FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aussiegolfa Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCAFC 122

ORDERS

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within seven days, the parties file any agreed minute of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons and as to costs.

2. If the parties do not agree, then, within 14 days of the date of these orders, each party file and serve the party’s proposed orders together with a written submission (of no more than two pages) in support of the proposed orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 83 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Applicant | |

AND: | AUSSIEGOLFA PTY LTD (ACN 153 569 807) AS TRUSTEE OF THE BENSON FAMILY SUPERANNUATION FUND (ABN 12 476 482 589) Respondent | |

JUDGES: | BESANKO, MOSHINSKY AND STEWARD JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 aUGUST 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within seven days, the parties file any agreed minute of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons and as to costs.

2. If the parties do not agree, then, within 14 days of the date of these orders, each party file and serve the party’s proposed orders together with a written submission (of no more than two pages) in support of the proposed orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO J:

1 I have had the advantage of reading the reasons for judgment of Moshinsky J. I agree with the conclusions which his Honour has expressed and his reasons for those conclusions. There is nothing I wish to add.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Besanko. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

2 Aussiegolfa Pty Ltd (Aussiegolfa) is the trustee of a self-managed superannuation fund known as the Benson Family Superannuation Fund (the Benson Fund). Mr Christopher Benson is the sole member of the Benson Fund. The issues raised by these proceedings relate to an investment by Aussiegolfa (in its capacity as trustee of the Benson Fund) in a managed investment scheme known as the DomaCom Fund (the DomaCom Fund).

3 In July and August 2015, Aussiegolfa acquired units of a particular class in the DomaCom Fund. The class of units was associated with the acquisition, by the responsible entity of the DomaCom Fund, of a property in Burwood, Victoria (the Burwood Property). The units of this class were referred to in contemporaneous documents as units in the “Burwood Sub-Fund”, being a sub-fund of the DomaCom Fund (the Burwood Sub-Fund). The units of the class were held: as to 25 per cent by Aussiegolfa; as to 50 per cent by Mr Benson’s mother; and as to 25 per cent by a superannuation fund of Mr Benson’s sister and her husband.

4 The custodian of the DomaCom Fund entered into an exclusive leasing and managing authority with Student Housing Australia Pty Ltd (Student Housing Australia) for the leasing of the Burwood Property. The first two tenants of the property were persons unknown, and unrelated, to Mr Benson, or to the Benson Fund. In April 2017, Student Housing Australia agreed to lease the apartment to Mr Benson’s daughter (Ms Benson), with the lease commencing in February 2018 at the same monthly rental as had been paid by the first two tenants.

5 The Benson Fund was at the relevant times eligible for concessional tax treatment under Div 295 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) provided it was a “complying superannuation fund”. The requirements for a complying superannuation fund were set out in the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (the SIS Act). The requirements relevantly included:

(a) that the fund complied with the in-house asset rules (see SIS Act, s 84); and

(b) that the fund satisfied the sole purpose test (see SIS Act, s 62).

6 Aussiegolfa’s units in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) constituted 7.83 per cent of its assets (that is, the assets of the Benson Fund). The in-house asset rules effectively limited investments in in-house assets to a maximum of five per cent of the market value of all assets in the fund. Thus, an issue arose as to whether Aussiegolfa’s units constituted an “in-house asset”. The expression “in-house asset” was defined in s 71(1) of the SIS Act as meaning (among other things) “an investment in a related trust of the fund”, but did not include “an investment in a widely held unit trust”.

7 Further, s 71(4) of the SIS Act provided that, if an asset of a fund consisted of an investment “other than an in-house asset”, the regulator (who was the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner)) could make a determination that the asset was to be treated “as if the asset were … an investment in … a specified … related trust of the fund”. In the present case, on 3 July 2017, the Commissioner made a determination that the units held by Aussiegolfa in the Burwood Sub-Fund were to be treated as an investment in a related trust of the Benson Fund (the Determination).

8 The sole purpose test, in brief terms, required the trustee to ensure that the fund was maintained solely for one or more of certain prescribed purposes.

9 Aussiegolfa commenced a proceeding in the Federal Court of Australia seeking declaratory relief (the Federal Court proceeding). In broad terms, Aussiegolfa sought declarations to the effect that: its units in the DomaCom Fund did not constitute an in-house asset; and the leasing of the Burwood Property to Mr Benson’s daughter would not cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test.

10 Aussiegolfa also commenced a proceeding in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (the Tribunal) by which it sought review of the Determination (the Tribunal proceeding). The Tribunal proceeding was heard immediately after the hearing of the Federal Court proceeding, and the evidence in the Federal Court proceeding was evidence also in the Tribunal proceeding. The Tribunal was constituted by the judge who heard the Federal Court proceeding, sitting as a Deputy President of the Tribunal.

11 In the Federal Court proceeding, the primary judge decided that the units held by Aussiegolfa in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) did constitute an in-house asset; and that leasing the Burwood Property to Mr Benson’s daughter would cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test. His Honour therefore declined to make the declarations sought by Aussiegolfa and dismissed the proceeding.

12 In the Tribunal proceeding, the Tribunal set aside the Determination on the basis that the units held by Aussiegolfa had been found to be an in-house asset; accordingly, the condition for exercising the power in s 71(4) (namely, that the asset was not an in-house asset) was absent.

13 Aussiegolfa appeals to this Court from the judgment of the primary judge in the Federal Court proceeding (the Federal Court Appeal).

14 The Commissioner ‘appeals’ on a question of law under s 44 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth) from the decision of the Tribunal (the AAT Appeal). The AAT Appeal, which is in the original jurisdiction of the Court, is effectively contingent on Aussiegolfa succeeding on the in-house asset issues in the Federal Court Appeal. The two appeals were heard together.

15 The issues raised by the Federal Court Appeal can be summarised as follows:

(a) whether the primary judge erred in concluding that the units held by Aussiegolfa in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) constituted an investment in a “related trust” of the Benson Fund for the purposes of Pt 8 of the SIS Act (the Related Trust Issue);

(b) whether the primary judge erred in concluding that the units did not constitute an investment in a widely held unit trust (the Widely Held Trust Issue); and

(c) whether the primary judge erred in concluding that the leasing of the Burwood Property to Mr Benson’s daughter would cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test (the Sole Purpose Issue).

16 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that:

(a) the primary judge was correct to conclude that the units held by Aussiegolfa in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) constituted an investment in a “related trust” of the Benson Fund;

(b) the primary judge was correct to conclude that the units did not constitute an investment in a widely held unit trust;

(c) the primary judge erred in concluding that the leasing of the Burwood Property to Mr Benson’s daughter would cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test.

17 It follows that the Federal Court Appeal is to be allowed in part. In circumstances where the AAT Appeal is effectively contingent on Aussiegolfa succeeding on the in-house asset issues in the Federal Court Appeal, it follows from the rejection of the grounds of appeal relating to those issues that the AAT Appeal is to be dismissed.

Background facts

18 The following statement of the background facts is substantially based on the reasons of the primary judge in the Federal Court proceeding: Aussiegolfa Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Commissioner of Taxation [2017] FCA 1525 (the Federal Court Reasons). In addition, I have drawn on some of the documents in the Appeal Book.

The Benson Fund

19 On 20 November 2011, the Benson Fund was established as a self-managed superannuation fund within the meaning of s 17A(2) of the SIS Act. Mr Benson was the sole member of the Benson Fund. Since January 2015, he has been employed as the Victorian State Manager of DomaCom Australia Ltd (DomaCom).

20 On 15 February 2013, the Commissioner issued a notice under s 40 of the SIS Act to the Benson Fund (this being one of the requirements to be a complying superannuation fund – see SIS Act, s 45). Apart from the issues raised by these proceedings, there is no dispute that the Benson Fund was a complying superannuation fund.

The DomaCom Fund

21 The DomaCom Fund is governed by a Constitution (the Constitution). The Appeal Book contains copies of the Constitution with various dates, including 27 November 2013 and 13 December 2013. As discussed below, the version dated 13 December 2013 was in effect in 2015. The Constitution was declared by Perpetual Trust Services Ltd as responsible entity (the Responsible Entity). The DomaCom Fund is a registered managed investment scheme under Ch 5C of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

22 The investment manager of the DomaCom Fund is DomaCom. DomaCom holds an Australian Financial Services Licence.

23 The custodian of the DomaCom Fund is Perpetual Corporate Trust Ltd (the Custodian).

February to July 2015

24 In February 2015, Mr Benson and his mother, brother and sister resolved at a family meeting to invest in residential property in student accommodation and other relatively low cost, relatively high return opportunities. Mr Benson’s mother is a self-funded retiree living in Melbourne. Mr Benson’s brother and sister set up their own self-managed superannuation funds shortly after the February meeting.

25 On 4 March 2015, the Responsible Entity issued a product disclosure statement. This document is referred to in Aussiegolfa’s application for units. It is not necessary to refer to this document in detail.

26 In March 2015, Mr Benson and members of his family inspected the Burwood Property, being a studio apartment in a student accommodation complex. They decided to invest in the property through the DomaCom Fund by Mr Benson’s mother acquiring 50 per cent of the units in a sub-fund of the DomaCom Fund, and Mr Benson and his sister (through their respective superannuation funds) each agreeing to purchase 25 per cent of the units in the sub-fund. Mr Benson’s brother decided not to participate in the acquisition of any units.

27 On 31 March 2015, Aussiegolfa completed and forwarded an application to invest in the DomaCom Fund. The application was for a minimum investment of $20,000 to establish an account in the DomaCom Fund and acknowledged that Mr Benson had received a product disclosure statement and that, if the application for Aussiegolfa to become an investor were accepted, the investment would be “subject to the terms and conditions of the Constitution and Product Disclosure Statement”, as amended from time to time.

28 On or about 2 April 2015, Aussiegolfa paid $20,000 and, shortly thereafter, Aussiegolfa paid an additional $8,080, for the acquisition of 28,080 $1 units in a sub-fund. The $28,080 paid by Aussiegolfa was held by the Responsible Entity in a cash pool (the Cash Pool) pending acquisition by the Responsible Entity of the Burwood Property.

29 On 24 June 2015, the Responsible Entity issued a product disclosure statement (the June 2015 Product Disclosure Statement). Extracts from this document are set out below.

30 On 17 July 2015, the Responsible Entity issued a supplementary product disclosure statement, dealing specifically with a proposed sub-fund that planned to invest in the Burwood Property (the Supplementary Product Disclosure Statement). Extracts from this document are set out below.

31 In July 2015, DomaCom completed due diligence, contract review and valuation procedures in respect of the Burwood Property.

The acquisition of the units - July and August 2015

32 On 21 July 2015, the Custodian entered into a contract to purchase the Burwood Property for $104,000. The settlement date was 18 August 2015.

33 Upon entry into the contract to purchase the Burwood Property and payment of the initial deposit, the Burwood Sub-Fund (being a sub-fund numbered DMC0114AU) was established within the DomaCom Fund, and a class of units unique to the sub-fund was created.

34 Ross Laidlaw, the director and Chief Operating Officer of DomaCom, gave evidence below that a new sub-fund was created with the issue of a new and unique class of units as soon as a binding contract to purchase the property was entered into and the initial deposit paid. The Responsible Entity did not pass a resolution to amend the Constitution to create the new units; the new class of units was created by the DomaCom system. An Asia Pacific Investment Register or APIR code was then allocated to the units. APIR codes are standard identifiers for products in the financial services industry.

35 On 23 July 2015 and 17 August 2015, funds held for Aussiegolfa in the Cash Pool were applied towards the acquisition of units in the Burwood Sub-Fund. DomaCom provided various statements in relation to the Benson Fund, including a periodic statement and transaction history for the period from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016. That statement showed the creation of units on 23 July 2015 and 17 August 2015. Aussiegolfa acquired in total 25 per cent of the units in the Burwood Sub-Fund. Mr Benson’s mother acquired 50 per cent of the units in the Burwood Sub-Fund, and the superannuation fund of Mr Benson’s sister and her husband acquired 25 per cent.

36 The application that had been made on 31 March 2015 appears to have been taken as sufficient for the creation of the Burwood Sub-Fund and for the allocation of units to Aussiegolfa pursuant to the Constitution.

37 On 17 August 2015, the Custodian entered into an exclusive leasing and managing authority with Student Housing Australia for the leasing of the Burwood Property.

38 On 18 August 2015, settlement of the purchase of the Burwood Property took place.

August 2015 to July 2017

39 The first two student tenants for the Burwood Property found by Student Housing Australia were persons unknown, and unrelated, to Mr Benson or to the Benson Fund. The first tenant agreed to pay a monthly rental of $869 for the premises from 8 January 2016 to 23 January 2017. The second tenant also agreed to pay a monthly rent of $869 for the premises for the period from 20 February 2017 until 15 February 2018.

40 On 3 April 2017, Mr Benson (as DomaCom’s Victorian State Manager) informed DomaCom’s client services manager in an email that Mr Benson and some family members were using the Burwood Property to test “the related party use of residential property within” self-managed superannuation funds.

41 On 11 April 2017, Mr Benson submitted a completed application form to Student Housing Australia on behalf of his daughter to lease the Burwood Property from 20 February 2018 at a monthly rent of $869. Mr Benson was identified in the application as the parental guarantor guaranteeing his daughter’s obligations under the proposed lease.

42 Also on 11 April 2017, Student Housing Australia wrote to Ms Benson congratulating her on securing the tenancy of the Burwood Property at the rent that had been proposed in the application. At about the same time, Ms Benson signed a standard form Residential Tenancy Agreement for the property providing for rental for the period 20 February 2018 until 19 February 2019 at the monthly rent of $869.

43 The primary judge found, at [8] of the Federal Court Reasons, that the selection of Ms Benson as the tenant of the Burwood Property was explained, in part, by the desire of Mr Benson and DomaCom to test the ability for residential properties held by self-managed superannuation funds to be used by related parties.

44 As at 21 April 2017, Aussiegolfa’s units in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) represented 7.83 per cent of the assets of the Benson Fund.

45 In May 2017, Aussiegolfa commenced the Federal Court proceeding.

46 On 3 July 2017, the Commissioner made the Determination, being a determination under s 71(4) of the SIS Act that the units held by Aussiegolfa as trustee for the Benson Fund in the Burwood Sub-Fund were to be treated as an investment in a related trust of the Benson Fund.

47 I now set out the key relevant provisions of: the Constitution as it stood in 2015; the June 2015 Product Disclosure Statement; the Supplementary Product Disclosure Statement; and the Constitution as at May 2017. I refer to both the Constitution as at 2015 and the Constitution as at May 2017, as there is an issue whether the relevant version is the former or the latter or both.

The Constitution as at 2015

48 At the hearing of the appeals, both parties proceeded on the basis that the copy of the Constitution (dated 13 December 2013) at AB, Pt C, tab 89.4 represented the Constitution as it stood during 2015 (the Commissioner’s outline of submissions in the Federal Court Appeal, fn 16; T9). I note that the Appeal Book (at Pt C, tab 89.5) contains a Supplemental Constitution dated 31 January 2014, which contains some amendments, but these do not appear to be material for present purposes. I note also that the primary judge stated, at [12] of the Federal Court Reasons, that the Constitution had been altered between the time of Aussiegolfa’s application for units (31 March 2015) and the time when the units were acquired (July and August 2015). However, on the hearing of the appeals, neither party referred to any material changes having been made during 2015. The amended joint chronology does not refer to any such changes.

49 The only party to the Constitution was the Responsible Entity. The recital stated that the Constitution was declared by the Responsible Entity to be the constitution for a trust to be known as the DomaCom Fund.

50 The word “Assets” was defined in cl 1.1 as meaning “cash, investments, rights, income and other property of the Fund or a Class from time to time”.

51 The word “Class” was defined as meaning “a class of Units as determined by the Responsible Entity under clause 3.4”. It should be noted that the Constitution did not refer to sub-funds, but to classes of units.

52 The word “Fund” was defined as meaning “the trust constituted by this Constitution and known as the DomaCom Fund”.

53 The expression “Relevant Class” was defined as meaning “a Class of Units”. The definitions in cl 1.1 also included:

Relevant Liabilities means the Liabilities referable to the Relevant Class. Where Liabilities are referable to more than one Relevant Class, then for the purposes of the definition of Relevant Liabilities, such amount of the Liabilities will be included as the Responsible Entity determines is properly referable to the Relevant Class.

Relevant Scheme Assets means the Assets referable to the Relevant Class. Where an Asset is referable to more than one Relevant Class, then for the purposes of the definition of Relevant Scheme Assets, such amount of the Asset will be included as the Responsible Entity determines is properly referable to the Relevant Class.

54 “Unit” was defined as meaning “a unit in the Fund created under this Constitution”.

55 Clause 2.1 stated that, as from the Commencement Date (being the date of commencement of the Fund), Perpetual Trust Services Ltd was, and had agreed to act as, the responsible entity of the Fund.

56 Clause 2.2 was in the following terms:

Declaration of Trust

(a) The Assets shall vest in the Responsible Entity on the Commencement Date and the Responsible Entity declares that it shall hold:

(i) the money held in the Wholesale Cash Pool on trust for the Wholesale Cash Holders; and

(ii) the money held in the Retail Cash Pool on trust for the Retail Cash Holders; and

(iii) each Asset that is acquired on behalf of a Class of Unit Holders, on trust for Unit Holders in that Class; and

(iv) any other Assets that are not held on trust pursuant to clause 2.2(a)(ii) on trust for the Members generally,

in accordance with the terms of this Constitution.

(b) The Responsible Entity shall clearly identify the Assets as property of the Fund and hold the Assets separately from the assets of the Responsible Entity and any other managed investment scheme to the extent required by the Corporations Act.

(Emphasis added.)

57 Clause 3.1 was as follows:

Interests and Units

(a) The beneficial interest in the Fund is divided into:

(i) interests in the Cash Pool based on each Cash Holder’s proportionate interest in the Cash Pool; and

(ii) Units.

(b) Subject to the rights attaching to a Class of Units, each Unit confers on the Unit Holder a beneficial interest in the Assets as an entirety and does not confer an interest in a particular Asset.

58 Clause 3.4 was in the following terms:

Classes

(a) Subject to section 601FC(1)(d) of the Corporations Act, the Responsible Entity may create different Classes of Units in the Fund with such rights, obligations and restrictions attaching to the Units of such Classes as it determines. If the Responsible Entity so determines in relation to a particular Class, the terms of issue of those Units in that Class may:

(i) eliminate, reduce or enhance any of the rights or obligations which would otherwise be carried by such Units; and

(ii) provide for conversion of Units from one Class to another Class and, if the Responsible Entity so determines, change the number of Units on such a conversion.

For the avoidance of doubt, each Cash Pool is a separate Class of interest in the Fund.

(b) The Responsible Entity in making any determination of a variable properly referable to a Class under this Constitution must ensure that:

(i) any variable which relates only to a particular Class, and does not relate to other Classes, is solely referrable to the Class to which it relates; and

(ii) any variable that relates to more than one Class is apportioned between those Classes either:

(A) in the same proportions as the aggregate value of Units on issue in each Class as at the most recent Valuation Time bears to the aggregate value of Units in all Classes to which the variable relates on issue at the most recent Valuation Time; or

(B) if the methodology referred to in clause 3.4(b)(ii)(A) would result in the Responsible Entity breaching its obligation to treat Unit Holders who hold different Classes fairly in contravention of section 601FC(1)(d) of the Corporations Act, then the Responsible Entity must apportion the relevant variable that relates to more than one Class in a manner that treats Unit Holders in different Classes fairly.

(c) Notwithstanding the generality of this clause 3, the Responsible Entity must only issue Classes of Units in the following circumstances:

(i) the Relevant Scheme Assets for each Class comprise a particular Property and all proceeds and income received by the Responsible Entity in respect of, or relating to, that Property;

(ii) the Relevant Liabilities are attributed to a Class such that they can only be met from Relevant Scheme Assets;

(iii) Relevant Scheme Assets for a Class are not encumbered in relation to Relevant Liabilities of another Class; and

(iv) the Responsible Entity is not entitled to be indemnified out of the Relevant Scheme Assets of a Class in relation to Relevant Liabilities of another Class.

(d) Within 7 days of the first issue of Units in a Class, the Responsible Entity must notify ASIC of the establishment of that Class.

(Emphasis added.)

In the present case, although there is no document to this effect, it is clear that, on or about 23 July 2015, the Responsible Entity created a class of units associated with the Burwood Property, pursuant to cl 3.4(a). These units were referred to in the contemporaneous documents as units in the Burwood Sub-Fund. One of the issues discussed during the hearing of the appeals was whether the Responsible Entity also made a determination, pursuant to cl 3.4(a), as to the “rights, obligations and restrictions” attaching to this class of units. This issue is discussed later in these reasons.

59 Clause 3.6 was as follows:

Rights attaching to Units

(a) A Unit Holder holds a Unit subject to the rights and obligations attaching to that Unit.

(b) Each Unit Holder agrees not to:

(i) interfere with or question the rights, powers, authority, discretion or obligations of the Responsible Entity under this Constitution;

(ii) exercise any right, power or privilege in respect of an Asset;

(iii) lodge a caveat in respect of any Asset; or

(iv) require that any Asset be transferred to the Unit Holder or any other person.

(c) A Unit Holder may not create any mortgage, charge, pledge, lien, encumbrance, arrangement for the retention of title or any other Security Interest over a Unit without the consent of the Responsible Entity.

60 Clause 4 dealt with the application procedure. Clause 4.1 provided that the Responsible Entity could at any time offer: (a) a Cash Holder the right to deposit money in the Cash Pool in anticipation of subscribing for units; and (b) units for subscription or sale, and could invite persons to make offers to apply for or buy units. Clause 4.3 relevantly provided that each application for an interest in the Cash Pool or units would, unless the Responsible Entity approved otherwise, “conform with the form and content requirements of any relevant disclosure document”.

61 Clause 5 dealt with the application price for units in a class. In relation to a “subsequent issue” of units, that is, an issue after the initial issue, there was a formula for the issue price. It was provided that the references to “Net Asset Value”, “Transaction Charge” and the “number of Units on issue” were variables to be determined by the Responsible Entity in respect of the relevant class in accordance with cl 3.4.

62 Clause 8 dealt with the withdrawal price of units. A formula was set out for calculating the withdrawal price. It was provided that, for the purposes of the formula, where there was more than one class on issue, “Net Asset Value”, “Transaction Charge” and the “number of Units on issue” were variables to be determined by the Responsible Entity in respect of the relevant class in accordance with cl 3.4.

63 Clause 11 dealt with valuation of assets. Clause 11.2 provided that the Responsible Entity could determine the “Net Asset Value” of a class at any time. It also provided that the Responsible Entity was required to determine the “Net Asset Value” of a class in certain circumstances, as there set out.

64 Clause 12 dealt with income and distributions. Clause 12.4 provided that the Responsible Entity was required to determine the “Net Income” of each class for each financial year. Clause 12.5 dealt with the method of calculation of the “Net Income” for each class to the extent that no determination was made under cl 12.4. Clause 12.6 provided that, “[s]ubject to the rights, restrictions and obligations attaching to any particular Unit or Class”, unit holders were entitled in the proportions set out in cl 12.7 to the “Net Income” for the financial year. Clause 12.7(c) was in the following terms:

Subject to the rights, obligations and restrictions attaching to any particular Unit or a Class, each Unit Holder’s Distribution Entitlement for a Financial Year shall be determined in accordance with the following formula:

A x B

C

Where:

A is the amount determined by the Responsible Entity in accordance with clauses 12.4 and 12.5 to be distributable for each Class for the relevant Financial Year;

B is the aggregate of the number of Units of each Class held by the Unit Holder at 5.00 p.m. on the Distribution Calculation Date; and

C is the aggregate of the total number of Units of each Class on issue at 5.00 p.m. on the Distribution Calculation Date.

Two observations may be made about this clause. The first is that the distribution entitlement was expressed to be “[s]ubject to the rights, obligations and restrictions attaching to any particular Unit or a Class”. The second is that, if the formula operated, the net income distributable to a unit holder was derived from the amount determined to be distributable for each class.

65 Clause 12.11 was in the following terms:

Capital distributions

The Responsible Entity may, at any time, distribute the capital referable to a particular Class to the Unit Holders. Subject to the rights, obligations and restrictions attaching to any particular Unit or Class, a Unit Holder is entitled to that proportion of the capital to be distributed as is equal to the number of Units of a Class held by that Unit Holder on a date determined by the Responsible Entity divided by the number of Units of the same Class on issue on that date. A distribution under this clause may be in cash or of Assets.

66 Clause 12.13 was as follows:

Categories and source of income

The Responsible Entity may keep separate accounts for each Class of different categories or sources of income, or deductions or credits for tax purposes, and may allocate income, deductions or credits from a particular category or source to particular Unit Holders of a particular Class. The Responsible Entity must allocate income and expenses referable to a particular Class to that Class and must allocate all other income and expenses on a fair and reasonable basis across all Classes.

67 Clause 12.19 (classes) provided that, for the avoidance of doubt, the rights of a unit holder under cl 12 were “subject to the rights, restrictions and obligations attaching to any particular Unit or the Class”.

68 Clause 13.2 set out specific powers of the Responsible Entity. These included the power to “create different Classes with different rights and entitlements”.

69 Clause 15 dealt with remuneration and expenses of the Responsible Entity. Clause 15.1 provided that, subject to the Corporations Act and cl 15.9, the Responsible Entity was entitled to deduct from the “Assets of the Fund”, a management fee determined by the Responsible Entity and notified to unit holders up to certain maximum percentage amounts. Clause 15.2(a) provided that, subject to cl 15.1, the Responsible Entity could determine different fees for different classes. Clause 15.2(b) provided:

If the Responsible Entity determines that different Management Fees are payable with respect to different Classes, then for the purpose of calculating Management Fees for a Class pursuant to clause 15.1, the Responsible Entity may allocate Assets and Liabilities of the Fund to specific Classes and the term “Gross Asset Value” in clause 15.1, is taken to mean the “Gross Asset Value” of Assets attributed to the specific Class. Management Fees for different Classes will be charged against the Assets of that Class.

70 Clause 15.9 was as follows:

Class Expenses

Subject to the Corporations Act, where more than one Class is on issue and the Responsible Entity may make a determination that an Expense, or part of an Expense, is to be a Class Expense in relation to a Class, but if no determination is made under this clause, then:

(a) in respect of fees of the Responsible Entity which are charged to a particular Class, the GST on those fees and the corresponding reduced input credit or input credit (as the case may be) that arises in connection with a fee payable or supply in respect of a Class, is to be referable to that Class; and

(b) any other Expenses under this clause 15 is to be referable to all Units on an equal basis.

71 Clause 18.1 was as follows:

Responsible Entity’s indemnity

In addition to any indemnity available to the Responsible Entity under the law or this Constitution, but subject to the Corporations Act, the Responsible Entity has a right to be fully indemnified out of the Assets, in respect of all Expenses, Liabilities, costs and any other matters in connection with the Fund and against all actions, proceedings, costs, claims and demands brought against the Responsible Entity in its capacity as responsible entity of the Fund in respect of any matter or thing done or omitted (Indemnified Matter) except:

(a) in the case of the Responsible Entity’s own fraud, negligence or wilful default; and

(b) in respect of the overhead expenses of the Responsible Entity.

72 Under cl 18.3, the Responsible Entity could pay out of “the Assets” any amount for which it would be entitled to be indemnified under cl 18.1.

73 Clause 21.2 provided that, subject to the Corporations Act and any other approval required by law, the Responsible Entity could by deed replace or amend the Constitution.

74 Clause 23 dealt with termination. Under cl 23(a), the Fund terminated on the earlier of certain specified events, one of which was the day 80 years less one day from the commencement of the Fund. Clause 23(b) was as follows:

A Class of Units terminates on the earlier of:

(i) the date determined by the Responsible Entity as the date on which the Class of Units is to be terminated, being a date at least 30 days after the date of the provision of notice of such termination to all Unit Holders in that Class;

(ii) termination of the Fund under clause 23(a);

(iii) the date determined by a resolution of Unit Holders of that Class passed by at least 75% of all Unit Holders in that Class;

(iv) subject to clause 23(c), the term set out in the Initial Disclosure Document for the Class (Initial Term) (which must not exceed 15 years from the date of the first issue of Units in that Class), unless the term is extended by an ordinary resolution of Unit Holders of that Class (present in person or by proxy);

(v) when the Unit Holders of a Class:

(A) approve the change of the trustee of a Class from the Responsible Entity to another entity; or

(B) pass an extraordinary resolution (as defined in the Corporations Act) to change the custodian;

(vi) the date determined by the Responsible Entity as the date on which the Class of Units is to be terminated, being a date at least 30 days after the date of the provision of notice of such termination to all Unit Holders in that Class.

75 Clause 24 dealt with termination and winding up. Clause 24.1 was as follows:

Realisation of Assets

(a) On the termination and winding up of the Fund, the Responsible Entity shall:

(i) not issue further interests in the Cash Pool and will pay to the Cash Holders the balance of the Cash Holders’ beneficial interest in the Cash Pool (after payment of all Liabilities and expenses attributable to the Cash Holders);

(ii) not issue or redeem Units in the Fund; and

(iii) sell and realise the Assets and, subject to clauses 24.2(c), 24.3 and 24.5, distribute to the Unit Holders the amount calculated in accordance with clause 24.2(a).

(b) On the termination and winding up of a Class of Units, the Responsible Entity shall:

(i) not issue or redeem Units in that Class; and

(ii) sell and realise the Asset held for that Class and, subject to clauses 24.2(c), 24.3 and 24.5, distribute to the Unit Holders the amount calculated in accordance with clause 24.2(a).

76 Clause 24.2(a) was as follows:

Subject to the terms of issue of any Unit or Class (as set out in this Constitution), the net proceeds of realisation, after making allowance for all Liabilities (actual and anticipated) of the Fund (in the case of the termination of the fund) or a Class (in the case of a termination of a Class of Units) and meeting the expenses (including anticipated expenses) of the termination, shall be distributed pro rata by the Responsible Entity to Unit Holders in the relevant Class according to the number of Units they hold less the value of any Assets transferred to or to be transferred to that Unit Holder under clause 24.2(b). The Responsible Entity may distribute proceeds of realisation in instalments.

77 Clause 29 provided that the “Constitution binds the Responsible Entity and each present and future Cash Holder or Unit Holder … in accordance with its terms (as amended from time to time) as if each of them had been a party to this Constitution”.

78 Clause 30 provided that, except as required by the Corporations Act, all obligations of the Responsible Entity that could otherwise be implied or imposed by law or equity were expressly excluded to the extent permitted by law.

The June 2015 Product Disclosure Statement

79 The June 2015 Product Disclosure Statement was issued on 24 June 2015. Under the heading “Important Notice & Disclaimer” on the first page, it stated that the document related to an offer of interests in the DomaCom Fund consisting of interests in the Cash Pool and units in sub-funds to be established in the DomaCom Fund. It stated that a supplementary product disclosure statement would be issued with details in respect of each underlying property. Further down that page, it was stated that:

None of the Responsible Entity, DomaCom or any of their directors, advisers, agents or associates in any way guarantee the performance of the DomaCom Fund, any return of capital or any particular rate of return on an investment in the DomaCom Fund and, to the maximum extent permitted by law, they each deny liability for any loss or damage suffered by any person investing in the DomaCom Fund. Investors should note that the DomaCom Fund includes a number of Sub-Funds. The assets of one Sub-Fund are not available to satisfy liabilities in another Sub-Fund.

(Emphasis added.)

80 Section 2 of the document was headed “Overview of the DomaCom Fund”. This set out a series of questions and answers. Alongside the question, “What is the DomaCom Fund?” it was stated:

The DomaCom Fund is designed to simulate investment in direct property. The DomaCom Fund facilitates investment in a fractional interest in a property, being the Underlying Property held by a Sub-Fund.

DomaCom will place the details for each property on the DomaCom Website and an investor that wishes to invest in that property will be issued units in a Sub-Fund which will acquire and hold the Underlying Property on behalf of the Unit Holders, provided sufficient capital is raised to purchase that Underlying Property.

In order to invest in a Sub-Fund an Investor must first open an account in the Cash Pool by depositing a minimum of $2,500. Once an Investor has chosen the property in which they wish to invest, they can participate in a Book Build to indicate their interest in investing in the identified property. If sufficient interest is generated and if DomaCom is subsequently successful in purchasing the property, a Sub-Fund is created and the Investor’s funds are transferred from the Cash Pool to the Sub-Fund to acquire and hold the Underlying Property.

81 In response to the question, “How does investing in a Sub-Fund differ from other forms of property investment?”, it was stated:

Investing in a Sub-Fund allows an Investor to:

• choose the Underlying Property in which they seek to invest; and

• acquire a beneficial interest in the Underlying Property held by the Sub-Fund.

(Emphasis added.)

82 In section 4, which concerned management of the DomaCom Fund, it was stated that the legal relationship between an investor and the Responsible Entity was subject to “the terms of this PDS (including any relevant Supplementary PDS), the Application Form and the Constitution, as well as applicable laws including but not limited to the common law, trust law and relevant legislation”.

83 Section 6 was headed “What can I expect as a Unit Holder in a Sub-Fund?”. It was stated that the product disclosure statement provided “detailed information on the operation of the DomaCom Fund, the risks of investing and an Investor’s rights and obligations as an Investor in the DomaCom Fund”. In response to the question, “Is an Investor in a Sub-Fund a direct investor in the Underlying Property?”, it was stated in part as follows:

No. Even though an investment in a Sub-Fund simulates an investment directly in the Underlying Property, it is important to note that it is a simulation only and investors have not invested directly in an Underlying Property. Investors acquire a beneficial interest in an Underlying Property by holding Units in a Sub-Fund that holds the Underlying Property which entitles investors to receive a share of the Net Income earned in relation to the Underlying Property and, ultimately, the proceeds of sale of the Underlying Property on termination of the Sub-Fund. This is similar to, but not the same as, a direct investment in a share of the Underlying Property.

(Emphasis added.)

84 It was also stated, in section 6.4, that the “DomaCom Fund will distribute 100% of the Net Income it receives in respect of an Underlying Property as distributions to Sub-Fund Unit Holders”. In section 6.7, it was stated that each “Underlying Property will be held for the ultimate benefit of the Unit Holders in the relevant Sub-Fund”.

The Supplementary Product Disclosure Statement

85 The Supplementary Product Disclosure Statement was issued on 17 July 2015. On the front page, it stated that investors in the DomaCom Fund were invited to participate in a proposed sub-fund that planned to invest in the Burwood Property. The first page of the document stated in part as follows:

None of the Responsible Entity, DomaCom Ltd (DomaCom) or any of their directors, advisers, agents or associates in any way guarantee the performance of the Sub-Fund, any return of capital or any particular rate of return on an investment in the Sub-Fund and, to the maximum extent permitted by law, they each deny liability for any loss or damage suffered by any person investing in the Sub-Fund. Investors should note that the DomaCom Fund consists of a number of Sub-Funds. Each Sub-Fund is a separate trust and the assets of one Sub-Fund are not available to satisfy liabilities in another Sub-Fund.

This SPDS sets out information regarding the [Burwood Property] Sub-Fund, a proposed Sub-Fund of the DomaCom Fund.

The proposed Sub-Fund will only invest in a single real estate asset (referred to in this SPDS as the Underlying Property). If the capital raising program for the Underlying Property is unsuccessful, all of the Investors with an Active Bid do not accept the offer under this SPDS or the DomaCom Fund fails to purchase the Underlying Property, the Sub-Fund will not be created and an Investor’s Quarantined Funds will be released after expenses are deducted. An Investor has the opportunity to elect to participate in this proposed Sub-Fund and (if the Sub-Fund is created) obtain exposure only to the Underlying Property described in this SPDS. An investment in this Sub-Fund will not provide exposure to any other real estate investments in the DomaCom Fund.

(Emphasis in italics added.)

The Constitution as at May 2017

86 It is convenient now to refer to the Constitution as it stood as at May 2017. This document was annexure “RAL-1” to Mr Laidlaw’s affidavit of 11 May 2017. A copy of the document is at AB, Pt C, tab 90.5. The document is a consolidated version of the Constitution, incorporating various amendments that had been made over time to the Constitution.

87 The definition of “Assets” in cl 1.1 of the Constitution had been amended from the 2015 version of the Constitution. The definition as at May 2017 provided that Assets meant “cash, investments, rights, income and other property of the Fund” – the words “or a Class from time to time” had been omitted.

88 The definitions of “Class”, “Fund”, “Relevant Class”, “Relevant Liabilities”, “Relevant Scheme Assets” and “Unit” were in substantially the same terms.

89 Clause 2.1 was in substantially the same terms. Clause 2.2, however, was in different terms. The clause as at May 2017 was as follows:

Declaration of Trust

(a) The Assets shall vest in the Responsible Entity on the Commencement Date and the Responsible Entity declares that it shall hold the Assets on Trust for the Members in accordance with the terms of this Constitution.

(b) The Responsible Entity shall clearly identify the Assets as property of the Fund and hold the Assets separately from the assets of the Responsible Entity and any other managed investment scheme to the extent required by the Corporations Act.

The clause no longer stated that the Responsible Entity declared that it held “each Asset that is acquired on behalf of a Class of Unit Holders, on trust for Unit Holders in that Class”.

90 Clause 3.1 of the Constitution as at 2015 (dealing with interests and units) was now numbered cl 4.1. It was in substantially the same terms.

91 The subject matter of cl 3.4 of the Constitution as at 2015 was now dealt with, in slightly different terms, in cl 4.4. Clause 4.4 of the Constitution as at May 2017 was in the following terms:

Classes

(a) Subject to this Constitution and the Corporations Act, the Responsible Entity may create different Classes of Units in the Fund. If the Responsible Entity so determines in relation to a particular Class, the terms of issue of those Units in that Class may:

(i) have different rights, obligations and restrictions; and

(ii) provide for conversion of Units from one Class to another Class and, if the Responsible Entity so determines, change the number of Units on such a conversion.

For the avoidance of doubt, each Cash Pool is a separate Class of interest in the Fund.

(b) The Responsible Entity in making any determination of a variable properly referable to a Class under this Constitution must ensure that:

(i) any variable which relates only to a particular Class, and does not relate to other Classes, is solely referrable to the Class to which it relates; and

(ii) any variable that relates to more than one Class is apportioned between those Classes either:

(A) in the same proportions as the aggregate value of Units on issue in each Class as at the most recent Valuation Time bears to the aggregate value of Units in all Classes to which the variable relates on issue at the most recent Valuation Time; or

(B) if the methodology referred to in clause 4.4(b)(ii)(A) would result in the Responsible Entity breaching its obligation to treat Unit Holders who hold different Classes fairly in contravention of section 601FC((1)(d) of the Corporations Act, then the Responsible Entity must apportion the relevant variable that relates to more than one Class in a manner that treats Unit Holders in different Classes fairly.

(c) Notwithstanding the generality of this clause 4, the Responsible Entity must only issue Classes of Units in the following circumstances:

(i) the Relevant Scheme Assets for each Class comprise specific Assets and all proceeds and income received by the Responsible Entity in respect of, or relating to, those Assets;

(ii) the Relevant Liabilities are attributed to a Class such that they can only be met from Relevant Scheme Assets;

(iii) Relevant Scheme Assets for a Class are not encumbered in relation to Relevant Liabilities of another Class; and

(iv) the Responsible Entity is not entitled to be indemnified out of the Relevant Scheme Assets of a Class in relation to Relevant Liabilities of another Class.

(d) Within 7 days of the first issue of Units in a Class, the Responsible Entity must notify ASIC of the establishment of that Class.

(Emphasis added.)

It may be observed that cl 4.4(c) was very similar to cl 3.4(c) of the Constitution as at 2015.

92 Clause 3.6 of the Constitution as at 2015 (rights attaching to units) was now numbered 4.6. It was in substantially the same terms.

93 Clause 4.12 of the Constitution as at May 2017, which did not have an equivalent in the Constitution as at 2015, stated as follows:

For the avoidance of doubt, the Assets vested in the Responsible Entity under this Constitution give rise to a single trust, and notwithstanding any other clause in this Constitution including clauses 2.2, 4.1 and 24, no Unit or Class of Units gives rise to a distinct trust.

94 The clauses dealing with the application procedure (cl 4 of the Constitution as at 2015; cl 5 of the Constitution as at May 2017), the application price (cl 5 of the Constitution as at 2015; cl 6 of the Constitution as at May 2017), the withdrawal price of units (cl 8 of the Constitution as at 2015; cl 9 of the Constitution as at May 2017) and the valuation of assets (cl 11 of the Constitution as at 2015; cl 12 of the Constitution as at May 2017) were (for present purposes) in substantially the same terms in both versions of the Constitution.

95 The topic of income and distributions (cl 12 of the Constitution as at 2015) was now dealt with in cl 13. Clauses 13.1 to 13.4 were in different terms to the corresponding clauses in the Constitution as at 2015 (including cl 12.7, set out above). The distribution entitlement of a unit holder was now dealt with in cl 13.4. This clause set out a formula that was not referable to a class of units (unlike cl 12.7(c) of the earlier version). The clause was expressed to be “[s]ubject to the rights, obligations and restrictions attaching to any particular Unit or a Class”.

96 The clauses dealing with capital distributions (cl 12.11 of the 2015 version; cl 13.9 of the May 2017 version) and categories and sources of income (cl 12.13 of the 2015 version; cl 13.12 of the May 2017 version) were in substantially the same terms. Clause 12.19 of the Constitution as at 2015 (classes) did not appear in the May 2017 version of the Constitution.

97 The topic of the Responsible Entity’s remuneration and expenses (cl 15 of the 2015 version) was dealt with in cl 16 of the May 2017 version. Clause 16.2(a) of the May 2017 version provided that, subject to cl 16.1, the Responsible Entity could determine different fees for different classes. Clause 16.2(b) was in substantially the same terms as cl 15.2(b), which has been set out above.

98 There do not appear to be any material differences between clauses 13.2, 15.9, 18.1, 18.3, 21.2, 23(a), 23(b), 24.1, 24.2(a), 29 and 30 of the 2015 version of the Constitution and the corresponding clauses of the Constitution as at May 2017.

Key legislative provisions

99 The key legislative provisions for the purposes of the issues raised by the appeals are contained in the SIS Act. The relevant date for most of the issues is the date when the primary judge gave judgment in the Federal Court proceeding (14 December 2017). I set out the provisions as they stood at that date. There does not appear to be any material difference for present purposes between the relevant provisions as at that date and those provisions as in force during the 2015-16 and 2016-17 years of income.

100 The first two issues raised by the Federal Court Appeal concern the in-house asset rules. Part 8 of the SIS Act was headed “In-house asset rules applying to regulated superannuation funds”. (The Benson Fund was a regulated superannuation fund.) The object of the Part, as set out in s 69, was to set out rules about the level of the in-house assets of regulated superannuation funds.

101 Section 84(1) of the SIS Act relevantly provided that each trustee of a regulated superannuation fund was required to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the provisions of Div 3 of Pt 8 were complied with. Division 3 included s 82, which provided as follows:

(1) This section applies to a regulated superannuation fund.

(2) If the market value ratio of the fund’s in-house assets as at the end of:

(a) the fund’s 2000-2001 year of income; or

(b) a later year of income;

exceeds 5%, the trustee of the fund, or, if the fund has a group of individual trustees, the trustees of the fund, must prepare a written plan.

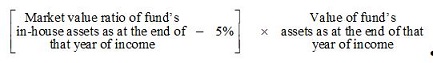

(3) The plan must specify the amount (the excess amount) worked out using the formula:

(4) The plan must set out the steps which the trustee proposes, or, if the fund has a group of individual trustees, the trustees propose, to take in order to ensure that:

(a) one or more of the fund’s in-house assets held at the end of that year of income are disposed of during the next following year of income; and

(b) the value of the assets so disposed of is equal to or more than the excess amount.

(5) The plan must be prepared before the end of the next following year of income.

(6) Each trustee of the fund must ensure that the steps in the plan are carried out.

As noted above, Aussiegolfa’s units in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) represented 7.83 per cent of the assets of the Benson Fund. Accordingly, if the investment constituted an in-house asset, the requirements of s 82 were engaged.

102 The expression “in-house asset” was defined in s 71 of the SIS Act. Section 71(1) relevantly provided as follows:

For the purposes of this Part, an in-house asset of a superannuation fund is an asset of the fund that is a loan to, or an investment in, a related party of the fund, an investment in a related trust of the fund, or an asset of the fund subject to a lease or lease arrangement between a trustee of the fund and a related party of the fund, but does not include:

…

(h) an investment in a widely held unit trust …

(Emphasis added.)

103 The expression “related trust” was defined in s 10(1) as follows:

related trust, of a superannuation fund, means a trust that a member or a standard employer-sponsor of the fund controls (within the meaning of section 70E), other than an excluded instalment trust of the fund.

104 Section 70E, referred to in that definition, relevantly provided as follows:

Control of trust

(2) For the purposes of sections 70B, 70C and 70D, an entity controls a trust if:

(a) a group in relation to the entity has a fixed entitlement to more than 50% of the capital or income of the trust; or

(b) the trustee of the trust, or a majority of the trustees of the trust, is accustomed or under an obligation (whether formal or informal), or might reasonably be expected, to act in accordance with the directions, instructions or wishes of a group in relation to the entity (whether those directions, instructions or wishes are, or might reasonably be expected to be, communicated directly or through interposed companies, partnerships or trusts); or

(c) a group in relation to the entity is able to remove or appoint the trustee, or a majority of the trustees, of the trust.

Group in relation to an entity

(3) For the purposes of subsection (2):

group, in relation to an entity, means:

(a) the entity acting alone; or

(b) a Part 8 associate of the entity acting alone; or

(c) the entity and one or more Part 8 associates of the entity acting together; or

(d) 2 or more Part 8 associates of the entity acting together.

It is accepted that the Benson Fund, together with Mr Benson’s mother and the superannuation fund of Mr Benson’s sister and her husband, had a fixed entitlement to 100 per cent of the distributable income and capital of the Burwood Sub-Fund (Aussiegolfa’s outline of submissions in the Federal Court Appeal, [12]). Mr Benson’s mother and Aussiegolfa were both “Part 8 Associates” of Mr Benson within the meaning of s 70B. It follows that, if there was a distinct trust associated with the class of units known as the Burwood Sub-Fund units, then: a group in relation to Mr Benson had a fixed entitlement to more than 50 per cent of the capital or income of the trust; Mr Benson therefore controlled the trust within the meaning of s 70E(2)(a); and the trust was a “related trust” of the Benson Fund within the definition of that expression in s 10(1).

105 As set out above, one of the exceptions to the meaning of “in-house asset” was an investment in a widely held unit trust. This concept was defined in s 71(1A) as follows:

For the purposes of paragraph (1)(h), a trust is a widely held unit trust if:

(a) it is a unit trust in which entities have fixed entitlements to all of the income and capital of the trust; and

(b) it is not a trust in which fewer than 20 entities between them have:

(i) fixed entitlements to 75% or more of the income of the trust; or

(ii) fixed entitlements to 75% or more of the capital of the trust.

For this purpose, an entity and the Part 8 associates of the entity are taken to be a single entity.

106 A further relevant provision is s 71(4). This provided as follows:

If:

(a) apart from this subsection, an asset of a fund consists of a loan, an investment, or an asset subject to a lease or lease arrangement, other than an in house asset; and

(b) the Regulator, by written notice given to a trustee of the fund, determines that the asset is to be treated, with effect from the day on which the notice is given, as if the asset were a loan to, an investment in, or an asset subject to a lease or lease arrangement with, a specified related party or related trust of the fund, including a person taken to be a standard employer-sponsor of the fund under section 70A;

then, despite paragraphs (1)(a) to (j), the asset is taken, for the purposes of this Part, to be a loan to or an investment in the related party or related trust, or an asset subject to a lease or lease agreement between a trustee of the fund and the related party.

107 Although not relied upon by either party, I note by way of context and for completeness that s 69A, headed “Sub-funds to be treated as funds”, provided as follows:

A sub-fund within a regulated superannuation fund is taken for the purposes of this Part to be a regulated superannuation fund if the sub-fund satisfies the following conditions:

(a) the sub-fund has separately identifiable assets and separately identifiable beneficiaries; and

(b) the interest of each beneficiary of the sub-fund is determined by reference only to the conditions governing that sub-fund.

108 I turn now to the legislative provisions relating to the sole purpose test. These are relevant to the third issue raised by the Federal Court Appeal. Part 7 of the SIS Act was headed “Provisions applying only to regulated superannuation funds”. The object of that Part, as set out in s 61, was to set out special rules that apply only to regulated superannuation funds. Section 62, headed “Sole purpose test”, was in the following terms:

(1) Each trustee of a regulated superannuation fund must ensure that the fund is maintained solely:

(a) for one or more of the following purposes (the core purposes):

(i) the provision of benefits for each member of the fund on or after the member’s retirement from any business, trade, profession, vocation, calling, occupation or employment in which the member was engaged (whether the member’s retirement occurred before, or occurred after, the member joined the fund);

(ii) the provision of benefits for each member of the fund on or after the member’s attainment of an age not less than the age specified in the regulations;

(iii) the provision of benefits for each member of the fund on or after whichever is the earlier of:

(A) the member’s retirement from any business, trade, profession, vocation, calling, occupation or employment in which the member was engaged; or

(B) the member’s attainment of an age not less than the age prescribed for the purposes of subparagraph (ii);

(iv) the provision of benefits in respect of each member of the fund on or after the member’s death, if:

(A) the death occurred before the member’s retirement from any business, trade, profession, vocation, calling, occupation or employment in which the member was engaged; and

(B) the benefits are provided to the member’s legal personal representative, to any or all of the member’s dependants, or to both;

(v) the provision of benefits in respect of each member of the fund on or after the member’s death, if:

(A) the death occurred before the member attained the age prescribed for the purposes of subparagraph (ii); and

(B) the benefits are provided to the member’s legal personal representative, to any or all of the member’s dependants, or to both; or

(b) for one or more of the core purposes and for one or more of the following purposes (the ancillary purposes):

(i) the provision of benefits for each member of the fund on or after the termination of the member’s employment with an employer who had, or any of whose associates had, at any time, contributed to the fund in relation to the member;

(ii) the provision of benefits for each member of the fund on or after the member’s cessation of work, if the work was for gain or reward in any business, trade, profession, vocation, calling, occupation or employment in which the member was engaged and the cessation is on account of ill-health (whether physical or mental);

(iii) the provision of benefits in respect of each member of the fund on or after the member’s death, if:

(A) the death occurred after the member’s retirement from any business, trade, profession, vocation, calling, occupation or employment in which the member was engaged (whether the member’s retirement occurred before, or occurred after, the member joined the fund); and

(B) the benefits are provided to the member’s legal personal representative, to any or all of the member’s dependants, or to both;

(iv) the provision of benefits in respect of each member of the fund on or after the member’s death, if:

(A) the death occurred after the member attained the age prescribed for the purposes of subparagraph (a)(ii); and

(B) the benefits are provided to the member’s legal personal representative, to any or all of the member’s dependants, or to both;

(v) the provision of such other benefits as the Regulator approves in writing.

(1A) Subsection (1) does not imply that a trustee of a regulated superannuation fund is required to maintain the fund so that the same kind of benefits will be provided:

(a) to each member of the fund; or

(b) in respect of each member of the fund.

(2) Subsection (1) is a civil penalty provision as defined by section 193, and Part 21 therefore provides for civil and criminal consequences of contravening, or of being involved in a contravention of, that subsection.

(3) An approval given by the Regulator for the purposes of subsection (1) may be expressed to relate to:

(a) a specified fund; or

(b) a specified class of funds.

The Federal Court Reasons

109 The primary judge outlined the factual background at [1]-[18] of the Federal Court Reasons. This part of his Honour’s reasons has been substantially reproduced above.

110 His Honour noted, at [12], that there was some uncertainty about which versions of the Constitution and of the product disclosure statement governed the rights in question. Noting the evidence of Mr Laidlaw to the effect that the units representing the Burwood Sub-Fund did not exist until after acquisition of the Burwood Property, which occurred between July and August 2015, the primary judge considered the relevant terms of the Constitution to be those that were operative as at July 2015 and the relevant product disclosure statement to be the June 2015 Product Disclosure Statement. However, perhaps because of the conflicting dates in the footers of the documents or because of the way the material was presented, his Honour then referred to provisions of the Constitution as it stood in May 2017 as if this was the version of the Constitution as at July 2015.

111 At [19] of the Federal Court Reasons, the primary judge referred to the relevant provisions of the SIS Act concerning in-house assets. His Honour identified, at [20], the question whether the units were an investment in a “related trust” of the Benson Fund. His Honour noted that Aussiegolfa accepted that the other holders of the units in the Burwood Sub-Fund, namely Mr Benson’s mother and his sister’s superannuation fund, were Part 8 associates for the purposes of s 70E of the SIS Act. Thus, his Honour said, there was a group within the meaning of s 70E in relation to Aussiegolfa. His Honour noted Aussiegolfa’s submissions that the group did not have fixed entitlements to more than 50 per cent of the capital or income of the DomaCom Fund because Aussiegolfa, together with Mr Benson’s mother and his sister’s superannuation fund, held less than one per cent of the units in the DomaCom Fund. His Honour noted that the same was not true, however, if the relevant trust was the Burwood Sub-Fund rather than the DomaCom Fund.

112 The primary judge held, at [21], that, despite a number of provisions of the Constitution that were consistent with the DomaCom Fund being a single trust, “the Constitution created the Burwood Sub-Fund as a separate trust in respect of which a group in relation to the Benson Fund had a fixed entitlement to more than 50 per cent of the capital or income of the trust”. His Honour’s reasons for this conclusion, at [21]-[22], were as follows (noting that the references to clauses of the Constitution are to the Constitution as at May 2017):

21 … Clause 5.3 of the Constitution required the application by each member of the group, including Aussiegolfa, for an interest in units in conformity with the relevant disclosure documents. Clause 5.1 permitted the responsible entity to invite applications, and both the product disclosure statement dated 24 June 2015 and the supplementary product disclosure statement dated 17 July 2015 were invitations to participate in a proposed Sub-Fund with plans to invest in the Burwood property. The supplementary product disclosure statement specifically stated, as previously mentioned, that each Sub-Fund was “a separate trust” with the assets of one Sub-Fund not being available to satisfy liabilities in another Sub-Fund. Even putting that statement aside, however, the terms of the Constitution, consistently with the product disclosure statement and the supplementary product disclosure statement (which were both contemplated by the Constitution), require the conclusion that a trust was created in respect of the Burwood property held by the responsible entity through DomaCom.

22 Clause 4.1 expressly divided the “beneficial interest” in the DomaCom Fund as between interests in the Cash Pool and units (whatever else may have been intended by clause 4.12). Part of the beneficial interest in the fund was, thus, divided into units such that the responsible entity had separate fiduciary duties to the unit holders of the Burwood Sub-Fund. Clause 4.4 permitted the responsible entity to create different classes of units with distinctly different rights, obligations and restrictions and, for the avoidance of doubt, it was made clear that each Cash Pool was a separate class of interest in the fund. The units issued by the responsible entity could only be issued in respect of specific assets and all proceeds and income received by the responsible entity in respect of those assets were to be dealt with as the relevant scheme assets for the class comprising those assets. Each sub-fund related to an identifiable item of property which was held by the trustee on trust pursuant to the specific terms of the Constitution referable to that asset. The income and distributions of the fund were governed by clause 13 of the Constitution which provided that the whole of the net income in respect of each sub-fund is received by the holders of the units referrable to the sub-fund in accordance with a formula. The responsible entity may have trust obligations to other beneficiaries in respect of other property but it owes no fiduciary duties to the other beneficiaries in respect of the Burwood property which it holds for the benefit of the unit holders of the Burwood Sub-Fund. The rights and entitlements of the units in the Burwood Sub-Fund constitutes 100% of the distributable income from the Burwood property. The unit holders of the Burwood sub-fund are entitled to 100% of the capital relating to the Burwood property and no other member of DomaCom has an entitlement to the income or capital in relation to the Burwood property. Although clause 19.1 provided that the responsible entity had a general entitlement to indemnity, clause 4.4(c)(iv) provided that the responsible entity was not entitled to be indemnified out of the relevant scheme assets of a class in relation to relevant liabilities of another class.

113 The primary judge held, at [23], that the “conclusion that the Burwood Sub-Fund is a separate trust carries the consequence that it is not a widely held unit trust within the meaning of s 71(1)(h)”.

114 Accordingly, the primary judge concluded that Aussiegolfa’s units in the DomaCom Fund (or the Burwood Sub-Fund) constituted an in-house asset.

115 The primary judge then considered the issue relating to the sole purpose test. His Honour stated, at [29], that it was a question of fact whether the sole purpose test would continue to be satisfied upon the grant of a lease to Ms Benson, referring to Randwick Corporation v Rutledge (1959) 102 CLR 54 at 94; Ryde Municipal Council v Macquarie University (1978) 139 CLR 633 at 644-645; and News Limited v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited (2003) 215 CLR 563 at [18].

116 His Honour concluded that entry into the lease with Ms Benson would cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test. His Honour reasoned as follows at [30]-[31]:

30 A factual difficulty for Aussiegolfa in the present case about whether the leasing to Ms Benson causes Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test arises from the candidly frank statement by Mr Benson that the use of the Burwood property by a lease to his daughter was to test “the related party use of residential property” within self-[managed] superannuation funds. That statement bears upon an evaluation of the facts to determine whether the Benson Fund was maintained solely for the purposes contemplated by s 62(1) or also for the not incidental, but independent and collateral, purpose of providing housing for Ms Benson. An available inference from the evidence, including the frankly candid statement by Mr Benson, is that an investment in units in the DomaCom Fund was for the collateral purpose of the superannuation fund being used to provide accommodation to a person related to the superannuation fund.

31 Even without the inference from Mr Benson’s statement, however, the facts do not support the conclusion that the leasing to Ms Benson would not cause Aussiegolfa to breach the sole purpose test. A high standard was adopted by s 62 of the SIS Act as an important pillar to ensure that self-managed superannuation funds achieve the objectives of providing retirement benefits and not current day use or benefits. A collateral purpose of providing housing for a relative is not amongst the core purposes, or the ancillary purposes, in s 62 and is inconsistent with the underlying objective of not providing present benefit or use to members of a self-managed superannuation fund or to relatives of the members. In Case 43/95 [1995] 95 ATC 374 the Administrative Appeals Tribunal said at [24]:

24. In addition to the above, it may be that there are isolated incidents which, viewed in the overall context of the way in which a superannuation fund is being maintained, are so incidental, remote or insignificant, that they cannot, having regard to the objects sought to be achieved by the Act, be regarded as constituting a breach of the sole purpose test. Such incidents will be rare. The legislature, by adopting the “sole purpose” test, has expressly determined that a strict standard of compliance should be adhered to. Under the Act, the test requires more than the presence of a dominant or principal purpose in the maintenance of a superannuation fund – it requires an exclusivity of purpose commensurate with that purpose being the “sole purpose”. In the instant case, in the absence of other relevant factors, the fact that Mr A and his friend were enabled as the result of the investment by the fund, after paying the annual subscription fee, to play golf could by itself be regarded as so incidental or remote as to not amount to an infringement of the test. However, given that there were other relevant factors surrounding the way in which that asset was maintained and viewed in the context of the findings reached by the tribunal with respect to other investments made by the fund – in the units in Mr A’s family trust and in the Sorrento property – a circumstance which in isolation may be insignificant or remote becomes more significant. Having regard to the totality of the way in which the three nominated assets – the shares in Z Pty Ltd, the Swiss chalet and the Sorrento property – were maintained, the tribunal is satisfied that Mr A had a second purpose, namely to make the assets available for his use and the use of his family and friends so that it could not be said that the “sole purpose” in the maintenance of the assets was for the benefit of the members of the fund. The fact that other assets of the fund may not have been utilised for a purpose other than a purpose to give benefits to the members has been considered by the tribunal but does not affect its decision.

The facts in that case are plainly not the same as those in this proceeding, however, its reasoning is apt and broadly applicable. There may be circumstances in which a lease to a related party would not breach the sole purpose test but the evidence in this case is that the purpose of the investment by Aussiegolfa in student housing accommodation through DomaCom was, in part, to provide housing to Mr Benson’s daughter. The Commissioner relied upon a number of other facts for that conclusion which were unpersuasive (such as the fact that Mr Benson was providing a guarantee and might be called upon to provide economic support to his daughter), but in this case it is sufficient that a purpose of the investment by Aussiegolfa in DomaCom was to provide accommodation to a relative of Mr Benson. The conclusion that the sole purpose test would be breached by the lease to Ms Benson is not also required by the fact that Mr Benson gave a parental guarantee, or was the person who forwarded the application for his daughter to the agent, but is required by the fact that a purpose of Aussiegolfa in acquiring the units in the DomaCom Fund was to provide accommodation to a relative of [Mr] Benson.

(Emphasis added.)

117 It followed that his Honour declined to make the declarations sought by Aussiegolfa and dismissed the proceeding.

The AAT Reasons

118 As noted above, the proceeding in the Tribunal was an application by Aussiegolfa for review of the Determination. The Tribunal outlined the background facts and legislative provisions at [1]-[14] of its reasons (the AAT Reasons).

119 After setting out s 71(4) of the SIS Act, the Tribunal concluded, at [15], that “the objective condition that needs to exist before a determination can be made under s 71(4)(b) is absent because the reasons and conclusions in the Federal Court proceedings would also lead the Tribunal to decide that the investment by Aussiegolfa in DomaCom was in units which are assets that consist of an in-house asset”. It followed that the Determination was to be set aside.

120 However, the Tribunal also went on to indicate that, if Aussiegolfa’s units did not constitute an in-house asset, the Tribunal would have affirmed the Determination. The Tribunal stated at [15]-[16]:

15 … It is desirable, however, to say that the Commissioner’s determination would have been affirmed if the asset had been found to have consisted of an investment other than an in-house asset. That is because the investment would be in substance, and in practical effect, the same as an in-house asset and within the purpose sought to be achieved by limiting investments in in-house assets to 5%, even though it might in legal form not be an in-house asset.

16. The primary policy objective of the superannuation investment rules was described in the explanatory memorandum accompanying the 1999 amendments as follows:

The primary policy objective is to ensure that the investment practices of superannuation funds are consistent with the government’s retirement incomes policy. That is, superannuation savings should be invested prudently, consistently with the SIS requirements, for the purpose of providing retirement income and not for providing current day benefits.