FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Virk Pty Ltd (in liq) v YUM! Restaurants Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 190

ORDERS

VIRK PTY LTD (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 132 822 514) Appellant | ||

AND: | YUM! RESTAURANTS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 000 674 993) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, to be taxed if not agreed.

3. There be liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 On 4 June 2014, the respondent, YUM! Restaurants Australia Pty Ltd (Yum), the franchisor of the Pizza Hut franchise in Australia, decided to adopt a business strategy called the “Value Strategy” (the Value Strategy or VS). This strategy comprised various different measures including, significantly for present purposes, reducing the number of ranges of pizzas from four to two, and reducing the prices for the two remaining ranges such that the price for “Classics” pizzas would be reduced from $9.95 to $4.95, and the price for “Favourites” pizzas (formerly called “Legends” pizzas) would be reduced from $11.95 to $8.50. The Classics range of pizzas comprised about half of all pizzas sold by Pizza Hut. The new prices would apply both to pick up (or take-away) pizzas and to delivered pizzas (with an additional charge for delivery in the latter case). The Value Strategy would apply to 300 out of a total of 307 Pizza Hut outlets in Australia.

2 On 10 June 2014, Yum announced the Value Strategy to the franchisees. In so doing, it exercised its contractual power to set maximum prices for pizzas, and certain other powers, under the franchise agreement it had with each franchisee (the International Franchise Agreement or IFA). The Value Strategy was due to be implemented on 1 July 2014. Many Pizza Hut franchisees were bitterly opposed to the Value Strategy. They complained that they would not be able to survive financially if it were implemented. Indeed, certain franchisees sought an interlocutory injunction to prevent the strategy being implemented. The application for an injunction was heard on 24 June 2014 and dismissed that day.

3 On the same day, 24 June 2014, and before Pizza Hut had announced to the market that it would be implementing the Value Strategy, Pizza Hut’s main competitor, Domino’s Pizza Enterprises Limited (Domino’s), announced that it would be offering a $4.95 every day price point. Unlike Pizza Hut’s Value Strategy, however, Domino’s $4.95 price applied only to take-away pizzas. Domino’s announcement pre-empted the Value Strategy and, on one view, meant that Pizza Hut lost the ‘first mover advantage’.

4 The proceeding below was commenced by Diab Pty Limited (DPL), a franchisee, as the representative applicant of all persons who were franchisees under an International Franchise Agreement with Yum to operate Pizza Hut outlets in Australia as at 1 July 2014 (Franchisees). DPL contended that Yum breached contractual duties, including implied terms, in adopting the Value Strategy and setting the new prices. DPL also contended that Yum was liable in negligence and had engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to statutory provisions.

5 DPL’s case at first instance failed: Diab Pty Ltd v YUM! Restaurants Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 43 (the Reasons). The primary judge made a number of important findings that were adverse to DPL’s case. In particular, her Honour found that “Yum and, in particular Mr Houston [the General Manager of Pizza Hut South Pacific], carefully considered the appropriate maximum price taking into account that it was part of an overall strategy” (Reasons, [363]). Her Honour held that “DPL [had] not established that Mr Houston acted dishonestly or in bad faith or with reckless disregard for the Franchisees” (Reasons, [363]). The primary judge found that, although Mr Houston may have demonstrated poor business judgment, particularly with the benefit of hindsight, “that does not equate to a lack of fidelity to the bargain or to unconscionable behaviour”; and that Mr Houston “made what he considered to be the best decision from the point of view of Yum and the future profitability of the Franchisees” (Reasons, [368]). Further, her Honour found that Mr Houston clearly believed, “rightly or wrongly but reasonably, that once Domino’s offered an everyday $4.95 pizza, Pizza Hut had no choice but to implement the VS” (Reasons, [368]).

6 DPL subsequently resolved its dispute with Yum.

7 The appellant, Virk Pty Ltd (in liq), another franchisee, brings this appeal as a representative party or sub-group representative party pursuant to s 33ZC of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). By its notice of appeal, the appellant challenges a number of factual findings made by the primary judge. The appellant does not, however, challenge any of the primary judge’s findings as to the subjective state of mind of any officer of Yum. This was reflected in paragraph 3 of orders made on 10 March 2017. That paragraph (made with the appellant’s consent) stated that, without leave of the Court, the appellant may not raise any issue on the appeal as to the subjective state of mind of any officer of Yum. The appellant confirmed its position in its oral and written submissions. The appellant challenges the primary judge’s conclusions as to whether Yum breached the contractual duties it owed to Franchisees. Broadly speaking, the appellant contends that a tort-like test of reasonableness is to be implied into the International Franchise Agreements between Yum and the Franchisees, and that the primary judge ought to have found that Yum failed to act reasonably in this sense in adopting the Value Strategy and setting the maximum prices. Further, the appellant contends that the primary judge erred in not concluding that Yum was liable in negligence and for unconscionable conduct.

8 Yum has filed a notice of contention. Yum contends that the decision of the primary judge should be affirmed on grounds other than those relied on by the primary judge. In summary, it contends that:

(a) first, to the extent that the primary judge found that, in setting maximum prices under the International Franchise Agreement, the prices should be reasonably capable of allowing Franchisees to make profits (Reasons, [359]-[360]), the primary judge should have held that Yum was under no obligation other than to exercise that power in good faith and for a proper purpose;

(b) secondly, to the extent that the primary judge found that the object of the International Franchise Agreement was to enable Franchisees reasonably to have the opportunity to run a profitable operation (Reasons, [354]), the primary judge should have found that the object of the agreement was to permit the Franchisees to participate in a unique and valuable franchise system devised by Yum and its affiliates for the preparation, marketing and sale of pizzas and other food products; and

(c) thirdly, to the extent that the primary judge found an implied term of reasonableness formed part of the contract between Yum and its Franchisees (Reasons, [360]), the primary judge should have held that there was no such implied term.

9 For the reasons that follow, we would dismiss the appeal. In relation to the notice of contention, we would uphold ground 1; we do not consider it necessary to determine ground 2; and we would dismiss ground 3.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

10 The following summary of the factual background is based on the facts found in the Reasons, as supplemented by documentary evidence to which we were taken in the course of the appeal hearing. In some instances, we have also included extracts from some of the affidavit evidence to which we were taken during the appeal hearing, in order to indicate part of the context for her Honour’s evaluation of the material, which is set out later in these reasons.

Findings on credibility of witnesses

11 It is convenient to note, at this stage, the findings her Honour made about the evidence of the lay witnesses. At trial, DPL called Danny Diab, the majority shareholder and managing director of DPL. Yum called the following personnel, who were involved in the launch of the Value Strategy:

(a) Graeme Houston, who was employed by Yum as the General Manager of Pizza Hut South Pacific;

(b) Lynne Broad, who was employed by Yum as the Head of Finance and Supply Chain, Pizza Hut;

(c) Kurtis Smith, who was employed by Yum in July 2013 as the Head of Operations of Pizza Hut South Pacific (until January 2014, when he became the Market Director for Pizza Hut in Australia, a position that he held until January 2015);

(d) Fatima Kamali-Syed (Ms Syed), who was employed by Yum as the Head of Marketing; and

(e) Devesh Sinha, who was employed by Yum as the National Operations Manager from January 2014 until 15 July 2015.

12 Her Honour made the following findings in relation to their evidence, at [427]-[434] of the Reasons:

427 I accept that, in giving his evidence, Mr Diab gave truthful evidence. He gave his evidence clearly and of the matters of which he had knowledge and an opinion. Mr Diab is a very experienced and successful Pizza Hut Franchisee. Mr Diab had strong views on certain matters and was entitled to express those views, in particular as to the VS from his perspective. There was no reason to doubt Mr Diab’s integrity.

428 DPL severely criticised the Yum witnesses.

429 The Yum witnesses are not entrepreneurs. They work for a large organisation in a highly competitive area. Some, like Mr Sinha, have worked in Pizza Hut for a long time and have worked their way up through more senior levels in the organisation. DPL attacked the Yum witnesses’ character and their evidence.

430 I do not propose to canvass each and every question and answer. I have dealt with Mr Sinha’s evidence. While he may not have had the skills to develop something called a “model”, as an accounting tool, he worked on it to the best of his ability and gave reasons for his final inclusion of the 13 additional labour hours.

431 It was put to Ms Broad that she reconstructed her evidence, in particular as to matters that occurred after she expressed disagreement with the proposed strategy and the ACT Test results. I accept that Ms Broad believed in the accuracy and honesty of her calculations as to the ACT Test at the time and that she had a basis for the inclusion and exclusion of data even though she accepted in cross-examination that some of those bases could be considered to be flawed. That acceptance does not really affect the outcome because the ACT Test results were only one factor in the preparation of the Yum Model and the decision to implement the VS.

432 The least satisfactory witness was Ms Syed who, it seemed, had not monitored Domino’s response in the ACT and then, in evidence, gave unconvincing explanations of how it was that she did not know of Domino’s television advertising for 5 weeks. However, she notified the Yum leadership team of those advertisements on 13 June 2014. When Mr Houston made his decision to implement the VS, he was fully conscious of Domino’s likely immediate response. It is not apparent that after Domino’s launched, whether or not they advertised made any difference to the decision to implement the VS, or would have made a difference to the earlier decision to implement that was interrupted by the interlocutory proceeding.

433 I accept Mr Houston’s evidence. He also gave truthful evidence to the best of his ability. The most that can be said against Mr Houston is that others may not have agreed with his business judgment, but that does not mean that the decisions that he made lacked a reasonable foundation or were wrong.

434 DPL strongly attacked the credit of Mr Smith and it submits that Yum seeks to avoid a finding that Mr Smith gave inaccurate and untruthful evidence to Jagot J [in connection with the interlocutory injunction application] that the form of the Yum Model attached to his affidavit of 23 June 2014 was the model on which Yum had relied to formulate the VS. I do not need to make a determination about the credit of Mr Smith and have not placed reliance on Mr Smith’s evidence unless it was a matter to which other witnesses referred.

(Emphasis added.)

13 As noted above, the appellant does not challenge any of the primary judge’s findings as to the subjective state of mind of any officer of Yum. Nor does the appellant challenge the primary judge’s findings regarding the credibility of the witnesses.

Yum

14 At all relevant times, Yum was an Australian subsidiary of Yum! Brands, Inc. (Yum US), which is a publicly listed company on the New York Stock Exchange and among the world’s top 250 companies on the Fortune 500 list. Yum operated the Pizza Hut business in Australia.

15 Mr Houston had been a director of Yum since 21 December 2011. Ms Broad became a director in December 2014. At the time of the trial, Mr Smith and Mr Sinha no longer worked for Yum; however, both had roles in Yum US’s Dallas headquarters. Mr Smith was the Senior Director of Development of the USA Pizza Hut business and Mr Sinha was the Senior Manager of Operations for what was described at trial as Pizza Hut Global.

16 Mr Houston gave evidence (and, we infer, the primary judge accepted) that, as at 27 November 2014, there were approximately 210 Pizza Hut franchisees in Australia. Of these, approximately 45 franchisees operated more than two outlets and approximately four franchisees operated more than five outlets.

17 In terms of its own financial reporting cycle, Yum provided quarterly reports to the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of Pizza Hut Global, Enrique Ramirez, commencing each year with a forecast known as Q0F, which was then updated in subsequent periods by forecasts known as Q1F, Q2F and Q3F. Ms Broad gave evidence (and, we infer, her Honour accepted) that these forecasts were then built into a consolidated forecast for the Pizza Hut business as a whole.

18 Yum commenced this process in about July of each year when Yum, with every other business unit that was a subsidiary or related entity around the world, submitted a market growth plan. This plan outlined store build and profit targets, which were agreed with the Pizza Hut Global CFO. In about October of each year, there was a conference between Yum’s leadership team and the Yum US senior leadership team. During this conference, Yum presented its business strategy, known as the Annual Operating Plan, to the Yum US senior leadership team. The meeting for the 2014 year took place on 9 October 2013.

Yum personnel

Mr Houston

19 At the relevant times, Mr Houston was employed by Yum as the General Manager, Pizza Hut South Pacific. He had held this position since 2011.

20 Mr Houston was awarded a Bachelor of Commerce from Canterbury University in New Zealand in 1986. He had been employed by Yum, or its related entities, since 1990. His various roles included:

(a) From 1990 to 1994, he held various Area Manager positions in Auckland and Dunedin in New Zealand and Wollongong, New South Wales in KFC Operations (which was a division of Yum at the time of trial). At that time, KFC was part of PepsiCo International.

(b) In 1994, he was promoted to the position of Operations Manager New South Wales KFC.

(c) In 1995, he was promoted to Market Manager for Pizza Hut New Zealand. This was the most senior position in Yum based in New Zealand.

(d) In 1997, Mr Houston was promoted to Market Manager KFC Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, where he was responsible for 90 company owned restaurants and 48 franchised outlets.

(e) In 2002, he was promoted to Chief Supply Chain Officer for both KFC and Pizza Hut, based in Sydney. In that role he reported to the Managing Director, Yum South Pacific.

(f) In 2003, Mr Houston became the General Manager, Pizza Hut Operations South Pacific, in which he led the Operations team for Pizza Hut in Australia and New Zealand.

(g) In 2006, Mr Houston became the Vice President of Pizza Hut Delivery Operations of Yum! Restaurants International (which was a division of Yum US). Mr Houston was responsible for developing the Pizza Hut delivery business for all countries in which Pizza Hut did business except the USA and China. He held this position until 2011. During this period, Mr Houston also participated in the Global Pizza Hut Brand Council, which was an annual meeting of ‘key thought leaders’ from the global Pizza Hut brand to help develop and refine the Pizza Hut brand strategy.

21 In 2013, Mr Houston also assumed responsibility for establishing and developing the Pizza Hut brand in Russia. This role was expanded in 2014, as Pizza Hut Africa was added to his portfolio.

Ms Broad

22 At the time of trial, Ms Broad was employed by Yum as the Head of Finance & Supply Chain, Pizza Hut and had held this position since the middle of 2013. She reported to Mr Houston. Ms Broad had previously held the position of Head of Finance since January 2011. Ms Broad commenced employment with Yum in April 2007 and had held the following roles: Group Taxation & Treasury Manager, Finance Manager and Commercial Planning Manager. Ms Broad was awarded a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Sydney and a Graduate Diploma from the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia. At the time of trial, Ms Broad was a director of Yum (having been appointed to this position in December 2014).

Ms Syed

23 At the time of trial, Ms Syed was the Head of Marketing of Yum and a member of the Leadership Team. Ms Syed had held these positions since January 2013. She had seven employees in her team, five in the Marketing Team and two in the Research and Development Team. Brad Richter was the Marketing Manager and the most senior person reporting to Ms Syed. Ms Syed began working for Yum in November 2010 as the Group Marketing Manager.

24 Ms Syed was awarded a Bachelor of Business by the University of Technology, Sydney, in 2000 and was awarded a Masters of International Business from the University of Sydney in 2001. At the time of trial, she had worked as a marketing professional in Australia for 12 years, in the following roles:

(a) Assistant Brand Manager at Nestlé Australia Ltd from 2002 to 2004.

(b) Brand Manager at Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Australia Pty Limited from 2004 to 2006.

(c) Brand Manager at PepsiCo Australia and New Zealand from 2006 to 2008 and Senior Brand Manager from 2008 to 2010.

(d) Group Marketing Manager at Yum from 2010 to 2012.

Mr Sinha

25 Mr Sinha was the National Operations Manager of Yum from January 2014 until 15 July 2015.

26 Mr Sinha had extensive work experience before joining Yum, including:

(a) From 1994 to 1995, he was a Hotel Operations Management Trainee at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, India.

(b) From 1995 to 1996, he was the Managing Partner of Zodiac – Multicuisine Restaurant in India.

(c) From 1996 to 1998, he was the Executive of Hotel Services at Eurest Radhakrishna Hospitality Services Pvt Ltd in India.

(d) From 1998 to 2000, he was a District Manager of Domino’s Pizza India.

27 Mr Sinha first worked in the Pizza Hut system in India in 2000 as the Restaurant General Manager for Favorite Food India (which was a subsidiary of Wybridge, the Master Franchisor for Pizza Hut in Indonesia), where he opened and managed Pizza Hut stores in Mumbai. In that capacity, Mr Sinha had personal experience in making, and supervising the making of, pizzas in a Pizza Hut store. In the period from 2000, Mr Sinha had many roles associated with the Pizza Hut business. These included:

(a) In 2002, he was the Area Coach in Wellington for Restaurant Brands New Zealand Limited (RBNZ), the New Zealand Pizza Hut master franchisee. In this role, he managed the operation of the Pizza Hut stores. He stayed at RBNZ until 2006.

(b) From 2006 to 2009, he held the position of Franchise Business Coach and EDI Operations Leader for Yum! Restaurants International in India.

(c) From 2009 to 2011, he was the Area Manager of Southern Restaurants Pty Ltd in Melbourne, Victoria.

(d) In 2011, he became the Pizza Hut State Operations Manager for New South Wales with Yum.

28 In January 2014, Mr Sinha was promoted to National Operations Manager. Each State Operations Manager reported directly to him and the operations team was responsible for maintaining operational standards across all Pizza Hut stores in Australia. Mr Sinha reported directly to Mr Smith. Mr Sinha had the overall responsibility for all operational matters that affected customers, including such matters as food preparation, food and operational safety, and customer service.

Mr Smith

29 At the time of the interlocutory injunction hearing (ie, 24 June 2014), Mr Smith was employed as the Market Director by Yum, a position he had held since January 2014. The role required him to oversee day-to-day operations at Pizza Hut Australia, reporting to Mr Houston.

30 At the time of trial, Mr Smith was the Senior Director of Development in the Pizza Hut USA business and had held that position since January 2015.

31 Mr Smith was awarded a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration, majoring in accounting, from the University of Richmond, in Virginia in the USA, in 2002. Further, in 2007, he was awarded a Masters of Business Administration from the University of Chicago – Booth School of Business.

32 Mr Smith’s professional background was as follows:

(a) From 2002 until 2005, Mr Smith worked as an Associate at Deloitte.

(b) From 2006 to 2009, he was a consultant at Bain & Company.

(c) From December 2009 until October 2010, he was the Senior Manager, Strategy, at Hewlett Packard.

(d) Between October 2010 and July 2013, Mr Smith was employed by Yum! Restaurants International. He held a range of positions including Manager, Strategic Planning (from October 2010 to June 2011), Senior Manager, Strategic Planning (from June 2011 to December 2011) and Director, Financial and Capital Planning (from January 2012 to July 2013).

33 Mr Smith joined Yum in July 2013 as the Head of Operations, Pizza Hut South Pacific.

The International Franchise Agreement

34 Each Franchisee executed a franchise agreement with Yum in materially the same terms (referred to in these reasons as the International Franchise Agreement or IFA). The agreement was for a term of 10 years with a right of renewal for a further 10 years, subject to certain conditions of compliance (clause 18). The agreement provided, in clause 14, that the Franchisee could not sell or transfer any interest in the agreement without Yum’s prior written approval of the proposed transferee.

35 Clause 1.1 provided that Yum granted to the Franchisee the right to use a comprehensive system for the preparation, marketing and sale of food products (the System). By clause 1.2, the Franchisee agreed to use its best endeavours to develop the Business (defined, in summary, as the business of preparing, marketing and selling approved products) and to increase the Revenues (defined, in summary, as the gross receipts received by the Franchisee as payment for the sale of approved products and for all other goods and services). By clause 2.3, the initial and annual payments made by the Franchisee were in consideration solely for the rights granted in clause 1.1 and not for Yum’s performance of any specific obligations or services.

36 The International Franchise Agreement included the following provisions. We set these out at some length in order to provide context for the issues arising on the appeal.

BACKGROUND FACTS

Franchisor and/or its Affiliated Companies have developed a unique and valuable system for the preparation, marketing and sale of certain quality food products under various trade marks, service marks and trade names owned by them.

The System is a comprehensive restaurant system for the retailing of a limited menu of uniform and quality food products, emphasising prompt and courteous service in a clean and wholesome atmosphere which is intended to be particularly attractive to families. The foundation and essence of the System is the adherence by franchisees to standards and policies providing for the uniform operation of all restaurants within the System including, but not limited to, serving designated food and beverage products; the use of only prescribed equipment and building layout and designs; and strict adherence to designated food and beverage specifications and to prescribed standards of quality, service and cleanliness in restaurant operations. Compliance by franchisees with the foregoing standards and policies in conjunction with the trademarks, service marks and trade names provides the basis for the valuable goodwill and wide acceptance of the System. Moreover, Franchisee’s performance of the obligations contained in this agreement, and adherence to the tenets of the System constitute the essence of the license provided for herein.

Franchisor is entitled to grant to third parties, and has agreed to grant to Franchisee, the right to use the System, the System Property and the Marks on the terms and conditions of this Agreement.

In this Agreement, capitalised terms have the meanings specified in Schedule A, site-specific information and financial terms are set forth in Schedule B, and contractual modifications and amendments are set forth in Schedule C.

THE PARTIES AGREE:

1. GRANT OF FRANCHISE

1.1 Franchisor grants to Franchisee the right to use the System, the System Property and the Marks for the Term solely in connection with the conduct of the Business at the Outlet and subject to the terms and conditions of this Agreement.

1.2 At all times during the Term, Franchisee will use its best endeavours to develop the Business and to increase the Revenues.

…

1.4 No exclusive territory, protection or other right in the contiguous space, area or market of the Outlet is expressly or impliedly granted to Franchisee. Franchisor reserves the right to use, and to grant to other parties the right to use, the Marks, the System and the System Property or any other marks, names or systems in connection with any product or service (including, without limitation, the Approved Products) in any manner or at any location other than the Outlet. Franchisee acknowledges that, as at the Date of Grant, Franchisor and its Affiliated Companies and franchisees operate Outlets conforming to the Concept and also operate other systems for the sale of food products and services which may be competitive with the System and may compete directly with the Business.

2. INITIAL FEE AND CONTINUING FEE

…

2.2 On or before each Due Date, Franchisee will pay the Continuing Fee to Franchisor. Each payment of the Continuing Fee will be accompanied by a statement of the Revenues for the relevant Accounting Period, in the form required by Franchisor from time to time.

2.3 Franchisee’s payments pursuant to Clauses 2.1 and 2.2 are in consideration solely for the grant of rights in Clause 1.1 and not for Franchisor’s performance of any specific obligations or services.

3. MANUALS AND STANDARDS

3.1 At all times during the Term, Franchisee must comply with all of·the Standards and the Manuals and all applicable laws, regulations, rules, by-laws, orders and ordinances in its conduct of the Business. The Manuals are incorporated by reference into this Agreement. To the extent of any inconsistency between any provision of the Manuals and any provision of this Agreement, the provisions of this Agreement will prevail.

3.2 Franchisor may at any time change any of the Standards or Manuals or introduce new Standards or Manuals by giving notice to Franchisee. Franchisor will specify in the notice a period reflecting the nature of the change to the Standards or Manuals or the nature of the Standards or Manuals to be introduced, within which the new Standards or Manuals must be implemented. Franchisee acknowledges and agrees that such changes to, or introductions of, the Standards or Manuals, will bind Franchisee upon receipt of Franchisor’s notice as provided in Clause 22 and Franchisee will implement such changes or introductions within the period specified in the notice. In the event of any inconsistency between the Franchisor’s version and the Franchisee’s version of the Manuals, the Franchisor’s version will prevail.

…

4. UPGRADES

Franchisor may, by notice to Franchisee, at any time require Franchisee to upgrade, modify, renovate or replace all or part of the Outlet or any of its fittings, fixtures or signage or any of the equipment, systems or inventory used in the Outlet, in order to procure compliance by Franchisee with the Standards and the Manuals, and Franchisee acknowledges and agrees that such upgrades, modifications, renovations or replacements may require significant capital expenditures and/or periodic financial commitments by Franchisee. In its notice to Franchisee, Franchisor will specify a period reflecting the nature of the upgrade, modification, renovation or replacement, within which the upgrade, modification, renovation or replacement must be implemented and Franchisee will comply with the implementation period specified in the notice.

5. APPROVED PRODUCTS AND SUPPLIES

5.1 Franchisee will not prepare, market or sell any product or service other than the Approved Products or conduct any business other than Business at the Outlet without Franchisor’s prior written approval. Franchisor will from time to time notify Franchisee of the Approved Products and will specify those of the Approved Products which must be offered for sale at the Outlet as permanent menu items and at what times.

5.2 Franchisor may, by notice to Franchisee, at any time change or withdraw any Approved Product or add new Approved Products. Franchisee will implement such changes, withdrawals and additions within the period specified in the notice.

5.3 Franchisee will purchase the supplies, materials, equipment and services used in the Business exclusively from suppliers and using distributors who have been approved in writing by Franchisor prior to the time of supply and distribution in accordance with the approval procedures in the Manuals. Franchisee will not have any claim or action against Franchisor in connection with any non-delivery, delayed delivery or non-conforming delivery of any supplier or distributor whether or not approved by Franchisor.

6. ADVERTISING

6.1 Franchisee will not execute or conduct any advertising or promotional activity in relation to the Business or the System without Franchisor’s prior written approval.

6.2 Franchisee will participate in such national and regional advertising, promotions, research and tests as Franchisor from time to time requires and Franchisee will not have any claim or action against Franchisor in connection with the level of success of any such advertising, promotion, research or test.

6.3 Franchisee will spend, in the manner directed by Franchisor in writing from time to time, an amount not less than the Advertising Contribution on advertising, promoting, marketing and researching the products and services of the Business and the System. Franchisor may at any time during the Term direct Franchisee:

(a) to pay all or part of the Advertising Contribution to a national or regional co-operative advertising/marketing fund specified by Franchisor; or

(b) to spend all or part of the Advertising Contribution on such local or regional advertising, promotional and research expenditures as are approved by Franchisor, in accordance with the requirements and guidelines set out in the Manuals, provided that if Franchisee fails to spend the full amount as directed by Franchisor, Franchisee will pay the unspent amount to Franchisor within the period specified in a written demand from Franchisor. Upon receipt of the unspent amount, Franchisor either will contribute the amount to an applicable national or regional co-operative advertising/marketing fund or will spend the amount on national or regional advertising, promotions or research conducted by Franchisor in its discretion.

…

15. DEFAULT AND TERMINATION

15.1 Franchisor may terminate this Agreement by notice to Franchisee effective upon receipt by Franchisee of the notice, and/or adopt any of the remedies specified in Clause 15.2, if any of the following events occur:

(a) Franchisee is unable to pay its debts as and when they become due or becomes insolvent or a liquidator, receiver, manager, administrator or trustee in bankruptcy (or local equivalent) of the Franchisee or the Business is appointed, whether provisionally or finally, or an application or order for the winding up of Franchisee is made or Franchisee enters into any composition or scheme of arrangement;

…

(f) Franchisee abandons or ceases to operate the Business for more than 3 consecutive days without Franchisor’s prior written approval, provided that such approval will not be unreasonably withheld by Franchisor where the abandonment or cessation is caused by war, civil commotion, fire, flood, earthquake, act of God, industrial action or unrest which Franchisee has used best endeavours to prevent and remedy, or any other cause beyond Franchisee’s reasonable control;

…

(i) Franchisor notifies Franchisee that Franchisee or any Guarantor has breached any term or condition of this Agreement (other than Clauses 1.3, 5.1, 8, 9, 13 and 14) or any other agreement between Franchisor and Franchisee and/or any Guarantor (or their respective Affiliated Companies) relating to the Business and Franchisee or the Guarantor does not fully cure the breach to Franchisor’s satisfaction within the cure period which is specified by Franchisor in the notice as reflecting the nature of the breach; or

(j) Franchisee or any Guarantor breaches any term or condition of this Agreement (other than Clauses 1.3, 5.1, 8, 9, 13 and 14) or any other agreement between Franchisor and Franchisee and/or any Guarantor (or their respective Affiliated Companies) relating to the Business in circumstances where, in the preceding 24-month period, Franchisee has been sent 2 notices pursuant to Clause 15.1(i), whether or not Franchisee or the relevant Guarantor cured the prior breaches to Franchisor’s satisfaction.

…

15.3 Without limiting Clause 15.2, if any of the events specified in Clause 15.1 occur, Franchisor may, in addition and without prejudice to its rights under Clause 15.1, take control of the Business for such period as Franchisor considers appropriate, for the purpose of rectifying any breach of this Agreement and retraining Franchisee and/or Franchisee’s employees at Franchisee’s cost, such cost to be payable by Franchisee within the period specified in a written demand from Franchisor. During this period, Franchisee and its employees must continue to attend the Outlet to perform their responsibilities in the conduct of the Business, but subject to the directions of Franchisor. Any obligations, liabilities or costs incurred in respect of the Business during this period will be Franchisee’s responsibility and the indemnity in Clause 12.2 will apply. Franchisee agrees that the provisions of Clause 17 will also apply in respect of any entry into the Outlet by Franchisor pursuant to this Clause.

…

16. CONSEQUENCES OF TERMINATION

16.1 Immediately upon the expiration or termination of this Agreement, Franchisee will:

(a) pay all amounts owing to Franchisor;

(b) discontinue all use of the Marks and the System Property and otherwise cease holding out any affiliation or association with Franchisor or the System unless authorised pursuant to any other written agreement with Franchisor;

(c) dispose of all materials bearing the Marks and all proprietary supplies in accordance with Franchisor’s instructions; and

(d) if Franchisor so requires, de-identify the Outlet in accordance with Franchisor’s instructions.

…

16.3 For 60 days from the termination of this Agreement, Franchisor will have the option to purchase, or to nominate a third party to purchase, any of the supplies held by Franchisee at cost price and any of the equipment or signage at the Outlet at a price equal to book value less depreciation or as otherwise agreed, and free of any charges or other security interests.

…

23. MISCELLANEOUS

23.1 This Agreement constitutes the entire agreement between the parties with respect to its subject matter and supersedes all prior negotiations, agreements or understandings.

23.2 Franchisee is an independent contractor and is not an agent, representative, joint venturer, partner or employee of Franchisor. No fiduciary relationship exists between Franchisor and Franchisee.

…

FRANCHISEE’S REPRESENTATION

Franchisee represents to Franchisor that:

(a) Franchisee has reviewed this Agreement with the assistance and advice of independent legal counsel and understands and accepts the terms and conditions of this Agreement;

(b) Franchisee has relied upon its own investigations and judgment in entering this Agreement, after receiving legal and financial advice, and no inducements, representations or warranties other than those expressly set forth in this Agreement, have been given in respect of the System, the Business or this Agreement; and

(c) Franchisee acknowledges that establishment and operation of the Business will involve significant financial risks and that the success of the Business will depend upon the skills and financial capacity of Franchisee and also upon changing economic and market conditions and that such risks, skills and conditions are not in any way guaranteed or underwritten by Franchisor.

…

SCHEDULE A – DEFINITIONS

…

Approved Products means the products from time to time approved by Franchisor for sale in the Business.

Business means the business of preparing, marketing and selling the Approved Products under the Marks at the Outlet pursuant to this Agreement.

…

Manuals means the manuals, notices and correspondence published or issued from time to time by Franchisor in any form, containing the Standards and other requirements, rules, procedures and guidelines relating to the System.

…

Outlet means the outlet conforming to the Concept at the address specified in Schedule B.

…

Revenues means all gross receipts received by Franchisee as payment for the Approved Products and for all other goods and services sold at or from the Outlet or the Business and all service fees but excludes sales or other tax receipts required by law to be remitted, and in fact remitted by Franchisee, to any government authority and no adjustment for cash shortages from cash registers will be made.

Standards means the standards, specifications and other requirements of the System as determined, changed or added to by Franchisor from time to time, including, without limitation, the standards, specifications and other requirements related to the preparation, marketing and sale of the Approved Products, customer service procedures, the design, décor and fit-out of the Outlet, the equipment at the Outlet, and the content, quality and use of advertising and promotional materials.

…

SCHEDULE B – INFORMATION SCHEDULE | ||

Advertising Contribution: (Clause 6) | 6% of Revenues to be spent as follows until otherwise directed by Franchisor pursuant to Clauses 6.3 and 6.4: • 5.5% of Revenues (plus GST) to be paid by Franchisee to Pizza Hut Adco Limited on or before each Due Date; and • 0.5% of Revenues to be spent by Franchisee on local advertising and promotions approved by Franchisor in each Accounting Period | |

… | ||

Continuing Fee: | 6% of Revenues (plus GST) | |

… | ||

Initial Fee: (Clause 2.1) | US$23,850 to be adjusted for US CPI on 1 April each year and converted to AUD$ equivalent at the exchange rate quoted by Westpac on 1 April of each year (plus GST) being at the Date of Grant AUD$25,135 (including $2,285 GST) | |

… | ||

Renewal Fee: (Clause 18(h)) | US$11,925 to be adjusted for US CPI on 1 April each year and converted to AUD$ equivalent at the exchange rate quoted by Westpac on 1 April of the year of the commencement of the Renewal Term (plus GST) | |

… SCHEDULE C – ADDITIONAL PROVISIONS OF FRANCHISEE AGREEMENT | ||

C1. | MAXIMUM RETAIL PRICE Franchisee will not permit any Approved Products to be sold at the Outlet at any price exceeding the maximum retail prices advised by Franchisor to Franchisee from time to time. | |

… | ||

C12. | UPGRADES Subject to the renewal criteria of Clause 18 and Schedule B, when determining the period of implementation specified in notices issued by Franchisor pursuant to Clause 4, Franchisor will take into account the rate of implementation of the upgrade by Franchisor and its Affiliated Companies in their company-owned outlets and will not require Franchisee to implement the upgrade at a faster pace. | |

37 Although it would appear not to matter for the purposes of the appeal, we note that, on the hearing of the appeal, there was a difference of position between the parties as to the source of the power to set maximum prices that was utilised by Yum in connection with the Value Strategy. On the one hand, the appellant contended (T12-T14, T275-T276) that the source was clause C1 of Schedule C (albeit that the term is expressed as a negative obligation on the Franchisee not to sell products at a price exceeding the maximum price set by Yum). On the other hand, Yum contended (T245) that the source of the power was clause 3 combined with the definition of “Manuals”. We note that another potential source of power was clause 6.2, which dealt with promotions.

Adco

38 Pizza Hut Adco Limited (Adco), in conjunction with Yum, was responsible for marketing and promotional activities and promoting the Pizza Hut business, brands and products in Australia.

39 Adco was established in 1998. Mr Houston described it as “a forum that allowed franchisees to have input into how the Advertising Contribution was spent and provided a mechanism for Yum to consult with franchisees, through their elected representatives, on marketing”. On 9 May 2013, at an Adco meeting, the Adco directors resolved to increase the marketing services administration fee, to have effect on 1 December 2013. Minutes of the meeting show that Mr Diab voted in favour of the resolution and that two of the Franchisees’ Adco directors voted against it. Mr Houston gave evidence (which, we infer, the primary judge accepted) that he knew of no challenge to the accuracy of those minutes.

40 Another meeting of the directors of Adco was scheduled to take place on 18 February 2014. Prior to the meeting, DPL sought some alterations to the terms proposed by Yum in an updated marketing agreement. In particular:

(a) On 30 October 2013, DPL sought clarification of whether the fee Adco would pay to Yum was on the basis of net contributions (which allowed for bad debts) or gross contributions. DPL preferred net contributions.

(b) On 16 December 2013, DPL sought the inclusion of a term that “any recommendation of regular and promotional pricing for PIZZA HUT products must have the unanimous support of all Adco board of directors”.

41 Neither of these proposed concessions was incorporated by Yum into the draft of the updated marketing agreement. Yum said at trial that it did not agree to the changes for the following reasons:

(a) Administratively, it would not be able to execute the change to the clause regarding net contributions and Yum disagreed with the suggestion in principle.

(b) On 19 December 2013, Ms Broad had stated that Yum refused to incorporate the term requiring unanimous support of all Adco directors, as it would waive Yum’s right to use its casting vote and the power to set a maximum price, which resided with Yum under the International Franchise Agreement. Yum submitted at trial that what Mr Diab sought was something to which he was not entitled and which, if agreed, would fundamentally change the parties’ relationship.

42 At the Adco meeting on 18 February 2014, Yum presented the extent of decline in transaction growth for 2013 and 2014 and the directors discussed the “current value perception” of Pizza Hut. A resolution was sought to approve the updated marketing agreement, which contained an increase in Adco’s administrative contribution to Yum. The votes on the resolution were equally in favour and against the resolution. As a result, Yum exercised its casting vote, pursuant to clause 44 of Adco’s Constitution, and the updated marketing agreement was approved. On 30 April 2014, the Franchisees’ representatives on Adco resigned.

43 There was a dispute at trial as to why the Franchisees’ representatives had resigned from Adco. Mr Diab said that it was because they did not want Yum to convey to the Franchisees that Adco had approved the change in price. Yum suggested at trial that Mr Diab refused to attend the next meeting scheduled on 1 May 2014 so that he could obtain control over pricing, which was not a power conferred on him under the International Franchise Agreement. On 29 April 2014, Ms Syed confirmed that pricing would not be raised at the Adco meeting on 1 May 2014. Yum contended at trial that Mr Diab was not content with this assurance and that this was the reason for his resignation.

44 Her Honour considered that there was no need to determine the reason for Mr Diab’s resignation. The fact was that he resigned (Reasons, [128]).

45 After the resignation of the Franchisees’ representatives, Adco ceased to function or to approve marketing contributions and expenditure. Yum proceeded with the Value Strategy without Adco’s agreement.

The commercial context

46 We were told by counsel for the appellant (T30) (and there did not appear to be any dispute about this) that at the relevant times Domino’s had approximately 500 outlets in Australia, while Pizza Hut had approximately 300 outlets. At [408] of the Reasons, the primary judge found that Pizza Hut had lost, and was losing, market share. Counsel for the appellant accepted (T28) that there was no issue that Pizza Hut had been losing market share.

Communications with Yum US in November 2013

47 In November 2013, Yum sought funding from Yum US to conduct a trial of the Value Strategy in the Australian Capital Territory (the ACT Test). Yum presented the proposed ACT Test to various members of the Yum US leadership team, as seen by the PowerPoint presentation attached to an email sent by Mr Houston on 7 November 2013.

48 On 13 November 2013, Yum presented to the Yum US leadership team another PowerPoint presentation titled “Step Change Canberra”. DPL relied at trial on the following observation on the “Summary” slide:

If we can demonstrate success this will influence broader community and mitigate need for more costly support in the future when we do roll nationally.

The ACT Test (February to April 2014)

49 The ACT Test was commenced on 4 February 2014 and concluded on 28 April 2014. The ACT Franchisee, who owned all eight outlets in the ACT market, implemented the Value Strategy during this period with the assistance of Yum.

50 It was not in dispute at trial that Yum’s decision to test the Value Strategy in the ACT was appropriate. The primary judge found that test was appropriate for the following reasons:

(a) Yum believed that there was a “value” problem in Australia and it wished to see whether adopting the New Zealand $4.90 strategy would increase sales, transactions and Franchisee profitability.

(b) Conducting a trial of a strategy, such as the Value Strategy, was an appropriate action by a franchisor acting responsibly towards its franchisees, particularly where it had the co-operation and support of the participating franchisee and had agreed to indemnify him or her.

(c) The ACT was an appropriate place to conduct such a test because it was a distinct media market with its own signal, there was a single Franchisee who owned all eight outlets in the market, the Franchisee was one of the better performing Franchisees and the low average current level of per store average (PSA) sales meant that there was significant room for improvement.

51 On 8 March 2014, during week 5 of the ACT Test, Ms Broad sent an email to Mr Smith, Mr Houston and Mr Sinha providing her opinion as to the success of the ACT Test. Ms Broad stated the following opinion, based on three weeks’ profit and loss data:

My opinion at this stage is that the test was well worth doing and the marketing team should be congratulated – the sales growth and transaction growth we have achieved in this test have proven beyond doubt to everyone that velocity pricing is the path we need to head down. … Having said that, from a profitability stand point, I believe it’s marginal – this is one of our best Franchisee groups and I don’t believe they are making the same amount of money they were previously – it’s borderline at best at this stage.

…

From my perspective, looking at these numbers, our underlying business model doesn’t support velocity pricing … and I believe we should stop the test at the end of week 6 …

52 On 5 April 2014, during week 9 of the ACT Test, Mr Sinha sent an email to Mr Smith, copied to Mr Houston and Ms Syed, with the subject “Doms TV Ad $4.95”. The email stated:

Hi… Just heard Doms have a TV ad for $4.95 in [ACT]... waiting on confirmation… will let you know… Thanks

However, this email does not appear to have been followed up. The primary judge found that Domino’s did indeed respond to the new pizza prices in the ACT by television advertising (Reasons, [399]). However, it would appear that Ms Syed did not recognise this fact until some time in June 2014.

53 Domino’s responded to the ACT Test by making a $4.95 every day take-away offer. It appears that Domino’s responded in this way in week 9 of the ACT Test (see the slide set out at [67] below). Senior counsel for Yum accepted (T239) that Mr Houston knew that Domino’s had responded to that extent. However, as discussed below, Mr Houston did not know until 13 June 2014 that Domino’s had responded with television advertising.

54 On 16 April 2014, during week 11 of the ACT Test, Harpreet Singh sent an email to Jody Nicholas (of Yum), copied to various others at Yum, with the subject line “April Mega Month $4.95* Value Range Pizzas”. The email asked whether there was any update on Yum’s “plan of action” to “counter” Domino’s. On the same day, Ms Syed responded:

Hi Harpreet.

I hope my email finds you well. I completely understand your concerns with Domino’s starting to react to our offer (they have clearly figured out it is not a short LTO,) but we need to remember that we knew they would respond & frankly the only thing that surprised me was the amount of time they took to respond but it is becoming apparent the delay was due to the fact that they probably thought we were running this offer for a short period of time & chose to ignore it initially. From a brand perspective, we need to stay the course of the test as this is the model we are hoping to launch nationally if successful. What we don’t want to do is alter the test in such a way that it impacts the potential of a national rollout – like moving Hawaiian into the Classics range, putting a $7.95 Legends coupon into the market when testing a $8.50 price point, etc. We need to stay the course we are on & continue to reinforce the message we have established in the ACT.

I know this is probably unnerving & not what you want to hear, let’s chat through it further – I will give you a call over the next couple of days.

Regards,

Fatima.

The letters “LTO” would appear to stand for “Limited Time Offer” or “Limited Time Only”.

55 During the period of the ACT Test there was both an increase in sales and an increase in transactions, as can be seen in the slides set out at [60] and [67] below. It does not necessarily follow, however, that the ACT stores were more profitable during the period of the test.

56 Yum agreed to underwrite any losses suffered by the ACT Franchisee during the test period. As a result of the ACT Test, Yum paid the ACT Franchisee the sum of $143,000 to make good its losses. The ACT Franchisee continued to implement the Value Strategy after 28 April 2014 and Yum also paid the Franchisee $51,000 to make good the losses in this period after the completion of the test.

Communications with Yum US in April 2014

57 On 1 April 2014, Mr Houston sent an email to Kurt Kane, Chief Marketing and Food Innovation Officer at Yum US, and Ms Syed, attaching a PowerPoint presentation relating to the Value Strategy titled “Pizza Hut Australia – Partnering for Profitable Growth”. The covering email explained that the PowerPoint presentation was going to form the basis of Yum’s approach to Franchisees in a few weeks’ time. Mr Houston sought Mr Kane’s feedback. The slides in the PowerPoint presentation included the following slide (which has been redacted for confidentiality):

58 The PowerPoint presentation also included a slide to the effect that customer surveys indicated that Pizza Hut had a “value problem”. It was stated that: “Over the past 13 years, Pizza consumers in Australia have rated Pizza Hut 24% lower than Domino’s in regard to ‘Value for Money’.”

59 The primary judge did not consider it necessary to make a finding (nor did she consider the evidence sufficient to enable a finding to be made) as to the state of the Franchisees in the Australian market and whether there was a perceived ‘value problem’ and a decline in market share (Reasons, [409]). However, the primary judge did consider that it was clear from Mr Houston’s evidence that “he was of the view that something needed to be done to rectify or reverse what he perceived, based on information provided to him, to be a continuing decline in Pizza Hut’s position in the Australian market, in particular with regard to value for money” (Reasons, [409]).

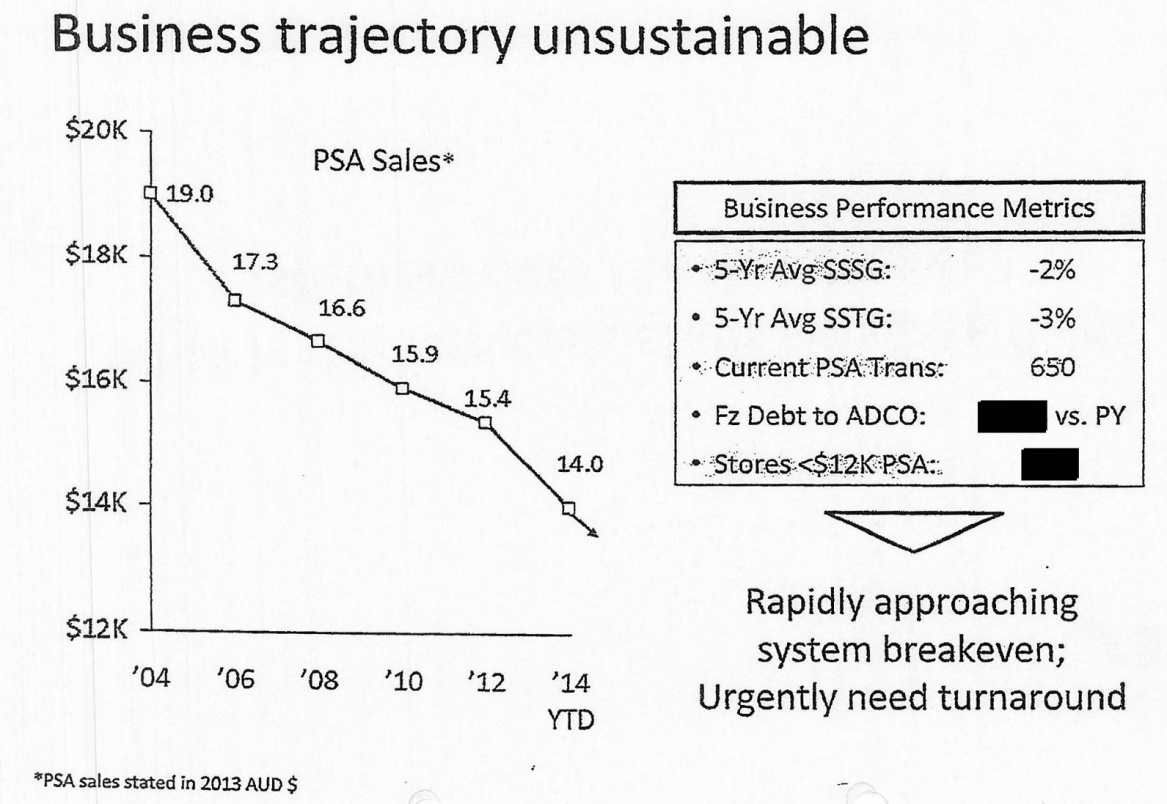

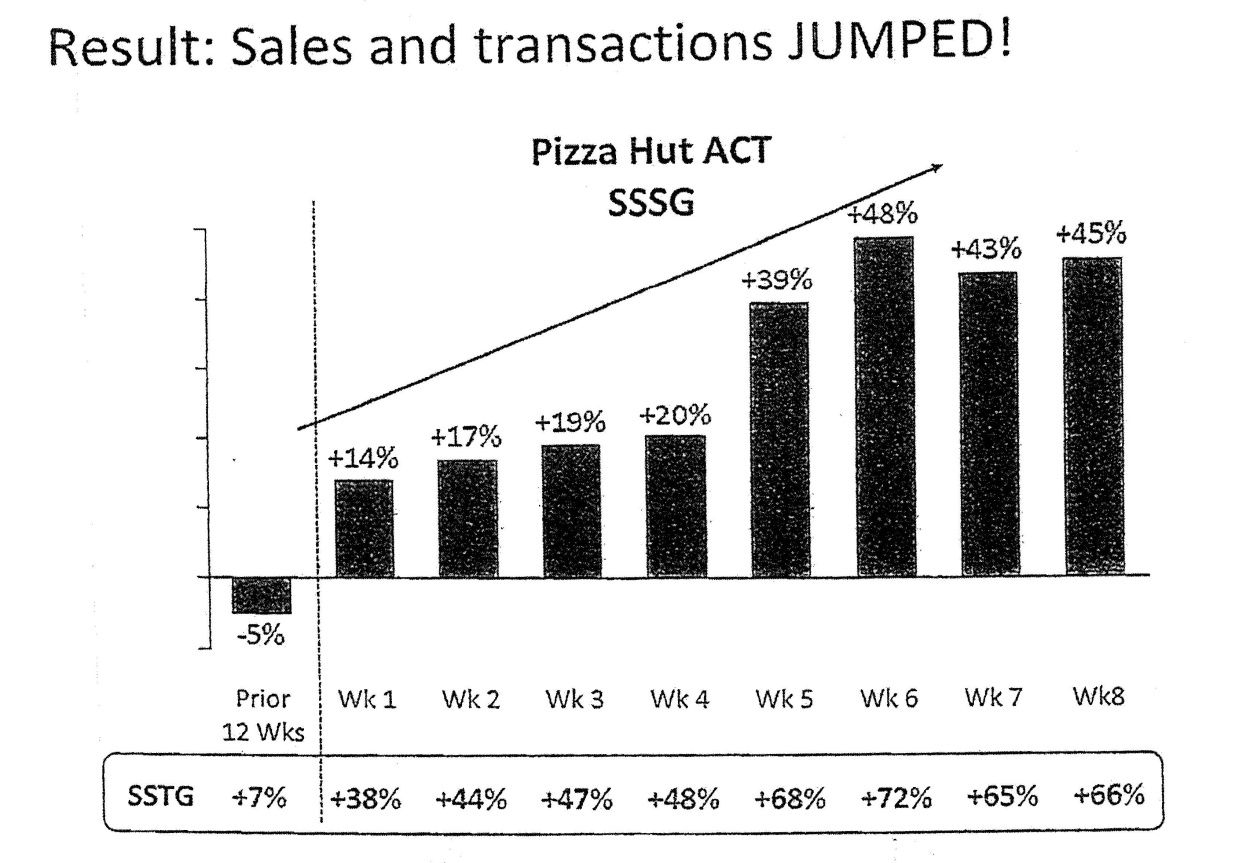

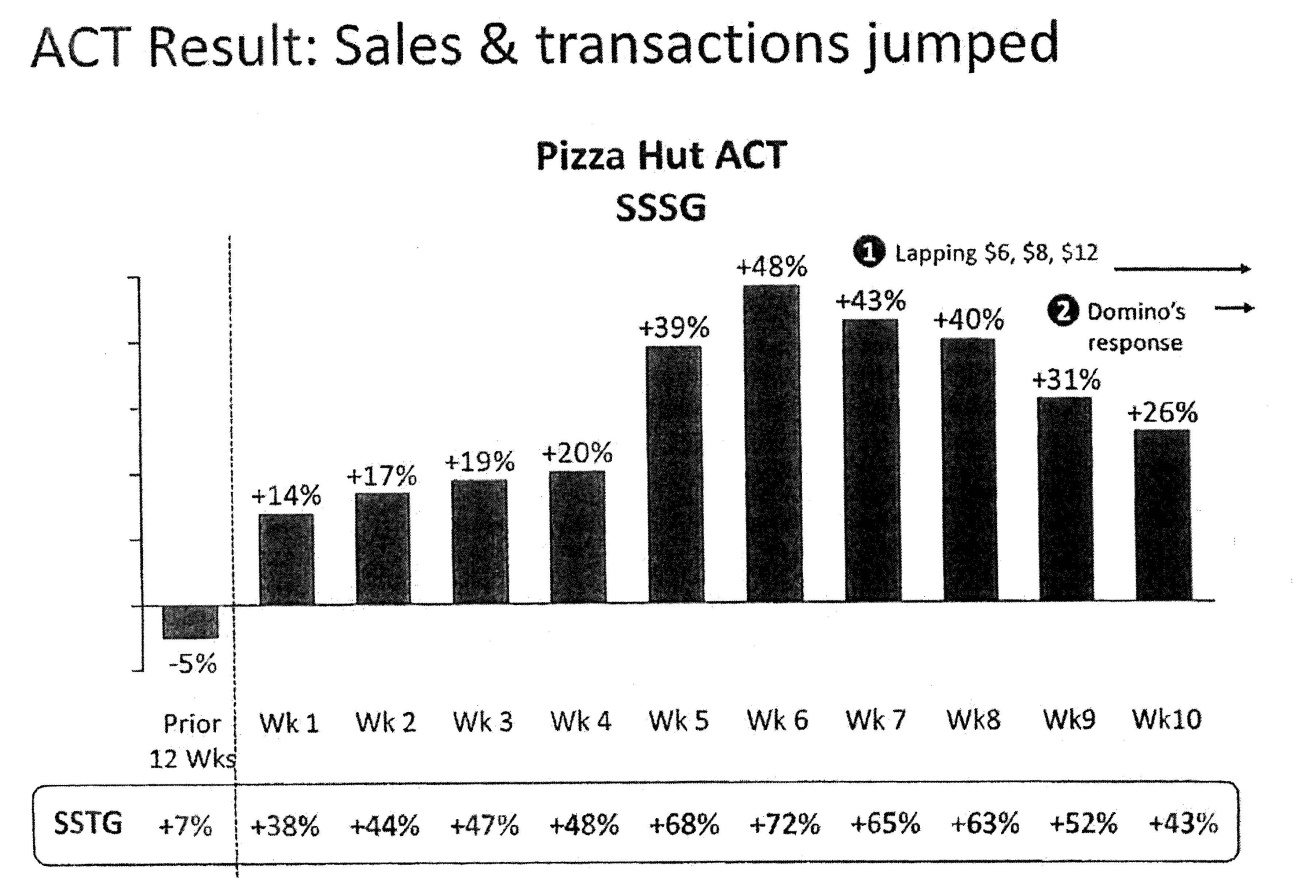

60 The PowerPoint presentation sent to Mr Kane and Ms Syed also contained a number of slides relating to the ACT Test, including the following:

In relation to the above slide, we note that “SSSG” refers to “same store sales growth” and “SSTG” refers to “same store transaction growth”. It appears that the figures are, in each case, a comparison with the prior year.

61 On 13 April 2014, Yum approached the Franchisee Policy Committee (FPC) in order to obtain plan relief for a national launch of the Value Strategy, which was now being considered. Mr Houston gave evidence describing the FPC as follows:

The [FPC] is a committee of senior Pizza Hut Global executives in Dallas who consider special requests from Yum business units around the world for the provision of incentives to franchisees outside the parameters of the IFA. The FPC’s role includes the review and approve any proposed incentives or deviation from the IFA.

(Errors in the original.)

62 On 14 April 2014, Eliane Setton of Yum US sent an email to Mr Houston, copied to Mr Ramirez and others, with the subject “FPC / Australia / Two-Tiered Value Pricing & Menu Simplification”. The email stated:

Hi Graeme,

The [FPC] is directionally aligned with setting up a two-tiered value pricing ($5 for “classic” pizzas and $8 for “legend” pizzas) and simplified menu (from 37 to 16 items) for the Pizza Hut system in Australia. Enrique [Ramirez] will contact you directly to finalize the mechanics/amounts for the 3 requests you sent through (AdCo contribution ($1MM), SCM write-off ($300K) and G&A for “spend-smarter” expert ($100K)).

In the meantime, please let me know if you would like to discuss further.

Eliane

63 On 22 April 2014, Mr Houston sent an email to Mr Ramirez attaching a PowerPoint presentation in similar form to the PowerPoint presentation entitled “Pizza Hut Australia – Partnering for Profitable Growth” referred to above. The PowerPoint presentation included the slides headed “Business trajectory unsustainable” and “Result: Sales and transactions JUMPED!” (with slightly different figures for week 8).

64 On 23 April 2014, Mr Ramirez responded to Ms Setton’s email. His email stated:

Hi Eliane –

I had a chance to connect with Graeme and we are now fully aligned on their two-tiered value pricing plan including the 3 requests that you mention below (none of them is subject to Plan relief, FYI). The plan is approved from my perspective and Scott has signed off as well.

Thanks.

Enrique

65 On the same day, Mr Houston sent an email in response to Mr Ramirez’s email. Mr Houston’s email stated as follows:

Thanks Enrique, appreciate the support. We are very excited about the ability to change the game once and for all in Australia and this goes a long way to ensuring success. Given the test result of 30% growth and the probability that we can replicate this nationally we are confident that it will not impact plan for balance of yr.

Game on!!

Early May 2014

66 On 5 May 2014, Russel Creedy, the Chief Executive of RBNZ, the sole New Zealand franchisee, sent Mr Houston an email that stated that the “secret” to the strategy that had been adopted in New Zealand was to maintain the number of labour hours despite the higher volumes, and that in New Zealand they had been able to prevent an increase in labour costs to meet the additional transactions.

Meetings with Franchisees on 14 and 15 May 2014

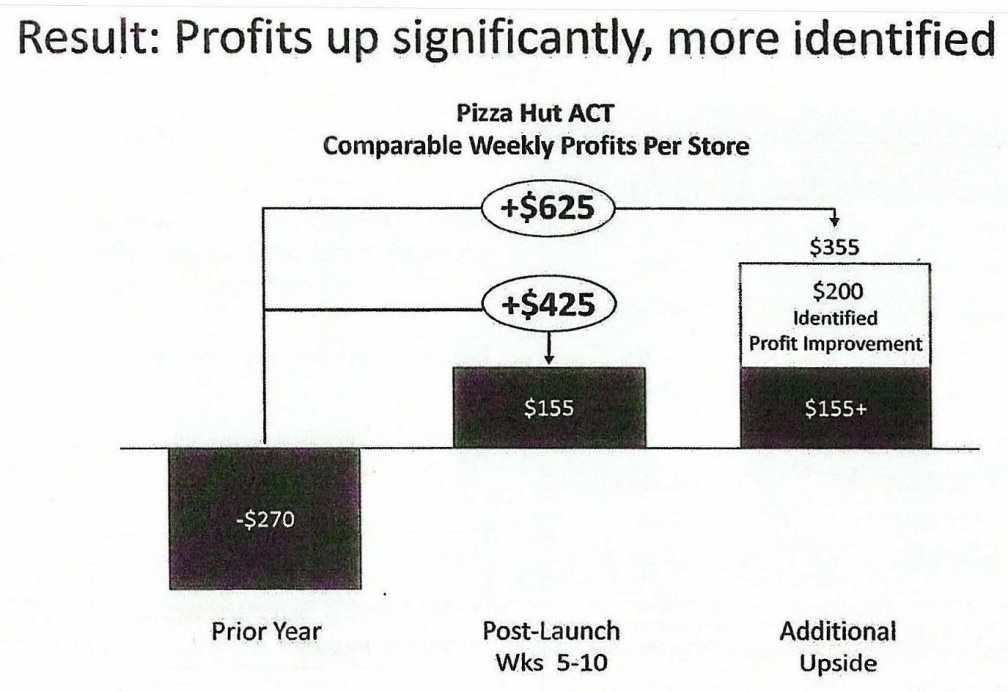

67 On 14 and 15 May 2014, meetings took place between Yum and Franchisees. Yum gave a presentation entitled “Franchisee Update May 2014” (the May 2014 Franchisee Update). This included a number of slides that were similar to the PowerPoint presentations sent to Yum US referred to above. One of the slides was headed “Business trajectory unsustainable” and was similar to the slide set out at [57] above. The presentation also included a number of slides relating to the ACT Test, including the following:

68 Another slide in the May 2014 Franchisee Update contained the following financial analysis of the ACT Test:

69 As recorded in the Reasons at [52], DPL contended at trial that Yum represented to the Franchisees, in the May 2014 Franchisee Update, that there had been a $425 per week per store improvement in comparable profit in weeks 5-10 of the ACT Test. Yum submitted at trial that weeks 1 to 4 were not included in the figures presented to Franchisees on 14 May 2014 because the results in that period were not in a “steady state” and that this issue was not challenged by DPL. Yum also submitted that weeks 11 and 12 were not included because of the impact of the Easter and ANZAC Day holidays. Yum submitted that, at the time of the presentation, Ms Broad did not have profit and loss statements from the ACT Franchisee. DPL contended at trial that the calculation of the $425 improvement was “simply a product of financial engineering by Ms Broad that does not withstand reasonable scrutiny”. The primary judge found that DPL had not established that Ms Broad engaged in deliberate “engineering” of the results, but that it had established that the presentation did not include relevant data, which may have affected the conclusions that could be drawn (Reasons, [52]).

70 DPL submitted at trial that the true position, which was neither revealed to the Franchisees nor to Jagot J on the hearing of the interlocutory injunction application on 24 June 2014, was that the ACT Franchisee had incurred a loss during the ACT Test of approximately $140,000, for which it was compensated by Yum pursuant to the indemnity or “backstop” arrangement. Further, Yum had also agreed to pay an additional $51,000 to the ACT Franchisee for its post-test losses on the basis that it maintained the Value Strategy prices following the conclusion of the test.

71 At trial, DPL submitted, relying on the May 2014 Franchisee Update, that there were two elements that comprised the calculation of the alleged $425 improvement in per week per store profit as a result of the ACT Test:

(a) an alleged post-launch profit for weeks 5-10 of $155 per week per store; and

(b) a prior year loss of $270 per week per store.

72 The primary judge noted that Ms Broad conceded that the $155 per week per store figure was taken from the adjusted profit and loss figures for weeks 5-9 (in Exhibit AO), not weeks 5-10 as stated in the above presentation document. In cross-examination, Ms Broad stated that the calculation of $155 was only until week 9 and then Yum “double-checked to see if week 10 made a difference to that number”. DPL contended at trial that Ms Broad invented this answer in the witness box to “attempt to cover up this relatively trivial slip”.

73 The primary judge found that the figure of $155 per week per store was calculated on the assumption of a contribution of 1.5% of sales for local store marketing (LSM) costs. DPL argued at trial that Ms Broad arrived at this figure by “stripping out” LSM costs in excess of 1.5% and that this approach was not according to normal accounting practices of “matching” expenses and revenues. DPL analysed the full 12 week profit and loss for the ACT Franchisee, who incurred a 1.8% charge for “Local Store Marketing – Leaflet” costs and a 4% charge for “Additional LSM”. On this basis, the ACT Franchisee incurred costs equating to 5.8% of sales during the ACT Test that were as a result of LSM.

74 The primary judge noted that Ms Broad had explained that the 4% Additional LSM was not actually spent by the ACT Franchisee on LSM but was paid by it to Yum as a contribution to the overall marketing budget for the ACT Test. Nonetheless, DPL contended at trial that Yum failed to account for all marketing expenses when determining net profit and arbitrarily cut off the LSM expenses at 1.5% of sales rather than accounting for the 5.8% in total marketing expenses. It followed, DPL said, that if Yum had taken the full cost into account, the amount of extra cost would have been at least three times the amount calculated for LSM expenses in the May 2014 Franchise Update, and an overall loss would have been calculated. The primary judge noted that Ms Broad did not object to this proposition if DPL’s calculation was correct and if it was appropriate to take the Additional LSM into account.

75 Yum acknowledged at trial that the ACT Franchisee did provide 4% Additional LSM. However, it contested the argument that the 4% should have been taken into account when analysing whether the ACT Test was profitable. Ms Broad said that she was “trying to get an understanding of what would happen to the [profit and loss] of a store if we launched the pricing strategy nationally” and that the 4% Additional LSM was required to replicate the marketing budget that would be used nationally. Yum submitted at trial that the “matching principle” was not appropriate in the circumstances because Ms Broad was analysing the impact on profitability that the Value Strategy would have upon a national rollout and the 4% Additional LSM would not be replicated on a national level. That is, the expense would not be incurred by the Franchisees on a national level, as the Franchisees’ contribution to the overall marketing budget would be what they currently paid.

Emails regarding New Zealand strategy (20 and 22 May 2014)

76 On 20 and 22 May 2014, there was an exchange of correspondence between Mr Houston and Mr Creedy. On 20 May 2014, Mr Creedy sent an email to Mr Houston with the subject line “NZ $490 Strategy”. It would seem that the proposed Value Strategy for Pizza Hut in Australia (at least in general terms) had come to Mr Creedy’s attention. The email relevantly stated:

I have been asked about the New Zealand $4.90 strategy and the selling of stores for $1million as a result of the big turn around. Although we have not been privy to the briefings held with Australian Franchisees and the decisions YUM! Pizza Hut are making regarding the future strategies, I want to make sure Restaurant Brands strategy and results are not being relied on to justify a similar strategy for the Australian market.

We previously discussed the significant differences between the two markets, such as:

1) RBL was losing a substantial amount of money on Pizza Hut and therefore the down side and risk was evaluated as acceptable at the time. My understanding is that the Australian Franchisees are not in a similar position. Please be very cautious as once started the strategy can not be turned off.

2) NZ had down sized the pizza pans to cut the product costs by over 25%, making the strategy possible.

3) NZ labour rates are substantially lower ($14.25/hr vs about $20/hr in Australia). Low labour costs are imperative to succeed with a similar strategy.

4) Despite the initial transaction and sales lift over the first few periods, it required transactions to almost double and labour hours frozen at pre-discount levels before the business produced positive EBIT. I understand the ACT test has only delivered between 15% - 30% more sales and I assume this is insufficient to justify the level of discount.

5) RBL has a cost advantage over Dominos in many ways including media buying, cost of ingredients, freight, fixed cost and we have the same number of stores in the market.

6) Dominos were caught with their pants down and did not respond for several periods as they assumed RBL could not maintain the strategy, but as per point (1) above we had no alternative. I suspect Dominos will not sit back in Australia but will activate an aggressive counter strategy and with almost double the number of stores Dominos should have the advantage.

Graeme, there are many more market differences we can highlight and I request you only rely on market test results in Australia to provide data for future price strategy decisions.

77 Mr Houston responded by email on 22 May 2014. Mr Houston’s email stated in part:

Thanks for the email Russel, I would like to clarify a couple of points that you have raised

I can assure you that we have not solely relied on the NZ results when determining our approach in Australia. The 2.5 years of sustained sales and profit momentum as a result of your $4.90 strategy is clearly something we wanted to learn from. Building on the learning we tested and validated a similar model in a test market in Australia. We only included the slides that you had approved in the presentation deck but we thought it was important to share because we wanted to show the Australian franchisees that it it was not just a short term spike but sustained over 2 years. We also wanted to show that NZ and the Au test market performed very consistently.

I actually would argue that the markets are more similar than different, the test results were very consistent with the Au test performing a little more strongly in the first 12 weeks. Dominos also run the same marketing calendar in NZ. That said we validated the concept in a 12 week test in australia.

Consistent with NZ 2 yrs ago many of the Australian franchisees are facing sales levels that require a step change, not all franchisees obviously but a growing and significant proportion are facing a similar question that you faced.

NZ resized the pizzas around the same time as Australia, around 2009 which was 2 yrs before the decision to launch the $4.90 strategy.

The relative labour rates are a little more complex to compare. Aust has youth rates which are lower than the nZ labour rate, whilst the adult rate is higher, the final outcome depends on your ability to optimize the labour mix. I agree with your assessment on the importance of locking the labour hours, we got the same learning in the test market despite the sales lift actually being more than the NZ results. Success depends on controlling these costs

It is impossible to predict any competitive response but interestingly the response in the test market was similar to what you saw in NZ.

I absolutely agree with your comments about getting the cost lines right and that is something that will be different between the two countries and why testing in australia was so important.

(Errors in original.)

78 While Domino’s had a greater number of stores compared with Pizza Hut in Australia at the relevant time, that was not the case in New Zealand (see the Reasons at [380] and Mr Diab’s affidavit of 19 June 2015 at [63](a)).

The Yum Model

79 In late May 2014, Yum began to prepare a model to assist it in deciding whether to implement the Value Strategy (the Yum Model). Mr Houston gave evidence (which, we infer, the primary judge accepted) that Ms Broad was responsible for the Yum Model and that Mr Smith’s role was to “validate and refine it”.

80 Through an iterative process of entering various inputs, Yum concluded, based on the Yum Model, that if the proposed new lower prices were adopted, transactions would need to increase by approximately 34.5% for the national average store to ‘break even’. (The word “transaction” is used to refer to a bundle of sales to a particular customer on a particular occasion. For example, a single transaction may comprise the purchase of two pizzas and a soft drink.) This would require an increase of 218 transactions per store per week (from 635 transactions to 853 transactions per week). It is important to note that the object of the model was to determine the transaction uplift needed for the average store to ‘break even’, that is, to retain the same EBITDA after the introduction of the Value Strategy (Reasons, [395]). It was not designed to predict the transaction growth likely to result from the adoption of the Value Strategy (Reasons, [77]).

81 The Yum Model drew a distinction between two sales channels, take-away and delivery, as it recognised that customers have different behavioural patterns in these two channels. The parties were agreed at trial that delivery customers are less price-sensitive than take-away customers. For example, delivery customers were considered more likely to pay a higher price for drinks than were take-away customers.

82 Six iterations of the Yum Model were in evidence at trial, and DPL tendered a summary comparison of those models. The Yum Model was brought into existence in late May 2014 and refined in early June 2014. Yum submitted at trial that the Yum Model first emerged on 28 May 2014 and was worked on from that date to 3 June 2014. DPL contended at trial that the inputs for the Yum Model were not finally settled until 19 to 23 June 2014, when a copy of the Yum Model was produced for the purpose of exhibiting it to Mr Smith’s affidavit for the interlocutory injunction hearing on 24 June 2014. DPL argued that this was clear from the change in the labour rate from the $15 per hour rate that was used in the Yum Model up to 19 June 2014 to the $14 per hour rate appearing in the Yum Model exhibited to Mr Smith’s affidavit sworn on 23 June 2014.

83 DPL noted at trial that Mr Houston had conceded in cross-examination that the Yum Model, in the form presented at the interlocutory injunction hearing on 24 June 2014, had been changed after 4 June 2014 (when the decision was made by Mr Houston to adopt the Value Strategy: see [95] below). This version of the Yum Model indicated that 13 additional labour hours would be needed to accommodate the transaction uplift caused by the introduction of the Value Strategy. In support of its contention regarding changes to the Yum Model, DPL referred to an email from Travis Purcell to the Yum leadership team on 6 June 2014 attaching a version of the Yum Model containing an input of nine additional labour hours. DPL also referred to a subsequent email from Mr Purcell on 19 June 2014 that attached a version of the Yum Model with 10 additional labour hours. DPL put to Mr Sinha that this attachment was the latest version of the Yum Model at that time and that the assumptions in it were still being revised. Mr Sinha disagreed with this contention, as he said that the assumptions had already been made on 4 June 2014.

84 Yum submitted at trial that the Yum Model was discussed on 3 and 4 June 2014 at a meeting of Yum’s leadership team (discussed below), where it was displayed on a screen. Yum pointed out that Mr Sinha gave evidence that the 13 additional labour hours had been included in the Yum Model during the course of the meetings on 3 and 4 June 2014 and that he had no further consultation with any person after that time concerning labour hours. Yum argued at trial that there was no reason not to accept this evidence, as the discussion about labour hours at the 4 June 2014 meeting occurred when the Yum Model was on a screen and the document was not saved at that date. Even though the 6 June 2014 version contained nine additional labour hours and the 19 June 2014 version contained 10 additional labour hours, Yum argued at trial that this did not contradict Mr Sinha’s evidence, because his evidence was that the 13 hours had not been saved as an input at the time of the 4 June 2014 meeting.

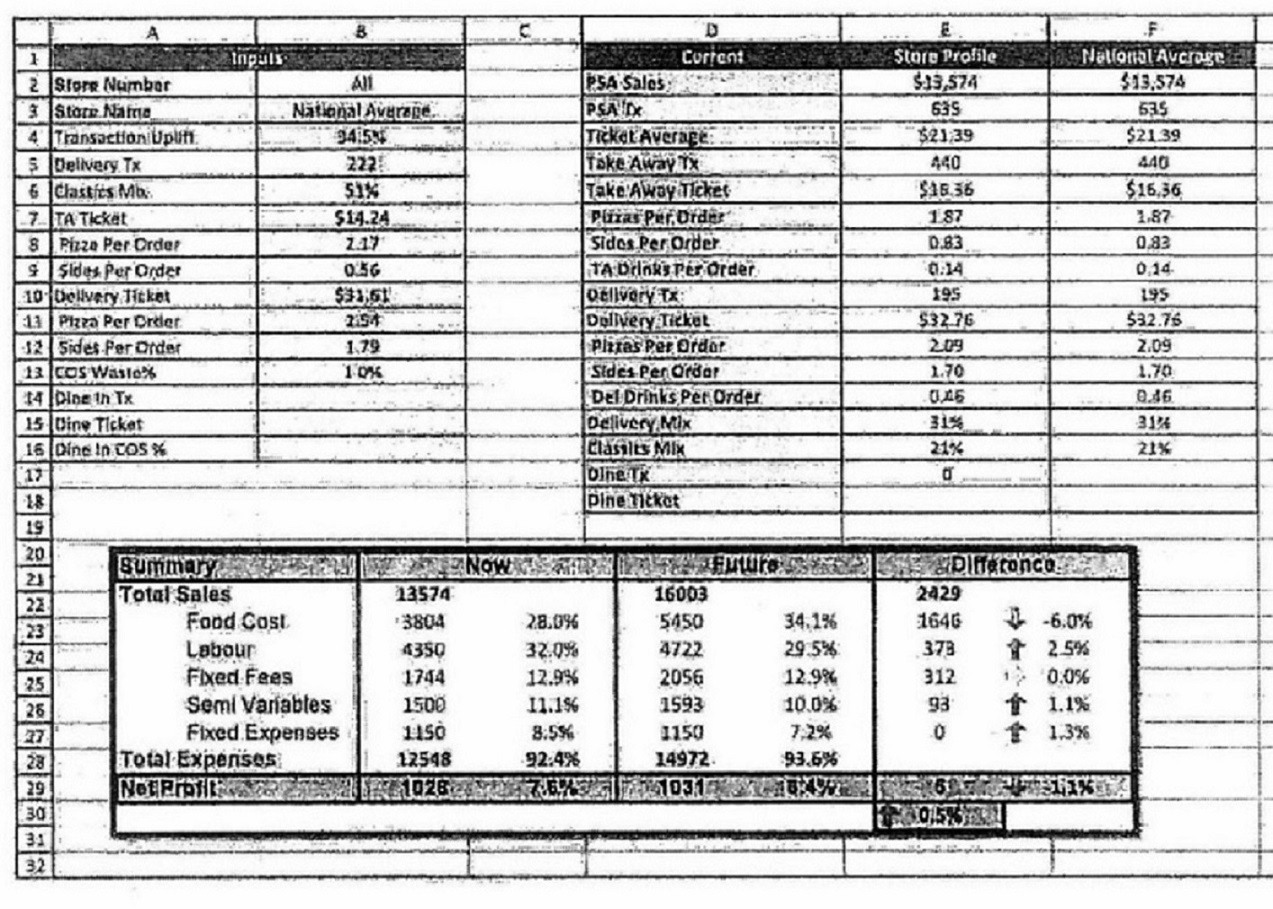

85 During the appeal hearing, we were taken, in particular, to an extract from the version of the Yum Model exhibited to Mr Smith’s affidavit for the interlocutory injunction (AB Pt C, tab 8). This version contains 34.5% as the transaction uplift percentage necessary for the national average store to ‘break even’. It also includes, as an assumption, that an additional 13 hours of variable labour would be required to process the additional 218 transactions that would occur if there was a 34.5% increase in transactions. There is no finding in the Reasons as to precisely when this version of the Yum Model was produced. In any event, it is convenient to refer to this version of the Yum Model for the purposes of considering certain issues raised by the appeal. We reproduce below a copy of this version of the Yum Model. To assist readability, we have split the first page of the document into two halves. The left-hand side of the first page was as follows:

We make the following observations about the above extract from the Yum Model. First, the figure for the transaction uplift (namely 34.5%) appears in row 4, column B. Secondly, the figures appearing in row 6, column B (Classics mix) and row 7, column B (TA Ticket) are derived from column L of the spreadsheet (reproduced below). Thirdly, the figures for “Store Profile” in column E are weekly figures. Fourthly, in the lower part of the above extract there is a table containing the heading “Now”. That heading refers to the position of an average store before implementation of the proposed Value Strategy. Fifthly, the reference to “Net Profit” in that table would appear to be a reference to EBITDA.

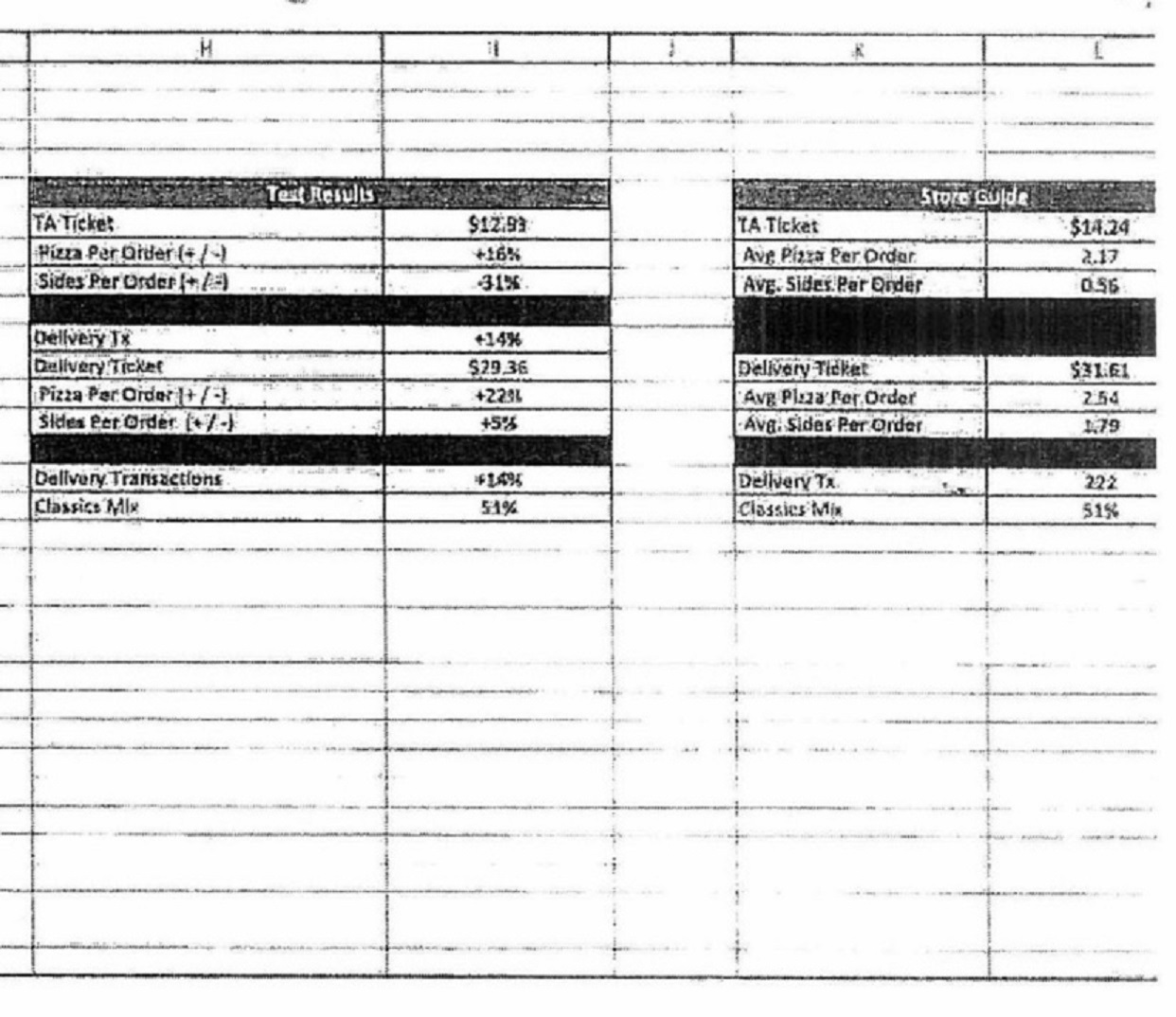

86 The right-hand side of the first page of the Yum Model was as follows:

The reference to “Test Results” in the heading in columns H and I is to the ACT Test results.

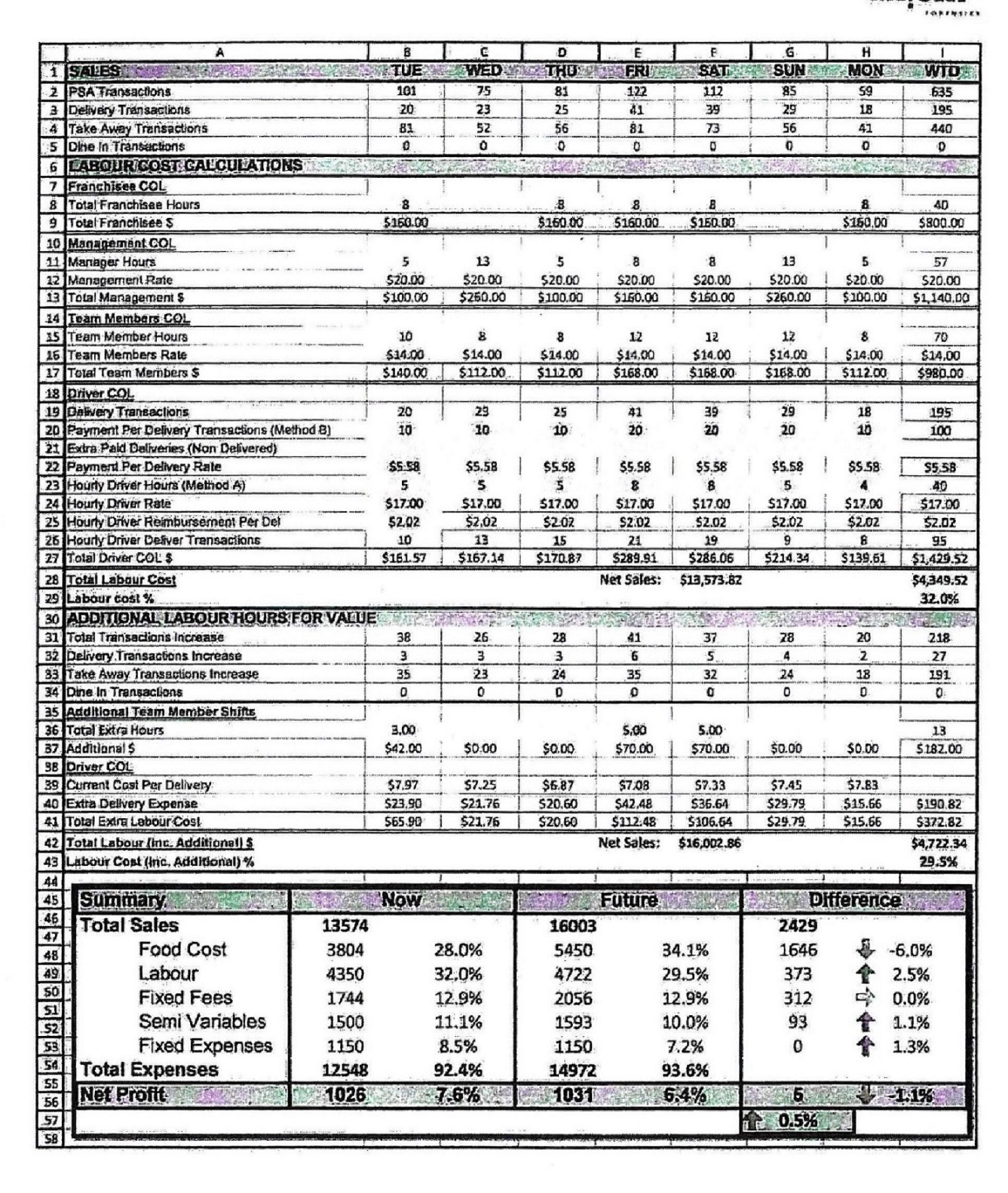

87 The second page of the Yum Model was as follows:

We make the following observations about the above extract from the Yum Model. First, the figure of 635 appearing in row 2, column I represents (on an average basis) the existing number of transactions per store per week. Secondly, the increase in transactions referred to earlier (namely, an increase of 218 transactions per week) appears in row 31, column I. Thirdly, the figure of 13 hours per week for extra labour hours appears in row 36, column I.

88 At trial, DPL did not criticise all aspects of the Yum Model. DPL stated that it was “a very useful EBITDA model for Australian Pizza Hut outlets, and was capable of being [sic] to evaluate the impact of the VS upon those outlets through the consideration of the ‘national average’ outlet”. To this extent, DPL said that it accepted Ms Broad’s evidence that “[m]odelling a store on a national average basis is a standard financial average technique used in the business”.

89 DPL accepted at trial all of Yum’s inputs into the Yum Model other than the input for “variable labour”. As has been noted, Yum made an assumption in the version of the Yum Model extracted above that an additional 13 hours of variable labour would be required to process the additional 218 transactions that would occur if there was a 34.5% increase in transactions.

90 Mr Sinha placed the additional 13 hours of variable labour assumption into the Yum Model. At trial, Yum summarised how Mr Sinha derived his assumption as follows:

(a) Mr Sinha first calculated the minimum number of weekly labour hours that would be required to staff a Pizza Hut outlet, given Yum’s rules about minimum staffing levels. This was 97 hours of management, 70 hours of team member time and 40 hours of delivery drivers who also assist in the store. That is, the total was 207 hours. Mr Sinha formed the view that these hours were more than sufficient to service the pre-Value Strategy transaction level of 635 transactions per week. Mr Sinha gave evidence that 70 team member hours when divided by 635 transactions produces a “minutes per docket” (MPD) of 6.6. (The word ‘docket’ is used interchangeably with ‘transaction’.) Mr Sinha observed that this figure was less efficient than the New Zealand benchmark of 5.6 and the results achieved during the ACT Test. Accordingly, Mr Sinha concluded that an MPD of 6.6 was reasonable and, therefore, that his estimate of 70 team member hours was also reasonable.

(b) Mr Sinha then allocated the 218 additional transactions on a day-by-day basis during the week, maintaining the same relativities on a day-by-day basis as before the Value Strategy. This resulted in a different number of additional transactions for each day, ranging from 20 additional transactions on a Monday to 41 additional transactions on a Friday.

(c) On the basis of Mr Sinha’s own experience of utilising labour in Pizza Hut outlets, he formed the view that the existing minimum labour hours would not be fully utilised before the introduction of the Value Strategy. In other words, in Mr Sinha’s opinion, the minimum 207 labour hours used before the Value Strategy was capable of producing more than 635 transactions per week.