FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 138

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Within seven days, each party file an outline of submissions (of no more than three pages) on costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The first appellant is the patentee of Australian Patent No 744870 (the Patent) titled “Extension Drilling System”. The second appellant is the exclusive licensee of the Patent in Australia. For the purpose of these reasons, we will refer to the appellants collectively as Sandvik. The alleged invention relates to an extension drilling system (for use on a semi-automatic drilling rig) used to drill holes in subterranean mining operations, such as coal mining, where the structure of the roof of a tunnel is to be rendered more secure by the insertion of rock bolts into holes drilled into the roof structure. Extension drilling systems generally involve a number of extension rods which can be connected together to form a drill rod string. Each extension rod has a ‘male’ threaded coupling at the upper end and a ‘female’ threaded coupling at the lower end, with the ‘male’ end of one extension rod screwing into the ‘female’ end of another. In brief terms, the alleged invention involves a drive chuck, or an adaptor fitted to a drive chuck, attaching to and turning the outside surface of the female coupling of the extension rod at the bottom end of the drill rod string, in either forward or reverse direction. As explained below, this was said to overcome a problem associated with the removal of extension rods from the drill rod string after drilling had been completed.

2 In the proceeding below, Sandvik alleged that the respondent (Quarry Mining) had infringed claims 1-4 of the Patent. Sandvik sought declarations, injunctions, orders for delivery up, and damages or an account of profits. Sandvik also alleged that Quarry Mining’s conduct amounted to contraventions of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) and of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) and sought corresponding remedies under those provisions.

3 Quarry Mining cross-claimed for revocation of the Patent, in relation to claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, on grounds including lack of novelty, lack of inventive step, lack of utility, and failure to describe the best known method.

4 The primary judge held that Sandvik’s application should be dismissed and the cross-claim upheld. An order was made that, so far as it related to claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, the Patent be revoked.

5 Sandvik has appealed from part of the judgment and orders of the primary judge. Quarry Mining has filed a notice of contention. It is convenient to deal with the issues raised in the notice of appeal, and the notice of contention, in the following order:

(a) failure to describe the best method known to Sandvik;

(b) lack of novelty;

(c) lack of inventive step; and

(d) lack of utility.

6 In relation to each of those issues, our conclusions can be summarised as follows:

(a) In relation to the failure to describe the best known method issue, Sandvik has not established error by the primary judge.

(b) In relation to the lack of novelty issue, save in one respect, Sandvik has not established error by the primary judge.

(c) In relation to the lack of inventive step issue, we would uphold Sandvik’s grounds of appeal.

(d) In relation to the lack of utility issue, we would reject Sandvik’s grounds of appeal and reject the notice of contention.

7 Although Sandvik has been successful in respect of some issues, these do not affect the overall result. Accordingly, the appeal is to be dismissed.

8 It is useful to note at the outset that, throughout these reasons, reference will be made to the version of the reasons of the primary judge as published by the Court (and available for download on the Court’s website): Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 236 (the Reasons). The version published in the Intellectual Property Reports is, in some respects, not in the same form.

The relevant field of technology

9 The following description of the relevant field of technology is substantially drawn from the Reasons.

Overview, roof bolts and cable bolts

10 The field of technology with which the appeal is concerned is what is described as extension drilling in underground mines, specifically coal mines. Traditionally, the structural integrity of the roofs of underground roadways in coal mines was secured by the use of timber supports. Since the 1970s, however, bolting systems have been used for this purpose. For present purposes, it is only necessary to mention roof bolting and cable bolting. Both of these systems work to prevent roofs from collapsing by clamping together the layers of sedimentary material above the void constituting the roadway.

11 Typically, a seam of coal is about 3-5 m thick. The layers of sedimentary material above the coal seam often lack internal integrity. Roof bolting involves the insertion of a series of long solid bolts into the roof above the roadway. In order to do this, it is first necessary to drill holes into the roof of appropriate diameter and length to cater for the bolts. The length of roof bolts is typically within the range of 1.5-2.4 m. The lower end of the bolt is threaded to take a nut. The bolt is inserted into the drilled hole and secured, either by a mechanical means or using adhesive. The nut is then tightened against the surface of the roof. Often there will be a metal plate or washer between the nut and the roof surface to spread the load against the roof surface. The tensioned roof bolts lock, or ‘key’, the strata material together.

12 Cable bolts are long flexible bolts, typically in the order of 4-12 m in length. They comprise a series of twisted wire strands. Cable bolts are used in the same way as roof bolts in that they are inserted into the roof of an underground roadway in a mine. Although they are typically used at the intersections of roadways, cable bolts are also used wherever the use of standard roof bolts alone is insufficient to support the roof adequately and additional reinforcement is required.

13 The present appeal is concerned not with roof bolts and cable bolts as such, but with drilling systems for making the holes into which these bolts can be inserted. The appeal is specifically concerned with systems for making the long holes required for the insertion of cable bolts but, since the same power source is commonly used for each, it is convenient to move next to a generic explanation of the technology which is used for drilling roof holes in underground mines.

14 There are two types of drilling techniques (and associated machinery and equipment) used in mining, namely, rotary percussive drilling and non-percussive rotary drilling (often referred to simply as ‘rotary drilling’). Rotary percussive drilling is typically utilised where the strata to be drilled has a compressive strength greater than 60 MPa, and involves a rotating drill bit which is hit with a high frequency hammer to burst the strata. Rotary (ie, non-percussive) drilling does not involve percussion, but the strata are cut away in a manner which is similar to drilling timber with a hand drill. In percussive drilling, the drilling rotation is anticlockwise. In (non-percussive) rotary drilling, the rotation is clockwise. Coal is relatively soft, thus percussive drilling is rarely required. The drilling of holes for roof bolts, rib bolts and cable bolts in coal mines is almost always done using (non-percussive) rotary drilling equipment.

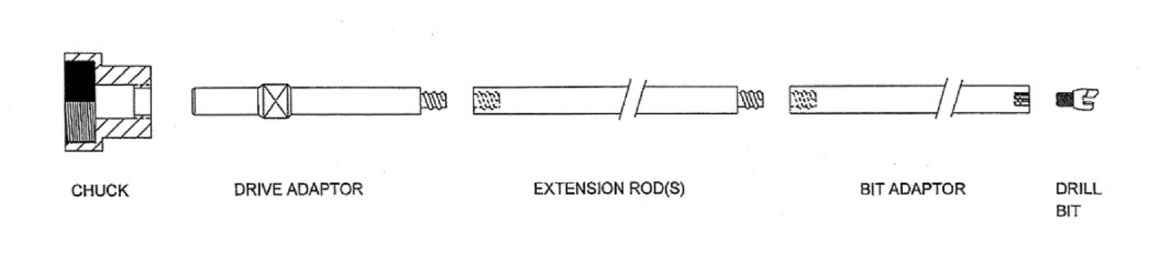

15 The types of equipment used in the drilling process may be either hand-held or machine-mounted roof bolters. Hand-held roof bolters are lightweight portable units, the vast majority of which are pneumatically powered. They are relatively low powered units operating at around 100 to 150 psi, being the realistic maximum compressed air pressure available underground due to reticulation losses. In practice, this relatively low power capacity means that the drilling power (feed force, torque and rotational speed) able to be generated is also quite low. Thus units of this kind are limited in their ability to drill quickly and efficiently. There are also hydraulically powered hand-held portable roof bolters, but such units are also low-powered. For a number of presently irrelevant reasons, over time the use of hand-held bolters has become increasingly rare.

16 There are two types of machine-mounted roof bolters, namely, stand-alone roof bolters and bolters incorporated as a part of a continuous miner. Typically stand-alone roof bolters are mounted on vehicles which run on caterpillar tracks and can be driven to position. These vehicles may carry one or more bolters, or ‘drilling rigs’. Usually the machine is operated by one or more operators who can drive the machine and operate the roof bolter.

17 In the case of a roof bolter which is incorporated into a continuous miner, the bolter itself is essentially the same as that found on a stand-alone bolter. There will normally be at least two bolters, one on each side of the machine, so that a row of bolts can be inserted into the roof across the width of the roadway. The bolters can be angled so that one bolt is inserted vertically and a second inserted at an angle.

18 Machine-mounted bolters are hydraulically powered, typically with an operating pressure in the order of 3000 psi. This provides far greater torque and drilling speed compared with pneumatically powered hand-held bolters.

19 Having set out the relevant technology in general terms, it is convenient first to describe ‘single-pass’ drilling, and then to describe extension drilling.

Single-pass drilling

20 The main components of a machine-mounted roof bolter are the drilling rig, or mast, and the drill. For a layperson, the best starting-point is to imagine a common maintenance person’s electric drill, which drives through a chuck into which a drilling bit is inserted and secured. In roof bolt drilling, there is likewise a drill with a chuck, and the chuck receives the drill bit, referred to as a ‘rod’ since it will generally be at least long enough to facilitate the drilling of a hole to receive a roof bolt of 1.5 m in length. This drill, with chuck and rod, is mounted on a mast the top portion of which, called the headplate, is pressed against the roof of the mine where the hole is to be drilled. In the drilling operation, the drill is moved upwards along the mast as the rotating drill rod cuts the required hole into the strata above.

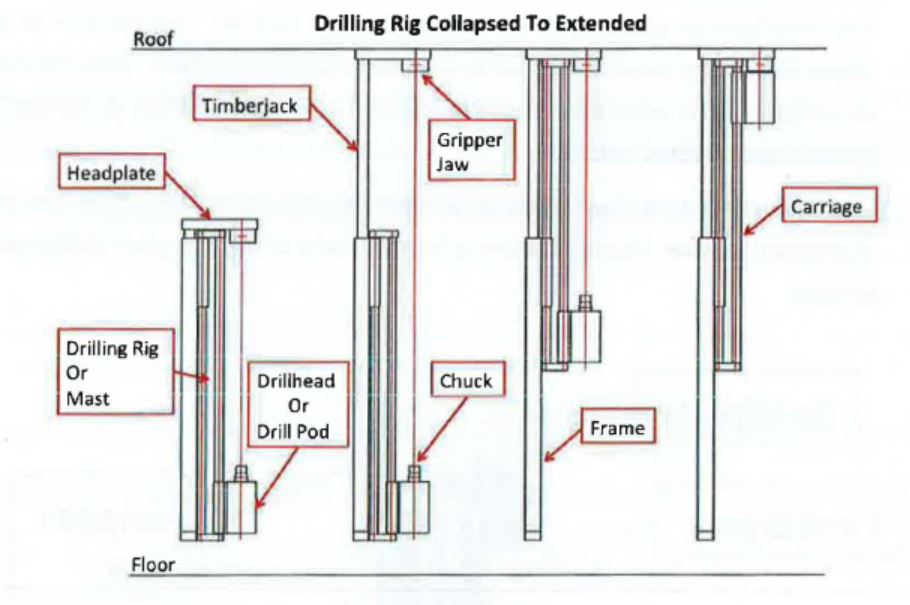

21 In his affidavit at trial, Mr Charlton presented the following diagrammatic representation of the various stages of the drilling operation:

The above diagram is also relevant for the explanation of extension drilling, set out below.

22 The mast is shown in its collapsed state on the left hand side with the drillhead, or drill pod, at its lowermost position. In the next stage, the timberjack is raised so that the headplate makes contact with the roof. The headplate steadies the drilling rig and provides a guide for the drill rod once it has been placed in the chuck. Attached to the headplate are ‘gripper jaws’, the purpose of which will become clear below, but which do not perform a function in single-pass drilling. It is sufficient here to note that the drill rod will pass through these jaws. At this stage, the drill rod has been placed in the chuck, its alignment being indicated by the thin red line running between the chuck at the lower end and the gripper jaws at the upper end. In the third stage, drilling has commenced. The ‘drill chuck apparatus’ has moved about halfway up the mast. The cutting end of the drill is doing its work in the strata above. When the drill chuck apparatus reaches the underside of the headplate, the drilling process is complete (the diagram on the right-hand side), and the process is reversed. The apparatus is lowered, and the drill rod withdrawn from the roof of the mine. An operation such as that outlined here is referred to as single-pass drilling.

23 The drill rods used in single-pass drilling are metal, typically of either hexagonal or round cross-section. They do not include an integral cutting/drilling tip; rather, they are threaded at one end to accommodate the attachment of a cutting tip. The other end of the drill rod forms the drive shaft of the rod. The drive shaft of single-pass drill rods is configured to fit into, and be driven by, the drive chuck of the drill machine. The standard drive chuck used in hydraulically powered roof bolters is the ‘square locking chuck’. This chuck, and complementary square drive drill rods, were developed in Australia in the mid-1980s, and have been the standard in conjunction with hydraulic roof bolters in the coal mining industry since the early 1990s.

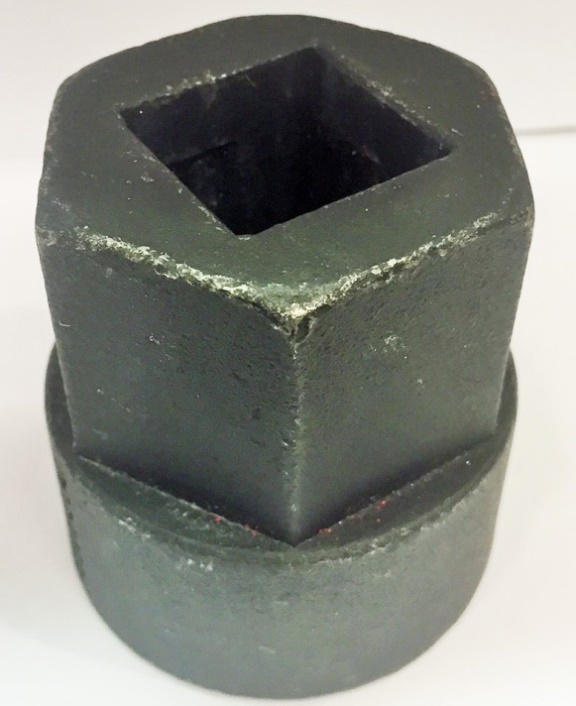

24 An example of a standard 25 mm square locking chuck is shown below, from above (left-hand photograph) and from below (right-hand photograph).

25 The chuck has an upper, a middle and a lower part. The upper part consists of a square opening (as shown on the left-hand photograph above) slightly larger than the cross section of the square section of the drill rod. The lower part consists of an internally-threaded cylindrical section (as shown on the right-hand photograph above) which screws onto the matingly-threaded upper end of the driven shaft of the drill motor. The middle part (not fully visible in the photographs above) consists of the drive chamber of the chuck.

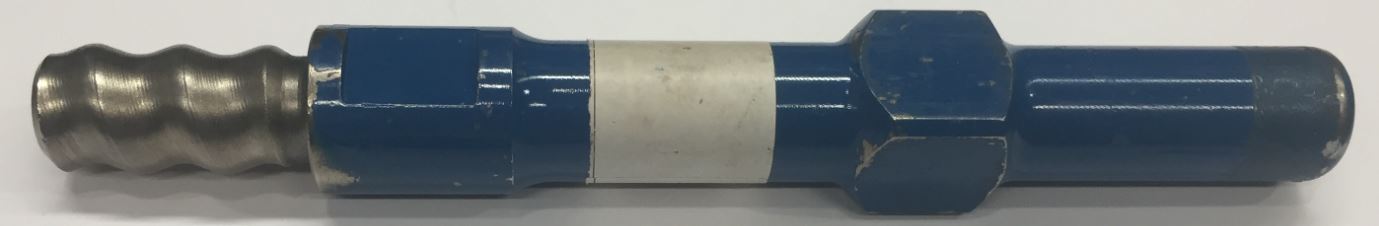

26 An example of the driven end of a single-pass drill rod of the kind used in connection with the chuck described above is shown below.

In the above photograph, the spigot (discussed below) appears on the left.

27 With the chuck installed on the drill and ready for use, the drill rod is inserted into the chuck by passing first the round section and then the flat-sided, or square-shaped, section through the hole in the upper part of the chuck, to the point where the square section lies wholly within the middle part, or drive chamber, of the chuck. The drive chamber has a series of 12 angled faces in a cross-like configuration and is slightly larger than the square section of the rod, such that the rod may rotate relative to the chamber by about 20 degrees. Once rotated relative to the chuck, the square section of the rod is no longer aligned with the opening of the chuck and is prevented from pulling out of the chuck by the lip of the chuck opening. The configuration of the chuck and the drive shaft is such that, when the chuck is operating, the drill rod is locked in place and cannot come out of the chuck. This is a safety measure as it ensures that, when the drill chuck apparatus is lowered after the completion of drilling, the rod is not left dangling in the roof hole with the risk that it might fall onto operators below; the rod remains secured in the chuck until removed manually.

28 The round section at the lowermost end of the rod (ie, below the square section) is referred to as the ‘spigot’. It has at least three relevant functions. First, it sits on the base of the chuck and takes the weight of the rod. Secondly, it fits into a corresponding piece in the chuck from which flushing fluid is passed into it and up the drill rod, an important subject which we refer to in more detail below. Thirdly, it fits inside, and thus forms a seal with, an O-ring in that corresponding piece to prevent leakage of the flushing fluid at this point. For that purpose, self-evidently, this spigot must be circular in profile.

Extension drilling

29 Where cable bolts are to be used, drill rods of the kind described above are not long enough to drill holes of the required depth. Because of limitations imposed by the height of the mine roadway, to use a single drill rod long enough to drill a hole of up to 12 m in depth would be out of the question. Thus the drill rod used is in fact a string made from round or hexagonal sections of drill rod attached together at their complementary male and female threaded ends. By convention, the upper end of each rod is male threaded and the lower end of each rod is female threaded. The thread employed in the technology relevant to the present proceeding is right-hand rope thread. Individual rods come in varying lengths, typically from about 0.5 m to 2 m. The first, or uppermost, rod is adapted to receive the drill bit.

30 Ignoring for the moment the means by which the driven end of the lowermost rod communicates with the chuck, at a general level it may be said that drilling for cable bolts involves: using a first drill rod with the bit attached to its uppermost end to drill into the mine strata until the length of that rod has been exhausted (in much the same way as done in single-pass drilling); then connecting a second rod between the chuck and the first drill rod and drilling again until the length of the second drill rod is used up; then connecting a third drill rod between the chuck and the second drill rod, and so on, until a hole of the length required to accommodate the cable bolt intended to be used has been made. Each time a new rod is connected to its predecessor (ie, the one that has been almost wholly driven into the roof strata), the drill chuck apparatus must be lowered down the drill mast to make room for the new rod. Because the drill string consists of a series of rods built up as drilling proceeds, this technology is referred to as ‘extension drilling’.

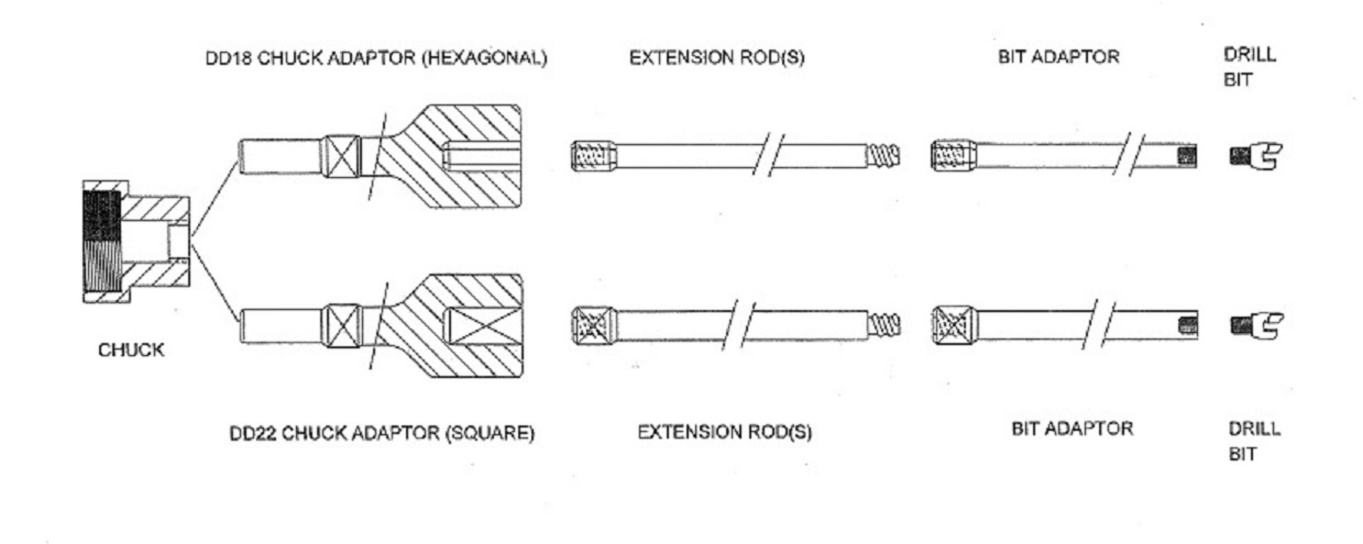

31 It will be immediately apparent that, since each rod must have, at its lower end, an internal female thread shaped to receive the upper male-threaded end of the next rod, the lower end of any one of these rods could not be fitted with a spigot arrangement of the kind commonly found on rods used in single-pass drilling, as depicted above in the photograph at [26]. The expedient which, sometime before the priority date (11 June 1997), had come to be used to deal with this issue was the inclusion of an ‘adaptor’ (or ‘drive adaptor’ or ‘chuck extension’) between the chuck and the lowermost drill rod. At its lower end, such an adaptor had the same cube-and-spigot arrangement as was used on single-pass drill rods. At its upper end, it was fitted with a male thread to engage with the lowermost rod. It was an important aspect of Sandvik’s case at trial that roof bolting contractors in the coal mining industry saw this expedient as more convenient than having to change the chuck on a drilling machine each time it was necessary to undertake extension, as opposed to single-pass, drilling. Indeed, the mining experts called by both parties were agreed that, as a generalisation, contractors would not contemplate changing a chuck underground during the course of a roof bolting program. An example of an adaptor, such as that described above, is the following:

In the above photograph, the upper end of the adaptor (with male thread) appears on the left, and the lower end of the adaptor (with the cube-and-spigot arrangement) appears on the right.

32 Using the equipment referred to above, the process for extension drilling involves the following steps:

(a) insert a drive adaptor into the drill chuck;

(b) attach a first extension rod (with drill bit included) to the drive adaptor;

(c) raise the drill chuck, commence drilling and drill to the full length of the first extension rod;

(d) cease drilling and clamp the gripper jaws onto the lower end of the first extension rod just above the coupling of that rod and the adaptor;

(e) reverse the rotation of the chuck to uncouple the first extension rod from the adaptor;

(f) lower the drill chuck;

(g) attach the top of a second extension rod to the lower end of the first extension rod to create a drill string of (at this point two) extension rods;

(h) couple the adaptor to the bottom of the second extension rod;

(i) recommence drilling and drill to the full length of the second extension rod; and

(j) repeat steps (d) to (i), adding additional extension rods to the drill string until the desired length of hole has been drilled.

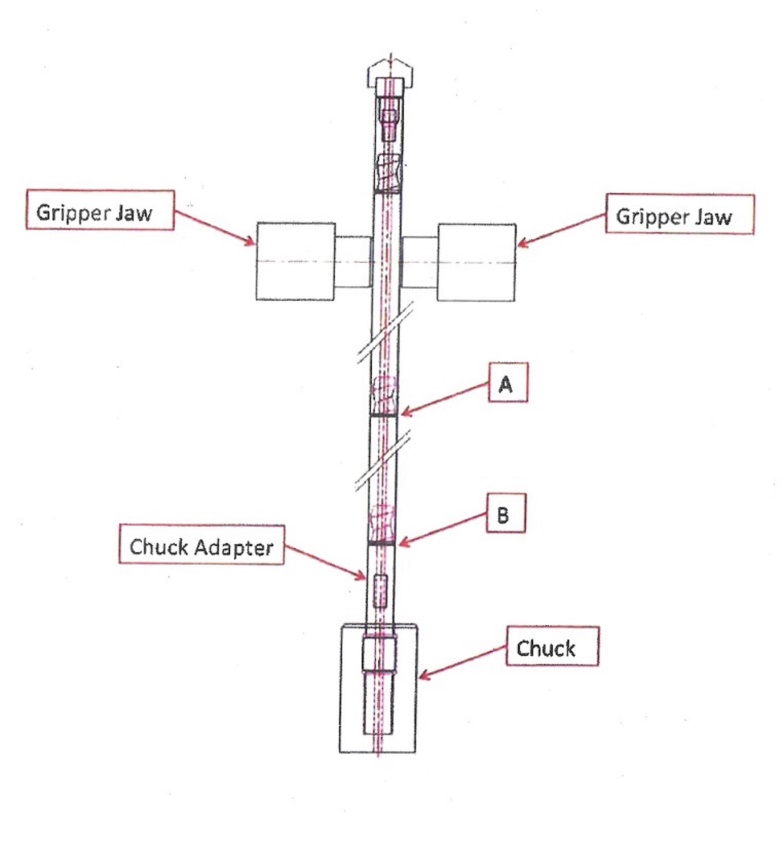

33 The following diagram, drawn from the evidence and provided to the Court at the hearing of the appeal, illustrates a conventional extension drilling system:

34 With respect to steps (d) and (e) in [32] above, the use to which the gripper jaws are put should now be evident. To uncouple the first (and subsequently each lowermost) extension rod from the drive adaptor requires an unscrewing action in which the rod must be held firmly in place while the machine causes the chuck, and therefore the adaptor, to rotate in the reverse direction. This point is illustrated by the following diagram, drawn from the evidence and provided to the Court at the appeal hearing:

As is apparent from this diagram, there are two threaded connections, marked ‘A’ and ‘B’, between the gripper jaws and the chuck. We return to this matter in the next paragraph.

35 Once the drill hole has reached the required depth, it is necessary to remove the drill string, which now consists of a number of extension rods connected together. Essentially, this process requires the sequential removal of each rod from the string. This must be done in stages. First, the chuck is lowered, bringing the drill string with it. To remove the lowest extension rod from the string requires that rod to be disconnected from the rod immediately above it. The string is lowered to a point where the connection between the lowest rod and the rod above it is immediately below the gripper jaws, such that, when those jaws are engaged, they grip the lower end of the upper rod. The drill is then operated in reverse, imparting an unscrewing action upon the drill string. Because the upper rod is held firm by the gripper jaws, it will not move. The following aspect of the removal process is important for the purposes of understanding the alleged invention. Between the gripper jaws and the chuck, there are now two points of threaded connection in the string, one between the adaptor and the lower rod (marked “B” in the above diagram) and the second between the lower rod and the rod above it (marked “A” in the above diagram). When the direction of the rotation of the chuck is reversed, one of those connections will come unscrewed. It may be either of them. The other connection must then be unscrewed manually, using a spanner.

36 Once the lowermost drill rod has been removed in the way described, the drill chuck apparatus is raised again along the mast to make connection with, and to screw into, the female end of the next rod which, it will be recalled, is just below the gripper jaws. The jaws are then released, the drill chuck apparatus, now with the remaining drill string attached, is lowered until the lower end of the next rod in line appears below the gripper jaws, the jaws are engaged at that point, and the process described above commences again. This pattern is repeated until all the sections of the drill string have been removed.

Other aspects of single-pass and extension drilling

37 One further common feature of extension (and single-pass) drilling which should be mentioned at this stage is the means by which cuttings from the action of the drill bit are cleared away. Here it must be understood that the bit is operating in a confined space and, absent some mechanism to prevent it, would soon become clogged with debris from its own action and would jam. Although there are some other methods employed, the most common method for addressing this problem in Australia is flushing with water continuously pumped through an axial passage in the drill rod or rods. This is the flushing fluid referred to in [28] above. On account of this feature, the drill rods which we have been discussing above, and the adaptors used in conjunction with them, are not solid but have a pipe-like configuration, allowing for the passage of flushing water. In order to inhibit the outflow of water contained inside the existing rods on the drill string at the point when the lowest connection is broken (to facilitate the insertion of the next rod), some or all of the rods are internally equipped with a non-return ball-valve arrangement.

38 While on the subject of flushing water, a practical issue of some importance should be mentioned. This water must be supplied to the drill string at a sufficient pressure to cause it to rise vertically, in a narrow tube, over a distance of anything up to about 12 m, and then to carry out the necessary flushing. In a system which involves so many joins, the potential for leakage, and loss of pressure, is apparent. There appears to be little practical difficulty with leakage at each male/female threaded connection between the various rods; the connection itself is sufficiently watertight to suit the purposes required. But there is a need for an effective seal at the point where a single-pass rod or an adaptor sits in the chuck. The spigot-and-O-ring arrangement referred to in [28] above was the means by which this problem had been addressed, both in the case of single-pass drilling, where the spigot was on the end of the drill rod itself, and in the case of extension drilling, where the spigot was part of the adaptor.

39 The primary judge stated, at [30] of the Reasons, that the matters set out in the paragraphs above represented the state of the art, and the common general knowledge, in the industry as at the priority date for the Patent, being 11 June 1997.

The Patent

40 The following description of the Patent is drawn substantially from the Reasons.

41 According to the specification:

This invention relates to an extension drilling system, and more particularly, but not exclusively, to extension drilling systems for use on a semi-automatic drilling rig and used to drill holes (bores) in subterranium [sic] mining operations such as coal mining where the structure of the roof of a tunnel is to be rendered more secure by the insertion of rock bolts into holes drilled into the roof structure.

42 The specification refers to two problems in the existing art, in the following terms:

The primary problem with conventional drill rods for extension drilling systems, when used with semi-automatic drill rigs is that, when the drill string (a series of drill rods coupled together) are to be uncoupled there are two threaded couplings between the grippers and the chuck. As the grippers are operated, and the chuck spun slowly in reverse, the threaded joint between the drive adaptor and the bottom extension rod can become uncoupled which is undesirable as distinct from the desired uncoupling between the bottom and second bottom extension rods.

A secondary problem is that the use of a drive adaptor takes up valuable boom height on the rig thus reducing the length of the extension rods that can be used.

(Emphasis added.)

43 The invention is then disclosed in the following terms:

According to the present invention there is provided an extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connected together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having co-operating a male and female right-hand rope threaded couplings at one end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at the other end, whereby the extension rods are connected together by coupling of the male coupling of one extension rod with the female coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods therebetween, a drive chuck of a drilling rig for driving the outside surface of a female threaded end coupling of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, selectively in either forward or and reverse directions, a set of grippers for preventing rotation of clamping an extension rod being arranged to clamp an extension rod at a location so such that only one male/female threaded coupling is provided located between the drive chuck and the set of grippers and so that with the grippers clamping the extension rod, and with the drive chuck being driven in the reverse direction, only the male/female coupling between the grippers and the drive chuck is uncoupled.

According to the present invention there is further provided an extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connectable together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at a male end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at a female end, whereby the extension rods are connectable together by coupling of the male end coupling of one extension rod with the female end coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods and wherein the external surface shape of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck of a drilling rig to drive the female end of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, and wherein the external surface shape of the extension rods between the female end and the male end is of a different and substantially uniform profile.

(Emphasis added.)

44 To a large extent, these passages in the specification amount to a recital of the prior art, as outlined above. Central to Sandvik’s case below and on appeal was the proposition that the invention departs from the prior art to the extent that it requires: the drive chuck (either directly or indirectly, using an adaptor) to drive “the outside surface of a female threaded end coupling of an extension rod”; and “the external surface shape of the female end [to have] a profile for engagement by a drive chuck”. So far as may be discerned from these passages, the essence of the invention lies in the mechanical engagement by the chuck of the lower end of the lowermost drill rod in the string. The “primary problem” identified in the specification is overcome because, at the stage of the removal of a rod from the string, there is now only one threaded connection between the gripper jaws and the chuck, namely, the connection between the rod being removed and the next rod above it which is held firm by the gripper jaws. The following diagram, drawn from the evidence and provided to the Court at the appeal hearing, illustrates the direct drive extension drilling system:

45 As noted in [42] above, a “secondary problem” referred to in the specification is that the use of a drive adaptor takes up valuable boom height on the drilling rig, thus reducing the length of the extension rods that can be used. While the invention described in the specification is capable of overcoming this, we note that in one of two preferred embodiments of the invention (discussed below), the use of an adaptor is prescribed by the specification.

46 The specification continues:

Preferably the extension rods have axial passages therethrough in communication with each other and through which flushing fluid is delivered to an associated drill bit. Preferably a non-return valve is incorporated in at least one of the extension rods to shorten the delay time in delivering flushing fluid to the drill bit before re-commencement of drilling after an extension rod is added to the extension rod string.

Preferably the extension rods are of hexagonal, cross-section or any other suitable cross-section and may be forged or welded rods which are selectively or fully heat treated.

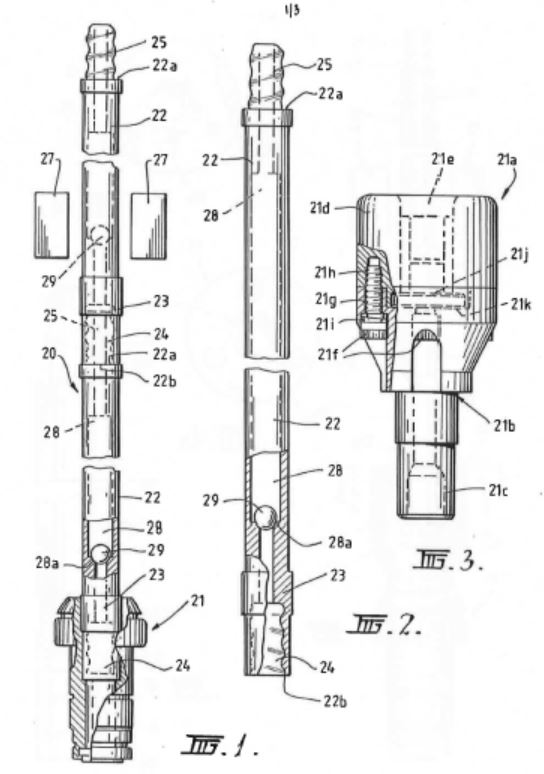

47 Under the heading “Brief Description of the Drawings”, the specification states that two preferred embodiments of the invention will now be described. It is convenient to set out, at this point, Figures 1 to 5 from the specification:

48 It is apparent from the description of the diagrams that the two preferred embodiments are represented, respectively, as follows:

(a) the first preferred embodiment is the subject of Figs 1 and 2; and

(b) the second preferred embodiment is the subject of Figs 3, 4 and 5.

49 However, as Fig 3 sets out an alternative adaptor (referred to as a “direct drive chuck”) to the one used in Figs 4 and 5, there are, in fact, three alternatives described in the diagrams, with the second preferred embodiment always involving the use of an adaptor.

50 According to the specification:

(a) Fig 1 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension drilling system in accordance with a first preferred embodiment of the invention;

(b) Fig 2 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension rod as used in the system of Fig 1;

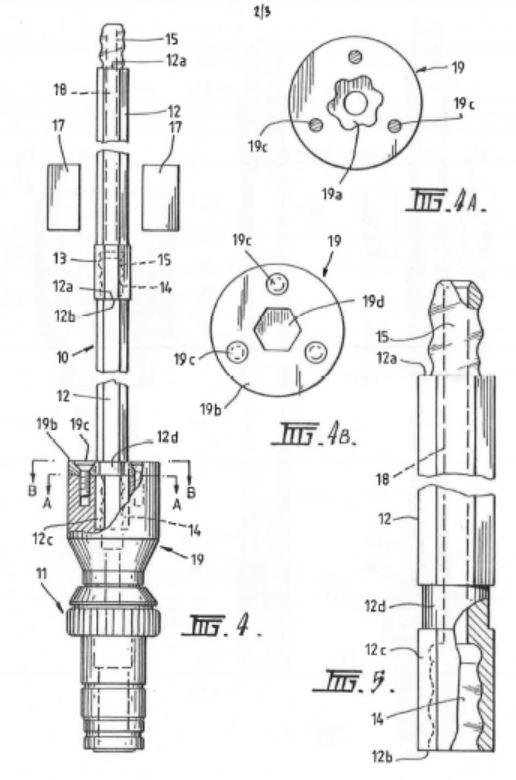

(c) Fig 3 is a longitudinal side elevational view, partly sectioned, of an alternative direct drive chuck for use in the extension drilling system of Figs 4-5;

(d) Fig 4 is a longitudinal side elevational view, partly sectioned, of an extension drilling system in accordance with a second preferred embodiment of the invention;

(e) Fig 4A is a cross-sectional view taken along the line A-A of Fig 4;

(f) Fig 4B is a cross-sectional view taken along the line B-B of Fig 4; and

(g) Fig 5 is a longitudinal side elevational view of an extension drill rod as used in the system of Fig 4.

51 Thus the extension drilling systems as a whole are depicted in Figs 1 and 4 respectively. The rods to be used in those systems are depicted in Figs 2 and 5 respectively.

52 Greater detail of the adaptor in use in Fig 4 is given in Figs 4A and 4B, the effect of which is to illustrate a locking mechanism similar to that described above.

53 The next section of the specification is headed “Best Modes for Carrying out the Invention”. With reference to Figs 1 and 2, the specification states that the chuck used in that extension drilling system may be “a TL2 drive chuck as manufactured by McSweeney’s, Inc of the USA”. That chuck, which will be referred to as the “McSweeney TL2 chuck”, is the same as the 25 mm square locking chuck (depicted above at [24]), save that the dimensions of the square opening are 28 mm rather than 25 mm. The specification continues that the chuck, which may be the McSweeney TL2 chuck, “directly rotatably drives” a string of extension rods. The means of connection between various rods is then described, but is uncontroversial. An axial passage is provided through the respective extension rods, it being stepped to provide a transition between larger and smaller diameter portions of the passage in order to provide valve seats for the ball-valve mechanisms (as discussed above at [37]).

54 The specification continues:

As illustrated in Figure 2, the external or outside surface of the female socket 24 is engaged by the drive chuck 21 for driving the string of extension rods 22. The surface of the female socket 24 that the drive chuck 21 engages therefore has a profile suitable for that engagement. Figure 2 shows that the surface which is engaged by the drive chuck 21 includes a portion of greater diameter at the position to which the lead line for the reference numeral 23 extends. Extending from the engagement position of the drive chuck 21 to the male member 25, the surface of the extension rod 22 is of a substantially uniform profile and of reduced diameter compared to the diameter at the engagement position of the drive chuck 21. Thus there is a difference in surface profile between the engagement position of the drive chuck 21 at the female socket 24 and the section of the extension rod between the female socket 24 and the male member 25.

(Emphasis added.)

55 It should be noted that all but the first two sentences in this passage were added by amendment on 30 August 2006. It should also be noted that, if the McSweeney TL2 chuck were to be used in the first preferred embodiment of the invention (described above by reference to Figs 1 and 2), since it is a requirement that “the external surface shape of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck” (see [43] above), then at “the position to which the lead line for the reference numeral 23 extends” (see [54] above), the rod would have to be of a square profile. In essence, without the use of an adaptor (which is not a feature of the first preferred embodiment), a square drive drill rod is needed to fit a square locking chuck.

56 What the specification says about Fig 3 is as follows:

Figure 3 of the drawings shows a modified (alternative) direct drive chuck for use in the extension drilling systems of Figures 4 to 5, and is in fact the drive chuck preferred, and which is a modular assembly 21a comprising a male drive member 21b having a drive shaft 21c and coupled to a female drive member 21d with a socket 21e. The drive members are coupled by bolts 21f through holes 21g in the male drive member 21b and into threaded blind holes 21h in the female drive member 21d with interposed spring washers 21i. The male and female members may also be “dogged” together, that is interlocked. The socket 21e receives a sealing member 21j which may be formed from polyurethane, moulded around a stainless steel washer body, and which seats on a step 21k in the end of the male drive member 21b. The modular drive chuck of this embodiment, in being formed in two separable parts, allows the drive members 21b and 21d to be interchangeable for different drive configurations, and also allows for the sealing member 21j to be replaced when worn.

(Emphasis added.)

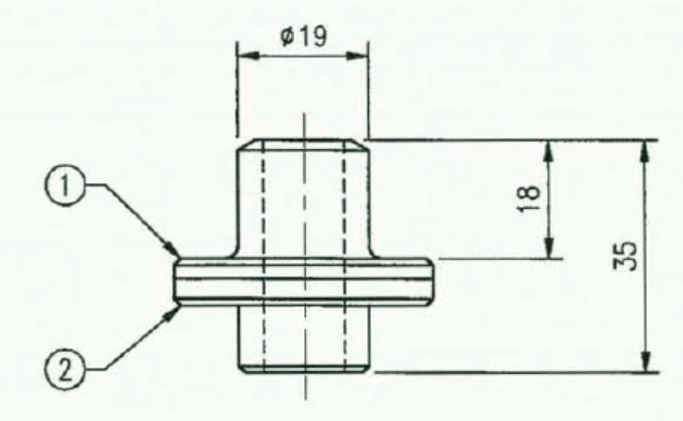

57 With respect to Fig 4, it is made clear that the chuck itself, which again may be the McSweeney TL2 chuck, is the lowermost portion on the diagram, marked 11. The adaptor (which has been inserted into the chuck) is the portion marked 19. After referring to the rods and the connections between them, the specification continues:

With reference to Figures 4 and 5 of the drawings, the internal detail of the chuck adaptor 19 is according to that shown in Figure 4A of the drawings and is shaped as a hexagon 19a offset by 20° of rotation. A chuck adaptor cover 19b as shown in Figure 4B is bolted to the remainder of the chuck adaptor by bolts 19c. The cover provides a hole 19d for the extension rod to fit into and which has a normal hexagonal shape. The end of the extension rod which fits into the chuck adaptor 19, and incorporating the female socket 14 which is not drivingly engaged by the chuck adaptor, has an [sic] hexagonal exterior 12c and above that a round section 12d. When the extension rod end is fitted into the chuck adaptor, the hexagon 12c on the end of the rod is aligned with the hexagonal hole 19d through the chuck adaptor cover 19b. The rod is then slid down into the chuck adaptor to its full extent, and as positive rotation is commenced the chuck adaptor rotates 20° in relation to the rod and the drive flats of the hexagonal 19a in the chuck adaptor engage against the hexagonal shaped end 12c on the rod to thus rotatably drive the rod. The round section 12d on the rod is provided so that, as the rod is rotated through 20°, the hexagon through the chuck adaptor cover 19b does not bind on the rod. As long as positive rotation is maintained in the chuck adaptor the rod cannot be removed as the two hexagons are misaligned by 20° and the rod needs to be rotated through 20° so that the corners of the hexagon 12c will clear the hexagonal hole 19d through the chuck adaptor cover 19b in order for the rod to be removed. The drive chuck as described above in providing a twist locking action between the chuck and the rod improves the safety of the drilling system because of the locking of the rod in the drive chuck whilst maintaining positive rotation.

(Emphasis added.)

58 The burden of this passage is to explain the means by which a rod with a female threaded lower end may form a locking engagement with the adaptor into which it is placed, but to which it is not threaded. The principle is similar to that employed in the square locking chuck (as described above at [27]), but here the engagement is between the rod and the adaptor, rather than being directly between the rod and the chuck. It is apparent, and is expressly required in this second preferred embodiment, that the lowermost section of the rod be of hexagonal profile (so that it can fit into the aperture of the adaptor) while, immediately above that, there must be a section which is round in profile to accommodate turning the rod through 20 degrees to bring about the intended locking effect.

59 Whether the remainder of the rod (above the rounded section referred to in the paragraph above) is also round, is the concern of the following paragraph in the specification:

In the case of both embodiments of the invention, the extension rods are of hexagonal cross-section, as previously described with reference to the embodiment of Figure 4 to 5, or of round cross-section or of any other suitable cross-sectional shape whereby they can be driven by the chuck adaptor 19 in the case of the embodiment of Figures 4 to 5 or directly by the drive chuck 21 or 21a in the embodiment of Figures 1, 2 and 3. The extension rods may be forged or welded rods which are selectively or fully heat treated.

60 The specification includes the following claims:

1. An extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connected together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at one end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at the other end, whereby the extension rods are connected together by coupling of the male coupling of one extension rod with the female coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between extension rods, a drive chuck of a drilling rig for driving the outside surface of a female coupling of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, in either forward or reverse direction, a set of grippers for preventing rotation of an extension rod being arranged to clamp an extension rod at a location such that only one male/female coupling is located between the drive chuck and the set of grippers and so that with the grippers clamping the extension rod, and with the drive chuck being driven in the reverse direction, the male/female coupling between the grippers and the drive chuck is uncoupled.

2. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 1 wherein the extension rods have axial passages therethrough in communication with each other and through which flushing fluid is delivered to an associated drill bit.

3. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 2, wherein the axial passage through at least one of the drill rods incorporates a non-return valve to shorten the delay time in delivering flushing fluid to the drill bit before recommencement of drilling after a drill rod is added to the drill rod string.

4. An extension drilling system as claimed in any one of the preceding claims, wherein the extension rods are of hexagonal or round cross-section or of any other suitable cross-section whereby they can be driven by the drive chuck either directly or via an adaptor having a socket therein of similar cross-section to the extension rods.

5. An extension drilling system as claimed in claim 4, wherein the co-operation between the drive chuck or the adaptor and the extension rod directly associated therewith is such that limited relative rotational movement therebetween misaligns the respective cross-sections to prevent separation of the extension rod whilst maintaining driving engagement.

6. An extension drilling system substantially as hereinbefore described with reference to figures 1 and 2, or figures 3, and 4 as modified by figure 5, of the accompanying drawings.

7. An extension drilling system for use with a semi-automatic drilling rig, said drilling system including a plurality of extension rods connectable together to constitute a drill rod string and each extension rod having a male right-hand rope threaded coupling at a male end and a female right-hand rope threaded coupling at a female end, whereby the extension rods are connectable together by coupling of the male end coupling of one extension rod with the female end coupling of another extension rod to create a male/female coupling between connected extension rods and wherein the external surface of the female end has a profile for engagement by a drive chuck of a drilling rig to drive the female end of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string, and wherein the external surface of the extension rods between the female end and the male end is of a different and substantially uniform profile.

61 Claim 6 is an ‘omnibus’ claim, which refers to the preferred embodiments described in Figures 1-5, discussed above.

The decision of the primary judge

62 The primary judge considered the issues under the following headings:

(a) novelty;

(b) inventive step;

(c) best method known to Sandvik;

(d) utility;

(e) infringement;

(f) joint liability with primary infringers; and

(g) misleading or deceptive conduct.

63 For present purposes, it is sufficient to refer only to the first four of these sections of the Reasons.

Novelty

64 The primary judge considered the issue of novelty at [47]-[161] of the Reasons. Quarry Mining contended below that the invention the subject of the Patent, so far as claimed in claims 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7, was not novel in June 1997. The question which arose under s 7(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) as applicable at the relevant time (Patents Act) was whether the invention was not novel in the light of two kinds of prior art information relied on by Quarry Mining, being:

(a) the public use of an extension drilling system by Colrok Mining Pty Ltd (Colrok) at collieries in New South Wales, including Ellalong and Macquarie, between 1989 and 1994; and

(b) the public use of an extension drilling system at the West Wallsend, Gretley and Wyee Mines by an entity described in the evidence (and in Quarry Mining’s Particulars of Invalidity) only as “Wilson Mining”.

65 In relation to the first kind of prior art, the primary judge considered the evidence in detail including, in particular, the evidence of Darrell Geatches, Quarry Mining’s principal witness called to provide evidence of the extension drilling system used by Colrok. Mr Geatches referred in his evidence to Roy Gambly (now deceased) (see [58] of the Reasons). Mr Geatches gave evidence that Mr Gambly made the ends for certain new drill rods, being an end with a male right-hand rope thread, and an end having a hexagonal outer profile (32 mm across the flats) with an internal female right-hand rope thread. The primary judge summarised the effect of Mr Geatches’ evidence at [59] as follows:

In operation, the female end of a drill rod was inserted (and here I quote from Mr Geatches’ affidavit) “directly into the drive chuck (which was in effect an adaptor) on the drill rig, which had a hexagonal shaped socket.” The chuck drove the rod by engaging with the hexagonal external surface of the female end of the drill rod. The new drill rods proved very successful. Being easy to extend and to uncouple, their use led to an increase in the speed at which rods could be inserted into and removed from a drill string. In part, this was because there was no longer the need to uncouple (ie by unscrewing) the lowermost rod from a male shank adapter when building or dissembling the drill string. These were the rods that Mr Geatches and his colleagues described as “speed rods”. In Mr Geatches’ recollection, it was in the mid to late 1980s that Colrok reached this point.

66 The primary judge stated (at [61]) that Colrok used these rods in the late 1980s at Ellalong Colliery to drill the holes required to install cable bolts for the establishment of secondary roof support in restitution work after a roof collapse on a conveyor road. The primary judge then quoted Mr Geatches’ description of the process in which the rods were used (at [61]). That description included the following steps (in which the rods were referred to as “Geatches Rods”):

Step 9 Once the last (bottom) Geatches Rod had been connected to the drill string and drilled into the strata to a point near to its female end, the drive motor and drive chuck were dropped back down the drill mast to a position above ground level. This lowered the drill string such that the last (bottom) and second last (i.e., second from the bottom) Geatches Rods were removed from the bore hole.

Step 10 The pair of clamps was engaged to grip the second last (i.e., second from the bottom) Geatches Rod at its hexagonally shaped female end.

Step 11 The drive motor was driven in reverse (left hand rotation). This broke the threaded connection between the male threaded end of the bottom Geatches Rod, and the female threaded end of the second bottom Geatches Rod. The drill motor and drive chuck were then lowered further down the drill mast and the motor disengaged from the hex drive end.

67 The primary judge referred, at [64], to Sandvik’s contention that Mr Geatches’ evidence, to the extent that it related to the development and use of the rods described above, should not be accepted at all. His Honour stated that Sandvik had pointed out, correctly, that this evidence was not supported by the production of: any of the chucks or drill rods used; any contemporaneous drawings or sketches of the rods; the specifications provided to Mr Gambly; any photographs of the components that Mr Gambly supplied to Colrok; any drawings, sketches or photographs of the rods that Colrok assembled from those components; or any drawings, sketches or photographs of the components actually used at Ellalong. The primary judge considered Sandvik’s submissions about what it described as the five “errors” in Mr Geatches’ evidence but did not accept that Mr Geatches’ evidence should be regarded as likely to be the less reliable on account of those matters (at [75]). The primary judge considered other evidence relied on by Quarry Mining. One factual issue concerned whether, in the system of extension drilling used by Colrok at Ellalong Colliery, the connections between the drilling rods were right-hand rope-threaded connections. The primary judge concluded that they were (at [124]).

68 Ultimately, the primary judge accepted Mr Geatches’ evidence about the extension drilling system which Colrok used at Ellalong Colliery (at [125]). His Honour also concluded that the same system was used at Macquarie Colliery (at [129]). Accordingly, so far as claimed in claims 1, 2, 4 and 7, the invention was anticipated by the system used by Colrok at the Ellalong and Macquarie Collieries (at [131]).

69 In relation to claim 6, the primary judge concluded that the Colrok drilling system did not anticipate the second embodiment of the invention (which included two alternatives – with and without the alternative adaptor shown in Fig 3) described in the Figures (at [133]). This aspect of the primary judge’s conclusions does not form part of the appeal and can be put to one side. However, in relation to the first embodiment described in the Figures, the primary judge held that, on the basis of the factual findings he had made, the Colrok drilling system did anticipate this embodiment (at [134]).

70 In relation to the second kind of prior art information referred to in [64] above, the primary judge concluded (at [160]) that the system used by Wilson Mining did not anticipate the invention so far as claimed in claim 1 because it did not incorporate a chuck for driving the outside surface of the female coupling on a drill rod in the reverse direction. The primary judge applied the same approach to the other claims (at [161]). The primary judge’s conclusion in relation to the second kind of prior art does not form part of the appeal and can be put to one side.

Inventive step

71 The primary judge considered the issue of lack of inventive step at [162]-[211] of the Reasons. Quarry Mining contended below that the invention the subject of the Patent, so far as claimed in claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, did not involve an inventive step. By s 7(2) of the Patents Act, Quarry Mining needed to establish that the invention, so far as claimed in those claims, would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in June 1997.

72 The primary judge concluded that the invention, so far as claimed in claim 1, would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed before the priority date. The primary judge’s conclusion in this regard was set out as follows (at [200]):

Everything considered, I have come to the conclusion that the invention, so far as claimed in Claim 1, would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed before the priority date. Fundamental to this conclusion is the very limited respect in which Claim 1 took a step which went beyond what was already commonly and generally used in the industry, and self-evidently so from the terms of the specification itself … To take that step would, in my view, have been obvious to the skilled addressee. Faced with the problems of the presence of two threaded connections between the chuck and the grippers and of the space occupied by the adaptor, the skilled addressee would have recommended the employment of a system in which the chuck drove the outside of the lowermost rod. He or she may not have come to that solution instantly, but, examining the range of possibilities and employing no more than his or her normal uninventive skills and experience, he or she would, in my view, have readily suggested doing exactly what Claim 1 requires, namely, making use of “a drive chuck … for driving the outside surface of a female coupling of an extension rod at one end of the drill rod string”.

73 The primary judge came to the same conclusion in respect of claims 2, 3 and 4 (at [203]-[205]). With respect to claim 6, the primary judge came to the same conclusion in relation to the first preferred embodiment (ie, Figs 1 and 2) (at [206]), but was not persuaded that the second preferred embodiment (ie, Figs 3, 4 and 5) was obvious (at [206]). The primary judge considered that the invention, so far as claimed in claim 7, was obvious for the same reasons as claim 1 (at [211]).

Best method known to Sandvik

74 The primary judge considered the best method issue at [212]-[232] of the Reasons. By s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act, a complete specification was required to “describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention”. Quarry Mining contended below that, when Sandvik filed the complete specification for the invention the subject of the Patent on 29 May 1998, it did not disclose what was then known to it as the best method of performing the invention.

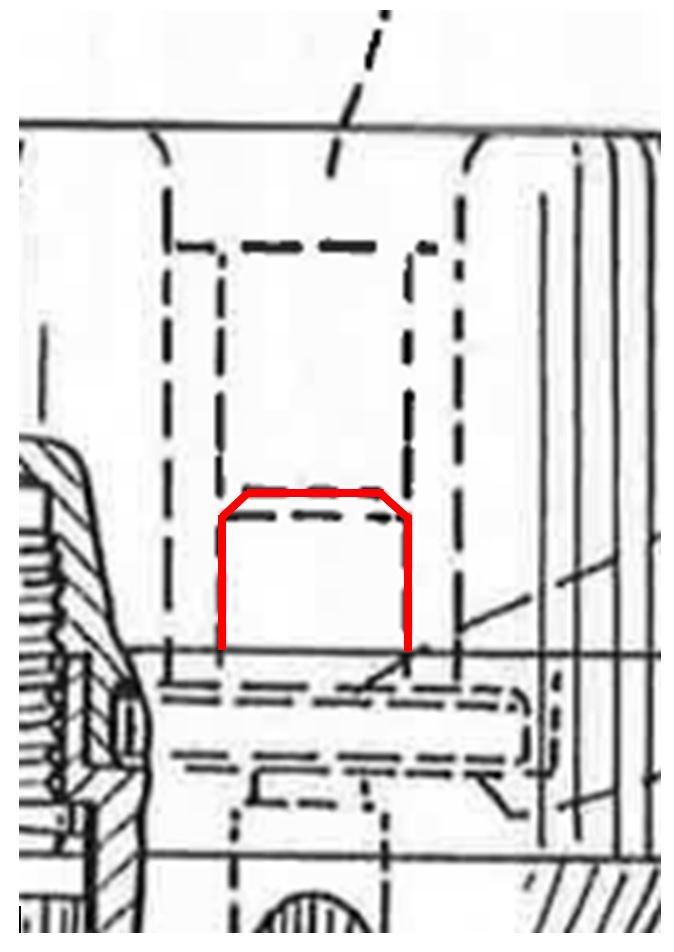

75 One aspect of this issue was whether Fig 3 disclosed only a sealing member with a flat washer-type seal, such as might be made from coating a stainless steel washer with polyurethane (as contended by Quarry Mining), or a sealing member that included both a flat part and an upwardly-extending cylindrical part as shown in red in the enlarged diagram below (as contended by Sandvik):

76 The primary judge concluded, at [219], that the specification did not disclose a sealing member which included an upwardly-extended spigot integral with the flat part of the member as follows:

Did the specification describe a method of performing water sealing in the adaptor shown in Fig 3 by means of a sealing member which included an upwardly-extending spigot integral with the flat part of the member? The starting point, of course, is the text of the specification. The sealing member described there is confined to the stainless steel washer body coated in polyurethane. The sealing member is numbered 21j and, while there is some ambiguity about the matter, most obviously this is a reference to the horizontal element. That was Dr Fuller’s understanding. Mr Charlton was able to discern what the inventors were about in this aspect of Fig 3, but his understanding of the subject depended to an important extent on what he regarded as implicit: in a metaphorical as well as a literal sense, he was required to join the dots. In my view, for the inventors to have communicated in this way to the skilled addressee did not amount to a description within the meaning of s 40(2)(a) of the Act: no more so in the case of the best method than it would have been in the case of the invention itself.

77 The primary judge found that the inventors had developed a form of sealing member that incorporated upper, middle and lower sections, depicted as follows (at [222]):

78 The primary judge stated (at [224]): “We are not here dealing with some minor or incidental dimension of what was perceived by the inventors as the best method of performing the invention: as Mr Weaver said, this sealing aspect was ‘a real issue which needed to be overcome’.”

79 The primary judge next considered an argument put by Sandvik that the detailed characteristics of the sealing member did not relate to a method of performing the invention at all. In support of this argument, Sandvik relied on the judgment of the Full Court in Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (2000) 51 IPR 531 (Firebelt) at [51]-[55].

80 The primary judge considered that, while the best way of carrying out the invention need not be claimed (but must be described), in the present case Sandvik had in fact claimed what was, ostensibly at least, the best way of carrying out the invention, namely the extension drilling system using the device set out in Fig 3 (stated to be the “drive chuck preferred”) (at [227]). In the primary judge’s view, the difficulty faced by Sandvik was that the description in Fig 3 was not the best method known to it. His Honour stated (at [228]): “When the complete specification was filed in May 1998, [Sandvik] had developed, to the detailed technical drawing stage, a sealing member that was better than any described in the specification.”

81 Accordingly, the primary judge accepted Quarry Mining’s case that the complete specification for the Patent did not describe the best method known to Sandvik of performing the invention, as required by s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act (at [229]). As Quarry Mining’s best method contention was confined to claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 (ie, it did not extend to claim 5), the primary judge considered that the Patent should not be revoked so far as it relates to claim 5. Otherwise, his Honour found that this aspect of the cross-claim had been made good (at [232]).

Utility

82 The primary judge considered the issue of lack of utility at [233]-[243] of the Reasons. Quarry Mining challenged claims 1-4 on this basis, and put forward two contentions in this regard.

83 Quarry Mining’s first contention related to the absence of a water seal in claims 1-4. The primary judge accepted Sandvik’s proposition that, although not referred to in the claims, the use of a simple seal was within the range of uninventive steps that the skilled addressee might be expected to take if his or her concern was, as presumptively it had to be, to make the invention work (at [235]). Assuming the use of a simple seal, the primary judge held the invention, so far as claimed in claims 1-4, to be useful (at [237]).

84 The second aspect of Quarry Mining’s utility case was as follows. It was said that claims 1-3 permit, and that claim 4 in one of its alternatives requires, the drill rods to be of round cross-section. It was common ground, however, that if the female-threaded end of the lowermost rod was of round cross-section, it could not be driven (save, possibly, by a through-the-spindle chuck, the relevance of which to the present point was eschewed below by Sandvik). Insofar as this issue related to claim 4, it turned on a question of construction. Sandvik contended that, as a matter of construction, claim 4 should not be understood as proposing that the driven end of a rod might be round; the skilled addressee, it was said, would know that that was nonsense. Grammatically, the primary judge stated, Sandvik’s contention had to be rejected. His Honour stated: “That the passage ‘whereby they can be driven by the drive chuck’ conveys the idea that, by reason of being of round cross-section, the rods can be driven by the chuck is, in my view, beyond argument” (at [239]). After referring to disagreement between the experts, his Honour stated that he had reached the view that Sandvik’s contention did not involve construction at all; rather, it involved the invocation of the closest available alternative reading of the words of the claim that would save it from inutility. His Honour held that there was no support in the terms of the claim for such a construction (at [241]). It followed that the invention, so far as claimed in claim 4, would not be useful (at [242]).

85 However, the primary judge did not reach the same conclusion in relation to claims 1-3 (at [243]). To the skilled addressee, the primary judge said, the unadorned expression “for driving the outside surface of a female coupling of an extension rod” in claim 1 would imply a flat-sided profile at the driven end. Claims 1-3 did not, in the primary judge’s view, suffer from the same weakness as claim 4.

The appeal

86 The grounds set out in the amended notice of appeal (apart from ground 8, which was abandoned, and the ground relating to costs) are as follows:

Novelty

1. The primary judge erred in finding that claims 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 of Australian Patent No 744870 (the Patent) lacked novelty by reason of the public use before the priority date of the Colrok system at Ellalong Colliery and Macquarie Colliery.

2. The primary judge’s finding that the Colrok system used at Ellalong Colliery and Macquarie Colliery (the Colrok Use) anticipated all the features of the first embodiment in claim 6 (Figs 1 and 2) was contrary to the evidence and against the weight of the evidence.

3. The primary judge should have found that the Colrok Use did not disclose the use of the ball valve mechanism 29 as described and depicted in the first embodiment of claim 6.

4. The primary judge’s finding that the Colrok Use included male/female right-hand rope threaded drill rods as claimed in claims 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 of the Patent was contrary to the evidence and against the weight of the evidence.

5. The primary judge erred in failing to find and should have found on the evidence before him that the Colrok Use did not include male/female right-hand rope threaded drill rods as claimed in claims 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 of the Patent.

Inventive step

6. The primary judge erred in finding at [200] - [206] and [211] that claims 1, 2, 3, 4, the first embodiment of claim 6 and claim 7 of the Patent were obvious and lacked an inventive step in light of the common general knowledge.

7. The primary judge erred in finding at [200] that the person skilled in the art at the priority date would have recommended an extension drilling system in which the drive chuck drove the outside surface of the female end of the lowermost drill rod in a drill string.

…

9. The primary judge erred in his consideration of inventive step in giving no, or no sufficient, weight to the evidence that:

(a) Dr Fuller (the Respondent’s expert witness) had expertise in the design and installation of cable bolts, but did not have expertise in the use or design of extension drilling systems. In particular:

(i) Dr Fuller had not been personally involved in designing either single pass or extension rods, either at the priority date or since;

(ii) Dr Fuller had not been personally involved in designing adaptors for use with a drill rig chuck;

(iii) Dr Fuller had not been personally involved in designing drilling rigs for the purpose of drilling using either single pass drill rods or extension drill rods;

(iv) Dr Fuller had not operated a drilling rig in the course of either single pass or extension drilling;

(v) Dr Fuller had no personal experience in the design or testing of water seals for use in single pass or extension drilling; and

(b) Dr Fuller was unaware of significant matters which formed part of common general knowledge in Australia at the priority date including:

(i) Dr Fuller was not aware of the two most common extension rod types – round rods in which the profile of the female coupling was also round and hexagonal rods which had a round female coupling;

(ii) Dr Fuller was not aware that, in the years since he prepared a report in 1994 (around 4 years before the priority date), the industry had ceased using male-male rods with female couplings and instead used male-female rods;

(iii) Dr Fuller did not know that the standard chuck used in single pass and extension drilling at the priority date was the 25mm square locking chuck (which he had not seen before trial);

(iv) Dr Fuller was unaware of the health and safety issues caused by “non-locking chucks” before the priority date;

(c) the “typical” components of the system from which Dr Fuller developed his proposed solution did not exist or were not in use in extension drilling systems;

(d) the solution proposed by Dr Fuller would require “an industry wide change” and involved the “tail wagging the dog”; and

(e) those who were actually involved in developing extension drilling and cable bolting machines at or shortly before the priority date did not perceive the problem addressed in the Patent as a problem which required to be addressed nor did they develop the solution claimed in the Patent.

(f) the commercial embodiment of the claimed invention reduced drill withdrawal times by 40% and was taken up rapidly by the industry following its introduction into the market.

10. The primary judge erred in failing to find and should have found on the evidence before him that claims 1, 2, 3, 4, the first embodiment of claim 6 and claim 7 of the Patent were not obvious in light of the common general knowledge.

Best method

11. The primary judge erred in finding at [231]-[232] that claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 should be revoked as the Applicant failed to describe the best method known to it of performing the invention.

12. The primary judge erred in finding at [219]-[224] that the sealing member depicted at [222] was part of the invention.

Utility

13. The primary judge erred in finding at [239]-[242] that the invention so far as claimed in claim 4 was not useful.

14. The primary judge erred in finding that claim 4 included within its scope drill rods the female ends of which were round in cross-section.

15. The primary judge erred in failing to find and should have found on the evidence before him that:

(a) the words “are of hexagonal or round cross-section or of any other suitable cross-section” in claim 4 refer to the cross-section of the body of the drill rod, not the cross-section of the female end of the rod which must be configured to be capable of being driven on the outside by the drive chuck or chuck adaptor; and

(b) the invention so far as claimed in claim 4 was useful.

87 Quarry Mining did not cross-appeal from any part of the judgment. It filed a notice of contention by which it contended that the judgment of the primary judge should be affirmed on an additional ground to those relied on by the Court. The additional ground was that the invention, so far as claimed in each of claims 1-4, is not useful as required by s 18(1)(c) of the Patents Act, because it includes embodiments which do not work. In the notice of contention, Quarry Mining advanced two propositions by way of particulars. However, it indicated at the appeal hearing that it did not press the second of these contentions. The first contention set out in the particulars was as follows. Quarry Mining contended that: the primary judge correctly held that the invention as claimed in claim 4 lacked utility because it used extension rods with a round cross-section at the female end; and having so held, his Honour ought to have further held that the invention claimed in claims 1-3 lacked utility, because those claims too encompassed within their scope extension rods with a round cross-section at the female end.

Failure to describe best method

88 It is convenient to deal first with the issue raised by grounds 11 and 12 of the amended notice of appeal. Sandvik challenges the primary judge’s conclusion that the complete specification for the Patent did not describe the best method known to Sandvik of performing the invention as required by s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act. On this basis, the primary judge ordered that, so far as it relates to claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, the Patent should be revoked.

89 We note at the outset the confined scope of Sandvik’s appeal in relation to the best method issue. In particular:

(a) Sandvik does not challenge the primary judge’s conclusion that the specification does not describe a sealing member which includes an upwardly-extending spigot (Reasons, [219]); and

(b) Sandvik does not challenge the primary judge’s conclusion that, at the time when the specification was filed, Sandvik had developed a better form of sealing member, namely a sealing member with an upper section and a lower section (Reasons, [220]-[222]).

Sandvik’s submissions

90 Sandvik’s contention on appeal (which reflects one of its contentions before the primary judge) is, in substance, that the detailed characteristics of the sealing member did not relate to a method of performing the invention, and therefore were not required by s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act to be disclosed in the specification.

91 Sandvik’s written submissions on this part of the appeal can be summarised as follows:

(a) Whether the complete specification meets the best method requirement of s 40(2)(a) requires an identification of what constitutes the invention: Firebelt at [53]. (Although in its written submissions Sandvik submitted that identification of the invention “must be determined from the claims”, in oral submissions senior counsel for Sandvik accepted that the nature of the invention is as described in the whole of the specification: see Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61 (Servier) at [124]).

(b) In Firebelt, claim 1 expressly included as a feature a lid opening device (see Firebelt at [18]). The body of the specification did not disclose the detail of Firebelt’s preferred lid opening mechanism. In Firebelt at [50], the Full Court approved the following statement in Blanco White TA, Patents for Inventions and the Protection of Industrial Designs (4th ed, Stevens & Sons, 1974) at [4-516]:

There would seem to be no obligation under this provision to include information not strictly relating to “the invention,” however necessary to anyone needing to work the invention.

(c) In Firebelt, the Full Court rejected the best method attack because (at [53]):

The invention here claimed is not a particular type of lid opening device operating at any particular time. It is only if it were such a claim that there might be a failure such as the primary judge found.

(d) The “lid opening device” in Firebelt was a feature of the claim. It appears also to have been the subject of a separate patent application: Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (1998) 43 IPR 83 (Firebelt (first instance)) at 90. The evidence was that the claimed invention would not work without a lid opening device: the lid opening device was “an essential part of the claimed invention”: Firebelt (first instance) at 89. The lid opening device was disclosed only in the most general terms which failed to disclose important details: Firebelt (first instance) at 89-90. As noted above, the Full Court overturned the primary judge’s finding that the best method had not been disclosed, on the basis that the invention was not concerned with any particular lid opening device operating at any particular time. Firebelt is on all fours with the present case.

(e) In this case, the invention is directed to the configuration of extension drilling rods such that they are capable of use with a drive chuck or chuck adaptor which drives the external surface of the female coupling. The water seal is no part of the invention claimed (see, eg, Reasons at [188]).

(f) Servier approved and applied Firebelt: see Servier at [124]. Servier is, however, a very different situation to the present. The invention claimed was perindopril arginine. The specification claimed it had particular advantages of long-term stability: Servier at [7]-[8]. Those stability features depended on the particular method of production which was not disclosed by the term “a classical method of salification”: Servier at [32], [42]-[44], [137], [141]. Hence, the best method known to Servier was not disclosed.

92 In oral submissions, senior counsel for Sandvik emphasised that details of the sealing member did not relate to the promised advantages of the invention. He submitted that the seal, or sealing member, was not a feature of any claim except the omnibus claim (claim 6). The correct approach, he submitted, was to look at the promise of the invention; that is, the way in which the invention as claimed solves the problem for which it was designed. In this case, it was submitted, the solution was to configure the external surface of the female end of each extension rod so that it could be driven by the drive chuck or adaptor; it was not directed to any particular form of water seal.

Applicable principles

93 Section 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act provided that the complete specification must “describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention”.

94 In the context of s 40(2)(a), the “invention” is the embodiment which is described and around which the claims are drawn (cf the invention so far as claimed in any claim): see Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [21] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

95 The circumstance that something is a requirement for the best method of performing an invention does not make it necessarily a requirement for all claims: see Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (2004) 217 CLR 274 at [69] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ.

96 The principles applicable to the best method requirement in s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act were recently considered by the Full Court of this Court (Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ) in Servier at [59]-[108], [112]-[115], [123]-[135]. Although those paragraphs were in part directed to issues that are not presently relevant, the judgment contains a useful survey and discussion of the principal cases relating to the best method requirement. The Full Court in Servier made the following preliminary points concerning the construction of s 40(2)(a) (at [59]):

First, it must be assumed that all of the words of the section are given meaning. Secondly, fulfilment of the requirements must take into account the invention being described and claimed. That does not lend itself to the apparently easy, but superficial, distinction advanced by Servier, whereby inventions are divided into the categories of product and process. Thirdly, perhaps because the requirement involves a question of fact, being the knowledge of the patent applicant, there are not many cases that have centred on the principles of this aspect of the test compared to those that have considered the requirement of what is commonly called sufficiency, such as Kimberly-Clark. Accordingly, fourthly, in applying principles from decided cases on s 40(2)(a) and its equivalents, it is necessary to understand the issues there discussed and whether or not the reasons extended to a consideration of a statutory provision referring to the best method known to the applicant. Fifthly, there are a number of cases in the United Kingdom where this question and the principles behind the application of the best method requirement have been discussed. Clearly, they are not binding and are based on different statutory provisions. However, much of Australian patent jurisprudence on this and other patent issues was derived from British jurisprudence.

97 At [64], the Full Court explained the proposition underlying the best method requirement in s 40(2)(a) as follows:

The proposition underlying a separate and additional obligation on the part of the inventor filing a complete specification is that where an inventor in fact knows of a method at the time of filing the complete patent application, which has taken the methodology to a more satisfactory stage or provides more certainty so that the public may more quickly and easily utilise the invention for which a monopoly is granted, the inventor is under an obligation to disclose that method.

98 The Full Court, at [67], explained that many of the authorities dealing with s 40(2)(a) and its predecessors, when properly understood, were considering the obligation to describe the invention fully (ie, the sufficiency requirement); rarely were these cases specifically directed to the question of an obligation to provide the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention. The Full Court noted that, as Mr Blanco White QC has pointed out, the best method requirement is not commonly advanced as a ground for revocation: Blanco White TA, Patents for Inventions and the Protection of Industrial Designs (5th ed, Stevens & Sons, 1983) (Blanco White (5th ed)) at [4-514].

99 At [72], the Full Court said that the link between the extent of the obligations of disclosure and the nature of the invention was made early. The Full Court referred, by way of example, to Edison and Swan Electric Light Co v Holland (1889) 6 RPC 243 at 279. In that case, the English Court of Appeal said that the patentee must state “in what manner the patented invention is to be performed” so that others know how practically to avail themselves of the invention when the patent is expired: “how they are to do what is necessary to carry out the new invention”, that is, how the invention is to be performed.