Federal Court of Australia

Mussalli v Commissioner of Taxation [2021] FCAFC 71

Mussalli v Commissioner of Taxation [2020] FCA 544 | |

File number: | NSD 555 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | MCKERRACHER, THAWLEY AND STEWART JJ |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | TAXATION – income tax – deductibility – payments made upon entering into lease and license agreements of franchise restaurants – payments described as prepayments of rent – whether payments were capital in nature or on revenue account – characterisation of advantage sought – where the quantum of the prepayment was calculated without reference to the terms of the lease and license agreements |

Legislation: | Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) ss 95, 97, 82KZMD Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) ss 8-1, 8-1(2), 8-1(2)(a) Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) ss 14ZZ |

Cases cited: | Anglo-Persian Oil Co Ltd v Dale (1932) 1 KB 124; [1931] All ER Rep 725 Associated Newspapers Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1938) 61 CLR 337 AusNet Transmission Group Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2015) 255 CLR 439; [2015] HCA 25 Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1953) 89 CLR 428; [1953] HCA 68 Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. P.G. Lake, Inc. (1958) 356 US 260 Commissioner of Taxation v Creer (1986) 11 FCR 52; [1986] FCA 166 Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Ilbery (1981) 12 ATR 563; [1981] FCA 188 Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Lau (1984) 6 FCR 202 Commissioner of Taxation v Midland Railway Company of Western Australia Ltd (1952) 85 CLR 306 Commissioner of Taxation v Montgomery (1999) 198 CLR 639 Commissioner of Taxation v Myer Emporium Ltd (1987) 163 CLR 199; [1987] HCA 18 Commissioner of Taxation v Northumberland Developments (1995) 59 FCR 103 Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v South Australian Battery Makers Pty Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 645; [1978] HCA 32 Commissioner of Taxation v Star City Pty Limited (2009) 175 FCR 39; [2009] FCAFC 19 Commissioner of Taxes (Vic) v Phillips (1936) 55 CLR 144 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Ashwick (Qld) No 127 Pty Ltd (2011) 192 FCR 325; [2011] FCAFC 49 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Healius Ltd [2020] FCAFC 173 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Sharpcan Pty Ltd (2019) 373 ALR 414; [2019] HCA 36 Fletcher v Commissioner of Taxation (1991) 173 CLR 1 Glenboig Union Fireclay Co Ltd v Inland Revenue Commissioners (1921) 12 TC 427 GP International Pipecoaters Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1990) 170 CLR 124; [1990] HCA 25 Hancock (Surveyor of Taxes) v General Reversionary and Investment Company Limited [1919] 1 KB 25 IRC v Longmans Green & Co Ltd (1932) 17 TC 272 Mount Isa Mines Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1992) 176 CLR 141; [1992] HCA 62 Magna Alloys & Research Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1980) 11 ATR 276 National Australia Bank Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1997) 80 FCR 352 Spassked Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2003) 136 FCR 441 SPI PowerNet Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2013) 96 ATR 771; [2013] FCA 924 Spotlight Stores Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (2004) 55 ATR 745; [2004] FCA 650 Texas Co (A/asia) Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1940) 63 CLR 382; [1940] HCA 9 Tucker v Granada Motorway Services Ltd [1979] 2 All ER 801 Tyco Australia Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2007) 67 ATR 63; [2007] FCA 1055 Visy Industries USA Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2011) 85 ATR 232; [2011] FCA 1065 W Nevill & Co Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1937) 56 CLR 290; [1937] HCA 9 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Taxation |

Number of paragraphs: | 113 |

17 November 2020 | |

Solicitor for the Appellants: | Halperin & Co Pty Ltd |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr SJ Sharpley QC with Ms ML Baker |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Minter Ellison Lawyers |

ORDERS

First Appellant RONALD MUSSALLI Second Appellant SARONCORP PTY LTD (and others named in the Schedule) Third Appellant | ||

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellants pay the costs of the respondent to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCKERRACHER AND STEWART JJ:

1 This appeal raises the question of whether payments made in conjunction with business acquisitions, notionally by way of “prepayment of rent”, were in fact correctly so described. Secondly, on a proper understanding of the nature of the payments, were they on revenue or capital account? The primary judge held that the payments were on capital account and therefore not deductible. For the reasons that follow, that conclusion was correct.

THE PRIMARY JUDGMENT

2 The primary judge dealt with five appeals against appealable objection decisions under s 14ZZ of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth). Deductions were claimed for payments identified as “prepayment of rent” in accordance with s 82KZMD of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (the ITAA 1936). Following an audit, the Commissioner of Taxation denied all of the deductions that had been claimed. The Commissioner then issued amended notices of assessment relating to the income years ending 30 June 2012 to 30 June 2015. The appellants lodged objections against each of their respective amended assessments. The Commissioner disallowed the objections in full. The appellants then appealed the Commissioner’s objection decisions.

3 Her Honour identified the issue as being whether the payments identified as “prepaid rent” were in fact outgoings of capital or of a capital nature which are not deductible under s 8-1(2) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (the ITAA 1997).

4 The key facts were not in dispute. They can be briefly stated.

5 The second appellant, Mr Ronald Mussalli, was the controlling mind, through two corporate trustees, of the Mussalli Family Trust (MFT) and the Mussalli Investment Trust (MIT). The focus of this appeal is on the operation by MFT of a series of McDonald’s Family Restaurants as franchisee from McDonald’s Australia Limited (MAL). All of the appellants were, at the relevant times, within a class of beneficiaries of MIT which received distributions from MFT.

6 Initially, MAL offered Mr Mussalli a lease and licence to operate a McDonald’s Family Restaurant on four sites, Erina, Erina Fair II, Gosford West and Wyoming in New South Wales (the Group One restaurants). The offers included the terms of a Full Lease and Licence (or FLL) which varied depending on whether MAL owned the premises (in which case the term was 20 years) or leased the premises (in which case the term was one day less than the head lease). MFT accepted the offers. The letters of offer foreshadowed a number of required payments including, under the FLL, a base rent amount payable monthly plus GST and a percentage rent amount calculated by reference to monthly gross sales plus GST. Each of the letters of offer also included a provision to the effect set out below in respect of the Erina restaurant (with differences for each site in the percentage specified and the prepayment amount):

This agreement includes an option for you to reduce your Percentage Rent, as referred to above, to 8.25% of monthly gross sales (as defined) plus GST minus the amount paid as base rent plus GST, subject to a prepayment of rent of $660,000 plus GST on the day of handover.

7 If the option was exercised, a further payment plus GST was to be made on the day of “handover”, being the day on which the new franchisee began to operate the restaurant.

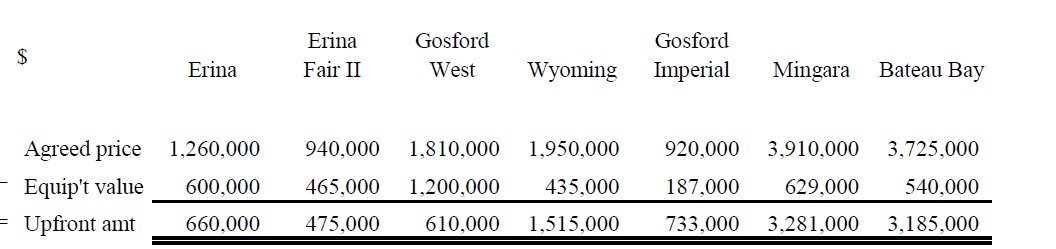

8 The terms of the offer letters in relation to the option to reduce the percentage rent for each of the Group One restaurants are summarised below:

Restaurant - letter | Commenced | End date | Higher % rent | Reduced % rent | Upfront amount / Prepayment of rent ($ excluding GST) |

Erina (RM-8) | 1 December 2005 | 25 October 2018 | 11.82 | 8.25 | 660,000 |

Erina Fair II (RM-7) | 1 December 2005 | 2 June 2018 | 13.93 | 9.40 | 475,000 |

Gosford West (RM-9) | 12 December 2005 | 12 December 2025 | 12.22 | 9.50 | 610,000 |

Wyoming (RM-10) | 9 January 2006 | 9 January 2026 | 16.77 | 8.32 | 1,515,000 |

9 In all of the transaction documents the payments in issue are referred to as a prepayment of rent. As will be seen, that does not mean that the payments are necessarily to be characterised as rent such that they are outgoings of revenue.

10 Mr Mussalli accepted each of the offers to operate the Group One restaurants including to pay the “prepayment of rent” so as to reduce the percentage rent payable. He did this because, in his view, he could increase the turnover beyond MAL’s projections and would be better off because the MFT would derive a higher amount of net income.

11 Each FLL was subsequently executed by MAL and the MFT in respect of the Group One restaurants. Amongst other things, the “prepayment of rent” was paid on handover.

12 Subsequently, MAL made further offers to Mr Mussalli to operate existing McDonald’s Family Restaurants at Gosford Imperial, Mingara and Bateau Bay in New South Wales (the Group Two restaurants).

13 MAL and the trustee of the MFT executed FLLs in respect of:

(1) the Gosford Imperial restaurant on 21 December 2010;

(2) the Mingara restaurant on an unspecified date in November 2011; and

(3) the Bateau Bay restaurant on 13 December 2011.

14 The terms of the FLLs for the Group Two restaurants were relevantly similar to the FLLs for the Group One restaurants apart from including a new cl 2.02(c) of the lease which stated as follows:

If the Lessee exercises the Prepayment Option in the manner specified in clause 2.02(b), the percentage rent payable by the Lessee for the Term will be reduced to the amount calculated in accordance with item eight of schedule A (as adjusted in accordance with clauses 2.01(b) and (c), and any other clause of this Lease).

15 The same table as set out above (at [8]) but for the Group Two restaurants shows:

Restaurant - FLL | Commenced | End date | Higher % rent | Reduced % rent | Upfront amount / Prepaid rent ($) |

Gosford Imperial (RM-31) | 13 December 2010 | 13 November 2019 | 19.52 | 8.00 | 733,000 |

Mingara (RM-39) | 14 November 2011 | 14 November 2031 | 25.37 | 15.00 | 3,281,000 |

Bateau Bay (RM-43) | 12 December 2011 | 11 October 2019 | 25.44 | 15.00 | 3,185,000 |

16 The option to reduce the percentage rent was exercised in respect of each of the Group One and Group Two restaurants.

17 Mr Mussalli, who had previously held a senior position with MAL as State Manager for New South Wales (NSW), was well aware of MAL’s procedures and policies and was confident that he could also satisfy all requirements to enable MAL to renew the FLLs. Indeed, as at the first instance hearing date, four of the FLLs entered into by MFT had reached their end date. One had an increased term and one had been rewritten, each for different periods. The primary judge noted (at [26]) that:

(a) on 23 August 2013, MAL offered to increase the term of MFT’s FLL for Bateau Bay to 30 January 2028 provided MAL’s head lease for the site was extended. Under the terms of the offer, there was no requirement for MFT to pay a further amount to secure the lower rate of percentage rent for the increased term, although MFT had to pay MAL a new franchise fee of $24,922 plus GST and a new documentation fee of $5,000 plus GST. Mr Mussalli accepted the offer to increase the term on 20 September 2013;

(b) Mr Mussalli gave evidence that the FLL for Gosford Imperial, the initial term of which expired on 13 November 2019, was rewritten for another eight years in early December 2019 at 9% (being 1% higher than the lower percentage rent that applied during the initial term) without having to pay a further upfront amount;

(c) although the end dates of Erina and Erina Fair II had also passed (on 25 October 2018 and 2 June 2018, respectively), these FLLs had not yet been formally rewritten, extended or renewed. Rather, MFT continued to operate those restaurants on a holding over basis on the same terms as under its expired FLLs; and

(d) apart from one store, Bateau Bay, the FLLs did not provide for any refund of the payment. The FLL for Bateau Bay, in cl 17 of the lease, provided for a refund of $470,000 of the total payment of $3,185,000 on expiry of the head lease on 12 October 2019 if MAL could not obtain a further term of the head lease.

18 MFT claimed the following deductions in calculating its net income under s 95 of the ITAA 1936 in the years of income to which the proceedings related, namely, the years ended 30 June 2012, 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015 as follows:

Restaurant | 2012 year deduction | 2013 year deduction | 2014 year deduction | 2015 year deduction |

Erina | $66,000 | $66,000 | $66,000 | $66,000 |

Erina Fair II | $47,500 | $47,500 | $47,500 | $47,500 |

Gosford West | $61,000 | $61,000 | $61,000 | $61,000 |

Wyoming | $151,500 | $151,500 | $151,500 | $151,500 |

Gosford Imperial | $82,206 | $82,206 | $82,206 | $82,206 |

Bateau Bay | $265,417 | $318,500 | $318,500 | $318,500 |

Mingara | $205,062 | $328,100 | $328,100 | $328,100 |

Total: | $878,685 | $1,054,806 | $1,054,806 | $1,054,806 |

19 Amended assessments of income tax that were issued to each of the appellants in these proceedings were consequential on the deductions claimed by the trustee of the MFT in respect of the upfront amounts being denied and therefore the net income of the MFT, and therefore MIT, being recalculated for the purposes of s 95 of the ITAA 1936 for each of the relevant years. In particular, the appellants were each assessed in respect of their share of the recalculated net income of the MFT or MIT, as appropriate, to which they were at that time entitled under s 97 of the ITAA 1936. The amounts in dispute for each appeal are set out as follows:

Proceeding (No NSD of 2018) | [Appellant] | 2012 year | 2013 year | 2014 year | 2015 year |

2064 | Benjamin Mussalli | - | $26,367 | $52,740 | $47,466 |

2065 | Ronald Mussalli | $197,704 | $237,332 | $210,961 | $216,235 |

2066 | Saroncorp | $439,342 | $527,403 | $527,403 | $527,403 |

2067 | Sandra Mussalli | $197,704 | $237,332 | $210,961 | $216,235 |

2068 | Daniel Mussalli | $43,935 | $26,367 | $52,740 | $47,466 |

20 The primary judge set out the relevant legal principles at some length (at [33]-[42]). The appellants do not appear to take issue with the statements of principle although they rely on additional propositions. The appeal turns on the proper application of the principles.

21 Her Honour noted (at [55]) Mr Mussalli’s evidence to the effect that, contrary to MAL’s documents which said that all franchises were renewed when they expired, there had in fact been a few franchisees who had chosen to exit when he was State Manager in NSW. Those franchisees assigned their rights to another franchisee or to MAL. He said that sometimes MAL renewed FLLs and sometimes it did not. Franchisees who did the wrong thing could also have their FLL terminated. Overall, however, to his knowledge a substantial number of stores had operated for more than 20 years by the same franchisee which was a result of MAL renewing the FLLs for those stores to the existing franchisee. As the primary judge noted, Mr Mussalli was also confident he could meet all of MAL’s policy requirements in order to obtain renewals of FLLs. He did not have any assurance from MAL that the FLLs would be renewed on expiry.

22 Significantly, the primary judge accepted (at [59]) the Commissioner’s submission that the way in which the payments were calculated was relevant to the characterisation of the payment: Commissioner of Taxation v Creer [1986] FCA 166; (1986) 11 FCR 52 per Fisher J (at 59-60) and Commissioner of Taxation v Star City Pty Limited [2009] FCAFC 19; (2009) 175 FCR 39 per Dowsett and Jessup JJ (at [192] and [259] respectively). On this point, the primary judge heard competing evidence from forensic accountants; Mr Halligan for the Commissioner and Mr Lonergan for the appellants. The fact that evidence of the experts involved expert inference about how MAL had calculated the payments did not, in her Honour’s assessment, undermine the admissibility or cogency of their evidence.

23 The primary judge noted (at 61]) that the essential dispute between the experts was expressed in their joint report in these terms:

The experts disagree on MAL’s figure for of [sic] the upfront amount:

(a) Mr Halligan’s opinion is that in its selling models MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’;

(b) Mr Lonergan’s opinion is that whilst prima facie the upfront amount is the difference between the “agreed price of the restaurant” and the ‘value of the equipment’, the upfront amount represents the capitalised value / net present value of the rental differential terms offered to Saronbell.

24 Mr Halligan explained that:

… for each selling model, MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’ as shown in the following table. For example, in the case of Erina the cell O28 of the P&L worksheet of the selling model shows ‘Prepaid Rent’ of $660,000 (i.e. the upfront amount). The Excel formula underlying that cell (which is only visible in the electronic version of the model) calculates this figure of $600,000 by taking the figure of $1,260,000 for the ‘Agreed Price’ that appears in cell B40 of the Valuation worksheet and deducting from it the figure of $600,000 for ‘Equipment’ that appears in cell O27 of the P&L worksheet.

25 The primary judge noted (at [63]-[66]):

63 According to Mr Halligan:

…the upfront amount is a not a prepayment of rent due under the lease agreement but rather a payment to ensure that the lease will contain a particular term that [MFT] desires – that is, a term that provides for percentage rent at the lower rate stated in the letter of offer or proposal for the entire term of the lease.

64 Mr Lonergan explained that:

… the correct description is ‘shows’ not ‘calculates’. Just because the amount appears as the last item (or second last) in a table, does not mean that is how the item was calculated.

MAL’s precise calculations are not known. However, given their use of capitalised earnings to calculate the total value of the restaurant, the upfront amount is the present value of the rental differential offered to [MFT].

65 According to Mr Lonergan:

… in accordance with the transaction documents, the upfront amount is a prepayment of the rental differential arising from the two alternate rent terms offered to the lessee by MAL in the transaction documents. The dollar amount is the present value of that rental differential.

66 Mr Halligan disagreed with Mr Lonergan, observing that:

First, the calculation of the upfront amount is not a present value calculation of the rent differential or a present value calculation of anything at all. As noted on page 8, Halligan notes that in the selling model for each restaurant MAL calculates the upfront amount for the restaurant as the difference between the amounts described in the model as the ‘agreed price of the restaurant’ and the ‘value of equipment’. Hence, it is clear that the calculation of the upfront amount is simply the deduction of one number (the value of equipment) from another (the agreed price of the restaurant) and not a present value calculation.

Second, notwithstanding that the calculation of the upfront amount is not a present value calculation, there is nothing about its inputs that means it ‘reflects’ or ‘relates solely to’ a present value calculation of the rent differentials. As noted, the inputs are the agreed price of the restaurant and the value of equipment, which are determined as follows:

(a) The agreed price of the restaurant is calculated by taking the annual profit and multiplying it by a capitalisation multiple. The annual profit is calculated after deducting rent that includes percentage rent at the lower rate. The higher rate of percentage rent is not an input to the calculation of the annual profit or indeed to the calculation of any other figure in the selling model. As a result of the capitalisation, the agreed price is the present value of the future stream of profits.

(b) The value of equipment is a fixed sum determined outside of the selling model.

…

Third, the higher rate of percentage rent cannot be determined without first determining the upfront amount. The higher rate of percentage uses the upfront amount as an input. …the higher rate of percentage rent is a rate derived by adding to the lower rate of percentage rent an additional percentage of gross sales revenue (estimated for the first year of [MFT’s] operation of the restaurant) which, when applied to the estimated gross sales revenue in the first year, results in an amount equal to the amount of prepaid rent divided by the valuation multiple.

26 The primary judge preferred the evidence of Mr Halligan to that of Mr Lonergan, noting that Mr Halligan’s evidence was that the upfront amount was calculated simply by MAL subtracting the value of equipment from the “agreed price of the restaurant”. The agreed price was determined through MAL’s valuation of the restaurant using a capitalisation multiple of between 4.76 and 5.50 times the anticipated profit of that restaurant in a single year, importantly, irrespective of the term of the particular FLL.

27 Further, in calculating the anticipated profit, Mr Halligan’s evidence was that MAL’s models always utilised the lower percentage rent. The electronic models used by MAL to calculate the agreed price, upfront amount and the higher percentage rent began with certain figures that were “hardcoded”, including the lower rate of percentage rent, the multiple used to determine the agreed price and the value of the equipment. In her Honour’s view, this strongly supported Mr Halligan’s evidence about the way in which MAL had calculated the payments.

28 Her Honour also accepted the Commissioner’s submissions about the difficulty with Mr Lonergan’s evidence that the upfront amount reflected a present value calculation of the difference between the lower and higher percentage rents. The analysis never yielded the precise amount of the payment. In one case, Gosford Imperial, the difference between the present value as calculated by Mr Lonergan and the payment was 11.8% ($646,196 compared to $733,000). In another, Bateau Bay, the difference was 12.1%. In two other cases the difference was 8% or close to 8% (Wyoming and Gosford West). The degree of difference between Mr Lonergan’s calculations of net present value of the difference between the higher and lower percentage rents and the payments depended on the duration of the cash flows so that the “shorter cash flows, the more inclined the capitalised earnings method is to misstate the real value”. As the Commissioner submitted, the “equivalence” that Mr Lonergan proposed between the payments and the present value of the difference between the higher and lower percentage rents was not actual equivalence and the approximations of equivalence only held good for FLLs granted for a term of more than 10 years.

29 The Commissioner also submitted, and the primary judge accepted, that Mr Lonergan’s approach involved circular reasoning in that his evidence was that the payments were calculated by MAL as an output, using the lower percentage rent as an input, which was then used by MAL as an input into the calculation of the higher percentage rent. As the Commissioner put it, Mr Lonergan’s calculations of the present value of the rent differential simply reversed MAL’s methodology for calculating the upfront amount. Her Honour also accepted Mr Halligan’s evidence that MAL’s electronic model did not calculate the payments using a discounted cash flow analysis to produce a present value of the rent differential. Mr Halligan also noted that extracts of MAL’s models had been provided to Mr Mussalli for some of the restaurants and as Mr Halligan explained:

…there are extracts from it attached to this very letter that we’re looking at and from those extracts you can work backwards and should be able to work backwards to determine the agreed price or the value of the restaurant that MAL put on it and which you should also then be able to work backwards to determine that the sum of the upfront amount and the equipment equals the agreed value of the restaurant.

30 For these reasons her Honour accepted the Commissioner’s submission that the way in which MAL calculated the payment was as the residual left over after deducting the value of the equipment from the agreed price determined by reference to a valuation based on a multiple of between 4.76 and 5.50 times yearly earnings, irrespective of the term of the FLL.

31 The primary judge noted that in Tyco Australia Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2007] FCA 1055; (2007) 67 ATR 63 (at [82]) Allsop J (as his Honour then was) noted that accounting evidence cannot be determinative but did not suggest it was irrelevant. Against this background it was also noted that the trustee of the MFT recorded the payments as an asset in its balance sheet. The experts agreed that this accorded with the accounting treatment for ‘prepaid lease payments’ under Australian Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (Australian GAAP), irrespective of whether the upfront amount was characterised as prepaid rent or as something else for accounting purposes.

32 After recording the parties’ submissions (at [81]-[88]), which submissions are repeated on appeal (together with further submissions), the primary judge concluded that whether the transaction documents are considered in isolation or in the context of the surrounding circumstances, either in isolation from or together with the accounting evidence, the better view was that the payments in dispute were of a capital nature. They were a one off, lump sum, non-refundable payment made to secure an enduring advantage (the right to pay the lesser percentage rent) for the term of the FLL and most likely the term of any renewal of the FLL. The payments actually negated or extinguished any obligation to pay the higher percentage rent and did not thereby relate to any future obligation to pay rent. As a matter of substance the payments, although called the prepayment of rent, did not involve the payment of rent at all.

33 Her Honour found (at [117]) that the payments were not made to secure to the trustee of the MFT the use and enjoyment of each restaurant over the term of its lease. The trustee of the MFT did not have to make the payments to secure that advantage which was otherwise secured. The payments did secure the enduring advantage of acquiring a preferable business structure, being one which involved the payment of a lower percentage rent over the term, and most likely any renewed term, than would otherwise be the case. From a “practical and business point of view” (Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Sharpcan Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 36 at [17]; (2019) 373 ALR 414 at [18]) the payments were calculated to effect the acquisition of a right to operate the franchises on better terms as to rent than otherwise would have been the case. In the language of Sharpcan (at [18]) the payments were to secure the acquisition of a different (and better) means of production rather than the use of those means of production. They were payments to enable a preferable business structure to be established rather than payments for the carrying on of the business. They were not concerned with the regular performance of the work. They were concerned with the nature and profit-making structure of the business and, indeed, necessary to acquire the business with that particular profit-making structure (the obligation to pay only the lower percentage rent). Further, if a comparison were made of the expected structure of the business after the outgoing with the expected structure but for the outgoing, it is apparent that the trustee of the MFT gained the advantage of a business with a preferable profit-making structure for the duration of the leases and thereafter on any renewal. From the evidence of Mr Mussalli, her Honour said it was apparent that this is what the trustee of the MFT really made the payments for, which were payments of capital or of a capital nature.

34 Her Honour continued (at [118]-[121]):

118 Mr Mussalli’s evidence, that he made the payments because he concluded that it would be financially better to pay the lower percentage rent for each store, confirms that the advantage sought to be obtained in each case was a business with a better profit-making structure. The lower percentage rent meant that the greater turnover Mr Mussalli anticipated he could make from the stores would yield even greater financial benefits over the duration of the FLLs and, on Mr Mussalli’s anticipation, the likely renewal of those arrangements. The fact that MAL offered the different profit-making structure via the lower percentage rent option on a take it or leave it basis does not change its character. The payments were not made for the occupancy of the stores. Other payments secured occupancy whether or not the upfront payments were made. The upfront payments secured a more advantageous profit-making structure for the stores acquired.

119 For these reasons I do not agree with the [appellant’s] submission that the making of the payments did not affect the structure of the businesses acquired. What MFT acquired through the payments was a business with a different structure, a business in which the percentage rent payable was permanently reduced from what it otherwise would have been. This is an important aspect of the profit-making structure of the business which Mr Mussalli plainly recognised. I thus do not accept that the structure of the business but for the outgoing is identical to the structure of the business after the outgoing. The payments achieved a different business structure via the permanent reduction in the percentage rent payable.

120 In response to the [appellant’s] propositions at [86] above:

(1) the fact that the parties labelled the payments as a prepayment of rent is not determinative of their true character. The payments were plainly not on account of a subsequent obligation to pay rent. They operated to change the obligation itself, so that a proportion of the percentage rent was not payable at all. Such a payment is not a prepayment of rent in any sense irrespective of the label the parties chose to affix to the payments;

(2) while the payments were not for the same advantage as found in Star City and Creer, as I have said, they were payments to obtain an enduring advantage of a better profit-making structure for the businesses than would otherwise have been available;

(3) the benefit MFT obtained was an enduring one. The obligation to pay the higher percentage rent was commuted for the duration of each FLL and, in Mr Mussalli’s anticipation, for all renewals of the FLLs. The fact that MFT obtained the benefit of not having to pay the higher percentage rent on a monthly basis does not change the character of the payment that was made – a one off lump sum payment to obtain an enduring advantage by the alteration effected to the profit-making structure of the business;

(4) MAL’s indifference to the choice that the MFT made is immaterial;

(5) the MFT accounted for the payments as an asset irrespective of the label affixed of prepayment of rent;

(6) the period over which the payments had their effect does stamp them as of a capital nature. Section 82KZM of the ITAA 1936 is immaterial; and

(7) the payments were not recurring. Seven individual payments were made, one for each business. The MFT was not in the business of buying and selling MAL stores. The MFT made one off lump sum payments on each occasion it acquired a franchise which is consistent with the payments being of capital or of a capital nature.

121 The payments were not components of the rent. The payments commuted the obligation to pay the higher percentage rent. In making them the MFT did obtain an asset, right or advantage other than occupation and use of the stores. It obtained a business with a different profit-making structure than would otherwise have been the case. In these circumstances, the fact that the payment of rent is generally deductible even if it is paid in a lump sum is immaterial. The payments were not for rent but to alter an obligation that otherwise would have existed to pay the higher percentage rent. As a result it would not be “odd”, in my view, if the prepayments were not deductible.

35 The primary judge held further that:

(1) the MFT did obtain by the payments a business which had a different profit-making structure from the one it otherwise would have acquired. If the MFT had not made the payments it would have been obliged to pay the higher percentage rent. Having made the payments MFT commuted that obligation and, thereby, obtained a business with a different profit-making structure by reason of the obligation to pay only the lower percentage rent;

(2) it may be accepted that this did not involve the MFT in obtaining any exclusivity or territorial rights or the offer of any other store. But obtaining a business with a different, better profit-making structure is an enduring asset which the MFT did obtain by making the payments;

(3) it may be accepted that the payments were not made for goodwill in the sense of the attractive force which brings in custom;

(4) MFT did obtain the right to acquire a business with a better profit-making structure than would otherwise have been the case, which is a valuable and enduring right;

(5) it may be accepted that there was no automatic right for renewal of the FLL, but Mr Mussalli was confident he knew MAL’s policies well enough to ensure that he could obtain renewals which would be at the lower percentage rent, further confirming the enduring character of the advantage which was sought and obtained by reason of the payments. The occasions on which MAL did not renew FLLs or terminated them, on Mr Mussalli’s evidence, were the result of franchisees not complying with MAL’s policies. Mr Mussalli was confident he would obtain renewals at the lower percentage rent or a small, capped increase thereon. Indeed, Mr Mussalli’s confidence appears to have been well-founded, with a number of the FLLs continuing beyond their initial term (see above at [17]); and

(6) the MFT did obtain an enduring advantage from the payments. It is not necessary that it obtain any asset for the payments to be of capital or of a capital nature.

36 As to the surrounding circumstances, her Honour found that the evidence supported the inference that the benefit of the lesser percentage rent secured by the upfront payments would endure beyond the initial term of the FLLs and that Mr Mussalli, as the controlling mind of the MFT, was aware of this fact. This, the primary judge said, also supported the fact that the payments were not to secure the mere use and occupation of the premises during the term of each lease. Her Honour also held that it was relevant that the means by which the enduring advantage was secured was a one off, lump sum, non-refundable payment. As the Commissioner said, the fact that the payments were made for each restaurant does not make them recurring. There can be no suggestion that the restaurants were trading stock acquired in the course of a business of buying and selling the franchises as Mr Mussalli confirmed that he had no intention of selling the franchises.

37 Her Honour emphasised that she had reached the conclusion that the payments were of capital or of a capital nature, irrespective of the accounting evidence.

GROUNDS OF APPEAL

38 The appellants contend for several errors on the part of the primary judge. They say that:

1. The primary judge erred in finding that the amounts incurred by the trustee of the Mussalli Family Trust (MFT) and described as “prepayments of rent” by it and its landlord, McDonald’s Australia Limited (MAL), (the payments) were outgoings of capital or of a capital nature under s 8-1(2) of the [ITAA 1997] and were not allowable as deductions pursuant to s 8-1(1) of the [ITAA 1997].

2. The primary judge ought to have found that the payments were not on capital account under s 8-1(2) of the [ITAA 1997] and accordingly were allowable as deductions under s 8-1(1) of the [ITAA 1997].

3. The primary judge erred at [117] - [121] in finding that, from a practical and business point of view, the payments were calculated to effect the acquisition of a right to operate the franchises on better terms as to rent than would otherwise have been the case and to enable a preferable business structure to be established.

4. The primary judge ought to have found that from a practical and business point of view the payments were calculated by the MFT to effect the use and enjoyment of each store each month over the term of the lease in carrying on its business of operating a McDonald’s restaurant as a licensee of MAL at that store.

5. The primary judge erred at [117] in finding that the payments were necessary to acquire the business with a particular profit-making structure and ought to have found that the payments were made in carrying on the MFT’s business.

6. The primary judge erred at [117] by misapplying the decision of the High Court in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Sharpcan Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 36 at [33] in finding that the MFT acquired a different profit-making structure by the making of the payments and ought to have found that the payment did not change or result in the acquisition of the structure of the business but only changed the outgoings incurred in carrying on that business.

7. In making these findings the primary judge erred:

a) at [43] in finding that the objective determination of the nature of the advantage sought by the MFT was not limited to the subjective state of awareness of Mr Mussalli, the controlling mind of the trustee of the MFT. In so doing the primary judge failed to correctly apply AusNet Transmission Group Ply Ltd (2015) 255 CLR 439 at (23), (66) and Federal Commissioner of Taxation v South Australian Battery Makers Pty Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 645 at 656. The primary judge ought to have found that the objective determination of the nature of the advantage sought by the MFT did not include matters of which Mr Mussalli was unaware;

b) at [120(5)] in finding that it is relevant that the MFT accounted for the payments as an asset notwithstanding that the MFT and MAL were dealing at arm’s length with each other, and that the MFT accepted MAL’s characterisation of the payments as prepaid rent in the letters of offer, leases and tax invoices, and treated them as such in its profit and loss statements and balance sheets each year;

c) at [59]-[60] in finding that the expert evidence of Mr Halligan and Mr Lonergan, as valuers, relating to internal calculations of the recipient of the payments, MAL, is relevant to the determination of what the MFT calculated the expenditure to effect, notwithstanding that MAL unilaterally determined the terms of the lease (including the optional prepayment, the higher percentage rent and the lower percentage rent) on a take it or leave it basis;

d) at [72] and [80] in finding that the expert evidence of an accountant is relevant to the objective determination of what the MFT calculated to effect in incurring the expenditure. In doing so the primary judge failed to take into account the decisions of Gordon J in SPI PowerNet Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2013) 96 ATR 771 at [99] and Perram J in Healius Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCA 2011 at [47] without deciding that they were distinguishable or clearly wrong. Had the primary judge taken these decisions into account the primary judge would have concluded the expert evidence of an accountant to be irrelevant;

e) at [129] in finding that as no evidence was led that the percentage rents represented a fair market rent, that the applicant’s onus of proof meant that they could not exclude a conclusion that the rights secured by the payments conferred an enduring and valuable benefit on the MFT. Alternatively the market rent is the rent (including the payments) which the MFT agreed to pay. In any event, the issue is not determinative of the onus of proof;

f) in finding at [115] and [125] that the payments were not refundable.

39 Ultimately, it appeared that not every complaint was specifically pursued and in any event, the appeal was argued on a basis that does not require a robotic examination of each ground.

40 The appellants argue that the primary judge’s finding that the relevant payments made by the MFT “negated or extinguished any obligation to pay the higher percentage rent” (at [115]) also described as “lower percentage rent … than would otherwise be the case” (at [117]) is incontrovertible and answers the critical question of what the payment was for (Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1953) 89 CLR 428 per Fullagar J at 455) and identifies the character of the advantage sought: GP International Pipecoaters Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1990) 170 CLR 124 (at 137). It is asserted that a payment made to secure a reduction in a revenue outgoing is itself on revenue account. Where, as in this case the payments were not for the acquisition of an asset, “the character of the expenditure is ordinarily determined by reference to the nature of the asset acquired or the liability discharged by the making of the expenditure”: GP International (at 137). This conclusion is also consistent with the principles which were enunciated by the High Court in Commissioner of Taxation v Myer Emporium Ltd (1987) 163 CLR 199 (at 218) that where a taxpayer sells a right to interest for a lump sum “the taxpayer simply converts future income into present income”. Here, it is said the taxpayer has simply converted a future revenue outgoing into a present revenue outgoing. The payments in question did not secure any change in the relevant assets acquired by MFT, namely the leasehold interest (or the leasehold interest and the franchise). The leasehold interest acquired by MFT in each case was not altered by the payment nor was there any change to the franchise. The only thing that changed as a result of each payment was the consideration payable under the lease, namely the percentage rent.

41 The appellants suggest that the primary judge’s characterisation of the reduction in percentage rent being an advantage of a capital nature involved a misunderstanding of the capital/income dichotomy. It is said that her Honour conflated the consideration for the right to occupy, namely the rent, with the character of the leasehold interest. Her Honour’s statement (at [115]) that the payments did not relate to any future obligation to pay rent simply cannot be reconciled with her finding (at [117]) that the payments secured “the payment of a lower percentage rent”. Her Honour’s conclusion that the “payments were calculated to effect the acquisition of a right to operate the franchises on better terms as to rent than otherwise would have been the case” involves a mischaracterisation of what she had correctly found that the payments were “for”, namely a reduction in future rent. Whether or not the relevant payments were made, the appellants point out the asset(s) acquired by MFT in each case did not change. The leasehold interest, and if it matters the franchise, were identical whichever payment option was chosen.

42 By way of preface to the appellants’ arguments, the following four propositions are said by them to govern the deductibility of the payments at issue in this proceeding. They will then be examined more closely.

43 First, it is contended that the character of the advantage sought is the “chief, if not the critical, factor in determining the character of what is paid”, and where the payment discharges a liability it is the character of the liability that determines the character of the payment: GP International per Brennan, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ (at 137). Here there is no doubt, it is contended, that her Honour correctly found that each payment was made to obtain a reduced rental payment. It is accepted that whether or not any of the two groups of payments are correctly described in the documents as a “prepayment of rent” is not determinative one way or another. What matters is that the payments did not change the leasehold interest or the franchise, nor was it a payment for the grant of the leasehold interest. All that changed was the liability for the percentage rent which was reduced.

44 Secondly, it is contended that a lump sum paid to reduce or eliminate future revenue expenses is generally to be characterised in the same way as the expenses for which they are substituted: National Australia Bank Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1997) 80 FCR 352 (at 364) (NAB); Spotlight Stores Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [2004] FCA 650; (2004) 55 ATR 745; Hancock (Surveyor of Taxes) v General Reversionary and Investment Company Limited [1919] 1 KB 25; see also W Nevill & Co Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1937] HCA 9; (1937) 56 CLR 290 (at 306).

45 Thirdly, the appellants contend that when considering the advantage sought, the characterisation of expenditure must be considered from the perspective of the taxpayer, not the recipient, although in this case the recipient treated the payments as assessable rent: AusNet Transmission Group Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2015] HCA 25; (2015) 255 CLR 439 (at [66]), Visy Industries USA Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2011] FCA 1065; (2011) 85 ATR 232 (at [125]).

46 Fourthly, it is said that the fact that an outgoing relates to a period of years and is not recurrent does not preclude the outgoing from being on revenue account: Associated Newspapers Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1938) 61 CLR 337 per Dixon J (as his Honour then was) (at 362) (Sun Newspapers); Anglo-Persian Oil Co Ltd v Dale (1932) 1 KB 124; [1931] All ER Rep 725; Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Lau (1984) 6 FCR 202 per Beaumont J (at 221); see also Fox J (at 208); Tyco per Allsop J (as his Honour then was) at [47].

Character of the advantage sought

47 The appellants argue that both from a jurisprudential view and from a practical and business point of view, the advantage which MFT sought by incurring the payments was to reduce its rental expenses for the term of each lease. This objective was achieved without changing the business or the business structure. The rights granted to MFT under the lease and the franchise did not change. The appellants contend that contrary to the finding of the primary judge, the payments did not give rise to the acquisition of a “preferable business structure”. They contend that her Honour did not explain what the so called “preferable business structure” was save for identifying the reduced revenue expenditure. But the appellants say that the nature of the business remained the same, the premises from which the business operated remained the same as did MFT’s right to occupy those premises, the franchise remained the same as did the plant and equipment employed in the business. Each payment is said to have only altered the timing and quantum of the consideration payable for the use of the leased premises. Thus, the appellants say they were incurred in the process of operating the profit-yielding subject of the business rather than incurred in establishing or enlarging that subject, and therefore are revenue in nature: Sun Newspapers Ltd per Dixon J (as his Honour then was) (at 360).

48 The appellants point out that this is not a case where the payments secured what was “necessary for the structure of the business” (Sharpcan at [18]). Adopting the counterfactual analysis described in Sharpcan (at [33]), they say “a comparison of the expected structure of the business after the outgoing with the expected structure but for the outgoing, not with the structure before the outgoing” reveals that the only difference arising from the making of the payments was a change to the consideration payable by MFT for using the leased premises. The premises leased, and the term for which they were leased, did not change. The payments did not secure for MFT the right to operate a business or any goodwill. MFT was granted a separate lease and licence for each restaurant site. The leases did not confer any right to operate a business, but only a right to occupy the leased premises. The lease (and the licence) was, or was to be, granted regardless of the payment. As for the licence, MFT obtained the right of a franchisee under the FLL for each store to operate a McDonald’s family restaurant business from the leased premises in accordance with the “McDonald’s system” and using the licensed intellectual property for the duration and on the terms of the licence granted by MAL, by payment of the licence fee, system fee and service fee, and paid a separate additional amount for the plant and equipment at the store. In this respect the amounts paid may be contrasted with the capital outgoings at issue in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Healius Ltd [2020] FCAFC 173, which the Court found secured an “essential part of Idameneo’s business” which formed part of “the commercial infrastructure that was then deployed by Idameneo to earn its revenue by attracting patients to its Centres” (at [15] of the Full Court’s joint reasons). The position is said to be made even clearer in the case of Group Two restaurants, where the amounts described by MAL as prepayments of rent were paid pursuant to the terms of the leases entered into as opposed to the terms of the agreement to lease.

Payment in substitution of a revenue outgoing remains on revenue account

49 The appellants contend that it is uncontroversial that, as a general rule, rent is deductible on account of it being a revenue expense: Texas Co (A/asia) Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1940] HCA 9; (1940) 63 CLR 382 (at 468); Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v South Australian Battery Makers Pty Ltd [1978] HCA 32; (1978) 140 CLR 645 per Gibbs ACJ (with whom Stephen and Aickin JJ agreed) (at 655), the dissentients, Jacobs J (at 669-670) and Murphy J (at 672-673) accepted the principle but found that there was another purpose for the payments in that case, namely the reduction of the purchase price to be paid by an associated entity under an option. The appellants say that no such alternate purpose exists here. Here there is no suggestion of sham or that the amount was paid to secure a reduction in the purchase price of another asset: cf Creer. Further, as the payments were merely a lump sum substitute for future rental expenses, the appellants say they retain the same revenue character as those expenses. The line of authority supporting this proposition is said to commence with Hancock per Lush J (at 37-38).

50 The appellants also rely on Anglo-Persian (endorsed by Latham CJ and Dixon J in Sun Newspapers) where the English Court of Appeal held that a one off “payment … to put an end to an expensive method of carrying on the business which remains the same” (as described by Lord Hanworth MR (at 732)), being the end to existing agency arrangements, was on revenue account because, as Romer LJ said (at 737), the change “would lead to the economy and saving in working expenses …”. In the same year, in IRC v Longmans Green & Co Ltd (1932) 17 TC 272, Finlay J held that a payment received as a lump sum in substitution for future royalties that the taxpayer would otherwise have received remained on revenue account rather than being characterised a capital account. (The reasoning in this case was later applied by the Full Federal Court in the context of deductions in NAB). In W Nevill the taxpayer incurred an outgoing of £2500 to a managing director of the taxpayer in consideration for the cancellation of the services agreement under which the managing director had been engaged. The Court concluded (with reasoning endorsed by the majority in Ausnet at [17]) that, for the purposes of the positive limbs of what is now s 8-1, the outgoing ought to be characterised in the same manner as the salary that would have otherwise been payable to that managing director and that the payment made was not on capital account. Dixon J concluded (at 306) that although the payment was “unusual” for the taxpayer, it was on revenue account by reason of it being made:

… for the purpose of organizing the staff and as part of the necessary expenses of conducting the business. It was not made for the purpose of acquiring any new plant or for any permanent improvement in the material or immaterial assets of the concern. The purpose was transient and, although not in itself recurrent, it was connected with the ever recurring question of personnel…

51 The appellants point to other international authorities which align to this reasoning on both the revenue and expense side of the equation. For example, in Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. P.G. Lake, Inc. (1958) 356 US 260 (later endorsed by the High Court in Myer Emporium), the US Supreme Court held that a lump sum receipt remained assessable as income, not capital as it was merely “converting future income into present income”.

52 In Lau, the Full Court characterised an upfront management services fee paid for a period of 21 years as being on revenue account. Beaumont J said (at 221):

… The learned judge found that the fee paid to NQ was, in truth, paid on account of management services which were to be rendered, if not continuously, then recurrently, over a period of twenty one years. In this context, it is appropriate to refer to the contractual quid pro quo to determine the nature of the outgoing (see Magna Alloys & Research Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1980) 49 FLR 183 at 191, 208) and, prima facie, moneys outlaid in return for such recurrent services are paid on revenue account. In my view, the circumstance that the fee is to be paid as a lump sum in advance is not sufficient to displace this presumption. The important considerations are the nature of the services to be rendered and the periodic manner in which they are to be rendered. In my opinion, the outgoings fell within s 51, being directed not to the profit yielding subject of the taxpayer’s business but to the process of operating it (see Ferguson v Commissioner of Taxation (1979) 37 FLR 310 at 317).

53 The appellants’ position with respect to a lump sum paid in advance in substitution for future revenue outgoings is also said to be supported by the reasoning of the High Court in Myer Emporium, where the Court said with respect to a lump sum paid in advance in substitution for future interest income (at 218-219):

… If the lender sells his mere right to interest for a lump sum, the lump sum is received in exchange for, and ordinarily as the present value of, the future interest which he would have received. This is a revenue not a capital item – the taxpayer simply converts future income into present income: see Commissioner of Internal Revenue v P.G. Lake Inc.. By a transaction consisting in the making of a loan and a sale of the right to interest on the money lent, the lender acquires at once a debt and the price which the sale of the right has fetched. The price of the right is the lender’s compensation for being kept out of the use and enjoyment of the principal sum during the period of the loan and, like the interest for which it is exchanged, it is a profit. It is immaterial that the lender receives the profit not from the borrower but from the other party to the transaction, and it is immaterial that the profit is received immediately and not over the period of the loan.

(Citations omitted.)

54 In 1997, in NAB, the Full Court concluded that a lump sum payment of $42 million, given in return for exclusive rights to market mortgages to defence personnel for a period of 15 years (with the potential outcome of receiving interest on mortgages for a further 25 years after that) was revenue in nature. The Court said (at 363):

Given that the $42 million and the recurrent payments are payable for the same advantage, it would be curious if the former were to be characterised as a payment of capital when it was computed on the basis of the number of expected loans. It is true that Longmans Green was concerned with the character of a receipt and not an outgoing. But the common sense point made by Finlay J is applicable whether the components of an overall consideration in respect of the same subject matter are to be characterised in a receipt or an outgoing context.

55 Applying the authorities outlined above, the appellants contend that here the payments were paid in “substitution” of future rent (per Hancock), to save future working expenses (being rent outgoings) in carrying on the MFT’s business, and the business was the same regardless of the payments (per Anglo-Persian). The payments were not made to acquire “any new plant or for any permanent improvement in the … assets” of the business. They formed part of the consideration payable for the use of the leased premises for which MFT had a periodic tenancy. As such, given that the necessary expenses of conducting the trustee’s business included the payment of rent, it is asserted that the payments are properly regarded, as one of the ongoing expenses of that business and on revenue account. It would be odd that recurrent percentage rent is deductible but the payments substituted for it are not. In precisely the same fashion as the position described in Myer Emporium, converting a future revenue expense (in the form of rent) to a present expense does not convert the expense from being a revenue item into a capital one.

Perspective of the taxpayer

56 The appellants submit also that the primary judge erred in having regard to the internal calculations and valuation methodology of MAL in considering the deductibility of the payments in the hands of the MFT. To paraphrase the majority in Ausnet (at [66]), all of the evidence in relation to MAL’s internal documentation and calculations, “direct the inquiry away from the critical question – from [MFT’s] perspective what was the character of the advantage sought?”. There is no authority, it is said, for the proposition that internal calculations unilaterally made by a landlord in the process of determining the rent it will charge to a tenant can have any bearing on the tax characterisation of payments of rent made by a tenant with no involvement in such calculations: cf Creer, where the taxpayer/tenant dictated the terms of the lease to reduce the purchase price of the leased property. Based on MAL’s terms of offer, which left it to the potential tenant and licensee to choose the makeup of the consideration payable for each lease and licence from what MAL offered, MAL was indifferent as to whether MFT chose to make the prepayment or not.

57 Further, the appellants argue that the evidence of an accountant says nothing of the characterisation of an outgoing as income or capital under s 8-1 of the ITAA 1997 in these circumstances: Gordon J in SPI PowerNet Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2013] FCA 924; (2013) 96 ATR 771 (at [99]). In Healius (at [179]), the Full Court upheld the trial judge’s conclusion that “the way in which the Idameneo dealt with the Lump Sum amounts in its accounts reflected its view of how the accounting standards applied to those payments”. Specifically, at trial in that case Perram J found (at [47]): “The evidence of Mr Duff establishes that the accounting treatment was a result of the accounting standards and not of any particular perception about the nature of the transactions.”

That the payments were lump sum does not change their character

58 The appellants stress that the fact that a payment in lieu of the rent payable each month was “paid as a lump sum in advance is not sufficient to displace” the presumption that the moneys outlaid “are paid on revenue account”: see Lau per Beaumont J (at 221). Whether or not the payment is properly characterised as rent does not affect the fact that it is in lieu of rent as it is paid to obtain a reduced liability for rent. The appellants argue that the position is again reinforced by the reasoning in NAB. There, the Court said (at 365):

The $42 million was a once and for all payment. The absence of recurrence suggests that an outgoing is of a capital nature. But it is not conclusive: Sun Newspapers at 362-363 per Dixon J who referred to the Anglo-Persian case as an example of a one-off payment that was nevertheless deductible.

Three features of the present case dilute the significance of the fact that the $42 million payment was not to be repeated. The first is that the Bank wanted to make periodic payments. That would have been consistent with the advantage sought by the expenditure – income from the loans over the period of their existence. But the Commonwealth insisted on one lump sum payment in advance. However the character of the advantage sought by the Bank does not alter because the commercial realities of the situation dictated a payment of a lump sum rather than the periodic payments the Bank would have preferred to make. Compare Hancock v General Reversionary and Investment Co [1919] 1 KB 25 at 37-38. The second feature is that the agreement contemplates that the initial payment would be followed by 16 annual payments. The agreement thus envisages recurrence, though because the Scheme was not successful, only one payment was in fact made. The third feature is that had the 16 annual payments been made, they would have been on revenue account.

59 The appellants rely on three similar features, in this case which they argue negate the significance of the fact that the payments were not to be repeated. First, MFT had the option of making higher periodic payments in substitution for the single “prepayment”. Secondly, the agreements do in fact provide for the payments to be followed by monthly payments, thus envisaging recurrence. Thirdly, the monthly payments that followed were on revenue account. Further, on the issue of recurrence, in Sun Newspapers Dixon J said (at 362):

… the expenditure is to be considered of a revenue nature if its purpose brings it within the very wide class of things which in the aggregate form the constant demand which must be answered out of the returns of a trade or its circulating capital and that actual recurrence of the specific thing need not take place or be expected as likely. Thus, in Anglo-Persian Oil Co. Ltd v. Dale the establishment and reorganization of agencies formed part of the class of things making the continuous or constant demand for expenditure, but the given transaction was of a magnitude and precise description unlikely again to be encountered. Recurrence is not a test, it is no more than a consideration the weight of which depends upon the nature of the expenditure.

(Citations omitted.)

60 The appellants argue that if the relevant payments made by the MFT “negated or extinguished any obligation to pay the higher percentage rent”, this was also the advantage sought by the MFT in making the payments, accordingly they are revenue in nature. This is not a case where the effect of the payments was an unintended coincidence so that it might be said that the effect of the payments was not what the payments were for.

61 In this case the Commissioner says the “right to pay the lesser rent” was an enduring benefit and hence capital. The appellants say this contention misunderstands what the authorities have referred to as a structural benefit or advantage of a capital nature. Many revenue payments provide benefits over time and as such may be labelled as providing “enduring” benefits. If an employee is paid up front for two years of employment the payment will still be revenue notwithstanding that the payment secures the employment for a two year period. Regular advertising is likely to lead to improved goodwill and will provide benefits over the longer term but will still normally be on revenue account: see Sun Newspapers per Dixon J (at 361).

62 The appellants say that here the payments result in a reduction in rent over the term of the lease, and by their character – being in a practical and business sense part of the consideration given for the use of premises – they are “within the very wide class of things which in the aggregate form the constant demand which must be answered out of the returns of a trade or its circulating capital”. The nature of the payments also needs to be understood in the context of the Australian scheme of income tax which in Subdiv H of Pt III of the ITAA 1936 expressly provides a scheme for the deductibility over time, in this case 10 years, for certain upfront payments.

63 Although the Commissioner submits that the “payments were not incurred to secure the use and enjoyment, or occupation, of the restaurant premises”, the appellants say that it is difficult to imagine that they were paid for any other reason. The payment for the use and enjoyment or occupation of the premises either included the higher turnover rent or the lower turnover rent plus the payment in question. The choice was that of the tenant but either way it got the same rights to occupy and enjoy. The appellants stress that this is not a case like Star City or Creer where the taxpayer had a role to play in the form and calculation of the consideration payable; here the figures were presented to the MFT on a take it or leave it basis. In Star City, the Court relied on material created by the taxpayer’s own solicitors (described by Goldberg J at [54]-[58]). His Honour concluded (at [53]) that the taxpayer made the lump sum prepayment to obtain “the exclusive right to operate a casino for 12 years”. Here, no such material is said to have been created, and in any event, there was no exclusive licence or other right obtained – the payments simply reduced the percentage rent. Creer is also distinguishable, it is said, on the basis that the taxpayer was the “author of [the] form” of the transaction (per Wilcox J at 61), whereby the taxpayer made lease payments in direct substitution for the acquisition price of a residence.

THE COMMISSIONER’S POSITION

64 The Commissioner maintains the contentions advanced before the primary judge. He contends the analysis at first instance was correct.

CONSIDERATION

65 Before turning to the four key arguments summarised above (at [42]-[46]) it is essential to revisit the factual context to characterise the nature of the payments.

66 The evidence established that MAL operates two sorts of stores or restaurants. There are those that are owned by MAL, and those which are owned by franchisees. From time to time, MAL makes offers to individuals whom they consider suitable to take over a company-owned store and run it instead as a franchisee store.

67 Mr Mussalli was a high-ranking corporate officer in MAL with substantial experience. He had decided to move out of that employment position and sought from MAL the opportunity to take over and run as franchisee, via MFT, stores which had previously been run by MAL. Mr Mussalli was given detailed information on their previous and recent results so that he could make a decision as to whether MAL’s offers to operate the stores as franchisee were acceptable or not.

68 There were seven stores. On all seven occasions, between 2005 and 2011, Mr Mussalli chose to take over, pursuant to the terms of the FLL, operation of a store. It was also likely that the terms would be renewed beyond the initial period. On seven occasions Mr Mussalli made the lump sum upfront payments.

69 The FLL required him to step into the existing store, make a payment in respect of the existing movables located in the store, and take over running the store. The commercial attraction was that, as MAL was going to charge fees by reference to existing turnover, if Mr Mussalli could perform better than the store had been performing as a company-owned store, then it would be profitable for him to do so. There was to be a seamless takeover.

70 The letter of offer for Erina Fair II is an example of others in the Group One restaurants. The license term was almost 13 years from 2005 to 2018. There were various fees to be paid. The “percentage rent” is designated at 13.93% of monthly gross sales as defined. It shows equipment that MFT is required to purchase for $465,000 and there is an option to “prepay rent” in the amount of $475,000 described as follows:

EQUIPMENT: You are required to purchase from [MAL], all equipment, decor, furniture, fittings, signage and air conditioning (including all computer hardware and software) for $465,000 plus GST. [MAL] make no warranty in respect of the equipment, the equipment is purchased in its present condition.

OPTION TO

PREPAY RENT: This agreement includes an option for you to reduce your Percentage Rent, as referred to above, to 9.40% of monthly gross sales (as defined) plus GST minus the amount paid as base rent plus GST, subject to a prepayment of rent of $475,000 plus GST on the day of handover.

71 That prepayment reduced Mr Mussalli’s rent from 13.93% of gross sales to 9.4% of gross sales. MAL routinely values these stores, that is, the land and the business operated on them, by reference to a multiple of adjusted yearly profits. That multiple was approximately five to five and a half. In this case, MAL’s attribution of the value of the store was $940,000 which is the sum of the equipment purchase price and the optional upfront “rent prepayment”, ($465,000 and $475,000 respectively).

72 Mr Mussalli’s case was based on the language in the document (and others), that the $475,000 represented a prepayment of rent, and was therefore, revenue, as a payment in advance of a revenue expense. The Commissioner’s case was that it was not in truth a prepayment of rent in any sense of the word. In particular, it was not a payment made to be set off or applied against future rental obligations. It was a payment to gain a capital advantage.

73 The Commissioner’s expert said that from an accounting point of view, what was really being acquired was what he called a “lease right”. The payment secured a better version of the lease. Significantly this was supported by the way that MAL calculated the upfront amount as a residual which was left over after deducting the value of the equipment from the business price, itself determined by a valuation multiple of between 4.76 and 5.5 times yearly earnings, entirely irrespective of the lease term. This was said to be an indication that the franchisee was making a capital acquisition by the payment.

74 On appeal, the case has been put slightly more broadly. The appellants are saying, in effect, that it is a payment which has some effect on a future outgoing, or at least a potential future outgoing. Those future outgoings, if paid on a recurrent basis, would have been revenue hence the payment that substitutes for them is also revenue. But there is no principle that this will always be so. There is no principle that a payment that substitutes for future revenue outgoings or which compensates for them, or which more accurately in this case obviates or removes the need for them, must itself be revenue.

75 Also significantly, if the term, that is the duration, of the lease was irrelevant to the method of calculation of the payment, then any argument that the payment was in truth (as distinct from its description) a computation of prepayment of rent is extremely difficult to mount.

76 Both experts confirmed that MAL values stores at about five to five and a half times yearly earnings, such that the value of the Erina Fair II store was approximately $940,000 as a going concern. $465,000 was attributed to the value of the equipment and it followed that $475,000, simply being the difference between the business value and its equipment, was the figure described as prepaid rent.

77 Having calculated in this way the figure of $475,000, MAL then converts it by assessing that the equivalent of $475,000 would, if described as a rent prepayment, be in effect an increase in rent to 13.93%, and then, in this instance offers to reduce the rent back to 9.4% if the $475,000 is paid. The Commissioner contends that this payment, (following the principles in Sharpcan), was to obtain a more profitable business structure.

78 In our view, this assessment is correct for the reason that the taxpayer is offered an existing profitable business which he or she can take over, and he or she can either take it over at the 13.93% rent level or the 9.4 % rent level, but by paying $475,000 as a once and for all payment he or she receives the benefit of what is in reality a better version of the lease or a more profitable lease. Clearly, the FLL is a capital asset of the business. In fact, it is by far the most important capital asset. By comparison, in Sharpcan the GMEs assisted the profit-making capacity of the business by increasing revenue. The price for the GMEs in Sharpcan was held to be capital because it improved the capital structure of the business by way of intangible advantages and improved profit-making (see, for example, at [40]).

79 By the time the FLL is executed, there is no consideration of the higher rent. The taxpayer has, in effect, purchased the right to have the better lease with the lower rent.

80 As senior counsel for the Commissioner correctly submitted:

the taxpayer opted for which version of the rent – of the lease [he] wanted – there was never a time when [he was] obliged to pay the high rent. So [it is] very difficult to see how a payment to elect between a universe where you have a low rent and a universe where you have a high rent can operate as a prepayment of high rent that never becomes payable...

81 Further considerations supporting the analysis that the purpose of the upfront payment was to obtain a more profitable business structure rather than to pay rent upfront include the following. The method of calculation of the prepayments was the same across the different leases, even though the duration of the leases varied. This shows that the prepayments bore no relationship to the duration of the leases, and were therefore unconnected to the obligation to pay rent. Also, on renewal or extension of the lease no new prepayment would be payable, the rental obligation being calculated with reference to the lesser rental option that had been chosen on inception; and, on termination or surrender the prepayment would not be reduced pro rata.

82 The position is essentially the same with the Group Two restaurants. The obligation to pay higher rent never existed in the Group One restaurants and never took effect in the Group Two restaurants. The principal distinction between the Group One and Group Two restaurants is that MFT acquired the right to operate the Group Two restaurants at the higher percentage rent when the FLLs were granted, but was given the option to change the obligation to pay rent under the lease forming part of the FLL from the higher percentage rent to the lower percentage rent for the term with effect from handover. Exercising the option and making the upfront payment in respect of the Group Two restaurants altered the profit-making structure by making it more favourable as a result of the change to the obligation to pay rent. A change of this kind to the terms of a capital asset is an affair of capital: Tucker v Granada Motorway Services Ltd [1979] 2 All ER 801 per Lord Wilberforce (at 805) and per Lord Fraser of Tullybelton (at 811-812), cited with approval in Mount Isa Mines Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1992) [1992] HCA 62; 176 CLR 141 (at 150).

83 In addition to that objective analysis which is in itself conclusive on the issue of capital or revenue, Mr Mussalli knew that MAL’s method of calculation of the payments had nothing to do with the duration of the lease and therefore the amount of the savings. Rather, payments were simply computed by deducting the value of the equipment from the value of the restaurant, being five to five and a half times its yearly profit.

84 This process applied on seven separate occasions in the period from December 2005 to December 2011, with MFT entering into FLLs with MAL to takeover and operate a pre-existing McDonald’s restaurant for a specified term.

85 The primary judge was correct in finding that the upfront payments were of capital or were capital in nature, and not deductible by reason of s 8-1(2)(a) of the ITAA 1997, claimed over a 10 year period under s 82KZMD of Subdiv H of Div 3 of Part III of the ITAA 1936, including the years in dispute. That conclusion necessarily followed from the correct identification of the advantage sought by MFT in making the upfront payments. Irrespective of how the primary judge approached the task of identifying the advantage sought by MFT in making the upfront payments, her Honour correctly concluded that the payments were made for an enduring advantage in the form of a right to pay the lesser rent for the term of the FLL, and most likely longer. This gave MFT a preferable profit-making structure. Therefore, her Honour was correct to reject the appellants’ contention made below that the upfront payments were prepayments of rent. The payment, contrary to their description, were in truth never for prepayment of rent or any other deductible outgoing.