FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Northern Territory of Australia v Griffiths [2017] FCAFC 106

Solicitor for the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples: | Northern Land Council |

Counsel for the Attorney-General for the State of South Australia: | Mr C D Bleby SC |

Solicitor for the Attorney-General for the State of South Australia: | Crown Solicitor’s Office |

Counsel for the Central Desert Native Title Services Limited and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation: | Mr S Wright |

Solicitor for the Central Desert Native Title Services Limited and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation: | Central Desert Native Title Services Limited and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation |

Counsel for the Attorney-General for the State of Western Australia: | Mr P Quinlan SC with Mr T C Russell |

Solicitor for the Attorney-General for the State of Western Australia: | State Solicitor’s Office |

Table of Corrections | |

27 July 2017 | In the Appearances on the cover page in the field Counsel for the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples the words "and Ms S Ms Zeleznikow" after " Mr G Hill" have been added. |

24 August 2017 | In the first paragraph of the extract quoted at paragraph 179, the transcript is in error. The parties are agreed that the last word “thrust” should be “trust”. “[Sic]” has been added after “thrust” to indicate that the transcript is in error. |

24 August 2017 | In the second sentence of paragraph 208, “of” has been substituted for “if”. |

ORDERS

BETWEEN: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Appellant |

AND: | ALLAN GRIFFITHS AND LORRAINE JONES ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES First Respondent NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Second Respondent |

AND BETWEEN: | ALLAN GRIFFITHS AND LORRAINE JONES ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES Cross-Appellant |

AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent |

ATTORNEY-GENERAL FOR THE STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA (and others named in the Schedule) First Intervener | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4 August 2017 the parties file an agreed form of orders necessary to reflect these reasons for judgment.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

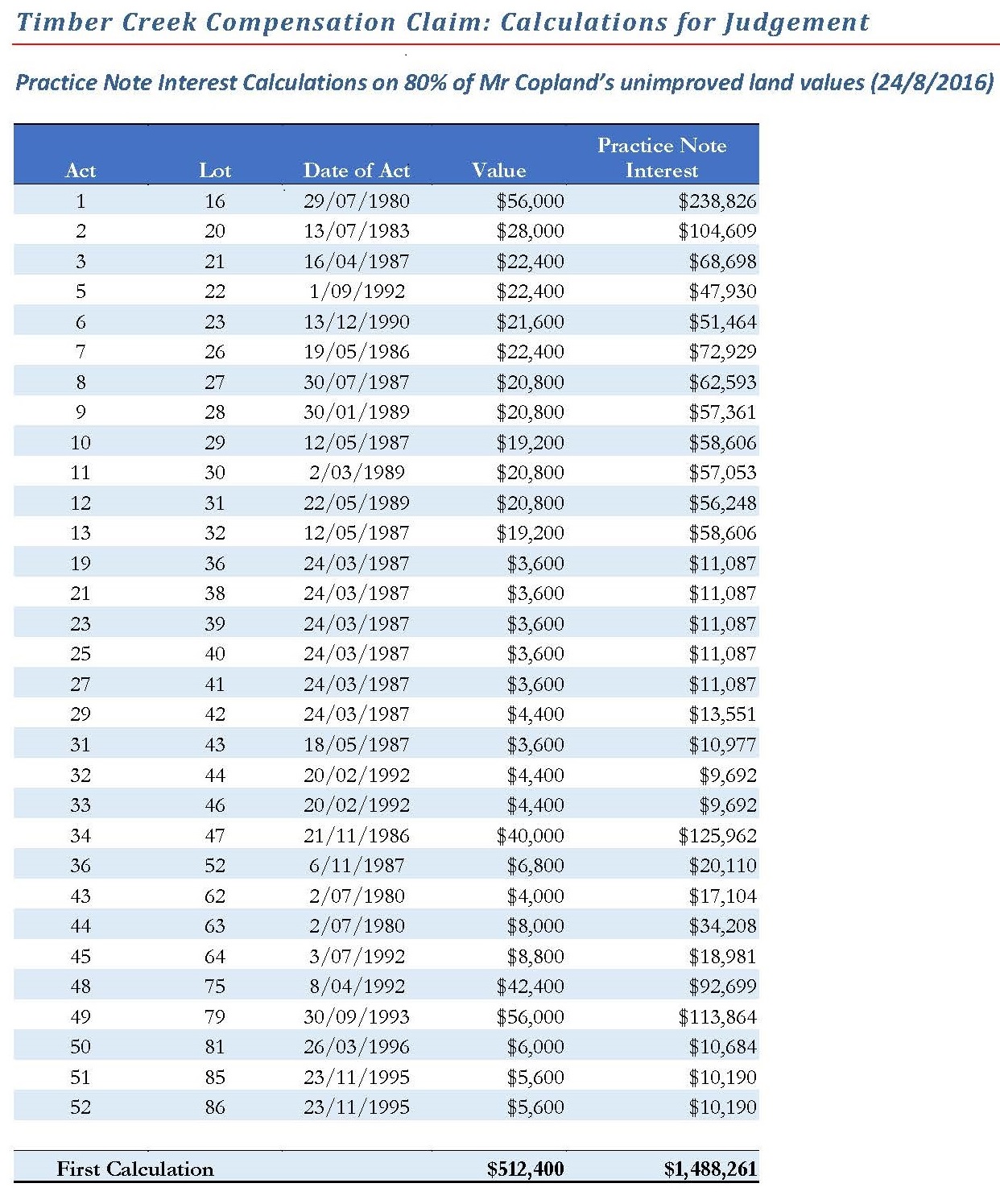

1 On 24 August 2016, the primary judge made orders against the Northern Territory and the Commonwealth on an application under s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA) brought by the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples (the Claim Group) for compensation and damages for the loss, diminution of, impairment or other effect of the act on their native title rights and interests. He awarded the Claim Group $512,400 compensation for the economic value of their extinguished native title rights, interest on this sum of $1,488,261. He also awarded the Claim Group $1,300,000 for solatium for the loss or impairment of those rights and interests. The primary judge made a declaration that three grants of freehold interests made by the Northern Territory were invalid future acts, and he awarded $19,200 damages together with interest of $29,397, making a total of $48,597 damages for those acts.

2 Before the Court is an appeal by the Northern Territory, a cross appeal to that appeal by the Claim Group and a separate appeal by the Commonwealth in relation to these orders (which are together referred to as the appeals).

3 The Attorney-General for the State of South Australia and the Attorney-General for the State of Queensland intervened in response to notices served under s 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (Judiciary Act) by the Commonwealth. The Attorney-General for South Australia made written and oral submissions in the appeals but the Attorney-General for Queensland played no further part in the appeals. The Attorney-General for the State of Western Australia intervened in response to a notice served under s 78B of the Judiciary Act by the Claim Group. The Attorney-General for the State of Western Australia also applied to intervene on a non-constitutional point pursuant to r 9.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011. The application was listed for hearing on the last day of the hearing of the appeals, 24 February 2017. The application was refused. The reasons for refusal are dealt with later in these reasons for judgment.

4 On 20 February 2017, two Native Title Representative Bodies, Central Desert Native Title Services and Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation, the NTRB interveners, were granted leave to intervene without opposition by the parties.

5 One consequence of the recognition of native title rights and interests by the NTA was the need to provide for the situation in which governments had made grants of land which, by reason of the recognition of native title, were inconsistent with the provisions of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (the RDA). The NTA addressed the issue by providing for validation of those acts, by providing for the consequence of validation on native title rights and interests including extinguishment or suspension, and then by providing for an entitlement to compensation to the native title holders.

6 Against this background it is necessary for the purposes of a compensation claim under the NTA and for the general law claim for damages to identify the land involved, the acts which gave rise to the right to compensation or damages, the source of the entitlement to compensation and the native title rights and interests for which compensation or damages were sought. There is no contention in the appeals about these matters, but it is necessary to outline them for a proper understanding of the arguments on the appeal. Those matters are now addressed.

7 The claim for compensation and damages was made in respect of land within the town of Timber Creek. Timber Creek is in the north west corner of the Northern Territory on the Victoria Highway half way between Katherine and Kununurra. Timber Creek was proclaimed as a town on 10 May 1975. The Victoria River marks the northern boundary of the town. The creek which is Timber Creek is a tributary of the Victoria River and flows approximately north / south on the eastern side of the town.

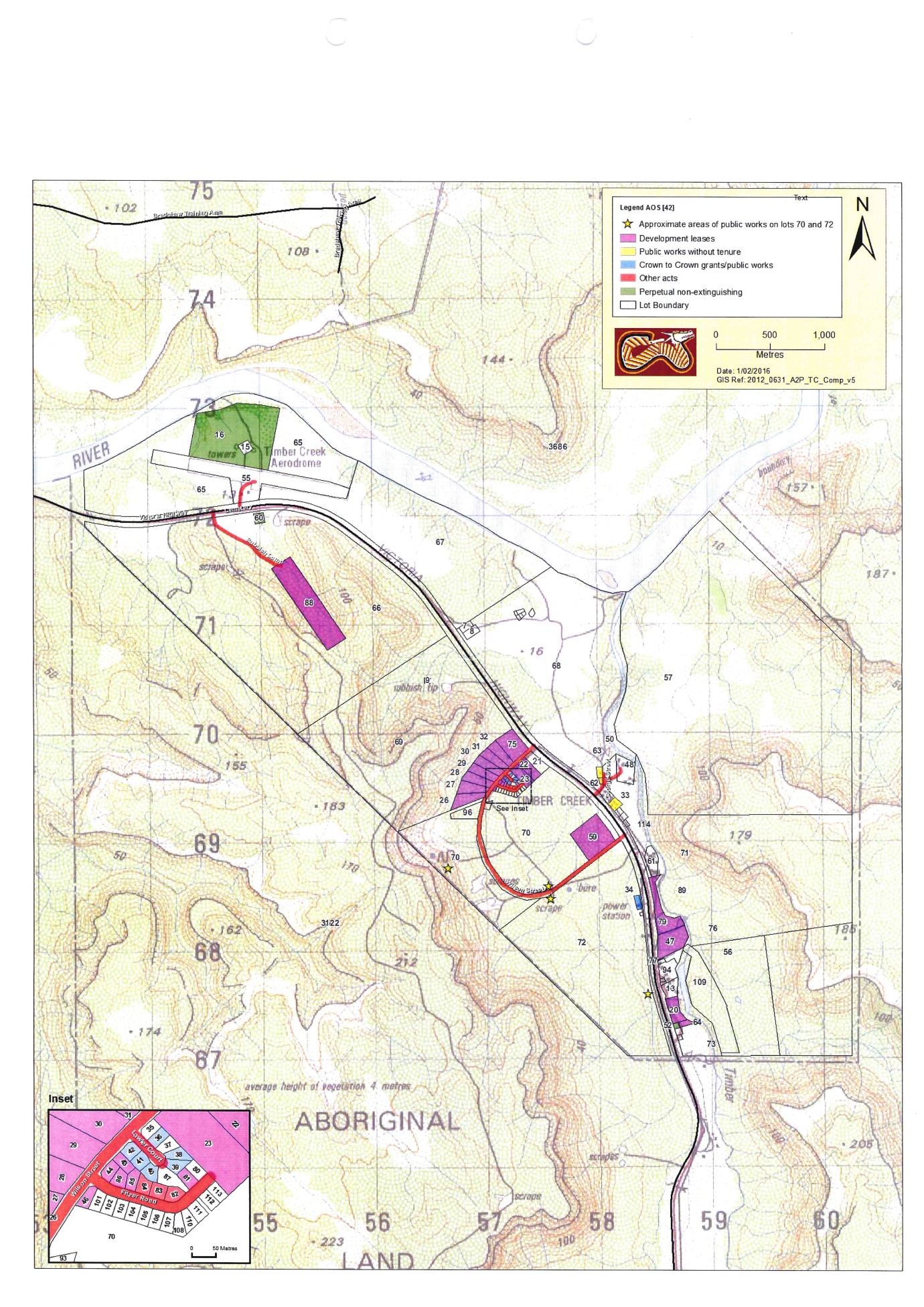

8 The compensation claim was made for 53 acts, on 39 lots and four public roads and the damages claim was made for 3 acts on 3 lots. Each of the acts was attributed to the Northern Territory. The map below shows the lots in question:

9 The acts for which compensation is claimed are tabulated below in a summary which is modified from the chronology filed by the parties for the purpose of the appeals.

10 Compensable acts that were not previous exclusive possession acts and which are referred to as the exceptions are marked with an *. Subsequent previous exclusive possession acts are marked with a †. Exceptions that were not subject to subsequent previous exclusive possession acts are marked with **. Compensable acts which were used for the calculation of economic loss are bolded. “NT” means the Northern Territory. These markings are further explained in this section of these reasons for judgment.

1980 | Act 56: Public works by NT – Lawler Road |

1980 | Act 59: Public works by NT – George and O’Keefe Streets |

1980 | Act 46 (part of Lot 70): Public works by NT – water tanks |

1980 | Act 43 (Lot 62): Public works by NT – dwelling |

1980 | Act 44 (Lot 63): Public works by NT – dwelling |

29 July 1980 | Act 1** (part of Lot 16): Grant SPL 494 to Conservation Land Corporation |

1982 | Act 58: Public works by NT – Wilson Street |

15 July 1982 | Act 15* (part of Lot 34): Grant freehold to NT Electricity Commission |

13 July 1983 | Act 2 (Lot 20): Grant CLT 210 to Huja Nominees Pty Ltd |

1984 | Act 14 (Lot 33): Public works – school |

1984 | Act 47 (part of Lot 72): Public works by NT – water bores and pipes |

1985 | Act 57: Public works by NT – Fitzer Road |

1985 | Act 16† (part of Lot 34): Public works by NT Electricity Commission |

1985 | Act 18† (part of Lot 34): Public works by NT Electricity Commission |

28 June 1985 | Act 17* (part of Lot 34): Grant freehold to NT Electricity Commission |

19 May 1986 | Act 7 (Lot 26): Grant CLT 535 to IR McBean |

21 November 1986 | Act 34 (Lot 47): Grant CLT 624 to LL Fogarty |

24 March 1987 | Act 19* (Lot 36): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

24 March 1987 | Act 21* (Lot 38): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

24 March 1987 | Act 23* (Lot 39): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

24 March 1987 | Act 25* (Lot 40): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

24 March 1987 | Act 27** (Lot 41): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

24 March 1987 | Act 29* (Lot 42): Grant freehold to NT Housing Commission |

16 April 1987 | Act 3* (Lot 21): Grant freehold to Conservation Land Corporation |

12 May 1987 | Act 10 (Lot 29): Grant CLT 674 to DF Walsh |

12 May 1987 | Act 13 (Lot 32): Grant CLT 656 to RD & GI Blakeney |

18 May 1987 | Act 31 (Lot 43): Grant CLT 657 to JV King |

30 July 1987 | Act 8 (Lot 27): Grant CLT 674 to Ngaringman Resource Centre Inc. |

6 November 1987 | Act 36** (Lot 52): Grant freehold to Commonwealth |

1988 | Act 20† (Lot 36): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

1988 | Act 22† (Lot 38): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

1988 | Act 24† (Lot 39): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

1988 | Act 26† (Lot 40): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

1988 | Act 30 (Lot 42): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

30 January 1989 | Act 9† (Lot 28): Grant CLT 851 to J Shaw |

2 March 1989 | Act 11† (Lot 30): Grant CLT 861 to BJ Draper |

22 May 1989 | Act 12 (Lot 31): Grant CLT 852 to DJ & B Wegener |

13 December 1990 | Act 6 (Lot 23): Grant CLT 1017 to LW Hudson |

1991 | Act 28 (Lot 41): Public works by NT Housing Commission |

8 May 1991 | Act 41* (Lot 60): Cemetery Reserve |

20 February 1992 | Act 32 (Lot 44): Grant CLT 1070 to Ngaringman Resource Centre Inc. |

20 February 1992 | Act 33 (Lot 46): Grant CLT 1071 to Ngaringman Resource Centre Inc. |

8 April 1992 | Act 48 (Lot 75): Grant CLT 1095 to MR Millwood Pty Ltd |

3 July 1992 | Act 45 (Lot 64): Grant CLT 1083 to Stamen Investments Pty Ltd |

11 August 1992 | Act 40 (Lot 59): Grant CLT 999 to Timber Creek Sports and Recreation Association |

1 September 1992 | Act 5 (Lot 22): Grant CLT 1049 to K Fikert |

8 January 1993 | Act 4† (Lot 21): Transfer of freehold to PR Rowe |

30 September 1993 | Act 49 (Lot 79): Grant CLT 1274 to Timber Creek Community Government Council |

23 November 1995 | Act 51 (Lot 85): Grant CLT 1552 to Ngaringman Aboriginal Resource Centre Inc. |

23 November 1995 | Act 52 (Lot 86): Grant CLT 1553 to Ngaringman Aboriginal Resource Centre Inc. |

26 March 1996 | Act 50 (Lot 81): Grant CLT 1568 to Timber Creek Community Government |

11 September 1996 | Act 53 (Lot 88): Grant CLP 1621 to Timber Creek Community Government Council |

17 December 1996 | Act 54 (Lot 89): Grant CLT 1673 to Telstra Corporation |

11 The parties filed a Joint Statement of Factual Background, Procedural History and Issues (Joint Statement), for the purpose of the appeals which contains a useful summary of the nature of the compensable acts divided into the following five categories (references to orders are references to the orders made by the primary judge):

(a) grants of development leases by the Territory to non-Crown entities that could be exchanged for freehold upon satisfaction of a development covenant. Each grant was a previous exclusive possession act that extinguished all subsisting native title. The grants of these development leases were: act 2 (Lot 20), acts 5-13 (Lots 22-23, 26-32), acts 31-33 (Lots 43-44, 46), act 40 (Lot 59), act 45 (Lot 64), acts 48-[54] (Lots 75, 79, 81, 85-86, 88[-89]) (order [1(3)]).

(b) grant of a Crown lease (CLT 624) for a period of 10 years that was a previous exclusive possession act that extinguished all subsisting native title. The grant of this lease was act 34 (Lot 47) (order [1(6)]).

(c) public works constructed without any underlying tenure. Each public work was a previous exclusive possession act that extinguished all subsisting native title. These were: act 14 (Lot 33), acts 43-44 (Lots 62-63), act 46-47 (part of Lots 70 and 72 respectively), acts 56-59 (roads) (order [1(4)]).

(d) Crown to Crown grants by the Territory to government authorities, followed by (in one case) a subsequent transfer of the land to a non-Crown entity or (in all other cases) public works established on the granted land. Each initial Crown to Crown grant was a Category D past act that suppressed all subsisting native title. Each later public works act was a previous exclusive possession act that extinguished native title. Consequently, in this category, two or more compensable acts affected a single parcel of land. These were: acts 3-4 (Lot 21), acts 15-18 (Lot 34), acts 19-20 (Lot 36), acts 21-22 (Lot 38), acts 23-24 (Lot 39), acts 25-26 (Lot 40), acts 27-28 (Lot 41), acts 29-30 (Lot 42) (order [1(2)]).

(e) three Crown to Crown grants in perpetuity by the Territory to government authorities. Each grant was a Category D past act that suppressed (and continues to suppress) all subsisting native title. These grants were: act 1 (part of Lot 16), act 36 (Lot 52), act 41 (Lot 60) (order [1(1)]).

12 For the purpose of calculating the economic loss component of the compensation to be awarded, the Claim Group did not claim compensation for acts in relation to what the primary judge referred to as the infrastructure lots. That was because it was a common position between the land valuers called by the parties that it was not appropriate to add or assess a separate value for the acts done by the establishment of the infrastructure lots, as those acts affected the value of the other lots. Thus, no compensation for economic loss was awarded for acts 4, 14-18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 40-41, 46-47, 53-54, 56-59, comprising various public and infrastructure works. The remaining acts, for which compensation for economic loss was awarded, have been bolded in the table at [10].

13 In summary, the total compensation claim related to 53 acts on 39 lots and four public roads. Compensation for economic loss was claimed for 31 of those acts, on 31 lots.

The Source of the Entitlement to Compensation under the NTA

14 The right to claim compensation depends on the character of the act which the NTA validates. So far as is relevant to these appeals, the source of the entitlement depends on whether the act validated was a past act, an intermediate period act, or a previous exclusive possession act within the meaning of Part 2, Div 2, 2A, and 2B of the NTA.

15 Different consequences flow from validation depending on the classification of the act. Relevantly for the appeals, validation of an exclusive possession act results in the extinguishment of native title, and validation of a category D past act attracts the non-extinguishment principle (s 238).

16 The analysis below demonstrates that all but three of the lots in issue were initially, or ultimately, affected by exclusive possession acts. The remaining three lots were affected by category D past acts.

17 Division 2 of Part 2 of the NTA deals with past acts. A past act is an act, which occurred before 1 January 1994 where native title existed in relation to particular land, which was invalid to any extent but would have been valid to that extent if native title did not exist (s 228 NTA). A category A past act relates to a grant of certain freehold estates, certain leases and construction of certain public works (s 229 NTA). A category B past act relates to certain leaseholds (s 230 NTA). A category C past act relates to mining leases (s 231 NTA). A category D past act is one which is not a category A, B or C past act (s 232 NTA). The past acts in question in these appeals were acts attributed to the Northern Territory (s 239 NTA) and were validated by operation of s 19 of the NTA and s 4 of the Validation (Native Title) Act (NT) (VNTA). Category A past acts extinguish native title, category B past acts extinguish native title to the extent of any inconsistency and the non-extinguishment principle applies to category C and D past acts (s 15 NTA). Where the non-extinguishment principle applies, the act does not extinguish native title, but native title may be suspended wholly or in part to take account of the act (s 238 NTA).

18 All of the acts, save for acts 50, 51, 52, 53, and 54, were past acts. The latter five acts were not past acts because they occurred after 1 January 1994, namely from November 1995 to December 1996.

19 Division 2A of Part 2 of the NTA deals with intermediate period acts. These provisions were inserted by the 1998 amendments to address the uncertainty said to have been created by the judgment in Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1; [1996] HCA 40 (Wik) which was delivered on 23 December 1996.

20 An intermediate act is an act, which occurred between 1 January 1994 and 23 December 1996 where native title existed in relation to particular land, which was invalid to any extent but would have been valid to that extent if native title did not exist. Acts 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54 occurred during this period and were intermediate period acts. Intermediate period acts were validated by the operation of s 22F of the NTA and s 4A of the VNTA.

21 Division 2B of Part 2 of the NTA entitled “Confirmation of past extinguishment of native title by certain valid or validated acts” also inserted as a result of Wik, deals with previous exclusive possession acts. A previous exclusive possession act is a grant such as freehold or of certain leases which was made before 23 December 1996 and which was validated under Part 2 or Part 2A of the NTA (s 23B NTA). Therefore, both past and intermediate acts may be previous exclusive possession acts. A previous exclusive possession act attributable to the Northern Territory extinguished native title (s 9H VNTA). The extinguishment was effected by the previous exclusive possession provisions, and not by the past act or the intermediate past act provisions (s 9G VNTA).

22 The compensable acts were previous exclusive possession acts except for acts 1, 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 36 and 41, which together are referred to as the exceptions. As can be seen from the table in [10] of these reasons for judgment, six of the exceptions were freehold grants to the Northern Territory Housing Commission, two were freehold grants to the Conservation Land Corporation, two were freehold grants to the Northern Territory Electricity Commission, one was a freehold grant to the Commonwealth, and one was a cemetery reserve. The exceptions are marked with an * in the table in [10]. These acts were within various exceptions to the definition of previous exclusive possession acts in s 23B of the NTA, mainly the exception in respect of Crown to Crown grants (s 23B(9C) NTA).

23 The exceptions were category D past acts within the meaning of s 232 of the NTA. They were not category A, B, or C past acts in particular because they were grants of freehold by the Crown to a statutory authority of the Crown and hence within the exception to category A past acts contained in s 229(2)(b)(i) of the NTA.

24 The non-extinguishment principle would then apply to the exceptions. However, except in the case of act 1 (grant to the Conservation Land Corporation), act 36 (freehold grant to the Commonwealth) and act 41 (cemetery reserve), the past acts were followed by previous exclusive possession acts which extinguished native title. This can be seen from the table in [10] of these reasons for judgment. Each subsequent previous exclusive possession act is marked with a † in the table. Act 3 was followed by act 4 which was a grant of freehold. Act 15 was followed by act 16, and act 18 by act 17, the latter act in each case being public works by the Northern Territory Electricity Commission except for the final act, act 17, which was a grant of freehold to the Northern Territory Electricity Commission. Acts 19, 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29 were each followed by an act in the next numerical sequence, and each of those latter acts were public works by the Northern Territory Housing Commission. Certain public works are previous exclusive possession acts (s 23B(7) NTA).

25 Acts 1, 36 and 41 were not followed by a subsequent previous exclusive possession act. As category D past acts the non-extinguishment principle continued to apply to them. These three acts are marked with ** in the table in [10] of these reasons for judgment. Apart from these three acts, all the other compensable acts were previous exclusive possession acts.

26 The entitlement to compensation for exclusive possession acts is in s 23J of the NTA which is in Div 2B which provides:

23J Compensation

Entitlement

(1) The native title holders are entitled to compensation in accordance with Division 5 for any extinguishment under this Division of their native title rights and interests by an act, but only to the extent (if any) that the native title rights and interests were not extinguished otherwise than under this Act.

Commonwealth acts

(2) If the act is attributable to the Commonwealth, the compensation is payable by the Commonwealth.

State and Territory acts

(3) If the act is attributable to a State or Territory, the compensation is payable by the State or Territory.

27 The entitlement to compensation for category D past acts is in s 20 of the NTA, which is in Division 2 of Part 2, and which in turn refers back relevantly to s 17(2)(a):

20 Entitlement to compensation

Compensation where validation

(1) If a law of a State or Territory validates a past act attributable to the State or Territory in accordance with section 19, the native title holders are entitled to compensation if they would be so entitled under subsection 17(1) or (2) on the assumption that section 17 applied to acts attributable to the State or Territory.

…

Recovery of compensation

(3) The native title holders may recover the compensation from the State or Territory.

…

17 Entitlement to compensation

...

Non-extinguishment case

(2) If it is any other past act, the native title holders are entitled to compensation for the act if:

(a) the native title concerned is to some extent in relation to an onshore place and the act could not have been validly done on the assumption that the native title holders instead held ordinary title to:

(i) any land concerned; and

(ii) the land adjoining, or surrounding, any waters concerned; or

…

The Native Title Rights and Interests

28 As the compensation claimed relates to the loss of native title rights and interests it is necessary to identify those rights and interests. There is some background to the way those rights and interests were identified for this proceeding.

29 In 1999 and 2000 the Claim Group applied to the Court for a determination of native title over vacant Crown land within the township of Timber Creek. That application was determined by Weinberg J in Griffiths v Northern Territory (2006) 165 FCR 300; [2006] FCA 903 (Griffiths SJ). Following an appeal in Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia (2007) 165 FCR 391; [2006] FCAFC 178 (Griffiths FC) it was determined that the Claim Group had exclusive native title rights and interests over most of the land in the township of Timber Creek, and, by the operation of s 47B of the NTA, previous extinguishing acts were to be disregarded.

30 Most of the lots for which compensation was claimed in the present proceedings were not included in the earlier native title determination applications. But the parties to the compensation application agreed that the Claim Group held native title in respect of the lots in question and agreed on the nature of the acts for which compensation was claimed. There was disagreement about the effect of some prior acts on native title, and hence on what native title rights were to be the subject of compensation.

31 Before the primary judge embarked on the assessment of the amount of compensation, he determined whether native title had been extinguished or partly extinguished by historic tenure grants, reservations, or public works, and whether that extinguishment occurred before the RDA came into effect: Griffiths v Northern Territory [2014] FCA 256 (Compensation Decision Part 1). Significantly for present purposes is the finding by the primary judge in Compensation Decision Part 1 [41] - [43] that Pastoral Lease 366 granted on 20 June 1882 (PL366), under the Northern Territory Land Act 1872 (SA) to the Musgrave Range and Northern Territory Pastoral Land Co Ltd, which covered all of the relevant parts of the application area, was effective at common law to partially extinguish native title leaving non-exclusive native title rights and interests.

32 The parties then adopted, for the purposes of the compensation application, the description of such interests from the native title determination made in Griffiths FC which had been the result of a full trial in Griffiths SJ and thus the result of a detailed examination by Weinberg J of Indigenous and expert evidence about the traditional laws and customs of the Claim Group in relation to land in and around Timber Creek.

33 The description of the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests adopted by the parties was set out in [23(3)] of the Joint Statement as follows:

Where the native title had not been wholly extinguished, but had been partially extinguished by an earlier act, the native title rights and interests were the following non-exclusive rights in accordance with traditional laws and customs:

1. the right to travel over, move about and to have access to the application area;

2. the right to hunt, fish and forage on the application area;

3. the right to gather and to use the natural resources of the application area such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin;

4. the right to have access to and use the natural water of the determination area;

5. the right to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters and other structures;

6. the right to:

(a) engage in cultural activities;

(b) conduct ceremonies;

(c) hold meetings;

(d) teach the physical and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance on or in the land and waters; and

(e) participate in cultural practices relating to birth and death, including burial rights;

7. the right to have access to, maintain and protect sites of significance on the application area; and

8. the right to share or exchange subsistence and other traditional resources obtained on or from the land or waters (but not for any commercial purposes).

THE FRAMEWORK FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF COMPENSATION

34 The way compensation is to be assessed is governed by s 51 of the NTA which relevantly provides:

51 Criteria for determining compensation

Just compensation

(1) Subject to subsection (3), the entitlement to compensation under Division 2, 2A, 2B, 3 or 4 is an entitlement on just terms to compensate the native title holders for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of the act on their native title rights and interests.

…

Compensation not covered by subsection (2) or (3)

(4) If:

…

(b) there is a compulsory acquisition law for the Commonwealth (if the act giving rise to the entitlement is attributable to the Commonwealth) or for the State or Territory to which the act is attributable;

the court, person or body making the determination of compensation on just terms may, subject to subsections (5) to (8), in doing so have regard to any principles or criteria set out in that law for determining compensation.

Monetary compensation

(5) Subject to subsection (6), the compensation may only consist of the payment of money.

…

35 Section 51A or the NTA imposes a limit on compensation in the following terms:

51A Limit on compensation

Compensation limited by reference to freehold estate

(1) The total compensation payable under this Division for an act that extinguishes all native title in relation to particular land or waters must not exceed the amount that would be payable if the act were instead a compulsory acquisition of a freehold estate in the land or waters.

This section is subject to section 53

(2) This section has effect subject to section 53 (which deals with the requirement to provide “just terms” compensation).

36 Section 53(1) provides for an additional entitlement to compensation whenever that is required to avoid invalidity by reason of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. It is as follows:

Entitlement to just terms compensation

(1) Where, apart from this section:

(a) the doing of any future act; or

(b) the application of any of the provisions of this Act in any particular case;

would result in a paragraph 51(xxxi) acquisition of property of a person other than on paragraph 51(xxxi) just terms, the person is entitled to such compensation, or compensation in addition to any otherwise provided by this Act, from:

(c) if the compensation is in respect of a future act attributable to a State or a Territory – the State or Territory; or

(d) in any other case – the Commonwealth;

as is necessary to ensure that the acquisition is made on paragraph 51(xxxi) just terms.

37 There is a compulsory acquisition law for the Northern Territory in the form of the Lands Acquisition Act (NT) (LAA), s 5 of which requires the LAA to be read so as to provide for the acquisition of land on just terms.

38 Section 66 of the LAA provides relevantly that in assessing compensation the relevant Tribunal must have regard to, but is not bound by, the Rules set out in Schedule 2 (as modified in respect of the acquisition of native title rights and interests).

39 Schedule 2 provides relevantly:

Schedule 2 Rules for the assessment of compensation

1. VALUE TO THE OWNER

Subject to this Schedule, the compensation payable to a claimant for compensation in respect of the acquisition of land under this Act is the amount that fairly compensates the claimant for the loss he has suffered, or will suffer, by reason of the acquisition of the land.

1A. RULES TO EXTEND TO NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS AND INTERESTS

To the extent possible, these rules, with the necessary modifications, are to be read so as to extend to and in relation to native title rights and interests.

2. MARKET VALUE, SPECIAL VALUE, SEVERANCE DISTURBANCE

Subject to this Schedule, in assessing the compensation payable to a claimant in respect of acquired land the Tribunal may take into account:

(a) the consideration that would have been paid for the land if it had been sold on the open market on the date of acquisition by a willing but not anxious seller to a willing but not anxious buyer;

(b) the value of any additional advantage to the claimant incidental to his ownership, or occupation of, the acquired land;

(c) the amount of any reduction in the value of other land of the claimant caused by its severance from the acquired land by the acquisition; and

(d) any loss sustained, or cost incurred, by the claimant as a natural and reasonable consequence of:

(i) the acquisition of the land; or

(ii) the service on the claimant of the notice of proposal,

for which provision is not otherwise made under this Act, other than costs incurred as a result of attending, participating in or being represented at consultations for the purposes of section 37(1) or mediation under section 37(4).

…

9. INTANGIBLE DISADVANTAGES

(1) If the claimant, during the period commencing on the date on which the notice of proposal was served and ending on the date of acquisition:

(a) occupied the acquired land as his principal place of residence; and

(b) held an estate in fee simple, a life estate or a leasehold interest in the acquired land,

the amount of compensation otherwise payable under this Schedule may be increased by the amount which the Tribunal considers will reasonably compensate the claimant for intangible disadvantages resulting from the acquisition.

(2) In assessing the amount payable under subrule (1), the Tribunal shall have regard to:

(a) the interest of the claimant in the land;

(b) the length of time during which the claimant resided on the land;

(c) the inconvenience likely to be caused to the claimant by reason of his removal from the acquired land;

(d) the period after the acquisition of the land during which the claimant has been, or will be, allowed to remain in possession of the land;

(e) the period during which the claimant would have been likely to continue to reside on the land; and

(f) any other matter which is, in the Tribunal’s opinion, relevant to the circumstances of the claimant.

40 The compensation application claimed compensation under two heads. One head of claim was the economic loss caused by the acts which deprived the Claim Group of their native title rights and interests or impaired those rights and interests. The other head of claim was the non-economic effect of those acts on the Claim Group. The Northern Territory and the Commonwealth did not contest that general framework. The primary judge adopted that framework for his assessment for the amount of compensation.

41 For the purpose of fixing the amount of compensation, s 51(4)(b) of the NTA allows the Court to have regard to the principles in any relevant compulsory acquisition legislation. That is probably because there are points of similarity between a compulsory acquisition of land and the deprivation or impairment of native title rights and interests without the agreement of the native title holders.

42 The basis for distinguishing between the two elements of compensation was said to flow from the different nature of each element. The economic element reflects the loss of the material asset which flows from the acts of extinguishment. The non-economic element reflects the effects on the connection of the native title holders with their country. The assessment of the non-economic impact of the acts of extinguishment requires an understanding of the intense bond between Indigenous people and their country. The evaluation of that element presents difficulty because of the unique nature of the spiritual link between the people and the land and the need to place a monetary value on the disruption to that connection. In this respect it must be remembered that the compulsory acquisition legislation is concerned with valuing land, whereas assessing compensation for the loss or impairment of native title rights and interests requires an evaluation of emotional rather than pecuniary impact. Later in these reasons for judgment at [140] we point to an alternative approach and raise the question whether the bifurcated approach adopted by the parties in this proceeding to the assessment of compensation under the NTA is the preferable approach.

43 Within the framework adopted by the parties and the primary judge there are six major issues raised by the appeals.

44 The first issue concerned the primary judge’s assessment of the economic loss element of the award of compensation. Each of the parties made a different challenge to the economic value of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests as determined by the primary judge. He assessed that element at 80% of the freehold value of the land, namely, the sum of $512,400. The Northern Territory contended that the appropriate measure is the sum of the usage value and the negotiation value. That method yields a value of $248,764 using the same land valuation as used by the primary judge. The Commonwealth contended that if all relevant factors were taken into account the native title rights and interests would have been assessed at about 50% of the freehold value of the land. The Claim Group contended that the appropriate measure of the value of their native title rights and interest was equal to the freehold value of the land.

45 The second issue concerned the assessment of the value of some of the freehold lots. The Northern Territory contended that the primary judge should have preferred the valuation of Mr Wotton over the valuation of Mr Copland in respect of the two hectare lots (lots 20 – 23 and 26 – 32) and the large rural lots over four hectares (lots 16, 47, 75 and 79).

46 The third issue concerned the prejudgment interest payable on the compensation awarded for economic loss. The primary judge held that the interest was part of the compensation and was to be calculated on the basis of simple interest at the rate set out in the Federal Court Practice Note CM 16, the practice note rate. The Claim Group contended that interest should be calculated on a compound basis, either on the risk-free rate or the superannuation rate. The Commonwealth contended that the interest should have been awarded on, rather than as part of, the award of compensation. The Commonwealth also contended that interest in respect of lot 47 (act 34) should have ceased on 28 August 2006 when Griffiths SJ made a determination that the Claim Group hold exclusive native title over most of the town including lot 47.

47 The fourth issue concerned the calculation of non-economic loss which the primary judge fixed at $1.3 million. The Northern Territory and the Commonwealth both challenged this amount and the reasoning by which the primary judge arrived at it. The Northern Territory contended that the amount should be 10% of the value of the land proposed by the Northern Territory producing a final figure of $93,848. The Commonwealth contended that, having regard to all the circumstances of the case, the amount of non-economic loss should have been assessed at $5,000 for each parcel of land, yielding a lump sum amount of $215,000.

48 The fifth issue concerned [6] of the orders made by the primary judge which provides for the Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) to allocate the award monies within the Claim Group and to determine any disputes about entitlements to the monies. The Commonwealth contended that s 94 of the NTA did not empower the Court to make that order.

49 The sixth issue concerned three invalid future acts. The Northern Territory contended that there was no basis for the making of orders for the payment of damages for those acts. Alternatively, if there was a basis, the Northern Territory contested the calculation of damages at 80% of the freehold value of the land. The Commonwealth contended that there was no basis for the primary judge to grant relief of any kind that does not have as its premise the continuing existence of the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests.

50 These reasons for judgment will now consider each of the six issues in turn.

DID THE PRIMARY JUDGE ERR IN ASSESSING ECONOMIC LOSS AT $512,400?

51 The primary judge reasoned as follows:

(1) The starting point is s 51(1) of the NTA which provides for compensation on just terms to compensate the native title holders for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of the act on their native title rights and interests.

(2) The conventional approach to the valuation of interests in land established in Spencer v Commonwealth (1907) 5 CLR 418; [1907] HCA 82 (Spencer) seems inappropriate. It is artificial to focus on a willing but not anxious purchaser when the only purchaser could be the Northern Territory or the Commonwealth, and the interest could not be sold to a third party. It is also artificial to consider the price which the native title holders would be prepared to sell their rights when the rights are not able to be sold.

(3) It is not appropriate to seek to compare the bundle of rights held by the native title holders with the bundle of rights held by others holding interests in land without taking account of the true character of the native title rights.

(4) The value of exclusive native title rights and interests is equivalent to the value of freehold. To reduce the value of such rights because they are inalienable would fail to have regard to the real character of the native title rights and interests. That was the accepted starting point in Geita Sebea v Territory of Papua (1941) 67 CLR 544; [1941] HCA 37 (Geita Sebea) and Amodu Tijani v Secretary, Southern Nigeria [1921] 2 AC 399 (Amodu Tijani). To treat exclusive native title rights and interests as less valuable than freehold would fail to reflect the purposes of the NTA and the recognition of the Aboriginal peoples as the original inhabitants of Australia.

(5) Where rights are removed or diminished by an act of the Crown it makes sense to focus on what has been obtained by the presumed willing but not anxious buyer even though there cannot be a willing but not anxious seller. Thus, in Geita Sebea the focus was on the benefit to the Crown of the acquisition rather than the detriment to the holders of indigenous rights where those rights were inalienable save to the Crown.

(6) In Geita Sebea the value of the native title rights was not regarded as less valuable because they were inalienable. By valuing the rights in that way shows that it was not appropriate to approach the valuation as an exercise of the valuation of rights of a conventional land holder. What the Crown acquired as a result of the transaction was different from what the indigenous rights holders enjoyed but, nonetheless, indicated that the rights surrendered had an economic value.

(7) It is necessary to start with a fuller understanding of the native title rights and interests. Native title is a sui generis right or interest. To describe it as a proprietary right is artificial and capable of misleading. It is a communal bundle of rights not an individual proprietary right. It depends for its existence on the continuing acknowledgement and observance of relevant traditions, custom, and practices of the community. It is principally usufructuary in nature and inalienable except by surrender to or acquisition by the Crown.

(8) Just as it is not appropriate to treat exclusive native title as valued at less than freehold, it is not routinely appropriate to treat non-exclusive native title rights and interests as valued in the same way as if those rights and interests were held by non-Indigenous persons, or to reduce the value of the right because they are inalienable, even though that might be a proper analysis if the rights were held by a non-Indigenous person.

(9) The non-exclusive native title rights held by the Claim Group were rights to travel over, move about and have access to the area; to hunt, fish and forage on the area; to gather and to use the natural resources of the area; to have access to and use the natural water of the area; to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters and other structures; to engage in cultural activities; to maintain and protect sites of significance on the area; and to share or exchange subsistence and other traditional resources obtained on or from the land or waters (but not for any commercial purposes).

(10) It is not appropriate to value these interests as equivalent to freehold on the basis that the Northern Territory acquired a freehold title on the extinguishment of those interests.

(11) Geita Sebea does not lead to that conclusion, but it does establish that the mere fact that the indigenous rights are inalienable does not mean that they have a value less than freehold.

(12) His Honour then said at [227] – [228]:

227. Consequently, whilst I do not accept the contention of the Claim Group that their non-exclusive native title rights should be valued as if they were the equivalent of exclusive native title rights, it is necessary to arrive at a value which is less than the freehold value and which nevertheless recognises and gives effect to the nature of those rights.

228 That is reflected in the contention of the Claim Group that their native title rights, even as the non-exclusive rights existed as a real impediment to any other grants of interest in the subject allotments, or more generally. The Territory, in this case, needed to acquire those rights before it could proceed to treat the land or the allotments as part of its radical title to enable it to grant freehold or leasehold interests over those lots. I note the contention on behalf of the Claim Group that, apart from the previous acts which in Griffiths SJ and in Griffiths FC were held partially to extinguish native title rights, there were no meaningful restrictions on their use and enjoyment of the relevant allotments. The only valid extinguishing acts prior to the determination acts were, it is said, the grants of pastoral leases which removed the right to exclusive possession, but in reality in relation to Timber Creek Township itself, that restriction or limitation was not a major restricting factor.

(13) His Honour then concluded at [231] – [232]:

231 But for the invalid determination acts, the native title rights which were held which [sic] were permanent, and in a practical sense very substantial. To accommodate the fact that they were non-exclusive, clearly some reduction from the freehold value is necessary. If that were not so, they would have the same value as exclusive native title rights when plainly they do not. However, in my view, the deduction should not be great in the present circumstances.

232 The rights the Claim Group in fact enjoyed were in a practical sense exercisable in such a way as to prevent any further activity on the land, subject to the existing tenures. If the appropriate test were as to the price at which the claim group would have been prepared to surrender their non-exclusive native title rights, the answer would be not at all. If the appropriate test was to see what was the value to the Territory of acquiring those rights, as the Territory would not then be restricted by the nature of those rights which were surrendered, the answer is that that would be a figure close to the freehold value. In my view, the appropriate valuation should be 80% of the freehold value.

52 The primary judge accepted the land valuations of Mr Ross Copland, an expert land valuer called by the Commonwealth, and used those valuations as the basis for the compensation to be awarded.

53 The amounts of compensation for each lot affected by each compensable act was tabulated in annexure B to the reasons for judgment of the primary judge as follows:

54 Grounds 1 and 2 of the Northern Territory’s Notice of Appeal read as follows:

1. The trial judge was wrong to find that the economic value of the native title rights and interests which were extinguished or impaired by the compensable acts for which compensation was claimed was 80% of the market value of freehold estates in the land the subject of the compensable acts.

1.1. There was no evidence that the economic value of the native title rights and interests was 80% of the market value of freehold estates in the land. Further, the finding is contrary to the expert evidence relied upon by the Appellant to the effect identified in Ground 2 below.

1.2. The trial judge erred in finding that the native title rights and interests were in a practical sense exercisable in such a way as to prevent any further activity on the land, subject to the existing tenures (Reasons, [232]). This equates to a finding that the native title rights and interests were equivalent to, or closely equivalent to, freehold rights and such a finding is erroneous because the native title rights and interests did not include the right to exclude others, to control access or to make decisions about the use of the land.

1.3. The trial judge erred in finding that the native title rights and interests existed as a real impediment to any other grants of interest in the subject allotments, or more generally, because the Appellant needed to acquire those rights before it could proceed to treat the land as part of its radical title and grant freehold or leasehold interests (Reasons, [228]). This finding erroneously disregards:

1.3.1. the prior partial extinguishment of native title which enlarged the Crown's radical title sufficiently to enable grants which had no greater effect on native title;

1.3.2. further or alternatively, that, prior to the enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), the Crown could and did make grants of interests in land without acquiring the native title rights and, upon the enactment of that Act and the Validation (Native Title) Act (NT), those grants would have been and were validated and taken always to have been valid.

1.4. The trial judge erred in finding that the value to the Appellant of acquiring the native title rights and interests would be a figure close to the freehold value (Reasons, [232)) The finding was erroneous:

1.4.1. for the reasons identified in Ground 1.3 above; and

1.4.2. further or alternatively, in light of his Honour's finding that compensation is not properly assessed simply on the basis that the Crown acquired radical or freehold title unencumbered by native title so freehold value is the appropriate measure (Reasons, [224]).

1.5. The trial judge erred in reaching the figure of 80% by focussing on the nature of the rights held (Reasons, [233]) because that finding encompasses his Honour's erroneous findings that it is not appropriate to (Reasons, [220]):

1.5.1. treat non-exclusive native title as valued in the same way as if those rights were held by a non-Indigenous person; or

1.5.2. reduce the value of non-exclusive native title because it is inalienable even though that may be the proper analysis if the rights were held by a nonIndigenous person.

Those findings are erroneous because they focus, not on the nature and incidents of the rights held, but on:

1.5.3. the identity (specifically the race) of the persons holding them; and

1.5.4. further or alternatively, the cultural or ceremonial significance of the land and/or the attachment to the land which the Claim Group as an Indigenous community has, despite disavowing having done so (Reasons, [234]).

2. The trial judge erred in failing to find that the economic value of the native title rights and interests which were extinguished or impaired by the compensable acts for which compensation was claimed was the sum of:

(a) the usage value, comprising the market value of the freehold estate in Lot 16, Town of Timber Creek calculated at the time of each compensable act and applied on a square metre basis to each parcel of land the subject of the compensable acts; and

(b) the negotiation value, comprising 50% of the difference between the market value of the freehold estate in each parcel of land the subject of the compensable acts and the usage value of each parcel of land the subject of the compensable acts.

2.1. The trial judge erroneously rejected the expert economic evidence of Mr Wayne Lonergan (who assessed the economic value of the native title rights and interests on the above basis), erroneously finding that it was inappropriate to assess the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights of usage in conventional economic terms by expressing the content of each of the native title rights in terms which would be used if each right existed in an entirely different context (such as under a lease or contract) and then to value them as a bundle with the practical and legal constraints they would carry with them (Reasons, 243]). The finding is erroneous because such an economic approach is entirely appropriate to the assessment of the economic value of a bundle of rights which is, as his Honour held (Reasons, [219]), principally usufructuary in nature.

2.2. The trial judge erred in finding that an economic approach was inappropriate because that finding encompasses his Honour's erroneous findings that it is not appropriate to (Reasons, [220]):

2.2.1. treat non-exclusive native title as valued in the same way as if those rights were held by a non-Indigenous person; or

2.2.2. reduce the value of non-exclusive native title because it is inalienable even though that may be the proper analysis if the rights were held by a non Indigenous person.

Those findings are erroneous because they focus, not on the nature and incidents of the rights held, but on:

2.2.3. the identity (specifically the race) of the persons holding them; and

2.2.4. further or alternatively, the cultural or ceremonial significance of the land and/or the attachment to the land which the Claim Group as an Indigenous community has, despite disavowing having done so (Reasons, [234]).

2.3. The trial judge erred in finding that the conventional valuation approach to the assessment of compensation for land compulsorily acquired as expressed in Spencer v Commonwealth (1907) 5 CLR 418 at 432 is inappropriate to the valuation of native title rights and interests (Reasons, [211]). The finding is erroneous because:

2.3.1. the conventional valuation approach is commonly adopted in determining the economic value of rights or interests in circumstances where those rights or interests cannot be sold or transferred at all, or can only be sold or transferred to limited parties, or would not be willingly sold or transferred by the holder;

2.3.2. further or alternatively, the conventional valuation approach is prescribed by item 2(a) of Schedule 2 of the Lands Acquisition Act (NT), and is thereby a relevant matter to which the Court may have regard in assessing compensation under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), by virtue of s51(4) of that Act.

55 Grounds 1 and 2 of the Commonwealth’s Supplementary Notice of Appeal read as follows:

1. The primary judge erred in finding that the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights in question should be assessed at 80 percent of the freehold market value of the relevant land (Reasons [232]). The core reasoning underpinning the primary judge’s selection of 80 percent of freehold market value is found in Reasons at [231]-[232], and is infected by the following errors:

(a) the primary judge was wrong to characterise the non-exclusive native title rights as being “in a practical sense very substantial” (Reasons [231]);

(b) the primary judge was wrong to find that the non-exclusive native title rights “were exercisable in such a way as to prevent any further activity on the land” (Reasons [232]);

(c) the primary judge was wrong not to apply the test formulated in Spencer v Commonwealth (1907) 5 CLR 418 (Spencer test) to ascertain the economic value of non-exclusive native title rights in circumstances where his Honour had found that the economic value of exclusive native title rights would be the equivalent of the freehold market value of the land, and the freehold market value had been determined in accordance with the Spencer test (Reasons [211], [213]-[214]);

(d) the primary judge was wrong to find that, if the appropriate test for determining the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights was the price at which the native title claim group would have been prepared to surrender their non-exclusive native title rights, the answer would be not at all (Reasons [232]), because:

(i) there was no or no sufficient evidentiary basis to support a finding that the native title claim group would not have been prepared to surrender their non- exclusive native title rights for any price at all, or for not less than a particular price; and

(ii) the primary judge failed to consider the fact that, and terms upon which, the native title claim group had voluntarily surrendered their native title rights over 15 parcels of land in the Town of Timber Creek to the Northern Territory by way of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement on 10 November 2009;

(e) the primary judge was wrong to find that, if the appropriate test for determining the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights was the value to the Northern Territory of acquiring those rights, as the Northern Territory would not then be restricted by the nature of those rights which were surrendered, the answer would be a figure close to the freehold value of the land (Reasons [232]), because there was no or no sufficient evidentiary basis to support a finding that the Northern Territory would have paid, or been prepared to pay, a figure close to the freehold value of the land in order to acquire the non-exclusive native title rights by voluntary surrender or otherwise.

2. A legally correct selection of the percentage of freehold market value to represent the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights would have been in the order of 50 percent, and would have taken into account and given weight to the following considerations:

(a) the Spencer test;

(b) that the non-exclusive native title rights did not include a right to say who could or could not come onto the land in question, or a right to make decisions about how the land could or could not be used;

(c) that the non-exclusive native title rights were not exercisable in such a way as to control who could come onto the land in question;

(d) that the economic value of the non-exclusive native title rights did not depend upon whether there was a valid co-existing interest in the land at the time the compensable act was done because, at all material times, the Northern Territory could have granted valid interests in the land that co-existed with the non-exclusive native title rights;

(e) that, prior to the date of any of the compensable acts, the Northern Territory’s radical title to the land had already been enlarged or expanded commensurately with the extinguishment of a native title right to control access to and use of the land.

56 Ground 1 of the Claim Group’s Notice of Cross Appeal reads as follows:

1. When having regard to the freehold market value of the land in determining compensation for the entitlement under Pt 2 Divs 2-2B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA), being an entitlement on just terms to compensate the native title holders for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of the acts on their native title (ss 51(1), (4), 51A; reasons [229]), the trial Judge erred in not holding that it was appropriate to adopt an amount equivalent to the freehold market value at the time a compensable act occurred, and erred in adopting 80% of that value (reasons [232]), because:

(1) the compensable:

(a) past and intermediate period acts (grants and public works) the subject of order 3 were invalid by the operation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (the RDA);

(b) future acts (grants) the subject of order 9 were invalid by the operation of the NTA (and the criteria for the compensable effects of those acts ought not be materially different) ;

(2) at the time of the compensable acts:

(a) there were no valid interests in relation to the subject land other than the native title interests, save for the bare radical title of the Northern Territory constrained by the statutory provisions at (b) and (c);

(b) the RDA constrained the power of the Northern Territory to deal with and grant interests in the land unless that could be done where the land was held under a non-native title (as too did the NTA in the case of the future acts) ;

(c) the combined effect of the RDA and Crown Lands Acts 1931/1992 (NT) was that the Northern Territory could not deal with or grant interests in the land, being town land for the purposes of those Territory laws, save possibly for the grant of a miscellaneous licence under those laws (which could be done in relation to land held under a Crown lease);

(3) the extinguishment of the native title on validation of the compensable past and intermediate period acts freed and discharged the radical title of the Northern Territory of the burden of the native title and enlarged the title of the Territory as an absolute or beneficial fee simple estate (and for the invalid future acts that occurs on an award of damages in lieu of an injunction).

Introduction

57 The Claim Group is entitled to compensation on just terms for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of the compensable acts on their non-exclusive native title rights and interests (s 51(1) NTA).

58 The non-exclusive native title rights and interests held by the Claim Group before those rights and interests were extinguished by grants made by the Northern Territory were the rights set out in the Joint Statement and extracted at [11] of these reasons for judgment.

59 The Northern Territory argued that the primary judge made a number of errors which meant that his conclusion that the economic value of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests was 80% of the freehold value of the land could not be sustained. It then set out what it said was the proper approach to the assessment of the award of compensation and submitted that this Court should assess the economic value of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests by reference to the evidence before the primary judge.

60 In most, but not in all, significant respects the Commonwealth’s submissions reflected the same approach as the submissions of the Northern Territory.

61 The Commonwealth agreed with the primary judge that, as a matter of logic, the non-exclusive native title rights and interests were to be valued at an amount less than exclusive native title rights and interests. The issue is how much less.

62 The Claim Group contended that the primary judge erred in holding that the economic value of their native title rights and interests was only 80% of the freehold value. They argued that their native title rights and interests were equivalent to freehold and should have been valued at 100% of the freehold value.

63 The arguments of the Northern Territory, the Commonwealth and the Claim Group broadly address three main elements in the primary judge’s reasoning, namely, the extent of the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests, whether in assessing the value of the rights and interests it is open to take into account the value to the acquiring authority, and the effect of the inalienability of the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights on the economic value of those rights.

64 In this section of these reasons for judgment, the parties’ arguments regarding each of these elements are outlined and considered. Then, the Northern Territory’s proposed method for determining the economic value of the Claim Group’s native title rights is considered. Finally, this section raises an alternative approach to the valuation of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests.

The extent of the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests

The submissions of the Parties

65 In the way the reasons of the primary judge are expressed it seems that one factor was of primary importance in his assessment of the value of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests at 80% of the freehold value of the land. That factor was that the rights and interests “in fact enjoyed were in a practical sense exercisable in such a way as to prevent any further activity on the land, subject to existing tenures” ([232]) [emphasis added].

66 The Northern Territory argued that the primary judge was wrong to reach that conclusion. The finding, so it was argued, elevated non-exclusive native title rights and interests to the status of exclusive native title rights and interests. It was wrong to so elevate those rights because the historical grant of pastoral lease PL366 over all the land in question was effective, save in respect of lot 47 affected by act 34, at common law to extinguish the native title right to exclusive possession, and thus to remove the right to control access to the land and to make decisions about the use of the land. Once extinguished, the right to exclusive possession was permanently lost to the Claim Group. As a result, the Claim Group’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests did not permit them to exclude third parties from the land, or to take action to prevent activities on the land by third parties consistent with the existence of those rights. Further, the particular incidents of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests were themselves not exclusive. Thus, the Claim Group did not have a right to camp, to erect shelters on the land, or to hunt and fish to the exclusion of all others. Although some activities might be inconsistent with the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests, there was a broad range of activities which could be undertaken on the land consistently with those rights and interests: Western Australia v Brown [2014] 253 CLR 507, [2014] HCA 8 (Brown) at [46], [55], and [57].

67 The Northern Territory also contended that the primary judge was wrong to find at [228] that the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests “existed as a real impediment to any other grants of interest in the subject allotments” [emphasis added]. The Northern Territory further submitted that the primary judge was wrong to also find at [228] that the Northern Territory needed to acquire those rights before it “could proceed to treat the land or the allotments as part of its radical title to enable it to grant freehold or leasehold interests over those lots”. The Northern Territory argued that at the time when the compensable acts were done, the native title rights and interests were not an impediment to the grant of further interests in the land. At common law, native title rights and interests were exposed to extinguishment by a valid exercise of sovereign power inconsistent with the native title rights and interests. The passing of the RDA did not prevent the grant of interests which were consistent with the remaining non-exclusive native title rights and interests. The RDA did not prevent the grant of estates or interests which were not discriminatory between native title holders and non-native title holders. And, finally, despite the protection afforded by s 10(1) of the RDA, the very purpose of the NTA and VNTA was to retrospectively remove the impediment to the grant of inconsistent estates and interests through the past acts regime. That regime validated those acts and required them to be regarded as having always been valid.

68 The Commonwealth made a similar submission to the Northern Territory regarding the operation of the RDA. It contended that the RDA protects native title from racially discriminatory extinguishment including extinguishment on terms less favourable than those enjoyed by non-native title holders. The RDA does not invalidate a Crown grant which has no extinguishing effect on native title. The historical grant of pastoral lease PL366 extinguished native title rights to control access and the use of the lands at common law. The Northern Territory could have granted valid interests in the lands which did not have any greater extinguishing effect on native title. Therefore, the non-exclusive native title rights and interests should be valued on the basis that the land may be shared with others. The native title rights and interests did not amount to exclusive rights. For instance, the Northern Territory could have validly granted a miscellaneous licence, occupation licence or grazing licence over the land under the Crown lands legislation. These licences would not have had a greater extinguishing effect than the historical pastoral lease.

69 The Claim Group submitted that it is not particularly illuminating to characterise the native title rights and interest as non-exclusive without ascertaining the nature of the rights and interests in question. The rights and interests in this case were in practical terms exclusive. The Claim Group argued that there were no competing rights in the land. No other persons held concurrent rights with the Claim Group. The Claim Group relied upon the observation of the Full Court in Griffiths FC at [128] that the evidence showed that the Claim Group as a community had exclusive possession, use and occupation of the application area.

70 The native title rights and interests involved the full use of the land to live, forage, move about and use its resources. The Claim Group argued that the NTA recognises these rights and the recognition carries with it the right of the Claim Group to utilise the legal system to enforce those rights against others who do not hold the rights.

71 The Claim Group further contended that offences under the Crown lands legislation prohibiting unlawful occupation of the land prevented others from occupying the land.

72 Further, the RDA protected the native title rights from diminution by the grant of competing rights. The RDA also protected the enjoyment by the Claim Group of the use of the land: Western Australia v Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 373; [1995] HCA 47 (Native Title Act Case) at 438. Differential treatment of native title from other forms of title because of its different characteristics and because it derives from a different source is contrary to the RDA. The Claim Group contended that the effect of the RDA and the Crown Lands Act (NT) was that it would be impermissible to value native title less than freehold.

73 Neither the Northern Territory nor the Commonwealth pointed to any non-native title to benchmark the affected native title except freehold.

74 The historical pastoral lease PL366 which included the area of the lands in question, partly extinguished native title. The effect was that the Claim Group’s right to control access to the land was extinguished. However, the question for the purpose of valuation is how the remaining rights held by the Claim Group related to the rights held by others. The loss of the right to control access was not a matter of consequence because no others had rights of access to the lands.

75 The Claim Group submitted that Geita Sebea and Amodu Tijani established that the value of their rights are equivalent to the freehold value of the land.

76 The Claim Group contended that the operation of the Crown Lands Act (NT) limited the Northern Territory’s power to create co-existing rights to the grant of miscellaneous licences and the reservation of the power of resumption in leases granted by the Crown. When comparing the native title rights and interests with freehold it must be remembered that freehold itself is subject to statutory controls, for instance, for planning purposes. Yet it is not suggested that their economic worth is less because of their vulnerability to statutory controls or impairment. Further, the Claim Group could seek relief to prevent the creation of derogating inconsistent rights on the land.

77 South Australia submitted that the extinguishment of the right to control and determine the use of the land and to exclude others from the land effected by the grant of pastoral lease PL366 had more than an insubstantial impact on the rights and interests held and exercisable by the Claim Group.

Consideration

78 There is force in the arguments of the Northern Territory, the Commonwealth and South Australia that the primary judge overvalued the Claim Group's native title rights and interests by holding that those rights and interests “existed as a real impediment to any other grants of interests in the subject allotments, or more generally” [228], were “in a practical sense very substantial” [231], and were “in a practical sense exercisable in such a way as to prevent any further activity on the land, subject to existing tenures” [232].

79 Those assessments were likely to lead to overvaluing the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests because there were significant limits on the extent of those rights and interests which were not reflected in the descriptions used by the primary judge.

80 The grant of pastoral lease PL366 in 1882 extinguished the Claim Group’s exclusive native title. That meant that the right to control access to and make decisions about the lands was lost to the Claim Group and did not revive. It was open to the Northern Territory to make valid grants of rights and interests which were no greater than the rights and interests conveyed by pastoral lease PL366. The remaining non-exclusive native title rights and interests held by the Claim Group did not prevent the Northern Territory from making grants of rights and interests which were not inconsistent with those rights and interests. The scope of the capacity to grant rights and interests consistent with the non-exclusive rights and interests held by the Claim Group was wide.

81 Thus, for instance in Brown the High Court (French CJ, Hayne, Kiefel, Gageler, and Keane JJ) held that Western Australia could grant mineral leases over land in which the Ngarla people held non-exclusive native title rights and interests. The mineral leases allowed for the development of the large Mount Goldsworthy iron ore mine and associated town. At [57] the High Court explained:

[T]he mineral leases in issue in this case did not give the joint venturers a right of exclusive possession. In this respect, the mineral leases were no different from the pastoral leases considered in Wik, the mining leases considered in Ward or the Argyle mining lease also considered in Ward. The mineral leases did not give the joint venturers the right to exclude any and everyone from any and all parts of the land for any reason or no reason. The joint venturers were given more limited rights: to carry out mining and associated works anywhere on the land without interference by others. Those more limited rights were not, and are not, inconsistent with the coexistence of the claimed native title rights and interests over the land.

[Emphasis added.]

82 In this case, the Northern Territory had the statutory power to grant licences to graze stock, licences to occupy the land for up to five years, and miscellaneous licences to take from the land substances or articles, such as timber, belonging to the Crown (ss 107, 108 and 109 Crown Lands Ordinance (NT) respectively). Although the Claim Group could take legal action to enforce their non-exclusive native title rights and interests, they had no power to exclude others from accessing the land or using the land in a way which was consistent with the existence of their native title rights and interests. The value to be ascribed to a resumed interest consists of all future advantages and potentialities, but it is the present value of such advantages or potentialities that fall to be determined: Turner v Minister of Public Instruction (1955-1956) 95 CLR 245; [1956] HCA 7 at 268 per Dixon CJ; Cedars Rapids Manufacturing and Power Company v Lacoste (1914) AC 569 at 576.

83 These limits on the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests mean that it was inaccurate to describe those rights as “a real impediment to the grant of any other grants of interests”, or that they were “exercisable to prevent any further activity on the land”. The description of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests as “very substantial” is imprecise, but does suggest an overestimation of their value in view of the limits described.

84 It is well established that, for the purpose of determining whether native title rights and interests have been extinguished by the grant of inconsistent rights, it is necessary to compare the legal content of the rights rather than the way in which the rights have been exercised. The High Court has rejected the test of practical inconsistency: Brown at [59]. There is no reason why the same approach would not be applied in ascertaining the extent of native title rights and interests for the purpose of compensation claims. The reference by the primary judge to the practical sense in which the native title rights and interest were exercisable is not explained. However, that reference suggests that the primary judge assessed the extent of the native title rights and interests by reference to the way in which rights were exercisable rather than by reference to the legal content of the rights. Such an approach would be an impermissible basis upon which to make the assessment of the extent of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests.

The value to the Northern Territory of acquiring the land

The submissions of the parties

85 The Northern Territory contended that the primary judge at [232] misapprehended the value of the Claim Group’s native title rights and interests by taking into account the value to the Northern Territory of acquiring the rights and interests, rather than looking to the value of the rights to the Claim Group. The primary judge said:

If the appropriate test was to see what was the value to the Territory of acquiring those rights, as the Territory would not then be restricted by the nature of those rights which were surrendered, the answer is that that would be a figure close to the freehold value.

86 That approach was inconsistent with the primary judge’s correct view, expressed earlier in his reasons for judgment, that what is to be assessed is the value to the owner of the rights and interests in question not the value to the acquirer. The primary judge said at [224]:

I accept that compensation on just terms for the extinguishment of non-exclusive native title rights and interests is not properly assessed simply on the basis that, upon the extinguishment of such native title, the Crown acquired radical or freehold title unencumbered by native title so that freehold value is the appropriate measure of compensation.

87 The Commonwealth submitted that the primary judge’s statement at [224] was a correct statement of principle, but his statement at [232] extracted above in [85] of these reasons for judgment was wrong in principle. The value to be assessed is the value of the interest acquired. But, in any event, there was no evidence that the Northern Territory would have paid near the freehold value to acquire the non-exclusive native title rights and interests. The evidence demonstrated what the Northern Territory paid for exclusive native title rights and interests acquired under the 2009 ILUA, but there was no evidence of what the Northern Territory would have paid for non-exclusive rights and interests.