FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Degning v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 67

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Orders 3 and 4 of the Court made on 7 August 2018 be set aside, and in lieu thereof it be ordered that

(a) the decision of the respondent of 9 January 2018 cancelling the applicant’s visa be set aside; and

(b) the respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the application.

3. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 I have had the advantage of reading the reasons to be published by Thawley J.

2 I agree with his Honour’s reasons in relation to ground 1 of the notice of appeal. Prior to the coming into effect on 2 April 1984 of the Migration Amendment Act 1983 (Cth) (the 1983 Amendment Act), the statutory powers to deport people were based on either s 51(xxvii) “immigration and emigration” or s 51(xix) “naturalization and aliens”. One of the important distinctions between the two powers was that a person lost the status of an immigrant (and so ceased to be within the reach of any statutory power directed to immigrants and based on s 51(xxvii)) if that person had become absorbed into the Australian community as a member thereof: R v MacFarlane; Ex parte O’Flanagan and O’Kelly [1923] HCA 39; 32 CLR 518 at 583 (Starke J, contra Isaacs J at 555, with whom Rich J agreed at 578 that “once an immigrant always an immigrant”); Ex parte Walsh and Johnson; Re Yates [1925] HCA 53; 37 CLR 36 at 61–62 (Knox CJ, agreeing with Starke J in R v MacFarlane) and 138 (Starke J); R v Forbes; Ex parte Kwok Kwan Lee [1971] HCA 14; 124 CLR 168 at 172 (Barwick CJ, with whom McTiernan, Windeyer, Owen and Gibbs JJ agreed); and The Queen v Director General of Social Welfare (Vic); Ex parte Henry [1975] HCA 62; 133 CLR 369 at 372 (Barwick CJ), 373–374 (Gibbs J), 379–380 (Mason J, with whom McTiernan J agreed), and 383–384 (Jacobs J, with whom McTiernan J also agreed). See also in the Full Court of this Court Kuswardana v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1981) 35 ALR 186.

3 Upon the reconfiguration of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) by the 1983 Amendment Act as based on the distinction between citizen and non-citizen (based on the aliens power) Mr Degning became liable to the provisions of the Migration Act if he was a non-citizen. This in turn raised his status as an alien or not. If he was not an alien, he was not a non-citizen. By application of the majority of the High Court in Patterson; Ex parte Taylor [2001] HCA 51; 207 CLR 391 it would be concluded that he was, as a British subject, not an alien. By application of the majority of the High Court in Nolan v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs [1988] HCA 45, 165 CLR 178 (overruled by Re Patterson) it would be concluded that he was an alien. And by application of the majority of the High Court in Shaw v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2003] HCA 72; 218 CLR 28 (which distinguished Patterson and applied Nolan) it would also be concluded that he was an alien.

4 Mr Degning did not become the holder of any accrued right. He was an alien, no longer amenable to deportation as an immigrant, but liable (as he became) to be subjected to the laws of Australia that dealt with his status in this country by reference to being an alien, and by legislation a non-citizen.

5 As to ground 2 of the notice of appeal, the complexity brought about by Part VIIC of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) dealing with spent convictions and the exceptions thereto is evident from the reasons of Thawley J. If the Minister was not prevented from taking into account all of the convictions because of the operation of the exception in s 85ZZH(d) it can be concluded that the Minister has not drawn a factual conclusion or taken something into account that he was not legally entitled to conclude, or to take into account. That is, if Mr Degning was entitled to answer “NO” to the question about criminal convictions that were spent, to find that he displayed a disregard for the law in so answering, at least in relation to those offences would be an error. It would then be necessary to consider whether the error was jurisdictional: Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34; 359 ALR 1. I agree, however, with the reasons of Thawley J in relation to ground 2 of the notice of appeal. That, however, is not the end of the matter. There is ground 3 of the notice of appeal – the asserted lack of procedural fairness.

6 For a consideration of ground 3, one must move from the web of abstracted complexity of the legislative provisions discussed by Thawley J in relation to ground 2 and move to a more human context. As I said in SZRMQ v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2013] FCAFC 142; 219 FCR 212 at 215 [6]–[7]:

The requirements of procedural fairness are not generally apt for precise delineation. Some aspects can be reduced to a verbal expression of law. The test for apprehended bias is perhaps an example of that. The difficulty in precise formulation of many aspects of the requirements is that the informing norm and root of the principle is fairness: Kioa v West [1985] HCA 81; 159 CLR 550 at 583-585. Even in relation to the proper test for apprehended bias, however, the use of the fair-minded observer in the construct imports the norm of fairness: SZRUI v Minister for Immigration, Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship [2013] FCAFC 80 at [2].

Fairness is normative, evaluative, context specific and relative. As such, its assessment is sometimes imprecise in articulation and open to debate. Nevertheless, subject to any clear contrary statutory intention, fairness is an inhering requirement of the exercise of state power: Jarratt v Commissioner of Police for NSW [2005] HCA 50; 224 CLR 44 at 56-57 [26]; and SZRUI at [5].

7 Here there are two relevant points or periods of time to consider: the filling in, signing and handing over of the arrival card; and the opportunity Mr Degning had to put what he wanted to say about the cancellation of his visa.

8 As to the first period of time and the relevant events, these were within the knowledge of the Mr Degning. Did he direct his attention to the card or to the precise question? Did he fill it in and sign it, or did someone else fill it in and he sign it? Was he consciously appreciative that he was answering the card falsely at least in relation to recent convictions, if, arguably the provision concerned with spent convictions applied to some? What were the circumstances of the filling out, signing and handing over of those cards?

9 Given the inaccuracy of the answer, at least as to the recent convictions if one had some understanding (albeit inadequate by reference to the exception in s 85ZZH(d) of the Crimes Act) of Div 3 of Pt VIIC of the Crimes Act, only Mr Degning would be able to shed light on the circumstances of the filling out, signing and handing over of the arrival card if they were to be relevant to his visa cancellation.

10 These circumstances would only be relevant to the cancellation of his visa on character grounds (to use a general expression for the moment) if they displayed discreditable and dishonest behaviour. That is, if they revealed that Mr Degning deliberately, knowingly and dishonestly answered the question falsely.

11 If, on the other hand, the circumstances were such as not to warrant a conclusion of dishonesty it would be difficult to understand how they could be relevant to any decision that the Minister might make.

12 Thus, the question is whether in all the circumstances, Mr Degning was afforded procedural fairness. What I said in SZRMQ is to be understood in the light of what the Full Court said in Commissioner for Australian Capital Territory Revenue v Alphaone Pty Ltd (1994) 49 FCR 576 at 590–591 approved by the Court in SZBEL v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2006] HCA 63; 228 CLR 152 at 162 [32]. Applying these principles, Mr Degning was entitled to have his mind directed to the critical issues or facts on which the decision was likely to turn unless the recognition of the issue was, from the material with which he was provided, an obvious and natural conclusion to draw.

13 Nothing in Alphaone or SZBEL decontextualizes the enquiry. One should look at the whole of the circumstances including the documents given to Mr Degning to assess whether he had his mind directed to the critical issues or factors on which the decision was likely to turn and to be informed of the nature and content of relevant material. In that assessment, it is relevant to assess what is or is not an obvious or natural evaluation of the material which need not be the subject of particular attention being drawn. The ultimate touchstone is fairness.

14 The letter of the Department dated 29 December 2016 provided Mr Degning with information concerning a subject matter of the utmost seriousness to him: the cancellation of his visa, and, consequentially, his right to live in Australia. The content of the letter and its attachments should therefore have been seen by Mr Degning as important. The context, therefore, dictated that Mr Degning take great care and attention in reading and understanding the documents. The Minister could, and should, have expected that.

15 Section 501 was provided to him in full. It is a section which covers six pages in the authorised compilation. It is as follows:

Refusal or cancellation of visa on character grounds

Decision of Minister or delegate—natural justice applies

(1) The Minister may refuse to grant a visa to a person if the person does not satisfy the Minister that the person passes the character test.

(2) The Minister may cancel a visa that has been granted to a person if:

(a) the Minister reasonably suspects that the person does not pass the character test; and

(b) the person does not satisfy the Minister that the person passes the character test.

Decision of Minister—natural justice does not apply

(3) The Minister may:

(a) refuse to grant a visa to a person; or

(b) cancel a visa that has been granted to a person;

if:

(c) the Minister reasonably suspects that the person does not pass the character test; and

(d) the Minister is satisfied that the refusal or cancellation is in the national interest.

(3A) The Minister must cancel a visa that has been granted to a person if:

(a) the Minister is satisfied that the person does not pass the character test because of the operation of:

(i) paragraph (6)(a) (substantial criminal record), on the basis of paragraph (7)(a), (b) or (c); or

(ii) paragraph (6)(e) (sexually based offences involving a child); and

(b) the person is serving a sentence of imprisonment, on a full-time basis in a custodial institution, for an offence against a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory.

(3B) Subsection (3A) does not limit subsections (2) and (3).

(4) The power under subsection (3) may only be exercised by the Minister personally.

(5) The rules of natural justice, and the code of procedure set out in Subdivision AB of Division 3 of Part 2, do not apply to a decision under subsection (3) or (3A).

Character test.

(6) For the purposes of this section, a person does not pass the character test if:

(a) the person has a substantial criminal record (as defined by subsection (7)); or

(aa) the person has been convicted of an offence that was committed:

(i) while the person was in immigration detention; or

(ii) during an escape by the person from immigration detention; or

(iii) after the person escaped from immigration detention but before the person was taken into immigration detention again; or

(ab) the person has been convicted of an offence against section 197A; or

(b) the Minister reasonably suspects:

(i) that the person has been or is a member of a group or organisation, or has had or has an association with a group, organisation or person; and

(ii) that the group, organisation or person has been or is involved in criminal conduct; or

(ba) the Minister reasonably suspects that the person has been or is involved in conduct constituting one or more of the following:

(i) an offence under one or more of sections 233A to 234A (people smuggling);

(ii) an offence of trafficking in persons;

(iii) the crime of genocide, a crime against humanity, a war crime, a crime involving torture or slavery or a crime that is otherwise of serious international concern;

whether or not the person, or another person, has been convicted of an offence constituted by the conduct; or

(c) having regard to either or both of the following:

(i) the person’s past and present criminal conduct;

(ii) the person’s past and present general conduct;

the person is not of good character; or

(d) in the event the person were allowed to enter or to remain in Australia, there is a risk that the person would:

(i) engage in criminal conduct in Australia; or

(ii) harass, molest, intimidate or stalk another person in Australia; or

(iii) vilify a segment of the Australian community; or

(iv) incite discord in the Australian community or in a segment of that community; or

(v) represent a danger to the Australian community or to a segment of that community, whether by way of being liable to become involved in activities that are disruptive to, or in violence threatening harm to, that community or segment, or in any other way; or

(e) a court in Australia or a foreign country has:

(i) convicted the person of one or more sexually based offences involving a child; or

(ii) found the person guilty of such an offence, or found a charge against the person proved for such an offence, even if the person was discharged without a conviction; or

(f) the person has, in Australia or a foreign country, been charged with or indicted for one or more of the following:

(i) the crime of genocide;

(ii) a crime against humanity;

(iii) a war crime;

(iv) a crime involving torture or slavery;

(v) a crime that is otherwise of serious international concern; or

(g) the person has been assessed by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation to be directly or indirectly a risk to security (within the meaning of section 4 of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979); or

(h) an Interpol notice in relation to the person, from which it is reasonable to infer that the person would present a risk to the Australian community or a segment of that community, is in force.

Otherwise, the person passes the character test.

Substantial criminal record

(7) For the purposes of the character test, a person has a substantial criminal record if:

(a) the person has been sentenced to death; or

(b) the person has been sentenced to imprisonment for life; or

(c) the person has been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 12 months or more; or

(d) the person has been sentenced to 2 or more terms of imprisonment, where the total of those terms is 12 months or more; or

(e) the person has been acquitted of an offence on the grounds of unsoundness of mind or insanity, and as a result the person has been detained in a facility or institution; or

(f) the person has:

(i) been found by a court to not be fit to plead, in relation to an offence; and

(ii) the court has nonetheless found that on the evidence available the person committed the offence; and

(iii) as a result, the person has been detained in a facility or institution.

Concurrent sentences

(7A) For the purposes of the character test, if a person has been sentenced to 2 or more terms of imprisonment to be served concurrently (whether in whole or in part), the whole of each term is to be counted in working out the total of the terms.

Periodic detention

(8) For the purposes of the character test, if a person has been sentenced to periodic detention, the person’s term of imprisonment is taken to be equal to the number of days the person is required under that sentence to spend in detention.

Residential schemes or programs

(9) For the purposes of the character test, if a person has been convicted of an offence and the court orders the person to participate in:

(a) a residential drug rehabilitation scheme; or

(b) a residential program for the mentally ill;

the person is taken to have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment equal to the number of days the person is required to participate in the scheme or program.

Pardons etc.

(10) For the purposes of the character test, a sentence imposed on a person, or the conviction of a person for an offence, is to be disregarded if:

(a) the conviction concerned has been quashed or otherwise nullified; or

(b) both:

(i) the person has been pardoned in relation to the conviction concerned; and

(ii) the effect of that pardon is that the person is taken never to have been convicted of the offence.

Conduct amounting to harassment or molestation

(11) For the purposes of the character test, conduct may amount to harassment or molestation of a person even though:

(a) it does not involve violence, or threatened violence, to the person; or

(b) it consists only of damage, or threatened damage, to property belonging to, in the possession of, or used by, the person.

Definitions

(12) In this section:

court includes a court martial or similar military tribunal.

imprisonment includes any form of punitive detention in a facility or institution.

sentence includes any form of determination of the punishment for an offence.

16 The letter of 29 December squarely put Mr Degning on notice that the Department considered that because of his “substantial criminal record” within the meaning of s 501(7) he did not pass the character test. That statement in the letter directed Mr Degning’s attention expressly to ss 501(6)(a) and (7), as the basis (and the only expressed basis) for the possible failure to pass the character test. Mr Degning was not told (because it was not the case) that the basis of the consideration of the character test was s 501(6)(c)(i) or (ii), in particular (ii). The question of passing or not passing the character test was based on ss 501(6)(a) and 501(7), only.

17 In this context the letter invited comment from him as follows:

Before the decision-maker considers whether to cancel your visa, you have an opportunity to comment or provide information on whether you pass the character test and, should the decision-maker reasonably suspect that you do not, on whether the decision-maker should exercise his or her discretion to cancel your visa

18 The documents enclosed included the National Police Certificate which contained information about his convictions that included a sentence to a term of imprisonment over 12 months. Thus it was plain to Mr Degning that he must address the second question under the invitation to comment: whether (given a failure to pass the character test for s 501(6)(a) because of the terms of s 501(7)) the decision-maker should nevertheless exercise a discretion not to cancel the visa.

19 Mr Degning also received three passenger cards, which were signed by him and in which the answer to a question whether he had criminal convictions was “no”, and Ministerial Direction 65. Mr Degning was told that if the Minister made the decision he was not bound to follow Direction 65, though a delegate was if a delegate made the decision. Reference to the documents enclosed was preceded by a paragraph that read:

The following documents are also enclosed. The documents consist of information that is held by the department, which the decision-maker may rely on to decide whether you pass the character test; and if not, whether your visa should be cancelled.

20 Mr Degning would, if he had thought about it, have been puzzled why the cards and the information in them could be relevant to the character test by reference to s 501(6)(a) and (7). He either had a substantial criminal record or he did not. As to the question “whether your visa should be cancelled” if the character test was not passed, he had Direction 65.

21 Direction 65 is a 33 page document. Not all of it applied to Mr Degning’s position. But he was exhorted by the letter to read it carefully. The document is extensive and detailed. Under “General Guidance” in Section 1 by way of preliminary matters it was stated that the “principles below are of critical importance”. These principles in para 6.3 were seven in number:

(1) Australia has a sovereign right to determine whether non-citizens who are of character concern are allowed to enter and/or remain in Australia. Being able to come to or remain in Australia is a privilege Australia confers on non-citizens in the expectation that they are, and have been, law-abiding, will respect important institutions, such as Australia's law enforcement framework, and will not cause or threaten harm to individuals or the Australian community.

(2) The Australian community expects that the Australian Government can and should refuse entry to non-citizens, or cancel their visas, if they commit serious crimes in Australia or elsewhere.

(3) A non-citizen who has committed a serious crime, including of a violent or sexual nature, and particularly against vulnerable members of the community such as minors, the elderly or disabled, should generally expect to be denied the privilege of coming to, or to forfeit the privilege of staying in, Australia.

(4) In some circumstances, criminal offending or other conduct, and the harm that would be caused if it were to be repeated, may be so serious, that any risk of similar conduct in the future is unacceptable. In these circumstances, even other strong countervailing considerations may be insufficient to justify not cancelling or refusing the visa.

(5) Australia has a low tolerance of any criminal or other serious conduct by people who have been participating in, and contributing to, the Australian community only for a short period of time. However, Australia may afford a higher level of tolerance of criminal or other serious conduct in relation to a non-citizen who has lived in the Australian community for most of their life, or from a very young age.

(6) Australia has a low tolerance of any criminal or other serious conduct by visa applicants or those holding a limited stay visa, reflecting that there should be no expectation that such people should be allowed to come to, or remain permanently in, Australia.

(7) The length of time a non-citizen has been making a positive contribution to the Australian community, and the consequences of a visa refusal or cancellation for minor children and other immediate family members in Australia, are considerations in the context of determining whether that non-citizen's visa should be cancelled, or their visa application refused.

22 Relevant for someone in Mr Degning’s position was Part A of Section 2 dealing with cancellation of visas. It is over five pages long. I do not set it out in detail but it addresses in para 9 three primary considerations:

(a) protection of the Australian community from criminal and other serious conduct;

(b) the best interests of minors in Australia; and

(c) the expectations of the Australian community.

23 Some three pages are devoted to these topics. A strong theme is the seriousness of the criminal conduct, and the risk of further offending.

24 Paragraph 10 then deals with other considerations of which five are listed:

(a) international non-refoulement obligations;

(b) strength, nature and duration of ties;

(c) impact on Australian business;

(d) impact on victims;

(e) extent of impediments if removed.

25 There is no part of paras 9 or 10 to which the content of the passenger arrival cards and any inaccurate aspect of their filling out (deliberate or innocent) could reasonably be seen to be relevant.

26 In dealing with risk to the Australian community the direction states the following at para 9.1.2:

(1) In considering whether the non-citizen represents an unacceptable risk of harm to individuals, groups or institutions in the Australian community, decision-makers should have regard to the principle that the Australian community's tolerance for any risk of future harm becomes lower as the seriousness of the potential harm increases. Some conduct and the harm that would be caused if it were to be repeated, is so serious that any risk that it may be repeated may be unacceptable.

(2) In considering the risk to the Australian community, decision-makers must have regard to, cumulatively:

a) The nature of the harm to individuals or the Australian community should the non-citizen engage in further criminal or other serious conduct; and

b) The likelihood of the non-citizen engaging in further criminal or other serious conduct, taking into account:

i. information and evidence on the risk of the non-citizen re-offending; and

ii. evidence of rehabilitation achieved by the time of the decision, giving weight to time spent in the community since their most recent offence (noting that decisions should not be delayed in order for rehabilitative courses to be undertaken).

27 Parts B and C were and are not relevant to Mr Degning as they concern the refusal of an application for a visa and the discretion to revoke mandatory cancellation of a visa.

28 Annexure A provides “direction” on the application of the character test. It is nine pages long. It is important to recall that the covering letter told Mr Degning that it was s 501(6)(a) and (7) which concerned him. The section in Annexure A on s 501(6)(a) was directed to the activating circumstances in s 501(7).

29 There was no section of Direction 65 that dealt with any particular matters in the exercise of the discretion to cancel or not cancel the visa should the character test not be passed. This is both understandable and important. There was nothing in the Direction from which Mr Degning could take that how he had otherwise behaved generally or in relation to the passenger cards might be relevant to the decision. The whole focus of the character test embodied in s 501(6)(a) and (7) and the principles in the Direction was the criminality he had engaged in, the protection of the public and the risk of re-offending.

30 The character test can also not be passed by reference to more general considerations, such as s 501(6)(c)(i) or (ii). Paragraph 5 of Annexure A gives direction as to the application of s 501(6)(c)(i) and (ii), over three pages. As to past and present criminal and general conduct the following appears:

5.1 Past and present criminal conduct

(1) In considering whether a person is not of good character on the basis of past or present criminal conduct, the following factors are to be considered:

a) The nature and severity of the criminal conduct;

b) The frequency of the person’s offending and whether there is any trend of increasing seriousness;

c) The cumulative effect of repeated offending;

d) Any circumstances surrounding the criminal conduct which may explain the conduct such as may be evident from judges’ comments, parole reports and similar authoritative documents; and

e) The conduct of the person since their most recent offence, including:

i. The length of time since the person last engaged in criminal conduct;

ii. Any evidence of recidivism or continuing association with criminals;

iii. Any pattern of similar criminal conduct;

iv. Any pattern of continued or blatant disregard or contempt for the law; and

v. Any conduct which may indicate character reform.

5.2 Past and present general conduct

(1) The past and present general conduct provision allows a broader view of a person's character where convictions may not have been recorded or where the person's conduct may not have constituted a criminal offence.

a) In considering whether the person is not of good character, the relevant circumstances of the particular case are to be taken into account, including evidence of rehabilitation and any relevant periods of good conduct.

(2) The following factors may also be considered in determining whether a person is not of good character:

a) Whether the person has been involved in activities indicating contempt or disregard for the law or for human rights. This includes, but is not limited to:

i. Involvement in activities such as terrorist activity, activities in relation to trafficking or possession of trafficable quantities of proscribed substances, political extremism, extortion, fraud; or

ii. A history of serious breaches of immigration law, breach of visa conditions or visa overstay in Australia or another country; or

iii. Involvement in war crimes or crimes against humanity;

b) whether the person has been removed or deported from Australia or another country and the circumstances that led to the removal/deportation; or

c) whether the person has been:

i. dishonourably discharged; or

ii. discharged prematurely;

from the armed forces of another country as the result of disciplinary action in circumstances, or because of conduct that, in Australia would be regarded as serious.

(3) Where a person is in Australia and charges have been brought against that person in a jurisdiction other than an Australian jurisdiction, and those charges will not be resolved in absentia, the conduct that is the subject of those charges may be considered in the context of its impact on the person’s overall character.

(Emphasis added.)

31 In para 6.3 of Annexure A dealing with s 501(6)(d)(iii), (iv) and (v) there is a reference to “disregard for law and order” as follows:

6.3 Risk of vilifying a segment of the community, of inciting discord or of representing a danger through involvement in disruptive and/or violent activities (section 501(6)(d)(iii), (iv) and (v))

(1) In deciding whether a person does not pass the character test under section 501(6)(d)(iii), (iv) or (v) of the Act, factors to be considered include, but are not limited to, evidence that the person:

a) Would hold or advocate extremist views such as a belief in the use of violence as a legitimate means of political expression;

b) Would vilify a part of the community;

c) has a record of encouraging disregard for law and order;

Note: For example, in the course of addressing public rallies.

d) has engaged or threatens to engage in conduct likely to be incompatible with the smooth operation of a multicultural society;

Note: For example, advocating that particular ethnic groups should adopt political, social or religious values well outside those generally acceptable in Australian society, and which, if adopted or practised, might lead to discord within those groups or between those groups and other segments of Australian society.

e) participates in, or is active in promotion of, politically motivated violence or criminal violence and/or is likely to propagate or encourage such action in Australia;

f) is likely to provoke civil unrest in Australia because of the conjunction of the person’s intended activities and proposed timing of their presence in Australia with those of another individual, group or organisation holding opposing views.

…

(2) The operation of section 501(6)(d)(iii), (iv) and (v) of the Act must be balanced against Australia’s well established tradition of free expression. The grounds in these sub-paragraphs are not intended to provide a charter for denying entry or continued stay to persons merely because they hold and are likely to express unpopular opinions. However, where these opinions may attract strong expressions of disagreement and condemnation from the Australian community, the current views of the community will be a consideration in terms of assessing the extent to which particular activities or opinions are likely to cause discord or unrest.

(Emphasis added.)

32 The highlighted portions above are the only places in the whole of Direction 65 that refer to contempt or disregard for the law of some kind or degree as a relevant factor. Such references do not appear in any other section of the Direction.

33 The incoming passenger cards came to be relevant to the Minister in his consideration of risks to the Australian community, which was dealt with at paras 24–37 as follows:

24 I have considered whether Mr DEGNING poses a risk to the Australian community through reoffending by having regard to any mitigating or causal factors in his offending, and giving consideration to the steps Mr DEGNING has undertaken to reform and address his behavior. I have also taken into account Mr DEGNING’s overall conduct and his insight into the offending.

25 I note that Mr DEGNING has not made any representations that explain his sexual offending. However, I note from the sentencing remarks of 24 July 2013, that Mr DEGNING was estranged from his wife at the time of his offending. I also have considered Mr DEGNING’s representations that he is definitely not a sexual predator and that being sentenced for his sexual offending has changed his life.

26 I note from the NSW Police Facts Sheet dated 27 June 2015 that Mr DEGNING was temporarily separated from his wife at the time of his 2015 drink driving offence, with a pre-sentence report dated 21 September 2015, included that they had since reconciled.

27 I have given regard to Christine Ellison’ letter of 17 July 2015 that Mr DEGNING was under enormous stress during the time of the 2015 drink driving offence. Mr DEGNING’s daughter who was 28 weeks pregnant at the time was admitted to hospital with pre-eclampsia and his father with renal failure. Ms Ellison believed that these factors may have contributed to Mr DEGNING’s drink driving offending.

28 I accept family issues may have played a part in Mr DEGNING’s drink driving offence of 2015.

29 I note Mr DEGNING’s bond conditions required him to attend sober driving program. I have taken into account Mr DEGNING’s representations that he has completed two drink driving courses. I find Mr DEGNING’s participation in these courses will assist him in refraining from reoffending.

30 I have taken into account Mr DEGNING’s representation that he has a horrible criminal record and one of which he is ashamed. I also acknowledged that Mr DEGNING pleaded guilty to his sexual offending. I note this shows some level of remorse and insight by Mr DEGNING into his offending indicative of a lower likelihood of him reoffending.

31 I note from Christine Ellison’s letter that Mr DEGNING is extremely remorseful and upset about his drink driving offence. Ms Ellison believes that Mr DEGNING is sorry for what he has done.

32 I have also considered Mr DEGNING’s representation that he is now 56 years old and much wiser and has promised his wife, himself and the departmental decision maker that he will not reoffend. However, I also take into account that Mr DEGNING was 54 years old at the time of his most recent driving offence and that his criminal history shows that despite some periods of years with no convictions, he continued to variously offend, despite court dispositions, including sentences of imprisonment in 1982, 1983 and 2013 and licence disqualifications.

33 I note Mr DEGNING failed to declare his criminal convictions on his Incoming Passenger Cards dated 4 January 2004, 20 April 2004 and 02 March 2006, and I consider this indicative of a further disregard of the law.

34 I note from the sentencing remarks of 24 July 2013 that the Judge was of the view that Mr DENGING (sic) was unlikely to reoffend in a similar way because of his previous record, the fact that Mr DEGNING had not come into notice since being charged on 7 October 2009, and the shame and embarrassment of Mr DEGNING’s offending has caused.

35 Notwithstanding the Judge’s observation, I note that Mr DEGNING’s sexual offending in 2009 was when he was aged 48 years of age and involved him having taken advantage of a person with a cognitive impairment who was therefore vulnerable.

36 Overall, I find there is a risk, albeit low, that MR DEGNING will reoffend in a similar way.

37 If Mr DEGNING did engage in further criminal conduct of a sexual nature, it could result in conduct that could cause psychological and/or physical harm to a member or members of the Australian community. If Mr DEGNING engages in further driving offences it could place members of the community at risk of physical injury.

(Emphasis added.)

34 The use by the Minister of the passenger cards was directed to the risk of re-offending. That risk was found to be low, but sufficient to play an important part in the decision. The declarations on the cards could only be relevant to reveal a further disregard for the law if done knowingly and dishonestly.

35 The argument that it was irrational or illogical to use the false declarations as relevant to the risk of re-offending was rejected by the primary judge and not agitated on appeal. Whilst that forensic decision can be accepted as sound, it does not deny the proposition that the relevance of the form of the passenger cards, the circumstances of their being filled out, signed and handed over to the risk of re-offending in relation to crimes for which he received a sentence of over 12 months, or indeed for any of the crimes for which he had been convicted, was to anyone receiving and reading this material somewhat opaque. The cards may have raised a question that somehow the inaccuracy of the cards was to be considered. But, it is neither obvious nor clear that this would somehow go to what appeared from Direction 65 to be central – the protection of the Australian community from the re-offending in relation to a sexual offence: see in particular [33], [36] and [37] of the decision.

36 Mr Degning was not told that his general conduct was an issue; or that his dishonesty in relation to the passenger cards was an issue, and how it was an issue. Rather, he was told that his serious criminal conduct was through: s 501(6)(a) and (7), and the risk of re-offending. The relationship of the question of the falsity or inaccuracy of the cards to the risk of re-offending in relation to a sexual offence was opaque to say the least. If an assertion of conscious disregard for the law, through some dishonest act of concealment of the offence, was to be considered in relation to this decision, and particularly in relation to the risk of re-offending, Mr Degning was entitled to have the issue drawn to his attention. The fact that the Minister was not bound by Direction does not take the matter any further.

37 I do not consider that this was a peripheral issue. The risk of re-offending was the critical issue; it was accepted to be low; and this factor was directly relevant to that, in the thinking of the Minister reflected in the reasons.

38 There was in my view a failure to afford Mr Degning procedural fairness. It was, in my view, unfair not to direct Mr Degning to this issue. The common law requirement of procedural fairness or natural justice is rooted in the common law’s inhering demand for fairness in the way power is exercised. Relief will ordinarily follow a denial of procedural fairness: Re Refugee Review Tribunal; Ex parte Aala [2000] HCA 57; 204 CLR 82 at 89 [5] (Gleeson CJ), 101 [41] (Gaudron and Gummow JJ), 143–144 [171] (Hayne J), 132–136 [135]–[144] (Kirby J), 156–157 [218] (Callinan J). That does not mean that relief is not discretionary: Aala. But the relief is usual because a finding of an absence of procedural fairness is based on the procedure being unfair. An “arid and technical” approach to unfairness and approach to unfairness not based on the practical nature of fairness is to be disapproved: Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs; Ex parte Lam [2003] HCA 6; 214 CLR 1 at 9 [25] and 12–13 [34] (Gleeson CJ).

39 Whilst it is necessary for the applicant to show that the process has fallen short of a standard of fairness in all the circumstances, it is not necessarily the case that evidence must be led about what the applicant would have done had the procedure been fair. Here for instance, I see no justification for concluding that Mr Degning had to prove that he did not understand that the passenger cards were related to a proposition that he had a disregard for the law and that that was relevant to the question whether he posed a risk of re-offending for sexual offences. Given the gravity of the consequence of the decision for him, and the nature of the representations that he did make, I would infer that he would have said whatever he could have said about the cards, even, if it be the case, accepting some dishonesty. Human experience and plain common sense tells one that he would have addressed it. There is no basis to think that it could have been some tactical decision. Being prepared to draw the inference that Mr Degning did not understand the issue for which the passenger cards were to be or were used, I am persuaded that the failure to afford him procedural fairness denied him an opportunity to put submissions on a topic of relevance to the Minister’s consideration. There is no reason to think that this could not have made a difference to such a difficult decision, and one where there was accepted to be a low risk of re-offending. I do not consider that Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA [2019] HCA 3; 93 ALJR 252 requires any different conclusion.

40 I would uphold ground 3, allow the appeal and set aside the decision of the Minister.

41 I certify that the preceding forty (40) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

COLLIER J:

41 I have had the benefit of reading in draft the judgments of the Chief Justice and Justice Thawley, and am very grateful for the opportunity to do so.

42 I respectfully adopt Justice Thawley’s summary of the background facts and his Honour’s reasoning in respect of grounds of appeal 1 and 2. However in a case where the consequences of the Minister’s decision are of the utmost gravity for an appellant, the requirement on the Minister to accord the appellant procedural fairness is critical: Commissioner for Australian Capital Territory Revenue v Alphaone Pty Ltd (1994) 49 FCR 576 at 591–592, Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2003] HCA 56; 216 CLR 212 at [21]–[22]. I do not consider that the relevance of the inclusion of the passenger cards was plain in a context where Mr Degning was told that the proposed cancellation of his visa related to his history of serious criminal conduct.

43 Like the Chief Justice I am satisfied that the circumstances of the case evince a failure to afford Mr Degning procedural fairness.

44 The appeal should be allowed on the basis of the third ground of appeal, and the decision of the Minister should be set aside.

45 I certify that the preceding four (4) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Collier. |

Associate:

Dated: 30 April 2019

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THAWLEY J:

OVERVIEW

45 Mr Degning is a British citizen who migrated from Britain at the age of 7 years, arriving in Australia in June 1968. He has lived in Australia for 50 years. He has close ties to Australia including his wife of 37 years, his two adult daughters, their three children, his father, two sisters, a brother and five nieces. He also has a significant number of criminal convictions.

46 On 9 January 2018, the Minister for Home Affairs cancelled Mr Degning’s Class BF Transitional (Permanent) Visa under s 501(2) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). That decision was made on the basis that: (a) the Minister reasonably suspected that Mr Degning did not pass the character test, by reason of his having a substantial criminal record (s 501(6)(a), (7)); and (b) Mr Degning had not satisfied the Minister that he did pass that test.

47 Mr Degning sought to quash that decision in judicial review proceedings brought in this Court. The primary judge dismissed those proceedings on 7 August 2018. Mr Degning appeals from the primary judge’s orders.

48 The precise terms of the grounds of appeal are set out below. In summary, they were:

(1) first, the Minister was not authorised by s 501(2) to cancel the appellant’s visa because the relevant provision did not override the appellant’s right to remain indefinitely in Australia, that right having accrued before introduction of the provision;

(2) secondly, there was no basis upon which to conclude, as the Minister did, that Mr Degning disregarded the law by stating on Incoming Passenger Cards that he had no criminal convictions and declaring that the answers he had given were truthful; and

(3) thirdly, if there were such a basis for the Minister’s conclusion, Mr Degning was denied procedural fairness by not being put on notice of that conclusion, which was not obvious from the terms of the Incoming Passenger Cards in the context in which they were provided to him.

49 For the reasons which follow, each ground of appeal must be rejected.

BACKGROUND

Mr Degning’s entry permit and transitional (permanent) visa

50 Mr Degning came to Australia as a seven year old child in June 1968 with his parents, two sisters and brother. At the time, Part II of the Migration Act dealt with “Immigration and Deportation”.

51 An “entry permit” was generally required for an immigrant to enter Australia lawfully: s 6. An immigrant was defined in s 5(1) as follows:

“immigrant” includes a person intending to enter, or who has entered, Australia for a temporary stay only, where he would be an immigrant if he intended to enter, or had entered, Australia for the purpose of staying permanently …

52 Section 6 included:

(1) An immigrant who, not being the holder of an entry permit that is in force, enters Australia thereupon becomes a prohibited immigrant.

(2) An officer may, in accordance with this section and at the request or with the consent of an immigrant, grant to the immigrant an entry permit.

(3) An entry permit shall be in a form approved by the Minister and shall be expressed to permit the person to whom it is granted to enter Australia or to remain in Australia or both.

…

(6) An entry permit that is intended to operate as a temporary entry permit shall be expressed to authorize [sic] the person to whom it relates to remain in Australia for a specified period only, and such a permit may be granted subject to conditions.

…

(8) A child under the age of sixteen years who enters Australia in the company of, and whose name is included in the passport of, or any other document of identity of, a parent of the child shall be deemed to be included in any entry permit granted to that parent before the entry of that parent and written on that passport or other document of identity, unless the contrary is stated in the entry permit.

53 Section 6(1) uses the term “holder”, which was defined in s 5(1) in the following way:

“the holder”, in relation to an entry permit, means the person to whom the entry permit was granted or a person who is deemed to be included in the entry permit.

54 A child under the age of sixteen who entered Australia with their parent was “deemed to be included in any entry permit granted to” the child’s parent: s 6(8). An entry permit was permanent unless expressed to be temporary: s 6(6).

55 In summary, the operation of these provisions so far as concerned Mr Degning was that he was not a prohibited immigrant under s 6(1) because he was “the holder” of an entry permit by reason of the fact that he was deemed by s 6(8) to be included in the entry permit granted to one of his parents. The entry permit was permanent.

56 Section 12 permitted deportation of an “alien” convicted of certain crimes. Section 14(1) permitted deportation of an “alien” if it appeared to the Minister that their conduct had been such that they should not be allowed to remain in Australia. British subjects were not included in the definition of “alien” in s 5(1):

“alien” means a person who is not –

(a) a British subject;

(b) an Irish citizen; or

(c) a protected person.

57 Accordingly, immigrants who were British subjects could not be deported under s 12 or s 14(1).

58 British subjects could, however, be deported pursuant to s 13 or s 14(2):

(1) Section 13 permitted deportation of an immigrant who had been convicted of certain offences committed within five years of entry into Australia or who was, within five years of entry into Australia, an inmate of a mental hospital or public charitable institution.

(2) Section 14(2) permitted deportation of an immigrant who entered Australia not more than five years previously if it appeared to the Minister that their conduct had been such that they should not be allowed to remain in Australia or they were a person advocating, amongst other things, the overthrow by force of the Commonwealth.

59 The Migration Reform Act 1992 (Cth) amended the Migration Act to replace the entry permit system with the current visa system. Ultimately, the visa system commenced from 1 September 1994 – see: s 2(3) of the Reform Act 1992; s 5 of the Migration Laws Amendment Act 1993 (Cth).

60 Regulation 4(1) of the Migration Reform (Transitional Provisions) Regulations 1994 (Cth) provided as follows:

Subject to regulation 5, if, immediately before 1 September 1994, a non-citizen was in Australia as the holder of a permanent entry permit, that entry permit continues in effect on and after 1 September 1994 as a transitional (permanent) visa that permits the holder to remain indefinitely in Australia.

61 Immediately before 1 September 1994, Mr Degning was the holder of a permanent entry permit: s 6, read with the definition of “the holder” in s 5(1). Pursuant to reg 4(1), the relevant entry permit continued in effect as a transitional (permanent) visa. That was the visa which the Minister ultimately cancelled.

Criminal convictions and incoming passenger cards

62 Mr Degning received his first conviction, “assault female”, on 24 May 1977. That was the first of a number of convictions the last of which was on 21 September 2015.

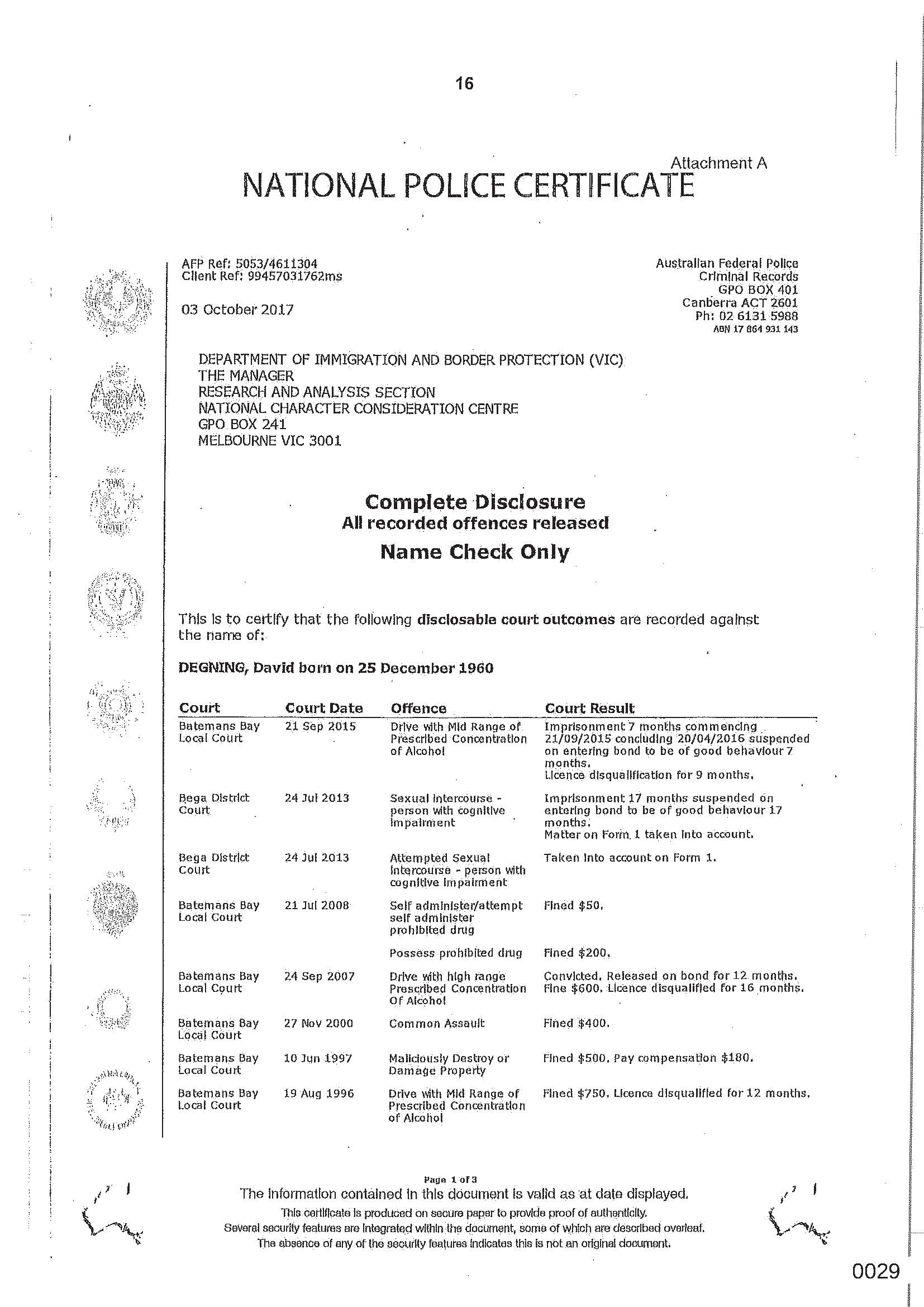

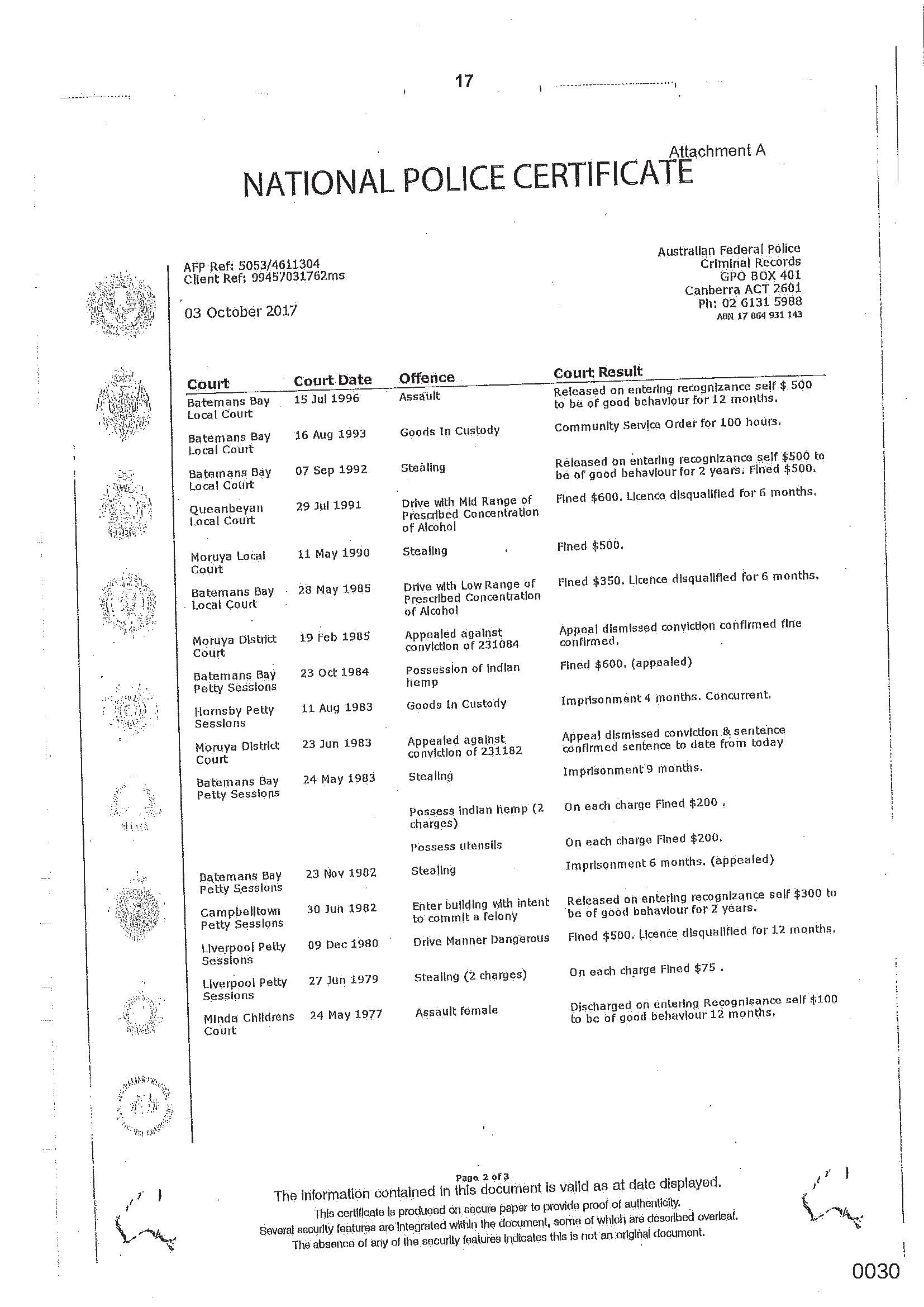

63 The criminal convictions were set out in a National Police Certificate dated 3 October 2017, which is annexed to these reasons as Annexure A. The Minister had provided this certificate to Mr Degning in a letter dated 5 October 2017. He had earlier given Mr Degning a notice dated 29 December 2016 which contained a National Police Certificate dated 14 January 2016 which had contained an error. Nothing turns on the error.

64 Mr Degning also completed three Incoming Passenger Cards, dated 4 January 2004, 20 April 2004 and 2 March 2006. Each card answered “No” to the question “Do you have any criminal conviction/s?”.

65 Each card contained a declaration, signed and dated by Mr Degning which stated:

The information I have given is true, correct and complete. I understand failure to answer any questions may have serious consequences.

66 Each form also stated:

Information sought on this form is required to administer immigration, customs, quarantine, statistical, health, wildlife and currency laws of Australia and its collection is authorised by legislation. It will be disclosed only to agencies administering these areas and those entitled to receive it under Australian law. The leaflet ‘Safeguarding your personal information’ is available at Australian ports and airports.

67 At the time of signing each of the Incoming Passenger Cards, Mr Degning had in fact been convicted on 21 occasions between 24 May 1977 and 27 November 2000, as set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

68 As is explained below, all but the four most recent of those convictions was “spent” at the time of signing the Incoming Passenger Cards. By reason of s 85ZZH(c) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), this Court is not prohibited by s 85ZW(b) of the Crimes Act from disclosing the spent convictions, assuming s 85ZW(b) otherwise applies.

Notice of cancellation and Mr Degning’s comments

69 A notice dated 29 December 2016 of the Minister’s intention to consider cancellation of Mr Degning’s visa under s 501(2) of the Act was sent to Mr Degning by registered post. The notice set out its purpose and invited comment from Mr Degning. It recorded that the Minister (or delegate) might cancel Mr Degning’s visa if: (a) the decision-maker reasonably suspected Mr Degning did not pass the character test; and (b) Mr Degning did not satisfy the decision-maker that he did pass that test.

70 At the end of the letter, various enclosures were identified:

Enclosures:

• Personal Circumstances Form

• Acknowledgement of Notice under Section 501 and Authority to Release Information

• Frequently Asked Questions

• Advice by a migration agent/exempt person of providing immigration assistance (Form 956)

• Appointment or withdrawal of an authorised recipient (Form 956A)

• Information about legal aid assistance in Australia

• Attachment 1: character related legislation of the Migration Act and Migration Regulations

• Attachment 2: general information

The following documents are also enclosed. The documents consist of information that is held by the department, which the decision-maker may rely on to decide whether you pass the character test; and if not, whether your visa should be cancelled.

• Ministerial Direction 65

• National Police Certificate dated 14 January 2016 is enclosed

• Court Attendance and New South Wales Police Facts Sheet printed on 13 July 2012

• Incoming Passenger Cards dated 04 January 2004, 20 April 2004 and 02 March 2006

71 As to Direction 65 – Visa Refusal and Cancellation under s 501, the notice advised that it should be read carefully, and stated:

(1) if the decision-maker was a delegate of the Minister, they must follow the direction;

(2) if the Minister made the decision personally, the direction provided a broad indication of the types of issue he might consider or take into account.

72 Further letters were sent to Mr Degning providing updated information, including letters dated 4 May 2017, 25 July 2017 and 5 October 2017. As noted earlier, the letter of 5 October 2017 attached a National Police Certificate dated 3 October 2017. Nothing in the appeal turns on these letters.

73 Amongst other material, Mr Degning provided to the Minister a “Personal Circumstances Form” dated 16 January 2017 and representations dated 30 May 2017, undated representations received 21 August 2017 and representations dated 25 October 2017.

The Minister’s decision

74 On 9 January 2018, the Minister exercised his discretion under s 501(2) of the Migration Act to cancel Mr Degning’s visa. He had regard to a range of matters in reaching his decision. He considered Mr Degning’s criminal conduct, including:

(1) On 7 October 2009, Mr Degning was arrested for a sexual offence. He was convicted of “sexual intercourse – person with cognitive impairment” in the District Court of New South Wales on 24 July 2013 and sentenced to 17 months imprisonment, which was suspended upon entering a good behaviour bond for 17 months: Minister’s reasons (“M”) at [12] to [20].

(2) Mr Degning’s most recent conviction was on 21 September 2015 for “mid range of prescribed concentration of alcohol”. He was sentenced to seven months imprisonment, which was suspended upon entering a good behaviour bond of seven months, and a nine month licence disqualification: M[21].

(3) Before 2009, Mr Degning had a lengthy history of criminal conduct that dated back to 1977. This included offences relating to drugs, stealing, possession of stolen goods, drink driving, and assault. Mr Degning had received various penalties in the form of fines, licence disqualification and good behaviour bonds. He was also sentenced to terms of imprisonment in 1982 and 1983 of six months and nine months respectively: M[22].

75 In considering the risk to the Australian community, and concluding at M[36] that there was a risk “albeit low” that Mr Degning might “reoffend in a similar way”, the Minister took into account that:

(1) Mr Degning had indicated that he was ashamed of his criminal record and that he had pleaded guilty to the sexual offence, which showed some level of remorse and insight indicative of a lower likelihood of him re-offending: M[30];

(2) Mr Degning was 54 years old at the time of his most recent driving offence and that his “criminal history shows that despite some periods of years with no convictions, he continued to variously offend, despite court dispositions, including sentences of imprisonment in 1982, 1983 and 2013 and licence disqualifications”: M[32];

(3) Mr Degning failed to declare his criminal convictions on his Incoming Passenger Cards dated 4 January 2004, 20 April 2004 and 2 March 2006. The Minister considered this “indicative of a further disregard for the law”: M[33];

(4) notwithstanding the sentencing Judge’s observation of 24 July 2013, the sexual offending in 2009 occurred when Mr Degning was 48 and involved him taking advantage of a person who was vulnerable because of cognitive impairment: M[35].

76 The Minister took into account:

(1) the best interests of minor children. Mr Degning’s relationship with his grandchildren would be negatively impacted by the cancellation of his visa: M[38] to [41];

(2) that the Australian community expects non-citizens to obey Australian laws while in Australia: M[42] to [43];

(3) that Mr Degning had spent a significant amount of time contributing positively to the community in various ways and he had represented that his removal from Australia would be devastating for his family and friends, particularly his wife of some 36 years and his father, for whom Mr Degning provided care: M[44] to [50].

77 Having considered the matters summarised above, the Minister decided to exercise his discretion to cancel Mr Degning’s visa, concluding:

58. Mr DEGNING has committed a serious crime, that of sexual intercourse – person with cognitive impairment, which is of a sexual nature, and involved a vulnerable member of the community, that being a person with an intellectual disability. Also he has multiple drink driving convictions with his most recent in 2015 incurring a suspended term of imprisonment. Mr DEGNING and non-citizens who commit such offence [sic] should not generally expect to be permitted to remain in Australia.

59. I find that the Australian community could be exposed to harm should Mr DEGNING reoffend in a similar fashion. I could not rule out the possibility of further offending by Mr DEGNING. The Australian community should not tolerate any further risk of harm.

60. I found the above consideration outweighed the countervailing considerations in Mr DEGNING’s case, including the best interests of Kristian, Bree and Olivia and the impact on his wife and other family members. I have also considered the length of time Mr DEGNING has made a positive contribution to the Australian community and the consequences of my decision for minor children and other family members.

61. I am cognisant that where harm could be inflicted on the Australian community even strong countervailing considerations are generally insufficient for me not to cancel the visa. This is the case even applying a higher tolerance of criminal conduct by Mr DEGNING, than I otherwise would, because he has lived in Australia for most of their life, or from a very young age.

62. In reaching my decision I concluded that Mr DEGNING represents an unacceptable risk of harm to the Australian community and that the protection of the Australian community outweighed any countervailing considerations above.

63. Having given full consideration to all of these matters, I decided to exercise my discretion to cancel Mr DEGNING’s BF transitional (permanent) visa under s 501(2) of the Act.

PRIMARY JUDGMENT

78 On 4 June 2018 Mr Degning filed in this Court an amended application for judicial review, which raised the following three grounds (omitting particulars):

6. The Minister denied the Applicant procedural fairness having the consequence that the decision was affected by jurisdictional error.

7. The Minister’s decision was illogical, irrational and legally unreasonable, having the consequence that the decision was affected by jurisdictional error.

8. The Minister’s decision was affected by a denial of procedural fairness, having the consequence that the decision was affected by jurisdictional error, in circumstances where the Minister, although recognising that the interests of minor children were affected by his decision, failed to invite those minor children, or their legal guardian, to make submissions or give evidence on the issues relevant to the decision.

79 The primary judge rejected each ground.

Ground 6

80 The primary judge observed at J[73] that the copies of the Incoming Passenger Cards retrieved from the Department, which were tendered without objection, were legible and that the applicant gave no evidence, and had not proved, that the copies provided to him with the letter dated 29 December 2016 letter were illegible.

81 Mr Degning’s submission that this letter was internally contradictory and confusing was rejected:

[74] The first page of the letter of 29 December 2016 could, by itself, be taken to indicate that the Incoming Passenger Cards were listed as “information about your criminal history” because those Incoming Passenger Cards were “listed at the end of this notice” along with Minister Direction 65, the National Police Certificate and the Court Attendance and New South Wales Police Fact Sheet. In my opinion it is not a fair reading of the letter to construe the words used on the first page to mean that each and every document listed at the end of the notice indicated that the applicant had a substantial criminal record. The reference to the information listed at the end of the notice is to be read distributively and not so as to mean that every piece of information there listed indicated the applicant had a substantial criminal record. Further, approximate to that listing, on page three of the letter of 29 December 2016, the Incoming Passenger Cards were listed as “documents… which the decision-maker may rely on to decide whether your pass the character test; and if not, whether your visa should be cancelled.” If there was any ambiguity, which I do not accept, that specific statement dispelled it.

[75] For those reasons, I reject the submission on behalf of the applicant that the notice of intention to consider cancellation, the letter dated 29 December 2016, was “internally contradictor and confusing”.

82 As to the balance of Mr Degning’s particulars on this ground, the primary judge stated:

[77] In my opinion, the context was provided by the nature of the letter, which was directed to the applicant’s character, including the criminal history and whether his visa should be cancelled in light of his failure to pass the character test. The three Incoming Passenger Cards showed the applicant denying the existence of his convictions from 1982 to 2000. In my opinion, it was clear from the provision to the applicant of the Incoming Passenger Cards that an issue could be the applicant’s failure to declare his criminal record. It was not necessary to specify, so as to comply with procedural fairness, how this might bear on the risk that the applicant may re-offend.

[78] In my opinion, the potential adverse conclusions that could be drawn from the Incoming Passenger Cards were obvious. I reject the submission that it could not be said that the “nature” or “content” of the adverse material was disclosed to the applicant.

…

[80] Further, I do not accept that the inference that a failure to declare a criminal conviction on an Incoming Passenger Card is indicative of a propensity to re-offend is tendentious or so tendentious that the issue had to be squarely raised.

[81] In my opinion, the other matters raised on behalf of the applicant under Ground 6 take the issue no further.

Ground 7

83 The primary judge rejected Mr Degning’s characterisation of the Incoming Passenger Cards as routine administrative forms: at J[85]. As to the reasonableness of the Minister’s approach, the primary judge made the following remarks:

[86] What the Minister said at [33] was that the applicant’s failure to declare his criminal convictions was indicative of a further disregard for the law. Read fairly, this was a step to the conclusion, at [36], that there was a low risk that Mr Degning would re-offend in a similar way. I do not regard this process of reasoning as legally unreasonable. I do not accept the emphasis put by the applicant on the expression “in a similar way”: the Minister was considering whether the applicant had a propensity to commit further offences and reasoned that if the applicant did re-offend, he may re-offend in a manner similar to his previous offending.

…

[89] The second limb of the argument was that the Minister by-passed any meaningful assessment of re-offending “by imposing a risk threshold that was outside the range reasonably permitted by the statutory discretion” and this was therefore inconsistent with the existence of the statutory discretion. In my opinion, what the Minister said at [59] was no more than another way of putting the earlier conclusion, at [36], that there was a low risk that Mr Degning will re-offend in a similar way: see [86] above. Again, I do not regard this process of reasoning as legally unreasonable or inconsistent with the existence of the statutory discretion.

Ground 8

84 The primary judge concluded at J[92] to [94] that it was not accurate to say that the Minister had determined that Mr Degning’s grandchildren had an interest in, and therefore a right to comment on, the decision. This confused the interests of minor children as a mandatory relevant consideration with an interest from which an obligation to provide procedural fairness would stem. The primary judge identified at J[97] the difficulty in Mr Degning complaining of a denial of procedural fairness to his grandchildren, who were not parties to his application.

85 The primary judge concluded by noting the following at J[101]:

Independently, in my opinion, it is also difficult to reconcile this contention with any practical injustice suffered by the grandchildren where the Minister concluded, at [40], that it was in the best interests of the three grandchildren not to cancel Mr Degning’s visa …

THE APPEAL

86 The appellant relied upon three grounds of appeal. The first two grounds of appeal had not been argued before the primary judge. Leave was granted during the hearing for the grounds to be raised on appeal.

Ground 1

87 The first ground was:

1. The trial judge erred in reasoning that s 501 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) authorised the Respondent to cancel the Appellant’s visa when, on its proper construction and in light of s 7(2)(c) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), its provisions did not operate to affect the Appellant’s privilege to remain indefinitely in Australia pursuant to a visa which he had held prior to the enactment of s 501 on 1 September 1994.

88 In summary, the appellant submitted:

(1) once the time periods within which he could be deported under former ss 13 and 14(2) expired, he had an accrued right or privilege not to be deported from Australia;

(2) when s 501 was introduced into the Migration Act, it did not affect or remove that accrued right or privilege.

89 It will be recalled that, when Mr Degning came to Australia, he was an “immigrant”, but not an “alien” (because he was a British subject). Once he became the holder of an entry permit, he could only be deported under s 13 or s 14(2). The power to deport aliens was wider. The distinction was removed by the Migration Amendment Act 1983 (Cth), effective 2 April 1984: Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No S119, 30 March 1984.

90 Section 4 of the Amendment Act 1983, amongst other things:

(1) deleted the definition of “alien” and “immigrant” from s 5(1);

(2) inserted a definition of “non-citizen”, namely “a person who is not an Australian citizen”.

91 Section 10 of the Amendment Act 1983 repealed ss 12 and 13 of the Migration Act and substituted as a new s 12 a general power to deport a “non-citizen” present in Australia as a permanent resident for less than 10 years convicted of certain crimes either before or after the commencement of the section – see: Nolan v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1988) 165 CLR 178 at 187; Shaw v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2003) 218 CLR 28.

92 Section 11 of the Amendment Act 1983 amended s 14 of the Migration Act by substituting new sub-ss (1) and (2), which permitted deportation of a non-citizen on:

(1) “security” grounds (for those present in Australia as permanent residents for less than 10 years); and

(2) conviction of certain serious offences either before or after the commencement of the sub-section.

93 Section 21 of the Intelligence and Security (Consequential Amendments) Act 1986 (Cth) (Intelligence and Security Amendments Act) inserted a new s 13 into the Migration Act. It addressed deportation on security grounds of a non-citizen present in Australia as a permanent resident for at least 10 years. Section 22 of the Intelligence and Security Amendments Act consequently deleted s 14(1) of the Migration Act as it had been amended by s 11 of the Amendment Act 1983 (referred to at para [92] above). The amendments were effective from 1 February 1987: Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No S13, 27 January 1987.

94 From 20 December 1989, ss 12–14 of the Migration Act were renumbered as ss 55–57: Migration Legislation Amendment Act 1989 (Cth), ss 2(5), (6), 35; Endnote 5 to the Migration Act. They were the subject of further amendments from 1 September 1994 (ss 57 and 58 of the Migration Legislation Amendment Act 1994 (Cth)) and they were renumbered as ss 201–203 of the Act: s 83 of the Amendment Act 1994.

95 Section 501 was originally introduced as s 180A of the Migration Act by s 5 of the Migration (Offences and Undesirable Persons) Amendment Act 1992 (Cth). It was introduced with effect from 24 December 1992. At this time, the appellant was the holder of a permanent entry permit.

96 Section 180A provided:

(1) The Minister may refuse to grant a visa or an entry permit to a person, or may cancel a valid visa or a valid entry permit that has been granted to a person, if:

(a) subsection (2) applies to the person; or

(b) the Minister is satisfied that, if the person were allowed to enter or to remain in Australia, the person would:

(i) be likely to engage in criminal conduct in Australia; or

(ii) vilify a segment of the Australian community; or

(iii) incite discord in the Australian community or to a segment of that community, whether by way of being liable to become involved in activities that are disruptive to, or violence threatening harm to, that community or segment, or in any other way.

(2) This subsection applies to a person if the Minister:

(a) having regard to:

(i) the person’s past criminal conduct; or

(ii) the person’s general conduct;

is satisfied that the person is not of good character; or

(b) is satisfied that the person is not of good character because of the person’s association with another person, or with a group or organisation, who or that the Minister has reasonable grounds to believe has been or is involved in criminal conduct.

(3) The power under this section to refuse to grant a visa or an entry permit to a person, or to cancel a valid visa or a valid entry permit that has been granted to a person, is in addition to any other power under this Act, as in force from time to time, to refuse to grant a visa or an entry permit to a person, or to cancel a valid visa or a valid entry permit that has been granted to a person.

97 As recorded earlier, from 1 September 1994, the relevant entry permit for Mr Degning continued in effect as a transitional (permanent) visa.

98 Also from 1 September 1994, s 180A of the Migration Act was amended to delete the references to entry permits. It was renumbered as s 501 in accordance with the general renumbering that was effected by s 83 of the Amendment Act 1994 – see: item 113 of Sch 1 to the Amendment Act 1994; Endnote 5 to the Migration Act.

99 With effect from 1 June 1999, s 501 was repealed and substituted by item 23 of Sch 1 to the Migration Legislation Amendment (Strengthening of Provisions relating to Character and Conduct) Act 1998 (Cth). Item 28(2) of Sch 1 provided:

The amendment made by item 23, to the extent that it relates to visas granted to a person, applies to visas granted before, on or after the commencement of that item.

100 On 17 July 2008, a Full Court of this Court held that s 501, as it relevantly stood, did not apply to a transitional (permanent) visa continued in effect by reg 4 of the Transitional Provisions 1994 because it was not a visa which was “granted”: Sales v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2008) 171 FCR 56. As noted at[ 60] and [61] above, it was this provision which operated with respect to Mr Degning such that the relevant entry permit continued in effect as a transitional (permanent) visa.

101 Item 5 of Sch 4 to the Migration Legislation Amendment Act (No 1) 2008 (Cth) inserted s 501HA into the Migration Act. It provided:

If, under the Migration Reform (Transitional Provisions) Regulations, a person:

(a) held a permanent return visa, permanent entry permit or permanent visa that continues in effect as a transitional (permanent) visa; or

(b) held a temporary entry permit or temporary visa that continues in effect as a transitional (temporary) visa; or

(c) is taken to hold a transitional (permanent) visa;

the person is also taken, for the purposes of sections 501 to 501H, to have been granted a visa.

102 It was not in dispute that this provision was intended to overcome the effect of the conclusion ultimately reached in Sales – for a more detailed account, see: Bainbridge v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2010) 181 FCR 569 at [5], [6] (Moore and Perram JJ).

103 Section 501HA had effect from 19 September 2008 – see: item 6 of the table in s 2 of the Amendment Act (No 1) 2008.

104 The amendment made by item 5 in Sch 4 of the Amendment Act (No 1) 2008 (the insertion of s 501HA) “applies in respect of a decision to cancel a visa that is made under the Migration Act 1958 on or after the day on which that item commences”: Item 6(3) of Sch 4 of the Amendment Act (No 1) 2008. The Minister’s decision in the present case was made after s 501HA commenced.

105 The parts of s 501 relevant to the Minister’s decision to cancel the appellant’s visa, namely ss 501(2), (6)(a) and (7)(c), were inserted in the 1999 repeal and substitution by the Amendment Act 1998, and were unaffected by subsequent amendments.

106 Section 7(2)(c) of the Acts Interpretation Act provides:

If an Act, or an instrument under an Act, repeals or amends an Act (the affected Act) or a part of an Act, then the repeal or amendment does not:

…

(c) affect any right, privilege, obligation or liability acquired, accrued or incurred under the affected Act or part.

107 It was effective from 27 December 2011 and applies only to repeals and amendments after that date: Acts Interpretation Amendment Act 2011 (Cth), s 2(1), Sch 1 item 13, Sch 3 item 4.

108 Before 27 December 2011, s 8(c) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) provided:

Where an Act repeals in the whole or in part a former Act, then unless the contrary intention appears the repeal shall not:

…

(c) affect any right privilege obligation or liability acquired accrued or incurred under any Act so repealed.

109 The former s 8 applied only to repeals (a subtraction from the scope of legal operation), not also to amendments (a change in legal meaning) – as to the meaning of “repeal” and “amendment” in this context see: ADCO Constructions Pty Ltd v Goudappel (2014) 254 CLR 1 at [49] (Gageler J).

110 In any event, it was accepted by both parties that there is a common law presumption against reading a statute in such a way as to change accrued rights. In Maxwell v Murphy (1957) 96 CLR 261 at 267, Dixon CJ stated:

The general rule of the common law is that a statute changing the law ought not, unless the intention appears with reasonable certainty, to be understood as applying to facts or events that have already occurred in such a way as to confer or impose or otherwise affect rights or liabilities which the law had defined by reference to the past events.

This statement was approved in ADCO Constructions at [27] by French CJ, Crennan, Kiefel and Keane JJ and at [50] by Gageler J.

111 It is perhaps also useful to set out the formulation given by Dixon J in Kraljevich v Lake View and Star Ltd (1945) 70 CLR 647 at 652:

The presumptive rule of construction is against reading a statute in such a way as to change accrued rights the title to which consists in transactions passed and closed or in facts or evens that have already occurred. In other words, liabilities that are fixed, or rights that have been obtained, by the operation of the law upon facts or events for, or perhaps it should be said against, which the existing law provided are not to be disturbed by a general law governing future rights and liabilities unless the law so intends …