FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kafataris v Davis [2016] FCAFC 134

ORDERS

First Appellant OXFORD NO 1 PTY LTD Second Appellant GROUP INVESTMENT AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Third Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ROWLAND THOMAS Second Respondent WILLIAM JOHN DAVIS Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellants pay the costs of the respondents, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 Mr Con Kafataris seeks to be recognised pursuant to s 15 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) as a co-inventor to a PCT Patent Application lodged in 2013. The PCT Application is annexed to these reasons (Annexure 1). Mr Kafataris seeks other relief flowing from that recognition. Mr Kafataris and related corporate appellants, who played no direct role at trial, were unsuccessful in this claim before the primary judge.

2 The patent in suit relates to an alternative way of playing card games, whereby a player can play a primary game, while at the same time exercising betting options on a secondary or auxiliary or supplementary game, either separately from the primary game or in cooperation with the primary game.

3 The hearings at first instance and on appeal were essentially factual. The main question after various other claims were abandoned was whether Mr Kafataris had contributed to the invention. The primary judge found that he had not. It is from that conclusion and the conclusion that there had been no breach of confidential information by the respondents that he appeals. The central questions on appeal were whether the primary judge had correctly applied accepted principles to the evidence in relation to co-inventorship and whether, on the findings, a duty of confidence arose.

4 For reasons set out below, the primary judge approached all relevant questions correctly and reached findings which were open to him. No applicable error has been demonstrated.

5 The primary judge identified the case as, essentially, being limited to the two issues referred to in [3], namely, first, whether Mr Kafataris should be regarded as an inventor, within s 15 of the Patents Act and, secondly, whether there had been misuse of his confidential information by the respondents, Mr Cory Davis or Mr Rowland Thomas, either directly or through their patent attorney, Mr John Walsh.

6 On 3 April 2012, Mr Davis filed a provision patent application with IP Australia (Provisional Application) for the invention entitled “Baccarat Game with Supplementary Betting Option”. The Provisional Application was prepared by Mr Walsh with Mr Thomas being described as the sole inventor of the invention the subject of the Provisional Application.

7 The Provisional Application was in these terms (annexures omitted):

BACCARAT GAME WITH SUPPLEMENTARY BETTING OPTION

BACKGROUND

The present invention relates to games of chance and more particularly relates to a game feature whereby a player can play a primary game and exercise bet options on a secondary or auxiliary game either separate from the primary game or in co-operation with the primary game. The present invention also relates to an alternative to the known baccarat games which provides increased betting options and increase [sic-increased] actual or perceived opportunities for a win.

The invention also relates to gaming games of chance in which a player is provided with an increased opportunity to bet during a primary game of chance. More particularly the invention relates to improvements in the gaming game of baccarat. The invention relates to providing such game improvement in real or electronic form.

PRIOR ART

[This section sets out the existence of special game features to attract player interest, such as jackpots and features associated with an increased probability of winning, and an extended description of the rules of baccarat. The final paragraph of this section says: ‘Third card selections are known in the prior art but it has hitherto been unknown to provide a baccarat game in which primary and secondary wagers are operating concurrently or sequentially.’]

INVENTION

The present invention provides an alternative to the known baccarat game regimes whereby a player can play a primary game and exercise bet options on a secondary or auxiliary game either separate from the primary game or in co-operation with the primary game. The present invention provides increased betting options and increases actual or perceived opportunities for a win during a primary game of chance. The invention also provides the above features in real (table gaming) or electronic form. The invention further provides a betting regime for allowing a player to bet on a third card which is dealt depending upon the [sic]

In its broadest form the present invention comprises:

A method of playing baccarat comprising the steps of:

a) dealing at least one player a first card;

b) dealing a banker a first card;

c) dealing said at least one player a second card forming a hand with the first player card;

d) dealing said banker a second card forming a hand with the first banker card;

e) prior to dealing the above hands, placing a bet/wager on the first or second of said hands in favour of a player, the banker, a pair or a tie;

f) depending upon the totals of the two cards in the first hands, allowing a player to receive a third card or allowing the banker to receive a third card;

g) prior to receiving the third card, placing a bet/wager on an outcome based on the effect of the player or banker's third card on the outcome; and

h) determining a “wins status” from the outcome of the third card.

According to a preferred embodiment, if the banker draws cards totalling less than 6, the banker will be issued with a third card which he must take. If the Player draws cards totalling less than 6, the player will be issued with a third card which he must take.

According to a preferred embodiment, if the two cards drawn by player total less than 6 and the banker draws two cards totalling 6 or 7, then a third card will be issued to the player. The player must accept this card and the banker must stand on 6 or 7. Prior to the dealing of the third card to the player, an opportunity exists to place a second (double up) bet on either the player or the banker. The third card deal is compulsory once first hand criteria are met.

In another broad form the present invention comprises:

a game of baccarat in which a player is allowed a bet/wager on the effect of a third card dealt after predetermined criteria are met on a first hand dealt to a banker and player.

According to a preferred embodiment the dealing of the third card to the banker or player allows an opportunity to a player to place a first or second bet on the outcome of the effect of the third card whether the third card is dealt to the player or banker. According to one embodiment a player may decide not to be on the first hand but may elect to bet on the second or auxiliary hand including the third card.

In its broadest form the present invention comprises:

A baccarat game in which at least one player and banker are dealt a first hand and contingent upon the outcome of the first hand and subject to the first hand meeting game criteria, a player or banker wagers on a hand which includes a third card dealt to either the banker or player subject to game criteria being met.

According to a preferred embodiment if game criteria based on the first hand are met a compulsory third card is dealt, prior to which a player or banker has the opportunity to bet on the effect of the third card on the second hand.

The present invention provides an alternative to the known prior art and the shortcomings identified. The foregoing and other objects and advantages will appear from the description to follow. In the description reference is made to the accompanying representations, which forms a part hereof, and in which is shown by way of illustration specific embodiments in which the invention may be practiced. These embodiments will be described in sufficient detail to enable those skilled in the art to practice the invention, and it is to be understood that other embodiments may be utilized and that structural changes may be made without departing from the scope of the invention. In the accompanying illustrations, like reference characters designate the same or similar parts throughout the several views. The following detailed description is, therefore, not to be taken in a limiting sense, and the scope of the present invention is best defined by the appended claims.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF DRAWINGS

The invention will now be described in more detail according to a preferred but non-limiting embodiment and with reference to the accompanying illustration.

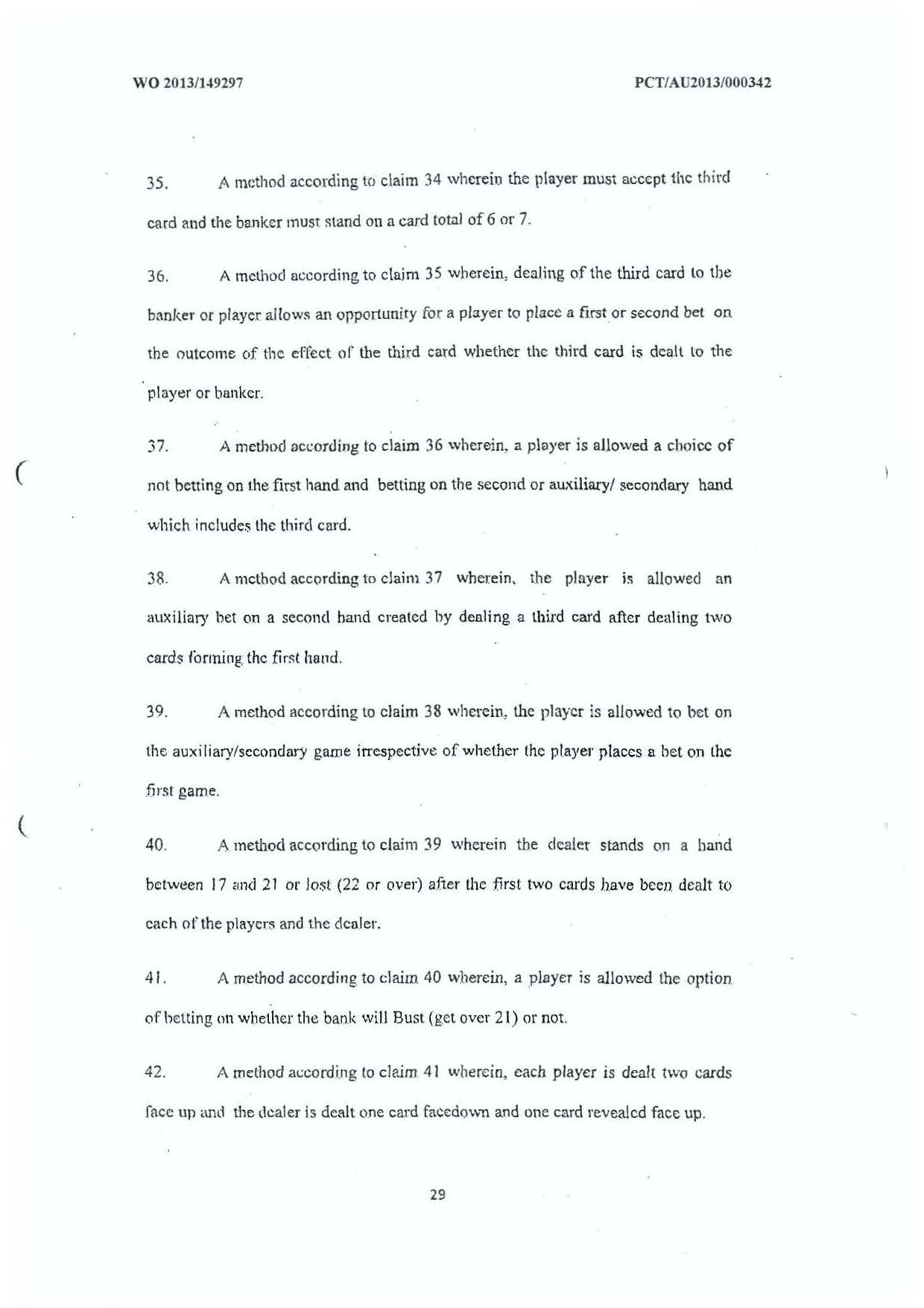

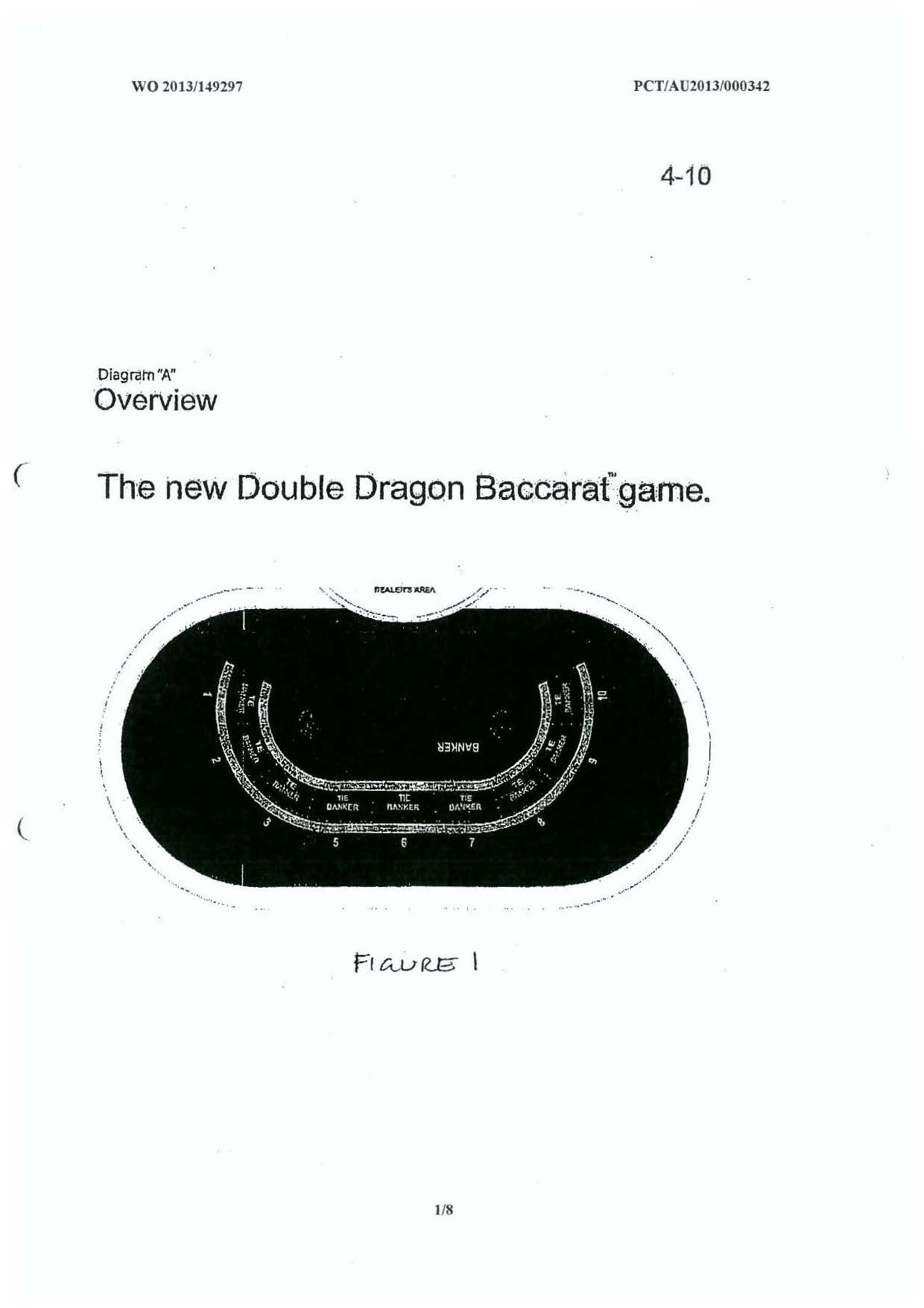

Figure 1 shows a plan view of a BACCARAT table layout according to a preferred embodiment.

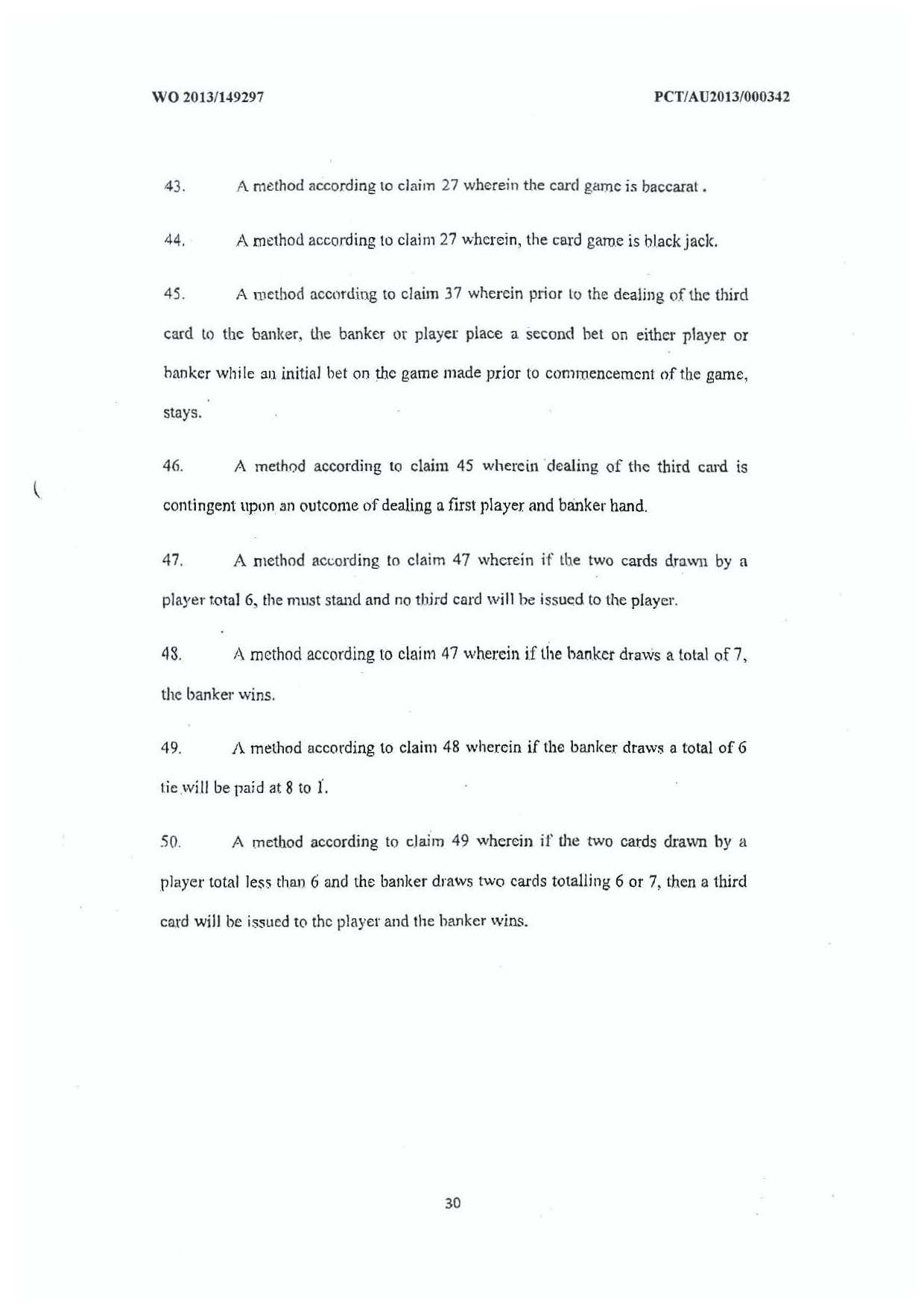

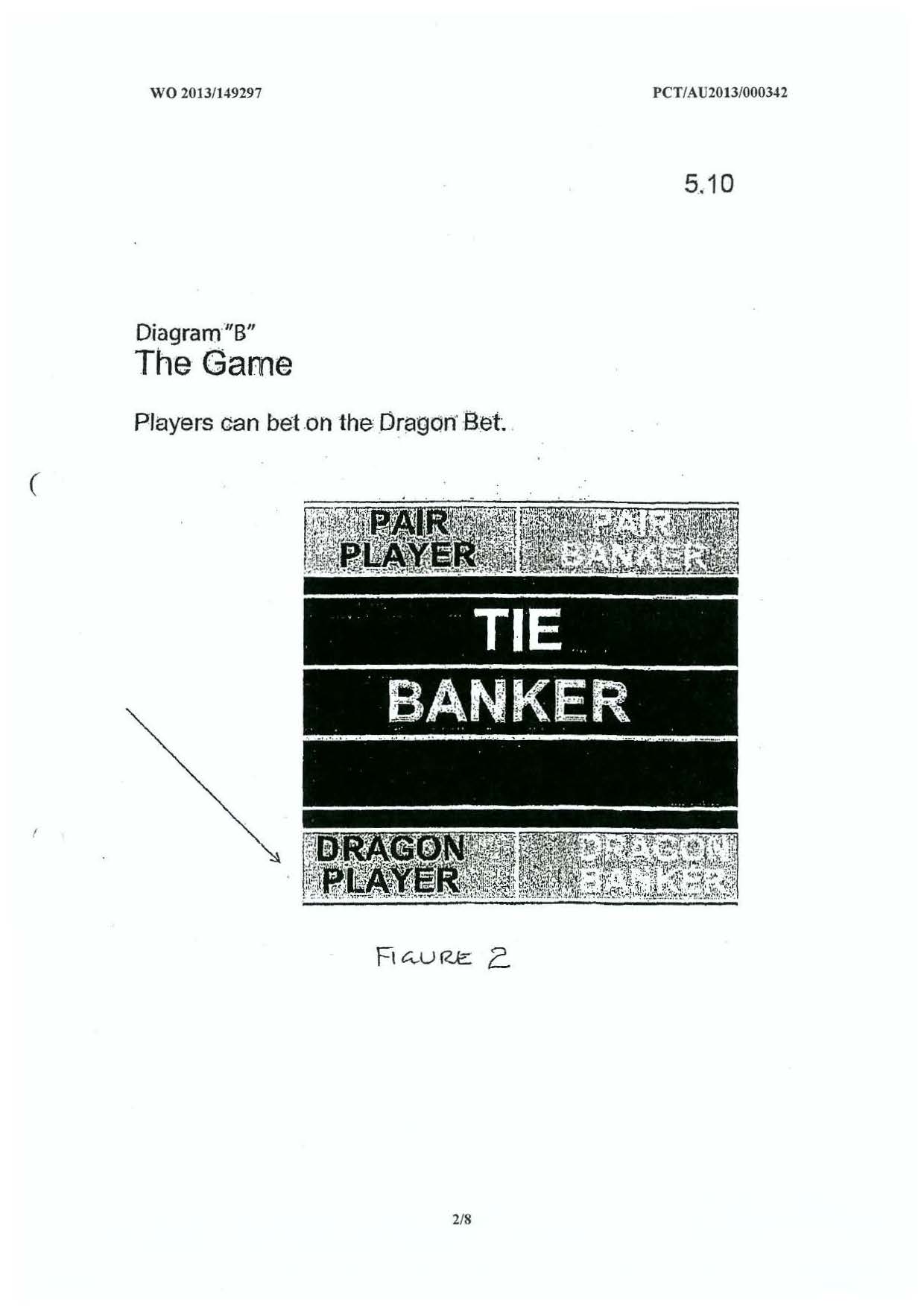

Figure 2 shows a plan view of a baccarat table according to an alternative embodiment.

DETAILED DESCRIPTION

According to one embodiment of the invention a player is dealt the first card, followed by one to the banker. A second card is then dealt to the player followed by second card to the banker. These four cards form the initial hand and first bets can be placed prior to dealing. Bets at this point can be placed on player, banker, tie or pairs according to conventional methodology. Ace counts as one. Tens and all picture cards count as zero as per usual criteria.

If the two cards drawn by either player or banker total 8 or 9, this is called a natural and no further card will be issued on the game. If both player and banker have a total of 9, this is deemed a tie. Bets placed on the tie would be paid at 8 to 1. Bets placed on player or banker are refunded. Bets placed on pairs are forfeited.

If player totals 9 and the banker totals 8, the player wins.

If player totals 8 and the banker totals 9, the banker wins.

If player and the banker total 8, this game is deemed a tie and all bets placed on player or the banker are refunded. IF the 8 is made up of 2 X fours in either or both hands, pairs will be paid at 11 to 1.

If the two cards drawn by the player total 7, the player must stand and no third card will be issued to player. If the banker draws cards totalling less than 6, the banker will be issued with a third card which he must take. The double up draw on the third card is once relevant criteria are satisfied compulsory.

Currently there is no regime to allow betting on an outcome generated by the dealing of the third card. Prior to the dealing of the third card to the banker, an opportunity is provided to a player to place a second bet (irrespective of whether the player has bet on the outcome of the primary game - i.e. dealing of the first two cards) on the outcome of the effect of the third card whether the third card is dealt to the player or banker. Any bets on the initial hand or primary game will stand and can be made independent of the outcome of the secondary betting on the third card or contingent upon the outcome of the betting on the first two cads [sic-cards]. The betting regime can be adjusted as required within the framework of the original bet if made or at least as a consequence of the initial card deal to player or banker.

If the two cards drawn by the player total 6, the player must stand and no third card will be issued to the player. If the banker draws 7, the banker wins. If the banker draws 6, tie will be paid at 8 to 1. The player and the banker bets will be refunded if the tie is paid.

If the two cards drawn by the player total less than 6 and the banker draws two cards totalling 6 or 7, then a third card will be issued to the player. The player must accept this card and the banker must stand on 6 or 7. Prior to the dealing of the third card to the player, an opportunity exists to place a second (double up) bet on either the player or the banker. Initial bets stand.

If the player and the banker draw cards totalling less than 6, both the player and the banker will receive and must accept a third card. Prior to the dealing of these third cards, an opportunity exists to place a second (double up) bet on either the player or the banker. Initial bets stand.

If the player draws two cards of the same denomination (eg 2 x 2,2 x KING, 2 x ACE), then the player pair bets will be paid at 11 to 1, irrespective of the final outcome of the game. If the banker draws to cards of the same denomination (eg 2 x 2,2 x 6,2 x 10), then the banker pair bets will be paid at 11 to 1, irrespective of the final outcome of the game. If both the player and the banker draw two cards of the same denomination, then both the player and the banker pair bets will be paid at 11 to 1, irrespective of the final outcome of the game. Pairs do not affect this issuing of third cards when appropriate. This second bet allows patrons to make a more informed decision for investment in the game.

Figure 1 and 2 show baccarat tables in alternative forms on which the game regimes according to the invention may be played in casino environments.

The above described game play methodology and third card betting regime according to the invention in all its forms, is also adaptable to on line [sic-online] and internet gaming, gaming on electronic hand held devices and on devices such as computers, ipads, iphones and gaming machines. In each case the game rules may be altered to suit regulatory requirements or device capability provided each allows the capacity for a player to wager on a third card separately or in addition to a previously laid wager on a first hand of two cards.. [sic]

It will be recognised by persons skilled in the art that numerous variations and modification may be made to the invention broadly described herein without departing from the overall spirit and scope of the invention.

Dated this 3rd day of APRIL 2012

CORY DAVIS

By His Patent Attorneys

WALSH & ASSOCIATES

8 Following the filing of the Provisional Application, assistance was sought from a mathematician on the topic of calculating playing odds that casinos might adopt for the invention, the subject of the Provisional Application. This was not particularly productive and the respondents were introduced to Mr Kafataris. Mr Kafataris has extensive experience in the wagering and gaming industries, and he is an experienced businessman. It was in this regard that Mr Kafataris was introduced to the respondents.

9 It was common ground that Mr Kafataris and the respondents met on several occasions, but a great deal of what was said and done in these meetings was in dispute. In large measure, the primary judge resolved those disputes and made specific credit findings in relation to the parties and witnesses. But in the end, the content and substance of those exchanges was of little direct relevance in determining whether or not Mr Kafataris had in fact contributed to the invention, a question capable of being determined objectively. Certainly the history does show that, as a result of these meetings, the assistance of Mr Kafataris was sought and obtained. What is also clear is that Mr Kafataris was pressing for a form of commercial relationship which would see him substantially recognised as a contributor and to have financial rewards as a result. These negotiations, however, broke down as the respondents were not willing to agree to his terms. Much of the case for Mr Kafataris as originally, but not ultimately, crafted related to the claimed legal and equitable consequences following from the contributions that he contended he made during these unsuccessful negotiations. There were some relatively modest changes, his Honour found, in the ultimate PCT Application, which claimed priority from the Provisional Application.

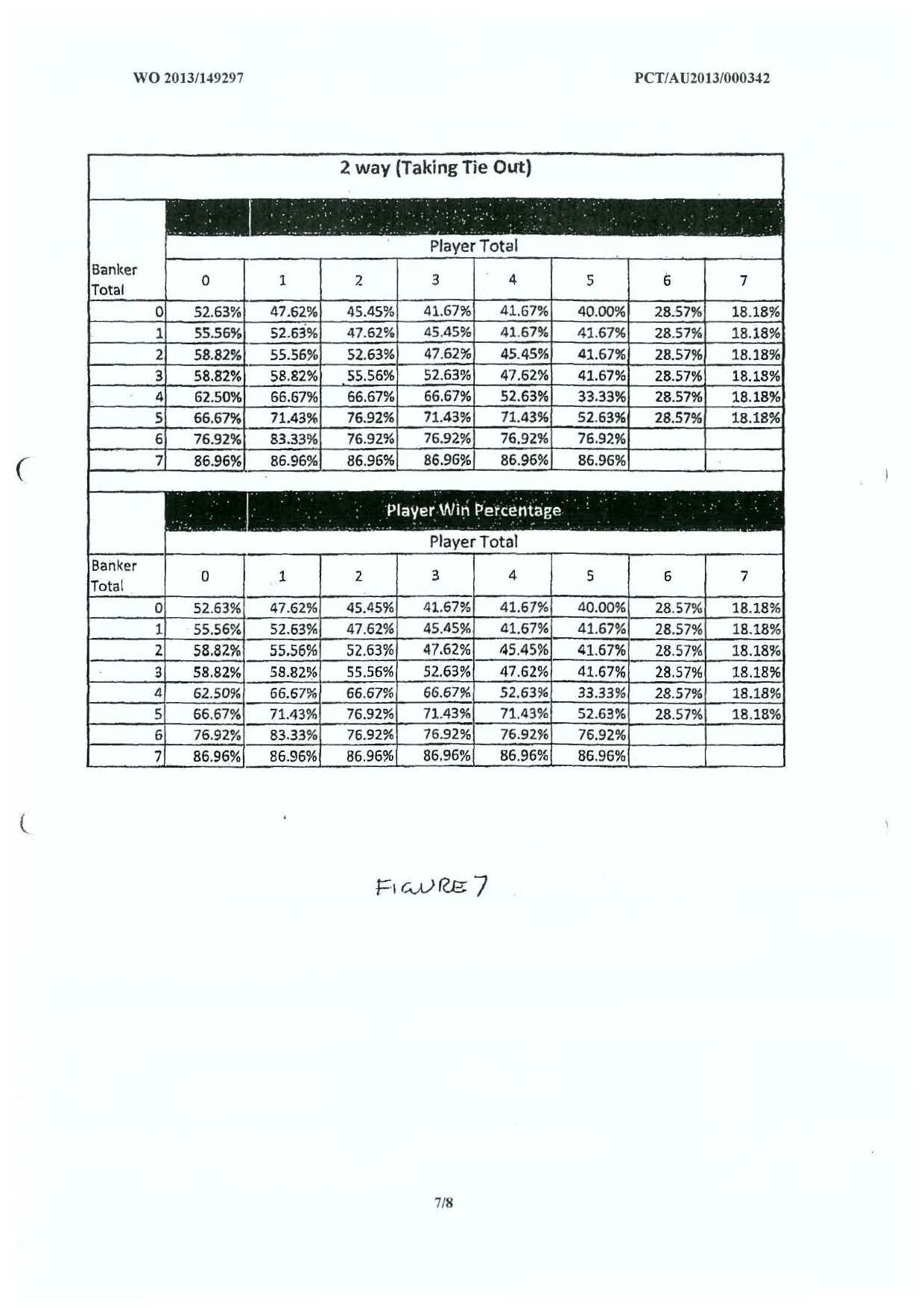

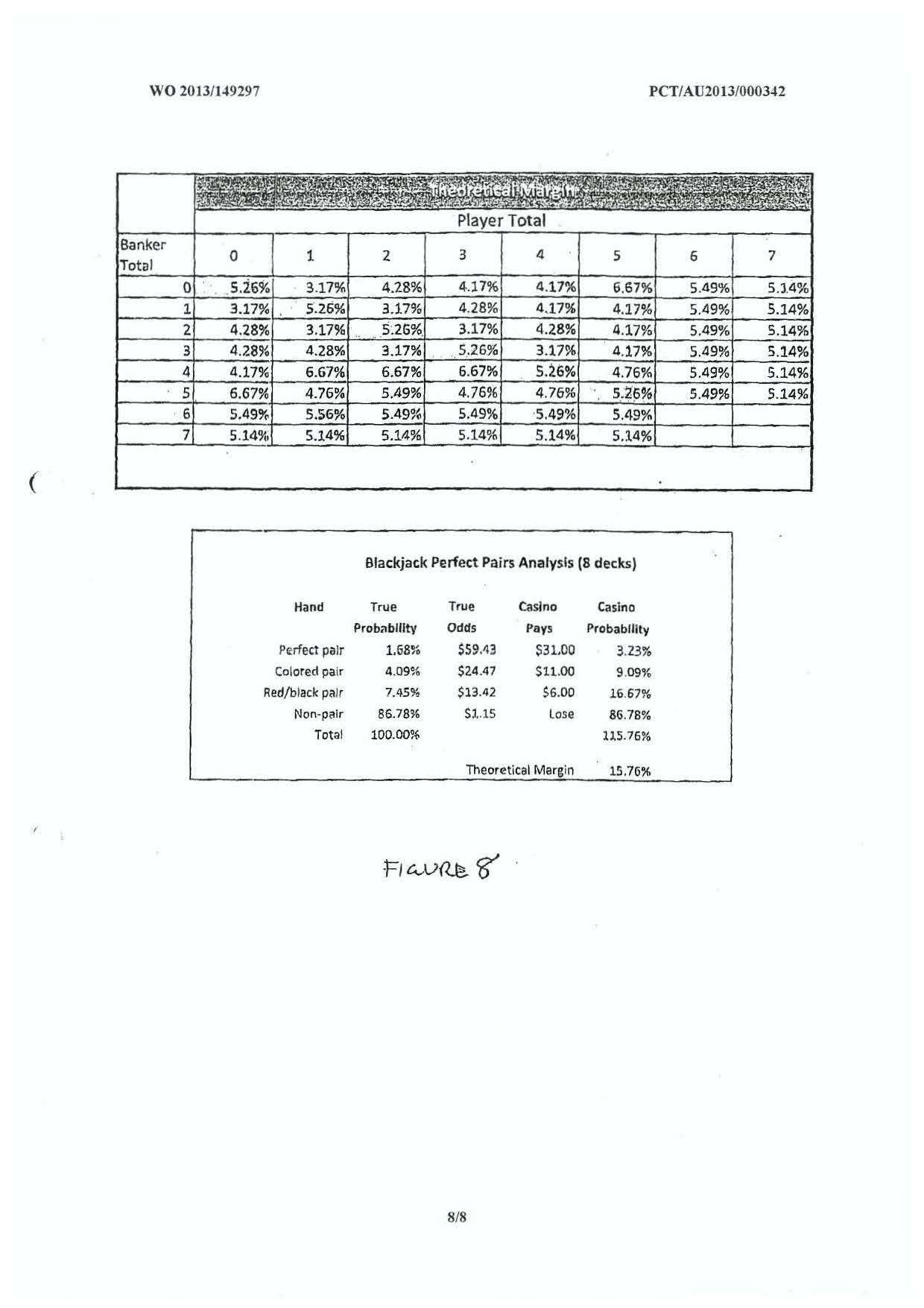

10 Many matters were excluded from the debate at trial, not least of which was the question of whether a supplementary betting option for any card game can be an invention. (That question may be part of the examination process and any opposition hearing or in any future infringement action.) There was no challenge to the description of the invention in the PCT Application and the primary judge concluded (at [56]) that when the PCT Application was considered as a whole, the invention as described is a method of wagering, whereby a player is able to exercise a betting option on a second or auxiliary game, either separate from the primary game or in cooperation with the primary game. It is also made abundantly plain in the PCT Application that although the invention is described with reference to baccarat and blackjack, it is asserted that it can be adapted to alternative card games, again, however, without further examples. His Honour said (at [56]) that when one considers the claims which are set out in some detail in the PCT Application, it is even clearer that what is being described, albeit by references as examples to baccarat and blackjack, is “a method of wagering on a card game in which a player has a secondary bet or wage option.”

11 The primary judge noted that s 15 and s 16 of the Patents Act relevantly provide as follows:

15 Who may be granted a patent?

(1) Subject to this Act, a patent for an invention may only be granted to a person who:

(a) is the inventor; or

(b) would, on the grant of a patent for the invention, be entitled to have the patent assigned to the person; or

…

…

16 Co-ownership of patents

(1) Subject to any agreement to the contrary, where there are 2 or more patentees:

(a) each of them is entitled to an equal undivided share in the patent; and

(b) each of them is entitled to exercise the exclusive rights given by the patent for his or her own benefit without accounting to the others; and

(c) none of them can grant a licence under the patent, or assign an interest in it, without the consent of the others.

…

12 His Honour noted authority suggesting that if the PCT Application could not be said to be fairly based on, or reasonably disclosed by, the Provisional Application, that might suggest that Mr Kafataris did make such a contribution. His Honour stressed (at [77]): “However more importantly as I have already said it is crucial to analyse previously what steps the [Mr Kafataris] took.”

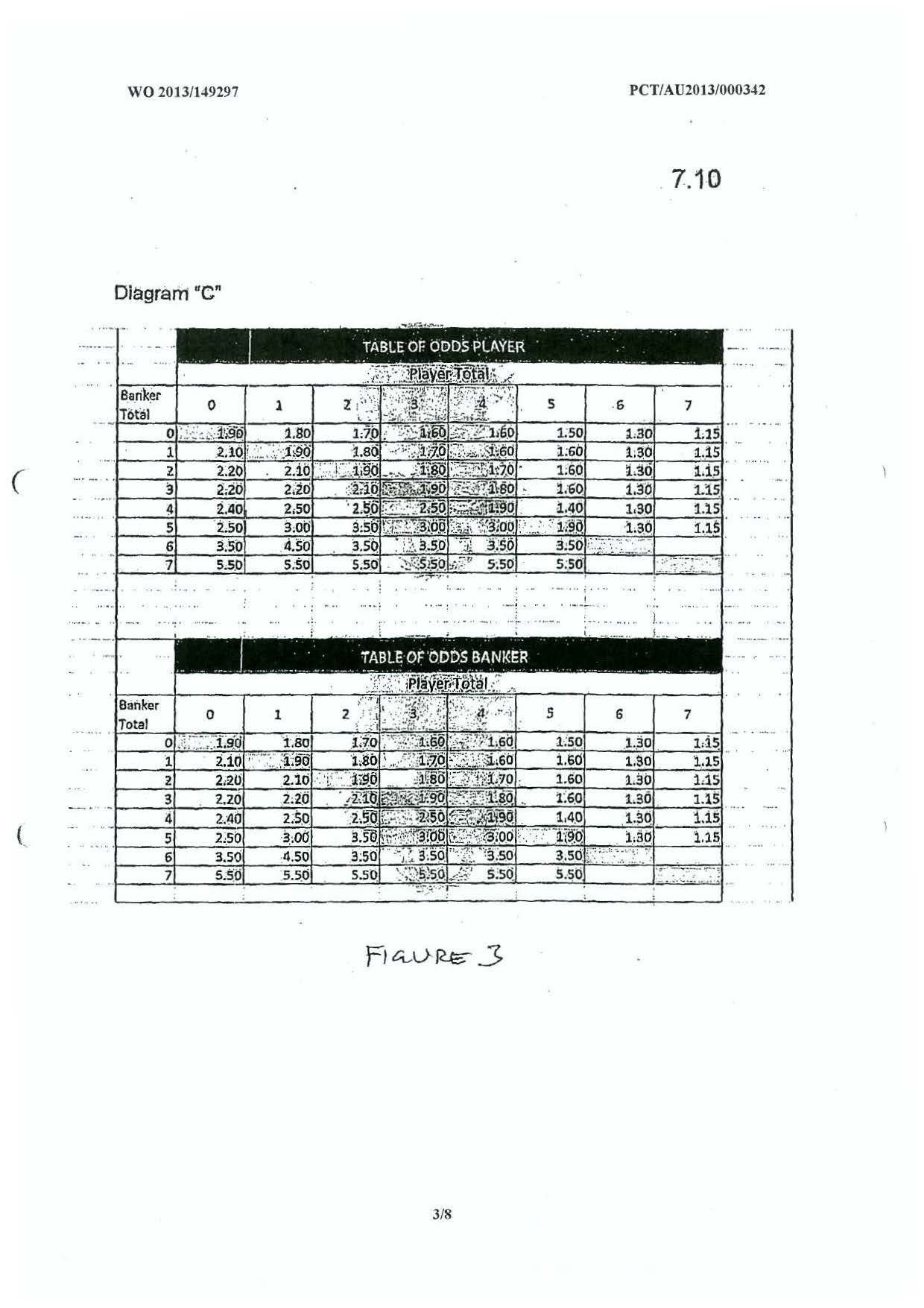

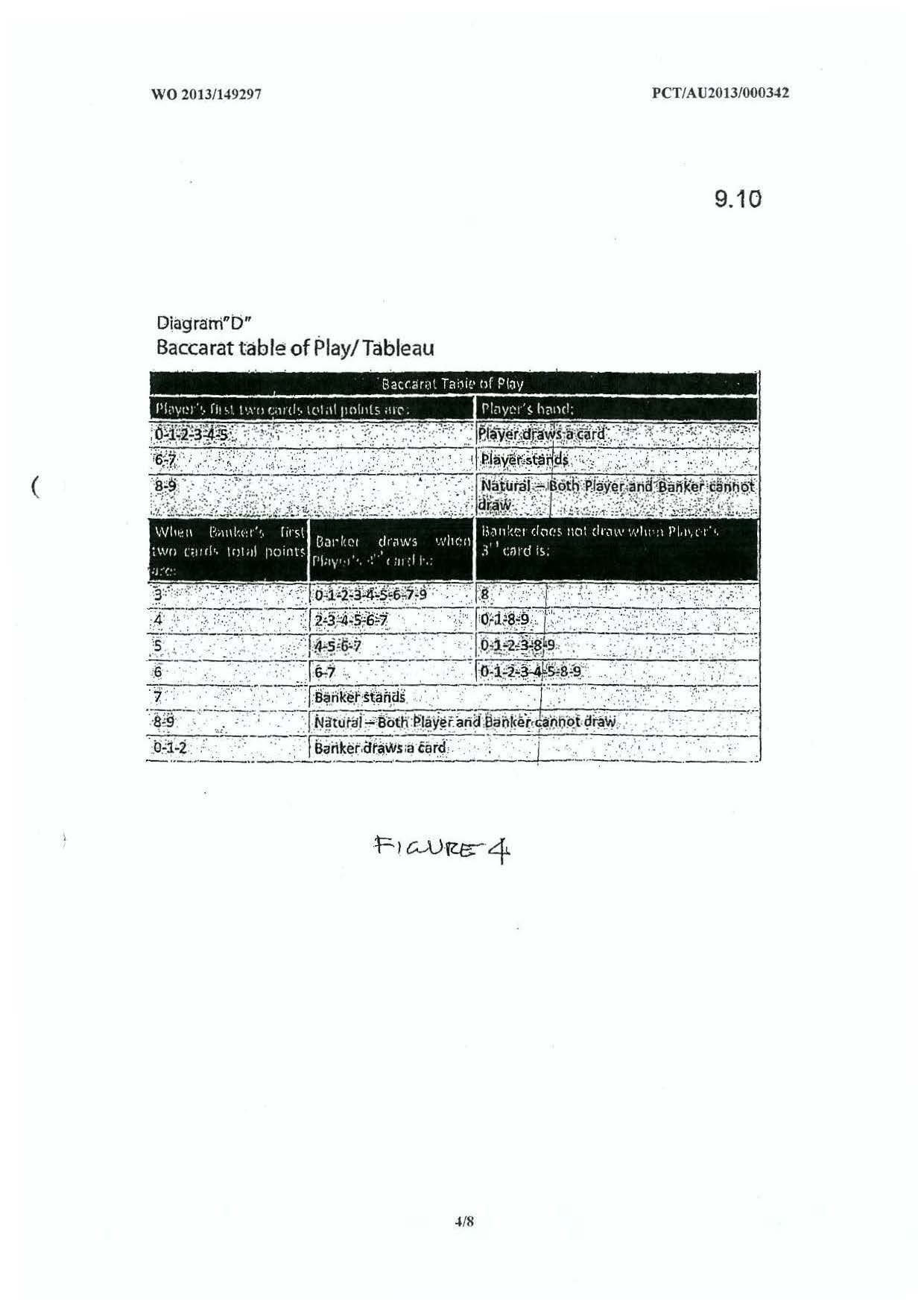

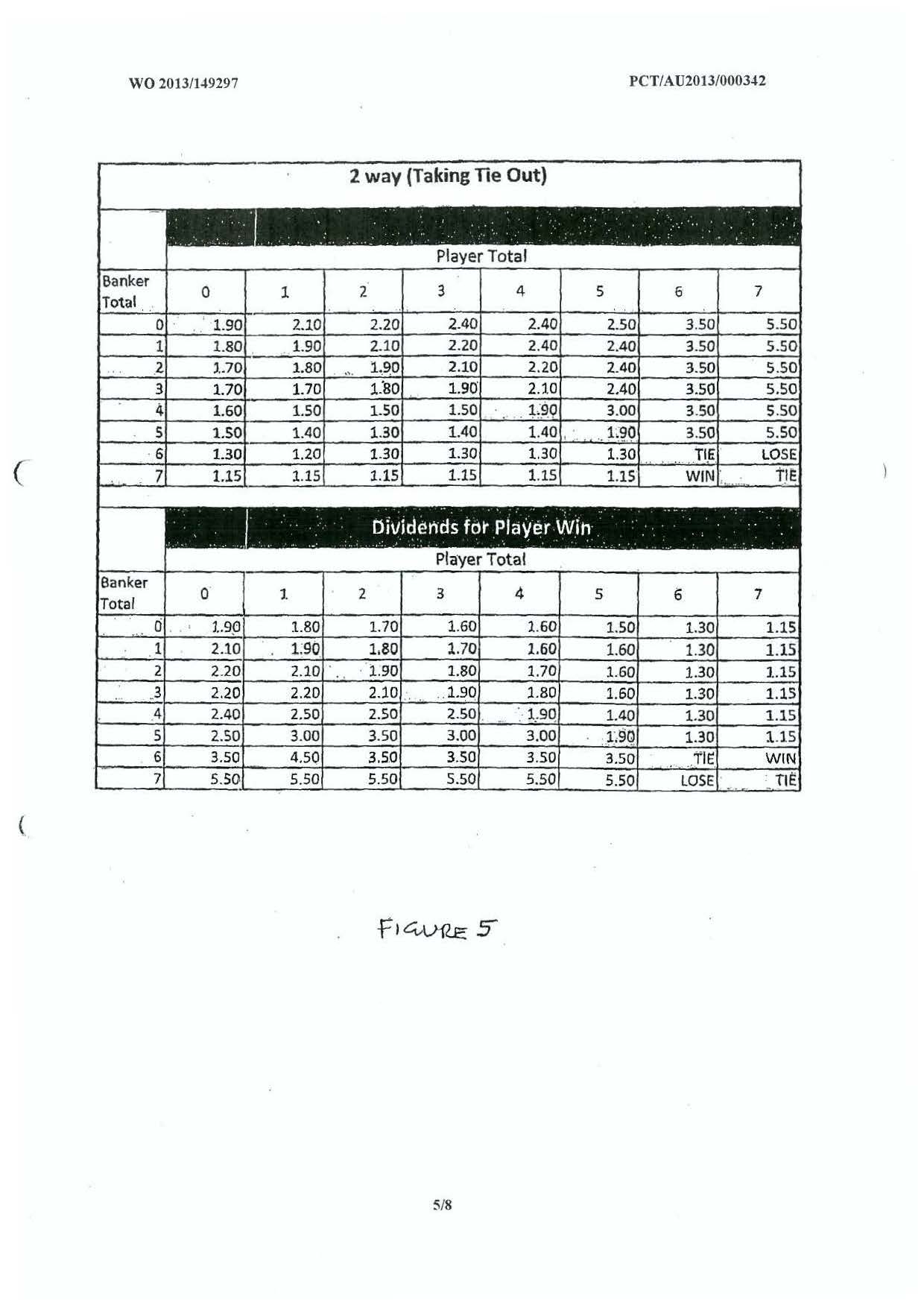

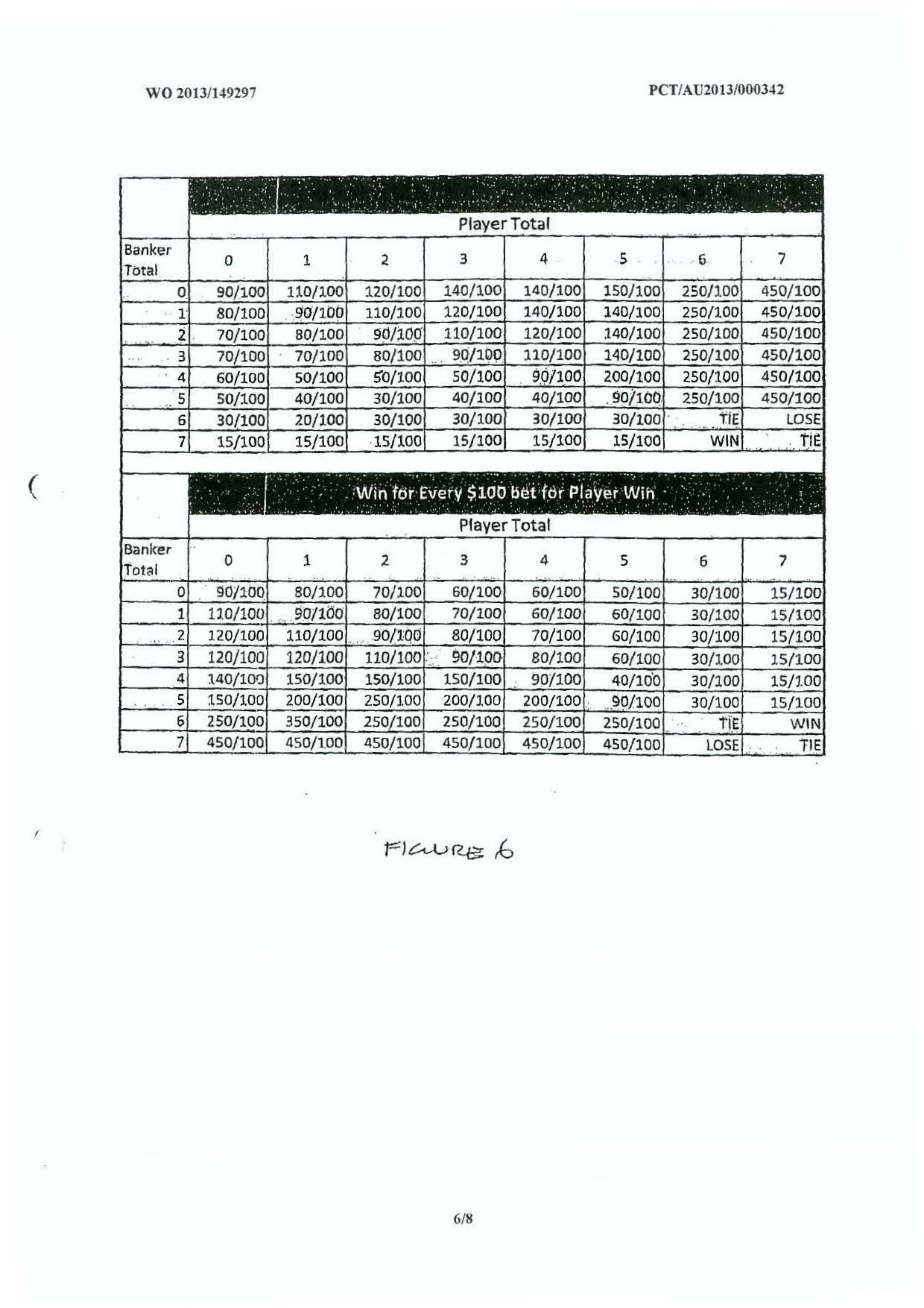

13 The primary judge then described the games of baccarat and blackjack, emphasising in particular the supplementary betting option. In the case of baccarat, he described it in these terms (at [103]-[104]):

103 The supplementary betting opportunity adds an extra element to the rules described previously. It only applies when there is a requirement for a third card for one or both hands. At that point, certain information is available to any participant (namely, the four cards consisting of the two cards dealt to the player hand and the two cards dealt to the banker hand). However, whether a third card is drawn is prescribed by the rules of punto banco baccarat.

104 The supplementary betting opportunity allows both participants and third parties (i.e. persons who did not place an initial bet before the cards were dealt) to place a bet, at certain odds that are not static but depend on the cards already revealed, on what the outcome of the game will be. It is anticipated that those odds would be displayed on a screen to enable participants to decide whether to take the supplementary betting opportunity.

And, in relation to blackjack, his Honour described it in these terms (at [113]-[116]):

113 In blackjack, the supplementary betting option is not available on the outcome of the game, as was the case for baccarat. That is because in blackjack the player could place a large bet on the dealer winning and then choose to simply draw additional cards until they go bust. The bet is placed, not on the outcome of the game itself, but on whether the dealer will go bust. This point was heavily relied on by counsel for the plaintiff to draw a distinction between the two games.

114 In the PCT application at [0060], it is suggested that each player is dealt an initial hand of two cards visible to the people playing on it, and often to any other players. Later in the same paragraph it is suggested that the players' initial cards may be dealt face-up or face-down.

115 The blackjack dealer bet rules provided to Mr Walsh on 18 March and Mr Davis on 20 March (Exhibit P2, Tab 20) suggest that the wager is placed on whether the dealer will bust or not at the point when only the dealer's card is visible. The odds at page 103 are only calculated in relation to that face-up card. That would seem to suggest that it is only feasible to place a supplementary bet when the player cards are face down.

116 It would seem to follow that that the side bet is available at an early point in the game, rather than being available only once the dealer is required by the rules of the game to draw an additional card or cards.

14 His Honour considered the credibility of key witnesses, notably, Mr Kafataris, Mr Thomas, Mr Walsh and Mr Davis. He accepted that Mr Kafataris was largely a truthful witness, although he had exaggerated the extent of his analyses, especially on odds, and was unable to clearly satisfy his Honour as to what exactly he had done in devising various odds or in consideration of the game of blackjack. His Honour noted (at [123]):

He of course did not conceptualise in any respect the idea of a supplementary betting option, and his activities as explained in detail later were entirely devoted, it seems to me, to identifying whether and if so when a supplementary bet could be placed within the existing rules of blackjack.

15 The primary judge was, however, quite critical of both Mr Thomas and Mr Walsh in terms of the evidence they gave. Specifically, his Honour rejected any suggestion, contrary to the evidence of Mr Thomas, that he had ever thought of the supplementary bet being available to any other card game prior to Mr Kafataris raising it. His Honour said (at [126]): “I regard his assertion that he intended prior to the filing of the provisional application that a person could make such a bet in all table card games as opportunistic and untruthful.”

16 In relation to Mr Walsh, his Honour observed that Mr Walsh was in the difficult position of fulfilling the role of both lay and expert witness. His Honour found his evidence somewhat unsatisfactory and contrived. He concluded that he was advocating a position.

17 His Honour found that baccarat was the only card game discussed between Mr Walsh and Mr Thomas in early 2012 for several reasons (at [149]). First, Mr Walsh had no note to the contrary. Secondly, Mr Thomas had no contemporaneous note suggesting he in fact raised card games other than baccarat. Thirdly, all of the documentation pointed only to baccarat. Fourthly, the terms of the Provisional Application made it abundantly clear to him that only baccarat was the subject of consideration.

18 The primary judge concluded (at [152]) that in drafting the Provisional Application, Mr Walsh approached it as an “ambit claim”, using general terminology so as to allow his clients latitude to argue ultimately that any additional innovation that might be included in the PCT Application could be said to be fairly based on the Provisional Application. That said, his Honour stressed that he was satisfied that Mr Walsh had no other specific examples in his head beyond baccarat.

19 Although Mr Walsh insisted that baccarat was used at the time of the drafting of the Provisional Application simply to refer to the preferred embodiment, his Honour said (at [154]) that in reality it was the only embodiment identified. At [156], his Honour said:

Mr Walsh's assertion that the provisional application was expressly intended to include blackjack is simply fanciful. I do not consider the language can support that. He had no particular expertise in card games himself and his client Mr Thomas was exclusively focussed on baccarat to the exclusion of anything else. In the circumstances, and given his instructions, he had no basis whatsoever for imagining that the invention as a matter of practical reality could at that time apply to any other card game. That however does not, as is clear from the PCT application, affect the very nature of the novelty identified. There is nothing new about baccarat or blackjack, but what was new was the supplementary betting option and I consider he did have that firmly in his mind at all times. That was the invention he was purporting to describe.

20 The primary judge then turned to consider in detail the involvement of Mr Kafataris.

21 It was significant, according to his Honour (at [170]), that in calculating the two sets of odds (which were described in the pleadings as the First and Second Kafataris Additions respectively), “despite some grandiose claims to the contrary”, Mr Kafataris very largely accessed the website “The Wizard of Odds”, which provides for both the game of baccarat, and for that matter blackjack, the probability of certain events occurring, and calculated a return based on certain probabilities. Having had that access, Mr Kafataris performed relatively straightforward mathematical exercises by either adding in a 5% margin for the casino, about which he made an assumption, and redoing the calculations in the event that the return provided an odd amount, for example, $2.25.

22 The primary judge concluded (at [171]) that while Mr Kafataris may have spent many hours over a number of days considering the odds and undertaking his calculations, insofar as the odds were concerned, he very largely, if not entirely, relied upon publicly available information from the The Wizard of Odds website (see [170]-[171]).

23 The primary judge accepted (at [182]) that the possibility of usage of the system with blackjack was raised by Mr Kafataris. His Honour undoubtedly found (at [182]) that Mr Thomas had never even considered blackjack, let alone was he in a position to assert one way or the other that his invention would apply to it.

24 His Honour observed (at [200]) that by early 2013 Mr Walsh must have appreciated that Mr Kafataris had been asking questions and raising blackjack in the context of the invention. It follows that Mr Walsh must have thought about it by that time as well. His Honour rejected Mr Walsh’s evidence that he told Mr Kafataris that blackjack was another embodiment of the invention. His Honour concluded (at [200]) that there was no doubt that Mr Kafataris clearly requested the inclusion of blackjack in the PCT Application.

25 Mr Kafataris said that over the period between January and March 2013 he “developed a side bet specific to the card game known as blackjack” and that he set out the “specifications of this game” in a document entitled “Blackjack Dealer Bet Games Rules”. His Honour accepted this was so (at [206]), but said (at [207]) that it was clear from the email from Mr Kafataris to Mr Davis of 14 March 2013 that he substantially created the Blackjack Dealer Bet Game Rules from the format of the baccarat game rules created by Mr Thomas. In addition, his Honour was satisfied that Mr Kafataris had to make himself familiar with the rules of the game for the purpose of identifying when, if at all, a supplementary or subsidiary betting opportunity might arise.

26 In his Honour’s discussion, he reiterated that Mr Kafataris accepted that Mr Thomas created something novel in identifying the possibility of a supplementary betting option within the game of baccarat, but contended that Mr Kafataris also made a material contribution by identifying a supplementary betting operation within the game of blackjack. His Honour did not agree (at [226]). His Honour’s assessment of all of the facts discussed in detail in his reasons was that the parties were working closely together in order to forge an ongoing commercial relationship based on the patent application. That collaboration may be an indicia of joint invention, but that indicia could not “trump in and of itself” the need for a court to distinguish between a qualitative, rather than a merely quantitative contribution to the invention as a matter of fact. His Honour (at [227]) described contribution as something that has to be material, tangible or qualitative contribution to the invention. There had to be some contribution to the concept, design or perhaps method. It must be seen objectively as indeed part of the invention (at [227]).

27 The approach his Honour then took was to determine what the invention was in the Provisional Application in fact before resolving the question of whether what was done by Mr Kafataris could constitute a contribution as so described. His Honour said (at [229]) that the PCT Application was an obvious guide, setting up a method of wagering whereby a supplementary betting option could be exploited. While Mr Thomas created the concept of a supplementary wagering opportunity in the context of baccarat, that opportunity was constrained entirely by the rules of that game. His Honour expressly found (at [231]) that Mr Thomas never did advert specifically or at all to the possibility of the opportunity extending to other games.

28 Notwithstanding this, his Honour concluded (at [232]) that the invention or the novelty, which Mr Thomas had identified and which Mr Walsh, on the basis of his instructions, was attempting as broadly as he could to articulate in the Provisional Application, was a supplementary betting or wagering opportunity within the rules and hence the constraints of an existing and very well-known card game, being baccarat. That, therefore, was the inventive step, namely, to conceive of the possibility of such an opportunity and then to undertake by luck, hard work or otherwise the identification of an appropriate point within the rules of baccarat when such an opportunity could be exploited. Mr Thomas addressed a problem and came up with the solution to use familiar terminology so as to conceive of an idea of doing a new thing (that is, exploiting an additional betting opportunity) or perhaps put another way, a new idea of achieving a previously known goal.

29 His Honour said (at [233]) the mere fact that only one opportunity was detected by Mr Thomas within the rules of baccarat did not affect the notion of novelty. The contribution of Mr Kafataris to the concept or idea of a supplementary or subsidiary betting opportunity by Mr Thomas was to approach the rules of blackjack in order to identify whether a similar opportunity arose. Mr Kafataris knew, as a result of the work undertaken by Mr Thomas, that in the baccarat context, the opportunity arose when the dealer or banker was obliged to take a third card. With this information, he then undoubtedly reviewed the rules of blackjack to identify a similar, if not identical opportunity, namely the opportunity of the dealer or banker being placed in the position where they were required by the rules of the relevant game to take a third card. His Honour expressly concluded (at [235]) that the analysis by Mr Kafataris, as it were, did not involve any inventive step at all and should not be seen as a material contribution to the invention. He adopted the language of Justice Aickin in Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Limited (1980) 144 CLR 253 (at 293), where his Honour said “the opening of a safe is easy when the combination has already been provided”. It was the identification of the possibility of a supplementary betting option identified by Mr Thomas which was necessary before Mr Kafataris could identify a similar opportunity in blackjack. “Mr Kafataris was only able to identify a similar opportunity in blackjack after the idea of a supplementary betting opportunity had already been identified in baccarat.” At [236], his Honour said:

I do not consider Mr Kafataris' activity to involve a material contribution or to have brought something new or different to the invention. It does not represent a departure from the idea of the invention, but rather what it does is simply to provide an additional opportunity for a supplementary bet.

30 The “broadening” concept for which Mr Kafataris argued as being the contribution was rejected by his Honour (at [237]). His Honour found that Mr Kafataris was able to identify the opportunity in blackjack and, therefore, enable Mr Walsh to draft the PCT Application more broadly and amplify or elaborate on the crux of the invention with the benefit of a second example. The contribution could not properly be regarded as material to the final form of the invention as described in the PCT Application. It did not bring about a change to the invention, rather it merely provided another example (at [237]).

31 His Honour’s reasoning turned on the conclusion that the supplementary betting option was the crux of the invention, albeit that only one example could be given at the time of the Provisional Application. All Mr Kafataris did was to provide another example in which the invention could be used. He identified a development along the same line of thought which constituted or underlay the original invention. Rather than being an inventor, he was a competent technician able to solve a problem on the basis of the idea by Mr Thomas and the rules constraining the playing of the game of blackjack (at [239]-[240]).

32 His Honour also rejected that the parties were in a fiduciary relationship (at [245]), and rejected the confidential information case in the remaining passages of his reasons.

33 The amended notice of appeal, while leading to arguments that challenge the process of reasoning of the primary judge, in themselves purely raise issues of fact. The grounds and argument advanced for Mr Kafataris focus, amongst other things, on the clear finding of the primary judge that the possibility of usage of the game with blackjack had never occurred to Mr Thomas at the time of the invention, and that blackjack was included in the PCT Application is a result of the work of Mr Kafataris in blackjack as conveyed to the respondents.

34 In the grounds of appeal, Mr Kafataris contends that he should have been found to have made a material contribution to the invention described and claimed in the PCT Application when he identified a supplementary betting option within the game of blackjack. In substance, the particulars supporting that contention are that:

(a) Mr Thomas only contemplated baccarat.

(b) the contribution made by Mr Thomas was reflected in the language of the Provisional Application prepared by Mr Walsh.

(c) having concluded that:

(i) baccarat was the only card game crossing the mind of Mr Thomas at the time of filing the Provisional Application;

(ii) Mr Thomas never identified a supplementary betting option for blackjack;

(iii) Mr Thomas would not have been able to make the statement prior to Mr Kafataris raising the possibility in relation to blackjack that the supplementary betting option was available for “all casino table card games” unless he was being boastful or dishonest;

(iv) baccarat was the only card game discussed between Mr Thomas and Mr Walsh;

(v) baccarat was not merely a preferred embodiment, but, rather, was the only embodiment in which a secondary or auxiliary betting opportunity was identified;

(vi) Mr Walsh had no basis for imagining the invention could apply to any other card game; and

(vii) Mr Walsh drafted the “Background” to the Provisional Application in order to leave open only the “possibility that the patent may have a wider application than merely baccarat, purely in a theoretical sense”, and, therefore,

the primary judge erred in concluding that Mr Thomas had prior to the contribution of Mr Kafataris made an invention of a general method of wagering whereby a supplementary betting option could be exploited.

35 Rather, and as corollaries to the foregoing, it is also contended in the amended notice of appeal that:

(d) The primary judge ought to have found that the invention as described and claimed in the PCT Application involved:

(i) the supplementary betting option in relation to baccarat identified by Mr Thomas, as set out in the Provisional Application;

(ii) the supplementary betting option in relation to blackjack identified by Mr Kafataris, as described and claimed in the PCT Application;

(iii) the generalisation of a supplementary betting option to all casino table card games, which generalisation was made possible by the identification of the supplementary betting option in relation to blackjack.

(e) The primary judge, having:

(i) made the correct factual findings summarised in paragraphs 2(c)(i) to 2(c)(vii) above; and

(ii) found that the invention which Mr Thomas had identified was a supplementary betting option within the rules and hence the constraints of baccarat (at [232]);

erred in finding (including at [226], [235], [236], [237], [238]) that Mr Kafataris did not make a material contribution to the invention as described and claimed in the PCT Application when he identified a supplementary betting option within the game of blackjack.

(f) The primary judge erred in finding (at [237]) that it was not a material contribution that the identification of the supplementary betting opportunity in a second card game (blackjack) led to the generalisation of a method of playing baccarat in the Provisional Application to a wagering system applicable to all card games in the PCT Application.

(g) The primary judge erred in finding that the nature of Mr Kafataris' identification of the particular event within the game of blackjack which provided a suitable supplementary betting opportunity was irrelevant (at [238]).

(h) The primary judge ought to have found that the nature of the Mr Kafataris' identification of the particular event within the game of blackjack which provided a suitable supplementary betting opportunity was relevant to the question of whether Mr Kafataris had made a material contribution to the invention described and claimed in the PCT Application.

(i) The primary judge ought to have found that Mr Kafataris made a material contribution to the invention as described and claimed in the PCT Application when Mr Kafataris identified a supplementary betting option within the game of blackjack.

36 The grounds of appeal also contend that the primary judge ought to have found that the contribution of Mr Thomas was limited only to baccarat, and contend that the primary judge erred in using the notion of inventive step and novelty to identify the respective contributions by Mr Thomas and Mr Kafataris.

37 The grounds of appeal also challenge the conclusion on confidential information. The essential argument is that the consent of Mr Kafataris to the inclusion of confidential information in relation to blackjack in the PCT Application should be understood as being on the condition that there would be some commercial arrangement between the parties as to exploitation of the invention in the PCT Application, but not otherwise.

38 The respondents rely upon a notice of contention which essentially raises two points. The first is that as the primary judge should have found that Mr Kafataris did not make a material contribution to the invention. The second is that in light of such a finding, the claim for breach of confidential information must fail. In part they rely on a concession made at trial essentially to this effect. Further, they say that as any claim against Mr Davis had been abandoned, the claim against him should have been (on that ground) dismissed with costs.

39 The appellants focus on the words appearing in the Provisional Application set out above (at [7]) and, in particular, that a game of baccarat comprises the following steps:

a) dealing at least one player a first card;

b) dealing a banker a first card;

c) dealing said at least one player a second card forming a hand with the first player card;

d) dealing said banker a second card forming a hand with the first banker card;

e) prior to dealing the above hands, placing a bet/wager on the first or second of said hands in favour of a player, the banker, a pair or a tie;

f) depending upon the totals of the two cards in the first hands, allowing a player to receive a third card or allowing the banker to receive a third card;

g) prior to receiving the third card, placing a bet/wager on an outcome based on the effect of the player or banker's third card on the outcome; and

h) determining a “wins status” from the outcome of the third card.

40 As noted, the steps asserted in (a)-(f) relate to the existing rules of baccarat, the invention asserted in the Provisional Application related specifically to steps (g)-(h). These steps are described by the appellants as being the Third Card Baccarat Bet.

41 The appellants contend that the PCT Application filed on 3 April 2013 by Mr Davis entitled “Card Game with Supplementary Betting Option”, contained a “significantly broader disclosure” than the Provisional Application and included blackjack in both the specification and the claims. The appellants argue that the appeal should be allowed because Mr Kafataris ought to have been regarded as a co-inventor of the invention set out in the PCT Application because:

(a) his Honour answered the relevant factual question by explicitly finding that Mr Thomas’ invention was confined to baccarat. Accordingly, there was no basis for his Honour to conclude, as he did, that Mr Thomas’ invention extended more broadly. Even if regard is had to the Provisional Application, the disclosure in that document also indicates that Mr Thomas’ invention was confined to baccarat;

(b) the invention of the PCT Application involved:

(i) the generalisation of a supplementary betting opportunity to all casino table card games;

(ii) the Third Card Baccarat Bet identified by Mr Thomas; and

(iii) the supplementary betting opportunity in relation to blackjack identified by Mr Kafataris; and

as such, Mr Kafataris made a material contribution to both (i) and (iii). Even if the invention prior to Mr Kafataris’ involvement is characterised as being a supplementary betting opportunity of general application, he still made a material contribution to the invention of the PCT Application in that he was responsible for its embodiment in relation to blackjack; and

(c) further, or in the alternative, the primary judge should have concluded that there was a breach of confidence for the reasons set out in the notice of appeal.

42 There is a suggestion the primary judge approached the issue by reference to the wrong legal principles. His Honour and the parties accept the appropriateness of application of the following statement of the Full Court (Finn, Bennett and Greenwood JJ) in Polwood Pty Ltd v Foxworth Pty Ltd (2008) 165 FCR 527 (at [60]):

The invention or inventive concept of a patent or patent application should be discerned from the specification, the whole of the specification including the claims. The body of the specification describes the invention and should explain the inventive concepts involved. While the claims may claim less than the whole of the invention, they represent the patentee's description of the invention sought to be protected and for which the monopoly is claimed. The claims assist in understanding the invention and the inventive concept or concepts that gave rise to it. There may be only one invention but it may be the subject of more than one inventive concept or inventive contribution. The invention may consist of a combination of elements. It may be that different persons contributed to that combination.

43 The appellants also accept that the primary judge recognised the following principles:

(a) Whether or not a person should be regarded as an inventor is quintessentially a question of fact;

(b) Rights in an invention are determined by objectively assessing contributions to the invention, rather than an assessment of the inventiveness of respective contributions: JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68 per Crennan J (at [132]);

(c) The role of joint inventors does not have to be equal; the assessment is qualitative, rather than quantitative: Polwood (at [33]);

(d) One criterion for inventorship may be to determine whether the person’s contribution had a material effect on the invention: Polwood (at [34]);

(e) If the final concept of the invention would not have come about without a particular person’s involvement, the person has entitlement to the invention: JMVB Enterprises (at [132]) and Polwood (at [53]);

(f) Joint inventorship may also arise where the person constructing the apparatus contributed to a different or better working of it, which was then described and claimed: Polwood (at [33]);

(g) The fact that the parties were in collaboration is a relevant factor: JMVB Enterprises (at [132]) and Polwood (at [53]); and

(h) It is not appropriate to consider the novelty or inventiveness of what is alleged to be the invention as part of the determination of inventorship: Bodken: Patent Law in Australia (Thomas Reuters, 2nd ed) (at [8070]).

44 The problem, they say, is that his Honour misapplied these principles. The appellants contend that the first factual inquiry in the present situation is to assess the respective contributions of Mr Thomas and Mr Kafataris. They say that the determination of whether Mr Kafataris’ contribution entitled him to rights in the invention in the PCT Application can and should occur by assessing what Mr Thomas’ contribution was as a matter of fact (based on the findings at trial with respect to Mr Thomas and Mr Walsh) and comparing it with the invention disclosed in the PCT Application. The question of what a particular contribution will be is a question which then ought to be tested against what the specification discloses the invention to be, which is a question of construction. The appellants argue that the primary judge erred in the approach taken in respect of those steps.

45 Specifically, it is argued that it was erroneous to characterise Mr Thomas’ invention prior to the contribution by Mr Kafataris as having been a supplementary betting opportunity of general application. Rather, it was that the invention prior to the contribution by Mr Kafataris was confined to the Third Card Baccarat Bet and was not of general application.

46 The appellants rely upon the contribution by Mr Thomas as identified at [141]-[144] of the primary judge’s reasons in the following terms:

141 As I have said, Mr Thomas asserted that he gave consideration even prior to the filing of the provisional application in April 2012 to other card games. I do not accept that evidence as either accurate or truthful. I am not satisfied that any card game other than baccarat passed through his head at that time.

142 I regard his opinion in [6] of his affidavit of 4 July 2014 that the supplementary betting system can be applied to "all casino table card games" as at best speculative and at worst a contrivance. It can obviously apply to baccarat and blackjack, but Mr Thomas was conspicuously incapable of pointing to other card games to which it might be applied, and he never did, prior to the involvement of Mr Kafataris, identify when it would be available for blackjack.

143 Likewise, I do not accept his evidence that he intended it to apply to all table card games, as he asserted at [7] of his affidavit. If he did intend that I would have expected to find some contemporaneous support, but there is none. When given ample opportunity in cross examination he was entirely inept at explaining his views as set out in those paragraphs [6] and [7]. He was simply incapable of giving any comprehensible explanation as to what card games he had in mind in relation to a supplementary betting option. He nominated poker but again could not explain how a supplementary betting option could be exploited in that game (T74/25-T76/25).

144 I do not consider Mr Thomas ever held the view, prior to Mr Kafataris raising the possibility in relation to blackjack, that it could be applied in that context. There is no evidence for example he had worked through the rules of any game other than baccarat and I consider it is inconceivable, absent some special expertise which he clearly did not possess, that he would have been able to make such a statement that the option was available for "all casino table card games" unless he was being boastful or simply dishonest.

47 It is contended that these findings clearly indicate, as a matter of fact, that Mr Thomas did not make an invention of any supplementary betting option that extended beyond the limited field of his own knowledge, namely, baccarat. It was inconsistent with those findings for the primary judge to conclude, the appellants say, that the inventive contribution by Mr Thomas was “a method of wagering whereby a supplementary betting option can be exploited”.

48 Language appearing in the Provisional Application which, read in isolation, may suggest a broader application of the invention. Specifically, that language under the heading “Background” setting out the specification at p 1:

The present invention relates to games of chance and more particularly relates to a game feature whereby a player can play a primary game and exercise bet options on a secondary or auxiliary game either separate from the primary game or in co-operation with the primary game. The present invention also relates to an alternative to the known baccarat games which provides increased betting options and increase [sic] actual or perceived opportunities for a win.

As the appellants concede, a similarly broad statement to that referred to above also appears in the next paragraph of the “Background” section.

49 The appellants accept that Mr Walsh drafted the Provisional Application and the PCT Application in those terms, but point to the fact that the statement identified was at odds with the substance of the disclosure in the body of the specification, which is limited to baccarat. It contains the description of the invention that is heavily dependent on the rules of baccarat and how they can be modified to accommodate the Third Card Baccarat Bet.

50 That is evident from the content of the text of the Provisional Application that specifically pertains to baccarat, including:

the title “BACCARAT GAME WITH SUPPLEMENTARY BETTING OPPORTUNITY”; and

statements under the heading “INVENTION” relating to the broadest form of the invention, such as:

• “In the broadest form the present invention comprises: A method of playing baccarat comprising the steps of …”;

• “In another broad from the present comprises: a game of baccarat in which …”; and

• “In its broadest form the present invention comprises: A baccarat game in which …”.

51 Accordingly, the appellants contend that it could not be concluded that the Provisional Application was directed to a broader invention beyond the Third Card Baccarat Bet identified in the context of baccarat.

52 The appellants stress that Mr Walsh, the patent attorney, made no contribution to the inventive process as he had no expertise in card games and this should have been determinative of the fact that the invention made by Mr Thomas was confined to the Third Card Baccarat Bet. The Third Card Baccarat Bet was not taken by Mr Thomas to any level of abstraction. Any abstraction of the Third Card Baccarat Bet to a supplementary betting opportunity of broader application was done only speculatively to leave open the possibility that the patent may have a wider application than baccarat purely in a theoretical sense.

53 In relation to the description of the invention as claimed in the PCT Application, the appellants note that the primary judge described the invention as being a “method of wagering whereby a supplementary betting option can be exploited”. The appellants point out that the primary judge (they say correctly) found that the PCT Application was not confined to a method (cf the Provisional Application which was), suggesting that the application changed as a result of Mr Kafataris’ involvement. In the substance of the specification, it will be seen that:

(a) the title is “Card Game with Supplementary Betting Option”;

(b) the “Background” section broadly relates to “card games including black jack and baccarat” and “card games such as baccarat and blackjack” (at [001]), which is more broad than the references in the Provisional Application that were merely to baccarat;

(c) the detailed description states (at [0044]):

The invention will be described with reference to the card games of Baccarat and Black Jack. However, it will be appreciated that the invention can be adapted to alternative card games.

Such a sentence did not appear in the Provisional Application; and

(d) the claims encompassed the broadened concept of allowing an opportunity to place a bet on the effect of a third card added to a hand without a primary bet being a precondition to that bet. Of the three independent claims, claim 27 is a version of the first statement of the invention in the PCT Application broadened from “a method of playing baccarat” to a “method of wagering on a card game”, while claim 1 and claim 23 each claim “a card game” as opposed to the second and third statements of invention in the Provisional Application which relate to a “game of baccarat” and “baccarat game” respectively. So in these respects the primary judge was, the appellants acknowledge, quite correct in observing that unlike the Provisional Application, the PCT Application was one relating to all card games.

54 The appellants emphasise what they describe as generally favourable credit findings towards the evidence of Mr Kafataris, with the exception of the conclusion as to the substance and effect of what he achieved. The appellants rely, for example, on the fact that it was found that Mr Kafataris raised the question of blackjack at a meeting on 19 December 2012 in circumstances where Mr Thomas had not even considered it. They rely upon the fact that from January to March 2013, Mr Kafataris “developed a side bet specific to … blackjack” (although I note that the primary judge’s reference to this was limited to a quotation from an affidavit of Mr Kafataris). They rely on the finding that Mr Kafataris spent about 50 hours working on the game of blackjack and, in particular, working on odds creating tables and creating a blackjack dealer bet game rules document. The appellants rely on the fact that in February and early March 2013 Mr Walsh was preparing for the filing of the PCT Application, and had meetings and discussions with his clients and Mr Kafataris for the purpose. They rely on the finding that on 4 March 2013, Mr Kafataris indicated to Mr Walsh that he wanted the PCT Application to make specific reference to blackjack. The appellants stress the finding that on 10 March 2013 Mr Kafataris sent an email to Mr Walsh outlining the possible application of a supplementary bidding option for blackjack, and they rely upon findings in relation to a meeting in which the topic was raised by Mr Kafataris, in contrast to the finding that Mr Thomas did not conceive of a supplementary betting opportunity in relation to blackjack prior to the involvement of Mr Kafataris.

55 The appellants contend that once the invention is characterised in the manner for which the appellants contend, it must follow, in light of the factual findings, that the contribution of Mr Kafataris was material. Those findings indicate necessarily, the appellants argue, that before his contribution, the invention by Mr Thomas was limited to the Third Card Baccarat Bet. It was an invention confined to the rules of baccarat and not one of broader application. It was Mr Kafataris who subsequently conceived of and developed a supplementary bidding opportunity in the context of blackjack.

56 On an alternative argument, even if the primary judge’s characterisation of the invention before Mr Kafataris’ contribution was correct, the appellants still say they should have won if an assessment of the invention is based on a broader characterisation of the contribution of Mr Kafataris. The appellants rely on the passage in Polwood (at [33]) where the Full Court observed that “joint inventorship may arise where … the person constructing the apparatus contributed to a different or better working of it which is then described and claimed”. They stress that it is clear that Mr Kafataris contributed to a different and better working of the supplementary betting opportunity. After his contribution, the supplementary bidding opportunity was also embodied in blackjack. Essentially the same arguments are repeated, even if the assessment of the invention is based on a broader characterisation.

57 The appellants including Mr Kafataris also point to the material differences between the supplementary bidding opportunity by Mr Thomas and that identified by Mr Kafataris, notably, the event on which the stake is placed, that is, the outcome of the game in baccarat, on the one hand, compared with whether the dealer “busts” in blackjack. This was necessitated by different rules of baccarat and blackjack and the differences were discussed by the primary judge, but his Honour went on to reject those as non-material. The appellants maintain that in light of the key role played by the different rules of the game in determining whether a supplementary betting opportunity is available at all, his Honour erred in that regard.

58 The appellants also contend that the primary judge was in error in that, despite having recognised the inappropriateness of considering the novelty or inventiveness of what is alleged to be the invention as part of the determination of inventorship, his Honour then actually did that in assessing the contributions by Mr Kafataris. The appellants complain that insofar as his Honour considered any question of inventiveness, that consideration was addressed the way the patent attorney, Mr Walsh, “saw it”. This, they say, was inconsistent as his Honour explicitly rejected as “fanciful” and “having no basis whatsoever… as a matter of practical reality” the evidence from Mr Walsh that Mr Thomas had seen the invention as extending beyond baccarat. The conception of what was the notion of novelty and what was involved the inventive step was apparently based entirely on Mr Walsh’s conception, the appellants contend. The appellants argue that those findings appeared to have led his Honour incorrectly to reject the appellants’ submission, which was that identification of the supplementary betting opportunity in a second card game led to the generalisation from a method of playing baccarat to a wagering system applicable to all card games and that constituted a material contribution. The relevant question was whether Mr Kafataris made a contribution to the inventive concept which was to be ascertained from what Mr Kafataris in fact did and what the inventive concept was, not whether the contribution itself was novel or demonstrated an inventive step (factors to be determined based on each claim of the invention and involving the more objective questions of whether an invention is new or inventive in itself compared with the prior art base and/or common general knowledge).

59 For all those reasons, the approach taken by the primary judge led him to the wrong conclusion, the appellants say.

Co-inventorship - consideration

60 In considering the appellants’ arguments, the real question, as the respondents advanced at trial, is whether the primary judge was correct in concluding that the invention the subject of the Provisional Application and further developed in the PCT Application was a method of supplementary betting for paying card games. The respondents’ position was that the method may be applied to blackjack, just as it may be applied to baccarat or any other card game. That was the factual position when the Provisional Application was filed, whether or not it had expressly occurred to the inventor, Mr Thomas. It remains the position.

61 The respondents’ argument is correct. In the Provisional Application itself, baccarat was only identified as a card game embodiment of the invention. An embodiment of an invention is a manner in which an invention could be made, used, practised or expressed as described in the specification. Inventions can take the form of that embodiment or many other embodiments. The identification of baccarat as a card game embodiment of the invention was a means of disclosing the invention sufficiently for it to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art so as to satisfy the requirements of s 40(1) of the Patents Act. Further, it was necessary for it to provide support for a later complete specification to satisfy s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act. The differences between the PCT Application and the Provisional Application were not significant. In the PCT Application, blackjack was also identified as another embodiment of the same invention. In all likelihood, that arose as a result of discussions with Mr Kafataris, but that does not answer the question as to whether or not he contributed to the invention, which had already been invented. This highlights a somewhat unusual feature of this dispute, namely, the inventorship contribution is alleged to have taken place after, rather than before, the lodging of the Provisional Application when and in which, on any view, the parties accept that an invention was published.

62 It is common ground, arising from cases such as University of Western Australia v Gray (2009) 179 FCR 346 (at [221] and [237]) and Lee v Commissioner of Patents [2011] AATA 818 (at [17]), that determining inventorship involves a two part inquiry. The starting point is to analyse the inventive concept of the patent applications. The next step is to consider whether Mr Kafataris, as the alleged co-inventor, made contributions that had a material effect on the inventive concept.

63 The primary judge explicitly adopted and applied the two part inquiry process. His Honour looked to the Provisional Application to consider the nature of the invention in order to assist him in forming a view about whether Mr Kafataris made a material contribution to the inventive concept in the PCT Application. It was necessary to do this because the appellants sought to persuade his Honour that the invention in the PCT Application was fundamentally different from the invention in the Provisional Application. This, they argued, was because Mr Kafataris had made a material contribution to the PCT Application, but not to the Provisional Application.

64 Of course, at the time of filing the Provisional Application, Mr Kafataris had no involvement whatsoever and had not even met Mr Thomas. There is no scope for any suggestion of contribution to the invention the subject of the Provisional Application. Accordingly, what properly constituted that invention was a topic of importance. On applying the two part test, the primary judge correctly determined that the inventive concept within the PCT Application was the method of wagering contended for at trial by the respondents.

65 The proper inquiry is as to a person’s contribution to the conception of the invention in order to determine whether there is co-inventorship. This is the correct question, rather than the verification and reduction to practice of the existing inventive concept, other than in those rare cases where the reduction of the concept to practice itself requires an inventive contribution: Gray (at [248]). It was in this context that the primary judge needed to and did examine the substantive effect of the work carried out by Mr Kafataris and concluded, as was open to him, that Mr Kafataris had simply taken the inventive concept of the supplementary betting option and provided another example of its application in addition to baccarat, namely, that of blackjack.

66 There was no evidence on which the primary judge could have reached a conclusion, and his Honour was correct not to conclude, that Mr Kafataris had made any contribution to the inventive concept itself underpinning the PCT Application, namely, a “secondary or auxiliary bet option exercised independently or in cooperation with the primary game”. There was logical support for this because, although in terms of credibility the primary judge did not seem to have serious doubts about Mr Kafataris, the evidentiary foundation for his contribution was plainly inadequate. His Honour concluded that the evidence of Mr Kafataris was “problematical” in the sense of lacking precision, being “exaggerated” (especially in relation to the calculation of odds), and was devoted to “identifying whether and if so when a supplementary bet could be placed within the existing rules of blackjack”.

67 It is, of course, common practice for a provisional application to filed in the first instance to obtain as early a priority date as possible for the invention there described, while securing up to an additional 12 months to gather as much information as possible to enable as full a description of the invention to be included in the complete application, so as to then support the invention being claimed as broadly as possible. It is well established that a provisional application does not have to describe every way that an invention could be applied. It does not have to list every possible embodiment. It would be rare for a provisional application to do so.

68 There is ample support, even within the Provisional Application, for the conclusion that the inventive concept was of the broader nature found by his Honour. Under the heading “Background”, the invention was explained in the introductory statement as being:

The present invention relates to games of chance and more particularly relates to a game feature whereby a player can play a primary game and exercise bet options on a secondary or auxiliary game either separate from the primary game or in co-operation with the primary game.

(emphasis added)

69 This and following paragraphs of the Provisional Application supported the construction reached by the primary judge and the conclusion he reached as to the inventive concept. For example, the discussion on the prior art (which teaches the use of auxiliary bets in poker machines) was described by reference to a long felt want in the industry to provide “more versatile table games and more particularly games of chance in which a primary and secondary game can be operated cooperatively or independently of each other” (emphasis added). The argument advanced for the appellants to the effect that the primary judge ought to have found that the contribution by Mr Thomas was confined to the game of baccarat cannot be accepted. Had the primary judge relied upon only that embodiment, he would have approached the construction of the provisional patent erroneously. It is not permissible to confine the invention the subject of the Provisional Application to the example set out in its embodiment.

70 All of this being so, Mr Kafataris failed to demonstrate that he made a material contribution to the inventive concept.

71 Even if this broader construction of the Provisional Application were erroneous, it would still be necessary for Mr Kafataris to demonstrate some material contribution by the so-called “blackjack invention”. This is because, having regard to s 40(4) of the Patents Act, the complete application, namely, the PCT Application, “must relate to one invention only”. Therefore, if Mr Kafataris did in fact develop a “blackjack invention” over and above a baccarat invention, it could not be part of the PCT Application as it would have to be separated out of that application into a divisional application. At trial it seems that Mr Kafataris was confronted with some difficulty concerning this concept, as reflected in the observations of the primary judge (at [54]) where his Honour said:

Counsel for the plaintiff initially contended that the only invention Mr Kafataris makes is blackjack and said that was a separate and distinct invention (T2/38). That position was resiled from (T11/13) and definitively abandoned (T304/20-T311/44). …

72 Of course the PCT Application does cite alternative embodiments, being baccarat and blackjack, but these are alternative embodiments of the one invention. As noted above, the inventive concept for each embodiment is substantially unchanged. It is the same as it was in the Provisional Application. There can be no suggestion that the inventive concept is dependent in some way upon it being used in any particular card game.

73 Much like the provisional application, the PCT Application also reflects this in its content such that:

(a) the invention is introduced in the “Background” in similar terms to the Provisional Application;

(b) the “Prior Art” section describes a prior art base including the rules and wagering options in the popular games, baccarat and blackjack. Here, the specification foreshadows the the novel or inventive aspects of the “invention” (at [0011]) in relation to the secondary option that may be exercised. The rules for those games were not set out, but simply described as well-known and well-established;

(c) under the heading “Invention”, similar terms are used to introduce the invention in the PCT Application as those in the Provisional Application. Thereafter, under each consistory statement the specification refers to baccarat and blackjack as alternative embodiments of the “card game” to which the invention in the broadest sense can be applied. The “Invention” section of the PCT Application contains consistory claims (at [0035], [0038] and [0041]) for the invention in its broadest form reflecting the inventive concept in the PCT Application and Provisional Application. There is no reference to blackjack or baccarat forming part of the invention; and

(d) the invention is then the subject of the claims. The inventive concept is present in each claim. The claims which incorporate, as the integer, “the card game is blackjack” are dependent claims necessarily narrower than the independent claims, which are 1, 23 and 27. These independent claims are supported by the Provisional Application. This aspect of the claims consists of “non-patentable integers derived from prior art” and do not form part of the inventive concept in the specification.

74 The work of Mr Kafataris, once he had examined the Provisional Application, was to identify blackjack as being a further game in which the secondary wager concept could be applied, as he knew it was a game that already offered side bets. The finding reached by the primary judge was undoubtedly correct that Mr Kafataris was “alerted to the concept or idea of a supplementary or subsidiary betting opportunity by Mr Thomas” and then considered the rules of blackjack to determine if “a similar opportunity arose”. There can be no other conclusion as to how Mr Kafataris approached his work. But his work itself then was described more in quantitative than qualitative terms and, as expressly found and not seriously challenged, largely involved copying from publicly accessible material and rules provided to him by Mr Thomas.

75 At the root of the appellants’ failure was the finding that the addition of a further card game “did not bring about a change to the invention, rather it merely provided another example”. This finding was undoubtedly correct. The work done by Mr Kafataris did not alter the nature of the invention. There is nothing novel about the game of blackjack, nor was there anything novel about the secondary bet option for blackjack, which was an obvious application of the inventive concept.

76 The appellants point to the fact that the elements required to prove a misuse of confidential information are well established from cases such as Coco v AN Clark (Engineers) Ltd [No 2] [1969] RPC 41 (at 47) and Commonwealth v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd (1980) 147 CLR 39 (at 51). Those elements are:

(1) The information must have the necessary quality of confidence;

(2) The information must have been imparted in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence; and

(3) There must be an unauthorised use of that information to the detriment of the person claiming the confidence.

77 In relation to (1), the primary judge concluded (at [251]) that the information in relation to blackjack provided by Mr Kafataris, which appeared in the PCT Application, did not possess the requisite qualities requiring protection in equity. As to (2), his Honour concluded (at [252]) that the information in relation to blackjack provided by Mr Kafataris was not imparted in circumstances importing any obligation of confidence, and, as to the third matter, his Honour (at [253]) was not satisfied that Mr Kafataris did anything other than consent or authorise the inclusion of that information in the PCT Application.

78 The appellants argue that these conclusions, however, were all affected by the failure at trial to properly distinguish between different types of information provided by Mr Kafataris to Mr Thomas, in particular, between odds relating to baccarat and the new concept developed by Mr Kafataris in relation to blackjack. (This assumes a correct characterisation of the work done by Mr Kafataris.) The different types of information provided by Mr Kafataris in relation to odds for baccarat were considered. One of the exchanges recorded by the primary judge related to only the First Baccarat Odds Spreadsheet discussed and sent on 12 December, whereas Mr Kafataris tabulated some odds relating to baccarat and sent them to Mr Thomas. All of that, however, was before Mr Kafataris conceived, the appellants argue, of the new supplementary betting option for blackjack and before a commercial proposal had been developed. The information as to the blackjack concept was of a different character to the odds spreadsheets and was disclosed in the course of commercial negotiations for a joint venture. It was not publicly available or easily derivable, rather it was provided by Mr Kafataris to Mr Walsh for inclusion in the PCT Application in circumstances where it is established that the parties were in negotiations to conclude a commercial deal.

79 Even if the odds spreadsheets were public information, it is plain, the appellants argue, that the emails of 10 March and 18 March 2013 and the attached document “Blackjack Dealer Bet Game Rules” had the necessary quality of confidence. The inclusion of the substance of that information and, indeed, claims relating to it in the PCT Application meant that Mr Walsh and Mr Thomas implicitly recognised that it had not been previously made publicly available and was a valuable addition to the PCT Application.

80 The appellants rely upon the statement in Coco where Megarry J said (at 48) (citations omitted):

In particular, where information of commercial or industrial value is given on a business-like basis and with some avowed common object in mind, such as a joint venture or the manufacture of articles by one party for the other, I would regard the recipient as carrying a heavy burden if he seeks to repel a contention that he was not bound by an obligation of confidence.

81 Mr Kafataris argues that, on viewing the substance of the dealings as a whole, the primary judge ought to have concluded that the consent of Mr Kafataris to the conclusion in the PCT Application of the information in the emails of 10 March and 18 March 2013 in relation to the supplementary betting opportunity for blackjack was for the limited purpose of furthering the expected joint venture arrangement between the parties as to the exploitation of the invention in the PCT Application (including, that the PCT Application would proceed in the name of a joint venture company or would otherwise be jointly owned). The appellants argue that given that no commercial arrangement was concluded between the parties, the information was used in the PCT Application for purposes other than that for which it was communicated and that this was in violation of the equitable rights of confidence held by Mr Kafataris. It is argued that the facts fall squarely within the category of the case of confidential information communicated in contemplation of and for the limited purpose of a business arrangement that did not materialise. The appellants argue there should be a constructive trust imposed over the PCT Application, which uses the information.

Confidential information - consideration

82 The transcript of the proceeding before the primary judge reveals that the appellants accepted that if they failed on inventorship, they would fail on confidential information. On appeal, they appear to have changed their position or seek to do so. This is not an instance in which the appellants should be permitted to depart from their pleaded case. They now seek to distinguish between odds relating to baccarat and Mr Kafataris’ new concept in relation to blackjack. No such distinction was advanced on their pleaded case and the evidence did not involve examination of such an approach. That departure should not be permitted. That is an end to this aspect of the appeal, but in any event, the concession was appropriate.

83 That can be seen from the analysis by the primary judge. First (and unchallenged), his Honour concluded that the parties were not in the necessary fiduciary relationship. His Honour rejected the contention that the parties were in a fiduciary relationship, accepting on the evidence the contention advanced by the respondents that there was no evidence that any of the parties undertook to act in the interests of the others and that their relationship was one of arms-length commercial negotiations: see, for example, Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corporation (1984) 156 CLR 41 per Gibbs CJ (at 70). His Honour was well satisfied that the relationship was not one in which the respondents had undertaken nor agreed “to act for or on behalf of the interests of another person in the exercise of the power or discretion which will affect the interests of that person in a legal or practical sense”, to use the words of Justice Mason in Hospital Products (at 96-97).