Bennell v State of Western Australia & Ors

STATEMENT OF JUSTICE WILCOX

(This statement is intended to provide some information about the proceedings listed for judgment today and the conclusions reached by the Court. The statement does not cover all aspects of those cases and is not a substitute for the Court’s formal orders or its reasons for judgment. These can be found on the internet at www.fedcourt.gov.au)

Before the Court are six native title cases. Each of them concerns land and waters in, or near to, the Perth metropolitan area.

Five of the cases arise out of applications for a native title determination made by Christopher Robert (‘Corrie’) Bodney. Four of the applications concern particular small areas of land, being land at Hartfield Park, Wannerro Road, Burswood Island and Swanbourne respectively. The fifth application claims a larger area of Perth land, and adjoining coastal waters to the twelve nautical mile limit.

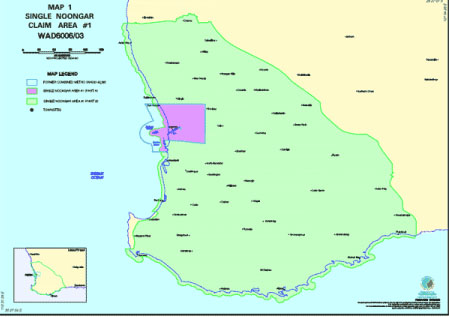

The sixth case arises out of a native title application which has been called ‘the Single Noongar application’. It takes this title from the fact that it was brought to the Court by 80 Aboriginal persons who allege that, in 1829 (the date of European settlement in Western Australia), there was a single Aboriginal community throughout the whole of the south-west of Western Australia. The applicants call this the ‘Noongar community’ and claim the 1829 rules governing the occupation and use of land, throughout the south-west, were the laws and customs of that community. The applicants say the Noongar community continues to exist, and they are part of it; and that its members continue to observe some of the community’s traditional laws and customs (including in relation to land), although with changes flowing from the existence and actions of the white community. The applicants seek a Determination of native title, in favour of all members of the present Noongar community, over a substantial portion of Western Australia. The boundary of the claimed area commences, on the west coast, at a point north of Jurien Bay, proceeds roughly easterly to a point approximately north of Moora and then roughly south-easterly to a point on the southern coast between Bremer Bay and Esperance. The Single Noongar applicants also claim rights and interests over Rottnest and Carnac Islands and coastal waters to a distance of three nautical miles from land.

I will refer to the whole of the land and waters claimed in the single Noongar application as the ‘claim area’.

It will be appreciated that the claim area includes the whole of the Perth metropolitan area as well as centres such as Bunbury, Busselton, Margaret River, Albany, York, Toodyay, Katanning, Merredin and many other towns. However, the applicants excluded from their claim all land and waters over which native title had been extinguished by a past act of the Commonwealth or State governments. The effect of that exclusion is to omit from the application all freehold land in the claim area, and probably most leasehold land. Having regard to the extent of urban development, and intensive farming, in the claim area, the result is that a large proportion of the land within the claim area is unaffected by it.

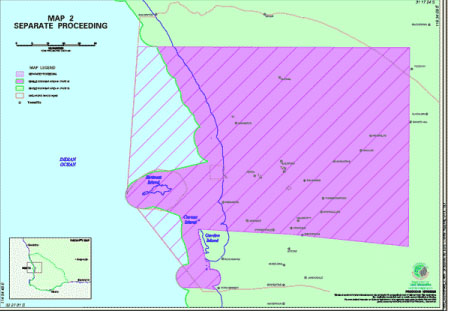

The Court decided to break up the trial of the Single Noongar application by first dealing with an area, in and around Perth, that had been the subject of several earlier, smaller claims and later aggregated together as the ‘Combined Metro claim’. The Court took this course because of the expressed desire of the State (supported by the Commonwealth) for early finality about the question whether native title still survived, in the Perth area. With the agreement of all parties, the Court created a separate proceeding in relation to the Perth area. With the assistance of the parties, the Court framed a separate question in that proceeding, asking whether native title existed in the Perth area and, if so, who were the persons who held the native title and what rights and interests it included.

On 11 October 2005, I commenced a hearing relating to all issues arising out of Mr Bodney’s five applications and the issues raised by the separate question in the Single Noongar application. The Court took evidence over a period of 20 days. On eleven of those days, the Court sat ‘on-country’ at eight different locations: Jurien Bay, Albany, Toweringup Lake near Katanning, Dunsborough near Busselton, Kokerbin Rock and Djuring in the Kellerberrin district and, in Perth, at Swan Valley and in Kings Park. The Court heard evidence from 30 Aboriginal witnesses and five expert witnesses: two historians, two anthropologists and a linguistic expert. A considerable volume of written evidence was also received.

After the conclusion of the evidence, most parties prepared and filed written submissions. On 23 June 2006, I conducted a video-link hearing between Sydney and Perth to discuss aspects of those submissions.

The judgment I will deliver today will deal with all issues arising in respect of Mr Bodney’s applications but, in relation to the Single Noongar applicants, only the separate question. Unless resolved by agreement between the parties, all other issues arising out of the Single Noongar application will be determined by another judge.

In order to obtain a Determination of native title, applicants must establish two fundamental matters:

(i) the identity of the community whose laws and customs governed the use and occupation of the land within the claim area at the relevant date of settlement, in this case 1829;

(ii) that this community continues to exist today, and continues to acknowledge and observe those laws and customs, albeit perhaps in an attenuated or somewhat changed form.

These two issues lay at the heart of the hearing conducted by me late last year and the parties’ subsequent submissions.

As I have said, the Single Noongar applicants claim the laws and customs governing land rights and interests in 1829 were those of a single community whose members were scattered throughout the whole claim area. The case put on behalf of the principal respondents (the State and the Commonwealth) was that there were, at that time, a number (perhaps 12 or 13) of separate communities, each with its own set of laws and customs concerning land. Mr Bodney seemed to contend for a much greater number of land-owning units. If either the principal respondents or Mr Bodney is correct, the Single Noongar application would have to be dismissed; that application is premised on the existence of a single community throughout the whole claim area.

An unusual feature of this case is the wealth of material left to us by Europeans who visited, or resided in, the claim area at, or shortly after, the date of settlement. Several maritime explorers visited the south-west coast and left written accounts of their observations, including of the Aboriginal way of life. In 1826, a military garrison was established at King George’s Sound (modern Albany). Three people associated with that garrison became friendly with local Aboriginal people and left accounts of their observations and the information they had gleaned. In addition to this, several early Swan Valley settlers published accounts of the way of life of Aborigines in the Perth district. This material was supplemented, later in the 19th century, by the writings of other settlers. Very early in the 20th century, Daisy Bates carried out an extensive investigation about Aborigines for the Western Australian government. She left numerous writings, the most significant of which was later published as ‘The Native Tribes of Western Australia’. The cumulative effect of these writings is to provide an insight into Aboriginal life, including Aboriginal laws and customs, in and about the date of settlement, which is possibly not replicated elsewhere in Australia.

I have reached the conclusion that the Single Noongar applicants are correct in claiming that, in 1829, the laws and customs governing land throughout the whole claim area were those of a single community. My principal reasons for that conclusion are as follows:

(i) this conclusion best accords with the information left to us by the early writers;

(ii) I am satisfied, on the evidence of Dr Nicholas Thieberger, an expert in Aboriginal languages, that in 1829 there was a single language throughout the whole claim area, albeit with dialectic differences between various parts of that area;

(iii) the evidence establishes some important customary differences between people living within the claim area and those living immediately outside it (Yamatji to the north and Wongai to the north east);

(iv) there is evidence of extensive interaction between people living across the claim area;

(v) there is no evidence of significant differences within the claim area, as regards the content of laws and customs relating to land.

However, I am satisfied the laws and customs observed in 1829 did not extend to rights and interests over the off-shore islands, such as Rottnest and Carnac Islands, or to the sea below low-water mark. It is clear from the early writings that, in 1829, the south-west Aborigines were not accustomed to use any form of boat. Although the coastal people took fish, they seem to have done so from dry land or places accessible by wading. The off-shore islands are important in Aboriginal legend, but the absence of evidence of physical use means there can be no native title over those areas of land and water.

The second question is whether the Noongar community has continued to exist, as a community, and to acknowledge and observe its traditional laws and customs concerning land.

The Noongar community was enormously affected by white settlement. Aboriginal people were forced off their land and dispersed to other areas. Families were broken up. The descent system was affected by the fact that many children were fathered by white men. Probably in every Noongar family there is at least one white male ancestor. Over a long period, mixed-blood children were routinely taken away from their parents. Notwithstanding all this, and surprisingly to me, members of families seem mostly to have kept in contact with each other, and families with other Noongar families. Many, if not most, children learned at least some Noongar language. Many, if not most, were taught traditional skills, such as for hunting, fishing and food-gathering, and learned traditional Noongar beliefs, including in relation to the spirit world. All of this was graphically illustrated by the witnesses who gave evidence in these cases.

A major issue in the Single Noongar case was whether it can be said the present Noongar community continues to acknowledge and observe its traditional laws and customs concerning land. Undoubtedly, there have been changes in the land rules. It would have been impossible for it to be otherwise, given the devastating effect on the Noongars of dispossession from their land and other social changes. However, I have concluded that the contemporary Noongar community acknowledges and observes laws and customs relating to land which are a recognisable adaptation to their situation of the laws and customs existing at the date of settlement. In particular, contemporary Noongars continue to observe a system under which individuals obtain special rights over particular country – their boodjas – through their father or mother, or occasionally a grandparent. Those rights are generally recognised by other Noongars, who must obtain permission to access another person’s boodja for any traditional purpose. Present day Noongars also maintain the traditional rules as to who may ‘speak for’ particular country.

It follows that the Court should find that native title continues to exist in the area that was made the subject of the separate question. The native title holders are the whole Noongar community, on whose behalf the Single Noongar application was made.

The evidence enables me to identify eight native title rights which have survived and should be recognised. The wording of these rights will need refinement in the light of discussions between the parties or rulings concerning some particular parcels of land. However, I will provide an answer to the separate question that proposes a tentative list.

Mr Bodney’s applications must all be dismissed. I am not satisfied that the Ballarruk and Didjarrak people, through whom he claims, were ever land-holding groups, whether singly or in combination. The better view is that ‘Ballarruk’ and ‘Didjarruk’ were the names of moiety (skin) groups. Also, there is no evidence that the members of Mr Bodney’s claim group are descended from anybody who was a Ballarruk or Didjarruk person alive at or about the date of settlement or that they have continued to acknowledge and observe whatever were the Ballarruk and/or Didjarruk rules about landholding at that time. Finally, Mr Bodney’s claims are inconsistent with my finding that the relevant community in 1829 was the Single Noongar community.

Litigation over native title in the Perth area has gone on for a long time. It has undoubtedly cost much money – mostly taxpayers’ funds. Unless the parties make a determined effort otherwise, it will absorb a lot more money, before it is finished. My answers to the separate question will not themselves end the litigation. There may be an appeal. If there is not, or my finding is sustained on appeal, it would ordinarily be necessary for the State to carry out land tenure searches relating to every one of hundreds of thousands of individual parcels of land in the Perth area. This would be an expensive exercise and take a long time. Any disputes about extinguishment would need to be resolved. It would then be necessary to deal with the remainder of the area covered by the Single Noongar claim, but outside the Perth area which is the subject of the separate question. This also would be an expensive and time-consuming process.

Having regard to these considerations, it seems to me sensible for the parties to discuss the future course of the Single Noongar application, perhaps after disposal of any appeal from my orders but before embarking on land tenure searches or litigation about other matters. It might be preferable for the parties to concentrate their attention on a limited number of larger parcels, in relation to which there is a reasonable likelihood of frequent use by members of the Noongar community. I have in mind areas of undeveloped, or sparsely developed, land; perhaps including national parks. A relatively early determination of rights over those properties may better serve the interests of the Noongar community than a lengthy pursuit of a Determination over every legally available parcel of land; and this course is likely to be both less expensive to the State and conducive to earlier certainty about the status of each particular parcel of land.

It is perhaps important for me to emphasise that a Determination of Native Title is neither the pot of gold for the indigenous claimants nor the disaster for the remainder of the community that is sometimes painted. A Native Title Determination does not affect freehold land or most leasehold land; it cannot take away peoples’ back yards. The vast majority of private landholders in the Perth region will be unaffected by this case.

A Native Title Determination recognises the traditional association of the claimant community with particular land. I recognise the immense symbolic and psychological importance of such recognition. Native Title Determinations have an important part in achieving the reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians to which we all aspire. However, a Determination does not give to the claimant community a right that enables them to sell or lease the land or to develop or use it for any non-traditional purpose.

It follows that a Native Title Determination impedes the use of public land only to the extent of the rights listed in the Determination.

I believe it would be worthwhile, in the present case, for the government and local government respondents carefully to consider to what extent, if at all, their proper functions would be impeded by a formal Determination along the lines suggested by the answer to the separate question I am about to announce. On the other side, it would be worthwhile for the Single Noongar applicants to consider how they might assist to ameliorate any genuine problem. In short, it would be desirable for the parties to engage in some serious thought and discussion before any of them spends more money on legal action.

The formal orders that I make are as follows:

(i) in relation to each of Mr Bodney’s claims (matters WAD 137, 138, 139, 140 and 149 of 1998) I order the application be dismissed;

(ii) in relation to the Perth Metropolitan part of the Single Noongar claim (Part of WAD 6006 of 2003), I order that:

1. The question which was directed, by an order entered on 6 April 2005, to be decided separately from any other question (as amended up to and including 21 December 2005), be answered as follows:

As to para (i):

But for any question of extinguishment of native title by inconsistent legislative or executive acts carried out pursuant to the authority of the legislature under Divisions 2, 2A, 2B or Part 2 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or under the Titles (Validation) and Native Title (Effect of Past Acts) Act 1995 (WA), native title exists in relation to the whole of the land and waters in the area of the separate proceeding, other than off-shore islands and land and waters below low-water mark;

As to para (ii):

The persons who hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the native title in the said land and waters (hereafter ‘the area’) are the Noongar people, as identified in Schedule A of the application for determination filed on 10 September 2003 in matter WAD 6006 of 2003;

As to para (iii):

Without purporting to specify the final terms of a formal Determination of Native Title, the said native title rights and interests are the rights to occupy, use and enjoy the area in the following way:

(a) to access and live on the area;

(b) to conserve and use the natural resources of the area for the benefit of the native title holders;

(c) to maintain and protect sites, within the area that are significant to the native title holders and other Aboriginal people;

(d) to carry out economic activities on the area, such as hunting, fishing and food-gathering;

(e) to conserve, use and enjoy the natural resources of the area, for social, cultural, religious, spiritual, customary and traditional purposes;

(f) to control access to, and use of, the area by those Aboriginal people who seek access or use in accordance with traditional law and custom;

(g) to use the area for the purpose of teaching, and passing on knowledge, about it, and the traditional laws and customs pertaining to it;

(h) to use the area for the purpose of learning about it and the traditional laws and customs pertaining to it.

2. The notice of motion filed by the State of Western Australia on 25 August 2006 be dismissed.

3. The State of Western Australia pay the costs incurred by the Applicants, in the principal proceeding, in relation to the said notice of motion.

4. The costs of other parties in relation to the said notice of motion be reserved for consideration, on application, by French J.

5. The separate proceeding constituted by the order made on 21 December 2005 be remitted to the Western Australian native title provisional docket judge, French J, for the making of such further orders and directions as may be necessary.

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243

NATIVE TITLE – Overlapping claimant applications in respect of land and waters in and around Perth – Applications in respect of five areas made on behalf of Bodney Family Group claim based on descent from Ballarruk and Didjarruk ‘clans’ – Whether these were land-holding groups at sovereignty or moiety groups – Lack of evidence of connection between members of claimant group and any Ballarruk or Didjarruk person alive at sovereignty – Lack of evidence of continued acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs – These claims dismissed - Consideration of separate question arising out of application by the Noongar community in respect of an extensive area of south-west Western Australia – Separate questions related only to land and waters in and around Perth, however the claim was that this was part of a greater area in respect of which the Noongar community held native title rights and interests – Whether at sovereignty the normative system governing the whole of south-west Western Australia was that of a single Noongar community or whether there were a series of separate normative systems of smaller communities – Whether the single Noongar community has continued to acknowledge and observe some traditional laws and customs concerning land and waters – Identification of persons entitled to native title rights and interests – Identification of surviving rights and interests – Discussion of, and orders about, belated motion to strike out single Noongar claim for lack of proper authorisation.

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61, 84, 84C, 85A, 223, 225

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422, followed

Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 followed

Western Australia v Ward (2000) 99 FCR 316 applied

Northern Territory of Australia v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group [2005] FCAFC 135 applied

ANTHONY BENNELL v STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS

PART OF WAD 6006 OF 2003

CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY vSTATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS

WAD 137 OF 1998

CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY vSTATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS

WAD 138 OF 1998

CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY vSTATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS

WAD 139 OF 1998

CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY ON BEHALF OF THE BODNEY FAMILY BALLARUKS v STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS

WAD 149 of 1998

WILCOX J

19 SEPTEMBER 2006

PERTH

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIADISTRICT REGISTRY | PART OF WAD 6006 OF 2003 |

IN THE MATTER OF THE PERTH PORTION OF

THE SINGLE NOONGAR CLAIM NO. 1

| BETWEEN: | ANTHONY BENNELL, ALAN BLURTON, ALAN BOLTON, MARTHA BORINELLI, ROBERT BROPHO, GLEN COLBUNG, KEN COLBUNG, DONALD COLLARD, CLARRIE COLLARD-UGLE, ALBERT CORUNNA, SHAWN COUNCILLOR, DALLAS COYNE, DIANNA COYNE, MARGARET CULBONG, EDITH DE GIAMBATTISTA, RITA DEMPSTER, ADEN EADES, TREVOR, EADES, DOOLANN-LEISHA EATTES, ESSARD FLOWERES, GREG GARLETT, JOHN GARLETT, TED HART, GEORGE HAYDEN, REG HAYDEN, JOHN HAYDEN, VAL HEADLAND, ERIC HAYWARD, JACK HILL, OSWALD HUMPHRIES, ROBERT ISAACS, ALLAN JONES, JAMES KHAN, JUSTIN KICKETT, ERIC KRAKOUER, BARRY McGUIRE, WALLY McGUIRE, WINNIE McHENRY, PETER MICHAEL, THEODORE MICHAEL, SAMUEL MILLER, DIANE MIPPY, FRED MOGRIDGE, HARRY NARKLE, DOUG NELSON, JOE NORTHOVER, CLIVE PARFITT, JOHN PELL, KATHLEEN PENNY, CAROL PETPTERSENN, FRED PICKETT, ROSEMARY PICKETT, PHILLIP PROSSER, BILL REIDY, ROBERT RILEY, LOMAS ROBERTS, MAL RYDER, RUBY RYDER, CHARLES SHAW, IRIS SLATER, BARBARA STAMNER-CORBETT, HARRY THORNE, ANGUS WALLAM, CHARMAINE WALLEY, JOSEPH WALLEY, RICHARD WALLEY, TREVOR WALLEY, WILLIAM WEBB, BERYL WESTON, BERTRAM WILLIAMS, GERALD WILLIAMS, RICHARD WILKES, ANDREW WOODLEY, HUMPHREY WOODS, DIANNE YAPPO, REG YARRAN, SAUL YARRAN, MYRTLE YARRAN APPLICANTS

|

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA, WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FISHING INDUSTRY COUNCIL (INC), CHRISTOPHER (ROBERT) BODNEY, NOONGAR LAND COUNCIL, KEVIN MILLER, CITY OF BAYSWATER, CITY OF BELMONT, CITY OF CANNING, CITY OF FREMANTLE, CITY OF JOONDALUP, CITY OF MELVILLE, CITY OF NEDLANDS, CITY OF SUBIACO, CITY OF WANNEROO, SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA, SHIRE OF MUNDARING, SHIRE OF PEPPERMINT GROVE, SHIRE OF SWAN, TOWN OF BASSENDEAN, TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE, TOWN OF CLAREMONT, TOWN OF COTTESLOE, TOWN OF EAST FREMANTLE, TOWN OF MOSMAN PARK, TOWN OF VICTORIA PARK, CITY OF ARMADALE, CITY OF GOSNELLS, CITY OF PERTH, CITY OF SOUTH PERTH, CITY OF STIRLING, SHIRE OF CHITTERING, SHIRE OF NORTHAM, TOWN OF VINCENT, BILLITON ALUMINIUM (RRA) PTY LTD, BILLITON ALUMINIUM (WORSLEY) PTY LTD, DORAL MINERAL SANDS PTY LTD, HEDGES GOLD PTY LTD, QUADRIO RESOURCES PTY LTD, WESFARMERS PREMIER COAL LTD, ADELAIDE BRIGHTON CEMENT LIMITED, BORAL RESOURCES (WA) LTD, COCKBURN CEMENT LTD, DORRINGTON MARINE SERVICES/YENNETT PTY LTD, NHL PTY LTD, FREMANTLE SAILING CLUB INC, AIRSERVICES AUSTRALIA, AUSTRALIAN MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY, AUSTRALIAN RED CROSS, BGC CONTRACTING PTY LTD, FREMANTLE PORT AUTHORITY, PERTH DIOCESAN TRUSTEES, ROMAN CATHOLIC ARCHBISHOP OF PERTH, THE SHELL COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED, UNITING CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA PROPERTY TRUST (WA), ALOCA OF AUSTRALIA LTD, BLUEGATE NOMINEES PTY LTD, EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY, LIMESTONE RESOURCES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD, M G KAILIS HOLDINGS PTY LTD, TIWEST JOINT VENTURE, TRONOX WESTERN AUSTRALIA PTY LTD, WESFARMERS KLEENHEAT GAS PTY LTD, WORSLEY ALUMINA PTY LTD, YALGOO MINERALS PTY LTD, OPTUS MOBILE PTY LTD, OPTUS NETWORKS PTY LIMITED, TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The question which was directed, by an order entered on 6 April 2005, to be decided separately from any other question (as amended up to and including 21 December 2005), be answered as follows:

As to para (i):

But for any question of extinguishment of native title by inconsistent legislative or executive acts carried out pursuant to the authority of the legislature under Divisions 2, 2A, 2B or Part 2 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or under the Titles (Validation) and Native Title (Effect of Past Acts) Act 1995 (WA), native title exists in relation to the whole of the land and waters in the area of the separate proceeding, other than off-shore islands and land and waters below low-water mark;

As to para (ii):

The persons who hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the native title in the said land and waters (hereafter ‘the area’) are the Noongar people, as identified in Schedule A of the application for determination filed on 10 September 2003 in matter WAD 6006 of 2003;

As to para (iii):

Without purporting to specify the final terms of a formal Determination of Native Title, the said native title rights and interests are the rights to occupy, use and enjoy the area in the following way:

(a) to access and live on the area;

(b) to conserve and use the natural resources of the area for the benefit of the native title holders;

(c) to maintain and protect sites, within the area that are significant to the native title holders and other Aboriginal people;

(d) to carry out economic activities on the area, such as hunting, fishing and food-gathering;

(e) to conserve, use and enjoy the natural resources of the area, for social, cultural, religious, spiritual, customary and traditional purposes;

(f) to control access to, and use of, the area by those Aboriginal people who seek access or use in accordance with traditional law and custom;

(g) to use the area for the purpose of teaching, and passing on knowledge, about it, and the traditional laws and customs pertaining to it;

(h) to use the area for the purpose of learning about it and the traditional laws and customs pertaining to it.

2. The notice of motion filed by the State of Western Australia on 25 August 2006 be dismissed.

3. The State of Western Australia pay the costs incurred by the Applicants, in the principal proceeding, in relation to the said notice of motion.

4. The costs of other parties in relation to the said notice of motion be reserved for consideration, on application, by French J.

5. The separate proceeding constituted by the order made on 21 December 2005 be remitted to the Western Australian native title provisional docket judge, French J, for the making of such further orders and directions as may be necessary.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | WAD 137 OF 1998 |

| BETWEEN:

| CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY APPLICANT

|

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA, TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED, ROBERT BROPHO, ALBERT CORUNNA, GREGORY LAWRENCE GARLETT, KELVIN PATRICK GARLETT, RICHARD WILKES RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | WAD 138 OF 1998

|

| BETWEEN:

AND: | CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY APPLICANT

STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, CITY OF WANNEROO, ROBERT BROPHO, ALBERT CORUNNA, GREGORY LAWRENCE GARLETT, KELVIN PATRICK GARLETT, RICHARD WILKES AND TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | WAD 139 OF 1998

|

| BETWEEN:

AND: | CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY APPLICANT

STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, TOWN OF VICTORIA PARK, ROBERT BROPHO, ALBERT CORUNNA, GREGORY LAWRENCE GARLETT, KELVIN PATRICK GARLETT, RICHARD WILKES AND TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | WAD 140 OF 1998

|

| BETWEEN:

AND: | CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY APPLICANT

STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA, WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FISHING INDUSTRY COUNCIL (INC), FREMANTLE PORT AUTHORITY, TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE, RAYMOND ANDREW YUKICH, PAMELA RAE YUKICH AND TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | PART OF WAD 149 of 1998

|

| BETWEEN:

| CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY ON BEHALF OF THE BODNEY FAMILY BALLARUKS APPLICANTS

|

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA, WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FISHING INDUSTRY COUNCIL (INC), AIRSERVICES AUSTRALIA, AUSTRALIAN MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY, CITY OF BAYSWATER, CITY OF BELMONT, CITY OF CANNING, CITY OF JOONDALUP, CITY OF MELVILLE, CITY OF NEDLANDS, CITY OF SUBIACO, CITY OF WANNEROO, FREMANTLE PORT AUTHORITY, SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA, SHIRE OF MUNDARING, SHIRE OF PEPPERMINT GROVE, SHIRE OF SERPENTINE-JARRAHDALE, SHIRE OF WANDERING, TOWN OF BASSENDEAN, TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE, TOWN OF CLAREMONT, TOWN OF COTTESLOE, TOWN OF EAST FREMANTLE, TOWN OF KWINANA, TOWN OF MOSMAN PARK, TOWN OF VICTORIA PARK, CITY OF ARMADALE, CITY OF GOSNELLS, CITY OF PERTH, CITY OF SOUTH PERTH, CITY OF STIRLING, SHIRE OF CHITTERING, SHIRE OF NORTHAM, TOWN OF VINCENT, NOONGAR LAND COUNCIL, BORAL RESOURCES (WA) LTD, ADELAIDE BRIGHTON CEMENT LIMITED, COCKBURN CEMENT LTD, DORRINGTON MARINE SERVICES/YENNETT PTY LTD, N H L PTY LTD, AUSTRALIAN RED CROSS, ERNST PETER KALTENBRUNNER, ALAN JOHN RENNER, ROMAN CATHOLIC ARCHBISHOP OF PERTH, UNITING CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA WA SYNOD, FREMANTLE SAILING CLUB INC, THE SHELL COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED, ALCOA OF AUSTRALIA LTD, BLUEGATE NOMINEES PTY LTD, EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY, LIMESTONE RESOURCES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD, TIWEST JOINT VENTURE, TRONOX WESTERN AUSTRALIA PTY LTD, WESFARMERS KLEENHEAT GAS PTY LTD, WORSLEY ALUMINA PTY LTD, YALGOO MINERALS PTY LTD, AND TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | Part of WAD 6006 of 2003 Part of WAD 149 of 1998 and WAD 137 of 1998 and WAD 138 of 1998 and WAD 139 of 1998 and WAD 140 of 1998 |

IN THE MATTER OF THE PERTH METRO PORTION OF

THE SINGLE NOONGAR CLAIM NO. 1

| BETWEEN:

AND: | ANTHONY BENNELL AND OTHERS APPLICANTS

CHRISTOPHER ROBERT BODNEY BODNEY APPLICANT

|

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA AND OTHERS RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | WILCOX J |

| DATE: | 19 SEPTEMBER 2006 |

| PLACE: | PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

WILCOX J:

1 These reasons for judgment concern six applications under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (‘the Act’) in relation to land and waters in and around the Perth metropolitan area.

2 The reasons are structured in the following way, paragraph references being stated:

I The proceedings

(i) The 1998 applications 3 - 8

(ii) The Combined Metro application 9 - 10

(iii) The hearing before Beaumont J 11 - 16

(iv) The motion to strike-out the Bodney applications 17 - 21

(v) The Single Noongar application 22 - 27

(vi) Pre-trial orders and directions 28 - 36

(vii) Pre-trial rulings 37 - 48

(viii) The hearing 49 - 56

(ix) The formal issues in the cases 57

II Elements of a native title claim

(i) The source of the elements 58

(ii) The effect of s 223(1) of the Act 59 - 60

(iii) Communal and group claims 61 - 63

(iv) The Applicants’ submissions about legal principles 64 - 73

(v) The respondents’ submissions about legal principles 74 - 82

III The factual issues in these cases 83

IV Was there a Single Noongar community in 1829?

(i) The Applicants’ claim 84

(ii) Source material

(a) Overview 85 - 89

(b) The expert witnesses 90 - 95

(c) The journals of pre-settlement explorers 96

(d) The King George’s Sound writers 97 - 99

(e) The early Perth district writers 100

(f) Late 19th century writers 101 - 103

(g) The early 20th century writers 104 - 105

(h) Some cautionary notes 106 - 112

(i) Late 20th century writers 113 - 115

(j) Marginal matters 116 - 117

(iii) Historical summary

(a) The maritime explorers 118 - 127

(b) The King George’s Sound garrison and settlement 128 - 146

(c) The early post-settlement years 147 - 182

(d) Early 20th century writers 183 - 186

(e) Dr Palmer’s comments on the historical material 187 - 188

(f) Dr Brunton’s response to Dr Palmer’s comments 189 - 190

(iv) Language

(a) Dr Thieberger’s evidence 191 - 216

(b) Aboriginal evidence about language 217 - 252

(c) Dr Palmer’s evidence 253 - 260

(d) Dr Brunton’s evidence 261 - 262

(e) Applicants’ submissions 263 - 264

(f) Submissions for respondents 265 - 272

(g) Conclusions 273 - 280

(v) Laws and customs concerning land

(a) The early writings 281 - 284

(b) Aboriginal evidence about land 285 - 286

(c) Dr Palmer’s evidence 287 - 307

(d) Dr Brunton’s evidence 308 - 324

(e) Applicants’ submissions 325 - 329

(f) Submissions for respondents 330 - 347

(g) Conclusions 348 - 351

(vi) Customs and beliefs

(a) Circumcision 352 - 354

(b) Kangaroo skinning 355 - 357

(c) Spiritual beliefs 358 - 368

(d) Marriage 369 - 376

(e) Sexual transgressions 377

(f) Payback 378

(g) Funeral rites 379 - 380

(h) Tools, weapons and food-getting 381 - 383

(vii) Social interaction

(a) The early writers 384 - 389

(b) The Aboriginal evidence 390

(viii) The expert evidence about the 1829 situation

(a) Dr Palmer 391 - 394

(b) Dr Brunton 395 – 402

(ix) Submissions about the 1829 situation

(a) The Applicants’ submissions 403 - 406

(b) Respondents’ submissions 407 - 423

(x) Conclusions about the 1829 situation 424 - 454

V Has there been a continuation of Noongar laws and customs

from 1829 until the present day?

(i) Preliminary 455 - 459

(ii) Community identification and interaction

(a) The Aboriginal evidence 460 - 595

(b) Comment on the Aboriginal evidence 596 - 601

(iii) Customs and beliefs

(a) Spiritual beliefs 602 - 606

(b) Marriage 607 - 644

(c) Death and funerals 645 - 649

(d) Hunting, fishing and other food-gathering 650 - 684

(iv) Laws and customs concerning land 685 - 700

(v) Submissions about the continuity of acknowledgement

and observance of 1829 laws and customs

(a) The Applicants’ submissions 701 - 706

(b) The State’s submissions 707 - 731

(c) The Commonwealth’s submissions 732 - 744

(d) WAFIC’s position 745

(e) The local government authorities’ submissions 746 – 749

(vi) Conclusions about the continuity of acknowledgement

and observance of 1829 laws and customs

(a) Some peripheral matters 750 – 761

(b) Continuing observance of rules relating to land 762 – 791

(c) Connection with the Perth Metropolitan Area 792 – 799

VI What Noongar native title rights exist today?

(a) Preliminary 800

(b) The geographic limits of any surviving native title

rights and interests 801 – 805

(c) What are the surviving rights and interests?

(i) The Applicants’ claims 806 – 812

(ii) Section 223(1)(c) of the Act 813 – 814

(iii) The claim to a right of occupation, use and

enjoyment of the lands and waters 815 – 841

VII The Bodney applications

(i) Nature of the applications 842 – 843

(ii) Mr Bodney’s evidence 844 – 866

(iii) Other evidence 867 – 868

(iv) Submissions 869– 871

(v) Conclusions 872 – 876

VIII Disposition of proceedings 877 – 883

IX Postcript: the State’s notice of motion of 25 August 2006

(i) Content of the motion 884 -898

(ii) Reaction to the motion 891 - 898

(iii) The State’s submissions in support of the motion 899

(iv) The evidentiary background 916 - 922

(v) The Applicants’ submissions on the strike-out motion 923

(vi) Issues raised by the State’s motion of 25 August 2006 924

(vii) Validity of the order for the separate question 925 - 930

(viii) Is it open to the State to complain about the order for

a separate question? 931 - 934

(ix) Has the separate question order excluded relevant evidence? 935 - 939

(x) Conduct of the strike-out motion 940 - 944

(xi) Disposal of the motion 945 – 951

(xii) Concluding comment 952

I The proceedings

(i) The 1998 applications

3 Between November 1994 and September 1998, 13 applications seeking native title determinations, in relation to land and waters in and around the Perth metropolitan area, were lodged with the Registrar of Native Title pursuant to the Act, as it then stood (‘the old Act’). None of these claims was resolved by mediation. All the claims were referred to this Court, either under s 74 of the old Act, before 30 September 1998, or pursuant to the transitional provisions of the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) (‘the Amending Act’) that took effect on that day. Where it is necessary to distinguish between the old Act and the Act, as so amended, I will refer to the latter as ‘the Amended Act’.

4 Application WAG 6009 of 1996 related to Perth airport. In Bodney v Westralia Airports Corporation Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1609; 109 FCR 178, Lehane J held that any native title over this land had been extinguished by its acquisition in fee simple by the Commonwealth of Australia (‘the Commonwealth’) on various dates before 1986. On 13 November 2000, his Honour made a formal order in which he determined that native title did not exist over the airport land. I need not further regard this application.

5 Five of the remaining 12 applications were made by Christopher Robert (‘Corrie’) Bodney. Four of those claims related to small areas of land in the Perth region, being land at Hartfield Park, Wanneroo Road, Burswood Island and Swanbourne respectively. The fifth claim (‘the main claim’) involved a much larger area of land, with its adjoining sea out to 12 nautical miles from the coast. After their transfer to this Court, those applications were numbered, respectively, WAG 137 of 1998, WAG 138 of 1998, WAG 139 of 1998, WAG 140 of 1998 and WAG 149 of 1998. I will refer to these five applications as ‘the Bodney applications’.

6 A sixth application (WAG 141 of 1998) (‘the Bropho application’) was lodged by Robert Charles Bropho on his own behalf.

7 The remaining six applications were lodged either by Mr Bropho, on behalf of the ‘Swan Valley Nyungah Community’, or by people associated with Mr Bropho. Four of these applications related only to small areas of land. Two involved substantial areas of land and waters, including sea to the 12 nautical mile limit. The six applications were numbered WAG 142 of 1998, WAG 143 of 1998, WAG 6128 of 1998, WAG 6159 of 1998, WAG 6239 of 1998 and WAG 6283 of 1998. With some looseness of language, these six applications may be called ‘the Swan Valley Nyungah applications’. There was considerable overlap between the Bodney applications on the one hand and the other seven applications on the other.

8 All of these matters have now been given the prefix WAD due to requirements of the Court’s electronic data management system.

(ii) The Combined Metro application

9 On 12 April 1999, the Western Australian District Registrar of the Court made an order for combination of all the Swan Valley Nyungah applications. He further ordered that application WAG 142 of 1998 be the lead application and the parties to the combined application be all the parties to any of the Swan Valley Nyungah applications. The combined application became generally known as ‘the Combined Metro application’.

10 On 7 January 2000, French J made orders for notification, under s 66 of the Act, of the land and waters covered by the Combined Metro application that had not been previously notified: see Bropho v State of Western Australia [2000] FCA 1.

(iii) The hearing before Beaumont J

11 Numerous orders were later made in preparation for hearing the Combined Metro application, including for joinder of additional parties. On 26 July 2000, Lehane J directed there be a joint trial, in about September 2001, of the Bodney applications, the Bropho application and the Combined Metro application.

12 The joint trial commenced before Beaumont J on 18 September 2001. Between that date and 3 April 2003, evidence was taken spasmodically, over a total of 19 days, at locations in and around the Perth metropolitan area. The hearing was not satisfactory. It suffered from inadequate preparation, and representation, on behalf of the applicants and was bedevilled by lengthy arguments about procedural matters, including access to information.

13 Mr Bodney and Mr Bropho appeared in person throughout the hearing. The Combined Metro applicants were intermittently represented by a succession of lawyers apparently acting on a pro bono basis. They did the best they could, without having the benefit of expert advice or evidence or the opportunity to prepare a coherent case. Some of the respondents were legally represented throughout the hearing.

14 When the trial was adjourned on 3 April 2003, the evidence was still incomplete. On the following day, 4 April 2003, Beaumont J made an order, pursuant to Order 29 rule 2 of the Federal Court Rules, that the following question be decided separately from and before any other questions in the Combined Metro application:

‘1. what are the communal, group or individual rights and interests, if any, of Aboriginal peoples in relation to land or water in the claim area, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters;

2. which Aboriginal people, if any, hold those rights and interests.’

15 Shortly after this order was made, Beaumont J found it necessary, on medical grounds, to retire from the matters. At a directions hearing before French J, the parties agreed the hearing would be completed by a different judge, but on the basis that the evidence taken by Beaumont J would not be repeated. On 13 June 2003, French J made the following formal orders:

‘1. There be a new trial of the native title application in WAG 142 of 1998 to be tried together with new trials of the applications WAG 137 – 141 and 149 of 1998 (limited in the latter case to the area of its overlap with the other applications).

2. The transcript of evidence and exhibits etc. in the proceedings before the Court already heard in the above matters be received into evidence at the new trials subject to any objections as to the admissibility of particular evidence which had been made and not ruled upon in the previous proceedings and subject to such restrictions as have been ordered until such restrictions are lifted or varied by the trial judge.

…

4. The transcript of evidence already taken may be supplemented by such site visits and such further oral evidence as the trial judge directs.’

16 Soon after those orders, I was asked to take over the matters. At a directions hearing held by me on 19 August 2003, I indicated I understood the agreement embodied in French J’s orders to require me to read and apply the evidence already given (to the extent that any party relied upon it), along with such further evidence as the parties might adduce. No party disagreed with that understanding.

(iv) The motion to strike-out the Bodney applications

17 At about the time the matters were assigned to me, the Combined Metro applicants filed a notice of motion for orders, pursuant to s 84C(1) of the Act, striking out each of the Bodney applications. It was said these applications did not comply with the requirements of s 61 of the Act.

18 Section 84C(2) of the Act requires the Court to consider a strike-out application under s 84C(1) ‘before any further proceedings take place in relation to the main application’. Mr Bodney did not respond to the strike-out application by seeking to amend any of his applications. Accordingly, on 19 August 2003, I heard argument on the strike-out application.

19 On 25 August 2003, I made orders striking out all the Bodney applications: see Bodney v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 890. It was my opinion that none of them satisfied the requirements of the relevant version of s 61 of the Act. All of the applications had been made under the old Act, but two of them (WAG 137 of 1998 and WAG 149 of 1998) had been amended since the commencement of the Amending Act. I followed two previous first instance decisions, in holding that s 61 of the Amended Act applied to the amended applications.

20 I held the three applications needing to be evaluated under the old s 61 were defective because of Mr Bodney’s failure to ‘describe or otherwise identify’ the persons on whose behalf the application was made. The two applications that had been amended after the commencement of the Amending Act provided a fuller description of the claimant group but it appeared clear, from evidence given before Beaumont J, that neither of them was authorised by the members of the described group in accordance with s 251B of the Act, as required by the new s 61.

21 On 24 August 2004, a Full Court allowed an appeal against my decision and set aside the strike-out orders: see Bodney v Bropho [2004] FCAFC 226; 140 FCR 77. The Full Court was divided as to whether the new form of s 61 applied to the two amended applications. However, all members of the Court thought Mr Bodney should have a further opportunity to amend his applications in such a manner as to avoid the difficulties raised against them.

(v) The Single Noongar application

22 On 10 September 2003, a new proceeding (WAG 6006 of 2003) was instituted. This proceeding has been referred to as the ‘Single Noongar application’ (or Single Noongar [No 1]), on account of the fact that it was made by 80 named applicants ‘on behalf of all Noongar people’. The filed Native Title Determination Application stated the named applicants ‘are members of the native title claim group and are authorised to make the application, and deal with matters [which] arise in relation to it, by all the other persons in the native title claim group’. The application described the Noongar people in this way:

‘ The descendants of the Noongar apical ancestors listed in Attachment A1;

The members of the Noongar families whose surnames are listed in Attachment A2;

The descendants, of the Noongar ancestors of families whose surnames are listed in Attachment A2;

The members of the Noongar families whose surnames are listed in Attachment A3;

The descendants, of the Noongar ancestors of families whose surnames are listed in Attachment A3; and

All other Noongar people identifying and accepted in accordance with Noongar customs and traditions as understood by Noongar people and handed down by Noongar Elders.

Identification of a Noongar person is through biological descent from a Noongar person but can include people incorporated into the Noongar community through adoption, in accordance with Noongar custom and tradition.

Identification of a Noongar family is through biological descent from a Noongar person but can include people incorporated into the Noongar community through adoption, marriage or defacto marriage and in accordance with Noongar custom and tradition.’

Attachment A1 identified 99 apical ancestors. Attachments A2 and A3 set out some 400 family names.

23 Attachment B to the application contained a detailed description of the external boundary of the claimed area (‘the claim area’). The description was illustrated by a map (Attachment C) which showed that the external boundary of the claim area extends from a point on the western coast of Australia in the Shire of Coorow, just north of Jurien, roughly easterly to a point approximately north of Moora and then roughly south-easterly to intersect the southern coast of Australia at a point slightly west of Esperance. The claim area contained some off-shore islands, including Rottnest and Carnac Islands, and the sea abutting the entire coastal area, and the claimed islands, to the three nautical mile limit. The claim area excluded a relatively small strip of coastal land in the Busselton-Margaret River district. This land is the subject of a separate claim, generally called ‘Single Noongar No 2’. The Single Noongar [No 1] claim area excluded all land and waters that are, or were, subject to a past act attributable to the Commonwealth or the State of Western Australia (‘the State’), including the grant of freehold title.

24 It will be appreciated that the claim area includes the Perth metropolitan area.

25 Schedule E of the application set out the native title rights and interests claimed by the applicants:

‘The applicants claim the right to occupation, use and enjoyment of the lands and waters in accordance with and subject to their traditional laws and customs (or current laws and customs as they have adapted and changed from those traditional laws and customs).

The applicants acknowledge that these rights may co-exist with other statutory or common law rights in relation to some lands and waters, subject to the force and operation of laws of the Commonwealth and the State.

The right to occupation, use and enjoyment of the lands and waters includes the right to:

(a) live on and access the area;

(b) use and conserve the natural resources of the area for the benefit of the native title holders;

(c) maintain, use, manage and enjoy the area for the benefit of the native title holders, that is to:

i) maintain and protect sites of significance to the native title holders and other Aboriginal people within the meaning of that term in the Native Title Act 1993;

ii) inherit, dispose of or give native title rights and interests to others provided that such persons are Aboriginal people within the meaning of that term in the Native Title Act 1993;

iii) right to determine and regulate membership of, and recruitment to, the native title holding group, provided that such persons must be Aboriginal people within the meaning of that term in the Native Title Act 1993;

iv) regulate among and resolve disputes between, the native title holders in relation to the rights of possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the area;

v) conduct social, religious, cultural and economic activities on the area;

vi) exercise and carry out economic life on the area, including harvesting, fishing, cultivating, management and exchange of economic resources;

(d) conserve, use and enjoy the natural resources of the area, for social, cultural, economic, religious, spiritual, customary and traditional purposes; and make decisions about and to control the access to, and the use and enjoyment of, the area and its natural resources by the native title holders;

(e) the right to control access and use between the native title holders and any other Aboriginal people who seek access to, or use of, the claim area in accordance with the traditional law and custom;

(f) the right to teach and pass on knowledge of the applicant group’s traditional laws and customs pertaining to the area and knowledge of places in the area;

(g) the right to learn about and acquire knowledge concerning, the applicant group’s traditional laws and customs pertaining to the area and knowledge of places in the area.

In relation to:

(a) any areas where there has been no previous extinguishment of native title;

(b) any area of natural water resources that is found not to be tidal;

(c) any areas affected by category C and D past and intermediate period acts;

(d) s47 Pastoral leases held by native title claimants;

(e) s47A Reserves act covered by claimant applications; and/or

(f) s47B Vacant Crown Land Covered by claimant applications,

the applicant claims exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of those areas.’

26 The application identified the relevant representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander body as South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (‘SWALSC’). It also contained considerable additional information, which it is not necessary to set out.

27 On 2 October 2003, French J made directions for mediation and negotiation of the Single Noongar application and a number of smaller claims (outside the Perth area) that overlapped that application. I understand there were discussions between the parties but no substantive agreement was reached.

(vi) Pre-trial orders and directions

28 On 6 October 2003, Christine Cooper, a solicitor employed by SWALSC, filed a notice of motion on behalf of the Single Noongar applicants seeking an order for the combination of the Single Noongar application with the Combined Metro application (WAG 142 of 1998).

29 I heard submissions about the motion on 8 October 2003. It is convenient to explain what happened by reference to paras 6-9 of the Reasons for Judgment delivered by me on the following day:

‘The single Noongar claim covers a significant portion of Western Australia. Its northern boundary is a line running east from a position on the coast north of Jurien. The claimed area then runs south-east to a point on the Great Australian Bight near Esperance. Subject to internal exceptions, the claimed area takes in the whole of the south-west of the State and much, if not all, of the Western Australian wheatbelt. Importantly for present purposes, it includes the whole of the area covered by the Perth Metro claims, except that the single Noongar claim extends only three nautical miles off-shore, whereas WAG 142 of 1998 claims waters to the twelve nautical mile limit.

At a directions hearing on 1 October 2003, I was informed of a proposal to amend WAG 141 of 1998 and WAG 142 of 1998 in such a way as to combine them with the single Noongar claim. I directed that any application to that effect be filed and served not later than 6 October 2003 and be made returnable before me on 8 October 2003. Such an application was made. However, it sought to amend only WAG 142 of 1998, a decision having been taken by Mr Bropho to seek leave to discontinue matter WAG 141 of 1998.

When the motions came before me yesterday, it immediately became apparent that there was no opposition to the application for leave to discontinue WAG 141 of 1998, except by Mr Bodney. However, Mr Bodney was not able to show the discontinuance would prejudice him in any way. I granted leave. This left only WAG 142 of 1988, of the seven applications transferred to the Court on 30 September 1998. That matter was subject to a strike-out application by Mr Bodney which I then heard and dismissed.

I turn to the applicants’ motion to amend WAG 142 of 1998. A companion motion was filed in the single Noongar claim, by solicitors acting for the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (‘SWALSC’). At the hearing of the motions, it became apparent there was no real opposition to the proposed amendments. The real issue was what should happen next.’

30 Counsel for the Combined Metro applicants and counsel for SWALSC had submitted it was unnecessary for me to do more than to make a combination order, leaving further pre-trial steps to be governed by the general Single Noongar directions that had already been made by French J. However, counsel for some of the respondents, including the State and the Commonwealth, had disputed that view. At para 14 of my Reasons, I summarised their position in this way:

‘These counsel express concern at the prospect of further prolonged delay in the Court determining whether native title exists over land and waters in and around Perth. They point out that the first application in respect of the Perth metropolitan area, the claim that became matter WAG 141 of 1998, was lodged as long ago as November 1994. They rightly say that prosecution of the claims has been attended with considerable delay and they contend that there is a substantial public interest in their early resolution. The respondents say that, if WAG 142 of 1998 becomes part of the vast single Noongar claim, without being subject to any special measures to ensure its early determination, then resolution may be postponed for years.’

31 I went on:

‘There is considerable force in the matters put by the respondents. It had been my intention to take evidence in relation to the Perth Metro claims during the next two weeks; that is, the weeks commencing 13 and 20 October 2003. The evidence would not necessarily have concluded within that period; but it would have been substantially complete. It should have then been possible to complete the hearing with little further delay. The filing of the single Noongar claim has made it impractical to take that course. Section 67(1) of the Act requires that, if two or more proceedings relate to the same area (in whole or in part), the Court must ensure they are dealt with in one proceeding. Given that the single Noongar claim has yet to be notified under s 66 of the Act, it cannot properly proceed to hearing during the next two weeks.

Although none of the respondents mentioned any particular problem that might be caused by delay in finalising the Perth Metro claims, they understandably feel frustrated and concerned about the delay occasioned by cancelling the projected hearing. I think they are right to suggest it is important that every effort be made to minimise further delay. However, this must be done in such a way as to be consistent with the scheme and policy of the Act, and to be fair to the single Noongar claimants.’

32 Counsel for the State suggested it would be practicable, and desirable, to hear that aspect of the Single Noongar claim which related to the land and waters within the Combined Metro claim in advance of any hearing concerning the balance of the Single Noongar area. I thought there was merit in that suggestion and, after discussing various practical issues, I expressed the hope that it would be possible to hear the Perth section of the single Noongar claim in about October 2004. On 9 October 2003, I made orders in WAG 142 of 1998 that included the following:

‘1. The applicants be granted leave to amend Native Title Determination Application WAG 142 of 1998 pursuant to s 64 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), so that it is combined with and included in Native Title Determination Application WAG 6006 of 2003.

2. The amended application be in the form of WAG 6006 of 2003 as filed on 10 September 2003 in accordance with the Minute of Proposed Amended Native Title Application attached to the affidavit of Albert Corunna dated 6 October 2003.

3. Both of these applications be now conducted as one application.

4. Application WAG 6006 of 2003 be the lead application.

...

6. Subject to any contrary order by a Judge, that part of the combined application as relates to the land and waters covered by application 142 of 1998 (“the Perth claim”) shall be heard in a separate proceeding to commence during the first week of October 2004 …

7. The evidence already given in respect of matters WAG 137 of 1998, WAG 138 of 1998, WAG 139 of 1998, WAG 140 of 1998, WAG 141 of 1998, WAG 142 of 1998 and WAG 149 of 1998 is to be evidence in the hearing to commence in October 2004 subject to relevance and all just objections, including any new objections taken by any person who was not a party to any of those seven matters.

8. Subject to the above, the directions made by French J on 2 October 2003 in relation to matter WAG 6192 of 1998 are to apply to the Perth section claim as if they were set out seriatim herein.

9. All parties have liberty to apply to me, by arrangement with my associate, in relation to any matter connected with the separate hearing of the Perth section claim.’

33 In matter WAG 6006 of 2003, I made orders corresponding with the first four of the above orders.

34 On 9 October 2003, the Bropho application (WAG 141 of 1998) was discontinued. The only surviving applications affecting any part of the Perth metropolitan area were then the Single Noongar application (insofar as it did affect that area) and the five Bodney applications (after they were reinstated by the Full Court on 24 August 2004).

35 On 28 November 2003, Ms Cooper filed a further notice of motion seeking an order to combine the Single Noongar application with ten overlapping claims. On 15 June 2004, French J dismissed that motion. The ten claims remain in existence but none of them relates to the area with which these reasons are directly concerned.

36 It gradually became apparent that it would not be practicable to commence the hearing of the Perth claims in October 2004. SWALSC suffered delay in procuring a promise of the funding that was necessary for it to engage experts. Once experts were retained, they endeavoured to prepare their reports as quickly as possible. However, it became obvious that satisfactory reports could not be finalised in time for an October 2004 hearing. Accordingly, on 22 July 2004, I abandoned the idea of an October 2004 hearing and made new directions designed to enable a hearing in 2005.

(vii) Pre-trial rulings

37 Between 22 July 2004 and the commencement of the trial, on 11 October 2005, I made rulings regarding several interlocutory applications. I need not deal with them all. However, I mention five matters.

38 First, despite the reference, in order 6 made on 9 October 2003, to a ‘separate proceeding’, no formal order was made splitting WAG 6006 of 2003. Nor was a separate file number assigned to the ‘separate proceeding’. In retrospect, it would have been desirable for me to take, or direct, those steps at that time. Instead, after hearing submissions from the parties, on 1 April 2005, I directed the trial of a separate question. The form of this question, as later amended, is set out at para 47 below.

39 Second, it will be recalled that the Full Court adverted to the possibility that Mr Bodney might amend his applications in order to overcome the perceived authorisation problems. Although Mr Bodney had previously not shown interest in taking this course, I drew his attention to the Full Court’s position. On 1 April 2005, I made the following order:

‘Leave be granted to the applicant, in each of matters WAD 137 of 1998, WAD 138 of 1998, WAD 139 of 1998, WAD 140 of 1998, and WAD 149 of 1998, to file an amended application, if the applicant so wishes. Any such amended application is to be filed and served not later than 31 May 2005. Each of these applications, and the strike out motions in relation to them, shall be heard in conjunction with the Perth Metro part of the Single Noongar claim (WAD 6006 of 2003).’

40 I subsequently extended the date for filing any amended application to 1 July 2005. However, Mr Bodney did not amend any of his applications. Nor did he seek any further extension of time. In the hearing that was subsequently conducted by me, he cross-examined most witnesses; but he did not adduce evidence additional to what he had given before Beaumont J.

41 In their closing written submissions, counsel for the Single Noongar applicants expressed in the following way their clients’ attitude to the Bodney applications:

‘The Single Noongar claimants acknowledge that Mr Bodney and those represented by him are members of the Noongar people as described in the Single Noongar claim. The Single Noongar claimants do not, however, acknowledge, that Mr Bodney and some members of his family have exclusive connection with or rights and interests in relation to, the land and waters claimed in the various Bodney claims.’

42 Third, on 15 February 2005, I ordered that: ‘[i]f any party wishes to challenge the authority of the Applicants to make claim WAD 6006/03, that party is to file a strikeout motion with supporting affidavit evidence by 31 March 2005’. The only party who chose to take that course was the Noongar Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (‘NLC’), the former representative body for the area. On 13 May 2005, NLC filed a notice of motion seeking an order striking out the Single Noongar application. The motion was supported by an affidavit of Frank Peter David, who described himself as ‘the Registered Public Officer and acting chief executive officer’ of the NLC. The affidavit made many assertions of fact, and some allegations of misconduct, but it did not challenge the material about authorisation that was set out in the Single Noongar application. Nor did it raise any other ground for striking out that application. However, having in mind the requirement of s 84C(1) of the Act, I listed the motion for hearing on 5 August 2005. On that day, Mr David appeared on behalf of NLC, accompanied by Mr R Yarran. He developed the matters set out in his affidavit but put no argument to me relevant to a strike-out order. Accordingly, I dismissed the strike-out motion.

43 Fourth, on 19 August 2005, a notice of motion was filed by Blake Dawson Waldron, solicitors, seeking an order for the joinder as respondents of some 40 persons (individuals and companies) who were said to hold interests in pastoral leases over land that was situate in the area covered by the Single Noongar claim, but outside the area which was the subject of the ‘separate proceeding’ and separate question.

44 I considered this motion at a hearing on 23 August 2005. The argument put by the applicants for joinder was that, although they did not have an interest in any land within the area that was subject to the ‘separate proceeding’ and separate question, the determination of the separate question was likely to have a significant effect on the fate of that part of the Single Noongar claim that concerned land and waters outside that area, including land in which they did have interests.

45 I accepted this possibility: see s 86 of the Act, noting particularly para (c). However, it seemed to me this did not mean the applicants for joinder fell within the class of persons referred to in s 84(3) of the Act in relation to the land and waters which were the subject of the ‘separate proceeding’ and separate question. Although s 84(3)(a)(iii) refers to a person whose ‘interests may be affected by a determination in the proceedings’, it is necessary there be a direct interest, not an interest that is indirect or remote: see Chapman v Minister for Land and Water Conservation (NSW) [2000] FCA 1114 at [10]. The word ‘interests’ ought not to be read narrowly. However, it seemed to me insufficient that a person be able to show that the decision in respect of the separate question might have a flow-on effect to the wider Single Noongar claim. Accordingly, I did not accede to the application for these people actively to participate in the hearing of the separate question. I directed that the notice of motion, insofar as it concerns WAD 6006 of 2003 generally, be considered by French J (who retained general responsibility for the Single Noongar application) at a date to be advised. I also suggested that a representative of the pastoral lessees might wish to attend the forthcoming trial as an observer. A solicitor representing those persons did attend for much of the time.

46 Fifth, during the trial, the solicitor for the State applied for an order repairing my omission formally to establish the proposed separate proceeding in respect of the area described in the separate question. I indicated I would accede to that application and invited the parties to consult regarding the form of the order. On 21 December 2005, I made the following substantive orders:

‘1. Pursuant to Order 78 rule 6(5) of the Federal Court Rules:

(a) application WAD 6006 of 2003 be divided into two parts, being Part A (as delineated in the attached Map 1) and Part B being the balance; and

(b) Part A of the application be considered separately and prior to Part B.

2. Pursuant to section 67 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and Order 29 rule 5 of the Federal Court Rules, Part A of application WAD 6006 of 2003, and application WAD 149 of 1998 to the extent it overlaps with the land and waters hatched on the attached Map 2, and all of native title determination applications WAD 137 of 1998, WAD 138 of 1998, WAD 139 of 1998, and WAD 140 of 1998 be heard together in a separate proceeding (‘the separate proceeding’).

…

4. Save for the orders made by French J on 22 September 2005 in application WAD 6006 of 2003, all orders made, all documents filed and all evidence received in applications WAD 6006 of 2003 and WAD 149 of 1998, WAD 137 of 1998, WAD 138 of 1998, WAD 139 of 1998, WAD 140 of 1998 shall be taken to also be orders made and documents filed and evidence in the separate proceeding.’

47 By order 5, I further amended the form of the separate question so as to make it read:

‘But for any question of extinguishment of native title by inconsistent legislative or executive acts carried out pursuant to the authority of the legislature under Divisions 2, 2A, 2B or Part 2 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or under the Titles (Validation) and Native Title (Effect of Past Acts) Act 1995 (WA):

(i) does native title exist in relation to land and waters in the area of the separate proceeding:

(a) that part of the area the subject of application WAD 6006 of 2003 which was the subject of application WAD142 of 1998 immediately prior to that application being combined with and included in application WAD 6006 of 2003; and

(b) that part of the area the subject of WAD 149 of 1998 which lies seaward of the area the subject of WAD 6006 of 2003 and does not overlap the area claimed in WAD 192 of 1998 (YUED).

(ii) if the answer to (i) above is in the affirmative, who are the persons or each group of persons holding the common or group rights comprising the native title; and

(iii) what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the area?

The land and waters referred to in this question included the whole of the land and waters claimed by Mr Bodney. Although the land referred to in the question includes substantial areas of non-urban land, it is convenient to use the term ‘Perth Metropolitan Area’ to refer to all the relevant land and waters.

48 The effect of those orders was to make Part A of the application the ‘separate proceeding’ envisaged on 9 October 2003. I append to these reasons copies of Maps 1 and 2, referred to in these orders. Map 1 shows the relationship between the Perth Metropolitan Area and the remainder of the claim area. Map 2 is a larger scaled map of the Perth Metropolitan Area.

(viii) The hearing

49 The hearing of the separate proceeding commenced in the Commonwealth Law Courts, Perth on Tuesday, 11 October 2005. The Single Noongar applicants (hereafter ‘the Applicants’) were represented throughout by Mr V B Hughston SC and Ms T L Jowett, the State by Mr S Wright and Mr G Ranson, the Commonwealth by Ms R Webb QC and the Western Australian Fishing Industry Council (‘WAFIC’) by Mr M McKenna. Mr P Wittkuhn appeared for various local government authorities but participated in the hearing only intermittently. Mr Bodney appeared on his own behalf, as applicant in the Bodney applications and a respondent to the Single Noongar application. Mr David sought and obtained leave to appear for the NLC, a respondent to the Single Noongar application, for the limited purpose of cross-examining expert witnesses and making submissions at the end of the case. Mr Kevin Miller, a respondent, appeared for himself. Although there were also respondents who did not participate in the hearing, it is convenient to use the expression ‘the parties’ to refer only to the parties identified in this paragraph.

50 After opening addresses were made on behalf of all the parties, Mr Hughston tendered documentary material, including expert reports, and called Dr John Host, an historian. Over a period of three days, Dr Host and a linguist, Dr Nicholas Thieberger, were cross-examined on their written reports.

51 On Friday, 14 October, the Court commenced a total of 11 days ‘on-country’ hearings. The Court sat at Jurien Bay, Albany, Toweringup Lake near Katanning, Dunsborough near Busselton, Kokerbin Rock and Djuring in the Kellerberrin district and, in Perth, at Swan Valley and Kings Park. While ‘on-country’, the Court heard the evidence of 30 Aboriginal persons and inspected a number of sites. At Kings Park, counsel for the Applicants also called two anthropologists who had assisted Dr Kingsley Palmer, the applicants’ consultant anthropologist, by interviewing people within the claim group.

52 The procedure adopted by counsel in relation to the Aboriginal witnesses worked well. Prior to the hearing, written statements of these witnesses had been filed and served. When each witness was called, he or she confirmed the statement (often after making minor amendments) and then Mr Hughston or Ms Jowett asked a brief series of questions, to bring out the main points of the witness’ statement, before the witness was cross-examined. The ‘on-country’ hearings ran very smoothly, thanks to excellent organisation by the Court’s remote hearings staff and the constant co-operation of the parties and their representatives.

53 After completion of most of the Aboriginal witnesses’ evidence, Dr Palmer gave evidence, over three days, in the Commonwealth Law Courts Building in Perth. At the end of that time, on 2 November 2005, the hearing was adjourned until 5 December 2005. On that day, the third anthropologist who assisted Dr Palmer was cross-examined. Thereafter, over that day and the succeeding two days, two expert witnesses called by the State were cross-examined. They were Dr Ron Brunton, an anthropologist, and Ms Debra Fletcher, an historian.

54 At the conclusion of this evidence, on 7 December, the hearing was adjourned to enable counsel, and the unrepresented parties, to prepare and file written submissions.

55 The last written submissions were filed on 18 May 2006. On 23 June 2006, the Court held a video-link hearing between Sydney and Perth for the purpose of oral discussion of some of the matters raised in these submissions. At the conclusion of that hearing, I reserved judgment in the case.

56 I have been informed that, sadly, two of the Aboriginal people who gave evidence before me have since passed away. Accordingly, it would be inappropriate for me to use their names. In these reasons, I will refer to them as ‘Mr WW’ and ‘Mr MW’ respectively. Both these people were named applicants in matter WAD 6006 of 2003. I have directed their names be removed from the Court record.

(ix) The formal issues in the cases

57 Having regard to the above events, the issues now before the Court are as follows:

(a) In relation to each of Mr Bodney’s five applications: first, whether the application is properly authorised and, second, whether it succeeds on the merits. As will appear, I have reached a conclusion adverse to Mr Bodney on the merits of each application. I will therefore not need to deal with authorisation.

(b) In relation to Part A of the Single Noongar application, what answers should be given to each of the issues raised by the separate question set out at para 47 above. There being no extant strike out motion in respect of this claim, there is no issue about authorisation.

II Elements of a native title claim

(i) The source of the elements