FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Callychurn v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2017] FCAFC 137

ORDERS

First Appellant UNIQUE MORTGAGE SERVICES PTY LTD Second Appellant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The matter be remitted to the Tribunal for hearing according to law.

3. The respondent pay the appellants’ costs of the appeal.

4. There be no order for costs of the proceeding before the primary judge.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 This is an appeal from the decision of the primary judge, dismissing an appeal from a decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (the Tribunal), which banned the first appellant, Meenakshi Callychurn (Ms Callychurn), from providing or engaging in credit activities and cancelled the credit licence of the second appellant (UMS). The Tribunal’s order affirmed earlier decisions of a delegate of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), save that the Tribunal reduced the period of Ms Callychurn’s ban from five to four years: Callychurn and Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2016] AATA 114 (the Tribunal’s decision).

the facts

2 Commencing in 2011, UMS carried on business as a finance and mortgage broker and intermediary between credit providers or lessors and consumers, dealing with home, vehicle and other personal loans, car and consumer leases and credit cards. It did so pursuant to an Australian credit licence granted to it pursuant to the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (the Credit Act) on or around 24 December 2010. The original sole director of UMS was Ms Callychurn’s then (domestic) partner, Rudy Frugtniet (Mr Frugtniet).

3 Mr Frugtniet ceased to be a director of UMS in October 2011, after the Victorian Civil and Administrative Appeals Tribunal (VCAT), on 8 April 2011, disqualified him, for the purposes of the relevant provisions of the Legal Profession Act 2004 (Vic) (Legal Profession Act), from practising as a lay associate of a legal practice in Victoria for three years (the VCAT order): Law Institute of Victoria Limited v Frugtniet (Legal Practice) [2011] VCAT 596. The VCAT order was made because Mr Frugtniet had told a barrister and a magistrate at a hearing in the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria that he was a lawyer, when he was not. Mr Frugtniet unsuccessfully appealed against his disqualification to the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria. The detail of the circumstances that led to his disqualification is set out in the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Frugtniet v Law Institute of Victoria Ltd [2012] VSCA 178.

4 Ms Callychurn was the sole director and shareholder of UMS from October 2011 until April 2015.

5 As the holder of an Australian credit licence, UMS was obliged to lodge an annual compliance certificate with ASIC in accordance with s 53 of the Credit Act. Section 53 relevantly provides as follows:

Obligation to lodge annual compliance certificate

Requirement to lodge annual compliance certificate

(1) A licensee must, no later than 45 days after the licensee’s licensing anniversary in each year, lodge a compliance certificate with ASIC in accordance with this section. ASIC may extend the day by giving a written notice to the licensee.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

Compliance certificate must be in approved form

(2) The compliance certificate must be in the approved form.

Who must sign compliance certificate

(3) The compliance certificate must be signed by:

(a) if the licensee is a single natural person – the licensee; or

(b) if the licensee is a body corporate – a person of a kind prescribed by the regulations; or

(c) if the licensee is a partnership or the trustees of a trust – a partner or trustee who performs duties in relation to credit activities.

Requirement to ensure compliance certificate is lodged

(4) Each person by whom the compliance certificate may be signed under subsection (3) must ensure that the licensee lodges the compliance certificate with ASIC in accordance with this section.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

Strict liability offence

(5) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person is subject to a requirement under subsection (1) or (4); and

(b) the person engages in conduct; and

(c) the conduct contravenes the requirement.

Criminal penalty: 60 penalty units.

(6) Subsection (5) is an offence of strict liability.

6 Ms Callychurn caused UMS to lodge annual compliance certificates for the 2011 and 2012 years, each with an annual compliance date of 24 December.

7 The annual compliance certificate had to be completed in the approved form and filed with ASIC online (unless ASIC approved another manner for lodgement): see s 216 of the Credit Act. Among other things, the approved form required a licence holder to nominate “a fit and proper person” upon whom the licensee relied “to demonstrate that it is competent to engage in credit activities”. That person was called the “responsible manager”. The approved form also asked a series of questions, which must be answered either “yes” or “no”.

8 For the 2011 annual compliance certificate, Ms Callychurn nominated herself as a “new fit and proper person”. In response to the question “[w]hat industry category(ies) best describes this person’s area of experience?”, she listed business development, credit risk assessment, finance/mortgage broking and lending. The form also listed Mr Frugtniet as a fit and proper person.

9 The form asked, and Ms Callychurn, on behalf of UMS, answered (for both the 2011 and 2012 years) as follows (the three authorisation questions):

Certification for fit and proper people

Licences, Authorisations

Does the licensee certify that it has no reason to believe that any of its fit and proper people have:

- been refused the right or been restricted in the right to carry on any trade, business or profession for which an authorisation (licence, certificate, registration or other authority) is required by law?

Yes

- been subject to disciplinary action in relation to any such authorisation?

Yes

- within Australia or overseas been the subject of any investigations or proceedings that are current or pending and which may result in disciplinary action being taken in relation to any such authorisation?

Yes

…

10 The form also asked, and Ms Callychurn, on behalf of UMS, answered (again, for the 2011 and 2012 years) as follows:

Offences

Does the licensee certify that it has no reason to believe that any of its fit and proper people have within Australia or overseas, been the subject of administrative, civil or criminal proceedings or enforcement action, which were determined adversely to them (including by consenting to an order or direction, or giving an undertaking not to engage in unlawful or improper conduct) in any country?

Yes

11 ASIC did not seek to rely on the answer to that question before the Tribunal, the primary judge or on the hearing of this appeal.

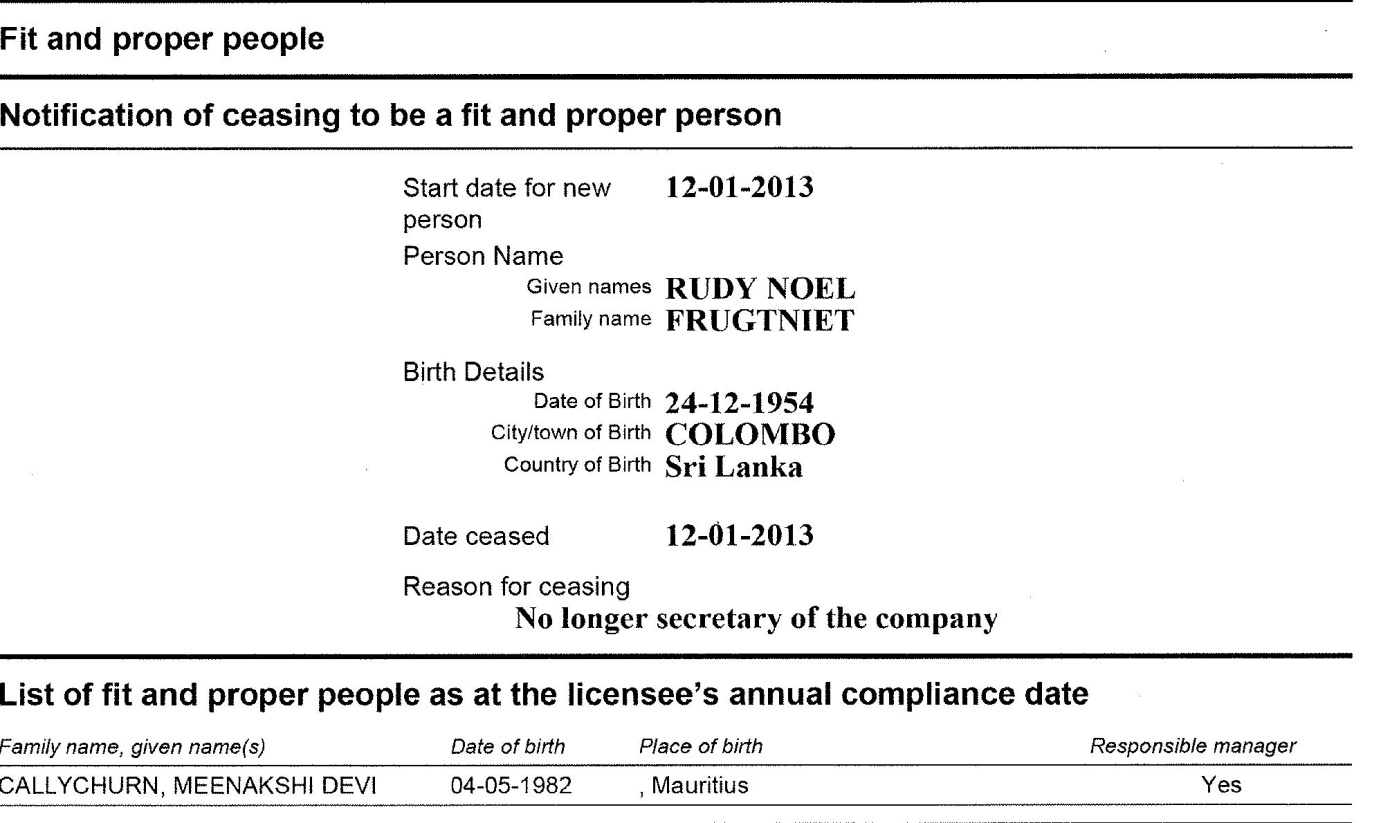

12 Ms Callychurn also completed, on behalf of UMS, the 2012 annual compliance certificate. She did so, online, on 6 February 2013. In its completed form Ms Callychurn had no choice but to submit the relevant part of the form online as follows:

13 For reasons that we will return to below, it is necessary to record ASIC’s concession after the hearing before the Tribunal, and after Ms Callychurn had been cross-examined, about the difficulty that she had in endeavouring to: (a) notify ASIC that Mr Frugtniet had ceased to be a fit and proper person as at 12 January 2013; and (b) at the same time, list him as a person who, as at the annual compliance date, namely 24 December 2012, was a fit and proper person. The concession made by ASIC was as follows:

ASIC accepts that once Ms Callychurn completed the section “Notification of ceasing to be a fit and proper person”, stating that Mr Frugtniet ceased to be a fit and proper person on 12 January 2013, the form automatically operated to remove Mr Frugtniet’s name from the “List of fit and proper people as at the licensee’s annual compliance date” even though the date Ms Callychurn had entered for Mr Frugtniet’s ceasing (12 January 2013) was after the annual compliance date. ASIC accepts that the form did not permit Ms Callychurn manually to add Mr Frugtniet’s name under the heading “List of fit and proper people as at the licensee’s annual compliance date”.

Accordingly, ASIC disclaims any submission that Ms Callychurn herself removed Mr Frugtniet’s name from the “List of fit and proper people as at the licensee’s annual compliance date” in the 2012 Annual Compliance Certificate. To the extent that any cross-examination suggested that Ms Callychurn’s evidence on this point was incorrect, that suggestion should not have been made and is withdrawn.

Other facts upon which the Tribunal relied in imposing the banning order

14 The Tribunal found that, although Ms Callychurn notified ASIC that Mr Frugtniet had ceased to be a fit and proper person as at 12 January 2013 (and was therefore not permitted to engage in credit activities under the terms of UMS’s credit licence), Mr Frugtniet continued to be the only person involved in writing loans for UMS up until late September 2013 and that Ms Callychurn had “improperly and inappropriately delegated her responsibilities as a director of UMS to Mr Frugtniet”.

15 The Tribunal also found that, at various times, long after Ms Callychurn had told ASIC that Mr Frugtniet was no longer a fit and proper person, Mr Frugtniet continued to be the sole signatory to a bank account in the name of UMS into which commission monies were paid and that Mr Frugtniet’s name and contact details appeared on the UMS website as the only “relevant contact” and the “complaint contact” for UMS.

16 In March 2014, ASIC issued two notices under ss 266 and 267 of the Credit Act calling for production of certain documents – one to UMS and the other to a company called Ozwide Financial Services Pty Ltd, of which Ms Callychurn was a director. The Tribunal found that, although the documents sought to be produced were in the possession of the companies, they never were produced.

17 On 28 April 2015, Ms Madeleine Yasmin Seyfarth (Ms Seyfarth) was appointed as an additional director of UMS. Belatedly, it seems, it was revealed that the new director’s former surname was Frugtniet; that she was Mr Frugtniet’s niece; and that, between March 2004 and March 2007, she had been a bankrupt and thus disqualified from managing corporations. Ms Seyfarth resigned in June 2015 and a Mr David Fu was appointed in her place, although there was no evidence adduced by Ms Callychurn before the Tribunal about his “background, position and relationship … to any of the relevant parties”.

Relevant legislation

18 ASIC may make a banning order against a person pursuant to s 80 of the Credit Act. Relevantly, that section provides as follows:

ASIC's power to make a banning order

(1) ASIC may make a banning order against a person:

…

(d) if the person has:

(i) contravened any credit legislation; or

(ii) been involved in a contravention of a provision of any credit legislation by another person; or

(e) if ASIC has reason to believe that the person is likely to:

(i) contravene any credit legislation; or

(ii) be involved in a contravention of a provision of any credit legislation by another person; or

(f) if ASIC has reason to believe that the person is not a fit and proper person to engage in credit activities; or

…

(2) For the purposes of paragraphs (1)(e) and (f), ASIC must (subject to Part VIIC of the Crimes Act 1914) have regard to the following:

(a) if the person is a natural person – the matters set out in paragraphs 37(2)(a) to (f) and subparagraph 37(2)(g)(i) in relation to the person;

…

(c) any criminal conviction of the person, within 10 years before the banning order is proposed to be made;

(d) any other matter ASIC considers relevant;

…

19 Nothing in s 37(2) applied to Ms Callychurn or UMS in the circumstances.

20 Section 225 of the Credit Act creates civil penalties and offences relating to lodging false or misleading documents with ASIC. Relevantly, sub-ss (1), (2) and (5) of s 225 provide as follows:

Offences relating to documents lodged with ASIC etc.

Documents this section applies to

(1) This section applies to the following documents:

(a) any document required under or for the purposes of this Act;

(b) any document lodged with or submitted to ASIC under or for the purposes of this Act.

Requirement where person knows matter is false or misleading

(2) A person must not:

(a) make, or authorise the making of, a statement in the document if the person knows, or is reckless as to whether, the statement:

(i) is false in a material particular or materially misleading; or

(ii) has omitted from it a matter or thing the omission of which renders the document materially misleading; or

(iii) is based on information that is false in a material particular or materially misleading, or has omitted from it a matter or thing the omission of which renders the document materially misleading; or

(b) omit, or authorise the omission of, a matter from the document if the person knows, or is reckless as to whether, without the matter, the document is false in a material particular or materially misleading.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

…

Requirement to take reasonable steps

(5) A person must take reasonable steps to ensure that the person does not:

(a) make, or authorise the making of, a statement in the document that:

(i) is false in a material particular or materially misleading; or

(ii) has omitted from it a matter or thing the omission of which renders the document materially misleading; or

(iii) is based on information that is false in a material particular or materially misleading, or has omitted from it a matter or thing the omission of which renders the document materially misleading; or

(b) omit, or authorise the omission of, a matter from the document, without which the document is false in a material particular or materially misleading.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

…

THe tribunal’s decision

21 Ms Callychurn appeared for herself and UMS before the Tribunal. The Tribunal decided that Ms Callychurn was not a fit and proper person to engage in credit activities, within the meaning of s 80(1)(d), (e) and (f) of the Credit Act, and imposed a four-year ban, in substance, for the following reasons:

(1) Ms Callychurn had contravened the Credit Act by filing a false or misleading annual compliance certificate in each of the 2011 and 2012 years (relying on s 80(1)(d));

(2) Ms Callychurn “had allowed control in almost all material respects to rest with Mr Frugtniet who controlled the receipt and processing of loan applications, the bank account of UMS , the website and complaints against the company”, that in doing so “she was failing in her duties as a director and was in effect largely abdicating responsibility as such a director” and “had shirked her responsibilities and lacked a clear understanding of the role she needed to perform as a fit and proper person and key person of UMS” (relying on s 80(1)(e) and (f));

(3) Ms Callychurn in her capacity as a director had caused UMS and Ozwide Financial Services Pty Ltd not to respond to two notices issued by ASIC requiring production of documents (relying on s 80(1)(e) and (f));

(4) Ms Callychurn had been less than forthcoming about Ms Seyfarth’s close familial relationship with Mr Frugtniet and had not disclosed any details about Mr Fu (relying on s 80(1)(e) and (f)).

22 Having made those findings, the Tribunal concluded:

Taking all that into account the Tribunal concludes that a banning order should be imposed but this should be imposed at the lighter end of the scale – in the circumstances a ban of four years is considered to be the appropriate duration.

(Emphasis added).

23 The Tribunal also found that the cancellation of the Australian credit licence held by UMS followed inevitably because Ms Callychurn was the only director of UMS.

the appeal to the primary judge

24 Ms Callychurn again represented herself and UMS before the primary judge. They argued nine separate grounds. None succeeded and the appeal was dismissed: Callychurn v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2017] FCA 29.

25 Relevantly, his Honour dealt with grounds 2 and 4 at first instance, being the subject matter of the grounds of appeal argued before us, as follows.

26 First, the primary judge dealt with the Tribunal’s findings that Ms Callychurn had failed to disclose in the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates that Mr Frugtniet had been subject to the VCAT order. Ms Callychurn and UMS had argued that the answers to the three authorisation questions were correct because Mr Frugtniet had not, by reason of the VCAT order, been refused or restricted in the right to do anything for which an authorisation was required by law. His Honour found that the Tribunal had not erred in its reasoning that Ms Callychurn should have disclosed the VCAT order because the proceeding before VCAT was “disciplinary action” within the meaning of the second question concerning “any such authorisation”. Moreover, his Honour held that whatever Ms Callychurn’s state of mind on that issue, she had contravened s 225(5) because she had failed to take reasonable steps to ensure that when she made each compliance certificate it did not contain a statement that was false in a material particular. His Honour held that it had been open to the Tribunal to find that, by failing to disclose that Mr Frugtniet was restricted from acting as a lay associate, each certificate was materially misleading. Accordingly, his Honour rejected ground 2 before him.

27 Secondly, the primary judge rejected ground 4 before his Honour, namely that Ms Callychurn had not made a false or misleading statement in the 2012 compliance certificate because the certificate omitted Mr Frugtniet’s name from the list of fit and proper persons. His Honour found that the challenge to the Tribunal’s finding, that this omission entailed that the 2012 compliance certificate included a false or misleading statement, amounted to merits review. His Honour held that the Tribunal’s decision on this issue did not disclose any reviewable error and that its findings were open to it, including its finding that Ms Callychurn had failed to take reasonable steps to ensure that she did not make, or authorise the making of, that false or misleading statement.

This appeal

28 The appellants were represented at the hearing before us by Mr MH O’Bryan QC and Mr JP Wheelahan of counsel, pursuant to the Victorian Bar’s pro bono scheme.

29 Only two grounds were argued, in relation to the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates. The particular questions raised by those grounds turn on the construction of the questions asked, in the cases of the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates, and, in the case of the 2012 compliance certificate, the particular difficulties that Ms Callychurn had in filling in the online form.

30 Counsel for the appellants accepted that if either or both grounds succeeded, the matter should be remitted to the Tribunal to enable reconsideration of the period of the banning order. In circumstances where no challenge is now made to the other bases upon which the Tribunal found that Ms Callychurn was not a fit and proper person to engage in credit activities, and where other grounds may be raised on remittal, counsel’s concession is an appropriate one. There was no issue on this appeal about the Tribunal’s cancellation of the Australian credit licence held by UMS.

31 For the reasons that follow, having had the benefit of helpful submissions from counsel on both sides (unlike the primary judge), we are of the opinion that the Tribunal did err in finding that Ms Callychurn contravened the Credit Act on the grounds contended for by ASIC and adopted by the Tribunal. In our view, none of the answers to the particular questions relied upon by ASIC was false or misleading.

32 Findings that contraventions of the Credit Act occurred are obviously serious findings and there is no doubt that the Tribunal took those findings of contravention into account in fixing the ban period of four years. In those circumstances, for the reasons explained below, we must remit the matter to the Tribunal for determination according to law.

The three authorisation questions in the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates

33 The first question which Ms Callychurn, on behalf of UMS, answered in the affirmative was: “does the licensee certify that it has no reason to believe that any of its fit and proper people have been refused the right or been restricted in the right to carry on any trade, business or profession for which an authorisation (licence, certificate, registration or other authority) is required by law?” (emphasis added).

34 The Tribunal held that in answering “yes” to that question, Ms Callychurn gave a false or misleading answer in contravention of s 225 of the Credit Act because:

[w]hile there was no specific authorisation previously required for him to do so, the effect of the order was to impose a requirement that [Mr Frugtniet] obtain authorisation from the Legal Services Board to carry on a business as a lay associate. In other words he was quite clearly restricted in the right to carry on business for which an authorisation was required by law … Clearly while ordinarily there is no authorisation required to carry on a business as a lay associate, there is such a restriction in circumstances where by order of a Tribunal authorisation is now specifically required from the Legal Services Board ...

In addition Mr Frugtniet was restricted in his right to carry on practice as a lawyer by virtue of the order made by the VCAT on 8 April 2011.

35 The last point made by the Tribunal is clearly incorrect. Mr Frugtniet was not and never had been a lawyer, within the meaning of the Legal Profession Act, having previously been denied admission to practise. Nor, for that reason, was he at any relevant time an Australian legal practitioner, within the meaning of that Act (being, relevantly, a lawyer who holds a current practising certificate).

36 At the time of the VCAT order, the Legal Profession Act defined “lay associate” in these terms, “a lay associate of a law practice is an associate of the practice who is not an Australian legal practitioner”: Legal Profession Act (reprint no. 35, consolidated to 30 March 2011), s 1.2.4(2)(b). That Act was repealed on 1 July 2015 by s 157 of the Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic).

37 Prior to its repeal, s 2.2.6 of the Legal Profession Act relevantly provided:

Order disqualifying persons

(1) The Board may apply to the Tribunal for an order that a person (other than an Australian legal practitioner) is a disqualified person for the purposes of this Division if the person—

(a) has been convicted of a relevant offence; or

(b) in the opinion of the Board has been a party to an act or omission that, if the person had been an Australian legal practitioner, may have resulted in a charge being brought in the Tribunal.

(2) The Tribunal may order that the person is a disqualified person for the purposes of this Division, for a specified period or indefinitely.

…

(Emphasis added.)

38 Section 2.2.7 of the Legal Profession Act relevantly provided:

Prohibition on certain associates

(1) Unless the Board gives its approval, a local legal practitioner, or a law practice in this jurisdiction, must not have a lay associate who the practitioner or practice knows to be—

(a) a disqualified person; or

(b) a person who has been found guilty of a relevant offence.

…

(3) A disqualified person, or a person found guilty of a relevant offence, must not become or seek to become a lay associate of a local legal practitioner or law practice, unless the person first informs the practitioner or practice of the disqualification or finding of guilt.

Penalty: 60 penalty units.

….

39 The Tribunal found that the effect of the VCAT order was that Mr Frugtniet, from the date of the order, was required to obtain authorisation in order to work as a lay associate and that a restriction within the meaning of the first question existed. In our view, the Tribunal erred in so reasoning, because, as counsel for the appellants submitted, Mr Frugtniet had not been refused the right or been restricted in the right to carry on any trade, business or profession for which an authorisation is required by law.

40 That question was directed to a refusal or a restriction of the right to carry on a trade, business or profession for which an authorisation was required. As is clear from the relevant provisions of the Legal Profession Act set out above, no authorisation was required by law in order for a person to be employed as a lay associate in a legal practice in Victoria.

41 It is true that the Legal Services Board could give its approval (which, it may be assumed, could include an authorisation) to a legal practitioner or a law practice to have a lay associate whom the practitioner or practice knows to be a disqualified person (see s 2.2.7(1) above). However, that did not mean that Mr Frugtniet himself had been refused or restricted in a right to do anything for which any authorisation was required by law.

42 It follows that the first question had no application to the VCAT order which disqualified Mr Frugtniet from practising as a lay associate of a legal practice in Victoria for three years for the purposes of the Legal Profession Act.

43 The correctness of Ms Callychurn’s answers to the second and third questions each turned on the same point, since those questions could only be relevant “in relation to any such authorisation”. Because there was no “such authorisation”, the answer “yes” to each of those questions was not inaccurate, and the Tribunal was wrong to find to the contrary.

44 In relation to the third question, the Tribunal also referred to, and relied upon, evidence given by Mr Frugtniet that a consequence of the VCAT order would be to put at risk “authorisations” that he held to carry on business as a conveyancer under the Conveyancers Act 2006 (Vic) and as a migration agent under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). The evidence to which the Tribunal referred was contained in a statement that Mr Frugtniet provided to it, which contained the following assertions:

… disqualification would render my ability to conduct my business as a sole practitioner in Conveyancing, Migration, Tax, and Finance as obsolete.

… any such disqualification would affect my ability to trade and one such example is in the form of notice that a disqualification under the Legal Profession Act 2004, renders a person to be disqualified under the Section 5 of the Conveyancers Act 2006.

…

Similarly, under Section 303 of the Migration Act 1958, the Migration Agents Registration Authority upon being notified of my disqualification may cancel my registration if it is satisfied that I am not a person of integrity or is [sic] otherwise not a fit and proper person to give immigration assistance.

45 The difficulty with the Tribunal taking that evidence into account, as it did, is that ASIC, on the hearing of this appeal, was unable to point to any evidence, including evidence given by Ms Callychurn in cross-examination, that, at the times of completing the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates, she had any knowledge of the matters to which Mr Frugtniet had referred with respect to any “authorisation” he may have held, which permitted him to carry on business as a migration agent or as a conveyancer. In the absence of any such evidence, the Tribunal was, with respect, wrong to use the evidence given by Mr Frugtniet as a foundation for a finding that Ms Callychurn knew that her answer to question three was inaccurate, or false or misleading.

46 For these reasons, the primary judge erred in finding that it had been open to the Tribunal to make its adverse findings on the three authorisation questions. Objectively, Ms Callychurn’s answers to those questions were not false or misleading.

The electronic difficulty in completing the 2012 compliance certificate

47 We have recorded above the difficulty that Ms Callychurn had in completing the 2012 compliance certificate online. Put simply, the difficulty was that it was not possible for her, when completing the online form, once she had filled in the field that Mr Frugtniet had ceased to be a fit and proper person as at 12 January 2013, to include his name in the field immediately below in the “List of fit and proper people as at the licensee’s annual compliance date” (the relevant compliance date being 24 December 2012). That was because the online form automatically deleted his name from that list and would not allow it to be reinserted while his name appeared in the field in the form as that of someone who had ceased to be a fit and proper person.

48 Ms Callychurn was cross-examined before the Tribunal upon the misconception that no such difficulty existed. As we have said above, ASIC belatedly recognised that her explanation was a truthful one. The Tribunal accepted (at [37]) that there was:

… no doubt that the computer problem that gave rise to the outcome that [Mr Frugtniet’s] name was automatically removed from the list of fit and proper people as at the [licensee’s] annual compliance date simply because he ceased to be a fit and proper person at some stage after the annual compliance date, was not a circumstance that was created by Ms Callychurn.

49 Notwithstanding that finding, the Tribunal found (at [39]) that Ms Callychurn should have adopted what it called “the proper course”, namely that she should have contacted ASIC “to seek clarification as to how best to complete the form so as to accurately reflect the true position”. There are two difficulties with that finding. First, there was no evidence before the Tribunal that “contacting ASIC” would have enabled Ms Callychurn in some fashion or another to have completed the compliance certificate differently. Secondly, as completed, the disputed part of the 2012 compliance certificate (set out at [12] above), on its face, must be read, as a matter of ordinary language, as asserting that Mr Frugtniet was a fit and proper person, and company secretary, during the 2012 year and had only ceased to be so, on 12 January 2013, after that year had concluded.

50 In those circumstances, the Tribunal took into account an irrelevant consideration in arriving at the conclusion that Ms Callychurn contravened the Credit Act in the manner in which she answered the questions identifying who was, and who had ceased to be, a fit and proper person in the 2012 annual compliance certificate.

51 Accordingly, we are of opinion that the primary judge erred in finding that Ms Callychurn was seeking to engage in merits review of the Tribunal’s findings on this issue and that those findings were open to it.

52 The question of whether a person makes a statement that he or she knows to be false in a material particular requires the tribunal of fact to read the document as a whole and ascertain whether the impugned statement, even if literally true, actually conveyed, and was intended to convey, a falsehood: R v Kylsant [1932] 1 KB 442 at 446-449 per Avory, Branson and Humphreys JJ; John McGrath Motors (Canberra) Pty Ltd v Applebee (1964) 110 CLR 656 at 659-660 per Kitto, Taylor and Owen JJ; Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 563 at 577 per Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and McHugh JJ.

53 Here, Ms Callychurn’s evidence, that she had tried to list Mr Frugtniet’s name in the list of fit and proper persons, but that ASIC’s online form did not permit her to do so once she had entered into it the fact that, after 24 December 2012, he had ceased to be a fit and proper person, demonstrated that she did not intend to convey a falsehood. That was for two reasons. First, she had correctly recorded him as having ceased to be a fit and proper person after the end of the relevant 2012 year for which she made the compliance certificate. That, of itself, when read in the context of the form as a whole, necessarily conveyed to a reasonable reader that Mr Frugtniet had been a fit and proper person and company secretary as at the compliance date of 24 December 2012, since he only ceased to be so on 12 January 2013. Secondly, ASIC knew, or must be taken to have known, of how its own electronic form operated to prevent listing someone in the field for fit and proper persons at the compliance date where that person’s name appeared in the field for persons who had ceased to be fit and proper persons.

54 Although recognising the difficulties she faced in completing online the 2012 compliance certificate, ASIC persevered, at the Tribunal, before the primary judge and on this appeal, with a submission that the proper course for Ms Callychurn was to “contact ASIC” about these matters and that, despite the difficulties referred to, the information she provided was false or misleading because, so it alleged, it did not reveal that Mr Frugtniet was a fit and proper person as at 24 December 2012. In the circumstances, when ASIC had recognised belatedly that its computer system did not allow the recording of a person as a fit and proper person during the year for which the compliance certificate applied once that person’s name was entered electronically in the field for notification of ceasing to be a fit and proper person, the appropriate course for ASIC to have adopted would have been to withdraw the allegation that there was anything false or misleading about the information provided (recorded at [12] above). As Griffith CJ said more than 100 years ago, it is “elementary” that the Commonwealth observe a “traditional, and almost instinctive, standard of fair play … in dealing with subjects”: Melbourne Steamship Co Ltd v Moorehead (1912) 15 CLR 333 at 342.

Another issue

55 We set out at [10] above another question which Ms Callychurn answered in the affirmative in both the 2011 and 2012 compliance certificates. That question relevantly was as follows: “Does the licensee certify that it has no reason to believe that any of its fit and proper people have … been the subject of administrative … proceedings … which were determined adversely to them …?”. On the material before us the affirmative answer to that question was, in all the circumstances, self-evidently untrue, to Ms Callychurn’s knowledge, since she knew of the VCAT order. However, ASIC did not rely on that answer before the Tribunal, the primary judge or on the hearing of this appeal (by way of notice of contention or otherwise).

Conclusion

56 For the reasons set out above, the appeal must be allowed and the matter be remitted to the Tribunal for hearing according to law. ASIC must pay Ms Callychurn’s costs of the appeal. There should be no order for costs of the proceeding before the primary judge.

I certify that the preceding fifty-six (56) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Rares, Collier and O’Callaghan. |

Associate: