FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

REA Group Ltd v Real Estate 1 Ltd [2013] FCA 559

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 21 June 2013, the parties confer and bring in short minutes of orders dealing with:

(i) the exchange and filing of submissions as to the extent and form of any relief which ought be granted consequent upon the findings made in the reasons for judgment accompanying these orders; and

(ii) the steps to be taken to facilitate any further hearing as to damages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 900 of 2010 |

| BETWEEN: | REA GROUP LTD (ACN 068 349 066) First Applicant REALESTATE.COM.AU PTY LIMITED (ACN 080 195 535) Second Applicant |

| AND: | REAL ESTATE 1 LTD (ACN 140 715 028) First Respondent SIXTEEN BLAMEY PTY LTD (ACN 130 053 271) Second Respondent GEOFFREY LUFF Third Respondent JULIE LUFF Fourth Respondent CHRISTIAN ONGARELLO Fifth Respondent BIANCA ONGARELLO Sixth Respondent |

| JUDGE: | BROMBERG J |

| DATE: | 7 JUNE 2013 |

| PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 Scouring the real estate classifieds of a metropolitan daily newspaper used to be an essential Saturday morning activity for those interested in buying or renting real estate. With the advent and increasing popularity of the internet, consumer behaviour has been greatly altered and perhaps no more so than in relation to the purchase or rental of real estate. Over the last ten years the advertising of property has increasingly shifted away from newspaper classifieds to what are known as internet property portals. A property portal is a website where real estate agents list and consumers view residential or commercial property. A property portal enables a user to search for properties by reference to criteria such as location, features and price.

2 The second applicant is a wholly owned subsidiary of the first applicant. The applicants (collectively “REA”) have a business which operates two property portals of significance to this case. The first is located on the internet at www.realestate.com.au. That property portal has operated since 1998 and lists residential properties that are available to rent or buy. Both the domain name (a part of the internet address) and the trading name used by REA for this business is “realestate.com.au”. That name is the subject of three composite trade marks held by REA. The second property portal, operational since 2002, is located on the internet at www.realcommercial.com.au. This portal lists commercial properties available for purchase or rent. Both the domain name and the trading name used by REA for this part of its business is “realcommercial.com.au”. That name is the subject of a composite trade mark held by REA.

3 The first and second respondents also carry on a business which operates property portals. The non-corporate respondents are either principals of the business conducted by the corporate respondents or work in that business. Since March 2009, the corporate respondents (collectively “Real Estate 1”) have operated a residential property portal located on the internet at www.realestate1.com.au. The internet address of the business includes the domain name “realestate1.com.au”. The business has traded under the name “Real Estate 1” and also by reference to its domain name.

4 Between August 2009 and the commencement of this proceeding in October 2010, Real Estate 1 also operated a property portal dealing with commercial property that was located on the internet at www.realcommercial1.com.au. The internet address for that business included the domain name “realcommercial1.com.au” which it also used as its trading name. Since October 2010 it has instead used “realestate1commercial.com.au” as its domain and trading names.

5 The following major questions arise for determination:

(a) Did the use by Real Estate 1 of the name “realestate1.com.au” in relation to real estate advertising services, give rise to conduct that did or that was likely to mislead or deceive internet users searching for REA’s residential property portal to regard Real Estate 1’s portal at www.realestate1.com.au to be the same, or related to or associated with REA’s portal located at www.realestate.com.au, in contravention of (the former) ss 52, 53(c) and 53(d) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“the TPA”)?

(b) Did the use by Real Estate 1 of the name “realcommercial1.com.au” in relation to real estate advertising services, give rise to conduct that did or was likely to mislead or deceive internet users searching for REA’s commercial property portal to regard Real Estate 1’s portal at www.realcommercial1.com.au to be the same as, related to, or associated with REA’s portal located at www.realcommercial.com.au, in contravention of ss 52, 53(c) and 53(d) of the TPA?

(c) In the circumstances described, did the use by Real Estate 1 of the names “realestate1.com.au” and “realcommercial1.com.au” in relation to their property portals amount to passing off at common law?

(d) Did the use by Real Estate 1 (whether alone or as part of a logo) of the marks “realestate1.com.au” or “realcommercial1.com.au” infringe REA’s realestate.com.au trade marks or the realcommercial.com.au trade mark contrary to s 120 of Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (“the Trade Marks Act”)?

(e) Are the individual respondents liable as accessories for any contravention of the TPA, passing off and/or trade mark infringement committed by Real Estate 1?

the facts

The internet and other technical background facts

6 The determination of the central issues in this case requires a basic understanding of how the internet, and search engines used to find information on the internet, operate. The evidence dealing with those background matters was not controversial. The following findings are largely drawn from the evidence provided by Michael Hudson, a member of REA’s ‘Web Strategy’ team with extensive experience in website design and development and search engine optimisation. For ease of reference, technical terms are shown in bold.

7 The internet is a system of interconnected computer networks. The series of interlinked documents on the internet are known as the world wide web. A web page is a document containing text, images or other information that is available to be viewed on the world wide web. Each web page has a unique address or URL (uniform resource locator) which is also know as a web address. When a series of related web pages are linked together and designed to be read as an integrated whole, they are known as a website.

8 Internet users who wish to make information available to others on the world wide web can register a domain name, which is an alphanumeric alias for a web address. Most web addresses contain a domain name alongside a component which is used to designate a particular type of server, such as “www” for the world wide web or “m” for a mobile server.

9 Once a domain name is registered, information in the form of a web page or website may be located at that domain name and internet users are able to retrieve information from that page or site by entering the relevant domain address (either with or without the “www” prefix) into a web browser. A web browser is a computer program used for retrieving and displaying information on the internet. Some well known examples of web browsers are Internet Explorer (produced by Microsoft), Firefox (by Mozilla), Chrome (by Google) and Safari (by Apple).

10 A domain name consists of at least two parts, known as labels or levels, which are separated by full stops. The two essential components of a domain name are a top-level domain (for instance “.com”, “.org” or “.net”) and a second-level (or lower level) domain, which is the specific or unique component of the domain name, selected by the website owner. Typically, the second-level domain will consist of the website owner’s trading name or brand name (such as “amazon” in the domain name “amazon.com”).

11 There are some 22 generic top-level domains maintained by the Assigned Numbers Authority, an entity responsible for overseeing global internet address allocation. The top-level domain “.com” is the most popular generic top-level domain on the internet. It is commonly utilised by commercial entities, whilst “.gov” is used for government entities and “.edu” for educational institutions. Many domain names also have a country code top-level domain. The country code top-level domain for Australia is “.au”.

12 An internet user searching for a website who is familiar with the specific URL or domain name associated with the website can find the website by entering that URL or domain name directly into the web browser on his or her computer. However, a person unfamiliar with the URL or domain name of a website will ordinarily use a search engine to discover the web address where the information they require may be found. Persons familiar with the URL, may also, for reasons of convenience or habit, use a search engine to find a hyperlink to a website instead of entering the URL directly into a web browser.

13 Search engines are information retrieval systems that index web pages available on the internet using software which enables web pages to be scanned so that the search engine may recall parcels of information associated with those web pages in response to a keyword search request made by a searcher. Well known search engines include Google, Bing and Yahoo!. A search engine searches for information on the internet in response to keywords entered by the user into the search bar of the search engine. Search engines use complex algorithms to find information on the internet relevant to the keywords selected by the user. After conducting a search, search engines display search results on the computer screen of the user in the form of a list. The list may be short or may extend to tens of pages. Each page will generally show a maximum of 10 search results.

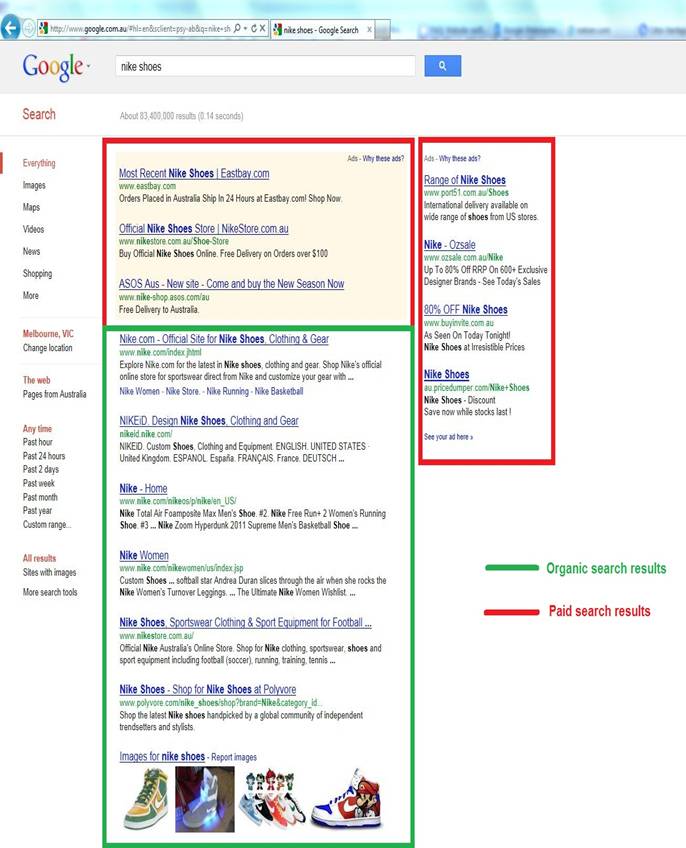

14 There are two different types of search results usually displayed on a search results page. Organic search results are search engine results displayed in response to the keyword search terms entered by the user. They are ranked in order of relevance according to a formula applied by the search engine by which the search engine tries to identify the most relevant web pages or websites referrable to the keywords entered by the searcher. Organic search results produced by internet search engines and displayed on the search results page will, for each result shown, usually consist of at least three elements:

(a) a headline or title, that when clicked, is a hyperlink to the web page (usually in blue and usually bolded, underlined and in larger type face than the rest of the search result);

(b) the URL (including the domain name) for the web page (usually in green and in small type face); and

(c) a description of the information on the web page or associated website (usually in black).

The following provides an example:

Federal Court of Australia

www.fedcourt.gov.au/

The Court is a superior court of record and a court of law and equity.

15 Paid search results (also known as sponsored links) are small advertisements that also appear on the search results page partly in response to the specific keyword search terms entered by the user into the search engine. Paid search results are usually presented directly above or on the right hand side of the organic search results but may be presented at the foot of the first page or on the second page. They are usually shaded or separated from the organic search results in order to distinguish them. In addition, the paid search results usually appear under a heading such as “sponsored links”, “promotional links” or “ads”. Each paid search result is also shown with the same three elements (headline, URL and advertising text or description) as appear in organic search results.

16 If the user clicks on to the headline or title of a search result, the user will be taken to the URL or web address shown in the search result. The web page may or may not be the first page or ‘home page’ of the website. The search result may provide a link to a different page on a website. For instance a search for “real estate Brunswick” may produce a result that will take the searcher directly to a page on a property portal which lists real estate in Brunswick. In that case the web address given will likely be far longer than the domain name for the website. For instance “www.realestate.com.au/Buy/in-brunswick”. URL’s appearing in search results will thus vary in size.

17 A further feature of a search results page is that each of the keywords used by the searcher will be highlighted in bold wherever appearing (ie in the title, URL or description).

18 Annexure A to these reasons for judgment is a screenshot of a search results page generated by Google’s search engine in response to a keyword search for “Nike shoes”. It shows each of the features earlier discussed including the bolding of the keywords. Borders have been added to the screenshot to clearly distinguish between organic and paid results.

19 The mechanisms by which a search engine determines the order in which organic search results and paid search results appear on search results pages require more detailed explanation.

20 Search engines utilise complex algorithms to match information on the world wide web with the keywords selected by the user. There are three main factors that are commonly understood to be taken into account by a search engine in determining the web pages to be included as a search result and the order in which the search results are displayed. Those factors are known as ‘trust’, ‘authority’ and ‘relevance’. ‘Trust’ is a measure of credibility, with government websites (which end in the top level domain “.gov”) and educational websites (which end in the top level domain “.edu”) considered particularly credible because of the nature of the institutions which operate them. ‘Authority’ is measured by reference to the number of links that a website has from other third party websites, the manner in which those websites link to each other (for example what words are used in the link) and the quality of the content of the linked websites. Thus a website to which other large, credible websites link, is likely to rank more highly than a website without those connections. The ‘relevance’ of a website is assessed by the search engine considering whether and to what extent the keyword search entered by the user is related to a specific topic, subject or theme covered by the web page or website being considered for inclusion in the search results page. In determining relevance, the search engine will read both the text and images visible to a user looking at a web page and also the underlying source code of the web page. That underlying source code is known as metadata. Metadata may also contain metatags, which are keywords (not visible on the web page) inserted by programmers for the purpose of search engine optimisation, a process I will explain shortly. Search engines also take into account the domain name of the website and information about the person conducting the search, such as location (ascertained from the unique address of the user’s computer) and that computer’s search history with the search engine.

21 Research suggests that approximately 90% of internet users choose a link that is listed on the first page of the search results screen. An online business therefore has a strong incentive to try to optimise the ranking of its website in the organic search results shown on search results pages. For that reason, website owners will commonly seek to manipulate that ranking through search engine optimisation. This is a process of manually altering a website, or seeking to influence the number and nature of links to the website, so that the website will respond favourably to the algorithms applied by search engines and rank as highly as possible in the list of organic search results.

22 In addition to search engine optimisation, online businesses will commonly purchase paid search results in a process known as search engine marketing. That process is perhaps most usefully explained by reference to the advertising program used by Google known as AdWords. Research shows that approximately 94% of all search engine searches in Australia are carried out using the Google search engine.

23 Google allows advertisers to access the AdWords program to manipulate and monitor the performance of their advertisements. The program uses the pay per click advertising model in which the advertiser is only charged when a sponsored link is chosen or ‘clicked’ by an internet user. The advertiser selects in advance particular keywords that will trigger a paid search result on a search results page in response to particular keyword search terms entered by a user of Google’s search engine. In relation to the words selected, the advertiser indicates the amount that the advertiser is willing to spend if the triggered paid search result is clicked on by the user. This is known as the advertiser’s bid. The higher the bid, the more likely it is that the advertisement will appear in the search results when the internet user searches for that keyword or combination of keywords. In circumstances where many advertisers are utilising AdWords in relation to the same keywords, a ‘behind the scenes’ auction takes place that determines which advertisement will appear in the search results page in response to the user’s search request and the order in which those advertisements appear. In addition to the value of the advertiser’s bid, other matters are taken into account by Google’s paid search algorithm, including the relevance of the advertiser’s webpage to the keywords entered by the user.

24 An advertiser may elect to trigger advertisements by exact match, phrase match or broad match. An exact match will trigger a sponsored link only if the keyword search term entered by the searcher is the same as the keyword or keywords selected by the advertiser. A phrase match will trigger a sponsored link if the keyword search includes the keywords selected by the advertiser. For example, if an advertiser selects the keywords “houses for sale”, a phrase match may be triggered by the search terms “Edwardian houses for sale” or “houses in Melbourne for sale”. A broad match will trigger a sponsored link based on associations between the keywords entered by the user and the keywords selected by the advertiser, as determined by Google’s algorithm. For example, if the advertiser’s keywords are “houses for sale”, a broad match may be triggered by the search terms “homes for sale” or “houses to buy”.

REA’s property portal businesses – their branding, trade marks and promotion

25 REA’s property portal business commenced operation in 1998. Shortly thereafter the business changed the web address of its residential property portal to www.realestate.com.au. At that time the business was small, employing some 8 employees. Only about 40 of the 8,500 residential real estate agents in Australia listed their properties with REA at that time.

26 By 1999, REA had listed on the Australian Stock Exchange and had 34 employees in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Over the following decade, REA’s residential property portal business grew exponentially. By the end of 2002, it was the market leader in the Australian online real estate advertising market. Around that time, one in four real estate agents subscribed to the realestate.com.au property portal. By the end of the 2005 financial year, approximately 80% of all Australian real estate agents subscribed. By 2011, the proportion of real estate agents subscribing to REA’s property portals had increased to approximately 95%.

27 Online traffic to www.realestate.com.au also increased exponentially over the same period. In June 2000, the website had approximately 150,000 users. In the month of June 2011, the realestate.com.au website had 6.7 million visits from unique browsers (ie 6.7 million different computers accessed the website). To give some context to the magnitude of use involved, this number exceeded the number of visits made by unique browsers in June 2011 to the websites of some of the most well known daily metropolitan newspapers in Australia, such as The Age and The Australian. In the month of October 2011, the realestate.com.au website had visits from 6.8 million unique browsers and a total of over 16 million visits.

28 Using methodology similar to that used to estimate television ratings, statistical information presented by REA shows that in October 2011, the realestate.com.au website was visited by nearly twice as many people as its closest competitor and by more than six times as many people as its next closest competitor.

29 Until about 2002, commercial property listings were intermingled with residential listings on “realestate.com.au”. In 2002, REA launched the realcommercial.com.au portal promoting that business to medium sized commercial property agents and residential agents with some commercial listings. At that time, there were two large and successful dedicated commercial property portals. By 2005, the realcommercial.com.au business was the most popular commercial property portal in Australia. In May 2006, REA acquired one of the other popular commercial real estate portals to consolidate its position as the leading commercial property portal in Australia. In the month of January 2005 some 72,000 unique browsers visited realcommercial.com.au, rising to nearly 400,000 visitors in the month of October 2011. In October 2011, visits to the realcommercial.com.au website were nearly four times the visits to the closest rival of REA’s commercial real estate portal. At that time, there were some 1500 subscribing agents to the realcommercial.com.au property portal.

30 In June 2007, REA launched a holiday rental website known as “realholiday.com.au”. That website was sold in April 2011 and renamed. REA also operates a website which lists businesses for sale known as “realbusinesses.com.au”.

31 REA’s various portals refer to each other and contain hyperlinks so that an internet user may conveniently move from one site to the other.

32 There can be, and there was no issue, that REA’s residential and commercial real estate portals are popular sites with consumers and are extensively used by consumers to search for properties.

33 Given the popularity and market dominance of REA’s real estate portals, its branding has become relatively well known. The branding of a product facilitates a reputational connection between the consumer or potential consumer of a product and the product’s producer or provider. Brand recognition by consumers demonstrates an association in the minds of the consumer between the product and its provider or at least between the product and its brand. Some brands will focus on the identity of the provider others will not. Whether focused upon the owner’s name or the owner’s trading name for the product concerned, a brand enables an owner to establish a relationship between the consumer and the owner or between the consumer and the owner’s product or perhaps both.

34 A brand may be comprised of a number of brand elements such as a name, a logo and the use of a particular colour. In the case of REA’s residential property portal, there are four main brand elements utilised:

(a) the name “realestate.com.au” in lower case sans serif font;

(b) the silhouette of a house inside a button on a red background;

(c) the colour red as the background colour on the website; and

(d) the use of a tagline (which has varied from time to time) such as “Australia’s No 1 property site”.

35 The main brand elements (excluding the red background) are depicted in the following logo (“the realestate.com.au logo”):

36 The phrase “realestate.com.au” in the logo as shown above, (but excluding the tag line) comprise composite trade marks for which the first applicant has been the registered owner in respect of services in classes 36 and 42 since October 1999 and in respect of classes 9, 35 and 38 since September 2005. Since February 2002, the first applicant has also been the registered owner of a similar trade mark in respect of services in classes 36 and 42. In that trade mark “.com.au” is displayed in a font size much smaller than the font used to display “realestate” (collectively “the realestate.com.au trade marks”). Relevantly, class 36 services include: “Real estate affairs, including the provision of access to real estate information and analysis over a global computer network…” Class 35 includes “advertising of real estate in electronic…format”.

37 In the case of REA’s commercial property portal, there are also four main brand elements utilised:

(a) the name “realcommercial.com.au” in lower case sans serif font;

(b) a silhouette of commercial buildings inside a button on a blue background;

(c) the colour blue as the background colour on the website; and

(d) a tagline which often accompanies the other elements such as “Australia’s No 1 commercial property site”.

38 The main brand elements (without the blue background) are depicted in the following logo:

39 Since November of 2002, the first applicant has been the registered owner of a composite trade mark comprising the logo shown above (but excluding the tag line) (“the realcommercial.com.au trade mark”) in respect of classes 9, 35, 36 and 42.

40 Each of the brand elements for the realestate.com.au and realcommercial.com.au portals have been extensively used by REA on the websites of those businesses where the logos appear as the title to each webpage.

41 In order to promote awareness of its brands and drive traffic to its websites, REA has promoted the realestate.com.au and realcommercial.com.au portals (including the brand elements described) in a number of different ways. Since 2005, advertising campaigns have usually been conducted in spring and autumn of each year involving online “banner” advertising as well as television, radio, cinema, print and outdoor advertising. A recent example of such an advertising campaign involved the expenditure of some $900,000. That campaign included expenditure on outdoor media spread between billboards, mobile scooters and bus shelter advertising. It also involved print media advertising in 3 metropolitan areas and some 66 radio advertisements across 4 cities.

42 Between 2005 and 2011, REA purchased more than $9m of advertising to promote the realestate.com.au portal. Between 2006 and 2011 (not including 2010 for which figures were not provided), REA purchased about $510,000 of media advertising to promote the realcommercial.com.au portal.

43 Whilst REA’s advertising spend is significant, as REA’s General Manager of Brand Communications and Insights Ms Joanne Whyte said, REA’s advertising budget for traditional advertising is not significant compared with the media spend which might be required in order to create consumer awareness about a more traditional consumer product. In an offline environment, a great deal of advertising effort is required to build a brand in the marketplace so that consumers are familiar with it and are persuaded to consider a purchase. In the case of a property portal, the consumer has for the most part already decided to look for property online and REA’s predominant objective is to bring that consumer to its website. Accordingly, REA regards the most important aspect of its advertising and promotional activities to be its search facilitation efforts. Those activities primarily comprise search engine optimisation used to enhance the exposure and ranking of REA’s websites in organic search results and search engine marketing to place sponsored links to the realestate.com.au and realcommercial.com.au portals on search results pages.

44 REA has a dedicated team responsible for search engine optimisation and search engine marketing activities. That team is charged with the primary role of increasing the amount of traffic REA’s websites receive from search engine searches. REA’s search engine optimisation specialists design the structure of REA’s web pages so that they are able to be indexed by search engines quickly and so that REA’s websites are ranked highly in organic search results for the most common real estate searches. That involves ensuring that web pages that make up REA’s websites contain appropriate information in their title, visible text and in the metadata that lies behind each web page, as well as in the links that connect the web page to other web pages within the group of pages that make up the websites.

45 In part because of REA’s search engine optimisation activities, as at December 2011, the realestate.com.au website had 1,428,071 of its web pages indexed in Google and the realcommercial.com.au website had 580,974 pages indexed in Google. At that time, some 4,500 websites on the world wide web contained links to the realestate.com.au website.

46 REA has engaged in search engine marketing in order to promote the realestate.com.au business since at least 2005. Consultants are utilised to assist REA with search engine marketing. REA’s ultimate aim is to achieve a high click through rate with a low average cost per click for terms that REA bids on. As at December 2011, REA was bidding (through AdWords) on a total of over 3.6 million keywords across 22 segmented campaigns for the realestate.com.au and realcommercial.com.au portals.

47 Between 2009 and 2011, REA’s total expenditure on search engine marketing in relation to its realestate.com.au portal, including amounts paid to search engines and to consultants, exceeded $1m per annum. During that period REA’s expenditure on search engine marketing for the realcommercial.com.au portal ranged between $200,000 and $300,000 per annum.

48 In the 2010-2011 financial year, the “realestate.com.au” website received more than 10 million ‘clicks’ from sponsored links or paid search results. Compared to the 2008-2009 financial year, REA doubled its expenditure on pay per click advertising and nearly tripled the total number of ‘clicks’ to the realestate.com.au website. A similar increase in both the cost of advertising and total number of ‘clicks’ was experienced for the realcommercial.com.au portal, which in the 2010-2011 year generated nearly 850,000 ‘clicks’ through pay per click sponsored links.

49 REA’s promotional activities include electronic marketing for consumers who have opted to receive ‘email alerts’. As at January 2011 in excess of 1.7 million users were registered for email alerts via the realestate.com.au portal and almost 100,000 users were registered for email alerts via the realcommercial.com.au portal. Those users were sent in excess of 18 million emails in that month. Additionally, REA markets directly to the real estate industry, including by sending promotional material to real estate agents to provide to clients and by sponsoring industry events.

50 To promote and drive traffic to its websites, REA has also entered into various syndication agreements with owners of other popular websites. For instance, REA has a syndication agreement with eBay. Users of that website who navigate to eBay’s real estate or property section are taken to a co-branded webpage which displays both eBay’s name and logo alongside the “realestate.com.au” name and logo. Typically a syndication partner is paid for each unique browser that is directed to the realestate.com.au site from the syndication partner’s site. Since 2006, REA has spent over $4.7m on syndication arrangements.

Real Estate 1’s property portal businesses – their branding, trade marks and promotion

51 Geoffrey Luff is a director of each of the corporate respondents. He was the person primarily responsible for the establishment of the Real Estate 1 business and has been the principal decision-maker and controller of Real Estate 1’s affairs. He has worked in and owned various real estate agencies in and around the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria.

52 In 2005 he decided to set up a franchise business for real estate agencies which was to be called “Real Estate 1”. Part of the plan was to set up an online property portal on which real estate agents could list properties for sale. The business name “Real Estate 1” was registered in July 2006. An attempt was made at that time to obtain the domain name “realestate1.com.au” but it was unavailable. As a result Mr Luff caused to have the domain name “realestate1.net.au” registered to a company that he controlled. Mr Luff was aware of REA’s realestate.com.au property portal business and understood that the property portal he intended to establish would be in direct competition with REA’s portal.

53 Little or no activity to progress the establishment of the planned business occurred in 2007, other than that Mr Luff and his wife Julie (the fourth respondent) became the registered owners of a trade mark, being a composite mark in classes 36 and 42, comprising the word “realEstate” in varied font, arranged with a stylised number 1 forming part of a stylised house image, over a curved line (as shown at [55] below) (“the realestate1 trade mark”).

54 In February 2008, Mr Luff arranged for a number of domain names to be registered including “re1commercial.com.au”, “realestate1commercial.com.au”, “realcommercial1.com.au” and “realcommercial1.net.au”. Around that time, discussions were held and work commenced on the creation of a website for Real Estate 1’s property portal. Also at about that time, Mr Luff decided that he would not pursue the franchise aspect of the intended Real Estate 1 business and instead planned to focus solely on providing online advertising services through a property portal. In March 2008 the second respondent was incorporated with the intent that it would run the Real Estate 1 business.

55 On 30 October 2008 Real Estate 1 launched a portal for listings of residential property for sale and rent with the domain name “realestate1.net.au”. At the same time, a further website was launched with the domain name “commercial1.net.au”. This portal was intended for listings of commercial real estate for sale or lease. On each page of the residential property website the realestate1 trade mark appeared as a logo in the title of the page. The logo included the words “realEstate1” accompanied by a silhouette of a house in an orange colour over an orange coloured curved line, as follows:

56 A similar logo (for which Real Estate 1 has not held a registered trade mark) in which the term “commercial1” appeared, was utilised in the title of Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal, as follows:

57 In November 2008, Mr Luff acquired the domain name “realestate1.com.au” and the second respondent became the registrant of that domain name.

58 In March 2009, Real Estate 1’s residential property portal was (to use Mr Luff’s words) “re-branded as realestate1.com.au”. The logo at the top of the web pages on the website was altered so that the words “.com.au” appeared following the silhouette of the house as shown below:

59 This logo was used by Real Estate 1 for its residential property portal between March 2009 until on or about the commencement of this proceeding on 21 October 2010. During that time, the logo appeared prominently on the title of each webpage on the website. Also during that time, the text on the website variously referred to the business operating the website as “realEstate1” or “Real Estate One” or “realestate1.com.au”.

60 In the period March 2009 to about October 2010, the logo set out at [58], was also used in advertising and promotional material for Real Estate 1’s residential property portal. The evidence suggests that about $50,000 was expended by Real Estate 1 on traditional advertising (mainly radio advertising) during the period. Additionally, Real Estate 1 produced brochures, key rings and bumper stickers for distribution to agents and their clients. Forms distributed to agents also contained the “realestate1.com.au” logo as did the signage on the vehicle used by Real Estate 1’s sales representative. Real Estate 1 regarded the use of its domain name “realestate1.com.au” as vital for its advertising, given that it was trading online.

61 On 23 November 2009, the first respondent was incorporated with the intent that it would take over the Real Estate 1 business. A number of investor presentations were made at or about that time to which I will later refer. Offer documents and a prospectus issued to prospective investors in the first respondent also utilised the logo set out at [58].

62 In response to this litigation and from about late October 2010, the “.com.au” was removed from the logo appearing in the title of web pages on Real Estate 1’s residential property portal. The logo used reverted to a mark consistent with the realestate1 trade mark.

63 However, Real Estate 1 continued to use the domain name “realestate1.com.au” and operate its residential property portal from a URL containing that domain name. Beyond its use as part of an internet address, there is evidence of some minor continued use of the name “realestate.com.au”. The signage on Real Estate 1’s motor vehicle was not altered; the logo containing the domain name continued to appear in some minor references to Real Estate 1’s residential property portal made on Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal; and on one page on the “realestate1.com.au” website a reference is made to the domain name which suggests that the website is operated by a business of that name. A similar reference equating the name of the operator of the business to its domain name, is made on a web page for Real Estate 1’s residential property portal that is accessible to users of mobile phones.

64 Between August 2009 and about late October 2010 (when the proceeding was commenced), Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal was conducted at a URL address which included the domain name “realcommercial1.com.au” and was otherwise carried out under the name “realcommercial1.com.au” by reference to a logo which incorporated that name accompanied by a silhouette of a commercial building on a blue background over a curved line, as follows:

65 The logo was used in the title of each of the web pages on Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal. In response to this litigation and from about late October 2010, the domain name for Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal was changed to “realestate1commercial.com.au” and the branding on the website was altered to “realEstate1Commercial” with a logo as follows:

66 Within about three weeks of the launching of Real Estate 1’s property portals in late 2008, some 150 real estate agents had registered with Real Estate 1. Those numbers increased over time. By December 2010, there were 1,036 agents registered. As at February 2012, there were 1875 agents registered. Agents registered with Real Estate 1 may either take up a free or a paid subscription. An agent with a free subscription can upload an unlimited number of properties to the website. A paid subscription (at a cost of $100 per month) provides access to additional features and tools. The extent to which real estate agents pay for subscriptions was not identified in the evidence.

67 In the period 1 April 2009 to 31 January 2012, just over 900,000 visits were made to the realestate1.com.au website. Some 78% of that traffic came from search engines. Real Estate 1 has engaged in search engine marketing since at least April 2009 and search engine optimisation since July 2009.

68 Despite those efforts, and whilst I accept that it is a competitor of REA, Real Estate 1 must be regarded as a relatively insignificant participant in the property portal market. In the month of October 2011, when realestate.com.au ranked as the number one property portal in Australia with over 16 million visits representing some 34% of total visits to property portals, the realestate1.com.au website ranked at 121 with about 25,500 visits representing 0.0544% of total visits to property portals. Financial reports for Real Estate 1 show that in the financial year ended 30 June 2011 it had a gross profit from trading of about $325,000 and a net operating loss of about $182,000.

trade practices and passing off claims

REA’s Pleaded Claims

69 REA pleaded that the domain name “realestate1.com.au” is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the domain name “realestate.com.au” and that the domain name “realcommercial1.com.au” is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the domain name “realcommercial.com.au”. It also pleaded that the trade indicia by reference to which Real Estate 1’s residential and commercial property portal businesses have been conducted since March 2009 (mostly detailed at [58]-[65] above), are substantially identical or deceptively similar to the trade indicia by which the realestate.com.au and realcommercial.com.au businesses have been conducted (mostly detailed at [34]-[39] above).

70 By reference to the use (on its websites, in advertising and in promotional materials) by Real Estate 1 of names and trade indicia that are claimed to be substantially identical or deceptively similar to those employed by REA, REA pleaded that Real Estate 1 has and continues to make false representations to the public which may be summarised as follows:

(a) Real Estate 1’s residential property portal business is a business of, or service of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA;

(b) Real Estate 1’s commercial property portal business is a business of, or service of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA;

(c) the realestate1.com.au website is a website of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA; and

(d) the realcommercial1.com.au website is a website of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA.

71 By reason of that conduct, REA pleaded that Real Estate 1 had:

(a) engaged in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 52 of the TPA;

(b) represented, in connection with the supply of its services, that those services have the sponsorship and approval of REA when they do not have such sponsorship or approval, in contravention of section 53(c) of the TPA; and

(c) represented that it has the sponsorship or approval of, or an affiliation with REA that it does not have, in contravention of section 53(d) of the TPA.

72 Additionally, by reason of that same conduct, REA pleaded that Real Estate 1 had passed off:

(a) its residential property portal business as a business of, or service of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA;

(b) its commercial property portal business as a business of, or service of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA;

(c) the realestate1.com.au website as a website of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA; and

(d) the realcommercial1.com.au website as a website of, or associated with, authorised or approved by, REA.

73 REA complained that by its conduct Real Estate 1 had injured, and if not restrained will continue to injure, the goodwill and reputation of REA in relation to:

(i) the domain name “realestate.com.au”;

(ii) the domain name “realcommercial.com.au”;

(iii) the trade indicia utilised by the realestate.com.au business; and

(iv) the trade indicia utilised by the realcommercial.com.au business.

74 As I will later explain, REA’s case as expounded at trial was much narrower than that pleaded. At this point I should say that the claimed contraventions of s 53 of the TPA were not pressed as other than supplementary to the s 52 claim and on the basis that their fate would be no different to that of the s 52 claims. The parties approached the s 52 claims and the claims of passing off in the same way. REA did not contend that there was a basis for it succeeding on its passing off claims if it failed on its s 52 case. A range of issues common to both the s 52 and passing off claims arise for determination and I have dealt with them in tandem but have expressed my consideration of them by reference to the s 52 claims.

misleading or deceptive conduct

The relevant statutory provisions

75 At the time of the commencement of this proceeding, the applicable legislative provisions were contained in the TPA. In late 2010, the title of the TPA and a number of its provisions were amended by the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 2) 2010 (Cth) and its short title became the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The transitional arrangements provide that the TPA provisions continue to apply to conduct occurring prior to 1 January 2011.

76 As outlined above, REA alleges that the respondents have engaged in conduct that contravenes ss 52, 53(c) and 53(d) of the TPA. Those provisions are in the following terms:

52 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in the succeeding provisions of this Division shall be taken as limiting by implication the generality of subsection (1).

53 False or misleading representations

A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, in connexion with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connexion with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…..

(c) represent that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits they do not have;

(d) represent that the corporation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation it does not have;

Some general principles

77 The principles underpinning s 52 are for the most part well established and were not in dispute. Some general principles are dealt with here, whilst principles requiring particular consideration are dealt with later in these reasons.

78 Section 52 establishes a standard of conduct that traders must adhere to in their dealings with consumers. A rival trader, consumers and the regulator are each entitled to bring an action in respect of a contravention of this standard.

79 Conduct which causes confusion or wonderment will not necessarily be misleading or deceptive: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 294 ALR 404 at [8] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ). If the conduct of a corporation gives rise to confusion and uncertainty in the minds of the public about whether two products or services might have come from the same source, the corporation does not necessarily contravene s 52: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 200 (Gibbs CJ); Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 201 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ); Bridge Stockbrokers Ltd v Bridges (1984) 4 FCR 460 at 472-473 (Lockhart J). However, if the conduct of a corporation causes more than mere confusion and causes consumers to actually conclude that two products do come from the same source, such conduct is likely to be misleading and deceptive: Bridge Stockbrokers at 473 (Lockhart J). The representee must be led into error and labour under an erroneous assumption: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [104] (the Court).

80 The provision does not preclude a rival trader from entering the market and copying the product of another in an attempt to take some of its market share (subject to any infringement of property rights), provided the rival does not mislead or deceive consumers or pretend that its goods are the goods of another: Peter Bodum A/S v DKSH Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 280 ALR 639 at [202] (Greenwood J, with whom Tracey J agreed); citing Interlego AG v Croner Trading Pty Ltd (1992) 39 FCR 348 at 391-392 (Gummow J, with whom Black CJ and Lockhart J agreed).

81 The High Court in Google Inc explained that the words “likely to mislead or deceive” make clear that it is not necessary to demonstrate actual deception to establish a contravention of s 52: Google Inc at [6] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ). Evidence of actual deception may be persuasive but is not essential, the test is objective and the court must determine for itself whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive: Taco Bell at 202 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ).

82 In cases involving representations made to an indeterminate number of people, the court must first determine the class of people to whom the representation was made and the likely attributes of the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of that class. The High Court in Campomar explained (at [102]-[103]):

It is in these cases of representations to the public, of which the first appeal is one, that there enter the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers. Although a class of consumers may be expected to include a wide range of persons, in isolating the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of that class, there is an objective attribution of certain characteristics. Thus, in Puxu, Gibbs CJ determined that the legislation did not impose burdens which operated for the benefit of persons “who fail[ed] to take reasonable care of their own interests”. In the same case, Mason J concluded that, whilst it was unlikely that an ordinary purchaser would notice the very slight differences in the appearance of the two items of furniture in question, nevertheless such a prospective purchaser reasonably could be expected to attempt to ascertain the brand name of the particular type of furniture on offer.

Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or from whom a relevant fact, circumstance or proposal was withheld, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted. (Citations omitted)

See further, Google Inc at [7] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ).

83 The initial question that must be determined is whether the misconceptions or deceptions alleged to arise or to be likely to arise, can properly be attributed to the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of the class: Campomar at [105] (the Court).

84 A different approach is to be taken where the target of the impugned conduct is an identified individual: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [36] (Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ); Eatock v Bolt (2011) 197 FCR 261 at [244]-[246] (Bromberg J).

85 A number of judges of this Court have held that in order for conduct to breach s 52, it must be established that a “not insignificant” proportion of people to whom representations were made, would be misled or deceived by the impugned representation. In .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd (2004) 207 ALR 521 at [21]-[26], Finkelstein J listed the relevant authorities and traced that requirement to the law of passing off and its consequent application to s 52. The judge was critical of that approach including because he thought it inconsistent with the test adopted by the High Court in Campomar: see discussion in Bodum at [206]-[210] (Greenwood J, with whom Tracey J agreed). In the absence of express High Court authority I am bound to follow the approach expressed by Greenwood J (with whom Tracey J agreed) in Bodum. Applying this approach, it appears that once certain objective characteristics have been attributed to ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of the class, there remains scope for some diversity of response to the impugned conduct. It is then necessary to ask whether a “not insignificant” proportion of ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of the class were misled or likely to be misled.

86 Section 52 is not directed to the intention of a party and it is possible for a contravention to occur even where a party has acted reasonably and honestly: Google Inc at [9] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ); Hornsby v Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 (Stephen J).

Is the impugned conduct that of Real Estate 1?

87 An assessment of whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to be so, should logically commence with the identification of the impugned conduct. Where the impugned conduct is a representation, it is necessary to determine whether the representation was made by the alleged contravener. The conduct here in question is clear. It includes, as I have indicated already, the use of either “realestate1.com.au” or “realcommercial1.com.au” displayed in sponsored links and organic search results which relate to the property portals of Real Estate 1.

88 Although the matter was not the subject of direct evidence and was only dealt with in general terms, there was no issue that the content of sponsored links paid for by Real Estate 1 was content created by Real Estate 1 and that the representations there made was conduct of Real Estate 1. Nor was it suggested by Real Estate 1 that the content of organic search results for its property portals was not authored by it or that representations there contained were not the conduct of Real Estate 1. Although the heading, URL and page description which appear in an organic search result are technically determined by the search engine, Real Estate 1 includes on its web pages metatags for both the heading and page description designed to facilitate the adoption and display of that content in organic search results.

The relevant class

89 To determine whether Real Estate 1’s conduct was misleading or deceptive, it is necessary to make findings about how consumers would have perceived that conduct including, whose conduct consumers would have perceived the conduct to be and what, if any, representations would have been perceived to flow from the conduct.

90 In order to carry out that task, it is necessary to identify the class of consumers to whom the impugned representations were made. Further, because the Court must consider whether the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of that class would be misled or deceived, it is necessary to identify the class by reference to the characteristics of the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons in the class.

91 Whilst the identity of the relevant class is fairly straightforward, the determination of the characteristics which ought to be ascribed to the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons in the class is more difficult and more crucial to the result that I have reached. I will identify shortly some general characteristics which I consider should be ascribed and deal later with further specific characteristics that are of particular relevance.

92 In determining the characteristics that ought to be ascribed to the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons in the class, I have been somewhat assisted by evidence called by REA from Brent Coker. Mr Coker is a lecturer in Marketing at the University of Melbourne and REA relied upon his evidence as the opinion of an expert. He holds a PhD in Information Systems and Electronic Commerce amongst other qualifications. Mr Coker has been involved in extensive research and I am satisfied has some expertise in online consumer behaviour and internet marketing. The evidence which Mr Coker gave about online consumer behaviour was only partly based on formal research. Much of Mr Coker’s evidence and all of the evidence given by Phillip Leahy (an online marketing and sales professional with 15 years experience in online marketing, who was called by Real Estate 1) was based on the witness’s familiarity with the nature and content of a search results page and what the witness regarded as the likely plausible reactions of consumers, given the type of search engaged in and the information likely to be presented on the search results page.

93 Having become acquainted, through the evidence, with the way in which search engines operate and with the nature and likely content of information displayed on search engine results pages, the Court was as well placed as were Mr Coker and Mr Leahy to make judgments about the likely plausible behaviour of consumers. I have some doubt as to the extent to which much of the evidence given by Mr Coker and all of Mr Leahy’s evidence, can properly be characterised as expert evidence. That is not to say that the Court was not assisted by the evidence given, in the same way that the Court may be assisted by submissions. I was assisted by some of Mr Coker’s evidence although I have not accepted many of his conclusions. In the main that is because Mr Coker’s views were given without taking into account many surrounding facts of importance to which I will later refer. To some extent, Mr Leahy’s conclusions were similar to those made by Mr Coker. To some extent their conclusions differed. Objection was taken to the expertise of Mr Leahy and the admissibility of his evidence. As I was not assisted and I have not relied upon conclusions made by Mr Leahy, it is not necessary that I determine the objection.

94 The characteristics to be attributed to the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons in the class which the High Court considered in Google Inc, were findings made at first instance by Nicholas J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trading Post Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 197 FCR 498. Nicholas J had to determine whether representations made in sponsored links were misleading or deceptive. Given the similarity of the consumer transactions dealt with in that case to those in this case, I have also been assisted by the characterisation of the relevant class and their attributes as found by Nicholas J in Trading Post.

95 The identification of the relevant class was not particularly controversial. The class consists of people who have access to a computer connected to the internet and who use search engines to view real estate listings on property portals. The class, therefore is actual or prospective users of REA’s property portals: Bodum at [205] (Greenwood J, with whom Tracey J agreed). ‘Ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons within that class will have at least a basic knowledge and understanding of computers, the internet and of how to use search engines.

96 The level of familiarity of such persons with the functionality of search engines and the nature and content of a search results page means that such persons are likely to understand that:

(i) search results include advertisements (which are identified as such) and other results;

(ii) the advertisements or ‘sponsored links’ will, like all advertisements, be paid for by the advertiser, contain content provided by the advertiser and are likely to have a prominence of place on the search page referrable to the payment made by the advertiser;

(iii) the other results (the organic search results) are generated and ordered by the search engine predominantly by reference to the relevance of the websites displayed to the keywords searched for by the searcher; and

(iv) the content of the organic search results has likely been taken by the search engine from the web page or website whose URL is displayed in the result and as such, the words displayed are likely to be those of the web page and not words authored by the search engine.

97 As a result of the consumers’ understanding set out at (ii) and (iii) above, the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ persons in the class will understand that an organic search result is likely to be more relevant to the information searched for than a sponsored link, and that the most relevant organic results will appear in order of relevance commencing with the first result. In that latter respect, I accept Mr Coker’s evidence which included reference to research that demonstrated that a consumer will click onto the first organic search result displayed on a search results page on some 42% of occasions and that the first five positions have approximately a 76% chance of being chosen, and that 90% of consumers do not visit page 2 or beyond.

98 By reason of (i) and (ii) above, the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ member of the class will perceive that representations made in or by a sponsored link are representations of the advertiser. At least in respect of on-line businesses which trade through the internet, the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ person will perceive a representation made in or by an organic search result relating to such a business, as a representation made by the business concerned.

99 I also ascribe to the ordinary and reasonable members of the class, a basic understanding of general internet conventions. This includes an understanding that “.com” is commonly used by commercial entities and “.au” by Australian based entities, as well as knowledge that every web page has a unique URL and that any variation between one URL and another is significant and indicative of a different web page or website.

Are REA’s names distinctive of its businesses?

100 Before going on to consider whether a not insignificant proportion of the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of the relevant class were likely to have been misled or deceived, it is necessary to say something about the distinctiveness of the REA domain names which are used as the trading names for its residential and commercial property portals and to consider whether these names have acquired a secondary meaning.

101 As outlined earlier, REA alleges that Real Estate 1 adopted names and trade indicia substantially identical or deceptively similar to those of REA’s property portal businesses, such that Real Estate 1 represented that its property portals were affiliated or connected with REA. To make good this allegation, REA must establish that its names have acquired a secondary meaning and have become distinctive of its businesses. After all, consumers who are not familiar with “realestate.com.au” as the name for REA’s residential property business could not possibly be misled or deceived into believing that a reference to “realestate1.com.au” is a reference to the business of realestate.com.au or an associated business. Therefore, the extent to which consumers associate the names “realestate.com.au” and “realcommercial.com.au” with REA’s online property portal businesses is an important issue in this case.

102 No evidence was called by REA directly from consumers in relation to consumer familiarity with the name, brand or reputation of REA’s portals. Instead, REA relied on the promotion of its brands and the very substantial use of its websites by consumers, to establish a substantial reputation in its property portals and their association in the minds of consumers with REA’s property portal businesses.

103 That REA has established substantial brand recognition by consumers for its residential and commercial real estate portals is not in issue. Real Estate 1 conceded that by the use of the combination of the brand elements used to promote REA’s residential and commercial real estate portals, REA has developed a reputation in the Australian market. It was not suggested that the combination of those brand elements were not, in each case, sufficient to be distinctive of REA’s portal businesses.

104 Real Estate 1 relevantly contended that what REA had failed to establish was that the term “realestate.com.au”, when appearing on a search results page, had become distinctive of REA’s business. Given the specific nature of the impugned conduct expounded at trial (see further at [136]-[137] below), REA needed to establish that when “realestate.com.au” appeared in a search result, that term was distinctive of REA’s residential portal business.

105 It is difficult to establish that a descriptive name, as opposed to a concocted or invented name, is a name which has become distinctive of a trader’s business: Cellular Clothing Co Ltd v Maxton & Murray [1899] AC 326 at 336 (Earl of Halsbury LC). Whether a name is distinctive of a particular business is a question of fact and degree: Architects (Australia) Pty Ltd v Witty Consultants Pty Ltd [2002] QSC 139 at [19] (Chesterman J). A concocted name is far more likely to be distinctive of a business than a name which is based upon a description of the nature of the business that is being conducted: Chase Manhattan Overseas Corporation v Chase Corporation Ltd (1985) 9 FCR 129 at 147 (Wilcox J). Whilst a name may at the same time be both descriptive and distinctive, the fact that a name prima facie retains its descriptive signification increases the difficulty of proving that it is distinctive of the goods of a particular business: Burberrys v JC Cording & Co (1909) 26 RPC 693 at 704 (Parker J); British Vacuum Cleaner Co Ltd v New Vacuum Cleaner Co Ltd [1907] 2 Ch 312 at 322-323 (Parker J); and South Australian Telecasters Limited v Southern Television Corporation Limited [1970] SASR 207 at 220 (Walters J).

106 In Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Apand Pty Ltd (1993) 46 FCR 152 at 165-6, Burchett J stated:

“Of course, the mere fact that a word is descriptive does not warrant a trader in using it if it has also acquired a secondary meaning as to distinguish the products of a rival. As Lord Radcliffe said in de Cordova v Vick Chemical Co (supra) at 106:

‘To say that it is descriptive would not be enough, for…there is no absolute incompatibility between what is descriptive and what is distinctive. A descriptive word, such as ‘Sheen’, can be recognised in law as distinctive if the evidence clearly shows that it is distinctive in fact”.

107 In Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 8 at [108] and by reference to the judgment of Lockhart J in Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals (1991) 30 FCR 326, Emmett J set out what is meant by the requirement that a term be “distinctive”. Whilst the analysis was given in the context of a trade mark case, it bears repeating here:

There must be a sufficient degree of distinctiveness to counterbalance the descriptive character of a word. A word that is prima facie descriptive may become distinctive in connection with particular goods but yet retain its descriptive meaning. However, the word must, to become distinctive, have a new and secondary meaning different from the descriptive one, and thus cease to be purely descriptive. Distinctive means that the mark distinguishes the registered proprietor’s goods from others of the same type in that market. However, distinctive does not mean that the goods must specifically identify the registered proprietor as the source of the goods. What is important is that a significant number of consumers in the relevant market identify the registered proprietor’s goods as coming from one trade source (Johnson & Johnson at 335-336).

108 Examples of names which have been held to have achieved the requisite secondary meaning have included “Minties” (for mints): Angelides v James Stedman Hendersons Sweets Ltd (1927) 40 CLR 43 at 72; “Budget Rent a Car” (for car rental services): BM Auto Sales Pty Ltd v Budget Rent a Car System Pty Ltd (1976) 12 ALR 363 at 369; “Opals Australia” (for opal sales): Opals Australia Pty Ltd v Opal Australiana Pty Ltd (1993) ATPR 41-264; “Microwave Cuisine” (for microwave cooking classes): LSK Microwave Advance Technology Pty Ltd v Rylead Pty Ltd (1989) 16 IPR 107 at 114; and “Architects Australia” (for architectural services): Architects Australia at [15]-[24]. In each case, the evidence before the court showed that the names, though descriptive, had come to be associated by consumers with the goods or services of a particular trader. Examples of names which have been held not to achieve the requisite secondary meaning have included “Flexibond” (for an investment product): Lumley Life Ltd v IOOF Friendly Society (1989) 16 IPR 316; “Cellular” (for a type of cloth): Cellular Clothing; “Office Cleaning Services” (for a cleaning business): Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners (1946) 1 All ER 320; and “British Vacuum Cleaner Company” (for a company that held a patent for particular vacuum cleaner technology): Vacuum Cleaner Case. Whilst each of these cases is illustrative of the relevant principles, each turns on its particular facts. The facts of this case support a finding that REA’s domain names have become distinctive, in the sense that they distinguish REA’s property portals from other portals in the same market.

109 The very substantial efforts engaged in by REA to advertise and promote its portal businesses and the very substantial success of those businesses make it abundantly clear that the businesses are both popular and well-known to a significant number of Australian consumers of property portal services. Whilst the logos and other brand elements that are used to promote the businesses contribute significantly to consumer recognition of those businesses, I accept REA’s contention, including the evidence of Mr Coker, that (in each case) the name is the dominant brand element. Whilst I find in the following part of this judgment that as a term, “realestate.com.au” is only faintly recognisable as an intended name for a brand or business, nonetheless I consider that the nature and extent of the advertising of the term in connection with REA’s residential portal, makes it likely that when “realestate.com.au” is displayed as a trading or domain name for that portal, it is recognised as such by a significant number of Australian consumers who use property portals. Reputation may be inferred from a high volume of consumer use, together with substantial advertising expenditure and promotion: McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335 at [86]-[88] (Kenny J); Playcorp Group of Companies Pty Ltd v Peter Bodum A/S (2010) 84 IPR 542 at [84] (Middleton J).

110 The manner in which consumers reach REA’s websites also strongly favours a finding that REA’s domain names are distinctive of its property portal businesses because those names are utilised by consumers when trying to locate those businesses. Analytical tools capable of tracking and recording the source of traffic coming to a website have been utilised by REA to show the source of internet traffic to REA’s websites. In the first six months of 2011, some 53% of visits to the realestate.com.au website came from direct traffic. Direct traffic refers to those visits made to a website when an internet user has typed the web address for the website into the user’s web browser, or has clicked a saved link to that web address (for example, a link saved as a ‘favourite’ link). Access through a saved link does not evidence name recognition but other access via a web browser does. Whilst no breakdown was available which identified the proportion of direct traffic that arrived directly from a web browser, I would infer that a very significant number of consumers have gained access in that way. Given the very substantial numbers overall, there must be many hundreds of thousands of consumers in that category.

111 More specific evidence was produced that suggests very substantial consumer familiarity with the term “realestate.com.au”. In July 2010, the most popular search term driving traffic to the realestate.com.au website from organic search results was the term “realestate.com.au”. Some 6% of all traffic arriving at the realestate.com.au website arrived as a result of a searcher using that keyword phrase. Between 9 November 2011 and 9 December 2011, on about 1 million occasions, consumers came to the realestate.com.au website having clicked on an organic search result that was displayed because the consumer used “realestate.com.au” as the keyword search term. In the same period, on about 110,000 occasions, consumers arrived through a similar path having used “www.realestate.com.au” as a keyword search term.

112 That “realcommercial.com.au” is a term which consumers associated with REA’s commercial property portal was not in contest. Although the term “realcommercial” is made up of two descriptive words, its nature differs from that of “realestate.com.au”. A series of descriptive words may be so organised as to create a unique and distinctive name for a product, as the “Healthy Fishing-Rod” example given by Isaacs J in Angelides at 62 demonstrates. When the words “real” and “commercial” are combined, a concocted word is formed by the combination. A concoction is rarely plain and usually memorable, including because the creation of something new will be thought to be clever or inspiring or at the very least unique. It is therefore not very difficult to establish that a concocted name used in connection with a business has acquired, in the minds of consumers, an association with that business.

113 The term “realcommercial.com.au” is not strongly descriptive of a property portal in the way that “realestate.com.au” is. The addition of “.com.au” to the concocted word will be readily recognised as merely indicating the online focus of the business concerned.

114 The extent of advertising and promotion of REA’s realcommercial.com.au website was sufficiently apparent from the evidence to lead me to infer that it has been significant if not substantial. The popularity of the site confirms its extensive use and strongly suggests that the business has strong name recognition amongst consumers interested in commercial real estate. There was also evidence of the use of the name “real commercial” by consumers when trying to locate the realcommercial.com.au website. In July 2011, the keyword search term “real commercial” was one of the two leading search terms driving traffic to the realcommercial.com.au website. It accounted for about 2% of the traffic arriving at realcommercial.com.au. The search term “realcommercial.com.au” also accounted for 0.7% of traffic.

115 It is clear a significant number of consumers who utilise search engines to search for property portals, recognise REA’s residential property portal by the name “realestate.com.au”. This is also the case in relation to REA’s commercial property portal and the name “realcommercial.com.au”. Accordingly, I am satisfied that secondary meaning has been established in the terms “realestate.com.au” and “realcommercial.com.au” and that a significant number of consumers associate these terms with REA’s online property portal businesses.

Causation and the extent of differentiation required to avoid deception

116 When a descriptive name is used to identify a brand or business, any misconception on the part of consumers may be the result of the indistinct name adopted by the business rather than any conduct on the part of its competitor. Further, in relation to the use of descriptive names, small differences in the names used by competitors will suffice to avoid misconception by consumers. The principles established in Hornsby bear heavily on these questions and need now to be discussed before I turn more specifically to the question of whether ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of the relevant class were likely to have been misled. In particular, I have in mind what Stephen J said on the issue of causation and the use of descriptive words as trading names. In Hornsby, Stephen J (with whom Jacobs J agreed) delivered the leading judgment. Barwick CJ (with whom Aickin J agreed), also expressed agreement with Stephen J, insofar as Stephen J’s reasoning supported the conclusions of Barwick CJ.

117 Why misconception has arisen in the minds of consumers was the springboard question posed by Stephen J in Hornsby. That focus upon causation was endorsed by the High Court in Campomar at [98] in requiring that there be established a “sufficient nexus” between the impugned conduct and any misconception or deception: see also Bing! Software Pty Ltd v Bing Technologies Pty Ltd (2009) 180 FCR 191 at 204 (Kenny J, with whom Greenwood and Logan JJ agreed); Dairy Vale Metro Co-operative Ltd v Brownes Dairy Ltd (1981) 35 ALR 494 at 501-502 (Toohey J); Snyman v Cooper (1989) 91 ALR 209 at 226 (von Doussa J). In Taco Bell at 203 Deane and Fitzgerald JJ said:

Finally, it is necessary to inquire why proven misconception has arisen: Hornsby Building Information Centre v Sydney Building Information Centre (18 ALR at 647 140 CLR at 228). The fundamental importance of this principle is that it is only by this investigation that the evidence of those who are shown to have been led into error can be evaluated and it can be determined whether they are confused because of misleading or deceptive conduct on the part of the respondent.

118 By reference to that causative requirement, Stephen J identified a need, in the context of a claim of misleading or deceptive conduct based upon a similarity between the name utilised by the applicant and that of its rival, to consider the contribution made by the applicant’s adoption of a name consisting of descriptive words. In a well known and often cited passage, Stephen J said at 229:

There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name. Because it is descriptive it is equally applicable to any business of a like kind, its very descriptiveness ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business and hence its application to other like businesses will not ordinarily mislead the public. In cases of passing off, where it is the wrongful appropriation of the reputation of another or that of his goods that is in question, a plaintiff which uses descriptive words in its trade name will find that quite small differences in a competitor's trade name will render the latter immune from action: Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd (1946) 63 RPC 39, per Lord Simonds at 42. As his Lordship said (at 43), the possibility of blunders by members of the public will always be present when names consist of descriptive words: “So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be.” The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.