FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mantra Group Pty Ltd v Tailly Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 291

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mantra Group Pty Ltd v Tailly Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 291

CORRIGENDUM

1. In paragraph 48 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the third sentence, “Coca Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 7” should read “Coca-Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107”.

2. In paragraph 50(d) of the Reasons for Judgment, in the second sentence, “Sportsbreak Travel Pty Ltd v P & O Holidays Ltd” should read “Sports Break Travel Pty Ltd v P & O Holidays Ltd”.

3. In paragraphs 50(d) and 50(e) of the Reasons for Judgment, “Sportsbreak” should read “Sports Break”.

4. In paragraph 67 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the last sentence, “Lord Greene MR” should read “Sir Greene MR”.

5. In paragraph 80 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first sentence, “Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Pepsi Co (Aust) Pty Ltd” should read “”Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd”.

6. In paragraph 95 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first sentence, “Adrema Ltd v Adrema-Werke GmbH (1858) RPC 323” should read “Adrema Ltd v Adrema-Werke GmbH [1858] RPC 323”.

7. In paragraph 95 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the last sentence, “Berzins Speciality Bakeries Pty Ltd v Monty’s Continental Bakery (VIC) Pty Ltd” should read “Berzins Speciality Bakeries Pty Ltd v Monty’s Continental Bakery (Vic) Pty Ltd”.

8. In paragraph 113 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the third sentence, “Appollinaris’ Application (1891) 8 RPC 127” should read “Appollinaris Application (1891) 8 RPC 137”.

|

I certify that the preceding eight (8) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Reeves. |

Associate:

Dated: 4 October 2010

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents transfer registration of the Circle on Cavill domain names, and any other domain name which is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the Circle on Cavill marks, to the second applicant, within seven days of the date of this order.

2. The respondents are permanently restrained:

(a) from using CIRCLE ON CAVILL, or a term that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to CIRCLE ON CAVILL, as a trade mark in the advertising, promotion or supply of accommodation, including as part of a domain name, metatag, search engine keyword or business name;

(b) from using the trade marks depicted in Registration Nos. 944267 and 1079454, or a mark that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar thereto, as a trade mark in the advertising, promotion or supply of accommodation; and

(c) from using the term MANTRA or a term that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar thereto, as a trade mark in the advertising, promotion or supply of accommodation, including as part of a domain name, metatag, search engine keyword or business name.

3. The respondents are permanently restrained from assisting another person from doing what is restrained in paragraph 2 above.

4. An account of profits for bookings sourced via the Circle websites or other websites or directly related to infringing use of the Circle on Cavill marks, in relation to accommodation provided in resorts managed by the applicants.

5. In these orders the following expressions have the meanings stated:

(a) “Circle on Cavill domain names” means the following domain names:

- circleoncavile.com.au

- circleoncavillapartments.com.au

- circleoncavillretail.com.au

- ecircleoncavil.com

- ecircleoncavill.com

- ecircleoncavill.com.au

- circleoncavill.mobi

- cavillapartments.com

- circleapartments.com.au

- circleoncaville.com.au.

(b) The “Circle on Cavill marks” means:

the three registered trade marks held by the second applicant – one word mark Registration Number 944268 and two word and devices marks Registration Numbers 944267 and 1079454 – incorporating the words “Circle on Cavill”.

(c) The “Circle websites” means the websites linked to the Circle on Cavill domain names as shown in Schedules 1 to 10 attached:

circleoncavile.com.au – Schedule 1

circleoncavillapartments.com.au – Schedule 2

circleoncavillretail.com.au – Schedule 3

ecircleoncavil.com – redirects to a1goldcoastholiday.com – Schedule 4

ecircleoncavill.com – Schedule 5

ecircleoncavill.com.au – Schedule 6

circleoncavill.mobi – Schedule 7

cavillapartments.com – Schedule 8

circleapartments.com.au – Schedule 9

a1goldcoastholiday.com.au – which redirects to circleoncavillapartments.com.au – Schedule 10.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules. The text of entered orders can be located using Federal Law Search on the Court’s website.

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 224 of 2009 |

|

BETWEEN: |

MANTRA GROUP PTY LTD ACN 110 396 999 First Applicant MANTRA IP PTY LTD ACN 129 980 981 Second Applicant SUNLEISURE OPERATIONS PTY LTD ACN 113 285 153 Third Applicant |

|

AND: |

TAILLY PTY LTD ACN 105 940 181 First Respondent STEPHAN ANDREW GRANT Second Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

REEVES J |

|

DATE: |

26 march 2010 |

|

PLACE: |

BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

background

1 Circle on Cavill is a residential apartment and retail complex situated at Surfers Paradise on the Gold Coast in Queensland. The complex includes two high-rise towers containing 644 residential apartments.

2 The Mantra Group, of which the three applicants are members, has contracted, via the third applicant, with the body corporate of Circle on Cavill residential apartments to manage the common property in the two high-rise towers and to be the exclusive on-site letting agents for the residential apartments.

3 Mantra also holds, via the second applicant, three registered trade marks – one word mark and two word and devices, or logos – incorporating the words “Circle on Cavill”. As well, Mantra holds three registered trade marks for the word “Mantra” and a fancy word mark for the word “Mantra”.

4 As the exclusive on-site letting agents, Mantra currently has 261 apartments in the Circle on Cavill complex available to sub-let for both holiday and longer term accommodation. However, Mantra does not have a monopoly over these letting services for the whole Circle on Cavill complex. The 644 apartment owners are free to choose whether to use Mantra’s on-site letting services or the services of some other agency located offsite. Flowing from this, approximately 39 apartment owners have chosen to enter into leases with Tailly Pty Ltd, the first respondent, thereby allowing it to sub-let those apartments to people seeking holiday accommodation at the Circle on Cavill complex. As well, another 95 apartments are sub-let through a range of other offsite agencies.

5 This competition between Mantra, as the on-site letting agents, and Tailly as one of the off-site letting agents, for the letting of accommodation in the Circle on Cavill complex provides the backdrop to this dispute. Mantra claims that Tailly has infringed its registered trade marks by using the words “Circle on Cavill”, the “Circle on Cavill” logos and the word “Mantra”, or deceptively similar words, as trade marks, in advertising and marketing, on the internet, the apartments it has available for let at the Circle on Cavill complex. It also claims Tailly has used those words and logos in its internet advertising and marketing, in a false, misleading or deceptive way in breach of a number of provisions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). It seeks various remedies for these alleged infringements and breaches, including permanent injunctions.

6 Tailly admits it has used the words “Circle on Cavill” in its internet advertising and marketing. However, it says it has not used those words as a trade mark, but rather to describe the location and name of the Circle on Cavill apartment complex where it has apartments available to let. Alternatively, it says it is not liable for any infringement of Mantra’s trade marks because it has used the words “Circle on Cavill” in good faith to indicate the geographical origin of the accommodation services it is offering at the Circle on Cavill complex. Tailly has also filed a cross-claim alleging that Mantra’s trade marks incorporating the words “Circle on Cavill” should be cancelled because they have become generally accepted in the trade of sub-letting apartments in Surfers Paradise as the sign that describes the name of the Circle on Cavill apartment complex.

7 Tailly also admits that it used one of the “Circle on Cavill” logo marks on certain letters it prepared and sent to an organisation called Amadeus in October and November 2008. During the hearing, these were referred to as the “switch” letters because they directed Amadeus to switch its listing for the Circle on Cavill complex from Mantra to Tailly. Finally, Tailly admits it used the word “Mantra” in a domain name it registered called www.mantra.au.com and as a metatag in the source code for the related website.

8 With one exception I will mention below, Mantra’s counsel advised me in final submissions that it was willing to accept these latter two admissions and not pursue any other claims for the infringement of the Circle on Cavill logo marks, or the Mantra word marks. It follows that the only issue that needs to be determined in relation to these admitted infringements, is the nature of the relief, if any, that should be granted.

9 The exception I mentioned above is that there is a dispute as to the use of the word “Mantra” in connection with a booking that was made with Tailly via the hotels.com’s website by a Ms Dana Erickson in September 2009. Mantra alleges that this use of the word “Mantra” occurred through the agency of Tailly and it therefore constituted use by Tailly. Tailly denies this.

10 It follows that, apart from the extent, if any, of any relief to be granted for the admitted infringements involving one of the Circle on Cavill logo marks and the Mantra word mark, the areas of dispute in relation to the alleged trade mark infringements can be reduced to the following:

whether Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill” was use as a trade mark; and

whether the use of the Mantra word mark in connection with the booking made via hotels.com was use by it as the agent of Tailly so as to constitute use of it by Tailly.

the issues that arise

11 Based on the areas of dispute that have been outlined above, the issues that arise for determination in these proceedings can be summarised as follows:

1. Did Tailly use the words “Circle on Cavill” as a trade mark?

2. If so, did Tailly use the words “Circle on Cavill” in good faith to indicate the geographical origin of the accommodation services it was offering at the Circle on Cavill complex?

3. Have the words “Circle on Cavill” become generally accepted within the trade of sub-letting holiday apartments as the sign that describes, or is the name of, the apartment complex, such that the Mantra Group has lost its exclusive rights to use those words as a trade mark?

4. Was the Mantra word mark used by hotels.com as the agent of Tailly so as to constitute use of it as a trade mark by Tailly?

5. Has Tailly breached ss 52 or 53 of the Trade Practices Act in its advertising, or marketing of the accommodation services it was offering at the Circle on Cavill complex?

6. What relief, if any, should be granted to the applicants, or the respondents?

12 I will turn to consider these issues in the order set out above. Before doing so, I should note three procedural matters that have further limited the scope of the matters in dispute in these proceedings. First, this is a Fast Track matter and it has therefore been conducted in accordance with the Fast Track Practice Note CM 8. Secondly, before the trial of these proceedings began, Mantra resolved its dispute with the third and fourth respondents and orders were made by Greenwood J on 30 November 2009 disposing of the proceedings against them. Thirdly, on 26 October 2009, Greenwood J ordered that the issues of liability and quantum were to be split. I do not, therefore, need to make any assessment of damages, if that were to become necessary.

1. DID tailly USE the WORDS “Circle on Cavill” as a trade mark?

Relevant legislative provisions

13 The relevant infringement provision of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) relied upon by Mantra is s 120(1). It provides as follows:

A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

14 The word “sign” in this and many other sections of the Trade Marks Act is defined in s 6 of the Act as:

sign includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent.

15 The “sign” Tailly is alleged to have used in infringing Mantra’s Circle on Cavill word mark are the words “Circle on Cavill”, or “Circle on Cavill Apartments”, or similar words.

Relevant matters admitted by Tailly

16 Apart from the question whether it used this sign as a trade mark, Tailly has admitted the facts going to the remainder of the matters in s 120(1). In particular, it has admitted that:

the second applicant owns the relevant trade marks, viz: the Circle on Cavill word mark; the two Circle on Cavill logo marks; the Mantra word marks; and the Mantra fancy name mark.

the words of the sign are either substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the “Circle on Cavill” word mark; and

the sign was used in relation to the services in respect of which the Circle on Cavill word mark is registered, including the provision of temporary accommodation; the rental of temporary accommodation; and the reservation services for temporary accommodation.

17 Tailly also admits it used the words “Circle on Cavill” or similar words, in the following internet domain names and/or the websites linked to them:

| a1goldcoastholiday.com | a1goldcoastholiday.com.au |

| cavillapartments.com.au | circleapartments.com.au |

| circleoncavile.com.au | circleoncavillapartments.com.au |

| circleoncavillretail.com.au | circleoncavill.mobi |

| crowntowersapartments.com.au | ecircleoncavill.com |

| ecircleoncavill.com.au. |

The internet – what it is and how it operates

18 Since this infringement issue revolves around the use of the internet to advertise and market services, I should begin by explaining what the internet is and how it operates and then to detail how and why the internet was used for that purpose in this case. In what follows, I have relied principally upon the evidence of Mr Lattimore, Mantra’s Digital Channel Analyst, and the chapter in Davison M, Berger T and Freeman A, Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (4th ed, Lawbook Co., 2008) (“Shanahan”) on “Trade Marks and Electronic Commerce”: Chapter 115.

19 In British Telecommunications Plc v One in a Million Ltd (1998) 42 IPR 289 (“One in a Million”), Aldous LJ succinctly described, at 290, the internet as “a collection of computers which are connected through the telephone network to communicate with each other”.

20 To connect to the internet, a person needs a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) or domain name. A domain name is a string of letters, or a combination of letters and numbers, that are used instead of an internet protocol address (IP address). An IP address is a string of numbers that is used to identify each computer connected to the internet – it is unique to that computer. Because they use letters and numbers, domain names are considered to be easier to remember and use than the long strings of numbers used in IP addresses.

21 A website is accessed by an IP address, or a domain name. For present purposes, a website is the place where the domain name owner’s advertising content is located. That advertising content may be in the form of written web pages, still images, or video or sound recordings, or a combination of all, or some, of these.

22 While each domain name can only be linked to one website, multiple domain names may be linked to the same website. However, some domain names are not linked to a website at all. This often occurs when an organisation registers a domain name defensively to avoid others registering that name first.

23 Each domain name consists of at least three levels. The first level is the internet protocol “www”, which is an acronym for “world wide web”. The second level is the name of the specific domain, eg in this case, “circleoncavill”. The third level is the generic or open domain, eg, “.com” or “.net”. Many countries also have, as a fourth level, a country code domain, eg, for Australia, “.au”.

24 As I have already mentioned above, each domain name is unique. It follows that only one person or organisation can obtain a specific name within a particular generic or open domain. The consequence of this is explained in Shanahan at [115.505] as follows:

Anyone can obtain a domain name in an open domain. Application for a domain name is made to any one of the domain name Registrars authorised by the [Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers] ICANN to issue domain names. The system is one of first-in, first-served and there is no examination of the nature of the interests of the registrant. Consequently, it is difficult, if not impossible, to prevent another entity registering a particular domain name if they are the first to seek registration.

25 As Shanahan goes on to observe (at para [115.510]), this system may result in a person or organisation without a legitimate interest obtaining registration of a particular domain name and, where that domain name happens to be a registered trade mark, general trade mark law may have to be resorted to by the registered owner of the trade mark to obtain redress. Alternatively, the registered owner may be able to use the dispute resolution process established by the ICANN. This process is explained in Shanahan at [115.625] to [115.680].

26 In order to conduct a search for information located on websites on the internet, or the world wide web, one must use a search engine. The major search engines include Google, Microsoft’s Bing search engine and the Yahoo search engine. When a person conducts a search on a search engine like Google, Google will rank and return the results in the order that it believes will give the most relevant and useful websites first. Typically, Google will display 10 websites per page of search results. These search results are called “organic search results” and their ranking is determined by Google. Shanahan explains how organic results are obtained (at [115.1125]) as follows:

… Organic results are generated automatically according to the search criteria of the search engine in question as it trawls through websites. The precise nature of those searching processes and search criteria are kept secret by the search engines. The search criteria also change from time to time as search engines attempt to ensure the maximum efficiency and usefulness of the search engine to users.

… The consequence of automated searching is that the organic results produced by a search engine will depend upon the search criteria adopted and the extent to which any particular website meets those criteria, either as a natural consequence of its content and links to it, or artificial manipulation by the website owner of the search criteria.

27 Websites have an underlying source code that are inserted by web developers and computer programmers. This source code contains key words that are used to indicate what is contained on the website. This key word information is often described as meta information or metatags. The information is not displayed on the website itself. Instead, it is used by Google and other search engines to assist in indexing and ranking websites when displaying search results.

28 In responding to a search request, Google uses computer algorithms to assess the level of relevance of the various websites on the internet. While the precise details of these algorithms are said to be secret, it is known they include matters such as the domain name, the number of links that have been made to various websites, the number of times a particular phrase appears on the internet, how many times the product or service sold via a website has been reviewed, and other similar matters. Thus, the more frequently a phrase appears on the internet, the more significant, or relevant, it will appear to Google. This means that an organisation can attempt to manipulate the Google search results so that their website is ranked high on the Google organic search results. One way of doing this is to attempt to write the underlying source code for the website so that it will attract a higher ranking.

29 Businesses may also place paid advertisements on the internet using organisations such as Google, Bing or Yahoo. These paid advertisements appear as sponsored links on the top, or on the right hand side, of the organic search results. Google charges an amount per key word used in each advertisement. It also charges a higher rate for popular key words such as “Gold Coast”. However, if Google is informed a particular person holds a registered trade mark in relation to a sign, eg, “Circle on Cavill”, it will not allow anyone else to use those words as a key word. Nonetheless, this does not prevent other organisations using similar words, or parts of the words, eg, “Cavill on Circle” or “Circle Apartments”.

30 Google was apparently not informed that Mantra held a registered trade mark in relation to the words “Circle on Cavill” until approximately 21 May 2009. Since then, Google has not allowed anyone else to use the words “Circle on Cavill” as a key word in any of its paid advertisements.

Why and how Mantra uses the internet

31 As mentioned above, Mr Alistair Lattimore is the Digital Channel Analyst for the Mantra Group. He gave evidence that more than 50% of people booking accommodation in Australia will use the internet to research and make those bookings. As a result, Mantra considers its internet advertising and marketing programs are extremely important to its business. As a mark of its importance, Mantra presently holds approximately 850 domain names. I use the word “holds” because, as Shanahan points out (at [115.1060]), a person does not “own” a domain name, but rather holds a renewable licence for it from the relevant ICANN. Included within Mantra’s 850 domain names are:

circleoncavill.com.au;

circleoncavill.net.au;

circleoncavill.com; and

mantracircleoncavill.com.au.

32 Some of Mantra’s domain names are property specific, eg crowntowersresort.com.au; some are house brand specific, eg mantra.com.au; others are destination specific, eg harveybay.com.au; and still others are events specific, eg for events like schoolies week. Apart from the name “Mantra”, the Mantra Group has other house brands such as “Peppers” and “Break Free”.

33 Among his duties as the Digital Channel Analyst for the Mantra Group, Mr Lattimore is responsible for search engine optimisation. This process (described at [28] above) includes ensuring Mantra’s websites load quickly, they are content rich and relevant, and they are current. It also involves studying the common search terms being used by people looking for accommodation on the internet and then editing Mantra’s websites and, more particularly, the source codes that underlie them, to attempt to ensure that Mantra’s websites will be ranked as high as possible on any list of organic search results. By applying this process of search engine optimisation, Mantra hopes to ensure that at least one Mantra domain name will appear in the first two or three positions in the organic results returned.

34 Mantra attempts to achieve these high rankings in the organic results because most people tend to click through to the websites of the highest ranked domain names shown. Indeed, Mr Lattimore’s research shows that domain names or websites that are ranked high on the first page of search results usually obtain a very high click through rate, whereas the click through rate progressively drops off to 30%, and below, for those domain names or websites appearing in the second half of the first page of search results and following.

35 In addition to tending its websites in this way, Mantra also places paid advertisements on the internet with search engines like Google, Bing and Yahoo. To obtain the best results from this paid advertising, Mantra uses software programs such as Google Add Words and Ad Sense.

How Tailly uses the internet

36 Just as Mantra devotes considerable time and effort to its internet advertising and marketing, so too does Tailly. Of particular relevance to this case, Mr Lattimore gave evidence that during the six month period between May and November 2009, he had reviewed on a regular basis 16 domain names and their related websites all of which were held by either Tailly or Mr Stephan Green, the second respondent. Those domain names were as follows:

(a) circleoncavile.com.au;

(b) circleoncavillapartments.com.au;

(c) circleoncaville.com.au;

(d) circleoncavillretail.com.au;

(e) circleskyrise.com (blank);

(f) circleskyrise.com.au;

(g) ecircleoncavil.com (redirects to a1goldcoastholiday.com);

(h) ecircleoncavill.com;

(i) ecircleoncavill.com.au;

(j) circleoncavill.mobi;

(k) cavillapartments.com;

(l) circleapartments.com.au;

(m) circlehighrise.com (blank);

(n) circlehighrise.com.au;

(o) a1goldcoastholiday.com.au (redirects to circleoncavillapartments.com.au); and

(p) tailly.com.au (error on page).

37 It will be noted that, apart from the last two on this list, the remaining 14 begin with the word “Circle”, or the letter “e” followed by the word “Circle”, or in one instance the word “Cavill”. Further, nine of the 14 domain names use the word “Cavill”, or a misspelling of that word such as “Cavile” or “Cavil”.

38 The practice of registering a domain name with a misspelling of another domain name is called “typosquatting” or domain mimicry. Its purpose is to either capture web traffic if someone mistypes a domain name into an internet browser like Internet Explorer, or to attract search engines that are programmed to pick up such misspellings: see Shanahan at [115.570]. Mr Lattimore gave an example of the latter in his evidence. When he conducted a Google search using the words “Circle on Caville”, he said the organic search results began with the question “Did you mean: Circle on Cavill” and then listed a number of domain names or websites containing the correct spelling of “Cavill”.

39 Mr Lattimore produced copies of the contents of the websites attached to each of the domain names in the list at [36] above. Putting aside the domain names that did not include the word “Cavill”, or a misspelling of it, eg “circlehighrise.com” and the domain name “tailly.com.au”, which returned an error message result, but including: (l) circleapartments.com.au and (o) a1goldcoastholiday.com.au, which redirects to (b) circleoncavillapartments.com.au, there are 11 domain names left. One of those domain names, viz (c) “circleoncaville.com.au”, returned a result that stated that “this domain name is registered and parked with Crazy Domains”.

40 The contents of the web pages for the websites attached to each of the 10 remaining domain names appear as schedules to these reasons as follows:

(a) circleoncavile.com.au – Schedule 1

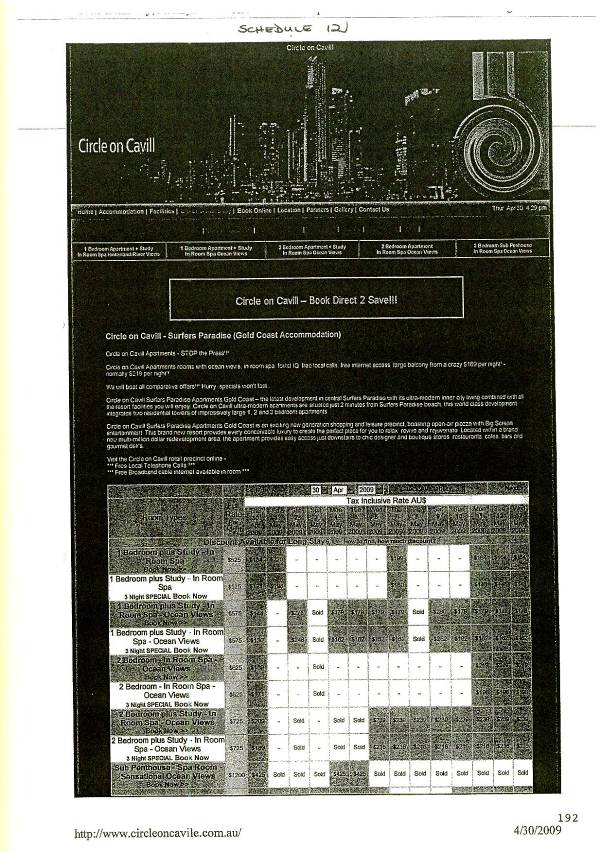

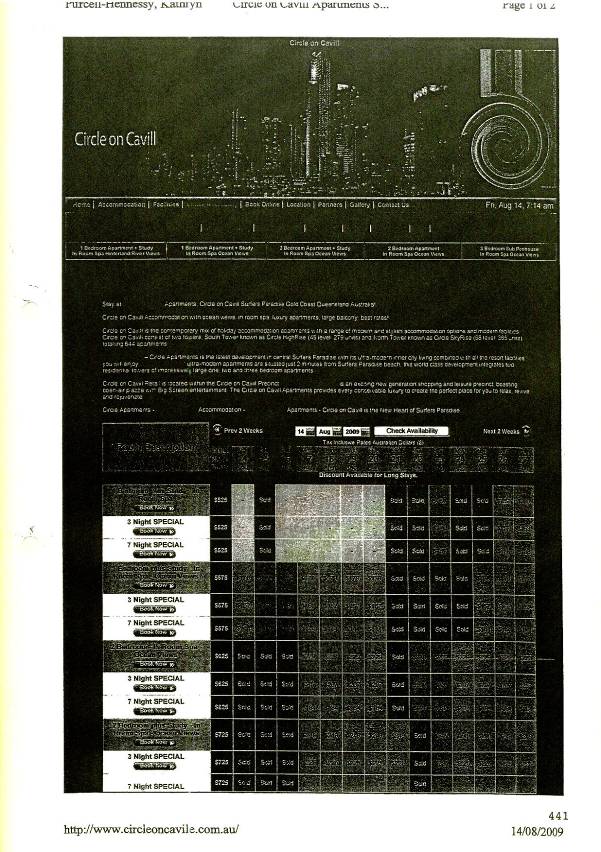

(b) circleoncavillapartments.com.au – Schedule 2

…

(d) circleoncavillretail.com.au – Schedule 3

…

(g) ecircleoncavil.com – redirects to a1goldcoastholiday.com – Schedule 4

(h) ecircleoncavill.com – Schedule 5

(i) ecircleoncavill.com.au – Schedule 6

(j) circleoncavill.mobi – Schedule 7

(k) cavillapartments.com – Schedule 8

(l) circleapartments.com.au – Schedule 9

…

(o) a1goldcoastholiday.com.au – redirects to circleoncavillapartments.com.au – Schedule 10.

It will be noted that, with the exception of (g) and (k) above, all of these domain names, or websites, correlate with the domain names or websites where Tailly admits it used the words “Circle on Cavill” or similar words: see [17] above. While Tailly has made this admission about (h) above, where “Cavill” is spelt with two Ls, it does not appear to have made the same admission about (g) above, where “Cavill” is spelt with one L. In the absence of such an admission, I find, based on the evidence of Mr Lattimore (see Schedule 4 attached), that Tailly used the words “Circle on Cavill” in the domain name in (g) above: ecircleoncavil.com. As to the domain name described in (k) above: cavillapartments.com, I find that the corresponding domain name listed in [17] above has included the country code domain “.au” in error. I do so for two reasons. First, the domain name “cavillapartments.com” is clearly shown on the web page in Schedule 8 attached. Secondly, in her written submissions, Ms O’Gorman referred to this domain name as “cavillapartments.com” rather than “cavillapartments.com.au”.

41 Mr Lattimore also conducted Google searches using the words “Circle on Cavill”, or similar terms, eg “Circle at Cavill” or “Circle on Cavill Apartments”. He then summarised the organic search results he obtained that included a domain name or website held by Tailly, or Mr Stephan Grant, by reference to the ranking that domain name or website achieved in the organic search results. The summary revealed the following:

(a) “Circle on Cavill Apartments” – ranks number 4, 5, 10, 11, 13, 15 and 18;

(b) “Circle on Cavill” – ranks number 4, 7, 10, 12, 16 and 18;

(c) “Circle on Caville” – ranks number 6 and 16;

(d) “Circle on Cavil” – ranks number 5, 10, 14, 17, 18 and 20;

(e) “Circle on Cavill Surfers Paradise” – ranks number 7, 9, 13 and 17;

(f) “Circle Cavill” – ranks number 4, 9, 10, 16, 17 and 19;

(g) “Circle at Cavill” – ranks number 4, 9, 12, 17, 18 and 20;

(h) “Circle in Cavill” – ranks number 4, 9, 12, 14, 17, 18 and 20;

(i) “Circle on Cavill Accommodation” – ranks number 4, 5 and 9.

42 It is apparent from this summary that the Tailly domain names and websites obtained rankings as high as 4 on the first page of organic search results. These rankings are obviously well within the coveted position of the first half of the first page of the organic search results. Mr Lattimore gave evidence that Tailly had achieved these high rankings by using the words “Circle on Cavill” frequently in the source codes underlying its various websites. To provide an example to demonstrate how Tailly had done this, Mr Lattimore went to the website linked to the domain name www.circleoncavillapartments.com.au. He then examined the source code underlying this website. He produced a copy of the beginning of that source code in evidence. It was as follows:

"<title>Circle On Cavill : Surfers Paradise Apartments Gold Coast</title>

<meta name"=description" content="Circle on Cavill Surfers Paradise, Circle on Cavill Apartments Surfers Paradise gold coast. Book directly with Circle on Cavill Surfers Paradise Gold Coast.">

<meta name="keywords" content="Circle on Cavill, Circle on Cavill Apartments, Circle on Cavill surfers paradise, Circle on Cavill Apartments gold coast, Circle Apartments.">"

43 It will be noted that the words “Circle on Cavill” are used in the title line and then seven times in the meta information, or metatags. The complete source code extends over nine pages. In those nine pages, the words “Circle on Cavill”, by themselves, or the words “Circle on Cavill Apartments”, are repeated in excess of 250 times.

44 Furthermore, Mr Lattimore conducted Google searches of the same, or similar, key words to those in [41] above to ascertain what paid advertising Tailly had undertaken with Google using the words “Circle on Cavill”. The organic search results he obtained showed that the Tailly domain name, circleoncavillapartments.com.au, appeared at the top, or on the right hand side, of the first page of each of the organic search results as a sponsored, or paid, link. This occurred, notwithstanding, as noted above (at [29]), that Google does not permit Tailly, or anyone else, to use the exact words of Mantra’s registered trade mark Circle on Cavill. However, as also noted above, this does not prevent Tailly from using similar words, or parts of the words, or even extensions of those words in domain names, eg “Circle on Cavill Apartments”.

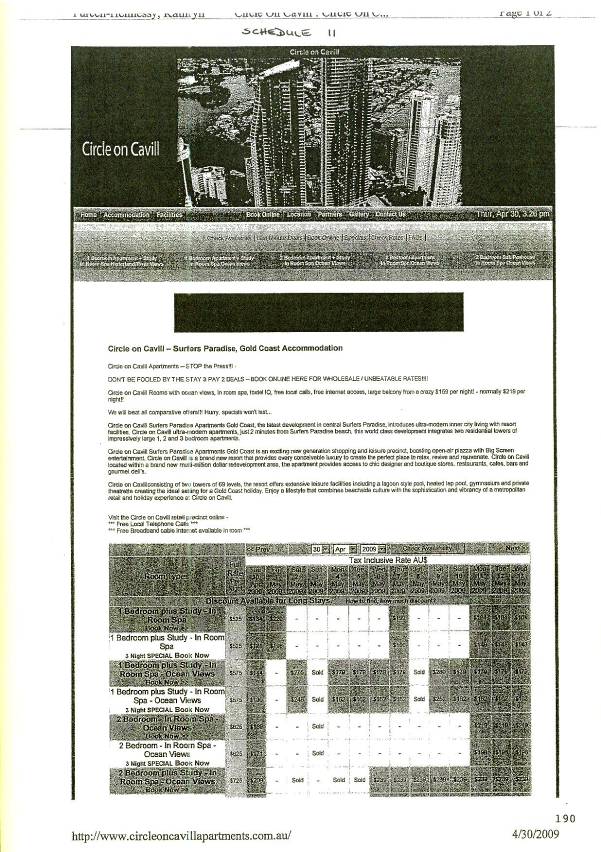

45 I should also note that Ms Kathryn Purcell-Hennessy, a solicitor employed at Mallesons Stephen Jaques, the solicitors for Mantra, gave evidence that she had undertaken internet searches in relation to various domain names and websites held or operated by Tailly on various occasions between 30 April 2009 and 23 November 2009. Whilst there are some differences in the wording on some of the websites, the banner headings, the layout and the substantive content of the various websites examined by Ms Purcell-Hennessy, I find that they are relevantly either identical to, or very similar to, those described in Mr Lattimore’s evidence. To demonstrate this, I have attached as Schedules 11 and 12 to these reasons the front page of the websites linked to the domain names circleoncavile.com.au (Schedule 1 in [40] above – Schedule 11 attached) and circleoncavillapartments.com.au (Schedule 2 in [40] above – Schedule 12 attached) as at the dates Ms Purcell-Hennessy conducted her searches: 30 April 2009, 7 May 2009, 14 August 2009, 17 August 2009, 1 September 2009, 20 November 2009 and 23 November 2009. Because this is so, and despite the fact that Ms O’Gorman tended to rely upon the results of the searches conducted by Ms Purcell-Hennessy rather than those of Mr Lattimore, I do not consider it necessary to set out a summary of Ms Purcell-Hennessy’s extensive evidence about her internet searches.

Contentions and relevant legal principles

46 Before turning to consider the effect of this evidence in relation to the infringement issue, it is convenient to identify the relevant legal principles. I will begin by setting out a brief summary of the main contentions of the parties on this infringement issue.

47 Ms O’Gorman, for Tailly, submitted that there were three reasons why Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill” did not constitute use as a trade mark. First, she submitted the only purpose for which Tailly used the words was to describe a significant feature of the apartments that it sub-let, viz that the apartments were located in the complex named Circle on Cavill which was situated at Surfers Paradise on the Gold Coast. Secondly, she submitted that Tailly did not use the words “Circle on Cavill” in a way that distinguished Tailly’s services from the services of any other persons, including Mantra, who let apartments in the Circle on Cavill complex. And, thirdly, she submitted that Tailly did not use the words “Circle on Cavill” to associate Tailly’s services with the services that Mantra offers. Ms O’Gorman also submitted that, in any event, the use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in a metatag in the source code for a website did not constitute use of those words as a trade mark.

48 Mr Crowe SC, for Mantra, submitted that the correct question at this stage was whether Tailly used the words “Circle on Cavill” as a “badge of origin” to indicate a connection between Circle on Cavill and the services provided by Tailly. Conversely, he submitted that the question is not whether Tailly used the words so as to indicate a connection between Tailly’s services and those of Mantra. In making these submissions, he relied upon the Full Court decision of Coca Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 7 (“Coca Cola”). Mr Crowe SC accepted that, insofar as Tailly used the words “Circle on Cavill” to describe the building Circle on Cavill and where it was located, or even to claim that Tailly had apartments to let in the Circle on Cavill building, it was not using those words as a trade mark. However, Mr Crowe SC submitted that when one considers Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in context, it is clear that it was using those words as a badge of origin, ie, that it was the origin of the trade mark.

49 As to the use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in metatags, Mr Crowe SC stated that the applicants did not seek a finding that such use amounted to an infringement of their trade mark. Instead, he said the applicants relied on the use of the words of the trade mark in metatags to negative the good faith element of the defence raised by the respondents under s 122(1)(b) (see Issue 2 below). Otherwise, Mr Crowe SC submitted that the combination of the use of those words in the domain names and on the various websites, amounted to the use of those words as a trade mark.

50 From these submissions and the various authorities I was referred to by counsel, I take the relevant legal principles on this infringement issue to be as follows:

(a) Use as a trade mark is use of the mark as a “badge of origin” in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods or services and the person who applies the mark to those goods or services. It has been described as “planting a flag to identify the fact you are in a particular trader’s territory”: see Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Limited v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Limited (1991) 30 FCR 326 (“Johnson & Johnson”) at 342 per Burchett J and 347 per Gummow J, Coca Cola at [19] and Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd (2008) 76 IPR 161 (“Global Brand”) at [45] per Sundberg J;

(b) In determining whether a sign is used as a trade mark, one does not ask whether the sign indicates a connection between the alleged infringer’s services and those of the registered owner. Instead, one asks whether the alleged infringer has used the sign so as to indicate that the origin of the services was in itself: see Coca Cola at [20] and [28] and Global Brand at [47];

(c) The latter question is the question that has to be determined at this threshold stage: see Coca Cola at [30]. The determination of this threshold question only involves an examination of the impugned mark, not the registered trade mark: Global Brand at [49];

(d) In assessing whether the alleged use is use as a trade mark, the Court is required to examine the purpose and nature of the use in its context. This includes factors such as the positioning of the sign, the type of font used, the size of the words or letters, and the colours which are used, as well as how the sign is applied to the advertising material in question: see The Shell Company of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 (“The Shell Company”) at 422 per Kitto J; Johnson & Johnson at 347 per Gummow J; Sportsbreak Travel Pty Ltd v P & O Holidays Ltd (2000) 50 IPR 51 (“Sportsbreak”) at [14] per Burchett J; Christodoulou v Disney Enterprises Inc (2005) 156 FCR 344 at [35] per Crennan J; and Anakin Pty Ltd v Chatswood BBQ King Pty Ltd (2008) 250 ALR 620 at [60] to [61] per Branson J;

(e) This assessment of the purpose and nature of the use of the sign is objective, ie by reference to what a member of the public could be expected to understand by its use: see The Shell Company at 425 per Kitto J; Sportsbreak at [14] per Burchett J and Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185 (“Aldi”) at [76] per Lindgren J;

(f) The words (of a mark) may be used to describe the goods or services concerned, but still serve as a badge of trade origin: see Johnson & Johnson at 343 and 347 and Coca Cola at [26]. The question is whether consumers are being invited to purchase the services on the basis that they are to be distinguished from that of other providers of those services partly because they are described by the words used: see Johnson & Johnson at 347 to 348 per Gummow J, Coca Cola at [26]; and cf Aldi at [23] per Hill J and [60] per Lindgren J;

(g) It has been doubted whether the mere registration of a domain name containing the words of a trade mark constitutes the use of those words as a trade mark for the purposes of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act: see CSR Ltd v Resource Capital Australia Pty Ltd (2003) 128 FCR 408 (“CSR Ltd”) at [42] per Hill J and the cases referred to. However, if the registered domain name is linked to a website that contains advertising material that promotes goods or services in relation to which the trade mark is registered, this combination of use could constitute use as a trade mark under s 120 of the Trade Marks Act. This is all the more so if the advertising material on the website also uses the words of the trade mark to promote the goods or services concerned. In considering whether these situations constitute trade mark use, it will be necessary to apply the general principles set out above to the particular circumstances: see the discussion in Shanahan at [115.1050].

Consideration

51 It is convenient to begin by dealing with Tailly’s use of the sign “Circle on Cavill” in its registered domain names and/or the websites to which they are linked. In CSR Ltd, Hill J referred to the One in a Million case and observed (at [42]) (case references excluded) that:

… It is one thing to say that a cyber squatter who registers a name intending to sell that name to the owner of a trade mark or threaten a sale to a competitor if the owner does not come up with the money may have registered the name as an instrument of fraud, and thereby be guilty of the tort of passing off as was held by the Court of Appeal in England. … But it is another thing to say that for the purposes of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) RCA used the domain name as a trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which CSR had registration or for that matter closely related to either goods or services referred to in the CSR registrations. No doubt it can be said that the interests of CSR were likely to be adversely affected by the acts of RCA but that is not sufficient to constitute an infringement. There could be a threatened infringement if one were to take seriously the suggestion that RCA intended to engage in the sugar trade. Clearly, however, that was not the real intention of RCA or Mr Boland, who at no time used or intended to use the domain name as trade marks in relation to either goods or services.

52 The first situation of a threatened sale of the domain name arose in the One in a Million case, but it does not arise in this case, at least in relation to this infringement issue. The related services difficulty identified by Hill J also does not arise in this case because Tailly admits that it used the sign, “Circle on Cavill” or similar words, in its various domain names in relation to the services in respect of which the “Circle on Cavill” word mark is registered: see [16] and [17] above. Tailly also admits it used the words “Circle on Cavill” or similar words in eight of the 10 critical domain names, or websites, listed in [40] above. In addition, I have found that Tailly used those words in the domain name “ecircleoncavil.com”: see [40] above. The remaining domain name listed in [40]: “(o) a1goldcoastholiday.com.au” does not include those words, but it links to another domain name that does, ie circleoncavillapartments.com.au.

53 As I have noted above (see [50(g)]), this combined use of a sign in domain names and the web pages to which they are linked is the type of situation that could well amount to the use of that sign as a trade mark. Whether it does largely depends on the use that is made of the sign on the linked website. Before considering that use more closely, it is convenient to address the three reasons Tailly advances for denying that its use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in this way, did not amount to trade mark use.

54 Tailly’s third reason (there was no association with Mantra’s services: see [47] above) can be disposed of briefly. The authorities are clear (see [50(b)] above) that, at this threshold stage, the assessment only involves an examination of Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill”, ie the impugned mark, to determine whether Tailly has used it to indicate that it was the origin of the services covered by the trade mark. One does not ask, as Tailly submits, whether its use of the sign Circle on Cavill indicates a connection between its services and the corresponding services of Mantra.

55 The other two reasons advanced by Tailly (see [47] above) require a closer examination of the critical websites because they both rely upon claims that its use of the words “Circle on Cavill” was descriptive, viz to describe the Circle on Cavill complex, where it was located and the range of services Tailly had to offer there, and that its use was in no way to distinguish its services from other providers of holiday accommodation in the Circle on Cavill complex. In support of the latter reason, Tailly points to the statements on its website that it says make it clear there is a range of other providers offering apartments to let in the complex, eg “We will beat all comparative offers” and “Find a better rate, we’ll beat it”.

56 I consider both of these reasons must be rejected. I will deal first with Tailly’s claim it only made a descriptive use of the words. It is clear that Tailly’s websites bearing the words “Circle on Cavill” do, indeed, contain an amount of descriptive material about the Circle on Cavill complex and where it is located. For example, on the website associated with the domain name circleoncavillapartments.com.au (see Schedule 2 attached), approximately one-third of the way down the first page, the complex is described as follows:

The precinct known as Circle on Cavill, Surfers Paradise consists of two magnificent towers of 69 levels known as the Circle HighRise (South Tower) and the Circle SkyRise (North Tower). The apartments are ultra-modern and located just 2 minutes from Surfers Paradise beach. Select from a range of large 1, 2, 3 bedroom sub penthouse apartments.

Our apartments at Circle on Cavill have been officially rated 4.5 star by AAA Tourism.

…

Circle on Cavill offers extensive leisure resort facilities including three swimming pools, heated lap pool, spa, sauna, steam room, gymnasium, BBQ area, children’s playground and private theatrette creating the ideal setting for a perfect gold coast holiday. Enjoy a beachside culture lifestyle combined with the sophistication and vibrancy of a metropolitan retail and holiday experience at the Circle on Cavill.

57 However, when one looks at the uses Tailly has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” on its websites as a whole and in context, I consider this descriptive use of those words pales into insignificance by comparison to the other use Tailly has made of those words. Moreover, I consider the other use Tailly has made of those words clearly constitutes trade mark use. As to the descriptive use of those words, when one looks at each website, it is clear that the descriptive use appears in small font in the form of prose in the body of the website. On the other hand, the other use Tailly has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” appears at the head of the first page of each website in a banner-style heading in large font combined with a depictive background. Thus, when one compares the size, positioning and format of the descriptive use of the words “Circle on Cavill”, with the size, positioning and format of the banner heading use of those words, I consider that a member of the public, taking an objective view of the matter, would conclude that the primary, or most significant use of those words is as a badge or emblem to indicate that Tailly is the origin of the accommodation letting services at Circle on Cavill.

58 Furthermore, I consider this badge of origin use of the words is accentuated on at least five of Tailly’s websites. First, on the websites at Schedules 2, 3, 5 and 10 (and, to a lesser extent, 6 and 9), in addition to their use in the banner heading as described above, the words have been used frequently and gratuitously in standalone format without any immediate connection with any descriptive content.

59 Secondly, the website shown in Schedule 7 contains no descriptive material at all and simply advertises Tailly’s telephone numbers under a banner heading using the words Circle on Cavill. I cannot see how Tailly can claim that this use of those words was either descriptive or, for that matter, non-distinguishing (see below).

60 For these reasons, I reject the first of Tailly’s reasons, viz that it only made descriptive use of the words, “Circle on Cavill” on its websites. I consider it clearly made banner headline, “badge of origin”, trade mark use of those words.

61 The other reason that Tailly advances is that its use of the words “Circle on Cavill” on its websites was a non-distinguishing use. It includes in this its price comparisons and price guarantees. Again, it is clear that Tailly’s websites do, indeed, use the words “Circle on Cavill” to promote the comparative price advantages of the range of apartments Tailly has to offer in the Circle on Cavill complex over other (unstated) providers of accommodation services in the complex. For example, on the circleoncavillapartments.com.au website referred to above, the range of apartments Tailly has available to let is described. As well, near the top of the first page, below the banner heading, it states:

Circle on Cavill – find a better rate, we’ll beat it!!!

Holiday apartments at Circle on Cavill’s EXCLUSIVE RATE GUARANTEE – We will beat all comparative offers – call 1300 484 668 …

62 While it is clearly implicit in the price comparisons on Tailly’s websites that there are other providers offering similar accommodation letting services at Circle on Cavill, I consider it is significant that none of those other providers has been identified by name and no direct cost comparison is made between Tailly’s accommodation services and those of any other provider. In other words, the other providers are simply treated as an anonymous group of competitors. It follows, in my view, that this general advertence to the existence of other providers of accommodation services at Circle on Cavill does not amount to a non-distinguishing use of the words. Moreover, as I have already observed above, I consider its other use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in the banner headings to its websites amounts to a clear distinguishing use of those words to indicate to the public that Tailly is the true origin of the accommodation services at the Circle on Cavill complex. In other words, to adopt words of Williams J in Mark Foy’s Limited v Davies Coop and Company Limited (1956) 95 CLR 190 (“Mark Foy’s”) (at 205):

… The public are not being invited to compare the “Exacto” goods of the defendants with the “Tub Happy” goods of the plaintiff. They are being invited to purchase goods of the defendants which are to be distinguished from the goods of other traders partly because they are described as “Tub Happy” goods.

63 Furthermore, I consider that this conclusion applies equally to the two websites where Tailly has attempted to inform the public that it is not the on-site manager at Circle on Cavill. This is so because, in doing so, I do not consider it has removed or ameliorated the distinguishing use it has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” as described above. In the website shown on Schedule 4 attached, the words “Circle on Cavill” appear in the banner heading at the top of the first page of the website, below the words “a1 gold coast holiday” represented in logo form. They are also surrounded by other words as follows:

Private Apartments at

Circle on Cavill

Surfers Paradise Apartments Gold Coast

64 Then, the body of the web page is headed:

Apartments @ Circle on Cavill Surfers Paradise

Circle on Cavill Holiday Apartments - A1 Gold Coast Holiday

65 And, the first paragraph of the prose in body of the web page states:

A1 Gold Coast Holiday is not associated with the OnSite Manager at Circle on Cavill, A1 Gold Coast Holiday privately manages apartments at Circle on Cavill and as such are able to offer accommodation at discounted rates!

66 The website shown at Schedule 8 also contains the words “Circle on Cavill” in the banner heading to the first page. It will be noted that the font used in that banner heading is much larger than that on the web page shown at Schedule 4. The body of the web page is headed:

A1 Gold Coast Holiday Apartments at ‘The Circle on Cavill Resort’.

The first paragraph of the prose immediately below that heading is in identical terms to the first paragraph of the web page at Schedule 4: see [65] above.

67 In my view, neither the words in the body of both these websites, nor the addition of the A1 Gold Coast Holiday logo and other words to the banner heading at the top of the website shown at Schedule 4, serves to overcome the distinguishing “badge of origin” use Tailly has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” to indicate that it is the origin of the accommodation services at Circle on Cavill. Again, in the words of Williams J in Mark Foy’s (at 205) quoting Lord Greene MR in Saville Perfumery Ltd v June Perfect Ltd (1939) 58 RPC 147 at 161:

… “In an infringement action, once it is found that the defendant’s mark is used as a trade mark, the fact that he makes it clear that the commercial origin of the goods indicated by the trade mark is some business other than that of the plaintiff avails him nothing, since infringement consists in using the mark as a trade mark, that is, as indicating origin”.

68 Williams J added:

Needless to say, if the defendant uses the words of the plaintiff’s trade mark as indicating origin it is still an infringement notwithstanding that the defendant always adds his own name.

Conclusion

69 Taking into account all these matters, I consider a member of the public looking at Tailly’s various domain names and the contents of the various websites to which they are linked, would conclude that this combined use of the words “Circle on Cavill” as described above amounted to their use as an emblem or a badge of origin for the accommodation services Tailly was offering at the Circle on Cavill complex. It follows that I have concluded that Tailly has made all these uses of the words “Circle on Cavill” as a trade mark, contrary to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act. I should add two riders to this conclusion. First, it does not apply to those quite separate parts of the various websites where Tailly has only used those words descriptively: see, for example, [57] above. Secondly, it does not apply to the domain name a1goldcoastholidays.com.au which obviously does not contain those words, or any variation of them.

2. did tailly use the words “Circle on Cavill” in good faith to indicate the geographical origin of the accommodation services it was offering at the Circle on Cavill complex?

Relevant legislative provision

70 Section 122(1) of the Trade Marks Act provides a defence to Tailly if its use of a Mantra trade mark occurred in various defined circumstances. Tailly has sought to rely upon the circumstances described in s 122(1)(b)(i). That sub-section provides:

In spite of s 120, a person does not infringe a registered trade mark when:

(b) the person uses a sign in good faith to indicate:

(i) the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of goods or services; …

The issues that arise

71 In this case, this provision raises two sub-issues as follows:

(a) Did Tailly use the sign to indicate the geographical origin of the accommodation letting services it was offering at the Circle on Cavill complex?

(b) Did Tailly use the sign in good faith?

Tailly bears the onus of establishing both of these matters.

“Geographical origin … of … services”

72 The first sub-issue requires me to determine the meaning of the words “geographical origin … of … services”. Before the passage of the Trade Marks Act in 1995 (“the 1995 Act”), s 64(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) (“the 1955 Act”) provided a similar defence to that offered by s 122(1)(b). It applied to: “The use in good faith by a person of a description of the character or quality of his goods or services”. The words “kind … quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin …” were added by the 1995 Act. Apart from identifying that the general purpose of the 1995 Act was to allow Australia to comply with its World Trade Organisation obligations, the Second Reading Speech for the 1995 Act does not shed any light on why these specific words were included in the new section. However, it seems likely that they may have been adopted from the equivalent section of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (UK) (“the UK Act”), which had been passed by the UK Parliament a year earlier. Section 11(2)(b) of the UK Act provided as follows:

(2) A registered trade mark is not infringed by

(b) the use of indications concerning the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, at time of production of goods or of rendering of services, or other characteristics of goods or services, or …

73 This section was inserted in the UK Act to implement the European Trade Marks Directive (First Directive 89/104/EEC of the Council of 21 December 1988) relating to trade marks. Article 6(1)(b) of that Directive was as follows:

(1) The trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from using, in the course of trade,

(b) indications concerning the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, time of production of goods or of rendering the service, or other characteristics of goods or services …

74 Whilst this historical material may reveal the genesis of the words “geographical origin”, it does not assist in determining their meaning. In that task, it is the language of the provision that is of fundamental importance. As well a consideration of the context, including the general purpose and policy of the provision may be called for: see Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41 at [47] and Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [69].

75 Ms O’Gorman submitted that the words “geographical origin … of … services” in s 122(1)(b) do not refer to the place from which the service provider originates, but rather they referred to the place from which the services originate. She submitted that Tailly offers the services of sub-letting apartments located in the Circle on Cavill complex and, for that reason, when it used the words “Circle on Cavill”, it used them to indicate the geographical origin of those sub-letting services. She submitted a complex comprising two high rise buildings, or a “vertical village” as one of the witnesses described it, can be regarded as a geographical point or feature in the urban setting of Surfers Paradise.

76 Mr Crowe SC pointed to the immediately preceding provision, s 122(1)(a)(i), which he submitted dealt with the more specific situation of a trader using a trade mark in good faith as “the name of the person’s place of business”. He gave, as an example of this, the decision in MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd (1998) 90 FCR 236 (“MID Sydney”) at 251, where the Full Court observed that traders conducting their business from the Chifley Tower building in Sydney would not have infringed the plaintiff’s trade mark, ie Chifley Tower, if they used that name in good faith as the name of their place of business. However, he submitted, Tailly could not rely upon s 122(1)(a) because the Circle on Cavill complex was not its place of business. Thus, he submitted, it had to resort to the “geographical origin” provision in s 122(1)(b). Given that the specific situation of a place of business is dealt with in s 122(1)(a), he submitted that the word “geographical” in s 122(1)(b) must refer to the broader concepts of place such as country, state, region, city, town or suburb from which services originate. He gave, as an example, “Roma tomatoes”.

77 It can be seen from these submissions that Mantra places a greater emphasis on the broader concept of place which, it submits, comes from the meaning of the word “geographical”, whereas Tailly places a greater emphasis on the source of the service activity which, it submits, flows from the complete phrase “geographical origin … of … services”. As pointed out above, to determine the correct meaning of these words, it is necessary to consider the language used and the purpose and context of the provision.

78 The word “geographical” is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary (4th ed, 2005) to mean:

1. of or relating to geography. 2. referring to or characteristic of a certain locality, especially in reference to its location in relation to other places.

79 And the word “origin” is relevantly defined to mean:

1. that from which anything arises or is derived; the source: to follow a stream to it origin. 2. rise or derivation from a particular source: these and other reports of like origin. 3. the first stage of existence; the beginning: the date of origin of a sect. 4. birth; parentage; extraction: Scottish origin.

80 The purpose of s 64(1)(b) of the 1955 Act was identified by Lindgren J in Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Pepsi Co (Aust) Pty Ltd (1995) 132 ALR 286 (“Kettle Chip Co”) (while this decision was overturned on appeal, that did not affect his Honour’s treatment of s 64) as protecting a trader who “chances to use a word or words which trespass upon another’s trade mark of the existence of which the trader was unaware”: at 304. Dealing with the same section, Hill J observed at first instance in Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd (1990) 18 IPR 309 (at 341):

It is consistent with the policy underlying the section that the mark said to be used bona fide is a description of the character or quality of the goods be a word that has passed into the English language. The Act was not intended to ‘enclose and appropriate as private property certain little scripts of the great open common of the English language’: see Mark Foy’s Ltd at 201.

81 To similar effect, see Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Kona Coffee Roastery & Equipment Supplies Pty Ltd (1993) 28 IPR 176 (“Cantarella”) at 178 per Einfeld J. Because both sections are substantially similar in their effect, I consider these observations apply with equal force to s 122(1) of the 1995 Act.

82 As to context, when s 122(1)(b) is read in the context of s 122 as a whole, I consider the specific concept of place, ie “place of business”, described in s 122(1)(a) does provide support for Mr Crowe SC’s submission that the word “geographical” in s 122(1)(b) is intended to describe a broader concept of place such as a country, region or town. The decision in Angove’s Pty Ltd v Johnson (1982) 66 FLR 216 provides an example of this “place of business” provision. In that case, a Full Court of this Court held by majority that the respondent was entitled to use the words “St Agnes Liquor Store” in the name of its business in the Adelaide suburb of St Agnes, notwithstanding that the plaintiff held a registered trade mark for the words “St Agnes”. The Court held that this usage of the words fell within the “name of place of business” in s 64(1)(a) of the 1955 Act, which is equivalent in effect to s 122(1)(a) of the 1995 Act. As Mr Crowe SC pointed out, Tailly cannot rely upon this “place of business” provision and is forced to resort to the “geographical origin” provision of s 122(1)(b) because the Circle on Cavill complex is not its place of business.

83 In my view, the difficulties for Tailly on this issue lie, not so much with the word “origin” as indicating the source of its services, but rather in having the word “geographical” construed to refer to a specific place, such as the Circle on Cavill apartment complex, when the ordinary meaning of the word “geographical” refers to a broad locality and the Trade Marks Act deals with specific places, ie places of business, in the immediately preceding subsection.

84 There is another aspect that I consider compounds Tailly’s difficulties. In Clark Equipment Company v Registrar of Trade Marks (1964) 111 CLR 511 (“Clark Equipment”), albeit in relation to a challenge to the registration of a trade mark, Kitto J identified the “common right of the public to make honest use of words forming part of the common heritage” (at 514). He instanced the name of a place or an area, “whether it be a district or a county, a state or a country” (at 515).

85 These observations were considered by the Full Court in MID Sydney. As noted above, that case dealt with a large city office building: the Chifley Tower comprising 42 storeys. One of the questions that arose in that case is similar to the argument put by Ms O’Gorman: that the Circle on Cavill building is so large and prominent that it can be referred to as a geographical location in Surfers Paradise. In MID Sydney, the appellant was the owner of the Chifley Tower and it had a registered trade mark comprising the words “Chifley Tower” in respect of property maintenance services. The respondents operated a number of hotels in five capital cities in Australia and wanted to use the name “Chifley” in the names of some of those hotels. One of the proposed names was “Chifley on the Wharf” for a hotel situated on the Finger Wharf at Woolloomooloo in Sydney. Whilst the case did not involve a defence under s 122(1) of the Trade Marks Act, it did consider some of the issues raised by Tailly in this case.

86 After quoting at length from the decision of Kitto J in Clark Equipment (set out in part at [84] above), the Full Court said (at 250 to 251):

We rather doubt that any indication is to be found in the judgment of Kitto J in Clark Equipment that he would have regarded a large privately owned office building as analogous to a large and important industrial town or district or to a smaller town or district which is a seat of manufacture of goods of a particular kind. To say that is not conclusively to answer Touraust’s submission. But it does suggest that it may not be so simple a matter as to say that, as in a large town, so in a large office building, there will be found numerous traders who may wish to describe their goods or services by reference to their place of business.

MID acquired a building approaching completion and chose a name for it; at about the same time MID applied for the first of its registered marks in relation to property management services intending, no doubt, to provide those services, principally if not exclusively, in relation to the building. The Chifley Tower is not part of the common heritage in the sense that a town, suburb or municipality is. Chifley Plaza perhaps might answer that description, but the registered trade mark does not incorporate that expression. …

… Moreover, it cannot be said that it is likely that a trader operating from The Chifley Tower will, without impropriety, wish to use the name “Chifley Tower” in relation to property management services (other than as the trader’s place of business). The position is different from that of a town, suburb or municipality, since it could reasonably be expected that traders might wish to use the names of those geographic locations in connection with their services. (emphasis added)

87 In my view, these observations suggest that the word “geographical” in s 122(1)(b) was intended to protect the common right of the public to use words forming part of the common heritage, specifically, the name of a country, region, city or town. On the other hand, they suggest that word was not intended to extend to a large privately owned residential apartment building like the Circle on Cavill complex that could not be said to be a part of the common heritage, any more than it did to the large privately owned city office building in the MID Sydney case. The borderline exception identified in MID Sydney was where a plaza or other public space adjoining such a building had become a part of the common heritage. There is nothing to suggest that arises in this case.

88 Taking into account all these matters, I consider the words “geographical origin … of … service” in s 122(1)(b) are to be construed to refer to the name of a country, region, city, town or similar geographical area from which a trader’s goods or services have been derived, but not to refer to a privately owned building situated within such a city or town, such as the Circle on Cavill complex in this case.

89 This conclusion is sufficient to deprive Tailly of a defence, relying upon s 122(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act. However, both counsel asked me to consider the other sub-issue that I have identified above, viz good faith, so I will proceed to do so.

Good faith

90 I will begin by referring to a submission made by Ms O’Gorman as to the matters I can, and cannot, rely upon in determining this sub-issue. She submitted that the requirement of good faith relates only to the purposes for which Tailly used the sign and not to any other aspect of its alleged behaviour. The other alleged behaviour Ms O’Gorman was referring to included four incidents that Mr Crowe SC focused on in his cross-examination of Mr Grant, Tailly’s Marketing Manager. They were:

(a) the use of the Mantra logo in the “switch” letters of 12 October 2008 and 12 November 2008;

(b) the registering of the domain name “mantra.au.com”;

(c) the alleged attempt to sell that domain name to Mr Jamieson of Mantra in January 2009; and

(d) the use of the word “Mantra” in certain metatags on some of Tailly’s websites.

91 I should add that, with the exception of (c), Tailly admits these incidents: see [7] above.

92 For his part, Mr Crowe SC submitted that all of this conduct could be relied upon to demonstrate that Tailly, and particularly Mr Grant, had a method of operation of blatantly infringing Mantra’s trade marks and only ceasing when he was caught. He submitted this conduct was entirely inconsistent with an honest, or good faith, use of the words “Circle on Cavill”.

93 I have ultimately concluded that Tailly, and particularly Mr Grant, did not use the words “Circle on Cavill” in good faith such as to allow it to rely upon the defence under s 122(1)(b). However, as will appear below, I have reached this conclusion relying upon Mr Grant’s evidence about the circumstances of the use he made of those words and some other aspects, rather than any of the instances of alleged behaviour referred to above.

94 Before turning to consider that evidence, I should briefly identify what the words “good faith” mean in s 122(1)(b). I have already noted (see [80] above) that the general purpose of this provision was to protect a trader who makes a chance use of a word in circumstances where he or she was unaware that the word formed part of another trader’s trade mark, particularly where the word used is a descriptive word in ordinary English usage.

95 A good faith or bona fide use has been described as “something less than fraudulent intention …”: Adrema Ltd v Adrema-Werke GmbH (1858) RPC 323 at 334 and Shanahan at para [85.1810]. It must involve an honest use of the words or sign, but even that may not be sufficient if the defendant used the words or sign to take deliberate advantage of a secondary meaning of the words or sign: see Kettle Chip Co at 304. Thus, in James Watt Constructions Pty Ltd v Circle-E Pty Ltd [1970] 3 NSWR 481 (at 493), Hope J held that the defendant in that case “was well aware that the words had come to have a secondary significance as denoting the plaintiff’s goods” and was therefore not protected by the “good faith” use defence. Furthermore, the defence is likely to fail if particular prominence has been given to the words in question: see Berzins Speciality Bakeries Pty Ltd v Monty’s Continental Bakery (VIC) Pty Ltd (1987) 15 FCR 402 at 407 per Jenkinson J.

96 The expression “good faith” can apply to the honest use of a descriptive word even if it is the same as, or deceptively similar to, a word used in a registered trade mark. Thus, in Mayne Industries Pty Ltd v Advanced Engineering Group Pty Ltd (2008) 166 FCR 312, Greenwood J held that the use of a three dimensional S shape to describe the functional role of a fence dropper was not use of that sign as a trade mark, but as a description of the essential functional feature of the item in question. However, in Cantarella, Einfeld J held that the word “Vitoria”, to indicate the geographical origin of coffee imported from the Port of Vitoria in Brazil, was not used as a descriptive word to describe the character or quality of the goods and, therefore, was not protected by s 64(1)(b) of the 1955 Act in relation to a registered trade mark for the word “Vittoria”. Further, in Caterpillar Loader Hire (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Caterpillar Tractor Co (1983) 77 FLR 139, the Full Court of this Court held that the use of the word “Caterpillar” in the respondent’s business name: “Willoughby’s Caterpillar Loader Hire Service” was not descriptive of the character or quality of the respondent’s services, but constituted use as a trade mark. Franki J observed (at 142) that:

… This section [s 64(1)(b)] is applicable if the acts alleged to constitute an infringement are the use “in good faith of a description of the character or quality of [the defendant’s] … services”. It seems clear that [section] only applies where descriptive words are used descriptively in relation to the goods the subject of the relevant registration.

97 Finally, in Britt Allcroft (Thomas) LLC v Miller (t/as The Thomas Shop) (2000) 49 IPR 7 (at 21), Mansfield J observed that s 122(1)(b) is not intended to encompass the identification of the registered owner of the mark as the source of the goods or services, but is intended to apply to some objective description of the goods or services or a feature often by reference to commonly used and understood qualities.

98 In my view, these authorities identify a large number of reasons why Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill” was not “good faith” use within the provisions of s 122(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act. Each one of these reasons is sufficient to hold that Tailly did not use the sign in good faith within the terms of that section.

99 First, I consider the prominence and widespread nature of Tailly’s use of the words “Circle on Cavill” as described in [57] to [59] above is quite inconsistent with its use of those words in good faith. Secondly, as I have explained above (at [56] to [59]), I do not consider Tailly’s use of the words involved a genuine descriptive use of the accommodation services it was offering to the public. Instead, I consider this descriptive use was used as a stalking horse for its real intentions and that was to use the words quite blatantly to advertise and market its accommodation services at the Circle on Cavill complex. Thirdly, the highly repetitive nature of the use of the words is quite inconsistent with their use being conducted in good faith. There are at least two examples of this. The first is the use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in excess of 250 times as metatags in the source code for the website linked to the domain name www.circleoncavillapartments.com.au: see at [42] to [43] above. While Mantra does not claim that this use constitutes trade mark use, I accept Mr Crowe SC’s submission that it is pertinent to this good faith issue: see at [49] above. I infer from the evidence of Mr Lattimore about the high ranking Tailly was able to obtain in organic search results (see at [41] to [42] above) that Tailly made similar repeated use of the words “Circle on Cavill” in the source codes for all of its websites: see Schedules 1 to 10 attached. This inference is also supported by Mr Grant’s admission in cross-examination that Tailly’s web designer had used the words “Circle on Cavill” repeatedly on the websites “purely for search engine optimisation. Key words obviously have effect in Google rankings”. The second example is Tailly’s frequent and gratuitous use of the words “Circle on Cavill” without any immediate connection with any descriptive content, as described in [58] to [59] (above).

100 Fourthly, it is abundantly clear from Mr Grant’s evidence, when under cross-examination by Mr Crowe SC, that he was well aware that Mantra held registered trade marks incorporating the words “Circle on Cavill” and he was trying to obtain a commercial benefit from the use of those words in Tailly’s advertising and marketing. For example, in cross-examination, Mr Grant was asked why he did not use the words “A1 Gold Coast Holidays” at the top of Tailly’s websites rather than “Circle on Cavill”. Mr Grant responded (emphasis added):

Well, we have a genuine interest in Circle on Cavill. We have 39 apartments there available for consumers to book for accommodation. We found that by using the name of the building, it would give us increased exposure to consumers. Ideally, we want the consumers to find us. We want to provide the consumers with choice and we focus on using the name of the building within our domain name so they are keywords to market our inventory.

101 Later, when Mr Grant repeated his assertion that he was intent on providing choice for the consumer, the following exchange occurred:

MR CROWE: That’s very noble of you, but really as a businessman, it’s all about you earning as much income as possible by utilising the words “Circle on Cavill”, isn’t it?

MR GRANT: There are monetary benefits as well as choice for consumers.