FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 629

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | TPG INTERNET PTY LTD ACN 068 383 737 Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Respondent (“TPG”), between 25 September and 7 October 2010, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“TPA”);

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of a service, in contravention of section 53(e) of the TPA; and

(c) made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, in contravention of section 53(g) of the TPA;

by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, radio, its website, third party internet sites and in newspapers for the supply of a broadband internet service by TPG, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99 per month”, and thereby represented that a customer could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for payment of only $29.99 per month, when in fact the broadband internet service was only offered upon terms that the customer:

(d) pay to TPG a total of no less than $59.99 per month;

(e) purchase, or bundle, home telephone line rental with the broadband internet service at an additional cost of $30 per month; and

(f) pay to TPG “up front” charges of either $79.95 or $129.95 depending on the contract term.

2. TPG, between 25 September and 7 October 2010, in trade or commerce, and in connection with the supply or possible supply of a broadband internet service, contravened section 53C of the TPA by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, its website, third party internet sites and in newspapers for the supply of a broadband internet service, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99 per month” and thereby made a representation with respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of the service, but did not specify in a prominent way, the single price for the service.

3. TPG, from at least 7 October 2010 until 29 November 2011, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of:

(i) section 52 of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011;

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of a service, in contravention of:

(i) section 53(e) of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 29(1)(i) of the ACL for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011; and

(c) made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, in contravention of:

(i) section 53(g) of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 29(1)(m) of the ACL for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011;

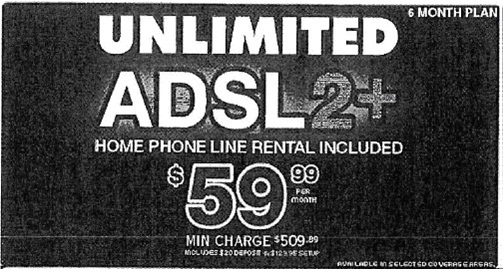

by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, radio, its website, third party internet sites, on public transport advertising space, and in newspapers, magazines, coupon booklets, and on cinema screens and indoor and outdoor billboards for the supply of a broadband internet service by TPG, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99”, and thereby represented that a customer could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for payment of $29.99 per month, when the broadband internet service was only offered upon terms that the customers:

(d) pay to TPG a total of no less than $59.99 per month; and

(e) purchase, or bundle, home telephone line rental with the broadband internet service at an additional cost of $30 per month.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

4. TPG, whether by itself, its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of the supply of ADSL2+ internet services, for a period of three years from the date of these orders, be restrained from publishing (including broadcasting, telecasting, by internet or otherwise) any advertisement containing a representation to the effect that:

(a) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at a cost of $29.99 per month (or any stated cost per month or for any other period of time being the cost for that service alone) (“the ADSL2+ monthly cost”) without obligation to acquire any additional service where such an obligation exists;

(b) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at the ADSL2+ monthly cost without the customer incurring an obligation to pay any additional monthly or periodic cost for any additional service where there is an obligation for such a service to be acquired and paid for;

(c) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at the ADSL2+ monthly cost (where that service is only offered at the ADSL2+ monthly cost on condition the customer purchase one or more additional services with it as a bundle) without also prominently stating or disclosing the cost per month (or for any other period of time) of the bundled services.

5. TPG, for a period of three years from the date of these orders, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from publishing (including broadcasting, telecasting, by internet or otherwise) any advertisement containing a representation with respect to the price payable for the supply of an internet service:

(a) per month;

(b) over the contract term; or

(c) for another period of time,

if that service is only offered at that price on condition that the customer purchase an additional service or services from TPG (“bundling condition”), without:

(a) prominently disclosing the bundling condition; and

(b) prominently stating the total price payable for all services for the relevant period referred to in the representation.

6. TPG, for a period of three years from the date of these orders, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from publishing (including broadcasting, telecasting, by internet or otherwise) any advertisement containing a representation with respect to the periodic price payable for the supply of an internet service (whether by itself or in a bundle of services), unless it also specifies in a prominent way the single price for the service (or bundle of services).

Initial advertisements - from 25 September to around 7 October 2010

7. Pursuant to section 76E(1) of the TPA, TPG pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in respect of the conduct referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2 above, in the amount of $600,000.

Amended advertisements - from 7 October 2010

8. Pursuant to section 76E(1) of the TPA and section 224(1) of the ACL, TPG pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in respect of the conduct referred to in paragraph 3 above, in the amount of $1,400,000.

9. Pursuant to sections 86C of the TPA and 246 of the ACL (alternatively sections 86D of the TPA and 247 of the ACL) TPG at its own expense:

(a) cause an advertisement in the terms and form of Annexure A to be published on Wednesday and Saturday during one week within 30 days of these orders, in the first 10 pages in each of The Australian, Daily Telegraph, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, Herald Sun and Adelaide Advertiser, the size of such advertisement being no less than 16 cm x 22 cm in each such newspaper printed in tabloid form and 22 cm x 30 cm in each such newspaper printed in broadsheet form;

(b) cause to be published on the home page of all websites controlled by TPG dealing with broadband internet plans, including at http://www.tpg.com.au, a corrective notice in the terms and form of Annexure A in no less than size 12 font, within 7 days of the date of these orders, and ensure that such notice:

(i) appears immediately upon access by a person to the home page of any such websites dealing with broadband products with or without home telephone line rental;

(ii) appears in an automatically generated pop-up window or message box whereby a member of the public is required to close the window or message box in order for it to disappear from the screen; and

(iii) is maintained on the websites for 90 days from the date of these orders;

(c) cause an advertisement in the terms and form of Annexure B to be mailed as one A4 page containing the advertisement being no less than 16 cm x 22 cm in size, within 30 days of the date of these orders, to each individual who became a customer of TPG’s Unlimited ADSL2+ broadband plan between 25 September 2010 and 31 October 2010; and

(d) cause an advertisement in the terms and form of Annexure C to be mailed as one A4 page containing the advertisement being no less than 16 cm x 22 cm in size, within 30 days of the date of these orders, to each individual who became a customer of TPG’s Unlimited ADSL2+ broadband plan between 1 November 2010 and 2 December 2011.

10. Pursuant to sections 86C of the TPA and 246 of the ACL, TPG maintain and administer at its own expense for three years from the date of this order the trade practices compliance program set out in Annexure C to the Undertaking given by TPG to the Applicant on 29 January 2009 under s 87B of the TPA (“Compliance Program”). The Compliance Program is to be amended to reflect the introduction of the Competition and Consumer Act (2010), and the changes to the legislation therein.

11. TPG pay the Applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding.

PENAL NOTICE TO RESPONDENT:

If you

(a) refuse or neglect to do any act within the time specified in this order for the doing of the act; or

(b) disobey the order by doing an act which the order requires you to abstain from doing;

you will be liable to imprisonment, sequestration of property or other punishment.

Any other person who knows of this order and does anything which helps or permits you to breach the terms of this order may be similarly punished.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A – Corrective notice for print and internet

Published by order of the Federal Court of Australia

[Insert TPG logo]

False and misleading conduct by TPG Internet Pty Ltd

The Federal Court has found that TPG Internet Pty Ltd (TPG) engaged in false and misleading conduct through its “Unlimited ADSL2+” advertising campaign.

This follows legal action by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

In September 2010, TPG launched an advertising campaign on television, radio, in newspapers and online, and later in magazines, coupon booklets and brochures, and on cinema screens, and indoor and outdoor billboards for its “Unlimited ADSL2+” broadband plan.

The advertising used by TPG prior to 7 October 2010 stated that customers could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for the cost of $29.99 per month. The Federal Court found that the advertisements failed to adequately disclose that this was only offered on condition that the customer also purchase home telephone line rental from TPG at an additional cost of $30 per month. The monthly cost of the bundled services was therefore $59.99 not $29.99.

The form of advertising before about 7 October 2010 also failed to properly disclose that an additional up front charge of $79.95 or $129.95 (depending on the contract term selected by the Customer) was payable for the services.

For further information contact TPG [INSERT CONTACT DETAILS].

Annexure B – Corrective mailout to customers who joined prior to 1 November 2010

CORRECTIVE NOTICE

Published by order of the Federal Court of Australia

[Insert TPG logo]

False and misleading conduct by TPG Internet Pty Ltd

Dear <insert salutation and surname>

The Federal Court of Australia has found that TPG Internet Pty Ltd (TPG) engaged in false and misleading conduct through its “Unlimited ADSL2+” advertising campaign. This follows legal action by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

In September 2010, TPG launched an advertising campaign on television, radio, in newspapers and online, and later in magazines, coupon booklets and brochures, and on cinema screens, and indoor and outdoor billboards for its “Unlimited ADSL2+” broadband plan.

The advertising claimed that customers could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for the cost of $29.99 per month. The Federal Court found that the advertisements failed to adequately disclose that this was only offered on condition that the customer also purchase home phone line rental from TPG at an additional cost of $30 per month. The monthly cost of the bundled services was therefore $59.99 not $29.99.

The form of advertising used by TPG before 7 October 2010 also failed to properly disclose that an additional up front charge of either $79.95 or $129.95 was payable for the services, depending on the contract term chosen by the customer.

If you would not have selected your current plan had you understood that:

* you would also have to purchase home phone line rental from TPG at the additional cost of $30 per month;

* your plan would cost you $59.99 per month rather than $29.99 per month; and

* you would be required to pay an up-front charge of $129.95,

then you can choose to cancel your TPG Unlimited ADSL2+ broadband service without incurring any cancellation fees or penalty.

If you have any questions regarding this letter, please contact [insert TPG contact details].

Yours sincerely,

<insert signature>

Annexure C – Corrective mailout to customers who joined after 1 November 2010

CORRECTIVE NOTICE

Published by order of the Federal Court of Australia

[Insert TPG logo]

False and misleading conduct by TPG Internet Pty Ltd

Dear <insert salutation and surname>

The Federal Court of Australia has found that TPG Internet Pty Ltd (TPG) engaged in false and misleading conduct through its “Unlimited ADSL2+” advertising campaign. This follows legal action by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

In September 2010, TPG launched an advertising campaign on television, radio, in newspapers and online, and later in magazines, coupon booklets and brochures, and on cinema screens, and indoor and outdoor billboards for its “Unlimited ADSL2+” broadband plan. The advertising claimed that customers could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for the cost of $29.99 per month. The Federal Court found the advertisements failed to adequately disclose that this was only offered on condition that the customer also purchase home phone line rental from TPG at an additional cost of $30 per month. The monthly cost of the bundled services was therefore $59.99 not $29.99.

If you would not have selected your current plan had you understood that:

* you would also have to purchase home phone line rental from TPG at the additional cost of $30 per month; and

* your plan would cost you $59.99 per month rather than $29.99 per month.

then you can choose to cancel your TPG Unlimited ADSL2+ broadband service without incurring any cancellation fees or penalty.

If you have any questions regarding this letter, please contact [insert TPG contact details].

Yours sincerely,

<insert signature>

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1099 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant

|

AND: | TPG INTERNET PTY LTD ACN 068 383 737 Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MURPHY J |

DATE: | 15 June 2012 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 In earlier reasons for judgment (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1254) I made findings that TPG Internet Pty Ltd had contravened trade practices laws in an advertising campaign for a broadband internet service named “Unlimited ADSL2+” (“the contravention judgment”). These reasons for judgment concern the relief I have ordered in relation to those breaches.

2 TPG used various different mediums in a broad based and far reaching national advertising campaign, which ran in two phases. The first phase advertisements were published between 25 September 2010 and about 7 October 2010 on three national television stations, seven capital city radio stations, one national and six capital city newspapers, and on the TPG and two third party websites.

3 Following a complaint by the ACCC, TPG changed the advertisements with effect from about 7 October 2010. The second phase advertisements, which were different to the first phase and require separate consideration, were published between about 7 October 2010 and 4 November 2011. These advertisements were published in an even broader campaign on a further national television station, in a wider range of national and capital city newspapers, in ethnic, community and commuter newspapers, on further third party websites, on national cinema screens, in national magazines, in coupon booklets left in letter boxes, and on indoor and outdoor billboards including on buses and trams, tram shelters, train stations and domestic airport taxi ranks and on notice boards in public washrooms.

4 I found that:

(a) the representations in each phase of the advertisements constituted misleading and deceptive conduct or conduct which is likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“TPA”) when the advertisements were published before 1 January 2011, and in breach of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) when published after that date;

(b) the representations in each phase of the advertisements also constituted false and misleading representations in relation to the price of a service in breach of s 53(e) of the TPA, and in relation to the existence of a condition in breach of s 53(g) of the TPA, when the advertisements were published before 1 January 2011, and in breach of ss 29(1)(i) and (m) of the ACL when published after that date; and

(c) the television, newspaper and internet advertisements in the first phase of the advertisements did not prominently specify the minimum total charge or “single price” of $509.89 in contravention of s 53C of the TPA.

5 The advertisements in both phases conveyed a representation that the Unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service could be acquired at a cost of $29.99 per month without obligation to acquire any additional service or pay any additional monthly charge (“the no additional service or monthly charge representation”). I found this to constitute misleading and deceptive conduct and to be a false and misleading representation, because the service is only offered by TPG at a cost of $29.99 per month with an obligation to also rent a home telephone line from TPG to be “bundled” with the broadband internet service and to pay an additional $30 per month for that rental.

6 The advertisements in the first phase also conveyed a representation that the Unlimited ADSL2+ service could be acquired at a cost of $29.99 per month without obligation to pay any up front charges (“the no set-up fee representation”). I found this to constitute misleading and deceptive conduct and to be a false and misleading representation, because the service is only offered by TPG at a cost of $29.99 per month with an obligation to also pay upfront charges comprising a set-up fee on a six month contract of $129.95 or $79.95 on an 18 month contract.

7 The first phase television, newspaper and internet advertisements also did not specify in a prominent way the single price of $509.89 for the broadband service. I found this to constitute a breach of s 53C of the TPA.

8 The ACCC now seeks various forms of relief most of which are opposed by TPG:

(a) Declarations in relation to each of the contraventions found. This is not opposed by TPG.

(b) Injunctions restraining similar conduct by TPG for five years. These are opposed. In the alternative, if injunctions are to be granted, TPG argues for a more limited form.

(c) Publication orders. A corrective notice to its customers is not opposed by TPG, but orders for corrective advertising and adverse publicity on a broader basis are. If orders are to be made, the form of the notices are agreed.

(d) A trade practices compliance program. This is not opposed but the ACCC proposes an extension of TPG’s existing program.

(e) Penalties. The ACCC submits that penalties should be imposed in the range of $4 million to $5 million. TPG accepts that penalties should be imposed, but submits that total penalties of $450,000 are appropriate.

(f) Costs. TPG accepts that it is liable to pay the ACCC’s party-party costs but contends that it should pay only 75% of those costs, and not its costs incidental to the proceeding.

9 For the reasons I set out I have made declarations in relation to each of the contraventions and ordered:

(a) injunctive relief;

(b) publication of corrective notices to TPG’s customers, and limited corrective advertising and adverse publicity;

(c) pecuniary penalties in a total of $2,000,000; and

(d) TPG to pay the ACCC’s costs, including any incidental costs, on a party-party basis.

I have not ordered any change to TPG’s existing compliance program.

Transitional arrangements

10 The title of the TPA and certain of its provisions, were amended by the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 2) 2010 (Cth) (No 103, 2010). Its short title is now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (“CCA”). The successor provisions to the Trade Practices Act 1974 are now contained in the ACL which is in Schedule 2 of the CCA. The transitional arrangements are detailed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yellow Page Marketing BV (No 2) [2011] FCA 352 at [20] to [23] (“Yellow Page Marketing”). They relevantly operate so that provisions in the same form as in the TPA prior to 1 January 2011 continue to apply after that date (except in relation to injunctive relief which is now provided for in s 232 of the ACL). Because the provisions of the TPA are interchangeable with the ACL I will usually refer only to the TPA provision rather than to its successor in the ACL.

Declarations

11 The ACCC seeks declarations that:

1. The Respondent (“TPG”), between 25 September and 7 October 2010, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“TPA”);

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of a service, in contravention of section 53(e) of the TPA; and

(c) made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, in contravention of section 53(g) of the TPA;

by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, radio, its website, third party internet sites and in newspapers for the supply of a broadband internet service by TPG, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99 per month”, and thereby represented that a customer could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for payment of only $29.99 per month, when in fact the broadband internet service was only offered upon terms that the customer:

(d) pay to TPG a total of no less than $59.99 per month;

(e) purchase, or bundle, home telephone line rental with the broadband internet service at an additional cost of $30 per month; and

(f) pay to TPG “up front” charges of either $79.95 or $129.95 depending on the contract term.

2. TPG, between 25 September and 7 October 2010, in trade or commerce, and in connection with the supply or possible supply of a broadband internet service, contravened section 53C of the TPA by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, its website, third party internet sites and in newspapers for the supply of a broadband internet service, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99 per month” and thereby made a representation with respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of the service, but did not specify in a prominent way, the single price for the service.

3. TPG, from at least 7 October 2010 until 29 November 2011, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of:

(i) section 52 of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011;

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of a service, in contravention of:

(i) section 53(e) of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 29(1)(i) of the ACL for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011; and

(c) made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, in contravention of:

(i) section 53(g) of the TPA for conduct engaged in up to 31 December 2010; and

(ii) section 29(1)(m) of the ACL for conduct engaged in from 1 January 2011;

by publishing or causing to be published advertisements on television, radio, its website, third party internet sites, on public transport advertising space, and in newspapers, magazines, coupon booklets, and on cinema screens and indoor and outdoor billboards for the supply of a broadband internet service by TPG, which contained a statement to the effect of “UNLIMITED ADSL2+$29.99”, and thereby represented that a customer could obtain an unlimited ADSL2+ broadband internet service for payment of $29.99 per month, when the broadband internet service was only offered upon terms that the customers:

(d) pay to TPG a total of no less than $59.99 per month; and

(e) purchase, or bundle, home telephone line rental with the broadband internet service at an additional cost of $30 per month.

12 The considerations relevant to the exercise of discretion under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) are not controversial. The discretion is a wide one: Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564, at 581 to 582 per Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey, and Gaudron JJ; Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (No 2) (1993) 41 FCR 89 at 97 to 98 per Sheppard J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Powerballwin.com.au Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 378 at [41] per Tracey J; and Yellow Page Marketing at [65] to [68] per Gordon J.

13 TPG does not oppose the making of declarations, provided the Court is satisfied that there is utility in doing so, and provided the declarations do not venture beyond the findings made.

14 The declarations sought by the ACCC do not venture beyond the findings made in my earlier reasons for judgment. I consider that they have utility because they:

(a) serve to clearly identify the contravening conduct;

(b) publicise the type of advertising conduct that constitutes a contravention of the TPA or the ACL in an industry where similar forms of advertising are adopted by many companies. This is particularly important with regard to the declaration relating to the requirement in s 53C of the TPA to prominently specify a total minimum charge or “single price”, as there are few decided cases on that requirement; and

(c) serve the public interest where, as in this case, the contraventions are serious, by providing a warning to businesses not to engage in misleading and deceptive conduct, not to make false or misleading representations, and not to fail to specify the single price of a service in a prominent way.

15 I will make the declarations in the form sought by the ACCC.

Injunctions

16 In reliance on s 232 of the ACL the ACCC seeks injunctions restraining TPG from engaging in contravening conduct of the kind I have found. It seeks injunctions in the following terms:

4. TPG, whether by itself, its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise, in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of the supply of ADSL2+ internet services, for a period of 5 years from the date of these orders, be restrained from making any representation to the effect that:

(a) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+internet service at a cost of $29.99 per month (or any stated cost per month or for any other period of time being the cost for that service alone) (“the ADSL2+ monthly cost”) without obligation to acquire any additional service where such an obligation exists;

(b) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at the ADSL2+ monthly cost without the customer incurring an obligation to pay any additional monthly or periodic cost for any additional service where there is an obligation for such a service to be acquired and paid for;

(c) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at the ADSL2+ monthly cost without the customer incurring an obligation to pay any upfront charges where upfront charges are obliged to be paid;

(d) it would supply an unlimited ADSL2+ internet service at the ADSL2+ monthly cost (where that service is only offered at the ADSL2+ monthly cost on condition the customer purchase one or more additional services with it as a bundle) without also stating or disclosing the cost per month (or for any other period of time) of the bundled services (“the ADSL2+ bundled services monthly cost”) in such a way as to give the ADSL2+ bundled services monthly cost equal prominence with the ADSL2+ monthly cost.

5. TPG, for a period of five years from the date of these orders, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from making a representation with respect to the price payable for the supply of an internet service:

(a) per month;

(b) over the contract term; or

(c) for another period of time,

if that service is only offered at that price on condition that the customer purchase another service or services from TPG (“bundling condition”), without

(d) prominently disclosing the bundling condition;

(e) stating with equal or greater prominence the total price payable for all services for the relevant period referred to in the representation; and

(f) prominently disclosing any additional up front costs that are payable.

6. TPG, for a period of five years from the date of these orders, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from making a representation with respect to the periodic price payable for the supply of an internet service (whether by itself or in a bundle of services), unless it also specifies in a prominent way the single price for the service (or bundle of services).

Is injunctive relief appropriate in the circumstances

17 Section 232 of the ACL provides broad powers to the Court subject to at least three limitations:

(a) the relief should be designed to prevent a repetition of the contravening conduct;

(b) there must be a sufficient nexus or relationship between the contravention and the injunction; and

(c) the injunction must relate to the case or controversy: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Z-Tek Computer Pty Ltd (1997) 78 FCR 197 at 203 to 204.

18 The Court must also consider whether an injunction is appropriate as a matter of discretion. Relevant factors include matters such as:

(a) whether the TPA needs to be supplemented by the availability of sanctions applicable to contempt of court;

(b) the contraventions found;

(c) the risk of similar contraventions in the future and the utility of an injunction in minimising that risk;

(d) whether the conduct was intended, isolated and/or occurred many years before the enforcement proceedings;

(e) the clarity and specificity of the injunction; and

(f) the intended methods of enforcement of the injunction.

See BMW Australia Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2004] FCAFC 167 (“BMW Australia”) at [35] to [39]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (2007) 161 FCR 513 (“Dataline”) at [108], and [110] to [114]; and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265 (“Leahy Petroleum (No 3)”) at [119] to [125].

19 In ACCC prosecutions for breach of the TPA, applications for injunctive relief are so common as to appear to be standard form. However, the ACCC is not entitled to injunctive relief merely as a vindication of its success in establishing the contraventions. While s 232(4) of the ACL provides that it is unnecessary to show that repetition of the contravening conduct is threatened or apprehended for a grant of injunctive relief, the authorities are clear that an injunction should not be granted unless it will serve a legitimate purpose: Dataline at [107] to [111] per Moore, Dowsett and Greenwood JJ.

20 In TPG’s submission there is no utility in granting injunctions as it contends there is no basis upon which the Court should conclude that there is any prospect that the contravening conduct will be repeated. It argues that its conduct does not warrant injunctive relief given that it did not oppose the granting of declarations, and has replaced the second phase advertisements with new advertisements which have not been found to contravene the law.

21 In BMW Australia at [39] Gray, Goldberg and Weinberg JJ explained:

The purpose of granting an injunction to restrain conduct already prohibited by legislation can only be to add to whatever consequences the legislation attaches to that conduct the additional consequences of a possible finding of contempt of court by failure to comply with an injunction. In each case, it is a question whether the conduct concerned warrants the application of those more stringent consequences.

22 I accept that an injunction that operates to restrain certain conduct may add little when a statute prohibits that conduct in any event. Further, given that Parliament has not provided for imprisonment in connection with a contravention it may not be appropriate for the Court to injunct conduct simply in order to create the possibility of imprisonment: see Dataline at [110].

23 However, an injunction is appropriate in this case to restrain repetition of the contravening conduct. The conduct was seriously misleading and affected a diverse and widespread class of users and potential users of broadband internet services. It is significant in terms of the utility of the injunctions that TPG continues to be an active supplier and advertiser of a range of broadband internet services.

24 Of importance to my decision that injunctions are appropriate is the fact that the contraventions occurred after TPG had given an enforceable undertaking to the ACCC with effect from 6 February 2009, pursuant to s 87B of the TPA (“the Undertaking”). TPG gave the Undertaking upon the ACCC raising a complaint in relation to advertisements for its "Unlimited Cap Saver" mobile telephone plan. The complaint related to the exclusion of some calls and text messages from the purportedly unlimited plan and to inadequate specification of an obligation to purchase a SIM card in order to subscribe to the plan. It relevantly provided:

19 TPG undertakes to the ACCC for the purposes of section 87B of the TPA that for a period of three years it will not, in trade or commerce, in the course of carrying on the TPG Business:

a. engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive;

…

d. in connexion with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connexion with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services;

e. publish, in any manner whatsoever, an advertisement for a mobile telephone plan which states that for a specified price there will be unlimited calls and text when:

(i) certain calls and text are excluded from the mobile telephone plan; or

(ii) additional charges will apply for some calls and text;

where the advertisement does not include an appropriately prominent disclaimer to the effect that exceptions, terms and conditions apply to the mobile telephone plan.

…

22 TPG undertakes to the ACCC for the purposes of section 87B of the TPA that it will:

a. Within two months of the date of this Undertaking coming into effect, establish and implement a trade practices compliance program in accordance with the requirements set out in "Annexure C" for the directors, officers, employees or other persons involved in TPG’s business, being a program designed to minimise TPG’s risk of future breaches of sections 52 and 53 of the TPA and to ensure awareness of its responsibilities and obligations in relation to the requirements of sections 52 and 53 of the TPA; …

25 It is clear that by engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct and by making false and misleading representations with respect to price in breach of ss 52 and 53 of the TPA, TPG is in breach of the Undertaking.

26 It is also plain that there are important similarities between the conduct giving rise to the Undertaking and the contravening conduct in this case. First, the "Unlimited Cap Saver” mobile telephone plan was also a broad based campaign aimed at ordinary consumers, and the advertisements were published using diverse media. Second, while the advertisements giving rise to the Undertaking related to a mobile telephone plan they had a very similar deficiency to the contravening advertisements in this case. They also contained a dominant message that the service could be purchased for a specified monthly price per month even though it was only available at that price if the consumer also made another purchase (in that case a SIM card).

27 TPG’s breach of its Undertaking, by engaging in essentially the same type of misconduct again, indicates an increased risk of it repeating the contravening conduct.

28 It is also relevant that, while TPG changed the first phase advertisements in response to the ACCC complaint of 4 October 2010, the contravening dominant message was left unchanged. The second phase advertisements ignored the thrust of the ACCC complaint and continued to strongly emphasise the component price of $29.99, and to de-emphasise the actual price of $59.99 and the requirement to also rent a home telephone line. That it made a choice in doing so is plain if one reviews the draft second phase print advertisement (which clearly sets out the $59.99 monthly price) that was considered and rejected by TPG in December 2010 (Annexure 1). This draft can be compared to the second phase print advertisement it decided to run for the next 11 months (Annexure 2).

29 For these reasons I do not accept that the risk of repetition of similar conduct by TPG is as low as it contends. A grant of properly framed injunctive relief is appropriate in the circumstances.

No injunction relating to failure to disclose the set-up fee

30 The no set-up fee contravention occurred only in the first phase advertisements. In the second phase advertisements, while information as to the set-up fee tended to be in small print (and absent from the radio advertisement), I found the advice was sufficient because the ordinary or reasonable consumer was alert to the possibility of such fees.

31 I accept TPG’s submission that the Court ought not grant proposed injunctions 4(c) and 5(f) which relate to up-front charges. The relevant contravening conduct in failing to adequately disclose the set-up fee occurred more than a year and a half ago, and that campaign only ran over a period of ten to thirteen days, ceasing promptly upon concerns being raised by the ACCC. There is no utility in this injunction.

The scope of the injunctions

32 TPG submits, and I agree, that if an injunction is to be granted it should be made only in respect of conduct TPG is found to have engaged in, that is, upon the case proved against it: Commodore Business Machines Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1990) 92 ALR 563 at 574 per Gummow, Foster and Hill JJ; approved in ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 (“ICI v TPC”) at 259 to 260 per Lockhart, Gummow and French JJ.

Should the injunctions relate only to advertisements or to broader conduct

33 The ACCC proposes injunctions which go further than restraining only TPG’s conduct in its advertisements. In proposed injunction 4 the ACCC seeks injunctions relating to conduct “in connection with the supply or possible supply of, or the promotion by any means of the supply” of ADSL2+ internet services. In proposed injunctions 5 and 6 the ACCC seeks to restrain any “representation with respect to” the price (including periodic price) payable for supply of an internet service, which injunctions are not limited as to the circumstances in which the representation is made.

34 Notwithstanding that the contraventions in this case occurred in advertising rather than in other conduct, the ACCC says that the broad scope of these injunctions is appropriate. It argues that the words used in proposed injunction 4 are the opening words of s 53 of the TPA and that the proposed injunctions merely reflect the Act. It contends that the injunctions should apply to broader conduct than advertising because if limited to advertising conduct only, they will be less useful in reducing the risk of TPG again acting in a misleading and deceptive manner. In particular it points to the possibility of TPG’s telephone call centre representatives making misleading representations and it argues that it is important that the injunctions also cover any representations they might make.

35 I do not accept the ACCC’s submissions in this regard. The representations that were the subject of this proceeding occurred in identified advertisements. Its case was not based on broader conduct in the supply or possible supply of internet services, or in representations made outside of TPG’s advertisements. In particular, there was no evidence of any false or misleading representations by TPG’s telephone call centre representatives. I consider that any injunctions granted should relate only to the advertising conduct: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1200 (“Singtel Optus (No 2)”) at [3] to [4] per Perram J.

Should the injunctions relate only to the bundled ADSL2+ internet service

36 TPG argues that any injunctions granted should be restricted to advertising of bundled plans for the provision of ADSL2+ and a telephone line. It argues that this was the contravening conduct and that the injunction should not relate to all TPG’s bundled internet services as sought by the ACCC.

37 TPG relies on Singtel Optus No 2 at [4] in which Perram J declined the ACCC’s request for injunctions relating to broadband services generally when the contravening conduct related only to broadband plans. However, his Honour’s decision to limit the injunctions in that matter was based on quite different facts to this case. In that case the significant difference between a broadband plan and broadband services generally led his Honour to consider it unlikely that the impugned conduct could occur outside of broadband plans. In the present case the ADSL2+ service is a subset of (rather than completely different to) the internet services that the ACCC seeks to enjoin, and the impugned conduct could occur in TPG's advertisements for any of its bundled internet services.

38 An injunction limited as TPG contends would have less utility than the broad injunctions proposed by the ACCC. The real risk to be addressed is not that TPG will republish the same contravening advertisements, but rather that it will commit similar contravening conduct, such as not adequately disclosing that an internet service cannot be purchased at the advertised price unless another service is also purchased, and another charge met.

39 Further, in a field of enterprise as rapidly developing as internet services it is inappropriate to limit the injunctions granted to the particular internet service which was the subject of the contravening advertisements. While the bundled ADSL2+ service is presently popular with consumers, it may soon be out of date or unpopular, and the utility of the injunctions may soon be lost if they are limited as TPG seeks. The injunctive relief should relate to the bundled internet services offered by TPG, rather than being restricted only to the bundled ADSL2+ service.

The proposed requirement for “prominence” in the injunctions sought

40 The ACCC’s proposed injunctions 5(d) and 6 seek to impose a requirement that TPG’s representations "prominently" disclose the bundling condition and the single price of the services for the term of the contract. Its proposed injunctions 4(d) and 5(e) seek to impose a requirement that TPG’s representations as to the bundled monthly (or other periodic) price of ADSL2+ or other internet services are disclosed with "equal prominence" or "equal or greater prominence" to the headline monthly (or other periodic) price.

41 TPG argues, and I accept, that prominence involves a subjective analysis of the relevant advertisements. The test for prominence of part of an advertisement is whether that part stands out so as to be likely to be noticed by the viewer. The purpose of the injunctions proposed by the ACCC is to ensure that particular qualifying information stands out in the advertisement so as to be seen.

42 Assessing whether a particular part of an advertisement stands out requires a comparison of the different parts of the advertisement. This may sometimes be as simple as considering the comparative size and colour of the fonts used in a print advertisement, or considering the comparative length of broadcast time given to particular parts of a television or radio advertisement. Other times, as in some of the contravening advertisements, it may require consideration as to whether the use of advertising techniques to catch the viewer’s eye, the use of particular graphics or moving images against other static words or graphics, or the use of different voices or different ways of speaking, operate to make a particular part of an advertisement prominent. The likely circumstances in which the advertisement is read, viewed, or heard can also affect the prominence for a viewer of one part of an advertisement as against another.

43 TPG did not argue that it did not understand what “prominent” means. However, it says that the application of any requirement for prominence is difficult as it is a matter about which reasonable minds can differ. It argues that what is prominent may be obvious to one person but not to another. In that regard it points to the fact that it took legal advice about the operation of s 53C in relation to its advertisements, and bona fide considered that it had prominently specified the single price. In its submission the subjectivity of any requirement for prominence renders it inappropriate to grant the injunctive relief sought, as it will mean that it is forced to make a judgment call in its future advertisements, attended by the risk of sanction for contempt of court.

44 I do not accept that the level of subjectivity involved in determining whether qualifying information is prominent means that the injunctions ought not be granted. As I noted at [125] of the contravention judgment, the ordinary meaning of the word "prominent" is clear, meaning to stand out so as to "strike the attention", "be conspicuous", "be easily seen" or "be very noticeable". I found that it has that meaning in s 53C of the TPA. There is nothing in the proposed injunctions which would require that the word have anything other than its natural meaning.

45 In Singtel Optus (No 2) at [6] Perram J ordered injunctions that required future advertisements in that case to "clearly and prominently" display the relevant qualifications. Although this required subjective analysis by the respondent, Perram J must have apprehended no real difficulty for the respondent in applying that requirement, and did not consider the requirement too imprecise in effect. His Honour considered that the requirement for a clear and prominent display of the qualifying information was necessary to ensure that consumers were informed of the correct position. I have the same view.

46 It is significant that s 53C of the TPA provides that the single price for a service or bundle of services must be specified "in a prominent way". There are significant civil penalties for its breach. This indicates that Parliament considered it within the capacity of Australian corporations to determine whether the single price of a service in an advertisement is prominently specified or not.

47 I note too that clause 19 of the Undertaking given by TPG to the ACCC provided that it would not advertise unlimited mobile telephone calls and texts unless it included an "appropriately prominent disclaimer". It appears that TPG did not then doubt its ability to determine whether any disclaimer it made in an advertisement is prominent.

48 In September 2009 TPG received a letter from the ACCC attaching a copy of an enforceable undertaking pursuant to s 87B entered into by Telstra, Optus and Vodafone Hutchinson. In this undertaking each of these major telecommunication companies agreed, amongst other things, not to advertise a periodic price of a service without also stating in a prominent way the single price of the service. These industry leaders also appear to have accepted that they could determine whether particular information in an advertisement is prominent.

49 TPG’s contention that the requirement for "prominent" disclosure of any qualification makes the proposed injunctions too subjective or too imprecise must be rejected. Injunctions are appropriate to require that TPG’s advertising:

(a) prominently disclose the monthly (or other periodic) price of the bundled Unlimited ADSL2+ service, or other bundled internet service (as per proposed injunctions 4(d) and 5(e));

(b) prominently disclose the bundling condition (as per proposed injunction 5(d)); and

(c) prominently specify the single price for the bundled services (as per proposed injunction 6).

50 However, I have a different view in relation to proposed injunctions 4(d) and 5(e) insofar as they seek to impose a requirement of "equal" or "equal or greater" prominence to any qualification. The ACCC argues that these requirements are one way of ensuring that TPG knows how much prominence to give the qualifying information. It contends that injunctions in this form are a good answer to TPG’s argument that it cannot determine whether a particular part of its advertisements is prominent or not, as it will give TPG greater clarity. It also argues that equal or greater prominence of qualifying information will give greater clarity for consumers.

51 I accept that the requirement for equal or greater prominence will give more clarity to consumers, but there is nothing in the TPA that requires that TPG’s advertisements meet such a requirement. Subsections 53C(4) and (5) of the TPA indicate that the single price need not be of equal prominence in circumstances such as in this case, and ss 52 and 53(e) and (g) require only that TPG not make false or misleading representations. These provisions do not support an overarching requirement that qualifying information have equal or greater prominence to the dominant message.

52 While the Court has the power to craft an injunction more broadly than the terms of the statute, I decline to enjoin conduct not prohibited by the TPA in the circumstances of this case. Injunctions in these terms could leave TPG in the unsatisfactory position that future advertisements which provide qualifying information prominently and in compliance with the TPA - although with less than equal prominence - still result in it being in contempt of court. Accordingly, I have redrafted the injunctions to remove the requirement for equal or greater prominence. It is enough that the injunctions require that the qualifying information is prominent.

The duration of the injunctions

53 The ACCC argues for injunctions of five years duration, in part because it says that more is needed to deter TPG from repetition of its contravening conduct. TPG submits that any injunction made should be for no longer than three years. In the circumstances of this case and taking into account the other orders made, I consider that injunctions for three years duration are sufficient.

54 With the changes I have indicated the injunctions made strike an appropriate balance between the contravening conduct found and the risk of repetition by TPG of similar conduct. They are clearly expressed, can be readily obeyed and do not require court supervision.

Pecuniary Penalties

55 Section 76E of the TPA (and s 224 of the ACL) empowers the Court to order a person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty as the Court determines appropriate for each contravention of s 53 or its successor provision. By s 76E(3) (and s 224(3) of the ACL) the maximum penalty for each act or omission by a body corporate is presently $1.1 million.

56 Pecuniary penalties are sought by the ACCC in relation to each false or misleading representation made by TPG in the first phase and in the second phase advertising campaign with respect to:

(a) the price of a service pursuant to s 53(e) or its successor; and

(b) the existence or effect of a condition pursuant to s 53(g) or its successor.

57 The ACCC contends that a penalty in the range of $4 million to $5 million by reference to nine separate courses of conduct is appropriate. TPG says that the Court should impose a penalty of only $450,000 by reference to three courses of conduct.

Relevant factors to take into account

58 Section 76E provides that in determining the appropriate penalty the Court must have regard to “all relevant matters”. It sets out some mandatory but not exclusive criteria which the Court must take into account. The mandatory factors are:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(b) any loss or damage suffered;

(c) the circumstances in which the contravening conduct took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by the Court to have engaged in any similar conduct.

59 It is uncontroversial that in having regard to all relevant matters under s 76E the factors relevant to the imposition of a civil penalty under the former s 76 of the TPA for contraventions of Part IV of the TPA are applicable: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Global One Mobile Entertainment Ltd [2011] FCA 393 (“Global One”) at [110] to [112] per Bennett J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 382 at [68] to [69] per Perram J.

60 The principles for assessment of penalty under s 76 were summarised by French J (as he then was) in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd (1991) ATPR 41-076 (“TPC v CSR”) at 52,152-53 and expanded on by the Full Court of the Federal Court in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (“NW Frozen Foods”) per Burchett, Kiefel JJ and Carr JJ, and J McPhee and Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365 (“J McPhee & Son”). These principles were uncontroversial between the parties.

61 Numbered so that they follow consecutively from the mandatory factors, these factors include the following:

(e) the size of the contravening company;

(f) the deliberateness of the contravention and period over which it extended;

(g) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at a lower level;

(h) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the TPA, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(i) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for enforcement of the TPA;

(j) the financial position of the contravener;

(k) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert; and

(l) the contravener’s position of influence and importance in its industry sector.

62 I have not included in this list several factors referred to in the authorities relating to the degree of market power of the contravener, and the effect of the contravening conduct on the functioning of the market and other economic effects: see TPC v CSR Ltd at 52,153; NW Frozen Foods at 290. I do not consider that Part V of the TPA is substantially concerned with matters of that kind, and in any event those factors have no relevance to this case.

Deterrence

63 The relevant factors must be gauged by reference to the principal object of a civil penalty under s 76E which is deterrence, both specific to TPG and in general to others who might be tempted to contravene the TPA. In TPC v CSR at 52,152 French J stated:

The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

64 In NW Frozen Foods at 294-295 the Full Court explained:

The Court should not leave room for any impression of weakness in its resolve to impose penalties sufficient to ensure the deterrence, not only of the parties actually before it, but also of others who might be tempted to think that contravention would pay, and detection lead merely to a compliance program for the future.

65 Similar sentiments were expressed by Finkelstein J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd [2001] FCA 383 at [13] where his Honour said:

For a penalty to have the desired effect, it must be imposed on a meaningful level… the penalty must be at a level that a potentially offending corporation will see as eliminating any prospect of gain.

See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v McMahon Services Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1425 at [14] to [15] per Selway J, quoted with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Ltd [2008] FCA 1976 at [21] per Lindgren J.

66 Recently, in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20 (“Singtel Optus 2012”) at [62] to [63] the Full Court per Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ explained:

There may be room for debate as to the proper place of deterrence in the punishment of some kinds of offences, such as crimes of passion; but in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business.

…

Generally speaking, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.

At [68], the Court held that:

The Court must fashion the penalty which makes it clear to [the contravenor], and to the market, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of the Act cannot be regarded as [an] acceptable cost of doing business.

67 The penalty should be set sufficiently high that a business, acting rationally and in its own best interest, will not be prepared to treat the risk of such a penalty as a business cost. It is however necessary to keep in mind that in seeking to deter, a penalty must not be set so high as to be oppressive: Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chainsaws (Aust) Pty Ltd (1978) ATPR 40-091 at 17,896; NW Frozen Foods at 293; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum (No 2) [2005] FCA 254 at [9].

68 TPG contends that specific deterrence is not a substantial factor in this matter because it says that it has cooperated with the ACCC, and its contravening conduct arose from a misjudgement rather than any failure by it to take the issue sufficiently seriously: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761 (“Singtel Optus (No 4)”) at [67].

69 I do not accept this. Its conduct was seriously misleading. It involved a deliberate marketing strategy to strongly emphasise the $59.99 component of the monthly price and de-emphasise the real price of $59.99 with the requirement to purchase another service. The qualifying information was minimised by clever marketing stratagems. As I have said, TPG’s behaviour indicates that there is a risk of repetition of similar conduct by it. Specific deterrence is a significant factor in my assessment of the appropriate pecuniary penalty in this case. In my view it needs to be a penalty that is sizeable for TPG.

70 TPG also contends that general deterrence is achieved in the present case by the making the declarations and other orders such as corrective notices. I do not accept this submission. Even though the other declarations and orders I make will also assist general deterrence, in my view a sizeable penalty is required to deter other telecommunications and internet companies from similar conduct to TPG.

The classes of contravention

71 Section 76E(1) of the TPA refers to the imposition of a penalty "in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies". Section 76E(4) provides that a person is not liable for more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of “the same conduct”. It is uncontroversial that I should not treat each publication of a contravening advertisement separately for the purposes of penalty. Both parties propose that the contraventions be grouped into classes representing separate courses of conduct. This is appropriate where the episodes of publication are sufficiently similar to be treated as a separate course of conduct. Having regard to both any similarities and dissimilarities the question is how many separate courses of conduct exist.

72 TPG submits that for the purpose of assessing penalty it has committed only three classes of contravention, by reference to three kinds of non-disclosure as follows:

(a) misleading conduct in making the no additional service or monthly charge representation in the first and second phase advertisements;

(b) misleading conduct in making the no set-up fee representation in the first phase advertisements; and

(c) failing to specify the single price or minimum charge in the first phase advertisements.

It says that the maximum penalty which could be awarded is therefore $3.3 million.

73 However, the ACCC submits, and I agree, that the contravention should be grouped into nine classes of contravention on the basis that each of the four different types of advertisement in the first phase of the campaign should be treated as a separate course of conduct, as should each of the five different types of advertisements in the second phase.

74 Although it argues for nine classes of contravention, the ACCC submits that another way of classifying the contraventions in the advertisements, expressed in a chart form, is as follows:

Non- disclosure | Media | Number of Contraventions |

First phase - no additional service or monthly charge | Television, radio, internet and print | 4 |

First phase - no set-up fee | Television, radio, internet and print | 4 |

First phase - not prominently specifying the single price | Television, internet and print | 3 |

Second phase - no additional service or monthly charge | Television, radio, internet, print and billboard | 5 |

Total | 16 |

75 TPG’s submission that there are only three classes of contravention must be rejected as paying insufficient regard to the differences between the phases of the campaign and differences in the duration, reach and effect of the different kinds of advertisements. Grouping the contraventions into the nine classes proposed by the ACCC is a better approach.

76 This is so because, first, the advertisements from the two phases of the campaign cannot be grouped together into a course of conduct as proposed by TPG. The differences in the conduct between the first and second phase advertisements are significant, including that:

(a) each of the first phase advertisements contain the no additional service and monthly charge representation and the no set-up fee representation, as well as breaching s 53C. The second phase advertisements contain only the first representation referred to.

(b) the disproportion between the dominant message and the qualifying information was greater in each of the first phase advertisements than in the second phase advertisements.

(c) the duration of the first phase advertisements was short, being published for only 10 to 13 days, while the second phase advertisements were published for about 12 months. Many more consumers were likely affected by the second phase advertisements.

(d) the second phase advertisements were published through many additional forms of media and likely affected many further consumers as a result.

77 Second, there were significant differences in the advertisements within each phase of the campaign. These also require a different approach to that urged by TPG including:

(a) each advertisement in the first phase breached four different provisions of the TPA, namely ss 52, 53(e), 53(g) and 53C. Three of those contraventions are sufficiently different that they should not be grouped together, requiring separate treatment as they do.

(b) The various mediums of publication each operated differently in their tendency to mislead. While there was overlap, each type of advertisement had a different effect and should be treated differently. I dealt with some of these differences in the contravention judgment. A similar approach to the different forms of advertisement was taken by Perram J in Singtel Optus (No 4).

(c) Although there was overlap, the advertisements using different mediums were likely to have been seen by broadly different audiences. For example, the audience for newspaper advertisements compared to that for internet advertisements.

(d) The duration, intensity (in terms of frequency) or extent of the publication of advertisements varied significantly depending on the different forms of media used, leading to likely differences in effect on the audience.

78 In short, I regard each of the advertisements in each broad medium in the two different phases of the campaign as sufficiently distinct to constitute a separate contravention, - a total of nine contraventions for penalty purposes. This approach is consistent with authority: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra (2010) 188 FCR at [231] to [235] per Middleton J; Trade Practices Commission v Bata Shoe Company of Australia Pty Ltd [1980] ATPR 40-161 at 42,277 per Lockhart J. It is important to keep in mind that the totality principle operates to remove the effect of any contravention based arithmetic.

The nature and extent of the contravening conduct

79 TPG accepts that its contravening advertising campaign was substantial. It was a mass reach campaign involving many different forms of media, including national television stations, capital city radio stations, a wide variety of newspapers (including national, capital city, ethnic, community and commuter), its own internet site as well as others, national cinema screens, national magazines, coupon booklets dropped into mailboxes and billboards (on the sides of buses, trams, tram shelters, train stations and at domestic airport taxi ranks). It ran at a cost estimated by TPG to be $8.9 million.

80 The campaign was conducted over a substantial period. While the first phase of the campaign only ran for 10 to 13 days, the second phase (in which the range of advertising media was significantly increased) ran from about 7 October 2010 to 4 November 2011.

81 In seeking to distinguish its conduct from that of the respondent in Singtel Optus (No 4), TPG argues that its campaign cannot be compared to what it says was the more extensive campaign in that case. The campaign in that matter involved three different television advertisements, one print advertisement, two colour flyers, one billboard, one type of on-line advertisement and three of another type, each of which advertisements Perram J treated as sufficiently different to be a separate course of conduct. The advertisements were shown a total of 15,405 times over a period of between seven and thirteen weeks.

82 I do not accept TPG's contention that its campaign is not comparable with the campaign in Singtel Optus (No 4). It was a mass reach campaign using multiple advertising mediums to reach a very broad class of consumers, in fact using more mediums than Singtel Optus did. It appears that Singtel Optus’ campaign may have been more intensive but TPG’s campaign ran for much longer. The Court was not informed how many times TPG’s television and radio advertisements were broadcast but they ran for about 12 months. TPG was unable to supply details of the size of the audience who viewed or heard these advertisements. TPG conceded that the campaign would have been seen by "hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people." It appears that TPG’s campaign was of a medium intensity but longer duration . This may well mean that it is likely to have left a more enduring impression than the short more intensive Singtel Optus campaign: Singtel Optus (No 2) at [5].

83 I infer from the width and duration of the campaign, and the fact that TPG spent $8.9 million on it, that it was intended to have a substantial impact on consumers. From this intention I more readily conclude that the campaign had the intended substantial effect. Customers to TPG’s broadband internet offerings grew from 9000 to 107,000 during the campaign in the 2011 financial year: see Campomar Sociedad Limitdada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [33]. On any view the campaign was very successful.

84 I have already set out my view as to the seriously misleading nature of TPG’s conduct and its duration.

Any loss or damage suffered

85 The ACCC did not adduce any evidence of loss or damage by consumers and there was no quantification of any loss that might have been suffered.

86 There is no evidence of any complaint by a consumer to the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman. Also, even though there were a very large number of new subscribers to ADSL2+ in the relevant period, the consumer complaints can be counted on one hand. While I do not have confidence that there are not more complaints to TPG (as it did not keep complaint records that allowed the isolation of complaints related only to the advertisements) the searches that have been conducted enable me to infer that the complaint level was low.

87 I do not accept TPG's contention that the few complaints found are unrelated to the contravening advertisements, as in my view the relationship is clear. In December 2010 Mr McFadyen complained that he believed that he had signed up to a bundled ADSL2+ service with a home telephone line for $29.99 per month (although there is some dispute as to whether his complaint relates to the advertisements or to a conversation with a TPG call centre representative). In February 2011 Mrs Gomez similarly complained that she understood that the service was $29.99 per month plus $1 per month for the telephone line rental. Potential customers, Mr Boctor, Ms Murdoch and Mr Leonard (and existing customer Ms Yang) also appeared to be misled as to the monthly price of Unlimited ADSL2+.

88 TPG contends that I should infer that no loss or damage was actually suffered by any person by reason of the conduct. I do not accept this as although the evidence of consumer complaint is low, this says nothing about the loss and damage suffered by TPG's industry competitors. TPG’s 2011 Annual Report and 2011 Full Year Results presentation shows that in the period of the advertising campaign the subscribers to TPG's broadband internet services grew from 9000 in July 2010 to 107,000 people by July 2011. The Unlimited ADSL2+ service was an important part of the broadband internet services offered by TPG. In the same period TPG’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (“EBITDA”) increased by 37% and there was a 40% increase in the group's net profit after tax.

89 In a letter to shareholders on 20 September 2011 the Executive Chairman of TPG advised that TPG's "broadband and home phone bundle has continued to be the major growth driver, adding 98,000 subscribers during the year".

90 It is clear from the magnitude of the growth in subscriber numbers that potential customers were attracted to the Unlimited ADSL2+ service. The evidence indicates that advertising contributed significantly to TPG’s sales, and it did not submit to the contrary. It described its advertisements as a “call to action” which can only have been a call to entice consumers to purchase its service. I infer that some of this consumer traffic must have been away from TPG’s competitors.

91 I accept however that the significant growth in subscriber numbers (and resultant revenue) can be in part attributed to the attractiveness of the service itself rather than to the contravening advertisements. It is impossible to now unscramble how many of the sales of Unlimited ADSL2+ arose simply because it gave consumers what they were looking for in terms of price and download capacity. I am satisfied that the advertisements played an important part. Apart from everything else, I infer that TPG would not have continued with its advertising campaign for 12 months (upon which it ultimately spent $8.9 million) unless it found it effective.

92 The contravening advertisements are therefore likely to have reduced the sales made by TPG’s competitors. The evidence is that revenue of $59.3 million was generated by TPG from sales of Unlimited ADSL2+ in the period from 25 September 2010 to 7 November 2011. Although I cannot quantify it, it is likely that TPG’s competitors have been caused some material loss and damage. The fact that it has done so weighs against it and is of significance in the assessment of penalty.

The circumstances in which the contravening conduct took place

93 TPG submits that the first phase advertising campaign took place after it had been approved by its General Counsel and by its General Manager of Consumer Products, Marketing and Sales. Its evidence is that before approving the advertisements these senior employees considered the trade practices implications. TPG also submits that upon being advised of the ACCC’s concerns about the first phase advertisements, it promptly took steps to address those concerns by their withdrawal and replacement with with the second phase. It says that the second phase advertisements were partly successful in addressing the ACCC’s concerns as they no longer contained the no set-up fee representation and the requirements of s 53C were met. I accept these submissions.

94 In relation to the second phase advertisements, the evidence is that before commencing the second phase advertisements TPG obtained legal advice from relevantly experienced external solicitors. It says, and I accept, that the second phase advertisements were published substantially in accordance with the legal advice it received.

The interlocutory application

95 The ACCC made an urgent application for interlocutory relief in relation to the second phase advertisements which was heard by Ryan J on 22 December 2010, with judgment given the following day. His Honour declined to grant the injunctions sought, and did not consider that the ACCC's case was a strong one.

96 TPG says, and I accept, that it is relevant to assessment of penalty that its success in the interlocutory application meant that it was entitled to have more confidence in its position. By the time the injunction application came on for hearing it had also received a short advice from counsel advising that it had excellent prospects at least in relation to the no additional service or charge representation.

97 However, it must be said that a favourable interlocutory decision does not act as an indemnity for TPG's contraventions. The application was heard and the decision handed down urgently two days before Christmas, and the Court was not supplied with the detailed evidence, or allowed the time for consideration available at trial.

The relevance of legal advice received

98 TPG argues that its substantial reliance on legal advice received throws a different light on its conduct, indicating a misjudgement rather than a deliberate intent to breach the TPA. Its legal advice is in evidence and it is, in the main, positive as to TPG’s prospects.

99 In Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 131 FCR 529 ("Universal Music”) the Full Court considered an appeal from a decision in which the penalty imposed had been set at the bottom of the range, for reasons which included the trial judge’s view that:

(a) the contravenor had obtained legal advice from its solicitors to the effect that it would not be a contravention of the TPA to act as it did;

(b) the legal advice was relevantly unqualified; and

(c) whether the conduct in question contravened the Act was a most difficult one on which minds could differ and a question which had not been previously agitated in a Court.