FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union v Visy Packaging Pty Ltd (No 3) [2013] FCA 525

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

The Court declares that:

1. In contravention of s 340(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) the First and Third Respondents took adverse action against Jonathan Zwart by instigating and conducting an investigation into his conduct on 5 August 2011, by suspending him from employment on 8 August 2011, and by issuing him with a final written warning on 18 August 2011, because he had exercised a workplace right.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application against the Second Respondent is dismissed.

2. On or before 7 June 2013 the parties consult and file with the Court minutes of proposed orders that address the filing and service of outlines of submission in relation to the Applicants’ claims for the imposition of penalties upon the Respondents.

3. The matter be listed for further hearing on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

FAIR WORK DIVISION | VID 867 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | AUTOMOTIVE, FOOD, METALS, ENGINEERING, PRINTING AND KINDRED INDUSTRIES UNION First Applicant JONATHAN PHILIP ZWART Second Applicant

|

AND: | VISY PACKAGING PTY LTD (ACN 095 313 723) First Respondent TONY SCOTT Second Respondent ROBIN STREET Third Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MURPHY J |

DATE: | 29 may 2013 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

1 In this proceeding the applicants, Jonathan Zwart and the Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union (“AMWU”) seek declarations and penalties against the respondents, Visy Packaging Pty Ltd (“Visy”) and two of its managers, claiming that they took adverse action against Mr Zwart under s 340 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (“the FW Act”).

2 Mr Zwart is employed by Visy as a fitter and machine setter at its Food Can plant in Coburg (“the factory”). He is a member and a delegate of the AMWU, and also the elected health and safety representative under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic) (“the OHS Act”) for the Auto Press Section (“APS”) in the factory. The second respondent, Tony Scott, is the Production Manager at the factory, and the third respondent, Robin Street, is Mr Scott’s superior as the Operations Manager.

3 At the base of the dispute is the fact that the noisy factory had forklifts with reversing warning beepers (“the beepers”) which either could not be heard or were barely audible. No doubt the difficulty in hearing the beepers was also related to the fact that all employees were required to wear hearing protection because of the noise. On the morning of 5 August 2011, following his being surprised by a reversing forklift with an inaudible beeper, Mr Zwart “tagged” one and later a second forklift. “Tagging” is an approved process at the factory involving the attachment of a tag to plant or equipment to indicate that it is not to be used and to alert others that it is faulty or unsafe.

4 Over about the next about five hours a number of meetings and discussions (“the meetings”) ensued between Mr Zwart, Mr Scott, Mr Street and other managers (later also including a WorkSafe Victoria inspector) aimed at resolving the issues regarding the tagged forklifts. While some of what occurred at the meetings is in dispute, it is clear that:

(a) Mr Scott and Mr Street took a different view from Mr Zwart as to what temporary measures should be put in place to enable the forklifts to be returned to service until the problem with the beepers had been addressed;

(b) Mr Scott and Mr Street took a dim view of Mr Zwart's attitude to resolving the issue regarding the tagged forklifts, later characterising it as a failure to “cooperate and engage in reasonable discussions about reasonable and practicable alternative control measures.”

(c) Mr Scott and Mr Street considered that Mr Zwart had not used appropriate dispute resolution procedures and had lied in the meeting with the WorkSafe inspector, firstly in saying that he had tagged the forklifts acting as a “concerned employee” rather than as a health and safety representative, and, secondly when he said that there had been prior “near misses” involving forklifts at the factory.

5 The forklifts were returned to service at the direction of the WorkSafe inspector just after lunchtime, and the audibility of the beepers was rectified before 3.30 pm that day. There was little lost production time.

6 Even so, Mr Street decided to conduct an investigation and to suspend Mr Zwart from work while that investigation was on foot. He said he was concerned about Mr Zwart’s unsatisfactory conduct in the meetings, particularly the alleged lack of cooperation by him.

7 Following an application by the AMWU to the Federal Court for interlocutory relief in relation to the investigation and suspension, a decision was made that the investigation should proceed but be undertaken by an independent investigator, Gregory Halse. He conducted an investigation and after receiving his report Mr Wiltshire, the General Manager of Visy’s Food Can Division, decided to give Mr Zwart a final written warning for his conduct (“the Final Written Warning”).

8 In my view the evidence is clear that the beepers were defective. It is clear too that Mr Zwart had a reasonable basis for tagging the forklifts and also for taking the stance that he did in the meetings with the managers and the WorkSafe inspector. The respondents did not contend that Mr Zwart was wrong to tag the forklifts or that he acted other than out of a genuine concern for safety in doing so.

9 I consider that the surrounding facts and circumstances indicate the implausibility of the respondents’ stated reasons for taking the actions that they did. The facts and circumstances point away from the conclusion that Mr Zwart’s conduct in the meetings is the reason for the adverse action. In fact, the evidence points to the likelihood that the respondents’ actions were taken because Mr Zwart tagged the forklifts and then resisted the temporary measures proposed to return the forklifts to service. As I detail below, I found the account of some of the respondents’ witnesses unreliable on some important issues. I prefer Mr Zwart’s account.

10 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that the applicants have established a contravention by the respondents of s 340(1) of the FW Act. In arriving at this conclusion I have decided that:

(a) the respondents’ actions in instigating and conducting the investigation, suspending Mr Zwart from work, and issuing the Final Written Warning constitute adverse action under s 342(1) of the FW Act;

(b) Mr Zwart’s rights or duties under the OHS Act, whether as a health and safety representative or an ordinary employee, are “workplace rights” within s 340 of the FW Act;

(c) Mr Zwart was exercising a workplace right under the FW Act when he tagged the forklifts because of his concern about the risk they posed to occupational health and safety and during the meetings when resisting the proposals to return the forklifts to service without fixing the beepers; and

(d) the respondents failed to discharge their onus of establishing that Mr Zwart’s exercise of workplace rights was not a substantial and operative factor in their decisions to instigate the investigation, suspend Mr Zwart from work, and issue the Final Written Warning.

The Facts

11 The trial involved detailed analysis, indeed over-analysis, of the otherwise ordinary events of 5 August 2011. Because of the parties’ attention to and reliance on the minutiae of the facts, I have set them out in detail. While many of the facts are uncontroversial, the chronology also records my view of the evidence in relation to those facts that are in dispute.

The relevant Visy employees

12 Mr Zwart is a long term employee at the factory having worked there for about 23 years, commencing in 1988 when it was owned by Southcorp. Visy took over its running in 2001.

13 On 5 August 2011 Mr Zwart was working as a fitter and machine setter in the APS. Since 2004 he had been the elected health and safety representative for the APS day shift which is a “designated work group” under the OHS Act and he has been an AMWU delegate since 2003. As the Production Manager, Mr Scott oversaw the manufacturing process and was the manager to whom Mr Zwart reported in the event of a safety incident. Mr Scott reported to the Operations Manager, Mr Street, who in turn reported to Rohan Wiltshire.

14 Chris Flanagan, who was the manager of the Material Preparation section of the factory, Earl Hayes, who was at the relevant time the Human Resources Manager for Visy’s Northern Operations, and his superior, Ian Harmer, who was the General Manager of Human Resources Operations, also played a role in the events.

15 Each of Mr Scott, Mr Street, Mr Wiltshire, Mr Hayes and Mr Harmer gave evidence for the respondents. The WorkSafe Inspector, Mr Renehan, and the investigator, Mr Halse, were not called. Mr Zwart gave evidence for the applicants.

The safety campaign at Visy

16 From about April 2011 Visy commenced a safety campaign entitled “Tuff on Safety”, aimed at improving safety at the factory. On 9 June 2011 Mr Wiltshire gave a presentation regarding workplace safety to the factory employees. The evidence establishes that Mr Wiltshire exhorted the employees to be more vigilant in addressing safety issues stating, among other things:

• “Challenge the ‘I've always done it this way’ mentality”;

• “Challenge the unsafe behaviour of the guys working next to you”;

• “You have the ability to stop the next injury from occurring”;

• “There is zero tolerance to unsafe practices and behaviour”; and

• “We are all responsible for safety and are expected to act and work in a safe manner and tell someone when we don't think it's safe”.

Importantly, the employees were instructed that there were “absolutely no excuses for ignoring unsafe practices” and that the factory was one of Visy's poorer performing sites.

Visy’s safety rules relevant to the beepers

17 Visy had various safety rules relevant to forklift warning beepers. These are set out in various forms, checklists and procedures and include:

(a) Visy's Standard Operation Procedure, which relevantly states that operators must ensure that forklifts have a reversing warning beeper, flashing light and horn. It prescribes in the following terms a procedure for tagging a forklift for safety reasons:

In the event of a forklift being considered unsafe to drive, the following will apply

a) Remove the ignition key and notify your forklift mechanic or Supervisor.

b) Complete the corrective action report and distribute to appropriate persons.

c) Obtain a “Danger” “Do not use” tag and place [on] the forklift in a prominent and secure position

*NOTE: forklift mechanic is the only person authorised to remove the tag

(b) The WorkSafe Operator’s Checklist sticker affixed to each forklift, which relevantly states that operators should check to ensure that warning devices including lights, horn and reversing beeper are operational prior to use. The checklist states that if faults with warning devices exist, the forklift should not be used;

(c) The operating screen of the computer fitted to each forklift requires that, prior to use, the operator confirm that the forklift’s lights, horn and reversing beeper are all functional; and

(d) The WorkSafe Forklift Safety Checklist which is a sticker identical to the WorkSafe Operators Checklist placed on a visible part of each forklift.

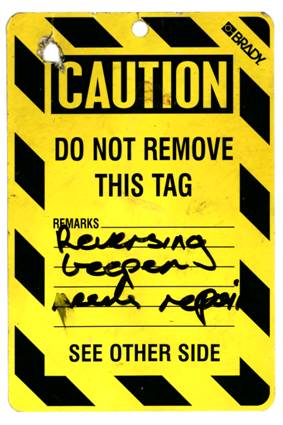

18 A copy of the “tag” used in the subject events is set out below.

19 Safe forklift practices are also prescribed in a WorkSafe publication entitled “A Handbook for Workplaces - Forklift Safety reducing the risk” which states, amongst other things, that “Audio warnings are just as important as visual ones. A mixture of high volume alarms and horns coupled with flashing lights best warn pedestrians of approaching forklifts.” Visy appears to have practices consistent with the recommendations in this publication.

20 It follows that Visy is correctly seen as recognising the importance of warning beepers among the suite of safety measures necessary to avoid the danger that forklifts present in a workplace.

Events on 5 August 2011 prior to 10 am

21 On 5 August 2011 Mr Zwart arrived at work for a shift that began at 7 am. He went about his duties, wearing hearing protection as required, taking samples from different machines and checking their quality. At about 8 am he began to cross an aisle way adjacent to the “E Unit” which was sometimes used by forklifts.

22 His evidence is that he was then surprised by a loaded forklift, being driven in reverse along the aisle-way by his supervisor Dennis Radic. He says that his view of the reversing forklift was obscured by plant and equipment and he did not initially see it and Mr Radic did not apparently see him. Importantly, he says that he did not hear its reversing beeper. This caused him to be concerned that the inaudibility of the beepers was a risk to occupational health and safety. He therefore completed a Hazard Report form, left it in Mr Scott’s office and returned to his usual duties.

23 Mr Zwart then says he became concerned that merely lodging the Hazard Report form did not go far enough in protecting health and safety, and that he may be liable under the OHS Act if he did not take further steps. Accordingly, when Mr Radic later returned with the forklift Mr Zwart approached him and asked him to put the forklift in reverse so as to test the warning beeper. He says that in performing this test he could not hear the beeper adequately over other factory noise. He then tagged it as unsafe. Mr Radic did not object to Mr Zwart tagging the forklift. Mr Zwart then resumed his usual duties.

24 Upon becoming aware of the Hazard Report and that a forklift had been tagged, Mr Scott advised his superior Mr Street. Mr Street told him to clarify with Adaptalift (the company from which Visy leased the forklift) the necessary standard for audibility of a forklift reversing beeper and to discuss the issue with Mr Zwart. Mr Scott says that he requested that an Adaptalift technician be sent to the factory, and then arranged to meet with Mr Zwart to discuss the issue.

The 10 am meeting

25 At 10 am Mr Zwart was called into the APS tea room for a meeting with Mr Scott and Mr Radic. Mr Scott asked Mr Zwart what had occurred and Mr Zwart told him that the forklift was unsafe because its warning beeper could not be heard. Mr Scott suggested to Mr Zwart that a forklift be obtained from another part of the factory, the Full Panel section, and brought to the APS.

26 However, the potential difficulty with this proposal was that some of the forklifts were of the same type, and had the same beepers. Mr Zwart does not dispute that he then said that if another forklift with a similar defect came into the APS he would also tag that forklift as unsafe. The respondents rely on this statement as indicating Mr Zwart’s uncooperative and obstructive attitude. As I later set out, I do not accept that it is appropriate to see it this way.

27 Mr Radic obtained a forklift from the Full Panel section and brought it to the APS. He positioned it near Press No. 9 to enable it to be tested. Mr Zwart’s evidence is that upon testing the warning beeper he could not hear it. Mr Scott does not agree that the beeper was inaudible, but he accepts that it was difficult to hear, particularly when one of the plant’s ordinary process sirens sounded. Mr Zwart tagged that forklift too and then again returned to his usual duties.

28 The evidence establishes that Mr Scott did not disagree at that time with Mr Zwart's assessment that the beeper was difficult to hear, and when Mr Zwart tagged this forklift he did not complain about that action being taken or suggest a different course.

The 10.20 am Meeting

29 Shortly after this Mr Scott rang Adaptalift. His evidence is that he was told that no Australian Standard existed in relation to the required decibel level of a forklift warning beeper. Mr Scott then paged Mr Zwart, Mr Radic and a manager from the Material Preparation Section, Mr Flanagan, to attend a further meeting at about 10.20 am. At this meeting Mr Zwart was informed that Adaptalift said that there was no Australian Standard in respect of the required volume of a forklift warning beeper.

30 Mr Scott proposed, as a temporary measure to enable the tagged forklifts to be returned to service, that forklift drivers should use the steering wheel horn as a warning device when reversing. Mr Zwart strongly rejected this proposal as unsatisfactory.

31 It is uncontentious that this proposal was the only temporary measure suggested by Mr Scott at this meeting, and that after rejecting it Mr Zwart made to leave the meeting. Mr Scott’s evidence is that Mr Zwart made little attempt to cooperate and sought to walk out of the meeting. However, on my view of the evidence, before Mr Zwart left the meeting, Mr Flanagan suggested that a different model forklift should be tested. Mr Zwart accepted this suggestion and went with Mr Flanagan to get such a forklift. It is not in dispute that upon testing the beeper on this forklift Mr Zwart was satisfied that it could be easily heard, and the forklift was put into operation in the APS. I infer from this course of events that Mr Zwart was not as uncooperative as the respondents allege.

32 The forklift cleared the developing backlog in a short time but was then required to be returned to the Material Preparation section. Mr Zwart says that it is common practice for forklifts from other sections to be used if the assigned forklift is not operational. This evidence was not challenged.

33 While Mr Zwart and Mr Flanagan were getting the third forklift, Mr Scott spoke with Mr Street. Mr Scott informed Mr Street that Mr Zwart did not seem interested in temporary measures to resolve the problem with the forklifts, that he had walked away from the 10.20 am meeting and that there had been some “machine down time” as a result of the tagged forklifts. Mr Scott concedes that he did not inform Mr Street that Mr Zwart had accepted Mr Flanagan’s suggestion to use the forklift from the Material Preparation section as a temporary measure.

34 The question as to whether there was any “machine down time” at this time is in dispute. Mr Zwart says there was not. Mr Scott testifies that there was, and says that he told Mr Street that there was. However Mr Street’s evidence is that production was still going, albeit slower than usual. I accept that production may have slowed but the evidence does not establish that it had stopped at this stage.

35 After talking to Mr Scott, Mr Street telephoned WorkSafe Victoria and requested that an inspector be sent to the factory to look at the forklifts and to provide advice. The inspector, Simon Renehan, arrived at about 11.30 am at which time he was briefed on the events of the morning by Mr Scott and Mr Street. Mr Renehan did not separately obtain Mr Zwart’s views. Mr Scott’s evidence is that Mr Renehan only obtained the version of events provided by Mr Street and Mr Scott.

The 12.05 pm meeting involving Mr Renehan

36 At approximately 12.05 pm Mr Zwart was called to the APS office where Mr Scott, Mr Street, Helen Tyler-Meers (Visy’s Health, Safety and Environment Co-ordinator) Mr Flanagan and Mr Renehan were waiting for him. Ms Tyler-Meers, Mr Flanagan and Mr Renehan were not called to give evidence, but there is agreement between Mr Scott, Mr Street and Mr Zwart as to much of what transpired.

37 Mr Renehan began by setting out his understanding of the events of the morning and then proceeded to question Mr Zwart about his status as a health and safety representative and the responsibilities that such a role entails. Mr Renehan advised that a forklift needed only a one warning device which could be either the steering wheel horn, the reversing beeper, the flashing lights, or the reversing lights and that there was no Australian Standard prescribing the decibel level of a forklift reversing beeper.

38 On a number of occasions Mr Renehan put to Mr Zwart that he had issued a “cease work” direction under the OHS Act, apparently on the basis that a cessation of work was the result of his tagging the forklifts. Mr Renehan asked Mr Zwart if he thought there was an imminent risk to safety in respect of the tagged forklifts and Mr Zwart said that he thought that there was. The evidence indicates that his questioning on this topic was insistent and carried the suggestion that Mr Zwart was wrong in issuing such a direction. Mr Zwart repeatedly denied this, saying that he had not told anybody to stop working. The respondents now concede that Mr Zwart did not direct a cessation of work under s 74 of the OHS Act. I accept that Mr Zwart did not issue such an order.

39 Mr Renehan asked Mr Zwart whether there had been other safety incidents at the factory involving forklifts. Mr Zwart says that he told Mr Renehan that there had been several. Both Mr Street and Mr Scott say that Mr Zwart referred to four earlier incidents and used the description “near misses”, which are incidents that are required to be reported to management as part of Visy’s safety system. They also say that he effectively represented that these incidents were recent. Mr Zwart denies using the expression “near misses” and denies making any statement as to when they had occurred. Insofar as the currency of the near misses is concerned, on my view of the evidence the respondents misunderstood Mr Zwart’s statement. Mr Zwart says and I accept that Mr Renehan was first to characterise the incidents as near misses, although it is likely that Mr Zwart picked up the use of that expression after Mr Renehan. Visy relies on this as an example of Mr Zwart “lying”. In my view the evidence does not establish that he did.

40 Not much turns on whether Mr Zwart referred to near misses or not. He agrees that he sought to indicate that there had been previous forklift safety incidents. Upon being informed of the earlier incidents Mr Renehan pressed the issue of whether or not Mr Zwart had reported these incidents as “near misses”. Mr Renehan then returned to questioning of why Mr Zwart had directed a cessation of work. Mr Zwart again denied that he had directed anyone to stop working.

41 At that point Mr Zwart asked for a break from the meeting to seek assistance from the AMWU because he says that the conversation had become technical and he felt uncomfortable. One can well understand why he felt that way. He was required to attend a meeting with four Visy managers and a WorkSafe Victoria inspector, alone and without support. He faced close questioning as to the operation of the OHS Act by an inspector who had been briefed by Visy’s managers but who had not spoken to him to obtain his version of events. The evidence indicates that he had become uncomfortable and disconcerted by the way the meeting was conducted, and was probably somewhat defensive as a result.

42 Mr Zwart telephoned Ian Thomas, an AMWU industrial officer who he says, and I accept, advised him to inform the meeting that he had tagged the forklifts acting as a “concerned employee” rather than as a health and safety representative. He says, in effect, that Mr Thomas told him that he should take this stance because in tagging the forklifts he had not issued a Provisional Improvement Notice under the OHS Act.

43 Mr Zwart returned to the meeting and, following the advice given by Mr Thomas, said that he had tagged the forklifts as a concerned employee. As it turns out, Mr Thomas’ advice was incorrect and Mr Zwart was wrong in following it. However, under both Visy's internal processes and the OHS Act it made no difference whether Mr Zwart tagged the forklifts as a health and safety representative or a concerned employee. It was conceded by Mr Street that the distinction was of no practical consequence. The respondents seek to rely upon this as an example of Mr Zwart lying. On my view of the evidence it is wrong to so characterise it.

44 Mr Renehan again returned to the suggestion that tagging the forklifts amounted to a direction to cease work. Mr Zwart says he denied this again. He again became uncomfortable with Mr Renehan’s line and method of questioning and decided that he needed to make a further phone call to the AMWU.

45 Upon returning from that telephone call he said that he was not going to answer any further questions without the assistance of an AMWU representative. He handed Mr Renehan a note with Mr Thomas’ telephone number. It was then about 1 pm and Mr Zwart had been at work since 7 am. He said that he was going to take his lunch break.

46 Mr Renehan took exception to Mr Zwart’s refusal to answer further questions but Mr Zwart maintained his position and soon after left the APS office and took his lunch break. During the lunch break he again telephoned the AMWU and an official named Georgie Kimmell agreed to be his support person at future discussions.

47 Following Mr Zwart’s departure, Mr Renehan was satisfied that the tagged forklifts could be returned to service and (pending Adaptalift’s attendance to look at the beepers) adopted the temporary measure earlier proposed by Mr Scott - which involved the reversing forklift operators being told to use the steering wheel horn. It appears that one forklift was returned to service over Mr Zwart’s lunch break. Immediately after lunch Mr Zwart was requested to remove a small padlock he had affixed to the other and it was returned to service too.

The conversation with Mr Renehan

48 Upon return from lunch Mr Zwart was asked by Mr Scott to come to the APS Office, where, at least, Mr Renehan, Mr Street and Mr Scott were still in attendance. However, on the basis that he needed AMWU assistance, Mr Zwart said that he was not prepared to be questioned further by Mr Renehan at that time.

49 Following this Mr Scott approached Mr Zwart and again requested that he speak with Mr Renehan. In order to deal with Mr Zwart's concerns about a lack of support, Mr Scott agreed that he could be supported by another employee in the discussion, which would occur without the management team present. Mr Zwart and Mr Renehan then spoke for about thirty minutes. Mr Zwart says that Mr Renehan apologised to him for his earlier approach and sought a “fresh start”.

The alterations to the forklifts

50 The evidence is that an Adaptalift serviceman arrived at the factory during the afternoon to look at the problem with the beepers. It is not clear on the evidence at what point the Adaptalift serviceman arrived, but it is uncontentious that the audibility of the beepers was speedily rectified.

51 At about 3.30 pm Mr Street told Mr Zwart that Adaptalift had altered the configuration of the beepers on the forklifts and the two men then tested them. It is common ground that the new configuration of the beepers significantly increased their audibility, and that Mr Zwart approved their operation. Shortly thereafter Mr Zwart’s shift finished and he left work for the day.

Events of Monday 8 August 2011

52 Mr Street says that late on Friday 5 August he spoke to the Northern Operations - Human Resources Manager, Mr Hayes, about the events of that day. While Mr Hayes says that the conversation took place on Monday 8 August, there is no disagreement between them about what was said. Both say that they discussed Mr Street’s concerns regarding Mr Zwart's conduct in the meetings on Friday.

53 The evidence is that Mr Street informed Mr Hayes of his concerns that Mr Zwart:

(a) had failed to cooperate with the Worksafe inspector;

(b) had made allegations about earlier near misses;

(c) had refused to cooperate in resolving the issue with the forklifts; and

(d) had altered his position from acting as a health and safety representative when tagging out the forklifts to acting as a “concerned employee”.

54 Mr Hayes’ evidence is that Mr Street thought that Mr Zwart's behaviour required investigation and that he wanted to suspend him and conduct an investigation. Both Mr Street and Mr Hayes say they then discussed the application of Visy’s “Performance Management Policy” (“the Policy”) to Mr Zwart. The Policy outlines Visy’s process for employee counselling and disciplinary action.

55 Under a heading “Formal Discipline Procedure” the Policy sets out a graduated series of steps to deal with employment related misconduct. As is common in many large organisations it provides for:

• First Warning (verbal warning);

• Second Warning (written warning);

• Third and Final Warning (written warning);

• Dismissal; and

• Summary Dismissal.

56 Under the heading “Summary Dismissal” the Policy provides:

Summary dismissal occurs where the employee is dismissed without notice being either given or paid and for situations of serious misconduct. It is rare to issue such a dismissal and the misconduct must be of such a nature that it would be unreasonable to require the manager to continue the employment during the notice period.

There are certain performance issues that cannot be tolerated. Whilst in every instance we will examine all the issues, an employee risks being dismissed without notice if they are:

intoxicated at the workplace (alcohol or drugs)

physically fighting at the workplace

serious harassment

using threatening behaviour

carrying out unsafe work practices

negligently or deliberately damaging the environment

displaying wilful or deliberate behaviour by an employee that is inconsistent with the continuation of the contract of employment

An employee can be summarily dismissed without any prior warnings having been given.

While the listed examples of misconduct that might justify summary dismissal cannot be seen as exhaustive, the Policy nevertheless shows, appropriately in my view, that Visy sees it as a remedy reserved for serious misconduct. In my opinion it is hard to see Mr Zwart’s conduct on 5 August as being in any way similar or analogous to the misconduct specified.

57 On the last page of the Policy, under the heading “Suspension with Pay”, it provides:

Suspension with pay may be utilised in a situation where there is an allegation of serious misconduct against an employee and the manager does not wish the employee to be on the premises while investigations are made. Suspension on pay should only take place if the matter is so serious that it may warrant dismissal.

Managers should ensure that the investigation is handled promptly to resolve the matter as soon as possible.

It seems clear that the reference to a matter which is so serious as to justify dismissal is a reference to summary dismissal. The Policy otherwise only envisages dismissal for misconduct after a graduated series of warnings. The suspension letter given to Mr Zwart on 9 August referred to the possibility of summary dismissal, which is consistent with Mr Street’s evidence.

58 Mr Hayes says that he told Mr Street that he was able to suspend Mr Zwart but only if Mr Zwart continued to be paid for the duration of the suspension. Mr Street asked Mr Hayes to draft a letter of suspension for the purposes of an investigation. Mr Hayes advised that Mr Scott should inform Mr Zwart of the decision and the general reasons for it. In asking Mr Scott to communicate his decision, Mr Street says that he told Mr Scott to say that his concerns included “a lack of trust and confidence” in Mr Zwart in relation to Mr Zwart’s behaviour and professionalism in the meetings on 5 August and his decision to refer to himself as a “concerned employee” rather than as a health and safety representative.

The Suspension

59 Mr Scott then met with Mr Zwart and informed him of the decision to suspend him on pay while an investigation was undertaken, and of Mr Street’s stated concerns. Mr Scott told him that the allegations were of a failure to follow appropriate process in relation to tagging the forklifts; a similar failure to cooperate with the WorkSafe inspector; a failure to report near misses; and a breakdown in trust and confidence. As I explain later, I do not accept that Mr Street’s reasons were so limited. The evidence indicates that his reasons included that he believed Mr Zwart was not acting out of a genuine concern for health and safety when he tagged the forklifts, and was instead motivated to deliberately disrupt production. I do not accept Mr Street’s evidence to the contrary in this regard.

60 Mr Wiltshire, the divisional manager, returned from holidays on this day. He met with Mr Street and Mr Hayes and was informed of the events involving Mr Zwart. While his evidence is that he did not engage with the processes or issues at that time he says that he requested to be kept informed of developments.

61 Notwithstanding that he had been told he was suspended, Mr Zwart attended work as usual on the morning of 9 August 2011. Early in his shift Mr Scott and Mr Flanagan approached him and asked him to leave the site as per the instruction given the previous day. The evidence is that Mr Zwart’s attendance at work was based on his view that the dispute resolution procedures agreed between Visy and the AMWU meant that the status quo was to prevail whenever an industrial dispute was notified to the Fair Work Commission. He informed Mr Scott that the issue of his suspension was being disputed and that he was therefore not required to leave the factory. Mr Flanagan suggested that he wait in the APS tea room until the impasse was resolved and he did so.

62 In my view, it was wrong of Mr Zwart to refuse to leave the workplace when instructed to do so. However, there is no complaint before me in relation to Mr Zwart's behaviour in that regard and Visy does not rely upon it.

63 Mr Scott then spoke to Mr Street and told him that Mr Zwart was in the tea room despite being instructed to leave the site. Both men went to the tea room and Mr Street gave him a letter of suspension drafted by Mr Hayes. Relevantly, the letter provided:

Further to our discussion today, I confirm that you are suspended on pay pending further investigation of allegations under Visy’s Performance Management Policy in relation to the tagging out of 2 forklifts by you on 5th August 2011.

The following matters are alleged against you arising out of those events:

• failure to use appropriate dispute resolution procedures

• lying, and

• breach of trust and confidence.

Please note that these allegations are serious and if proven may warrant summary dismissal.

Mr Zwart left the factory and was then suspended on pay from 9 August 2011 until 23 August 2011.

64 At some point on 9 August Mr Wiltshire asked Mr Hayes to provide a summary of the events, which Mr Hayes emailed to Mr Wiltshire at 11.49 pm that evening. Without descending to the minutiae of his summary, in my view it was one-sided.

The Interlocutory Hearing

65 On the afternoon of 9 August 2011 Mr Zwart and the AMWU brought an application for an interlocutory injunction in this Court seeking to halt the investigation and suspension. Dodds-Streeton J refused the application, in part because of an undertaking by Visy not to proceed with giving effect to any disciplinary action until after the resolution of any application that arose from the outcome of the investigation: Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union v Visy Packaging Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 953.

66 Following her Honour’s decision, Mr Harmer spoke to Mr Wiltshire and it was decided that the investigation should be carried out by someone independent and external to the company. Mr Harmer’s evidence is that he was afraid that permitting Mr Street or Mr Scott, or others similarly proximate to the events of 5 August, to conduct the investigation “might not be conducive towards getting a clear understanding of the facts.” Mr Wiltshire’s evidence is that he agreed with Mr Harmer’s concerns and an external investigator, Greg Halse, was hired by Mr Harmer to conduct the investigation.

The Investigation

67 Mr Halse was not called by Visy to give evidence, although various emails recording instructions given to him are in evidence, as is his report. He was instructed to interview the persons involved in the events of 5 August 2011, and prepare a report as to those events. While initially he was requested to provide recommendations as to the appropriate disciplinary outcome, if any, he was later instructed by Mr Harmer not to provide any such recommendation.

68 On 16 August 2011 Mr Halse conducted interviews of Mr Zwart, Mr Street, Mr Scott, Ms Tyler-Meers, Mr Radic and Mr Flanagan, being all those present during the relevant events, except for Mr Renehan. Although the investigation was described by both Mr Wiltshire and Mr Harmer as independent, as I set out later, I am not satisfied that it was.

Mr Halse prepared a report, the first version of which was delivered to Visy on the afternoon of 17 August 2010. Following some interventions by Visy, Mr Halse delivered the second version of the report to Mr Wiltshire at 8.30 am on 18 August 2011. The report provided in summary that Mr Zwart:

• caused a cessation of work when other control mechanisms were available and in place;

• failed to co-operate and engage in reasonable discussions;

• failed to co-operate with Worksafe once cessation had occurred;

• described near misses to give the impression that they were relevant (recent) and then changed his position to protect himself;

• hindered effective management through the way in which he collaborated and communicated; and

• initially acted as a health and safety representative and then altered his status to a “concerned employee”.

The Final Written Warning

69 Mr Wiltshire’s evidence is that he chose to read only the first 8 pages of Mr Halse’s 28 page report which contained his findings, and that he deliberately did not read the balance of the report including the interview summaries. He says that he wanted to avoid reaching his own conclusions as to what happened on 5 August as that was the task of the independent investigator, Mr Halse. He says that he wanted to preserve his role as decision maker only.

70 Mr Wiltshire made the decision in relation to the issue of the Final Written Warning. He says that after reading, and relying on, only the first part of the report he decided that the matter of Mr Zwart’s conduct needed to be taken further. I do not accept that Mr Wiltshire was only influenced by the first eight pages of the Halse report, as he had many other sources of information within Visy. I also do not accept his evidence that he was as quarantined from the fact finding process as he says. For example, he had various conversations about the events with Mr Street and Mr Harmer, he received the email from Mr Hayes referred to above, and also a copy of an affidavit of Mr Scott from the interlocutory hearing which set out his version in detail.

71 The evidence of both Mr Wiltshire and Mr Harmer is that they discussed the various disciplinary measures that might be taken in the circumstances. Mr Wiltshire also discussed with Mr Street, and another plant manager in Wodonga, their approach to similar issues in the past.

72 After concluding these discussions Mr Wiltshire says that he made the decision to issue the Final Written Warning to Mr Zwart. Both Mr Harmer and Mr Wiltshire say that the Final Written Warning was drafted by Mr Harmer at Mr Wiltshire’s request, and then signed by Mr Wiltshire and delivered to Mr Zwart on 18 August 2011.

73 The Final Written Warning reads as follows:

Dear Jon

This letter is a final written warning in relation to your conduct.

As a result of the recent investigation into your conduct, Visy has determined that by your actions on 5 August 2011, you have engaged in the following misconduct:

• you failed to follow the appropriate OHS/Dispute resolution procedure insofar as you:

o caused a cessation of work when other control mechanisms were available and in place;

o failed to co-operate and engage in reasonable discussions to resolve the issue;

o failed to co-operate with WorkSafe once the cessation had occurred;

• misrepresented your position:

o by initially declaring that you were acting as an OHS representative and then altering your reasoning to say that you had the status of a “concerned employee” only; and

o described near misses to give the impression that they were relevant (recent) and then changed that position to protect yourself; and

• thereby caused a loss of trust and confidence in relation to the way that you hindered the effective management of the issue through the way in which you collaborated and communicated.

This conduct constitutes serious misconduct. In the context of your prior warning for failure to follow Site Procedure, such serious misconduct could warrant summary dismissal and we have considered a dismissal outcome. However, in circumstances of your long length of service, the potential harshness of this outcome on you in terms of your personal and family circumstances and Visy’s desire to give you one final opportunity to demonstrate that its trust and confidence in you can be restored, I have preferred an outcome of a final written warning.

In this regard, this is your final opportunity and you are directed to ensure that in future:

• you comply with all dispute resolution procedures;

• you co-operate reasonably and appropriately with management in the resolution of those disputes;

• you co-operate with any external or internal investigating authority;

• you act openly and honestly at all times;

• you report all genuine near misses on the appropriate Hazard/Near Miss form; and

• you act consistently with the letter and spirit of Visy’s Values in demonstrating that Visy can be assured that it can have the requisite trust and confidence in you as an employee.

While Visy will seek to give you an opportunity to improve your conduct, further instances of misconduct will not be tolerated and may result in further disciplinary action up to or including the termination of your employment. This warning will be placed on your personnel file and I urge you to comply with the above directions at all times while at work and regard them as part of your usual duties and responsibilities. Finally, your suspension will end on Monday, 22 August 2011 and as such you are directed to return to work as normal from the start of your first usual rostered shift on and from Tuesday, 23 August 2011.

the LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

The Fair Work Act 2009

74 Since the beginning of last century, Commonwealth laws have sought to provide a measure of protection to union officers and members by prohibiting employers from injuring them for reasons that are related to union office, membership or activities and the rights derived from such office, membership or activities. Part 3-1 of the FW Act, under the heading “General Protections”, contains the most recent incantation of these statutory protections and prohibits, what is often described as, adverse action for a prohibited reason.

75 The objects of Pt 3-1 of the FW Act are set out in s 336 and include “to protect workplace rights”.

76 The AMWU and Mr Zwart allege that Mr Scott, Mr Street and Visy contravened Section 340(1) of the FW Act. That section relevantly provides:

A person must not take adverse action against another person:

(a) because the other person:

(i) has a workplace right; or

(ii) has, or has not, exercised a workplace right; or

(iii) proposes or proposes not to, or has at any time proposed or proposed not to, exercise a workplace right; or

(b) to prevent the exercise of a workplace right by the other person.

77 A “workplace right” is relevantly defined in s 341(1) as follows:

A person has a workplace right if the person:

(a) is entitled to the benefit of, or has a role or responsibility under, a workplace law, workplace instrument or order made by an industrial body;…

78 It is uncontroversial that the OHS Act is a workplace law as described in s 341(1) of the FW Act. This is so because s 12(d) defines “workplace law” to include:

any other law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory that regulates the relationships between employers and employees (including by dealing with occupational health and safety matters).

It is common ground that Mr Zwart had the role and responsibilities of a health and safety representative under the OHS Act and that the OHS Act gives rise to relevant “workplace rights”.

79 Section 342(1) contains a table defining the circumstances in which a person is treated as having taken adverse action against another person for the purposes of s 340(1). The adverse action relied on by the applicants is of the type defined in item 1(b) and (c) of the table which relevantly provides that adverse action includes action by an employer against an employee, if the employer:

…

(b) injures the employee in his or her employment; or

(c) alters the position of the employee to the employee’s prejudice;

…

80 Sections 360 and 361 are also important to the operation of Pt 3-1. They relevantly provide:

360 Multiple reasons for action

For the purposes of this Part, a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason.

361 Reason for action to be presumed unless proved otherwise

If:

(a) in an application in relation to a contravention of this Part, it is alleged that a person took, or is taking, action for a particular reason or with a particular intent; and

(b) taking that action for that reason or with that intent would constitute a contravention of this Part;

it is presumed, in proceedings arising from the application, that the action was, or is being, taken for that reason or with that intent, unless the person proves otherwise.

The applicants claim that the respondents took adverse action against Mr Zwart for reasons that include that he had exercised a workplace right. The applicants therefore have the benefit of the presumption in s 361.

81 The effect of s 539(1) and (2) of the FW Act is that s 340(1) is a civil remedy provision, the AMWU and Mr Zwart have standing to apply for orders in relation to a contravention of s 340(1), and this Court has jurisdiction to deal with such an application.

The Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic)

82 The OHS Act regulates the relationship between employers and employees in relation to workplace safety, providing that both employers and employees have a responsibility to provide a safe place of work: ss 21 and 25 of the OHS Act.

83 Section 25 provides that:

(1) While at work, an employee must—

(a) take reasonable care for his or her own health and safety; and

(b) take reasonable care for the health and safety of persons who may be affected by the employee's acts or omissions at a workplace; and

(c) co-operate with his or her employer with respect to any action taken by the employer to comply with a requirement imposed by or under this Act or the regulations.

Penalty: 1800 penalty units.

(2) While at work, an employee must not intentionally or recklessly interfere with or misuse anything provided at the workplace in the interests of health, safety or welfare.

Penalty: 1800 penalty units.

(3) In determining for the purposes of subsection (1)(a) or (b) whether an employee failed to take reasonable care, regard must be had to what the employee knew about the relevant circumstances.

(4) An offence against subsection (1) or (2) is an indictable offence.

84 Part 7 of the OHS Act provides for the representation of employees by the establishment of “designated work groups” (s 43) and through the election of health and safety representatives.

85 Division 5 of Pt 7 sets out the powers of health and safety representatives and includes s 58(1) which relevantly provides:

A health and safety representative for a designated work group may do any of the following—

(a) inspect any part of a workplace at which a member of the designated work group works—

(i) at any time after giving reasonable notice to the employer concerned or its representative; and

(ii) immediately in the event of an incident or any situation involving an immediate risk to the health or safety of any person;

…

86 Section 73 provides that if a health and safety issue arises at a workplace the employer, the employees, and any health and safety representative must attempt to resolve the issue. Sections 35 and 36 provide that an employer is required to consult with employees and with health and safety representatives and provide the employees and representatives with a reasonable opportunity to express their views. Sections 35 and 36 relevantly state:

35. Duty of employers to consult with employees

(1) When doing any of the following things, an employer must so far as is reasonably practicable consult in accordance with this Part with the employees of the employer who are or are likely to be directly affected by the employer doing that thing—

(a) identifying or assessing hazards or risks to health or safety at a workplace under the employer's management and control or arising from the conduct of the undertaking of the employer;

(b) making decisions about the measures to be taken to control risks to health or safety at a workplace under the employer's management and control or arising from the conduct of the undertaking of the employer;

…

(d) making decisions about the procedures for any of the following-

(i) resolving health or safety issues at a workplace under the employer's management and control or arising from the conduct of the undertaking of the employer

…

(f) proposing changes, that may affect the health or safety of employees of the employer, to any of the following-

(i) a workplace under the employer's management and control;

(ii) the plant, substances or other things used at such a workplace;

(iii) the conduct of the work performed at such a workplace;

…

36. How employees are to be consulted

(1) An employer who is required to consult with employees must do so by-

(a) sharing with the employees information about the matter on which the employer is required to consult; and

(b) giving the employees a reasonable opportunity to express their views about the matter; and

(c) taking into account those views.

(2) If the employees are represented by a health and safety representative, the consultation must involve that representative (with or without the involvement of the employees directly).

87 The OHS Act also provides that a health and safety representative may direct work to cease. Section 74(1) sets out this power in the following terms:

If -

(a) an issue concerning health or safety arises at a workplace or from the conduct of the undertaking of an employer; and

(b) the issue concerns work which involves an immediate threat to the health or safety of any person; and

(c) given the nature of the threat and degree of risk, it is not appropriate to adopt the processes set out in section 73-

the employer or the health and safety representative for the designated work group in relation to which the issue has arisen may, after consultation between them, direct that the work is to cease.

Initially it appeared that the respondents suggested that in tagging the forklifts Mr Zwart directed that work cease. This was also the thrust of Mr Renehan’s questioning. The applicants deny that he did so, but point to s 74 as the source of power to direct a cessation of work if the Court finds that he did. The respondents ultimately accepted that Mr Zwart had not directed a cessation of work under s 74 and the issue does not need to be considered further.

consideration

88 In summary, the effect of the various legislative provisions is that the respondents were prohibited from taking action against Mr Zwart which injured him in his employment or prejudicially altered his position because he exercised a workplace right. In summary, the respondents:

(a) deny that they took adverse action against Mr Zwart in investigating or suspending him or in issuing the Final Written Warning;

(b) while not disputing that the OHS Act creates workplaces rights, deny that Mr Zwart was exercising them at the relevant times; and

(c) deny that any part of the reasons for the actions they took included the reason that Mr Zwart had exercised a workplace right.

89 I consider that three central questions arise in the proceeding:

(a) Is the action complained of by the applicants “adverse action” for the purposes of the FW Act?

(b) Was Mr Zwart exercising a “workplace right”, under the FW Act at the relevant times?

(c) Was the adverse action complained of taken by the respondents because Mr Zwart had exercised a workplace right?

On the final question the respondents have the onus of establishing, on the balance of probabilities, that the substantial and operative factors for the adverse action did not include Mr Zwart’s exercise of a workplace right.

Issue 1: Is the action complained of by the applicants “adverse action” for the purposes of the Fair Work Act?

90 The applicants allege that:

(a) the investigation into Mr Zwart’s conduct on 5 August 2011 was adverse action within the meaning of s 342(1) items 1(b) and/or (c) of the FW Act in that Mr Zwart was wrongly exposed to a disciplinary process in his employment;

(b) the suspension of Mr Zwart was adverse action within the meaning of s 342(1) items 1(b) and/or (c) of the FW Act in that Mr Zwart was prevented from performing his work in his employment; and

(c) the Final Written Warning given to Mr Zwart was adverse action within the meaning of s 342(1) items 1(b) and/or (c) of the FW Act in that Mr Zwart’s continuing employment was made less secure.

The respondents deny that the investigation, the suspension or the Final Written Warning constitute adverse action.

91 In Patrick Stevedores No 2 Pty Ltd and Others v Maritime Union of Australia and Others (1998) 195 CLR 1 at [4] (“Patrick v MUA”) (in dealing with 298K of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) which is the predecessor to s 342 of the FW Act) the majority comprising Brennan CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ described these two categories of adverse action as follows:

par (b) covers injury of any compensable kind; par (c) is a broad additional category which covers not only legal injury but any adverse affection of, or deterioration in, the advantages enjoyed by the employee before the conduct in question.

Their Honours considered the reorganisation of Patricks Stevedores in that case as an action that fell within s 298K(1)(c) because the result of the action was that the “the security of the employer companies' businesses was made extremely tenuous. The security of the employees' employment was consequentially altered to their prejudice”: Patrick v MUA at [7].

92 This description of adverse action was adopted by the Full Court of this Court in Community and Public Sector Union and Another v Telstra Corporation Limited (2001) 107 FCR 93 at [17] (“CPSU v Telstra”) per Black CJ, Ryan and Merkel JJ. Their Honours found at [20] that, for the purpose of redundancy eligibility, the addition of detrimental criterion to the criterion already provided by the relevant industrial agreements meant that:

… the employment of employees on awards or certified agreements had become less secure, in a real and substantial manner, than it had been previously.

In those circumstances the Full Court determined that the position of the relevant employees had been altered to their prejudice within the meaning of s 298K(1)(c) and constituted adverse action.

93 In Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union v Belandra Pty Ltd (2003) 126 IR 165 at [70] North J observed, and I respectfully agree, that:

It is now established that a prejudicial alteration to the position of an employee may occur without any change in the employees’ legal rights.

94 It is common ground that it is unnecessary for the applicants to satisfy both items 1(b) or (c) of s 342(1) of the FW Act in order to establish that action by an employer against an employee constitutes adverse action. It is convenient to address the question of adverse action primarily by reference to the broader scope of s 342(1) item 1(c).

Is the investigation “adverse action”?

95 The applicants contend that the investigation into Mr Zwart’s conduct on 5 August 2011 injured him in his employment or caused a deterioration in his employment position.

96 The respondents argue that the applicants are wrong in their allegation that the investigation wrongly exposed Mr Zwart to a disciplinary process in his employment. They say that the fact that disciplinary actions were referred to as a possible outcome of the investigation does not convert a fact-finding investigation into a disciplinary process. They argue that the evidence shows that the investigation was a fact finding rather than a disciplinary process, and therefore not adverse action. The respondents also contend that the pleading operates to limit the applicants’ claim to one that the investigation is “wrongful”. They contend that the investigation is not “wrongful” as it cannot be said that there was no possible warrant for Visy wanting to investigate Mr Zwart’s conduct.

97 The respondents’ argument largely boils down to the proposition that when an employer conducts, in good faith, a fact finding investigation into allegations of employment related misconduct, that action cannot constitute adverse action. However, contrary to this submission, the authorities indicate that a properly conducted investigation brought in good faith may nevertheless give rise to a deterioration in the employment advantages enjoyed by the employee, thereby constituting adverse action.

98 In CPSU v Telstra at [17]-[18] the Full Court said:

[17] The question is whether, by sending the e-mail to its recipients, Telstra had altered the position of any of its employees to the employee's prejudice within the meaning of s 298K(l)(C). In Patrick Stevedores at 18 the majority of the High Court held that the subsection covers “not only legal injury but any adverse affection of, or deterioration in, the advantages enjoyed by the employee before the conduct in question”. The majority also observed (at 20) that the reorganisation of companies within the Patrick Group resulted in the security of the employer companies' businesses being “extremely tenuous” with the “security of the employees' employment [being] consequentially altered to their prejudice”. The reorganisation did not directly affect or alter any legal rights or obligations of the employees but it left their future employment less secure. Although this issue was not in dispute, the majority appears to have had no difficulty in accepting reduced security of future employment as falling within s 298K(l)(C) because it brought about an adverse affection of, or a deterioration in, the advantages enjoyed by the employees before the reorganisation.

[18] Where the alteration of position is alleged to be indirect or consequential, as in Patrick Stevedores and in the present case, a difficult question may arise as to whether a prejudicial alteration of position has in fact occurred. Answering that question may involve questions of degree. It is sufficient for present purposes to say that if the prejudicial alteration is real and substantial, rather than merely possible or hypothetical, it will answer the description in s 298K(l)(C).

(Emphasis added.)

99 In United Firefighters’ Union of Australia and Others v Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board and Others (2003) 198 ALR 466, Goldberg J dealt with an application for an interlocutory injunction against the hearing and presenting of employment related disciplinary charges. At [89] just prior to referring with approval to the passage in CPSU v Telstra cited above, his Honour held:

I am satisfied that there is a serious question to be tried on this integer of a contravention of s 298K. The laying of the charges imposes a burden on the persons charged to respond to allegations relating to their conduct as employees of the board. I do not consider that one can separate out the effect and consequence of the charges from the fact that they occurred because of the employee's employment by the board. I do not accept that a person charged is not affected in his or her employment until the charge has been proven. The expressions found in s 298K(1)(b) and (c) encompass a wide range of conduct both direct and indirect. The laying of the charges exposes an employee of the board to a potential disadvantage in his or her employment if the charges are ultimately proven.

100 I note too that in Kimpton v Minister for Education of Victoria (1996) 65 IR 317 at 319, North J refused to dismiss an application in which it was contended, amongst other things, that a requirement to respond to a written question in the course of an investigation into the applicants’ activities in the course of their employment constituted injury in their employment. North J observed that he did “not regard it as hopeless or untenable to contend that the requirement to participate in the investigatory process may amount to a relevant injury or prejudicial alteration.”

101 Collier J referred to these authorities in Jones v Queensland Tertiary Admissions Centre Ltd (No 2) (2010) 186 FCR 22 (“Jones v QTAC”), concluding that the investigation in that case was “adverse action”, although accepting the employer’s evidence that it was not for a prohibited reason. Collier J observed at [80]:

It follows that, on these authorities, commencement of an investigation by an employer into conduct of an employee can in certain circumstances constitute adverse action against that employee for the purposes of s 342, either as injury or alteration of the position of the employee.

At [82] her Honour continued, stating:

While an investigation into allegations of bullying may be appropriate and indeed warranted in the circumstances of an individual case, this does not mean that the employee will not be “injured” or their position altered to their prejudice by the investigation. I do not agree that, as a general proposition, amenability to a disciplinary investigation is a “normal” incident of employment, even if the investigation is commenced in good faith and on a proper prima facie evidentiary basis.

102 Collier J referred to, but did not follow, Ryan J in Police Federation of Australia and Another v Nixon and Another (2008) 168 FCR 340 (“Police Federation v Nixon”). In that case his Honour said at [48]:

I consider, with respect, that amenability to a disciplinary charge brought in good faith and on a proper prima facie evidentiary basis is a normal incident of employment and does not of itself, before the laying of the charge, constitute “an adverse affection of, or deterioration in, the advantages enjoyed by the employee” in the sense used by the High Court in the passage from Patrick Stevedores 195 CLR 1…

103 I respectfully agree with the views of Collier J. With great respect to the approach taken by Ryan J, in my opinion an investigation brought in good faith and carried out properly may nevertheless constitute adverse action. It must be accepted that an investigation which threatens the possibility of dismissal (as in the present case) will operate to reduce the security of future employment of the employee concerned. If it does so, CPSU v Telstra at [17]-[18] is authority for the proposition that it constitutes adverse action.

104 However, it should not be thought that this means that an employer that brings and carries out an investigation properly and in good faith may be seen to have acted unlawfully. Plainly this is not so. Employers must be able to properly investigate concerns regarding employment related misconduct. If unable to do so they may be forced to take disciplinary action on the basis of flawed or incomplete information, allow misconduct to go unpunished, or even allow it to continue. It is important to remember that while an investigation may constitute adverse action, it is only unlawful if the investigation is carried out for a prohibited reason. An employer has not acted unlawfully where the reason for the investigation is other than a prohibited reason. In fact, this was the result in Jones v QTAC.

105 I am satisfied that the investigation in the present case exposed Mr Zwart to a reduction in the security of his future employment which represented a deterioration in the advantages of his employment. It constitutes adverse action.

106 Although it is unnecessary to decide in this context, as I later explain, I am not satisfied on the evidence that the investigation in the present case was independent and impartial. This confirms my view that the investigation constitutes adverse action.

Is the suspension “adverse action”?

107 In determining whether or not the suspension constitutes adverse action the Court must determine whether the suspension had any impact or effect on Mr Zwart which injured him in his employment or altered his position to his prejudice.

108 The applicants argue that the suspension falls within s 342(1) item 1(c) because it is an “adverse affection of, or deterioration in the advantages enjoyed by the employee”, as explained in Patrick v MUA. However, the respondents contend that no direct evidence was adduced as to the actual effect on Mr Zwart of his suspension and that a finding that Mr Zwart had his position altered to his prejudice could only be made on the basis of an inference or assumption about the impact of the suspension, which could easily have been dealt with in the evidence. They contend that having regard to the nature of the proceedings such an inference should not be drawn.

109 In support of this argument they point to the decision of Handley JA in Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom Pty Ltd and Another (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 where his Honour at 418 explained that the well known rule expounded in Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 applied to examination in chief as it did to cross-examination.

110 Contrary to the respondents’ contention, I respectfully agree with the observations of Ryan J in Police Federation v Nixon. His Honour observed that the term “alteration” for the purpose of adverse action (then found in s 792(1)(c) of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth)) required “substantive change, and that “suspension from duties” constituted such substantive change.

111 Secondly, in the circumstances of this case I can see no reason why I should not infer that there was some deterioration in the advantages enjoyed by Mr Zwart in his employment. That Mr Zwart saw the suspension as causing such a deterioration is plain from his initial refusal to accept it, and his attempt to continue at work despite the advice that he was suspended. That Visy too saw suspension as a measure likely to adversely affect Mr Zwart may be inferred from the fact that in the Policy (set out at [55]-[57] above) suspension was only to be utilised in cases of serious misconduct warranting consideration of summary dismissal.

112 The consideration of whether an action constitutes adverse action should not be limited to an investigation only of how the action affects an individual. To say otherwise would mean that a finding that action by an employer against an employee constitutes adverse action is dependent, for example, on the mental and emotional fortitude of the relevant employee. There is, of course, a place for evidence as to the effects of the action on an employee when determining whether that action constitutes adverse action, but I do not accept that, in the absence of such evidence, the Court cannot reach its conclusion by inference from other evidence.

113 The evidence is that Mr Zwart was required to leave his employment from 9 August until 23 August 2011 and, during that time, he was required to keep all the circumstances of the matter confidential, specifically in relation to discussions with work colleagues. On 8 August he was told of his suspension, and initially refused to accept it. On 9 August he was then provided with a letter of suspension which advised that he was at risk of summary dismissal. He accepted this advice. The suspension meant that he could no longer talk to, mingle with and enjoy the camaraderie of his workmates at work or obtain the satisfaction that work tends to bring.

114 In my view the removal of an employee from their employment against his or her will, even temporarily, will usually be adverse to their interests. To say otherwise would be to deny the benefit one gains from the successful pursuit of activity in a field of expertise. The observation that active employment is a source of more than simply financial benefit is neither new, nor should it be considered controversial: see Squires v Flight Stewards Association of Australia (1982) 2 IR 155 at 164 per Ellicott J; Blackadder v Ramsey Butchering Services Pty Ltd (2005) 221 CLR 539 at [32] per Kirby J, and Callinan and Heydon JJ at [80]; Quinn v Overland [2010] FCA 799 at [101]-[103] per Bromberg J.

115 I consider that the suspension resulted in a deterioration in the advantages otherwise enjoyed by Mr Zwart in his employment and constitutes adverse action.

Is the Final Written Warning “adverse action”?

116 The applicants contend that the Final Written Warning had the effect of making Mr Zwart’s continuing employment less secure and therefore constitutes adverse action. The respondents argue against this, relying on Blair v Australian Motor Industries Ltd (1982) 3 IR 176 (“Blair”) where Evatt J rejected a submission that a warning was adverse action because it took the employee “one step closer to possible dismissal in the future”. His Honour held at 180:

Whatever may be the meaning of the phrases ‘injure him in his employment or alter his position to his prejudice’… I am clearly of the view that a mere warning given in the circumstances referred to does not so injure or alter an employee’s position to his prejudice.”

117 I doubt that Blair is good authority since the High Court dealt with this issue in Patrick v MUA. The majority accepted that reduced security of employment fell within s 298K(1)(c) of the Workplace Relations Act, because it brought about an adverse affection of, or a deterioration, in the advantages enjoyed by an employee. The Full Court also took this view in CPSU v Telstra.

118 I respectfully agree with the observations of Branson J in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Coal and Allied Operations Pty Ltd (1999) 140 IR 131 at [95] (“Coal and Allied Operations”). Her Honour said:

I accept the contention of the applicant that the issuing to an employee of a “written warning” of a “serious or major breach” within the meaning of the document “Disciplinary Procedure” has the effect of making the employee’s continuing employment less secure. Conduct engaged in by an employee who has received such a warning could lead to the termination of his or her employment although the same conduct engaged in by an employee who had not received a warning would not lead to the termination of that employee’s employment. In a sense, written warnings under the respondent’s disciplinary procedures may be regarded as analogous to the receipt of driving demerit points. It seems to me that few holders of driving licences would doubt that the advantage enjoyed by them in holding driving licences is adversely affected by the accumulation of demerit points close to, but less than, the number required to trigger cancellation of their licences.

I find that by issuing a written warning of a serious or major breach, as the case may be, to one of its employees, the respondent altered the position of that employee to the employee’s prejudice within the meaning of s 298K(1) of the Act.

Coal and Allied Operations has been cited with approval in Jones v QTAC at [100] and Finance Sector Union of Australia v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2002) 120 FCR 107 at [139].

119 The Final Written Warning stated that Mr Zwart was given a “final opportunity” apparently in lieu of summary termination, advised that his conduct could have warranted summary dismissal and noted that Visy had considered dismissing him. He was warned that one more misstep would lead to termination of his employment. To my mind, there can be no doubt that the security of his future employment was therefore reduced. In fact, that is one of the main points of the warning. I consider that the issuing of the Final Written Warning to Mr Zwart constitutes adverse action.

Issue 2: was MR ZWART exercising a “workplace right” at the relevant time?

120 Sections 25 and 58 of the OHS Act give rise to workplace rights under s 340(1) of the FW Act. The roles and responsibilities of a health and safety representative may involve the exercise of workplace rights. However, the respondents deny that Mr Zwart was exercising a workplace right at the relevant times.

The pleading issue

121 In closing submissions a complaint emerged in relation to Amended Statement of Claim and the way the applicants put their case in closing. The respondents argue that the pleading sets out each instance upon which the applicants say Mr Zwart exercised a workplace right. They contend that few of the instances pleaded could constitute the exercise of a workplace right in and of itself. The nub of their complaint is that in closing submissions the applicants impermissibly diverged from the case they pleaded, by contending that Mr Zwart was exercising workplace rights in instances where this was not pleaded. Essentially the respondents’ contention is that the only exercise of workplace rights pleaded is that Mr Zwart tagged the forklifts. They deny that it is open to the applicants to reply upon Mr Zwart’s actions in the meetings as constituting the exercise of a workplace right.

122 I do not accept that the case the respondents were called upon to meet is as narrow as they contend. In my view the pleading can be seen to advance the claim that Mr Zwart was exercising a workplace right throughout the period on 5 August 2011 when the parties were dealing with the forklift safety issue. That issue commenced with Mr Zwart tagging the relevant forklifts because of his concerns about their safety and continued throughout the meetings called by the Visy managers as they sought a solution. I consider that to treat the pleading as only making a claim that Mr Zwart was acting as a health and safety representative when he tagged the forklifts and not when he was called into the meetings would be artificial in the extreme. Under s 25 of the OHS Act Mr Zwart had a right or obligation to take action in relation to the deficient warning beepers so as to maintain a safe workplace. Sections 73, 35 and 36 indicate that Visy was required to discuss resolution of this safety issue with Mr Zwart. In any event, commonsense and Visy’s policy of discussing such matters, indicates the same. The action taken in tagging the forklifts and the discussions that followed are inextricably linked.

123 Paragraphs 12 to 28 of the Amended Statement of Claim sets out in narrative form the actions of Mr Zwart on 5 August 2011 in identifying the deficient beepers, tagging the forklifts, attending and participating in the various meetings dealing with the issue of the beepers and, finally, approving the use of the repaired beepers. Immediately following this summary of events the pleading alleges:

29. At all the relevant times, including on 5 August 2011, Zwart had one or both of the following roles or responsibilities under the OHS Act, being:

(a) A role or responsibility under section 25 of the OHS Act to take reasonable care for his own safety and the safety of persons who may be affected by his acts or omissions at the Plant;

(b) A role or responsibility under section 58 of the OHS Act including to inspect any part of the workplace at which a member of the designated work group was in any situation involving an immediate risk to the health or safety of any person.

29A. Each of the roles or responsibilities referred to in paragraph 29 constituted a workplace right within the meaning of section 341(1)(a) of the [FW] Act.

29B. The conduct of Zwart set out in paragraphs 12 to 28 above constituted the exercising of a workplace right, namely the carrying out [of one] or both of the roles or responsibilities referred to in paragraph 29, within the meaning of section 340(1)(a)(ii) of the [FW] Act.

These paragraphs plead a claim that Mr Zwart’s actions in the meetings involved the exercise of a workplace right.

124 Even if I accept that the pleading could more clearly set out the claim that the events of 5 August should be considered together, I can see no basis for the respondents’ contention of procedural unfairness. It is plain that what occurred at the factory is that Mr Zwart decided to tag the forklifts because, in his view, the warning beepers were deficient. He then disagreed with the managers and ultimately with the WorkSafe inspector as to the temporary measures that should be used to address that problem. The pleadings adequately convey the claim that Mr Zwart was exercising a workplace right both when he tagged the forklifts and in the subsequent meetings. The actions of tagging the forklifts and then discussing the problem are properly to be seen as a single course of events connected by Mr Zwart’s refusal to depart from his view on forklift safety. This was also clear from the evidence and in opening submissions. In short, to look at the tagging of the forklifts as separate from the meetings to resolve that issue would be to ignore the reality of the dispute, and I do not read the pleading that way.