FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1169

| Citation: | Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1169 | |

| Parties: | ||

| File number: | WAD 132 of 2007 | |

| Judge: | BARKER J | |

| Date of judgment: | 29 October 2010 | |

| Catchwords: | PATENTS – innovation patents – infringement – whether respondents took each and every essential integer of the first applicant’s patent – meaning of the terms “device”, “orientation data”, “time interval” and “predetermined time interval” in the patent claims – whether alleged infringing equipment was a material variation on the invention defined in the patent – relevance of Improver questions to claim construction – held: no infringement PATENTS – innovation patents – invalidity – whether patent was invalid for lack of fair basis as required by s 40(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) – real and reasonably clear disclosure – consistory clauses – held: no invalidity | |

| Legislation: | Patents Act 1990 (Cth) s 40(3), s 120 | |

| Cases cited: | Aktiebolaget Hassle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59; (2002) 212 CLR 411 AMI Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Bade Medical Institute (Aust) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2009] FCA 1437; (2009) 262 ALR 458 Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier (No 2) [2009] FCA 1019; (2009) 83 IPR 42 Aspirating IP Ltd v Vision Systems Ltd [2010] FCA 1061 Austal Ships Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag [2005] FCA 805; (2005) 66 IPR 420 BEST Australia Ltd v Aquagas Marketing Pty Ltd (1988) 12 IPR 143 Bitech Engineering v Garth Living Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 75; (2010) 86 IPR 468; Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 Dura-Post (Australia) Pty Ltd v Delnorth Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 81; (2009) 177 FCR 239 EMI v Lissen Ltd (1938) 56 RPC 23 Foxtel Management Pty Ltd v Mod Shop Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 463; (2007) 165 FCR 149 Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Ltd v Gambro Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 220; (2005) 224 ALR 168 H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 70; (2009) 177 FCR 151 Improver Corporation v Remington Consumer Products Ltd [1990] FSR 181 Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 8; (2001) 207 CLR 1 Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoeschst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] 1 All ER 667; (2004) 64 IPR 444 Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 58; (2004) 217 CLR 274 Olin Corporation v Super Cartridge Co Pty Ltd [1977] HCA 23; (1977) 180 CLR 236 Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co [2005] FCAFC 224; (2005) 225 ALR 416 Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd (1982) 59 FLR 37 Re Raychem Corp's Patents [1998] RPC 31 Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 980; (2000) 177 ALR 231 Sachtler GmbH & Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 788; (2005) 221 ALR 373 Seafood Innovations Pty Ltd v Richard Bass Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 723 The "Koursk" [1924] P 140 Thompson v Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd [1996] HCA 38; (1996) 186 CLR 574 Uniline Australia Ltd v Sbriggs Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 222; (2009) 81 IPR 42 Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Cooper [2005] FCA 972; (2005) 150 FCR 1 Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc [2001] FCA 445; (2001) 113 FCR 110 | |

|

|

| |

| Dates of hearing: | 19 – 23, 27 and 29 April 2010 and 26 October 2010 | |

|

|

| |

| Date of last submissions: | 26 October 2010 | |

|

|

| |

| Place: | Perth | |

|

|

| |

| Division: | GENERAL DIVISION | |

|

|

| |

| Category: | Catchwords | |

|

|

| |

| Number of paragraphs: | 203 | |

|

|

| |

| Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr RJ Webb SC and Dr CN Kendall | |

|

|

| |

| Solicitor for the Applicants: | Griffith Hack | |

|

|

| |

| Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr BJ Hess SC, Mr DW Thompson and Dr LJ Duncan | |

|

|

| |

| Solicitor for the Respondents: | Arns and Associates | |

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

| GENERAL DIVISION | WAD 132 of 2007 |

| BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN MUD COMPANY PTY LTD (ACN 009 283 416) First Applicant

IMDEX LIMITED (ACN 008 947 813) Second Applicant

REFLEX INSTRUMENTS ASIA PACIFIC PTY LTD (ACN 123 204 191) Third Applicant

|

| AND: | CORETELL PTY LTD (ACN 119 188 493) First Respondent

MINCREST HOLDINGS PTY LTD (TRADING AS CAMTEQ INSTRUMENT SERVICES) (ACN 068 672 471) Second Respondent

|

| JUDGE: | BARKER J |

| DATE: | 29 OCTOBER 2010 |

| PLACE: | PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

patent infringement and related claims

1 In this proceeding, the primary application is brought pursuant to s 120 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act), for alleged patent infringement by the respondents of an innovation patent belonging to Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd (the first applicant). The claim is also for misrepresentational conduct under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) consequent on that infringement.

2 The respondents deny the claims and cross-claim for relief in respect of unjustified threats and invalidity of the patent.

3 By consent orders of French J made 19 June 2008, the parties agreed that the issue of liability for infringement should be split from the question of the quantum of damages that may arise subsequent to any finding on liability. The hearing before me proceeded on this basis and was limited to the issue of liability. Consequently, these reasons are similarly limited.

Issues

4 The first applicant is the registered owner of Australian Innovation Patent 2006100113 in relation to an invention entitled “Core Sample Orientation” (Patent). The Patent has a priority date of 3 September 2004 and was certified on 20 July 2006. The invention described is used for determining the down-hole orientation of core samples taken during drilling operations, typically in the mining industry.

5 The second and third applicants enjoy licences to use the invention and their roles are not relevant to the issue of liability.

6 The applicants’ claim that the respondents (Coretell and Mincrest respectively), as joint tortfeasors, have infringed and are continuing to infringe the Patent by making, hiring and selling or otherwise disposing of two core orientation tools that embody features which, the applicants allege, are within the scope of the Patent’s monopoly. The two allegedly infringing core orientation tools were referred to by the parties as the “Camteq tool” and the “ORIshot tool”.

7 When the applicants commenced these proceedings in July 2007 the respondents had only dealt in the Camteq tool. However, in early 2009, they commenced dealing in the ORIshot tool as an alternative to the Camteq tool. The parties agree that there is no relevant difference between the two tools such that if the Camteq tool infringes the Patent then so too does the ORIshot tool. This was reflected at trial with the parties referring to these tools collectively as the “Coretell Equipment”, after Coretell, the first respondent. These reasons adopt that convention.

8 The respondents deny that the Coretell Equipment infringes the Patent, deny that they are joint tortfeasors and say further that the Patent is invalid because its claims are not fairly based on the specification as required by s 40(3) of the Act. The respondents similarly allege that the Patent fails to define the invention as required by s 40(2)(c) but accept that this ground stands or falls with the claim under s 40(3). The applicants deny that the Patent is invalid and point to the consistory clauses in the Patent to support this argument. They say that it is clear from a reading of the Patent as a whole that the claims are fairly based on the specification.

9 The respondents, if successful, by cross-claim seek relief in respect of unjustified threats pursuant to s 128 of the Act. At trial the applicants conceded that if the respondents are successful in their defence to infringement, or cross claim for invalidity, then the unjustified threats action will be made out and the respondents will be entitled to this relief.

10 In essence, the proceeding raises three main issues:

1. Whether the Coretell Equipment infringes the Patent.

2. Whether the Patent is invalid.

3. Whether the respondents, if liable for infringement, are joint tortfeasors.

infringement

11 Section 13 of the Act defines the patentee’s monopoly. Relevantly, s 13(1) provides:

Subject to this Act, a patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to exploit the invention

12 “Exploit” is defined in the dictionary that forms Schedule 1 to the Act:

exploit, in relation to an invention, includes:

(a) where the invention is a product—make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things; or

(b) where the invention is a method or process—use the method or process or do any act mentioned in paragraph (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

13 Section 117 relevantly extends conduct that is infringing by providing:

117 Infringement by supply of products

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

(a) if the product is capable of only one reasonable use, having regard to its nature or design—that use; or

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product—any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; or

(c) in any case—the use of the product in accordance with any instructions for the use of the product, or any inducement to use the product, given to the person by the supplier or contained in an advertisement published by or with the authority of the supplier.

14 The respondents have admitted, in their amended defence and cross claim dated 24 November 2009, at least one act which would constitute infringement if the Coretell Equipment is found to be within the Patent monopoly. Therefore, the only relevant question for the Court in respect of infringement is whether the invention in the Patent, as claimed, encompasses the Coretell Equipment.

Principles of construction

15 The principles of claim construction are not generally in dispute between the parties. In the judgment of Bennett J (with whom Middleton J agreed) in H Lundbeck v Alphafarm & Anor [2009] FCAFC 70; (2009) 177 FCR 151 (Lundbeck), at [118], her Honour noted that the “end point” is that:

the words in a claim should be read through the eyes of the skilled addressee in the context in which they appear. Words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification … This applies to words used in the claims. As Emmett J observed …, the construction of a specification, including the claims, is ultimately a question of law for the Court.

16 Recent summaries of the relevant principles, with references to appropriate authority, by which I am guided, may be found in: Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron and Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [45]; Uniline Australia Ltd v SBriggs Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 222 (Uniline), Greenwood J at [42] – [47]; Aspirating IP Limited v Vision Systems Limited [2010] FCA 1061, Besanko J at [107]-[111] (Aspirating).

17 In Lundbeck, Bennett J emphasised that the claims are part of the specification, and that while the claims define the monopoly claimed in the words of the patentee’s choosing, the specification should be read as a whole. Justice Bennett particularly noted that those who attempt to elevate the “purposive construction” utilised by Lord Diplock in Catnic Components Limited v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 (Catnic)should understand the application of that approach to construction as explained by Lord Hoffman in Kirin–Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] 1 ALL ER 667; (2004) 64 IPR 444 at [33] – [34] (Kirin–Amgen).

18 In making this point about purposive construction, Bennett J also referred to her earlier decision in Sachtler Gmb H & Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 788; (2005) 221 ALR 373 (Sachtler) at [42]. There her Honour noted that, while a patent should be given a purposive construction, that approach does not involve extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. For this purpose, the language chosen is usually of critical importance.

19 Her Honour there also stated that purposive construction – permitting consideration of whether the person skilled in the art would understand that a variant that does not strictly comply with the particular descriptive word used in the claim may still fall within the monopoly – does not arise where the variant would in fact have a material effect upon the way the invention worked. I will return to this “material variation” point later, as it is raised by the parties in this proceeding.

20 The ultimate point of claim construction is to establish whether the respondents have exploited a product which possesses each and every one of the “essential integers” of each claim alleged to be infringed: Olin Corporation v Super Cartridge Co Pty Ltd [1977] HCA 23; (1977) 180 CLR 236 (Olin) at 246. In construing the claims the Court is not to have reference to the alleged infringing articles: Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc [2001] FCA 445; (2001) 113 FCR 110 at [21]. Rather, reference is to be had only to the words of the claims, keeping in mind that their primary aim is to limit and not to extend the monopoly; what is not claimed is disclaimed: EMI v Lissen Ltd (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 29 (EMI). Importantly, while it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of a monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by reference to other parts of the specification, where terms in a claim are unclear, then as noted above, those terms may be defined or clarified by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 8; (2001) 207 CLR 1; (Kimberly-Clark) at [15].

21 In this case, because the respondents submit the claims should be read literally, the applicants make a particular point of emphasising that the Court should construe the claims in a purposive manner following the classic statement of this principle by Diplock LJ in Catnic at 242 – 243. It is useful, at this point and for later purposes, to note exactly what his Lordship there stated:

a patent specification is a unilateral statement by the patentee, in words of his own choosing, addressed to those likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of his invention (i.e. ‘skilled in the art’), by which he informs them what he claims to the essential features of the new product or process for which the letters patent grant him a monopoly. It is those features only that he claims to be essential that constitute the so-called ‘pith and marrow’ of the claim. A patent specification should be given a purposive construction rather than a purely literal one derived from applying to it the kind of meticulous verbal analysis in which lawyers are too often tempted by their training to indulge. The question in each case is: whether persons with practical knowledge and experience of this kind of work in which the invention was intended to be used, would understand that strict compliance with a particular descriptive word or phrase appearing in a claim was intended by the patentee to be an essential requirement of the invention so that any variant would fall outside the monopoly claimed, even though it could have no material effect upon the way the invention worked. (Emphasis supplied. However, the emphasis on “any” is in the original)

Lord Diplock, at 243, immediately went on to add this:

The question, of course, does not arise where the variant would in fact have a material effect upon the way the invention worked. Nor does it arise unless at the date of publication of the specification it would be obvious to the informed reader that this was so. Where it is not obvious, in the light of then-existing knowledge, the reader is entitled to assume that the patentee thought at the time of the specification that he had good reason for limiting his monopoly so strictly and had intended to do so, even though subsequent work by him or others in the field of the invention might show the limitation to have been unnecessary. It is to be answered in the negative only when it would be apparent to any reader skilled in the art that a particular descriptive word or phrase used in a claim cannot have been intended by a patentee, who was also skilled in the art, to exclude minor variants, which, to the knowledge of both him and the readers to whom the patent was addressed could have no material effect upon the way in which the invention worked. (Emphasis supplied)

22 In taking a purposive approach to construction, the applicants submit the application of the “Improver questions”, as formulated by Hoffman J in Improver Corporation v Remington Consumer Products Limited [1990] FSR 181 (Improver) at 188-189, are likely to prove helpful. In Improver, his Lordship stated the three questions in this way:

(1) Does the variant have a material effect upon the way the invention works? If yes, the variant is outside the claim, if no –

(2) Would this (i.e. that the variant had not material effect) have been obvious at the date of publication of the patent to a reader skilled in the art. If no, the variant is outside the claim. If yes –

(3) Would the reader skilled in the art nevertheless have understood from the language of the claim that the patent he intended that strict compliance with the primary meaning was an essential requirement to the invention. If yes, the variant is outside the claim.

1. On the other hand, a negative answer to the last question would lead to the conclusion that the patentee was intending the word or phrase to have not a literal but a federative meaning (the figure being a form of synecdoche or metonymy) denoting a class of things which included the variant in the literal meaning. The latter being perhaps the most perfect, best known or striking example of the class.

23 In Kirin-Amgen, Lord Hoffman referred to what Lord Diplock had said in Catnic about purposive construction and what he had said in Improver in relation to it by way of guidance. At [52], his Lordship noted that, on the whole, judges appeared to have been comfortable with the results of these questions, although some of the cases had exposed the limitations of the method. He then emphasised that the questions were only guidelines, more useful in some cases than in others; designed to help to decide, in appropriate cases, what the skilled person would have understood the patentee to mean.

24 In Sachtler, Bennett J took these observations of Lord Hoffman into account in observing, at [67], that the Improver questions are not helpful “other than, perhaps, as a ‘check’ on the conclusion reached as to the characterisation of essential or inessential integers present in the allegedly infringing article”. In Uniline, at [112], Greenwood J considered the questions are useful as a test in assisting claim construction but noted that they do not supplant that task.

25 I accept it is correct to take a purposive approach to claim construction, but I am mindful that it is not intended to widen the scope of construction to embrace alleged infringing articles that would otherwise be outside the plain words of a claim as read by a person skilled in the relevant art. The purposive approach is concerned with identifying the essential features of a claim and construing them from the perspective of a person skilled in the art. These features, as the Full Court of this Court noted in Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd (1982) 59 FLR 37 (Populin), at 43, “are to be determined not as a matter of abstract uninformed construction but by a common-sense assessment of what the words used convey in the context of then-existing published knowledge”.

26 It is clear then, from the authorities, that the term “purposive” is not intended to widen the ambit of claim construction. Instead, as this Court has repeatedly recognised, purposive construction, as explained by Diplock LJ in Catnic, is directed at ensuring the Court undertakes the task of claim construction from the perspective of a person skilled in the relevant art before the priority date and not from the vantage of an uninformed layperson or linguistically pedantic lawyer.

27 It is also important to understand the point made by Lord Diplock in Catnic, which is emphasised by the first Improver question, that the question whether strict compliance with a particular descriptive word or phrase was intended by the patentee to be an essential requirement of the invention so that any variant would fall outside the monopoly claimed, does not arise where the variant would in fact have a material effect upon the way the invention worked. When his Lordship used the expression “upon the way the invention worked”, in the context in which this discussion took place, I understand his Lordship to have meant: the way the invention worked by reference to its essential features described in the patent. That makes perfect sense, because if there is a material variation then the variant will work otherwise than by reference to the essential features described in the patent in issue.

The non-inventive person skilled in the art

28 In Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 225, Finkelstein J, at 237, explained the purpose of the non-inventive skilled addressee:

The proper construction of the specification is a matter of law. It is, however, a task that must be undertaken through the eyes of the person to whom the specification is directed… who may give expert evidence to inform the court what is the generally accepted meaning of technical terms and also to explain how things actually work.

29 The role of the skilled addressee is particularly important in these proceedings as the construction of the claims, and thus the scope of the Patent’s monopoly, turns on the meaning of several technical terms and phrases. I will turn to each of the terms and phrases in detail later.

30 In determining who fits the description of the non-inventive skilled addressee it important to identify and characterise the particular field of knowledge in which that person is skilled: Aktiebolaget Hassle v Alphafarm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59; (2002) 212 CLR 411 at [152].

31 It may be that the non-inventive skilled addressee is not, in fact, a single person but a hypothetical team of people: Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co [2005] FCAFC 224 at [288].

32 It is common ground that the relevant field in these proceedings is that concerned with the design, manufacture and operation of core sample orientation tools: respondents’ closing submissions at [13], [74]; applicants’ closing submissions at [33]-[34]. While the relevant field is agreed, the parties dispute the possible identity of the non-inventive skilled addressee.

33 There were five experts in these proceedings who reported on matters relating to infringement of the Patent. The applicants’ experts are Dr Roger William Marjoribanks, Professor James Philip Trevelyan and Dr Anton Kepic. The respondents’ experts are Dr Douglas Graham Myers and Dr Julian Vearncombe. All of the experts are well qualified. The respondents also called one non-expert, Mr Ashley Gordon Barker, designer of the Coretell Equipment.

34 Dr Marjoribanks and Dr Vearncombe gave evidence to explain the context of the patented invention (geological methods utilising drilled cores, and the orientation of those drilled cores). This evidence was not controversial and neither expert was put up as the relevantly non-inventive skilled addressee of the Patent. The remaining experts: Professor Trevelyan, Dr Kepic and Dr Myers, were each suggested as possible candidates for the mantle of non-inventive skilled addressee.

35 The applicants say that Professor Trevelyan is a relevantly skilled addressee. Professor Trevelyan is the Discipline Chair for Mechatronic Engineering at the University of Western Australia. He holds a Bachelor of Engineering with first class honours and a Masters of Engineering, both from the University of Western Australia. Professor Trevelyan’s own evidence is that a person skilled in the relevant art in these proceedings would have to have practical experience in the field of mechatronics as well as a practical understanding of the mining industry and core drilling: affidavit of James Philip Trevelyan dated 28 August 2008 at [32]-[35]; affidavit of James Philip Trevelyan dated 18 June 2009 at [74]-[81].

36 The respondents concede that the field of the invention, core sample orientation tools, could include, or overlap with, the discipline of mechatronic engineering. To this extent the respondents accept that Professor Trevelyan is a competent witness. However, the respondents say that Professor Trevelyan is inventive and therefore cannot be regarded as a non-inventive skilled addressee. The respondents supported this contention by tendering a schedule outlining the patenting activities of Professor Trevelyan (exhibit R10). Consequently, the respondents say that the Court should qualify the weight to be attributed to Professor Trevelyan’s evidence. However, the respondents accept and seek to rely on portions of the evidence of Professor Trevelyan adduced in cross-examination.

37 The applicants say that although Professor Trevelyan might himself be described as inventive this should not disqualify him from addressing the Court in relation to the Patent. Professor Trevelyan’s uncontested evidence is that as a professor of mechatronics he is required to work closely with and supervise his own students – many of whom work in the mining industry – and this gives him considerable insight into how a person skilled in the art would understand the Patent (transcript 147, 197). The applicants say that this information is relevant and assists the Court in construing the claims in the Patent.

38 I accept that Professor Trevelyan’s evidence is relevant to the issues in dispute in this proceeding and I accept that his evidence may go to what the non-inventive but skilled worker engaged in the design, manufacture or operation of core sample orientation tools would understand the Patent to mean. However, given the uncontested evidence that Professor Trevelyan is inventive, I do not accept that he himself is the non-inventive skilled addressee of the subject Patent.

39 The applicants alternatively contend that Dr Kepic is either the skilled addressee to whom the patent would be directed, or as close as you can get in this regard: applicants’ closing submissions at [148]. The applicants support this contention by saying that Dr Kepic has a PhD in geophysics and highly relevant industry experience: affidavit of Dr Anton Kepic sworn 29 August 2008 at [8], [32], [33], [35]-[38]. However, the problem with this submission is that it is somewhat circular. Dr Kepic is the only witness to suggest that a PhD is required of a skilled addressee in the field of this patent’s invention. Furthermore, only Dr Kepic considers geophysics as relevant to the field of the invention. In effect, Dr Kepic qualifies himself as the skilled addressee. For my part, I do not consider either of these requirements essential.

40 In response, the respondents say that at the priority date Dr Kepic had no experience in the field of core orientation tools, had not done any work in relation to such tools and was not aware of any of the prior art tools on the market. This submission is supported by Dr Kepic’s oral evidence during cross-examination. At transcript 358-359 the following exchange took place between Senior Counsel for the respondents and Dr Kepic:

In coming to the court and giving evidence, do you profess to have practising expertise in core orientation tools?---No.

No?---I do not have a practising expertise in core orientation tools.

All right. Did you ever have practising expertise in core orientation tools?---No.

Did you ever use such core use such core orientation tools?---I did not personally use

any core orientation tools. However, I was, if you will, nearby when such measurements were taken. Oriented core, in my experience, is uncommon. So whilst I’ve been around a number of drill rigs and inspected a lot of core as part of my exploration work and liaising with industry, I have not operated a core orientation tool in a practising manner because that’s just, simply, never been my function.

All right. Now, have you been on drilling sites I think you said nearby?---Yes.

Have you been on drilling sites when core orientation tool technology has been practised?---No.

No. So when you mean nearby what do you mean then?---Like, with in visual site of the rig.

All right. Well, were you part of the drilling team?---No.

41 Despite this, Dr Kepic gave evidence that he was very familiar with a category of items called “bore orientation tools” as at the priority date of the Patent: affidavit of Dr Anton Kepic sworn 18 June 2009 at [11]. Moreover, at [10] of that affidavit, Dr Kepic asserts that core orientation tools and bore orientation tools:

Are similar tools, in that they are both borehole tools concerned with orientation in a borehole environment, although they are aimed at orienting different things. Core orientation tools are concerned with orienting drill core (rock) retrieved from the ground during the diamond drilling process. Borehole orientation tools are concerned with orienting the borehole resulting from the drilling process. However, both types of tools are borehole tools that utilise geophysical properties and both are concerned with orientation, although they are directed at orienting different things. As such, in my opinion, there is no fundamental difference in the level of knowledge required to understand the two different devices.

42 During cross-examination, senior counsel for the respondents took Dr Kepic to these parts of his affidavit. At transcript 357, the following interchange is recorded:

Now, having regard to that evidence, I just want to ask you, doctor, were you aware before 2004 this is just a question of whether you do know or don’t know were you aware of a tool called a Reflex EMS tool?---I was not aware of that particular tool. There were a number of tools I was acquainted with in 99 but that one does not - - -

No, back to 2004?---No, I was not actively engaged in anything to do with core in 2004.

No, this is a bore hole orientation tool not a core tool?---The particular Reflex model

is not one I recall.

All right. Were you aware of a tool called a Reflex EZ tool?---Yes.

Thank you. And were you aware of a Reflex EZ Dip tool?---I cannot recall.

Thank you. And were you aware of a tool called a Flex It Smart tool? I think it was a camera?---No, I don t remember that particular brand. I do remember I was aware of a couple of tools that had film cameras installed in them for bore hole orientation.

Thank you?---But that particular model I’m not aware of. I don’t recall it.

43 I accept that Dr Kepic was familiar with some, but not all, bore orientation tools at the Patent’s priority date. While Dr Kepic did not have, and does not have, a practicising expertise in core orientation tools, I accept his evidence that those tools are similar to borehole orientation tools and that there is no fundamental difference in the knowledge required to understand the two. The respondents did not seek to challenge Dr Kepic’s evidence on this point.

44 Furthermore, the respondents’ expert Dr Myers conceded in cross-examination that Dr Kepic is very familiar with downhole instruments and has designed and built them in a professional capacity. Dr Myers also accepted that Dr Kepic has the skills required to develop the invention revealed in the Patent (transcript, 297). The applicants say this supports their contention that Dr Kepic is an example of the non-inventive skilled addressee of the Patent. I agree. While I do not accept that a PhD or an undergraduate degree in geophysics are necessary elements of the relevant skilled addressee, it is clear that the experience and skills that Dr Kepic had at the priority date were highly relevant to the invention disclosed in the Patent. I therefore find that Dr Kepic is a relevant non-inventive skilled addressee of the Patent. However, this finding does not exclude the possibility that other persons, or teams of people, may equally be non-inventive skilled addressees of the Patent.

45 In addition to contesting the appropriateness of Professor Trevelyan and Dr Kepic, the respondents say that Dr Myers is the only witness in these proceedings who could properly be considered a skilled addressee of the Patent.

46 Dr Myers, at the time of providing his affidavit evidence in these proceedings, was the program leader for computer systems engineering within the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering of Curtin University of Technology. Dr Myers holds a Bachelor of Engineering in Communications Engineering with honours, a Masters in Engineering, and a Doctorate of Philosophy, all obtained from the University of Western Australia. The respondents’ submit that Dr Myers has specific, relevant and appropriate experience in the field of the invention as set out in [21] of his affidavit dated 7 November 2008. However, in making this submission the respondents variously say that the field of the invention is computer engineering or electronic engineering, fields arguably narrower than the design, manufacture and operation of core sample orientation tools generally. I accept, though, that these more narrowly identified fields are relevant to, and overlapped by, the agreed field of the invention.

47 During cross-examination, counsel for the applicants took Dr Myers to [21] of his affidavit dated November 7 2008, and put a series of questions to him that sought to undermine Dr Myer’s self-assessment as the skilled addressee of the Patent. At transcript, 275, this is recorded:

And take a moment to read it if you need to, but you will recall that in that paragraph

you gave some evidence as to who you regard as the relevant skilled addressee of

this patent?---Yes.

You, there, give some evidence that you regard that person, that relevant person, as

being a person trained to undergraduate degree level in the computer science fair [field]; do you recall that?---Computer engineering.

Computer engineering, I’m terribly sorry?---Yes.

And, of course, that’s not a description of you, is it?---Yes.

Sorry?---Yes.

Aren’t you trained to doctorate level?---Yes. Sorry, you mean in the terms of

undergraduate?

Yes?---Yes, sorry. Yes.

So you don t regard yourself as a skilled addressee of this patent for this

purpose?---Yes, because as an academic it’s my duty to train potential engineers in this field.

I see. By that you mean to say that you regard yourself as able to speak from the position of a skilled addressee because, as an academic, you train such undergraduates?---Yes, our courses are approved by Engineers Australia under international convention for people to be qualified in the field, therefore we must be qualified appropriately to undertake these activities.

48 The respondents submit this challenge failed. I accept that submission.

49 The applicants say that despite this, Dr Myers’ own evidence is that a generalist or team of people, and not a specialist (such as he is), would be the best representative of a skilled addressee of this Patent. I accept that Dr Myers’ evidence reveals this, however it does so in the context of a person considering a design brief from a client. In my view, Dr Myers’ evidence on this point, at transcript 277-278, was responsive to questions put by counsel concerning how relevantly skilled people would design and produce a product for commercial exploitation. The answers Dr Myers gave in cross-examination reveal a practical understanding of how a product or invention would be developed in consultation with a client. In my view, this evidence was given by Dr Myers in a very general context. For instance, at transcript 278, Dr Myers explains that “the trouble with a lot of development situations is the client really doesn’t know what it is they want”. Clearly, Dr Myers was speaking generally and commercially, as led by counsel, and not with particular reference to the Patent claims.

50 In the end, I do not think this evidence can support the view that a generalist or team of persons would be best placed to produce the invention disclosed in the Patent. In any event, even if the evidence does go this far, it does not negative the respondents’ contention that Dr Myers, even as a specialist computer engineer, could not perform similarly. Put another way, it does not assist the applicants’ argument that Dr Myers is not a relevantly skilled non-inventive addressee of the Patent.

51 I therefore find that Dr Myers, along with Dr Kepic, are relevantly skilled non-inventive addressees of the Patent who are entitled to give evidence as to how the Patent would be read by such a person.

Construction of the Patent

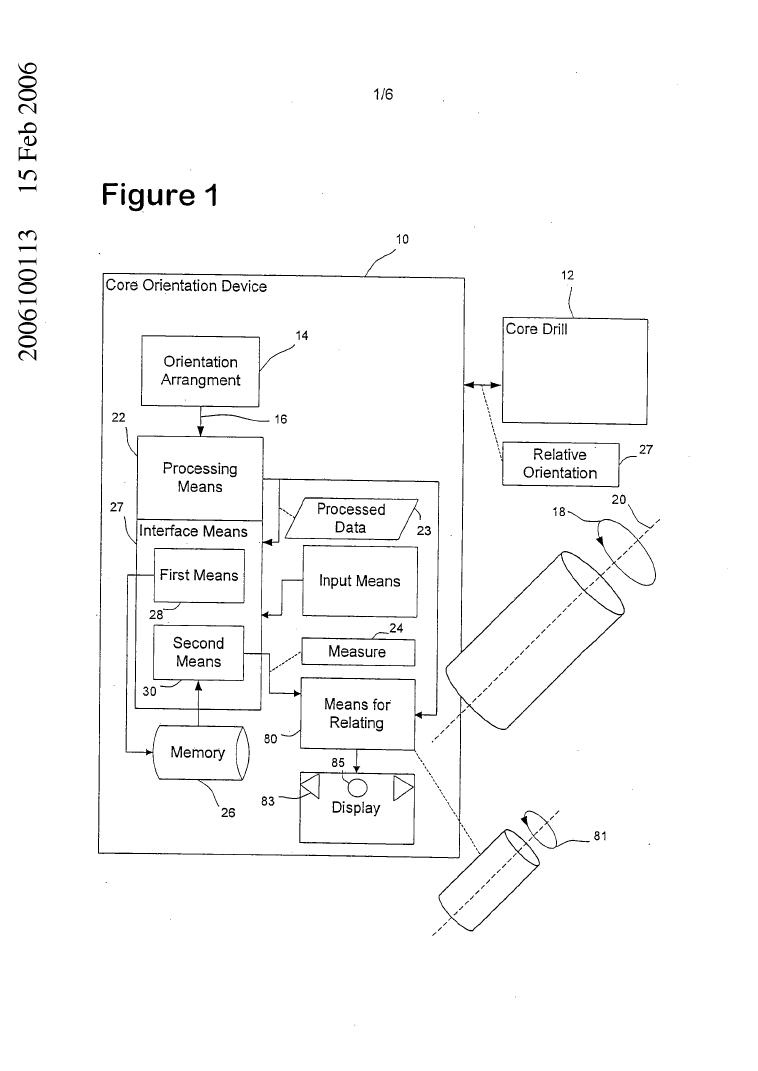

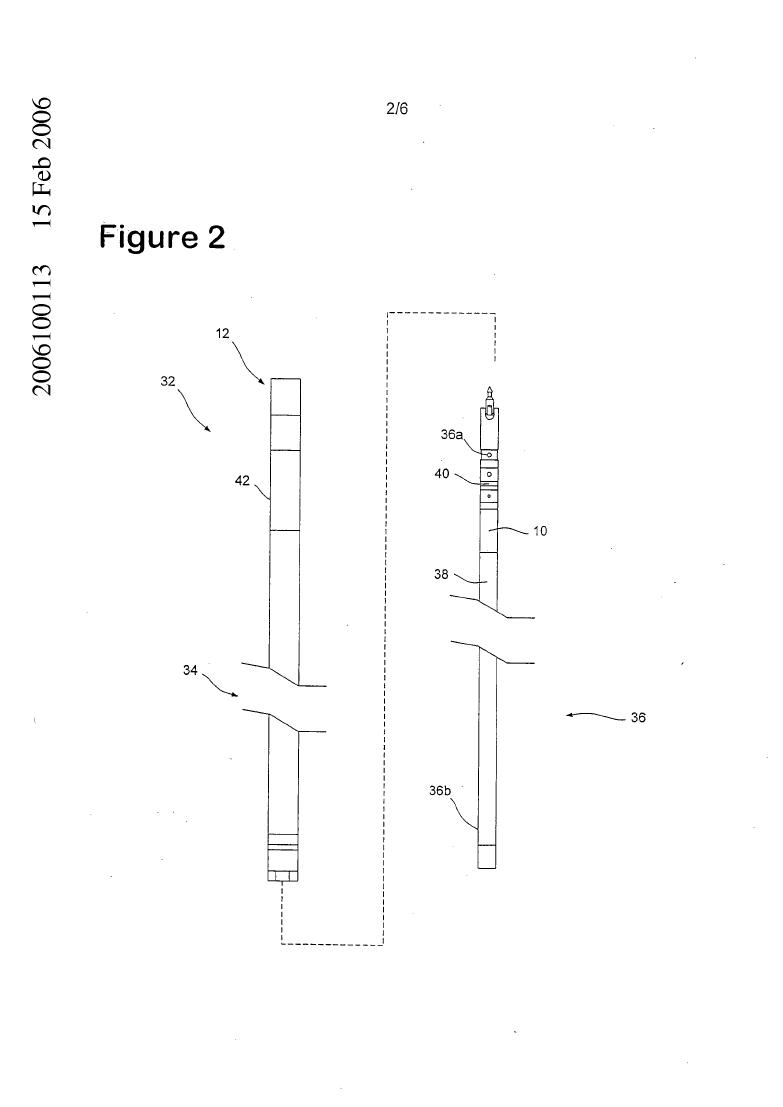

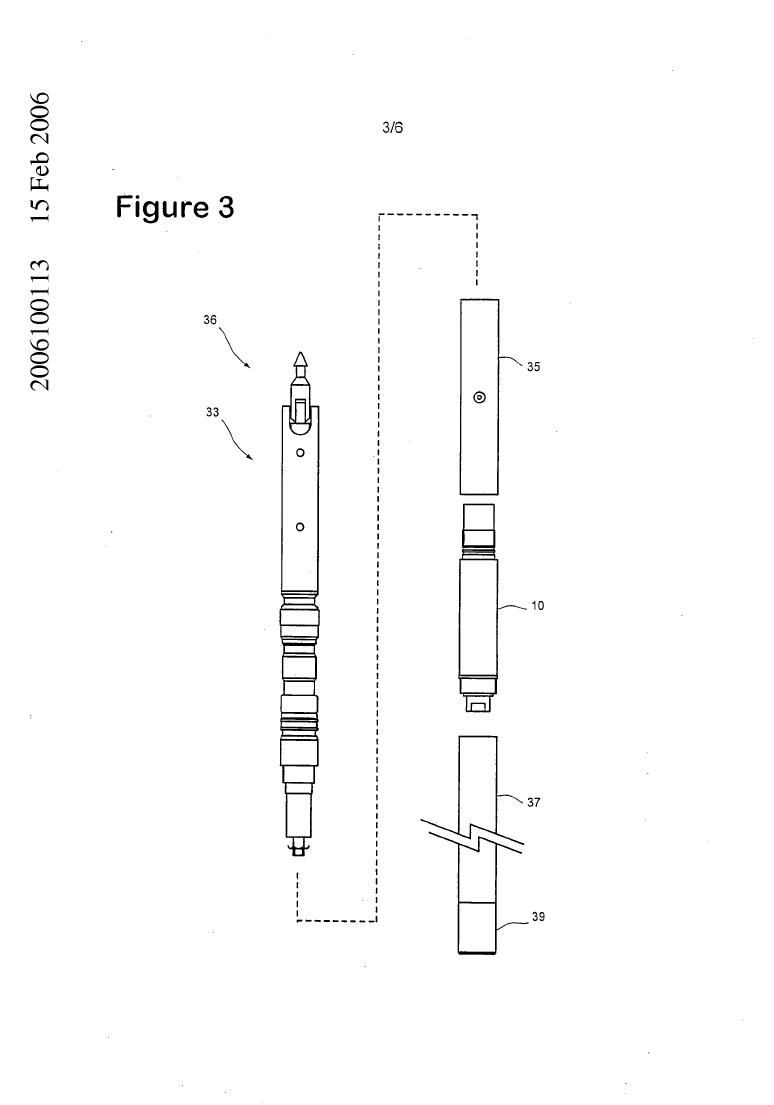

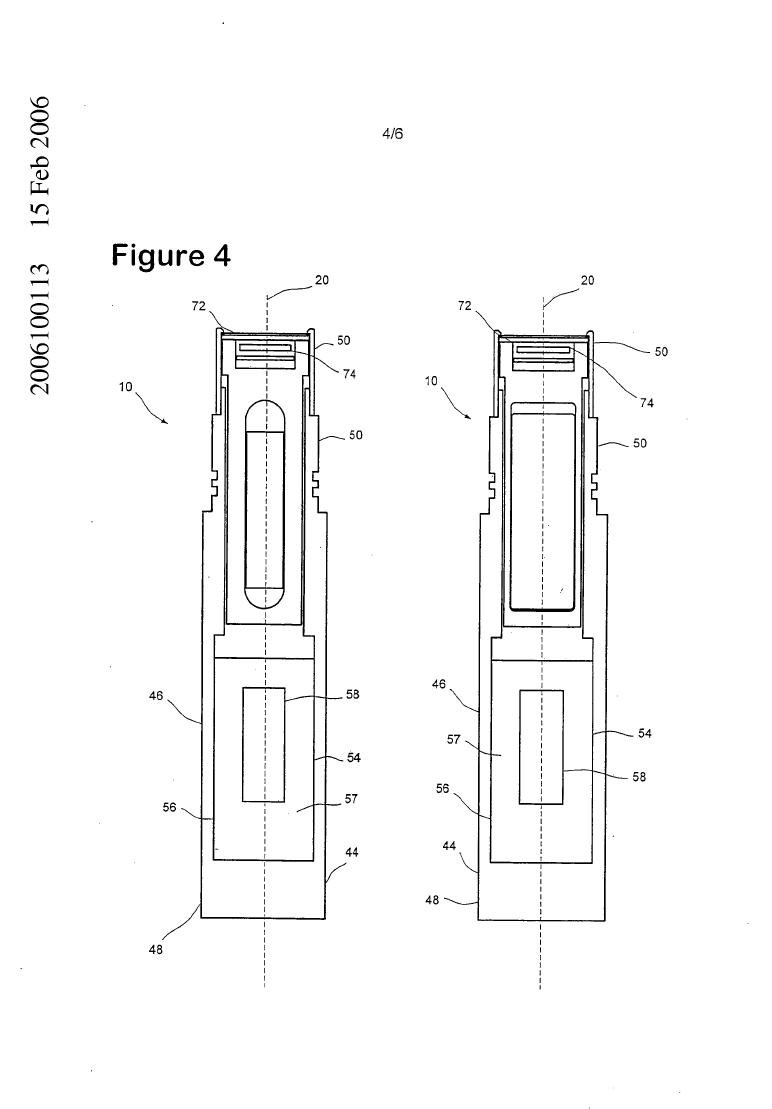

52 The Patent is an innovation patent for a core orientation device. It comprises two parts: the specification and the claims. The specification includes the following:

· A preamble entitled “Field of the Invention”.

· A statement of the objects of the invention showing how the invention comprises an advance of what was previously known and used, entitled “Background Art”.

· A description of what the inventor asserts his invention to comprise, entitled “Disclosure of the Invention”.

· The disclosure of a “preferred embodiment” of the invention to satisfy the requirement in s 40(2) of the Act that the best method known to inventor of performing the invention be stated, entitled “Best Mode(s) for Carrying Out the Invention”

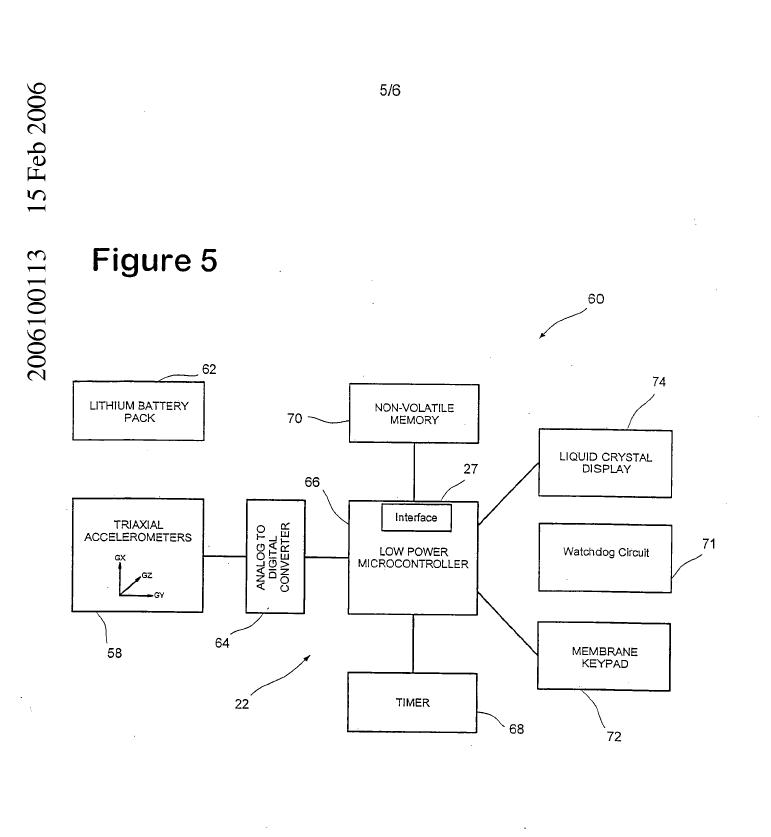

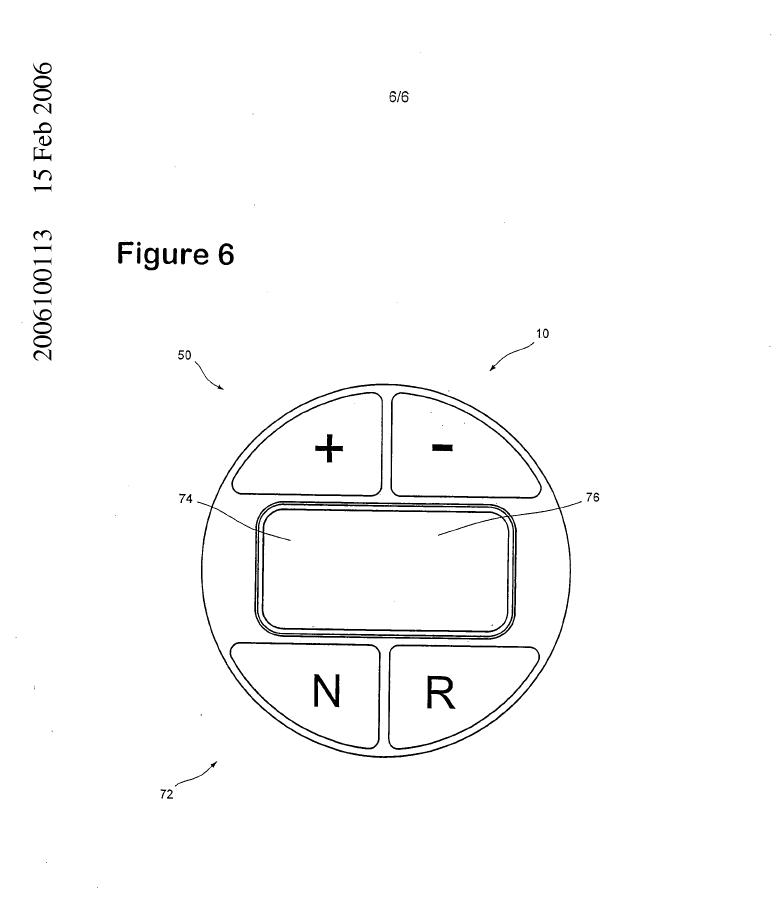

53 The specification also includes six illustrative figures which are briefly described in the body of the specification. The figures are annexed to these reasons asAnnexure A.

54 The Patent has five claims which define the invention and which claim both independently and by reference to each other. They set out the legal boundaries of the monopoly granted by the Patent. Any dependent claim is required to include all of the features of any other claim as incorporated by reference. Each claim is a stand alone statement of a monopoly: Re Raychem Corp’s Patents [1998] RPC 31 per Laddie J at 36-37.

55 The five claims are:

1. An orientation device for providing an indication of the orientation of a core sample relative to a body of material from which the core has been extracted, the orientation device comprising means for determining and storing the orientation of the device at predetermined time intervals relative to a reference time, means for inputting a selected time interval, means for relating the selected time interval to one of the predetermined time intervals and providing an indication of the orientation of the device at the selected time interval.

2. An orientation device as claimed in claim 1 attached to an inner tube assembly of a core drill and fixed against rotation relative thereto, the orientation device including means for attachment to the inner tube assembly.

3. An orientation device as claimed in claim 1 or 2 including means for comparing the orientation of the device at the selected time interval to the orientation of the device at any subsequent time and providing an indication of the direction in which the device should be rotated in order to bring it into an orientation corresponding to the orientation of the device at the selected time.

4. An orientation device for providing an indication of the orientation of a core sample relative to a body of material from which the core sample has been extracted, the orientation device comprising means for generating signals responsive to the orientation of the device, a processor for receiving the generated signals and for processing the signals to generate orientation data representative of the orientation of the device, means for storing the orientation data a predetermined time intervals, means for inputting a signal representative of a selected time interval to the processor, the processor operating to relate the selected time interval to the predetermined time intervals and output a signal indicative of the orientation of the device at the selected time interval.

5. An orientation device as claimed in claim 4 wherein data is generated representative of the orientation of the device at any subsequent time and the processor is operable to output a signal to a display means to provide a visual indication of the direction in which the device should be rotated at said subsequent time in order to bring the device into an orientation corresponding to its orientation at the selected time.

56 Claims 1 and 4 are independent claims. Claims 2 and 3 are dependent claims of claim 1. Claim 5 is a dependent claim of claim 4. As claims 1 and 4 are the independent claims and the broadest claims, the parties accept that if there is no infringement of them then there can be no infringement of claims 2, 3 and 5.

The Coretell Equipment

57 The Coretell Equipment is, like the invention described in the Patent, used to determine the orientation of a core sample recovered during mining operations. The Coretell Equipment comprises a down-hole tube section and a handset that is operated at the surface. Photographs of the equipment were tendered at trial and marked as exhibits R2 through to R7. At trial the respondents provided the Court with a live demonstration of how the Coretell Equipment is used.

58 The respondents also tendered a document (exhibit R12) entitled:

THE CORETELL EQUIPMENT

MAKE-UP AND MANNER OF WORKING

This document was received without objection and it was common ground between the parties that it disclosed how the Coretell Equipment worked. Relevantly, at [2], it provides:

(a) Prior to the lowering of the down hole equipment into the drill hole, the handset is turned on and wireless communication established with the down hole equipment. On establishing such communication, the operator may automatically initiate synchronisation of the real time clocks in both the handset and down hole equipment by way of an appropriate action button of the handset.

(b) Following synchronisation, the down hole equipment can then be lowered into the drill hole at the back end of an adapted core tube ready for drilling operations. Of course, once down the hole such wireless communication ceases.

(c) Down the hole, as drilling progresses, the accelerometers provide gravitational values relative to the x, y, z co-ordinates of the core tube at particular time intervals. These values are then calibrated and processed and, on an averaged basis at 10 second intervals, are then stored in a memory component. The stored values are representative of gravity values relevant to each accelerometer. As well, temperature values are stored.

(d) Once a desired length of core sample has been achieved (as determined by the operator), drilling is stopped and the drill string and down hole assembly becomes rotationally inactive. At the surface, the operator then takes up the handset and presses a button on the handset described as “Take Measurement”. This causes the clock in the handset to record the time the button the button was pressed. The handset also informs the operator to maintain the drill string inactive for a nominated period. (This is to achieve at least one orientation measurement during a period of down hole stability.)

(e) Once the handset provides the operator with an indication that the down hole equipment can be moved, the operator then can bring the core tube and down hole equipment to the surface.

(f) Once the down hole equipment is at the surface, real time communication is established between the handset and the down hole equipment by the Bluetooth wireless modules contained in the handset and down hole equipment.

(g) Once communication is established, the handset queries the down hole equipment to provide it with the calibrated accelerometer data associated with a time that most closely matches the time recorded by the handset when the “Take Measurement” button was pressed. The down hole equipment then provides the calibrated accelerometer data and temperature data to the handset. The handset componentry then processes such calibrated accelerometer data and the temperature data to determine the orientation of the down hole equipment (and core tube) at the marked time at which the “Take Measurement” button was pressed.

(h) At this stage, the handset and down hole equipment (at the back end of the core tube retaining the core sample) are in real time communication. The down hole equipment repeatedly transmits accelerometer data to the handset for processing. The handset processor then calculates the current orientation of the down hole tool and compares it to the orientation of the device at the time closest to that recorded by the handset. The results of these comparisons determine the direction in which the device must be rotated in order to realign the core device to its desired position and display this direction to the operator by way of the handset.

(i) By visual referral to the handset, but manually independent of it, the core tube with retained sample then can be rotated (by the operator or other person) to achieve coincidence of down hole and surface orientation of the core tube and retained sample. Once the desired orientation is achieved, the retained core sample is then marked and then can be removed from the core tube. The core sample can then be placed into a core sample tray and the core tube and associated down hole equipment then can be returned for another cycle.

(j) To be noted is that, usually, there are two down hole devices operating in sequence to maintain drilling efficiencies so that as one tool clears the surface, the second tool is then “started”/synchronised and lowered into the hole with the above described core orientation activity on the surface tool then to be undertaken in conjunction with the handset.

Consideration

59 Relevantly, claims 1 and 4 disclose the essential integers of the Patent which are the subject of dispute. The applicants say that these integers encompass the Coretell Equipment; the respondents say that they do not. During the hearing counsel for the applicants, without objection, handed up a document entitled “Expert Conferral – Interpretation of Claims in Patent” which outlined the essential integers of each claim (integers A through S).

Claim 1

A. An orientation device for providing an indication of the orientation of a core sample relative to a body of material from which the core has been extracted

B. the orientation device comprising means for determining and storing orientation of the device

C. at predetermined time intervals relative to a reference time

D. means for inputting a selected time interval,

E. means for relating the selected time interval to one of the predetermined time intervals and

F. providing an indication of the orientation of the device at the selected time interval.

2. Claim 2

G. An orientation device as claimed in claim 1 attached to an inner tube assembly of a core drill and fixed against rotation relative thereto,

H. the orientation device including a means for attachment to the inner tube assembly.

3. Claim 3

I. An orientation device as claimed in claim 1 or 2 including means for comparing the orientation of the device at the selected time interval to the orientation of the device at any subsequent time and

J. providing an indication of the direction in which the device should be rotated in order to bring it into an orientation corresponding to the orientation of the device at the selected time.

4. Claim 4

K. An orientation device for providing an indication of the orientation of a core sample relative to a body of material from which the core sample has been extracted, the orientation device comprising means for generating signals responsive to the orientation of the device,

L. a processor for receiving the generated signals

M. and for processing the signals to orientation data representative of the orientation device,

N. means for storing the orientation data at predetermined time intervals,

O. means for inputting a signal representative of a selected time interval to the processor,

P. the processor operating to relate the selected time interval to the predetermined time intervals,

Q. and output a signal indicative of the orientation of the device at the selected time interval

5. Claim 5

R. An orientation device as claimed in claim 4 wherein data is generated representative of the orientation of the device at any subsequent time,

S. and the processor is operable to output a signal to a display means to provide a visual indication of the direction in which the device should be rotated at said subsequent time in order to bring the device into an orientation corresponding to its orientation at the selected time.

60 The essential integers said to be in dispute were put into four broad categories, or issues, for resolution, namely:

1. The meaning of the word “device” (the device issue).

2. The meaning of the phrase “storing orientation” (the storage issue).

3. The meaning of the phrase “time interval” (the time interval issue)

4. The meaning of the related phrase “predetermined time interval” (the predetermined time interval issue).

61 The applicants submit that when properly construed, each word or phrase and the integers informed by them, clearly encompass the Coretell Equipment. The result, the applicants submit, is that the Coretell Equipment has taken all of the essential integers of the invention as claimed and thereby has infringed the Patent. The respondents submit that the Coretell Equipment has, when the claims are properly construed, not taken any of the essential integers and is consequently outside the scope of the Patent’s monopoly.

62 In the end, if the applicants fail to show that the Coretell Equipment has taken each and every essential integer of the invention as claimed, then the applicants’ claim for infringement fails. I turn first to discuss the device issue.

63 The device issue: The controversy here is whether the term “device” as used in the claims of the Patent can encompass a core orientation tool in two or more separate and separated parts (as the applicants submit it can) or whether it is limited to a unitary tool comprised of a single piece (as the respondents submit it must).

64 The term “device”, as used in the claims, appears in integers A, B and F of claim 1 and integers K, L/M and Q of claim 4. References to “device” in claims 2, 3 and 5 are dependent on these integers in claims 1 and 4. The parties do not dispute that these integers are essential to the Patent. Consequently, if the word “device”, as used in the claims, does not comprehend a tool in multiple parts then the Coretell Equipment has not taken all of the essential integers of the claims of the Patent and cannot be said to infringe the Patent. The result would be that the applicants’ case would fail.

65 I should emphasise at the outset of this analysis, as I have attempted to make clear earlier in these reasons, that the relevant term must be construed within the context of the claims as a whole and from the perspective of a relevantly skilled addressee of the Patent at the priority date, and not simply with an appreciation as to what that word may mean in common parlance or in various non-relevant fields of industry. I should also note that from the time the hearing before me commenced until the time when it concluded, the “device issue”, as I have termed it, was identified by the parties – particularly the respondents – as a key issue relevant to the construction and infringement arguments in this case. It was noted as such in the written opening submissions of the parties and repeatedly highlighted by counsel at trial.

66 The applicants submit that a reading of the word “device”, which treats it as a single physical thing should not be accepted. The applicants say that as a matter of ordinary usage it extends to things which have more than one separate physical component. The applicants highlight the evidence of Professor Trevelyan who, in cross-examination, cited various engineering objects comprising multiple separate components commonly referred to by engineers as a “device”, including an electric drill and its chuck, and the common car jack with a detachable handle. The respondents say that resort by Professor Trevelyan to broad meanings of the word “device” in contexts unrelated to the Patent claims is irrelevant and cannot assist the Court in interpreting the claims. While I consider Professor Trevelyan’s evidence relevant, because I have not accepted him as a non-inventive skilled addressee of this Patent, I necessarily give his evidence less weight than that of Dr Kepic and Dr Myers.

67 The applicants submit that the evidence of Dr Kepic in relation to this issue should be wholly accepted. Dr Kepic, at [16] of his affidavit dated 18 June 2009, considers that the term “device” means “an arrangement of items, not necessarily physically connected, which work together for the purpose of functionality and to produce a useful outcome”. Dr Kepic also gave evidence that in his field of geophysics, it is common to find a “device” which comprises a number of physically separate components but which nevertheless work together to produce a result and are referred to those skilled in the field as a single device. The examples he gives are of data harvesting tools which comprise a series of remote sensors and a separate handheld display unit, and differential GPS survey devices which comprise both a base station and a roving station. Dr Kepic says that in both “devices” the components are sold together as one integrated package and are functionally useless without each other. The applicants say that such a scenario is analogous to the patent in this proceeding and so the reasoning is transferable. The applicants say that this reasoning should be adopted and that, consequently, the term “device” in the claims clearly encompasses tools in multiple parts.

68 The respondents in turn say that this evidence is not relevant as it has nothing to do with the words or text of the Patent and cannot therefore aid claim construction. I disagree with this submission. The evidence given by Dr Kepic is clearly relevant to understanding the point of view from which a skilled addressee would approach a reading of the Patent. It supports the conclusion that Dr Kepic has a broad understanding of the term “device” as incorporating tools in two or more parts, outside of his involvement in this litigation. It militates against any assertion that Dr Kepic’s evidence is contrived. However, the construction of the claims is a task ultimately for the Court and not for the witnesses; therefore I do not treat Dr Kepic’s evidence as determinative of the controversy.

69 The respondents contend that the plain words of the claim, namely a plain reading of the phrases that include the term “device”, preclude tools in multiple parts from falling within the monopoly conferred by the Patent. The respondents base this argument on two premises, namely that:

· the claims do not contain any description or contemplation of any orientation device in two separate and separated parts; and

· the claims refer only to “the orientation of the device (emphasis supplied).

These premises have some overlap in that they both read the claims as restricted to a unitary device.

70 In relation to the first contention, that the claims do not contain any description or contemplation of any orientation in two separate and separated parts, the respondents point to the definite article, “the”, which precedes the term “orientation device” and the singular word “device” at several points in the claims. The respondents emphasise that the inclusion of the definite article clearly indicates that the claims are only intended to encompass unitary devices, not those with multiple components. The words of the claim should be understood as having been chosen with precision and care. The respondents submit that as a matter of ordinary grammar and syntax it cannot be contemplated that the phrases “the device” and “the orientation device”, when the definite article is taken into consideration, encompass two separate and separated components of one tool such as the downhole unit and handset of the Coretell Equipment.

71 Similarly, in relation to the second contention, that the claims refer only to the orientation of the device, the respondents say that it would be incorrect to interpret the claims as including a device in two or more parts as to do so would mean the reference to the orientation of the device in the claims would be a nonsense. Put another way, the respondents say that where the claims refer to “the orientation of the device” it is clearly referable to a device in one part, as if it were referable to a device in two or more parts it would, to be sensible, need to refer to either the orientation of one part or another. That is, the claims only speak to one orientation of one device, not the orientation of, say, a downhole unit and the separate orientation of a controlling handset. Nor do the claims speak only to the orientation of the downhole tube part of a multi-part device.

72 When this point was put to Professor Trevelyan in cross-examination, he accepted that the Coretell Equipment was comprised of two parts (transcript, 169) and that each part has its own orientation independent of the other (transcript, 210). The respondents highlight the fact that Professor Trevelyan accepted that as the two components of the Coretell Equipment can have independent orientations you cannot have one orientation representing the device as two disconnected objects (transcript, 210). The respondents say that once this is understood it is clear that the Patent is limited to tools in one part. To take it further would be to impermissibly stretch the words of the claims of the Patent outside of their clear textual meaning.

73 When the same proposition was put to Dr Kepic he also accepted that both the handset and the downhole unit components of the Coretell Equipment would have orientations quite independent of each other (transcript 391). Dr Kepic was then taken to the words of claim 1, and in particular to the words, “there must be a means for determining and storing the orientation of the device”. The transcript, at 392, records the following exchange during cross-examination:

Now, where, in the Coretell Equipment does that occur if, as your evidence says, the Coretell Equipment comprises a separate handset and a separate down hole unit, each

of which has its own orientation?---I don’t see - it seems to me a splitting of hairs but you cannot - the orientation of the handset is irrelevant, so the orientation of the device is the bore hole component of it.

Well, is what you’re saying to his Honour that you would rewrite the claim to mean read as follows:

Means for determining and storing the orientation of the down hole unit at predetermined time intervals.

?---It might be nicer but, you know, if it’s a peripheral there or a minor component I wouldn’t necessarily try and refer to them - if a - if it were me writing the claim and I wanted to retain a generality - you would normally refer to the most important component with respect to orientation. So whilst it might an omission for a device that has separate components, it doesn’t seem to me something that is completely illogical.

74 The respondents say that the evidence of Professor Trevelyan and Dr Kepic referred to above supports their interpretation of the claims as failing to encompass the Coretell Equipment. Dr Kepic clearly recognised that the claims contain “an omission for a device that has separate components”, though on his reading of the Patent this was not completely illogical because it would be obvious to a reader of the claims that the desired orientation would be that of the downhole component. Dr Kepic went on (at transcript, 396) to suggest that the handset component of the Coretell Equipment is “just not that important to things”, that it was, in his opinion, a “furphy”, and that one would have to be very literal “in the meanest sense” to say that the Coretell Equipment is excluded from claim 1 of the Patent. The respondents point to this evidence to support the argument that when the claims are given a plain, literal interpretation, the Coretell Equipment cannot be within them.

75 The respondents further say that the only way the claims of the Patent could encompass the Coretell Equipment is if they were substantially re-written to expressly refer to devices in multiple components. The respondents contend that, as with any other written document, such an approach is impermissible. The words of the claim must be construed as drafted and not re-written by notional amendments: Austal Ships Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag [2005] FCA 805; (2005) 66 IPR 420 per Bennett J at [126].

76 Senior Counsel for the respondents put to both Professor Trevelyan and Dr Kepic during cross examination the contention that for the Coretell Equipment to be within the scope of the monopoly of the Patent the claims would need to be substantially rewritten. Professor Trevelyan refused to be drawn on the topic saying that as he was not a patent attorney nor legally qualified he would not profess an opinion on how the Patent could be drafted (transcript, 213). However, Professor Trevelyan accepted in cross examination that the Coretell Equipment, as a two-part device, was not within the requirements of any of the claims of the Patent on a literal construction (transcript, 209, 211, 212). The respondents say that this evidence is significant and compellingly in favour of the respondents’ defence of non-infringement. However, Professor Trevelyan was at pains to make it clear to the Court that he approached his interpretation of the claims of the Patent purposively “as a guidance to somebody skilled in the art as about how to construct something” (transcript, 210).

77 When the same contention was put to Dr Kepic (transcript, 400), he acknowledged that “it would be preferable to rewrite” the claims but that he did not believe it was necessary if you accepted his interpretation of the claims. That is, Dr Kepic accepted that the claims could arguably be drafted to be clearer but that nonetheless the claims as drafted, on his understanding of the Patent, encompass the Coretell Equipment in two separate and separated parts.

78 In contrast to the evidence of Professor Trevelyan and Dr Kepic, the respondents say that Dr Myers’ evidence as to the meaning of the term “device” is consistent. The respondents say this evidence was not challenged or changed by his cross-examination. Dr Myers’ position was, and remained, that the word “device” as used in the claims refers to something which is physically integrated, as in semi-conductor devices; it means a single unit (transcript, 327). Dr Myers explained (transcript, 324) what, in essence, he understands the word “device” to mean:

My thinking in the definition that I gave in the affidavit was that my natural inclination is device refers to first of all a semi-conductor device, if not, that’s something that’s physically interconnected. So I looked at the claims as a whole and I didn’t see anything in them which challenged the view that this was physically interconnected.

79 The applicants say that Dr Myers simply defined “device” as a single physical thing without regard to the features of the claim. The applicants further submit that Dr Myers, in oral evidence, still did not resort to the text of the claims but said that you need to understand the Patent and the claims as referring to a single physically integrated thing because in computer engineering it is important to only refer to a single device. This submission is correct up to a point. Dr Myers clearly approached the claims with an assumption as to how the word “device” was to be read. However, I do not think it can properly be said that Dr Myers had no regard to the text of the Patent. As Dr Myers explained in the oral evidence set out above, though he approached the claims with an understanding of what the word “device” meant to him, this understanding was checked against the text of the claims to see if there was anything in them which challenged his view that the invention in the Patent was physically interconnected. Having satisfied himself that nothing in the claims challenged this view, Dr Myers proceeded on the basis that the word “device” as used in the claims corresponded with his understanding of the term generally. The applicants say that this approach, and Dr Myers evidence generally, exposes a pedantic and strained approach to the construction of the claims and as such should be rejected.

80 In my view, a literal construction of the claims and identified integers is open such that the “device” referred to is a single, physically interconnected thing, not separated into parts or components. In particular, the indication that it is the device that goes down a hole and is to be oriented suggested that there is only one device, part or component, at all times of its usage.

81 The arguments against such a literal construction appeal to common sense. First, that it is pedantic and artificial. The applicants emphasise that Dr Kepic, when cross-examined on the point, said that to read the relevant claims as containing an omission for a device that has separate components is a “furphy”, and to insist on such a construction would constitute literalness “in the meanest sense”, and that the separation of the handset from the down hole unit is “just not that important to things”.

82 Secondly, to focus on the word “device” without proper regard to the phrases in which the word appears – “an orientation device” and “the orientation device” and “the orientation of the device” – is likely to be conducive of error. That is to say there is nothing particular in the use of the word “device” that suggests it cannot be constituted by a number of components, as Dr Kepic says it can be and in respect of which he provided real examples. In this regard, it is relevant to note that a usual dictionary definition of “device” does not define it as a singular physical thing. For example, the Macquarie Dictionary defines “device” as, amongst other things, when used as a noun, “an invention or contrivance”. It remains an open question whether an invention or contrivance may be comprised of more than one part.

83 Thirdly, the approach to the reading of the relevant claims adopted by Dr Kepic does not require any straining of language. By contrast, the construction of Dr Myers, if it is agreed, is artificial. While he, in the field of computer engineering, might be familiar with devices that come with only one part or component, that does not mean that a device must always be in that form.

84 Fourthly, the second strand to the argument put forward on behalf of the respondents that the expression “the orientation of the device” must mean that not only the down hole component but also the handset component must be in the one physical instrument so that all parts of the device are oriented at the same time, is not a view that the skilled addressee would ordinarily take. Dr Kepic (supported also by Professor Trevelyan) said that in dealing with a device designed to give an indication of the orientation of the core sample relative to a body of material from which the core has been extracted, the skilled addressee would immediately understand that it is the orientation of the down hole component that is important in the functioning of the device and that the other component (which constitutes the handheld component in the Coretell Equipment) is peripheral. In other words, the skilled addressee would have no difficulty in appreciating that the word “device” meant only the down hole unit in this integer. Dr Myers’ view to the contrary was a very literal view of what appears in the claims, and not sufficiently informed by the practical experience one expects of the skilled addressee in a case such as this.

85 I consider the resolution of this construction issue to be finely balanced. However, in the result, I consider the literal construction contended for by the respondents is neither contrived nor in defiance of common sense. It also, in my view, is the construction that best sits with established construction principles.

86 First, nowhere in the claims is there reference to a device in two or more separate and separated components. The claims are drafted in the singular and use the definite articles “the” and “an” to indicate this. Read contextually there is nothing in the claims to suggest they encompass multi-part tools. Even when recourse is had to the specification as a whole in order to resolve any ambiguity in the meaning of the word “device”, the specification does not at any point suggest the invention is to be construed as encompassing tools in more than one part. If anything, the background art disclosed in the specification suggests that the invention disclosed in the Patent was designed to replace other unitary downhole systems of core sample orientation that relied on physically marking the core sample. The Patent, at the priority date, was concerned with improving upon those mechanical systems and replacing them with tools which utilise accelerometers as a means of determining core sample orientation. The claims do nothing to suggest that the invention in the Patent was ever intended to be wider than a unitary device that used accelerometer technology to improve on historical methods of core orientation. Claim 2, in particular, speaks of “an orientation device as claimed in claim 1” which is “attached to an inner tube assembly of a core drill”. The clear inference to be drawn is that the device claimed in claim 1 is a unitary device, the whole of which is to be attached to an inner tube assembly of a core drill. Thus, to encompass a tool in two parts the claims would need to be rewritten to make it clear that only the downhole part of a multi-part tool would be attached to the inner tube assembly of a core drill, not the entire device.

87 Secondly, the reference in the claims to “the orientation of the device” suggests a whole device, that is, one in a single part. One should be guided by the principle of claim construction that what is not claimed is disclaimed: EMI at 29. The rationale for such a principle is that the patentee should only receive a monopoly for what is made clear in the patent claims so that relevantly skilled addressees of the patent know what the boundaries of the monopoly are. A patent is, after all, a public document. The claims should be precise and their object – and consequently the Court’s approach to their interpretation – should be to limit and not expand the monopoly sought. As Bennett J recently remarked in Lundbeck, at [60], there is no warrant for adopting a method of construction that gives a patentee what it might have wished or intended to claim, rather than what the words of the relevant claim actually say. While the Court should read the claims purposively and not with an eye for pedantry, even an appropriately liberal approach to construction should not permit the words of the claims to be stretched beyond their textual limits.

88 Finally, Dr Kepic’s evidence as to the meaning of “device” should not be determinative of the controversy. Ultimately the construction of the claims is a task for the Court and while this task must be undertaken from the perspective of a non-inventive skilled addressee, it must also be referable to the context, and the words, of the claims themselves. When pressed in cross-examination, Dr Kepic conceded that the word “device”, read literally in the context of the claims, could not encompass orientation tools in two parts. Dr Myers’ evidence on this point disclosed that a relevantly skilled addressee, interpreting the term “device” purposively in the context of the claims as a whole, could read that term as being limited to a tool in one piece.

89 I find therefore that the Coretell Equipment, in two separate and separated parts, is not within the scope of the term “device” as used in the claims. The result is that the Coretell Equipment does not infringe the Patent and the applicants’ claim for infringement fails.

90 Material variation: While my construction of the “device” issue means there is no infringement of the Patent by the Coretell Equipment, I should, for the sake of completeness, also deal with the further point agitated by the parties as to whether the Coretell Equipment is a material variation on the invention as disclosed in the Patent and so not within its monopoly.

91 The respondents observe that the Coretell Equipment, in two parts, is self-obviously very different to the unitary device described in the preferred embodiment of the Patent. The respondents submit that the evidence shows a material variation between the Coretell Equipment and invention as disclosed in the Patent that is so significant that there could be no infringement, even if the scope of the words “orientation device” included a form of orientation device or equipment in two or more parts.

92 The applicants say that any alleged improvement by the Coretell Equipment to the invention disclosed in the Patent is based on asserted benefits to the user of a device in two parts. The applicants say this assertion is not made out on the evidence. Rather, the applicants submit that, while a two part tool may be an improvement with benefits, such a tool creates new problems for the designer resulting in, at best, “functional equivalence”. The applicants say that, even if the word “device” is read as a reference to a unitary tool, the Coretell Equipment is not a material variation on such a tool and therefore is within the scope of the Patent’s monopoly.

93 Asserted benefits of the Coretell Equipment were identified by Mr Barker during viva voce examination, and Dr Myers in [44] of his affidavit of 7 November 2008. The asserted benefits that the respondents rely on to say the Coretell Equipment is a material variation to the invention disclosed in the Patent, include:

· The input mechanisms and display unit on the invention as disclosed in the Patent are the two components of the device most prone to damage in a borehole environment, therefore separating out such components so that they are not required to operate in the borehole environment reduces the risk that the system may be rendered inoperable (Dr Myers’ affidavit dated 7 November 2008 at [44], transcript, 239).

· Ergonomic improvements, including that operators of the device would not have to peer down the length of the device to determine orientation but could do so more comfortably from a standing position.

· Reduction in human error as the use of a stopwatch as required by the invention disclosed in the Patent would be eliminated.

94 The respondents submit that the result of these improvements is that overall the position must be that the material variation constituted by the Coretell Equipment relevant to the orientation device as claimed is so significant that no issue of infringement could arise from any construction of the Patent claims.

95 The applicants say that whilst a two part device may be an improvement with benefits, such a decision creates new problems for a designer resulting in, at best, functional equivalents. Professor Trevelyan considered that the handheld unit in fact has the advantage of eliminating possible causes of human error by ensuring that the human operator does not have to write down the time value on the stop watch and then key in the time correctly later (transcript, 170, line 1). However, despite this he considered the Patent leaves it open to the designer to choose a suitable method for indicating the appropriate time interval at which to record orientation signals for comparison later (see Professor Trevelyan’s affidavit dated 28 August 2008 at [71]). The applicants say that the use of a handheld unit therefore remains within the monopoly granted by the Patent.

96 In relation to the other improvements suggested by the respondents, the applicants note that Professor Trevelyan addressed the suggestions that the handheld unit offers benefits because it protects at least part of the device from having to work in the down hole environment, and that the handheld unit has ergonomic benefits for the operator in the drilling environment. He rejected the suggestion that these are advantages. He said that any vulnerable operational aspects of the down hole unit that can be protected from the down hole environment if built properly (transcript, 171, line 22). He also said the ergonomic benefits could probably be addressed if one did not have a handset by providing the operator with a stool to sit on (transcript, 172, line 13), but in any event the improvement or difference would be marginal (transcript, 172, line 31). The applicants say this evidence should be accepted particularly since it is accepted that the operator of the Coretell Equipment needs to stand within two metres of the down hole unit and core sample for the bluetooth connection to work.