FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 78

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Appellant | ||

AND: | PFIZER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 008 422 348) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The question of the costs of the appeal be reserved.

3. Within fourteen (14) days after the date hereof, each party file and serve a Written Submission of no more than six (6) pages in length in which each party sets out the order or orders for costs which that party seeks and its submissions in support of that order or those orders.

4. Thereafter the question of the costs of the appeal be decided on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

THE ACCC’S CASE, PFIZER’S DEFENCE AND THE ISSUES AT TRIAL | [22] |

Some Matters of Context (Paragraph 1 to Paragraph 41 of the ASC) | [24] |

The Impugned Conduct (Paragraph 42 to Paragraph 60 of the ASC) | [62] |

The Alleged Section 46 Contraventions (Paragraph 61 to Paragraph 67 of the ASC) | [74] |

The Alleged Section 47 Contraventions (Paragraph 68 to Paragraph 73C of the ASC) | [79] |

The Section 51(3) Defence (Paragraph 73D of the Defence) | [84] |

THE JUDGMENT OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE—A SYNOPSIS | [85] |

Section 46 and Section 47 of the CCA (The Law) | [88] |

The Sale of Pharmaceutical Products in Australia | [123] |

The Application of the Law to the Facts (Section 46 and Section 47) | [136] |

The Market | [138] |

Pfizer’s Power in the Atorvastatin Market | [148] |

Taking Advantage | [151] |

Purpose | [152] |

Paragraph 67 and Paragraph 67A of the ASC | [158] |

Section 47 | [161] |

Section 51(3) of the CCA | [164] |

PFIZER’S CONDUCT | [166] |

THE RELEVANT STATUTORY PROVISIONS | [169] |

THE ISSUES ON APPEAL | [176] |

The Pleading Point (Appeal Ground 17) | [178] |

The Primary Judge’s Reasons | [179] |

The ACCC’s Submissions | [186] |

Pfizer’s Submissions | [191] |

Consideration | [200] |

Market Definition (Contention Ground 1) | [222] |

The Primary Judge’s Reasons | [225] |

Pfizer’s Submissions | [233] |

The ACCC’s Submissions | [246] |

Consideration | [263] |

The Relevant Principles | [263] |

Decision | [282] |

Pfizer’s Market Power in the Atorvastatin Market (Section 46(1)(c) of the CCA) (Appeal Grounds 1, 2 and 3) | [310] |

The Primary Judge’s Reasons | [313] |

The ACCC’s Submissions | [319] |

Pfizer’s Submissions | [326] |

Consideration | [331] |

The Relevant Legal Principles | [331] |

Decision | [340] |

Taking Advantage of the Relevant Market Power and Proscribed Purpose (Section 46(1)(c) and Section 47(10)(a) of the CCA) (Appeal Grounds 4, 5, 7 and 8; 10 to 16 and 23 to 26) (Contention Grounds 2 and 3) | [360] |

Introduction | [360] |

The Primary Judge’s Reasons | [382] |

The Relevant Legal Principles | [457] |

Taking Advantage – Section 46(1)(c) and Section 46(6A) of the CCA | [457] |

Purpose – Sections 4F, 4G, 46(1)(c) and 47(10)(a) | [466] |

The Full Court’s Role on Appeal | [485] |

Consideration | [493] |

The ACCC’s Approach to the Trial Judge’s Findings of Fact | [493] |

Pfizer’s Conduct | [499] |

Taking Advantage | [510] |

Pfizer’s Purpose | [525] |

The ACCC’s Section 47 Case | [566] |

Section 51(3) Exemption | [579] |

Introduction | [579] |

Primary Judgment | [587] |

Consideration | [590] |

Did Pfizer’s Offers Involve the Grant of a Licence? | [590] |

Did the Offers include Conditions of the Licence? | [595] |

Did the Condition “relate to” the Invention or Articles made by Use? | [597] |

CONCLUSIONS | [607] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 Statins are a class of pharmaceutical which is widely prescribed in Australia. They reduce the production of cholesterol in humans thereby lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease including stroke.

2 Atorvastatin is one such statin. It was first made in August 1985 by Warner-Lambert LLC (Warner-Lambert) at its Parke-Davis facility in Michigan in the United States of America. In 1985, Parke-Davis and Company (Parke-Davis) was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Warner-Lambert.

3 For 25 years, Warner-Lambert was the registered owner within the meaning of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act) of Australian Patent No 601981 (atorvastatin patent). That patent was in effect from 18 May 1987 to 18 May 2012.

4 In 2000, Pfizer Incorporated (Pfizer Inc) acquired Warner-Lambert and all of its subsidiary companies, including Parke-Davis.

5 Pfizer Inc is a public company incorporated in accordance with the laws of the State of Delaware in the USA and headquartered in New York. It is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

6 Pfizer Inc and its subsidiaries and affiliates research, develop, manufacture, market and supply prescription medicines, over-the-counter health care products and animal health products throughout the world.

7 Warner-Lambert and Pfizer Inc exploited the atorvastatin patent by manufacturing, marketing and supplying atorvastatin under the trade or brand name “Lipitor”. Pfizer Inc continues to manufacture and supply Lipitor notwithstanding that the atorvastatin patent expired on 18 May 2012.

8 The respondent in this proceeding, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (Pfizer), is ultimately owned by Pfizer Inc. For many years, it has been the entity within the Pfizer group of companies which markets and supplies Lipitor in Australia.

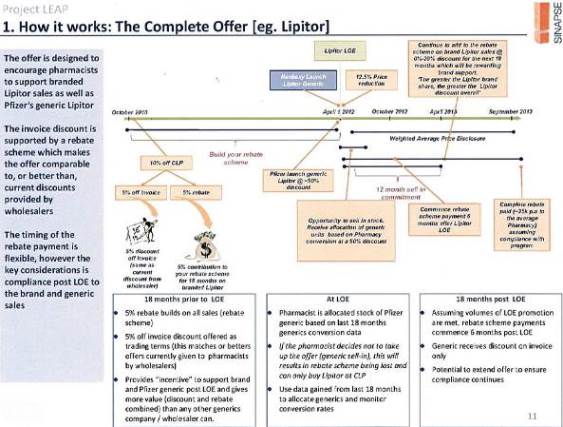

9 From about mid-January 2012, Pfizer began to offer to supply, and subsequently to supply, its own generic atorvastatin under the trade name “atorvastatin Pfizer”. Since January 2012, both Lipitor and atorvastatin Pfizer have been supplied in Australia by Pfizer.

10 During the period from about the mid-1990s to 2012, Lipitor became the biggest-selling drug in the world. For each of the financial years ended 30 June 2010, 30 June 2011 and 30 June 2012, the value of atorvastatin sales in Australia under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) exceeded $700 million. For the period from at least about 2000 to 18 May 2012, Pfizer had the exclusive right to supply atorvastatin in Australia. Atorvastatin was, and is, a very significant contributor to the earnings of the Pfizer group of companies, especially in Australia.

11 In the years prior to 2012, the date upon which the atorvastatin patent would expire was well known to Pfizer’s competitors, especially the large manufacturers of generic prescription drugs. Pfizer expected that it would experience significant and ongoing competition in the market for the supply of atorvastatin in Australia immediately after the expiration of the atorvastatin patent.

12 In order to meet that competition and to avoid being “slaughtered” (to use a word coined by certain Pfizer executives in 2011 in this context) in the market for the supply of atorvastatin in Australia, Pfizer took a number of steps. For present purposes, those steps are adequately described as follows:

(a) The establishment in January 2011 of a supply model which involved Pfizer supplying community pharmacies directly in lieu of doing so through wholesalers (DTP model);

(b) The establishment in January 2011 of an accrual funds scheme whereby funds would accrue in the books and records of Pfizer to each community pharmacy to which Pfizer supplied prescription pharmaceuticals (accrual funds scheme). This scheme involved Pfizer setting aside a percentage of the price of purchases of Pfizer pharmaceutical products paid by community pharmacies (including in respect of Lipitor) in an account created with Pfizer for each community pharmacy to be rebated to that pharmacy upon terms which were to be announced at a later date; and

(c) The making of a bundled offer in January 2012 to all, or virtually all, community pharmacies as to the terms upon which Pfizer would supply Lipitor and atorvastatin Pfizer which, amongst other things, tied the rebates that were available from the accrual funds scheme account to the quantity of Lipitor and atorvastatin Pfizer which each individual pharmacy purchased.

13 From at least late 2010, Pfizer recognised that, from early 2012, it would have to accommodate within its marketing strategies the inevitable switching of a patient’s use of atorvastatin from Lipitor to generic atorvastatin (including atorvastatin Pfizer) and from one generic version of atorvastatin to another. It did so as part of the bundled offers which it made in January and February 2012.

14 The steps which Pfizer took to which we have referred at [12] above came under scrutiny from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). In 2014, the ACCC commenced a proceeding against Pfizer in which it alleged that Pfizer had contravened s 46(1)(c) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) by taking advantage of the substantial degree of market power which the ACCC alleged that Pfizer held in the market for the supply of atorvastatin to, and the acquisition of atorvastatin by, community pharmacies in Australia (atorvastatin market) for a purpose which was proscribed by s 46(1)(c) of the CCA, namely, for the purpose of deterring or preventing generic manufacturers from engaging in competitive conduct in the atorvastatin market in Australia after the expiry of the atorvastatin patent. In addition, the ACCC claimed that Pfizer had engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing within the meaning of s 47 of the CCA by requiring community pharmacies who wished to acquire atorvastatin Pfizer from it also to purchase specified quantities of Lipitor and thus contravened ss 47(1), 47(2)(d) and 47(2)(e) of the CCA.

15 The learned primary judge dismissed the whole of the proceeding below (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 113; (2015) 323 ALR 429). His Honour accepted the ACCC’s definition of the relevant market and also accepted that, during the period from December 2010 to about December 2011, Pfizer had a substantial degree of market power in that market and took advantage of that market power by implementing its DTP model and by establishing the accrual funds scheme. His Honour took the view that, by January 2012, Pfizer no longer had a substantial degree of market power in that market. His Honour rejected the proposition that, by offering atorvastatin Pfizer upon the terms that it did in early 2012, Pfizer also took advantage of its allegedly substantial degree of market power in the atorvastatin market. Furthermore, his Honour concluded that Pfizer did not, at any time, exercise its market power in the atorvastatin market for a purpose proscribed by s 46 or, for that matter, for a purpose proscribed by s 47.

16 The primary judge also upheld a submission made to him by Pfizer to the effect that the contraventions pleaded by the ACCC in par 67 and par 67A of the Amended Statement of Claim filed on 8 September 2014 (ASC) could not constitute a contravention of s 46, even if the facts pleaded in those paragraphs were ultimately made out. Pfizer had submitted that the manner in which those contraventions had been pleaded by the ACCC was “legally incoherent”.

17 By Notice of Appeal filed on 18 March 2015, the ACCC appealed from the whole of his Honour’s judgment. In its Notice of Appeal, the ACCC raised 26 grounds of appeal. By that Notice of Appeal, the ACCC contended that:

(a) The primary judge erred in finding that, from January 2012, the market power which Pfizer enjoyed in the atorvastatin market was no longer substantial and should have held that Pfizer’s market power in that market in the period from January to May 2012 or, alternatively, in January and February 2012, remained substantial (Grounds 1 to 3).

(b) The primary judge erred in failing to find that, in making the bundled offers which it made to community pharmacies in early 2012, Pfizer took advantage of the substantial market power which it then enjoyed in the atorvastatin market and should have found that, by making those offers and by subsequently supplying atorvastatin in accordance with those offers, Pfizer took advantage of that market power (Grounds 4, 5, 7 and 8). Ground 6 was not pressed.

(c) In determining whether the ACCC had established that Pfizer had a purpose proscribed by s 46(1)(c) when it propounded its DTP model, the primary judge erred by applying the test set out in s 46(1)(b) of the CCA rather than the test set out in s 46(1)(c) of the CCA (Ground 9). This ground of appeal was abandoned at the hearing of the Appeal (see Transcript p 90 at ll 39–40).

(d) The primary judge erred in finding that it was not the intention, purpose or objective of Pfizer in taking the various steps which it took in late 2011 and early 2012, to shut out its competitors or to deter or prevent generic manufacturers from supplying their own generic atorvastatin to community pharmacies and in preferring witnesses called by Pfizer when considering whether Pfizer had the requisite proscribed purpose. According to the ACCC, his Honour should have held that a substantial purpose of Pfizer in taking those steps was to deter or prevent other suppliers of generic atorvastatin from engaging in competitive conduct in the atorvastatin market from 18 May 2012 (Grounds 10 to 16).

(e) The primary judge erred in holding that the ACCC’s pleading of the contravention of s 46 of the CCA by Pfizer at par 67 and par 67A of the ASC was legally incoherent (Ground 17).

(f) The primary judge erred in failing to consider or find that the terms and conditions of the bundled offers made to community pharmacies in early 2012 by Pfizer constituted a condition within s 47(2)(d) of the CCA or within s 47(2)(e) of that Act and should have held that the terms and conditions of those offers did constitute such conditions (Grounds 18 to 22).

(g) In determining whether Pfizer had a proscribed purpose within the meaning of s 47 of the CCA, the primary judge failed to distinguish between evidence as to Pfizer’s motive for taking the steps which it took in late 2011 and early 2012, on the one hand, and evidence directed to identifying Pfizer’s purpose, on the other hand, and, on balance, should have found that a substantial purpose of Pfizer in engaging in that conduct was to substantially lessen competition in the atorvastatin market by preventing or hindering other suppliers of generic atorvastatin from supplying that pharmaceutical to community pharmacies (Grounds 23 to 26).

18 In effect, on appeal, the ACCC contended that his Honour erred in each of the conclusions which he reached contrary to the arguments and contentions advanced by the ACCC at the trial. The ACCC’s attack on his Honour’s judgment involves an assault on many significant findings of fact made by his Honour and requires this Court to review in some detail much of the evidence tendered before his Honour.

19 Pfizer too was not entirely content with the judgment of the primary judge notwithstanding that it had secured a complete victory. By Notice of Contention filed on 8 April 2015, Pfizer sought to defend his Honour’s ultimate conclusions upon four bases which had not found favour with his Honour. These are:

(a) His Honour erred in finding that the relevant market was a market for the supply of atorvastatin to community pharmacies and should have held that the relevant market was a much broader market being the market for the wholesale distribution of generic pharmaceuticals as pleaded by Pfizer (Ground 1).

(b) His Honour erred in finding that Pfizer took advantage of its market power in implementing its DTP model in January 2011 (Ground 2) and in establishing the accrual funds scheme in January 2011 (Ground 3) since neither of these propositions was an issue raised by the ACCC in its case and since both steps could have been taken by a participant in the relevant market who did not enjoy a substantial degree of market power in that market.

(c) If the impugned conduct would otherwise have constituted a contravention of s 47 of the CCA, that conduct constituted the imposition of, or the giving effect to, a condition of a sub-licence granted by Pfizer (as licensee of the atorvastatin patent) to community pharmacies, which condition related to articles made by use of the invention to which the atorvastatin patent related and, by virtue of s 51(3) of the CCA, the impugned conduct did not constitute a contravention of s 47 (the s 51(3) ground) (Ground 4).

20 On appeal, both parties contended that the trial had been conducted strictly in accordance with the pleadings. Pfizer, in particular, repeatedly reminded the Court of this fact. In light of these contentions and, in particular, in light of the challenge made by the ACCC to his Honour’s acceptance of Pfizer’s submission that the ACCC’s pleaded case based upon s 46 of the CCA was “legally incoherent”, it is necessary for this Court to pay close attention to the pleadings when determining the Appeal and the matters raised by Pfizer in its Notice of Contention.

21 For these reasons, and before explaining the judgment of the learned primary judge, we now turn to consider the pleadings as they stood at the time of the trial and the issues raised thereby which were required to be determined by the primary judge.

The ACCC’s Case, Pfizer’s Defence and the Issues at Trial

22 In its Amended Originating Application filed on 8 September 2014, the ACCC claimed declarations in respect of the four contraventions of the CCA alleged in the ASC and orders pursuant to s 76(1) of the CCA requiring Pfizer to pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of each of the pleaded contraventions. The ACCC alleged that Pfizer was guilty of two separate contraventions of s 46(1) of the CCA and was also guilty of two separate contraventions of s 47(1) of the CCA. It also claimed costs.

23 Many of the allegations made by the ACCC in the ASC were admitted by Pfizer in its Defence to the ASC (filed on 17 September 2014) (Defence). Other allegations were substantially admitted by Pfizer in its Defence.

Some Matters of Context (Paragraph 1 to Paragraph 41 of the ASC)

24 At pars 1 to 41 of the ASC, the ACCC pleaded a number of facts, matters and circumstances which constituted the setting in which the alleged contraventions took place. Pfizer did not take issue with most of these matters. We shall endeavour to summarise these matters in this section of our Reasons. The reader should assume that these matters were admitted by Pfizer in its Defence unless otherwise stated.

25 At all relevant times, Pfizer was a wholly owned subsidiary of Pfizer Australia Holdings Pty Limited (Pfizer Holdings). Pfizer was ultimately owned by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer was also a body corporate which was related to Pfizer Inc and to Warner-Lambert, a company also incorporated in accordance with the laws of the State of Delaware, USA, within the meaning of s 4A of the CCA. Pfizer was engaged in the business of, amongst other things, the supply of pharmaceutical products in Australia.

26 Atorvastatin is a pharmaceutical which functions by blocking an enzyme in the liver which the human body uses to make cholesterol thereby lowering levels of cholesterol for its users. The claimed benefits to users of atorvastatin include lowering the risk of heart attack, stroke, heart disease and chest pain, particularly for users exhibiting high risk factors including a family history of heart disease, high blood pressure, old age, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or smoking.

27 Warner-Lambert was the registered patentee of the atorvastatin patent. The atorvastatin patent was valid, subsisting and in full force and effect, from 18 May 1987 to the date of its expiry on 18 May 2012.

28 Warner-Lambert has been ultimately owned by Pfizer Inc since about June 2000.

29 From around early 1998 until about June 2000, Warner-Lambert, utilising the invention comprising the atorvastatin patent, manufactured a prescription pharmaceutical known as atorvastatin calcium under the pharmaceutical name LIPITOR atorvastatin. From about early 1998 until about June 2001, Parke Davis Pty Limited (a wholly owned subsidiary of Warner-Lambert) supplied Lipitor to wholesalers of pharmaceutical products in Australia who then supplied it to community pharmacies operating in Australia, being pharmacies in relation to which approval to dispense prescription drugs had been granted under s 90 of the National Health Act 1953 (Cth) (Health Act).

30 In the ASC, the ACCC referred to any atorvastatin pharmaceutical supplied under a name other than Lipitor as Generic Atorvastatin.

31 Between about June 2001 until about 31 January 2011, Pfizer supplied Lipitor to wholesalers in Australia and to community pharmacies directly. The wholesalers with which it dealt in that period were principally Symbion Pty Ltd (Symbion), Sigma Pharmaceuticals Limited (Sigma) and API Limited (API). In the same period, wholesalers also supplied Lipitor to community pharmacies in Australia.

32 From about 31 January 2011, Pfizer has been the exclusive supplier of Lipitor to community pharmacies in Australia.

33 In each of the financial years ended 30 June 2010, 30 June 2011, 30 June 2012 and 30 June 2013, atorvastatin was the highest selling prescription pharmaceutical in Australia. In that period, atorvastatin was prescribed to over 1 million members of the public in Australia. In the same period, over 10 million units of atorvastatin were supplied to members of the public in Australia.

34 Atorvastatin was the pharmaceutical that accounted for the highest total amount of subsidies paid under the PBS throughout the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2013. In each of the financial years ended 30 June 2010, 30 June 2011 and 30 June 2012, the value of atorvastatin sales in Australia under the PBS exceeded $700 million. In the financial year ended 30 June 2013, the value of atorvastatin sales in Australia under the PBS exceeded $500 million.

35 In around late 2002 or early 2003, disputes arose between Pfizer Inc and certain of its subsidiary companies and interests, including Pfizer and Warner-Lambert, on the one hand, and Ranbaxy India and certain of its subsidiary and affiliate companies including Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd (Ranbaxy Australia), on the other hand, regarding amongst other things:

(a) The validity of certain patents owned by corporations in the Pfizer group of companies, including the atorvastatin patent; and

(b) Whether entities in the group of companies of which Ranbaxy Australia was a member could lawfully distribute atorvastatin in Australia.

36 As part of the settlement of these disputes, certain entities in the Pfizer group of companies and certain entities in the Ranbaxy group of companies entered into an agreement in about May or June 2008 (Ranbaxy Agreement). The Ranbaxy Agreement provided for, or had the effect that, Ranbaxy Australia could:

(a) Commence manufacturing, importing and stockpiling its own generic atorvastatin product in Australia from 18 November 2011; and

(b) Commence marketing and selling its own generic atorvastatin product in Australia from 18 February 2012, being a date three months prior to the expiry of the atorvastatin patent.

37 The arrangement was that Ranbaxy Australia was permitted to proceed in accordance with the Ranbaxy Agreement without fear of being sued by any entity in the Pfizer group of companies alleging infringement of the atorvastatin patent. This arrangement meant that Ranbaxy Australia would have a head start of three months over other suppliers of generic atorvastatin in Australia who could not commence supply until 18 May 2012, at the earliest.

38 At par 18 of the ASC, the following matters were pleaded in respect of the PBS, namely:

Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme

At all material times:

(a) the Federal Government subsidised the costs of pharmaceuticals under the PBS for certain medical conditions;

(b) the PBS was governed by the Health Act;

(c) the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits for Approved Pharmacists and Medical Practitioners (PBS Schedule) listed all pharmaceuticals available to be dispensed to general members of the public at Government-subsidised prices, known in the industry as the patient co-payment contribution, being an amount fixed by the Federal Government as the maximum price a Community Pharmacy can charge a general member of the public for a pharmaceutical listed on the PBS Schedule (Patient Co-Payment);

(d) upon a pharmaceutical being listed on the PBS Schedule, the maximum price that a supplier could charge Community Pharmacies for the pharmaceutical (Chemist List Price) was fixed by the Federal Government;

(e) where a Community Pharmacy dispensed, pursuant to the PBS, a pharmaceutical listed on the PBS Schedule to a general member of the public, the Community Pharmacy was entitled to be paid by the Federal Government a subsidy (PBS Subsidy) being:

i. the ‘PBS dispensed price’, determined by the sum of:

A. the Chemist List Price;

B. the prescribed pharmacy mark-up which, since 1 July 2010 has been prescribed by the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (FCPA) and given legal effect by the Commonwealth Price (Pharmaceutical Benefits supplied by Approved Pharmacists) Determination 2010 (the Determination);

C. the prescribed dispensing fee payable on both ready prepared and extemporaneously prepared pharmaceuticals listed on the PBS Schedule, which since 1 July 2010 has been prescribed by the FCPA and given effect by the Determination; and

D. any other relevant prescribed fees listed on the PBS Schedule, which since 1 July 2010 have been prescribed by the FCPA and given effect by the Determination,

less

ii. the Patient Co-Payment;

(f) payment of the PBS Subsidy was administered by Medicare Australia (Medicare) and a Community Pharmacy could claim from Medicare the PBS Subsidy on pharmaceuticals sold by it on a monthly basis;

(g) when the first generic version of an originator pharmaceutical was listed on the PBS Schedule (First-Listed Generic), a mandatory reduction of 16% was applied to the Chemist List Price for the originator pharmaceutical (Mandatory Reduction);

Particulars

Section 99ACB of the Health Act.

(h) a First-Listed Generic was only able to be listed on the PBS Schedule on 1 April, 1 August or 1 December of each calendar year;

(i) new generic brands of a pharmaceutical subsequent to a First-Listed Generic could be listed on the PBS Schedule on the 1st day of the month in each calendar year; and

(j) the PBS provided for a safety net, pursuant to which a general member of the public, once their accumulated eligible Patient Co-Payment contributions met a prescribed threshold within a calendar year, would be entitled to be charged a lower Patient Co-Payment for the balance of that calendar year through either purchasing pharmaceuticals listed on the PBS Schedule using a PBS Safety Net card or claiming a refund (Safety Net).

39 The facts and matters concerning the PBS pleaded in par 18 of the ASC constitute an accurate and helpful summary of the important features of the PBS. All of those facts and matters were admitted by Pfizer in its Defence (as to which, see par 18).

40 At all material times, manufacturers and wholesalers of atorvastatin were prohibited from supplying atorvastatin directly to members of the public in Australia. The supply of atorvastatin in Australia was, and is, restricted in all States and Territories to pharmacists dispensing in accordance with a prescription, medical practitioners and other designated persons, and does not include manufacturers and wholesalers of pharmaceuticals.

41 At all relevant times, atorvastatin was available for purchase by members of the public only from community pharmacies in Australia. Persons wishing to purchase atorvastatin had first to obtain a prescription for atorvastatin from a medical practitioner or, alternatively, from 1 September 2010, from a nurse practitioner authorised to prescribe PBS medicines and then by subsequently arranging to have that prescription filled by a pharmacist at a community pharmacy.

42 At all relevant times, there were in excess of 5,000 community pharmacies in Australia, almost all of which had a demand for, and acquired, atorvastatin.

43 At all relevant times, a pharmacist was not permitted lawfully to fill a prescription for atorvastatin with another pharmaceutical nor could a pharmacist lawfully fill a prescription for another pharmaceutical with atorvastatin. According to the ACCC (as to which see par 24 of the ASC), no other pharmaceutical supplied to community pharmacies was substitutable for atorvastatin. Pfizer took issue with this last proposition at par 24 of its Defence.

44 The total volume of atorvastatin required by community pharmacies:

(a) Was determined by prescriptions issued by medical practitioners or, from 1 September 2010, by a nurse practitioner authorised to prescribe PBS medicines; and

(b) Was effectively a derived level of demand.

45 Atorvastatin was distributed nationally by suppliers to community pharmacies and for the most part was imported by suppliers.

46 At par 27 of the ASC, the ACCC alleged that, by reason of the matters pleaded in pars 21 to 26 of the ASC … “at all material times there was an Australia-wide market for the supply of atorvastatin to, and acquisition of atorvastatin by, Community Pharmacies (Atorvastatin Market)”.

47 The atorvastatin market as defined in the ASC was the only market relied upon by the ACCC as the relevant market in which the impugned conduct occurred. This was the case for the alleged s 46 contraventions as well as for the alleged s 47 contraventions. The ACCC did not allege that there was an Australia-wide market for the supply of statins to, and the acquisition of statins by, community pharmacies. The relevant market relied upon by the ACCC was a one product market although, in respect of the period after 18 February 2012 (at the latest), not a one brand market.

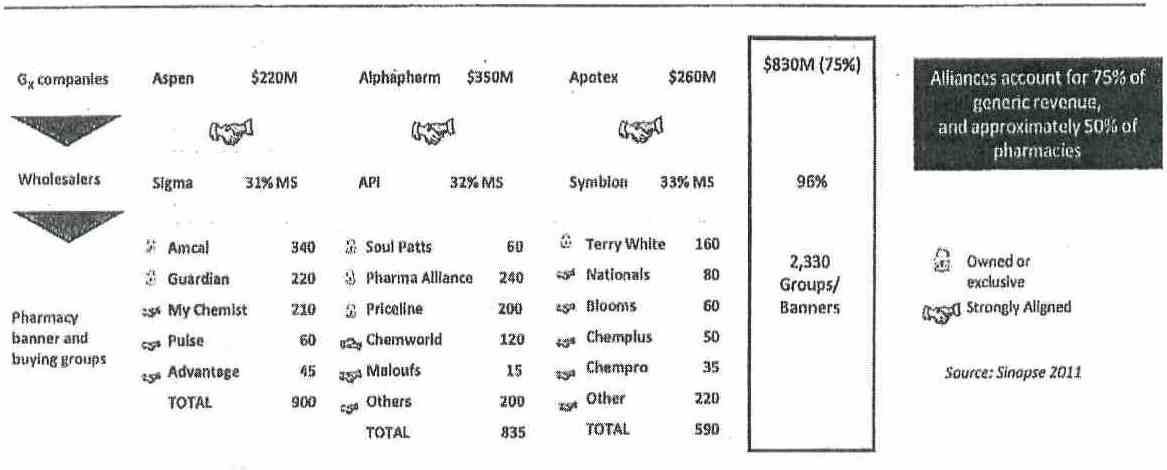

48 In its Defence, Pfizer took issue with the ACCC’s definition of the relevant market. At pars 27A to 27J of its Defence, Pfizer pleaded facts and matters in support of its counter-allegation that the relevant market was a market for the wholesale supply of pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products to community pharmacies in Australia. Those paragraphs were in the following terms:

27A. At all material times there were in Australia manufacturers and importers of pharmaceutical products, including atorvastatin (Manufacturers).

Particulars

The Manufacturers included Alphapharm Pty Ltd, Apotex Pty Ltd, Ascent Pharma Pty Ltd, Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd,

Dr Reddy’s Laboratories (Australia) Pty Ltd, Generic Health Pty Ltd, Glaxosmithkline Pty Ltd, Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd,

Merck Sharpe & Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd,

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd,

Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd, Sandoz Pty Ltd, Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd,

Spirit Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd and STADA Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd.

27B. At all material times there were in Australia wholesalers of products typically sold in Community Pharmacies, namely pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter or ‘OTC’ products.

Particulars

The wholesalers included API Limited, Sigma Pharmaceuticals Limited and Symbion Pty Ltd (Wholesalers) and, from 31 January 2011, Pfizer.

27C. At all material times Manufacturers supplied pharmaceutical products to wholesalers.

27D. At all material times Wholesalers supplied products typically sold in Community Pharmacies, namely pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products, to Community Pharmacies.

27E. The services provided by Wholesalers included warehousing and distribution of products typically sold in Community Pharmacies, namely, pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products.

27F. At all material times Wholesalers offered Community Pharmacies prices, discounts, rebates, credits, allowances or benefits to encourage Community Pharmacies to:

(a) purchase all or most of their pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products from that Wholesaler; and/or

(b) maximise as far as possible their purchases of pharmaceutical and over-thecounter products from that Wholesaler.

27G. A wholesaler is eligible tor payments from the Community Service Obligation Pool administered by the Commonwealth Government if that wholesaler meets certain service standards, including supplying any brand of PBS Medicine (as defined in the Community Service Obligation Funding Pool Operational Guidelines), not the subject of an exclusive supply arrangement, to any Community Pharmacy that requests it, within 24 hours.

27H. At all material times each of the Wholesalers was eligible for payments from the Community Service Obligation Pool.

27I. At all material times Community Pharmacies supplied pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products to members of the public.

27J. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 27A to 27I above, at all material times there was a market for the wholesale supply of pharmaceutical products and over-the-counter products to Community Pharmacies in Australia (the Wholesale Market).

49 Throughout its Defence, as necessary, Pfizer consistently denied the existence of the atorvastatin market and relied upon the wholesale market, as defined in par 27J of its Defence, as the relevant market in which the impugned conduct took place. So, for example, when the ACCC alleged at par 28 of the ASC that Lipitor was supplied by Pfizer in the atorvastatin market, Pfizer admitted that Lipitor was supplied by Pfizer but denied the existence of the alleged atorvastatin market. Both of the competing definitions of the relevant market were confined to Australia. They both were nonetheless said to operate Australia-wide.

50 At all relevant times, there was significant and sustained demand from community pharmacies for Lipitor. The prices charged by Pfizer for the supply of Lipitor to community pharmacies were significantly higher than the prices charged for the supply of generic atorvastatin to community pharmacies when those products became available.

51 From about 16 January 2012, atorvastatin Pfizer, a generic atorvastatin manufactured by Pfizer, was offered for supply and subsequently supplied by Pfizer in the atorvastatin market.

52 In about June 2011, the size and shape of Lipitor tablets supplied to community pharmacies by Pfizer changed from a large oval form to a smaller round form. Atorvastatin Pfizer tablets were the same size, shape and colour and were manufactured and packed in the very same factory, as Lipitor, as it was supplied from January 2012.

53 From 18 February 2012, Ranbaxy Australia supplied a generic atorvastatin, Trovas, or offered Trovas for supply, in the atorvastatin market, as it was lawfully permitted to do under the Ranbaxy Agreement.

54 Atorvastatin Pfizer and Trovas were both listed on the PBS Schedule on 1 April 2012. This was the earliest date that those pharmaceuticals could be listed on that Schedule.

55 In the circumstances, community pharmacies could not receive any PBS Subsidy and members of the public would not receive any Safety Net Benefit associated with any supply of atorvastatin Pfizer or Trovas to members of the public before 1 April 2012.

56 On and from the expiry of the atorvastatin patent on 18 May 2012, manufacturers and importers other than Pfizer and Ranbaxy Australia were no longer prevented by the atorvastatin patent from offering and supplying generic atorvastatin in the atorvastatin market. According to Pfizer, some manufacturers or importers promoted their generic atorvastatin prior to 19 May 2012.

57 At pars 38 and 39 of the ASC, the ACCC pleaded the following matters:

38. The following brands of Generic Atorvastatin, supplied by the following manufacturers or importers of atorvastatin, were listed on the PBS Schedule from 1 June 2012, which was the earliest date (after the expiry of the Atorvastatin Patent) on which those brands could have been listed:

(a) Lorstat, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Alphapharm Pty Ltd (Alphapharm);

(b) APO-Atorvastatin, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Apotex Pty Ltd (Apotex);

(c) Chemmart Atorvastatin, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Apotex;

(d) Terry White Chemists Atorvastatin, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Apotex;

(e) Atorvachol, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Ascent Pharma Pty Ltd (Ascent);

(f) Torvastat, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd (Aspen);

(g) Atorvastatin GH, a General [sic] Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Generic Health Pty Ltd (Generic Health); and

(h) Atorvastatin Sandoz, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Sandoz Pty Ltd (Sandoz).

39. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 18 and 38 above, Community Pharmacies could not receive any PBS Subsidy and general members of the public would not receive any Safety Net benefit associated with any supply of one or more of the brands of Generic Atorvastatin referred to in paragraph 38 above to general members of the public before 1 June 2012.

58 Prior to 1 June 2012, there was a significant financial disincentive for community pharmacies to supply to members of the public one or more of the brands of generic atorvastatin referred to in par 38 of the ASC in substitution for atorvastatin Pfizer or Trovas.

59 At par 41 of the ASC, the ACCC pleaded the following matters:

The following brands of Generic Atorvastatin, supplied by the following manufacturers or importers of atorvastatin, were listed on the PBS Schedule on the following dates after 1 June 2012:

(a) Atorvastatin SCP, a General [sic] Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Dr Reddy’s Laboratories (Australia) Pty Ltd (Dr Reddy’s), which was listed on the PBS Schedule from 1 August 2012;

(b) STADA Atorvastatin, a General [sic] Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by STADA Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd (STADA), which was listed on the PBS Schedule from 1 August 2012 until 1 December 2013; and

(c) Atorvastatin SZ, a Generic Atorvastatin manufactured or imported by Sandoz, which was listed on the PBS Schedule from 1 August 2013,

(Alphapharm, Apotex, Ascent, Aspen, Dr Reddy’s, Generic Health, Sandoz and STADA are hereinafter referred to as Other Generics Suppliers).

60 The eight organisations identified in par 41 of the ASC as suppliers of generic atorvastatin together with Ranbaxy Australia comprised Pfizer’s competitors in the atorvastatin market post 18 May 2012.

61 We interpolate here that the evidence tendered at the trial established that, by June 2012, 77% of the atorvastatin market was being supplied by suppliers of generics, including by Pfizer as the supplier of atorvastatin Pfizer, its generic atorvastatin. That position continued for some time thereafter. It should also be noted that by April 2012, which was approximately one month before the expiry of the atorvastatin patent, 68% of Lipitor’s share of the atorvastatin market had been lost to atorvastatin Pfizer and, to a much lesser extent, Ranbaxy Australia’s Trovas product.

The Impugned Conduct (Paragraph 42 to Paragraph 60 of the ASC)

62 In or around late 2010, Pfizer advised community pharmacies that it:

(a) Intended to commence manufacturing and supplying generic brands of originator prescription pharmaceuticals manufactured and supplied by it and for which its patents would shortly expire, including a generic atorvastatin pharmaceutical; and

(b) Would offer community pharmacies a discount on the supply of the generic brands of prescription pharmaceuticals, including a generic atorvastatin pharmaceutical.

63 On or around 3 December 2010, Pfizer announced that it would cease to supply prescription pharmaceuticals to community pharmacies through wholesalers and would soon commence marketing and supplying prescription pharmaceuticals exclusively direct to community pharmacies.

64 Pfizer implemented its DTP model on or about 31 January 2011. It did so through a business unit known as “Pfizer Direct”.

65 On or about 31 January 2011, Pfizer established its accrual funds scheme.

66 Commencing on or about 16 January 2012, Pfizer made offers to all, or virtually all, community pharmacies in Australia that it would:

(a) Supply atorvastatin Pfizer;

(b) Provide access to rebates on the supply of Lipitor; and

(c) Give or allow discounts in relation to the supply of Lipitor and atorvastatin Pfizer,

on the terms and conditions contained in a document entitled “Atorvastatin offer Pharmacy Acceptance Form”. These offers are called “Atorvastatin Pfizer Offers” in the ASC.

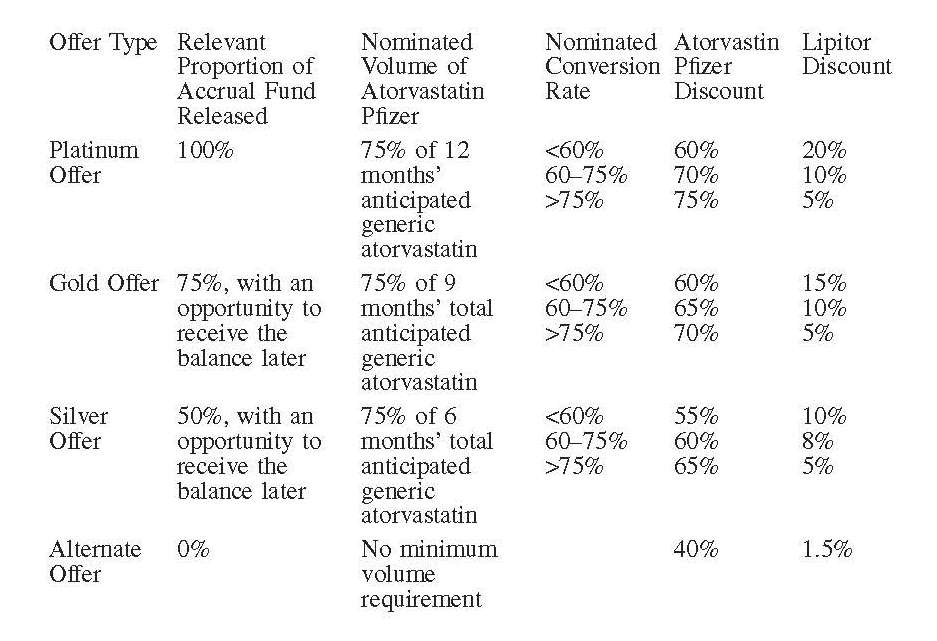

67 The detailed terms of the atorvastatin Pfizer offers are set out in par 51 of the ASC. There were four tiers of offer made: Platinum, Gold, Silver and “Alternate”. Depending on which offer type was under consideration, different rebates and discounts were offered.

68 At par 52 and par 53 of the ASC, the ACCC made the following allegations:

52. In the period up to and including 24 February 2012, the Platinum Offer, Gold Offer and Silver Offer, amongst other things, included terms and conditions to the effect that:

(a) Community Pharmacies were required to accept a Platinum Offer, a Gold Offer or a Silver Offer on or before 24 February 2012, in order to receive the relevant proportion of the Lipitor Rebate to be released as a credit on their end of month statement for April 2012;

(b) the entire Nominated Volume of Atorvastatin Pfizer was to be delivered in one shipment or multiple shipments before 30 April 2012;

(c) the discounts on Lipitor were subject to “first line support” of Atorvastatin Pfizer, in that at least 75% of the total Generic Atorvastatin volumes dispensed by a Community Pharmacy was required to be Atorvastatin Pfizer. This requirement applied from the date of a Community Pharmacy’s first delivery of Atorvastatin Pfizer until it had dispensed all of the Atorvastatin Pfizer supplied pursuant to a Platinum Offer, a Gold Offer or a Silver Offer,

(Terms and Conditions).

53. The timing of the release of the Lipitor Rebate to Community Pharmacies that accepted a Platinum Offer, a Gold Offer or a Silver Offer after 24 February 2012 was not communicated by Pfizer to Community Pharmacies until after 24 February 2012.

69 In its Defence, Pfizer denied the allegations made in par 52(a) and par 53 of the ASC. It said that it waived the requirement referred to in par 52(a) for many community pharmacies.

70 After 24 February 2012, Pfizer advised community pharmacies of the terms and conditions that would apply to the late acceptance of its atorvastatin Pfizer offers. The terms and conditions governing those late acceptances are set out at par 54 of the ASC. The effect of the late acceptance terms and conditions was to reduce the amount of the Lipitor rebate which might be accessed by a community pharmacy if the atorvastatin Pfizer offers were accepted after 24 February 2012.

71 Platinum, Gold and Silver offers were subsequently accepted by a significant number of community pharmacies.

72 Prior to 1 April 2012, Pfizer in fact supplied atorvastatin Pfizer and Lipitor to community pharmacies in accordance with the terms and conditions governing the atorvastatin Pfizer offers.

73 At par 60 of the ASC, the ACCC alleged that a substantial purpose of Pfizer in engaging in the conduct which we have summarised above was to hinder, deter or prevent other suppliers of generic atorvastatin from supplying generic atorvastatin to a substantial proportion of community pharmacies. Particulars of the evidence relied upon to prove the alleged substantial purpose were set out in par 60 of the ASC. Some of the particular matters referred to in par 60 were admitted by Pfizer. Most were denied. Pfizer denied the existence of the atorvastatin market and denied having the purpose alleged in the period to which the matters alleged in par 60 relate.

The Alleged Section 46 Contraventions (Paragraph 61 to Paragraph 67 of the ASC)

74 At par 61 of the ASC, the ACCC alleged that, from in or around June 2000 until at least 18 May 2012, Pfizer had a substantial degree of power in the atorvastatin market. Pfizer denied that it had a substantial degree of market power in the atorvastatin market. Particulars underpinning the ACCC’s allegation were set out in par 61 of the ASC.

75 At pars 62 to 65 of the ASC, the ACCC alleged that, for the reasons specified in those paragraphs, Pfizer took advantage of its substantial degree of market power in the atorvastatin market. This is also denied by Pfizer.

76 At par 65A and par 65B of the ASC, the ACCC pleaded the following matters:

65A. By structuring at least the Platinum Offer to include the Lipitor Rebates, discounts on Lipitor and discounts on Atorvastatin Pfizer, Pfizer offered and supplied Atorvastatin Pfizer to Community Pharmacies pursuant to the Terms and Conditions and the Late Acceptance Terms and Conditions below Pfizer’s forecast cost of supplying Atorvastatin Pfizer, and in some cases below a zero price, in that the sum of:

(a) the Lipitor Rebates;

(b) the incremental discounts on Lipitor (relative to the discounts offered pursuant to the Alternate Offer); and

(c) the discounts on Atorvastatin Pfizer,

offered pursuant to the Terms and Conditions and the Late Acceptance Terms and Conditions of the Platinum Offer resulted in Pfizer offering and supplying Atorvastatin Pfizer to Community Pharmacies below Pfizer’s forecast cost of supplying Atorvastatin Pfizer, and in some cases below a zero price.

Particulars

i. Document named ‘Lipitor Forecast NewStructure 20120104.xlsx’, January 2012.

ii. The ACCC repeats the particulars pleaded in relation to paragraphs 18(g) and 51 above.

65B. Further, or in the alternative, to paragraph 65 above, by reason of the matters pleaded in paragraph 65A above, Pfizer has taken advantage of its substantial degree of market power in the Atorvastatin Market in engaging in the conduct pleaded in paragraphs 50 to 59 above.

77 At pars 66 to 67A, the ACCC pleaded the following matters:

Purpose

66. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraph 60, Pfizer engaged in the conduct pleaded in paragraphs 43 to 59 above for the purpose, or for purposes that included the substantial purpose, of deterring or preventing other suppliers of Generic Atorvastatin, including Ranbaxy Australia and Other Generics Suppliers, from engaging in competitive conduct in the Atorvastatin Market.

Contraventions

67. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 42 to 53, 55 to 59, 60(a) to 60(r), 60(t) to 60(v) and 61 to 66 above, Pfizer has engaged in conduct in contravention of section 46(1) of the CCA, in that during the period between at least 1 December 2010 and 18 May 2012 Pfizer held a substantial degree of market power in the Atorvastatin Market and took advantage of that power by its conduct which cumulatively comprised:

a. the implementation of the Pharmacy Supply Arrangements;

b. the establishment of the Accrual Funds Scheme, including the Lipitor Rebates; and

c. from on or about 16 January 2012 offering to supply and subsequently supplying atorvastatin to Community Pharmacies pursuant to the Atorvastatin Pfizer Offers which included the Terms and Conditions,

for the purpose of deterring or preventing other suppliers of generic atorvastatin from engaging in competitive conduct in the Atorvastatin Market.

67A. By reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 42 to 51, 54 to 59, 60(a) to 60(g), 60(s) to 60(v) and 61 to 66 above, Pfizer has engaged in conduct in contravention of section 46(1) of the CCA, in that during the period between at least 1 December 2010 and 18 May 2012 Pfizer held a substantial degree of market power in the Atorvastatin Market and took advantage of that power by its conduct which cumulatively comprised:

a. the implementation of the Pharmacy Supply Arrangements;

b. the establishment of the Accrual Funds Scheme, including the Lipitor Rebates; and

c. from at least on or about 24 February 2012 offering to supply and subsequently supplying atorvastatin to Community Pharmacies pursuant to the Atorvastatin Pfizer Offers which included the Late Acceptance Terms and Conditions,

for the purpose of deterring or preventing other suppliers of generic atorvastatin from engaging in competitive conduct in the Atorvastatin Market.

78 In its Defence, Pfizer took issue with the proposition that it had a substantial degree of market power in the atorvastatin market in the first half of 2012 and denied that it took advantage of any market power that it had in that period or earlier for the purposes ascribed to it in the ASC.

The Alleged Section 47 Contraventions (Paragraph 68 to Paragraph 73C of the ASC)

79 The ACCC alleged at pars 68 to 73C of the ASC that, in offering to supply atorvastatin Pfizer and Lipitor to community pharmacies and by supplying those pharmaceuticals pursuant to the terms and conditions of the atorvastatin Pfizer offers, Pfizer offered, gave or allowed the discounts provided pursuant to those offers and the rebates or credits offered pursuant to those offers on the condition that community pharmacies would not, except to a limited extent, for specified periods of up to 12 months:

(a) Acquire atorvastatin directly or indirectly from a competitor of Pfizer in the atorvastatin market; or

(b) Re-supply atorvastatin acquired directly or indirectly from a competitor of Pfizer in the atorvastatin market.

80 The ACCC went on to allege that the purpose or a substantial purpose of Pfizer in engaging in that conduct was to cause a substantial lessening of competition in the atorvastatin market by:

(a) Preventing or hindering other suppliers of generic atorvastatin, including Ranbaxy Australia and other generics suppliers, from supplying generic atorvastatin to a substantial proportion of community pharmacies; and thereby

(b) Preventing or hindering other suppliers of generic atorvastatin, including Ranbaxy Australia and other generics suppliers, from competing with Pfizer for the supply of such products in the atorvastatin market.

81 The ACCC alleged that, from on or about 16 January 2012 until at least 18 May 2012, Pfizer engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing by offering to supply and subsequently supplying atorvastatin to community pharmacies pursuant to the atorvastatin Pfizer offers which included the terms and conditions for the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the atorvastatin market.

82 The ACCC ultimately alleged that this conduct constituted a breach of s 47(1) of the CCA.

83 In its Defence, Pfizer admitted offering to supply and supplying atorvastatin Pfizer and Lipitor upon the terms and conditions alleged by and relied upon by the ACCC in the ASC but denied doing so for the purpose alleged and denied engaging in the practice of exclusive dealing.

The Section 51(3) Defence (Paragraph 73D of the Defence)

84 In par 73D of the Defence, Pfizer raised a positive defence to the alleged contraventions of s 47 of the CCA based upon s 51(3) of the CCA. That paragraph was in the following terms:

By way of further defence to the alleged contraventions of s. 47 of the CCA pleaded at paragraphs 68 to 73C of the amended statement of claim, Pfizer says:

(a) At all times prior to 18 May 2012, Pfizer was a licensee of the Atorvastatin Patent pleaded at paragraph 5 of the amended statement of claim.

(b) In supplying and/or agreeing to supply Atorvastatin Pfizer and/or Lipitor to a Community Pharmacy prior to 18 May 2012 pursuant to the terms and conditions of an Atorvastatin Pfizer Offer, Pfizer granted that Community Pharmacy a licence of the Atorvastatin Patent (the “Sub-Licence”).

(c) If (which is denied) prior to 18 May 2012 Pfizer offered, gave or allowed the discounts, rebates or credits pleaded at paragraphs 69 and 70 of the amended statement of claim on the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(a) of the amended statement of claim, then:

(i) the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(a) of the amended statement of claim was a condition of the Sub-Licence;

(ii) the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(a) of the amended statement of claim related to the invention to which the Atorvastatin Patent related and/or articles made by use of that invention;

(iii) by virtue of s. 51(3) of the CCA, Pfizer did not contravene s. 47 of the CCA by imposing or giving effect to the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(a) of the amended statement of claim.

(d) If (which is denied) prior to 18 May 2012 Pfizer offered, gave or allowed the discounts, rebates or credits pleaded at paragraphs 69 and 70 of the amended statement of claim on the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(b) of the amended statement of claim, then:

(i) the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(b) of the amended statement of claim was a condition of the Sub-Licence:

(ii) the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(b) of the amended statement of claim related to the invention to which the Atorvastatin Patent related and/or articles made by use of that invention;

(iii) by virtue of s. 51(3) of the CCA, Pfizer did not contravene s. 47 of the CCA by imposing or giving effect to the condition pleaded at paragraph 71(b) of the amended statement of claim.

The Judgment of the Primary Judge—A Synopsis

85 The trial before the primary judge took fourteen hearing days. His Honour delivered a lengthy and thorough judgment in which his Honour carefully considered all of the relevant issues raised by the parties for determination at the trial.

86 As already mentioned (see, in particular, [17]–[18] above), the ACCC has advanced a substantial number of grounds of appeal in its Notice of Appeal and Pfizer, for its part, has raised a number of matters in its Notice of Contention (see [19] above).

87 In due course, we will address in detail the findings made by his Honour when dealing with the grounds of appeal and the matters raised in the Notice of Contention. In this section of our Reasons, we propose to give a relatively short synopsis of the primary judge’s judgment in order to set the scene for a more detailed consideration of the matters raised on appeal. In these Reasons, when referring to specific paragraphs in the judgment of the primary judge, we shall provide the page number in the report of the judgment at (2015) 323 ALR 429 followed by the paragraph number.

Section 46 and Section 47 of the CCA (The Law)

88 After introducing the general subject matter of and issues raised by the parties in the case, the primary judge proceeded to consider the relevant legislative provisions and the authorities which have explained and authoritatively determined the meaning of those provisions. As his Honour correctly noted at 434 [19] of his Reasons:

There was no real dispute between the parties as to the meaning and ambit of operation of these provisions. The real dispute was whether the facts fell within these provisions. It nevertheless remains important to set forth some accepted principles in respect to each provision.

89 His Honour concluded that, for all of the contraventions pleaded and relied upon by the ACCC, it was necessary to identify the market in relation to which the alleged contraventions occurred (see 435 [23] and 437 [29] of the Reasons). His Honour also observed (correctly) that, in the present case, for the purposes of the ACCC’s s 46 case, the market in which Pfizer is alleged to have had a substantial degree of power for some time (the atorvastatin market) was the same market to which the impugned conduct was directed for the requisite proscribed purpose. He also noted (correctly) that, for the purposes of the ACCC’s s 47 case, the market in which the competition was allegedly substantially lessened or intended to be substantially lessened by the impugned conduct was also the atorvastatin market. Thus, for all relevant purposes, only one market needed to be identified and defined. Although Pfizer took issue with the ACCC’s definition of the relevant market, it nonetheless accepted that only one market needed to be considered (viz the wholesale market) and conducted its case accordingly.

90 At 437–441 [29]–[37], the primary judge considered the principles which guide the Court in its determination of the relevant market for the purpose of s 46(1)(c) and for the purpose of s 47. At 437 [30], his Honour noted that the relevant market must be a market in Australia (as to which, see s 4E of the CCA and the decision of the High Court in Air New Zealand Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2017] HCA 21; (2017) 344 ALR 377 (Air NZ)).

91 The primary judge did not have the benefit of the judgment of the High Court in Air NZ. Nonetheless, with respect, he explained the relevant principles correctly. Pfizer did not contend that his Honour’s exposition of those principles contained errors or that his Honour had omitted critical points. Rather, the criticism was that his Honour had misapplied the relevant principles.

92 At 437–440 [32]–[35], his Honour considered Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 25 FLR 169 (Re QCMA) at 190; Queensland Wire Industries Proprietary Limited v The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (1989) 167 CLR 177 (Qld Wire) at 187–188; Trade Practices Commission v Australia Meat Holdings Pty Ltd (1988) 83 ALR 299 at 317; and Australian Gas Light Company v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 3) (2003) 137 FCR 317 (AGL) at 426–427 and then said (at 440–441 [35]–[37]):

Finally, reference should also be made to Australian Gas Light Co v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 3) (2003) 137 FCR 317; [2003] FCA 1525 at [378] and [379] where French J (as his Honour then was) observed:

[378] The concept of market describes, in a metaphorical way, an area or space of economic activity whose dimensions are function, product and geography. A market may be defined functionally by reference to wholesale or retail activities or a combination of both. The concept of product encompasses goods and services and, having regard to the definition of “market” in s 4E, includes the range of goods or services which are substitutable for or competitive with each other.

[379] The process of market definition was expounded in QCMA where the Tribunal defined “market” as the area of close competition between firms and observed that substitution occurs within a market between one product and another, and between one source of supply and another in response to changing prices (at 190):

“So a market is the field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers amongst whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run, if given a sufficient price incentive.”

In Re Tooth & Co Ltd (1979) 39 FLR 1, the Tribunal identified the task of market analysis as involving:

1. Identification of the relevant area or areas of close competition.

2. Application of the principle that competition may proceed through substitution of supply source as well as product.

3. Delineation of a market which comprehends the maximum range of business activities and the widest geographic area within which, if given a sufficient economic incentive, buyers can switch to a substantial extent from one source of supply to another and sellers can switch to a substantial extent from one production plan to another.

4. Consideration of longrun substitution possibilities rather than shortrun and transitory situations recognising that the market is the field of actual or potential rivalry between firms.

5. Selection of market boundaries as a matter of degree by identification of such a break in substitution possibilities that firms within the boundary would collectively possess substantial market power so that if operating as a cartel they could raise prices or offer lesser terms without being substantially undermined by the incursions of rivals.

6. Acceptance of the proposition that the field of substitution is not necessarily homogeneous but may contain submarkets in which competition is especially close or especially immediate. This is subject to the qualification that competitive relationships in key submarkets may have a wide effect upon the functioning of the market as a whole.

7. Identification of the market as multidimensional involving product, functional level, space and time.

Of particular importance in respect to each of these expositions of the concept of “market” are the continued references to goods or services which are “substitutable for or competitive with each other” and the focus upon the identification of a “field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers among whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run”. See also: Karsh, “The Role of Supply Substitutability in Defining the Relevant Product Market” (1979) 65 Virginia L Rev 129.

However the concept of a “market” may be defined, it must be recognised that “a market is not an artificial economic construct but rather a place, actual or nominal but recognisable not just by economists but also by its participants, be they suppliers or consumers, in which forces of supply and demand interact in the conduct of trade, a profession or commerce”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Ltd (2013) 307 ALR 209; [2013] FCA 1313 at [108] per Logan J.

With specific reference to the terms of s 4E, it has long been recognised that the section refers to both a market in which goods are “substitutable” and “otherwise competitive with” other goods. The “better view” as to the construction of s 4E, it has been said, “is that s 4E addresses constraints upon the supply or acquisition of the relevant goods or services” and in that context “the word ‘substitutable’ is used in a narrow sense whilst the words ‘or otherwise competitive with’ include degrees of ‘substitutability’”: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (2009) 182 FCR 160; 262 ALR 160; [2009] FCAFC 166 at [621] (Seven Network) per Dowsett and Lander JJ. However construed, s 4E confirms that the concept of substitution is basic to the process of market definition: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd [2014] FCA 1157 at [213] (Air New Zealand) per Perram J.

93 The observations which his Honour made at 440–441 [35]–[37] demonstrate that his Honour had an accurate appreciation of an appropriate working definition of market which he later applied to the facts of the case before him.

94 At 441–443 [38]–[42], his Honour considered the principles which govern the determination of the next question for s 46(1)(c) purposes viz whether the alleged contravener had, at the relevant time, “a substantial degree of power” in the relevant market.

95 At 441 [39], the primary judge noted that market power “means capacity to behave in a certain way (which might include setting prices, granting or refusing supply, arranging systems of distribution), persistently, free from the constraints of competition” (Melway Publishing Pty Limited v Robert Hicks Pty Limited (2001) 205 CLR 1 (Melway) at 27 [67] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

96 His Honour went on to observe (at 441 [40]) that a primary consideration relevant to determining whether a corporation has “market power” is whether there are barriers to entry into the relevant market (quoting from the judgment of Lockhart and Gummow JJ in Eastern Express Pty Limited v General Newspapers Pty Limited (1992) 35 FCR 43 (Eastern Express) at 62).

97 According to the primary judge, in order to have a “substantial” degree of market power, the corporation must be able to sustain its conduct over a reasonable period of time (Boral Besser Masonry Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 215 CLR 374 (Boral) at 467–468 per McHugh J). Whether the use of the word “substantial” adds much to the concept of “market power” is a matter which is open to debate. At most, it calls for a quantitative assessment of the relevant market power.

98 At 443–451 [43]–[60] of his Reasons, his Honour considered the meaning of “purpose” when used in both s 46(1)(c) and s 47(10)(a) of the CCA.

99 Although (at 443 [45]), the primary judge correctly noted that the “purpose” referred to in s 46(1) and the “purpose” referred to in s 47(10)(a) are differently expressed and invite different enquiries. He said that, in s 46(1)(c), the proscribed purpose is “… the purpose of deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct (in the relevant market)” whereas in s 47(10)(a), the proscribed purpose is “… the purpose of substantially lessening competition”.

100 At 444 [46], his Honour said that, in both provisions, the proscribed purpose must be ascertained subjectively and not objectively. In support of that proposition, he cited the judgment of the Full Court in ASX Operations Pty Ltd v Pont Data Australia Pty Ltd (No 1) (1990) 27 FCR 460 (Pont Data) at 474–475.

101 At 444 [47] of his Reasons, his Honour said:

“Purpose” is concerned with the “intent” of the corporation engaging in the impugned conduct and is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct: Dowling v Dalgety Australia Ltd (1992) 34 FCR 109 at 143; 106 ALR 75 at 110 (Dowling). Lockhart J there referred to a number of authorities, including ASX Operations, and observed:

The determination of purpose for the purposes of s 46 is to be ascertained subjectively, in the sense of ascertaining the intent of the corporation in engaging in the relevant conduct … “Purpose” in s 46 is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct, but with purpose in the sense of motivation and reason, though, as mentioned earlier, purpose may be inferred from conduct …

The same proposition was repeated by Lockhart and Gummow JJ in Eastern Express at FCR 66; ALR 320 as follows:

If a corporation has a substantial degree of power in the relevant market the question then arises whether the corporation has taken advantage of that power for one or other of the purposes proscribed by s 46(1)(a), (b) or (c). It is permissible to infer the relevant purpose under s 46: s 46(7). Further, a corporation shall be deemed to have engaged in conduct for a particular purpose if it engaged in conduct for purposes that included that purpose, and that purpose is a substantial purpose: s 4F(b). The determination of purpose for the operation of s 46 is to be ascertained subjectively, in the sense that what is to be ascertained is the intent of the corporation engaging in the relevant conduct: … “Purpose” in s 46 is not concerned directly with the effect of conduct, but with “purpose” in the sense of motivation and reason, although, as mentioned earlier, purpose may be inferred from conduct …

Lockhart J had previously observed in Dowling that purpose “will generally be inferred from the nature of the contract, the circumstances in which it was made and its likely effect”: at FCR 134; ALR 101.

102 At 444 [48], the primary judge noted that what needs to be proved is the actual purpose of the alleged contravener (Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 131 FCR 529 (Universal Music) at 588).

103 At 445 [49]–[50] of his Reasons, his Honour said:

More recently, the difference between “purpose” and “motive” has, perhaps, been slightly differently expressed. Gleeson CJ in News Ltd v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Ltd (2003) 215 CLR 563; 200 ALR 157; [2003] HCA 45 at [18] (News) observes:

[18] … The distinction between purpose and effect is significant … In a case such as the present, it is the subjective purpose … that is to say, the end they had in view, that is to be determined. Purpose is to be distinguished from motive. The purpose of conduct is the end sought to be accomplished by the conduct. The motive for conduct is the reason for seeking that end. The appropriate description or characterisation of the end sought to be accomplished (purpose), as distinct from the reason for seeking that end (motive), may depend upon the legislative or other context in which the task is undertaken …

See also: Seven Network at [851]–[858] per Dowsett and Lander JJ.

One manner in which “purpose” may well be established is if a corporation exerts pressure so as to defeat a new entrant’s attempt to gain market share and a place in the market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd (2006) ATPR 42-123; [2006] FCA 826 (Liquorland). Allsop J (as his Honour then was) there observed (at [807]):

[807] There is a danger in disembodying the debate about purpose from the evidence that is available. Even if a market is workably competitive or highly competitive, the appearance of a new entrant actively engaging in the winning of market share and recognition is the working of the competitive process. The effect of a new entrant may have a detrimental effect on the business and turnover of incumbents. That, of itself, will create competitive pressures and close competition to defeat the new entrant’s attempt to gain market share and a place in the market. There may be cases where a firm acting to prevent a new entrant can explain that by a desire divorced from competition and the competitive process. If a firm has a purpose to impede or prevent the entry of a new competitor into a market lest that new entrant conduct itself competitively to wrest business from the incumbent and so damage its business, that purpose involves the process of competition. It involves preventing entry into the market and preventing a state of affairs of lost sales through additional competitive activity. Such lost sales and damage to business will, in the ordinary course call for steps, if available, in response to meet the challenge of any new entrant. The available steps may be marginal if the market is already highly competitive. To say as much, however, is only to posit even closer, or more fierce, competition. If a purpose is to prevent or impede market entry and so to prevent competitive activity, that is sufficient it seems to me to amount to a purpose directed to the competitive process. One does not need to superadd a further purpose that the success of that purpose is to affect the degree of competitive activity as opposed merely to preserving the firm’s share of revenue in a mercantilist sense. The entry of competitors is an essential attribute of the competitive process. It is the means of access for competitive trading and for pressure on incumbent firms, through their revenue and profitability, to offer more or charge less in order to retain their places in the competitive (on this hypothesis increasingly competitive) market. If the grant of new licences were seen as a competitive threat they were so seen because they were a threat to business through competitive activity. A purpose to prevent or impede such competitive activity is a purpose concerned with the process and conduct of competition.

104 The passages which the primary judge extracted at 445 [49]–[50] of his Reasons accurately state the law as to the meaning of “purpose” when used in s 46(1)(c) and in s 47(10)(a).

105 At 445–447 [51], the primary judge noted that a proscribed purpose may be made out even though the alleged contravener maintains that it was simply seeking to win as much business as possible. In support of that proposition, his Honour referred to a paragraph in the judgment of Gyles J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd (No 2) (2008) 170 FCR 16 (Baxter) (100 [381]). “Purpose” must be distinguished from “motive” (News Limited v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited (2003) 215 CLR 563 (South Sydney) at 573 per Gleeson CJ and Baxter at 85–86 [329] per Dowsett J). So must “effect” be distinguished from “motive”.

106 At 447 [53], his Honour began his consideration of the concept of “taking advantage” when used in s 46(1). Although the concept of “taking advantage” is a notion which is separate from “purpose”, nonetheless the conduct which is alleged to constitute the relevant “taking advantage” must be for the alleged proscribed purpose if the alleged contravention is to be proven. However, the concepts are distinct. At 448–451 [54]–[60], his Honour referred to Melway, Rural Press Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 (Rural Press), Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (2009) 182 FCR 160 (C7) and other cases in this Court in support of the proposition that not all conduct engaged in by a corporation which holds market power in a particular market in order to protect its market power in that market will amount to taking advantage of that power and thus constitute a breach of s 46.

107 At 450 [59], the primary judge noted that one test that may be applied in order to determine whether a corporation has taken advantage of its market power requires a comparison between what the alleged contravener has in fact done with what it would rationally have done if it had lacked market power (Rural Press at 76 per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ and C7 at 381–382 [971]–[975] per Dowsett and Lander JJ).

108 At 451 [62] of his Reasons, his Honour explained the concept of “deterring or preventing” a person from engaging in competitive conduct as follows:

In Baxter at [317] Dowsett J said of this phrase:

[317] The words “deterring or preventing” also require attention. To “deter” is to “(r)estrain or discourage (from acting or proceeding) by fear, doubt, dislike of effort or trouble, or consideration of consequences”: see the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. The same dictionary defines the verb “prevent” as to “[s]top, hinder avoid. Forestall or thwart by previous or precautionary measures … Frustrate, defeat, make void (an expectation, plan, etc.) … Stop (something) from happening to oneself; escape or evade by timely action … Cause to be unable to do or be something, stop (foll by from doing, from being)”. The combined effect of the words “deterring” and “preventing” includes persuading a person to decide to withdraw from, not to enter or not to compete in a market, as well as making it difficult or impossible for that person to do so.

109 At 451 [63], the primary judge said:

Section 46 “requires, not merely the co-existence of market power, conduct and proscribed purpose, but a connection such that the firm whose conduct is in question can be said to be taking advantage of its power”: Melway Publishing at [44] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

110 At 451–455 [65]–[75], the primary judge examined the elements of the alleged contraventions of s 47 of the CCA.

111 Section 47(1) of the CCA prohibits the practice of exclusive dealing. At 451 [65], his Honour noted that s 47(2) provides that a corporation engages in the practice of exclusive dealing if it supplies or offers to supply goods or services on one or other of the conditions set forth in ss 47(2)(d), 47(2)(e) or 47(2)(f).

112 In the present case, the ACCC relied upon s 47(2)(d) and s 47(2)(e). The first of these subsections describes the relevant condition as a requirement that the acquirer of the relevant goods or services will not, or will not except to a limited extent, acquire goods or services directly or indirectly from a competitor of the supplier or from a competitor of a body corporate related to the supplier. The second of these subsections describes the relevant condition as a requirement that the acquirer of the relevant goods or services will not, or will not, except to a limited extent, re-supply goods or services acquired directly or indirectly from a competitor of the supplier or from a body corporate related to the supplier.

113 At 452 [66], his Honour held that a condition of the kind referred to in s 47(2) need not be legally binding but it must have “attributes of compulsion and futurity” (SWB Family Credit Union Ltd v Parramatta Tourist Services Pty Ltd (1980) 48 FLR 445 at 464 per Northrop J).

114 At 452–453 [67], the primary judge held that the mere fact that a likely consequence is exclusion (in the sense described in s 47(2)) is not sufficient. In support of this proposition, his Honour cited Monroe Topple & Associates Pty Ltd v Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (2002) 122 FCR 110 at 130 per Heerey J). In that case, Heerey J said (at 138–139 [105]):

… For a trader to offer products A and B for a single price which might make the consumer more inclined to purchase the package and not buy a competing trader’s product B is not to impose any sort of condition within the meaning of s 47(2).

115 The primary judge then turned his attention (at 453 [68]) to the concept of “… substantially lessening competition …” in s 47(10).

116 At 453–454 [71], his Honour quoted the well-known passage from the judgment of Smithers J in Dandy Power Equipment Pty Ltd v Mercury Marine Pty Ltd (1982) 64 FLR 238 (Dandy) at 259–260. There, Smithers J said: