FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Apotex Pty Limited (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 26

ORDERS

First Appellant PF PRISM CV Second Appellant PFIZER IRELAND PHARMACEUTICALS (and others named in the Schedule) Third Appellant | ||

AND: | APOTEX PTY LIMITED ACN 096 916 148 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the respondent to amend its notice of cross-appeal dated 27 February 2017 by deleting Grounds 7, 8 and 9.

2. The respondent’s interlocutory application dated 27 February 2017 otherwise be dismissed, with costs.

3. The cross-appeal be dismissed, with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The appellants’ grounds of appeal have been determined in our earlier judgment: Warner-Lambert Co LLC v Apotex Pty Limited [2017] FCAFC 58; (2017) 249 FCR 17.

2 However, the respondent in the appeal, Apotex Pty Ltd, has cross-appealed from the judgments given on 21 October 2016 and 15 February 2017 in which the primary judge dismissed the respondent’s originating application filed on 8 May 2013 seeking revocation of claims 1 to 32 of Australian Patent No. 714980 (the patent) for invalidity, and made orders for quia timet injunctive relief in respect of the respondent’s threatened infringement of claims 1 to 31.

3 So far as invalidity is concerned, the notice of cross-appeal is directed to the primary judge’s rejection of the respondent’s case that claims 1 to 32 are invalid by reason of insufficiency of description and because the patent had been obtained on a false suggestion. The notice of cross-appeal is also directed to the primary judge’s rejection of the respondent’s case that the invention, as claimed, lacks utility. That challenge is no longer pressed.

4 The appellants, Warner-Lambert Company LLC and four related entities that form part of the Pfizer Group of companies, have filed a notice of contention seeking to support the primary judge’s rejection of the respondent’s case on insufficiency and false suggestion (the notice of contention).

5 So far as infringement is concerned, the notice of cross-appeal is directed to the primary judge’s finding that the respondent threatened to infringe claims 16 to 30 of the patent. These claims are, in form, “Swiss” claims: see Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (Otsuka) [2015] FCA 634; (2015) 113 IPR191 at [100]-[121].

6 Relatedly, the respondent has filed an interlocutory application in its cross-appeal by which it seeks leave to withdraw certain admissions it has made in relation to claim 31 of the patent and to make a corresponding amendment to the grounds of its notice of cross-appeal to allege that the primary judge erred in finding that it had threatened to infringe that claim. It also seeks to amend its cross appeal by removing paragraphs concerning the lack of utility ground.

7 The specification in suit is AU 199736024 B2 (the specification).

8 The priority date of the claims is 24 July 1996.

9 The questions of validity raised in the cross-appeal are governed by the terms of s 40(2)(a) and s 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) before the amendments introduced by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

10 Section 40(2)(a) provides:

A complete specification must:

(a) describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; …

11 Section 138 provides:

(1) Subject to subsection (1A), the Minister or any other person may apply to a prescribed court for an order revoking a patent.

(1A) ...

(2) ...

(3) After hearing the application, the court may, by order, revoke the patent, either wholly or so far as it relates to a claim, on one or more of the following grounds, but on no other ground:

(a) …

(b) …

(c) [repealed]

(d) that the patent was obtained by fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation;

(e) …

(f) that the specification does not comply with subsection 40(2) or (3).

The invention

12 The invention concerns the use of analogs of glutamic acid and gamma-aminobutyric acid in pain therapy, especially in the treatment of chronic pain disorders.

13 Claims 1 to 15 define the invention as a method of treatment. As we have noted, claims 16 to 30 are Swiss claims. All the claims are based around “a compound of Formula I” or more specific examples of that compound. The patent recites that the compounds are not new. They were known to be useful in antiseizure therapy for central nervous system disorders. Broadly described, the invention is the application of these known compounds to a new therapeutic use.

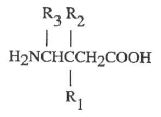

14 Claim 1 is:

1 A method for treating pain comprising administering a therapeutically effective amount of a compound of Formula I

or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, diastereomer, or enantiomer thereof wherein

R1 is a straight or branched alkyl of from 1 to 6 carbon atoms, phenyl, or cycloalkyl of from 3 to 6 carbon atoms;

R2 is hydrogen or methyl; and

R3 is hydrogen, methyl, or carboxyl to a mammal in need of said treatment.

15 Claim 2 is:

2 A method according to Claim 1 wherein the compound administered is a compound of Formula I wherein R3 and R2 are hydrogen, and R1 is

-(CH2)0-2-i C4H9 as an (R), (S), or (R,S) isomer.

16 The specification refers to these compounds as “preferred compounds”. They are a subset of the claim 1 compounds and are identified, in terms, in their enantiomeric ((R) and (S)) and racemic ((R,S)) forms.

17 Claim 3 is:

3 A method according to Claim 1 wherein the compound administered is named (S)-3-(aminomethyl)-5-methylhexanoic acid and 3-aminomethyl-5-methyl-hexanoic acid.

18 The specification refers to these as “more preferred compounds”. They are a further subset of the claim 1 compounds. The (S)-enantiomer of 3-aminomethyl-5-methyl-hexanoic acid is called pregabalin. We will refer to the second compound, 3-aminomethyl-5-methyl-hexanoic acid, as the 3-amino compound. The primary judge found that the specification refers to the 3-amino compound in its racemic form.

19 The form of the Swiss claims is exemplified by claim 16:

16 Use of a compound of Formula I

or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt diastereomer or an enantiomer thereof wherein R1 is a straight or branched alkyl of from 1 to 6 carbon atoms, phenyl, or cycloalkyl of from 3 to 6 carbon atoms;

R2 is hydrogen or methyl; and

R3 is hydrogen, methyl, or carboxyl

in the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of pain.

20 Claim 18 is the Swiss claim corresponding to the claim 3 compounds:

18 Use according to claim 16 wherein the compound is named (S)-3-(aminomethyl)-5-methylhexanoic acid and 3-aminomethyl-5-methyl-hexanoic acid.

21 Claim 31 is an omnibus claim:

31 A method for treating pain, substantially as herein described with reference to one or more of the examples but excluding comparative examples.

22 Claim 32 is another omnibus claim:

32 Use of a compound of formula I or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt diastereomer or an enantiomer thereof wherein

R1 is a straight or branched alkyl of from 1 to 6 carbon atoms, phenyl, or cycloalkyl of from 3 to 6 carbon atoms;

R2 is hydrogen or methyl; and

R3 is hydrogen, methyl, or carboxyl, substantially as herein described with reference to one or more of the examples and the accompanying figures.

23 We discuss the specification in greater detail below. For present purposes we note that, although not stated in terms, the claims are directed to the treatment of pain in mammals, including humans. The specification describes tests performed on rats to demonstrate the comparative efficacy of the claimed compounds in treating pain.

The primary judgment

24 The primary judge’s reasons dealing with the respondent’s case on insufficiency and false suggestion, and the appellants’ case on infringement, were published on 21 October 2016 as Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Company LLC (No 2) [2016] FCA 1238. In the following summary, our pinpoint references are to those reasons. The notice of cross-appeal refers to these reasons as “the October reasons”.

Sufficiency

25 At [241]-[242], the primary judge found that, although the claims refer to mammals rather than humans, and the various tests discussed in the specification relate to experiments on rats, the invention is primarily directed to the treatment of pain in humans. His Honour described the method claims as methods of treating pain, or different types of pain, in all kinds of mammals including, in particular, humans.

26 At [237], the primary judge noted the test for sufficiency of description articulated in Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Limited [2001] HCA 8; (2001) 207 CLR 1 (Kimberly-Clark) at [25]:

The question is, will the disclosure enable the addressee of the specification to produce something within each claim without new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty?

27 Based on the reasoning in Tramanco Pty Ltd v BPW Transpec Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 23; (2014) 105 IPR 18 (Tramanco) at [207], the primary judge held (at [247]) that the description required by s 40(2)(a) in the present case must enable the person skilled in the art to perform the invention in relation to humans:

In my view, s 40(2)(a) requires that the Patent in this case enable the skilled addressee to perform the claimed invention in relation to humans without new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty. It is only by requiring this degree of enablement that the patentee could be sensibly understood to have given consideration for the grant of a patent which the skilled addressee would understand to be essentially directed to the treatment of pain in humans.

28 In putting the matter this way, it is apparent that the primary judge picked up the test in Kimberly-Clark at [25].

29 In essence, the respondent’s case at trial was that the specification does not describe any safe and effective doses, and dosage regimes, which the person skilled in the art could utilise for the purpose of treating a human patient in need of pain treatment: see, in this regard, [250] of the primary judge’s reasons, quoted at [72] below.

30 The respondent submitted that, given the limited information disclosed in the specification, the person skilled in the art could not simply work within the broad dose range provided with respect to rats and titrate the dose for humans. The respondent submitted that, at the application date, pregabalin was a new chemical entity. So far as the person skilled in the art was concerned, pregabalin had not been tested in humans. The respondent’s case was that, before pregabalin could be administered to a human in need of pain treatment, it would be necessary to undertake further research and study to obtain an understanding of the safety and toxicity profile of the drug. According to the respondent, this would impose an “undue burden” on the person skilled in the art who was seeking to use the claimed methods of treatment.

31 At [259], after discussing Valensi v British Radio Corporation [1973] 90 RPC 337 (Valensi); No-Fume Ltd v Frank Pitchford & Co Ltd (1935) 52 RPC 231 (No-Fume) and Samuel Taylor Pty Ltd v SA Brush Co Ltd [1950] HCA 44; (1950) 83 CLR 617, the primary judge concluded:

The description of the invention will not be insufficient merely because the skilled addressee is expected to apply considerable skill, effort and resources to make it work. If the steps required to be taken to work the invention are readily apparent to the notional skilled addressee, and they are standard or routine steps within the competence of the notional skilled addressee, then the test for sufficiency will be satisfied.

32 Here, the primary judge adopted the notion of “routine” discussed by Heerey J in Eli Lilly and Company v Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals [2005] FCA 67; (2005) 64 IPR 506 (Eli Lilly) at [193]:

It would be necessary to test for oral bioavailability, toxicity and effectiveness, but the evidence shows that while these steps call for skill, they are essentially routine for those skilled in this area. The term routine here (and in other contexts in this case) is not used as a synonym for simple and easy. In the present case the hypothetical skilled workers at the hypothetical workbench are persons holding academic qualifications at the Ph D level together with practical experience. It would not be necessary to employ such persons unless the task they had to perform was a difficult one. Yet this does not of itself mean that the patent could not be worked without further invention.

33 At [264], the primary judge detailed the standard steps that must be followed to obtain regulatory approval permitting the clinical use of a new drug. His Honour noted that, before a new drug can be registered and approved for clinical use, it must first be evaluated for safety and efficacy and that, to a large extent, this process is determined by practices and procedures prescribed by regulatory authorities. His Honour discussed the nature of pre-clinical studies, and Phase 1, 2 and 3 studies. At [266] and [269], his Honour accepted that the steps required to take a new drug from discovery to approval are complex, time-consuming and expensive. However, at [269] his Honour also reasoned that it did not follow that these steps are not routine for the person skilled in the art or that the work required to be performed to obtain regulatory approval cannot be performed without the need for invention.

34 In expressing this qualification, his Honour accepted the possibility that problems might arise in the course of carrying out these steps that might require a creative or inventive solution, which the person skilled in the art cannot deliver. But, at [270] his Honour noted that, in the present case, there was no evidence to indicate that the person skilled in the art would be confronted with any such problem when working with pregabalin.

35 Importantly in this connection, the primary judge said (at [271]):

There are two further points to make. First, it must be assumed, for the purpose of deciding whether the work required to perform an invention imposes some impermissible measure of difficulty, that the notional skilled team will possess the will and resources necessary to perform the invention. There are many inventions that are complex, time consuming and expensive to perform, but it does not follow that the description of the invention is therefore insufficient. Secondly, it is necessary to distinguish between work required to check or test an invention or obtain regulatory approval for its use, and work that is necessary to perform the invention. As the Full Court observed in Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd (2006) 154 FCR 31 at [108] in relation to pharmaceutical patents (though not in the context of sufficiency) “… it is a matter of notoriety that prolonged testing for the purpose of regulatory approval must occur between the stage of patent application and commercial marketing.”

36 The primary judge turned to consider various reports of studies (reproduced in Exhibit 1) conducted by or for the appellants. These reports recorded the research and experimental work undertaken between July 1992 and December 2000 in relation to the use of pregabalin as a possible treatment for seizures or pain. At [275], his Honour noted that there was almost no written or oral evidence specifically directed to these reports, with the exception of one document that had been published and which had been discussed by his Honour in an earlier section of the reasons.

37 The respondent relied on these documents to support a submission that the person skilled in the art would be confronted with an “undue burden” or, in the language of Kimberly-Clark, a need for new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty when performing the invention.

38 At [282], the primary judge observed that the law on sufficiency of description is concerned with “enablement” of the invention. As such, the question is not whether the patentee could have supplied the person skilled in the art with more information than it did, but whether the person skilled in the art has been supplied with enough information to enable the working of the invention.

39 In discussing some of the reports on which the respondent placed particular reliance, the primary judge observed (at [283]):

… The suggestion seemed to be, though it was never put in these terms, that I should conclude from this report and a few other animal studies in which some adverse events were noted, that pre-clinical work undertaken by [the appellants] would have presented the skilled addressee with problems that would be difficult for the notional skilled team to resolve and that would be beyond the competence of the notional skilled team engaged in routine testing. However, no such proposition was put to any expert witness and any submission to that effect based upon those particular reports, or any others included in Ex 1, cannot be sustained on the evidence.

40 At [284], the primary judge concluded that the respondent’s challenge to the validity of the patent on this ground failed.

False suggestion

41 The respondent’s case was that, by certain express statements made at page 2, lines 12 to 13 (the identification of the two “more preferred compounds”); page 2a, lines 8 to 12 (a heading relating to Figure 1); page 7, lines 28 to 29 (a heading relating to a Rat Formalin Paw Test); and page 8, lines 11 to 13 (a statement concerning the efficacy of the 3-amino compound in the Rat Formalin Paw Test) of the specification, and by reference to the fact that each claim of the patent encompasses the 3-amino compound as a racemate, a false suggestion or misrepresentation was made, impliedly, that the 3-amino compound as a racemate had been tested for the treatment of pain, as described and claimed. We pause to note that it was common ground that the 3-amino compound in its racemic form had not been so tested.

42 At [156], the primary judge found that the complete specification did convey a false suggestion that the inventor had tested the racemate and that the results of those tests were reported in Figures 1e and f in the specification. These figures refer to a compound designated as PD 144550. Although PD 144550 had been defined in the scientific literature as the (R)-enantiomer of the 3-amino compound, the primary judge was not satisfied that the person skilled in the art would have known that fact. The effect of the primary judge’s finding is that, on reading the specification, the person skilled in the art would understand that PD 144550 is the 3-amino compound as a racemate and that it was in this form that the 3-amino compound had been tested, not as the (R)-enantiomer.

43 Despite this finding, the primary judge was not satisfied on the evidence before him that the false suggestion materially contributed to the Commissioner’s decision to grant the patent.

44 In this connection, the primary judge found (at [157]) that it was unlikely that the Commissioner gave any consideration to the test results except in so far as they indicated that the most preferred embodiment, the (S)-3-amino compound, may be effective in the treatment of pain.

45 At [158], the primary judge held:

The main focus of the inventor’s testing as reported in the patent application was on the (S)-enantiomer. The (S)-enantiomer was used in all of the reported tests. PD-14450 was used in the tests reported in Figures 1e and 1f, but not in any of the other reported tests. However, there is nothing in the evidence to suggest that the Commissioner’s decision to grant the Patent was influenced in any way by the false suggestion that PD-144550 was the racemate. From the Commissioner’s perspective, whether it was the racemate, the (R)-enantiomer or some other less preferred compound of Formula I that was tested, would seem to be of no moment. In the circumstances, I am not satisfied that the false suggestion was a material inducing factor that led to the grant of the Patent.

Infringement

46 Section 13 of the Act provides:

(1) Subject to this Act, a patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to exploit the invention.

(2) The exclusive rights are personal property and are capable of assignment and of devolution by law.

(3) A patent has effect throughout the patent area.

47 The meaning of “exploit” is provided in the Dictionary in Sch 1 to the Act:

"exploit ", in relation to an invention, includes:

(a) where the invention is a product—make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things; or

(b) where the invention is a method or process—use the method or process or do any act mentioned in paragraph (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

48 It was common ground that a Swiss claim is properly characterised as a “method or process” within the meaning of para (b) of the definition: Otsuka at [120].

49 The respondent contended that it did not threaten to infringe the Swiss claims because the medicaments it intended to import and supply were made by a third party, outside the patent area. The respondent’s contention was based on reading geographical limitations into the definition of “exploit”—in particular, reading into para (b) the requirement that the method or process must be practised in the patent area.

50 At [296], the primary judge held that there was no reason to read down the definition of “exploit” to found a territorial limitation. Such a limitation was imposed by s 13 of the Act.

51 At [297], the primary judge reasoned that, in light of s 13, the question was whether one of the described acts constituting an “exploitation” was performed (or, in the instant case, threatened to be performed) in the patent area. So viewed, the relevant act of infringement was not the use of the method outside the patent area but the exploitation, by importation and sale in the patent area, of a product made by the patented method. The respondent’s products were such products.

52 At [298], the primary judge considered his approach to the definition of “exploit” to be somewhat different to that taken by Lindgren J in Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008] FCA 559; (2008) 76 IPR 618 (Alphapharm) at [691]-[694]. We note, however, that, on either approach, the respondent’s case in this regard would fail.

Sufficiency

The specification

53 The specification discloses that the compounds of the invention are known to be useful in antiseizure therapy for central nervous system disorders and that it has been suggested that they can be used as antidepressants, anxiolytics and antipsychotics. In this latter regard, the specification cites patent specifications WO 92/09560 and WO 93/23383, which the parties agree were thereby incorporated by reference. As we have noted, the novelty of the present invention lies in using the compounds of Formula I for a new therapeutic use—the treatment of pain in mammals.

54 In this connection, the specification describes two aspects of the invention. The first is a method for treating pain comprising administering a therapeutically effective amount of the compounds. The second is the use of the compounds for the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of pain. After disclosing Formula I, the specification identifies the preferred compounds and more preferred compounds, noted at [16] and [18] above.

55 The specification provides a brief description of Figures 1 to 6, which are graphical representations of the results of tests performed on rats to demonstrate the comparative efficacy of the compounds in treating pain.

56 The tests are identified as:

Effect of Gabapentin (1-(aminomethyl)-cyclohexaneacetic acid), CI-1008 ((S)-3-aminomethyl)-5-methylhexanoic acid), and 3-aminomethyl-5-methyl-hexaoic acid in the Rat Paw Formalin Test.

Effect of Gabapentin and CI-1008 on Carrageenin-Induced Mechanical Hyperalgesia.

Effect of Gabapentin and CI-1008 on Carrageenin-Induced Thermal Hyperalgesia.

Effect of (a) Morphine, (b) Gabapentin, and (c) S-(+)-3-Isobutylgaba on Thermal Hyperalgesia in the Rat Postoperative Pain Model.

Effect of (a) Morphine, (b) Gabapentin, and (c) S-(+)-3-Isobutylgaba on Tactile Allodynia in the Rat Postoperative Pain Model.

Effect of S-(+)-3-Isobutylgaba on the Maintenance of (a) Thermal Hyperalgesia and (b) Tactile Allodynia in the Rat Postoperative Pain Model.

57 In these descriptions, pregabalin is referred to as “CI-1008”, “S-(+)-3-isobutylgaba” or “(S)-(+)-IBG”. The 3-amino compound is referred to as “3-Isobutylgaba” or “PD-144550”. As we have noted, it was common ground before the primary judge that PD-144550 is actually the (R)-enantiomer of the 3-amino compound, and not the 3-amino compound as a racemate.

58 As the primary judge observed at [158], pregabalin was used in all of the reported tests. PD-144550 was used in the tests reported in Figures 1e and 1f, but not in any of the other reported tests. Perhaps to state the obvious, the 3-amino compound as a racemate, and each of its enantiomers, separately fall within the range of compounds defined by Formula I.

59 In this connection, the specification makes clear that the compounds of the invention can contain one or several asymmetric carbon atoms and that the invention includes the individual enantiomers of such compounds as well as mixtures thereof (i.e., such compounds in their racemic form). The specification discloses that the enantiomers can be prepared or isolated by methods already well-known in the art.

60 The specification proceeds to give a detailed description of the invention. It refers to various pain conditions which, the specification says, are known to be poorly treated by currently marketed analgesics or due to insufficient efficacy or limiting side effects. A number of these are plainly directed to the human condition:

The instant invention is a method of using a compound of Formula I above as an analgesic in the treatment of pain as listed above. Pain such as inflammatory pain, neuropathic pain, cancer pain, postoperative pain, and idiopathic pain which is pain of unknown origin, for example, phantom limb pain are included especially. Neuropathic pain is caused by injury or infection of peripheral sensory nerves. It includes, but is not limited to pain from peripheral nerve trauma, herpes virus infection, diabetes mellitus, causalgia, plexus avulsion, neuroma, limb amputation, and vasculitis. Neuropathic pain is also caused by nerve damage from chronic alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hypothyroidism, uremia, or vitamin deficiencies. Neuropathic pain includes, but is not limited to pain caused by nerve injury such as, for example, the pain diabetics suffer from.

The conditions listed above are known to be poorly treated by currently marketed analgesics such as narcotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) due to insufficient efficacy or limiting side effects.

61 The specification explains some of the terms used in Formula I. It then describes how the compounds can be formed:

The compounds of the present invention may form pharmaceutically acceptable salts with both organic and inorganic acids or bases. For example, the acid addition salts of the basic compounds are prepared either by dissolving the free base in aqueous or aqueous alcohol solution or other suitable solvents containing the appropriate acid and isolating the salt by evaporating the solution. Examples of pharmaceutically acceptable salts are hydrochlorides, hydrobromides, hydrosulfates, etc. as well as sodium, potassium, and magnesium, etc. salts.

62 The specification includes a discussion on the method for the formation of the 3-alkyl-4-aminobutanoic acids at page 6, line 11 to page 7, line 3.

63 The specification then states:

The compounds made by the synthetic methods can be used as pharmaceutical compositions as agent in the treatment of pain when an effective amount of a compound of the Formula I, together with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier is used. The pharmaceutical can be used in a method for treating such disorders in mammals, including human, suffering therefrom by administering to such mammals an effective amount of the compound as described above in unit dosage form.

64 The specification discusses dosage forms:

The pharmaceutical compound, made in accordance with the present invention, can be prepared and administered in a wide variety of dosage forms by either oral or parenteral routes of administration. For example, these pharmaceutical compositions can be made in inert, pharmaceutically acceptable carriers which are either solid or liquid. Solid form preparations include powders, tablets, dispersible granules, capsules, cachets, and suppositories. Other solid and liquid form preparations could be made in accordance with known methods of the art and administered by the oral route in an appropriate formulation, or by a parenteral route such as intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection as a liquid formulation.

The quantity of active compound in a unit dose of preparation may be varied or adjusted from 1 mg to about 300 mg/kg daily, based on an average 70-kg patient. A daily dose range of about 1 mg to about 50 mg/kg is preferred. The dosages, however, may be varied depending upon the requirement with a patient, the severity of the condition being treated, and the compound being employed. Determination of the proper dosage for particular situations is within the skill of the art.

65 By its reference to patients and the identification of an average patient weight of 70kg, this part of the description appears to be directed to the administration of the compounds to humans. It shows a broad dosage range and a preferred dosage range. It also teaches that the compounds can be administered in a wide variety of dosage forms. WO 93/23383 (United States Serial Number 886,080 filed on 20 May 1992) is incorporated in the specification by reference: see page 1, lines 14 to 15. It discloses a usable formulation of pregabalin for oral, subcutaneous or IV administration.

66 The specification then proceeds to discuss in some detail the tests that were carried out on rats.

The grounds of the cross-appeal

67 Grounds 1 to 5 of the notice of cross-appeal concern the primary judge’s findings on sufficiency of description. There are aspects of these grounds which, as developed in submissions, overlap in theme and content. Ground 6 is also directed to that subject, but is no longer pressed.

68 Grounds 1 to 5 are:

1. The primary judge erred in finding that “[t]he description of the invention will not be insufficient merely because the skilled addressee is expected to apply considerable skill, effort and resources” and that the test for sufficiency will be satisfied if “the steps required to be taken to work the invention are readily apparent to the notional skilled addressee, and they are standard or routine steps within the competence of the notional skilled addressee” (at [259] of the October reasons). The primary judge should have found that the need to undertake "complex, time-consuming and expensive steps” (cf [266] of the October reasons), even if those steps are apparent to, and within the competence of, the skilled addressee, does not satisfy the test for sufficiency.

2. The primary judge erred in finding that the dose range described in the Patent was 1mg/kg to 300mg/kg (with a preferred range of 1mg/kg to 50mg/kg) (at [112], [113], [149] of the October reasons) and should have found that the dose range commenced at 1mg.

3. Having found that:

(a) The preferred dose range specified in the Patent was 1mg/kg to 50mg/kg (for a typical 70kg patient) (ie, 70mg to 3.5kg) (at [149] of the October reasons);

(b) the Patent does not refer to any safety or efficacy testing of the claimed compounds of the invention in humans (at [128] of the October reasons);

(c) before a drug can be approved for clinical use, it must first be evaluated for safety and effectiveness (at [264] of the October reasons); and

(d) the steps required to take the information in the Patent and perform the claimed methods would involve complex, time consuming and expensive work (at [266] of the October reasons),

the primary judge erred in finding that the notional skilled team would be able to perform the invention disclosed in the specification without the need for “invention” (at [269] of the October reasons) and therefore that the description of the invention in the Patent was sufficient. In making this finding, the primary judge also erred in failing to apply the principle that the need for “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” (cf [255] of the October reasons) means the test for sufficiency is not satisfied.

4. The primary judge erred in finding that the documents contained in Exhibit 1 (which referred to pre–clinical work undertaken by Pfizer in relation to pregabalin) did not support the proposition that the notional skilled team would be confronted with an “undue burden” or a need for “new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” (at [270] and [283] of the October reasons) and failed to give sufficient weight to, evidence in Exhibit 1 that indicated that Pfizer had faced significant obstacles, including with respect to dosing and dose regimen, at the pre-clinical stage.

5. The primary judge erred in considering that the information contained in Exhibit 1 required explanation by an expert witness (at [283] of the October reasons).

The respondent’s submissions

69 In support of Ground 1 of the cross-appeal, the respondent submitted that the present invention stands in contrast to an invention for a compound which has a suggested first therapeutic use. In that case, the respondent submitted, the specification need only “enable the compound”; it need not “enable the use”. However, the respondent submitted, where the invention is for a second or subsequent medical use of a compound, a different or more stringent “degree of enablement” is required. According to the respondent, the specification must give a sufficient description of a safe and effective treatment that involves the use of the compound.

70 The respondent submitted that identical considerations apply to inventions defined by Swiss claims: the specification must describe, at least, the identity and amount of the active pharmaceutical ingredient and sufficient information regarding the circumstances of administration, so that the person skilled in the art can know that the medicament can be administered to a patient for the treatment of pain, with an informed expectation that it is safe and efficacious.

71 According to the respondent, the primary judge’s error lay in setting the bar too low in this regard, in light of his Honour’s findings that an invention will not be insufficiently described merely because the person skilled in the art is expected to apply considerable skill, effort and resources or because complex, time-consuming and expensive steps might be required to work the invention.

72 To this end, the respondent directed attention to [250] of the primary judge’s reasons which, it said, captured the limited extent of the specification’s description of the invention:

250 In essence, Apotex submitted that the Patent does not describe any safe and effective doses and dosage regimes which the skilled addressee may utilise for the purpose of treating a patient in need of treatment for pain. In support of its submission, Apotex made the following points:

• The Patent does not describe any specific dose for the (S)-enantiomer or any other compound. The description of doses at page 7, lines 21 to 27 refer to a preferred dose of about 1mg/kg to about 300 mg/kg based on the average 70 kg patient, but these statements are not made in relation to any particular compound.

• The Patent does not include any information in relation to solubility, bioavailability or safety. The experimental work referred to in the Patent all relate to in vivo tests on rats treated with (inter alia) the (S)-enantiomer. There is no disclosure of any pre-clinical pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic or toxicology tests, nor any Phase 1, 2 or 3 trials.

• The fact that pregabalin is now known to be safe and efficacious is irrelevant because the sufficiency of the description is to be assessed on the basis of what is disclosed in the specification as it would be read and understood by the skilled addressee as at the application date. At that date, the compounds claimed in the Patent were new chemical entities that were not the subject of any regulatory approval and lacking any known safety and toxicity profile.

73 We note the primary judge’s identification of the lower limit of the preferred dosage range as 1 mg/kg. This followed from his Honour’s resolution (at [149]) of a contested point of construction, which was whether the specification’s reference to “1 mg” at page 7, lines 22 to 23 would be understood by the person skilled in the art as meaning “1 mg/kg” or “1 mg” simpliciter. The primary judge found that “1 mg/kg” would be understood. On appeal, the respondent submitted that this finding was an error: Ground 2. The respondent accepted that success on this ground was not critical to its cross-appeal. The point it sought to make was that, if “1 mg” is the correct construction, then the specification reveals an even broader dosage range which rendered its description of the invention even less useful to the person skilled in the art.

74 It is convenient that we record now our conclusion that we are not persuaded that the primary judge erred in his construction of this part of the specification. It was open to his Honour to find that the person skilled in the art would understand the reference to “1 mg” to be in the context of a weight-based dosage calculation and thus interpret the reference as “1 mg/kg”.

75 In the cross-appeal, the respondent submitted that the description in the specification does not rise above the suggestion that the compounds of the invention might work for pain, as illustrated by the rat experiments. The respondent argued that this left too much work to be done by the person skilled in the art to develop “this mere idea into a method with the requisite safety and efficacy to be a method or medicament for treating pain”.

76 The respondent did not identify what would be a sufficient description of the “requisite safety and efficacy” in the present case. It eschewed the notion that a sufficient description could only be satisfied by information of the kind that would secure regulatory approval for the administration of the compounds in the treatment of pain, even though it advanced the Exhibit 1 documents as an illustration of the work involved in bringing the invention to clinical use in a regulated environment. But it did not seek to bridge the gap between information of this kind (which on its own case was not necessary to establish sufficiency of description) and the alleged insufficiency of the description in the specification, beyond the criticisms set out in the primary judge’s summary quoted at [72] above. The respondent submitted that it was not necessary for it to do more than show that the description in the specification was insufficient; it was not incumbent on it to say what would be a sufficient description.

77 In advancing this and its other grounds, the respondent referred to the test in Kimberly-Clark as no more than “a commonly applied test for sufficiency”. It posited a broader test: an invention cannot be fully described for the purposes of s 40(2)(a) of the Act if an “undue burden” is placed on the person skilled in the art who wishes to use the method, or make the medicament, claimed.

78 The broad themes of Ground 1 resonate in Grounds 3 and 4.

79 In Ground 3, the respondent relied on various findings of fact made by the primary judge, including findings relied on for Ground 1, to argue that the primary judge erred by concluding that the description of the invention in the specification was sufficient. Additionally, the respondent argued that the primary judge failed to apply the principle that the need for “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” meant that the test for sufficiency was not satisfied. In putting the matter this way, the respondent was referring to the second limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark.

80 We draw attention to the fact that Ground 3 also pleads that the primary judge erred in finding that the person skilled in the art would be able to perform the invention “disclosed” in the specification without the need for “invention”. A submission to this effect was advanced in the respondent’s written submissions. In the course of oral argument, the respondent made clear that it no longer relies on this allegation, which was directed to the first limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark.

81 We note that the last fact referred to by the respondent in Ground 3—that the steps required to take the information in the specification and perform the claimed methods would involve complex, time-consuming and expensive work—does not accurately state the primary judge’s finding at [266], which was concerned more generally with the steps required to take a new drug from discovery to regulatory approval. Nevertheless, at [267]-[269], the primary judge accepted that similar steps would be required to use the compounds of the invention to treat pain in humans in clinical trials or to treat pain in humans using a regulatory agency-approved product.

82 In dealing with Ground 3, the respondent criticised the primary judge’s reliance (at [271]) on Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd [2006] FCAFC 91; (2006) 154 FCR 31 (Merck) to draw a distinction between, on the one hand, work required to check or test an invention or obtain regulatory approval for its use and, on the other, work necessary to perform the invention. In this connection, the respondent endeavoured to distinguish Merck by reference to the fact that, according to the respondent, the specification in Merck contained significantly more information about the methods of treatment claimed therein, including the preferred dosing schedule and the pharmaceutically effective amount of the drug (alendronate) to be administered. The respondent contrasted the state of affairs in Merck with the present case, submitting that, to perform the claimed invention in the present case, the person skilled in the art is left with significantly more work to do than merely checking or testing the invention. The respondent submitted that, in the present case, the person skilled in the art is left to identify a safe and non-toxic dose of pregabalin which is therapeutically effective in treating pain. The respondent submitted that the identification of such a dose or doses lies at the heart of the invention, and the specification provides very little guidance as to what such doses might be. The respondent also pointed to evidence to the effect that the person skilled in the art could not pick a safe dose for a human from the dosage range disclosed in the specification.

83 With respect to Ground 4, the respondent relied on the pre-clinical and clinical studies in the Exhibit 1 documents as representative of the body of work, or kinds of work, that the person skilled in the art, armed with the information in the specification and the common general knowledge, would be at least required to undertake in order to perform the invention. According to the respondent, this work is the exemplification of “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty”. Once again, this is a reference to the second limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark.

84 As we have noted, at [275] the primary judge concluded that there was almost no written or oral evidence specifically directed to the documents and that the respondent appeared to have assumed that the documents would speak for themselves. The respondent submitted that the primary judge’s comment concerning its assumption that the documents would speak for themselves was tantamount to a finding that the information contained in Exhibit 1 required explanation by an expert witness. This, the respondent said, was an error: Ground 5. We do not think that Ground 5 of the cross-appeal really engages with the purport of his Honour’s comment, which was not directed so much to comprehensibility as to the need to understand the documents in context. We think this is clear from [283] of his Honour’s reasons, which we have quoted at [39] above. Ground 5 cannot be sustained.

85 In any event, the primary judge accepted (at [276]) that the documents broadly reflected the course of research work usually undertaken for the purpose of obtaining regulatory approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration for the clinical use of a new drug.

86 In developing Ground 4 in oral submissions, the respondent took us to a number of the Exhibit 1 documents. The respondent’s written submissions also summarised the nature of the work recorded in these documents.

87 In its written submissions, the respondent submitted that the Exhibit 1 documents show that, in the course of obtaining regulatory approval for the pregabalin products, the appellants in fact encountered significant hurdles or unexpected results which they were required to overcome.

88 In the context of Ground 4, this submission was advanced to illustrate two matters. The first matter was that, left with the description in the specification, an “undue burden” was placed on the person skilled in the art seeking to perform the invention. The second matter was that the work reported in the Exhibit 1 documents reflected the need for “new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty”.

89 In expressing Ground 4 in this way, the respondent was distinguishing between the test in Kimberly-Clark and the broader test of “undue burden” it was advocating as a general test of insufficiency. However, in the course of oral submissions, the respondent qualified its reliance on Ground 4. Consistently with its position in relation to Ground 3, the respondent said that it no longer relied on the allegation in Ground 4 that the Exhibit 1 documents showed that the appellants were confronted with work of a kind that represented “new inventions or additions”. Thus, the respondent confined this part of Ground 4 to the second limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark and its posited test of “undue burden”: Transcript p 90; see also, Transcript p 17.

90 In developing Ground 4, the respondent submitted that the primary judge had erred by treating the test in Kimberly-Clark as a statute. It submitted that, by so doing, the primary judge ignored “the correct principle” which was that a patent specification may be “insufficient in its description” if the person skilled in the art was faced with an “undue burden”. The respondent made clear that the notion of an “undue burden” was wider than the need for “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty”.

91 The respondent stressed that it was not contending that, in terms of description, s 40(2)(a) requires proof of the matters stated in the specification, or, once again, that the information required to satisfy s 40(2)(a) equates with the information required for regulatory approval. It explained its case as follows:

The relevance of the regulatory framework is that it reflects the ethical environment within which the skilled addressee (in particular, the clinician) operates. For any method comprising the administration of a “therapeutically effective amount” of a compound (as the claims of the Patent require), and putting aside any question of regulation, the clinician must have sufficient confidence in the safety and efficacy of the treatment to be used. As the difficulties encountered by Pfizer in the course of obtaining regulatory approval for pregabalin demonstrated, the information in the Patent falls well short of what would be required to provide such confidence.

92 The respondent submitted that, at [270] of the reasons, the primary judge dismissed its case on insufficiency on the basis that there was no evidence that the person skilled in the art would be confronted with problems that called for a creative or inventive solution. Thus, the respondent submitted, the primary judge ignored the consideration of “undue burden”.

93 In this connection, the respondent submitted that, even though the requirements and procedures involved in determining doses and formulations are to some extent standard, this does not mean that the process of going “from patent to patient” is routine. The respondent submitted that this process is not straightforward or linear, but requires a substantial amount of work on the part of the person skilled in the art. The respondent submitted that the work involved was of a different order from “checking” or “testing”. Here, the respondent relied on Jagot J’s observations in Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC [2016] FCA 169; (2016) 117 IPR 252 at [438]:

…if original research is required to be able to produce something within a claim then it would raise a real question whether the qualification that there be no need for “new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” is satisfied…

and:

…in the context of sufficiency if ingenuity is required to be brought to bear to make something within a claim it would raise the question whether a new invention has been involved which would be a disqualifying factor.

94 Finally, the respondent submitted that the primary judge’s reliance on Heerey J’s observations in Eli Lilly (quoted at [32] above) was misplaced in that the disclosures contained in the specification in Eli Lilly were “vastly different” to the information disclosed in the specification in suit. The respondent pointed to the fact that the specification in Eli Lilly referred to in vitro tests and toxicity tests in animals (rat, dog and mouse) and that human trials were referred to, with a preferred dosage regimen for a typical male being given. The respondent also suggested that Heerey J’s reference to the need to test for oral bioavailability, toxicity and effectiveness was, on the facts of that case, more akin to work required to check or test an invention, rather than work necessary to perform the invention.

The appellants’ contentions

95 Apart from addressing the respondent’s submissions, the appellants advanced two contentions.

96 First, the appellants contended that, even though the primary judge was correct to conclude that the respondent’s challenge failed in relation to the sufficiency of the description of the invention in relation to the treatment of humans, the primary judge should have found that the requirements of s 40(2)(a) of the Act were satisfied because the specification enables the person skilled in the art to perform the invention in rats without new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty.

97 The essential point of this contention is that the test for sufficiency of description articulated in Kimberly-Clark requires only enablement of one embodiment of the invention within each claim. Relatedly, the appellants contended that the obiter observations in Tramanco, on which the primary judge relied at [244]-[247], have no application to the invention claimed in the present case.

98 Secondly, the appellants contended that it is unnecessary to consider the work required to be undertaken to prove safety and efficacy for regulatory and marketing approval purposes because any difficulty or effort involved in the work undertaken to obtain regulatory approval is either irrelevant or immaterial to a consideration of the requirements of s 40(2)(a), which is concerned with the capacity of the person skilled in the art to practise the invention. The appellants did not dispute that a clinician would ordinarily want to see evidence, beyond the description in a patent specification, that a treatment works. But, they argued, a patent specification for an invention such as the present is not required to persuade a clinician to practise the invention. It is only required to enable the person skilled in the art to do so in the sense discussed in Kimberly-Clark.

Analysis

99 We commence our consideration of this topic with some observations concerning the respondent’s deployment of the notion of “undue burden”.

100 So far as we are aware, the expression “undue burden” has not entered the lexicon of Australian patent law with respect to s 40(2)(a) of the Act, which relevantly requires that the complete specification of a patent application describe the invention fully. Caution must be exercised when considering what is intended to be conveyed by “undue burden” in this context.

101 The expression derives from the case law of the Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office: see, for example, T435/91, UNILVER/Detergents [1995] EPOR 314 at [2.2]; T694/92, Mycogen/Modifying plant cells [1998] EPOR 114 at [5]; T1743/06, Ineos/Amorphous silica (unreported). This case law concerns the manner in which Art 83 of the European Patent Convention (the EPC) is to be applied. Article 83 provides:

The European patent application shall disclose the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art.

102 The expression appears to be an elaboration of what we would understand to be the settled position of the Boards of Appeal as expressed in T226/85, UNILVER/Stable bleaches [1989] EPOR 18 at [8]:

Even though a reasonable amount of trial and error is permissible when it comes to the sufficiency of disclosure in an unexplored field or—as it is in this case—where there are many technical difficulties, there must then be available adequate instructions in the specification or on the basis of common general knowledge which would lead the skilled person necessarily and directly towards success through the evaluation of initial failures or through an acceptable statistical expectation rate in case of random experiments. In the present appeal the sensitivity or inherent instability of the composition, or other unexplained circumstances are such that the skilled person can only reproduce the invention in a number of instances with some luck, if at all, in view of the unknown character of reasons which cause failure. For this reason, the patent is invalid in its entirety for not complying with the requirements of Article 83 EPC .

103 The corresponding provision of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) (the 1977 Act) is s 14(3):

The specification of an application shall disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the art.

104 Further, s 72(1)(c) of the 1977 Act provides for revocation of a patent on the ground that:

…the specification of the patent does not disclose the invention clearly enough and completely enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the art; …

105 In Novartis AG v Johnson & Johnson Medical Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 1039, Jacob LJ said with respect to the latter provision:

The heart of the test is: Can the skilled person readily perform the invention over the whole area claimed without undue burden and without needing inventive skill?

106 It appears that, in saying this, Jacob LJ was paying deference to the statements of principle articulated in the later Boards of Appeal cases, T435/91, T694/92 and T1743/06.

107 Earlier, in Mentor Corporation v Hollister Inc [1991] FSR 557, Aldous J (at 562) described the purport of s 72(1)(c) in the following terms, without using the expression “undue burden”:

The section requires the skilled man to be able to perform the invention, but does not lay down the limits as to the time and energy that the skilled man must spend seeking to perform the invention before it is insufficient. Clearly there must be a limit. The sub-section, by using the words “clearly enough and completely enough”, contemplates that patent specifications need not set out every detail necessary for performance, but can leave the skilled man to use his skill to perform the invention. In so doing he must seek success. He should not be required to carry out any prolonged research, enquiry or experiment. He may need to carry out the ordinary methods of trial and error, which involve no inventive step and generally are necessary in applying the particular discovery to produce a practical result. In each case, it is a question of fact, depending on the nature of the invention, as to whether the steps needed to perform the invention are ordinary steps of trial and error which a skilled man would realise would be necessary and normal to produce a practical result.

108 The reference to “prolonged research, enquiry or experiment” in this passage harkens to the statement made by the Court of Appeal in Valensi at 377 in describing the attributes of the person skilled in the art. In this passage, the Court of Appeal was addressing the extent to which the person skilled in the art can be called upon to exercise that person’s own skill and knowledge in following details in the specification and in correcting errors in it:

We think that the effect of these cases as a whole is to show that the hypothetical addressee is not a person of exceptional skill and knowledge, that he is not to be expected to exercise any invention nor any prolonged research, inquiry or experiment. He must, however, be prepared to display a reasonable degree of skill and common knowledge of the art in making trials and to correct obvious errors in the specification if a means of correcting them can readily be found.

109 Later at 377, the Court of Appeal said:

Further, we are of the opinion that it is not only inventive steps that cannot be required of the addressee. While the addressee must be taken as a person with a will to make the instructions work, he is not to be called upon to make a prolonged study of matters which present some initial difficulty: and, in particular, if there are actual errors in the specification—if the apparatus really will not work without departing from what is described—then, unless both the existence of the error and the way to correct it can quickly be discovered by an addressee of the degree of skill and knowledge which we envisage, the description is insufficient.

110 In Valensi, the Court of Appeal was considering the infringement and validity of claims in a United Kingdom patent relating to television systems for transmitting and receiving pictures in colour. The complete specification was filed in 1939. At that time, the Patent and Designs Act, 1907 (UK) (the 1907 Act) applied. Section 2(2) of that Act provided that:

…A complete specification must particularly describe and ascertain the nature of the invention and the manner in which the same is to be performed.

111 There is nothing in the Court of Appeal’s reasons for judgment which suggest that, when determining the sufficiency of the description of an invention given in a specification filed under the 1907 Act, some notion of “undue burden” was at play. This notion appears to be an expression of the requirements of s 14(3), and the corresponding ground of revocation under s 72(1)(c), of the 1977 Act that has been introduced into United Kingdom case law so that the 1977 Act is applied consistently and harmoniously with the elaboration of European patent law under the EPC. These considerations are foreign to Australian patent law.

112 It is clear that the test in Kimberly-Clark is based on statements of principle made in Valensi and other, earlier United Kingdom cases. So much is clear from the High Court’s reference at [25] to Blanco White, Patents for Inventions, 5th ed (1983), §4-502 (Blanco White) which, in turn, refers to Valensi and R v Arkwright (1785) 1 WPC 64 at 66, Otto v Linford (1882) 46 LT 35 at 41 and No-Fume Ltd at 243, amongst other cases. In that paragraph, Blanco White stated the following “rule”:

To be proper and sufficient, the complete specification as a whole … must in the first place contain such instructions as will enable all those to whom the specification is addressed to produce something within each claim “by following the directions of the specification, without any new inventions or additions of their own” and without “prolonged study of matters which present some initial difficulty”.

113 The law in relation to s 40(2)(a) of the Act is stated authoritatively in Kimberly-Clark. We see no basis on which we could or should depart from the principles that are there stated and explained. In particular, we see no basis on which we could or should depart from the test or “question” which the High Court stated at [25]. The respondent advanced the notion of “undue burden” in the United Kingdom case law as a principle of equal application under s 40(2)(a). This, it seems to us, is really an invitation to expand the scope of operation of s 40(2)(a) in a way not envisaged by the High Court in Kimberly-Clark, by reference to a little-explained and somewhat indeterminate standard. It is also an invitation that runs counter to the High Court’s caution against an uncritical adoption of post-1977 United Kingdom cases on provisions that are, at best, only broadly similar to provisions in our own Act, particularly in relation to the requirements of patent specifications: Lockwood Security Products Pty Limited v Doric Products Pty Limited [2004] HCA 58; (2004) 217 CLR 274 at [63]-[67]. This is an invitation we should decline.

114 We turn, firstly, to Ground 3 of the cross-appeal insofar as it pleads that the primary judge failed to apply the second limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark—whether the disclosure of the specification enables the addressee to produce something within each claim without “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty”.

115 For present purposes we assume that the primary judge was correct in concluding that, in the present case, sufficiency of description necessarily entails the enablement of the invention in respect of the treatment of humans. Proceeding on that assumption, we would accept that if his Honour did fail to consider the second limb of the test then this would constitute an appealable error.

116 In order to consider this question, it is necessary to trace some of the key steps of the primary judge’s analysis of the respondent’s argument at trial. At the risk of some repetition of the matters summarised at [25]-[40] above, those steps are:

At [247], the primary judge specifically identified the very question which the respondent says his Honour should have considered: see [27] above.

At [250]-[252], the primary judge noted the respondent’s identification of deficiencies in the description of the invention in the specification. Two broad areas were identified: first, the failure of the specification to describe a specific dose for the (S)-enantiomer or any other compound; secondly, the failure of the specification to provide information as to solubility, bioavailability or safety in relation to the administration of the Formula I compounds in humans in circumstances where the compounds were new chemical entities that were not then the subject of regulatory approval and had no known safety and toxicity profile in humans.

At [255]-[258], the primary judge explored the meaning of “prolonged study of matters which present some initial difficulty” as used in Kimberly-Clark at [25].

At [257]-[258], the primary judge rejected the appellants’ submission that, in this context, difficulty is not concerned with how hard the work is or how significant the burden of that work may be, but only with difficulties in working the invention that arise from some defect in the way in which the invention is described.

At [258], the primary judge specifically held that the obligation under s 40(2)(a) is not satisfied merely because the working of the invention does not require the person skilled in the art to do something that has never been done before.

At [259], the primary judge observed that the description of the invention will not be insufficient merely because the person skilled in the art is expected to apply considerable skill, effort and resources to make the invention work. His Honour noted that the test for sufficiency will be satisfied if the steps required to be taken would be readily apparent to the person skilled in the art and that those steps would be standard or routine steps within the competence of that person: [31] above.

At [260]-[263] the primary judge discussed Heerey J’s observations in Eli Lilly (whose approach was apparently endorsed by the Full Court on appeal: Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co [2005] FCAFC 224; (2005) 225 ALR 416) that, in the circumstances of that case, testing for oral bioavailability, toxicity and effectiveness were essentially routine for the person skilled in the art.

At [267]-[270], the primary judge discussed the steps that would be necessary to treat pain in humans in clinical trials, and that would be needed using a regulatory agency approved product, given the information in the specification.

At [275]-[281], the primary judge discussed the Ex 1 documents, noting (amongst other things) the respondent’s submission that these documents support its submission that the person skilled in the art would be confronted with an “undue burden” or, in the language of Kimberly-Clark, “new inventions or additions or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” when performing the invention.

117 In the course of this analysis, the primary judge addressed the question whether, in the present case, the person skilled in the art would be required to devise a creative or inventive solution to a problem encountered along the way when seeking to put the invention into practice. At [270], the primary judge found that there was no evidence to indicate that the person skilled in the art would be confronted with such a problem. In the course of submissions in the cross-appeal, the respondent accepted the correctness of this finding: Transcript p 17.

118 Although having dealt with this question, as the primary judge was required to do, we do not accept that his Honour’s analysis stopped at, or was confined to, this particular limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark (i.e., “new inventions or additions”). We think it perfectly clear that the primary judge was also considering the second limb—namely, whether the description of the invention cast upon the person skilled in the art an “undue burden” in the sense of requiring “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty”. We say this for two reasons.

119 First, from the key steps we have summarised above, it is clear that his Honour was continually directing his attention to this limb. For example, not only did his Honour consider what constitutes “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” but, on more than one occasion, his Honour directed his attention to the fact that the work involved in putting the invention into practice may be complex, time-consuming and expensive or may require the person skilled in the art to apply considerable skill, effort and resources to make the invention work. This discussion was in the context of his Honour also being satisfied that, in the present case, the person skilled in the art would not have been confronted with a problem requiring a creative or inventive solution.

120 Secondly, when his Honour was addressing the question of whether the steps required to put the invention into practice were “routine”, he was addressing not simply whether a creative or inventive mind was required to do so but also, necessarily, the very fact that, whether or not a creative or inventive mind was required, those steps had to be carried out. We do not accept that, in considering the character of the steps that might be required to put the invention into practice, his Honour, somehow, put out of mind the need to carry out those steps.

121 The next question is whether there was error in the primary judge’s apparent acceptance that the description in the specification did provide enough information to work the invention in respect of the treatment of pain in humans, even though the person skilled in the art might need to apply considerable skill, effort or resources, or to carry out complex, time-consuming and expensive work, in order to do so. This question really covers Grounds 1 and 4 and the remaining aspects of Ground 3 which, in one way or another, all focus on the amount and scope of work that the person skilled in the art, armed with the description in the specification, would be required to carry out in order to work the invention for that purpose.

122 In considering this question, it is necessary to bear in mind the following matters.

123 First, the invention is the use of certain compounds for the treatment of pain in mammals, including humans. As the appellants submitted, the invention is a broad one directed to the application of known compounds to a new therapeutic use. It is not directed to more specific matters, such as a new and inventive dosage regimen or dosage form for the administration of the compounds in treating pain in, say, humans. The character of the invention is important when considering the nature, scope and extent of the description that will be sufficient to satisfy the requirements of s 40(2)(a). On the primary judge’s findings, once the present invention was disclosed in the specification, it was a matter of routine for the person skilled in the art to administer the compounds to human subjects, bearing in mind the description given: see, in this connection, page 7, lines 11-27 of the specification, quoted at [64] above.

124 Secondly, the respondent does not contend that s 40(2)(a) has not been satisfied in the present case because the specification does not state the best method of performing the invention.

125 Thirdly, the relevant inquiry is: does the specification describe the invention fully? The inquiry is not, as some aspects of the respondent’s submissions suggest (even though the respondent disavowed the suggestion): what information and testing is necessary to be provided in order for the new therapeutic use to be approved by a regulatory agency? The work undertaken to prove the safety and efficacy of a compound for regulatory and marketing approval purposes is not necessarily relevant or material to the determination of whether the requirements of s 40(2)(a) of the Act have been met in a given case. The primary judge correctly recognised this distinction at [271] of the reasons.

126 Relatedly, the primary judge correctly recognised at [282] of the reasons that the issue is not whether the patentee could have supplied the person skilled in the art with more information than it did, but whether it has supplied enough information. As the appellants put the matter in written submissions before us:

The need to produce “new inventions or additions” or to carry out “prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty” may mean that a description is insufficient. The need for time, cost and detailed work will not; at least where, as here, the work involved is of a routine and conventional kind.

127 The respondent’s contention was that, if too much work is involved, the invention has not been fully described and s 40(2)(a) has not been satisfied. However, as we have noted, the respondent did not venture to say what description would be sufficient to satisfy the statutory requirement.

128 Fourthly, there is a difference between whether a clinician would choose to perform the invention and whether the person skilled in the art could perform the invention based on the description in the specification. The primary judge recorded this argument at [254] of the reasons.

129 In this connection, we accept that the appellants raise a valid point of distinction which is relevant to the respondent’s criticism that the specification does not contain, for example, specific dosages or a safety and toxicity profile in respect of the use of the compounds for the treatment of pain in human subjects, and that a clinician would not use the compounds for this purpose without this information. Whilst the primary judge appears to have accepted that, from the clinician’s perspective, this information would be necessary—with the consequence that further work would need to be carried out in this regard before the compound would be put to use in clinical practice—his Honour was not satisfied that this meant that the requirements of s 40(2)(a) of the Act had not been met. This was because, in the circumstances of the present case, the work required to put the invention into practice was of a routine (that is, non-inventive) nature for the person skilled in the art (now accepted on appeal), even though the work to be undertaken would require considerable skill, effort and resources or be complex, time-consuming and expensive.

130 This illustrates the difference between the “would” and the “could” in the appellants’ submission. On the primary judge’s findings, the person skilled in the art could carry out the invention in respect of human subjects on the basis of the description in the specification, but the clinician would not do so without precise dosages and the safety and efficacy of the compounds first being established by tests of the kind required to achieve regulatory approval for administration of the compounds to treat pain in those subjects. We observe that enablement under s 40(2)(a) is concerned with the “could”, not the “would”. This is the question which the test in Kimberly-Clark addresses.

131 Fifthly, s 40(2)(a) is concerned with matters of description, not matters of proof. The respondent accepted this proposition. This is important because the specification teaches that the invention will be effective in the treatment of pain in mammals, including humans. There is no allegation that this teaching is a false suggestion or misrepresentation. Further, the respondent’s allegation of inutility has now been abandoned. Thus, as the appellants submitted, it is not to the point that, in clinical practice, a clinician would want proof of safety and efficacy beyond the description of the invention in the specification itself. This is not the province or function of the requirement in s 40(2)(a).

132 The respondent’s essential proposition, on this aspect of its sufficiency challenge, is that the description of the invention in the specification leaves the person skilled in the art with too much work to do. The primary judge disagreed. As we have noted, his Honour reasoned (at [259]) that, if the steps required to be taken to work the invention are readily apparent to the person skilled in the art, and they are standard or routine steps within the competence of that person, then the test for sufficiency will be satisfied. We see no error in that approach. Further, we see no error in the primary judge’s finding of fact that the work required in the present case was routine for the person skilled in the art.

133 Once this is accepted, it is beside the point that, in undertaking the task, the person skilled in the art might need to apply considerable skill, effort and resources, or that the work might be complex, time-consuming and expensive. Work of this kind would not be of the character captured by the second limb of the test in Kimberly-Clark (i.e., work requiring prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty). Once the invention has been described, it does not lack sufficiency (in terms of description) because the person skilled in the art needs to take further steps which are known to be required and which are, for that person, routine in character. Put another way, the need for such steps does not mean that the description has not enabled the person skilled in the art to work the invention. In terms of s 40(2)(a), the invention has been “fully described”.

134 Further, we do not accept that the primary judge’s reference to, and reliance upon, Heerey J’s observations in Eli Lilly or the Full Court’s observations in Merck manifests error. His Honour’s reference to, and reliance upon, each authority was apposite. There are, undoubtedly, differences between the descriptions of the invention in each specification, as well as differences in the facts and circumstances of each case. The primary judge’s reliance on Eli Lilly was simply to explain that work might be routine for the person skilled in the art even though it might also require the skill and expertise of that person, and even though it might entail considerable investment in time and resources. The primary judge’s reliance on Merck was to distinguish between work necessary to perform a pharmaceutical invention and other work, such as testing and checking the invention or obtaining regulatory approval to enable the invention to be used in clinical practice. We do not accept, as the respondent’s submissions suggest, that the primary judge considered that the work required of the person skilled in the art in the present case was simply testing and checking. The work was of a different character. Nevertheless, the primary judge was not persuaded that the work was other than routine and, as we have recorded, there is now no dispute about that fact.

Conclusion

135 For these reasons, no error has been shown in the primary judge’s conclusion at [284] that the challenge to validity of the patent based upon alleged insufficiency of description fails. It follows that the Grounds 1 to 5 of the cross-appeal, as advanced by the respondent in submissions, also fail.