FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kingisland Meatworks & Cellars Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 48

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | KINGISLAND MEATWORKS & CELLARS PTY LTD First Respondent ALEXANDER MICHAEL MASTROMANNO Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The First Respondent Kingisland Meatworks and Cellars Pty Ltd (“King Island Meatworks”) in trade or commerce:

1.1 from at least 24 July 2008:

1.1.1 operated its meat retailing business under the business names “King Island Meatworks & Cellars” and “King Island Meatworks”;

1.1.2 used a logo in connection with its meat retailing business which contained an image of a white lighthouse above the words “KING ISLAND” in a red banner, above a smaller blue banner containing, in a smaller font, the word “MEATWORKS” (the Logo);

1.1.3 used the internet domain name “kingislandmeats.com.au” for the purposes of operating a website promoting its meat retailing business; and

1.1.4 published various images and words on its website at www.kingislandmeats.com.au which included the words “King Island” and “King Island Meatworks”;

1.2. since at least July 2010, displayed signs on the outside of premises from which it operated its business at 39A Church Street, Brighton, Victoria, containing the words “KING ISLAND MEATWORKS & CELLARS”; and

1.3. between at least 10 March 2009 to 2 August 2011, caused newspaper advertisements to be published which variously included the words “King Island”, the Logo and the domain name “www.kingislandmeats.com.au”;

and that by engaging in the above conduct King Island Meatworks represented that the meat being offered for sale through its meat retailing business, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown on or raised, or was otherwise from King Island when this was not the case, and thereby:

1.4. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of:

1.4.1 section 52 of the TPA, for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010;

1.4.2 section 18 of the ACL, for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011; and

1.5. made false or misleading representations concerning the place of origin of goods, in contravention of:

1.5.1 section 53(eb) of the TPA, for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

1.5.2 section 29(1)(k) of the ACL, for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011.

2. The Second Respondent (Mr Mastromanno), acting in his capacity as the manager and sole director of King Island Meatworks, was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contraventions by King Island Meatworks referred to in paragraph 1 above.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Injunctions

3. King Island Meatworks be restrained for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, whether by itself, its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of meat offered for sale including by way of:

3.1 the name under which it operates its business;

3.2 signage outside or inside its place of business;

3.3 the domain name used to operate any website;

3.4 the use of a logo, trademark or other device; and/or

3.5 representations made on any website promoting its business,

from making any representation to the effect that the meat offered for sale through its meat retailing business is grown on or raised, or was otherwise from, King Island, when it is not.

4. Mr Mastromanno be restrained for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of meat offered for sale, from being directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or party to the making of any representation to the effect that the meat offered for sale is grown on or raised, or otherwise from King Island, when it is not.

Publication orders

5. Pursuant to section 86C of the TPA and/or section 246 of the ACL that King Island Meatworks, at its own expense:

5.1 within 7 days of the date of this order, display a corrective notice on the external facing window and the front door of its business premises at 39A Church Street, Brighton (business premises) each notice to be:

5.1.1 in the terms, colours and form of Annexure A;

5.1.2 of a size no less than 30 centimetres horizontal by 42 centimetres vertical;

5.1.3 prominently placed for ease of reading by consumers outside the premises and separate from other notices or advertisements; and

5.1.4 displayed for a period of no less than 28 days from the date on which it was first displayed;

5.2 within 7 days of the date of this order display corrective notices inside the business premises, each notice to be:

5.2.1 in the terms, colours and form of Annexure A;

5.2.2 of a size not less than 20 centimetres horizontal by 30 centimetres vertical;

5.2.3 prominently placed for ease of reading by consumers inside the premises and separate from other notices or advertisements; and

5.2.4 displayed for a period of no less than 28 days from the date on which it was first displayed.

6. King Island Meatworks file and serve on the ACCC within 7 weeks of the date of this order, an affidavit of its proper officer verifying that it has carried out its obligations under the orders at paragraph 5 above, detailing what it has done, including:

6.1 providing actual size copies of the notices displayed pursuant to 5.1 and 5.2 above; and

6.2 specifying the addresses at which notices were displayed pursuant to 5.2 above.

Pecuniary penalties

7. Pursuant to section 76E(1) of the TPA King Island Meatworks pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in respect of the contraventions of section 53(eb) of the TPA referred to in paragraphs 1.5.1 and 1.5.2 and of section 29(1)(k) of the ACL referred to in paragraphs 1.5.1 and 1.5.2 above, in the amount of $50,000.

Costs

8. The Respondents pay the ACCC's costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, including any costs reserved.

Note: Settlement of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

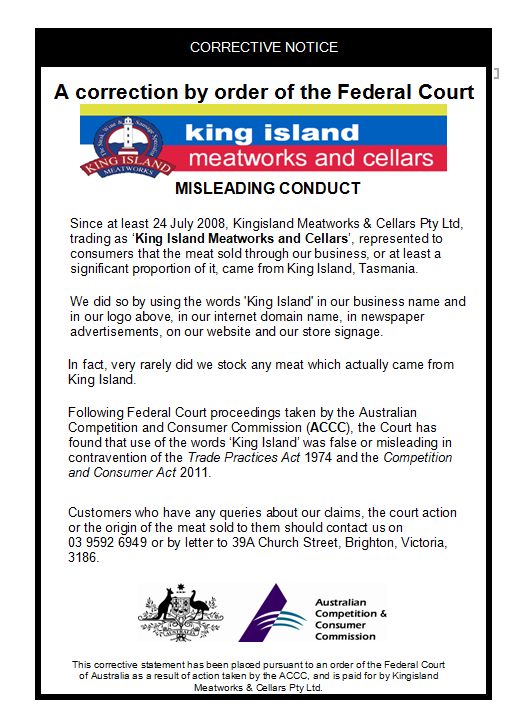

Annexure A – Corrective notice for business premises

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 889 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant

|

AND: | KINGISLAND MEATWORKS & CELLARS PTY LTD First Respondent ALEXANDER MICHAEL MASTROMANNO Second Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MURPHY J |

DATE: | 5 february 2013 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

1 In earlier reasons for judgment (ACCC v Kingisland Meatworks and Cellars Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 859) (“the contravention judgment”) I made findings that the first respondent, Kingisland Meatworks and Cellars Pty Ltd (“King Island Meatworks”) had made false or misleading representations about the place of origin of the meat it sold, which also constituted misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct likely to mislead or deceive, in breach of:

(a) ss 53(eb) and 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“TPA”) for the conduct engaged in prior to 1 January 2011; and

(b) the successor provisions ss 29(1)(k) and 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) for the conduct engaged in after that date.

I also found that the second respondent, Mr Alexander Mastromanno was knowingly involved in those breaches within the meaning of s 75B of the TPA and s 232 of the ACL.

2 The contravening conduct consisted of King Island Meatworks’ use of the words “King Island” within its business name “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” and the promotion of its business through the use of this name on its premises, on its website, in newspaper advertisements, in its domain name, and the use of a logo which displayed the business name underneath a picture of a lighthouse (“the Logo”), together with the use of the words “King Island” elsewhere in its newspaper advertisements and on its website. This conduct represented that the meat offered for sale through its Brighton shop, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown on or raised or was otherwise from King Island, when in fact very little or none of that meat was from King Island.

3 These reasons for judgment concern the relief I have ordered in relation to those breaches. In this regard Mr Mastromanno swore a further affidavit in relation to King Island Meatworks’ size and profitability, and the parties made written submissions.

4 The ACCC seeks various forms of relief set out below, some of which are not opposed by the respondents. For the reasons set out below I have made declarations and orders as follows:

(a) Declarations regarding King Island Meatworks and Mr Mastromanno in relation to the contravening conduct. These are not opposed and I have made the declarations sought.

(b) Injunctions for three years restraining similar conduct by King Island Meatworks and restraining Mr Mastromanno from being knowingly concerned in such similar conduct. These are not opposed and I have granted the injunctive relief sought.

(c) A probation order in respect of King Island Meatworks, requiring it to establish a trade practices compliance program. This is opposed and I have refused to make such an order.

(d) A publication order requiring King Island Meatworks to display corrective notices at its premises, on its website, and in local newspapers. This is opposed. I have ordered a limited regime of corrective notices.

(e) Pecuniary penalties under s 76E(1) of the TPA and its successor provision s 224(1) of the ACL. The respondents do not dispute that a penalty is appropriate but propose a penalty of $10,000. I have ordered that King Island Meatworks pay a penalty of $50,000.

(f) An order that the respondents pay the ACCC’s costs. This was opposed. I have ordered that the respondents pay the ACCC’s costs of and incidental to the application.

declarations

5 The ACCC seeks declarations in the following terms:

1. That the First Respondent ("King Island Meatworks"), in trade or commerce:

1.1 from at least 24 July 2008:

1.1.1 operated its meat retailing business under the business names ‘King Island Meatworks & Cellars’ and ‘King Island Meatworks’;

1.1.2 used a logo in connection with its meat retailing business which contained an image of a white lighthouse above the words ‘KING ISLAND’ in a red banner, above a smaller blue banner containing, in a smaller font, the word ‘MEATWORKS’ (the Logo);

1.1.3 used the internet domain name ‘kingislandmeats.com.au’ for the purposes of operating a website promoting its meat retailing business; and

1.1.4 published various images and words on its website at www.kingislandmeats.com.au which included the words ‘King Island’ and ‘King Island Meatworks’;

1.2. since at least July 2010, displayed signs on the outside of premises from which it operated its business at 39A Church Street, Brighton, Victoria, containing the words ‘KING ISLAND MEATWORKS & CELLARS’; and

1.3. between at least 10 March 2009 to 2 August 2011, caused newspaper advertisements to be published which variously included the words ‘King Island’, the Logo and the domain name ‘www.kingislandmeats.com.au’;

and that by engaging in the above conduct King Island Meatworks represented that the meat being offered for sale through it meat retailing business, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown on or raised, or was otherwise from King Island when this was not the case, and thereby:

1.4. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of:

1.4.1 section 52 of the TPA, for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010;

1.4.2 section 18 of the ACL, for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011; and

1.5. made false or misleading representations concerning the place of origin of goods, in contravention of:

1.5.1 section 53(eb) of the TPA, for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

1.5.2 section 29(1)(k) of the ACL, for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011.

2. That the Second Respondent (Mr Mastromanno), acting in his capacity as the manager and sole director of King Island Meatworks, was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contraventions by King Island Meatworks referred to in paragraph 1 above.

6 The respondents do not oppose the making of these declarations, and the considerations applicable to the exercise of the Court’s discretion to do so under s 21 of the Federal Court Act 1976 (Cth) are uncontroversial.

7 The question in this proceeding is real rather than theoretical, relating as it does to the conduct of the respondents. The ACCC has a real interest in raising it, and the respondents are proper contradictors: see Forster v Jojodex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437 to 438. The declarations sought have utility because they:

(a) record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

(b) serve to vindicate the ACCC’s claim that the respondents contravened the TPA;

(c) may assist the ACCC in the future in carrying out the duties which are conferred upon it by the TPA;

(d) are of some assistance in clarifying the law;

(e) may inform consumers of the dangers arising from the respondents contravening conduct; and

(f) may assist to deter corporations from contravening the TPA.

: See ACCC v CFMEU [2006] FCA 1730 per Nicholson J.

8 I have made the declarations in the form sought by the ACCC.

injunctive relief

9 The ACCC seeks injunctions against the respondents in the following terms:

1. An injunction restraining King Island Meatworks for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, whether by itself, its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of meat offered for sale including by way of:

1.1 the name under which it operates its business;

1.2 signage outside or inside its place of business;

1.3 the domain name used to operate any website;

1.4 the use of a logo, trademark or other device; and/or

1.5 representations made on any website promoting its business,

from making any representation to the effect that the meat offered for sale through its meat retailing business is grown on or is otherwise from King Island, when it is not;

2. An injunction restraining Mr Mastromanno for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of meat offered for sale, from being directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or party to the making of any representation to the effect that the meat offered for sale is grown on or is otherwise from King Island, when it is not.

10 The Court has a broad discretion under s 232(4) of the ACL to grant injunctive relief. The exercise of the discretion requires that I consider all the circumstances of the case, including the scale of the contravening conduct, the respondents’ future intentions and the likelihood of damage to other persons if the contravening conduct continues: ACCC v Dermalogica Pty Ltd (2005) 215 ALR 482 per Goldberg J.

11 The ACCC submits that injunctive relief is appropriate as the respondents engaged in the contravening conduct over an extended period, did not appropriately respond to the warning letters sent by the ACCC, and did not accept, prior to judgment, that their conduct conveyed the alleged representations. They contend, and I accept, that these factors go to the likelihood of engagement in future conduct.

12 The ACCC also submits that the respondents continue to engage in the contravening conduct. The respondents deny this and say that on receipt of the contravention judgment King Island Meatworks ceased trading under the name “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” and registered the name “Steakout Meatworks and Cellars” as its new trading name on 18 August 2012. They say that King Island Meatworks removed the references to “King Island” from the signage at the Brighton shop, shut down the website, and commenced advertising in local papers under the new trading name of “Steakout Meatworks and Cellars”.

13 Neither party provided evidence to support their submissions on this issue. However, the respondents’ response was detailed including the dates upon which King Island Meatworks took various steps. The ACCC provided no detail whatsoever as to its assertion, and chose to make no response to the respondents’ assertions even though it made later submissions on other points. I infer that the respondents ceased the contravening conduct following the contravention judgment.

14 However, taking into account the respondents’ conduct over an extended period and that they did not oppose the injunctions, I have ordered the injunctive relief sought.

pecuniary penalties

15 Section 76E of the TPA empowers the Court to order a person to pay such pecuniary penalty as the Court determines appropriate for each contravention of s 53(eb) of the TPA occurring between 15 April 2010 and 31 December 2010. The successor provision s 224 of the ACL provides the same power to the Court in respect of contraventions of s 29(1)(k) of the ACL occurring on or after 1 January 2011. By ss 76E(3) of the TPA and 224(3) of the ACL the maximum penalty for each act or omission by a body corporate is presently $1.1 million, but a contravenor is not liable for more than one penalty in respect of the same conduct.

16 The ACCC seeks a pecuniary penalty in relation to each false or misleading representation concerning the place of origin of goods which occurred after 15 April 2010. It contends that a penalty in the range of $75,000 to $125,000 is appropriate. The respondents argue that a penalty in the range sought by the ACCC would be manifestly excessive and that a penalty in the vicinity of $10,000 is appropriate.

Applicable principles for assessing quantum of penalty

Mandatory factors

17 Section 76E of the TPA and s 224 of the ACL provide that in determining the appropriate penalty, the Court must have regard to “all relevant matters” and sets out mandatory but not exhaustive criteria which the Court must take into account:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(b) any loss or damage suffered;

(c) the circumstances in which the contravening conduct took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by the Court to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Other relevant factors

18 The principles for assessment of penalty under former s 76 of the TPA for contraventions of Part IV of that Act were summarised by French J (as he then was) in TPC v CSR Ltd (1991) ATPR 41-076 (“TPC v CSR”) at 52,152-53 and expanded on by the Full Court of the Federal Court in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v ACCC (1996) 71 FCR 285 (“NW Frozen Foods”) per Burchett, Kiefel and Carr JJ and in J McPhee and Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v ACCC [2000] FCA 365 (“J McPhee & Son”) per Black CJ, Lee and Goldberg JJ. It is uncontroversial that these factors are also relevant to the imposition of a civil penalty under s 76E of the TPA and s 224 of the ACL: ACCC v Global One Mobile Entertainment Ltd [2011] FCA 393 (“Global One”) at [110] to [112] per Bennett J; ACCC v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 382 at [68] to [69] per Perram J.

19 Numbered so that they follow consecutively from the mandatory factors, these factors include the following:

(e) the size of the contravening company;

(f) the deliberateness of the contravention and period over which it extended;

(g) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at a lower level;

(h) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the TPA or the ACL;

(i) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for enforcement of the TPA or the ACL;

(j) the financial position of the contravener; and

(k) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

Deterrence

20 The principal object of a pecuniary penalty is deterrence, both the need to deter repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (“specific deterrence”) and to deter others who might be tempted to engage in similar contraventions (“general deterrence”). This informs the assessment of the appropriate penalty.

21 Many authorities have recognised that deterrence is the primary reason for the imposition of a penalty. In TPC v CSR at 52,152 French J stated:

The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

22 The Full Court in NW Frozen Foods at 294 to 295 observed:

[t]he Court should not leave room for any impression of weakness in its resolve to impose penalties sufficient to ensure the deterrence, not only of the parties actually before it, but also of others who might be tempted to think that contravention would pay…

23 More recently, in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v ACCC [2012] FCAFC 20 (“Singtel Optus”) at [62] to [63] the Full Court per Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ explained:

There may be room for debate as to the proper place of deterrence in the punishment of some kinds of offences, such as crimes of passion; but in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business.

…

Generally speaking, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.

At [68], the Court held that:

The Court must fashion the penalty which makes it clear to [the contravenor], and to the market, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of the Act cannot be regarded as [an] acceptable cost of doing business.

Process for determining a penalty figure

24 The process to be applied in arriving at a particular penalty figure was considered (in the context of criminal sentencing) in Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357 where Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ held:

(a) the Court’s assessment of penalty is a discretionary judgment based on all relevant factors (at [27]);

(b) careful attention to maximum penalties will be required, in part because they operate as a yardstick against which to compare the worst possible case to all the relevant factors of the present case (at [31]);

(c) it will rarely be appropriate for a court to start with the maximum penalty and make proportional deductions from that maximum (at [31]);

(d) the court should not adopt a mathematical approach or assign specific numerical values to the various relevant factors (at [37]); and

(e) since the law strongly favours transparency, accessible reasoning is necessary, and while there may be occasions where some indulgence in an arithmetical process will better serve the end, it does not apply where there are numerous and complex considerations that must be weighed (at [39]).

25 Those considerations are also applicable to the assessment of pecuniary penalties under s 76E of the TPA and s 224 of the ACL: ACCC v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 683 at [68]; ACCC v Marksun Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 695 (“Marksun”) per Gilmour J.

the relevant Factors

26 I will deal now with each of the mandatory and other factors, accepting that there is some overlap between them.

The nature and extent of the contravening conduct

27 As I set out more fully in the contravention judgment at [11] to [16], from at least July 2008, King Island Meatworks represented to consumers that the meat being offered for sale at its Brighton shop, or a significant proportion of it, was grown or raised on, or was otherwise from King Island, when in fact it was not. This representation was made through the use of the words “King Island” within its business name and the promotion of its business through the use of this name on its premises, in its domain name, on its website, and in newspaper advertisements, together with the use of the Logo, and the use of the words “King Island” in its newspaper advertisements and on its website. I found that the conduct was aimed at a broad class of retail consumers of meat, delicatessen and wine products, concentrated within, but not limited to, Melbourne’s bayside suburbs.

28 King Island Meatworks’ use of the “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” trading name was a central part of its promotion of retail meat products for sale, and Mr Mastromanno accepted that he chose to use the words “King Island” in the name of the business because of King Island’s good reputation for its meat. His evidence was that when King Island Meatworks commenced trading at its Highett store in 2001, it sourced approximately 70 per cent of its meat from King Island and continued to do so until mid 2002 when the Tasman Meats Group purchased the King Island abattoir and stopped supplying to it. He says, and I accept, that King Island Meatworks did not voluntarily cease offering meat from King Island for sale.

29 Even so, from mid 2002 it no longer sourced any of its meat from King Island. After November 2010 it sourced only very small quantities of meat from King Island, commencing to do so following receipt of a letter from the ACCC on 24 November 2010 ("the November 2010 letter") which made an allegation that it was engaged in misleading conduct.

30 I accept that when Mr Mastromanno chose and first used the name "King Island Meatworks and Cellars" in relation to his business this conduct was not misleading because the majority of the meat the business sold came from King Island. I accept also that when the supply of meat from King Island ceased in mid 2002 the business had already established some recognition and goodwill associated with its name.

31 However as at mid-2002 - when it lost its ability to supply meat from King Island - the business had been trading for no more than 18 months. For the next 10 years, even though it offered little or no meat from King Island the respondents continued trading and promoting the business under a name and by reference to "King Island” on its shop signage, its domain name, its website, its Logo and in newspaper advertisements and falsely represented that the meat that the business sold, or it least a substantial proportion of it, came from King Island. However, even though the conduct started much earlier, the declarations of contravention sought relate only to the period from July 2008.

Loss or damage suffered

32 The ACCC argues that the respondents’ conduct has caused damage to consumers and competitors and submits that I should infer that the conduct has:

(a) deprived consumers of the opportunity to make a properly informed purchasing decision;

(b) induced consumers to pay more for the relevant meat products than they might otherwise have been prepared to pay, and that the respondents have profited as a result; and

(c) induced consumers to purchase meat products from King Island Meatworks rather than from its competitors, and that the respondents have profited at the expense of those competitors.

33 While no evidence was led on this issue, the effect of the misleading conduct must be that consumers have been deprived of the opportunity to make a properly informed purchasing decision. I am therefore prepared to make the first inference sought by the ACCC.

34 Given the state of the evidence, I am not prepared to make the second inference sought - that consumers were induced to pay more for the relevant meat products by the contravening conduct. The ACCC led no evidence about the place of origin, quality, and price of the meat that King Island Meatworks offered for sale from mid 2002, or any evidence as to the comparative quality and price of meat sourced from King Island in the same period. Mr Mastromanno’s evidence was that meat sourced from King Island was no longer of the same high quality as it had been when he first commenced purchasing it, and that he sold other types of premium meat. I cannot infer that the customers paid more than they should have for the meat they purchased.

35 The ACCC led no evidence as to any damage suffered by other butchers. While I accept that evidence identifying any such damage would have been difficult to produce the absence of any evidence is a relevant consideration. Although absence of evidence of loss does not necessarily mean a penalty will not be imposed (ACCC v Universal Music (2002) 201 ALR 618 at [17]), I am required to take the amount of any loss or damage into account.

36 Having inferred that consumers were deprived of the opportunity to make a properly informed purchasing decision, and noting that the trading name was chosen specifically because of the good reputation of meat from King Island, I infer that some consumers are likely to have purchased meat from King Island Meatworks rather than from its competitors because of the contravening conduct. The respondents therefore profited from the conduct. It follows that some loss and damage is likely to have been suffered by King Island Meatworks’ competitors but I am unable to evaluate its extent. In light of the fact that the respondents had a small business operating out of a single shop in suburban Melbourne, I am inclined to infer that the damage suffered by other butchers was at the low end of the spectrum.

The circumstances in which the act or omission took place

37 I have accepted that the reference to "King Island” in the trading name and in the respondents’ promotional activities was not misleading at the time that it commenced in 2001. I have accepted too that by mid-2002 when the respondents were no longer able to source meat from King Island, the business had already established some recognition and goodwill associated with its name. To change the name at that time would necessarily have involved some expense and some disruption to the business.

38 By 2005 there is further evidence that the name of the business was recognised by consumers, and because of the further usage and further promotional activities over time I infer that this recognition increased. In 2006 and 2007 King Island Meatworks won the National Sausage King competition which is likely to have further increased brand recognition. To change the name of the business at that time would have involved greater disruption to the business.

39 By this I do not mean to indicate that there is evidence that the respondents turned their mind to the question as to whether the business name and promotional activities were misleading, but chose not to change the name or the references to King Island because of the risk of disruption to the business. There is no evidence to this effect.

40 Notwithstanding the fact that usage of the business name commenced innocently, the respondents did not change the trading name of the business in mid-2002, even though the business was only about 18 months old at that time. For the next 10 years they traded and promoted the business under a name which conveyed a misleading representation. In 2005 they developed the Logo which reinforced the representation that a substantial proportion of the meat products sold came from King Island.

41 It is significant that following receipt of the November 2010 letter the respondents continued their contravening conduct, but began to source small quantities of beef from King Island. In my view this indicates that by then the respondents understood that unless they were selling meat sourced from King Island they may be in breach of the TPA through trading and promotional activities referring to King Island and King Island Meatworks.

42 In 2003 Mr Mastromanno was going through a traumatic separation with his wife. I accept that this may have distracted him. In early 2007 Mr Mastromanno licensed his brother Piero to trade as King Island Meatworks and Cellars at a shop in Highett. They fell out in early 2008 and Mr Mastromanno commenced County Court litigation against his brother. Mr Mastromanno’s evidence was that Piero refused to pay the agreed weekly licence fee of $500 per week after discovering that the business name registration had lapsed. The case was heard in September 2011 and judgment was delivered on 10 February 2012. I accept also that this litigation (partly conducted over the same time period as his interactions with the ACCC) may have also distracted him.

Previous findings of similar contravening conduct and previous undertakings and representations provided to the ACCC

43 There are no previous findings of contravening conduct against the respondents and no relevant undertakings or representations have previously been provided by the respondents.

The size of the contravening company

44 King Island Meatworks provided its financial statements and tax returns for the 2008/2009, 2009/2010, 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 financial years. Mr Mastromanno did not provide his tax returns.

45 The ACCC points to the gross revenue and profit figures for those years, noting that for the 2009/2010 to 2011/2012 financial years, King Island Meatworks earned revenue of approximately $1.26 million, $1.38 million and $1.48 million respectively, and gross profits of approximately $458,000, $543,000 and $681,000 respectively.

46 The respondents submit that this approach is misleading because King Island Meatworks’ profits after expenses and tax indicate that it is a small business with a small positive cash flow. They note that net profits (after expenses and tax) for the financial years 2009/2010 to 2011/2012 were $80,278, $90,800 and $30,885 respectively, and submit that these figures should be relied on in assessing the size of the business.

47 King Island Meatworks can reasonably be described as a small business, but this is of course a relative view. It has had a turnover of over $1 million in each of the last three financial years, including a turnover of almost $1.5 million in the most recent financial year. I will deal with its profitability and financial position later.

Deliberateness of the contravention and period over which it extended

48 The evidence is clear that the respondents chose the trading name with the intention of communicating to consumers that King Island Meatworks’ products were sourced from King Island. The ACCC argues that after mid-2002 the respondents knew that this was no longer true and yet maintained the trading name and the promotional regime around it.

49 The ACCC further submits that from at least 15 April 2010 King Island Meatworks engaged in the contravening conduct wilfully with a recognition and understanding of the likely representation that would be conveyed to consumers and with knowledge of the falsity of that representation. It contends that the risk the relevant conduct was contravening conduct was “reasonably obvious” in the sense articulated by Bromberg J in ACCC v Apple Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 646 (“Apple”) at [30].

50 As I have said, when King Island Meatworks first commenced trading the respondents’ conduct was not misleading. While its conduct became misleading from mid-2002, in assessing penalty the question is whether the conduct was deliberate from 15 April 2010.

51 The respondents argue that there was no deliberate breach of the TPA, but rather an omission which had its genesis in mid-2002 when King Island Meatworks was no longer supplied with beef from King Island. They typify the conduct as only a failure to change the legally registered trading name following refusal of supply, and argue that they had no appreciation of wrongdoing.

52 The ACCC argues, and I accept, that deliberateness does not require proof of intention to contravene the Act. It may be established if the conduct was deliberately engaged in with knowledge of the falsity of the relevant representation. However, I am not prepared to conclude that the respondents’ conduct in this case was deliberate simply because they continued to promote their business using the same trading name after their preferred meat supply had ceased, particularly as I consider that Mr Mastromanno is relatively unsophisticated. Prior to November 2010 there is no evidence that the respondents gave any consideration at all to the question of whether their business name and promotional regime was misleading or any evidence that they obtained any legal advice in that regard. While it may be said that the breach was "reasonably obvious", on balance there is insufficient evidence to infer that the conduct was deliberate prior to November 2010.

53 However, from November 2010 I infer that the respondents understood that unless King Island Meatworks was selling meat sourced from King Island there was at least a risk that they were in breach of the TPA. In fact, they sought to address this risk by purchasing a small quantity of meat sourced from King Island (but in nowhere near the quantities that would have been necessary to render the representation no longer misleading). From November 2010 I consider that the respondents’ conduct was deliberate.

Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at a lower level

54 The ACCC submits that the conduct was engaged in by the manager and sole director of King Island Meatworks, its most senior representative. It is clear that the contraventions were not perpetrated by a junior employee, but in the circumstances that King Island Meatworks is effectively a one man company I have given this factor little weight in my assessment of penalty.

Whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the TPA

55 There is little evidence as to whether the culture of King Island Meatworks or the attitude of Mr Mastromanno is conducive to compliance with the TPA or the ACL. There is no evidence of educational programs, or disciplinary measures in response to the contravention judgement. However I would not expect this given that King Island Meatworks is effectively a one man company, and the contraventions were by the owner. This factor too has been given little weight in my assessment of penalty.

The financial position of the contravener

56 As set out above, King Island Meatworks earned revenue of approximately $1.26 million, $1.38 million and $1.48 million respectively in the three financial years 2009/2010 to 2011/2012. It made gross trading profits of approximately $458,000, $543,000 and $681,000 respectively.

57 However, for the financial years 2009/2010 to 2011/2012 the company made net profits (after expenses and tax) of only $80,278, $90,800 and $30,885 respectively. The respondents strongly argue that King Island Meatworks’ financial position should be considered by reference only to its net profit.

58 The ACCC places more emphasis on the total revenue and gross trading profit figures arguing that they are a useful indication of the overall financial size of King Island Meatworks and its trading activities. In part this submission is based in an understandable caution as to the difficulties in scrutinising the particular financial treatment applied by a company and its advisers to its expenses. Wages of nearly $250,000 are the single largest expense in the 2012 financial year but the respondents did not provide any further detail as to the wages paid, including as to the recipients. While Mr Mastromanno provided copies of the financial statements and tax returns of King Island Meatworks he provided no information as to the wage or other benefits that he drew from the business. The ACCC also notes that the records show that while revenue increased by 17% from 2009/2010 to 2011/2012, salaries over that period increased by 34%.

59 In my view is appropriate that I take into account all of the financial information available including total revenue, gross trading profit and net profit in assessing the financial position of the company and its capacity to pay a penalty. King Island Meatworks’ profit in 2012 was lower than usual, but this was an unusual year because $140,223 was spent on legal expenses presumably in this litigation and the litigation between Mr Mastromanno and his brother. It is consistently profitable, has a strong turnover, and is financially healthy. The fact that the company had net assets of $264,885 as at 30 June 2012 is also plainly relevant.

Whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for enforcement of the TPA

60 The ACCC submits that King Island Meatworks has not cooperated with the ACCC or shown any contrition to date, but there is little evidence to support this. It is plain from the correspondence between the parties that they were unable to agree on terms of settlement, but I am not prepared to treat this as evidence of a failure to cooperate. The respondents were under no obligation to accept liability and were entitled to defend the proceeding: Global One at [132].

61 Conversely, while I accept that since the contravention judgment King Island Meatworks has changed its name, domain name, website, and signage to remove the words “King Island”, and ceased advertising as King Island Meatworks, this is a necessary consequence of the judgment rather than evidence of contrition.

62 While there is no evidence that the respondents have shown a positive disposition to cooperate with the ACCC, this factor has attracted little weight in my assessment of penalty.

Whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert

63 I have already addressed the issue of the deliberateness of the contravening conduct above at [48] to [53]. I do not consider that the contravening conduct was covert, or systematic. Although it continued over about 10 years, it is not until after November 2010 that I infer that the conduct was deliberate.

The parity principle

Parity principle

64 Consistently with the requirement for "equal justice" this principle requires that similar contraventions should incur similar penalties, other things being equal. The difficulty is that “other things are rarely equal where contraventions of the Trade Practices Act are concerned”: NW Frozen Foods at 295.

65 The ACCC seeks to rely on Marksun which also related to misleading representations about the place of origin of goods. Marksun represented that its Ugg boots were made in Australia when they were not, and used the Australian Made Logo without authorisation. The period of the contravening conduct was over eight or nine months. The Court imposed penalties totalling $330,000 against Marksun in relation to two courses of conduct in contravention of s 53(eb) of the TPA. While there was little evidence as to Marksun’s size there were some indications that it was well resourced which suggested that it was a considerably larger company than King Island Meatworks.

66 The ACCC also seeks to rely on the orders made in proceedings brought by the ACCC against Hooker Meats Pty Ltd (VID 888 of 2011) (“Hooker”) which involved a misrepresentation that meat was from King Island. A penalty of $50,000 was agreed by the parties by reference to an agreed statement of facts. The file reveals that the orders were made for the reasons advanced in joint submissions. In Hooker the misleading representation that meat was from King Island was not conveyed through the use of a registered trading name, but by reference to particular meat products it sold. King Island Meatworks faced no allegation of misrepresenting that specific meat products were from King Island, and one might therefore view Hooker Meat’s contravention as more serious than the present case. Hooker Meats is a much larger business having an annual turnover of approximately $10 million, although it made a small loss in the relevant financial year. Hooker Meats cooperated with the ACCC in reaching a consent position and avoiding the need for a trial, whereas the respondents did not.

67 More than anything, the ACCC’s attempt to rely on these cases to assist its submissions on penalty illustrates the difficulty in comparing penalties awarded in relation to differing sets of factual circumstances. As Middleton J said in ACCC v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2010) 188 FCR 238 (“Telstra”) at 255, cited with approval by the Full Court in Singtel Optus at [60]:

It is apparent that there are many difficulties in simply referring to penalties previously imposed for contraventions of legislation in widely differing circumstances or in circumstances where some of the factors are similar but others dissimilar to those of the present proceeding. In each case, the Court must take into account the deterrent effect of the penalty and the fact that the penalties "should reflect the will of Parliament that the commercial standards laid down in the Act must be observed but not be so high as to be oppressive" [citation omitted].

The combination of circumstances in the two cases put forward are different from the present case and they have been of little assistance in assessing the penalty.

Totality

68 The authorities provide that related contraventions may be treated separately by reference to differences such as different methods of publication and different periods: Singtel Optus at [51] to [55]. The totality principle requires that the total penalty for all related contraventions ought not exceed what is proper for all contravening conduct involved: TPC v TNT Australia Pty Ltd (1995) ATPR 41-375. The rationale of the principle is to ensure that the proposed penalty is proportionate when the contraventions are viewed collectively.

69 However, I held in the contravention judgement that the shop signage, newspaper advertisements, domain name and website all conveyed the same representation in substantially similar ways and that they operated together when the consumer viewed more than one medium. In these circumstances I accept the ACCC’s submission that this is a case (which the ACCC describes as rare) in which the penalty may conveniently be considered on the basis that, while there are multiple contraventions they all arise from the same conduct.

70 It would though have been possible to view the shop signage, the newspaper advertisements, the domain name, the website and the use of the Logo as separate contraventions. It would also have been possible to view the contraventions after November 2010 separately on the basis that they are more serious than those occurring before that date. However, I have chosen a different method and in fixing the penalty I have had regard to the overall total and sought to ensure that the penalty is proportionate and appropriate, whichever of the possible methods of assessment are used.

Assessment

71 I have set out my view in relation to each of the mandatory and other factors and taken them into account in this assessment, which is informed by the need for both specific and general deterrence. The misleading conduct occurred from at least 15 April 2010 and continued until August 2012, and it occurred by use of various different mediums. Although the references to “King Island” were not initially misleading, from November 2010 the conduct was deliberate. In my view a penalty must be imposed.

72 The respondents submit that to impose the penalty sought by the ACCC of $75,000-$125,000 would be financially crushing. They argue that a penalty of $125,000 would wipe out King Island Meatworks’ profit for the 2011 and 2012 financial years, and that even a $50,000 penalty would wipe out its profit for the 2012 financial year. They contend that the business is a small one with a small positive cash flow, and submit that a penalty in that vicinity of $10,000 is appropriate.

73 I do not agree. I consider that a penalty of $10,000 for a business with a turnover in 2012 of $1.48 million and gross trading profit of $681,000 is far too low. It would not sufficiently deter the respondents from repetition of the conduct, or sufficiently deter others from similar conduct. I must fashion a penalty which makes it clear that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of the TPA or the ACL cannot be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business: Singtel Optus at [68]. I consider that a significantly higher penalty is necessary although not one so high as to be oppressive: NW Frozen Foods at 293.

74 Conversely, while there is no evidence as to what Mr Mastromanno had been paid already by way of wages, I consider that the net profit of the business over the last three years is such that a penalty of $75,000 to $125,000 is more than is necessary to deter the respondents from repetition of the conduct.

75 I have fixed the penalty at $50,000. This is more than King Island Meatworks’ net profit for the 2012 financial year, but the profit that year was unusually low because of the monies spent on legal expenses. The net profit in the two prior years was more than the penalty, again noting that there is no evidence as to the wages or other benefits paid to Mr Mastromanno. I note too that King Island Meatworks had net assets at 30 June 2012 of $264,885 which also indicates its capacity to pay.

76 Notwithstanding that it exceeds King Island Meatworks’ net profit in the last financial year, a penalty of $50,000 is not oppressive in all the circumstances, particularly when the requirement for general deterrence is considered. As Merkel J observed in ACCC v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) (2005) 215 ALR 281 at [9] “…a penalty that is no greater than is necessary to achieve the object of general deterrence, will not be oppressive.” In fact, a larger penalty may be argued to be necessary to deter others from similarly offending but in my view, if all the circumstances of this case are taken into account, a penalty in this amount should operate as a sufficient deterrent.

77 In fixing the penalty I have also taken into account the fact that King Island Meatworks have incurred legal costs and are liable to pay the ACCC’s legal costs which may be large.

publication orders

78 The ACCC seeks orders for corrective notices and advertising to appear in the Bayside Leader newspaper, at King Island Meatworks’ premises, and on its website.

79 The respondents say and I accept that the King Island Meatworks’ website has been closed down. I do not consider that an order for corrective publication on another website is appropriate.

80 The authorities indicate various reasons for the making of corrective publication orders. These include:

(a) to alert consumers to the fact that there has been misleading and deceptive conduct: Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1 ("Medical Benefits Fund") at [53] per Stone J; ACCC v Virgin Mobile Australia Pty Ld (No 2) [2002] FCA 1548 at [22] per French J;

(b) to protect the public interest by dispelling the incorrect or false impressions that were created by the wide and far reaching advertising campaign: Medical Benefits Fund at [49]; ACCC v On Clinic Australia Pty Ltd (1996) 35 IPR 635 at 641 per Tamberlin J; and

(c) to support the primary orders and assist in preventing repetition of the contravening conduct: ACCC v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc (1999) 95 FCR 114 at [49] per French J.

81 These cases illustrate that a publication order is appropriate in the present case. However I have not ordered the extensive corrective advertising sought by the ACCC. Instead I have only ordered that corrective notices be displayed at the business premises of King Island Meatworks. I have also made some small changes to the proposed publication regime at those premises. The form of the notice sought by the ACCC is appropriate and it appears as Annexure A to the orders.

probation order

82 I do not consider that it is appropriate or necessary to require that King Island Meatworks establish a trade practices compliance program. The contraventions occurred primarily because of the approach of Mr Mastromanno to the use of the business name and not because of any absence of compliance training of his staff. I am not satisfied that a compliance program addressed to Mr Mastromanno is of any utility.

costs

83 The respondents submit that the ACCC has not conducted itself as a model litigant and that this should displace the usual rule that costs follow the event. I have perused the relevant correspondence between the parties and I am not satisfied that the ACCC has acted inappropriately or in a way which should displace the usual rule. In large part the respondents’ contention appears to turn on the notion that the ACCC was obliged to accept a settlement offer put by the respondents. It was not. In any event, in rejecting the settlement offer and pursuing the application the ACCC obtained a result more favourable to it than the settlement offer the respondents made.

84 I have ordered that the respondents pay the ACCC’s costs of and incidental to the application on a party-party basis. Should the respondents be able to establish that this causes them serious difficulties I expect the parties to enter a reasonable arrangement for instalment payments.

I certify that the preceding eighty-four (84) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Murphy. |

Associate: