FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nojin v Commonwealth of Australia [2011] FCA 1066

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| ELIZABETH NOJIN ON BEHALF OF MICHAEL NOJIN Applicant | |

| AND: | First Respondent COFFS HARBOUR CHALLENGE INC Second Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 16 SEPTEMBER 2011 |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The question of costs be reserved.

3. On or before 30 September 2011, the respondents file and serve written submissions concerning costs.

4. If the respondents file and serve written submissions seeking an order for costs in their favour, the applicant file and serve written submissions concerning costs on or before 14 October 2011.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 797 of 2008 |

| BETWEEN: | GORDON PRIOR Applicant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent STAWELL INTERTWINE SERVICES INC Second Respondent |

| JUDGE: | GRAY J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 16 SEPTEMBER 2011 |

| WHERE MADE: | MELBOURNE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The question of costs be reserved.

3. On or before 30 September 2011, the respondents file and serve written submissions concerning costs.

4. If the respondents file and serve written submissions seeking an order for costs in their favour, the applicant file and serve written submissions concerning costs on or before 14 October 2011.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 796 of 2008 |

| BETWEEN: | ELIZABETH NOJIN ON BEHALF OF MICHAEL NOJIN Applicant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent COFFS HARBOUR CHALLENGE INC Second Respondent |

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 797 of 2008 |

| BETWEEN: | GORDON PRIOR Applicant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent STAWELL INTERTWINE SERVICES INC Second Respondent |

| JUDGE: | GRAY J |

| DATE: | 16 SEPTEMBER 2011 |

| PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

The nature and history of the proceedings

1 The applicants in these two proceedings contend that the use of a particular method of assessing the level of wages to be paid to disabled people employed in Australian Disability Enterprises has resulted in unlawful discrimination. The crucial question is whether the use of that method involves requiring the disabled persons to comply with requirements or conditions and, if so, whether those requirements or conditions are not reasonable, having regard to the circumstances of each case, within the meaning of s 6(b) of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (“the Disability Discrimination Act”).

2 In proceeding number VID 796 of 2008, the named applicant is Elizabeth Nojin, who is described as bringing the proceeding “on behalf of Michael Nojin”. Michael Nojin is a 44 year old man who suffers from cerebral palsy and has a moderate intellectual disability. He also has epilepsy, causing frequent seizures of the kind known as “petit mal”. Having regard to the provisions of O 43 r 1(3) and O 43 r 2(1) of the Federal Court Rules as they then stood, it would have been more appropriate to name Michael Nojin as the applicant, with Elizabeth Nojin (who is his mother) named as his next friend, or appointed as his tutor for the purposes of the proceeding. At the times when the events the subject of this proceeding occurred, Mr Nojin was employed by Coffs Harbour Challenge Inc (“Coffs Harbour Challenge”), the second respondent to the proceeding. Coffs Harbour Challenge is now in liquidation. Counsel for Mr Nojin sought leave to proceed against Coffs Harbour Challenge, notwithstanding the liquidation. In the absence of objection by the first respondent, the Commonwealth of Australia, or by the liquidator of Coffs Harbour Challenge, I granted leave.

3 The applicant in proceeding number VID 797 of 2008 is Gordon Prior. Mr Prior gave evidence in the course of the trial of the proceeding on his 58th birthday. He has a vision impairment, which has resulted in his classification as legally blind, although he has some vision. He also has a mild to moderate intellectual disability. When the events relevant to the proceeding occurred, Mr Prior was employed by Stawell Intertwine Services Inc (“Stawell Intertwine”), the second respondent to the proceeding. As was the case in Mr Nojin’s proceeding, the Commonwealth of Australia is the first respondent.

4 Both Coffs Harbour Challenge and Stawell Intertwine were Australian Disability Enterprises, eligible to receive funding from the Commonwealth of Australia for the purpose of enabling them to provide support programs, including employment, for disabled people, pursuant to the Disability Services Act 1986 (Cth) (“the Disability Services Act”). Each was established as a non-profit organisation. Each entered into contracts to provide to businesses services that involved work that disabled persons were capable of performing. The term “Australian Disability Enterprise” (“ADE”) is the current term for such organisations, which were formerly known as Business Services and, prior to that, sheltered workshops. Among the services offered by Stawell Intertwine was attempting to secure employment for disabled persons with employers who otherwise employed wholly or mainly persons without disabilities, described as “open employment”. In the case of Mr Prior, Stawell Intertwine was successful in placing him in open employment. Stawell Intertwine was offered a contract to provide laundry services for a hospital. Instead of undertaking to provide those services itself, it arranged for the contract for laundry services to be offered to a laundry and dry-cleaning business, on the basis that the business would also employ one disabled person. That person is Mr Prior.

5 Whilst working for their respective ADEs, Mr Nojin and Mr Prior each underwent assessment to determine the level of wages they would receive for the work they performed. In each case, the assessment was provided free of charge by the Commonwealth of Australia, through the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service, known as CRS Australia (“CRS”), which is part of the Department of Families, Health and Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Each assessment was conducted by using the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool (“BSWAT”). There are two aspects of the BSWAT alleged by the applicants to be discriminatory in respect of persons with intellectual disabilities. The first is that, as well as testing for productivity, BSWAT requires testing for what are called competencies. There are four units of core competency prescribed and up to four units of industry-specific competency, which are agreed between the assessor and the relevant ADE. If fewer than four industry-specific competencies are chosen, then a person assessed can achieve only a maximum of 25% of the total possible score for industry-specific competencies for each such competency tested. The second discriminatory requirement or condition alleged is that the competencies are tested by means of question and answer. An inability to answer, or an answer regarded by the assessor as incorrect, in relation to any of the questions that are part of the testing of a particular competency will result in a score of zero for that competency as a whole.

6 These requirements and conditions are said to function in a discriminatory way in relation to people with intellectual disabilities, because they will have greater difficulty satisfying the tested competencies, and in coping with the question and answer method, than persons whose disabilities are not intellectual. The applicants also invite comparison with another assessment method, the Supported Wage System (“SWS”), which tests productivity only and is commonly used to determine the wage levels of disabled people in open employment.

7 The primary allegation of unlawful discrimination is made against Coffs Harbour Challenge and Stawell Intertwine respectively. The Commonwealth is alleged to have caused, induced or aided Coffs Harbour Challenge and Stawell Intertwine to discriminate unlawfully by approving BSWAT, distributing information about BSWAT, making available to ADEs free wage assessments conducted by the Commonwealth through CRS, and conducting the assessments.

8 In each case, the respondents asserted that the requirements or conditions of BSWAT were reasonable, having regard to the circumstances of the case. They relied on the charitable and non-profit nature of Coffs Harbour Challenge and Stawell Intertwine, their limited resources, the practical difficulties of adopting different methods of wage assessment for different employees, and the very substantial history of the development and adoption of BSWAT as the Commonwealth’s preferred wage assessment tool for employees in ADEs. In addition, the respondents contended that the application of the BSWAT was reasonably intended to afford to Mr Nojin and Mr Prior access to services or opportunities to meet their special needs in relation to employment or the administration of Commonwealth programs, or to afford them benefits or programs to meet their special needs in relation to employment or the administration of Commonwealth programs. In Mr Nojin’s case, the respondents also pleaded a defence that the application of the BSWAT was in direct compliance with an award of a tribunal having power to fix minimum wages, or a certified agreement, or a prescribed law, but this defence was abandoned during the course of the trial.

The legislation

9 Although no reliance was placed on it in either of these proceedings, the definition found in s 5 of the Disability Discrimination Act is useful for comparative purposes:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a person (discriminator) discriminates against another person (aggrieved person) on the ground of a disability of the aggrieved person if, because of the aggrieved person’s disability, the discriminator treats or proposes to treat the aggrieved person less favourably than, in circumstances that are the same or are not materially different, the discriminator treats or would treat a person without the disability.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), circumstances in which a person treats or would treat another person with a disability are not materially different because of the fact that different accommodation or services may be required by the person with a disability.

10 The applicant in each proceeding relied on the definition in s 6 of the Disability Discrimination Act:

For the purposes of this Act, a person (discriminator) discriminates against another person (aggrieved person) on the ground of a disability of the aggrieved person if the discriminator requires the aggrieved person to comply with a requirement or condition:

(a) with which a substantially higher proportion of persons without the disability comply or are able to comply; and

(b) which is not reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the case; and

(c) with which the aggrieved person does not or is not able to comply.

11 In both proceedings, reliance was placed on the following provisions of s 15 in Div 1 of Pt 2 of the Disability Discrimination Act:

(1) It is unlawful for an employer or a person acting or purporting to act on behalf of an employer to discriminate against a person on the ground of the other person’s disability…

(c) in the terms or conditions on which employment is offered.

(2) It is unlawful for an employer or a person acting or purporting to act on behalf of an employer to discriminate against an employee on the ground of the employee’s disability…

(a) in the terms or conditions of employment that the employer affords the employee; or

(b) by denying the employee access, or limiting the employee’s access, to opportunities for promotion, transfer or training, or to any other benefits associated with employment; or

…

(d) by subjecting the employee to any other detriment.

In fact, in each amended statement of claim, there is a reference to s 15(2)(c), which relates to dismissing an employee. It is not contended that either Mr Nojin or Mr Prior was dismissed from employment, so I have taken it that the allegations of denial or limitation of the access of each of them to higher remuneration is intended to be an allegation falling under subs (2)(b), higher remuneration being the relevant benefit. The allegation of detriment pursuant to subs (2)(d) in each case is an allegation of reduced remuneration. In fact, there has been no reduction, only an absence of an increase beyond what was assessed.

12 In each proceeding, there is also an allegation of contravention of s 24(1)(b) in Div 2 of Pt 2 of the Disability Discrimination Act, which provides relevantly:

It is unlawful for a person who, whether for payment or not, provides…services…to discriminate against another person on the ground of the other person’s disability…

(b) in the terms or conditions on which the first-mentioned person provides the other person with those…services

The services alleged are supported employment.

13 Section 45 of the Disability Discrimination Act is in Div 5 of Pt 2. So far as relevant to the present proceeding, it provides:

This Part does not render it unlawful to do an act that is reasonably intended to:

…

(b) afford persons who have a disability or a particular disability,…access to facilities, services or opportunities to meet their special needs in relation to:

(i) employment…

(ii) the provision of…services…

(iv) the administration of Commonwealth…programs…

(c) afford persons who have a disability or a particular disability…benefits or programs, whether direct or indirect, to meet their special needs in relation to:

(i) employment…

(ii) the provision of…services…

(iv) the administration of Commonwealth…programs

14 Finally, s 122 of the Disability Discrimination Act provides:

A person who causes, instructs, induces, aids or permits another person to do an act that is unlawful under Division 1, 2…of Part 2 is, for the purposes of this Act, taken also to have done the act.

The requirements of BSWAT

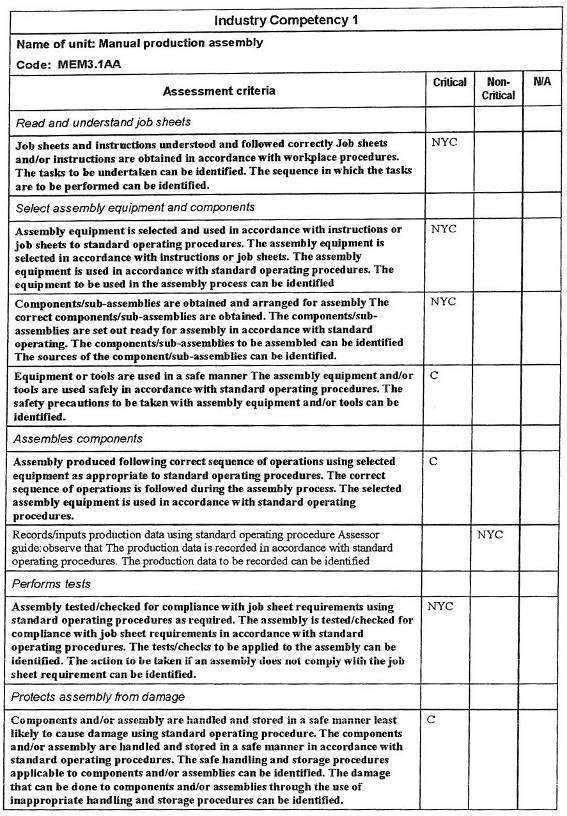

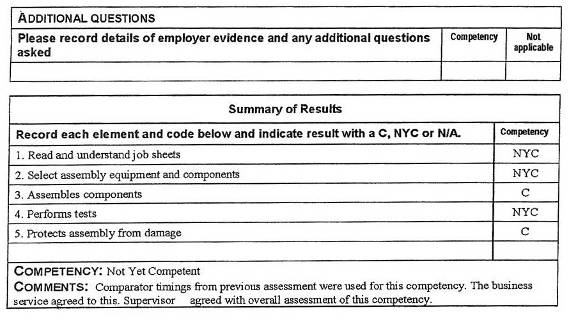

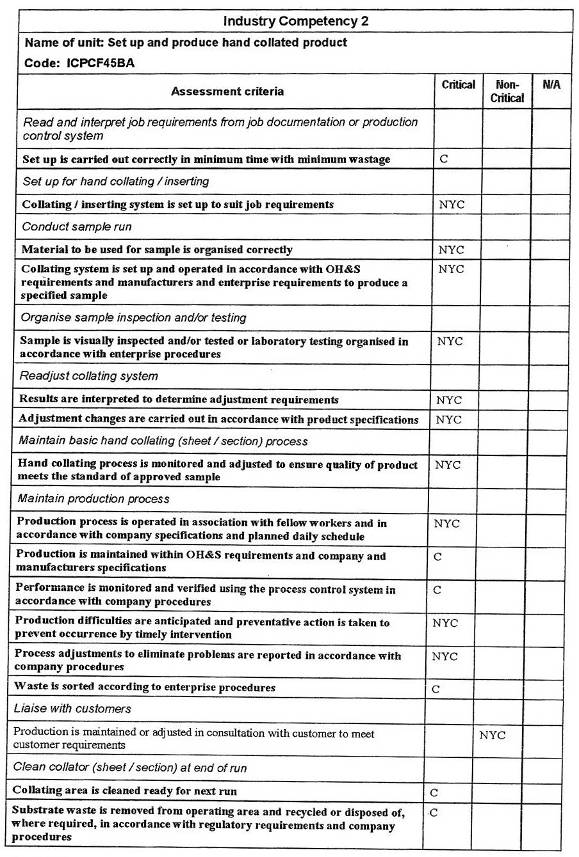

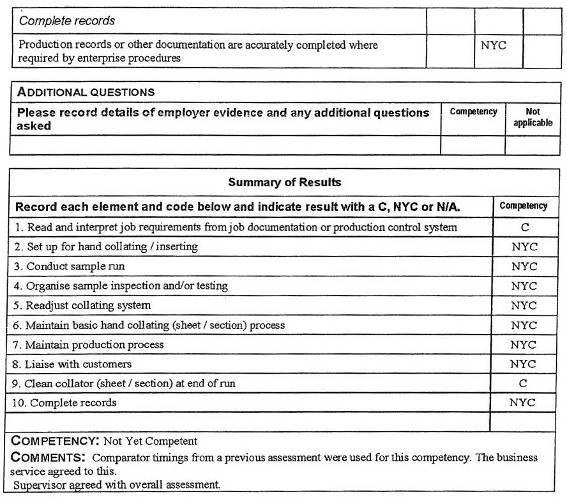

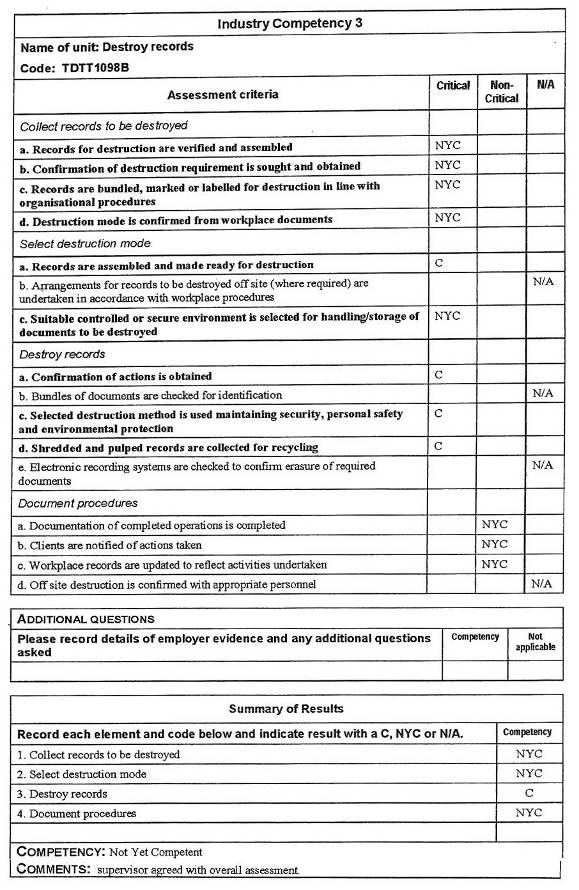

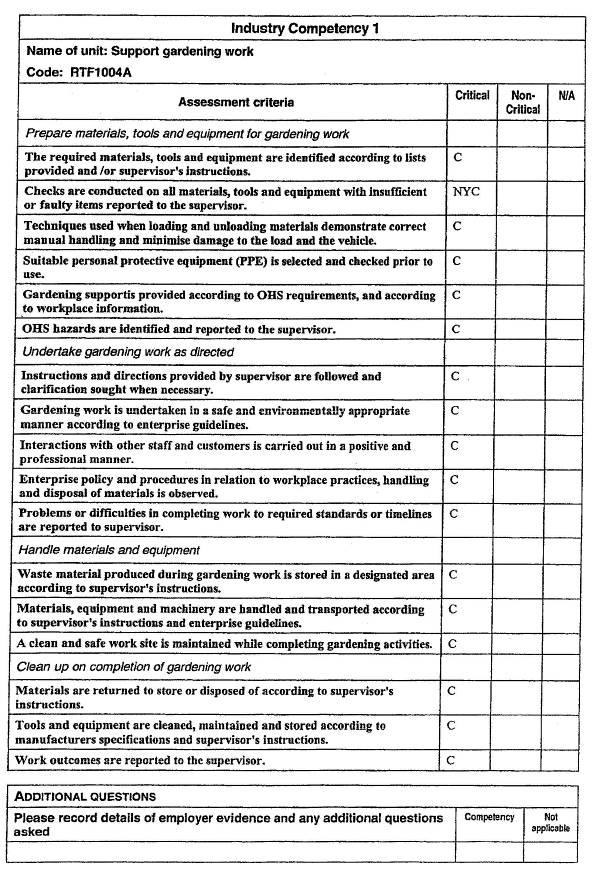

15 The nature of the four core competencies against which Mr Nojin and Mr Prior were assessed is best understood by looking at the form provided to assessors, which they complete by way of a report of the results of assessments of particular persons:

In the following core competency checklists, ‘C’ indicates competent, NYC indicates not yet competent and N/A indicates it is not applicable.

| Follow Workplace Health and Safety Practices | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Conduct Work Safely | |

| • Protective clothing or equipment is identified and used appropriately | |

| • Basic safety checks on equipment are undertaken prior to operation | |

| • Set up and organise work station in accordance with OH&S standards | |

| • Follow safety instructions | |

| • Manual handling tasks are carried out accurately to recommended safe practice | |

| • Waste is disposed of safely in accordance with the requirements of the workplace and OH&S legislation | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What do you do if you or someone else hurts themselves at work? • Tell supervisor • Get help e.g. Nurse, ring ambulance, get first aid officer • Turn off machinery, remove from danger | |

| Why do you use/wear protective clothing or equipment? • noise • using machines • working with pesticides/chemicals • dust • sun | |

| What would make your workplace unsafe? • spills • faulty equipment • poor surfaces etc (refer to range of variables) | |

| What do you do when you notice something is unsafe at work? • remove the hazard • report to appropriate personnel • fill in relevant documentation | |

| What do you do if the fire alarm goes off? • exit the workplace following evacuation procedures • assemble in designated area • wait for further instructions | |

| Why is it important to follow evacuation procedures? • ensures orderly evacuation • workplace can be assessed for safety • all employees can be accounted for | |

| What are some of the ways you move objects in the workplace? • manual lifting • trolley • pallet jack • forklift | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments:

| |

| Communicate in the Workplace | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Gather and respond to information | |

| • Instructions are correctly interpreted | |

| • Clarification is sought from appropriate personnel when required | |

| • Workplace interactions are conducted in a constructive manner | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What work have you been asked to do today? • Clarify work requirements with supervisor | |

| In what order should the work be completed? • Clarify work requirements with supervisor | |

| What do you do if you are unsure about what work needs to be done? • Clarify with appropriate person | |

| What workplace meetings do you attend? • OH&S • Work performance/review/Individual Employment Plan • Work group/staff meetings • Union meetings | |

| What are these meetings for? • Worker to describe role and function of different meetings | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments:

| |

| Work with others | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Participate in group processes | |

| • Co-workers’ individual differences are taken into account eg. o Respect for others’ personal space and property, o Cultural, physical and/or cognitive differences are respected, o Tolerance of others in the workplace. | |

| • Worker adapts to changing work roles (observe worker in different roles to confirm) | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What are some other jobs that people do here? • Has an understanding of what other workers do in the workplace | |

| How can you help others at work? • Do own job well • Be on time, keep area clean and tidy • Help others when they require it (e.g. busy, complex work, etc) • Make suggestions for improvement | |

| If you had a disagreement with someone in the workplace, what would you do? • Discuss it with the person • Ask for assistance from your supervisor • Make a formal complaint | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments:

| |

| Apply quality standards | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Assess quality of own work | |

| • Work instructions are followed and tasks performed in accordance with quality requirements | |

| • Non compliant materials or products are identified and isolated | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| How do you know if a part/service is faulty? • Can describe non-compliant products/services | |

| What do you do if the part/service is faulty? • Isolate non-compliant part • Report to supervisor • Document, where necessary • Identify causes and possible solutions | |

| Why is it important not to make too many mistakes? • Waste materials • Waste time • Possibly damage equipment • Poor customer service | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments: | |

16 Mr Nojin was assessed on 23 May 2005 by Mr Greg Vigors of CRS. He received a “C” in respect of every item in the first competency and was assessed as “Competent”. Mr Vigors commented:

Supervisors [sic] workbook originally marked Mr Nojin as not yet competent. Since that time further OH&S training had been carried out by Challenge. Mr Nojin’s supervisor agreed that He [sic] was now competent in this area.

17 In respect of each of the other core competencies, Mr Nojin was assessed as “Not Yet Competent” and received the comment “Supervisor agreed with overall assessment.” In relation to the competency concerning communication in the workplace, Mr Nojin was graded “C” in respect of all items except for the question “What workplace meetings do you attend? and the question “What are these meetings for?”, in respect of each of which he was assessed as “NYC”. In respect of the core competency relating to working with others, Mr Nojin was assessed as “C” with respect to every item other than the question “What are some other jobs that people do here?”, for which he was assessed as “NYC”. In respect of the competency relating to applying quality standards, Mr Nojin was assessed as “C” in respect of the two observation items and the question “What do you do if the part/service is faulty?”, but was assessed as “NYC” in relation to the other two questions.

18 At the request of his mother, Mr Nojin was reassessed by Mr Vigors on 12 August 2005. There was a conflict of evidence as to whether the reassessment included re-examination of the core competencies. Kairsty Wilson, the senior lawyer for AED Legal Centre (formerly known as Disability Employment Action Centre or DEAC), who was present at both assessments, recalled that the competency assessments were redone. The recollection of Mr Vigors was to the contrary. It is more probable than not that Ms Wilson’s recollection is inaccurate. The fact that the scores recorded for the four core competencies on the reassessment are precisely the same as those recorded on the original assessment, together with a note of Mr Vigors on the reassessment report concerning the nature of the reassessment, lead to this conclusion.

19 There was also a conflict between the recollection of Ms Wilson and that of Mr Vigors about the actual content of Mr Nojin’s work tasks in both assessments. Strictly, it is unnecessary to resolve this conflict, although I am inclined to prefer the account given by Ms Wilson as to two of the issues. The task of collating pamphlets did not involve envelopes. The pens Mr Nojin assembled had only two parts, a rustic-looking twig and a short ink tube with a ball point. There was no spring mechanism. It is not possible to make a clear finding about the size of the shredding machine into which Mr Nojin was feeding documents. Nor is the exact content of the task of preparation of documents for shredding clear, except that the machine was able to deal with staples, which therefore did not have to be removed.

20 Mr Prior’s first assessment was by Rebecca McIntyre of CRS on 6 February 2007. Mr Prior was rated as “Not Yet Competent” in respect of all four core competencies. As to the competency relating to workplace health and safety practices, he was rated “NYC” on the second observation item “Basic safety checks on equipment are undertaken prior to operation”. Otherwise, he was rated “C” for all observation items and all questions. Ms McIntyre’s comments on this competency were:

The worker answered all questions in this section correctly and showed a good understanding of OH&S in the workplace. He can complete safety checks on equipment but requires supervisor’s assistance to complete this correctly. Supervisor comments: Gordon understands that he must check the mower to make sure that is [sic] runs correctly and it has the appropriate fuel and no vibrations/unusual noise. Gordon also gives the mower a visual check but still requires some assistance as his eyesight can contribute to him overlooking a problem. Supervisor workbook and assessor observations were in agreement.

21 In respect of the competency concerning communication in the workplace, Mr Prior was assessed as “NYC” on the first observation item “Instructions are correctly interpreted”. He was assessed as “C” on both other observation items and all five questions. Ms McIntyre’s comments were:

The worker was observed to always ask for assistance when he required it and again answered all the questions in this section correctly. He at times needs instructions to be repeated but he listens and asks questions if he does not understand. Supervisor comments: The level of Gordon’s understanding can vary between jobs of varying degrees. Instructions to Gordon must be very clear and concise. If the job involves several instructions there must be support offered as Gordon will forget or become confused in what order the instructions were given. Tasks are best broken down to make them smaller and easier for Gordon to understand and carry out. Supervisor workbook and assessor observations were in agreement.

22 In respect of the competency relating to working with others, Mr Prior was assessed as “NYC” on both the questions “How can you help others at work?” and “If you had a disagreement with someone in the workplace, what would you do?” Ms McIntyre’s comments were:

The worker works well with his co-workers most of the time, he interacts well with his supervisor and does adapt well to changing work roles. Supervisor Comments: When a request is made of Gorgon [sic] by the supervisor he will comply immediately and carry out the given task. If a request is made of Gordon by a co supported [sic] employee he may interpret it the request [sic] as an order and become agitated. He will also at times approach the Supervisor [sic] and ask how many “bosses” there are. The supervisor must then explain to Gordon that it is a request for help, not an order so he will then go and give the required assistance. Supervisor workbook and assessor observations were in agreement.

23 In respect of the fourth core competency, relating to applying quality standards, Mr Prior was assessed as “NYC” on the second observation item “Non compliant materials or products are identified and isolated”, and in respect of the first two questions, “How do you know if a part/service is faulty?” and “What do you do if the part/service is faulty?”. He was assessed as “C” in relation to the first observation item and the last question. Ms McIntyre’s comments were:

Due to the workers [sic] eyesight at times he is not able to identify his own mistakes. He is very happy for the supervisor to identify them for him and then will go and fix them. Once he is shown his quality issues then he completes the work well and to the required quality standard.

24 At his request, Mr Prior was reassessed, this time by Sarah-Jane Nutting of CRS on 8 May 2008. On the first core competency, relating to workplace health and safety practices, Ms Nutting assessed Mr Prior as “NYC” on the second, third and fourth observation items, “Basic safety checks on equipment are undertaken prior to operation”, “Set up and organise work station in accordance with OH&S standards” and “Follow safety instructions”. She assessed him as “C” in respect of the other three observation items and all questions. Overall on this competency, he was rated “Not Yet Competent”. Ms Nutting’s comments were:

“Gordon was observed to commence the mowing task without conducting basic checks on the mower he was using. Gordon was also observed to require supervisor assistance in setting up the mower prior to use, for example the supervisor filled the fuel tank on the mower for Gordon. The supervisor indicated that workers have been trained to turn the mower off when removing and emptying the catcher however Gordon was observed on two occasions to empty the catcher with the mower still running. The supervisor then reminded Gordon of this requirement.

Gordon was able to appropriately answer the questions asked during the assessment interview.

The overall rating for this competency is supported by observations of the worker and information gained from the supervisor and supervisor’s workbook during the assessment period. All information provided indicated that the worker’s performance during the assessment was consistent with usual work behaviour.

25 In respect of the second core competency, relating to communication in the workplace, Mr Prior was assessed as “Not Yet Competent”, on the basis of a “NYC” assessment on the first observation item, “Instructions are correctly interpreted”. He was assessed as “C” in respect of the other two observation items and all five questions. Ms Nutting’s comments were:

Gordon was observed to require instructions to be repeated to him for example the supervisor was required to repeat to Gordon the areas he required him to rake. The supervisor indicated that he gives Gordon instructions in steps as he will often forget instructions or steps involved in a task. Gordon was observed to clarify work instructions with the supervisor on numerous occasions during the assessment period and discussions with the supervisor indicated that this is usual practice for the worker.

Gordon was able to appropriately answer all assessment questions.

The overall rating for this competency is supported by observations of the worker and information gained from the supervisor and supervisor’s workbook during the assessment period. All information provided indicated that the worker’s performance during the assessment was consistent with usual work behaviour.

26 In respect of the core competency relating to working with others, Mr Prior was assessed as “NYC” in respect of the second observation item “Worker adapts to changing work roles” and the second question “How can you help others at work?”. He was assessed as “C” in respect of the other observation item and the other two questions. His overall assessment was “Not Yet Competent”. Ms Nutting’s comments were:

Gordon was observed to be tolerant and respectful toward other workers and staff during the assessment period. Gordon was observed performing two tasks, raking leaves and mowing lawns, during the assessment however information from the supervisor indicates that Gordon refuses to perform some tasks when asked such as loading tree branches onto the trailer. He will instead stand and watch other workers performing this task.

Gordon was unable to appropriately answer “How can you help others at work?” stating that he would try not to get involved. With some prompting he then said that he would help them finish the job.

The overall rating for this competency is supported by observations of the worker and information gained from the supervisor and supervisor’s workbook during the assessment. All information provided indicated that the worker’s performance during the assessment was consistent with usual work behaviour.

27 In respect of the core competency relating to applying quality standards, Mr Prior was assessed as “NYC” in relation to both observation items, “Work instructions are followed and tasks performed in accordance with quality requirements” and “Non compliant materials or products are identified and isolated”, and as “C” in respect of all three questions. His overall rating was “Not Yet Competent”. Ms Nutting’s comments were:

Gordon was observed to have issues with completing mowing tasks to the quality standard required in the workplace. He was observed to miss patches of grass when undertaking this task and the supervisor supported this information indicating that another worker often has to mow behind Gordon to ensure the mowing is completed to standard. Gordon was also observed mowing over concrete in the middle of the grass causing the mower blades to grind against the concrete. The supervisor reported that this work performance is consistent with Gordon’s usual performance.

Gordon was able to answer all assessment questions asked.

The overall rating for this competency is supported by observations of the worker and information gained from the supervisor and supervisor’s workbook during the assessment period. All information provided indicated that the worker’s performance during the assessment was consistent with usual work behaviour.

28 In addition to the four core competencies, the BSWAT requires assessment in up to four industry competencies, selected from the database of competencies identified for the purposes of the Australian Quality Training Framework (“AQTF”), originally administered by the Australian National Training Authority (“ANTA”). Where it is not possible to identify four industry-specific competencies applicable to a particular employee, a lower number can be used. In such cases, the employee can only be credited in respect of the competencies he or she has been assessed as competent for. The result is an automatic reduction in the level of wages assessed, because of the unavailability of the additional industry competency or competencies.

29 In the case of Mr Nojin’s first assessment, three industry competencies were identified. The relevant extracts from the report of Mr Vigors in respect of his assessment of Mr Nojin on 23 May 2005 are as follows:

It will be seen that Mr Nojin was assessed as not yet competent in respect of each of these industry competencies. The same results appear in Mr Vigors’s report of his reassessment of Mr Nojin on 12 August 2005. The comments were changed, however. In relation to each of the three industry competencies, Mr Vigors said in his reassessment report:

All parties agreed to use timings from initial assessment with fourth timing undertaken after lunch break. Original comparator timings were used.

After that comment in relation to the third industry competency, Mr Vigors added:

Timings for the additional task “Prepare documents for shredding…” were undertaken in the morning. I had originally envisaged undertaking two morning and two afternoon timings for this task but after the two morning timings were collected Kairsty Wilson from DEAC requested that due to time constraints there be the [sic] only two timings obtained. I conferred with Ian Wade from Coffs Harbour Challenge and he consented to this. I then reconfirmed this arrangement with Kairsty Wilson.

Original comparator timings were used.

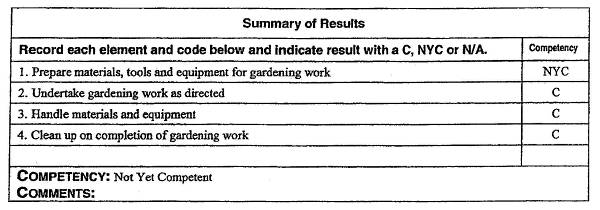

30 In both of the assessments of Mr Prior, only one industry competency was selected. In relation to that competency, the report of Ms McIntyre as to her assessment conducted on 6 February 2007 is as follows:

In the view of Ms Nutting, on her reassessment of Mr Prior on 8 May 2008, he fared worse. As well as assessing him as “NYC” in respect of the item “Checks are conducted on all materials, tools and equipment with insufficient or faulty items reported to the supervisor.” Ms Nutting assessed Mr Prior as “NYC” on four other items: “Gardening supportis [sic] provided according to OHS requirements, and according to workplace information.”, “OHS hazards are identified and reported to the supervisor.”, “Instructions and directions provided by supervisor are followed and clarification sought when necessary.” and “Tools and equipment are cleaned, maintained and stored according to manufacturers [sic] specifications and supervisor’s instructions.” As a result, Mr Prior was still assessed as “NYC” in respect of the industry competency, having been assessed as “C” only on the third item, “Handle materials and equipment”.

31 As well as the competency assessments, the BSWAT makes provision for productivity assessments. These are conducted by observing the employee performing routine work of the kind he or she normally does and comparing that performance with that of a non-disabled person doing the same task. Depending upon the nature of the task, the comparison can be either of the number of units dealt with during a set period, or of the time taken to complete a specified task.

32 In his first assessment on 23 May 2005, Mr Nojin was asked to perform three tasks: pamphlet collation, which involved inserting flyers into pamphlets, the flyers and pamphlets already being on hand; pen assembly, which involved fitting a ballpoint ink insert into a wooden pen casing, with the inserts and casings already on hand; and feeding one crate of pre-sorted documents through a mechanical shredder. The first two tasks involved measuring the number of units completed in 15 minutes. The third involved measuring the time taken to complete the task. In three separate periods of 15 minutes, with intervals between them, Mr Nojin completed the collation of 25, 24 and 30 pamphlets and flyers, compared with his supervisor’s completion of 296, 318 and 279 respectively. In three further periods of 15 minutes each, with intervals between, Mr Nojin assembled 21, 29 and 30 pens, compared with his supervisor’s 114, 126 and 126. In three separate episodes of feeding documents into the shredder, again separated by intervals, Mr Nojin took 55 minutes and 24 seconds, 39 minutes and 59 seconds and 41 minutes and 51 seconds, as against his supervisor’s 19 minutes and 28 seconds and 20 minutes and 20 seconds.

33 On his second assessment on 12 August 2005, Mr Nojin was asked to perform an additional episode of each of those three tasks. On that occasion, he collated 27 pamphlets and flyers in 15 minutes and assembled 30 pens in 15 minutes. He also fed one further crate of pre-sorted documents through the mechanical shredder, taking 34 minutes and three seconds. In respect of all these tests on this occasion, no further comparator testing was performed. A comparison was made between the new tests and the old comparator data. In addition, Mr Nojin was asked to perform a fourth task, that of preparing documents for shredding, which involved sorting one standard tray of mixed documents, which was on hand. He did this twice, taking 10 minutes and 16 seconds and 10 minutes and 51 seconds, compared with five minutes and five seconds and four minutes and 42 seconds for the comparator.

34 Each of the tasks involved in the productivity assessment was given a time weighting, designed to represent the percentage of the working time of the person assessed represented by that task. In the case of Mr Nojin’s first assessment, pamphlet collation was weighted at 40%, pen assembly at 10% and document shredding at 50%. In the case of the second assessment, the 50% for document shredding was divided between document shredding and preparing documents for shredding, the former being allocated 20% and the latter 30%. Using the results of the tests in conjunction with these figures, the assessor calculated a productive capacity figure, represented as a percentage. The result of Mr Nojin’s first test was a productivity assessment of 27.48%. On his second test, the result was 16.54%. His performance on the additional task dragged down his score.

35 The next stage in the assessment is to ascertain the relevant full wage rate. In each case, this was done by reference to a classification in an industrial award. The applicable hourly rate determined for Mr Nojin was $12.30. The formula for determining the percentage of this wage rate applicable was to add the total competency score, expressed as a percentage, to the productivity score and to divide the result by two, thereby producing an average percentage. This average percentage is the percentage of the wage rate to be paid to the person assessed. In Mr Nojin’s case, he scored 12.50% in competencies and 27.48% in productivity, giving an overall assessment of 19.99%. His assessed wage was $2.46 per hour, being 19.99% of $12.30. On the second assessment, Mr Nojin’s competencies score of 12.50% was added to his productivity score of 16.54%. Half of the total was 14.52%. His wage was assessed at $1.79 per hour, being 14.52% of $12.30.

36 The productivity assessment for Mr Prior’s first wage assessment on 6 February 2007 involved measuring the time taken to mow an area of lawn five metres by ten metres, with the catcher on correctly. Mr Prior’s time was 14 minutes and 10 seconds. His supervisor, who was the comparator, took 9 minutes to mow a similar area. According to Ms McIntyre’s notes as to “Special arrangements” in her report, “Only one timing was able to be obtained in the productivity section for both the worker and comparator due to the drought there was not enough grass to mow around Stawell.” The second task was designated as “The ability to perform the tasks on weeding, pruning, hedge trimming and general gardening tasks.” As Ms McIntyre’s notes record:

All other tasks the worker performs have been marked in a percentage form as there were too many variables to obtain accurate timings. This has all been discussed and agreed to by the Business Service.

The agreed figure for Mr Prior’s productivity was 50, against the comparator’s 100. The time weighting for each of the two tasks was 50%.

37 On Mr Prior’s second assessment, Ms Nutting’s notes of “Special arrangements” are as follows:

A reassessment was requested by Mr Prior and DEAC due to issues with the previous wage assessment outcome. Kairsty Wilson, DEAC, was present for the assessment as an advocate for Mr Prior.

All aspects of this assessment was discussed with Business Service and agreement was reached on Industry competencies, productivity tasks and timings undertaken.

Task 1 - Mow lawns with push mower.

Time taken to mow area of lawn with push mower to workplace standard. Includes emptying catcher when required.

The following areas were assessed for the purpose of this task:

T1 - Approximately 14m X 12m - Lake Fyans Caravan Park

T2 - Approximately 7m X 15m - Lake Fyans Caravan Park

T3 - Approximately 2.5m X 30m - Stawell Intertwine Office

T4 - Approximately 4m X 27m - Stawell Intertwine Office

Task 2 - Raking and disposing of leaves.

Rake leaves into piles in area as instructed by Supervisor then dispose of leaves in trailer.

Given the nature of the task an agreed productivity percentage has been determined for this task. This is based on observation of the worker undertaking this task, and discussion with the Business Service to ensure the rate is reflective of the worker’s usual performance.

38 The times Mr Prior took for the mowing tasks were 15 minutes and 25 seconds, 19 minutes and 21 seconds, 15 minutes and 11 seconds and 14 minutes and 50 seconds, as against his supervisor’s times of six minutes and 39 seconds, eight minutes and 14 seconds, 10 minutes and 21 seconds and seven minutes and 32 seconds respectively. In respect of the second task, raking and disposing of leaves, the agreed figure for Mr Prior was 50 and for the comparator 100. On this occasion, the lawn mowing task was given a time weighting of 90% and the raking and disposing of leaves a time weighting of 10%.

39 For Mr Prior’s first assessment, the applicable hourly rate, ascertained from a classification in an industrial award, was $13.47. As Mr Prior had been assessed as “Not Yet Competent” in relation to all of the competencies against which he was tested, his productive capacity percentage of 56.76 was divided by two, to determine his overall assessment score of 28.38%. His assessed wage was $3.82 per hour, being 28.38% of $13.47. On his second assessment, the applicable hourly rate was $13.74. Again, Mr Prior had been assessed as having achieved a zero score for competencies, so his productive capacity of 50.52% was divided by two, to achieve an overall assessment score of 25.26%. This resulted in an assessed wage of $3.47 per hour, being 25.26% of $13.74.

The development of the BSWAT

40 In its budget for the financial year 1990 to 1991, the Commonwealth Government introduced its Disability Reform Package. In part, the package introduced the Disability Support Pension (“DSP”) instead of the former Invalid Pension, introduced concessions to recipients of the DSP who took up employment, and put in place programs for rehabilitation and employment for people with disabilities. There was provision for further consideration of the development of a supportive wage system for people with disabilities, which had been recommended by an earlier report of the Labour and Disability Workforce Consultancy (“the Ronalds Report”). Overseeing the reforms was a Disability Taskforce, which established a Wages Subcommittee, one task of which was to oversee the work of a consultancy to develop assessment guidelines for the Supportive Wages System. The consultant engaged was Don Dunoon of New Futures Pty Ltd, with specialist assistance from Jennifer Green of the Australian Catholic University, Sydney. The consultant’s report (“the Dunoon Report”) was completed in January 1992.

41 Borrowing from the Ronalds Report, the Dunoon Report described the assessment of wages at the time in what were then called sheltered workshops. It referred to a variety of means, ranging from informal assessments by supervisors to elaborate systems in which various factors were given ratings. Commonly, there was an attempt to measure the productivity of an individual worker against a rate of pay for a non-disabled person. In some workshops, the level of productivity was not determined by reference to an award wage rate, but by reference to the assessment of the organisation running the particular workshop of its ability to pay. There was no specific award coverage for sheltered workshops. In some cases, an employee’s wages were adjusted up or down on the basis of an assessment of his or her attitudes and general behaviour, a subjective judgment not acceptable in other employment situations. This practice reflected a conflict between the rehabilitation and employment roles of those who provided services to people with disabilities. As the Ronalds Report had recorded, wages in workshops were very low, averaging $25 in June 1989. This was partly because of a means test, which reduced the government allowance payable to people in sheltered employment by 50c for each dollar of earnings above $42 per week.

42 The Dunoon Report was intended to provide “a consistent set of guidelines for the operation of an assessment process to determine the percentage of the award rate to be paid to disabled workers.” In developing the principles, the Dunoon Report dealt with the issue of work value. It recognised that, if a disabled person is employed on a restricted range of duties, then the jobs of other employees, not so restricted, may be more valuable to the employer if they involve skills of a higher order or more important in the workplace, or if there is a cost in terms of lost productiveness or flexibility to the employer of maintaining the restricted job. It recognised that the case for adjustment of wages below the award rate must be based on the worth of the job to be performed by the person with a disability, not the efficiency or productiveness of the disabled worker in comparison with other workers.

43 On 20 July 1994, the Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (“the AIRC”) decided to approve a model clause for insertion into a number of industrial awards, to facilitate the employment of workers with disabilities in open employment at a rate of pay commensurate with their assessed productive capacity. The assessment was to be made using the SWS. The introduction of the model clause was supported by the Australian Council of Trade Unions (“ACTU”), on behalf of a number of unions that were parties to the relevant awards, and by the employers that were parties to those awards, as well as the Commonwealth Government and the Governments of New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.

44 In 2000, a review was conducted of what had by then come to be called the Business Services sector. The review was a joint initiative of the Commonwealth, through its Department of Family and Community Services, and the Australian Council for the Rights of the Disabled (“ACROD”), an organisation representing Business Services. KPMG Consulting was commissioned to prepare a report for the review. The result was a report entitled “A Viable Future - Strategic Imperatives for Business Services”, published in 2000. A major theme of the report was that Business Services had a dual role. They were funded, and required, to provide meaningful paid employment for disabled people who might find it difficult to obtain or maintain jobs in open employment, or who chose to seek employment with Business Services. At the same time, they were required to conduct commercial operations. The report said that Business Services had expressed concerns as to the applicability of the SWS to their work, including concerns about the use of productivity as the sole determinant of wages. The report recommended:

That in employing people with disabilities with varying skill levels, that remuneration is linked to an individual’s productivity and to an agreed industry-wide system for assessing general work competencies.

45 In 2000, the Department of Family and Community Services of the Commonwealth commissioned an external consultant, Health Outcomes International Pty Ltd (“HOI”) to conduct a research project examining a range of different wage assessment strategies and processes for disabled people working in supported employment. A reference group was also established. This included a director of HOI, two representatives of Evolution Research (one of them Richard Giles), a competency consultant, an industrial relations adviser, representatives of the ACTU and representatives of the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Union (“LHMU”).

46 In May 2001, HOI produced a document entitled “A Guide to Good Practice Wage Determination”. The document aimed to present a view of what was considered good practice in the development of wage assessment and determination processes in Business Services. It contained a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of productivity-based assessment, the advantages and disadvantages of competency-based assessment and the advantages and disadvantages of hybrid models. The report said:

The research team concludes that a hybrid model represents the most appropriate method of wage determination in Business Services. However, the team is reluctant to recommend any of the existing assessment tools as the absolute best practice method of wage assessment for all services.

47 In June 2001, HOI produced a discussion paper entitled “Research into Pro-Rata Wage Assessment Tools for People Working in Business Services”. The recommendations in that discussion paper included the following:

Recommendation 1

A single wage assessment tool for wage determination in Business Services should be developed on behalf of FaCS. The assessment tool should be developed in close consultation with the sector, undergo extensive testing and build on the strengths of existing assessment processes.

…

Recommendation 2

The assessment tool should combine elements of both competency and productivity assessment, which links directly to endorsed industry standards wherever practicable. The development of the assessment tool should include identifying the competencies incorporated in industry training packages that are most applicable to Business Service activities.

48 By letter dated 2 July 2001, the Department of Family and Community Services invited comment by the ACTU on two documents, A Guide to Good Practice Wage Determination and the HOI discussion paper. In reply in relation to recommendation 2 of the discussion paper, the ACTU questioned whether it was practicable to apply industry competency standards as a significant element of wage fixing for workers with a disability. The ACTU could see a possible role for generic competencies, such as ability to work in a team, ability to take and follow instructions, understanding of the overall production or service process and where the individual employee fitted, and use of tools and items of equipment associated with the job. The ACTU submission said:

Whilst the ACTU has concerns about the practicality of competency assessment in this area and tends to support the use of generic competencies, we are open to further consideration of this issue based on the experience to date of workplaces which could be using this approach.

While questioning the practicality of complete matching of the competencies in industry standards, the ACTU expressed support for a recommendation that an assessment tool should combine elements of both competency and productivity assessment, linking directly to endorsed industry standards wherever practical. The ACTU also said that the development of the assessment tool should include identifying the competencies incorporated in industry training packages that were most applicable to the activities of Business Services. The ACTU also submitted that, with any system involving competency-based assessment, a big improvement in the provision of and access to suitable training was needed. It also said that, if life skills and appropriate work behaviour were included in competency, it agreed that these should be recognised and rewarded.

49 On 13 March 2002 the AIRC varied the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union Supported Employment (Business Enterprises) Award 1993. The variation was by way of deletion of all previous provisions and insertion of a complete new award, to be known as the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union Supported Employment (Business Enterprises) Award 2001 (“the 2001 Award”). Clause 3 of the 2001 Award provided:

3.1 This award will govern the wages and conditions of employment of all persons engaged in the performance of all work in or in connection with, or incidental to a prescribed service, eligible service as defined by the Disability Services Act 1986 (as amended) which operates a supported employment business enterprise which employs able body workers and people with disabilities in either a workshop enclave or work crew.

3.2 It is acknowledged that the organisations and services covered by this award do not, as a general rule, operate pure employment services in a strictly commercial sense. Rather, the organisations operate in an employment-like environment in which a range of additional support services are provided: Including vocationally-related training, work experience, assistance with progression to open employment (where possible), and a range of support services. Thus, the primary relationship that exists between the service agency and its employees who are disabled extends beyond that which is generally expected in an employer: employee relationship.

3.3 It is further acknowledged that this primary relationship will have a direct impact on the operational costs of the service concerned, and may impact on the conditions of employment that can be provided. (Refer also to 14.5.2).

Clause 14.3 provided:

Employees with a disability will be paid such percentage of the rate of the employees [sic] grade as equals the skill level of the employee assessed as a percentage of the skill of an employee who is not disabled.

Clause 14.4.6 provided:

The company and the union will confer with a view to reaching agreement on salary assessment system [sic] that properly remunerates people for their skills and abilities. Failing agreement the matters will be arbitrated by the Commission. Any new salary assessment system will operate from such a date as ratified or determined by the Commission.

So far as relevant to this proceeding, cl 14.5 provided:

14.5.1 Consultation will take place between the company and the union to ensure that additional costs resulting from wage and superannuation increases for employees with disabilities do not jeopardise the operation of the company or prevent or restrict the recruitment of future employees.

14.5.2 The parties acknowledge that there are additional costs incurred by supported employment business enterprises related to the ongoing support and training needs of people with disabilities. These additional costs will be taken into account in future negotiations.

50 On 1 July 2002, the Disability Services Amendment (Improved Quality Assurance) Act 2002 (Cth) came into operation. It amended the Disability Services Act by providing for the establishment of Disability Service Standards, with which Business Services would have to comply, in order to receive grants from the Commonwealth Government. As a result of the amendments, s 5A of the Disability Services Act empowers the Minister, by legislative instrument, to determine disability employment standards to be observed in the provision of an employment service referred to in Pt II. Section 7, in Pt II, contains a definition of employment service that includes supported employment services, which in turn are defined to mean services to support the paid employment of persons with disabilities for whom competitive employment at or above the relevant award wage is unlikely and who, because of their disabilities, need substantial ongoing support to obtain or retain paid employment. By s 12AD(2), the Minister is required not to approve the making of a grant unless the intended recipient of it holds a current certificate of compliance in respect of the service for which the grant is sought or has given written notice to the Minister of its intention to seek to obtain such a certificate on or before a day fixed by the Minister. Section 6D contains provision for the accreditation of organisations by means of a certificate that the accreditation certification body is satisfied that the service meets the disability employment standards.

51 The Disability Services (Disability Employment and Rehabilitation Program) Standards 2002 (“the Disability Services Standards”), made pursuant to s 5A(1)(b) of the Disability Services Act, also came into effect on 1 July 2002. They include the following:

Standard 9: Employment conditions

Each person with a disability enjoys working conditions comparable to those of the general workforce.

KPI 9.1 The service provider ensures that people with a disability, placed in open or supported employment, receive wages according to the relevant award, order or industrial agreement (if any) (consistent with legislation). A wage must not have been reduced, or be reduced, because of award exemptions or incapacity to pay or similar reasons and, if a person is unable to work at full productive capacity due to a disability, the service provider is to ensure that a pro-rata wage based on an award, order or industrial agreement is paid. This pro-rata wage must be determined through a transparent assessment tool or process, such as Supported Wage System (SWS), or tools that comply with the criteria referred to in the Guide to Good Practice Wage Determination including:

• compliance with relevant legislation;

• validity;

• reliability;

• wage outcome; and

• practical application of the tool.

KPI 9.2 The service provider ensures that, when people with a disability are placed in employment, their conditions of employment are consistent with general workplace norms and relevant Commonwealth and State legislation.

KPI 9.3 The service provider ensures that, when people with a disability are placed and supported in employment, they, and if appropriate, their guardians and advocates, are informed of how wages and conditions are determined and the consequences of this.

Standard 10: Service recipient training and support

The employment opportunities of each person with a disability are optimised by effective and relevant training and support.

KPI 10.1 The service provider provides or facilitates access to relevant training and support programs that are consistent with the employment goals and opportunities of each service recipient.

52 In the second half of 2002, after consultation with Business Services and employees, HOI produced a draft of the BSWAT. This draft was then subjected to a trial over an eight week period, involving 83 participants at 19 sites operated by 13 organisations, a variety of industries, a variety of disabilities and a range of needs. As a result of the trial, the draft wage tool was revised. The revised wage tool was then subjected to some further testing. In December 2002, HOI produced a report, designated as a final report, entitled “Wage Tool for Business Services”. This contained the first published form of the BSWAT. In relation to the further testing of the draft, the report noted that, on average, SWS assessments would generate higher wage rates than the BSWAT. The report said:

Again, this information highlights the value of the hybrid assessment system. If solely competency based, it may be inferred that those with an intellectual disability (who may be highly productive) would be disadvantaged, whilst a solely productivity-based assessment may disadvantage those with a physical disability (who may be highly competent). In this context, the hybrid system recognises or ‘rewards’ the strengths of the individual being assessed.

The report recommended that the revised wage tool be implemented by the Department of Family and Community Services in 2003. It also recommended that the implementation be supported by an extended trial.

53 On 11 December 2002, the AIRC made the Australian Liquor Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union Supported Employment (Business Enterprises) (Roping in No 2) Award 2002, which made Coffs Harbour Challenge and two other organisations parties to the 2001 Award.

54 HOI produced two further reports, in April 2003 and May 2003 respectively, detailing the results of further trialling of the BSWAT. In addition, Evolution Research (a consultancy operated by Daniel Cox and Richard Giles) and Marshall Consulting became involved in testing, evaluating and developing the wage assessment tool. On 18 May 2003, Daniel Cox (who was also a principal of HOI) produced a report entitled “Rationale for Mathematical Formula Underpinning the Wage Tool”. The report defended the approach of giving productivity and competency each a weighting of 50%. It also defended the adoption of eight units of competency and the manner in which those competencies are assessed in the BSWAT.

55 In June 2003, HOI produced a short report entitled “Modelling Wage Impacts of the Revised Wage Assessment Tool”, which sought to demonstrate the effects of changes in the weighting between competency and productivity on wage outcomes. Also in June 2003, Marshall Consulting produced a report entitled “Technical Aspects of the Proposed Business Services Wage Assessment Tool (BSWAT)”. The report said:

It is clear from a scan of current arbitral decision-making and job analysis practice that in fundamental terms a hybrid methodology such as that underpinning BSWAT is in tune with modern wage fixing principles.

Marshall Consulting drew attention to the difficulty disabled workers might have in establishing their competency when tested by the “all or nothing” method, and recommended that consideration be given to looking into a more detailed system of assessment of elements of competency. Marshall Consulting favoured the retention of competency assessments, subject to the possibility of understatement of an employee’s overall capacities, due to the “all or nothing” method of assessment.

56 Also in June 2003, Evolution Research produced a report entitled “Business Services Wage Assessment Modelling and Competency Matching”. The report expressed the view that the assessment of four industry-specific competencies and four core units of competency represented a meaningful evaluation of a reasonable range and scope of work, and provided a fair comparison between Business Services and open employment settings. It also concluded that assessment of eight units of competency set reasonable expectations of a worker earning a full award rate. The report dealt with a number of issues associated with competency selection and assessment it had identified in the course of preparing the report, and made recommendations as to how these issues should be dealt with.

57 In July 2003, Marshall Consulting produced a report entitled “Testing of the Proposed Business Services Wage Assessment Tool Further Report on Job Analyses, Competencies and Wage Outcomes”. The report referred to difficulties with the identification of the relevant competencies, their pitch and number. It said that these difficulties were related to the assessors’ degree of familiarity with the AQTF system, overlap between competencies, difficulty in determining the level of a competency unit and problems with ANTA’s website and search engine. It recommended enhanced training of assessors and ongoing quality assurance procedures. With qualifications as to enhanced procedures, the report supported the release of BSWAT in its then current form.

58 In a document dated 28 January 2004, Kairsty Wilson on behalf of DEAC and Paul Cain on behalf of the National Council on Intellectual Disability (“NCID”) made a joint written submission to the AIRC in relation to its safety net review, as part of the 2004 Living Wage Case. The submission advocated the adoption of the supported wage model clause in all awards and agreements. The result would be the use of the SWS in Business Services as well as in open employment. The submission made criticisms of BSWAT. In particular, it identified detriment to workers who have less than four competencies associated with their jobs and the “all or nothing” assessment of competencies.

59 By an application dated 13 September 2004, the LHMU applied to the AIRC to vary the 2001 Award. The proposed variations included deleting cl 14.4.1 and inserting in its stead:

The rate assessed for that employee in accordance with the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool, or tool with an equivalent or better wages outcome, assessed objectively and transparently.

The application also proposed inserting cl 14.4.4:

No employee shall have their hourly rate of pay reduced by virtue of the introduction into the Award of the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool.

The grounds of the application described the BSWAT as providing a fair and transparent wage assessment and as conforming fully with the requirements of Standard 9 of the Disability Services Standards.

60 At some time in 2005, the Department of Family and Community Services produced a document entitled “Business Services Wage Assessment Tool Post-Implementation Review Consultation Paper”. This document described its purpose as “to outline the development and implementation of the BSWAT and to form the basis for post implementation review feedback.” The issues dealt with in the paper were “whether the original business driver for the development of the tool has been met”, “whether the project objectives for the BSWAT were achieved”, “delivery issues that may have emerged during the implementation of the BSWAT and whether they continue to impact” and “how to ensure the tool can continue to be delivered consistently, effectively and efficiently”.

61 On 16 February 2005, Jenny Pearson & Associates Pty Ltd (“Pearson”) produced for the Department of Family and Community Services a report entitled “Analysis of Wage Assessment Tools used by Business Services”. The report examined 10 wage assessment tools used by Business Services, including BSWAT, but not including SWS. The report was designed to assist with consideration of the LHMU application to vary the 2001 Award. Pearson found that, when compared with the BSWAT, the other nine wage assessment tools it examined had a greater focus on competency assessment, with the exception of one productivity-based tool. It also found that all of the tools reviewed in the report satisfied the Good Practice Guide to Wage Determination criteria.

62 In March 2005, Evolution Research produced a report for the Department of Family and Community Services, concerning consultation with Business Services as part of a research project. The report set out a number of issues raised by Business Services about the BSWAT, including both productivity-related and competency-related issues. The report referred to a diversity of opinion regarding the BSWAT, illustrated by the fact that many comments contradicted those by others in the Business Services sector.

63 Mr Nojin’s first wage assessment using BSWAT occurred at this point in the development of BSWAT.

64 While the application of the LHMU to vary the 2001 Award was pending, the AIRC established a Disability Sector National Consultative Council, in an endeavour to bring together parties interested in the employment of disabled persons, particularly in Business Services, to see if common ground could be reached. When the application came to be heard on 27 June 2005, the variations sought by the LHMU were supported by the Victorian Employers Chamber of Commerce and Industry, two specific employers (one being Coffs Harbour Challenge), ACROD, the Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, Australian Parent Advocacy and the ACTU. Only DEAC and NCID opposed the proposed variations and contended that the SWS should be the only approved wage assessment tool. At the conclusion of the hearing, Commissioner Gay indicated his intention to vary the 2001 Award. Mr Nojin’s reassessment on 12 August 2005 was at this point in the development of the BSWAT. The decision of the AIRC was given on 19 August 2005. The AIRC changed the title of the 2001 Award to the Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Union Supported Employment Services Award 2005 (“the 2005 Award”). The AIRC also varied the terms to include a range of wage assessment tools then in operation, including the BSWAT. Those tools were listed in cl 14A.4 of the 2005 Award. Ten of the 11 tools listed were those reviewed in the Pearson report (see [61] above.) Clause 14A.4 contained the following:

It is desirable that a wage assessment tool sought to be included in this award satisfy disability services standard 9 (Standard 9) and relevant key performance indicators as determined or approved under section 5A of the Disability Services Act 1986 (DSA KPI’s) as amended from time to time. The wage assessment tools described in this clause satisfy Standard 9 and the DSA KPI’s.

65 In a report dated 12 April 2006, entitled “Analysis of Wage Assessment Tools used by Business Services”, Pearson informed the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (as it was by then called) of the results of an examination of 22 wage assessment tools used by Business Services. Pearson mentioned the use of independent external assessors for the BSWAT and the use of an interview process, with oral questions, to determine core competencies, with some input from supervisors’ observations. The report then said:

In general terms, the other wage assessment tools and processes tend to:

• use internal staff to collect assessment data (all have a review process and most also use multiple assessor input to control for personal bias, etc);

• have a greater focus on competency assessment (with the exception of one productivity-based tool);

• have a three month or longer period for competency data collection; and

• use observation and performance as the main methods of assessing competency, rather than employee interview.

The 22 wage assessment tools examined in the April 2006 Pearson report included those examined in the previous Pearson report. Of the additional tools tested, only one involved assessment of productivity only, two involved assessment on the basis of competency only, and the remaining tools were hybrid assessment tools.

66 On 6 October 2006, the Australian Fair Pay Commission (“AFPC”) delivered its Wage-Setting Decision No. 1 2006. The decision contained detailed provisions for special minimum wage levels for disabled people. Section H of the decision operated to vary the pay scales derived from the 2005 Award, by including 11 additional wage assessment tools. In all, 22 wage assessment tools were approved, being the 22 tools examined in the April 2006 Pearson report. Because the AFPC was fixing minimum wages without regard to whether they were paid by or to parties bound by awards, the inclusion of BSWAT among the approved wage assessment tools gave BSWAT a potentially wider application.

67 It was at this stage of the development of BSWAT that Mr Prior’s initial assessment on 6 February 2007 took place.

68 In its Australian Government Disability Services Census 2007, the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs reported as follows:

At 29 June 2007, the wages of supported employment service consumers were determined using a range of wage assessment tools based on the consumer’s productivity, competency or both productivity and competency. Productivity-based wage assessment tools measure the output of consumers against an established benchmark, i.e. the co-worker without a disability. Competency-based wage assessment tools measure the work performance of consumers against set criteria (such as knowledge, understanding and skills) to a defined standard or benchmark. Hybrid wage assessment tools measure both productivity and competency (FaCS 2004).

Figure 4.43 shows the method used to determine the wages of consumers in the supported employment sector. Notably, the vast majority of supported employment service consumers had their wages determined using hybrid wage assessment tools, some 77.4% (13,797). The most common of these tools are the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool (BSWAT) and the Greenacres Wage Assessment Tool, which were used to determine the wages of 37.0% (6,590) and 18.6% (3,323) of all consumers respectively.

A further 9.7% (1,727) of supported employment service consumers had their wages determined using productivity-based wage assessment tools. The most common of these tools is the Supported Wage System wage assessment tool, which was used to determine the wages of 9.3% (1,657) of all consumers. This tool is also used by employers in the open labour market. A small percentage (4.6% or 811) of consumers had their wages determined using competency-based wage assessment tools. The remaining consumers (8.4% or 1,492) had their wages determined using other wage assessment tools.

69 On 28 August 2007, in its Wage-Setting Decision 8/2007, the AFPC determined pay and classification scales for employees with a disability. Schedule 3 again listed 22 wage assessment tools, the first of which was BSWAT.

70 In January 2008, Evolution Research produced a quality assurance report entitled “Business Service Wage Assessment Tool - Demonstration Phase”. The report concluded that BSWAT “is a fair, valid, reliable and robust instrument to determine pro-rata wages within a Business Service setting.” It also found that BSWAT was applicable in the majority of Business Services, across a range of disability and industry types, and that CRS had proven that it had the required infrastructure and skill set to implement BSWAT in a timely, accurate and efficient manner. The report made a number of recommendations.

71 In its Wage-Setting Decision 1/2008, the AFPC made adjustments to the pay scales applicable for disabled employees, including those in Business Services. The decision added nine designated wages tools to the 22 already in Sch 3 of the previous decision.

72 It was at this point in the development of the BSWAT that Mr Prior’s reassessment took place on 8-9 May 2008.

73 On 5 May 2009, in its Wage-Setting Decision 1/2009, the AFPC deleted from Sch 3 of the Special Business Services Pay Scale a wage assessment tool known as Paraquad Wage Assessment Tool. This deletion was made on the ground that one aspect of that assessment tool led to “unacceptable wage outcomes”.

Discrimination by requirement or condition - compliance

74 The Court’s task in these cases is not to determine whether either Mr Nojin or Mr Prior ought to have been entitled to wages at rates higher than those assessed using the BSWAT. The question is whether, by procuring the assessments of their wages by means of the BSWAT, Coffs Harbour Challenge and Stawell Intertwine did anything that amounts to unlawful discrimination within the terms of the Disability Discrimination Act in relation to Mr Nojin and Mr Prior respectively. Fundamental to the cases put on behalf of the applicants in these proceedings is the proposition that they were required to comply with requirements or conditions with which a substantially higher proportion of persons without their disabilities complied or were able to comply, but with which they were not able to comply. Each of these allegations was denied by the respondents, but there was little focus on the issue of compliance with requirements or conditions during the trial.

75 There can be little doubt that the BSWAT is a discriminatory method of assessment, and is itself part of a discriminatory scheme. To pay a lower level of remuneration to a disabled person than would be paid to a non-disabled person, because of the disabled person’s disability, would undoubtedly constitute less favourable treatment. In order to determine whether such less favourable treatment constituted discrimination according to the definition in s 5 of the Disability Discrimination Act, the focus would be on whether the circumstances were the same or not materially different. In the present cases, no allegation is made of discrimination by less favourable treatment. The implicit assumption is that wage assessment taking account of the different capacities of employees, resulting from their different kinds and degrees of disabilities, is appropriate. BSWAT is a method of assessment designed to discriminate between employees according to their different capacities, which may depend upon their different kinds and degrees of disabilities. The use of BSWAT is intended to provide an answer as to where a particular person fits into a pay scale based on percentages of a rate of pay for a non-disabled worker. Some disabled people will do better than others. In that sense, BSWAT is discriminatory. Again, no complaint by reference to s 5 of the Disability Discrimination Act is made about that kind of discrimination. The implicit assumption appears to be that it would be inappropriate to pay all disabled persons at the same rate of pay, because some are capable of working harder, longer, more efficiently and more productively than others.