FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

ESCO Corporation v Ronneby Road Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 46

ORDERS

Applicant/Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant is granted leave to appeal.

2. The appeal is upheld having regard to the reasons for judgment published today.

3. The appellant is directed to submit final orders for the consideration of the Court, giving effect to the reasons for judgment, such orders to include an order that the respondent pay the appellant’s costs of and incidental to the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT

Background and Context

1 The appellant (and applicant for leave), ESCO Corporation (“ESCO”) is the applicant for the grant of an Australian standard patent entitled “Wear assembly”. The patent application is number 2011201135 (the “Patent Application” or “PA”). It was filed on 15 March 2011 as a divisional application, that is to say, the application was divided out of an earlier application (the so-called “parent” application) being Application No. AU2007241122 having a priority date of 30 March 2006.

2 Thus, the divisional application claims the same priority date as the parent application: see Ch 6A, Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the “Act”); s 79B, s 29, and s 43; Regs 3.12(1)(c) and 3.12(2C) of the Patent Regulations 1991 (Cth) (being the pre-15 April 2013 Regulations).

3 ESCO filed a Request for Examination of the Patent Application on 15 September 2011 with the result that the provisions of the Act applying to the determination of the questions in issue in these proceedings are those provisions of the Act as they stood prior to the commencement of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (the “Raising the Bar Act”) which received assent on 15 April 2012 with some provisions commencing on 15 April 2012 and 16 April 2012 and many of the provisions of that Act commencing on 15 April 2013.

4 The application was advertised as accepted by the Commissioner on 8 November 2012.

5 On 7 February 2013, the respondent, Ronneby Pty Ltd (“Ronneby”) filed opposition under s 59 of the Act to the grant of a patent to ESCO on grounds that the invention is not a patentable invention (s 59(b)) because the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, lacks novelty and does not involve an inventive step (when compared with the prior art base): s 18(1)(b) of the Act; and that the claim or claims are not clear and succinct or fairly based on matter disclosed in the specification and not fully described: s 59(c) and s 40(3) of the Act.

6 On 7 February 2013, CQMS Pty Ltd also filed opposition proceedings relying on the same grounds as Ronneby but adding a contention that the invention so far as claimed in any claim does not constitute a manner of manufacture as that term is understood.

7 On 8 February 2013, Caterpillar Inc also filed opposition proceedings in reliance on all of the grounds just mentioned and added a contention that the invention so far as claimed in any claim is not useful: s 59(b) and s 18(1)(c) of the Act.

8 On 5 February 2015, the Commissioner’s delegate rejected all grounds of opposition finding that “the claimed invention is novel, inventive, clear, fairly based, sufficient and a manner of manufacture”. Although no submissions were made by Caterpillar before the Commissioner’s delegate concerning the ground of lack of utility, the Commissioner’s delegate also found “no basis to reject the claimed invention” on that ground.

9 On 26 February 2015, Ronneby filed an appeal to this Court under s 60(4) of the Act from the delegate’s decision.

10 Such an appeal is, of course, an exercise of the Court’s original jurisdiction and is conducted as a rehearing (sometimes called, as the Full Court, Heerey, Kenny and Middleton JJ, observed in Commissioner of Patents v Sherman (2008) 172 FCR 394 (“Sherman”) at [18], a hearing de novo); Jafferjee v Scarlett (1937) 57 CLR 115 at 119-120, Latham CJ. Whatever the consequences might now be in formulating the test to be applied by the Court in determining a matter arising in a proceeding under s 60(4) as a result of the introduction into s 60 of s 60(3A) (which formed no part of the Act relevant to these proceedings), the Primary Judge correctly recognised that the court upholds the opposition only if “clearly satisfied” that the patent, if granted, would be invalid: Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Ltd (1959) 102 CLR 232 at 244 and 245; Denison Manufacturing Company v Monarch Marking Systems Inc (1983) 66 ALR 265 at 266; 76 FLR 200 at 201. Nevertheless, that question of the Court’s state of satisfaction is determined on the balance of probabilities on the basis of the evidence before the Court in the proceedings: Sherman at [21]; see generally Sherman at [18] to [24].

11 The grounds relied upon by Ronneby before the Primary Judge in opposing the grant of a patent to ESCO were want of novelty in relation to particular claims recited in the Patent Application, want of fair basis and inutility. In the result, the Primary Judge determined (by Order 1 of the Orders made on 14 June 2016 supported by Reasons for Judgment published on 27 May 2016) that the decision of the Commissioner’s delegate of 5 February 2015 be set aside to the extent that the delegate:

found that each of claims 1, 6, 7, 9 to 15 and 18 to 23 [of the Patent Application] was for a novel invention;

found that each of the claims of the Patent Application was for a useful invention;

required that [Ronneby] pay [ESCO’s] costs according to Schedule 8 of the Patent Regulations 1991 (Cth).

12 ESCO, by its appeal proceedings, seeks leave to appeal from the Orders of the Primary Judge and challenges the findings of lack of novelty and inutility as findings said to be made in error. As to the question of leave to appeal, s 158(2) of the Act provides that except with the leave of the Federal Court, an appeal does not lie to the Full Court from a Judgment or order of a single judge of this Court exercising jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from decisions or directions of the Commissioner (and thus his or her delegate). Accordingly, in these proceedings ESCO is an applicant for leave to appeal and seeks to rely upon the notice of grounds of appeal, should leave be given. In these reasons, we will simply describe ESCO, where relevant, as the appellant. The application for leave is not opposed by Ronneby.

13 Before turning to the reasons of the Primary Judge in support of the Orders made on 14 June 2016 and the grounds of appeal, it is necessary to say some things about the relevant art and the Patent Application. It will, obviously enough, be necessary to examine in some detail later in these reasons, further aspects of the patent specification and the language of the claims defining the integers and the scope of the monopoly sought by ESCO but for present purposes the following things should be noted.

14 The Patent Application is for an invention that “pertains to a wear assembly for securing a wear member to excavating equipment”: PA, para 1.

15 The Patent Application contains an “Abstract of the Disclosure” contained in the specification. The Abstract, consistent with Reg 3.3 of the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth) contains a summary of the disclosure, the claims and the drawings relevant to the technical field of art to which the invention relates, for classification purposes. We recognise, of course, that by Reg 3.3(6) the Abstract is not to be taken into account in construing the nature of the invention the subject of the specification. As a description simply of the field of art engaged by the description in the specification, the Abstract says this:

A wear assembly for excavating equipment which includes a wear member and a base each with upper and lower stabilising surfaces that are offset and at overlapping depths to reduce the overall depth of the assembly while maintaining high strength and a stable coupling. The nose and socket each includes a generally triangular-shaped front stabilising end to provide a highly stable front connection between the nose and wear member for both vertical and side loading. The lock is movable between hold and release positions to accommodate replacing the wear member when needed, and secured to the wear member for shipping and storage purposes.

16 We are confident that the references to the Abstract by the Primary Judge formed no part of his Honour’s construction of the claims which was informed by the disclosures in the specification itself and the language of the claims.

17 As to the specification, the document tells the reader that heavy excavating equipment is used in conducting digging operations in a range of environments and ground conditions often characterised by harsh conditions: PA, para 5. “Excavating buckets” or “cutterheads” are used in such digging operations: PA, para 3. The “digging edge” of heavy excavating equipment is subjected to wear and heaving loading: PA, paras 3, 4 and 5; Primary Judgment (“PJ”) at [2]. Paragraph 3 of the Patent Application tells the reader this:

Wear parts are commonly attached to excavating equipment, such as excavating buckets or cutterheads, to protect the equipment from wear and to enhance the digging operation. The wear parts may include excavating teeth, shrouds, etc. Such wear parts typically include a base, a wear member, and a lock to releasably hold the wear member to the base.

[emphasis added]

18 So far as wear parts or wear members in the form of excavating teeth are concerned, such teeth bear the abrasion, friction and wear of operating in harsh conditions under heavy loads. Paragraph 4 of the Patent Application tells the reader this:

In regard to excavating teeth, the base includes a forwardly projecting nose for supporting the wear member. The base may be formed as an integral part of the digging edge or may be formed as one or more adapters that are fixed to the digging edge by welding or mechanical attachment. The wear member is a point which fits over the nose. The point narrows to a front digging edge for penetrating and breaking up the ground. The assembled nose and point cooperatively define an opening into which the lock is received to releasably hold the point to the nose.

[emphasis added]

19 So, put simply, such wear mechanisms used in relation to excavating teeth include a base, sometimes called an adapter fixed to (often welded to) the digging edge of, for example, an excavating bucket or otherwise made an integral part of the digging edge of such a bucket. The base is shaped to form a projecting nose so as to receive a wear member shaped to a point or “front digging edge” which will engage with, penetrate and break up the ground. The base with its shaped projecting nose and the wear member placed over it cooperatively define an opening to receive a lock device so as to hold (but releasably hold) the wear member to the nose of the base.

20 However, wear members wear out over time and must be replaced (that is, removed from the fixed base and replaced with a new wear member).

21 Paragraph 5 of the Patent Application tells the reader something about design efforts to address perceived difficulties arising out of the use of “such wear members”. The author of the specification says this:

Many designs have been developed in an effort to enhance the strength, stability, durability, penetration, safety, and/or ease of replacement of such wear members with varying degrees of success.

[emphasis added]

22 Although we will return to the question of construction of the claims and the relationship between the claims and the body of the specification later in these reasons, it seems unlikely that by that short sentence, the author was doing anything other than to identify the distributed range of areas or fields of inquiry in which many design efforts have been occurring over time (with varying degrees of success) in seeking to enhance one or more of the six identified challenges in designing “such wear members” relating to excavating teeth as described in para 4.

23 Paragraphs 6 to 19 of the Patent Application all fall under the heading “Summary of the Invention”.

24 Paragraph 6 tells the reader this:

The present invention pertains to an improved wear assembly for securing wear members to excavating equipment for enhanced stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement.

[emphasis added]

25 Ronneby contended before the Primary Judge, and contends on appeal, that para 5 of the specification identifies six areas of inquiry in which many attempts have been made to develop designs addressing six perceived problems of strength, stability, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement of wear members forming part of wear assemblies, and para 6 tells the reader that ESCO has developed an “improved” wear assembly for “securing” wear members to excavating equipment for enhancement of each of the same six features recited in para 5 of the specification (the subject of varying degrees of success in the many previous design efforts to enhance those features).

26 Ronneby says that the promise of the invention (and thus the consideration for the grant of the monopoly) lies in attaining, in each of the claims, each and every one of those enhancements as the consideration for the grant of the monopoly.

27 ESCO says that as a matter of construction of para 6 in the context of the whole specification and claims, para 6 is not cast in the language of “promises”. Rather, relevant to the question of inutility, ESCO says that the language of para 6 of, “for securing wear members to excavating equipment for enhanced stability, strength, etc”, is, put simply, the language of purpose to which the described improvements are directed, as opposed to the language of promise and moreover the use of the words “pertains to” in para 6 confirms that this is a paragraph that is speaking really of generalised desiderata”: T, p 6, lns 19-22.

28 ESCO also says that even if para 6 is to be construed as containing six promises for the “present invention” of enhancing stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement, it is not necessary, as a matter of construction of the claims having regard to the specification (and as a matter of law), on the question of utility, to attain each of those promises in each of the claims. The invention, so far as claimed in any claim, is said to be “useful” for the purposes of s 18(1)(c) and s 59(b) of the Act if one or more of those promises (if they be promises) are attained by the relevant claim. Ronneby, in answer, re-asserts its contention described at [26] of these reasons and says that even if it is not necessary to find each of the six promises in each claim, it remains necessary to find each of the six promises achieved distributively over the claims and as to that matter, the findings of the Primary Judge are said to be fatal to ESCO. That is said to follow as the Primary Judge found that para 6 contains six promises and accepted at [70] of the reasons that none of the claims achieved the advantages of enhanced strength, enhanced durability or enhanced penetration. Thus, the consideration for the grant is said to fail and all claims are said to be inutile. However, we will return to these issues later in these reasons.

29 Paragraphs 7 to 12 of the Patent Application all identify “aspects” of the invention. Paragraph 13 identifies a preferred embodiment and para 14 identifies a further “aspect” of the invention.

30 Paragraph 15, upon which ESCO places emphasis as the contended true source of the promises of the Patent Application, addresses “one other aspect of the invention” in which the lock (the function of locks in the art being to releasably hold the wear member to the base (PA, para 3)) is “integrally secured” to the “wear member” for shipping and storage as a single integral component. In this aspect, the lock is maintained within the “lock opening” (of the wear member) “irrespective of the insertion of the nose [of the base] into the cavity”, which is said to result in less shipping costs, reduced storage costs and less inventory concerns.

31 The word “cavity” in para 15 is used in its general sense of an opening at the rear of the wear member designed to receive the nose of the base. The specification tells the reader that the nose of the base is inserted into a “rearwardly-opening socket” in the wear member so as to “matingly receive the nose” (when assembly is occurring: see PA, para 68.) The word “cavity” is also used in another sense in the specification as the “pocket or cavity” located in the side of the nose with which the lock, located in the “lock opening” (that is, integrally secured in a “through-hole” feature in the wear member), engages when the lock is placed in the “hold position”, or ceases to engage when the lock is placed in the “release position”. The “release position” is said by ESCO to be a pre-determined position in which the lock is fully recessed in the through-hole of the wear member which, when in that position, enables the function of releasing the wear member from the base. The “hold position” is said to be a pre-determined position in which the lock is cooperatively fully seated in the pocket or cavity of the nose which, in that position, enables the function of securing the wear member to the nose yet the lock, in either position, also remains integrally connected to the through-hole in the wear member.

32 Critically, ESCO says that because the lock is integrally connected in the through-hole in the wear member, it can be placed in the “release position” or the “hold position” independently of or irrespective of any relationship, association or connection with the base.

33 We will, later in these reasons, also seek to explain “aspects” of the invention by reference to drawings in the Patent Application to which reference was made in the course of ESCO’s submissions and we will seek to illustrate aspects of the invention by reference to small-scale model components which were uncontroversially handed up to the Court by counsel for ESCO as illustrating aspects of the invention.

34 ESCO also places emphasis on para 16 as another source (apart from para 15) of promises of the Patent Application which is in these terms:

In another aspect of the invention, the lock is releasably securable in the lock opening in the wear member in both hold and release positions to reduce the risk of dropping or losing the lock during installation. Such an assembly involves fewer independent components and an easier installation procedure.

[emphasis added]

The claims

35 There are 26 claims defining the scope of the monopoly sought to be obtained by ESCO.

36 Claim 1 is in these terms:

A wear member for attachment to excavating equipment comprising a front end to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, a rear end, a socket that opens in the rear end to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment, a through-hole in communication with the socket, and a lock integrally connected in the through-hole and movable without a hammer between a hold position where the lock can secure the wear member to the base and a release position where the wear member can be released from the base, the lock and the through-hole being cooperatively structured to retain the lock in the through-hole in each of the said hold and release positions irrespective of the receipt of the base in the socket or the orientation of the member.

37 Claims 2, 3 and 4 are dependent claims and they are in these terms:

2. A wear member in accordance with claim 1 wherein lock is secured in the through-hole for pivotal movement about a pivot axis.

3. A wear member in accordance with claim 2 wherein the pivot axis extends generally in a direction generally parallel to the receipt of the base into the socket.

4. A wear member in accordance with any one of claims 1-3 wherein the lock is free of a threaded adjustment for movement between the hold and release positions.

38 Claim 5 is in these terms:

A wear member for attachment to excavating equipment comprising a front end defining a narrow front edge for penetrating into the ground, a rear end, a socket defined by top, bottom and side walls that opens in the rear end to receive a nose fixed to the excavating equipment to define an excavating tooth, a through-hole in communication with the socket, and a lock received in the through-hole for pivotal movement between a hold position where the lock secures the wear member to the nose and a release position where the wear member can be released from the nose, wherein the pivotal axis extends in a direction generally parallel to the receipt of the base into the socket.

39 Claim 6 is in these terms:

A wear member for attachment to excavating equipment comprising a front end to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, a rear end to mount to a base fixed to the excavating equipment, and a lock movable between a hold position where the lock secures the wear member to the base and a release position where the wear member can be released from the base, wherein the lock remains secured to the wear member in the release position irrespective of whether the wear member is mounted to the base or the orientation of the wear member.

40 Claims 7 and 8 are dependent claims and they are in these terms:

7. A wear member in accordance with claim 6 including a socket that opens in the rear end to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment, and a through-hole in communication with the socket, wherein the lock is positioned within the through-hole.

8. A wear member in accordance with claims 6 or 7 wherein the lock is free of a threaded adjustment for movement between the hold and release positions.

41 Claim 9 is in these terms:

A wear member for excavating equipment comprising :

a wearable body having a wear surface to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, and a cavity to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment; and

a lock integrally secured to the wearable body for movement between a hold position wherein the lock engages the base to hold the wearable body to the base and a release position wherein the lock permits installation and removal of the wearable body on and from the base, the lock being secured to the wearable body in both the hold and release positions irrespective of whether the base is in the cavity or the orientation of the wear member.

42 Claims 10, 11 and 12 are dependent claims and they are in these terms:

10. A wear member in accordance with claim 9 wherein the lock turns about an axis less than a full turn to move between the hold and release positions.

11. A wear member in accordance with claim 9 or 10 wherein the lock is movable without a hammer between the hold and release positions.

12. A wear member in accordance with any one of claims 9-11 wherein the lock is free of a threaded connection with the wearable body.

43 Claim 13 is in these terms:

A wear assembly for attachment to excavating equipment comprising:

a base fixed to the excavating equipment;

a wear member including a front end to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, and a rear end to mount to the base fixed to the excavating equipment; and

a lock integrally connected to the wear member and movable without a hammer between a hold position where the lock contacts the base and the wear member to secure the wear member to the base and a release position where the wear member can be released from the base, wherein the lock remains secured to the wear member in the release position.

44 Claims 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 are dependent claims and they are in these terms:

14. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 13 including a rear wall portion that defines a socket in the rear end to receive the base, and a through-hole that communicates with the socket, wherein the lock is movable in the through-hole between the hold and release positions.

15. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 14 wherein the lock is alternatively secured to the wear member in the hold and release positions regardless of whether the base is received in the socket or the orientation of the wear member.

16. A wear assembly in accordance with any one of claims 13-15 wherein the lock is free of a threaded adjustment for movement between the hold and release positions.

17. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 13 or 14 wherein the base is a one piece member free of movable components.

18. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 13 or 14 wherein the base has a lock-engaging formation that is a fixed and immovable portion of the base against which the lock contacts in the hold position to secure the wear member to the base.

45 Claim 19 is in these terms:

A wear assembly for excavating equipment comprising a base fixed to the excavating equipment and a wear member having (i) a wearable body having a wear surface to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, and a cavity to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment, and (ii) a lock integrally secured to the wearable body for movement between a hold position wherein the lock engages the base to hold the wearable body to the base and a release position wherein the lock permits installation and removal of the wearable body on and from the base, the lock being secured to the wearable body in both the hold and release positions irrespective of whether the base is in the cavity or the orientation of the wearable body.

46 Claims 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24 are dependent claims and they are in these terms:

20. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 19 wherein the lock turns about an axis less than a full turn to move between the hold and release positions.

21. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 19 or 20 wherein the lock is movable without a hammer between the hold and release positions.

22. A wear assembly in accordance with any one of claims 19-21 wherein the lock is free of a threaded connection with the wearable body.

23. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 19 wherein the base has a lock-engaging formation that is a fixed and immovable portion of the base against which the lock contacts in the hold position to secure the wear member to the base.

24. A wear assembly in accordance with claim 19 wherein the base is a one piece member free of movable components.

47 Claim 25 is in these terms:

A wear assembly for excavating equipment comprising: a base fixed to the excavating equipment, the base having a nose free of moving components; a wear member including a front end to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, and a rear end having a socket for receiving the nose to support the wear member on the base; and a lock movably secured to the wear member for movement between a hold position where the lock engages the base and the wear member to secure the wear member to the base, and a release position where the wear member can be released from the base, the lock remaining secured to the wear member irrespective of receipt of the nose into the cavity or the orientation of the wear member.

48 Claim 26 is a dependent claim in these terms:

A wear assembly in accordance with claim 25 wherein the wear member includes a through-hole extending through a wall defining the socket such that the through-hole communicates with the socket, and the lock being secured within the through-hole to contact the base in the hold position.

49 As already mentioned, the Primary Judge found that claims 1, 6, 7, 9 to 15 and 18 to 23 lacked novelty and that none of the 26 claims are claims for a useful invention.

50 Returning to Claim 1, the elements or integers of the claim, according to the language of the claim, seem to be these.

51 The claim is for a wear member for attachment to excavating equipment. The wear member comprises: (a) a front end (to contact materials being excavated and to protect the excavating equipment); (b) a rear end; (c) a socket that opens in the rear end of the wear member (to receive a base fixed to excavating equipment); (d) a “through-hole” in communication with the socket; (e) a lock “integrally connected” in the through-hole and movable without a hammer; (f) between a “hold position” and a “release position”; (g) the lock and the through-hole being cooperatively structured to retain the lock in the through-hole in each of the hold and release positions; (h) irrespective of the receipt of the base into the socket of the wear member or the orientation of the wear member; (i) a “hold position” (where the lock can secure the wear member to the base); and (j) a “release position” (where the wear member can be released from the base).

52 Had the question been one of whether a third party wear member infringed Claim 1 of a patent granted on the basis of the present Patent Application, it would have been necessary for ESCO to show that each of these integers are present in the impugned wear member. Where the question is one of lack of novelty arising under s 59(b) and s 18(1)(b) of the Act on the footing of anticipation by publication of another article prior to the priority date, anticipation (and thus lack of novelty), only arises if each of the integers of Claim 1 of the Patent Application are present in the article said to anticipate the claimed invention.

53 As to that matter, ESCO says that the Primary Judge fell into error in the construction attributed to the integer concerning the “hold position” and “release position” by failing to construe the “hold position” and the “release position” of Claim 1 as requiring a fixed, certain and pre-defined position of the lock relative to the wear member in each case, where those positions are “identifiable” “independently of the base”. ESCO says that a second aspect of the claim is that one fixed or pre-determined position, the “hold position”, enables the wear member to be held to the base for operation in digging and the other fixed or pre-determined position, the release position, enables the wear member to be released from the base for replacement.

54 ESCO says that these two positions are fixed and pre-determined in the sense that, for example, Claim 1 contemplates a precise point at which the lock is either “on” or “off” much in the nature of a switch which is either on or off. The pre-determined point, in each case, is a precise (and absolute point) at which the lock is placed. When placed in the relevant position the lock is said to enable either the securing of the wear member to the base or the removal of the wear member from the base. ESCO says that the lock, integrally connected in the through-hole of the wear member, can be placed in the hold position or the release position irrespective of any engagement at all with the base. The pre-determination of each position of the lock in the wear member alone (without any necessary relationship with the base) is said to make clear the construction that the “hold position” and “release position” are fixed and pre-determined points of absolute precision.

55 ESCO also says that the Primary Judge erred in concluding that a product or device described as “Torq Lok” produced by Quality Steel Foundries Ltd (“Quality Steel”) of Nisku, Canada and disclosed publicly prior to the priority date, possessed the “hold position” and “release position” integer of Claim 1, when these terms are properly construed. ESCO says that the same proposition applies “with minor variations to claims 6, 9, 13 and 19 of the Patent Application”.

Further aspects of the specification, the drawings and the model components

56 In construing the claims of the Patent Application, we approach that matter entirely in accordance with the orthodoxy of the canons of construction as we set out at [144] to [147]. We will return briefly to those principles later in these reasons when we determine the question of construction.

57 At this point however, it is convenient to have regard to the drawings to which we were taken in submissions by ESCO simply for the purpose of illustrating some of the aspects of the base, the wear member, the lock, the through-hole in the wear member, the pocket or cavity in the side of the nose and aspects of the way, as depicted in the drawings, the lock is said to engage with the through-hole and cooperatively engage with the cavity or pocket in the side of the nose. We recognise that the drawings simply represent embodiments of the invention.

58 We, of course, construe the claims according to the language adopted by the author having regard to the orthodoxy of the principles to be applied for that purpose, on the footing that the specification is a statement addressed to persons with practical knowledge and experience in the field in which the invention is intended to be used. In making reference to the drawings we do not seek to narrow or expand the boundaries of the monopoly as fixed by the words of the claim read in the context of the specification as a whole and we recognise that some descriptions of the invention and associated figures are concerned with specific “aspects” of the invention which may, as a matter of construction of the claims, be narrower than the claims. We will come to the matter of construction later in these reasons. However, as Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ said in Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 616 (“Welch Perrin v Worrel”), the “body of the specification and the illustrations as a dictionary of the jargon” may give clarity to the meaning of the claims.

59 On that footing, we now turn to the drawings to which we were taken to by ESCO in order to provide some context to the invention.

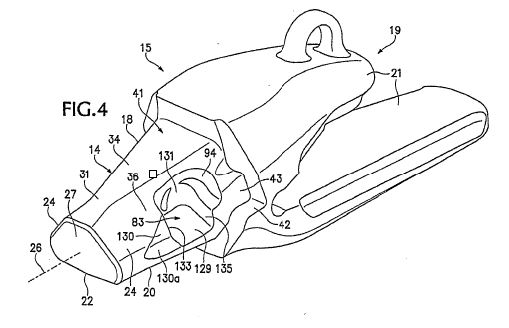

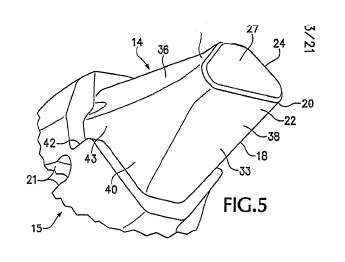

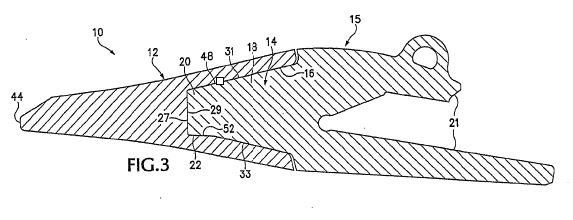

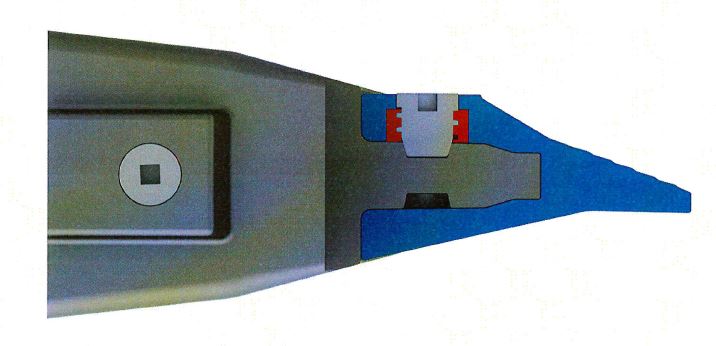

60 Figures 4 and 5 are set out below.

61 Figure 4 is an upper perspective view of a base of the wear assembly and Figure 5 is a lower perspective view of the nose of the base. These drawings show one embodiment of a base and a nose to which a wear member is adapted to fit.

62 Looking at Figure 4, on the right hand side of the drawing, the base has two legs (a pair of rearward legs marked 21) for affixing the base to a bucket in a number of common ways. The legs typically extend over and are welded to the lip of a bucket. When the base is secured to the lip of a bucket the base is typically called an “adapter”. The drawing also shows the nose of the base (marked generally 14). The body of the nose is marked 18 and the front section of the nose is marked 20. The front surface (sometimes called the front thrust surface) is marked 27. The front end of the nose has a generally triangular shape as depicted. The lower surface of the nose (the horizontal lower surface) is marked 22 and the triangulated surfaces of the nose are marked 24. Those surfaces are generally inclined facing upward and outward defining an inverted V-shape. The lower horizontal surface (22) and the front triangulated surfaces (24) represent front stabilising surfaces. The top or upper wall of the nose is marked 31.

63 Figure 4 also shows an area marked 83 in the drawing which is a pocket or cavity defined in one side of the nose. It is this cavity which is engaged by the lock when the lock, located in a “through-hole” in the wear member, is moved from the release position (once installation of the wear member has occurred) to the hold position where the lock holds the wear member to the nose and thus the base.

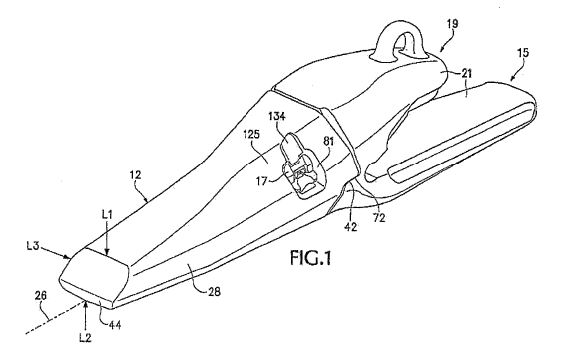

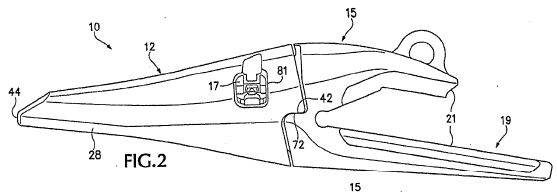

64 Figures 1, 2 and 3 are set out below.

65 Figure 1 shows a base (15) with two rearward legs (21) and a wear member marked 12 attached to the base. The front digging edge of the wear member is marked 44. Figure 3 shows the outline of the rear opening socket of the wear member marked 16. The socket is said to be preferably formed to matingly receive the nose of the base and accordingly the front end of the socket and the surfaces within it are designed to operate as stabilising surfaces in harmony with the surfaces of the nose of the base. Figures 1 and 2 show, marked 81, a cavity, opening or “through-hole” in the side wall of the wear member. The cavity is called a “through-hole” because it operates in communication with the socket passing through the side wall of the wear member (into the socket). When the wear member is placed over the nose of the base as shown in Figures 1 and 2, the through-hole will communicate with the cavity defined in one side of the nose. Thus (in one construction), the lock located in the through-hole (marked 81) in the wear member fits into a communicating pocket or cavity in the side of the nose. The cavity is marked 83 in Figure 4.

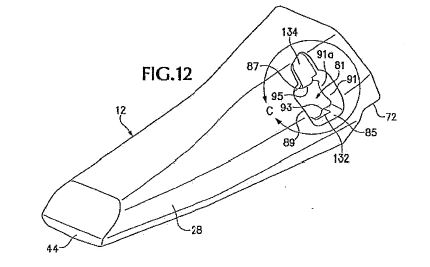

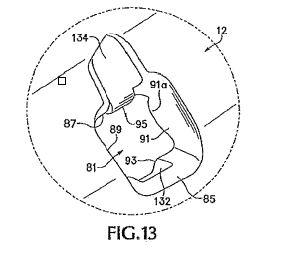

66 Figures 12 and 13 are set out below.

67 Figure 12 is a perspective view of a wear member showing in greater detail the features of the through-hole and Figure 13 is an enlarged view, within the depicted circle, of the through-hole.

68 Those illustrative general shapes depicted in the drawings need a little explanation. Through-hole 81 generally has a rectangular shape with an upper or top end wall marked 87 and a corresponding lower or end wall marked 85. It has a side wall (shown on the left hand side of the rectangular shape closest to the front of the nose) marked 89 and a corresponding rear side wall marked 91 (shown on the right hand side of the rectangular shape opposite side wall 89). The lower end wall marked 85 defines a pivot member (marked 93) in the form of a rounded “bulb”.

69 That bulb generally defines a longitudinal axis (that is, relative to the direction of the wear assembly) which, put simply, having regard to what is sometimes called the “narrow end” of the lock, cooperates with the bulb on the lower end wall (marked 85) to enable the lock, located in the through-hole, to pivotally swing or move between a hold position and a release position.

70 The amplitude of the swing or movement from the release position to the hold position and back is, in part, determined by a “stop” device marked 95 on Figures 12 and 13 (but most noticeably seen on Figure 13) on the upper end wall marked 87.

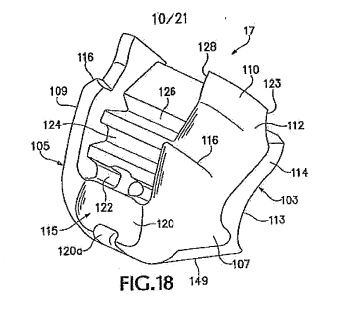

71 Figures 18 and 19 are set out below.

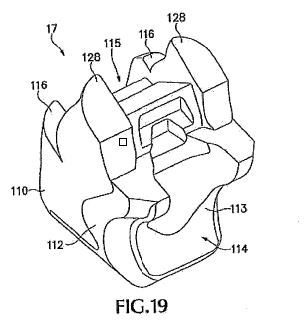

72 These figures are a perspective view of the lock. It is not necessary to describe the particular shape, contours and configuration of the lock all of which are said to have a role to play in enabling the lock to be integrally secured in the through-hole and move or pivotally swing from a hold position to a release position and back irrespective of whether the wear member is engaging with the nose of the base. However, it is necessary to say something about how the lock is said to operate in conjunction with the nose of the base and in order to do so it is necessary to have regard to Figures 22, 23, 24 and 25.

73 Before turning to those drawings, it is necessary to illustrate further the cavity in the nose. The cavity in the nose of the base with which the lock engages can be seen in Figure 4 marked 83 as already described. It can also been seen in Figure 8 set out below.

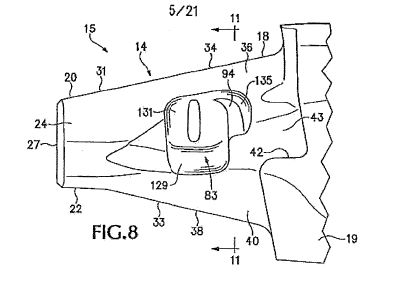

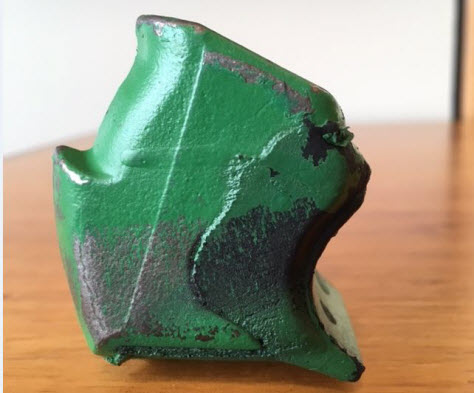

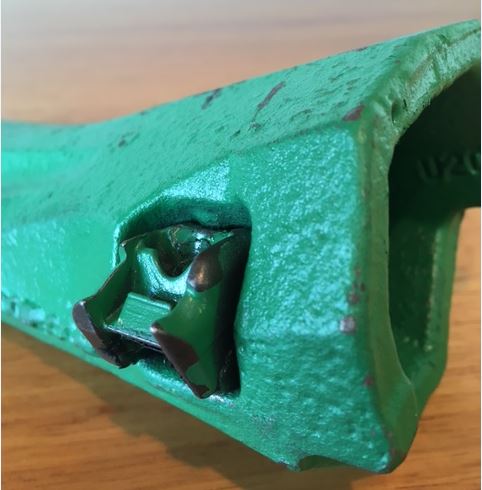

74 These figures are, of course, two dimensional drawings. The cavity, simply as a matter of illustration, can be better seen in the three dimensional small-scale model handed up to the Court. Depicted below are three photographs of the model of the base which show the projecting nose of the base with the cavity or pocket (marked 83 in Figure 4).

75 As can be seen, the cavity in the nose does not extend through the nose and thus the nose is said to retain greater strength. The lower wall of the cavity (marked 129 in Figure 8) provides a platform against which the lock can be set when engaging with the cavity. Another wall (the rear profile marked 131 in Figure 8) is shaped so as to follow the path of the lock when swung into the hold position. Depicted below is a photograph of the wear member component independent of the base.

76 The lock in the embodiment described in Figures 1-32 is said in the specification to operate in this way.

77 The lock fits into the through-hole (marked 81 on Figures 1 and 2) such that a pivot feature or pivot member of the lock bears against the bulb (earlier described and marked 93 in Figure 13) within the through-hole for effecting pivotal movement of the lock between a hold position and a release position. To secure a wear member to the nose (and thus the base) the lock is swung about the bulb in the through-hole so as to “fit fully within cavity 83” in the nose of the base (marked 83 on Figures 8 and 4). In a preferred embodiment, a tool called a pry tool is used to move the lock pivotally into the “hold position”. It is not necessary to describe the features of the fingers of the lock and the precise mechanism of engagement. The more important matter is said to be that once the lock is swung into the “hold position” the relevant features of the lock “fully fit within cavity 83” in the nose. When in that position, one of the end walls of the cavity in the nose operates as a “catch” for the lock. The configuration of the lock and opposing facet within the socket of the wear member prevents movement of the lock away from the seated hold position.

78 As earlier mentioned, Figure 4 illustrates the cavity within the nose and shows a wall of the cavity marked 133. Also, Figures 12 and 13 (and particularly Figure 13) show the rear side wall marked 91 of the rectangular shaped through-hole. When the lock is placed in the “hold position”, the front face of the lock marked 107 on Figure 18 (illustrated in the photograph below but merely as one commercial embodiment so as to show a three-dimensional image of such an embodiment; see also the three-quarter photograph below), engages with, that is, opposes the front wall of the cavity (marked 133 in Figure 4) in the nose and at the same time the rear or opposing wall of the lock engages with, that is, opposes, the rear wall (marked 91 in Figures 12 and 13 but particularly Figure 13) of the through-hole in the wear member. By reason of this engagement and opposition, the wear member is securely held to the base when the lock is placed in the “hold position”.

79 Set out below are Figures 22, 23, 24 and 25.

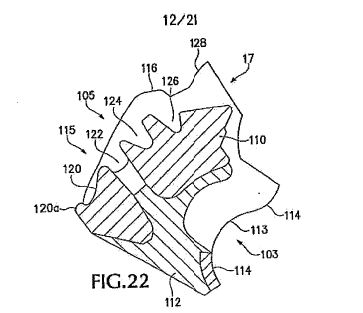

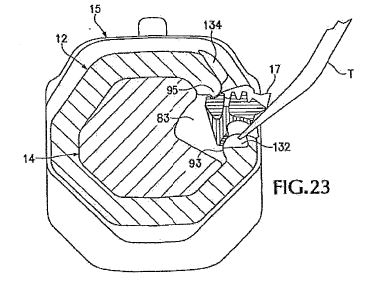

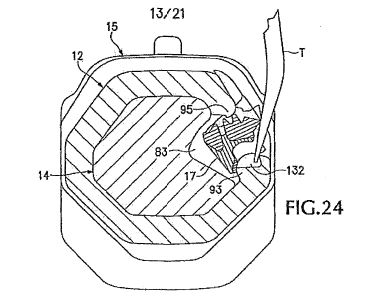

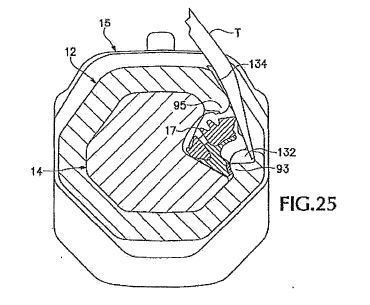

80 Figure 22 is a cross-sectional view of the lock.

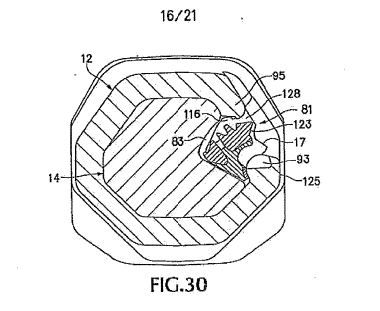

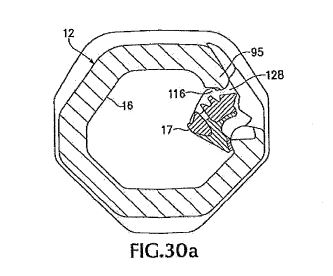

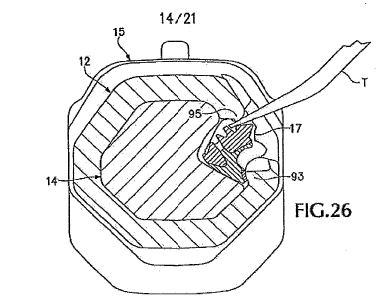

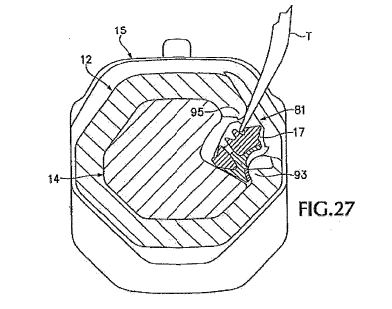

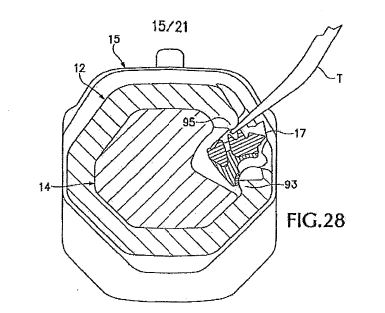

81 Figures 23, 24 and 25 are transverse cross-sectional views showing “the incremental installation of the lock” (PA, para 42), that is to say the pivotal movement of the lock using a pry tool from the release position to the hold position. Figure 23 shows a transverse cross-sectional view of the wear assembly, that is, the wear member attached to the nose of the base with the lock seated in the through-hole but not engaging with the cavity in the nose. The pry tool marked “T” can be seen ready for use to pivotally move the lock into the cavity of the nose. Figure 24 shows a “stage” of that process and Figure 25 shows the lock in the “hold position” at which point the relevant section of the lock fully fits within Cavity 83 of the nose such that the faces described at [78] are engaged (that is, opposed). Figures 30 and 30a show the lock in the hold position ready for digging operations (without, this time, the pry tool in evidence). Figures 30 and 30a are set out below.

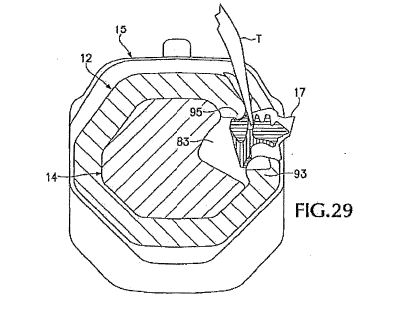

82 Figures 26, 27, 28 and 29 show the reverse process by which a pry tool is inserted at a particular point in the configuration of the lock and through-hole so as to pivotally move the lock from the “hold position” shown in Figure 26 to the “release position” shown at Figure 29.

83 Depicted below, for illustrative purposes, are two photographs of the small-scale model, marked 1 and 2, of the lock in the release and hold positions. The first photograph shows the lock secured in the through-hole of the wear member in the “release position” of Figure 29. The second photograph shows the lock in the “hold position” of Figures 30 and 30a. The difference between the two photographs and thus the position of the lock (at least as appears from an external examination of the lock in the through-hole of the wear member rather than from inside the cavity in the wear member) is that in Photograph 1, the lock can be seen to be more withdrawn within the through-hole such that two points of the lock are lower down in the image in the “release position” than the position in Photograph 2. In Photograph 2, the points of the lock are more upright as the lock sits in the “hold position” in the through-hole of the wear member.

Photograph 1

Photograph 2

84 Returning then to the language of Claim 1, ESCO says that when Claim 1 speaks of a wear member comprising (among other integers) a lock integrally connected in the through-hole (of the wear member) and movable without a hammer between a hold position “where the lock can secure the wear member to the base” and a release position “where the wear member can be released from the base”, the language defining those positions contemplates two fixed or pre-determined positions each at the extremity or end point of the amplitude of the pivotal movement of the lock. One position is called “release position” (although it might also be called an “off position”) and it is represented by a point which is the end point of the amplitude of the pivotal movement of the lock into what might be called the fully recessed or fully flush position. In that position (notwithstanding that the lock can assume that position in the wear member without receipt of the nose of the base into the socket of the wear member or any engagement of the base by the wear member), the wear member can be placed on the nose of the base just as a glove might be placed on the fingers of a hand.

85 The other position is called a “hold position” (although it might also be called an “on position”) and it is represented by a point which is the end point of the amplitude of the pivotal movement of the lock into what might be called a fully protuberant or fully extended position. In that position, when engaging with the cavity in the nose of the base (although, again, the lock can be placed in the hold position irrespective of any engagement with the base), the relevant parts of the lock fully occupy or fully fit into the cavity in the nose with the result that the wear member is secured to the base by the lock. If the lock is placed in the hold position (so understood) before engaging any relationship with the nose of the base (that is, before attempting to place the wear member on the base just as a glove might be placed on the fingers of a hand), the protuberant position of the lock prevents the wear member from being placed over the nose and thus on the base.

86 Thus, on the question of construction, ESCO says, having regard to the language of Claim 1 and informed by paras 15 and 16 of the specification, that there are “two functions” of the lock in its relationship with the wear member. The first “is to be releasably secured” in a way that means the lock will not “pop out” of the wear member and secondly, the lock performs the function of engaging with a recess in the nose so as to ensure that when installation is made, the wear member is not going to “slip off like a glove”: T, p 15, lns 10-17.

87 ESCO says that because the “hold position” and “release position” are defined by reference “only” to the through-hole in the wear member, those two positions are “identifiable” without reference to the nose and irrespective of the insertion of the nose into the rear opening socket of the wear member. Thus, the two positions do not “have to be” identified by reference to the “second function, that is to say, the insertion of the nose into the wear member”: T, p 20, lns 33-47, T, p 21, lns 1-5. The “second function” is said to “stop longitudinal movement” of the wear member from the nose but that function is said to “follow” from the position which is “independently identified by reference to the cooperation between the lock and the through-hole in the wear member”: T, p 22, lns 31-42. Counsel for ESCO put the point this way at T, p 23, lns 32-37:

… you can say that when in those positions, certain things will be possible. It will enable you to put the wear member on the nose in the release position, and it will enable you to secure the wear member to the nose in the lock position, but those two functions are facilitating installation and removal, on the one hand, and its facilitating securing on the other [does not] define the position. The position is defined by reference only to the lock and the cooperative wear member.

[emphasis added]

88 The notion that the hold and release positions are defined by reference only to the lock’s relationship with the through-hole in the wear member and not by reference to the base is said to be “emphasised” by the language “irrespective of the receipt of the base in the socket or orientation of the [wear] member” at the end of Claim 1, that is to say, the lock and the through-hole are said to be “cooperatively structured” to “retain the lock” in the through-hole and also in each of the hold and release positions irrespective of receipt of the base or the orientation of the wear member: T, p 29, lns 42-47; T, p 30, lns 1-3; T, p 32, lns 35-39. Counsel for ESCO, drew the contentions on construction together in this way at T, p 30, lns 5-15:

There are two functions of the hold and release positions in the cooperatively structured lock and through-hole. The first is the retention of the lock in the through-hole, so that it is integrally connected in the through-hole … and accordingly can achieve the advantages that are referred to in [paras] 15 and 16 [of the specification]. The second is the enablement of the securing and release of the wear member from the base. And the third thing we would say about the claim is that the language of the claim makes it plain that the hold position and release position are defined by reference only to the through-hole, but that construction is consistent with the purposes which one sees in [paras] 15 and 16, so that were there any doubt about it, a [purposive] construction would achieve the same result.

[emphasis added]

89 Finally, the lock is said to be “releasably securable” in the lock opening in the wear member (in the through-hole) such that it can be moved from one position to the other (hold or release) and yet remains “secured” in the wear member due to the cooperation between the lock and the through-hole in the wear member: T, p 31, lns 28-40.

90 Ronneby says that such a construction is not consistent with the language of Claim 1; Claim 1 does not use the terms “pre-determined”, “pre-defined” or “fixed”; the only definition given to the terms “a hold position” and “a release position” in Claim 1 is a functional one; and, the Primary Judge correctly construed those two terms. Ronneby supports the reasoning of the Primary Judge as described at [109] to [125] of these reasons. Ronneby also says that the Primary Judge correctly construed para 6 of the Specification as containing a textually composite promise unfulfilled by each claim with the result that all claims fail for reasons of inutility.

91 At this point, it is also convenient to mention another aspect of the specification which goes to the prior art. As already mentioned, the specification says, as an aspect of the invention, that the lock is “swung about an axis” that extends generally longitudinally for easy use and stability and in the hold position the lock “fits within” a cavity in the sidewall of the nose which “avoids the conventional through-hole and provides increased nose strength” [emphasis added]. Moreover, the sides of the lock in such an aspect are said to form a secure and stable locking arrangement without substantial loading of the hinge portion of the lock: PA, para 18. The reference to a “conventional through-hole” is said to be one in which there is a hole through a section of the nose which generally aligns with a through-hole in a wear member once the wear member is fully received by the base. Put simply, conventionally, a lock in the form of a screw apparatus (comprising a housing of one kind or another and a screw or wedge to be wound into the housing) is inserted or hammered into the aligned opening (passing into and occupying the hole through the nose) with the screw part of that apparatus then being rotated such that the lock (housing and screw) firmly secures the wear member to the base.

Torq Lok

92 It is also convenient at this point to note some things about the Torq Lok product produced by Quality Steel and in doing so we refer to the observations of the Primary Judge and the photographs adopted by the Primary Judge. There is no challenge to the finding that the Torq Lok product forms part of the prior art.

93 The Torq Lok product is described as a “locking pin/retainer” arrangement: PJ at [20]. It is a hammerless method of fitting a wear component to an excavator. It initially consisted of a “screw” and a “polymer retainer”: PJ at [20]. It operates in this way. The wear component (which essentially has the same digging role as the wear member) is manufactured with a cavity for locating the polymer retainer (and screw). When the Torq Lok is being assembled in the wear component, the first step is to fit the polymer retainer within the cavity in the wear component. The polymer retainer is “interference fitted” into the cavity: PJ at [20]. The screw is then “securely threaded” into the retainer: PJ at [20]. There is a “very tight fit between them”: PJ at [20].

94 However, the threading of the screw is ideally undertaken such that the end of the screw, when the screw is rotated, does not protrude beyond the “underside” of the polymer retainer (otherwise called the “distal end” of the screw, (PJ at [20]), that is, the point more distant from the head of the screw). However, this preferred practice of not rotating the screw such that the distal end does not protrude beyond the underside of the polymer retainer, proved to be problematic because some screws, during assembly, were rotated too far such that the distal end of the screw did protrude beyond the underside of the polymer retainer making it necessary for operators of excavating equipment to “back the screw off” (which, by then, was “securely threaded” and a “very tight fit”): PJ at [20]. Operators needed to “back the screw off” so as to be able to fit the wear component to the corresponding base attached to an excavator: PJ at [20]. This protrusion problem was solved by the manufacturer developing a “gauge” which the distal end of the screw would contact at a point of alignment with the underside of the polymer retainer: PJ at [20]. The workers assembling the Torq Lok lock and the wear component would then have an indication of when to stop rotating the screw any further: PJ at [20].

95 The wear component with the Torq Lok in position was then shipped to customers. The components of the Torq Lok thus became the pin or screw, the polymer retainer and the gauge although the critical two elements seem to be the pin or screw and the polymer retainer.

The photographs in relation to the Torq Lok product

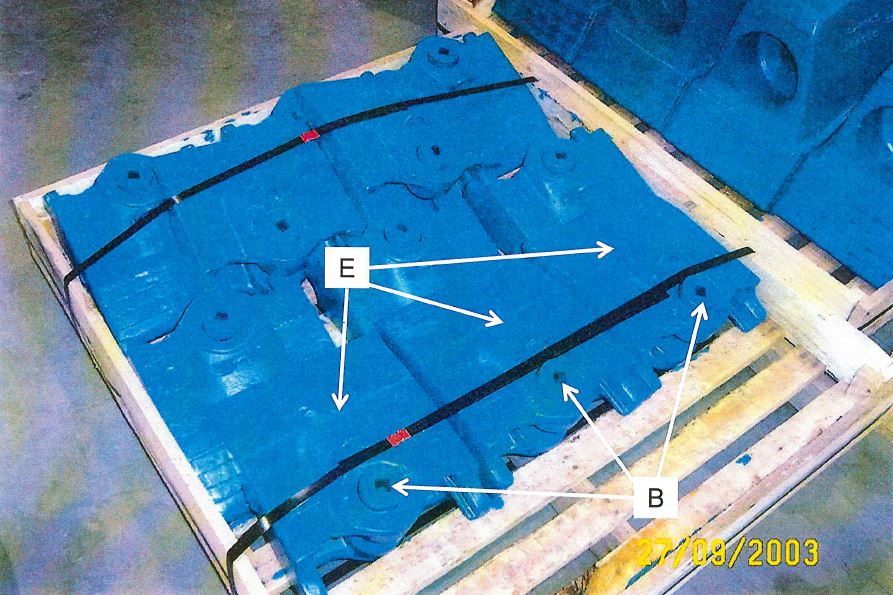

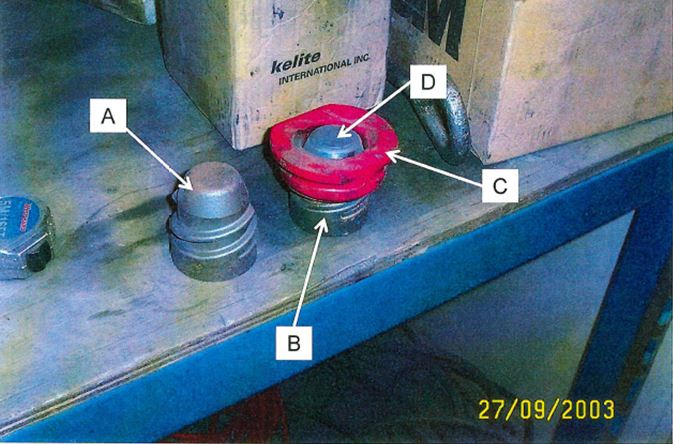

96 The following photograph is set out at [22] of the Primary Judge’s reasons.

97 The photograph at [96] shows (although not very clearly; marked “E”), a number of “wear components” to be attached to a “lip adapter” (T, p 62, lns 1-3) which sits on an excavator bucket. The wear components in this image are strapped to a palette. What can be seen more clearly, marked “B”, is the top of the Torq Lok “locking pin” or screw, with a square depression to enable a screw tool (a ratchet) to be inserted for rotating the screw. In this photograph, the locking pin (or screw) is in the “unlocked position”: PJ at [22]. The notion “unlocked position” is explained by the Primary Judge by reference to two other photographs at [22]. The first is the following photograph:

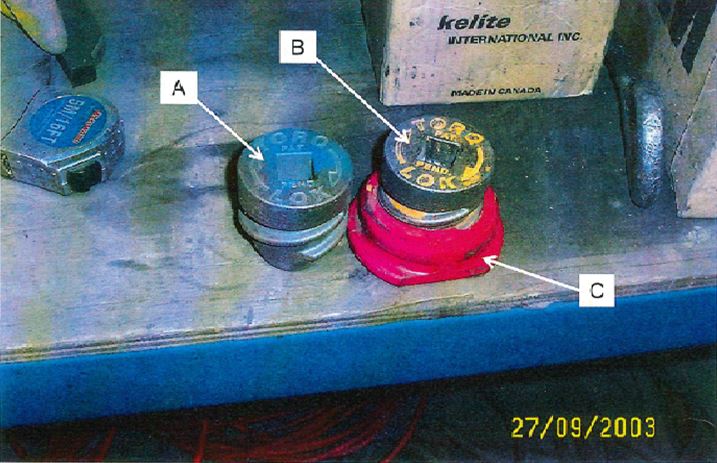

98 This photograph shows the screw or locking pin marked “A”. The thread is clear and the clockwise rotation is shown on the head of the screw. Another example of the Torq Lok screw is shown marked “B” and in this example the screw is shown located threaded, in part, into a red polymer retainer marked “C”. In the example marked “B” and “C”, the screw is depicted with one cycle of the thread showing with the result that the screw is not “fully located” in the polymer retainer.

99 The second photograph relevant to the question of what might be the “unlocked position” is the following photograph:

100 This photograph shows, marked “A”, the same screw or pin component as shown in the photograph at [97] except that the screw is now turned upside down. The image clearly shows the thread and the shape of the distal end of the screw. It also shows the other component from the photograph at [97] also upside down so as to show (marked “B”, “C” and “D”), the screw (marked “B”) threaded into the polymer retainer (marked “C”) from the “underside” in such a way that the distal end of the screw (marked “D”) is “generally flush” with the underside of the polymer retainer: PJ at [22]. This “generally flush alignment” represents the “unlocked position” of the Torq Lok lock. In this position, the wear component could be placed over, or removed from, the lip adapter (or base) attached to the excavator: PJ at [22]. In such a position, the wear component would not be “secured” to the adapter. In the “locked position” the screw “would have been threaded further into the [polymer] retainer” such that the distal end of the screw would be “proud of the [underside] of the retainer”: PJ at [22].

101 Apart from these photographs, the Primary Judge also had regard to four drawings (caused to be made by a witness called by Ronneby, Mr Hughes, a mechanical engineer; PJ at [23]), of a wear component and a Torq Lok locking pin arrangement which Mr Hughes viewed at Quality Steel in 2003 at Nisku, Canada. The four drawings depict the “stages of attachment” of the wear component to the lip adapter or base attached to and the “engagement” of the locking pin: PJ at [23].

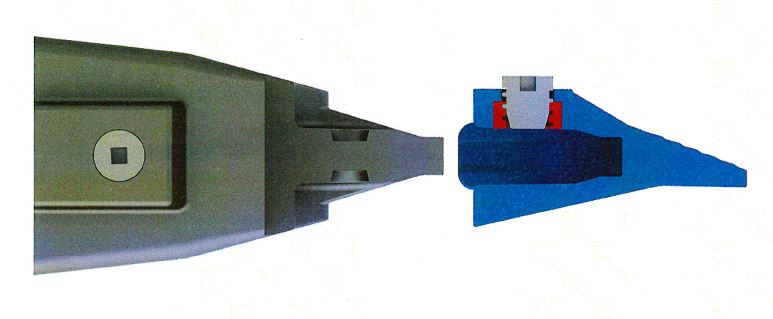

102 The drawings depicted at [23] of the Primary Judge’s reasons (marked 1, 2, 3 and 4) are not as clear as they might be. Clearer examples of the drawings have been provided to us. Drawing 1 is set out below:

103 Drawing 1 shows the lip adapter or base (on the left) about to receive the wear member (on the right). The digging end of the wear member can be seen on the right-hand side of the wear member. The drawing shows a cavity in the wear member and located within it is the polymer retainer and screw. In black and white images, the polymer retainer is not particularly obvious although these reasons contain colour photographs which clearly show the red polymer retainer. The screw, rotated into the retainer, is shown in such a way that the distal end is not protruding beyond the underside of the polymer retainer. A recess (or cavity) in the lip adapter can be seen which will ultimately progressively receive the distal end of the screw once alignment is achieved.

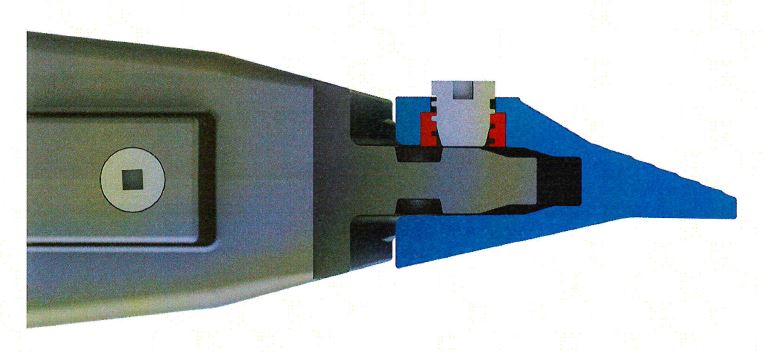

104 Drawing 2 is set out below.

105 Drawing 2 shows a further stage of receipt by the base of the wear member. It also shows the pin or screw seated in the polymer retainer. The distal end of the screw is shown “generally flush” and not “proud of” the underside of the retainer. The cavity in the wear member with retainer and screw is, in this drawing, not yet aligned with the recess in the base. Drawing 3 is set out below.

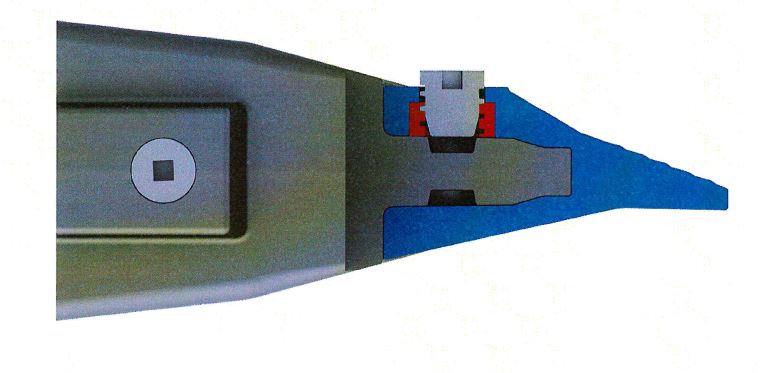

106 Drawing 3 shows the wear member seated on the base with the cavity and screw in the wear member in alignment with the recess in the base. The distal end of the screw remains flush with, and not proud of, the polymer retainer. Drawing 4 is set out below.

107 Drawing 4 shows the screw fully rotated into the polymer retainer such that the top of the screw is flush with the top surface of the wear member and the distal section of the screw is now fully seated in the recess in the base. Consistent with the upside-down photograph of the screw (seen as example marked “A” in the image at [98] of these reasons), Drawing 4 shows the shape of the distal section of the screw and the corresponding profile of the recess which receives the distal section of the screw.

108 In Drawing 3, the screw is in a position described by the Primary Judge on the basis of the evidence of Mr Hughes as the “unlocked position”. In Drawing 4, the relevant section of the distal end of the screw is fully located in the recess in the base. At that point, the wear member is “held in place”: PJ at [20]. The position depicted in Drawing 4 might also be described as a position in which the wear member is “locked” in place.

The findings of the Primary Judge

Novelty

109 At [29], the Primary Judge observed that the “description of the invention in the specification and associated diagrams” were of little assistance to him on the question of construction as they were substantially concerned with aspects of the invention which are “much narrower than those covered by Claim 1”.

110 At [31], the Primary Judge took the view that he was not assisted on the controversy as to the question of construction of Claim 1 by the evidence given by either of the experts. Ronneby called evidence from Mr William Hunter and ESCO called evidence from Mr Howard Robinson. Both men are mechanical engineers “of considerable experience”: PJ at [31].

111 At [31], the Primary Judge notes that Mr Robinson gave evidence that the Torq Lok lock was not an “integral lock” having a “hold position” and a “release position”, “as described in the Opposed Application”, and did not have a “clearly defined hold position and release position for the lock”. The Primary Judge notes that Mr Robinson was not cross-examined on those views and, in an affidavit filed subsequently by Mr Hunter, Mr Hunter made no reference to those views. The Primary Judge took the view, however, that Mr Robinson, in expressing his opinions, appeared to have “assumed a particular construction of Claim 1 rather than [having] given the matter [of construction] any specific consideration”, partly at least because the “qualifier clearly defined”, used by Mr Robinson, did not appear in the language of Claim 1 or otherwise appear in the Specification: PJ at [31].

112 In the result, the Primary Judge considered that “for better or for worse, … the constructional question arising with respect to Claim 1 must be resolved within the four corners of the claim itself, against an understanding, of course, of the relevant field of engineering and the industrial settings in which arrangements of the kind proposed by the inventors would be used” [emphasis added]: PJ at [32].

113 At [33], the Primary Judge said this:

To the extent that the hold position and the release position are given definition in Claim 1, those definitions are functional ones. The hold position is “where the lock can secure the wear member to the base”, and the release position is “where the wear member can be released from the base”. In my view, a lock which could be moved between a position where the wear member would be secured to the base and a position where it could be released from the base would come within these words in Claim 1. So long as those two functional criteria are satisfied, the claim is, in my view, unconcerned with the precise location of the two positions referred to. That is not to say, of course, that an arrangement that operated other than by reference to two positions, such as one that involved the progressive application of force, for example, would come within the claim. The construction I prefer would not airbrush out of the claim the need for the lock to operate in a way which might broadly be described as binary. But it is to say that the predetermination of exact positions, abstracted from the industrial usage of the lock is not, in my view, a requirement of the claim.

[emphasis added]

114 At [33], the Primary Judge finds that the hold position and release position are positions determined by function. Once the lock is in a place “where it can secure the wear member to the base”, the lock of Claim 1 is, “to the extent that the hold position [is] given definition in Claim 1”, in the hold position and once the lock is in a place where the wear member can be released from the base (to the extent any definition can be found in Claim 1), the lock is in the release position. Thus, the Primary Judge concludes that the claim is unconcerned with the precise location of either position. A pre-determined or exact position “abstracted from the industrial usage of the lock” is not a requirement of the claim, as a matter of construction: PJ at [33].

115 The Primary Judge, however, also construes Claim 1 as incorporating a need for the lock to operate in a way which might broadly be described as binary (on/off; 0/1) and concludes that his “preferred construction” ought not be seen as “airbrushing” out of the language of Claim 1, the need for the lock to operate in a broadly binary way: PJ at [33]. The Primary Judge also recognises (and thus accepts, in the sentence at [33] commencing: “That is not to say …”) that the claimed invention of Claim 1 contemplates an arrangement that operates “by reference to two positions”.

116 At [34], the Primary Judge then considered whether the Torq Lok product contained those features. The Primary Judge concluded that the Torq Lok has a “hold position” and a “release position” in the sense contemplated by Claim 1 as construed. The Primary Judge said this at [34] of the Torq Lok product:

Once the wear member was engaged with the base, the lock would be moved to a position where it would “secure the wear member to the base”. When the wear member needed to be replaced, the lock would be moved to a position where “the wear member [could] be released from the base”.

117 As to the notion that the introduction of the “gauge” demonstrated the absence of a singular release position at which the lock could be set before being shipped to a customer, the Primary Judge observed that the introduction of the gauge to fix the particular position for shipment to customers made no difference to the question of construction and that was especially so because Claim 1, in the view of the Primary Judge, “does not require the presence of a precise, pre-determined position as the release one”: PJ at [35]. At [36], the Primary Judge accepted that Claim 1 is concerned not with the position of the lock ex works (for transmission to customers), but with the position to which the lock would be moved for the purposes of releasing the wear member from the corresponding base and so long as there is “such a position”, “it is neither here nor there that the lock might not have been in that position at the point of shipment from the supplier”.

118 For the reasons described at [109] to [113] of these reasons, the Primary Judge concluded that the Torq Lok lock fell within the terms of Claim 1 of the Patent Application and thus anticipated the claim.

119 The Primary Judge also upheld Ronneby’s novelty case in relation to Claims 6, 7, 9 to 15 and 18 to 23 of the Patent Application.

120 At [49], [50] and [51], the Primary Judge held that Claims 6, 7 and 9 involve no material differences from Claim 1 and thus all three claims lack novelty for the same reasons given in relation to Claim 1.

121 At [52], the Primary Judge held that Claims 10, 11 and 12 depend, directly or indirectly, on Claim 9 and since those claims do not introduce any integer of relevant material difference from those contained in Claim 1, each of these three claims lack novelty for the same reasons given in relation to Claim 1.

122 Claim 13 was found to have been anticipated by the Torq Lok product for the same reasons given in relation to Claim 1: PJ at [53].

123 The Primary Judge held that since Claims 14, 15 and 18 depend, directly or indirectly, on Claim 13 and do not otherwise introduce any integer of relevant material difference, those claims lack novelty for the same reasons given in relation to Claim 1: PJ at [54].

124 At [55], the Primary Judge held that Claim 19 is relevantly indistinguishable from Claim 1 except in one relatively minor respect. The Primary Judge observed that Claim 1 describes the “release position” as one in which the wear member can be released from the base whereas Claim 19 describes the release position as one in which “the lock permits installation and removal of the wearable body on and from the base” [emphasis added]. As to Claim 19, the Primary Judge said this:

However, taking the view, as I do, that the existence of a pre-determined, precise, position either hold or release, is not a requirement of Claim 1, and likewise taking the view that Claim 19 should be similarly understood, I would also hold that the Torq Lok fell within the terms of the latter because the pin was, as observed by Mr Hughes and as inferentially supplied to customers, in the position in which the wear member would be installed on the base, being the same position as the pin would occupy when the wear member was subsequently released from the base. Thus the applicant’s novelty case in relation to Claim 19 should also be upheld.

125 At [56], the Primary Judge found that since Claims 20, 21, 22 and 23 depend, directly or indirectly, on Claim 19 and do not otherwise introduce any integer of relevant material difference from those in Claim 1, Claims 20, 21, 22 and 23 lack novelty as being anticipated by the Torq Lok lock.

Utility

126 At [66], the Primary Judge notes Ronneby’s contention that the advantages promised by the authors of the Patent Application are those set out at paras 5 and 6 of the Specification (see [21] and [24] of these reasons), namely, “enhanced stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement”. The Primary Judge also notes that fundamental to Ronneby’s contention about lack of utility was the proposition that these advantages are expressed “cumulatively” such that the relevant promise is that all of these advantages will be delivered by the invention “so far as claimed in every claim” [original emphasis].

127 At [67], the Primary Judge addresses aspects of the evidence and notes that the experts, Mr Hunter for Ronneby and Mr Robinson for ESCO, were asked this question:

What is meant by the following statements in paragraphs 5 and 6 of the Patent Application?

5. Many designs have been developed in an effort to enhance the strength, stability, durability, penetration, safety, and/or ease of replacement of such wear members with varying degrees of success.

...

6. The present invention pertains to an improved wear assembly for securing wear members to excavating equipment for enhanced stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety, and ease of replacement.

128 At [68], the Primary Judge notes that Mr Hunter gave the following answer:

Hence, in relation to the first paragraph above, this means that in the past the patentee acknowledges that wear members have been developed with different designs in an attempt to improve them in the following ways:

1. Enhanced strength. This would mean that it could be expected that in operation the wear member would be less likely to fail or break as a result of the loads or stresses to which it was subjected during excavation than would otherwise be the case.

2. Enhanced stability. This would mean that it could be expected that in operation the wear member would be more resistant to being displaced by the loads to which it was subjected during excavation than would otherwise be the case.

3. Enhanced durability. This would mean that it could be expected that in operation the wear member would have a longer life, and would wear less rapidly during excavation than would otherwise be the case.

4. Enhanced penetration. This would mean that it could be expected that in operation the wear member would more easily penetrate the ground during excavation than would otherwise be the case. It would also be expected that as a result of better penetration into the ground, the flow of earthen materials into the bucket during excavation would be improved.

5. Enhanced safety. This would mean that when installing or removing the wear member, it would be more safe to install or remove the wear member to or from the base with less risk of injury to the installer. It would also be expected that the lock would hold the wear member to the base more securely than would otherwise be the case. The experts agree that a wear member that becomes loose and is dislodged from the base during excavation poses an additional safety risk.

6. Enhanced ease of replacement. This would mean that it would be easier to remove a wear member from the base, and to fit a wear member to the base than would otherwise be the case.

In relation to the second paragraph above, this means that the invention is also seeking to improve the six (6) parameters of strength, stability, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement via an improved wear assembly, that is via improvements to the wear member, the base, and the lock.

[emphasis added]

129 At [68], the Primary Judge also notes that Mr Robinson agreed with the above observations of Mr Hunter.

130 At [69], the Primary Judge notes that the experts were also asked this question:

What are the advantages that, collectively, the aspects of the invention described in the Patent Application are said to achieve?

[emphasis added]

131 At [69], the Primary Judge notes that Mr Hunter summarised the “aspects” of the invention at paras 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 14 of the Specification, the preferred embodiment at para 13 of the Specification and the “aspects” of the invention described at paras 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20 of the Specification. Mr Hunter then sought to answer the question at [127] above by reference to the para 6 “advantages” of enhanced stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement. As to the aspects at paras 7 to 14 of the Specification, the Primary Judge notes that Mr Hunter explained that those aspects relate to the geometry of the nose and the wear member and were said to have “benefits” related to “strength, stability, penetration and durability”: that is, four of the six matters recited at para 6 of the Specification. However, Mr Hunter gave evidence that those benefits would only be achieved when the wear member is “fitted” and the “assembled wear member is being used for excavation”: PJ at [69]. The Primary Judge also notes Mr Hunter’s evidence that the six aspects set out in para 6 of the Specification “related to the inclusion of a lock integrally secured to the wear member [and were] said to have benefits of ease of replacement and safety”. The Primary Judge also notes Mr Hunter’s evidence that those benefits “would appear to be achieved either prior to the wear member being fitted (for example, when stored in inventory), or during installation of the wear member”. Having noted those matters, the Primary Judge notes Mr Hunter’s conclusion that: “All of the aspects of the invention would need to be combined together … to allow all of the advantages of the invention described in paragraph [6] of the Patent Application to be obtained” [emphasis added].

132 At [69], the Primary Judge also notes that Mr Robinson agreed with Mr Hunter’s answer described at [131] of these reasons to the question set out at [130] of these reasons.

133 At [70], the Primary Judge notes that the experts were also asked this question:

For each claim of the Patent Application:

a) what advantage(s) does the Patent Application identify for the features of the wear member or wear assembly in that claim?

b) for any other advantages identified in question 2, would a wear member or wear assembly having the features in that claim necessarily achieve that advantage? Why or why not?

134 At [70], the Primary Judge notes that, in answer to that question, Mr Hunter devised a detailed table setting out the “features” of each claim identifying the “advantages” achieved by the respective features. Mr Hunter’s summary seeks to take each of the para 6 “advantages” and identify whether each claim achieves the particular advantage. As to that, the Primary Judge notes at [70] Mr Hunter’s summary as set out in a table in these terms:

In relation to enhanced strength, none of the claims would achieve this advantage.

In relation to enhanced stability, claims 3 and 5 may provide a minor stability advantage as set out in paragraphs 14-21 of my first affidavit. [sic - this was clearly an intended reference to Mr Hunter’s second affidavit sworn on 21 October 2015]

In relation to enhanced durability, none of the claims would achieve this advantage.

In relation to enhanced penetration, none of the claims would achieve this advantage.

In relation to enhanced safety, claims 1, 11, 13, 21, and 22 would achieve this advantage.

In relation to enhanced ease of replacement, claims 1, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, 19, 22, and 25 would achieve this advantage.

135 As to this evidence, the Primary Judge said that two further things should be noted. The first was that in accordance with the authorities, a “minor advantage” ought to be held to be enough for ESCO to succeed on a question of utility in an appeal under s 60(4). The second was that as to claims not mentioned in Mr Hunter’s summary at all, his Honour said at [71]:

Claim 2 is dependent on Claim 1, Claim 7 is dependent on Claim 6, Claim 10 is dependent on Claim 9, Claims 14, 15, 17 and 18 are, directly or indirectly, dependent on Claim 13, Claims 20, 23 and 24 are dependent on Claim 19 and Claim 26 is dependent on Claim 25.

136 The Primary Judge observes at [71] that in each case the independent claim would achieve an advantage by way of enhanced ease of replacement (and, in the case of Claim 13, also by way of enhanced safety). At [71], the Primary Judge also said this:

Since each dependent claim will, by its terms, contain all the integers of the relevant independent claim, I am in no position to conclude – and the experts’ report does not clearly state – that those dependent claims do not likewise achieve that advantage (or, in the case of Claims 14, 15, 17 and 18, advantages [of enhanced ease of replacement and enhanced safety]).

[emphasis added]