, or is otherwise associated with, the Sydney Centre.

The Sydney Centre tendered some evidence that persons had been misled in this way and for present purposes I will assume that this has occurred. But to determine whether there has been any contravention of s. 52 (1) [Trade Practices Act 1974] it is necessary to inquire why this misconception has arisen in the minds of others. This necessarily leads one to examine the name of the Sydney Centre. The name which it adopted as its own consists of three descriptive words, prefixed by a word of locality, the whole of which it uses as its trade and corporate name. Having done so it cannot, as it acknowledges, claim any monopoly in the descriptive words; yet it does in fact seek to impose conditions upon another's use of those words, the condition being that an explanatory disclaimer should accompany that use.

…

The use by the Sydney Centre of the three descriptive words was no doubt convenient. It thereby acquired a name which at the same time very clearly described its activities.

…

There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name. Because it is descriptive it is equally applicable to any business of a like kind, its very descriptiveness ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business and hence its application to other like businesses will not ordinarily mislead the public. In cases of passing off, where it is the wrongful appropriation of the reputation of another or that of his goods that is in question, a plaintiff which uses descriptive words in its trade name will find that quite small differences in a competitor's trade name will render the latter immune from action Office Cleaning Services Ltd. v. Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd., per Lord Simonds). As his Lordship said (37), the possibility of blunders by members of the public will always be present when names consist of descriptive words-

"So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be."

The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.

Consideration of the use of ‘Thredbo’ in the respondents’ websites

140 The Court finds it to be likely that a person seeking to book a holiday will use the internet as the first source for information. The Court also accepts that www.thredbo.com.au, and other electronic means such as the Resort Facebook page are important for a person seeking to arrange a holiday.

141 The Court accepts the evidence of Miss Maes that, to ensure that KT ranks highly in the Google search engine ranking, KT must maintain ‘richness of content’. This is achieved by the use of logos, colours, the navigation bar providing information on services and facilities in Thredbo. That is, the ‘quality score’ is vital.

142 KT submits that where the ‘quality score’ in the winter season for www.thredbo.com creates such a proximity between that website and KT’s www.thredbo.com.au, or where the respondents’ website www.thredbo.com achieves the ‘AdWords bid’ on the search term ‘Thredbo’, by which the respondents’ website features ahead of KT’s in a Google search for Thredbo, there exists the potential for consumers being misled or deceived, or are likely to be misled or deceived.

143 The Court has found above that KT has failed in its claim that it has developed an exclusive right to use the word ‘Thredbo’. It follows that, subject to one circumstance considered later relating to the Genkan Link, the use of ’Thredbo’ by the respondents is unexceptional. Both KT and the respondents are entitled to use the word Thredbo. The operation of websites with domain names such as www.thredboreservations.com.au or www.thredbo.com does not give rise to any misrepresentation.

144 Stephen J’s reasoning in Hornsby Building Information Centre, set out at 228-229, also applies to the circumstances in this proceeding. KT has chosen to primarily market its ski resort as ‘Thredbo’, which is a ‘word of locality’. Occasionally, it uses the word in conjunction with descriptive words, such as ‘Thredbo Resort’ or ‘Thredbo Reservations Centre’. When another company, which also conducts business in Thredbo, decides to use a similar arrangement of the ‘word of locality’ plus descriptive or generic words, e.g. ‘Thredbo Accommodation Reservations’, then KT cannot be heard to complain that such conduct is misleading or deceptive.

145 The facts in this proceeding can be distinguished from ‘cybersquatting’ cases such as CSR Ltd v Resource Capital Australia Pty Ltd (2003) 128 FCR 408. In that proceeding, the respondent, who had absolutely no connection with the sugar refiner CSR and who had no intent to enter the Australian sugar market, registered a domain name www.csrsugar.com.au and then attempted to sell it to CSR. Hill J found that the respondent had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct by representing that they would be engaged in the Australian sugar market, when in fact they had no such intent. In contrast, there is no doubt that the respondents in the present proceeding use domain names containing the word ‘Thredbo’ in order to promote accommodation in the Thredbo area.

146 Rather the use of ‘Thredbo’ in domain names by the respondents is similar to the circumstances in Goconnect. In such case, Emmett J considered whether misleading or deceptive conduct existed in respect of a registered trade mark ‘Connect’ and ‘connect.com.au’ and the respondents’ web addresses ‘goconnect.net.au’ and ‘goconnect.net.’ His Honour found that the word ‘connect’, because it was a common English word, could probably never become distinctive: see [57]. Significantly, his Honour continued: