FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73

Table of Corrections | |

[33]: at the end of the first sentence, “s 45(2)(a)(ii)” is changed to “s 45(2)(b)(ii)”. | |

22 May 2018 | [69]: “should not accepted” is changed to “should not be accepted”. |

22 May 2018 | [73]: “Manson CJ” is changed to “Mason ACJ”. |

22 May 2018 | [136]: in the quote, “the” is removed before “[the Act]”. |

22 May 2018 | [159]: “give too much weight on” is changed to “give too much weight to”. |

22 May 2018 | [223]: “the” is removed from “the course of conduct”. |

22 May 2018 | [226]: “we turn” is changed to “we turn to” |

22 May 2018 | [234]: “[41]” is changed to “[39]”; “factual specific” is changed to “factually specific”; and “(Emphasis omitted)” is added. |

22 May 2018 | [259]: “counting” is changed to “courting”. |

22 May 2018 | [261]: in the first sentence, “led to” is changed to “led”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent AUSTRALIAN ARROW PTY LIMITED (ACN 071 956 057) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Time be extended to the first respondent for the filing and serving of the notice of contention up to and including 13 March 2018 and leave be granted to rely upon said notice of contention in the appeal.

2. The appeal against the orders of the Court made on 9 May 2017 be allowed in part.

3. Order 9 of the orders made by the Court on 9 May 2017 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be ordered that under s 76(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Act) and the Competition Code as applied as a law of Victoria by s 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Vic), Yazaki Corporation pay to the Commonwealth of Australia penalties totalling $46 million in respect of contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code identified as follows:

(1) Declarations 5 and 7 (as to the 2008 Agreement): $14 million;

(2) Declaration 6.1: $12 million;

(3) Declaration 6.2: $12 million;

(4) Declaration 6.3: $4 million; and

(5) Declaration 6.4: $4 million.

4. In addition to the declarations made by the Court on 9 May 2017, it be declared after declaration 6:

6A By submitting to TMCA the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2006 Toyota Camry wire harnesses in respect of which the first respondent Yazaki had been awarded supply by TMC, AAPL gave effect to the 2003 Agreement and thereby contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

6B By submitting to TMCA the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2008 Toyota Camry wire harnesses, AAPL gave effect to the 2008 Agreement and thereby contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

5. The notice of contention be dismissed.

6. The cross-appeal be dismissed.

7. The respondents pay the appellant’s costs of and incidental to the appeal, cross-appeal and notice of contention.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction and background facts

1 This is an appeal and cross-appeal (also involving an application by the respondents to file, serve and rely upon a notice of contention) against declarations and orders, including civil penalties totalling $9.5 million, made by a judge of the Court in relation to a cartel concerning the supply of wire harnesses for motor vehicles between two Japanese corporations: Yazaki Corporation (Yazaki) and Sumitomo Electric Industries Ltd (SEI) and their wholly owned Australian subsidiaries, Australian Arrow Pty Ltd (AAPL) and SEWS Australia Pty Ltd (SEWS-A), respectively. The primary judge delivered two judgments: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 2) [2015] FCA 1304; 332 ALR 396 (liability judgment) and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 3) [2017] FCA 465 (relief judgment). For the reasons that follow we would allow the appeal, dismiss the cross-appeal and re-fix the penalties to be imposed on Yazaki in a total amount of $46 million. Our disagreements with the primary judge are focused upon matters of statutory construction, the evaluation and identification of a market with the advantage of recent High Court authority, and the legal characterisation of the conduct of Yazaki and SEI. The task on appeal was made significantly easier than it otherwise might have been by the clear, precise and comprehensive reasons of the primary judge after a factually complex and hard-fought trial. Also, the Court is grateful to counsel on the appeal for the quality of their assistance in argument.

2 Yazaki and AAPL were the respondents to the proceeding brought by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). SEI and SEWS-A co-operated with the ACCC in its investigation, and most of the evidence of the contravening conduct came from officers or employees of SEI and SEWS-A.

3 Wire harnesses are electrical systems that distribute power and electrical signals to other components in a motor vehicle. Different types of wire harnesses control different functions and parts of the vehicle. For instance, an engine wire harness is mounted on top of the engine and controls the engine; the engine room main wire harness is placed around the engine cavity and controls headlights, hazard lights and indicators; floor wire harnesses control the seats; and door wire harnesses control functions on the doors. For this proceeding the most important wire harness was the engine room main wire harness.

4 Globally, the main manufacturers of wire harnesses were three Japanese corporations: Yazaki, SEI and Furukawa Co Ltd; and two United States’ corporations: Lear Corporation and Delphi.

The commencement of the cartel – the Overarching Cartel Agreement

5 The relevant conduct between Yazaki and SEI began by at least the mid-1990s when they entered into an arrangement or understanding referred to in the liability judgment as the Overarching Cartel Agreement, which dealt with their agreed mutual response to any request for quotation (or RFQ) from motor vehicle manufacturers for wire harnesses. The evidence was confined to conduct in relation to requests for quotations issued from time to time by Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) or its related companies. The evidence also concerned TMC or a related company seeking proposals from suppliers outside requests for quotations for price revisions, which were described as price down requests.

6 The Overarching Cartel Agreement contained provisions that when an RFQ was issued to them, Yazaki and SEI would meet and discuss the request; that they would seek to agree upon the intended allocation of wire harnesses to be supplied by them and their subsidiaries to the manufacturers in the various countries in which the model was manufactured; that after agreeing on the allocation of wire harnesses to the various markets, they would agree upon the prices that they or their subsidiaries would submit to the manufacturer in the relevant country; and that the prices would be such as to ensure, as far as was possible, that the manufacturer would award supply contracts for wire harnesses in accordance with the agreed allocation between Yazaki and SEI. It was alleged by the ACCC that there were two further provisions of the Overarching Cartel Agreement: that once the contract was awarded to one, the other would not compete in relation to supply; and that each would keep the arrangement secret. The primary judge concluded that the evidence did not support findings in that regard, though he said that such could in a sense be readily implied. There can be no doubt, however, that the arrangement was surreptitious and kept hidden from TMC, and indeed from Yazaki’s subsidiary AAPL. Such “competition” as occurred was contrived by reference to prices they agreed in order to encourage TMC to choose the agreed incumbent.

7 No relief was sought by the ACCC in relation to the making of the Overarching Cartel Agreement; rather it was sought in relation to the giving effect to it.

8 In addition to the Overarching Cartel Agreement, the ACCC alleged and the primary judge found three other contravening agreements, arrangements or understandings: the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, made by the Australian subsidiaries of Yazaki and SEI, and the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement, made by Yazaki and SEI. The making of or arriving at the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement were also the giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement. Further, various conduct by Yazaki in 2003 and 2011 which we describe below was found to be giving effect to the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement, respectively.

The arrangement or understanding between the subsidiaries: the AAPL and SEWS-A 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement

9 In April 2003, AAPL and SEWS-A made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding about a request for quotation that was issued by TMC’s Australian subsidiary, Toyota Motor Corporation Limited (TMCA) to SEWS-A in connection with a minor model change to the 2002 Toyota Camry. This arrangement or understanding between the two subsidiaries, referred to as the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, concerned the supply of the engine room main wire harness. The provisions of this agreement were that as AAPL was the incumbent supplier to TMCA of the engine room main wire harness for the 2002 Camry, SEWS-A would not, in its response to the RFQ, attempt to win supply of the wire business; that AAPL would provide SEWS-A with the price at which AAPL then supplied the engine room main wire harness to TMCA; and that then SEWS-A would determine itself or in conjunction with AAPL a price to be submitted by SEWS-A to TMCA, sufficiently higher than AAPL’s price to ensure, as far as was possible, that TMCA did not award supply under the RFQ to SEWS-A.

10 In May 2003, AAPL gave effect to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement by providing SEWS-A with its prevailing prices at which it supplied engine room main wire harnesses to TMCA; and by discussing with SEWS-A the extent to which SEWS-A’s prices should exceed AAPL’s.

The 2003 Agreement between Yazaki and SEI

11 Meanwhile, in May 2003, in Japan, the 2003 Agreement was made between Yazaki and SEI. TMC sought bids for the supply of wire harnesses to TMC for a new model of the Toyota Camry to be introduced in 2006. The bids were to be from five locations: Japan, the United States of America, Australia, Thailand and Taiwan. SEI became aware that TMC were dissatisfied with Yazaki because of some quality problems. SEI had another competitive edge in that it had been selected by TMC to provide certain parts for two other models, which parts were related to the engine room main wire harness. Yazaki and SEI representatives met in June. They discussed formally the “dominant principle” of their existing overall cartel arrangement that each should maintain its respective market shares and prevent price erosion, but in relation to this RFQ they recognised TMC’s expectations of SEI, and Yazaki’s quality issues. The discussions dealt with the allocation of regions by price variations. At [159] of the liability judgment, the agreement was described as follows:

(1) with respect to supply in Australia, SEI was to “win” by around 1% including customs duty;

(2) with respect to supply in North America, Yazaki was to “win” by 2-3% approximately;

(3) with respect to supply in Japan, Yazaki was to “win” by 1-2% approximately; and

(4) with respect to supply in Thailand, Yazaki was to “win” by 2-3%.

12 The 2003 Agreement contained provisions that Yazaki and SEI would discuss and attempt to agree, in respect of each 2006 Toyota Camry manufacturing location, the prices for the 2006 Toyota Camry wire harnesses to be submitted in response to TMC’s RFQ of May 2003; that these prices would be agreed with a view to ensuring, as far as possible, that TMC awarded supply of wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry in each manufacturing location to the incumbent supplier of equivalent wire harnesses for the 2002 Toyota Camry (in Australia, Yazaki); that they would submit the agreed prices to TMC in Japan, and that for each manufacturer’s location other than Japan, Yazaki and SEI would submit or have their subsidiaries submit to the relevant TMC subsidiary in that location the agreed prices.

13 During June and July 2003, those responsible at SEI and Yazaki met and discussed prices to implement the agreement. This involved exchanging information about component pricing and agreeing prices that would look logical to TMC. This collusion was surreptitious. Yazaki and SEI were deciding on the fine detail necessary to mislead deliberately TMC about the genuineness of both their responses.

14 Despite the arrangement, TMC awarded the supply of engine room main wire harnesses to SEI in all countries, with other supply of wire harnesses being awarded in accordance with the cartel arrangements. There were accusations by Yazaki of “double crossing” by SEI, and protestations of “innocence” by SEI.

15 The primary judge found that Yazaki gave effect to the 2003 Agreement by discussing and agreeing prices with SEI in June and July 2003 that they would submit in response to the RFQ for the 2006 Camry; by submitting the agreed prices in July to TMC; by directing AAPL to submit the agreed prices to TMCA in September and October 2003; and by causing AAPL to submit the agreed prices to TMCA in October 2003.

16 In making the arrangement or arriving at the understanding constituting the 2003 Agreement Yazaki gave effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement.

17 It will be necessary to refer in more detail to the events in Australia in 2003 in relation to the 2003 Agreement and the issuing of an RFQ by TMCA to the local subsidiaries of Yazaki and SEI in Australia, given that the decision for supply in Australia was made in Japan by TMC. It suffices to say at this point that the ACCC alleged that AAPL (not just Yazaki) gave effect to the 2003 Agreement by submitting the agreed prices to TMCA in October 2003. AAPL was not a party to the 2003 Agreement. The case of the ACCC was that AAPL did have knowledge of the cartel. The primary judge found, however, that it did not have any knowledge of the 2003 Agreement or of the Overarching Cartel Agreement. The ACCC also submitted that even without that knowledge AAPL gave effect to the 2003 Agreement. The primary judge also rejected that contention by the ACCC. That latter rejection was challenged on appeal by the ACCC.

The 2008 Agreement between Yazaki and SEI

18 The case against Yazaki and the findings in relation to the 2008 Agreement followed a similar pattern to the 2003 Agreement. In March 2008, TMC issued an RFQ for the global supply of wire harnesses for use in the manufacture of the 2011 Toyota Camry in nine locations, including Australia, and for 15 wire harness parts. At the time of the RFQ four of the 15 wire harness parts (including the engine room main wire harness) were supplied by SEI, and six by Yazaki.

19 Representatives of Yazaki and SEI met to discuss and agree upon the allocation between them and their respective subsidiaries of the supply of wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry to TMC and its subsidiaries. In May 2008, Yazaki and SEI submitted prices that they had agreed between them to TMC.

20 The primary judge found that the 2008 Agreement was made out and contained the same provisions, mutatis mutandis, as the 2003 Agreement (as set out at [12] above). Further, Yazaki gave effect to the 2008 Agreement by meeting with SEI and discussing and agreeing prices for wire harnesses in the 2011 Toyota Camry; by submitting those prices to TMC; and by directing AAPL to submit the prices to TMCA in Australia.

21 In making the arrangement or arriving at the understanding constituting the 2008 Agreement Yazaki gave effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement.

22 The ACCC alleged that AAPL (not just Yazaki) gave effect to the 2008 Agreement. The primary judge rejected this contention, as he had done in relation to the 2003 Agreement.

The relevant statutory provisions, the conclusions of the primary judge and the issues on the appeal, cross-appeal and notice of contention

Statutory provisions on liability

23 Sections 45(2) and 45(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Act), previously known as the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), and of the Competition Code of Victoria (the Competition Code) were in the following terms:

45 Contracts, arrangements or understandings that restrict dealings or affect competition

(2) A corporation shall not:

(a) make a contract or arrangement, or arrive at an understanding, if:

(i) the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding contains an exclusionary provision; or

(ii) a provision of the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding has the purpose, or would have or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition; or

(b) give effect to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, whether the contract or arrangement was made, or the understanding was arrived at, before or after the commencement of this section, if that provision:

(i) is an exclusionary provision; or

(ii) has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition.

(3) For the purposes of this section and section 45A, competition, in relation to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, means competition in any market in which a corporation that is a party to the contract, arrangement or understanding or would be a party to the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or any body corporate related to such a corporation, supplies or acquires, or is likely to supply or acquire, goods or services or would, but for the provision, supply or acquire, or be likely to supply or acquire, goods or services.

24 The phrase “exclusionary provision” referred to in ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) was the subject of s 4D as follows:

4D Exclusionary provisions

(1) A provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, shall be taken to be an exclusionary provision for the purposes of this Act if:

(a) the contract or arrangement was made, or the understanding was arrived at, or the proposed contract or arrangement is to be made, or the proposed understanding is to be arrived at, between persons any 2 or more of whom are competitive with each other; and

(b) the provision has the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting:

(i) the supply of goods or services to, or the acquisition of goods or services from, particular persons or classes of persons; or

(ii) the supply of goods or services to, or the acquisition of goods or services from, particular persons or classes of persons in particular circumstances or on particular conditions;

by all or any of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding or of the proposed parties to the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding or, if a party or proposed party is a body corporate, by a body corporate that is related to the body corporate.

(2) A person shall be deemed to be competitive with another person for the purposes of subsection (1) if, and only if, the first‑mentioned person or a body corporate that is related to that person is, or is likely to be, or, but for the provision of any contract, arrangement or understanding or of any proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, would be, or would be likely to be, in competition with the other person, or with a body corporate that is related to the other person, in relation to the supply or acquisition of all or any of the goods or services to which the relevant provision of the contract, arrangement or understanding or of the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding relates.

25 Before its repeal in 2010, s 45A provided in sub-section (1) a deeming provision in relation to conduct taken to have the purpose or to have or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition:

(1) Without limiting the generality of section 45, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, shall be deemed for the purposes of that section to have the purpose, or to have or to be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition if the provision has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, as the case may be, of fixing, controlling or maintaining, or providing for the fixing, controlling or maintaining of, the price for, or a discount, allowance, rebate or credit in relation to, goods or services supplied or acquired or to be supplied or acquired by the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding or the proposed parties to the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or by any of them, or by any bodies corporate that are related to any of them, in competition with each other.

26 The phrase “give effect to” was defined in s 4 as follows:

... in relation to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, includes do an act or thing in pursuance of or in accordance with or enforce or purport to enforce.

27 The word “market” used in s 45(3) was defined in s 4E as follows:

4E Market

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, market means a market in Australia and, when used in relation to any goods or services, includes a market for those goods or services and other goods or services that are substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, the first mentioned goods or services.

28 Yazaki’s conduct occurred substantially in Japan. Thus, the extraterritoriality provisions of the Act and the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Vic) (the CPRA) that made the Competition Code the law of Victoria became important. Section 5 of the Act was as follows:

5 Extended application of Parts IV, IVA, V, VB and VC

(1) Part IV, Part IVA, Part V (other than Division 1AA), Part VB and Part VC extend to the engaging in conduct outside Australia by bodies corporate incorporated or carrying on business within Australia or by Australian citizens or persons ordinarily resident within Australia.

29 Sections 8(1) and 8(2) of the CPRA was as follows:

8 Application of Competition Code

(1) The Competition Code of this jurisdiction applies to and in relation to –

(a) persons carrying on business within this jurisdiction; or

(b) bodies corporate incorporated or registered under the law of this jurisdiction; or

(c) persons ordinarily resident in this jurisdiction; or

(d) persons otherwise connected with this jurisdiction.

(2) Subject to subsection (1), the Competition Code of this jurisdiction extends to conduct, and other acts, matters and things, occurring or existing outside or partly outside this jurisdiction (whether within or outside Australia).

30 As to ss 5 and 8(1), the ACCC’s case was that Yazaki carried on business in Australia; ACCC’s case was also (from s 8(1)) that Yazaki was a body corporate otherwise connected with Victoria.

31 Section 84(2) of the Act, as to conduct by agents, was as follows:

84 Conduct by directors, servants or agents

...

(2) Any conduct engaged in on behalf of a body corporate:

(a) by a director, servant or agent of the body corporate within the scope of the person’s actual or apparent authority; or

(b) by any other person at the direction or with the consent or agreement (whether express or implied) of a director, servant or agent of the body corporate, where the giving of the direction, consent or agreement is within the scope of the actual or apparent authority of the director, servant or agent;

shall be deemed, for the purposes of this Act, to have been engaged in also by the body corporate.

32 The cartel provisions of the Trade Practices Amendment (Cartel Conduct and Other Measures) Act 2009 (Cth) were also relied upon. They fell to be analysed by reference to s 45(2). Debate on appeal was focussed on s 45.

The conclusions of the primary judge on liability

The satisfaction of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and (ii) and (b)(i) and (ii) by AAPL

33 The conduct of AAPL in 2003 in making the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement contravened both ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(a)(ii) and its conduct in giving effect to the arrangement or understanding contravened both ss 45(2)(b)(i) and 45(2)(b)(ii). There was no appeal from these findings.

The satisfaction of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and (ii) and (b)(i) and (ii) by Yazaki

34 Whilst no relief was sought in relation to the making of the Overarching Cartel Agreement, relief was claimed in relation to giving effect to it by making the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement. The primary judge considered, however, (at [81] of the liability judgment) that the Overarching Cartel Agreement was within the terms of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(a)(ii) and s 44ZZRD of the Act and the Competition Code. There was no appeal from that conclusion.

35 As to the 2003 Agreement, the primary judge found that its provisions had the purpose of restricting or limiting supply of wire harnesses to TMC or its subsidiaries to the incumbent supplier and so were exclusionary provisions for s 4D and so fell within s 45(2)(a)(i) and the definition of cartel provision in s 44ZZRD of the Act and Competition Code: [168] of the liability judgment; and that the provisions had the purpose or had or were likely to have the effect of controlling or maintaining or providing for the controlling or maintaining of prices for wire harnesses supplied by Yazaki and SEI and their subsidiaries to TMC and its subsidiaries for s 45A(1) and so fell within s 45(2)(a)(ii) and within s 44ZZRD in the Act and Competition Code: [179] of the liability judgment. There was no appeal from these findings.

36 The primary judge found (at [227] of the liability judgment) that the giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement by making the 2003 Agreement satisfied ss 45(2)(b)(i) and 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act and Competition Code.

37 We have already referred to the acts that comprised Yazaki giving effect to the 2003 Agreement, at [13]-[15] above, within the meaning of s 45(2)(b) of the Act. There was no appeal from this finding, though the ACCC does appeal from the conclusion by the primary judge (at [228]-[240] of the liability judgment) that AAPL did not give effect to the 2003 Agreement. The appeal is one limited to the question of construction as to whether knowledge of the prohibited arrangement or understanding is an essential element of the meaning of the phrase “give effect to”. No appeal was taken against the finding that AAPL did not have, as a matter of fact, the relevant knowledge.

38 The primary judge made substantially the same findings as to the contravention of s 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code by the making of and giving effect to the 2008 Agreement.

39 The findings as to the satisfaction of both ss 45(2)(a)(i) and (ii) and (b)(i) and (ii) must be read subject to the primary judge’s conclusions on the necessity for it to be shown that there was a relevant market in Australia for contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii), but not ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i), as to which, see below.

Extraterritoriality

40 The primary judge rejected the submission of the ACCC that Yazaki was carrying on the whole of the business of AAPL in Australia. His Honour did, however, find that because of its involvement in the supply of wire harnesses to TMCA (in effect through its close direction in giving effect to the cartel behaviour) Yazaki was, with AAPL, carrying on business in Australia in the supply of wire harnesses to TMCA, and was for those reasons connected with the jurisdiction of Victoria. There was no appeal from these findings.

The meaning of “exclusionary provision” and the relevance of the existence of a market in Australia

41 It was common ground that an element of contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) was that the provision of the arrangement or understanding had the purpose, or would have or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition, meaning by ss 45(3) and 4E, competition in a market in Australia.

42 The relevant market in Australia was asserted by the ACCC to be the supply of wire harnesses for Toyota Camry models. The primary judge found that there was no such market in Australia, on the basis that no competitive activity took place in Australia in relation to that supply, rather all rivalrous behaviour was found to have taken place in Japan.

43 The consequence of this finding was that though the other elements of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) were satisfied, there was no contravention without a finding of a relevant market.

44 The primary judge concluded that ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) were nevertheless contravened, because he concluded, contrary to the submission of Yazaki, that such contravention did not require a market in Australia.

45 Yazaki in its cross-appeal contends that the primary judge was wrong to conclude that contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) does not require proof of a market within Australia.

46 Upon the filing of the cross-appeal in this regard, the ACCC challenged in an amended notice of appeal, the primary judge’s conclusion as to there being no relevant market in Australia. The ground of appeal (ground 3A) commences, “Insofar as the issue arises by reason of the Respondents’ cross-appeal …”. No attempt was made in the amended notice of appeal to seek declarations as to contraventions of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii). The ground was defensive in nature in order to maintain the findings of contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i).

The issues on the appeal and cross-appeal on liability

47 Thus, the liability issues arising and the later structure of these reasons are as follows:

(a) Appeal grounds 1-3: Notwithstanding the (unchallenged) finding that AAPL had no knowledge of any of the relevant cartel conduct by Yazaki, did it nevertheless in the circumstances give effect to the 2003 Agreement and 2008 Agreement? This raises principally a question of statutory construction as to the phrase “give effect to” and its definition in s 4.

(b) Cross-Appeal: Whether for there to be an exclusionary provision and contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) there must be found to be a relevant market in Australia. This raises a question of statutory construction, in particular whether s 45(3) and its reference to “competition” is to govern and contribute to the meaning of the conception of an exclusionary provision in s 4D through its use of the word “competitive”.

(c) Appeal ground 3A: If the cross-appeal succeeds and a relevant market in Australia is necessary for contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i), whether there was at the relevant time a market in Australia for the supply of wire harnesses for Toyota Camry vehicles. This is substantially a question of fact and legal characterisation of facts not otherwise in dispute.

Statutory provisions on penalty

48 The Court made declarations as to the conduct by AAPL contravening ss 45(2)(a)(i) and (ii) and (b)(i) and (ii) (as to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement) and by Yazaki contravening ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i), by making the arrangements, or arriving at the understandings, with SEI constituting the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement, by giving effect to them, and by giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement by making or arriving at the 2003 Agreement and 2008 Agreement. Further, injunctive relief was also made against Yazaki. Apart from the primary judge’s refusal to make a declaration that AAPL also gave effect to the 2003 Agreement and 2008 Agreement, there was no issue on the appeal about declaratory or injunctive relief. Thus, the only relevant provision for this Court to consider on relief is s 76 concerning penalties, which was, relevantly, in the following form:

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened any of the following provisions:

(i) a provision of Part IV;

…

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Part or Part XIB to have engaged in any similar conduct.

(1A) The pecuniary penalty payable under subsection (1) by a body corporate is not to exceed:

…

(b) for each act or omission to which this section applies that relates to any other provision of Part IV—the greatest of the following:

(i) $10,000,000;

(ii) if the Court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission—3 times the value of that benefit;

(iii) if the Court cannot determine the value of that benefit—10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the period (the turnover period) of 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred; and

…

Note: For annual turnover, see subsection (5).

…

(3) If conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions of Part IV, a proceeding may be instituted under this Act against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of the provisions but a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

(4) The single pecuniary penalty that may be imposed in accordance with subsection (3) in respect of conduct that contravenes provisions to which the 2 limits in paragraphs (1A)(a) and (b) apply is an amount up to the higher of those limits.

Annual turnover

(5) For the purposes of this section, the annual turnover of a body corporate, during the turnover period, is the sum of the values of all the supplies that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have made, or are likely to make, during that period, other than:

(a) supplies made from any of those bodies corporate to any other of those bodies corporate; or

(b) supplies that are input taxed; or

(c) supplies that are not for consideration (and are not taxable supplies under section 72-5 of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999); or

(d) supplies that are not made in connection with an enterprise that the body corporate carries on; or

(e) supplies that are not connected with Australia.

(6) Expressions used in subsection (5) that are also used in the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 have the same meaning as in that Act.

The conclusions of the primary judge on relief and penalty

49 There was no debate between the parties on relief with the exception of the questions whether there should be injunctive relief against AAPL and as to the appropriate penalty. The primary judge did not grant injunctive relief against AAPL. There was no appeal by the ACCC in that regard.

50 It was not open to seek penalties for the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement or the 2003 Agreement because of the six year limitation period. Penalties were sought only in relation to the conduct concerning the 2008 Agreement and the giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement by the making of the 2008 Agreement.

51 After considering s 76(5), the primary judge concluded that the maximum penalty for each act or omission that amounted to a contravention was $10 million. This conclusion followed his Honour’s rejection of the construction of the annual turnover provision (s 76(5)), and in particular s 76(5)(d)) for which the ACCC had contended.

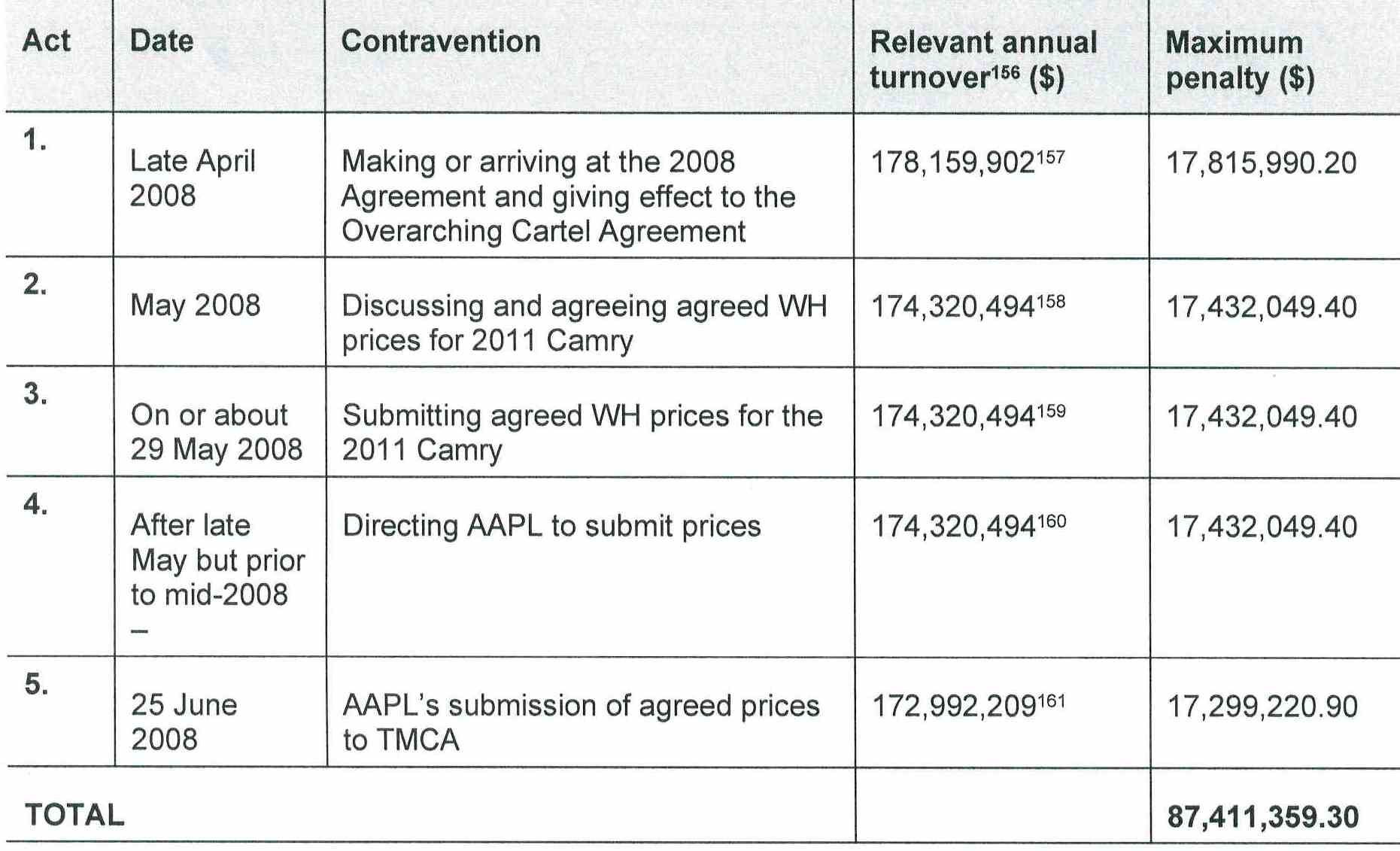

52 The ACCC had argued that there were five contraventions that were each subject to the maximum penalty which were set out in tabular form in [31] of the relief judgment, as follows:

53 The primary judge rejected Yazaki’s submissions that there was one “act” being one course of conduct for the purposes of s 76(1A)(b), and that all the contraventions were part of the same conduct within s 76(3).

54 After considering the cases dealing with so-called course of conduct, the primary judge, concluded that Yazaki’s conduct could be divided into two “broad categories”: the making of the agreements and the activity between the contraveners, on the one hand, and the submission of the prices to the purchaser, on the other. Treating these as two courses of conduct he imposed two penalties, one for each course of conduct, of $7 million and $2.5 million.

The issues on the appeal and the notice of contention on penalty

55 The penalty issues arising are as follows:

(a) Appeal grounds 4-6: Whether the primary judge misconstrued s 76(5) in concluding that the relevant maximum penalty was $10 million instead of a sum over $17 million for each contravention based on turnover.

(b) Appeal grounds 7 and 8: Whether the primary judge erred in his application of the so-called course of conduct principle by applying a maximum penalty to each course of conduct, as opposed to each contravention; and accordingly whether the aggregate maximum should have been $50 million if calculated pursuant to s 76(1A)(b)(i) or over $87 million if calculated pursuant to s 76(1A)(b)(iii), rather than $20 million.

(c) Appeal ground 9: Whether the penalties were manifestly inadequate.

(d) Notice of contention (if leave be granted to extend time to rely upon it): Whether the conduct of Yazaki in making and giving effect to the 2008 Agreement should be regarded as two “acts” for the purpose of s 76(1) and s 76(1A), or, alternatively, should be regarded as two courses of the “same conduct” for the purpose of s 76(3).

(e) If we consider there to be a material error of principle by the primary judge, what are the appropriate penalties on a reimposition of penalty by this Court?

The relevant principles of statutory construction

56 The general principles of statutory construction were not the subject of specific debate. Much emphasis, however, was placed by Yazaki, in support of its cross-appeal, on what was said to be the proper approach to the treatment of definition sections in Acts, and in particular on one aspect of the judgment of McHugh J in Kelly v The Queen [2004] HCA 12; 218 CLR 216 at [103]. We deal with that argument below. It is nevertheless appropriate to say something of legal context and so-called plain meaning. In the enquiry as to ascription of meaning, it is both permissible and necessary to examine context at the same time as considering the text of a statute. Understanding the text in its statutory, historical or legal context may suggest a meaning that a mere textual analysis does not. A summary of the proper approach (from decisions of the High Court) was conveniently stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159 at [377]-[378] as follows:

377 We have reached this conclusion through an orthodox application of the principles of statutory construction. These principles of statutory construction require a consideration of the statutory text, context and purpose: see Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [69]-[71]; Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd (2012) 250 CLR 503 at [39]; Thiess v Collector of Customs (2014) 250 CLR 664 at [22]-[23]; Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission v May (2016) 257 CLR 468 at [10]; North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory (2015) 256 CLR 569 at [11]. Statutory construction must begin and end with the statutory text: Thiess at [22] (quoting Consolidated Media Holdings at [39]). But as Gageler J observed in SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 34 (SZTAL) at [37]:

But the statutory text from beginning to end is construed in context, and an understanding of context has utility “if, and in so far as, it assists in fixing the meaning of the statutory text”.

(Footnote omitted.)

378 Similarly, Kiefel CJ and Nettle and Gordon JJ observed in SZTAL at [14]:

The starting point for the ascertainment of the meaning of a statutory provision is the text of the statute whilst, at the same time, regard is had to its context and purpose. Context should be regarded at this first stage and not at some later stage and it should be regarded in its widest sense. This is not to deny the importance of the natural and ordinary meaning of a word, namely how it is ordinarily understood in discourse, to the process of construction. Considerations of context and purpose simply recognise that, understood in its statutory, historical or other context, some other meaning of a word may be suggested, and so too, if its ordinary meaning is not consistent with the statutory purpose, that meaning must be rejected.

(Citations omitted.)

57 The relevance of the reports of law reform commissions and cognate inquiries in the examination of legal context can be seen in many cases, examples of which are CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; 187 CLR 384; Newcastle City Council v GIO General Ltd [1997] HCA 53; 191 CLR 85; Laemthong International Lines Co Ltd v BPS Shipping Ltd [1997] HCA 55; 190 CLR 181.

Did AAPL give effect to the 2003 and 2008 Agreements – the meaning of “give effect to”?

58 The primary judge held, at [229] and [231] of the liability judgment, that knowledge of the cartel arrangement comprises an essential element of the legal standard for “giving effect to” under s 45(2)(b) of the Act:

229 … The respondents do not dispute that a third party can give effect to a prohibited arrangement or understanding, but they submit that knowledge of the arrangement or understanding is an essential element of a third party's liability. They point to the following matters. First, the ACCC has assumed the obligation of proving knowledge by pleading it in its Amended Statement of Claim. I do not accept this proposition. If knowledge is not necessary as a matter of law, I do not think a party is required to prove it simply because it has pleaded it. Secondly, the respondents referred to the analogous contravention of aiding and abetting where proof of knowledge would be necessary (s 75B of the Act; Yorke and Another v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 at 667). There is force in the submission. Thirdly, the respondents submit that it could not have been the intention of Parliament to make liable the courier driver or typist who unwittingly does an act which gives effect to a prohibited arrangement or understanding. There is force in this submission.

…

231 … The two considerations identified by the respondents, the vagueness of a test involving a connection, and the fact that pecuniary penalties attend a contravention of s 45(2), lead me to conclude that knowledge of the prohibited arrangement or understanding is an essential element.

59 The primary judge on this basis concluded that knowledge of a given arrangement is a pre-requisite, as a matter of law, to an entity being capable of “giving effect to” such an arrangement for the purposes of s 45(2)(b) of the Act. The ACCC appeals this finding. The relevant grounds of appeal in the ACCC's Further Amended Notice of Appeal were as follows:

A. Liability – section 45(2)(b) – knowledge

1. His Honour erred in concluding that, for the purposes of s 45(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Act), it was necessary for the Second Respondent to have had knowledge of the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement to be held liable for giving effect to those agreements.

2. His Honour erred in failing to find that the Second Respondent contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code as applied as a law of Victoria by s 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Code), by giving effect to the 2003 Agreement by submitting to Toyota Motor Corporation Australia (TMCA) the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2006 Toyota Camry wire harnesses in respect of which the First Respondent had been awarded supply by Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC).

3. His Honour erred in failing to find that the Second Respondent contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Code, by giving effect to the 2008 Agreement by submitting to TMCA the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2008 Toyota Camry wire harnesses.

60 Based on these grounds of appeal, the question before us is whether knowledge comprises an essential element, as a matter of law, in the interpretation of “give effect to” for the purposes of s 45(2)(b) of the Act.

61 If the ACCC prevails on that point, a further question for the Court's consideration is whether the conduct of Yazaki's subsidiary AAPL in submitting agreed wire harness prices to TMCA at the direction of Yazaki suffices for the purposes of “giving effect to” the 2003 and 2008 Agreements under s 45(2)(b).

62 In paragraph 12 of the ACCC's Further Notice of Appeal, the ACCC sought declarations to the effect that:

(1) AAPL gave effect to the 2003 Agreement, and thereby contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code, by submitting to TMCA the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2006 Toyota Camry wire harnesses in respect of which Yazaki had been awarded supply by TMC.

(2) AAPL gave effect to the 2008 Agreement, and thereby contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code, by submitting to TMCA the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices for the 2008 Toyota Camry wire harnesses.

63 The ACCC submitted that the term “give effect to” in s 45(2)(b) should be given its ordinary meaning, which in turn does not require knowledge as an essential component. Rather, referring to dictionary definitions, the ACCC submitted that the term “give effect to” connotes carrying out some plan, and is broad enough to cover circumstances where a person carries out another's plan at that other person's direction without knowledge of the underlying details. In terms of the context of “give effect to” in s 45(2)(b), the ACCC submitted that no element of context served to limit its ordinary meaning by way of a knowledge requirement. More specifically, the ACCC submitted that the context afforded by the more explicit knowledge requirement in s 75B in respect of aiding and abetting sheds no light on the meaning of “give effect to”. In terms of the object and purpose of s 45(2)(b), the ACCC submitted that its function could be subverted if a subsidiary were able to avoid liability by reason of a lack of knowledge such as in the circumstances of the present case. In particular, there would be potential for foreign corporations to arrange their affairs so as to avoid liability for their conduct and the conduct of their subsidiaries by ensuring the subsidiary lacked the requisite knowledge. Conversely, the ACCC rejected the primary judge's concern that the absence of a knowledge requirement would result in liability for a courier driver or typist who unwittingly does an act that gives effect to a prohibited arrangement. Rather, cases should be determined on their facts on a case-by-case basis, and in respect of the present case, the factual position of a subsidiary is distinct from that of an unwitting third party.

64 For its part, AAPL submitted that the ordinary meaning of “give effect to” – as reflected in the dictionary definitions referred to by the ACCC as well as the definition set out in s 4 of the Act – demonstrates that it connotes at least some level of awareness of the plan being followed or carried out or enforced. This is because in order to act “in accordance with” an arrangement, or to do something “in pursuance of” it or “enforce” it, a party must have at least some level of knowledge of the arrangement. In terms of the context of the term, AAPL submitted that, to the extent there is any ambiguity in the ordinary meaning of the term, the Court should opt for a restrictive interpretation in AAPL's favour due to the pecuniary penalties attaching to s 45(2)(b). In respect of the object and purpose of s 45(2)(b), AAPL submitted that there was unlikely to be a legislative intent to expose a party acting unwittingly to a civil penalty, whereas the ACCC's construction would have the effect of exposing the unwitting delivery driver or even the victim of cartel conduct to a civil penalty. For AAPL, there was no principled way of distinguishing the coincidental or fortuitous conduct of a stranger from that of a subsidiary directed to participate by its parent, and no support in the language of s 45(2)(b) for doing so.

65 Turning to our consideration of the issue, the core principles of statutory interpretation have been set out above. Essentially we construe the term “give effect to” based on the ordinary and grammatical sense of that term, interpreted having regard to its context and the legislative purpose.

66 We say at the outset that the appropriate approach to the interpretation of penal provisions is the same task as that of construing other legislative provisions, applying established principles of statutory construction.

67 If there is a true ambiguity, the Court may resolve that ambiguity in favour of a respondent. In relation to criminal offences, Gibbs J (as he then was) in Beckwith v The Queen [1976] HCA 55; 135 CLR 569 at 576 stated:

The rule formerly accepted, that statutes creating offences are to be strictly construed, has lost much of its importance in modern times. In determining the meaning of a penal statute the ordinary rules of construction must be applied, but if the language of the statute remains ambiguous or doubtful the ambiguity or doubt may be resolved in favour of the subject by refusing to extend the category of criminal offences … The rule is perhaps one of last resort. …

68 This statement has been endorsed by the High Court in Deming No 456 Pty Ltd v Brisbane Unit Development Corporation Pty Ltd [1983] HCA 44; 155 CLR 129 at 145; and Waugh v Kippen [1986] HCA 12; 160 CLR 156 at 164. These principles equally apply to civil penalty provisions: see Trade Practices Commission v TNT Management Pty Ltd [1985] ATPR 40-512; 6 FCR 1 at 47-8 and Rich v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] HCA 42; 220 CLR 129.

69 It is to be recalled, however, that cartel provisions are to be interpreted in a way that makes their enforcement effective. Arguments based on anomaly should not be accepted if to do so would defeat the true operation of a statutory provision so intended by the Parliament.

70 Beginning with the text of the term at issue, we rely on the interpretation of “give effect to” set out in s 4 of the Act, which provides the non-exhaustive definition that “give effect to”, in relation to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, includes do an act or thing in pursuance of or in accordance with or enforce or purport to enforce. It is apparent from s 4 that “give effect to” focuses on the implementation of the contract, arrangement or understanding at issue. There is no explicit knowledge requirement in the text of s 4. Indeed, we note that neither party submitted that the ordinary meaning of “give effect to” necessarily compels a knowledge requirement. In particular, AAPL accepted that it is possible to at least construe the words “in accordance with” so as to capture actions in accordance with another’s unknown plan. Nonetheless, AAPL’s primary contention was that such an interpretation should be rejected in the present case in view of the potential implications of omitting a knowledge requirement, which could not conceivably reflect the legislative intent of the provision.

71 We agree that the ordinary meaning of “give effect to” – at least taken in isolation – does not necessarily compel a knowledge requirement. In our view, its ordinary meaning is not ambiguous in that regard. Conceptually, it is a term whose principal concern is the existence of certain conduct and whether such conduct implements, enacts, or otherwise administers an agreement. As a concept, its ordinary meaning does not immediately or necessarily evoke the subjective intentions that may underlie such conduct. Of course, in order for conduct to be said to “give effect to” an agreement, it must be demonstrated sufficiently to have been actually undertaken pursuant to, in accordance with, or otherwise enacting, implementing or administering that agreement. However, that is a question of fact rather than a matter of legal interpretation. The fact that the actor undertaking the impugned conduct had knowledge, in a subjective sense, of the scheme in question would likely be probative evidence towards satisfying the legal standard of “give effect to”. However, adducing such evidence is not necessarily the only means of satisfying the legal standard of “give effect to”, at least based on its ordinary meaning.

72 Turning then to the context of “give effect to” in s 45(2)(b) of the Act, we see nothing in the relevant contextual elements to restrict its ordinary meaning in the way contended for by AAPL.

73 Reliance by AAPL on the context in which s 75B is found and the more explicit knowledge requirement found therein does not assist in the interpretation of the term “give effect to” in the cartel provisions. The knowledge requirement was imported into the statutory accessorial liability provisions in s 75B because those provisions made use of existing criminal law concepts, and it was properly assumed that s 75B was to be interpreted consistently with the settled meaning of those concepts: see Yorke v Lucas [1985] HCA 65; 158 CLR 661, at 668 per Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ, at 673 per Brennan J. A similar approach is not apposite in the context of s 45(2)(b).

74 Further, there is no obvious reason arising from the subject matter of the provision in which this term subsists as to why subjective knowledge would be required as a matter of law. There is nothing inherently incongruent or anomalous with the proposition that an entity could play a role in giving effect to a cartel arrangement – for instance, at the direction of its controlling parent – without necessarily possessing subjective knowledge of that arrangement. Indeed, the very nature of cartel arrangements suggests that they will be surreptitious, and their principal architects may be reluctant to disclose their existence and nature to the extent such disclosure to other parties (including related parties) can be avoided.

75 We address now the legislative object and purpose of the provision, and whether it would be subverted by the respective legal interpretations advocated by the parties. A narrow interpretation would enable foreign parent companies to avoid penalties, even in the case where a subsidiary it controlled was directed to act by its foreign parent, although the subsidiary had no knowledge of the purpose of the direction. On the other hand, a broad interpretation would not necessarily capture the conduct of unwitting third parties playing an unknowing role in the implementation of a cartel agreement, such as typists and couriers.

76 As we have indicated, whether a person or entity was “giving effect to” the cartel agreement in question must be resolved on a case-by-case basis on the evidence before the Court. The circumstance of a controlling company directing or instructing its subsidiary to play a role in giving effect to a cartel agreement is as a matter of fact different in character from the incidental and fortuitous acts of a courier or typist involved only by carrying out their roles. In this proceeding, AAPL submitted to TMCA the relevant agreed prices for the Toyota Camry wire harnesses after being specifically directed to do so by Yazaki. This was sufficiently related to and connected with the cartel agreements, and was a direction given referable to the operation of those cartel agreements.

77 Having taken into account the text and context of the term “give effect to” in s 45(2)(b), as well as the object and purpose of the provision in which it subsists, we conclude that the primary judge erred in finding that for there to be a contravention, knowledge of the cartel agreements at issue on the part of the entity carrying out the impugned conduct was required to be demonstrated. This is not to suggest that such knowledge will not be relevant to the inquiry – on the contrary, we envisage such knowledge would be probative evidence in a consideration of whether the impugned conduct gave effect to any cartel agreement at issue. However, we conclude that such knowledge is not an essential element of the legal standard of “give effect to” for the purposes of s 45(2)(b).

78 Having reached this conclusion, the question remains (as raised in the Further Amended Notice of Appeal) whether AAPL in fact gave effect to the 2003 and 2008 Agreements on the basis knowledge was not an essential element of the contravention. It is apparent from the primary judge's reasons in the liability judgment that the absence of knowledge was the determinative factor in finding that AAPL did not give effect to the arrangements in question.

79 As we have said, in determining whether a person has given effect to a prohibited agreement, each case needs to be considered having regard to its own particular facts. Here, Yazaki entered into unlawful cartel agreements that necessarily would involve the conduct or participation of its Australian subsidiary AAPL for implementation: the agreements themselves related to the supply of components by its Australian subsidiary in Australia to TMCA. Further, Yazaki directed its Australian subsidiary AAPL to submit prices in accordance with the unlawful agreements and AAPL followed that direction. In these circumstances, AAPL's conduct of implementation can be characterised as being at the very least “in accordance with” the unlawful agreements entered into by Yazaki.

80 On this basis, it is appropriate to make the declarations sought by the ACCC as sought in paragraph 12 of the Further Amended Notice of Appeal in relation to the conduct of AAPL.

Is a market in Australia required for there to be an exclusionary provision?

81 By its notice of cross-appeal dated 19 June 2017, Yazaki, the first respondent, cross-appealed in relation to declarations 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and orders 8, 9 and 10 and to the part of the reasons on liability in the judgment given on 24 November 2015, in which the primary judge concluded that a market in Australia was not a necessary element of a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(i) or s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act or of the Competition Code applied as a law of Victoria by s 5 of the CPRA and accordingly found contraventions by Yazaki of those provisions.

82 The grounds of cross-appeal focused in particular on [383], [394] and [397]-[398] of the liability judgment.

83 In those paragraphs, the primary judge said, first, there was no need for the ACCC to establish a market in Australia in relation to the alleged contraventions of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i). The fact that in the general section of its Amended Statement of Claim the ACCC had pleaded a market in Australia did not preclude it from establishing contraventions of s 45(2)(a)(i) and s 45(2)(b)(i) without proving a market in Australia. Next, the primary judge concluded that there was no market in Australia for the supply of Toyota wire harnesses. The key consideration was whether all or some of the competitive activity in relation to the supply of Toyota wire harnesses in Australia took place in Australia. The primary judge did not think that it did. He said that such competitive activity as there was in relation to the supply of Toyota wire harnesses in Australia took place in Japan.

84 The primary judge then concluded:

397 The ACCC has established that Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(a)(i) by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding described in these reasons as the 2003 Agreement and that Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) by giving effect to the agreement in the manner described in these reasons. Furthermore, in making the arrangement or arriving at the understanding Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) by giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement.

398 The ACCC has established that Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(a)(i) by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding described in these reasons as the 2008 Agreement and that Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) by giving effect to the agreement in the manner described in these reasons. Furthermore, in making the arrangement or arriving at the understanding Yazaki contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) by giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement.

85 The grounds of the cross-appeal were, first, that the primary judge erred in concluding that a market in Australia was not a necessary element of a contravention of s 45(2)(a)(i) or s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act or the Competition Code. As a consequence, the primary judge erred in concluding that Yazaki contravened ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code by making and giving effect to the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement; and contravened s 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code by giving effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement by making the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement. The primary judge therefore erred in ordering Yazaki to pay a pecuniary penalty under s 76(1) of the Act and the Competition Code.

86 The circumstances were that Yazaki (or a related body corporate) and SEI (or a related body corporate) were not in competition in a market in Australia for the supply of Toyota wire harnesses. This finding is the subject of ground 3A of the ACCC’s appeal in which the ACCC contends that the primary judge erred in that finding. For present purposes we proceed on the basis that the primary judge was correct in making that finding.

87 The relevant statutory provisions were ss 45(2), 45(3), 4D and 4E that are set out above at [23], [24] and [27].

88 Yazaki submitted that the single issue on its cross-appeal was whether a contravention of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) required the agreement containing the exclusionary provision to be between competitors who were in competition in a market in Australia. Yazaki submitted that, properly construed, the answer to this question was yes. This construction was said to be supported by: (a) reading the words of the defined terms in ss 4D and 4E into s 45(2) before attempting to construe ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i). In this respect Yazaki emphasised Kelly 218 CLR 216 at [103] per McHugh J. Although McHugh J was in dissent in Kelly, it was submitted that his statement of principle has been widely endorsed, including by this Court (see e.g. Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Administrative Appeals Tribunal [2011] FCAFC 114; 195 FCR 485 at [124]-[125] and Shahid v Australasian College of Dermatologists [2008] FCAFC 72; 168 FCR 46 at [175]: “When the issue before a court is the proper construction of a statutory definition, or of a word or phrase within such a definition, the exercise necessarily involves a consideration of the definition, word or phrase as it appears when read into the substantive provisions in which it is used”; and see also Black Box Control Pty Ltd v Terravision Pty Ltd [2016] WASCA 219 at [42(11)]).

89 On the issue of construction, Yazaki relied also on: (b) consistency between the two limbs of s 45(2); (c) the common law presumption regarding the interpretation of penal legislation; (d) s 21 of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), and the common law presumptions regarding extraterritorial operation of legislation; and (e) the decisions in SPAR Licensing Pty Ltd v MIS Qld Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 1116; 298 ALR 69 and Wright Rubber Products Pty Ltd v Bayer AG [2010] FCAFC 85. Yazaki submitted that to the extent there was contrary authority (ASX Operations Pty Ltd v Pont Data Australia Pty Limited (No 2) [1991] FCAFC 179; 27 FCR 492, News Ltd v Australian Rugby Football League Ltd [1996] FCAFC 870; 64 FCR 410 and Norcast SarL v Bradken Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 235; 219 FCR 14), it was not binding on this Court, and should not be followed.

90 Yazaki submitted that all of the contravening conduct, with the exception of the submission of prices to TMCA, which was a “formality only”, took place in Japan. The agreements containing exclusionary provisions were made or arrived at in Japan between Japanese companies. Those exclusionary provisions were given effect in Japan, by the agreement and submission of prices by Japanese companies, to a Japanese company, in Japan. The anti-competitive conduct related to competitive activity in Japan.

91 Yazaki submitted it was an ordinary canon of statutory construction, given force by s 18A of the Acts Interpretation Act, that “where a word or phrase is given a particular meaning, other parts of speech and grammatical forms of that word or phrase have corresponding meanings.” The definition of “competition” in s 45(3), therefore, necessarily informed the meaning of the words “competitive with each other” in s 4D(1), once those words had been read into ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i), as they must be by reason of the inclusion of the defined term “exclusionary provision”. Also, s 4D(2) deemed a person to be competitive with another person for the purposes of s 4D(1) if that person was “in competition” with the other person, indicating a legislative intent consistent with that mandated by s 18A of the Acts Interpretation Act.

92 By s 45(3) of the Act, “competition” meant “competition in any market”. By s 4E, a “market” meant a “market in Australia.” It followed it was submitted by Yazaki that making and giving effect to a contract or arrangement containing an exclusionary provision was only proscribed if it was between persons any two or more of whom were in competition with each other in a market in Australia.

93 It was submitted by Yazaki that there was no indication in the text that the two limbs of s 45 ought to operate with differing territorial scope. Section 45 was entitled “Contracts, arrangements or understanding that restrict dealings or affect competition”, and the fact that both price-fixing and restrictive dealings were dealt with in the one section demonstrated a legislative intent that the territorial scope of the two prohibitions be the same. Further, the definition of competition in s 45(3) was expressed to be “in relation to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding”. Each limb of s 45(2) dealt with such a provision.

94 The ACCC submitted the short point of statutory construction was whether s 45(3) applied to ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) such that those sections were only contravened if two or more of the parties to the agreement containing the exclusionary provision (or their respective related bodies corporate) were in competition with each other in a “market in Australia”. It was uncontroversial that s 45(3) defined the meaning of “competition” for certain purposes, and that definition referred to competition in any market in which a party to a relevant agreement, or any related body corporate, supplied or acquired goods or services. It was also uncontroversial that the word “market” was defined in s 4E for the purposes of the Act to mean a market in Australia. The controversy was whether s 45(3) was applicable to ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i).

95 The ACCC submitted that the conclusion of the primary judge that s 45(3) was not applicable to ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) was in accordance with the plain meaning of the statutory text. Sections 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) respectively provided that a corporation shall not make a contract or arrangement, or arrive at an understanding, containing an “exclusionary provision”, and shall not give effect to such a provision. The sections did not refer to the word “market”.

96 The term “exclusionary provision” was defined in s 4D, also without reference to the word “market”. A provision of an agreement was an exclusionary provision if two conditions were satisfied (stated with simplifying abbreviations): first, the agreement containing the relevant provision must be “between persons any two or more of whom are competitive with each other” (s 4D(1)(a)). Secondly, the provision must have the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of goods or services to, or the acquisition of goods or services from, particular persons or classes of persons by all or any of the parties to the agreement or a related body corporate (s 4D(1)(b)).

97 The phrase “competitive with” in s 4D(1)(a) was, the submission continued, exhaustively defined by s 4D(2), which provided (again stated with simplifying abbreviations): that a person will be deemed to be competitive with another person for the purposes of s 4D(1) if, and only if, the first mentioned person (or a related body corporate) was likely to be in competition with the other person (or a related body corporate) in relation to the supply or acquisition of all or any of the goods or services to which the relevant provision related.

98 The ACCC submitted that the result was that, when s 4D was read together with ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) in accordance with the approach to statutory interpretation described by McHugh J in Kelly, the provisions made no reference to the concept of a “market”.

99 The ACCC submitted that Yazaki’s submission involved two errors. First, the definition of “competition” in s 45(3) was expressly “[f]or the purposes of this section and section 45A”. Section 45(3) was not intended to operate as a general definition of “competition” for the purposes of the Act. That was to be contrasted with s 4(1), which contained a definition of “competition” that applied more generally “[i]n this Act, unless the contrary intention appears”. A related difficulty with Yazaki’s construction was that it would result in the term “exclusionary provision” having different meanings in different sections of the Act. Section 4D purported to define the term “exclusionary provision” “for the purposes of this Act”. That language suggested that the definition was intended to operate throughout the Act. On Yazaki’s construction, however, s 45(3) would operate to confine the meaning of “exclusionary provision” in the context of s 45(2), but the same confined meaning would not apply where the term is used outside s 45 (e.g., s 88). Such a reading would conflict with the words of general application which appeared at the beginning of the definition in s 4D.

100 Secondly, the definition of “competition” in s 45(3) was confined to the use of that word “in relation to a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding” (emphasis added by the ACCC). The effect of those words was to confine the definition in s 45(3) to the prohibitions in ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) which concerned agreements containing provisions that have the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. In contrast, exclusionary provisions, as defined in s 4D, were not provisions that depended upon an effect on competition. Exclusionary provisions were defined as provisions that prevent, restrict or limit the supply or acquisition of goods or services (s 4D(1)(b)). While the definition required the parties to the relevant agreement to be competitive with each other (s 4D(1)(a)), s 45(3) was not stated to apply “in relation to the parties to a contract, arrangement or understanding”.

101 The ACCC submitted that if there was any ambiguity in the language of s 45(3), the construction accepted by the trial judge was supported by the legislative history. The original Trade Practices Act enacted in 1974 contained a definition of the word “market” in s 4(1): ‘“market’ means a market in Australia”. The Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the Trade Practices Bill 1974 (Cth) stated that: “The extent to which the legislation will operate extra-territorially is indicated in clause 5. The definition of market in clause 4 is also relevant in this regard.” At that time, the prohibition in s 45 against agreements in restraint of trade made reference to the effect on competition of the restraint (ss 45(3) and 45(4)), but did not refer to competition in a “market”. Various prohibitions in the original Pt IV of the Act referred to competition or competitive effects in a “market” (such as ss 46, 47 and 50) while others did not (ss 45, 48 and 49). Thus, the word “market” was not the primary extraterritorial limitation within the original Act; that work was performed by s 5.

102 Sections 4D and 4E were introduced, and s 45 was amended, by the Trade Practices Amendment Act 1977 (Cth), which followed upon the presentation in August 1976 of the report of the Trade Practices Review Committee (the Swanson Committee). As to the definition of the word “market”, the Swanson Committee recommended that the definition should include reference to substitutable products. That recommendation was effected by the deletion of the definition in s 4(1) and the insertion of s 4E in its current form.

103 As to s 45, the Swanson Committee considered the then differences between s 45 (prohibiting agreements in restraint of trade that had a significant effect on competition between the parties: s 45(4)) and s 47 (prohibiting various forms of exclusive dealing that were likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in a market for goods or services: s 47(5)). The Committee stated at [4.14]:

In our view, the competitive effects of most agreements and practices should be tested by reference to a market for goods or services (the present test of sub-section 47(5)). However, we do not consider that adopting a single definition of area, for all purposes, would be an improvement to the Act. We consider that there are certain agreements in respect of which competitive effects will basically be felt between parties to the agreement, or particular competitors thereof (e.g. collective boycotts, which often affect small business). These latter-mentioned competitive effects should, in our view, be tested according to effect on competition between the parties and other persons (the present test of sub-section 45(4)). We consider that unless the Trade Practices Act recognises these distinctions it will be ineffectual and discredited in many circumstances in which it should have force.

104 The reference to “collective boycotts” was to conduct of a kind that was ultimately prohibited by ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i). With respect to such contraventions, the Swanson Committee expressly rejected the inclusion of a market element at [4.116] and [4.117]:

We consider that a collective boycott, i.e. an agreement that has the purpose of or the effect of or is likely to have the effect of restricting the persons or classes of persons who may be dealt with, or the circumstances in which, or the conditions subject to which, persons or classes of persons may be dealt with by parties to the agreement, or any of them, or by persons under their control, should be prohibited if it has a substantial adverse effect on competition between the parties to the agreement or any of them or competition between those parties or any of them and other persons.

In our view such matters are appropriate to be tested by reference to their competitive effect between parties and other persons, and not by reference to a market.

(Emphasis added by the ACCC.)

105 Thus, the ACCC submitted, the Swanson Committee recommended that conduct of the kind ultimately prohibited by ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) ought not be defined by reference to the competitive effect in a market. That recommendation was accepted by Parliament and reflected in the language of s 45 as enacted by the Trade Practices Amendment Act 1977 (Cth). The relevant Explanatory Memorandum stated:

The new section 45 prohibits contracts, arrangements or understandings which have the purpose or effect of substantially lessening competition in a market, or of effecting a collective boycott … For the purposes of the new section, effects on competition are tested by reference to a market for goods or services, in contrast with the present section which tests such effects solely by reference to the parties. There is no competition test for collective boycotts.

106 The ACCC submitted that s 45 as enacted drew a distinction between agreements that contained exclusionary provisions and agreements that contained provisions that had the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition (which included price fixing agreements under the now repealed s 45A that were deemed to have that effect). In respect of the latter types of agreements, s 45(3) defined competition as competition in any market in which a party to the agreement (or a related body corporate) supplied goods or services. In respect of the former types of agreements, the relevant competition was defined as competition between two or more parties to the agreement.

107 The legislative history, it was submitted by the ACCC, reinforced the conclusion arrived at from the language used, that s 45(3) was not intended to apply to ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i).

108 In reply, Yazaki submitted that in construing s 45(2), the first step was to read in any definitions. That exercise required the definition of “exclusionary provision” in s 4D to be read in to ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i), for the purposes of s 45, and to read the definition of “market” in s 4E in to the definition of “competition” in s 45(3). Its construction did not lead to an inconsistent use of the term “exclusionary provision” in the Act, because the only other applications of the phrase related back to s 45(2).