FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd v Intellectual Property Development Corporation Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 29

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 MARCH 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed with costs.

2. The Notice of Contention be dismissed.

3. The application for leave to appeal be dismissed with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 The appellants, Fermentum Pty Ltd (formerly known as Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd) and Stone & Wood Brewing Pty Ltd (Stone & Wood), are brewers of craft beer based in the Byron Bay and Murwillumbah regions of New South Wales. They sell a number of different craft beers, including a beer called “Pacific Ale” which has been sold under that name since 2010. It is Stone & Wood’s best-selling product. The respondents (Elixir) are also brewers of craft beer, based in Brunswick in Melbourne, Victoria. Elixir sells beer under a number of different brands, including one called “Thunder Road”. In 2015, Elixir launched a beer called “Thunder Road Pacific Ale” (which, following letters of demand from Stone & Wood, was renamed “Thunder Road Pacific” in 2015). It is these products which form the basis of these proceedings.

2 In 2015, Stone & Wood commenced proceedings in this Court against Elixir alleging passing off, misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law and false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law. It subsequently amended its initial pleading to bring a claim for infringement of its registered trade mark for “Stone & Wood Pacific Ale” under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The Elixir parties cross-claimed alleging that Stone & Wood had made groundless threats to bring an action for trade mark infringement under s 129 of the Trade Marks Act, and had not pursued their infringement claim with due diligence.

3 After a four day hearing in April 2016, on 21 July 2016 the primary judge rejected Stone & Wood’s claims for misleading or deceptive conduct, false or misleading representations and for passing off. He also rejected Stone & Wood’s trade mark claim. Further, he concluded that Elixir’s cross-claim was established and rejected Stone & Wood’s asserted defence under s 129(5) of the Trade Marks Act that it had brought an infringement claim with due diligence. See Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd v Intellectual Property Development Corporation Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 820; 120 IPR 478. On 5 August 2016, the primary judge made a declaration that Stone & Wood had made groundless threats to bring a claim for trade mark infringement: see Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd v Intellectual Property Development Corporation Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 896.

4 Stone & Wood has appealed against the orders dismissing its claims for passing off and under the Australian Consumer Law. It also seeks leave to appeal against the primary judge’s conclusion that it made groundless threats to bring an action for trade mark infringement. The respondents, for their part, have filed a Notice of Contention seeking to support the conclusions of the primary judge on grounds other than those relied on by his Honour. The appeal in respect of the passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct was limited to only some of the claims made below.

The products

5 The Stone & Wood and Thunder Road products that form the basis of this litigation were conveniently described by the primary judge in his reasons at [1]-[6] as follows:

1 … Stone & Wood launched its first beer in 2008 – it was known as ‘Draught Ale’. In November 2010, the Draught Ale was re-named ‘Pacific Ale’ (Stone & Wood Pacific Ale). Stone & Wood decided to change the name when it started to sell this beer in bottles – it seemed odd for a beer named ‘draught’ to be available in bottles. Stone & Wood chose the name ‘Pacific Ale’ for two reasons. First, it reflects the place where the beer is brewed and the story behind the brewery. Secondly, the word ‘Pacific’ generates (in the words of one of the directors) a “calming, cooling emotional response”. Over time, the range of beers brewed and sold by Stone & Wood has increased. The four main beer products now produced by Stone & Wood are Pacific Ale, Green Coast, Jasper Ale and Garden Ale. Since the brewery was established in 2008, sales of Stone & Wood beers have steadily increased. Stone & Wood sells its products mostly across the eastern seaboard of Australia, in particular in the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales, South East Queensland, Sydney and Melbourne. The Pacific Ale beer is Stone & Wood’s best-selling product, accounting for approximately 80-85% of Stone & Wood’s beer sales.

2 … Elixir distributes and sells beer under a number of brands, including ‘Thunder Road’. The Thunder Road logo is used in conjunction with a stylised image of Thor, the Norse god of thunder, a shield and, sometimes, the slogan, ‘Beer Without Borders’. Elixir produces a number of different beer products under the Thunder Road brand, including Pilsner, Golden, Pale Ale and Amber. In about January 2015, Elixir launched a beer named ‘Pacific Ale’ under the Thunder Road brand (Thunder Road Pacific Ale). Later, following letters of demand from Stone & Wood, this beer was re-named ‘Pacific’ (Thunder Road Pacific). Elixir sells its Thunder Road beer products in both ‘on premise’ and ‘off premise’ channels in Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia and Tasmania. The ‘on premise’ channels consist of hotels, restaurants, cafes and bars, where the product is sold both in kegs and in packaged (bottle) format. The ‘off premise’ channels include bottle shops. Through this channel, the Thunder Road beers are sold in bottles.

3 Both Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale may be described as ‘craft beers’. The craft beer market is difficult to define. Craft beer has come to be regarded by the market as beer which is outside of the traditional mainstream beer category, which comprises primarily pale lagers made by large multinational brewing businesses; the term ‘craft’ tends to describe beers (and brewers) that put greater emphasis on the flavours of a beer’s ingredients and that are made using less industrialised brewing processes.

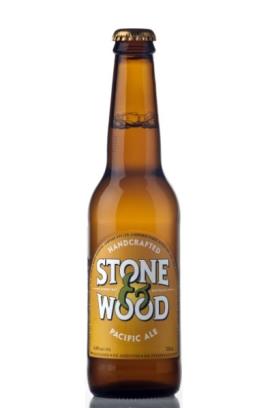

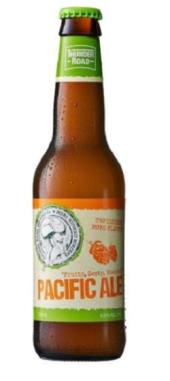

4 Images of the 330 ml bottles of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale are set out below. (The bottle for Thunder Road Pacific, set out later in these reasons, was similar to the Thunder Road Pacific Ale bottle.)

|

|

5 Images of the six-packs for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale are set out below:

|

|

6 Images of the beer tap ‘decals’ (affixed to the taps in licensed venues selling draught beer) for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific are set out below:

|

|

6 Stone & Wood’s registered trade mark, which formed the basis of its trade mark infringement claim, was as follows:

The claims in the proceeding

7 The claims brought by Stone & Wood alleged misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law and an action for passing off, along with a claim for infringement of its registered trade mark for Stone & Wood Pacific Ale under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The trade mark claim is not pursued on appeal. The pleading of the claims was described in detail by the primary judge at [15]-[40] of his reasons. There were two ways in which Stone & Wood asserted that its passing off and Australian Consumer Law claims were made out. Stone & Wood argued that the respondents’ use of the names “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” would lead consumers to order or buy the Thunder Road beer when they intended to order or buy Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. Secondly, it was submitted that Elixir’s use of the names “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” represented to consumers that the Thunder Road beer was promoted, distributed and/or sold with the licence or authority of the appellants, that its beer had the sponsorship or approval of the appellants and that the respondents had the sponsorship or approval of or an affiliation with the appellants. As there was no connection between the two groups of parties or their Pacific Ale or Pacific beer, it was submitted that this constituted an actionable misrepresentation which would cause damage to Stone & Wood’s reputation and goodwill.

8 This second way of putting the passing off and Australian Consumer Law cases was reformulated on appeal (without change of substance) into a more elegant formulation of “association” or “connection”. That is that Elixir falsely represented that there was an association or connection between Thunder Road’s Pacific Ale/Pacific beer and Stone & Wood’s Pacific Ale beer, or between Thunder Road’s Pacific Ale/Pacific beer and Stone & Wood, or between Thunder Road and Stone & Wood.

9 There was no challenge on appeal to the dismissal of the trade mark claim; nor was there a challenge to the dismissal of the passing off or Australian Consumer Law claims in so far as they were based on the first way they were put – that the conduct of Elixir involved or represented that the Thunder Road beer was Stone & Wood’s beer.

10 For the reasons set out below, the appeal should be dismissed with costs, and the application for leave to appeal in relation to the orders under s 129 of the Trade Marks Act should be dismissed with costs.

Evidence at trial

11 There was a four day trial on liability before the primary judge. Stone & Wood adduced evidence from seven witnesses: Mr Cook (a director of Stone & Wood) who gave evidence about the business and the history, marketing and sale of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale; Mr Kirkegaard (a freelance beer writer, commentator, educator and consultant focused on the craft beer market) who gave expert evidence about the craft beer market in Australia, beer styles and the significance of the name “Pacific Ale” in the craft beer market; Professor Lockshin (a Professor of Wine Marketing) who gave expert evidence relating to marketing and consumer behaviour; Mr Coorey (managing director of the Boardwalk Tavern on Hope Island on the Gold Coast, Queensland); Mr Crooks (managing director of The Grain Store Craft Beer Café in Newcastle, New South Wales); Ms McGrath (a director of the Palace Hotel in South Melbourne); and Mr Omond (solicitor for Stone & Wood), who gave evidence about some instances of the promotion of Thunder Road Pacific Ale in several venues and liquor stores and was not cross-examined.

12 The respondents adduced evidence from a further eight witnesses: Mr Withers (the managing director of the respondents); Mr Camilleri (senior vice-president of the ICB Group, which includes the respondents, and general manager of marketing for Elixir); Mr Jane (the managing director of Disegno, a creative brand development agency) who gave expert evidence in relation to brand design; Mr Piperno (owner of two liquor stores specialising in craft beer and specialty wine in Brunswick and Carlton North (suburbs of Melbourne)); Mr Curran (an owner of the Sunshine Coast Brewery in Kunda Park, Queensland); Mr Eleftheriadis (freelance web developer and brand designer) who was not cross-examined; Mr Morton (a graphic designer) who was not cross-examined; and Mr Cleaver (national sales manager for Thunder Road beer, employed by Elixir) who was not cross-examined.

13 From this evidence, the primary judge in careful and comprehensive reasons made a number of factual findings. His Honour’s detailed summary of the evidence before him and findings drawn from it can be seen at [47]-[172] of his reasons. Few of the findings made by the primary judge were attacked. The fundamental complaint was that his Honour failed to give proper weight and significance to the findings that he did make.

Findings made by the primary judge

Brewing of Stone & Wood and Thunder Road

14 Stone & Wood brewed its first beer for sale in 2008. It was called “Draught Ale”. It was re-named as “Pacific Ale” in November 2010. In 2009, Stone & Wood launched a second beer, which came to be known, by June 2015, as “Green Coast”. Stone & Wood now produces four different beers: Pacific Ale, Green Coast, Jasper Ale and Garden Ale. Sales of Stone & Wood have grown substantially since 2008, with its distribution expanding from the Northern Rivers of New South Wales and South East Queensland to Melbourne and Sydney in 2009 and to national sales in various liquor outlets from 2010. The products are mostly sold on the east coast of Australia, and Stone & Wood also has a significant online and social media presence.

15 Elixir commenced brewing operations in 2010. The primary judge found that “Thunder Road Brewing Company” was chosen as a brand name in-house, along with the “Thor symbol” that is its logo. The products are sold both “on premise” in kegs and packaged format and “off premise” in packaged format. Its bottled beer has been sold since 2014 or 2015. The bottled beer is brewed in Belgium in the absence of Elixir having a bottling facility in Melbourne.

The craft beer market and the consumers in it

16 At [58]-[66] of his reasons, the primary judge made findings about the so-called craft beer market. These are important findings, because they frame and illuminate the consumers of beer in the relevant market in respect of whom the character and quality of any representations said to have been made by Elixir are to be assessed.

17 The primary judge’s findings were founded on the evidence of Mr Kirkegaard (called by Stone & Wood). The primary judge recognised the difficulty of definition of the market. The primary judge accepted Mr Kirkegaard’s evidence that the craft beer market was outside the traditional mainstream beer market. It was a market in which greater emphasis is placed than in the traditional market on flavour and where beers are brewed using less industrialised processes, often by smaller independent brewers (now in the hundreds in Australia). The market can be traced to the late 1990s from when, especially in the last few years (prior to 2016), it has grown strongly. Craft beer is a premium product. Importantly, Mr Kirkegaard identified “two broad groups” of consumers who had driven the sudden growth of the craft beer market in recent years. These groups were described by the primary judge in [62] of his reasons as follows:

(a) The first comprises younger consumers looking to drink something different from the generic lagers. These consumers are often well informed about the products and could be described as ‘involved’ consumers.

(b) The second is a more general group of beer consumers. In Mr Kirkegaard’s experience, these consumers are looking for a premium (perhaps ‘boutique’) experience, but have less interest in, or understanding of, the issues relating to craft beer. These consumers are less likely to research brewery ownership and brewing practices and more likely to rely on a brewery’s marketing and brand image to form their view of whether a beer is ‘craft’ or satisfies their “non-flavour demands”. This part of the consumer base for craft beers has grown considerably as craft beers have become more widely available alongside mainstream beers.

18 The primary judge also accepted Mr Kirkegaard’s evidence in cross-examination about the first and second groups of consumers. He said that the first group of consumers were interested in the brewer of the beer, saying that they were “very much in tune with … what’s called the Brewery story”. The second could be swayed by what was on the bottle. Mr Kirkegaard believed (and the primary judge found) that this second group would look at the bottle and packaging carefully. They were looking for a premium experience and were “engaged in a thought process of trying to select a premium product”.

19 Supplemented by the further findings to which we will refer shortly, these findings are important because, as the photographs at [5] above demonstrate, and as the primary judge found, the get-up and packaging of the two products are very different. It was not part of the case of Stone & Wood that there was confusion or misrepresentation by reason of the get-up of Elixir’s beer. Rather it was the use of the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” that lead to the asserted misrepresentations. The importance of the findings to which we have just referred lies in the interest and likely attention of the relevant consumers to the beer, its brewer, the packaging and the bottle (to the extent that the beer is sold in bottles).

20 At [63] and [64] of his reasons, the primary judge described Mr Kirkegaard’s evidence of a less precise kind (which the primary judge accepted) as to the interests and discrimination of the consumers:

63 In his first affidavit, Mr Kirkegaard said that, in his experience, many consumers of craft beer are not only motivated by how the beer tastes; they are interested in what a brand promises in terms of independence, local production, small batch production and other ancillary aspects of the brand. In this context, ancillary aspects of the brand are marketing features that target personal preferences, but do not relate to how the beer actually tastes. In craft beer, many consumers are drawn to the independence of small breweries (and the stories behind them), being small local companies, or their ‘anti-establishment’ attitudes. During cross-examination, Mr Kirkegaard accepted that Stone & Wood communicates a brand promise, which was “[v]ery much from the northern rivers of New South Wales, very laidback lifestyle, very plugged into the community”.

64 Mr Kirkegaard said during cross-examination that, while it is very hard to pigeonhole craft beer consumers, they tend to be willing to spend more than the mainstream beer consumer. He also said that:

… particularly in the craft beer sphere, people tend to be very experimental and they will – if they like a particular class or style or flavour profile of beer, the brand isn’t necessarily what they’re buying for. They’re buying to experience others in that style.

Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and its reputation

21 At [82], the primary judge made findings based on the evidence discussed at [67]-[81]. He accepted that Stone & Wood Pacific Ale was “cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and refreshing finish” and was brewed using Australian wheat, barley and Galaxy hops. His Honour accepted the evidence of Mr Cook and Mr Kirkegaard that “when it was launched … Stone & Wood Pacific Ale had a distinctive character”. Furthermore, he accepted that the word “Pacific” in the name was chosen due to the location of Stone & Wood’s brewery in Northern New South Wales and its capacity to generate a “calming, cooling emotional response”. The primary judge went on to find that the dominant feature of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale bottle was the Stone & Wood logo, with the name “Pacific Ale” occupying “a subsidiary position”. This was also the case on the six-pack packaging and the decal for the beer taps from which the beer was poured at licensed premises. The dominant colour on the bottles, six-pack packaging and beer taps was the background colour which was “aptly described as a mustard colour (which may be considered to be a type of orange)”. The primary judge noted that the format of the bottle was the same as for the other main beers in the Stone & Wood range, and that in each case the dominant feature was the Stone & Wood branding, with the name of the product in smaller print underneath the logo. The appearance of the different beers across the Stone & Wood range can be seen below:

22 The above are important findings. Crucial to the resolution of the dispute is the reputation or lack of reputation of Stone & Wood in the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” shorn of direct or clear contextual relation with Stone & Wood. The primary judge dealt with this specifically later in the reasons; but at this point it is worth noting that Elixir emphasises the descriptive quality even in an evocative sense of the words. Elixir emphasises the first of the reasons that Mr Cook identified as a reason that the name was adopted: to indicate where the brewery is, in Byron Bay which is situated on the Pacific Ocean. This was said to be important as part of the story of the brewery. Mr Kirkegaard agreed that the name was evocative of Byron Bay near the beach. At [74] of the reasons, the primary judge noted that Mr Kirkegaard accepted that “Pacific” was an apt descriptor for where the brewery is located.

23 The primary judge was aware of the importance of this. At [72] of the reasons, he set out a long extract from Stone & Wood’s own website dealing with the change of name from Draught Ale to Pacific Ale in 2010. This included the following:

…

On another angle, ever since we launched our ale, people have continually been asking us, “what style of beer is it?”

…

Our ale deserves a name that speaks to where it is created, its home, a name that helps it establish its own place and its own beer style. The answer has been staring us in the face all along. It’s now called Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

Inspired by our home on the edge of the Pacific Ocean and brewed using all Australian barley, wheat and Galaxy hops, Pacific Ale is cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and a refreshing finish.

So when someone asks us “what style of beer is it?”, we will simply say it’s a Pacific Ale.

24 The notion of a “style” of beer, adverted to here on the website, is also important to the notion that there is a descriptive quality, albeit imprecise and evocative, to the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific”. The primary judge dealt with this question later in his reasons at [135]-[142] (see [43]-[44] below).

25 The sales of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale have been substantial: in the 2014/2015 financial year over 45,000 kegs, 200,000 two dozen cartons of 330ml bottles and 22,000 cartons of one dozen 500ml bottles. Bottle sales and draught sales are about equal; and together sales of Pacific Ale make up 80-85% of Stone & Wood’s beer sales.

26 After considering the evidence as to marketing around Australia, but particularly in the Byron Bay area, the primary judge concluded at [91]:

On the basis of the evidence referred to in paragraphs [80], [83]-[85] and [86]-[90] above, I find that the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale has, and had (in January 2015), a substantial reputation in the craft beer market. In relation to Stone & Wood’s marketing activities, on the basis of the evidence referred to in paragraphs [86]-[90] above, I find that Stone & Wood undertakes marketing activities for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale in Australia generally; that the ‘Stone & Wood’ brand name is a significant focus of these activities; and that the words ‘Pacific Ale’ appear in conjunction with ‘Stone & Wood’ (rather than on their own) in almost all cases.

27 These findings and the relationship between them were central to the arguments on appeal. Stone & Wood emphasised the finding of a “substantial reputation in the craft beer market” of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. Elixir emphasised that the marketing was almost always “Stone & Wood” and “Pacific Ale” together in the same context with “Stone & Wood” the focus.

The launch of Thunder Road Pacific Ale, the intentions of those involved, the packaging and sales of Thunder Road Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific

28 At [92]-[114] of the reasons, the primary judge discussed and made findings about the launch of Thunder Road Pacific Ale, the nature of the beer, its labelling and packaging, and the knowledge and intentions of Mr Camilleri and Mr Withers in these regards. The last subject was of importance in that the submissions of Stone & Wood relied heavily on the well-known passage in the reasons of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd [1937] HCA 51; 58 CLR 641 at 657:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive. Moreover, he can blame no one but himself, even if the conclusion be mistaken that his trade mark or the get-up of his goods will confuse and mislead the public. …

29 The “rule” is not a legal presumption, but part of the factual assessment of deception: Australian Woollen Mills 58 CLR at 658; Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157; 234 FCR 549 at 585 [117]; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH [2001] FCA 1874; 190 ALR 185 at 195-196 [45]-[47], 207 [96]; and Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovický, Národní Podnik [2002] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182 at 224 [171]-[172].

30 The bottled format was launched in January 2015 (as Pacific Ale) and the keg format in May 2015 (as Pacific). By May, solicitors for Stone & Wood had written to Elixir complaining of the use of Pacific Ale. Elixir made a decision to change the name of its product to “Pacific”. No kegs were sold under “Pacific Ale”. The labels and packaging for bottles was changed in September and October 2015.

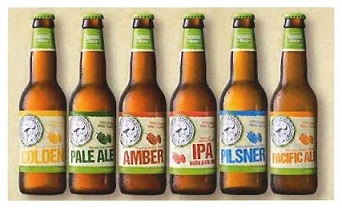

31 Thunder Road Pacific Ale was part of a series of double fermentation beers: Golden, Pale Ale, Amber, IPA, Pilsner and Pacific Ale, the bottles for which were as follows:

32 The Thunder Road Pacific Ale is made from Australian Galaxy hops (as is Stone & Wood’s Pacific Ale). The taste and flavour of the beer was described by Mr Withers and Mr Piperno as summarised at [95] and [96] of the reasons (these descriptions were accepted by the primary judge):

95 Mr Withers said in his first affidavit that the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific is a light bodied beer made from Australian Galaxy hops and is characterised by a distinct hop aroma, with pineapple, passionfruit and citrus notes.

96 Mr Piperno (who, as noted above, owned two liquor stores which specialised in craft beer and specialty wines) gave evidence during cross-examination about the characteristics of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale. He said that “this whole new craft beer segment, … whether it’s a Golden Ale, Bright Ale or Summer Ale, Pacific Ale, they tend to have the same characteristics like … jam-packed full of passionfruit, tropical flavours, melon, grapefruit. … It’s really, really hard to distinguish one from another, from my perspective”. He said that the “taste profile” of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale were probably identical. He said that, insofar as the taste and aroma are concerned, they are “[p]retty much the same”.

33 At [97]-[113] of his reasons, the primary judge carefully discussed the evidence as to the launch of Thunder Road and Pacific Ale, the intentions of Mr Withers and Mr Camilleri, and the design of the labelling and packaging of the beer. At [114] of the reasons he made the following findings:

(1) His Honour accepted Mr Withers’ and Mr Piperno’s evidence as to the descriptions of the Thunder Road and Stone & Wood Pacific Ales: [114(a)].

(2) At the time Thunder Road Pacific Ale was launched, the only beer named “Pacific Ale” being sold in Australia was the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale: [114(b)]. This finding is to be understood as made in the context of the discussion by the primary judge at [122]-[134] of other beers using “Pacific Ale” or “Pacific”. Most were produced and sold after Stone & Wood renamed Draught Ale to Pacific Ale. One was released before that, in 2009, called “Pacific Pale Ale”. Only a small commercial batch was produced (14 kegs) by Sunshine Coast Brewery and the primary judge concluded at [122] that given the small and once-only production it could be set aside. Elixir, without challenging this finding, did submit that the view of Mr Curran of the brewer was relevant that the name “Pacific Pale Ale” was chosen to convey the Australian regional aspect of the beer.

(3) At [114(c)] the primary judge made the following findings about Mr Withers’ intentions. Mr Paige was at that time the head brewer for Elixir:

I accept that Mr Withers was keen to ensure that using the name ‘Pacific’ was not going to cause confusion with the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale; that he asked Mr Paige to confirm that it was acceptable to use ‘Pacific Ale’ as a descriptor of a style of beer; and that Mr Paige responded with the email described above to the effect that one of the founders of Stone & Wood admitted that Pacific Ale is a style.

The email referred to was described at [97] of the reasons:

… Mr Paige sent an email to Mr Withers on 26 August 2014 which stated in its subject header, “Pacific ale = style” and stated in the body of the email (below a link) that, “One of the founders admitting Pacific Ale is a style”; Mr Withers understood the reference to “one of the founders” to mean one of the founders of Stone & Wood; the link was to an article by Mr Kirkegaard in “Australian Brews News” dated 3 December 2010. (The article is described in paragraph [73] above.)

The article described in [73] of the reasons contained the quotation from Mr Cook that included the excerpt from the website set out at [23] above.

(4) At [114(d)] the primary judge made the following findings that are emphasised by Stone & Wood as one of the foundations of their arguments on appeal that the use of Pacific Ale and Pacific by Elixir necessarily conveys a relevant representation of connection or association:

At the time Thunder Road Pacific Ale was launched, Elixir was aware that Stone & Wood were producing a beer named ‘Pacific Ale’; knew that there were a lot of consumers who, when they saw the name Stone & Wood, would think of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale; knew that the name ‘Pacific Ale’ had come to be very closely associated with Stone & Wood in Australia; and knew that Stone & Wood Pacific Ale had a good reputation in the craft beer market.

(5) At [114](e), (f) and (g)] the primary judge made important findings about the labelling and packaging which can be summarised as follows. He concluded that the labelling and packaging of Thunder Road Pacific Ale was “very different” to that for Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The dominant feature on the Stone & Wood product was the Stone & Wood logo, whereas the dominant feature on the Thunder Road product was the name “Pacific Ale”. (In ground 1 of the Notice of Contention Elixir challenges this finding (together with similar findings at [119(b)], [202] and [204]) and asserts that the primary judge should have given more emphasis to “Thunder Road”.) The primary judge also found the dominant colours of the two products to be different. The dominant colour on the Stone & Wood product was mustard, whereas on the Thunder Road product the dominant colours were bright green and bright orange in roughly equal proportions. The green used on the Stone & Wood product was a darker colour and played a more minor role. Similarly, the orange on the Thunder Road product was a brighter orange and the shape of the label was different. The caps were also different colours, and the Stone & Wood product did not have the Thor symbol with which the Thunder Road product was illustrated. He found that “the overall ‘look and feel’ of the two products is very different”, and reached the same conclusion regarding the packaging for the six packs of the two products. In designing the labelling and packaging for Thunder Road Pacific Ale, Elixir did not seek to emulate the labelling and packaging of the Stone & Wood product. The design followed that of their other beers in that range, except for the colour orange which was chosen “to reflect the character or flavour of the product”. His Honour found that it was not established that the colour was chosen in order to emulate the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale background colour or to create an association in consumers’ minds with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. He noted that it was a different colour, and found that it was chosen “to communicate a ‘refreshing, fruity’ flavour”.

(6) The primary judge, however, at [114(h)] found that, in choosing the name “Pacific Ale”, Elixir was to some extent seeking to take advantage of the success of the product of that name in the Stone & Wood range, given its awareness of the product and its good reputation in the market. The primary judge found that this could also be inferred from the fact that the character of the two beers was similar. He rejected the evidence of Mr Withers and Mr Camilleri that they were not seeking to obtain any such advantage, though he accepted that it was not established that Elixir intended to obtain such advantage through consumers thinking that the Thunder Road product was Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or that there was some association between the Thunder Road product and Stone & Wood or its product. Based on the different labelling and packaging, the primary judge concluded that Elixir did not intend to obtain an advantage by consumers thinking that the Thunder Road product was Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or that there was an association between Thunder Road and Stone & Wood or its product.

34 These findings that Elixir did not intend to take any advantage by causing any misrepresentation as to the beer or its association and that it intended to distinguish the two products to avoid any confusion by packaging, labelling and get-up were based on credit. Both Mr Withers and Mr Camilleri were cross-examined on their credit about this. Ultimately no challenge was made to these findings. The essence of the argument was that the primary judge should have found that the reputation of Stone & Wood in the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” was such that, whatever the difference in packaging, labelling and get-up, there must necessarily have been conveyed a representation that Thunder Road Pacific Ale or Pacific was connected or associated with Stone & Wood or its Pacific Ale.

35 These findings undermine to a significant degree, if not wholly, the reliance on the well-known passages from Australian Woollen Mills referred to earlier.

36 At [115]-[119] of the reasons, the primary judge dealt separately with Thunder Road Pacific whose get-up was as follows:

|

|

37 The primary judge set out his findings in relation to the “Thunder Road Pacific” product at [119] of his reasons. His Honour concluded that the labels and packaging were virtually the same as those for “Thunder Road Pacific Ale”, as can be seen from the images. In relation to the beer taps, his Honour noted that the dominant branding on the Thunder Road decal was the word “Pacific” whereas on that for the Stone & Wood product it was the words “Stone & Wood”. The main colour of the Stone & Wood decal was the mustard colour, whereas for the Thunder Road Pacific one it was a “bright and vibrant orange”.

Other beers using the name “Pacific Ale” or “Pacific”

38 At [122]-[134] of the reasons, the primary judge discussed the evidence and made findings concerned with other beers using the words “Pacific Ale” or “Pacific”. We have already referred to Sunshine Coast Brewery’s small commercial batch which the primary judge put to one side (see [122] of the reasons and [33(2)] above). At [134], the primary judge made the following findings:

(a) Apart from the products which are the subject of this case, there are three examples of beers available on the Australian market which incorporate ‘Pacific’ or ‘Pacific Ale’ in the name of the company or product. These are Yeastie Boys’ Stairdancer Pacific Ale (where a licence has been entered into with Stone & Wood); Garage Project’s Hapi Daze Pacific Pale Ale; and the Pacific Beverages Radler. Only one of these – the first – is named ‘Pacific Ale’. It is to be inferred that it commenced to be sold in Australia in or about May/June 2015 (that is, after the launch of Thunder Road Pacific Ale).

(b) In addition, there is one beer available for sale on the Australian market which uses the word ‘Pacific’ in the description of the beer. This is Australian Brewery’s Pale Ale. The words ‘Pacific Pale Ale’ appear on the lower part of the front of the can.

(c) Although the position was different when Stone & Wood launched its Pacific Ale product, since then the term ‘Pacific’ has come to “serve a function of describing beers made from hops from Australia and New Zealand”, as was accepted by Mr Kirkegaard; the term has come to be associated with the use of Australian Galaxy hops (as was also accepted by Mr Kirkegaard).

…

39 Stone & Wood challenged finding (c) above in ground 4 of the Notice of Appeal, along with similar findings at [206], [207] and [211] of the reasons to which we will come. As discussed in more detail below, the importance of that finding is that there is within the words the capacity for an association to be of a descriptive (even though imprecise) character. Given this challenge, it is worth setting out at this point some of the evidence relied upon by the primary judge. At [130] the primary judge set out an exchange between Elixir’s senior counsel (Mr Golvan) and Mr Kirkegaard:

… The term “Pacific”, insofar as it may be used as a form of description, is an apt description for the type of hops being used, that’s to say, Australian or New Zealand hops, isn’t it?---Well, I – I guess that’s up to debate, and, I guess, it depends on the – the context that it has been used in. For example, Pacific Northwest is often used to describe hops from – well, Pacific hops can be used to describe hops from the Pacific Northwest, which is the north of America, or it can be used to describe hops from the oceanic region of Pacific as well.

All right. But in the context of the Australia/New Zealand environment it’s fair to say, is it not, that if the term “Pacific” is being used, it does serve a function of describing beers made from hops from Australia or New Zealand?---More recently it has, yes.

Yes?---I – I don’t think – and again, if you went back five – six – seven years, the term … tended to be “new world hops” to describe Australian and New Zealand hops.

All right. But in recent years that has been an apt description?---It – it has come to be used, yes.

… Now, so you refer to recent years where that – the term “Pacific” has become an apt describer of this origin of the hops; right?---It – it has come be used, yes.

Come to be used. So, like, since 2013?---Yes, it has gradually evolved over the last three or four years, yes.

(emphasis added by primary judge)

40 It is to be recalled that the Stone & Wood website in describing the launching of the renamed Pacific Ale gave a very similar explanation (see [23] above).

41 At [132] the primary judge referred to similar cross-examination on Mr Kirkegaard’s second affidavit:

In his second affidavit, Mr Kirkegaard said that, in his view, ‘Pacific Ale’ would only have meaning to beer consumers if they had consumed the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or, more recently, the Thunder Road Pacific Ale product. He was taken to this evidence during cross-examination and the following exchange then occurred between senior counsel for the respondents and Mr Kirkegaard:

Is that a comment on consumers having an appreciation for the character of the product?---Yes. What I was alluding to there is that the term “Pacific ale” has no inherent meaning. It only derives its meaning subsequent to the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. Before then, “Pacific ale” I don’t believe was used, except in a most general sense and it could have been across any number of styles and for any number of reasons, but I think the growing use of “Pacific” these days, primarily in New Zealand and other parts of the world, derives from the understanding that “Pacific ale” to mean a certain class of ale comes from a Stone & Wood Pacific Ale style beer or like beer.

Yes. And that’s because you say Stone & Wood introduced the Pacific ale character beer - - -?---Yes.

- - - in 2010 - - -?---A beer with those characters. Yes.

- - - and since that time it has become associated with the use of Australian Galaxy hops?---That’s correct. Yes.

And it has become associated with the character that you described at paragraph 63 of your – of your first affidavit?---That’s correct. Yes.

And that has happened over a period of the last two or three years or so?---I believe that’s – it goes back to Stone & Wood calling their beer Pacific Ale, and we’ve gradually seen – and it’s almost like ripples in a pond. They gradually spread.

Yes. And one of those ripples that we can identify certainly is the coming into the market in March 2013 of the Australian Brewery product that we’ve been talking about?---Yes.

(emphasis added by primary judge)

As the primary judge noted the reference to paragraph 63 was to the following (cited by the primary judge at [70]):

The Stone & Wood Pacific Ale incorporated a bursting hop aroma of tropical fruit more commonly experienced in beer styles such as American Pale Ale or India Pale Ale, but over a much lighter, crisper body more closely associated with an Australian Pale Ale. The hop aroma was very distinctive, showcasing the signature passionfruit and lychee notes of Galaxy hops but in a much bolder manner than other beers that had used that variety of hops.

42 Significant emphasis was placed by senior counsel for Stone & Wood (Mr Crutchfield QC) upon what Mr Kirkegaard said in re-examination in order to deflect the force of this evidence. This re-examination was referred to by the primary judge at [131]:

In re-examination, Mr Kirkegaard was asked who uses the word ‘Pacific’ in connection with Australian or New Zealand hops – brewers or consumers or both? He said that it was predominantly used by brewers and hop growers and said, “I don’t know that it’s a generally used consumer term”.

“Styles” of beer

43 At [135]-[142] of the reasons, the primary judge dealt with the issue of “styles” of beer. Evidence had been adduced as to whether “Pacific Ale” was a style of beer, as it was asserted to be by the respondents and denied to be by Stone & Wood. His Honour described how style guidelines are used in beer competitions and, outside of this, whilst they can describe what customers can expect in a beer in terms of flavour and characteristics in a general sense, there may in fact be considerable scope for difference within styles. Indeed, Mr Kirkegaard was of the view that the “style name” of a beer can often relate to marketing choices made by the brewer as much as the beer’s physical characteristics. Evidence was provided to the effect that Stone & Wood considered “Pacific Ale” to be a style of beer in 2010. However, the primary judge ultimately concluded at [142] that “Pacific Ale” was not a style of beer in the technical sense of a style identified in style guides used in beer competitions. He found that some consumers may regard “Pacific Ale” as a style of beer in a non-technical sense but it was not established that a substantial number of consumers would regard it as such. Those findings were made by the primary judge recognising the view of those at Stone & Wood expressed on its website (see [23] above), statements to similar effect by Mr Cook reported in the article written by Mr Kirkegaard (referred to at [73] of the reasons), the email to Mr Withers from Mr Paige at the time of the launch of Thunder Road Pacific Ale (referred to in [97] of the reasons and at [33(3)] above), and Mr Withers’ evidence in cross-examination to the following effect (referred to at [140] of the reasons):

Well, the definition of “style” is not official. There … [are] no style guidelines. There … are guidelines that people refer to for competitions, but styles in beer have evolved and are continually changing and have been around for hundreds of years, so when a new flavour profile develops, then it’s apt that there is a descriptor, and by definition you need to find a suitable descriptor and by having a descriptor for a new flavour profile you end up with a style.

44 The findings about “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” not being a style are related to the primary judge’s finding as to the descriptive aspect of the word “Pacific” at [205] and following of the judgment to which we will come: see [65]-[67] below. At this point it can simply be noted that at [207] the primary judge said that his conclusions about style do not gainsay the proposition that the word “Pacific” has a descriptive aspect to it.

Sale of beer at licensed premises, bottle shops and other retail liquor stores

45 The primary judge considered the evidence and made findings about these matters at [143]-[149] (licensed premises), and at [150]-[154] (bottle shops and other retail liquor stores).

Licensed premises

46 At [143] of the reasons, the primary judge found that there were typically two types of transactions in licensed premises: a tap purchase, and being handed a bottle by the bartender.

47 At [144] to [148], the primary judge examined the evidence of Mr Kirkegaard, Mr Coorey, Mr Crooks, Ms McGrath and Mr Omond.

48 All these witnesses gave evidence of their own experience of the sale and purchase of beer at licensed premises which the primary judge accepted as accurate descriptions.

49 Mr Kirkegaard gave evidence that in his experience many consumers refer to the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale as “Pacific Ale” or “Pac Ale”. But he did say in cross-examination that people were more likely to ask “What pale ales have you got?” because of the range, and that brand names were often used.

50 Mr Coorey gave evidence of sale of beer at a tavern in Brisbane; Mr Crooks at a craft beer café in New South Wales; Ms McGrath at a hotel in South Melbourne and Mr Omond of a visit to a bar in Melbourne.

51 At [149], the primary judge made findings from this evidence as follows:

(a) In many cases, the beer taps (with the decals) are visible to the customer when ordering a beer on tap at a bar or hotel.

(b) In many cases, a licensed venue will only sell one or the other of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or Thunder Road Pacific on tap, rather than both.

(c) In the context of craft beers, in some cases there will be interaction between the bartender and the customer about the brewery and particular product. A theme running through the evidence of several witnesses was that, in the context of craft beers, bartenders will on occasion tell customers about the brewery and the beer.

(d) In some licensed venues which sell Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, there is a close association between ‘Stone & Wood’ and ‘Pacific Ale’ among customers who have purchased the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, and many of those customers refer to the product simply as ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pac Ale’.

(e) I do not think it is established that there is any actual or likely confusion (as between the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific) among customers who purchase beer at licensed venues. There is no evidence of any actual confusion. As noted above, in many cases, licensed venues only sell one or the other of the products, rather than both. The decals for the beer taps are often visible (although not always) to customers when ordering tap beer, and these make quite clear whether the product is the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or the Thunder Road Pacific. To the extent that, as noted above, at some licensed venues, customers refer to the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale simply as ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pac Ale’, this usage is in a context where the venue sells the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale (and not the Thunder Road product) and the customer has previously purchased the product. As I see it, it is an abbreviation for the product in that context. It does not follow that the customer would be likely to use that expression at a different venue which sells the Thunder Road product, not see the beer tap decal or other information indicating the product is the Thunder Road product, and thus mistakenly order the product thinking it is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. There is no evidence of such confusion occurring and I think the prospect of it occurring is remote.

(f) I do not think the photograph annexed to Mr Omond’s first affidavit, and the evidence in his affidavit, demonstrates any actual or likely confusion among customers. Notwithstanding the ambiguity of the words ‘Pacific Ale’ on the sign, any customer is likely to see the beer taps before ordering; the decal for the Thunder Road Pacific is likely to make clear to the customer that this is the product being offered. In any event, the sign was presumably prepared by the bar; there is no suggestion that it was prepared by the respondents. Thus it is hard to see how the respondents could be held responsible for any confusion arising from the sign.

Bottle shops and other retail liquor stores

52 At [150] to [153], the primary judge examined the evidence of Mr Kirkegaard, Mr Piperno, Mr Omond and Mr Cleaver who once again gave evidence of their experience, this time in bottle shops and retail stores. Once again, the primary judge accepted their evidence as accurate recounting of their experience. At [154], his Honour made the following findings:

(a) I do not think it is established that there is any actual or likely confusion (as between the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale or Thunder Road Pacific) among customers who purchase beer at bottle shops or other retail liquor stores. There is no evidence of any actual confusion. Some bottle shops which sell craft beer arrange the beers by the brewery, while others arrange them by categories or broad flavour characteristics. If the beers are arranged by category, and the bottle shop sells both the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific, there is unlikely to be confusion between the two products. They are likely to be located near to each other in this scenario, and the differences in the labelling and packaging would make clear that they are different products. Even if the beers are not located close to each other, the prospect of any confusion is low in light of the distinct labelling and packaging (as discussed above). Also, if all the products from one brewery are located together, the effect would be to emphasise the identity of that brewery, making confusion unlikely.

(b) The situation described in Mr Omond’s second affidavit does not suggest any actual or likely confusion between the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific. The sign above the cartons contrasted the two brands, Stone & Wood and Thunder Road, thus emphasising that they are different. Further, the packaging on the Thunder Road cartons clearly identified Thunder Road as the producer.

Consumer purchasing behaviour

53 At [155]-[166] of the reasons the primary judge dealt with the evidence of Professor Lockshin as to consumer behaviour, Mr Jane as to brand design and the evidence of Mr Camilleri as to marketing. At [156] of the reasons, the primary judge summarised Professor Lockshin’s evidence as follows:

The gist of Professor Lockshin’s evidence, as summarised in the abstract to his report, was that consumers do not shop and purchase items from retail stores based on a side-by-side comparison with other products in the same category; rather, consumers ‘learn’ what products fulfil their needs and preferences and then make purchase decisions using their subconscious memory of the cues that link to the product; these cues are often a single word, colour or logo. Professor Lockshin did not carry out any tests in relation to the products in issue, namely Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific. He was not asked to do so. Professor Lockshin accepted that it would be possible to test the propositions in his report in relation to the products in issue.

54 From [157]-[162], the primary judge examined in detail and with care Professor Lockshin’s report; and at [163]-[164], the debate between Professor Lockshin and Mr Jane about packaging and consumer cues; and at [165] the evidence of Mr Camilleri on colour, cues and consumer behaviour.

55 At [166], the primary judge made findings as follows:

(a) I accept that, generally speaking, consumers purchasing goods do not shop and purchase items from retail stores based on a side-by-side comparison with other products in the same category; rather, consumers ‘learn’ what products fulfil their needs and preferences and then make purchase decisions using their subconscious memory of the cues that link to the product; these cues are often a single word, colour or logo. This was the effect of Professor Lockshin’s evidence. Mr Camilleri’s evidence was consistent with this.

(b) However, I do not think it is established, in the absence of tests in relation to the products in issue, that consumer purchasing behaviour in relation to the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific is likely to occur in the way described by Professor Lockshin. Having stated (in paragraph 20 of his report) that “[o]bviously” the Stone & Wood name is the most prominent feature of the packaging of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, and would likely be the first cue recognised by consumers when they are learning about the beer, Professor Lockshin expressed the opinion (in paragraph 35) that “it is likely that consumers have learned to identify the different Stone & Wood products by their sub-brand names and learned which sub-brand they prefer”. However, a plausible alternative is that consumers have learned to identify the brand ‘Stone & Wood’, or the composite brand and product ‘Stone & Wood Pacific Ale’, with the product they prefer. Thus the “cue” or “distinctive asset” (cf paragraph 37 of the report) for the product may be ‘Stone & Wood’ or ‘Stone & Wood Pacific Ale’ rather than ‘Pacific Ale’. Further, the particular context of craft beer may affect the way consumers approach purchasing decisions – see, for example, Mr Kirkegaard’s evidence set out in paragraphs [62] and [64] above. In the absence of testing, I am not satisfied that consumer purchasing behaviour in relation to the products in issue would follow the pattern described in Professor Lockshin’s evidence.

56 An important part of Stone & Wood’s arguments on appeal focused on what was said to be the illegitimate downgrading of the weight and importance of Professor Lockshin’s evidence. It was part of a broader central proposition that the primary judge did not give adequate weight to the significant reputation of Stone & Wood in the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” and that these words, especially “Pacific”, acted as a subconscious cue that the different packaging could not ablate.

Passing off and the Australian Consumer Law claims

Legal principles

57 From [173] to [194] of the reasons, the primary judge discussed the legal principles governing the resolution of these claims. No submission was made that his Honour misdirected himself as to any of those principles.

Stone & Wood’s submissions to the primary judge

58 At [198] and [199], the primary judge summarised the submissions of Stone & Wood as to the second contention (now on appeal the sole basis of complaint): that Elixir’s use of the words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” represents to consumers that there is a connection or association between Thunder Road products (and so the respondents) and Stone & Wood or Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

59 The submissions put by Stone & Wood, and summarised by his Honour at [198] and [199] reflect the submissions put on appeal. They were as follows:

(1) The words “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” as used by Stone & Wood from 2010 up to January 2015 had become distinctive of Stone & Wood and acted effectively as a common law trade mark. The evidence of Mr Kirkegaard and the trade witnesses was said to be testimony to the strong association of “Pacific Ale” with Stone & Wood and Stone & Wood Pacific Ale: [198(a)].

(2) The adoption by Elixir of the names “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” since 2015 has been prominent and the dominant message of the Thunder Road branding. In doing so Elixir is calling upon and exploiting the reputation and goodwill of Stone & Wood in “Pacific Ale”. This involves a misrepresentation of connection or association: misrepresenting the goods in such a way by this association or connection as to cause damage to Stone & Wood’s business or goodwill (Reckitt & Colman Products v Borden Inc (1990) 17 IPR 1 at 18-19; HP Bulmer Ltd v J Bollinger SA [1978] RPC 79 at 99 and 117; Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at 88-89, citing Deane J in Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd [1984] HCA 73; 156 CLR 414 at 445): see [198(b) and (c)].

(3) The evidence of Professor Lockshin and Mr Jane exposed and underpinned these propositions. The names “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” are used as the dominant branding feature by Elixir and as the subconscious “hook” to influence consumers to associate Thunder Road Pacific Ale and Pacific with Stone & Wood, to which they have become accustomed: [198(c)-(f)].

(4) Brewers of craft beer use packaging and design elements to permit consumers to identify their products as craft beers. This gives a starting point of familiarity with the product. From this the names used are the important cues, along with get-up, colour and labels. Thunder Road has the greatest emphasis on “Pacific Ale” and “Pacific” – this is the attraction, hook or cue. Thus the representation is made out: [198(g) and (h)].

(5) The abandonment of “Ale” did not change anything. The word “Ale” is not distinctive: [199(a) and (b)].

(6) Stone & Wood does not claim a monopoly over the word “Pacific”. Rather, in its proper craft beer context and used in the way it has been it involves the misrepresentation claimed. This involves the use of a sufficiently similar colour scheme as to assist in the representation. (It should be noted at this point that on appeal Stone & Wood’s submissions did not dwell at all on any deceptiveness in the colour scheme.)

The primary judge’s conclusions

The first contention

60 The primary judge concluded that it had not been established that there was any (mis)representation that Thunder Road Pacific Ale or Pacific was Stone & Wood Pacific Ale: see [202] and [203], in particular finding:

202 … A starting place in considering this alleged representation is the simple fact that nowhere on the relevant Thunder Road products is there any reference to Stone & Wood. Thus there is certainly no express representation that either of the Thunder Road products is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The next point to note is that, as described in paragraphs [114] and [119] above, the labelling and packaging of the Thunder Road products are very different from the labelling and packaging of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The dominant feature of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is the ‘Stone & Wood’ brand name, while the dominant feature of the Thunder Road products is the word ‘Pacific’. The colours are different. There are many other differences as well. All in all, the overall ‘look and feel’ of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is very different from the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific. In these circumstances, it is not established that the respondents represented that each of the Thunder Road products is the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

203 …

(a) [In discussing the example of a bar in Melbourne, the Bar Nacional, where a sign had “Pacific Ale” and Thunder Road was sold] … I do not think it establishes any likelihood of customers ordering a drink thinking that they are ordering the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale when in fact they would be ordering the Thunder Road Pacific. …

(b) In relation to the second example put forward by Stone & Wood, which relates to ordering in a pub, bar or restaurant, I think it unlikely that the customer in that example would order one product thinking he or she was ordering the other as submitted by Stone & Wood. The decals are quite distinct. The words ‘Stone & Wood’ are not present on the Thunder Road Pacific decal and the colours are different. Taking these matters into account, I think it is unlikely that a customer who orders the beer at a distance (the scenario posited by Stone & Wood), seeing the word ‘Pacific’, will think he or she is ordering the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. It is also relevant to take into account that, in the context of craft beer, as the evidence described above indicates, there tends to be a higher level of customer involvement in the choice of the beer, and a greater degree of interaction between bartender and customer about the choice of beer, than in relation to mainstream beer. In any event, in circumstances where the respondents’ decal has the words ‘Thunder Road’ on it, the proposition that the respondents have, through the use of that decal, represented that their product is the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, is not established.

(c) In relation to bottle shops or retail liquor outlets, for the reasons given in paragraph [154] above, I do not think the example given by Stone & Wood is likely to occur. In any event, the question is whether the respondents made the first alleged representation. In circumstances where the labels and packaging of the Thunder Road products do not contain any reference to Stone & Wood, contain clear references to Thunder Road, and look very different, it is not established that the respondents represented that each of the Thunder Road products is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

61 Although there was no appeal from the dismissal of the claim upon the basis of the asserted misrepresentation that Thunder Road Pacific Ale or Pacific was Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, these findings are relevant to the second contention based on asserted association or connection.

The second contention

62 At [204]-[213] of the reasons, the primary judge rejected the case made based on the asserted association or connection between the Thunder Road product and Stone & Wood or the Stone & Wood product.

63 The reasoning of the primary judge was as described in the following paragraphs. It is important, at the outset, to recall the descriptions of the consumers in [58]-[66] of the reasons and discussed at [16]-[20] above. The consumer in the market is one who is alive to the different identity and products of the brewers and who is interested and attentive to what is being sold. This is not legalism; this is the appreciation of the human features of the commercial milieu into which the product (craft beer) is being sold.

64 The primary judge began by referring to the labels and packaging. There was no reference to Stone & Wood. The labels and packaging were very different. The dominant feature of the Stone & Wood products is the name Stone & Wood; whilst the dominant feature of the Thunder Road products is “Pacific Ale” or “Pacific”. Even though these words are the dominant feature “Thunder Road” is placed clearly on the bottle and on the decal. The branding of Elixir should thus be viewed as apt to identify Thunder Road as the source of Pacific in a very different colour scheme. This difference was reinforced by the uniformity of (different) formats for the Thunder Road range and the Stone & Wood range: see generally [204] and [209].

65 The next feature of the evidence focused upon by the primary judge was what he found to be the “descriptive” aspect of the word “Pacific”. At [205], the primary judge said the following:

In my view, the word ‘Pacific’ has a descriptive aspect to it when used in relation to both Stone & Wood’s and the respondents’ products. ‘Pacific’ is, of course, the name of the Pacific Ocean. It can be used adjectively to refer to someone or something that pertains to the Pacific Ocean (for example, Pacific islander, Pacific solution). It is also an adjective which means peaceful or calm (among other meanings). That the word has a descriptive aspect is underlined by the reasons why Stone & Wood chose the name in the first place. The first was that one of the Stone & Wood breweries (the only one in operation in 2010) is located in Byron Bay, which is situated on the Pacific Ocean. The second reason was to generate a calming, cooling emotional response in consumers. This evidence calls to mind the observation of Stephen J in Hornsby, quoted above: “There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name”. In the present case, by choosing a name for its product that has a descriptive aspect to it, Stone & Wood ran the risk that others in the trade would use it descriptively and that it would not distinguish its product.

66 Stone & Wood attacked this finding, as will be discussed in due course: see [98]-[100] below. At this point it is perhaps worth saying that the word “descriptive” is perhaps inadequate. What is the subject of consideration is the use of the words in their commercial and physical context to create a reputation through a capacity to distinguish the goods of the trader. In this kind of context (such as s 41(3) of the Trade Marks Act) it may become relevant to assess the capacity of a word to distinguish the goods of one trader from the goods of another. The relevant concepts are not binary in nature: descriptive or distinguishing. Language is more subtle than that. A word may have no precise meaning but be capable of evoking geographic as well as metaphoric resonances, without being particularly apt to distinguish goods of rival traders. See, for example, the word “Colorado” in the context of clothes and s 41 of the Trade Marks Act in Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 184; 164 FCR 506 at 538-540 [120]-[128].

67 The primary judge reinforced this finding about the descriptive quality of the word “Pacific” (in [205]) by his reference in [206] to the development of the uses and meaning of the word in this very market:

Further, although the position was different when Stone & Wood launched its Pacific Ale product, since then the term ‘Pacific’ has come, as Mr Kirkegaard accepted, to “serve a function of describing beers made from hops from Australia and New Zealand” (see paragraph [134] above). Thus the word ‘Pacific’ has come to be used descriptively in this sense. In these circumstances, it is difficult for Stone & Wood to establish that the name ‘Pacific Ale’ distinguishes its beer from the beer of other traders.

68 Stone & Wood developed its product in 2010. The first impugned conduct of Elixir was in January 2015. The descriptive quality had begun to develop before then. Mr Kirkegaard’s evidence was that in the three to four years before the case (April 2016) the word “Pacific” had come to be used for beer made from hops in Australia and New Zealand.

69 The primary judge then noted (at [207]) that he had concluded that “Pacific Ale” is not a style of beer in the technical sense as used in beer style guides and that the evidence does not establish that a substantial number of consumers view it as a style; but, that, his Honour said, “does not gainsay the proposition that the word ‘Pacific’ has a descriptive aspect to it …”.

70 At [208], the primary judge noted the dominance of the Stone & Wood branding and packaging, and on the decal. This makes it, he found, less likely that the words “Pacific Ale” would distinguish Stone & Wood’s product. In this context Professor Lockshin’s evidence was dealt with as follows:

… To the extent that Stone & Wood relies on the evidence of Professor Lockshin, for the reasons given in paragraph [166] above, I do not think it is established, in the absence of tests in relation to the products in issue, that consumer purchasing behaviour in relation to the products in issue is likely to occur in the way described in his evidence.

See [55] above for [166] of the reasons.

71 The primary judge then turned (at [210]) to the findings that he had made that Elixir had to some extent sought:

… to take advantage of the success of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale (for example, by consumers familiar with the Stone & Wood product wanting to try the Thunder Road offering with the same name), but that it is not established that Elixir intended to obtain any such advantage through consumers thinking that the Thunder Road product was Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or that there was an association or connection between the Thunder Road product and Stone & Wood or its product.

(italics in original)

72 The primary judge then referred to his earlier discussion at [179]-[180] of the reasons of the cases that distinguish between an intention to deceive and an intention to take advantage of some aspect of the market that may have been developed by the complainant. Central to that was the passage from the judgment of the Privy Council (delivered by Lord Scarman for a Board that included Lord Wilberforce) in Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Pub Squash Co Pty Ltd [1980] 2 NSWLR 851 at 861 [35]:

Once it is accepted that the judge was not unmindful of the respondent’s deliberate purpose (as he found) to take advantage of the appellant’s efforts to develop “Solo”, the finding of “no deception” can be seen to be very weighty: for he has reached it notwithstanding his view of the respondent’s purpose. But it is also necessary to bear in mind the nature of the purpose found by the judge. He found that the respondent did sufficiently distinguish its goods from those of the appellants. The intention was, not to pass off the respondent’s goods as those of the appellants, but to take advantage of the market developed by the advertising campaign for “Solo”. Unless it can be shown that in so doing the respondent infringed “the plaintiffs’ intangible property rights” in the goodwill attaching to their product, there is no tort: for such infringement is the foundation of the tort: see Stephen J, in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Pty Ltd.

(emphasis added by primary judge)

The question is whether there has been a misrepresentation as to connection or association.

73 The primary judge then (at [211]) distinguished the case from the Budweiser Case 56 IPR 182. The primary judge (not only understandably, but correctly) saw the cases as quite different factually, saying:

… But in that case the word operated as such a hook because the word ‘Budweiser’ was a well-known mark, with brand reputation, and was not a descriptive word to Australian English speakers. In the absence of these features, I do not think the use of the word ‘Pacific’ is likely to operate as a ‘hook’ which associates the relevant Thunder Road products with Stone & Wood or Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

74 This was the primary judge’s reasoning for dismissal of the cases for passing off and under the Australian Consumer Law.

The appeal

75 On the appeal, Stone & Wood challenge the primary judge’s dismissal of their claims for passing off, misleading or deceptive conduct and making false representations based only on the second contention by attacking a number of the findings made by the primary judge in respect of the evidence in the proceeding. The key submission for Stone & Wood was that the primary judge failed to recognise the form of passing off that had occurred in this case as to an impression of an association between the Stone & Wood and Thunder Road products. Stone & Wood focused its case on appeal on establishing the tort of passing off, contending that if this was made out then it would also succeed in establishing contraventions of ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law.

76 There were six issues tendered for consideration on the appeal. They were expressed in the Notice of Appeal, and in a document entitled “Joint List of Issues” provided by the parties after the hearing of the appeal. These six issues were expressed in the Notice of Appeal, as follows:

1. The primary judge erred in dismissing the Appellants’ claims in passing off and under ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law because the Respondents’ adoption and use of the names Pacific Ale and Pacific in relation to beer:

(a) called upon and exploited the goodwill and reputation held by the Appellants’ [sic] in the name Pacific Ale;

(b) thereby implicitly established a connection or association in the minds of relevant consumers in Australia between:

(i) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer;

(ii) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants; and/or

(iii) the Respondents and the Appellants; and

(c) damaged the goodwill and reputation held by the Appellants in the name Pacific Ale by diminishing the distinctiveness of that name in the marketplace.

Taken together, these matters were sufficient to found an actionable misrepresentation in passing off and under s 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law.

2. Having found that:

(a) the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer had a substantial reputation in the craft beer market, such that many consumers referred to that beer simply as “Pacific Ale” (at [91], [149(d)] and see also [144]-[147], but compare [206]);

(b) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale Beer have a similar taste and aroma (at [114(a)] and [114(h)], and see also [96]);

(c) at the time the Respondents launched their Pacific Ale beer, the only beer named Pacific Ale being sold in Australia was the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer (at [114(b)], and see also [107], [109] and [151]);

(d) at the time the Respondents launched their Pacific Ale beer, the Respondents knew that the name Pacific Ale had come to be very closely associated with the Appellants in Australia (at [114(d)], and see also [103], [107] and [109]);

(e) the dominant feature of the label of the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer is the name Pacific Ale or Pacific (at [114(e)], [119(a)], [202], [204] and [209], and see also [103]);

(f) the dominant feature of the beer tap decal for the Respondents’ Pacific draught beer is the name Pacific (at [119(b)], [202], [204] and [209]);

(g) the Respondents chose the name Pacific Ale for their beer to (at least to some extent) take advantage of the success of the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer (at [114(h)] and [210]);

(h) some consumers do not shop for and purchase items based on side-by-side comparisons with other products in the same category, but rather make purchasing decisions using subconscious memory cues that they have learnt (at [166(a)]),

the primary judge erred in finding (at [11(a)], [114(h)], [200] and [212]) that the Respondents had not, by their use of the names Pacific Ale and/or Pacific in relation to beer, represented to consumers that there is an association or connection between:

(i) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer;

(j) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants; and/or

(k) the Respondents and the Appellants.

3. In making the finding (at [11(a)], [114(h)], [200] and [212]) that the Respondents had not, by their use of the names Pacific Ale and/or Pacific in relation to beer, represented to consumers that there is an association or connection between

(a) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer;

(b) the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants; and/or

(c) the Respondents and the Appellants,

the primary judge erred because that finding rests upon the primary judge:

(d) wrongly giving no, or insufficient, weight to aspects of the evidence;

(e) wrongly giving too much weight to aspects of the evidence;

(f) making other erroneous findings of fact.

Particulars

(i) The primary judge wrongly gave:

(A) insufficient weight to the evidence of Mr Withers and Mr Camilleri in relation to the reason for the selection by the Respondents of the name Pacific Ale (see [97], [98], [103] – [107] and [109]);

(B) no, or insufficient, weight to the informal, social and/or casual situations in which beer is commonly ordered and consumed at licensed venues (see [143] – [149], [196(a)] and [203(a) and (b)]);

(C) insufficient weight to the expert evidence of Professor Lockshin and Mr Jane (see [155] – [166]).

(ii) The primary judge wrongly gave too much weight to:

(A) the differences between the packaging of Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer and the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer (see [114(e) – (h)], [154(a)], [202], [203(c)], [204] and [209]);

(B) the differences between the beer tap decals used in licensed venues in relation to the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer and the Respondents’ Pacific beer (see [149], [203(b)] and [209]).

(iii) The primary judge erroneously found:

(A) (at [114(h)]) that the differences between the packaging of the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer and the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer strongly suggested that the Respondents did not intend to obtain an advantage by consumers thinking that there was an association between those beers;

(B) (at [149(e)]) that there was no likely confusion between the Respondents’ Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer among customers who purchase beer at licensed venues;

(C) (at [154(a)]) that there was no likely confusion between the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer and the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer among customers who purchase beer at bottle shops or other retail liquor stores;

(D) (at [211]) that Pacific is not a well-known trade mark to relevant consumers in Australia;

(E) (at [211]) that Pacific does not have a reputation as a brand amongst relevant consumers in Australia;

(F) (at [211]) that the word Pacific is unlikely to operate as a “hook” which associates the Respondents’ Pacific Ale / Pacific beer with the Appellants’ Pacific Ale beer.

4. The primary judge erred in finding (at [134(c)], [206], [207] and [211]) that the term Pacific was as at January 2015, or has come to be, a descriptor amongst consumers for beers made from hops from Australia and New Zealand.