FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kingisland Meatworks and Cellars Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 859

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 889 of 2011 |

|

BETWEEN: |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

|

AND: |

KINGISLAND MEATWORKS AND CELLARS PTY LTD (ACN 082 518 143) First Respondent ALEXANDER MICHAEL MASTROMANNO Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

MURPHY J |

|

DATE: |

14 AUGUST 2012 |

|

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (“ACCC”) brings this proceeding against the first respondent, a meat retailing business or butchery in Brighton, Victoria, named Kingisland Meatworks & Cellars Pty Ltd (“King Island Meatworks”), and against its manager and sole director, Alexander Michael Mastromanno, as second respondent. The ACCC alleges that King Island Meatworks made false or misleading representations about the place of origin of the meat that it sold, which also constituted misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive, in breach of ss 53(eb) and 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“TPA”) and the successor provisions of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). It alleges that Mr Mastromanno was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or a party to the false or misleading representations and the misleading or deceptive conduct.

2 In summary the ACCC case is that since at least July 2008 the first respondent promoted itself as “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” or “King Island Meatworks” on signage at its shop, in newspaper advertisements, by its internet domain name and on its website, as well is on its logo. King Island is a small island in the Bass Strait between Victoria and Tasmania which the ACCC contends has a reputation for its meat, and in particular high quality beef. The ACCC contends that this promotional conduct conveys the representation that the meat that King Island Meatworks sells, or it least a significant proportion of it, is grown or raised on or is otherwise from King Island.

3 King Island Meatworks does not deny that in order to promote its business it describes itself as “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” or “King Island Meatworks” and otherwise variously uses the words “King Island” on its shop signage, newspaper advertisements, domain name, internet website or logo. It does not contend that any significant proportion of the meat it had sold since 2002 was grown or raised on or otherwise from King Island. The dispute is limited largely to whether the admitted conduct conveys the representation alleged. It follows that if I find that King Island Meatworks’ conduct does in fact convey the representation alleged that it is false or misleading.

4 For the reasons set out below, I find that since at least about 24 July 2008 King Island Meatworks has represented to consumers that the meat being offered for sale through its Brighton shop, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown on or raised, or is otherwise from King Island. Because very little or none of the meat it offered for sale over the period was sourced from King Island each such representation constitutes:

(a) a false or misleading representation concerning the place of origin of goods sold by it in breach of s 53(eb) of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010, and in breach of s 29(1)(k) of the ACL for conduct from 1 January 2011; and

(b) conduct which is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 52 of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010, and in breach of s 18 of the ACL for conduct from 1 January 2011.

I have also found that Mr Mastromanno acting in his capacity as the manager and sole director of the first respondent, was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in, or party to these breaches.

The statutory framework

Transitional Arrangements

5 The title of the TPA, and certain of its provisions, were amended by the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 2) 2010 (No 103, 2010) and its short title became the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The transitional arrangements relevantly operate to ensure that the TPA in its form prior to 1 January 2011 applies to this matter in relation to conduct before that date and that the ACL applies to conduct after 1 January 2011. The relevant provisions in the TPA and the ACL are essentially the same and I shall usually refer only to the TPA provision. For conduct occurring after 1 January 2011 this should be taken as a reference to the successor provision in the ACL.

Legislation and Principles

6 Section 52 of the TPA provides:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.

Section 18 of the ACL is effectively the same.

7 Section 53(eb) of the TPA provides:

A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, in connexion with

the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connexion

with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or

services:

…

(eb) make a false or misleading representation concerning the

place of origin of goods;

…

This provision specifically impugns misrepresentations as to the place of origin of goods or services as conduct in breach of the TPA. Section 29(1)(k) of the ACL is effectively the same.

8 The relevant principles are uncontroversial. I am required to determine the following two issues:

(a) whether the pleaded representations are conveyed by the conduct described; and

(b) whether, as a matter of fact, the representations conveyed are false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

Although s 53 (eb) uses the term “false or misleading” there is no material difference in the application of this term to the application of the term “misleading and deceptive” in s 52: ACCC v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682.

9 Because the conduct was not directed at a specific person, both of these issues must be considered by reference to the class of consumers likely to be members of the target audience. It is necessary to isolate a hypothetical reasonable member of the target audience and consider the characteristics of this person. I must consider what meaning the ordinary or reasonable class member would ascribe to the conduct, excluding possible reactions to it that are extreme or fanciful. To consider the reaction of the reasonable class member is to consider the reaction of a significant proportion of the target audience or at least a not insignificant proportion: National Exchange Pty Ltd v ASIC [2004] FCAFC 90 at [23] and [70]; Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd (2008) 171 FCR 579 at [46] to [48] and [66] (“Hansen Beverage Co”). I must then determine whether the meaning conveyed by the representation is the same as the pleaded meaning, and whether that meaning is false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

10 Whether a representation arising out of a corporation’s conduct is false, misleading or deceptive is a matter of fact to be decided in the particular circumstances of the case, which should not be complicated or over intellectualised: ACCC v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2004) 208 ALR 459 at [49]. The test is an objective one: Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202 to 203.

The facts

The King Island Meatworks business

11 King Island Meatworks was incorporated in 1998 under the company name “Total Vision Enterprises Australia Pty Ltd”. It first began trading as a butcher’s shop in 2001 from premises at 14 Railway Parade, Highett, Victoria, using the business name “King Island Meatworks”. At that time it sourced a significant proportion of its beef from King Island. In 2002 it obtained a liquor licence and began trading as “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”. At around the same time, Mr Mastromanno put signage on the awning of the Highett shop which read:

King Island Meat Works and Cellars (est 2001)

The Steak & wine Specialists

12 In 2003 the company began trading from a second shop at 39A Church St, Brighton, Victoria, under the trading name “King Island Meatworks & Cellars”. In 2007, Mr Mastromanno entered an arrangement for his brother Piero to run the Highett shop under licence from the first respondent, but they subsequently had a falling out and parted ways. Since January 2008 Piero has traded at the Highett shop under the name “King Island Steak and Wine Co”, and the first respondent has traded at the Brighton shop which is managed by Mr Mastromanno. On 20 February 2008, the first respondent changed the name of the company to “Kingisland Meatworks & Cellars Pty Ltd”.

13 Throughout its trading life the main focus of King Island Meatworks’ business has been the sale of meat, with ancillary activities involving sales of wine, delicatessen goods and the operation of an in-store cafÉ. Mr Mastromanno described his business as an upmarket butchery and wine store. The evidence establishes that since at least July 2008 King Island Meatworks promoted this business by methods including by:

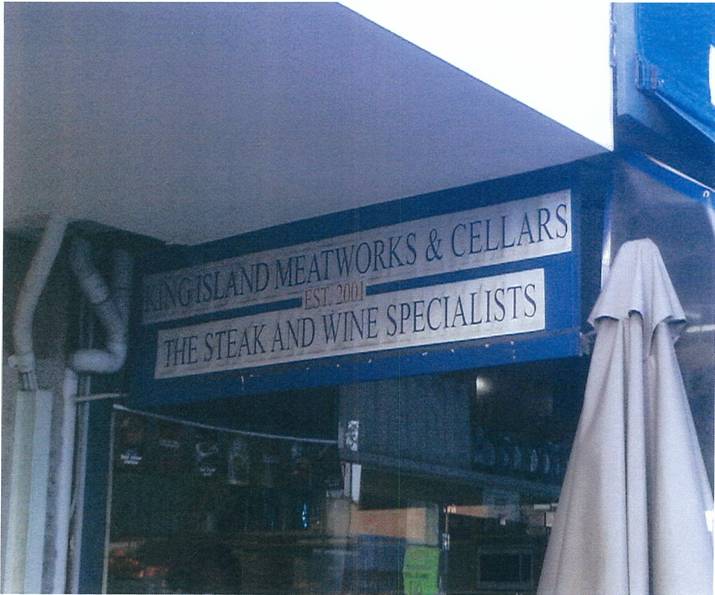

(a) Since at least July 2010 maintaining three large signs on awnings on the exterior of its Brighton shop describing the business as “King Island Meatworks & Cellars”. A photograph of this signage taken on 24 May 2011 is Annexure A to these reasons. It is not controversial that this signage was the same through the period.

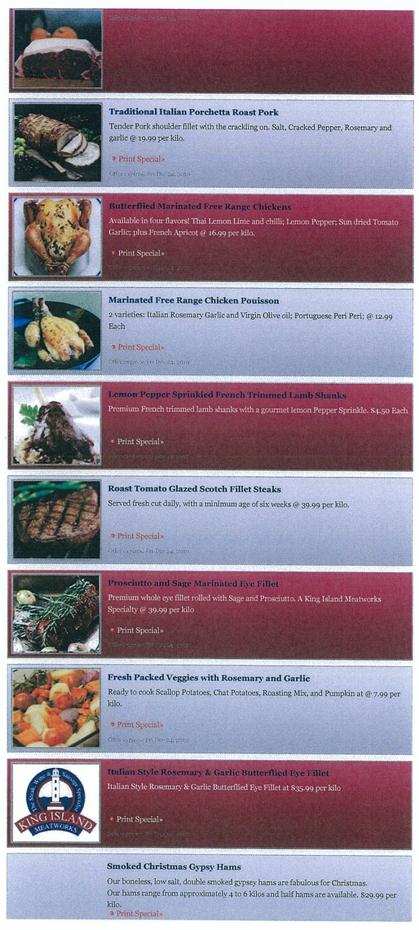

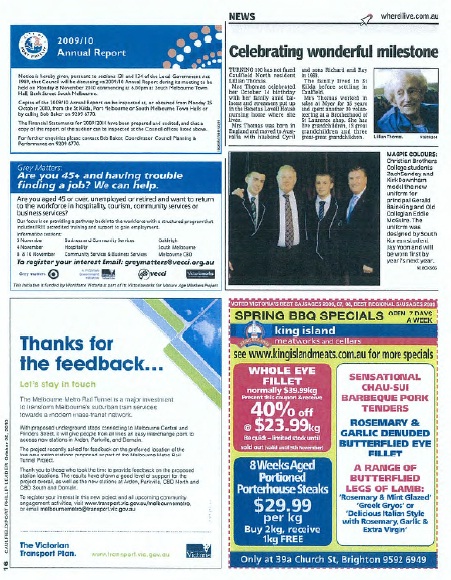

(b) At least between 10 March 2009 and 2 August 2011 running colour advertisements in one or both of two local newspapers, the “Bayside Leader” and the “Caulfield/Port Phillip Leader”, containing the words “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”, and/or the words “King Island Meatworks” and/or the words “King Island”. Sample advertisements during the relevant period are annexed to these reasons with Annexure B being advertisements published in Christmas periods and Annexure C being advertisements published at other times.

(c) Since 2005 using a logo containing an image of a white lighthouse above the words “King Island” in red above the smaller word “Meatworks” in blue (“the Logo”) in its newspaper advertisements and on its internet website. A copy of the Logo is Annexure D.

(d) Since 2005 using the internet domain name “kingislandmeats.com.au” to operate a website promoting its business;

(e) Since 2005 using the website at “kingislandmeats.com.au” to promote its business by use of the words “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”, “King Island Meatworks”, by reference to the “King Island cafÉ” operated at the Brighton shop, by use of the Logo, and by other use uses of the words “King Island”. Copies of screen shots of the website pages titled “Home”, “Gourmet”, “Specials”, “Awards” and “Contacts” taken on 9 March 2011 followed by a screen shot of the website “Home” page taken on 6 October 2011 are Annexure E.

King Island beef sold by the first respondent

14 Mr Mastromanno gave evidence that when King Island Meatworks first began trading in 2001, 70 per cent of the beef it sold was sourced from the King Island abattoir. His evidence is that he stopped selling beef from King Island in mid 2002 when the ownership of the King Island abattoir changed and he was unable to obtain a sufficient supply.

15 His evidence is that he did not again purchase beef from King Island until 7 February 2011, following a letter from the ACCC on 24 November 2010 in which it set out its concerns as to his description of his business under the name “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”. From 7 February 2011 to 16 November 2011 he made some small purchases of King Island beef through the distribution arm of Swift, with the balance of King Island Meatworks’ beef being purchased from 3 premium meat brands - Certified Australian Angus Beef, Clare Valley Gold and Southern Australian Premium MSA. He also purchased a brand of beef he described as a second tier brand, which it is unnecessary to name.

16 Other than the small number of identified purchases there is no evidence that any of the beef sold by King Island Meatworks after 2002 was grown or raised on or was otherwise from King Island. Although counsel for the respondents suggested that meat that was not labelled as King Island beef may nevertheless be from King Island, I am satisfied that little or none of the meat that King Island Meatworks sold in the relevant period was in fact from King Island.

The Target Audience

17 The signage on the King Island Meatworks’ Brighton shop, its newspaper advertisements in the local newspapers, its internet domain name, its website and its Logo are all aimed at promoting its business, and are not directed at any specific individual, but rather at a broad class of retail consumers of meat, delicatessen and wine products. The respondents submit that the target audience is geographically specific and generally limited to people in the Brighton area. King Island Meatworks also submits that it is only its existing customers and readers of its newspaper advertisements who may look at its website. I do not accept that the target audience is as restricted as this. The audience of the shop signage extends to those potential consumers passing along Church St, Brighton either on foot or by road, which is not necessarily limited to those people who live near or shop along that street. Further, the local newspaper advertisements were published to potential consumers in a number of Melbourne suburbs around Brighton and Caulfield. The King Island Meatworks domain name and website were published to the world, and no evidence was offered in support of the proposition that only existing customers or potential consumers who have read the newspaper advertisements tend to look at it. However, the website did not enable purchases to be made on it, and therefore any representation made on it only has an effect on potential consumers prepared to travel to the shop in Brighton in order to make a purchase.

18 In my view, while the target audience is largely concentrated in the Melbourne bayside suburbs surrounding Brighton, it also includes some potential consumers of specialty or “upmarket” butchery products across other parts of metropolitan Melbourne.

19 I must take into account that the shop signage, the newspaper advertisements and the website, are published to a large target audience and are designed to be seen by a wide range of persons, including the astute and the gullible, the intelligent and the not so intelligent, the well educated and the poorly educated: ACCC v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1904 at [17] per Gordon J; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199 per Gibbs CJ. As well as this, I consider that the target audience will include consumers with no, or only a passing, interest in the place of origin of meat through to those that take a keen interest in the provenance of any meat that they purchase.

Knowledge to be imputed to the target audience

20 Relevant to a determination as to whether the representation alleged was in fact conveyed are the characteristics of the target audience including the hypothetical reasonable consumer. The question arises as to what knowledge may be reasonably imputed to the class. The ACCC contends that the target audience should be taken to be aware that King Island had a reputation for meat production, and in particular production of high-quality beef.

21 It is not controversial that, in terms of meat production, King Island produces only beef in commercial quantities and not other meats such as lamb, pork, turkey, or squab. The only meat processing plant on the island is operated by JBS Australia Pty Limited (“JBS Australia”), the parent company of Swift Australia (Southern) Pty Limited (“Swift”), and it only slaughters and processes beef.

22 Mr Berry, a director of both Swift and JBS Australia, gave evidence that Swift owns registered composite word and image trade marks for “King Island Beef – Australia’s Premium Natural Beef” (“King Island Beef trade marks”). Mr Berry’s evidence is that usage of the trade mark is restricted to beef from cattle that have spent a minimum of 6 months grazing on the island. While he accepted the possibility that some cattle that had spent six months grazing on the island were processed by meat processors off the island and not identified as from King Island, I consider that the number of such cattle is likely to be low and of no significance to this case. There was also evidence that another meat processing company named “Greenhams” processes cattle from King Island on mainland Tasmania and has sold it as “King Island Beef” in the past. However this does not alter the effect of Mr Berry’s evidence.

23 His evidence is that Swift invests significant sums each year in advertising and promoting King Island beef products by use of the King Island Beef trade marks, including extensive in-store and media promotion of King Island beef products. JBS’ annual turnover for beef from King Island is approximately $35 million. His evidence is also that King Island Beef is positioned in the premium end of the Australian beef market, and that it has strong brand recognition across Australia. He says that King Island Beef commands a price premium in the market due to its quality. I accept Mr Berry’s evidence as to the use of the King Island Beef trade marks, its promotional expenditure in relation to King Island beef, and the positioning of King Island beef as being of high quality. This supports the ACCC contention that King Island has a reputation for meat production, and more particularly for high-quality beef.

24 Mr Mastromanno also frankly conceded that King Island had a very good reputation for its meat at the time that King Island Meatworks opened its business in 2001. The effect of his evidence is that he chose “King Island Meatworks” as the business name because he wanted to differentiate his business to consumers on the basis that it sold meat primarily from King Island, in part so as to position it as a business that sold high quality meat. Although Mr Mastromanno said King Island beef is no longer of the quality it was in 2001, he did not say that the reputation the meat then enjoyed had reduced in the intervening period. Mr Berry’s evidence, which I accept, indicates that King Island’s reputation for meat production and in particular high quality beef is a continuing one.

25 Finally, the respondents put into evidence an article dated 9 December 2010 from the website “Australian Food News” which related to government assistance to the abattoir on King Island. It quoted the then Premier of Tasmania, the Honourable David Bartlett MP as follows:

King Island beef is an iconic brand and the abattoir is crucial to the local economy…King Island undoubtedly has the best known brand for a small and isolated community in Australia and its iconic beef is extremely important to ongoing marketing and promotional opportunities.

This too is indicative of the island’s reputation for beef production.

26 Counsel for the respondents contends that this evidence is insufficient to establish that King Island has a reputation for producing meat, or in particular for producing high-quality beef, and that there is no basis to impute to the target audience any knowledge of such reputation. Counsel points to Halsbury’s Laws of Australia, (LexisNexis, Halsbury’s Laws of Australia, vol 15 (at 1 March 2006), 240: Intellectual Property, “Chapter V: Passing Off” [240-4595]) in relation to protection of reputation in passing off cases. The learned authors state:

In practice, the plaintiff’s reputation is generally proved where evidence of extensive sales or widespread advertising is available. Expert evidence, survey evidence and results from focus groups have also been used to prove reputation.

Various authorities are cited therein: Britt Allcroft (Thomas) LLC v Miller (2000) 49 IPR 7 at 15-16; Miller v Britt Allcroft (Thomas) LLC (2000) ATPR 41-792; Cat Media Pty Ltd v Opti-Healthcare Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 133 at [15], [43]; Telstra Corp Ltd v Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance Australia Ltd [2003] FCA 786; at [59]-[65]. However, in light of the evidence from Mr Berry and from Mr Mastromanno the respondents’ contention as to the insufficiency of evidence of King Island’s reputation is unsustainable.

27 It is also important to keep in mind that the sufficiency of the evidence required as to reputation is less in a case regarding misleading or deceptive conduct than in a passing off case: Hansen Beverage Co at 589 per Tamberlin J. Passing off relates to the unauthorised or improper use by one party of another’s reputation or brand, in which case evidence of any reputation is central. In a misleading or deceptive conduct case such as this, evidence of any reputation goes only to the knowledge to be imputed to consumers in considering whether the representation alleged was in fact conveyed.

28 The question as to whether King Island Meatworks’ conduct conveyed the representation alleged must be considered taking into account that the reasonable consumer is aware that King Island has a reputation for its meat production, and in particular for producing high quality beef.

The Representations Alleged

29 In its Amended Fast Track Statement the ACCC pleads that, since at least 24 July 2008, by:

(a) using one or both of the names “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” and “King Island Meatworks” on the signage of its Brighton shop, on its website and in the newspaper advertisements;

(b) using the Logo;

(c) displaying three large signs on the exterior of its Brighton shop containing the words “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”;

(d) using the internet domain name “kingislandmeats.com.au” for the purposes of operating a website promoting its business;

(e) publishing various words and images on its website including by using the words “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”, “King Island Meatworks”, referring to the “King Island cafÉ” operated at the Brighton shop, using the Logo, and also using the words “King Island” in other contexts (such as advertising particular specials or particular sausages for example);

King Island Meatworks, in each instance, represented in trade or commerce, to consumers, that the meat offered for sale to consumers through its meat retailing business, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown or raised on or was otherwise from King Island. I shall describe this as “the King Island origin representation”.

30 As I have already indicated, whilst denying that it conveys the representation alleged, King Island Meatworks does not deny the conduct set out above. It also concedes that, except for some limited sales after February 2011, it sold no meat sourced from King Island from mid 2002 onwards. As a result, if the representation alleged is conveyed by the conduct, it is uncontroversial that the representation is misleading.

Were the alleged representations conveyed

31 The question is whether the various pleaded usages of the words “King Island Meatworks and Cellars”, “King Island Meatworks” and “King Island”, in combination with use of the Logo, in the context in which they appear, convey to the reasonable consumer that the meat King Island Meatworks sells, or at least a significant proportion of, is grown or raised on or is otherwise from King Island. This is not a complex question.

32 A consideration of the effect of the impugned conduct on a reasonable consumer requires some consideration of the possibly different effects and impressions conveyed by the different promotional mediums used by the first respondent: ACCC v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1177 at [28]. It is also necessary to consider the different media used collectively, because a representation conveyed to a potential consumer by one medium is likely to have a continuing effect on that consumer when viewing another. In this case the different media all convey the same representation in substantially similar ways, and they operate together where a potential consumer views more than one medium.

Shop signage

33 The Brighton shop has large signs on its front and side awnings which display the words:

KING ISLAND MEATWORKS & CELLARS

EST 2001

THE STEAK AND WINE SPECIALISTS

34 I consider that the words “King Island” coupled with the words “Meatworks & Cellars” on these signs convey a connection between King Island and the first respondent’s business to the reasonable consumer. The words “King Island” operate descriptively on the words “Meatworks & Cellars”. They indicate that this is a butcher’s shop and that it is connected to King Island. As the reasonable consumer is taken to know of King Island’s reputation for the production of meat - and in particular high quality beef – it is likely that a reasonable consumer would understand from the signage that the shop sold meat that originated from King Island. That is, that the meat sold in the shop, or at least a significant proportion of it, was grown or raised on or was otherwise from King Island.

35 Mr Mastromanno’s evidence about his selection of the name “King Island Meatworks and Cellars” in 2001 supports this finding. He gave evidence that “I actually decided to call myself King Island Meatworks before I even opened the shop, so – and I knew that when I opened the shop, I was going to sell King Island meat.” He said that he wanted to indicate by the name that he sold meat primarily from King Island and that in doing so he was trying to position his business as a seller of quality meat. This reveals his intention to convey the King Island origin representation by the use of the business name he chose. I may more readily find that the representation alleged was made where a person intends to convey the representation: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [33].

36 The respondents contend that the large signs on the awnings convey other meanings unconnected to the origin of the meat sold in the shop. The suggested alternative meanings include that the proprietor of the business was from King Island, that the proprietor’s husband, wife, or grandparent were from King Island, that some of the products in the shop came from King Island (presumably in small proportions so as not to amount to the same as the King Island origin representation), that the proprietor of the business holidays on King Island, or that it is a reference to King Island in Queensland or overseas. I do not accept that these alternative meanings are conveyed. It is much more likely, given King Island’s reputation for meat production, that the representation conveyed is that the meat sold in the shop is sourced from King Island, or at least a significant proportion of it is.

37 King Island Meatworks submits that it never made any specific representation that any goods sold by it are from King Island, and contends that only a trading name such as “Strictly King Island (Tasmania) Goods” or “the King Island (Tasmania) Cooperative” could convey the meaning that all or a significant proportion of the goods sold are from King Island in Tasmania. I do not accept that only the trading names suggested by the respondents can convey the alleged representation. Further, the question is not whether King Island Meatworks made an express representation but rather whether the admitted promotional conduct operated to convey the representation alleged.

38 King Island Meatworks also refers to the fact that there are many butcher shops in Melbourne named after place names or regions such as “Perth Meats”, “Melbourne Meats” and “Alansford Meats”, and says that these names cannot be argued to say anything about the place of origin of the meat sold in the shop. That may be true of these business names because there is no suggestion that any of these places have a reputation for meat production. In those circumstances the reasonable consumer would likely understand that name to be no more than a description of the location of the shop, or the area serviced by the shop. Those are not the facts in this case.

39 The respondents also submit that the use of the words “King Island” would merely lead a consumer to wonder as to the origin as to the meat. I do not accept this as I do not consider that the use of “King Island” descriptively with “Meatworks and Cellars” is likely to confuse.

40 Another argument made is that the presence of the word “Cellars” operates to unsettle the King Island origin representation. The argument put seems to be that if the reasonable consumer does not make a connection between “King Island” and cellar products (and it is common ground there is none) then he or she would likely consider that “King Island” was not intended to convey a representation as to the origin of meat either. I do not agree. I consider that the reasonable consumer would understand the “cellar” reference for what it is, a reference to an ancillary wine sales business in relation to which no representation is made as to place of origin. I also do not consider that the further description on the signage of “The Steak & Wine Specialists” changes the impression conveyed by the words “King Island Meatworks & Cellars.”

41 King Island Meatworks submits that a reasonable consumer entering its premises would be immediately confronted with a large amount of meat identified as being from places other than King Island, and also by other fine food produce clearly not from King Island, such that they would be disabused of any misleading impression arising from the signage. While the Amended Fast Track Response pleads that most meat in the shop is labelled as to place of origin, insufficient evidence was led to establish this. However, even if this is treated as established it is not an answer to the ACCC case. If the King Island Meatworks’ conduct by its signage, newspaper advertisements, Logo usage or website induced a potential customer into the shop then it is not to the point that any misleading impression as to the origin of its goods was then corrected. By then, any misrepresentation conveyed had already operated to entice that person into the marketing web: ACCC v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1177 at [16] and [26]; ACCC v TPG [2011] FCA 1254 at [114], together with the authorities cited in those cases.

42 In relation to the large signage on the awnings outside its shop King Island Meatworks also makes the adventurous submission that the use of its business name is required in order that it fulfil its obligation under s 144(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”) to prominently display its registered business name at its place of business. It argues that the name which it uses was available for registration in February 2008 when it changed the company name, and says that the ACCC’s case must fail as King Island Meatworks’ conduct in using the name “is mandated by law”. It says that what is attacked by the ACCC is not discretionary conduct by King Island Meatworks and cannot be a breach of the TPA.

43 This submission too must fail. King Island Meatworks’ statutory obligation to display its name does not operate to enable the name it chooses to breach statutory consumer protections. Nor is there any injustice to King Island Meatworks in this approach. It is simply required to choose and display a company name that does not convey a false or misleading representation. Further, even if there is something in its argument - which there is not - King Island Meatworks is not required by the Corporations Act to display its registered name on large awnings on the outside of its premises. Counsel for the respondent conceded that compliance with the Corporations Act would be achieved by affixing a small notice as to the company name on a wall inside its premises. If it had taken that course it would be difficult for the ACCC to contend that consumers may be misled or deceived.

The King Island Meatworks’ Logo

44 In about 2005 the first respondent developed its Logo which it has used since then in its newspaper advertisements and on its internet site. As is clear from Annexure D, the Logo uses the words “King Island Meatworks”. “KING ISLAND” appears at the base against a curved red banner, and beneath it in smaller print and against a blue banner the word “MEATWORKS” appears. Above these words is a picture of a white lighthouse surrounded by a circular blue border on which the words “The Steak, Wine & Sausage Specialist” appear.

45 Mr Mastromanno gave evidence that he chose the lighthouse image because the King Island Dairy company used such an image and because King Island cheeses had a good reputation. I consider that the words “King Island Meatworks” set against the image of a lighthouse would reinforce to some degree the impression of a connection between King Island Meatworks’ business and King Island in the mind of the reasonable consumer. Even without the depiction of the lighthouse, for the same reasons as I set out in relation to the shop signage I consider that the use of the words “King Island Meatworks” on the Logo conveys the King Island origin representation.

Newspaper advertisements

46 The ACCC relies on weekly colour advertisements by King Island Meatworks in the Bayside Leader between 10 March 2009 and 26 April 2011, and fortnightly advertisements in the Caulfield/Port Phillip Leader between 3 August 2010 and 26 October 2010. 107 advertisements are in evidence, 13 of which are Christmas period advertisements and 94 being from other time periods.

47 As apparent from Annexure B, the 94 advertisements published outside the Christmas period all feature the Logo to the left of the words “King Island” appearing in bold white text against a blue banner, and beneath it the words “Meatworks and Cellars” in smaller un-bolded text against a red banner. For the same reasons as I have already indicated in relation to the shop signage, I consider that the use of these words in the advertisements, reinforced by the use of the Logo, conveys the representation that the meat sold, or it least a significant proportion of it, is grown or raised on or is otherwise from King Island.

48 Counsel for the respondents submits that the reasonable consumer would understand that a significant proportion of the meat sold was not sourced from King Island because some of the meats and wines featured are identified as coming from locations other than King Island. I do not agree. First, the majority of the advertisements largely consist of types of beef offered for sale and the place of origin of this meat is not identified. For the same reasons as I have already set out, in these circumstances the reasonable consumer would likely understand that it was sourced from King Island. Further, when other meat products are identified it is usually by generic or stylistic geographical adjectives, such as “Traditional Italian Porchetta”, “Traditional Italian Style Legs of Veal”, and “French Racks of Pork” which indicate a style of meat preparation and say nothing about its place of origin.

49 Finally, it is noteworthy that many of these advertisements also contain the offer “We will beat any other King Island offer by 10%”. Mr Mastromanno’s evidence is that this advertisement was simply a reference to his brother’s competing business which trades under the name “King Island Steak and Wine Co”. However I consider that it would likely operate to reinforce the alleged representation in the mind of the reasonable consumer, because it would be understood as an offer to beat any other price offer on meat sourced from King Island.

50 Only three products mentioned in the advertisements are specifically pointed to by the respondents as being obviously from other geographical locations. The first is wines grown in identified locations such as Mitchelton. I do not accept that the presence of advertisements for such wines operates to unsettle the representation conveyed by the advertisement. Wines sit in a separate category of offering and fall outside the King Island origin representation which relates to meat. It would be obvious to the reasonable consumer reading the advertisements that the origin of wines offered for sale would not bear on any representation as to the origin of the meat. Second, as a minor part of some advertisements featuring mostly beef, turkeys from Aldinga in South Australia are identified. I do not accept that this would operate on the mind of the reasonable consumer to correct the King Island origin representation. Similar considerations apply in relation to the few advertisements which feature Murraylands Beef. In fact, given the use of the words “King Island Meatworks” and they use of the Logo, the identification of Murraylands meat may convey the impression that this was an exception to the usual.

51 The King Island Meatworks also points to the fact that during the period when it resumed stocking a limited amount of King Island beef after February 2011 its newspaper advertisements sometimes identified specials such as “Certified King Island Whole Rump”. While a consumer might be puzzled as to why the origin of King Island would be re-emphasised in light of the representation already made, I do not consider that it operates such that the King Island origin representation is not conveyed.

52 There are many advertisements for other meats such as pork, lamb and poultry. The respondents submit that as these meats could not be from King Island the reasonable consumer would not understand the advertisements as representing that a significant proportion of its meat is from King Island. I do not agree. Notwithstanding his or her awareness of King Island’s reputation for meat production, I do not accept that the reasonable consumer would know whether or not pork, lamb or poultry are produced on King Island. No evidence was offered from which I am prepared to draw an inference that the reasonable consumer was aware that pork, lamb or poultry was not produced on King Island. It is also important to again note that the vast majority of the newspaper advertisements relate to beef. The advertisements convey the representation that at least this meat, or at least a significant proportion of it, was sourced from King Island.

Christmas newspaper advertisements

53 As is apparent from Annexure C, the advertisements which ran in the “Bayside Leader” between 9 November 2010 and 21 December 2010 in the lead-up to Christmas did not feature the Logo. Instead they feature the words “King Island” in large un-bolded type against a blue banner at the top of the frame with a “Santa” hat alongside, and the word “Meatworks” in smaller type directly underneath against a red banner. Below this appear the words “Christmas just wouldn’t be Christmas without…King Island Meatworks and Cellars”. The advertisements feature 2 beef “specials” but have a greater emphasis on meats other than beef, namely pork, poultry, and game. However, I do not accept the respondents’ argument that the advertisements therefore do not convey the King Island origin representation. These few advertisements are only a part of the larger promotional picture made up by the other longer running newspaper advertisements, the shop signage, the website and the use of the Logo. The reasonable consumer is more likely to see these advertisements for what they are - special advertisements for meats more often eaten at Christmas time - than understanding them in a way that operates so that the King Island origin representation is not conveyed.

Domain name and internet site

54 In 2005 Kingisland Meatworks acquired a domain name and established a website “www.kingislandmeats.com.au”. Because it refers to “meats” rather than “meatworks” and there is no reference to the ancillary cellar business it can be said that the use of the domain name conveys the King Island origin representation even more clearly than the shop signage.

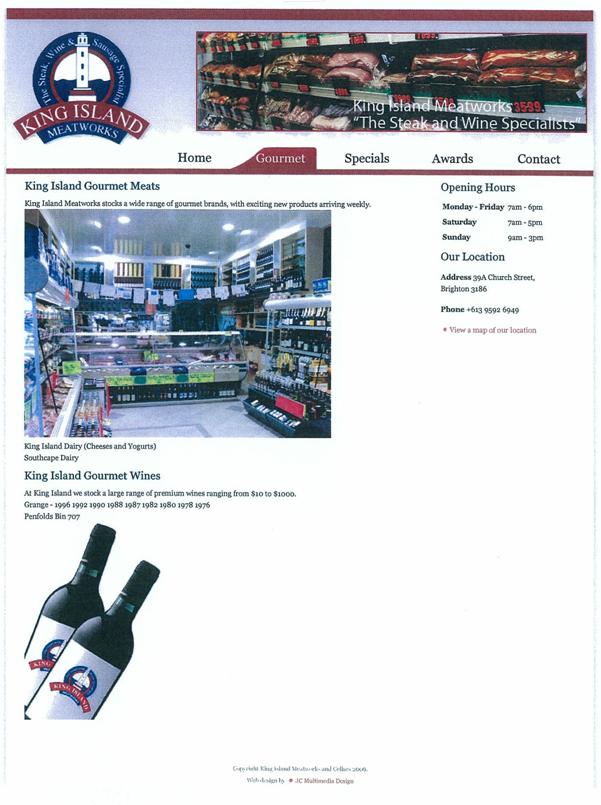

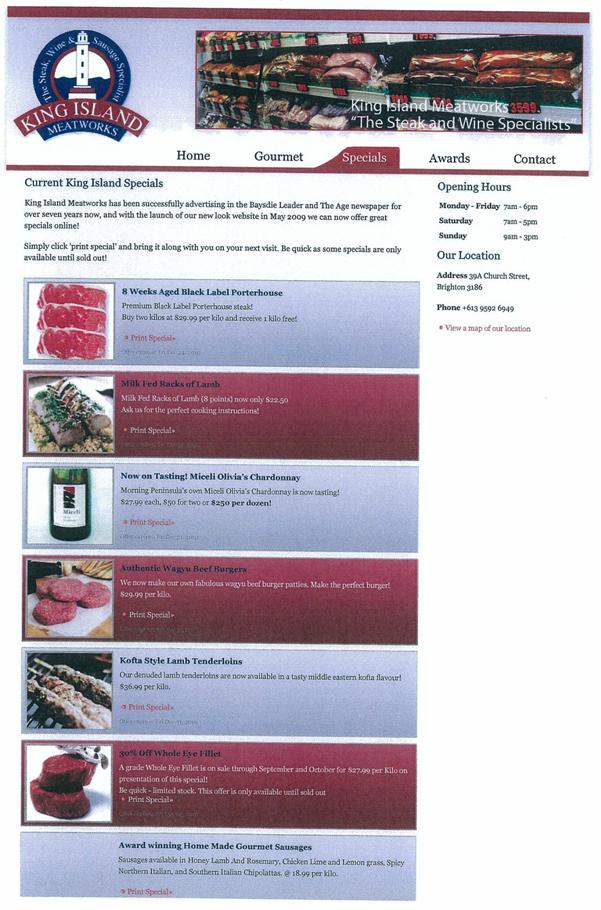

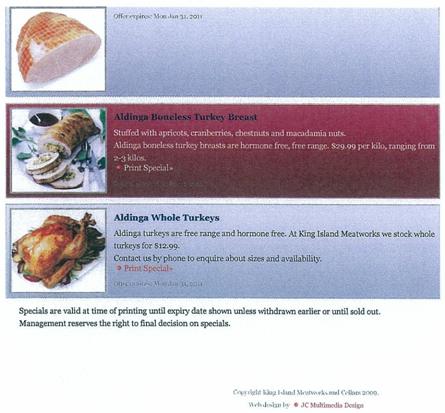

55 It is important to note that while the website is used to promote King Island Meatworks’ business the site is not set up to allow meat to be purchased through it. Meat can only purchased at the shop. As is apparent from each of the screen shots at Annexure E, a standard banner appears at the top of each page displaying the Logo on the left with a photograph of shelves of meat products in plastic packaging on the right, overwritten with the words “King Island Meatworks - The Steak and Wine Specialists”. I will deal with the website content primarily by reference to the “Home” and the “Specials” pages as these were the main focus of the respondents’ submissions.

56 The text on the “Home” page promotes King Island Meatworks’ reputation for high quality meats, sausages and deli products, and details the range of products which can be purchased from the shop, including cheeses, marinades, dips and wines. At the centre of the page there is a column of specials. On the 9 March 2011 screen shot this centre column remains headed, “Christmas as (sic) King Island” which is presumably unchanged from Christmas 2010, followed by the text “Christmas as (sic) King Island Meatworks is always special, drop in to our store to make a Christmas order today”. Below appear advertisements for Aldinga turkey, Aldinga turkey breast, gypsy ham, milk fed lamb racks, aged black label porterhouse, and Mornington Peninsula chardonnay. The origin or brand of the lamb and the porterhouse are not advertised, save that the porterhouse is described as “Premium Black Label”. Below this is an advertisement for the “King Island CafÉ” promoting the in-store cafÉ and its offering of coffee, cake, and sandwiches. Below the cafÉ section, appears a section headed “Awards and Associations” promoting the business’ history of awards and displaying links to 3 awards pages. The October 6 2011 screen shot does not contain the Christmas meats, but displays the same 3 weekly specials, and otherwise has the same layout.

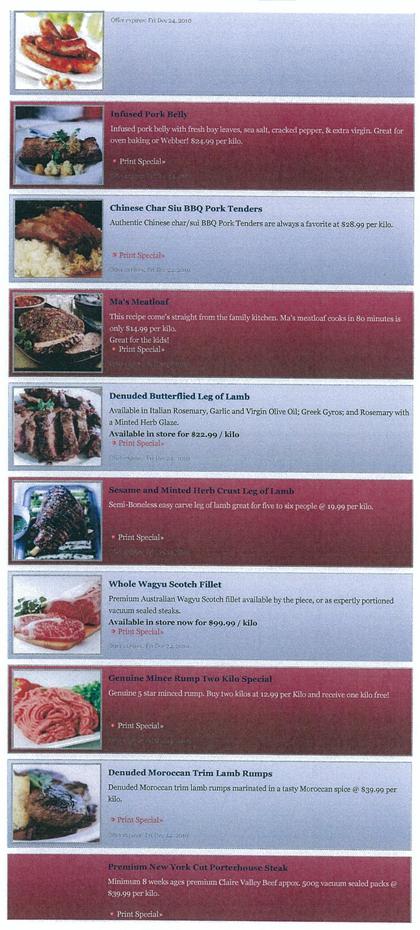

57 The “Specials” page contains the same content for both the 9 March and 6 October 2011 screen shots. The page is headed with text promoting the specials page and the launch of the website in 2009, followed by 27 items. Each item usually contains a photograph of the product. Of the 27 items on special, 9 are beef products and the 18 non-beef specials are a range of lamb, pork, poultry, and vegetable products. Of the 9 beef specials, only one, the Premium New York Cut Porterhouse Steak, which is described as “premium Clair Valley Beef”, is advertised by brand or origin.

58 Of the other 8 beef specials, 7 are described by reference to various characteristics, sometimes in combination. For example, some beef products are described by reference to quality (for example, the eye fillet special is described as “A grade Whole Eye Fillet”), some are described by reference to the style of preparation (for example, “Italian Style Rosemary & Garlic Butterflied Eye Fillet”), some are described by reference to the method of rearing (namely that the meat is “Wagyu”), and some are described by reference to being Australian in origin (for example the Wagyu scotch fillet is described as “Premium Australian Wagyu Scotch fillet”).

59 The non-beef specials are in some cases described by reference to the style of preparation (for example, “Traditional Italian Porchetta Roast Pork”, “Chinese Char Siu BBQ Pork Tenders”), by reference to the method of rearing (for example “Marinated Free Range Chicken Pouisson”), or by reference to the seasonings with which the meat has been marinated (for example “Sesame and Minted Herb Crust Leg of Lamb”). Of the 17 non-beef meat specials (the page contains one special for Mornington Peninsula Chardonnay) only the two Aldinga turkey specials are described by reference to brand or location of origin. Two of the non-beef specials are meat products apparently produced in-store: “Ma’s Meatloaf”, and “Award wining Home Made Gourmet Sausages”.

60 King Island Meatworks reiterates the contention it made in relation to the newspaper advertisements that - because some of the meats and wines featured are identified as coming from locations other than King Island - the reasonable consumer would understand that a significant proportion of the meat sold was not sourced from King Island. It emphasises the focus on the King Island cafÉ, the promotion of sausages and house made specialties, and the products listed by reference to geographic location. It also stresses the text alerting viewers of the website to the availability of King Island Dairy cheeses.

61 However, while there is certainly a greater range of products promoted on the website than in the newspaper advertisements, I consider that the King Island origin representation is nevertheless conveyed for essentially the same reasons as found in relation to the newspaper advertisements. In my view the prominence of the usage of the name “King Island Meatworks” and the Logo in the heading of each page, together with the frequency with which the words “King Island” are otherwise used as a reference to the business, and the substantial offering of meat from otherwise unspecified locations, operate in combination to convey the King Island origin representation to the reasonable consumer.

Other arguments

62 Mr Mastromanno gave evidence that in his 11 years of operation no consumer has ever complained to him about being misled as to the origin of the meat that King Island Meatworks sells, and the ACCC put on no evidence of any complaint by a consumer or a competitor. The respondents seek to rely upon the absence of such evidence. However, evidence that some person has in fact been misled is neither required nor conclusive. The question as to whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is an objective one for determination by the Court having regard to all the relevant facts.

63 Finally, the respondents sought to rely on the judgment of Mansfield J in ACCC v Australian Dreamtime Creations Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 1545 in which his Honour found that descriptions such as “Australia's original and best Aboriginal Art”, “Authentic Traditional Aboriginal Fine Art”, “Australian Aboriginal Art” and “Aboriginal Art” and objects created by “traditional Aboriginal artists” conveyed a representation that the artist was of Aboriginal descent, but not that the art was necessarily entirely made in Australia. The respondents contended that this case is analogous as it related to a place of origin representation. However, the facts of that case are quite dissimilar to those before me and the findings by his Honour are of little assistance to my judgment in this matter.

Mr Mastromanno’s liability

64 The evidence establishes that Mr Mastromanno is the manager, sole director and controlling mind of King Island Meatworks. It is clear from the evidence and submissions that he directed King Island Meatworks in making the representations which are the subject of the proceeding, and that its impugned conduct was completely within his knowledge and control at all material times. I find that he was directly knowingly involved in or a party to the contraventions I have found.

conclusion

65 By its shop signage, its newspaper advertisements, its use of the Logo, and its use of its domain name and website King Island Meatworks conveyed the representation that all, or at least a significant proportion, of the meat that it sold was grown or raised on or was otherwise from King Island. This was not the case as from July 2008 until February 2011 none of the meat it sold was sourced from King Island, and thereafter only very limited sales were made.

66 I find that King Island Meatworks made false or misleading representations concerning the place of origin of goods in contravention of s 53(eb) of the TPA for representations made up to 31 December 2010, and in contravention of s 29(1)(k) of the ACL for representations made from 1 January 2011. I also find that King Island Meatworks engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive in contravention of ss 52 of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010 and in contravention of s 18 of the ACL for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011.

67 I will hear the parties as to the relief to be ordered and costs.

|

I certify that the preceding sixty-seven (67) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Murphy. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE B

ANNEXURE C

ANNEXURE D

ANNEXURE E