FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Steelforce Trading Pty Ltd v Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science [2018] FCAFC 20

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The Respondents pay the Appellants’ costs of the appeal as taxed or agreed.

3. Set aside the orders of the Federal Court made on 9 November 2016 and in lieu thereof order that:

1. The Second Respondent’s Report No 285 and the recommendations contained within it be quashed.

2. The First Respondent not rely upon Report No 285 and the recommendations contained within it for the purposes of any decision under Division 5 of Part XVB of the Customs Act 1901 (Cth).

3. The matter be remitted to the Second Respondent for preparation of a report according to law.

4. The Respondents pay the Appellants’ costs of the proceedings as taxed or agreed.

4. The reasons of the Court be embargoed for a period of 72 hours and access to them be granted only to the parties and their representatives during that time.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1. Introduction

1 This is an appeal from orders made by a judge of this Court dismissing an application for judicial review in an anti-dumping proceeding. It concerns steel pipes manufactured in China by the Second Appellant (‘Dalian’) and imported into Australia by the First Appellant (‘Steelforce’).

2 On 3 July 2012, the Minister published a notice which imposed a dumping duty of 13.4% on the import of certain steel pipes made by Dalian. He also published a notice imposing a countervailing duty of 11.1%. The goods which were the subject of these measures were formally described in these terms:

‘…certain electric resistance welded pipe and tube made of carbon steel, comprising circular and non-circular hollow sections in galvanised and non-galvanised finishes. The goods are normally referred to as either CHS (circular hollow sections) or RHS (rectangular or square hollow sections). The goods are collectively referred to as HSS (hollow structural sections). Finish types for the goods include in-line galvanised (ILG), pre-galvanised, hot-dipped galvanised (HDG) and non-galvanised HSS.’

3 I will refer to the goods collectively as HSS. The circular HSS had a range in diameter from 21 mm to 165.1 mm. The oval, square and rectangular HSS ranged in size up to an external perimeter of 1277.3 mm.

4 On 27 November 2015, this Court set aside the imposition of the countervailing duty: Dalian Steelforce Hi-Tech Co Ltd v Minister for Home Affairs [2015] FCA 885; (2015) 243 FCR 190. The current appeal arises out of a step taken by the Appellants in relation to the dumping duty amount whilst the Court was reserved on the countervailing duty issue. That step was the seeking by the Appellants of a review of the amount of that duty in the 2014 year.

5 It is necessary to say a few words about the review regime. The legislative regime in the Customs Act 1901 (Cth) (‘the Act’) which underpins the imposition of dumping duties has as one of its central features the concept of the ‘normal value of goods’ which is defined in s 269TAC. Leaving out unnecessary detail, s 8(2)(b) of the Customs Tariff (Anti-Dumping) Act 1975 (Cth) allows the imposition of a dumping duty where the export price of goods brought into Australia is less than their ‘normal value’.

6 Where ‘like goods’ are sold in the country of export in transactions which are at arms length, the normal value will generally be that sale price (s 269TAC(1)). The term ‘like goods’ is defined in s 269T to mean ‘goods that are identical in all respects to the goods under consideration or that, although not alike in all respects… have characteristics closely resembling those of the goods under consideration’. However, the approach in s 269TAC(1) for determining normal value need not be adopted if the Minister is satisfied that during the relevant review period the situation in the country of export was such that sales in that market were not suitable for determining a price (s 269TAC(2)(a)(ii)). When the dumping duty was initially imposed on imports by Steelforce this was, in fact, determined to be the case.

7 Circumstances may change in the country of export, however, and such changes may mean that the dumping duty needs to be revisited. The process by which this is done is known as a review of anti-dumping measures. Reviews are governed by Division 5 of Part XVB of the Act. Steelforce lodged a request for such a review with the Commissioner on 10 March 2015. The application was not rejected and, in consequence, on 9 April 2015 the Commissioner initiated a review of the dumping duty for the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014. Although most of the legislation refers to the functions of the Minister, s 269TE requires the Commissioner in formulating a recommendation to act as if he were the Minister.

8 The Commissioner concluded that the review would be into four ‘variable factors’, two of which are germane to the present appeal, namely, the ascertained ‘export price’ and the ascertained ‘normal value’ of HSS. Success on the review by Steelforce would lead to a potential refund of the duty already paid. The controversies in this appeal are largely concerned with the normal value.

9 In straightforward cases, the assessment of the normal value of goods proceeds by an examination of the sale price in arms length transactions for the same goods in the domestic market of the country of origin. With that background in mind it is useful to turn to the first ground of appeal which concerns an alleged denial of procedural fairness to the Appellants during the review process.

2. Procedural Fairness: Ground 1

10 In this case, it was accepted by the Appellants, and initially by the Commissioner, that Dalian’s sales of HSS in the Chinese domestic market should not be used in the calculation of the normal value of the goods. I return in more detail to the reason for this below, but for now it will suffice to observe only that it was related to the nature of Dalian’s sales in China as being effectively of unwanted lower quality product. It was accepted on all sides, in light of that fact, that an alternative methodology specified in s 269TAC(2)(c) of the Act was to be used. Subsections 269TAC(2) and 269TAC(6) (which will later become relevant) provided as follows:

‘269TAC Normal value of goods

…

(2) Subject to this section, where the Minister:

(a) is satisfied that:

(i) because of the absence, or low volume, of sales of like goods in the market of the country of export that would be relevant for the purpose of determining a price under subsection (1); or

(ii) because the situation in the market of the country of export is such that sales in that market are not suitable for use in determining a price under subsection (1);

the normal value of goods exported to Australia cannot be ascertained under subsection (1); or

(b) is satisfied, in a case where like goods are not sold in the ordinary course of trade for home consumption in the country of export in sales that are arms length transactions by the exporter, that it is not practicable to obtain, within a reasonable time, information in relation to sales by other sellers of like goods that would be relevant for the purpose of determining a price under subsection (1);

the normal value of the goods for the purposes of this Part is:

(c) except where paragraph (d) applies, the sum of:

(i) such amount as the Minister determines to be the cost of production or manufacture of the goods in the country of export; and

(ii) on the assumption that the goods, instead of being exported, had been sold for home consumption in the ordinary course of trade in the country of export—such amounts as the Minister determines would be the administrative, selling and general costs associated with the sale and the profit on that sale; or

(d) if the Minister directs that this paragraph applies—the price determined by the Minister to be the price paid or payable for like goods sold in the ordinary course of trade in arms length transactions for exportation from the country of export to a third country determined by the Minister to be an appropriate third country, other than any amount determined by the Minister to be a reimbursement of the kind referred to in subsection 269TAA(1A) in respect of any such transactions.

…

(6) Where the Minister is satisfied that sufficient information has not been furnished or is not available to enable the normal value of goods to be ascertained under the preceding subsections (other than subsection (5D)), the normal value of those goods is such amount as is determined by the Minister having regard to all relevant information.

…’

(Subsection 269TAC(2)(d) did not apply).

11 The figure in s 269TAC(2)(c)(i) is an actual figure but the administrative, selling and general costs mentioned in 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) are hypothetical amounts. The Act provides that the regulations may specify methods for determining the administrative, selling and general costs referred to in 269TAC(2)(c)(ii). This has been done by reg 44 of the Customs (International Obligations) Regulation 2015 (Cth) (‘the Regulation’). In ordinary cases where like goods are sold into the domestic market, reg 44(2) requires the use of the relevant business records of the producer (if they exist). Where the relevant business records do not permit this process, reg 44(3) sets up an inquiry instead into various amounts incurred in relation to goods ‘of the same general category’. It was this path down which the Commissioner in this case went. Reg 44(3) provides:

‘44 Determination of administrative, selling and general costs

(3) If the Minister is unable to work out the amount by using the information mentioned in subsection (2), the Minister must work out the amount by:

(a) identifying the actual amounts of administrative, selling and general costs incurred by the exporter or producer in the production and sale of the same general category of goods in the domestic market of the country of export; or

(b) identifying the weighted average of the actual amounts of administrative, selling and general costs incurred by other exporters or producers in the production and sale of like goods in the domestic market of the country of export; or

(c) using any other reasonable method and having regard to all relevant information.

…’

12 The selection by the Commissioner (or thereafter the Minister) of the goods which are to serve as the goods of ‘the same general category’ as the goods which are being imported into Australia can be a significant one. If a range of goods is selected which is more expensive than the imported goods then this may have the effect of increasing the normal value and therefore the amount of any dumping duty imposed on the imports.

13 In effect, the driver behind the present appeal (although not the legal substance of the appeal) concerns just such a proposition. The Appellants’ complaint is that the manner in which the administrative, selling and general costs were calculated under reg 44(3) involved the selection of a range of steel pipes to serve as goods ‘of the same general category’ as the imported goods, which the Appellants reject were in facts goods ‘of the same general category’, and which has thereby increased the ‘normal value’ of the HSS under s 269TAC to their disadvantage.

14 The legal arguments they advance necessitate an understanding of the factual circumstances surrounding Dalian’s sales of HSS in the Chinese domestic market. However, that topic is best grasped by following what was said at various points during the review process.

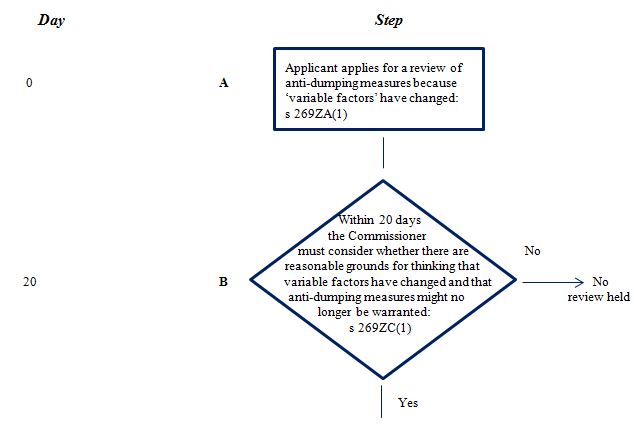

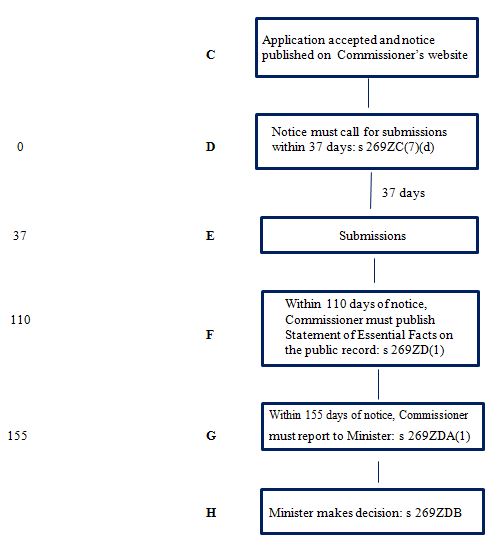

15 The review process is regulated by Division 5 of Part XVB of the Act. The following diagram will illustrate it. The diagram is simplified:

16 In addition to the above steps, the Commissioner also gave to Dalian an exporter questionnaire to complete at the outset of the process. That questionnaire appears to have been completed by Dalian twice. The first form of the questionnaire was returned to the Commissioner in February 2015 even before Steelforce’s application for a review was lodged but that related to a different importation period (3 January 2014 to 2 July 2014) and appears to be relevant to an earlier investigation undertaken by the Commissioner. A second, updated version of it appears then to have been lodged in May 2015. Whatever their legal status, there is no doubt the Commissioner used them in preparing his Statement of Essential Facts at Step F in the diagram above for they are expressly referred to in it.

17 It is then useful to turn to the facts which underpin the present debate. At a high level of generality, it may be said that these facts concern the identification of goods sold in the Chinese domestic market which were of the same general category as those imported into Australia.

18 The first step in that process of identification appears in the first questionnaire submitted by Dalian to the Commissioner. At p 23, this question was posed by the Commissioner:

‘If you sell like goods on the domestic market, for each model/type that your company has exported to Australia during the assessment period, list the most comparable model(s) sold domestically and provide a detailed explanation of the differences where those goods sold domestically (ie. the like goods – see explanation in glossary) are not identical to the goods exported to Australia.’

19 It will be recalled that the HSS imported into Australia was either square/rectangular (RSS) or circular (CHS) or oval. CHS is also called pipe. According to the questionnaire, Dalian produced HSS with five types of finish for the Australian market. These were:

black, also called ‘not oiled painted or coloured’ or ‘NOPC’ or unpainted HSS (presumably, unpainted steel pipes are black);

blue painted HSS;

red painted HSS but only for pipe, i.e., CHS;

black painted HSS but only for pipe; and

pregalvanised HSS (that is, HSS made from galvanised coil).

20 So these three types of HSS (RHS, CHS and oval) in these five different finishes were what Dalian was actually exporting to Australia. To the question set out above of what similar kinds of product it was selling domestically in China, Dalian answered this way:

‘Dalian Steelforce does not produce HSS specifically for sale in the Chinese market. The HSS produced is manufactured to Australian standards and is intended for export to Australia. HSS is only sold by Dalian Steelforce in very minor quantities on the Chinese market. Any HSS sold to the Chinese market would be an exceptional sale, taken from stock which would have been originally produced for Australian export purposes but for some reason or other was not ultimately sold to Australia.

The anomaly of these domestic sales is further evidenced by the nature of the customers, which are named individuals that have approached Dalian Steelforce for urgent stock on hand.

Please also note that the listed domestic sales are a combination of carbon-HSS (the goods) and alloy-HSS (not the goods). As these sales are taken directly from stock on hand and are sold to individual customers, Dalian Steelforce does not record or identify whether the goods are carbon-HSS or alloy-HSS.

Therefore, where carbon-HSS was sold domestically, it will have been identical to a particular type of carbon-HSS exported to Australia as all types of carbon-HSS produced by Dalian Steelforce is produced for export to Australia.

Dalian Steelforce is generally unable to sell lower quality HSS to its Australian customers. Almost all downgrade material is cleared from the factory by way of being sold on the domestic market.’

21 A couple of observations should be made about this. First, the reference to ‘carbon-HSS’ and ‘alloy-HSS’ requires some explanation. It will be recalled that the pipes which were subject to the dumping duties were described as ‘carbon steel’ and it is to this that carbon-HSS refers. Alloy-steel contains additional elements such as, for example, nickel. The HSS imported into Australia was not made from alloy-steel in this sense.

22 Secondly, it will be seen that the answer suggested that Dalian’s domestic sales were made from stock produced for export to Australia but not ultimately sold into that market for one reason or another.

23 Thirdly, the last two paragraphs suggest that the HSS sold into the domestic market was the same as the HSS exported to Australia, only of lower quality. The answer called this lower quality HSS ‘downgrade’.

24 This topic was returned to a little later in the questionnaire in the section dealing explicitly with domestic sales. Dalian said this:

‘Dalian Steelforce was established for the purposes of manufacturing HSS for Steelforce Group operations in Australia and New Zealand. Dalian Steelforce does not sell HSS in commercial quantities in the Chinese domestic market.’

There were some domestic sales during the review period however they were uncommon and inconsistent. A significant volume of these domestic sales are considered ‘downgrade’ product – which is either reject or damaged stock.

Also please note that these domestic customers are individuals that approach Dalian Steelforce directly for urgent product. Accordingly, as the product offered to domestic customers is generally not suitable to be sold in the Australian market, Dalian Steelforce does not record whether the goods are of carbon-HSS or alloy-HSS.

As previously found by the Commission, these domestic sales are unsuitable for the purposes of a normal value. As determined by the Commission in Report No. 177 and subsequent duty assessments, the nature and characteristics of Dalian Steelforce’s domestic sales continue to be rare one-off sales to individuals that approach the company for urgent stock on hand. The goods are unusable products that were originally produced for export and for whatever reason, are unable to be meet and/or comply with their intended purpose.

In constructing a normal value under Section 269TAC(2)(c), adjustments under Section 269TAC(9) will need to be applied. The adjustments would need to be reasonable and relevant to “normal” sales that could be expected to have taken place if Dalian Steelforce had made sales on a commercial basis in the domestic market. The uncommon and inconsistent sales cannot be used for adjustment purposes, for the same reason that they cannot be used for normal value purposes.

Adjustments should be derived from the surrounding evidence obtained by Commission about the operation of the Chinese domestic market, and applied reasonably in the sale transaction assumed under Section 269TAC(2)(c).

In terms of profit the Minister would need to consider whether there does need to be such an addition in terms of the domestic market during the importation period, and in any case would need to be careful to determine a profit level only at the lower level of a trader in the domestic market for proper comparison purposes with the export sales.’

25 The second paragraph suggests that much – but not all – of the domestic sales were of downgrade material by which was meant reject or damaged stock. It is unclear from the above statement what the other sales are made up of. On the other hand, the previous quote is capable of suggesting that sales of alloy-HSS were involved.

26 At this point, it is fair to say that Dalian’s explanation of what was involved in its domestic sales was a little unclear.

27 It seems that there were further subsequent communications between Dalian and the Commissioner’s office on the topic of domestic sales. One of these was an email of 16 June 2015 sent by a Mr Bracic (on behalf of Dalian) to a Ms Stone of the Anti-Dumping Commission. The relevant portions of the email were as follows:

‘Andrea/Joe

Please find attached the following documents from Dalian Steelforce relevant to the HSS review of measures:

…

4. Revised Domestic Sales – All sales are now properly described as non–prime/downgrade and we have included the ocean freight expenses relevant to CFR sales. As explained below and evidenced by the test certificates, goods described as NOPC or pregal or painted are still classified as ‘downgrade’ by Dalian Steelforce as they do not meet the specifications or quality required by the Australian Standard (AS1163).

…

6. For the four selected domestic sales provided with the questionnaire response, the following additional supporting documentation is provided:

i) NAN HAI Contract SRTNH-14-50: The first 4 pages refer to the relevant invoices which sum to the sales value shown in D4. The next 2 pages show the test certificates for these goods which can be linked with the product and customer name. Please also note that these are referred to as downgrade product on the test certs even though they are described as NOPC in the domestic sales spreadsheet. The last page shows the total freight expense which is a combination of ocean freight and inland transport.

…

iii) Painted downgrade test certificates: Unfortunately the other 2 selected domestic sales were also downgrade for aesthetic reasons and not due to mechanical or chemical properties. So Dalian Steelforce have provided 2 further test certificates where the goods were classified as downgrade due to the yield strength not meeting the minimum 350 MPa required by the Australian Standard.

If you have any questions or require further information please feel free to contact me directly.

Cheers

John’

28 Of importance is the reference in paragraph 4 to all of the domestic sales now being described as non-prime or downgrade. No explanation is given, however, for what the distinction between these two products is. One of the Excel spreadsheets which accompanied the email was a ‘domestic sales summary’. It set out a list of domestic Chinese sales. The fifth column in the spreadsheet was entitled ‘Standard’ and for each entry there was a reference either to the product being ‘Non-prime’ or of it being ‘downgrade’.

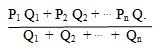

29 The twelfth column was entitled ‘Finish’. The entries under it were one of the following:

NOPC

Pregal

Painted

Downgrade

NOPC/Painted

Sample

30 In every case where the standard of the product was said to be ‘Downgrade’ this was also listed as its finish. On the other hand, no sale whose standard was listed as ‘Non-prime’ is listed as having a finish of ‘Downgrade’.

31 This spreadsheet (and paragraph 4 of the email which it accompanied) suggest that Dalian itself drew a distinction between non-prime product and downgrade product. That said, what the difference was is not clear.

32 In his oral address, counsel for the Appellants also sought to demonstrate that in this spreadsheet the distinction between non-prime and downgrade was not entirely clear. This was demonstrated by showing the Court a particular batch of purchases by one Nan Hei. The invoice for these purchases was numbered SRTNH-14-50. The underlying invoices had attached to them a quality certificate which described the goods as downgrade. Yet the spreadsheet description was ‘non-prime’. This matter was also referred to in the email of 16 June 2015 at paragraph 6(i).

33 I do not think that this detracts from the apparently clear distinction drawn in the spreadsheet between non-prime and downgrade HSS even if the nature of that distinction remains elusive.

34 Following receipt of this material, the Commissioner then produced his Statement of Essential Facts (‘SEF’, Step F at [15]) on 28 July 2015. At Section 4.4 he said this:

‘4.4 Like goods produced and sold in China by Dalian Steelforce

Dalian Steelforce advised that, during the review period, its domestic sales of HSS were dissimilar to its export sales, and consisted entirely of non-prime product or downgrade product. Non-prime or downgrade product is HSS that was initially intended for sale in the Australian market, but does not meet Australian standards.

In Investigation 177 the Commission found that although the non-prime and downgrade products were like goods to the goods exported to Australia, they were not sold ‘in the ordinary course of trade’. They are isolated sales of sub-standard product and it is more cost-effective to dispose of them locally than to export to Australia.’

35 This did not seem to distinguish between non-prime and downgrade or at least not in any meaningful way. But whatever they were, the Commissioner seemed to accept that they were both ‘like goods’ to the HSS being imported into Australia. However, their relevance was dismissed because they were not sold ‘in the ordinary course of trade’.

36 When the Commissioner came to deal with selling, general and administrative costs in the SEF, he was obliged to consider whether Dalian produced goods ‘of the same general category of goods in the domestic market’. On that topic he said this:

‘Dalian Steelforce does not have any domestic sales of goods in the same general category as the goods exported to Australia. While the Commission has access to recent information about the domestic SG&A costs of another exporter of HSS to Australia, it does not consider this entity’s costs suitable for the purpose of establishing Dalian Steelforce’s normal value due to the differences in the structure and operations of that entity compared to Dalian Steelforce.

In light of the above, the Commission has used subsection 44(3)(c) of the Regulations, any other reasonable method, and used the export SG&A costs as reported by Dalian Steelforce in relation to their sales of HSS to Australia for the purpose of constructing a normal value.

37 As will be recalled, s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) of the Act requires an amount of profit to be included in the calculation of the normal value of the goods. Subregulation 45(2) provides that, if reasonably possible, profit is to be determined as the profit made on like goods sold by the exporter domestically in the ordinary course of trade. Because the Commissioner had reached the view that there were no domestic sales of like goods in the ordinary course of trade, he chose to proceed under reg 45(3)(c). Before doing so, he quoted from an earlier report, Report 177. The quotation read:

‘…downgrade is completed whole pipe that, while still technically HSS, does not meet the requirements of the relevant Australian standards for prime HSS.

Dalian Steelforce explained that the most common kind of downgrade consists of lengths of pipe that contain the butt weld between two strips of HRC or where the pipe is not sufficiently straight. Product may also be classed as downgrade after its finish is applied, where the finish is marked or not be of a sufficient standard.’

38 This provides some support for the idea that there may have been two kinds of downgrade; one relating to the quality of the pipes themselves, the other to the quality of the finish. It may be possible to imagine that the latter might be ‘non-prime’ but this statement provides insufficient substance to accept that proposition. The observation is merely speculation.

39 In any event, the Commissioner needed to reach a conclusion on the topic of goods ‘of the same general category’. This he did at p 22 of the SEF in these terms:

‘Dalian Steelforce provided a domestic sales listing of like goods in response to the exporter questionnaire. This included sales of both non-alloy (carbon steel) HSS (the goods) and alloy HSS (not the goods, but like goods). However, as discussed above, the Commission is satisfied that these sales are only of products that are considered sub-prime or downgrade. The Commission again considers that the nature of these goods means that domestic sales made during the review period were not in the ordinary course of trade for the purposes of this review. As the Commission has found that there are no sales of the like goods in the ordinary course of trade, subsection 45(2) of the Regulations cannot apply.

Subsection 45(3) of the Regulations then directs the Minister to consider working out an amount for profit having regard to one of three methodologies. There is no hierarchy in terms of which methodology must be used. In practice “the Commission normally seeks profit information using the method described for …[Regulation 45(3)(a)] because it relates to the exporter being investigated and therefore is more likely to yield the required data.”

Subsection 45(3)(a) of the Regulations provides that the Minister can use the actual amounts of profit realised by the exporter from the sale of the same general category of goods in the exporter’s domestic market. Dalian Steelforce does not have any domestic sales of the same general category of goods during the review period that are considered suitable for the purpose of establishing a profit on domestic sales.’

40 The Appellants submit that this passage does not suggest, or give notice of, any contention by the Commissioner that a distinction might subsequently be drawn between downgrade and non-prime products. That submission was not denied by the Minister and I accept it. The process of reasoning revealed in this paragraph was that the Commissioner treated non-prime and downgrade collectively but thought that sales thereof were not in the ordinary course of trade. Although there might have been a distinction between downgrade and non-prime, it was not a difference which was material to the Commissioner’s conclusion and it was not part of his reasoning.

41 Once the Commissioner published the SEF on 28 July 2015 a period of 20 days was provided in the Act for interested parties to make submissions in response, although the Commissioner was also able to have regard to late filed submissions if doing so would not prevent the timely preparation of his report to the Minister: s 269ZDA. It appears that that is what occurred in this case. One of the Appellants’ competitors, Austube Mills Pty Ltd (‘ATM’), made such a submission on 17 August 2015. It specifically addressed the question of profit under reg 45. The relevant part was in these terms:

‘ATM submits that the Commission has erred by not including a level of profit in the Dalian Steelforce constructed normal value. Subsection 269TAC(5B) requires an amount of profit to be determined in accordance with subsection 45 of the Regulations. The Commission has in accordance with the regulations considered the requirements of Subsection 45(2) and (3). ATM disagrees with the Commission’s conclusion that it cannot work out an amount of profit for Dalian Steelforce as it is claimed that the only domestic sales of like goods in the ordinary course of trade are for “sub-prime or downgrade” goods. It is not clear from SEF 285 how the Commission was satisfied that the referred domestic sales that were confirmed as sub-prime or downgrade were not either a “like good” or a good of the “same general category” when subprime product whilst not suitable for sale to Australian standards may have been suitable sale to Chinese standards.

“As highlighted and explained in Dalian Steelforce’s exporter questionnaire response, all sales of HSS on the Chinese market are exceptional sales, taken from stockpiles of non-prime products which failed to comply with strict quality control measures based on Australian Standards.”

ATM contends that these sales – that are alike and considered as such by the Commission – can be used for determining a level of profit to be applied in Dalian Steelforce’s s. 269TAC(2)(c) constructed normal value. The provisions do not permit the Minister to exclude the profit on sales of like goods that are described as “non-prime” goods by Dalian Steelforce. The non-prime goods are alike to the exported goods and the level of profit included in those domestic sales must be used on the basis of subsection 45(3) by “having regard to all relevant information”.

Without detracting from ATM’s views as to the profit on the domestic sales of Dalian Steelforce’s sales of non-prime HSS, where it is deemed that these sales are unsuitable, the Commission can avail itself of the profit on the domestic sales by the other Chinese HSS producer, Tianjin Youfa (from Investigation No. 267). Subsection 45(3)(b) of the Regulations does not limit the Minister from applying the level of profit to Dalian Steelforce’s constructed normal value where only one additional Chinese exporter’s profit is available.

It is ATM’s position that there is sufficient “relevant information” upon which to calculate an amount of profit to be applied to Dalian Steelforce’s constructed normal value and that either of the proposed options is considered “reasonable”.’

(emphasis added)

42 There are two issues arising from this letter. To understand them it is necessary to jump forward and to know that in the Commissioner’s final report to the Minister (‘Final Report’) he decided to include non-prime sales in the calculation of profit but to exclude downgrade. It will be evident from what has been said about the SEF that there was no indication from the Commissioner in that document that he would distinguish downgrade from non-prime. I return to the detail of the Final Report below. The two issues which arise in the case of the ATM submission are these: first, is it a submission which in fact argues that non-prime should be handled differently to downgrade; secondly, if it is such a submission, did it constitute sufficient notice to the Appellants that that distinction was going to be drawn?

43 It is necessary to read the submission with some care and in context. The first part of that context is that ATM was arguing that the position enunciated in the SEF that no profit component would be used in calculating the normal value was disputed. The SEF had recorded that whilst there were sales of downgrade and non-prime products in the domestic market they were not made in the ordinary course of business. ATM’s answer to this appears to have been that it was wrong for the Commissioner not to include an amount for profit on this basis where the Commissioner had not disputed that the goods were alike or of the same general category. ATM submitted that the non-prime goods were in fact alike to the imported goods and that the ‘level of profit included in those domestic sales must be used on the basis of subregulation 45(3) by “having regard to all relevant information”’ irrespective of whether or not they were sold in the ordinary course of business. ATM did not make that submission about downgrade sales.

44 It seems, therefore, that ATM was inviting the Commissioner to approach non-prime product sold in China as the sale of goods ‘of the same general category’ as the imported goods, but not downgrade product. It also seems to me that a person in the industry would regard what was said by ATM as sufficiently clear to communicate the point which was being made. This was the primary judge’s conclusion in Steelforce Trading Pty Ltd v Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science [2016] FCA 1309 at [70] and I do not think his Honour erred in reaching that conclusion.

45 In fact, a submission in response to the ATM submission was lodged on behalf of Steelforce on 20 August 2015. On the topic of level of profit it said this:

‘ATM states that it disagrees with the Commission’s finding that profit on sales of like goods were not able to be determined under subsection 45(2) of the Regulations. In particular, ATM states that it disagrees with the Commission’s conclusion ‘that it cannot work out an amount of profit for Dalian Steelforce as it is claimed that the only domestic sales of like goods in the ordinary course of trade are for “sub-prime or downgrade” goods’.

It appears to Dalian Steelforce that ATM has misunderstood the Commission’s findings in SEF 285 as they have ultimately concluded that sales of like goods were not sales made in the ordinary course of trade. As explained in SEF 285, this finding is consistent with the Commission’s original findings in REP 177 and REP 2013.

Further, ATM appears to again be submitting a position inconsistent with its previous views. In the original investigation, OneSteel ATM commented on domestic sales of downgrade pipe by the Taiwanese exporter, Yieh Phui, and submitted that ‘[a]s there are no export sales of downgrade pipe, OneSteel ATM does not consider that a fair comparison can be made if domestic sales of downgrade pipe are included in normal value calculations’.

46 This submission sought to meet ATM’s submission that non-prime product could be like goods or goods of the same general category by reiterating the Commissioner’s earlier finding that neither non-prime nor downgrade products were sold in the domestic market in the ordinary course of trade. As such it can be seen that not only was ATM’s submission sufficiently clear to put the Appellants on notice but that their responsive submission actually put forward an argument as to why ATM’s argument should not be accepted.

47 It is true that the Appellants did not seek in their submission to argue that ATM’s submission that non-prime might be considered as part of the like goods (or goods of the same category) but not downgrade should be rejected because no distinction could properly be drawn between non-prime and downgrade goods. But that does not mean that they were not afforded an opportunity to comment on that submission by ATM nor that the Appellants had not been adequately informed that ATM was proposing that non-prime be treated separately to downgrade.

48 The next step was the production of the Final Report. This was Report 285. The relevant portion was as follows:

‘The Commission has further examined the sales of alloyed HSS made during the review period and considers that alloyed HSS is not a like good to non-alloy HSS, on the basis that alloyed HSS is not subject to the dumping duty notice. This is consistent with the view of Dalian Steelforce, which has claimed in Anti-Circumvention Inquiry 291, that:

…its exports of alloyed hollow structural sections (HSS) to Australia clearly do not fall within the parameters of the goods described in the dumping and countervailing duty notices relevant to carbon or non-alloyed HSS.

In relation to the domestic sales of like goods, the Commission is satisfied that these sales are only of products that are considered non-prime or downgrade, and again considers that the nature and low volume of these goods means that domestic sales made during the review period were not in the ordinary course of trade for the purposes of this review. As the Commission has found that there are no sales of the like goods in the ordinary course of trade, subsection 45(2) of the Regulations cannot apply.

Subsection 45(3) of the Regulations then directs the Minister to consider working out an amount for profit having regard to one of three methodologies. There is no hierarchy in terms of which methodology must be used. In practice, “the Commission normally seeks profit information using the method described for Regulation 45(3)(a) because it relates to the exporter being investigated and therefore is more likely to yield the required data”.

Subsection 45(3)(a) of the Regulations provides that the Minister can use the actual amounts of profit realised by the exporter from the sale of the same general category of goods in the exporter’s domestic market. The Commission considers that Dalian Steelforce’s domestic sales of non-prime alloyed HSS and non-prime non-alloy HSS comprise the same general category of goods. Non-prime HHS is considered to be the closest category of goods to the ‘prime’ HSS exported to Australia. The Commission notes that these sales include sales of like goods not considered to be made in the ordinary course of trade, as outlined previously. However, subsection 45(3)(a) does not require that the domestic sales of the same general category of goods be made in the ordinary course of trade. Consequently, these sales are considered suitable for the purpose of establishing an amount for profit.

…

Based on the above, in accordance with subsection 45(3)(a) of the Regulations the Commission has added the profit from Dalian Steelforce’s sales of the same general category of goods in the Chinese domestic market to the constructed cost to manufacture and sell the goods domestically.’

(emphasis added)

49 What this meant in practical terms is that the Commissioner changed his position on whether any profit component was to be included in relation to domestic sales. Previously, in the SEF, he had not included any such profits. Now, he included the non-prime products without including the downgrade products.

50 The information which was provided under the email of 16 June 2015 (referred to above at [27]) included the Excel spreadsheet referred to above at [28]. It contained sales information which was listed by reference to downgrade and non-prime product. The Commissioner used this to generate a profit figure of XX.XX% when only non-prime was considered. The Court was provided with a copy of the Commissioner’s Confidential Appendix 7 (entitled ‘Profit Calculation’) to the Final Report. It was behind Tab 10.29 of the Appeal papers. The Court was also provided with the original Excel file. The spreadsheet allows one readily to calculate the profit on different kinds of domestic sales. It reveals this:

profit on sale of non-prime only: XX.XX%

profit on sale of non-prime and downgrade: XX.XX%

profit on sale of downgrade only: XX.XX%.

51 The effect of the Commissioner’s decision was that Dalian was found to be making a profit on its domestic sales of XX.XX%. This had the effect of increasing the ‘normal value’, and as a consequence of that, the dumping duty margin applied thereafter to Steelforce’s imports. If ‘downgrade’ had been included, it will be seen that the profit rate drops to XX.XX% which would have had the effect of decreasing the dumping duty applicable. It is also to be borne steadily in mind that Confidential Appendix 7 was generated from the Excel spreadsheet provided by Dalian itself. The distinction between non-prime and downgrade was in its data as foreshadowed in the email of 16 June 2015.

52 In those circumstances, it is not possible to accept that there was a breach of the rules of natural justice in the Commissioner deciding to treat non-prime products separately from downgrade products for the purposes of s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii). Ground 1(b) must be rejected. For the same reasons, Ground 1(a) must also be rejected.

3. No evidence: Ground 2

53 This ground involved the contention that there was no evidence before the Commissioner to justify a finding that non-prime goods were different to downgrade. This submission is unsustainable in light of the following:

Dalian’s own sales data submitted to the Commissioner distinguished between non-prime and downgrade products;

Dalian’s email of 16 June 2015 explicitly distinguished them; and

the profit levels on the two products were significantly different as revealed in Dalian’s own data. I reject the submission made by counsel for the Appellants that this matter is irrelevant.

54 It is thus not correct to say that there was no evidence to distinguish them. It may be that different views might be taken of what this evidence signified, but that state of affairs is incapable of sustaining an allegation that the Commissioner had acted in the absence of evidence. This is not, therefore, a case where the Commissioner drew an inference which was not reasonably open: cf. Australian Broadcasting Tribunal v Bond [1990] HCA 33; (1990) 170 CLR 321 at 356 per Mason CJ. The ground must be rejected.

4. No appropriate findings: Ground 2A

55 Ground 2A was a variant of Ground 2. Whereas Ground 2 contended that the Commissioner had acted in the absence of evidence, Ground 2A alleged that the Commissioner had made inadequate findings of fact to justify the conclusion that non-prime HSS in the domestic market was similar to the prime HSS in Australia and different from downgrade.

56 As developed briefly in their submissions, the argument was that before the Commissioner could draw that conclusion he had to have made sufficient findings of fact. This proposition was said to be supported by three authorities: Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Yusuf [2001] HCA 30; (2001) 206 CLR 323 (‘Yusuf’) at 330 [5], 338 [37]; Craig v South Australia [1995] HCA 58; (1995) 184 CLR 163 (‘Craig’) at 179; Alexander v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2010] FCA 189; (2010) 233 FCR 575 (‘Alexander’). The passage cited in Craig does not relate to this topic. The decision of Bromberg J in Alexander involves an application of Yusuf. The point being advanced is therefore an argument proceeding only from Yusuf.

57 Yusuf was concerned, in part, with s 430 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) which required the then Refugee Review Tribunal to set out in its reasons ‘the findings on any material questions of fact’. Gleeson CJ observed at 330 [5] that the effect of s 430 on the Tribunal was this:

‘If it does not set out a finding on some question of fact, that will indicate that it made no finding on that matter; and that, in turn, may indicate that the Tribunal did not consider the matter to be material.’

58 Gaudron J made a similar remark at 338 [37].

59 There is an equivalent to s 430 in the Customs Act. It is s 269ZDA(5) and it requires the Commissioner to set out ‘material findings of fact on which [the] recommendation is based’ . It is reasonable to accept therefore that the observations of Gleeson CJ and Gaudron J do apply to the Commissioner in producing his recommendation to the Minister.

60 The difficulty for the Appellants is that the Commissioner did this. I have set out the central passage for the Final Report above at [48] but it contains the finding of the relevant material fact for the purposes of s 269ZDA(5):

‘The Commission considers that Dalian Steelforce’s domestic sales of non-prime alloyed HSS and non-prime non-alloy HSS comprise the same general category of goods.’

61 Neither s 269ZDA(5) nor Yusuf required the Commissioner to make an additional finding of fact before the fact above was stated. In particular, the Commission was not required to find as an anterior matter that HSS other than non-prime (that is to say, downgrade) was not part of the same general category of goods.

62 Section 269ZDA(5)(b) did require the Commissioner to provide particulars of the evidence relied on to make this finding. However, such particulars were provided. The obligation to provide particulars of the evidence will be sufficiently discharged by referring to that evidence. The finding of fact set out above was contained in section 4.4.3.2 of the Final Report which explicitly referred to Dalian’s domestic sales list – that is, the list which drew a distinction between non-prime and downgrade. That is sufficient for present purposes. A similar point may be made about the profit calculation which was Appendix 7.

63 I would reject ground 2A.

5. Same general category of goods: Ground 3

64 Subregulations 45(2)-(4) and 45(6) provide:

‘45 Determination of profit

…

(2) The Minister must, if reasonably practicable, work out the amount by using data relating to the production and sale of like goods by the exporter or producer of the goods in the ordinary course of trade.

(3) If the Minister is unable to work out the amount by using the data mentioned in subsection (2), the Minister must work out the amount by:

(a) identifying the actual amounts realised by the exporter or producer from the sale of the same general category of goods in the domestic market of the country of export; or

(b) identifying the weighted average of the actual amounts realised by other exporters or producers from the sale of like goods in the domestic market of the country of export; or

(c) using any other reasonable method and having regard to all relevant information.

(4) However, if:

(a) the Minister uses a method of calculation under paragraph (3)(c) to work out an amount representing the profit of the exporter or producer of the goods; and

(b) the amount worked out exceeds the amount of profit normally realised by other exporters or producers on sales of goods of the same general category in the domestic market of the country of export;

the Minister must disregard the amount by which the amount worked out exceeds the amount of profit normally realised by the other exporters or producers.

…

(6) For paragraph (3)(b), subsection 269T(5A) of the Act sets out how to work out the weighted average’.

65 This requires an assessment of the amounts realised ‘from the sale of the same general category of goods’ in the domestic market. The primary judge accepted (at [86]) that once the general category had been identified the Commissioner could not lawfully disregard some subset of the general category in carrying out the profit calculation.

66 This mattered because the Appellants argued that it was clear from several parts of the Final Report that the Commissioner had determined that non-prime and downgrade product were both of the same general category of goods. If this were correct, it had significant implications for his treatment of the topic of profit (at paragraph 4.4.3.2 of the Final Report) for, as set out above, it was clear that the Commissioner had decided to treat non-prime goods differently to downgrade. If the Commissioner had indeed concluded that non-prime and downgrade HSS were in the same general category of goods, then given the way in which the primary judge had construed reg 45(3)(a), this would have involved error on the part of the Commissioner.

67 It was not suggested in this Court that the primary judge’s approach to the construction of reg 45(3)(a) was incorrect. Nevertheless, his Honour rejected the present argument at first instance on the basis that the critical finding at paragraph 4.4.3.2 that the same general category of goods comprised non-prime HSS did not include any statement about downgrade. Consequently, so his Honour reasoned at [90], paragraph 4.4.3.2 should be read as saying that downgrade was not of the same general category of goods.

68 That implicit finding in paragraph 4.4.3.2 discerned by the primary judge is said by the Appellants to be difficult to reconcile with at least four other passages in the Final Report which, it is alleged, treat non-prime and downgrade as being in the same class. It is necessary to consider each.

69 The first was at paragraph 3.6. There the Commissioner was considering the slightly different question to that of whether goods of the same general category were being sold in the domestic market. The Commissioner was instead considering the narrower – and anterior – question of whether ‘like goods’ were being sold in that market. The Commissioner’s initial position had been that non-prime and downgrade were ‘like goods’ to the HSS sold in Australia but were to be disregarded because such sales as there had been had not been in the ordinary course of business. The actual finding was in these terms:

‘In Investigation 177 the Commission found that although the non-prime and downgrade products were like goods to the goods exported to Australia, they were not sold ‘in the ordinary course of trade’. They are isolated sales of sub-standard product and it is more cost-effective to dispose of them locally than export to Australia.’

70 It is true that this appears to treat them, if not as being of ‘the same general category’ in the legal sense, then at least in the same class. The second passage relied upon was at paragraph 4.4.2.2 which dealt with the Commissioner’s assessment of the selling, general and administrative costs for the purpose of constructing a normal value. The relevant portion is as follows:

‘Following further examination of Dalian Steelforce’s domestic sales as detailed in section 4.4.3.2 below, the Commission considers that Dalian Steelforce has domestic sales of goods in the same general category as the goods exported to Australia. However, the Commission notes that these sales are of non-prime and downgrade products and are isolated sales of sub-standard product, for which it is more cost-effective for Dalian Steelforce to dispose of locally than export to Australia. For this reason, the Commission continues to consider that Dalian Steelforce’s export SG&A costs are the most suitable for the purpose of constructing a normal value.’

71 The reference to paragraph 4.4.3.2 is, of course, to the same paragraph where the critical finding about non-prime HSS being of the same general category of goods is made. There is no doubt that this passage appears to involve a finding that non-prime and downgrade are both of the same general category of goods. This contrasts with the finding at paragraph 4.4.3.2 that the same general category comprised only non-prime (omitting any reference to downgrade). The Appellants are correct that this is an inconsistency in the Final Report.

72 Thirdly, the Appellants pointed to a passage in paragraph 4.4.3. That paragraph was the fourth paragraph for the Final Report’s discussion of profit. The relevant portion reads:

‘In terms of the nature of these sales, Investigation 177 found that all sales of domestic like goods by Dalian Steelforce during the investigation period were of non-prime or downgrade product.’

73 It then went on to quote from Investigation 177 and set out a discussion of the nature of downgrade HSS. This involved a discussion of ‘like goods’ rather than the ‘same general category’ of goods but we accept that it appears to treat them as being in the same class, broadly speaking.

74 The fourth passage was at p 27 of the Final Report and was in these terms:

‘In relation to the domestic sales of like goods, the Commission is satisfied that these sales are only of products that are considered non-prime or downgrade, and again considers that the nature and low volume of these goods means that domestic sales made during the review period were not in the ordinary course of trade for the purposes of this review. As the Commission has found that there are no sales of the like goods in the ordinary course of trade, subsection 45(2) of the Regulations cannot apply.’

75 Again, it will be seen that this is another example of non-prime and downgrade being treated together under the rubric of ‘like goods’. Indeed, three of the four passages relied upon by the Appellants have that feature. The process of reasoning undertaken by the Commissioner is, perhaps, a little opaque but was, in effect, as follows:

(a) both the non-prime and downgrade products were ‘like goods’ to the HSS being sold in Australia;

(b) but both sets of sales were not made by Dalian in the ordinary course of its business (due to low volume);

(c) accordingly, profit could not be calculated using these sales: reg 45(2) of the Regulation;

(d) but the non-prime HSS was also ‘of the same general category of goods’ as the prime HSS imported into Australia;

(e) sales of non-prime HSS could be utilised to calculate the profit because unlike reg 45(2), reg 45(3) was not subject to a requirement that the sales be in the ordinary course of trade.

76 There is, perhaps, a certain tension between the conclusion that non-prime and downgrade products were ‘like goods’ to prime HSS but that non-prime HSS was the only product ‘of the same general category of goods’ as the goods imported to Australia whilst (implicitly) downgrade was not. However, that is not the argument that the Appellants pursued. Leaving that point aside, there is no inconsistency in the way the Commissioner reasoned in this regard. To say that both non-prime and downgrade products are ‘like goods’ to prime HSS does not entail any statement about the different topic of ‘same general category’. There may have been another argument about this available but it was not pursued.

77 This means that three of the four alleged inconsistencies are not inconsistencies at all. That does, however, leave the passage at 4.4.2.2 which I accept is inconsistent with paragraph 4.4.3.2.

78 The primary judge reasoned that the reasons of the Commissioner were not to be read with an eye keenly attuned to the perception of error citing at [89] Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Wu Shan Liang [1996] HCA 6; (1996) 185 CLR 259 at 272. He dismissed the inconsistencies as ‘looseness of language’: [89].

79 I agree with the primary judge. In light of the materials before the Commissioner (including particularly Dalian’s own sales list and the ATM submission) it is clear that the finding at paragraph 4.4.3.2 means what it says: it is non-prime HSS which is of the same general category of goods; downgrade is not of the same general category. The inconsistent treatment at paragraph 4.4.2.2 does not detract from that because it is paragraph 4.4.3.2 which contains the substantive treatment. In terms, paragraph 4.4.2.2 suggests that the information it is setting out comes from paragraph 4.4.3.2 (‘as detailed in section 4.4.3.2 below’). This suggests, and I find, that paragraph 4.4.2.2 should be subordinated to paragraph 4.4.3.2. Accordingly, the inconsistency is immaterial to the way paragraph 4.4.3.2 should be read.

80 A variation of this argument pursued fleetingly in the appeal was that the emphasised portion from the Final Report set out above at [48] showed that the Commissioner had applied his own standard, ‘the closest category of goods’, rather than the statutory standard, ‘the same general category of goods’. Read in the context of the surrounding paragraphs it is clear, I think, that the Commissioner was doing no such thing.

81 The primary judge was, therefore, correct to dismiss this argument.

6. Actual amounts: Ground 4

82 This ground concerns the calculation of the normal value of HSS sections exported to Australia which is governed by s 269TAC of the Act. It will be recalled that, ordinarily, the normal value of goods exported to Australia is ‘the price paid or payable for like goods sold in the ordinary course of trade for home consumption in the country of export in sales that are arms length’: s 269TAC(1).

83 Sometimes, however, it is not possible to determine such a figure. The volume of sales in the domestic market may be too low to allow for a meaningful comparison (as was the case in this appeal). Where this occurs, s 269TAC provides alternate ways of calculating the normal value. One such way is set out in subsection 269TAC(2)(c) which is set out above at [10]. It provides for the amount to be the sum of two figures. The first, which is not immediately relevant, is the amount determined by the Minister to be the cost of production or manufacture (s 269TAC(2)(c)(i)); the second, which is relevant, is a hypothetical amount. Subsection s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) requires the positing of a hypothesis which does not correspond to the real world. It is that the goods rather than being exported to Australia were instead sold for home consumption in the ordinary course of trade in the country of export. Having established that hypothesis, subsection 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) then requires the Minister to determine, first, the administrative, selling and general costs associated with the sale and, secondly, the profit on that sale. The effect of these provisions is that the Minister is required to determine the hypothetical profit on a hypothetical sale.

84 In conducting that hypothetical exercise, the Minister is constrained by the Regulation: reg 45. The general rule, set out in reg 45(2), is that the Minister in calculating these figures should ‘work out the amount by using data relating to the production and sale of like goods by the exporter or producer of the goods in the ordinary course of trade’. Of course, in this case that could not be done. This then brought into play reg 45(3) which is set out above at [64].

85 Reg 45(3)(a) requires the Minister to identify some actual real world amounts and these are those realised by the exporter or producer on the sale of the same general category of goods in the domestic market of the country of export.

86 It will be appreciated from the foregoing that this calculation is occurring in a context in which the profit on the sale of the goods is being used, in effect, as a proxy for the hypothetical sale of the exported goods in the domestic market.

87 The Appellants’ point related to how the Commissioner had gone about calculating the ‘actual amounts’ referred to in reg 45(3)(a).

88 The primary judge was told, and it was not in dispute, that the Commissioner had approached this issue by assessing the profit on the sale of XXXX tonnes of HSS. He did this by reference to the cost of production and sale in the review period. It was this to which the Appellants took objection. They contended that much of the HSS had not been produced during the review period but at an earlier time when production costs were higher. Because of that they submitted that assessing the amount of profit on the sales of HSS using the production costs prevailing in the review period artificially increased the amount of the profit.

89 To give this point under Ground 4 some rhetorical support, the Appellants noted that during the review period, whilst it was true that Dalian had sold XXXX tonnes of HSS, it had only in fact produced XXXX tonnes. The balance of XXXX tonnes could not have been produced in the review period.

90 The Appellants developed this ground of appeal as follows: first, the language of reg 45(3)(a) was ‘actual amounts realised’ and the use of the verb ‘identify’ required that those amounts actually be calculated; secondly, to do that the Commissioner had deducted the production costs for XXXX tonnes during review period from the actual sales of XXXX during the same period; thirdly, this was the identification of something other than ‘the actual amounts realised’.

91 The primary judge was not disposed to accept this argument. One of the difficulties his Honour noted was that Dalian’s records did not generally permit it to be ascertained when particular items of HSS were manufactured. An email from the Appellants’ agent dated 22 February 2016 said this: ‘For the vast majority of domestic sales, Dalian Steelforce has no way of identifying when the goods were produced’. The Appellants find themselves thus contending for a construction of reg 45(3)(a) which their own records cannot satisfy. The Appellants’ response to this problem was to point to the availability of reg 45(3)(c) which provides for an alternate methodology to reg 45(3)(a). It permits the Commissioner to do the assessment ‘using any other reasonable method and having regard to all relevant information’. However, reg 45(3)(c) is subject to the constraint in reg 45(4). It requires an assessment to be made of profits realised by other exporters as a cap. If the Commissioner is unable to determine the cap referred to in reg 45(4), then one view may be that the methodology in reg 45(3)(c) is not available because the limiting machinery of reg 45(4) cannot be applied. That was, in fact, the Commissioner’s view here: see Final Report at p 28. Of course, that fact is irrelevant to the construction issue which arises but the legal fact that the methodology in reg 45(3)(c) may not always be available is not irrelevant. I would decline to express a concluded view on whether it is correct that the methodology in reg 45(3)(c) cannot be applied if the cap in reg 45(4) cannot be determined. Resolution of that issue should await a case in which it is squarely raised.

92 I accept the Appellants’ basic point, however, that ‘actual amounts realised’ requires attention to a real world figure that was actually realised and that what the Commissioner did does not answer that description. I agree with the primary judge that the assessment of a constructed normal value under s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) does involve the assessment of a potentially hypothetical state of affairs. The hypothesis is that the exported goods are sold into the domestic market for home consumption in the ordinary course of trade. Section 269TAC(5B) requires, however, that assessment to be carried out in the manner prescribed by the regulations. Subregulation 45 is set out above at [64].

93 Whilst it is true that the inquiry in s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) is hypothetical, the methodologies for assessing that hypothesis are not hypothetical. Indeed, what reg 45 sets out is a range of real world proxies which can be determined and which are to stand in the place of, and provide the answer to, the hypothetical question posed by s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii). The primary rule (or proxy) is set out in reg 45(2). It is that the amount of profit is to be determined using data from the sale of like goods by the exporter. As I have already noted at [5], ‘like goods’ is defined in s 269T to mean ‘goods that are identical in all respects to the goods under consideration or that, although not alike in all respects…have characteristics closely resembling those of the goods under consideration’. There is nothing hypothetical about the assessment called for by reg 45(2). If like goods are sold in the domestic market and the data is available then reg 45(2) requires the profit to be determined on those actual sales of like goods. Thus although the inquiry called for by s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) is hypothetical in nature, the assessment of the relevant proxy is not hypothetical in that instance.

94 The same is true of the methodologies in reg 45(3)(a) and (b). These deal with two other proxies. The first, with which this case is concerned, is – unlike the sale of like goods considered under reg 45(2) – concerned with the sale of goods of the same general category. If goods of the same general category are sold in the domestic market, then reg 45(3)(a) calls for an assessment of the actual amounts realised on the sale of those goods. As with reg 45(2), this is not a hypothetical inquiry.

95 Again the same point may be made about reg 45(3)(b). It concerns, like reg 45(2), sales of like goods and appears to be applicable where the data referred to in reg 45(2) is not available. It permits the actual amount realised on the sale of the like goods instead to be calculated by reference to the amount for which those goods are sold by other exporters, i.e., yet another proxy.

96 Thus, while I agree with the learned primary judge that the enterprise erected by s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) is concerned with the assessment of a hypothetical amount, I do not accept that the methodologies set out in reg 45 are themselves hypothetical. To the contrary, they are real world figures which the Regulation, by selecting them as proxies for the amount in s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii), assumes can be assessed. Accordingly, I do not accept that the hypothetical nature of s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) allows one to approach the construction of reg 45(3)(a) more liberally.

97 In light of that, two factors compel me to the view that ‘actual amounts realised’ in reg 45(3)(a) requires the assessment of an actual amount not satisfied in this case. First, it is the ordinary meaning of the word ‘actual’. What was determined by the Commissioner in this case was an amount but it was not the actual amount realised. Secondly, to the extent that it turns out that the figure in reg 45(3)(a) cannot be ascertained and all of the other methodologies in reg 45 are unavailable (as was the case here), then the answer is that the Commissioner is unable to determine the figure under s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii). That precise situation is contemplated by s 269TAC(6) which explicitly provides a methodology where, inter alia, s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) has proven unable to be applied. There is no need to reach for a strained interpretation of ‘actual amounts realised’ in reg 45(3)(a) when that provision is available.

98 There are some other matters which tend in the same direction although they are not necessarily definitive. Subregulation 45(6), in a complex way, shows that reg 45(3) is very much concerned with the calculation of profit over defined periods. Subregulation 45(3)(b) calls for the ‘actual amounts realised’ to be determined by reference to a weighted average. It is clear from reg 45(6) that that is to be determined by the method in s 269T(5A). That section provides:

‘(5A) For the purposes of this Part, the weighted average of prices, values, costs or amounts in relation to goods over a particular period is to be worked out in accordance with the following formula:

P1, P2 … Pn means the price, value, cost or amount, per unit, in respect of the goods in the respective transactions during the period.

Q1, Q2 … Qn means the number of units of the goods involved in each of the respective transactions.’

99 It seems to me that this provision is focused on the determination of an actual amount realised in an actual defined period. An interpretation of reg 45(3)(b) of ‘actual amounts realised’ which allowed a departure from a period based assessment would most likely contradict s 269T(5A). It therefore cannot mean that in reg 45(3)(b). I see no reason why it would have a different meaning in reg 45(3)(a). The phrase ‘actual amounts’ can also be observed in reg 44(3) which, it will be recalled, the Commissioner applied when determining the administrative, selling and general costs incurred by Dalian in its production and sale of non-prime HSS product. It is difficult to see that ‘actual’ in reg 44 could mean other than actual. It would be surprising if the meaning varied as between reg 44 and 45.

100 Another important matter is the interpretation which has been given by the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organisation to the corresponding provision of the Agreement on the Implementation of Article VI of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994. Opened for signature 15 April 1994. 1868 UNTS 201. (entered into force 1 January 1995) (‘the Anti-Dumping Agreement’). Article 2.2.2 provides:

‘2.2.2 For the purpose of paragraph 2, the amounts for administrative, selling and general costs and for profits shall be based on actual data pertaining to production and sales in the ordinary course of trade of the like product by the exporter or producer under investigation. When such amounts cannot be determined on this basis, the amounts may be determined on the basis of:

(i) the actual amounts incurred and realized by the exporter or producer in question in respect of production and sales in the domestic market of the country of origin of the same general category of products;

(ii) the weighted average of the actual amounts incurred an realised by other exporters or producers subject to investigation in respect of production and sales of the like product in the domestic market of the country of origin.

(iii) any other reasonable method, provided that the amount for profit so established shall not exceed the profit normally realized by other exporters or producers on sales of products of the same general category in the domestic market of the country of origin.’

101 A significant matter is that the amounts being discussed in this Article and in reg 45(3)(a) do not exclude sales which did not occur in the ordinary course of trade or which arose from sales in markets which are not suitable for comparison purposes. Of course, one comes to be in these provisions via s 269TAC(2)(c)(ii) only because those situations have made assessing the normal value by reference to actual sales inappropriate. An argument was put in Appellate Body Report, European Communities – Anti-Dumping Duties on Imports of Cotton-type Bed Linen from India, WTO Doc WT/DS141/AB/R (1 March 2001) (‘the Bed Linen Case’) that there should be excluded from the sales considered under Art 2.2.2(ii) sales which were not in the ordinary course of trade. The Appellate Body rejected that argument saying this:

’80. Here, we note especially that Article 2.2.(ii) refers to “the weighted average of the actual amounts incurred and realized by other exporters or producers”. (emphasis added) In referring to “the actual amounts incurred and realized”, this provision does not make any exceptions or qualifications. In our view, the ordinary meaning of the phrase “actual amounts incurred and realized” includes the SG&A actually incurred, and the profits or losses actually realized by other exporters or producers in respect of production and sales of the like product in the domestic market of the country of origin. There is no basis in Article 2.2.(ii) for excluding some amounts that were actually incurred or realized from the “actual amounts incurred and realized”. It follows that, in the calculation of the “weighted average”, all of the “actual amounts incurred and realized” by other exporters or producers must be included, regardless of whether those amounts are incurred and realized on production and sales made in the ordinary course of trade or not. Thus, in our view, a Member is not allowed to exclude those sales that are not made in the ordinary course of trade from the calculation of the “weighted average” under Article 2.2.2(ii).’

[footnotes omitted]

This is not directly on point but it does rather suggest that reg 45(3) is concerned with actual amounts not hypothetical ones or estimates (I assume, without deciding, that the Bed Linen Case is a legitimate interpretive tool).

102 Accordingly, I conclude that reg 45(3)(a) is not satisfied in this case. What the Commissioner determined was not an actual amount realised. I accept that there may be real world problems in many industries in assessing what reg 45(3)(a) calls for although I would not accept this always to be so. Regardless, the answer to any such problem lies in s 269TAC(6).

103 As a result, I would allow the appeal on this ground. I do not think that it is possible to say that s 269TAC(6) applies because it requires the formation of a state of satisfaction which has not yet occurred. In its absence, it is not possible to decline relief on a discretionary basis. The report must therefore be set aside.

7. Determination of the cost of production: Ground 5

104 Before turning to the detail of Ground 5, it is necessary to understand the way in which the Commissioner determined the normal value of the HSS exported to Australia. This was regulated by s 269TAC of the Act which is set out above at [10].

105 The Commissioner determined that the circumstance set out in s 269TAC(2)(a)(ii) applied. That circumstance was that ‘because the situation in the market of the country of export is such that sales in that market are not suitable for use in determining a price under subsection (1)’. Subsection 269TAC(1), it will be recalled, required the normal value to be determined, if possible, by reference to arms length domestic sales for like goods in the ordinary course of trade. By reason of his determination under s 269TAC(2)(a)(ii), subsection 269TAC(1) did not apply. The reason the Commissioner accepted there was a ‘situation’ in the Chinese market was because of some prior findings in Investigation 177. That Investigation had considered the position of one of the inputs into the production of HSS called hot rolled coil (‘HRC’). HRC was produced in China by local steel manufacturers. The price of HRC in China was affected by a Chinese government program known as Program 20 which involved a subsidy which reduced the price of steel. The Commissioner concluded (in the Final Report) in light of that finding, that domestic selling prices were unsuitable for the purpose of determining a normal value.

106 The Commissioner resolved, therefore, to determine a constructed normal value under s 269TAC(2)(c). The first step in that process, it will be recalled, required him to determine:

‘Such amount as the Minister determines to be the cost of production or manufacture of the goods in the country of export’

(s 269TAC(2)(c)(i))

107 Subregulations 43(1) and 43(2) set out a methodology for doing this. They provided:

‘43 Determination of cost of production or manufacture

(1) For subsection 269TAAD(5) of the Act, this section sets out:

(a) the manner in which the Minister must, for paragraph 269TAAD(4)(a) of the Act, work out an amount (the amount) to be the cost of production or manufacture of like goods in a country of export; and

(b) factors that the Minister must take account of for that purpose.

(2) If:

(a) an exporter or producer of like goods keeps records relating to the like goods; and

(b) the records:

(i) are in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles in the country of export; and

(ii) reasonably reflect competitive market costs associated with the production or manufacture of like goods;

the Minister must work out the amount by using the information set out in the records.

…’

(The reference to the apparently irrelevant s 269TAAD is explained by a well-hidden cross-reference in s 269TAC(5A)(c)).

108 The Commissioner was satisfied, however, that the prices of HRC recorded in Dalian’s records did not, for the reasons just given, ‘reflect competitive market costs’. Consequently, that methodology could not be applied. He nevertheless determined to press on and to calculate the cost of production for the purposes of s 269TAC(2)(c)(i). An argument was faintly pressed in this Court that once he had found that reg 43 did not permit Dalian’s records to be used to assess the costs of production, he could not thereafter determine the cost of production under s 269TAC(2)(c)(i) and was required instead to use the methodology in s 269TAC(6). I do not accept that that is so. The methodology in reg 43 does not purport to be an exhaustive statement on the topic of how production costs are to be determined. It deals with just one situation, viz, that obtaining when, compendiously speaking, the producer’s records are adequate for task. Outside that situation, reg 43 is otherwise silent and s 269TAC(2)(c)(i) remains applicable on its own terms.