FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93

ORDERS

NSD 1656 of 2017 | ||

ALDI FOODS PTY LTD ACN 086 210 139 First Appellant ALDI PTY LTD ACN 086 493 950 Second Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons within seven (7) days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 I have read the reasons to be published of Perram J. I agree with the orders proposed by his Honour and, subject to some additional remarks, I agree with the substance of his reasoning.

Appellate review

2 I agree with what Perram J has said about appellate review. This Court is bound, of course, by High Court authority. I agree with what Perram J says about Robinson Helicopter Company Inc v McDermott [2016] HCA 22; 331 ALR 550. The Court (French CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ) said the following at 558-559 [43]:

The fact that the judge and the majority of the Court of Appeal came to different conclusions is in itself unremarkable. A court of appeal conducting an appeal by way of rehearing is bound to conduct a “real review” [Fox at [25] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ] of the evidence given at first instance and of the judge's reasons for judgment to determine whether the judge has erred in fact or law. If the court of appeal concludes that the judge has erred in fact, it is required to make its own findings of fact and to formulate its own reasoning based on those findings [Devries v Australian National Railways Commission (1993) 177 CLR 472 at 479-481; 112 ALR 641 at 646-7 per Deane and Dawson JJ; Fox at [29] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ; Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Ltd (ACN 007 101 715) (2010) 241 CLR 357; 270 ALR 204; [2010] HCA 31 at [76] (Miller & Associates) per Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ]. But a court of appeal should not interfere with a judge's findings of fact unless they are demonstrated to be wrong by “incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony” [Fox at [28] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby], or they are “glaringly improbable” or “contrary to compelling inferences” [Fox at [29]. See also Miller & Associates at [76]]. In this case, they were not. The judge's findings of fact accorded to the weight of lay and expert evidence and to the range of permissible inferences. The majority of the Court of Appeal should not have overturned them.

(footnotes inserted)

3 The footnotes to the paragraph and the balance of the judgment (see especially at 562 [56]) make it plain that no departure from long-standing principle discussed in Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; 142 CLR 531, Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 and State Rail Authority (NSW) v Earthline Constructions Pty Ltd (in liq) [1999] HCA 3; 73 ALJR 306 was intended. The references by the Court that “a court of appeal should not interfere with a judge’s finding of fact unless they are demonstrated to be wrong by ‘incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony’ or they are ‘glaringly improbable’ or ‘contrary to compelling inferences’” should be understood by reference to the footnotes. The references to Fox v Percy 214 CLR at 128 [28] and [29] are plainly to findings of fact reached after assessing competing witnesses for their reliability and credibility. The reference to Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Ltd [2010] HCA 31; 241 CLR 357 at 381 [76] is an indirect reference, in the context of fact-finding involving witnesses, to Fox v Percy 214 CLR at 125-128 [23]-[29]. These latter references to Fox v Percy are important because they recognise the importance of the advantages of the trial process discussed by Kirby J in SRA v Earthline 73 ALJR at 330 [89]-[91] and adopted by Gleeson CJ, Gummow J and Kirby J in Fox v Percy 214 CLR at 125-126 [23]. The whole of 124-129 [20]-[31] of Fox v Percy is important and I do not read the Court in Robinson Helicopter 331 ALR as saying at 558-559 [43] that any finding of fact made by a trial judge can only be interfered with if the expressions referred to above and derived from Fox v Percy are satisfied. The findings of fact of the trial judge in Robinson Helicopter were made after a trial of five weeks in which close to 20 witnesses gave oral evidence, whose evidence had to be assessed, balanced and evaluated as the case unfolded. The trial judge had the advantages of seeing lay and expert witnesses in assessing their credit and reliability, and he also had the advantages of the kind discussed in SRA v Earthline including “the unique benefit of viewing two helicopters of the kind which crashed … [and] … the opportunity to consider all of the evidence in its totality and to reflect upon its interaction”: 331 ALR at 562 [57].

4 The application of the principles of appellate review to evaluative assessments has been the subject of discussion in a number of cases in this Court. The question often arises in intellectual property appeals. In Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424, with the agreement of Drummond and Mansfield JJ, I discussed the question of appellate review when matters of impression and judgment are concerned (so often relevant in intellectual property appeals) at 117 FCR 437-438 [28]-[29] (set out at [7] below), as part of a discussion of the nature of error at 117 FCR 435-438 [24]-[30]. Branir has been followed on this question on a significant number of occasions by the Full Court of this Court, and in other intermediate appellate courts. See, for example: TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 146; 118 FCR 417 at 441-442 [108]; Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157; 234 FCR 549 at 564-567 [50]-[54]; Argus Real Estate Holdings Pty Ltd v Lyristakis [2002] FCAFC 256 at [8]; Walcan Pty Ltd v Superior Coffee & Cakes Pty Ltd [2003] FCAFC 14 at [20]-[21]; Commissioner of Taxation v Amway of Australia Limited [2004] FCAFC 273; 141 FCR 40 at 51-52 [35]; Poulet Frais Pty Ltd v The Silver Fox Company Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 131; 220 ALR 211 at 217-221 [35]-[47] and in particular the restatement of the matter in [46]; Sampi on behalf of the Bardi and Jarwi People v State of Western Australia [2010] FCAFC 26; 266 ALR 537 at 541 [7]; EMI Songs Australia Pty Ltd v Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 47; 191 FCR 444 at 507 [259]-[260]; Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 130; 197 FCR 67 at 79-80 [33]-[34]; Rafferty v Madgwicks [2012] FCAFC 37; 203 FCR 1 at 50 [193]-[195]; Ron Englehart Pty Ltd v Enterprise Constructions (Aust) Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 4; 95 IPR 64 at 73 [53]; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 104; 247 FCR 570 at 578-579 [47]; Australian Olympic Committee Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited [2017] FCAFC 165 at [115]; Costa v Public Trustee (NSW) [2008] NSWCA 223 at [14]-[15]; Sapina v Coles Myer Ltd [2009] NSWCA 71 at [25]; Weston in his capacity as special purpose liquidator of One.Tel Ltd (in liq) v Publishing and Broadcasting Ltd [2012] NSWCA 79; 88 ACSR 80 at 116 [157]; Spata v Tumino [2018] NSWCA 17 at [141]; H v P [2011] WASCA 78 at [47]; X v Y [2015] WASCA 70 at [61]; Gaundar v Hogan [2014] ACTCA 4 at [5]; Australian Capital Territory v Crowley [2012] ACTCA 52; 273 FLR 370 at 373 [5]; Pingel v Toowoomba Newspapers Pty Ltd [2010] QCA 175 at [36]; Mango Boulevard Pty Ltd v Spencer [2010] QCA 207 at [154].

5 In Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 138; 87 FCR 415, Weinberg J said at 442 [119], in the context of questions of impression and evaluative judgment (there involving a question of copyright in industrial plans), that the appellate court must be persuaded that the judgment below is erroneous in principle, or plainly and obviously wrong, relying on what Lord Bridge of Harwich said in George Mitchell (Chesterhall) Ltd v Finney Lock Seeds Ltd [1983] 2 AC 803 at 816 in dealing with the assessment of whether a contractual provision was “fair and reasonable”.

6 The use of the expression and words “plainly and obviously”, “plainly” and “obviously” when describing error are apt to cause difficulty. In this respect, see the discussion in Gett v Tabet [2009] NSWCA 76; 254 ALR 504 at 561-567 [274]-[301] in the context of departure from earlier authority. Such adjectival or adverbial aphorisms or formulae are apt to oversimplify what is nuanced or subtle. With respect to those who have expressed themselves differently (Metricon Homes Pty Ltd v Barrett Property Group Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 46; 248 ALR 364 at 367-368 [17]-[20] and Optical 88 197 FCR at 79 [32]), the test of “plainly and obviously wrong” is not semantically or substantively the same as that which was said in Branir at 437-438 [28]-[29].

7 The Full Court in Optical 88 correctly, if I may respectfully say so, eschewed, at 79-80 [33], the use of “sound bites” such as “plainly or [sic: and] obviously wrong” (taken from Eagle Homes) or “sufficiently clear difference of opinion” (taken from Branir). The Court said at 197 FCR 79-80 [33]:

The second point is that the task of this appellate Court is a complex one. It cannot be captured by brief “sound-bites” such as “plainly or obviously wrong” or “sufficiently clear difference of opinion”. It is an approach which requires consideration of several principles, not just one. This approach is best explained by Allsop J in Branir at [28]-[29]:

28 … First, the appeal court must make up its own mind on the facts. Secondly, that task can only be done in light of, and taking into account and weighing, the judgment appealed from. In this process, the advantages of the trial judge may reside in the credibility of witnesses, in which case departure is only justified in circumstances described in Abalos v Australian Postal Commission; Devries v Australian National Railways Commission and SRA v Earthline. The advantages of the trial judge may be more subtle and imprecise, yet real, not giving rise to a protection of the nature accorded credibility findings, but, nevertheless, being highly relevant to the assessment of the weight to be accorded the views of the trial judge. Thirdly, while the appeal court has a duty to make up its own mind, it does not deal with the case as if trying it at first instance. Rather, in its examination of the material, it accords proper weight to the trial judge’s views. Fourthly, in that process of considering the facts for itself and giving weight to the views of, and advantages held by, the trial judge, if a choice arises between conclusions equally open and finely balanced and where there is, or can be no preponderance of view, the conclusion of error is not necessarily arrived at merely because of a preference of view of the appeal court for some fact or facts contrary to the view reached by the trial judge.

29 The degree of tolerance for any such divergence in any particular case will often be a product of the perceived advantage enjoyed by the trial judge. Sometimes, where matters of impression and judgment are concerned, giving “full weight” or “particular weight” to the views of the trial judge might be seen to shade into a degree of tolerance for a divergence of views [various authorities] … However, as Hill J said in Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Chubb Australia Ltd “giving full weight” to the view appealed from should not be taken too far. The appeal court must come to the view that the trial judge was wrong to interfere. Even if the question is one of impression or judgment, a sufficiently clear difference of opinion may necessitate that conclusion.

(citations omitted)

8 There is no circularity in this approach. It is the description of when an assessment of difference is adjudged to be sufficient to be characterised as error, leading to the obligation on the appeal court judges to give effect to their own judgment. It is the nuanced area where the statutory entitlement to a rehearing and the need to demonstrate error interrelate, as discussed otherwise in Fox v Percy.

9 A test of “plainly and obviously wrong” (whatever its precise content) is blunt and lacks nuance. It invites the setting of a standard of appellate review higher than it should be, by its formulaic false simplicity and false clarity.

10 Branir in this respect should be followed and not wrongly paraphrased into formulaic simplicity by the use of the phrase “plainly and obviously wrong”. Branir has been followed on many occasions. The volume of intellectual property cases in this Court calls for a clear and consistent approach. That approach, as set out in Branir and in the cases that have applied it, has within it (see 117 FCR at 437-438 [28]-[29]) the very helpful judgment of Hill J in Commissioner of Taxation v Chubb Australia Ltd [1995] FCA 147; 56 FCR 557 at 572-573 which used as a source the remarks of Gibbs CJ in a copyright appeal in SW Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems [1985] HCA 59; 159 CLR 466 at 478.

The misleading or deceptive conduct issues

11 I agree with the reasons of Perram J that the use of the word NATURALS on the packaging was not a representation that the products were made either wholly or substantially from natural ingredients and that the appellant did not thereby engage in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

12 As to the performance benefits claims, I agree with Perram J that there should be no interference with the primary judge’s conclusions. I would do so, however, not because I have a difference of view that is insufficiently strong to lead to a conclusion of error on her Honour’s part, but because I agree with her Honour. Looked at overall, I too (cf the primary judge’s reasons at [494]) have little doubt that ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer would infer that it was the argan oil which was wholly or largely responsible for the touted benefits. Given my agreement as to the orders, I do not consider that further elucidation is required other than by reference to, and agreement in, the reasons of the primary judge.

The trade mark issues

13 The meaning and application of s 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) was not a matter of controversy on appeal. The most recent and convenient statement of the relevant principles can be found in the decision of Yates J in Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks [2014] FCA 1304; 227 FCR 511 at 512-518 [5]-[21].

14 The terms of s 41(4) are to be understood as referable to being unable to find that the trade mark is capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from those of others. If one is able to find such affirmatively from the inherent adaptability of the mark to distinguish the goods or services from those of others, that must be the end of the question. If one is not able to find such affirmatively from the inherent adaptability of the mark to distinguish the goods or services from those of others, that is either because there is to some extent some inherent adaption (and s 41(5) applies) or there is no inherent adaption (and s 41(6) applies).

15 The primary judge’s enquiry after her Honour had examined inherent adaption was framed by s 41(5). Thus, her Honour is to be taken to have found some inherent adaption to distinguish.

16 I agree with Perram J, and for the reasons his Honour gives, that the primary judge erred in not concluding that the trade mark was not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of others.

17 I would only add the following. The fact is that MOROCCANOIL is a word with the natural English meaning of Moroccan oil or oil of, or from, Morocco. This could be used to describe, for this class of goods, the ingredient in a hair care product. There was a distinct likelihood therefore that traders, actuated by proper motives, would think of the words “Moroccan oil” and use them in connection with their goods. The evidence revealed that there were a number of products in Australia at the relevant time using argan oil, some designating its origins in Morocco. Moroccan oil may not have meant argan oil, but it plainly meant Moroccan oil. That is what the letters said – MOROCCANOIL. Once it was established that, for practical purposes, argan oil was sourced in Morocco and that it was a substance used in hair care products, the honest and proper use of the words “Moroccan oil” by traders is highly likely in connection with such goods.

18 The question of capability to distinguish should then have been assessed under s 41(6), not s 41(5). I agree with the conclusion and reasons of Perram J concerning this enquiry. In the light of the use of the words by other traders in connection with their hair care products, of the clear natural meaning of the words (or word when used as one group of letters) and of the additional stylisation in the use by the respondent I agree that the respondent did not demonstrate that because of its use of MOROCCANOIL between 2009 and 2011 the trade mark (that is the word, not the brand usage with the get up) did distinguish its goods as being those of it from those of others, in the sense discussed by Jacob J in British Sugar Plc v James Robertson & Sons Ltd [1996] RPC 281.

I certify that the preceding eighteen (18) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop. |

Associate:

Dated: 22 June 2018

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PERRAM J:

I. Introduction

19 This appeal raises two questions: should a trade mark proceed to registration and did the manner in which the Appellants sold some hair care products constitute misleading or deceptive conduct. The Appellants (Aldi) operate a well-known supermarket chain specialising in less expensive household products. It has operated under the slogan ‘Like brands, only cheaper’. The Respondent (Moroccanoil) is an Israeli company which specialises in the production and distribution of hair and skin care products. The principal ingredient in many of its products is argan oil which is made from the nuts of the argan tree (Argania Spinosa). Argania Spinosa is found largely in Morocco and is a spiny tree the nuts of which are used in Morocco for a number of purposes including as a hair and beauty product.

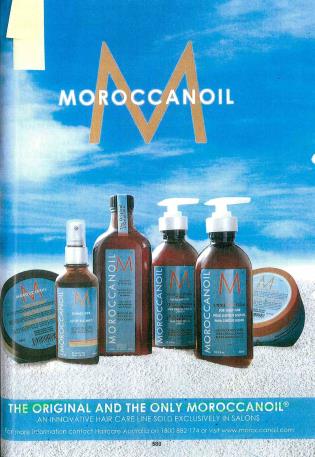

20 Since its inception in 2007, the Respondent has marketed its products under the name MOROCCANOIL. It has imported these products into Australia under the same name since September 2009. It has done so in turquoise packaging under a variety of similar get-ups each featuring, in a variety of disparate yet similar ways, the word MOROCCANOIL. One of its most popular products – the hair oil treatment – was sold in a brown glass bottle, which was described in submissions as ‘apothecary-style’, and packaged in a turquoise box. The evidence before the primary judge included testimony from hair stylists who thought that this packaging was unique and even, in one case, ‘iconic’. The products were also very expensive. A 100ml bottle of the Respondent’s hair oil treatment, for example, sold for between $49.50 and $59.95 across the period 2009 to 2015. And, in the same period, its shampoo and conditioner products each sold for between $35.95 and $43.95. There was corresponding evidence before the primary judge that the Respondent’s products were ‘luxurious’ and ‘high-end’ and the Appellants submitted at trial that the Respondent’s products were part of a ‘salon-only professional high-end prestige brand’. The hair oil treatment product looked like this from 2012:

21 Of particular note is the brown, ‘apothecary-style’ bottle, the turquoise (nearly aqua) packaging, the word MOROCCANOIL and, because it will be later relevant, the bronze-coloured capital letter ‘M’.

22 The argan oil products proved remarkably, perhaps even wildly, successful. By September 2010 the products had created a ‘buzz’ in the hair care industry and were reportedly ‘flying off the shelves’. This reflected an expensive and determined marketing campaign on the Respondent’s part and resulted in revenues which can only be described as very impressive. It was said in argument during the appeal, and was not in dispute, that at the relevant times the Respondent’s products had been ‘on-trend’ which the Macquarie Dictionary describes as meaning ‘the trendy thing of the moment’.

23 Into this picture of entrepreneurial triumph then came the Appellants. Their business practice is to sell very inexpensive products under house brands which resemble, but not too much, other more expensive products. The Appellants’ business practice treads the delicate line between reminding consumers of the more expensive product whilst not misleading them into thinking the product they are buying is, or is associated with, that product.

24 By about 2011 the Appellants had become aware that argan oil products were ‘on-trend’ and decided to produce their own range of argan oil hair care products. By that time, there were already a number of argan oil hair care products on the market apart from the Appellants’. The primary judge noted a number of such competitor products including the alluringly named ‘Pure Oil of Marrakesh’, ‘Maijan Moroccan Argan Oil’ and many others besides. In any event, the end result of the Appellants’ decision was the production by them of a range of hair care products containing argan oil.

25 As it happens, the Appellants had already marketed a range of hair care products under their house brand PROTANE. They also maintained a sub-brand of that house brand called NATURALS. The Appellants decided to market their various argan oil products under the PROTANE NATURALS range with each product being described as a ‘Moroccan Argan Oil’. Typical of these were the shampoo and conditioner products which in their most recent manifestation looked like this:

26 As the primary judge observed, the shampoo and conditioner products ‘bear no resemblance, let alone a deceptive resemblance, to the [Respondent’s] products’. Perhaps not so clear, however, was the situation which obtained in the case of the Appellants’ hair treatment oil product which looked like this:

27 Even in the case of the treatment oil, however, the primary judge did not think the Appellants’ product was deceptively similar to the Respondent’s product. The passing off case and its associated misleading or deceptive conduct case therefore failed in their entirety. No appeal is brought from that conclusion. For completeness, it should be noted that there were also a large number of other products involved at first instance but the products set out above will suffice for dealing with the issues which now arise on the appeal. No reference therefore need be made to the other products with which the primary judge was assailed such as the Appellants’ argan oil infused hairbrushes or their argan oil infused hairdryer.

28 The primary judge did find against the Appellants, however, in relation to two quite different misleading or deceptive conduct cases. First, her Honour concluded that the sub-brand NATURALS was apt to convey to consumers that the product being sold was made from, or was substantially made from, natural products. An analysis of the various products showed that this was not so if water was not treated as a natural product and her Honour was satisfied that it should not be so treated. It followed that by marketing the products in that way the Appellants had they had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct. Her Honour found breaches of ss 18(1) and 29(1)(a) of Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘ACL’). It is convenient to refer to this set of claims as the ‘Naturals claims’.

29 Secondly, the primary judge accepted the Respondent’s contention that the performance benefits claimed for the products were misleading. The product claims for the Appellants’ three products were not entirely the same. For the Moroccan Argan Oil shampoo and the conditioner products the claims made on the front of both products were:

Helps strengthen hair and restore shine;

Helps protect hair from styling, heat and UV damage;

Leaves hair soft and silky;

Sulfate free.

30 In the primary judge’s assessment of this material (at [490]) her Honour omitted the reference to ‘Sulfate free’. Her Honour did not err, however, as her Honour observed only that the claims made for the products ‘included’ the first three claims.

31 On the back of the shampoo product there also appeared this claim:

‘PROTANE® Naturals Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo is a hydrating shampoo for all hair types. It strengthens hair, restores shine and helps protect hair from heat damage and UV damage. Your hair will feel heathier, soft and silky, making it easier to style. Gentle enough to use everyday.’

32 A similar statement appeared on the back of the conditioner product.

33 In relation to the hair treatment product the statements on the front of the package were:

Helps strengthen hair;

Instantly absorbed without leaving any residue;

Restores shine and provides long term conditioning;

Alcohol free.

34 On the rear of the product this statement appeared:

‘PROTANE® Naturals Moroccan Argan Oil is a hydrating treatment for all hair types. It is instantly absorbed into the hair to provide long term conditioning, restore shine and strengthen the hair. Used regularly your hair will be left looking shiny and healthy.’

35 The primary judge also noted that similar claims were made on the cardboard cartons in which the oil treatment was delivered and sometimes displayed.

36 Her Honour identified the performance claims said to flow from all of this packaging as follows:

Strengthening hair and restoring shine;

When used regularly, leaving the hair shiny and healthy; and

Protects from styling, heat and UV damage.

37 Her Honour concluded that these touted benefits would be understood by the relevant class of consumers as implying that they resulted from the presence of argan oil in the products. There was evidence before the primary judge of the amount of argan oil in the Appellants’ products and the inability of that amount of argan oil to contribute to the claimed benefits. Her Honour accepted this evidence and concluded that the Appellants had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct. Her Honour found breaches of s 18(1). To be clear, her Honour did not find that the shampoo and conditioner did not have the asserted performance qualities. Rather, her Honour’s finding was the more subtle conclusion that such qualities did not derive from the presence of argan oil.

38 The Appellants appeal from both of those conclusions. For the reasons which follow below, the appeal in relation to the Naturals claims should be allowed but dismissed in relation to the Performance Benefits claims.

39 At trial, there were also a number of issues relating to trade marks. No appeal is brought from the primary judge’s determination of the trade mark issues save for one which concerns the Respondent’s attempts to register the word MOROCCANOIL as a trade mark. It had sought to register that word as a word mark in class 3 of the register in relation to:

‘Hair care products, including oil, mask, moisture cream, curly hair moisture cream, curly hair mask, curly and damaged hair mask, argan and saffron shampoo, hair loss shampoo, dandruff shampoo, dry hair shampoo, gel, mousse, conditioner, hair spray.’

40 An application was lodged with the Registrar of Trade Marks on 7 December 2011 and accepted by the Registrar for possible registration on 18 October 2012. However, the Appellants filed a notice of opposition to the registration of the trade mark and on 9 October 2015 a delegate of the Registrar refused registration of the mark on the basis that it was not inherently adapted to distinguish the Respondent’s goods. The Respondent appealed that conclusion to the Federal Court and that appeal was heard by the primary judge at the same time as the misrepresentation case. Her Honour concluded that the appeal should be upheld and that the mark should proceed to registration. It is from that conclusion that the Respondent now appeals.

41 In a nutshell the first of the trade mark issues on the appeal is whether MOROCCANOIL really just means ‘oil from Morocco’ so that it does not distinguish the Respondent’s goods from the goods of other traders selling argan oil based hair care products. Here the contention is similar to the observation that a soap product marketed by a trader under the name SOAP would not be distinctive of that trader and its registration would hardly be fair to other traders who sold soap. The second issue concerns whether, despite such concerns, the Respondent’s use of the word MOROCCANOIL means that the word became distinctive of the Respondent’s products even if it was not originally so.

42 In addition to the above matters, Respondent’s written submissions in both appeals raise an important question of principle. It concerns the nature of an appeal to this Court from an evaluative conclusion by a primary judge such as whether particular packaging is misleading. These reasons therefore deal with the following issues:

1. The nature of the appeal (Section II);

2. Whether the Naturals claims were conveyed (Section III);

3. Whether the Performance Benefits claims were conveyed (Section IV);

4. Whether MOROCCANOIL is capable of being registered as a trade mark (Section V).

II. The Nature of the Appeal

43 In this case the primary judge made a number of findings which were evaluative in nature. Some of these were that the packaging of the Appellants’ argan oil shampoo and conditioner and hair oil misleadingly conveyed, first, a representation that the relevant products substantially comprised natural products; and secondly, that the claimed benefits of the products resulted from the presence in them of argan oil. Another evaluative conclusion was reached in the trade mark appeal when her Honour found that the way the word MOROCCANOIL had been used by the Respondent made it capable of distinguishing the Respondent’s goods.

44 In relation to each of these findings, there is now no challenge to the primary facts upon which they rest. There is, for example, no doubt as to what the Appellants’ packaging looked like. Her Honour’s conclusions on these matters therefore involved the Court below in an evaluative assessment of the nature of the evidence.

45 How should this Court in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction approach the review of such findings? One begins with the proposition that this Court’s appellate jurisdiction involves an appeal by way of rehearing (Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees Pty Ltd (No 2) [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424 (‘Branir’) at 434-435 [20] per Allsop J, Drummond and Mansfield JJ agreeing). Next, it is established that in an appeal by way of rehearing what is involved is the correction of error (Branir at 435 [22]). Error is not demonstrated merely because the appellate court disagrees with the primary judge. At the risk of stating the obvious, error is demonstrated where it is shown that some aspect of the trial judge’s reasoning is wrong. How the trial judge’s reasoning may be shown to be wrong depends on what that reasoning is about (Branir at 435 [24]). At one extreme, where no deference at all is shown to a trial judge’s conclusions, are errors of law. An appellate court is not influenced in its view of the law by the conclusions of a trial judge and, in this case, mere disagreement on the part of the appellate court with the trial judge will justify the conclusion that an error has been made.

46 At the other extreme are a trial judge’s finding of fact where the credibility of witnesses is involved. In such cases, it is accepted that the trial judge enjoys very considerable advantages over an appellate court by reason of having seen the witnesses and having been immersed in the milieu of the trial. Where this is so it is commonly said that the appellate court will not depart from the trial judge’s conclusions unless they are shown to be wrong by reference to ‘incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony’ (Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 at 128 [28]) or otherwise be ‘contrary to compelling inferences’ (Fox v Percy at 128 [29]).

47 Between these two extremes lies a grey area in which the amount of deference shown to a trial judge’s conclusions is a function of the relative advantage enjoyed by the trial judge over the appellate court. That the appellate court can review in such cases is not in doubt. Speaking of the question of when an appellate court can review inferences drawn from facts already found, the High Court explained it this way in Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; 142 CLR 531 at 551:

‘[I]n general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge. In deciding what is the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge, but, once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it.’

48 It has been subsequently explained, if it were necessary, that the last sentence means that the appellate court should not eschew review once it has perceived error (see Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs v Hamsher [1992] FCA 233; 35 FCR 359 at 369 per Beaumont and Lee JJ; Branir at 432-433 [14]-[15]).

49 What kinds of case lie in this indeterminate area? Warren v Coombes provides part of the answer: the drawing of inferences from facts already found. But there are other examples, too: does certain packaging convey a representation; is a word capable of distinguishing one trader’s goods from another? There are also some legal standards which are so amorphous in nature that it will be difficult to say with any certainty whether a given fact lies within or without the standard. Examples will include concepts such as unconscionability and oppressive conduct. Whilst the question of whether a given set of facts could fall within such a standard is a question of law (Vetter v Lake Macquarie City Council [2001] HCA 12; 202 CLR 439 at 450 [24]) the question of whether a particular set of facts does do so is a question of fact. It is for that reason that such questions are sometimes referred to as, perhaps confusingly, mixed questions of fact and law. Each of these kinds of standard involves an element of evaluation (just as the drawing of an inference does). When an appellate court comes to review such conclusions it must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding (which would be decisive were a question of law involved) but by whether it detects error in the finding. On the one hand, error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion which has been reached has involved some false step; for example, where some relevant matter has been overlooked or some extraneous consideration taken into account which ought not to have been. But error, on the other hand, may also appear without any such explicitly erroneous reasoning. The result may be such as simply to bespeak error. Allsop J said in such cases an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a sufficiently clear difference of opinion: Branir at 437-438 [29].

50 There may seem an element of circularity in this, but the sufficiently clear difference of opinion bespeaks not merely that the appellate court has a different view to the trial judge but that the trial judge’s view is wrong even having regard to the advantages enjoyed by the trial judge and even given the subject matter: Branir at 435-436 [24].

51 Very often the degrees of certainty in this area are influenced by the openness of the question confronting the trial judge. For example, if the question for the trial judge was whether a particular colour was a rich blue, it might be rather hard to establish error in the trial judge’s finding so long as the object actually was blue. The very open nature of the enquiry creates a domain of discourse in which mere disagreement rather than error is much more likely to exist. On the other hand, a finding that a certain decision was unreasonable invokes a domain of legal discourse in which the appellate court stands in an equal, if not superior position, to that of a trial judge so that a conclusion of error may be more easily reached.

52 None of these observations is new and each was explained in Branir. There is a line of cases, however, beginning with the reasons of Weinberg J in Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 138; 87 FCR 415 (‘Eagle Homes’) which suggests that to review a finding involving an evaluative standard requires the appellate court first to find that the finding in question is ‘plainly and obviously wrong’ (at [119]). This was an obiter dictum but in my view it is not correct and should not be followed. It is contrary to Branir. Subsequently, in a joint judgment with Dowsett J, Weinberg J accepted the authority of Branir (see Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157; 234 FCR 549 at 567 [54]) which one might have thought brought an end to the issue. But this has not proved to be the case. Subsequent decisions have wrestled, with respect, unconvincingly with the status of the dictum in Eagle Homes. The Full Court in Metricon Homes Pty Ltd v Barrett Property Group Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 46; 248 ALR 364 at 368 [20] thought that Weinberg J had approached the issue in a way which was consistent with Branir and this appears to have been accepted by another Full Court in Vawdrey Australia Pty Ltd v Krueger Transport Equipment Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 156; 261 ALR 269 at 280 [43]. In Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 130; 197 FCR 67 at 79 [32] a different Full Court thought the difference between Branir and the dictum of Weinberg J was merely ‘semantic’.

53 With respect, the position was correctly stated by Nicholas J in EMI Songs Australia Pty Ltd v Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 47; 191 FCR 444 (‘EMI’) at 507 [259]-[260] where his Honour identified the need in this area to determine ‘how extensive the difference of opinion must be before an appellate court intervenes’ by reference to the extent of the perceived advantages of the trial judge in any given case. In my view, this Court should state clearly that the Eagle Homes line of authority is wrong. The position is as stated by Allsop J in Branir and, in obiter, by Nicholas J in EMI.

54 In its written submissions, the Respondent submitted the primary judge’s findings on whether, inter alia, the packaging was misleading could only be reviewed if they were demonstrated to be wrong by ‘incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony’ or were ‘glaringly improbable’ citing the High Court’s decision in Robinson Helicopter Company Inc v McDermott [2016] HCA 22; 331 ALR 550 (‘Robinson Helicopter’) at 558-559 [43]. However, whilst it is true that the High Court did say that, it is clear it was not intending to overrule Warren v Coombes or Fox v Percy at 128 [28]-[29] which are to the contrary and the latter of which the Court cited as authority for its statement in the footnotes to paragraph [43]. Furthermore, at [56], the High Court explicitly invoked Warren v Coombes in criticising the Court of Appeal for failing to ‘give the respect and weight to the judge’s analysis of the issue which it deserved’. Once that is understood, it is clear the quoted passage in Robinson Helicopter is concerned with findings of fact involving the credibility of witnesses. To the extent that Robinson Helicopter has been applied to questions of impression in intellectual property cases, it has, with respect, been misunderstood: cf Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 56; 345 ALR 205 (‘Accor’) at 235 [149] and 245 [200]; Primary Health Care Limited v Commonwealth of Australia [2017] FCAFC 174 (‘Primary Health Care’) at [37] and [245].

55 It is useful then to deal first with the Naturals claims.

III. The Naturals Claims

56 The Naturals claims concerned four of the Appellants’ products. These were:

Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1);

Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 2);

Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo; and

Moroccan Argan Oil Dry Shampoo.

57 These four products were sold under the Appellants’ house brand PROTANE which is a registered trade mark. This house brand had various sub-brands too. These included ‘Naturals’ and ‘Professional’. The Appellants decided that these four products would be marketed as ‘PROTANE NATURALS’. As a sub-brand, the word ‘NATURALS’ was in smaller font than ‘PROTANE’. Examples of the PROTANE NATURALS branding appear at [25] and [26] above.

58 The decision to proceed with the four products under the PROTANE NATURALS branding was made by one of the Appellants’ employees, Ms Heng. Ms Heng did not give evidence at the trial. Ms Heng’s instruction was effected by Ms Spinks who, however, did give evidence. There was little attention at trial given to what other products were in the PROTANE NATURALS range apart from those featuring argan oil. There was some limited evidence of a coconut water product which looked like this:

59 In any event, the PROTANE range had been available since 2007. The four products have been found in the Appellants’ stores since around 26 September 2012. For the lion’s share of that time they have been sold in ‘Special Buy’ promotions. These promotions involve the sale of stock for a limited time on the basis of limited stock and are available only until that stock runs out. When sold in this way the products are sold in a dedicated ‘Special Buy’ area located in the central section of the store in wire cages. Products sold in the ‘Special Buy’ section of the stores seem often to have been offered for sale in a somewhat jumbled fashion. This might not ordinarily matter but a significant part of the Appellants’ submissions in the Full Court were devoted to the proposition that in assessing whether the conduct alleged was misleading, account needed to be taken of the context in which the sales occurred. Two photographs from the evidence will illustrate the Appellants’ point. The first gives some flavour to the general nature of the Special Buy area. It is a photograph of some unrelated products in a jumbled pile in a wire cage:

60 The second is a photograph of one of the shampoo and conditioner products being sold from a wire cage in the ‘Special Buy’ area:

61 Sometimes the products were sold in the cages in their cartons (rather than in a jumble). The cartons also bore the PROTANE NATURALS branding. An example of this is as follows:

62 Most of the sales of the four products in question were from wire cages in this fashion. For a period of about seven months in 2015 (between 10 April 2015 and 8 December 2015) the shampoo and conditioner were also sold as part of the Appellants’ ‘core range’ and, as such, were sold from the shelves. The relevant shelves were located in the health and beauty section which is generally on the back wall of the Appellants’ stores. A photograph of the shampoo products being sold from the shelves in their carton is as follows:

63 The PROTANE NATURALS branding on the carton should be noted. The important points to grasp from the above contextual observations are:

(a) some of the four products were only ever been sold from the Special Buy area;

(b) the shampoo and conditioner were sold for seven months from the shelves; and

(c) in both cases, there were displays of the products in their cartons; but

(d) in the Special Buys areas the products were also sold loose and not from their cartons.

1. The Nature of the Naturals Claims

64 The Respondent’s case at trial was that by using the word NATURALS on the packaging the Appellants had represented to consumers that the four products were made either wholly or substantially from natural ingredients. The primary judge found that this representation was conveyed by the packaging. Her Honour also accepted the Respondent’s submission that this representation was misleading because her Honour thought that, apart from water, they contained only a very small percentage of natural ingredients.

65 Initially, Aldi challenged both of these conclusions. However, at the hearing of the appeal the second challenge was abandoned. This appeal consequently is concerned only with whether the NATURALS representation was conveyed by the packaging.

2. The Primary Judge’s Reasoning

66 The primary judge considered the way the word ‘Naturals’ was used on the packaging and concluded that it appeared on the main and rear display panels of the products, on in-store advertising signs and on the cartons in which the goods were displayed. Although her Honour did not make explicit reference in the part of her reasons dealing with the Naturals claims to the sale of the four products from the Special Buy wire cages, her Honour had explicitly referred to that matter at [27]-[28] in an introductory part of her reasons. Her Honour’s reference, when she came to deal with the Naturals claims, to ‘the cartons in which the goods are displayed’ may be capable of suggesting that her Honour had overlooked the sales of the products in the wire cages other than from cartons, but this is unlikely in light of [27]-[28].

67 Her Honour accepted that the word NATURALS was part of the composite brand PROTANE NATURALS. She noted, however, that the Appellants had admitted in their defence ‘that the word “naturals” on the products in question [was] intended to convey that the products contain one or more ingredients derived from a plant or animal source’. In this Court, Mr Dimitriadis SC, for the Appellants, was clear that the Appellants stood by that admission.

68 Turning then to whether the packaging conveyed the representation, her Honour first assayed the relevant class of consumer. This her Honour did in an earlier part of her reasons which dealt with a representation case which her Honour ultimately rejected but in respect of which the consumer class inquiry was the same. Her Honour concluded at [346] that the ordinary reasonable consumer of the products was someone who shopped, or may have shopped, at one of the Appellants’ supermarkets, was aware of the Respondent’s brand and its products and was attracted by the prospect of purchasing them at a bargain price. More often than not the consumer would be a woman. Some of this group would be unaware that the Respondent’s products were not available for sale at the Appellants’ supermarket. There would be frequent and regular Aldi shoppers but there would also be casual or infrequent shoppers.

69 The primary judge’s identification of the class of consumers largely by reference to the Respondent’s products reflects the fact that the main representation case (which her Honour rejected) concerned a contention that the packaging too closely resembled the Respondent’s products. If one strips out of her Honour’s determination of the relevant class of consumer the references to the Respondent’s products (because they are irrelevant to the Naturals claims) one is left with the ordinary reasonable consumer being a person attracted to buying at bargain prices, most likely a woman and shopping at the Appellants’ supermarkets frequently, infrequently or for the first time. On appeal, no party has challenged her Honour’s conclusions in this regard.

70 The primary judge then considered the meaning of the word ‘NATURALS’. Although her Honour posed this question initially as one inviting a consideration of meaning per se (‘the first contention raises a question as to the meaning of “natural”?’) it is clear that her Honour subsequently asked the orthodox question in this context which was ‘whether the representation is misleading or deceptive to the ordinary or reasonable member of the relevant class of consumer’.

71 Having posed that question her Honour then referred to some dictionary definitions of ‘natural’ including the 6th Edition of the Shorter Oxford Dictionary where it said, inter alia, that ‘natural’ meant ‘not manufactured or processed’ and the 5th Edition of the Macquarie Dictionary where it was said it meant, inter alia, ‘not artificial’.

72 Her Honour’s critical reasoning then followed at [462]-[463] which it is convenient to set out in full:

‘462 All of the products in question have been manufactured. In this sense none of them could be called “natural” products. But it was not MIL’s case that in the present context “natural” or “naturals” should be taken to refer to the final product. Its case was that “naturals” alludes to the ingredients used to make the product. If most of those ingredients were processed or manufactured, then the ordinary or reasonable member of the class of consumer would not consider them to be “natural”. In effect, Ms Spinks agreed. When asked whether consumers who saw the word “natural” would thereby take a message from the product that it contained natural ingredients or an ingredient she answered unequivocally “yes”. Aldi’s position, as articulated through Ms Spinks, was that as long as there was some amount, no matter how small, of at least one ingredient that could be described as natural, that was enough to justify the product’s inclusion in the PROTANE NATURALS range. She was never concerned with the percentage of argan oil in the products.

463 In my opinion, the ordinary or reasonable consumer shopping for hair care products, seeing the reference to “naturals” on the bottles or their containers, would consider that they were made, either wholly or substantially from natural ingredients. There is no logical reason why a trader would choose to call a product line “naturals” unless it intended to convey to the consumer that the product was “natural” or was comprised of substantially natural ingredients.’

3. The Appellants’ Contentions

73 The Appellants submitted that the primary judge failed to take into account the context in which the conduct had occurred and had instead adopted an artificial approach of focussing on the definition of the word ‘naturals’. Further, the Appellants submitted that her Honour had erred at [463] set out above: it was erroneous to say that there was no logical reason why a trader would choose to call a product line ‘naturals’ unless it intended to convey to the consumer that the product line was ‘natural’ or was comprised of substantially natural ingredients. It is useful to deal with these various points in turn

4. Context

74 Whether particular conduct results in a representation is a question of fact ‘to be decided by considering what [was] said and done against the background of all surrounding circumstances’. Further, where the question is whether a representation has been made to a large group of persons such as, as here, potential purchasers, the issue of whether the representation has been made ‘is to be approached at a level of abstraction not present where the case is one involving an express untrue representation allegedly made only to identified individuals’: as to both propositions see Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 (‘Campomar’) at 84-85 [100]-[101]. The primary judge expressly recognised the first of these principles at [338] and observed that those circumstances included ‘the circumstances in which the respective products are sold to the public’.

75 For my part, I do not think that the Appellants’ submission that her Honour then failed to consider that very context can be sustained. As the Respondent submitted, it is clear that her Honour had considered the context in which the conduct occurred by examining the use of the words PROTANE NATURALS on the products as they were displayed in store and this included a clear awareness on her Honour’s part of the advertising signs and cartons. It is true, as I have already noted, that her Honour did not expressly refer in her treatment of the Naturals claims to the distinction between the two products briefly sold on the shelves for seven months and the more common sale of all of the products from the wire cages of the Special Buys sections. However, her Honour was plainly cognisant of this distinction for she had expressly referred to it at [27].

76 In light of that it is not possible to accept the submission that the primary judge did not take the context into account. The Appellants nevertheless pointed to five aspects of the context which they submitted the primary judge had not taken into account.

77 The first was that the word ‘NATURALS’ had not been used prominently on the packaging. As an aspect of that argument the Appellants submitted that her Honour had failed to observe that the word NATURALS was in smaller font than the word PROTANE. Her Honour was certainly aware that the PROTANE NATURALS sign had been used prominently on the packaging because her Honour found at [391] that ‘all the Aldi products prominently display the PROTANE NATURALS sign… which is absent from all the MIL products’. In saying this her Honour was explaining the differences between the Respondent’s products and the Appellants’ products from the perspective of considering the Respondent’s case (rejected by her Honour and not the subject of appeal) that the Appellants’ packaging suggested an association with the Respondent. It would be to misuse this passage in her Honour’s reasons to construe it as involving any consideration of the relative roles of the words PROTANE and NATURALS to which that part of the case bore no relation. I do not think (and it was not suggested), therefore, that [391] may legitimately be used to demonstrate that her Honour had found that the words NATURALS had been prominently used on the packaging. Paragraph [391] is just not directed at that issue.

78 Further, the Appellants are correct when they submit that her Honour does not appear to have expressly referred to the smaller font of NATURALS when compared to that of PROTANE when her Honour did come to deal with the case based on the word NATURALS. Be that as it may, I do not think that her Honour was unaware of this or, more substantively, that this Court should proceed on the basis that her Honour must have overlooked the fact that the word NATURALS was in smaller font. Her Honour set out in her reasons for judgment extensive photographs of the products which show the font difference and sat through a trial of several weeks duration surrounded, no doubt, by an array of these products. I would not be prepared to conclude that her Honour had somehow not noticed what is entirely obvious, namely, the font size. As Gleeson CJ, McHugh and Gummow JJ observed in Whisprun Pty Ltd v Dixon [2003] HCA 48; 200 ALR 447 at 464-465 [62]:

‘The fact that his Honour did not refer to these matters in his judgment is not decisive. A judge’s reasons are not required to mention every fact or argument relied on by the losing party as relevant to an issue. Judgments of trial judges would soon become longer than they already are if a judge’s failure to mention such facts and arguments would be evidence that he or she had not properly considered the losing party’s case.’

79 The second contextual complaint was that because “NATURALS’ was a plural it was not being used in any precise sense. Mr Cobden SC, for the Respondent, submitted that the Appellants had not led any evidence to suggest that consumers would understand these two words differently. Of course, this was not necessary – it was the Respondent, after all, that was contending that the conduct gave rise to the representation. Indeed, the Appellants pointed out that the only consumer who gave evidence, Ms Royds, did not notice the word ‘NATURALS’ at all. However, Ms Royd’s evidence was discounted by the primary judge on the basis, inter alia, that her memory was generally poor and that, at the time that she saw the products, she was distracted by her children. The Respondent submitted that this finding was limited to Ms Royd’s apparent confusion which was relevant only to one aspect of the ACL case. However, although it is true that Ms Royd’s evidence about this occurred in her Honour’s treatment of part of the ACL case, I do not think that is a material distinction for present purposes. Nor do I accept the Respondent’s submission that her Honour’s criticisms of Ms Royd’s evidence were limited to her evidence about confusion. Her Honour set out a number of other criticisms at [199]-[205] and these included the fact that Ms Royds had a background in advertising and also that her evidence of having bought the Appellants’ hair treatment oil from the shelves could not be correct since it had only ever been sold from the wire cage.

80 In any event, it remains the case that there was no evidence that consumers approached NATURALS any differently to NATURAL (or, conversely, that they treated them the same). The Respondent did not submit that the primary judge had in fact considered the significance of the plural word ‘NATURALS’ as opposed to the singular ‘NATURAL’ and it seems that her Honour did not. It is likely that her Honour took that approach because she was influenced by the Appellants’ admission that the word NATURALS was intended to convey that the products featured one or more ingredients derived from animals or plants. The Appellants had submitted at trial that ‘NATURALS’ would only be perceived as part of the composite expression ‘PROTANE NATURALS’ and hence not as a word in its own right. Her Honour rejected this argument because it was inconsistent with the Appellants’ admission. No appeal is brought from that conclusion.

81 To return to the Appellants’ original submission, I do not think that her Honour failed to consider the distinction between NATURALS and NATURAL. In light of the Appellants’ admission her Honour did not think the difference material. In any event, although minds might reasonably differ on the issue there was nothing one way or the other to suggest that NATURALS had a less precise impact than NATURAL.

82 The third contextual matter was that the products were sold at cheap prices in the context of a discount supermarket in respect of which consumers were unlikely to give close consideration to the word ‘NATURALS’. However, the primary judge was aware of the prices at which the products were sold (see [402] where they were set out) and the fact that the Appellants were a discount supermarket. The very first sentence of paragraph [1] in her Honour’s 747 paragraph judgment is ‘Like brands, only cheaper…’. It is unthinkable that this was not part of the context which her Honour considered when it formed the capstone of the reasons for judgment.

83 The fourth contextual matter was that if a consumer had noticed the word NATURALS then they would not have given it the dictionary definition that the primary judge had (i.e. manufactured or artificial). Thus it was said that an ordinary reasonable consumer would not expect to get a $4.99 bottle of shampoo in the Special Buys section of the Appellants’ supermarkets which was constituted substantially by natural products. The Respondent’s answer to this was that (a) the primary judge had had regard to the context in which the products were sold, and (b) that context included the bargain price. To this one might add that the primary judge was also plainly aware of the Special Buys area. For myself I can see considerable force in the Appellants’ contention about this but I do not think it has established that the matter was not considered by the primary judge.

84 The fifth contextual matter was that if a consumer had given any weight to the word NATURALS they would also have had regard to the ingredients list on the back of the container which would have dispelled any confusion. The Respondent’s answer to this was that the word NATURALS was prominently displayed on the products as found by the primary judge but there was no corresponding finding that the ingredients list was prominent too. This is true but only because, as the Appellants submitted, the primary judge did not deal with the significance of the ingredients list. It is no answer to that observation to argue, as the Respondent did, that her Honour had asked herself the correct question. I accept that the primary judge did not consider the effect of the ingredients list. I do not accept that that means her Honour did not consider the context.

5. Over-focus on definitions

85 Her Honour identified at [458] that the correct question to be asked was what was conveyed to the ordinary reasonable consumer by the word NATURALS. Her Honour then immediately began to answer this question by consulting various dictionary definitions of the word ‘natural’ which I have set out above. It was after setting out those definitions that her Honour then reached her critical conclusion at [462] and [463] which I have set out above. The process of reasoning disclosed at [462] is complex. It involves these steps. First, ‘natural’ means not artificial. Secondly, an ordinary reasonable consumer would not think that a product made mostly from processed or manufactured ingredients was natural. Pausing here, neither of these propositions is on its face erroneous although the second is, with respect, at least legally irrelevant. The question is not whether such consumers thought that manufactured ingredients could be described as ‘natural’; rather, it was what was conveyed to those consumers by the word NATURALS on this packaging. Thirdly, the Appellants’ admitted position (and Ms Spinks’ evidence) that the word ‘NATURALS’ was intended to convey that the product contained one or more natural ingredients supported this conclusion. This, too, seems to me to be contestable. Her Honour’s second proposition was whether consumers would consider a product made mostly from manufactured ingredients to be ‘natural’; it was not about what meaning was conveyed by the word ‘NATURALS’ on the packaging. Further, the Appellants’ admitted position and (Ms Spinks’ evidence) said nothing about products being mostly made from a particular kind of ingredient. There is a contradiction between (a) the idea that consumers would not regard as ‘natural’ a product made mostly from manufactured products together with her Honour’s view that ‘in effect, Ms Spinks agreed’; and (b) the last sentence in [462] that Ms Spinks ‘was never concerned with the percentage of argan oil in the products’. This, however, was not an error of which Aldi complained.

86 Fourthly, at [463] her Honour concluded that the word ‘NATURALS’ conveyed that the products were made wholly or substantially from natural ingredients. If this is said to follow from [462] it involves a non sequitur. Her Honour’s treatment of what the ordinary reasonable consumer would understand in that paragraph is pitched not at what that word on the packaging conveys but instead on the different and, I fear, irrelevant question of what those consumers would consider the word to mean. Further, it also cannot follow from Ms Spinks’ evidence which clearly was not directed at the idea that the product was made substantially from any particular kind of ingredient.

87 Fifthly, at [463] her Honour reasoned that her conclusion was supported by the fact that there was no logical reason for a trader to call a product line ‘NATURALS’ unless it was intended to convey that the product was composed substantially of natural ingredients.

88 The Appellants’ submission that the primary judge was too focussed on dictionary definitions should be accepted. I would not go so far as to say that resort to dictionaries in cases such as the present is a forbidden consideration. No doubt what the ordinary reasonable consumer understood the word ‘NATURALS’ on the packaging to mean would be influenced, or might be influenced, by the meaning of the word in ordinary English. But the risk raised by the use of such definitions – a risk that has materialised in this case – is that it may cause the wrong question to be asked. Armed with the dictionary definition her Honour was understandably seduced into asking whether the ingredients in the products could be described as ‘natural’ when the correct question was what did the use of the word ‘NATURALS’ convey to ordinary reasonable consumers. This involved error.

6. No legitimate reason to use word NATURALS

89 The Appellants submitted that the last sentence of [463] lacked a proper basis. There were, they submitted, perfectly good reasons why a trader might decide to call a product line ‘NATURALS’ without implying that the products in that line were substantially made from natural ingredients. I agree. A trader might well have legitimate reasons for calling a product line NATURALS which have little to do with the quantity of natural product in the product. For example, it may merely connote that the product has a nominated natural product added to it. It may mean in this case that the shampoo and conditioner has had added to it a single natural product – i.e. argan oil. This is not to say that this inevitably be so, only that her Honour’s statement that it could never be so goes too far.

90 I accept, therefore, that this too involved error.

7. Result

91 Error having been established it falls then to this Court to give its own view on the matter. In my opinion, the use of the word NATURALS did not convey to the ordinary reasonable consumer that the products comprised substantially natural products. My reasons for this are:

the word NATURALS was in smaller font than the word PROTANE and off to the right on the next line. Furthermore, it was a plural not a singular word. If the ordinary reasonable consumer noticed the word ‘NATURALS’ at all they would have understood it to be a sub-line of the PROTANE products and not a statement about the quantity of natural ingredients in the products.

with the exception of the shampoo and conditioner product which was sold for seven months on the shelves, these products were sold from the discount bins in the middle of the store, sometimes in a jumble. The prices were $4.99 for the shampoo and conditioner and from between $7.99 to $9.99 for the oil treatment. The ordinary reasonable consumer would approach the packaging on the basis that they were in the cheapest part of one of the cheapest stores. This is not where one expects to find hair care products made substantially from boutique natural ingredients such as argan oil. This is an Aldi supermarket.

the ordinary reasonable consumer would have understood, however, that argan oil was a natural product and to the extent that such consumers pondered what was natural about these products, it would have been that they contained some argan oil.

92 In light to that conclusion the appeal must be allowed on this ground.

IV. The Performance Benefits Claims

93 This part of the case was concerned with three Aldi products: the Moroccan Argan Oil Treatment (Version 1), the Moroccan Argan Oil Shampoo and the Moroccan Argan Oil Conditioner. The front label of each of these products bore in prominent text the words ‘Moroccan Argan Oil’ or, from January 2016, ‘Argan Oil of Morocco’. I have set out above at [29]-[35] the text of the actual product claims and they do not need to be set out again.

94 The Respondent submitted to the primary judge, and her Honour accepted, that ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer ‘would infer from the product name that it is argan oil which is wholly or largely responsible for the touted benefits’. The Appellants have contested the correctness of that conclusion.

95 It is useful to begin with the primary judge’s reasons. Her Honour noted the Appellants’ submission that the Performance Benefits claims related to the product as a whole rather than to any of its constituent ingredients. However, her Honour preferred the Respondent’s submission that the representation was conveyed by the Appellants’ use of ‘Moroccan Argan Oil’ on the packaging of the products. Her Honour’s actual reasoning was at [494]:

‘494 I accept MIL’s contention. I have little doubt that ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer would infer from the product name that it is the argan oil which is wholly or largely responsible for the touted benefits. Indeed, I think it likely that Aldi intended to create that impression.’

96 Her Honour then expanded upon the last sentence of that quote. Within the Appellants there is an internal process for ensuring that claims that are made for their products are validated or substantiated. This process involves the completion of a document for each product which has fields for the relevant product claim and the substantiation of that claim. Such a document had been prepared for the Aldi oil treatment. It included entries for the claims that the product ‘helps strengthen hair’ and ‘restores shine and provides long term conditioning’. The former claim was said to be substantiated by the statement ‘Argan oil is known to have hair strengthening properties’ and the latter by ‘Argan oil provides shine and has conditioning properties’. Her Honour inferred from this material that the Appellants intended to convey to consumers that it was the argan oil which was responsible for the performance benefits. As her Honour said ‘[t]hat intention was realised’ which I take to be an example of orthodox reasoning that when a party intends an effect by their actions the Court may more readily infer that the effect has been produced by those actions: Campomar at 63 [33].

97 Before moving to the submissions which are made, I reject the Appellants’ initial suggestion in reply that the question of whether the representations are misleading is live in this appeal. It appears most likely that the submission has been made under an erroneous reading of the Respondent’s submissions. In any event, it is quite clear that this issue is not live in the present appeal.

98 The Appellants’ first submission was that the primary judge had erred in focussing on only one feature of the product packaging, namely, the words ‘Moroccan Argan Oil’. Her Honour had, on this view, failed to construe the packaging as a whole and in the context of the circumstances of its sale in a discount supermarket. In his address, Mr Dimitriadis expanded on this: there was no evidence that anyone had actually been confused by the packaging; the font in which the claimed performance benefits appeared was small; and, the products were being sold in the Special Buys section.

99 For its part, the Respondent denied these matters. It was wrong to think that her Honour had not considered the significance of the packaging for she had examined the position of the ordinary reasonable consumer at [344]-[346]. I do not think however, that her Honour dealt with packaging issues in that section. In any event, the Respondent pointed out that the Appellants had not led any evidence to suggest that the representation was not made because the stores involved a discount environment.

100 Further, so the Respondent submitted, why would those words have been placed on the products unless they were intended to be seen? Reference was made to the well-known passage in the reasons of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills Limited v F.S. Walton and Company Limited [1937] HCA 51; 58 CLR 641 at 657:

‘The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive. Moreover, he can blame no one but himself, even if the conclusion be mistaken that his trade mark or the get-up of his goods will confuse and mislead the public.’

101 As for the Appellants’ contention that there was no evidence that any consumer had been confused, the Respondent submitted that such evidence was not necessary, referring to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2014] FCA 634 at [45] per Allsop CJ.

102 The submissions of the Respondent on this first point are to be preferred. I do not accept that the primary judge did not consider the packaging of the products, or how they were sold in the stores or the prominence of the Performance Benefits claims. Throughout her judgment her Honour was obviously aware of these matters. Nor, in this context, does it matter much that no consumer was produced to prove that the discount nature of the Appellants’ supermarket meant that no representation was conveyed.

103 The Appellants’ second point was that the stated benefits were not explicitly linked to the presence of the argan oil and should have been taken to refer to the product as a whole. To this the Respondent replied that the primary judge had considered this contention at [492] and rejected it. This is true and it is not possible to say this issue was overlooked. Furthermore, there is force in the Respondent’s submission that in reaching that conclusion her Honour was entitled to take into account the proximity of the Performance Benefits claims to the words ‘Argan Oil’. It is not clear that her Honour explicitly did so but her Honour was certainly aware of the font size as [493] of her Honour’s reasons shows and her Honour must have been aware of the location of the claims about the performance benefits. I accept the Respondent’s submission, therefore, that her Honour did take into account the font size of ‘Argan Oil’ and its proximity to the Performance Benefits claims in coming to the conclusion she did.

104 Of more substance was the Appellants’ contention that one of the Performance Benefits claims was that two of the products was said to be sulfate free and one of them alcohol free. Viewed objectively, those statements could not reasonably be understood as qualities of argan oil hence it cannot be the case that the Performance Benefit claims relate to the presence of argan oil. I accept the logic of this argument if the matter is viewed in the cold light of day. However, that is not how these products were viewed. They were instead viewed under fluorescent light in the bargain bin at the Appellants’ supermarkets by consumers probably not overly enthusiastic to tease out what could logically be linked to the words ‘Argan Oil’ and what could not. I accept, therefore, the Respondent’s submission that ordinary reasonable consumers would not read the labels with that degree of care.

105 It might be possible that if the NATURALS claim had succeeded that this might have added weight to this case. On this view, if the product line were considered NATURALS because the products were made substantially from natural products then there might be reason to think that consumers concerned with such matters might tend to link the performance benefit to the presence of the natural products. Indeed, the Respondent made that precise submission. However, given that the NATURALS case has not succeeded on appeal an argument in this form fails too.

106 There was no evidence that any consumer was, in fact, misled but this does not necessarily entail very much. There is a degree of controversy attending the extent to which such evidence should be received (see, e.g., the remarks of Murphy J in Telstra Corp Ltd v Phone Directories Co Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 568; 316 ALR 590 at 701 [564]-[566]. But the absence of such evidence does not logically entail that consumers were not misled; only that no such evidence was led. There may be many explanations for the failure to lead such evidence beyond the notion that no such consumers can be found. I do not agree, therefore, with the submission that the absence of this evidence was ‘telling’.

107 I do not doubt that on the evidence which was before the primary judge, a different view could have been taken. Indeed, for myself I would tend to the view that the packaging was not suggesting to the ordinary reasonable consumer that the performance benefits were linked to the presence of argan oil. However, her Honour was immersed in this material at the trial and whilst it is a matter of impression I tend to think that her Honour’s opinion is more likely to be better informed than mine. I do not think that the fact that my view on this issue differs from that of the primary judge leads to the inference that her Honour erred.

108 The Appellants’ third point was that there was no suggestion that the claimed benefits were not obtained from the products. However, since this was not the Respondent’s case this is unsurprising.

109 The Appellants’ fourth point was that the products were inexpensive. It is not altogether clear how that proposition advances the task of associating the Performance Benefits claims with the presence of argan oil. But, in any event, it is clear that the primary judge was aware of the inexpensive nature of the product range.

110 The Appellants’ final point related to the primary judge’s use of their internal quality-claims substantiation documentation. There were two points: first, the quantity of documents was too limited to support the inference for which the primary judge had used them; secondly, even if that were not so, intention was irrelevant in a case of misleading or deceptive conduct.

111 Neither of these arguments is persuasive. I have referred above to the document in question. It was, at least, some evidence that in their own deliberations the Appellants linked some of the Performance Benefits claims to argan oil. There could have been more evidence, no doubt, but it was open to her Honour to infer from the material that the Appellants thought the argan oil to have those effects. And this must be all the more so in light of her Honour’s consideration of the packaging. As to the suggestion that intent is irrelevant, the true position is that it need not be demonstrated. But where it is demonstrated, it is orthodox to reason that a representation is more likely to be established as having a particular effect where that was the intention of the party making it.