FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Olympic Committee, Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited

[2017] FCAFC 165

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, INC Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[6] | |

[6] | |

[17] | |

[18] | |

[27] | |

[34] | |

[40] | |

[46] | |

[55] | |

[57] | |

[61] | |

[61] | |

[72] | |

[79] | |

[81] | |

[81] | |

[90] | |

[93] | |

[111] | |

[158] | |

THE COURT:

1 The 2016 Summer Olympic Games were held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in August 2016. In July 2016 the respondent (Telstra) commenced an extensive marketing campaign, promoting the availability of live events streamed from the Rio Olympics by Seven Network (Operations) Ltd (Seven). The Australian Olympic Committee Inc (AOC), which is the National Olympic Committee for Australia, took exception, contending that the campaign amounted to ambush marketing of a type that is prohibited by the terms of the Olympic Insignia Protection Act 1987 (Cth) (OIP Act) and amounted to misleading and deceptive conduct in breach of provisions of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2, Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL). A particular focus of the AOC’s complaint was that certain promotional materials made use of expressions protected for the exclusive use by the AOC including “Olympic” and “Olympic Games”. It sought orders including injunctions to restrain the marketing, and declarations of breach and damages.

2 One week after the proceedings were filed, the primary judge heard the case on an urgent final basis and one week later he delivered judgment, dismissing the application; Australian Olympic Committee, Inc. v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2016] FCA 857. In this appeal, the AOC seeks to overturn that decision.

3 The subject matter of the hearing before the primary judge consisted of an agreed group of 34 separate types of advertisements, promotional or marketing communications (Telstra advertisements) that fell within the AOC’s application for relief. His Honour conveniently distilled those into seven categories: first, Telstra’s “Rio” television advertisements concerning access to Olympic coverage on mobile devices using the Telstra network; second, advertisements concerning a Samsung mobile phone promotion; third, videos available on third-party websites concerning access to Olympic coverage on mobile devices via the Telstra network; fourth, Telstra catalogues that included promotions relating to access to Olympic coverage; fifth, Telstra’s authentication “landing page”; sixth, retail or point-of-sale material; and seventh, Telstra’s Keeping in Touch or “KIT” email, and other digital materials.

4 In summary, the Statement of Claim alleges that Telstra used one or more protected Olympic expressions in the Telstra advertisements in breach of s 36 of the OIP Act (OIP Act claim). The Statement of Claim also alleges that each of the Telstra advertisements conveyed a false representation, or had a tendency to cause people erroneously to assume, that Telstra or its products or services have some form of endorsement, sponsorship, affiliation or sponsorship like arrangement with the Olympic Games, the Olympic movement, the AOC or another Olympic body such as the International Olympic Committee (ACL claim).

5 On appeal, the AOC contends that the primary judge erred in giving insufficient weight to some considerations and in giving too much weight to other considerations relevant to the application of the OIP Act and the ACL. It submits that this Court should conduct a fresh evaluation of the materials and resolve the matter in its favour. It also contends that particular aspects of the primary judge’s reasons reflect error that, once corrected, would yield a different outcome. We have considered the materials afresh and conclude that the primary judge’s decision does not reflect the errors for which the AOC contends. For the reasons more fully explained below, we dismiss the appeal and order that the appellant pay the respondent’s costs.

6 The modern Summer Olympic Games have (with three exceptions) been held under the organisation and control of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), every four years since 1896.

7 The Olympic Charter relevantly defines the respective rights and obligations of the IOC and the AOC. Subject to Australian law, the rules of the Olympic Charter deal with the rights over the Olympic Games. They provide that the IOC is the owner of all rights in and to the “Olympic properties”, which include the famous five-ringed Olympic symbol, the Olympic flag, the Olympic motto (“faster, higher, stronger”), the Olympic anthem, various Olympic emblems, the Olympic flame and torches and the Olympic designations, which include any visual or audio representation of any association, connection or other link with the Olympic Games, the Olympic movement or any constituent thereof.

8 The IOC and, in Australia, the AOC have for many years entered into sponsorship and affiliation arrangements and agreements with national and multinational companies. There are many different levels and categories of sponsorships. Their common feature is that, for varying levels of consideration, companies that enter into such sponsorship arrangements are generally able to promote themselves by association with the Olympic Games or teams participating in the games. Sponsorship arrangements entered into by the AOC almost invariably include the grant of a license to use Olympic designations or Olympic properties.

9 For many years Telstra was an Australian Olympic team sponsor in the telecommunications category, and as part of that arrangement the AOC granted Telstra the exclusive rights in that category to promote itself by association with the Australian Olympic team and the AOC. Telstra was licensed to use, in that context, the Olympic properties, including expressions such as “Olympic”, “Olympics” and “Olympic Games”.

10 The sponsorship arrangements between the AOC and Telstra came to an end in 2012. Telstra is no longer licensed to use these expressions and no longer has any sponsorship arrangement with the AOC. The AOC’s current sponsorship and licensing arrangements in the telecommunications category are with Telstra’s main competitor, Optus Mobile Pty Ltd.

11 In June 2014, the IOC and Seven entered into an agreement in relation to broadcast rights which included the rights in relation to the 2016 Rio Olympic Games (IOC agreement). Seven was granted the exclusive rights to broadcast and exhibit those games in Australia. Those rights are not limited to broadcast by television, but included broadcast by means of digital streaming for devices including mobile phones and tablet devices.

12 The terms of the IOC agreement provide that Seven is permitted to exploit its broadcast rights by, amongst other things, selling broadcast sponsorships and advertising in connection with the broadcast and exhibition of the Games. Seven’s broadcast sponsors are not authorised to use any of the Olympic properties, although it is contemplated that broadcast sponsors be authorised to use phrases such as “[Seven’s] Olympic Games telecast is made possible/brought to you by [Seven’s] telecast sponsors/partners…” or any equivalent phrase approved in writing by the IOC.

13 In June 2016, Seven entered into an agreement with Telstra in relation to Seven’s broadcast of the Rio Olympic Games (Seven agreement) pursuant to which Seven agreed to build maintain, fund, post and operate a mobile phone and tablet application called “the Olympics on 7 app” and a Rio Olympic Games website. Each would house free and premium content for the Rio Olympic Games, the free content to be accessible by the general public regardless of their internet services provider, the premium content being accessible to the general public, but only upon the payment of a one-off access fee. Telstra mobile customers could access the premium content free of charge once they obtained authentication via the Telstra authored authentication page on its website. The Seven agreement provides that Telstra will fund, build, host and maintain its authentication landing page and that such page would be branded with Telstra trademarks.

14 The Seven agreement also provides that Telstra is permitted to promote and advertise the Olympics on 7 app, subject to prior approval by Seven. Telstra is entitled under the agreement to use certain “designations” agreed by the parties and approved by the IOC, in its marketing, advertising and promotional material. The designations include the phrases “Seven’s Olympic Games broadcast is supported by Seven’s official technology partner, Telstra” and “Telstra, Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games coverage”.

15 The Seven agreement provides that if Seven reasonably considers that it is required to seek IOC approval as a result of Telstra using Olympic indicia or if the overall impression is that Telstra is an official sponsor or affiliated with the games or the AOC or IOC, Seven is required to provide Telstra with an opportunity to alter the promotion or marketing to avoid the need for IOC approval or promptly seek consent from the IOC.

16 Seven did in fact seek and obtain the IOC’s approval or consent in relation to the form of Telstra’s proposed authentication landing page for the Olympics on 7 app, but not in relation to the form or content of any of the other Telstra advertisements.

2.2 The Telstra advertisements

17 The primary judge provided a useful summary of the advertisements in issue. That summary was agreed by the parties to be accurate, save that the AOC contends, as we note in section 6 below, that it fails effectively to interpret the evocative imagery created by the advertisements, particularly the television advertisements and the website videos. Sections 2.2.1 to 2.2.7 below, are taken from the primary judge’s summary.

2.2.1 Telstra’s “Rio” television advertisements

18 There were three versions of Telstra’s television advertisement concerning the use of the Telstra network to watch the Rio Olympic Games on mobile devices. Each of them is 30 seconds long and involves the same images and the same musical soundtrack. The musical soundtrack is a version of Peter Allen’s well-known song “I Go to Rio”. The visual images include: a father and son driving in the country, the son watching what appears to be an Olympic gymnastics event on a mobile phone or tablet and then leaping a gate like a gymnast; rowers in a rowing shed watching an event on a mobile phone; children doing taekwondo and watching an event on a tablet device; girls watching soccer on a tablet before playing a game of soccer; and two elderly swimmers at an ocean-side lap pool watching swimming on a mobile phone before swimming laps. In some instances the “7” logo appears on the mobile or tablet devices that depict the advertisements.

19 There are some differences between the three versions of the advertisements. Those differences mainly concern the content of the voiceover and the written messages or statements in the advertisement.

20 The first of the advertisements (Rio TVC) has the following voiceover: “[t]his August, for the first time ever, watch every event in Rio live with the Olympics on 7 app and Telstra, on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. At one stage the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network” appear on the screen. Towards the end of the advertisement the Telstra logo and the words “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage” and “Olympics on 7” appear on the screen. The “7” is in the form of Seven’s fairly well-known logo.

21 Evidence led by Telstra showed that Seven sought the IOC’s consent to use the statement “Telstra … Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”. The IOC’s consent or approval was communicated to Seven in late May or early June 2016.

22 The facts agreed between Telstra and the AOC indicate that the Rio TVC was broadcast between 3 and 7 July 2016 and once in error on 8 July 2016.

23 In the second advertisement (revised Rio TVC) the voiceover is different. The voiceover is: “[t]his August all Telstra mobile customers will have free premium access to every event live on Seven’s Olympics on 7 app. Enjoy the action on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. The other important difference is that for the first approximately 20 seconds of the advertisement the words “Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams” (disclaimer) appear in fairly prominent white script at the bottom of the screen. After about 20 seconds the prominent words “Telstra is Seven’s broadcast partner” appear on the screen and the disclaimer disappears. Those words are then replaced by the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network”. At the foot of the screen the words “Based on national average mobile speeds” and “Data charges will apply” appear in script much the same size as the disclaimer.

24 The revised Rio TVC was broadcast from 6.00 pm on 11 July to the evening of 12 July 2016.

25 The third version of the advertisement (further revised Rio TVC) is very similar to the second. The only noticeable difference is that the disclaimer appears for approximately 27 seconds, almost the entire duration of the advertisement. It is only at the very end of the advertisement, when the words “Australia’s fastest mobile network” appear, that the disclaimer is replaced by the words “Based on national average mobile speeds. Data charges will apply”.

26 The further revised Rio TVC was broadcast from the evening of 12 July to 17 July 2016 and, it may be inferred from the program schedule in evidence, on 31 July 2016.

2.2.2 The Telstra Samsung promotion advertisements

27 There are also three versions of Telstra’s television advertisement promoting a data plan referable to a particular Samsung mobile phone.

28 The first version (Telstra Samsung TVC) again has the “I Go to Rio” soundtrack. It includes some of the film images used in the Rio TVCs: the two rowers in a rowing shed watching a sporting event on a mobile phone before going for a row; and the two elderly swimmers watching a swimming race beside an ocean-side swimming pool before swimming laps. The voiceover is in the following terms: “[w]ith Telstra, score a massive 10 gigs of data on the Samsung Galaxy S7, for just $95 a month for 24 months on Australia’s fastest mobile network”. The words displayed over the images at first state “10GB data for $95/mth for 24 months, includes 4GB bonus min. cost $2,280” and then changes to say “Australia’s fastest mobile network.”

29 The Telstra Samsung TVC does not expressly refer to the Rio Olympics or the Olympic Games, either in the voiceover or the written messages. Nevertheless, the advertisement is Olympic themed. The “I Go to Rio” song is an obvious reference to the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games, particularly when accompanied by images of rowers and swimmers (albeit that the swimmers, at least, are obviously not Olympic swimmers) watching sporting events on a mobile phone.

30 This advertisement was broadcast between 3 July and 5:00 pm on 8 July 2016. It was also broadcast in four New South Wales and one Australian Capital Territory sports stadiums, during one netball and four rugby league games.

31 The second Telstra Samsung advertisement (revised Telstra Samsung TVC) is essentially the same as the first. The only difference is that, for the first 7 seconds of the 15 second duration of the video, the disclaimer “Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams” appears at the foot of the screen in fairly prominent script.

32 The revised Telstra Samsung TVC was broadcast from 9 July to the evening of 12 July 2016.

33 The third Samsung advertisement (further revised Telstra Samsung TVC) is the same as the second, other than that the disclaimer appears for slightly longer (11 seconds). This version was broadcast from the evening of 12 July to 17 July 2016 and was intended to be re-broadcast from 7 August 2016. It was also broadcast in two sports stadiums in New South Wales and Western Australian during four rugby league games.

34 There are four versions of a video advertisement which was displayed on third party websites prior to the commencement of other video media.

35 The first version (original soccer pre-roll) utilises the video images also used in the Rio TVCs of the girls playing soccer and watching soccer on a mobile device. The soundtrack is the “I Go to Rio” song and the voiceover is the same as the original Rio TVC. The advertisement also uses the same written messages as the Rio TVC: “Australia’s fastest mobile network” and “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”.

36 This version of the website video was utilised during the period 3 to 7 July 2016.

37 The second version (revised soccer pre-roll) is similar to the first. There are two main changes. First, the voiceover is changed to the voiceover used in the revised Rio TVC: “[t]his August all Telstra mobile customers will have free premium access to every event live on Seven’s Olympics on Seven app. Enjoy the action on Australia’s fastest mobile network.” Second, the disclaimer appears at the foot of the screen during the first 11 seconds of the 15 second duration of the advertisement. This version first appeared on 13 July 2016.

38 The third version (original farm pre-roll) uses some of the same video images as the Rio TVC’s: the father and son driving in the country and the boy leaping a gate like a gymnast; and the children in a taekwondo class watching an event on a tablet. The voiceover is the same as the Rio TVC and original soccer pre-roll, as are the words displayed on the screen. Once again the “I Go to Rio” soundtrack is used. This version of the video was used between 3 and 7 July 2016.

39 The fourth version (revised farm pre-roll) was modified in the same way that the revised soccer pre-roll was modified. The voiceover is the same as the revised Rio TVC and the disclaimer appears at the foot of the screen for the first 11 seconds of the advertisement. This version of the video was first utilised on 13 July 2016 and continues to be available on various websites.

40 There are effectively two different catalogues that contain material challenged by the AOC.

41 The first was Telstra’s retail catalogue for July 2016. It was distributed in various ways from 28 June 2016. Telstra has advised that it cannot be withdrawn from distribution. A version of this catalogue was also distributed in National Broadcast Network (NBN) launch areas in early July 2016. It is apparently not intended to be redistributed.

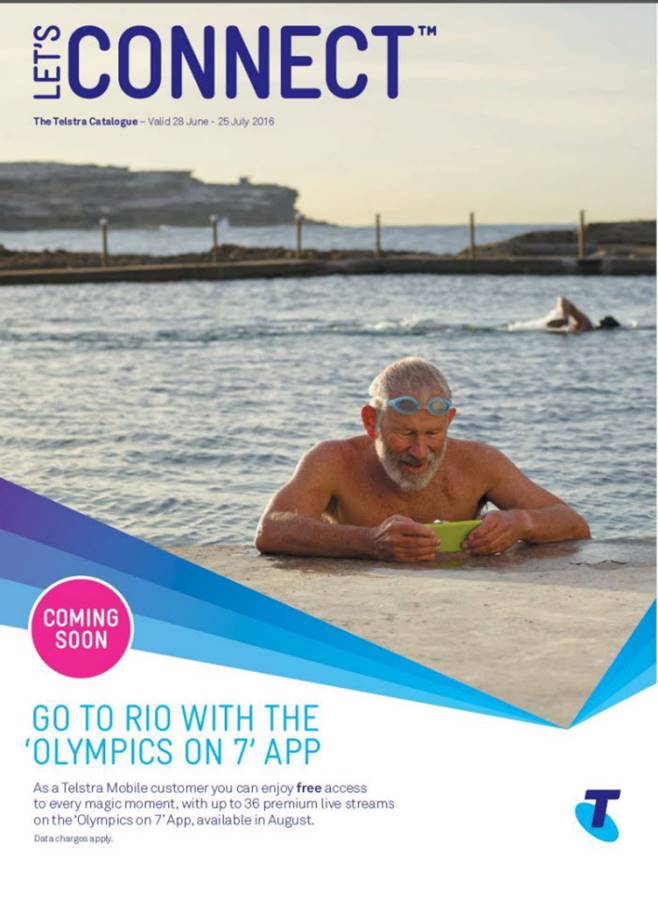

42 The front cover of the July catalogue includes a photo image of one of the elderly swimmers featured in the Rio TVCs. He is leaning out of an ocean-side pool and looking at a mobile device. The words “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” appear prominently. The following words then appear: “[A]s a Telstra mobile customer you can enjoy free access to every magic moment with up to 36 premium live streams on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, available in August.”

43 A copy of this cover is annexed to these reasons.

44 On the second page inside the catalogue there is an image of young female soccer players grouped together looking at a tablet device. The words “catch every magic moment” appear in prominent script. The following words then appear:

For the first time ever, watch every goal scored, every record broken and every medal won.

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, you can catch more of the action than ever before, with premium access to up to 36 live streams of Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games.

And as a Telstra Mobile customer, you’ll get premium access for free!

So get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App and go to Rio this August.

To find out more go to telstra.com/7rio

Data charges apply.

45 The second catalogue is Telstra’s August retail catalogue. It has been distributed in various ways since 26 July 2016. On the sixth page of the catalogue there is a full page image of a taekwondo instructor with a number of children wearing taekwondo outfits. The instructor is holding a tablet device which he and the children appear to be watching. In the top left hand corner the following words appear in prominent script, “Go to Rio, free” followed by smaller script, “Every Telstra Mobile customer can go to Rio with free premium access”. In a box in the bottom left hand corner the following appears:

There’s never been a better time to connect to Australia’s best mobile network, you’ll be sure to get the most from your new phone.

‘Olympics on 7’ App

Watch every sport and every game live from Seven’s coverage of Rio. Telstra Mobile customers can catch every magic moment with free premium access to up to 36 live streams on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App.

Download 1 August 2016.

Find out more at telstra.com/7rio

Data charges apply.

Telstra is not an official sponsor of the Olympic Games, any Olympic Committees or teams.

2.2.5 Telstra’s authentication “landing page”

46 Under the terms of its agreement with Seven, Telstra was required to set-up an “authentication” website landing page. On that page, persons who were confirmed as Telstra subscribers or customers could sign up for premium access to Seven’s Olympics on 7 app.

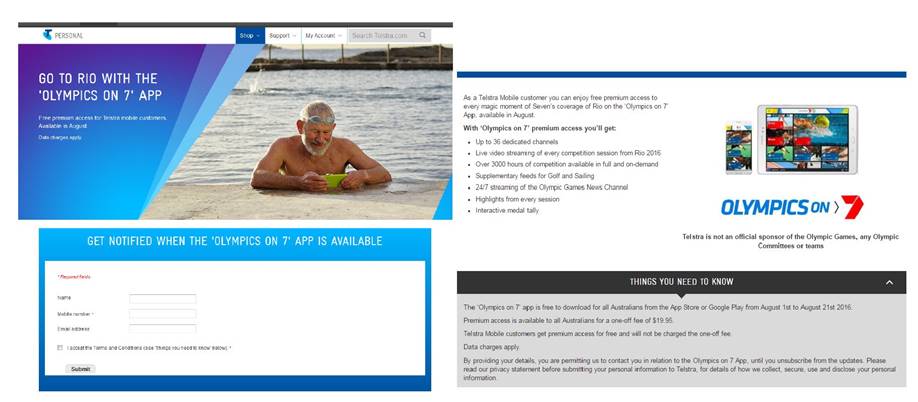

47 Three versions of the landing page were set up by Telstra. The first version was accessible on Telstra’s website for the period 28 June 2016 to 7 July 2016. That page included a prominent image of the elderly swimmer looking at his mobile device poolside, adjacent to the prominent script: “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” followed by the words, in smaller script: “Free premium access for Telstra Mobile customers”.

48 The page also included a prominent graphic of the words “Olympics on 7” utilising Seven’s “7” logo. Under that graphic the following words appear:

As a Telstra Mobile customer you can enjoy free premium access to every magic moment of Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games on the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, available in August.

With ‘Olympics on 7’ premium access you’ll get:

• Up to 36 dedicated channels

• Live video streaming of every competition session from Rio 2016

• Over 3000 hours of competition available in full and on-demand

• Supplementary feeds for Golf and Sailing

• 24/7 streaming of the Olympic Games News Channel

• Highlights from every session

• Interactive medal tally

49 Adjacent to those images there are images of two mobile phones and a tablet device containing what appear to be images of Olympic athletes or events. Under those images the followings words appear: “Seven’s Olympic Games Broadcast is proudly supported by Seven’s official technology partner, Telstra”.

50 Under the banner “Things you need to know”, the following writing appears:

The ‘Olympics on 7’ app is free to download for all Australians from the App Store or Google Play from August 1st to August 21st 2016.

Premium access is available to all Australians for a one off fee of $19.95.

Telstra Mobile customers get premium access for free and will not be charged the one off fee.

Data charges apply.

By providing your details, you are permitting us to contact you in relation to the Olympics on 7 App, until you unsubscribe from the updates. Please read our privacy statement before submitting your personal information to Telstra, for details of how we collect, secure, use and disclose your personal information.

51 An image of the original landing page is annexed to these reasons.

52 On 7 July 2016, the content of the landing page was changed in two ways. First, the position of the “Olympics on 7” graphic was moved so it appeared under the images of a mobile phone (now only one) and tablet. Secondly, the words that originally appeared under those images no longer appear. Instead, the disclaimer, in reasonably prominent script, appears under the ‘Olympics on 7’ graphic. This version of the landing page remained available until 12 July 2016.

53 On 12 July 2016, the landing page was changed again, albeit in a fairly minor way. In this version, which is the current version, the disclaimer appears in two places. It appears under the prominent script “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App”, as well as immediately above the “Things you need to know” banner. An image of the current version of the landing page is also annexed to these reasons.

54 Documentary evidence was led by Telstra, which demonstrated that the IOC had approved an earlier “mock” version of the landing page. That version did not contain the image of the swimmer. It did, however, include virtually all of the written content of the original version of the page that was available on Telstra’s website from 7 July 2016. It did not include the disclaimer. His Honour found, and it is not challenged on appeal, that the evidence demonstrated that the mock webpage was submitted to the IOC by Seven on 16 June 2016 and was approved by the IOC, subject to minor and, for the purposes of this proceeding, immaterial provisos, on 23 June 2016.

2.2.6 Retail point of sale materials

55 The retail point of sale materials appeared at various times from 28 June 2016 in certain Telstra branded stores and Telstra third party dealer stores. They comprised digital menu boards and media fountains, A4 posters, A5 tear pads and other materials.

56 The common features of this material include: still images of the elderly swimmer, taekwondo class or young female soccer players taken from the Rio TVCs or website materials; the words “Go to Rio with the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and variations of the written message that Telstra mobile customers were able to get free access to the Olympics on 7 app containing live streams of Seven’s coverage of the Rio Olympic Games. From 26 July 2016, all of the materials have included the disclaimer in fairly prominent script.

57 The agreed facts included seven additional samples of digital materials that either appeared on third party websites or were emailed to Telstra mobile or Telstra business customers. It is unnecessary to detail all of those items. In its submissions at trial, the AOC focused on only the following two.

58 On 1 July 2016, Telstra consumer mobile customers were sent a “KIT” (Keeping in Touch) email. It included the following introductory words:

For the first time ever, watch every minute of every event live from Seven’s Coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. With free premium access to up to 36 live streams of the ‘Olympics on 7’ App, you won’t miss any of the action. Data charges will apply.

59 The email then featured the image of the taekwondo class, the headline words “Get free premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and then the following written detail:

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, you can catch more of the action than ever before. And as a Telstra mobile customer you’ll get premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App for free, so you can cheer on your heroes right in the palm of your hand.

Get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App this August. Data charges will apply.

60 On 30 June 2016 eligible Telstra business customers were sent a “Business ideas e-newsletter”. One page of the newsletter featured an image of a tradesman viewing a tablet device alongside the heading “Get free premium access to the ‘Olympics on 7’ App” and then the following words:

Whether you enjoy the swimming, football or taekwondo, Telstra mobile customers can catch more of the action than ever before. Sign up for an eligible service and [you’ll] get premium access for free, letting you cheer on your heroes and watch records tumble, right in the palm of your hand. Get set to download the ‘Olympics on 7’ App and go to Rio this August.

(emphasis in original)

3. THE FINDINGS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

61 The primary judge reviewed each of the advertisements relied upon by the AOC.

62 In relation to the Rio TVC he found that while the Rio Olympic Games undoubtedly provided the underlying broad theme or story of the advertisement, the advertisement itself makes no express reference to or mention of the IOC, AOC or the Australian Olympic team or to any sponsorship or sponsorship-like association between Telstra and any of those bodies. The advertisements do not include any image of the Olympic symbol, flag or emblem, and the word “Olympics” is used twice, once in the voice-over as part of the expression “Olympics on 7 app”, and once in writing as part of the expression “Olympics on 7”. The expression “Olympic Games” is used once in the context of the phrase “Seven’s Olympic Games coverage”. The primary judge found that the specific theme or story of the advertisement concerns everyday Australians involved in watching Rio Olympic sporting events on a mobile phone or tablet. The broad message is that events at the Rio Olympics can be watched live on such devices using the Telstra network. The primary judge found that the hypothetical reasonable person may be taken to know that media and telecommunications companies ordinarily cannot broadcast live sporting events unless they have somehow paid for the rights to broadcast the event.

63 The primary judge found that the critical question in relation to the Rio TVC is whether it makes it sufficiently clear that Telstra’s sponsorship-like arrangement is with Seven, not with any Olympic body. He posed the question at J[91]:

Does it make it sufficiently clear that Telstra customers can watch the Rio Games on their mobile devices using the Telstra network because Telstra is Seven’s partner or sponsor, not because it has any arrangement with any Olympic body?

64 The primary judge found that the Rio TVC is somewhat borderline in that regard. There was a degree of ambiguity concerning Telstra’s connection with the Olympics on 7 app and the Olympic broadcast available on it. However, his Honour found that the nature of Telstra’s connection with the app and the Olympic Games broadcast is clarified to an extent in the last few seconds of the advertisement when the words “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage” and “Olympics on 7”, using Seven’s logo, appear. Those words suggest that “Telstra’s relationship in relation to the broadcast is with Seven, not any Olympic body”.

65 The primary judge rejected the AOC’s contention that it was relevant to consider Telstra’s advertisements in the much broader context of Telstra’s overall campaign, Seven’s own advertisements or facts such as Telstra’s past sponsorship of the Australian Olympic Team.

66 The primary judge also rejected two of the AOC’s further submissions; first, that Telstra’s internal marketing and promotions material indicated that its marketing and advertisements were intended to suggest a sponsorship-like arrangement with the IOC, AOC or other Olympic bodies. Second, that business records produced by Telstra tended to suggest that its advertisements led some consumers to believe that Telstra was in a sponsorship-like relationship with an Olympic body or bodies. Whilst his Honour did not find that evidence of consumers being relevantly misled is irrelevant (by analogy to an action under s 18 of the ACL), in the circumstances of this case he found it deserving of little weight.

67 Accordingly, although “borderline”, the primary judge concluded that the Rio TVC would not suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor of, or provided sponsorship-like support to, any Olympic body.

68 The primary judge considered that the revised Rio TVC more clearly did not contain the suggestion of sponsorship-like support. First, because of the content of the revised voice-over. Secondly, because of the disclaimer which appears in prominent script for the majority of the duration of the advertisements and makes clear that Telstra is not an official sponsor of any Olympic body. Thirdly, because the written message “Telstra is seven’s broadcast partner” makes clear, particularly when read in the context of the revised voice-over and disclaimer, that the Olympic coverage is able to be viewed using Telstra’s mobile network because customers can access Seven’s app which carries Seven’s broadcast. Accordingly, he found that Telstra’s sponsorship-like support is to Seven, not any Olympic body.

69 In relation to the website videos, the primary judge found that the original soccer pre-roll and the original farm pre-roll videos were, like the original Rio TVC, borderline, but that on balance, and for essentially the same reasons, did not cross the line to suggest to a reasonable person that Telstra was a sponsor of, or provided sponsor-like support to, any Olympic body. His Honour found that the revisions to include additional voice-overs, written messages and the disclaimer further reduced the likelihood of the suggestion.

70 The primary judge found that the Telstra catalogues employ the protected Olympic expressions twice, in the phrases “Olympics on 7 app” and “Seven’s coverage of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games”. Whilst the front cover of the July catalogue refers only to the “Olympics on 7 app” without explanation, his Honour found that on the second page it is made clear that the app is simply a means of accessing Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games and that Telstra customers are able to get premium access to the app for free. His Honour found that that would not make the relevant suggestion to a reasonable person but rather that, at most, it would suggest that Telstra customers could get access because of an arrangement between Telstra and Seven. His Honour found that the position is even clearer in relation to the August catalogue, which prominently includes the disclaimer. The primary judge made similar findings in relation to Telstra’s authentication “landing page” and concluded that it was unnecessary to consider the implications, if any, of the fact that Seven had procured the IOC’s approval of the substantive content of the landing page. Similar findings were made in relation to the point of sale and other digital material.

71 The primary judge concluded that the impugned marketing material would suggest to a reasonable person no more than the fact that Telstra’s customers can get free access to the Seven’s coverage of the Rio Olympic Games on their mobile devices via the “Olympics on 7 app”.

72 The primary judge considered that the AOC’s claim under the ACL hinged on the proposition that the relevant advertisements, taken individually or together, conveyed a representation or had a tendency to lead the audience of that material to assume that Telstra (or its services) had some form of endorsement, approval, sponsorship, affiliation or licensing arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games, the AOC, the IOC, the Australian Olympic team or the Olympic Movement generally. The only issue, he found, was whether, viewed individually or collectively, the advertisements conveyed that representation. If they did, there was no dispute that it would be false or misleading or constitute misleading or deceptive conduct.

73 After reciting the principles of law relevant to resolving the issues, which are substantially not in dispute in this appeal, the primary judge first identified the class of likely viewers of the advertisements as broad and wide ranging, and would include consumers who are unlikely to view the television commercials minutely and critically or scrutinise every aspect of them. The commercials would be viewed casually and subject to distraction. The viewer would most likely only take in the main message or theme. A lingering impression will most likely be of the music “I go to Rio”, but less so the appearance of the “7” logo on the screen of the mobile devices depicted.

74 The primary judge considered that the question for determination is very similar to that posed and answered in the context of the case under the OIP Act, although he noted that while the OIP Act case is concerned with the impression conveyed by the use of the protected Olympic expressions, the ACL case is more concerned with the overall impression conveyed, focusing not only on individual advertisements but on the “go to Rio” campaign as a whole.

75 Despite these differences, the primary judge concluded that the ACL case was not made out. In broad terms, he noted that it was not enough for the AOC to prove that the advertisements were Olympic themed. Were that so, any advertisement prior to the Rio Olympics that used Peter Allen’s song or depicted people playing or watching sport might be accused of misleadingly associating themselves with Olympic sport. In the case of Telstra, the position is complicated, the primary judge found, by the fact that it has entered into sponsorship-like arrangements with Seven in relation to Seven’s broadcast of the Rio Olympic Games. In this connection his Honour said:

139. … That arrangement included Seven providing Telstra customers with free premium access to the Olympics on 7 app through which Seven’s broadcast could be viewed. It is difficult to see how Telstra could be precluded from promoting or advertising the fact that it was a sponsor of Seven’s Olympic broadcast and was able to offer its customers free premium access to Seven’s app. It is equally difficult to see how Telstra could do so without in some way referring to the Rio Olympic Games, at least in the context of its sponsorship of Seven’s coverage or the ‘Olympics on7’ app. The thing that Telstra could not do is imply or intimate, by words, images or association, that it sponsored or had some other affiliation with an Olympic body or bodies.

140. The long and the short of it is that conduct by Telstra which amounted to nothing more than Telstra advertising or promoting its relationship and arrangements with Seven, including with respect to the Olympics on 7 app, could not fairly be regarded as misleading or deceptive. Representations which did not go much beyond conveying Telstra’s relationship and arrangements with Seven, including in relation to the Olympics on 7 app, would not, or would not be likely to, relevantly mislead or deceive. That would be so even if the advertisement plainly related to, or even sought to capitalise on or exploit, in a marketing sense, the Rio Olympic Games. …

76 Turning to the individual advertisements, the primary judge noted that the high point of the AOC’s case was the Rio TVC and the initial soccer and farm pre-roll web videos. He accepted that in those there was at least a lack of clarity or ambiguity about the precise character of Telstra’s connection or association with the Rio Games. The voice-over told the notional consumer that he or she could watch every event in Rio with the “Olympics on 7 app and Telstra” but it was not entirely clear what the app was and what Telstra’s association was with it. The addition of the words “and Telstra” might also suggest that Telstra had acquired the rights to that coverage from an Olympic body. That ambiguity, his Honour found, was remedied to an extent by the final written image in the advertisements, which includes the statement that Telstra was the “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage”. Seven’s relatively well known logo was also used in the words “Olympics on Seven”. The primary judge concluded that on balance five factors led to his conclusion that these advertisements do not convey the alleged misleading or deceptive conduct that Telstra sponsored or has an affiliation with an Olympic body. These were: the words “Olympics” and “Olympic” are only used as part of a composite expression “Olympics on Seven” or in the context of Seven’s coverage of the Rio Games; the advertisements do not refer to any Olympic body or use any Olympic emblem or symbol; the advertisements do not show images of any member of the Australian Olympic team; the sports people depicted in the advertisements are not Olympic athletes; the advertisements are about watching the Rio Olympics on a mobile device in circumstances where, ultimately, it is made clear enough that the Olympic Games coverage is Seven’s Olympic coverage. Accordingly, his Honour concluded, the message is that Telstra’s association, involvement or sponsorship was with Seven, not with any Olympic body.

77 The primary judge found that there could be no doubt that Telstra intended to and may well have succeeded in capitalising on or exploiting, in a marketing sense, the forthcoming Rio Olympic Games. It intended to, and may well have succeeded in, fostering some sort of connection or association between the Rio Olympic Games and the Telstra “brand”. It did so by effectively promoting its sponsorship arrangement with Seven in relation to Seven’s Olympic broadcast. Ultimately, the overall impression of the campaign was that Telstra customers could get premium access to Seven’s app and thereby get premium access to Seven’s coverage of the Olympic Games. That was because Telstra was Seven’s broadcast partner.

78 Having found that none of the individual advertisements conveyed the alleged misleading or deceptive representations, his Honour rejected the contention that collectively the Telstra campaign could be considered to have done so.

4. THE NOTICES OF APPEAL AND CONTENTION

79 The grounds of appeal relied upon by the AOC are as follows:

1. The primary judge erred in not finding that:

(a) (at [94], [103] and [124]) the Rio TVC;

(b) (at [110] and [124]) the revised and further revised Rio TVCs;

(c) (at [111], [114] and [124]) the original soccer pre-roll and the original farm pre- roll videos;

(d) (at [112], [114] and [124]) the revised soccer pre-roll and the revised farm pre-roll videos;

(e) (at [117] and [124]) the Telstra catalogues; and

(f) (at [123] and [124) the retail point of sale and other digital materials, including the KIT email,

(collectively the Advertisements)

would suggest to a reasonable person that the respondent was a sponsor of, or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for the Rio Olympic Games or the Australian Olympic team.

2. The primary judge erred (including at [4], [26], [87], [88], [91], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [100], [103], [106], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [114], [116], [117], [118], [120], [121], [123] and [124]) in limiting his consideration of the Advertisements to an association with any Olympic body, or any Olympic body or team, when he should also have considered whether any of the Advertisements suggested that the respondent was a sponsor of, or was a provider of sponsorship-like support for, the Rio Olympic Games.

3. The primary judge erred in not concluding at [124] and [151] that the respondent’s use of protected Olympic expressions in each of the Advertisements caused the respondent to contravene s 36 of the Olympic Insignia Protection Act 1987 (Cth) (OIP Act).

4. The primary judge erred in finding at [137], [140], [142], [144] and [148] that the respondent’s conduct in publishing or disseminating the Advertisements:

(a) was not misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(b) did not convey the representation that the respondent or its products or services had some form of endorsement, approval, sponsorship, affiliation, licencing or other sponsorship-like arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games, the Australian Olympic team or the Olympic Movement generally.

5. The primary judge erred in finding at [145], [146] and [148] that the respondent’s conduct in publishing or disseminating the Telstra Samsung TVC and the revised and further revised Telstra Samsung TVCs:

(a) was not misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(b) did not convey the representation that the respondent or its products or services had some form of endorsement, approval, sponsorship, affiliation, licencing or other sponsorship-like arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games, the Australian Olympic team or the Olympic Movement generally.

6. The primary judge erred (including at [4], [26], [129], [135], [137], [139], [140], [142], [143], [145] and [148]) in limiting his consideration of the Advertisements and the Telstra Samsung TVCs to an association with any Olympic body, or any Olympic body or team, when he should also have considered whether any of the Advertisements or the Telstra Samsung TVCs conveyed, or were likely to convey, or engender the impression that the respondent had some form of endorsement, approval, sponsorship, affiliation, licencing or other sponsorship-like arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games or the Olympic Movement generally.

7. The primary judge erred:

(a) in finding (including at [93], [94], [103], [105], [109], [114], [116], [123], [140]-[143] and [149]) that the association conveyed by the respondent’s advertising campaign was between the respondent and Seven’s Olympic Games broadcast and Olympic Games app when he should have found that the association conveyed or engendered was with the Rio Olympic Games or the Australian Olympic team; and

(b) in the alternative to ground (a), in proceeding (including at [91], [93], [103], [109], [142] and [149]) on the basis that a finding of an association conveyed by the respondent’s advertising campaign between the respondent and Seven’s Olympic Games broadcast and Olympic Games app precluded a finding that there was an association with the Rio Olympic Games or a relevant Olympic body which contravened the OIP Act or the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), when he should have concluded that both forms of association were conveyed or engendered.

8. The primary judge erred in concluding at [108] (and [112], [116], [143] and [146]) that the relevant disclaimers were capable of reversing or erasing any impression from the revised and further revised Rio TVCs, the revised soccer and the revised farm videos, the August Telstra catalogue, and the revised and further revised Telstra Samsung TVCs that the respondent was a sponsor of, or the provider of sponsorship like support for any Olympic body.

9. The primary judge should have concluded that none of the disclaimers:

(a) was capable of reversing or erasing the impression that the respondent was a sponsor of, or the provider of sponsorship like support for the Rio Olympic Games or the Australian Olympic team; nor

(b) was capable of reversing the representation, or causing it not to be conveyed, that the respondent or its products or services had some form of endorsement, approval, sponsorship, affiliation, licencing or other sponsorship-like arrangement with the Rio Olympic Games, the Australian Olympic team or the Olympic Movement generally.

10. The primary judge erred in not finding at [150] and [151] that by publishing or disseminating the Advertisements, the Telstra Samsung TVC and the revised and further revised Telstra Samsung TVCs (either individually or collectively) the respondent contravened ss 18 and/or 29(g) and/or (h) of the ACL.

80 In its Notice of Contention, Telstra asserts that the approvals or consents provided by the IOC to Seven obtained in accordance with the operation of the Seven agreement have a consequence that Telstra in fact had some form of consent, approval or endorsement from or on behalf of the Olympic movement generally in respect of the matters the subject of those approvals. Accordingly, Telstra contends that its conduct in publishing and disseminating the advertisements was in any event not misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive within the ACL.

81 Chapter 3 of the OIP Act concerns the use of protected Olympic expressions. It was introduced into the OIP Act in October 2001 by the Olympic Insignia Protection Amendment Act 2001 (Cth). In these reasons, reference is made to compilation no. 15 of the OIP Act dated 1 July 2016, which was provided to the Court by the parties.

82 The object of Chapter 3 is set out in s 22 as being to protect and to further the position of Australia as a participant in, and a supporter of, the world Olympic movement. This object is to be achieved by facilitating the raising of licensing revenue through the regulation of the use for commercial purposes of certain expressions associated with the world Olympic movement.

83 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Olympic Insignia Protection Amendment Bill 2001 (Cth) addresses the introduction of Chapter 3 into the Act. It provides at its commencement that:

The overall objective of this Bill is to protect, and to further the position of Australia as a leading participant in, and supporter of, the world Olympic movement. It reflects the government’s commitment in the Backing Australia’s Sporting Ability-a More Active Australia sports policy to encourage sporting organisations to deliver sporting excellence through self-sustaining, innovative funding arrangements. This will be achieved by giving the AOC a more certain environment in which to generate greater levels of sponsorship revenue from the private sector to fund its Olympic programs through the licensing of the Olympic expressions for commercial use in advertising and promotions.

Providing this protection for the Olympic expressions will strengthen the AOC’s fundraising abilities and help achieve the government’s elite sports objectives, such as maintaining Australia’s high level of performance at the Olympic Games. This level of protection should not unreasonably encroach on the rights of others who wish to promote their own association with an Olympic Games. In today’s sophisticated marketing environment there are many words (including ‘Olympian’) and images available to enable Olympians and others who have been involved in an Olympic Games to promote their association with the Olympics. Moreover, the protection will only prohibit commercial uses of the Olympic expressions where that use suggests a sponsorship or other like arrangement with the Olympic movement.

84 The Regulation Impact Statement for the Olympic Insignia Protection Amendment Bill 2001 (Cth) relevantly notes at page 3:

The proposed protection will increase the AOC’s ability to maximise its fundraising by extending the scope of its exclusive licensing rights and assisting in the prevention of ambush marketing. Ambush marketing is the unauthorised association of businesses with the marketing of high-profile events without paying for the marketing rights. Because it is targeted at preventing ambush marketing the proposed protection will add value to the AOC’s licensing rights by increasing the confidence of sponsors that any sponsorship arrangement they enter into with the AOC will not be ambushed by others who may wish to “freeride” by suggesting that they have a sponsorship-like Association with the AOC they do not [have].

85 The terms “Olympic”, “Olympic Games” and “Olympiad”, and their plurals, are the “protected Olympic expressions” (s 24(1)). Subsection 36(1) provides that a person, other than the AOC, “must not use a protected olympic expression for commercial purposes”. Subsection 36(2) provides that subsection (1) does not apply to the use by a person of a protected Olympic expression if the person is licensed to use that expression. In the present appeal there is no dispute that the AOC did not issue a license to Telstra to use any of the Olympic expressions. The Notice of Contention, however, raises the relevance of the approval obtained from the IOC.

86 A protected Olympic expression will be taken to be applied to goods or services if it is used in an advertisement that promotes the goods or services or is used in an invoice, pricelist, catalogue, brochure, business letter, business paper or other commercial document that relates to the goods or services (s 28(1)).

87 Section 30 sets out two situations in which a person is said to use a protected Olympic expression for commercial purposes (s 30(1)). The only presently relevant situation is set out in s 30(2). It provides:

Use for commercial purposes—situation (1)

(2) For the purposes of this Chapter, if:

(a) lied to goods or services of the first person; and

(b) the application is for advertising or promotional purposes, or is likely to enhance the demand for the goods or services; and

(c) the application, to a reasonable person, would suggest that the first person is or was a sponsor of, or is or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for:

(i) the AOC; or

(ii) the IOC; or

(iii) a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(iv) the organising committee for a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(v) an Australian Olympic team; or

(vi) a section of an Australian Olympic team; or

(vii) an individual member of an Australian Olympic team;

then:

(d) if the expression is applied in Australia—the application is use by the first person of the expression for commercial purposes; or

(e) if:

(i) the expression is applied to goods outside Australia; and

(ii) the goods are imported into Australia for the purpose of sale or distribution; and

(iii) there is a designated owner of the goods;

the importation is use by the designated owner of the expression for commercial purposes.

88 Section 29 of the OIP Act provides a definition of “sponsorship-like support”:

(1) For the purposes of this Chapter, a person provides sponsorship-like support for:

(a) the AOC; or

(b) the IOC; or

(c) a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(d) the organising committee for a Summer or Winter Olympic Games; or

(e) an Australian Olympic team; or

(f) a section of an Australian Olympic team; or

(g) an individual member of an Australian Olympic team;

if, and only if, the person provides support on the understanding (whether express or implied) that the support is provided in exchange for a right to associate:

(h) the person; or

(i) goods or services of the person;

with the committee, games, team, section or individual concerned.

(2) A right mentioned in subsection (1) need not be legally enforceable.

(3) An exchange mentioned in subsection (1) may be wholly or partly for the right mentioned in that subsection.

89 There was no dispute below, or on appeal, that in the Telstra advertisements (excluding the Telstra Samsung TVCs) Telstra applied the protected Olympic expressions “Olympic”, “Olympics”, and “Olympic Games” in Australia in relation to its services within the meaning of s 28. Nor was there any dispute that the application of these expressions by Telstra was for advertising or promotional purposes or was likely to enhance the demand for Telstra’s services being, broadly, Telstra’s telecommunications services. The focus of the dispute, rather, turned on the application of s 30(2)(c) and, in particular, whether the conduct of Telstra fell within the definition of “sponsorship-like support”.

90 The AOC contended before the primary judge that Telstra’s advertisements and other marketing or promotional materials, considered individually or collectively, conveyed a false or misleading representation, or involved misleading or deceptive conduct. As a result, the AOC alleged that Telstra contravened either or both of s 18 or ss 29(g) and (h) of the ACL.

91 Section 18 of the ACL provides as follows:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

92 Section 29(1)(g) and (h) are in the following terms:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation;

5.3 Propositions of law relevant to the OIP Act appeal

93 The statutory purpose of the OIP Act is, plainly enough, to ensure that the AOC is better equipped to protect its income stream through licensing than it would be under the application of the more generally worded consumer protection provisions of the ACL. The focus of the changes brought about in the 2001 amendments to the OIP Act is ambush marketing, which the explanatory memorandum explains is, “the unauthorised association of businesses with the marketing of high-profile events without paying for the marketing rights”. However, the OIP Act does not use the expression “ambush marketing”, and the scope of the protection afforded to the AOC in its revenue raising activities is to be ascertained from the language of the OIP Act itself. Despite the relevance of the statutory context by reference to secondary materials, the best indicia of Parliament’s intention as to the scope of the rights conferred is the statutory language itself; Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41; (2009) 239 CLR 27 at [47].

94 The issues in the present appeal direct particular attention to the language of s 30(2) of the OIP Act. Subsection 30(2) involves four cumulative requirements. First, that a person causes a protected Olympic expression to be applied to services of the first person (s 30(2)(a)). Secondly, that the application is for advertising or promotional purposes or is likely to enhance the demand for the goods or services (s 30(2)(b)). By s 28(2), an advertisement is taken to promote goods or services if it promotes a particular person, and the person provides services and it would be concluded, by a reasonable person, that the advertisement was designed to enhance the commercial image of the person promoted in the advertisement. Thirdly, that the application of the protected Olympic expression, to a reasonable person, would suggest that the person is or was a sponsor of or is or was the provider of sponsorship-like support for one or other of the following; the AOC, the IOC, a Summer or Winter Olympic Games, the organising committee for a Summer or Winter Olympic Games, an Australian Olympic team, a section of an Australian Olympic team or an individual member of an Australian Olympic team (s 30(2)(c)) (referred to below collectively as a relevant Olympic body). Fourthly, that the protected Olympic expression is applied in Australia (s 30(2)(d)).

95 Each requirement is prescriptive and reflects a Parliamentary intention to provide protection to the AOC’s revenue stream within the constraints set out therein. The presently relevant requirement is the third, set out in s 30(2)(c), in respect of which the following observations are apposite.

96 First, the words “the application” of the protected Olympic expression in s 30(2)(c) direct attention to the application of those words in a particular advertisement, in the context of that advertisement as a whole. An advertisement that does not use a protected expression is unlikely to fall within the section.

97 Secondly, the requirement that the application “to a reasonable person, would suggest” sponsorship or sponsorship-like support involves an objective test. As in a claim under s 18 of the ACL, it is necessary to consider the class of persons to whom the advertisements are directed and to consider the effect that the advertisement is likely to have on a reasonable member of that class; see, by analogy, Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [103] (Campomar) (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

98 In this connection, the context of the relevant advertisement must be taken into consideration. For instance, for the television commercials, considerations such as those identified in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 (ACCC v TPG) at [47] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ) arise (footnotes omitted):

… Here, the advertisements were an unbidden intrusion on the consciousness of the target audience. The intrusion will not always be welcome. The very function of the advertisements was to arrest the attention of the target audience. But while the attention of the audience might have been arrested, it cannot have been expected to pay close attention to the advertisement; certainly not the attention focused on viewing and listening to the advertisements by the judges obliged to scrutinise them for the purposes of these proceedings. In such circumstances, the Full Court rightly recognised that “many persons will only absorb the general thrust”. That being so, the attention given to the advertisement by an ordinary and reasonable person may well be “perfunctory”, without being equated with a failure on the part of the members of the target audience to take reasonable care of their own interests.

99 Thirdly, s 30(2)(c) requires a causal connection between the application of the protected Olympic expression and the reaction of a reasonable person. It is necessary to inquire whether, in the context of the advertisement, the use of the protected Olympic expression gives rise to the relevant suggestion; see, by analogy Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd [1978] HCA 11; (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228, 229 (Stephen J, Barwick CJ, Jacobs and Aickin JJ agreeing). Plainly enough, not all uses of a protected Olympic expression will result in a contravention. For instance, an advertisement that includes such words only in a disclaimer of any connection or association is unlikely to satisfy this requirement.

100 Fourthly, the statutory phrase “would suggest” in s 30(2)(c) does not connote that a “mere suggestion” is sufficient. The section uses the conditional verb “would”, which denotes the consequence of an event, and not the conditional verb “could”, which denotes a mere possibility or some likelihood. The use of “would” instead of “could” precludes the construction that rests upon a mere suggestion or some likelihood. The primary judge at J[80] found that the word “suggest” must bear its ordinary meaning, which includes, in this context, to “bring before a person’s mind indirectly or without plain expression; to call up in the mind (another thing) through association or connection of ideas” (Macquarie Dictionary); and “make known indirectly; hint at, intimate; imply, give the impression” (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary).” That construction is apposite. Taken together, “would suggest” may be understood to mean that the relevant meaning is more likely than not to be brought to mind. In any case, it is for the applicant to establish on the balance of probabilities that this is so.

101 Fifthly, the first form of impermissible suggestion identified in the subsection is that the person is or was a sponsor of one or more of the relevant Olympic bodies.

102 The second form of impermissible suggestion is that the person is or was the provider of sponsorship-like support. That expression is defined in s 29(1) of the OIP Act, set out in full at [88] above. A person provides sponsorship-like support for a relevant Olympic body (s 29(1)):

…

if, and only if, the person provides support on the understanding (whether express or implied) that the support is provided in exchange for a right to associate:

(h) the person; or

(i) goods or services of the person;

with the committee, games, team, section or individual concerned.

103 The term “support” is not defined in the OIP Act, but is relevantly defined in the Macquarie Dictionary as:

5. To maintain (a person, family, establishment, institution, et cetera.) by supplying with things necessary to existence; provide for.

6. To uphold (a person, cause, policy, et cetera.) by aid or countenance; back; second (efforts, aims, et cetera.)

104 The definition of sponsorship-like support creates a form of impermissible suggestion that is broader than “sponsorship”. The relevant suggestion may be that there is merely an understanding between a relevant Olympic body and the first person for instance that the first person provides a quid pro quo in return for a right to associate. The bargain suggested need not be of direct financial assistance. It could include, the provision of positive publicity, provided that a reasonable person views it as conveying the suggestion that the publicity is provided in exchange for a right to associate with a relevant Olympic body.

105 A particular advertisement may contain two or more relevant suggestions, one of which amounts to a suggestion that is prohibited. In each case it will be a factual question whether or not the Court is satisfied that such a suggestion is made.

106 In each case, it will be necessary to identify from the advertisement the relevant suggestion of support for the relevant Olympic body.

107 Some additional and uncontroversial observations may be made in relation to the approach to an alleged contravention of Chapter 2 of the OIP Act.

108 In assessing an advertisement, it is legitimate to consider evidence of consumers who have seen it and their reactions, but caution should be taken. In the context of a case where misleading or deceptive conduct is alleged, evidence from individual consumers that they have been misled by the impugned conduct is of limited utility. It has no statistical significance and the Court cannot draw inferences from it that any section or fraction of the population will have similar reactions. But if the inference is open, independently of such testimonial evidence, that the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then it may be that the evidence of consumers that they have been misled can strengthen that inference; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 234; (2015) 228 FCR 189 (Middleton J) at [94]; State Government Insurance Corporation v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales (1991) 28 FCR 511; 101 ALR 259 at 529 (French J, as he was then). Conversely, the absence of evidence of confusion may also be significant; for instance in cases where the impugned conduct has been going on for a considerable period of time, the applicant was aware of the need to obtain evidence to support its case and no such evidence was forthcoming; Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd (No 4) [2006] FCA 446; (2006) 229 ALR 136 at [81]. These observations are apposite, mutatis mutandis, to consideration of an advertisement under the OIP Act.

109 The intention of the advertiser may be relevant for reasons analogous to those considered in Australian Woollen Mills Limited v FS Walton & Co Limited [1937] HCA 51; (1937) 58 CLR 641 (Australian Woollen Mills), where at 657 Dixon and McTiernan JJ said:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive.

110 However, the role of intention should not be overstated. It is “simply one piece of evidence to be assessed with such other evidence as may be adduced on the issue”; Windsor Smith Pty Ltd v Dr Martens Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 756; (2000) 49 IPR 286 (Windsor Smith) at [33], [34] (Sundberg, Emmett and Hely JJ).

111 The Notice of Appeal advances ten grounds upon which the AOC contends that the primary judge fell into error. Many of the grounds are broadly expressed and amount to little more than assertions that the primary judge fell into error by not deciding in accordance with the AOC’s case, (see grounds 1, 3, 4, 5, 10). This is not particularly helpful, and does not fulfil the proper role of grounds of appeal – see the observations made in Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157; 234 FCR 549 at [5] (Branson J), [49] – [52] (Weinberg, Dowsett JJ). It has the tendency to leave it to the Court to trawl through the oral and written submissions in search for the basis upon which the appellant puts its case.

112 In the present case one aspect of the AOC arguments advanced on appeal, apparently in support of grounds 1, 3, 4, 5 and 10, is that the primary judge erred in reaching his conclusion that the Telstra advertisements did not evoke a connection with a relevant Olympic body, either for the purpose of the OIP Act claim or the ACL claim. It submits that the whole campaign focussed on “Rio” and that the Rio Olympic Games and Telstra’s involvement in those games constituted the “dominant story” portrayed in the individual advertisements. Taking the Rio TVC as the highpoint of its case, the AOC submits that the combined effect of the language, images and song used in the Rio TVC evoked a theme of ordinary people in effect, barracking for Australians at the Rio Olympic games and encouraged to do so by Telstra. That necessarily suggests a sponsorship or sponsorship-like support for a relevant Olympic body. As put by senior counsel for the AOC, when viewers see a person cheering on a televised Olympic event in the Telstra advertisement, they understand that Telstra is providing support to a relevant Olympic body. They would not think that “Telstra is going rogue” but rather that it is paying for the right to do so, and moreover was paying a relevant Olympic body for the privilege. The AOC submits that this was a point of emphasis that the primary judge failed to encapsulate in his summary of the Telstra advertisements and failed to find in his conclusions.

113 As part of this criticism, the AOC argues that the primary judge’s reasons reflect four further, specific errors. First, that the primary judge failed to give sufficient weight to his finding that Telstra’s advertising campaign was intended to convey an association with the Olympic Games or the Rio Olympic Games. Secondly, that the primary judge failed to give sufficient weight to his finding at J[25] that Telstra knew that it should not include words such as “Olympics” and “Rio” in its advertisements, but did so anyway. Thirdly, that the primary judge gave too much weight to the words appearing in writing (referred to below as the clarification) at the end of the Rio TVC (and similar words in other audio visual advertisements) “Official Technology Partner of Seven’s Olympic Games Coverage” and “Olympics on 7”, the “7” appearing in the form of Seven’s logo. Fourthly, that the primary judge failed to give sufficient weight to the response of a focus group member to the effect that an advertisement within the Telstra campaign may convey that it is “a sponsor of the Olympic games”.

114 We turn to consider these aspects of the appeal.

115 In this context, the role of this Court on appeal should not be misunderstood. The analysis of a judgment for appellate purposes does not require a fine parsing exercise and does not require overzealous analysis; Council of the City of Liverpool v Turano [2008] NSWCA 270 (Turano) at [160] (Beazley JA). A rehearing by way of appeal is not a new trial on the papers. Error must be shown. In Christian v Societe Des Produits Nestlé SA (No 2) [2015] FCAFC 153; (2015) 327 ALR 630 at [123] (Bennett, Katzmann, Davies JJ) a Full Court observed that in the context of a trademark dispute, the determination of whether a sign used as a trade mark is deceptively similar to a registered trade mark involves an evaluative exercise raising questions of judgment, nuance and degree upon which reasonable minds might differ. In a case of this kind, absent any relevant error of law or fact, weight should be given to the primary judge’s opinion. The degree of weight to be given to the primary judge’s opinion will depend on the nature of the issue under consideration. As Allsop J (as the Chief Justice then was) explained in Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [29]:

29. The degree of tolerance for any such divergence in any particular case will often be a product of the perceived advantage enjoyed by the trial judge. Sometimes, where matters of impression and judgment are concerned, giving ‘‘full weight’’ or ‘‘particular weight’’ to the views of the trial judge might be seen to shade into a degree of tolerance of divergence of views: cf S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 478 and 491; Turbo Tek Enterprises Inc v Sperling Enterprises Pty Ltd (1989) 23 FCR 331; Pacific Dunlop Ltd v Hogan (1989) 23 FCR 553; Allsop Inc v Bintang Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 686; Dart Industries Inc v Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 403 at 412; and Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 90 at 109-110 [27]. In such cases the personal impression or conception of the trial judge may be one not fully able to be expressed or reasoned: see, for example, Re Wolanski’s Registered Design (1953) 88 CLR 278 at 281 and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs v Charlesworth, Pilling & Co [1901] AC 373 at 391. However, as Hill J said in Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Chubb Australia Ltd (1995) 56 FCR 557 at 573 ‘‘giving full weight’’ to the view appealed from should not be taken too far. The appeal court must come to the view that the trial judge was wrong in order to interfere. Even if the question is one of impression or judgment, a sufficiently clear difference of opinion may necessitate that conclusion.

116 In the present case given the nature of the issues raised, it seems to us that his Honour’s views on the effect of the Telstra advertisements and the representations and suggestions they conveyed should be given considerable weight unless those views are shown to be affected by some relevant error of law or fact. The fact that in the present case another judge could have attributed different weight to a consideration which was undoubtedly taken into account by the primary judge, and by doing so, might have arrived at a different outcome, does not demonstrate error. To argue in this way does no more than to contend for a different conclusion to that which it was open to the primary judge to reach.

117 In relation to the broad challenge made to the conclusions of the primary judge as to the general thrust of the Telstra advertisements, the question is whether, after conducting a real review of the evidence at trial and of the primary judge’s reasons for judgment, the Full Court concludes that his Honour has fallen into error. For present purposes the high point of the AOC’s case on appeal, as at trial, lies in the Rio TVC. In the case of that advertisement, the primary judge considered the overall broad theme or story of the advertisement, including the imagery used and the use of the protected Olympic expressions and his interpretation of the message conveyed by the advertisement. He considered at J[88] that the broad message is that events at the Rio Olympics can be watched live on mobile phones or tablets using the Telstra network. His Honour then posed the question at J[91] whether the advertisement makes it sufficiently clear that Telstra customers can watch the Rio Games on their mobile devices using the Telstra network because Telstra is Seven’s partner or sponsor, not because it has any arrangement with any Olympic body. After further considering the spoken and written words in the advertisement, he considered that the advertisement conveyed, on balance, that Telstra’s relationship was with Seven, not with any Olympic body. His Honour then turned to consider specific matters raised by the AOC in its submissions, including Telstra’s intention in employing an Olympic expression and the responses to an internal Telstra survey. The primary judge considered both to be relevant to the OIP Act claim and the ACL claim. Ultimately, as we have noted, the primary judge considered that, on balance, and although the matter was not entirely straightforward, the Rio TVC did not convey the relevant suggestion or representation under either Act.

118 We have considered the Rio TVC and the balance of the Telstra advertisements and do not consider that the reasoning of the primary judge reflects error. The “going rogue” argument advanced by the AOC on appeal amounts to a contention that the primary judge missed the general point to the advertisement and failed to have regard to its overall message. However, it is plain from the primary judge’s reasoning that he had regard not only to the detail of its contents, but also to what was conveyed in a general sense. He did not miss the point, either in respect of the Rio TVC or the other Telstra advertisements.

119 The first specific argument that the AOC raises is that the primary judge failed to give sufficient weight to his finding that Telstra’s advertising campaign was intended to convey an association with the Olympic Games or the Rio Olympic Games. The primary judge found at J[98] that the Telstra marketing brief revealed that Telstra:

…wanted to be associated “in some way” with the Olympics and to create an overarching “brand idea” and platform that brings to life Telstra’s brand positioning of ‘empowering people to thrive in the connected world’ through the context of sports and the Olympic [G]ames” (whatever that means).