FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Links Golf Tasmania Pty Ltd v Sattler [2012] FCA 634

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

LINKS GOLF TASMANIA PTY LTD (ACN 096 711 661) Plaintiff | |

AND: | First Defendant R.G. SATTLER NOMINEES PTY LTD (ACN 009 525 348) Second Defendant |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be listed at 10:15 am on 16 July 2012 for the purpose of receiving the parties’ submissions on the orders proper to be made to reflect the court’s reasons published this day, and as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 204 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | LINKS GOLF TASMANIA PTY LTD (ACN 096 711 661) Plaintiff

|

AND: | RICHARD GEOFFREY SATTLER First Defendant R.G. SATTLER NOMINEES PTY LTD (ACN 009 525 348) Second Defendant

|

JUDGE: | JESSUP J |

DATE: | 26 JUNE 2012 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

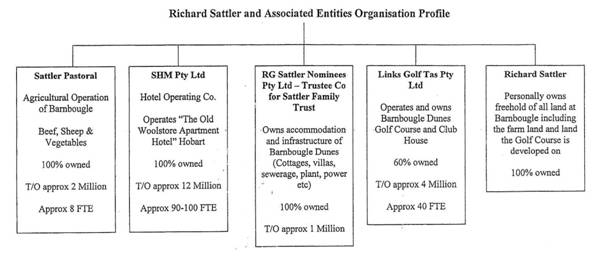

1 The plaintiff in this proceeding, Links Golf Tasmania Pty Ltd (“LGT”), operates a successful links golf course near Bridport in northern Tasmania called “Barnbougle Dunes”. The first defendant, Richard Sattler (“Sattler”), owns the land upon which the golf course is situated, and has leased that land to LGT under four successive ten-year leases commencing on 1 January 2003. Between 25 November 2002 and 16 July 2009, Sattler was a director of LGT. Between 10 May 2003 and 13 January 2010, he was chief executive officer (“CEO”). The second defendant, R.G. Sattler Nominees Pty Ltd (“Sattler Nominees”), is the trustee of Sattler’s family trust, and is the owner of 56.7% of the share capital in LGT.

2 There are several issues in the proceeding, but they all involve allegations by LGT that, while he was a director and the CEO of LGT, Sattler acted in breach of his fiduciary duty as such, and contravened ss 181, 182 and 183 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). A significant aspect relates to a second links golf course which Sattler built, and which he has operated, on a tract of land owned by him which lies adjacent to the Barnbougle Dunes course. That second course is known as “Lost Farm”. It is said by LGT that the opportunity to build and to operate that course belonged in equity to it, and that by taking the benefit of the opportunity for himself while he remained a director and the CEO of LGT, and/or by conducting his own business on that course in competition with the business of LGT, Sattler breached his fiduciary duty, and his duties under the Corporations Act. LGT claims an account of the profits which Sattler has made in the operation of the Lost Farm golf course business.

3 LGT’s allegations also relate to three loans which Sattler obtained in 2003, 2004 and 2008 while a director and the CEO of LGT. LGT says that the opportunity to obtain those loans came to Sattler because of his positions as such. Although the other members of, or investors in, LGT were aware of the first two of those loans, it is said that they were not aware of the terms upon which they had been obtained and, in that sense, that LGT’s consent to Sattler obtaining the loans was not fully informed. It is claimed that Sattler used the proceeds of those loans to increase his shareholding in LGT to a position in which, by July 2004, he held a majority of the share capital. The remedy which LGT seeks is the cancellation of the shares which were issued to Sattler on the strength of these contributions of capital. The position is different with respect to the third loan which Sattler obtained in 2008, the proceeds of which were used to fund the construction of the second golf course at Lost Farm. LGT claims that the opportunity to secure that loan came to Sattler because he was a director and the CEO of LGT, and, further, that Sattler used LGT’s resources and information for the purpose of obtaining this loan. Because the loan moneys were used as indicated, LGT’s case in this respect is said to contribute to its claim for an account of profits in relation to the Lost Farm golf course as such.

4 Other aspects of LGT’s case against Sattler relate to the diversion of its resources to the Lost Farm business, to the establishment of ancillary businesses at Lost Farm when they ought to have been established at Barnbougle Dunes, to the benefit of a grant from the Commonwealth and the construction of a wellness centre with the grant moneys, and to Sattler having contracted with himself for the payment to LGT of a commission for services provided in connection with accommodation units operated by Sattler on the land leased to LGT. The detail of these and other matters will be described in the course of my reasons below. LGT’s case as pleaded and opened also included an allegation that a Tasmanian government infrastructure grant which Sattler had received was sought and obtained in breach of his fiduciary obligation to LGT, but that allegation was dropped in the course of closing submissions.

5 It may seem odd that a company is here suing the person who is effectively its major shareholder and, necessarily, who controls the composition of its Board. The explanation lies in an order made by the court on 19 March 2010 by which individuals associated with minority shareholders, Peter Wood (“Wood”) and Justin Hetrel (“Hetrel”), were given leave, pursuant to s 237 of the Corporations Act, to commence this proceeding in the name of LGT. At times which were controversial, Wood and Hetrel were, along with Sattler, directors of LGT. Neither remains a director today. Wood and Hetrel were also amongst the small group of investors who provided equity capital to LGT, thus contributing to the funding of the construction and establishment of the Barnbougle Dunes golf course. I shall refer to the circumstances of that contribution, and to that of Sattler himself, in detail below.

6 My reasons which follow are much longer than would conventionally be either necessary or desirable for the resolution of a civil dispute broadly as outlined above. In part, that reflects the thoroughness and assiduity which characterised the factual and legal cases of both sides. But it reflects also the jurisprudence with which equity has surrounded the performance of the duties of a person in a fiduciary position, especially in a commercial context. In that respect, I am bound by authority to accept that the scope of the fiduciary duty must be moulded according to the nature of the relationship and the facts of the case. The practical consequence of that mandate has been that virtually every aspect of the transactions, communications and interactions as between Sattler and the others involved in LGT over a period stretching between late 2000 and mid-2009 must be regarded as at least holding the potential to affect, or to contribute to, the outcome of the present case.

7 As there were many people and organisations mentioned in the evidence in this case, for ease of reference I have appended to these reasons a list of the shorthand names by which they are referred to, and an indication of the place in the reasons where each is first the subject of mention.

The facts of the case

8 The narrative must commence well before what is now the Barnbougle Dunes golf course ever existed as such. Sattler had for some time been a successful businessman and investor in Tasmania. His first major investment was the purchase in 1975 of a small country fuel distribution agency in Tasmania. He turned this company into one of the largest of its kind in Tasmania, selling it in 1980. He then invested in hospitality. Over the next 20 years, he bought, developed and sold several hotel businesses and freeholds, and operated the Old Woolstore Apartment Hotel, which is now one of the biggest apartment hotels in Australia. His other line of work was agriculture, in which he maintained an interest. In 1987, he purchased a property of about 11,500 acres in Oatlands.

9 In 1989, Sattler purchased the farming property known as “Barnbougle”. This property, of about 13,000 acres, lies generally to the east of Bridport. It has a coastal frontage to Bass Strait, as well as substantial tracts of pastoral land. The coastal portion is divided by Great Forester River, which runs from south to north and discharges into Bass Strait. Locally, the course followed by the river through the Barnbougle property is also referred to as “The Cut”. The coastal portion, as I have described it, consists principally of sand dunes on which the main vegetation is marram grass. It seems that this area is not well-suited for productive farming. On the other part of the land purchased by Sattler in 1989, he and his wife Sally (“Mrs Sattler”) operate Barnbougle Farm. They run between 4,000 and 5,000 head of cattle, and produce about 5,500 tonnes of potatoes each year. The farm employs 8-10 full-time equivalent employees the year round, in addition to casual staff on a seasonal basis. The Sattlers have constructed irrigation infrastructure to place approximately 3,000 acres of this land under permanent irrigation. Barnbougle Farm is one of the largest farming properties in mainland Tasmania.

10 An important part of Sattler’s decision to purchase the Barnbougle property was the potential of the property for commercial development, including in particular that portion with a coastal frontage to Bass Strait. In 1990, a firm of consulting surveyors based in Launceston, Campbell Smith Phelps Pedley Pty Ltd (“Campbell Smith”), was engaged by Sattler, through his solicitors, to do some work relating to the severance of some of the land titles which constituted the Barnbougle property. Then, in October 1992, Sattler contacted Campbell Smith again, informing them that he was planning to review the potential for development of part of the coastal portion of Barnbougle for a canal residential development, a motel and a golf course. In early 1993, Ian Green, Paul Phillips and John Dent of Campbell Smith visited Barnbougle, and Sattler took them to the area to which he referred as “Lost Farm”. They stood on a sand dune with a survey map. Sattler pointed out to them the various developments which he had in mind. The surveyors marked up the map accordingly, including the letters “GC” adjacent to the coast and immediately to the east of Great Forester River. Those letters signified “golf course”. Mr Green prepared a note of their discussions, an item on which read “Golf Course in ‘lost farm’ area (an area of consolidated sand dunes – behind word ‘Waterhouse’ of ‘Waterhouse Beach’.” Mr Dent subsequently produced a sketch map of Sattler’s proposed developments, on which he marked (on the coastal position to the east of the river) the notation: “Golf Course & Motel? Lost Farm. (Road Access?)” This map was dated March 1993. As part of his proposal, Sattler commissioned an investigation of the potential of the coastal portion of the land for canal development. After testing, however, it was determined that this proposal would not be viable, due to the low-lying nature of the land. The commercial viability of such a development was also adversely affected by the 1989/1991 Tasmanian recession. In the result, Sattler thereafter focused upon the Barnbougle farming operation, and upon his other commercial interests in the hospitality industry.

11 And so, presumably, matters would have remained were it not for the entry upon the scene of Greg Ramsay (“Ramsay”) in late 2000. Ramsay spent his very early years on a farm near Bridport but, when he was about 6 years old, his family moved to a grazing property at Bothwell, 80 kilometres north of Hobart. They did, however, retain the Bridport property for farming and holidays. The Bothwell property incorporated an old golf course, and it seems that this excited in the young Ramsay an interest in golf, golf tourism and the history of golf. In 1995, then aged 18 years, Ramsay spent a “gap” year in the United Kingdom to learn about golf tourism. He worked at St Andrews in Scotland. He visited many other links courses throughout the United Kingdom, and worked at important events such as the British Open and the opening of the Duke’s course. In 1999, Ramsay worked part-time at Tourism Tasmania as a research assistant, during which period he was confirmed in the belief that Tasmania was missing out on golf tourism due to a lack of premium public golf facilities. In that year, he graduated from the University of Tasmania as a Bachelor of Commerce, majoring in marketing and finance. In early 2000, Ramsay travelled to the USA, to further his knowledge of and involvement with golf. He worked for a company called “Golf Solutions” which dealt in computer software for the management of golf courses. He was employed for several months to assist golf course managers in the USA implement and use Golf Solutions software. In mid-2000, he returned to St Andrews, still working for Golf Solutions, and also worked part-time in the Old Court Hotel, and as a caddy at a new links course, King’s Barns.

12 By this stage, Ramsay’s interest in links golf courses and golf tourism had become something of a passion. He learnt what he thought was required to establish and to run a links golf course. He read books on the design and construction of links golf courses, several of which were written by Tom Doak (“Doak”), an American golf course designer, and by Paul Daley (“Daley”), an Australian golf journalist and author. He was inspired by the idea that Tasmania was the ideal location for an iconic links golf course, and considered that the State needed such a course. He commenced to draw up a business plan to develop Tasmania as a world-class golf destination, by creating one new iconic golf resort, as well as upgrading other golf courses around the state. He called this plan the Pinnacle Golf Tasmania Business Plan.

13 In December 2000, Ramsay returned to Australia. Whilst visiting his family’s farm at Bridport, he noticed large sand dunes which ran adjacent to the beach to the east of the town. He noted that these dunes were high, that they extended inland for a considerable distance, and that they were covered with marram grass, a type of grass found on links golf courses in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The tracts of land which Ramsay thus observed were, of course, the coastal portion of Sattler’s Barnbougle property. Ramsay found out that the land was owned by Sattler, and decided to contact him to discuss the possibility of using the land for a links golf course.

14 In about late December 2000 (Sattler says just prior to Christmas), Ramsay and Sattler did meet at Barnbougle Farm. According to Sattler, Ramsay said that he was a golfing fanatic, and asked if he could look at some of the dune country of Barnbougle Farm with a view to developing a golf course there. Ramsay recalls that he explained to Sattler the characteristics of a great links course, and the type of land required to build one. He said that the property at Barnbougle looked ideal for the development of such a course. He said that Bandon Dunes and Sand Hills in the USA were examples of courses built and successfully operated on similar land.

15 Sattler took Ramsay for a drive over the property. This encompassed both sections of the property presently of interest – that on the west, and that on the east, of Great Forester River. Sattler told Ramsay that the section to the east of the river was known as the Lost Farm. Ramsay told Sattler that the Lost Farm was a more spectacular site for a links course than the dunes to the west of the river, but that it would be more expensive and difficult to develop due to poor access and the distance to services such as electricity and water. Ramsay identified what he considered to be the ideal location for a future clubhouse in the dunes to the west of the river. Such a site would not occupy any of the prime golfing land required for the course as such. According to an interview which Sattler gave to an American broadcast network on 27 June 2007, on the day of this inspection of the area “it was blowing horizontally off Bass Strait”, and Sattler thought to himself, “no, this boy’s just not sure what he’s on about”. Notwithstanding that, Ramsay told Sattler that he would come back with further plans and information, and they agreed to meet a few days later.

16 That meeting, still in late December 2000, took place at Sattler’s home and was attended also by Mrs Sattler. Ramsay told them that he wanted to develop a golf course in the dunes to the west of the river. He said that it need not be an imposition on their farming activities, or on their family home. He said that the essence of a links course was that it provided the golfer with a natural experience. Such a course would not require elaborate landscaping or extensive earth-works, but would rely on the natural features of the land. Such a course would require less water and chemicals for maintenance than a conventional golf course, and could be created with minimal disruption to, and low-impact on, the environment. He added that a links course on the Sattlers’ land could easily be undone if it were unsuccessful. He told the Sattlers that there was potential for more than one course on their land, and that both the western dunes and the Lost Farm area were ideal for links golf courses. After the meeting, Sattler and Ramsay again drove around the land. During the drive, Ramsay explained to Sattler that while accommodation could be included in the development of a golf course to the west of the river, it would not be crucial. Sattler said that, if the property were developed in the way suggested by Ramsay, he (Sattler) would retain control of the accommodation, as this was his speciality.

17 Although it is not very clear from the evidence in the present case in what order various undocumented events took place in early 2001, it does seem that, after these initial meetings, Sattler accepted Ramsay’s proposal, at least to the extent of facilitating the first practical steps that were necessary if the proposal were to become a reality. Consistently with this approach, Sattler introduced Ramsay to the Barnbougle Farm manager, Slim More. Sattler gave Ramsay a key to the farm gate, saying that this was necessary because he (Sattler) was often in Hobart attending to his hotel business. In his affidavit, Ramsay said that the provision of this key “permitted access to the Lost Farm so that I could enter the property and show people around”. Responding to this, Sattler said that the provision of the key was so that Ramsay “could familiarise himself with the property” rather than on the basis of any “solid undertaking” regarding Lost Farm.

18 There were three broad lines along which Ramsay’s energies were then directed: the actual construction of the golf course which he proposed, the business structure which would support the proposed course, and funding. As to the first, Ramsay’s priority was to engage a course designer whose talents and reputation would give the course the quality, and the standing in the golf community generally, that Ramsay considered the setting deserved. Unsurprisingly in the light of his earlier researches, Ramsay’s thoughts turned to Doak. He had designed the second links course at Bandon Dunes, a remote golf resort in Oregon which Ramsay considered to be a model for Barnbougle. Ramsay contacted Doak and told him of his passion for links courses. Ramsay said that he had read Doak’s books, and that he admired his knowledge and philosophy of links golf design, construction and “playability”. He told Doak that he was planning to develop a links golf course in northern Tasmania, that this would be the first of several courses on the site, that it would be modelled on Bandon Dunes, and that he wanted Doak to design the course. After this telephone conversation, Ramsay took a flight in an ultralight aircraft, from which he took aerial photographs of the Barnbougle property. Those photographs included the area to the west of Great Forester River, to which Ramsay’s immediate proposal related, as well as Lost Farm. He sent copies of the photographs to Doak.

19 In a subsequent conversation with Ramsay, Doak said that he was interested in the Barnbougle project, but that he had very little time available. If he were to be retained as the course designer, his involvement would be limited to designing the layout of the course, and providing an expert for shaping the greens. He said that he would need an Australian course designer with whom to work, and who could complete various other tasks involved in the design. Ramsay asked Doak for a list of Australian course designers with whom he would be happy to work, and Doak responded that Michael Clayton (“Clayton”) had been doing some good design work lately. He subsequently gave Ramsay a list of several Australian golf course designers, including Clayton. The two discussed the people named on the list, and Ramsay decided that Clayton was the most suitable candidate.

20 Ramsay then contacted Clayton, and told him that he wanted him to assist Doak with the design of the course at Barnbougle. Clayton visited the Barnbougle property in February 2001. Although Doak could not attend, it was possible for one of his employees then in Australia, Bruce Hepner (“Hepner”), to do so, and he visited the course at the same time as Clayton. Ramsay, Clayton and Hepner, and Clayton’s business partner John Sloan (“Sloan”), drove around the Barnbougle property, not including the Lost Farm area. The visitors all said that the land was a great site for a links course. Immediately after this visit (so I infer), Ramsay sent an email to Sloan dated 23 February 2001. A copy was not, according to the email header, sent to Sattler, but the only version of the email before the court was one which had been produced from Sattler’s discovery, and was a very poor copy. It was not the subject of any evidence by Ramsay. It referred to discussions between Ramsay and Sattler, from which there arose a contemplation that Ramsay’s proposed company could make use of the Barnbougle farm buildings, of a “spare house” (as an office) and of some other facilities.

21 After the visit of Clayton and others in February 2001, Clayton and Doak told Ramsay that they required an aerial survey of the site of the proposed golf course. Ramsay told Sattler that he intended arranging to have such a survey undertaken, and said that they should survey both the land intended for the course to be designed by Doak and the Lost Farm land, since they were “planning to develop courses on both sites”. Sattler agreed that this was a good idea. Ramsay subsequently ascertained that an aerial survey would cost about $6,000.

22 With respect to the business structure for the proposed golf course, Ramsay told Sattler that he intended to incorporate a company to be known as “Links Golf Tasmania Pty Ltd”, which would lease part of the coastal portion of the Barnbougle land to the west of Great Forester River, and would be responsible for developing the golf course and for raising the funds to do so. Ramsay also modified his Pinnacle Business Plan, so that it might stand as a business plan for the development of the new golf course on the Barnbougle property. He showed that plan to Sattler, whose observation (in an affidavit sworn in this proceeding) was that Ramsay’s vision extended well beyond Barnbougle Dunes, and involved golf courses all around Tasmania. According to Sattler’s evidence, “given its highly speculative nature I thought little of it.” There were several versions of the business plan placed into evidence, none of which was dated. There was little in the way of hard documentary evidence from which I could infer that a particular version was the one showed to Sattler. If the version showed to Sattler was one of the earlier ones, I would consider that Sattler’s reaction to it, mentioned above, was well-justified.

23 Considerations of business structure overlapped, in the thinking of Ramsay and in the documents he prepared, with considerations of funding and finance. One of those documents contained an indicative budget for the business which he proposed. Under a “best case scenario”, it anticipated that the business contemplated would require a capitalisation of $2.79m, of which $2.26m would be sourced as follows:

First Tasmania Investments | 200000 | |

Government Loan | 100000 | |

10 x $50 000 Golf Industry Shares | 500000 | |

16 x $50 000 Tas Bus. Shares | 750000 | [sic] |

Construction Equity | 710000 |

In this budget, the remaining $0.53m would be bank debt. At the time, Ramsay’s belief was that the sale of tradeable memberships, similar to the system which he had observed at the National Golf Club at Cape Schanck, was the best method of obtaining funds to develop the golf course with a minimum of additional equity required. Ramsay estimated that the earnings of the business, after interest and taxes, would range from a low of -$150,000 in the first year to a high of nearly $611,000 in the fifth year. An expense taken into account was “lease” set at 7% of profit before tax, and ranging from $0 in the first year to slightly over $68,000 in the fifth year.

24 These financial workings by Ramsay draw attention to what has been a very significant circumstance in the facts of this case: Ramsay was not (save to a very modest degree) an investor. He had access to nothing like the amount of capital that would be required for a business of the kind that he proposed. At this early stage, neither did Sattler have any intention of investing in the business, at least by way of cash contributions. And the need for cash became an issue for Ramsay. I have already mentioned that the aerial survey required by Doak and Clayton would cost $6,000. Another expense would arise in connection with obtaining planning approval for the golf course. Sattler introduced Ramsay to a town planner, Brian Risby (“Risby”), who said that his fee for obtaining planning approval for the construction of a golf course on the Barnbougle property would be in the range of $10,000 to $20,000, and that the total planning application costs would be about double that sum. Thus it was, from the outset, a major challenge for Ramsay to attract funding for the project. As the above workings demonstrated, he envisaged a mixture of direct equity, tradeable memberships, debt and government assistance.

25 However, in February 2001 and thereabouts, the inflow of cash from private investors and potential club members was an aspiration rather than a reality for Ramsay. As mentioned above, he encountered immediate needs to outlay substantial sums on aerial surveys and for planning approval. So he applied for financial assistance from the Tasmanian government. On 11 February 2001, he sent a copy of the “Executive Summary” from his business plan in its then state. The summary was headed “Barnbougle Dunes”, from which I infer that the proposed course had then been given the name which it would ultimately carry. It talked up the potential of Tasmania for golfing tourism, stating that the property at Barnbougle “provides the perfect starting point for developing golfing tourism in Tasmania”. The summary continued:

The author of this plan is Greg Ramsay, the Director of Ramsay Enterprises. He is 24 years old, with an exciting vision. Greg has global experience working in the golf and tourism industries, and has an obvious passion for both. His work has taken him from the linkslands of Ireland and Scotland, to the desert courses of Dubai, and across the United States of America. Tasmania is now poised to become a similarly world class golf destination.

Ramsay Enterprises has been able to secure the land for development through a very attractive equity and lease arrangement, at no up-front cost to the developer. Similarly, due to the rare opportunity to work with this type of prime golfing land, a world renowned golf design and construction firm has offered their services at no upfront fee, another considerable saving.

This proposal combines investment appeal with a variety of community and environmental benefits. Tasmania’s coastal beauty and idyllic lifestyle make it a likely candidate to become a world-renowned golfing destination. Barnbougle Dunes will be the start of establishing this reputation.

The summary made no reference to Sattler, or to the prospect of there being a second golf course at Lost Farm.

26 On 7 March 2001, Ramsay wrote a letter to Tim Lucas (“Lucas”) on the letterhead of “Ramsay Enterprises”, at Bothwell. Lucas was a manager in the Tasmanian Department of State Development (“the DSD”). The letter contained a formal application for funding, in the amount of $40,000. It was apparent from the terms of the letter (and Ramsay so deposed in his affidavit) that he had spoken to Lucas previously. In the letter, Ramsay said that his company, Ramsay Enterprises, had “negotiated a property in Tasmania’s north-east to be developed into a world-class golf facility”; that Sattler had committed his land “on a 20-year lease, with a 20-year option”; that the land had “a conservative book value of around $1 million”; and that Sattler had committed his machinery and employees to the construction process “an invaluable cost-saving that we have valued at over $100,000”. Ramsay estimated his own contribution, to that stage, at $35,000.

27 The then Barnbougle Dunes Business Plan, with appendices and financial projections prepared by Ramsay, was attached to Ramsay’s letter to Lucas. According to Ramsay’s affidavit, the business plan indicated that the project was “the creation of Pinnacle Golf Tasmania Pty Ltd …, a partnership between Ramsay Enterprises, and selected investors”. It added that “Links Golf Tasmania will lease the land at Barnbougle from Sattler Pty Ltd [sic] in the form of a share of profits”. Rather confusingly, three bullet points were placed alongside a marginal note which stated “The Mornington Peninsula has rapidly become one of Australia’s most popular and important golf destinations”. The financial projections attached to the letter included the capitalisation requirements to which I have referred at para 23 above, and a “worst case scenario” in which slightly different figures were set out. The only reference to the possibility of a second course was on a page headed “Opportunities/Future Developments”: one of three bullet points under which stated only “2nd 18 holes”. So far as I can make out, this was the earliest written record of Ramsay’s aspiration to involve his prospective company in the development of a second golf course on Sattler’s land.

28 Although it was some months before Ramsay’s application for State government funding was approved (a subject dealt with below), Ramsay caused the aerial survey to go ahead, and that occurred on 28 March 2001. By early May 2001, Ramsay was in possession of a survey map of the Barnbougle Dunes course, generated from the aerial survey. At that stage, although the Lost Farm area had also been surveyed, Ramsay did not have the data converted into a survey map as such.

29 On 7 May 2001, Ramsay caused LGT to be incorporated. He held the only issued share in the company, and he was the only director. The registered office, and the principal place of business, were at Ramsay’s residence in Bothwell. In the same month, Ramsay opened a cheque account, upon which he was the only signatory, in the name of LGT.

30 On 22 May 2001, Doak informed Ramsay by email that he had received the aerial survey maps of the area in which the proposed course was being considered. In the email, Doak referred to the topography of the area, and the impact it might have on routing options and clubhouse location. Because of other commitments which Doak had in late 2001 and early 2002, he stated that he could “cut a good deal on the design of your project in Tasmania”, but that his time was limited. He proposed three contract options for Ramsay to consider: (1) his report would be limited to design as such, with construction being supervised by an Australian partner, such as Clayton; (2) he would design the course and supervise the construction, under which arrangement he would “defer” some of his own fees, but not those of his associates, such that at least $US250,000 would have to be paid, in addition to the fees that were to be deferred; (3) he would design the course and make paid trips as necessary “during construction to try to help out”, under which he would charge $US150,000, and would not allow the use of his name in association with the course unless he approved the final product. There is no evidence of Ramsay having responded to this email from Doak, but I infer that he did at some point and in some way, since Doak’s involvement in the design of the course became a reality, as I shall mention further below.

31 In evidence is a document, prepared by Ramsay, which sets out five alternative arrangements for LGT to obtain land, or rights to land, for the purposes of the proposed golf course. Under each alternative, the benefits and weaknesses, for various parties, were noted. Ramsay said that this document was prepared in May 2001, and that he discussed it with Sattler. If it was prepared and discussed in May, it stands as the second documentary record (ie after that referred to in para 27 above) of Ramsay’s aspiration as to a second course.

32 The first alternative set out in Ramsay’s document of May 2001 was for LGT to purchase the land from Sattler for about $1m. The weaknesses of this included LGT’s reluctance to risk its viability by overcapitalisation and Sattler’s unwillingness “to lose control of parcels of land”.

33 The second alternative was:

LGT leases the 2 titles of land for 20 years with a 20 year option. Lease of 7% of operating profit payable from year 3 with a minimum lease as determined by worst case financial projections. Sattler Pastoral has nominee on the board of LGT to protect his interest in the facility (lease revenue), and has power to veto any activities deemed to be negatively impacting on farming operation.

The weaknesses of this alternative included the absence from it of provision for LGT to obtain an asset, as noted as follows:

Difficult to attract investment b/c even though projections of ROI are good, they are not assured. Asset at the end is assured. Very difficult to borrow against leasehold.

As against that suboptimal position for LGT, it was noted that this alternative would yield, for Sattler, “an asset valued at minimum of $10 million at end of 40 years”.

34 The third alternative followed the terms of the second but with the following additional provisions:

LGT has an option to purchase a 49% share of the land ($490K) in year 10. In the case of a sale, LGT has option to purchase Sattler Pastoral’s share. Any partial sale of title must be approved by both parties.

LGT has first option to purchase/lease the titles east of the cut for a golf course/ecolodge development.

Of the five alternatives, this was the only one which proposed that LGT should have an option to purchase or to lease the Lost Farm section of the Barnbougle property. No weaknesses were noted for the third alternative.

35 The fourth alternative had elements in common with the second and third. It would involve the same leasing arrangements, but without Sattler having a nominee on the Board of LGT. Sattler would pay for the installation of an irrigation system and the construction of a clubhouse “to use the depreciation on these assets as a tax deduction against Sattler Pastoral’s farming operation”. Sattler would be paid “up front” for the use of his machinery and labour. The same option to purchase a 49% share of the land to the west of The Cut as appeared in the third alternative was provided for, but payment of the $490,000 would be spread over 10 years, the outstanding balance to carry interest. No weaknesses were noted for this alternative.

36 The fifth alternative was very similar to the fourth, but it contemplated that the irrigation system and the clubhouse would be leased by LGT from Sattler. Also, the alternative had in common with the second and the third that Sattler would contribute his machinery and labour as an investment in LGT. No weaknesses were noted for this alternative. One of the benefits was said to be that Sattler would have “a much greater stake (approx 50%) in LGT, without actually much extra cost”, but it is not apparent from the document, and it was not explained in evidence, how this would come about.

37 In his evidence in the case, Ramsay referred to a number of conversations which he had with Sattler which, in one way or another, touched upon rights which he or his proposed company would have in relation to the freehold of the land upon which the Barnbougle Dunes course would be constructed and/or in relation to land for a second course. Ramsay tended to locate these conversations, in point of time, with some generality. For example, he said the following as to what transpired in the course of “several more meetings” which he had in “early January 2001” with Sattler:

I said that, as a condition of a lease of the western dunes area, the lessee would need to have an option to buy the Lost Farm for $1m so as to develop a second course on that land at a later date. Sattler said that he would grant this option if it would assist to facilitate the investment necessary to develop the first course. He said that, while the western dunes land was not for sale, he would be willing to sell the Lost Farm freehold for $1m to anyone willing to invest in making the first course happen.

Without denying any particular aspect of this version of the conversation, Sattler said (in his affidavit) that the two men “did consider” that option, but described it as “part of a preliminary discussion”. Under cross-examination, Sattler restated that his position at the time – made known to Ramsay – was that he would “consider” giving an option over Lost Farm to any person who “facilitated” the financing or (as it was put in another answer) the construction of the Barnbougle Dunes course.

38 I think it highly unlikely that, in early January 2001, Ramsay’s thinking on the subject of Lost Farm had developed to the point conveyed by the evidence set out above. The use of an option over Lost Farm as an inducement to potential investors was only one of five alternative arrangements contemplated by Ramsay in his document of May 2001. The possibility of a second course was mentioned only in passing, and very much as a thing of the future, in the business plan sent to Lucas on 7 March 2001. A later version of the business plan did contain a more fulsome treatment of the subject, but counsel for LGT invited me to draw no more favourable inference for their client than that this version existed in July 2001. I refer to that version of the business plan at paras 48-55 below.

39 Another matter which Ramsay claims to have discussed with Sattler “in early January 2001” was his proposal that, as a condition of that development, the company should be granted an option to purchase 49% of the freehold of the dunes land to the west of the river for the sum of $500,000. According to Ramsay, Sattler said that that was acceptable. Sattler agrees that this conversation was had, but denies that he said that the 49% option was “agreeable”. According to Sattler, he said merely that he would consider the matter. It transpired that when the matter was raised with Mrs Sattler, she was firmly opposed to the sale of this land, or any part of it. Again, I think it highly unlikely that, if Mrs Sattler’s attitude had been known at the time, Ramsay would have seriously included this option in his document of May 2001. It is also unlikely, it scarcely needs to be said, that Mrs Sattler would have waited from early January to May 2001 to make her views, apparently strongly-held, known to her husband and thence to Ramsay.

40 I would find on the probabilities, therefore, that it was in the context of his discussions with Sattler over the five-alternative document of May 2001 that Ramsay first, or at least first seriously, raised the land options mentioned in the third alternative. It was then that Sattler responded in the ways indicated. That Ramsay should then have been obliged to come to grips with subjects of this kind is consistent with two other developments which occurred in the weeks following: Ramsay’s early attempts to attract investors and the negotiation of a lease for Barnbougle Dunes. The terms of the lease were subsequently negotiated between the parties’ solicitors – Ramsay’s and Sattler’s. I shall return to that aspect. At this stage, I turn to Ramsay’s attempts to attract investors.

41 In June 2001, Daley introduced Ramsay to two potential investors, Paul Carter (“Carter”) and Jonathan McCleery (“McCleery”). Carter was a businessman with experience in finance and golf course development. McCleery was employed in a major bank, and had been so employed since 1988 “in marketing, credit, risk, project management and various other roles”. He had (as he put it) “a keen interest in golf”.

42 While in Melbourne over the period 3-10 July 2001, Ramsay and Sattler met with McCleery at a café at the National Gallery. McCleery recalls that he was shown a contour map of the proposed course; that Ramsay said that, apart from selling memberships, he and Sattler were looking for investors to contribute lump sums in return for equity in the development, but would not necessarily proceed both with the sale of memberships and with equity contributions if one source could provide enough money for the development of the course and the infrastructure; that Ramsay said that he and Sattler had been talking to a number of people and were hopeful of getting a syndicate of investors put together; that Ramsay said that they did not intend to borrow any funds for the development; that Ramsay said that Doak had agreed to design the course; that Ramsay said that it was going to cost about $2 million to build the course; and that Ramsay said something to the effect of “we have an amazing expansion opportunity”, and spoke about other potential golf courses at the site. In the period which followed this meeting, which McCleery described as “mid-2001”, he had further communications with Ramsay. McCleery had it in mind to make an equity investment in LGT, as well as purchasing some memberships which might then be on-sold to persons resident overseas. Although McCleery was not tested on his affidavit evidence that he intended to use his company Golf Dream Developments Pty Ltd (“GDD”) as the vehicle for any such investment and/or memberships, I note that GDD was not incorporated until 29 October 2002.

43 Ramsay also met Carter in Melbourne in early July 2001. According to his evidence, Ramsay clearly recalls that, on his way to the meeting with Carter, he telephoned Sattler and asked him “to confirm that I could tell Carter that LGT had an option to purchase the Lost Farm for $1m”. Sattler agreed that a communication on that subject occurred in the context of Ramsay then being on his way to meet Carter, but gives a different version of it. He says that he confirmed no more than what he had already told Ramsay, namely, that he would “consider giving an option to the person that facilitated the financing of Barnbougle Dunes”. I think that that was the extent of Sattler’s intentions about any option at that time, and that any communications between Sattler and Ramsay on the subject always related to the presumed attractiveness of an option over Lost Farm to third parties intending to make a substantial investment in Barnbougle Dunes. Ramsay’s meeting with Carter was an example of that, in which Sattler was permitting Ramsay to use the prospect of LGT having some involvement in Lost Farm as an attraction to be held out to Carter. I do not accept that Sattler said anything to Ramsay that would reasonably have been interpreted as conveying to him (Ramsay), as distinct from Carter, a then present, unqualified, intention to give LGT an option over Lost Farm.

44 Even if one were to accept the evidence of Ramsay, however, there is one thing that may confidently be inferred from the circumstance that he asked Sattler for permission to inform Carter that LGT had an option over Lost Farm: that there had not previously been any agreement between Ramsay and Sattler on the subject. That Ramsay would, en route to a meeting with a potentially important investor, have thought it necessary to telephone Sattler to confirm that he could tell the investor that LGT had an option over Lost Farm may be seen as inconsistent with such an option then being the subject of agreement, however informal. It is much more consistent with Ramsay wanting to be armed with Sattler’s authority to use, for marketing purposes, a prospect which was at the time a matter of discussion only.

45 As it happens, I would find that Ramsay did not communicate the prospect of any such option when he met with Carter in Melbourne in July 2001. Ramsay explained to Carter that he had a lease over a parcel of land upon which he proposed to build a golf course. He said it was a 20-year lease, with a 20-year option. Carter asked whether Ramsay would himself be putting any money into the proposed venture, and Ramsay replied that he would not be. He said that he did not have many assets, but suggested that his family might be prepared to put money into the venture. He added, however, that his father had not at that time agreed to make any such investment. Carter told Ramsay that, in his experience, there were generally only two proven ways successfully to develop a golf course: by selling memberships or by building the course in conjunction with a residential subdivision. Given that Ramsay was able to offer nothing more than a 40-year lease, Carter said that, in his view, residential subdivision was not economic. He advised Ramsay that the only remaining means of successfully developing the course was by way of the sale of memberships. By way of example, he told Ramsay that, if 300 memberships were sold at $20,000 each, a fund of $6m would be yielded. If development costs were $3.5-$4.5m, there would be a net return in the vicinity of $1.5-$2.5m.

46 In the course of this discussion, Ramsay showed Carter some aerial photographs of the Barnbougle site. Carter was taken by the natural beauty of the site. According to Carter’s affidavit, on which he was not cross-examined –

Given the large amount of land that the photographs depicted, I asked Ramsay to define the site he was seeking to develop. I did this to ascertain the scope of the overall project envisaged by Ramsay as the prospect of multiple courses would impact on the routing of the course and the central infrastructure requirements.

When this was put to Ramsay in cross-examination, he denied that there was any such inquiry by Carter. But, in a context in which Ramsay either accepted Carter’s account of other aspects of the conversation or made it clear that he had no actual recollection of them, his denials were unconvincing. They were in the nature of arguments, tending to piece together facts which he did recall to support a conclusion as to what would have been “clear” to Carter.

47 According to Carter’s affidavit –

I then asked Ramsay about the land adjacent to the land he had defined and what rights he had in respect of that other land and in particular the land upon which Lost Farm is now situated. He responded with words to the effect that “Richard Sattler the potato farmer owns it and there is nothing agreed in respect of it”.

In response to Ramsay’s evidence to which I have referred in para 43 above, Carter said:

At no stage in my initial meeting and discussions with Ramsay or subsequently did he ever say to me that he possessed any option in respect of Lost Farm. What he did say was that Richard Sattler owned the property and that nothing had been agreed in respect of any other parcel of land other than that the subject of the lease.

Under cross-examination, Ramsay disagreed with Carter on this point. He asserted that he had told Carter, at this meeting, that he held an option to purchase Lost Farm. Here again, I regard Ramsay’s evidence as being substantially a matter of reconstruction rather than recollection. He was at pains to emphasise why it should now be regarded as natural that he would have told Carter that he had the option. As mentioned above, he had a strong recollection of obtaining Sattler’s consent to pass this information on to Carter, as was, indeed, the thrust of his original evidence in his affidavit. That original evidence, however, contained no statement, in terms, as to what he actually told Carter. As mentioned above, Carter was not cross-examined, and I was not invited by counsel for LGT to reject the evidence which he gave of his meeting with Ramsay in July 2001. I accept that evidence in preference to the evidence of Ramsay.

48 Subsequent to their meeting, Ramsay sent Carter a copy of the business plan and financial projections by reference to which he was then working. Carter exhibited those documents to his affidavit in this case. Counsel for LGT submitted, and I accept, that Carter’s evidence might be used to give positive identity to the version of the Business Plan which Ramsay had developed down to July 2001 (thereby, as at that time at least, resolving the uncertainty which had previously existed as to the version of the Business Plan which existed from time to time). It is useful to set out some extracts of the Business Plan, as they reflect Ramsay’s thinking in July 2001.

49 In the “Executive Summary” of the Business Plan, the following appeared:

The author of this plan is Greg Ramsay. Greg has global experience working in the golf and tourism industries, and has an obvious passion for both. His company, Links Golf Tasmania, has been able to secure the desired land through a very attractive long term lease arrangement, saving the development over $2million in up front costs. Cost savings such as this underpin the project and have resulted in projected returns of 30%pa in the 4th year.

And:

The intention of the plan is to –

• detail the method by which Ramsay Enterprises (through Links Golf Tasmania) will develop Barnbougle Dunes as a golf destination

• generate interest among a variety of parties to become involved in Barnbougle Dunes

50 Under the heading “The Proposal” the following appeared:

The proposal is the capitalisation of Links Golf Tasmania (LGT), a partnership between Ramsay Enterprises and selected investors. Ramsay Enterprises has negotiated a 20-year lease with a 20-year option on the land at Barnbougle from its current owner Sattler Pastoral. The arrangement stipulates that there will be no lease costs incurred until the facility is operating profitably. LGT will manage the development and ongoing operation of the golf course and facilities. LGT will promote the destination in the marketplace and be responsible for the packaging of the product for sale to local, interstate and international customers.

51 A section of the Business Plan dealt with the feasibility of the Barnbougle project, discussing both “downside risk” and “upside potential”. Phase one of the venture was to be “Capital Raising and Planning Approval”. Under the heading “Capitalisation”, the following appeared:

LGT already has the following resources committed or invested:

• $1.2million parcel of land with 20-year lease and 20 year option from Sattler Pastoral.

• $1million water rights allocated to parcel of land from Sattler Pastoral

• $35 000 planning work by Ramsay Enterprises

• $300 000-500 000 design fee as equity in venture from Doak & Clayton

• $125 000 of construction machinery and labour

While planning approval is being sought, LGT is focussing upon raising the required $2.3million required in additional capital to finance the development of Barnbougle Dunes. Ramsay Enterprises has set a goal of raising approximately

• $755 000 in bank debt.

• $1.2 million in investment and Founders bonds.

• $200 000 from financial institutions as equity.

• $100 000 in development loan/grant.

This amount will be coupled with the equity committed by entities involved in the construction of the golf course.

52 In the section headed “Key Management and Staffing Strategy”, it was said that Ramsay would be the full-time project manager throughout the planning approval process. As to Sattler’s involvement, the following appeared:

It is of great benefit that Barnbougle is owned by Richard Sattler. Richard is an experienced property developer in the Tasmanian tourism industry and has embraced the concept of Barnbougle Dunes Golf Links. The arrangement between LGT and Sattler Pastoral for a 20-year lease and a 20-year option, with no lease payable until the course generates an operating profit, is one of the strengths of this proposal. Once profitable, the lease cost will be 7% of operating profits. The use of Sattler Pastoral’s machinery, expertise and labour in exchange for equity in the venture will also be a considerable up-front cost saving to the development.

53 It was said that the course would be designed by Doak, together with his Australian associate Clayton. A section of the Business Plan dealt with the subject of “Marketing Strategy”, in which the “Product” was described as “initially … a links golf course with clubhouse and practice facilities”.

54 A section of the Business Plan dealt with the subject “Stage Two Developments”. The first subheading in that section was “2nd 18 hole golf course”, under which the following appeared:

There is enough land of a very high quality available at Barnbougle to build at least 2 high quality golf courses. It is seen as highly likely and desirable for Links Golf Tasmania to build a second 18-hole course at Barnbougle Dunes. This will greatly increase Barnbougle Dunes’ capacity to attract golfers and their revenue, while decreasing the cost of operating the facility per golfer. The result will be a high return on any investment in a second course.

55 The next subheading in the section on “Stage Two Developments” was “Accommodation”, under which it was said that, if a second golf course were built, it would be likely to double the number of golfers coming to Bridport. It would, in such circumstances, be a “natural progression to provide on site accommodation in high class eco-chalets”. Regardless of whether a second golf course were built, the provision of some on-site accommodation “will be seriously considered”. Under the heading “Tournament Golf” it was said that the course would be built with tournament golf as a consideration and, as the only “true links golf course in Australia” there would be demand to utilise the course for that purpose. That would, it was anticipated, “attract tens of thousands of people” and result in a high demand for accommodation within two hours of Bridport “for at least 10 days before, during and after the tournament”.

56 In the budget projections sent by Ramsay to Carter in July 2001, the required “establishment” capitalisation was set at $3.137m. This was made up of “in kind” development equity in the amount of $900,000 and “up front cash costs” in the amount of $2.237m. The sources of the latter figure were $2m in membership bonds and $237,000 in other investments. No provision was made for any development loan or grant from the government, although some government assistance was, it seems, factored into the “in kind” equity of $900,000.

57 It is convenient next to note the progress, and the outcome, of Ramsay’s application for funding from the State government. The legislative setting for that application, and for certain other applications which are relevant in this case, was given by the Tasmanian Development Act 1983 (Tas) (“the Development Act”). Under the Development Act, Tasmanian Development and Resources (“TDR”) was a Body Corporate with the duties which included (under s 7):

… to encourage and promote the balanced economic development of Tasmania, and to ensure that its policies are directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Tasmania and that its powers under this Act or any other Act are exercised in such a manner as, in its opinion, will best contribute to –

(a) the stability of business undertakings in Tasmania;

(b) the maintenance of maximum employment in Tasmania; and

(c) the prosperity and welfare of the people of Tasmania.

Under s 9(2) of the Development Act, the powers of TDR included the following:

(b) subject to subsections (3) and (4), [to] make a loan of money to any person on such terms and conditions as TDR thinks fit so long as the principal amount of the loan, or, in the case of 2 or more loans to that person, the aggregate of the principal amount of those loans, does not exceed $1,500 000;

(c) subject to subsection (5), [to] make a grant of money for such purpose and on such terms and conditions as the Minister may approve to any person in order to –

(i) assist in the development, expansion, or retention of a business undertaking in Tasmania; or

...

(e) recommend to the Minister that he grant a loan of money as provided by section 35 ….

The operation of para (b) of s 9(2) was affected by subss (3) and (4), under which a loan of money was not to be made to a person under subs (2)(b) if the effect of making the loan would be that the total of the amounts borrowed by the borrower exceeded 80% of the value of the total available security, save where TDR was satisfied that there were special reasons for making a loan to the borrower with or without security, and with or without interest, so long as the principal of the loan did not exceed $100,000.

58 Section 35 of the Development Act, mentioned in s 9(2)(e), is also relevant in the facts of the present case, although not at this stage of the narrative. It provided as follows:

(1) Where, on an application for a loan under section 9(2)(b), TDR is of opinion that the grant of the loan would not be in accordance with the powers conferred by that section but that the grant of a loan would assist in the development, expansion, or retention of a business undertaking, TDR may recommend to the Minister that he grant a loan of money under this section.

(2) On making a recommendation under subsection (1) TDR shall refer the application for the loan to the Minister and shall provide the Minister with such additional information as it thinks fit.

(3) Where TDR makes a recommendation under subsection (1) that a loan of money be granted to a person, the Minister may, with the approval of the Treasurer and for the purposes of this Act, make a loan of money to that person, with or without security and on such terms and conditions as the Minister thinks fit.

(4) For the purposes of this section –

(a) TDR shall provide the Minister with such information as he may request; and

(b) the Minister may direct TDR to carry out such investigations, and to make recommendations to him on such questions, as he may determine.

(5) TDR shall comply with a direction given to it by the Minister under subsection (4)(b).

59 Returning to the narrative, on 17 July 2001, Peter Young (“Young”), General Manager, Manufacturing and Services within the DSD, forwarded a written proposal to the Chief Executive of the DSD which contained a recommendation that a corporate loan of $20,000 be approved to LGT under s 9(4)(a) of the Development Act. In the section headed “Company Details”, the shareholders of LGT were identified as follows:

Mr Greg Ramsay | 86 667 shares | @ | $0.75 |

Richard & Mary Ramsay | 13 333 shares | @ | $0.75 |

Mr Richard Sattler | 13 333 shares | @ | $0.75 |

These details, which could only have been provided by Ramsay, were conspicuously wrong. At the time, Ramsay himself was the holder of the only share in LGT. Under the heading “Director’s Profile”, Ramsay was identified as the director of LGT, and it was said that he had “obtained the support of the landowner Mr Richard Sattler”.

60 The proposal continued:

The original Business Plan and financial estimates prepared by Mr Ramsay were preliminary in nature and were considered unlikely to stimulate other equity participation or loan funding from a financial institution.

In recent discussions with Richard Sattler, it is now intended to fund the development by:

• selling Foundation Bonds at $5,000 each;

• provision of mechanical equipment for construction by Mr Sattler at no cost; and

• the provision of labour for part of the construction by Mr Sattler at no cost.

It was noted that Ramsay had “no demonstrated ability or experience in developing golf courses” but that he had “obtained significant support from consultants and other respected tourism operators in Tasmania”. Those consultants had “agreed to convert some or all of their fees to equity in the project”. The proposal continued:

Mr Richard Sattler who owns Barnbougle, has owned and operated successful tourism ventures in Tasmania for a number of years. Mr Sattler has undertaken to lease the land on very reasonable terms and provide other support in terms of machinery hire and water rights with an estimated value $1.0 million. However, Mr Sattler is not prepared to use the land as security for the project.

Another member of the team identified in the proposal was Risby, said to be “well respected as a consultant town planner”. He had, apparently, written in support of the project.

61 With respect to the design of the golf course, the proposal stated:

The golf course designers Renaissance Golf Design (USA company) in conjunction with Michael Clayton Golf Design (Melbourne based) are reputable designers with recognised experience in this type of project. The designers have conditionally agreed to convert their entire fees of approximately $300,000-$500,000 to equity in the project if necessary.

This passage, which also presumably came from something said by Ramsay, was also wrong at the time. Doak’s company, Renaissance Golf Design Inc (“Renaissance”), had not agreed to convert its fees to equity in the project, and Clayton never did.

62 The proposal noted that a business plan had been provided, but was “now outdated”. A later version of the business plan was being compiled, and was to be made available to DSD.

63 Annexed to the proposal was an “interest rate matrix”, as follows:

Client: Links Golf Tasmania Pty Ltd | No: |

Cost of Borrowing Rate [capped] [Q’tly] [July ‘01] | 5.20% |

Cap Premium | 0.10% |

Plus: Administrative Cost Margin | 2.00% |

Reference Indicator Rate | 7.30% |

Plus: Security Risk Factor | 2.50% |

Plus: Other Risk Factors | 2.75% |

Commercial Rate | 12.55% |

Less: Concession] | -5.25% |

Applicable Interest rate | 7.30% |

For reasons referred to in the next paragraph, interest was never paid on this loan.

64 On 14 August 2001, the DSD wrote to Ramsay, advising that LGT’s application for a loan had been approved, subject to conditions. The conditions were as follows:

Conditions Precedent

1) Documentary evidence to the satisfaction of DSD demonstrating the participation of the following individuals:

• Mr Richard Sattler, owner of Barnbougle at Bridport; and,

• Renaissance Golf Design and Michael Clayton Golf Design.

Special Conditions

1) LGT to complete a survey and mapping of the Golf Links course at the property known as Barnbougle by 31 August 2001 (unless otherwise agreed to in writing by DSD).

2) LGT having received final course plans suitable for lodgement as part of the planning application by 31 August 2001 (unless otherwise agreed to in writing by DSD).

3) LGT completing the Environment Management Plan and Planning application for lodgement with Dorset Council by 15 October 2001 (unless otherwise agreed to in writing by DSD).

4) A development application to be lodged by LGT with the Dorset Council no later than 15 October 2001 (unless agreed to in writing by DSD).

5) LGT signing formal agreements with Mr Richard Sattler for the lease of the land by 15 October 2001 (unless agreed to in writing by DSD), a copy of which is to be provided to DSD.

6) LGT to provide evidence of its best endeavours to secure finance for the construction of the golf links course and provide details of finance secured by 30 November 2001 to DSD (unless otherwise agreed to in writing by DSD).

7) Provided all the above conditions are achieved, that construction commences within six months of gaining planning approval (unless otherwise agreed to in writing by DSD).

It was provided that, if the above conditions precedent and special conditions were met, the loan might be converted to an “Assistance to Industry Grant”. That was what ultimately happened.

65 I turn next to the negotiations for a lease of the Barnbougle Dunes land to LGT. Ramsay said that he and Sattler “were able to reach an agreement as to the … key terms for a lease”. According to Ramsay, those terms included that LGT would lease the dunes to the west of the river for a rental of $50,000 pa plus 7% of the profits of the golf course, subject to a 2-year rent-free period at the outset. Sattler said only that they “spoke about” such matters. I do not need to resolve the difference in emphasis given to the content of these discussions as between the evidence of each of Sattler and Ramsay. Ramsay said that they also agreed that Sattler “would only obtain equity in LGT in accordance with the value of the equipment and labour provided by him to develop the first course”. Sattler’s response to this (in his evidence) was that he was “prepared to consider taking any contribution I made to the development of the course in equity rather than require that it be repaid”. Again, to the extent that there is a difference between the evidence of Sattler and that of Ramsay, it is one of emphasis which does not need to be resolved. Ramsay added that they agreed that Sattler “would run accommodation on the LGT land adjacent to the first course”, and Sattler was heard to express no qualification to that evidence.

66 Where the evidence of Ramsay and of Sattler parted company strongly, however, was where it touched the subject of Lost Farm. Ramsay said that they agreed that “Sattler would grant an option to LGT to buy the Lost Farm for $1 million, so as to assist LGT to facilitate interest and further investment in the first course”. Sattler did not accept that they agreed on any such thing. He said that his position at the time was that he was “giving consideration to potentially granting a first option to purchase the Lost Farm once the first course was up and running”. Under cross-examination, neither Ramsay nor Sattler deviated from his version of these early discussions. But Sattler did accept that the discussions occurred in an environment in which Ramsay was anxious to have an asset which LGT might hold out to potential investors as a benefit of putting their money into the venture, that he (Sattler) was prepared to support Ramsay in any way that was consistent with the preservation of his own interests, and that he (Sattler) was prepared to hold out, as an inducement for such investors, the prospect that the company in which they would be investing had an option over Lost Farm (the details of which were never reduced to anything like the clear terms that would be necessary for such an option to exist at law).

67 Some contemporary documentary evidence as to the scope of the discussions which Ramsay and Sattler were having in this period is to be seen in an email which Ramsay sent to his solicitor on 10 July 2001, seeking assistance with the drawing of a lease. In that email, Ramsay said:

Essentially the lease is for 20 years with a 20 year option. We have an option to buy a 50% share of the title between years 10 & 20. The lease payable is 7% of profits, with no lease incurred until profitable up until year 4 when a minimum lease p.a. kicks in based on my worst case projections. Water rights are attached to the lease. Richard has in principle agreed to build into the lease an option to purchase outright 2-3 titles on the other side of the river for later development. We have not yet fixed a price on that option, but it will be around $1mill.

The concluding two sentences of this email related, of course, to Lost Farm. Normally, a communication of this kind would be good objective evidence of the matters referred to in it. However, as will appear elsewhere in these reasons, Ramsay appears to have had a tendency to push the boundaries of established facts in communications which he made with third parties otherwise unfamiliar with such facts. I am disposed to approach his statement as to the content of Sattler’s then “in principle” agreement with some caution. As will be seen, the lease for Barnbougle Dunes, as later executed, said nothing about any option over the Lost Farm part of Sattler’s property.

68 Ramsay conferred with his solicitor on 25 July 2001. In a brief email to the solicitor on the evening of that day, Ramsay said:

Title no. 131938/2 (97hectares) is the 1st golf course (and the subject of the lease). The minor incursion is onto title no. 131940/1 (78hectares).

My option to purchase is on title no’s 130153/1 (173.1ha), 130153/2 (85.29ha) and 244898/1 (85ha).

The titles most recently referred to covered the Lost Farm area. I infer that it was some time later that the solicitor sent a draft lease to Ramsay. In evidence are several documents which relate to the process of settling the terms of the lease, but none is dated. Subject to that difficulty, those documents do throw some light on this process.

69 The draft to which I have referred in the previous paragraph was perused by Sattler and he endorsed it with some notes, upon which he was cross-examined. The draft provided that LGT, as lessee, would pay a rent of 7% of gross profits, subject to an initial 3-year rent-free period. There is also what senior counsel for LGT described as a “fragment” of a draft lease in evidence (the provenance and date of which were not stated) in which it was proposed that LGT would pay no rent in the first two years and $5,000 in the third year, with the rent thereafter consistently escalating to $70,000 in the tenth year. It seems that Sattler rejected proposals of this kind, and suggested instead that some relief for LGT from the burden of paying rent in the early years might be achieved by “capitalising” the rent payments into the equity that he would ultimately hold in LGT. Sattler also proposed that base rent should be $50,000 in the first year, rising to $100,000 in the seventh year, and should be adjusted in accordance with movements in the consumer price index thereafter. Sattler’s position, or a variant of it, is evidenced by the notes he made both on the draft lease and on the fragment referred to.

70 The draft lease made no reference to LGT holding an option, over either the land on which the course was to be built or the land known as Lost Farm. Tendered by LGT without objection, but explained neither in the evidence nor in submissions, were some undated hand-written notes, apparently made by Ramsay during the period when the lease was being negotiated. The notes were on a single page that was divided in two horizontally. On the upper part, Ramsay had noted “Richard’s points re lease”. Those points were:

• Gross profits

• 20 + 20? length of lease

• Base Rent → Base Rent capitalised → Base Rent on worst case scenario

• Base Rent $50 k + CPI

• All connections & costs for water, sewerage, power, & phone as required.

• Fence

• Water – not a “right” but to make “every reasonable endeavour” “currently estimated at”

• Lessor’s access to BB beach

• Right of first refusal

On the lower part, Ramsay had noted “My problems”. Those problems were:

• Richard never mentioned capitalising lease 1st 3 years

• Higher base rent = lower % lease

• Always understanding of 40 years golf.

• Option to buy 49%

• Option to buy neighbouring titles.

• Surrounding housing dvlpt.

• Richard connecting power?

71 I infer from the content and the context that these notes – and the preceding discussion between Ramsay and Sattler which they implied – formed the basis of a memorandum sent by Ramsay to his solicitor. That memorandum – also explained neither in the evidence nor in the submissions – was tendered by the defendants without objection. In it, Ramsay dealt with the subject of the definition of gross profits, the term of the lease, rental, connection costs for utilities, the definition of the leased land (ie whether by title or by fence), the lessor’s covenants as to water rights, Sattler’s access to the beach through the leased land, and a right of first refusal in the event that the freehold interest were sold or given away. Conspicuous by their absence from this memorandum were references to a right to buy 49% of the leased land and to an option to buy neighbouring titles, both of which were on Ramsay’s list of “problems”.

72 The memorandum referred to in the previous paragraph was undated, but the two issues mentioned at the end of that paragraph were on Ramsay’s mind in about the middle of August 2001. It was on 14 August 2001 that the relevant municipal authority granted a planning permit for the Barnbougle Dunes golf course. In evidence is an undated handwritten note from Ramsay to Sattler which commences “here is the permit Richard”. I would infer, therefore, that the note was sent shortly after 14 August 2001. The note read:

Here is the permit Richard. The other point Richard we have to finalise is my option to buy 49% of that title @ $500k – if Sally still says ‘no’ then how do we work the option on land over cut to assist me. It will be very hard to attract the Bill Hushond’s & Paul Carter’s & the like without that 49% option as I said that it was part of my lease – as we discussed. Also, we always discussed that you would connect the power – capitalised in LGT?

Under cross-examination, Sattler said that Ramsay had been persistent in his request that he, or his company, be granted an option over the Lost Farm land or, as Ramsay put it in this note, the “land over [the] cut”. Sattler maintained that his consistent position stated to Ramsay was that he would consider granting an option over that land to any person who provided the investment for the establishment of the Barnbougle Dunes course itself. He viewed this note as an attempt by Ramsay to “reinterpret” his offer; and he accepted the characterisation offered by senior counsel for LGT that he considered the note to be “manipulative” on this point (although otherwise accurate).

73 Notwithstanding what Sattler now says were his reservations about Ramsay’s note, the latter persisted on the subject of the option. He asked Sattler if he could arrange to have an option agreement prepared, and Sattler consented to that course. Ramsay then had his solicitors prepare an option deed, to which Sattler and Ramsay would be parties, and which would provide for Ramsay to have a 10-year option to buy the titles which were relevant to Lost Farm for a price of $1m. When this document was given to Sattler, he threw it in the bin. I am unsurprised that he would have done so. Although Sattler cannot now recall the details of the option, so far as I can see it was very asymmetrical in the obligations which it imposed on the parties. Aside from paying the nominal consideration of $10 and using his “best endeavours to raise any capital necessary to pay the purchase price” (ie should the option be exercised), Ramsay would fall under no obligation. Although Ramsay would have the choice to nominate any “other persons or corporations” to complete the contract upon exercise of the option, the option as such was personal to himself. There was no mention of LGT, of the Barnbougle Dunes golf course, or of provision of finance for the establishment of the course. The option was unconditional.

74 It is true that, literally, the draft option prepared on Ramsay’s instructions reflected what he now says was the position which existed as between himself and Sattler, ie, that he (Ramsay) would be given an option to buy Lost Farm for $1m. But his reason for wanting the option was to enhance the attractiveness of LGT as an investment (eg for the likes of “the Bill Husband’s and Paul Carter’s” as he put it in his note to Sattler). Some kind of relationship between the development of Barnbougle Dunes and the existence of an option over Lost Farm seems to have been central to Ramsay’s justification for the option as put to Sattler, but the document which Ramsay caused to be prepared made provision for no such relationship. Even if Sattler had it in mind to grant an option to LGT, on no view would that have been unrelated to the development of Barnbougle Dunes, whether as a matter of prospect or after the event. In the circumstances, for Sattler to have given this option – the one prepared on Ramsay’s instructions – no serious consideration would have been consistent with, and unsurprising in the light of, the terms of the document presented to him.

75 The lease was not ultimately executed until 30 November 2001. It is an important document to which I shall have to return. First, however, I should deal with Ramsay’s attempts to obtain equity finance for the construction of the Barnbougle Dunes golf course. That he should use his best endeavours to do so was one of the special conditions to which the DSD loan was subject. Following the approval of the loan, articles about the project appeared in golfing publications, and it seems that considerable publicity was generated, and that this succeeded in attracting the interest of investors.