FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 2)

[2016] FCAFC 111

ORDERS

OTSUKA PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD First Appellant BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB COMPANY Second Appellant | ||

AND: | GENERIC HEALTH PTY LTD ACN 110 617 859 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO AND NICHOLAS JJ:

Introduction

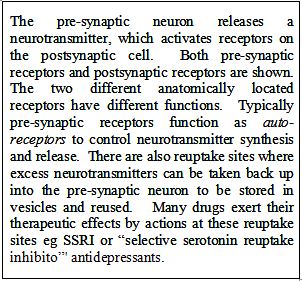

1 This appeal concerns a carbostyril compound called aripiprazole and its use in the treatment of the disorders of cognitive impairment caused by treatment-resistant schizophrenia, cognitive impairment caused by inveterate schizophrenia, and cognitive impairment caused by chronic schizophrenia.

2 The appellants are Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd is the registered owner of Patent No 2005201772, titled “Substituted carbostyril derivatives as 5-HT1A receptor subtype agonists” (“the 722 Patent”), and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company is a licensee of the 722 Patent. The priority date of the 722 Patent is 29 January 2001 and the patent was granted on 6 September 2007. The respondent to the appeal is Generic Health Pty Ltd and it is a pharmaceutical company that supplies generic pharmaceuticals and other products. The respondent obtained registration of a number of aripiprazole products on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. These products are registered under either the ARIPIPRAZOLE GENERICHEALTH label or the ARIPIPRAZOLE GH label. For present purposes, only the GH products are relevant. They are registered for the treatment of schizophrenia, including maintenance of clinical improvement during continuation therapy.

3 The appellants brought a proceeding against the respondent for infringement or threatened infringement of claims 1 and 7 of the patent. The respondent brought a cross-claim in which it alleged that the claims were invalid on various grounds, including a lack of novelty and lack of an inventive step. A key issue before the primary judge was the proper construction of the claims which his Honour resolved in a manner which we will identify later in these reasons. The primary judge then addressed the issue of infringement and he held that, assuming the claims to be valid, the respondent had infringed or threatened to infringe the claims. However, his Honour held that the claims were invalid for lack of novelty and lack of an inventive step. He rejected the other grounds of invalidity raised by the respondent. On 16 July 2015, the primary judge made orders that claims 1 and 7 of the 722 Patent be revoked and that the appellants’ claims for infringement of the 722 Patent be dismissed (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191; [2015] FCA 634).

4 In the appellants’ written outline of submissions in chief, they submitted that the primary judge had made six errors. Four of the alleged errors relate to the primary judge’s construction of the claims. The fifth alleged error related to the primary judge’s decision when considering inventive step to combine two pieces of prior art for the purposes of s 7(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”). That challenge was abandoned during the course of the appellants’ oral submissions. The sixth alleged error is that, as a result of the primary judge’s erroneous construction of the claims, his Honour’s findings on novelty and inventive step were flawed. Subject to one matter, this submission must fail if his Honour’s construction of the claims is upheld. It follows that the proper construction of the claims is central to the determination of the appeal.

5 In addition to resisting the appeal, the respondent has filed a notice of contention in which it challenges the primary judge’s conclusions with respect to infringement and contends that, even if the appellants succeed on the issue of the proper construction of the claims, their case on infringement must fail.

6 For the reasons which follow, the primary judge’s conclusions about the proper construction of the claims are correct as are his conclusions about lack of novelty and lack of an inventive step. The appeal must be dismissed. It is not necessary to consider the respondent’s submissions with respect to infringement of the claims.

The Claims in the 722 Patent

7 It will be necessary to consider the provisions of the specification of the 722 Patent in detail later in these reasons. However, at this stage, it is convenient to set out the claims, the features of the claims which raise the points of construction and the primary judge’s characterisation of the claims. Claim 1 of the 772 Specification is as follows:

Use of a carbostyril compound of [a given structural formula] … or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or solvate thereof, for the production of a medicament, effective in the treatment of disorders of the central nervous system associated with [the] 5-HT1A receptor subtype, which disorder

(i) is selected from cognitive impairment caused by treatment-resistant schizophrenia, cognitive impairment caused by inveterate schizophrenia, or cognitive impairment caused by chronic schizophrenia, and

(ii) fails to [respond] to antipsychotic drugs selected from chlorpromazine, haloperidol, sulpiride, fluphenazine, perphenazine, thioridazine, pimozide, zotepine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or amisulpride.

8 Claim 7 of the 772 Specification is as follows:

A method for treating a patient suffering from disorders of the central nervous system associated with [the] 5-HT1A receptor sub-type, which disorder

(i) [is] selected from cognitive impairment caused by treatment-resistant schizophrenia, cognitive impairment caused by inveterate schizophrenia, or cognitive impairment caused by chronic schizophrenia, and

(ii) fails to [respond] to antipsychotic drugs selected from chlorpromazine, haloperidol, sulpiride, fluphenazine, perphenazine, thioridazine, pimozide, zotepine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or amisulpride,

comprising administering to said patient a therapeutically effective amount of a carbostyril compound of [the given structural formula] … or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or solvate thereof.

9 The primary judge noted that it was not in dispute that, in one form, the carbostyril compound, referred to in each claim, is aripiprazole.

10 The first and major point of construction relates to that feature in the claims which describes the named disorders as associated with [the] 5-HT1A receptor subtype. We will refer to this as the association feature. The second point of construction relates to that feature in the claims which refers to the failure to respond to antipsychotic drugs selected from the drugs named in the claims. We will refer to this as the failure to respond feature.

11 The primary judge characterised claim 1 as a Swiss type claim. He noted that the generalised form of a Swiss type claim is “the use of compound X in the manufacture of a medicament for a specified (and new) therapeutic use”. His Honour discussed the history of such claims and he made reference to the decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office in EISAI/Second Medical Indication (G05/83) [1979-85] EPOR B241 and the decisions in Bristol-Myers Squibb v Baker Norton Pharmaceuticals Inc [1999] RPC 253 (“Baker Norton”), and Actavis UK Ltd v Merck & Co Inc [2009] 1 WLR 1186. His Honour noted that the legal position in Australia was different from that in the United Kingdom and he referred to the decision of the High Court in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Limited [2013] HCA 50; (2013) 304 ALR 1 at [50] per French CJ; at [286] per Crennan and Kiefel JJ; and [314] per Gageler J. No aspect of this part of his Honour’s analysis has been challenged on the appeal.

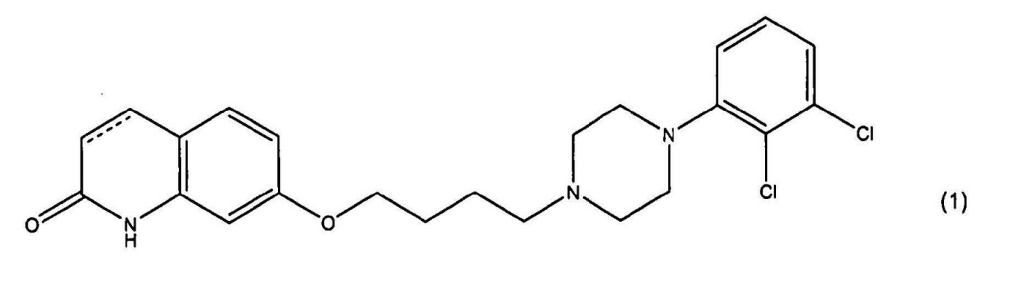

12 The primary judge considered whether an invention defined by a Swiss type claim is properly characterised as a product claim or as a method or process claim and, further, whether either of these characterisations are apt for a Swiss type claim. The appellants’ case before the primary judge was that Swiss type claims are process claims, whereas the respondent’s case was that they are neither method or process claims nor product claims. His Honour said that the words “method” and “process” were to be given their ordinary English signification, and that for the purpose of the question he was considering, there was no difference between the two. He reached the conclusion that “method or process” were apt to describe the content and subject matter of the Swiss type claim to which he had referred. He said that this approach accorded with the authorities which he identified (at [119]-[120]).

The Medical and Scientific Evidence

13 Each party put forward a considerable volume of expert evidence. There was also some lay evidence, but it is not necessary to refer to that evidence for the purposes of the appeal.

14 The appellants called Professor Bruce Sugriv Singh who swore four affidavits, Associate Professor Jonathan Phillips who swore one affidavit, and Associate Professor Trevor Ronald Norman who swore three affidavits.

15 Professor Singh is a consultant psychiatrist in private practice at the Melbourne Clinic and a senior consultant psychiatrist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. He was Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne, where he has been a Professor of Psychiatry since 1991. He has been a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (“RANZCP”) since 1979.

16 Associate Professor Phillips is a consultant psychiatrist in private practice. He is an Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales, the University of Adelaide and James Cook University. He is a Fellow of the RANZCP and was the President of the College from 1998 to 2000.

17 Associate Professor Norman is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Melbourne. He was an Adjunct Professor in the School of Behavioural Sciences at La Trobe University and President of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress from 2002 to 2004.

18 The respondent called Professor Patrick Dennistoun McGorry who swore four affidavits, Dr Jeremy Francis O’Dea who swore six affidavits, and Professor Iain Stewart McGregor who swore one affidavit.

19 Professor McGorry is a consultant psychiatrist and Professor of Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne. He is an Executive Director of the Orygen Youth Health Research Centre and has been a Fellow of the RANZCP since 1986.

20 Dr O’Dea is a consultant psychiatrist in public and private practice and a Conjoint Lecturer in the School of Psychiatry at the University of New South Wales. He has been a Fellow of the RANZCP since 1991.

21 Professor McGregor is Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Sydney. He is a Professorial Fellow of the Australian Research Council.

22 The parties prepared an agreed primer of the medical and scientific background relevant to the case for the use of the primary judge. This primer was prepared from the affidavit evidence given by the expert witnesses. His Honour described a number of the medical and scientific concepts in detail in his reasons. In order to properly understand the issues of construction raised on the appeal, it is necessary for us to summarise a number of the medical and scientific concepts, although we do not need to do so with the same level of detail adopted by the primary judge.

23 Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder affecting 1% of the population worldwide. Its main features are disturbances in the ability to experience reality, a lack of capacity to engage with others in the outside world, and disturbances in thinking, behaviour and emotional responses. Standard definitions of schizophrenia state that the symptoms must last for at least six months for the diagnosis to be made. The cause of schizophrenia is not known, but both genetic factors and environmental stressors operating prenatally and in childhood may play a part.

24 The symptoms of schizophrenia can be classified according to separate dimensions: positive and negative. Positive symptoms include hallucinations (the perception of a sensory experience in the absence of a source), delusions (fixed false beliefs not shared by others), and disorganised speech. Negative symptoms include blunting of emotional response, apathy, amotivation and poverty of thought.

25 More recently, some have classified the symptoms of schizophrenia by reference to two additional dimensions: cognitive and mood. Cognitive symptoms refer to a range of impaired higher cognitive functions including problems with attention, long-term memory, abstraction and planning. Mood symptoms can include anxiety and depression.

26 The course of schizophrenia can be variable. Acute schizophrenia is schizophrenia that lasts for more than six months and then remits. Chronic schizophrenia is schizophrenia which lasts significantly longer than six months and usually for many years. A chronic schizophrenia patient may have his or her positive symptoms under control, but negative symptoms persist. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia is a particular form of chronic schizophrenia where the patient’s positive symptoms, in addition to negative and cognitive symptoms, are unresponsive to antipsychotic medication.

27 Schizophrenia is treated with antipsychotic medications described as being either “typical” or “atypical” antipsychotics. Typical antipsychotics were developed in the 1950s and 1960s and include chlorpromazine, haloperidol, sulpiride, fluphenazine, perphenazine, thiroidazine, pimozide, and zotepine. Atypical antipsychotics, currently used more widely in Australia than typical antipsychotics, block serotonin as well as dopamine receptors and include risperidone; olanzapine; quetiapine; and, amisulpride.

28 Some patients may not respond well or experience unacceptable side effects to a particular medication that is first prescribed. It is common to then try prescribing a different medication for those patients and this change to a different medication is known as “switching”.

29 The transmission of nerve impulses in the brain and peripheral nervous system takes place by means of specific chemical agents called neurotransmitters. Transmission within the peripheral nervous system is important not only for everyday processes necessary for survival (i.e., breathing, heartbeat, movement, etc.), but also for functions such as thinking (cognition) and feeling (emotion).

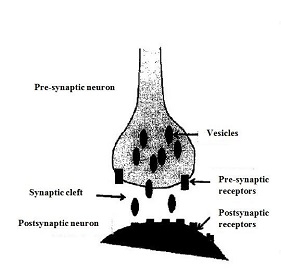

30 Neurotransmission is the process by which neurotransmitters transmit signals (electrical impulses) from one neuron to the next. Neurotransmission usually occurs when an electrical impulse is initiated in a neuron (known as the pre-synaptic neuron). The impulse arrives at the nerve terminal and causes the release of neurotransmitters. The neurotransmitters bind with receptors on another neuron (known as the post-synaptic neuron). The term ‘affinity’ refers to the strength of binding to the receptor.

31 A receptor is a protein molecule consisting of chains of amino acids and typically consists of three parts. The first part is an extra-cellular portion which protrudes above the cell membrane, such that it may receive signals from nearby cells. The second part is a transmembrane-spanning domain located within the cell membrane, arranged as a series of helical shapes which give the receptor its shape. The third part is an intracellular domain which interacts with intracellular elements to produce changes in second messenger systems.

32 For some receptors, the second part of the neurotransmitter will act as a ligand. The term “ligand” refers to a molecule that will bind to a receptor to induce a conformational change (i.e., a change in shape) and bring about an alteration in the function of the receptor. Neurotransmitters and hormones are endogenous ligands (i.e., they are present in the body). Drugs are exogenous ligands (i.e., they are introduced to the body).

33 An agonist is a drug that mimics the effects of an endogenous neurotransmitter by bringing about a similar conformational change (and therefore a similar biological response) in the receptor as that brought about by the endogenous ligand. An antagonist is a drug that binds to the receptor but does not bring about a biological response. Its effect is to block the action of the endogenous ligand. A partial agonist is a drug that binds to and activates a given receptor but has only partial efficacy at the receptor in that it elicits less than maximal response from the receptor.

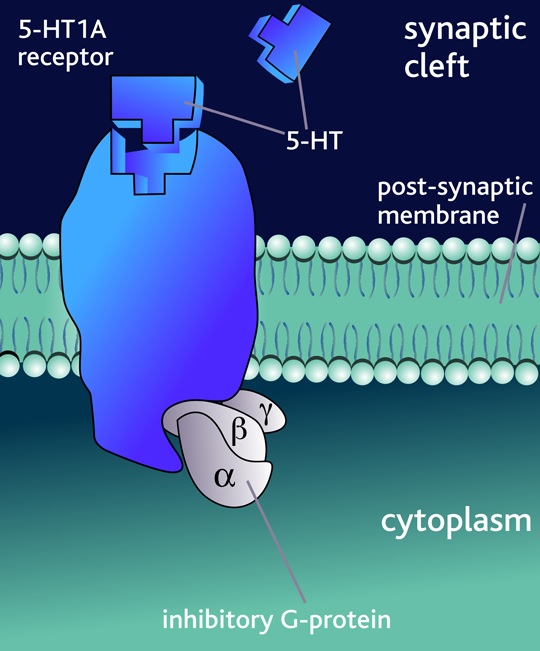

34 Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or “5-HT”) is a neurotransmitter intimately connected to neuropharmacology and found throughout the body, including in many cells that are not neurons. The serotonin system in the brain is perhaps one of the most complex due to the multiplicity of receptors with which serotonin can interact. 5-HT1A receptors are the best characterised of the 5-HT1 family of receptors and they have high affinity for serotonin.

35 The primary judge did not make specific findings about dopamine receptors. It is sufficient to note that Associate Professor Norman said that it has been inferred that the positive symptoms of schizophrenia arise because of over-activity of dopamine in the mesolimbic dopamine pathways of the brain. Professor McGregor agreed that medications that are effective in alleviating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia usually have some action as antagonists at dopamine D2 receptors, but did not agree that schizophrenia is in part a dopamine D2 disorder.

The Primary Judge’s Reasons

The Construction of the Claims

36 The primary judge set out the principles applied in the construction of claims in a way which is not controversial. The construction of a patent specification and of prior art documents is a matter for the Court. However, those documents are construed through the eyes of the hypothetical person skilled in the art. The words in the documents are to be given the meaning which the person skilled in the art would attach to them in light of common general knowledge and what is disclosed in the document itself (Osram Lamp Works Ld v Pope’s Electric Lamp Company Ld (1917) 34 RPC 369 at 391 per Lord Parker; Root Quality Pty Ltd and Another v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd and Others [2000] FCA 980; (2000) 49 IPR 225 (“Root Quality”) at [49] per Finkelstein J; Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron and Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 (“Kinabalu Investments”) at [45]). The “person” skilled in the art might be a team of persons (General Tire & Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company Limited and Others [1972] RPC 457 at 485 per Sachs LJ).

37 The primary judge said that there were three issues of construction.

38 The first issue of construction concerned the meaning of the association feature and whether the feature was an essential feature of the claims or purely descriptive. The appellants submitted that the association feature was a “broad requirement” that meant no more than that the 5-HT1A receptor was implicated in, or played a role in, the identified disorders. The primary judge set out the following passage from the appellants’ closing written submissions at trial:

The necessary relationship will be found to exist even if the 5-HT1A receptor is not faulty or defective in a patient suffering from the claimed disorder. There will also be the necessary relationship notwithstanding the 5-HT1A receptor is not solely responsible for the claimed disorder. Moreover, the necessary relationship will be satisfied notwithstanding the 5-HT1A receptor is not directly responsible for the claimed disorder.

(Original emphasis.)

39 His Honour identified (without setting out) a number of other passages in the appellants’ closing written submissions at trial and said that the appellants’ submission was that the evidence supported the conclusion that the 5-HT1A receptor is “relevantly associated” with cognitive impairment in chronic and treatment-resistant schizophrenia (at [133]). His Honour said the purpose of the appellants’ cross-examination of the experts was to demonstrate “the involvement, in some way, of the 5-HT1A receptor in cognition, the extent of any such involvement, the action of certain antipsychotic drugs on the 5-HT1A receptor and other receptors, and the effect that such drugs have or might have in improving impaired cognition” (at [139]).

40 The respondent’s submission was that the association between the disorders named in the claims and the 5-HT1A receptor subtype needed to be “a significant and consistent connection”, and that the evidence did not demonstrate that connection.

41 His Honour said that both parties treated the described association as one that required scientific proof and that each party said that this association was, in and of itself, an essential feature of the invention claimed. His Honour commented on the forensic reasons each party may have taken this approach and, in the case of the appellants, he suggested that they had taken the approach they had because it would make it more difficult for the respondent to prove its case on invalidity. At all events, his Honour summarised the appellants’ submission as being to the effect that it is only necessary to show that the 5-HT1A receptor is implicated in, or plays a role in, the disorders.

42 The primary judge said that he would not attempt to decide what he described as, in effect, a scientific controversy based on the literature in evidence and the witnesses’ opinions on that literature. He did not need to decide the scientific controversy because of the construction he placed on the claims. His Honour’s construction of the claims was that the association feature was but part of the description of an essential feature, namely the disorders to be treated (at [145]). His Honour said that the feature did not define a free-standing essential feature of the invention that added, meaningfully, to the identification of the specific forms of cognitive impairment ([at 146]).

43 The second issue of construction concerned the meaning to be given to the reference to cognitive impairment as a disorder caused by schizophrenia. His Honour referred to the evidence of the experts to the effect that cognitive impairment can be a symptom of schizophrenia. However, he noted that, properly described, it is not a disorder caused by schizophrenia. His Honour reached the conclusion that the 722 Specification made it tolerably clear that it is speaking of cognitive impairment as a symptom of schizophrenia, and that the claims should be understood accordingly. His Honour’s decision on this issue of construction is not challenged on the appeal.

44 The third issue of construction concerned the meaning of the failure to respond feature. The issue in relation to this feature was whether it meant that there has been a failure to respond to one or more such drugs (second line or later line treatment) or two or more such drugs (third line or later line treatment). His Honour construed the failure to respond feature as meaning a failure to respond to two or more such drugs (i.e., third line or later line treatment), having regard to the use of the plural “antipsychotic drugs” in the claims and the examples given in the 722 Specification.

Infringement

45 The primary judge’s construction of the association feature meant that when he came to consider the issue of infringement, he proceeded on the basis that “use of the compound to produce a medicament for (claim 1), or use of the compound as a method of treating (claim 7), one of those forms of cognitive impairment is use of the medicament or the method to treat a disorder for the central nervous system that is associated with the 5-HT1A receptor” (at [146]).

46 There were other issues in relation to infringement which the primary judge addressed. The respondent intended to market and supply the GH products in Australia and an issue arose as to whether that was a threatened infringement of claim 1 in circumstances where the method or process claimed in claim 1 is performed outside the patent area. His Honour considered a patentee’s exclusive right to exploit the invention in the patent area (s 13(1) of the Act). His Honour decided that the respondent’s intention to market and supply the GH products was a threatened exploitation of the invention and would have been a threatened infringement of the claim had it been valid (at [174]). The respondent challenges this conclusion in its notice of contention (ground 1(b)(i)). The appellants’ case in relation to the infringement of claim 7 was based on s 117 of the Act. The primary judge held that the GH products were not staple commercial products within s 117(2)(b), which is a conclusion challenged by the respondent in its notice of contention (ground 1(b)(ii)). His Honour then went on to consider if there was reason to believe that the GH products would be used in a way that infringed claim 7. He held that there was and that the appellants’ case on infringement of claim 7 would have been made out had the claim been valid.

Validity

47 The primary judge identified the prior art. For the purposes of the appeal, there are only four pieces of prior art which need be identified. There were other pieces of prior art put forward by the respondent at trial, but these were, for one reason or another, rejected by the primary judge as being relevant to the respondent’s invalidity claim.

US 528/EP 141

48 The 722 Patent identifies US Patent No. 5,006,528 (“US 528”), European Patent No. 367,141 (“EP 141”) and another patent, as related art containing “the same chemical structural formula as the carbostyril derivatives in the present invention”. Before the primary judge, it was accepted that the disclosures in US 528 and EP 141 are materially the same.

49 US 528 describes the field of invention in the following terms:

The present invention relates to novel carbostyril derivatives. More particularly, the invention relates to novel carbostyril derivatives and salts thereof, processes for preparing said carbostyril derivatives and salts thereof, as well as pharmaceutical compositions for treating schizophrenia containing, as the active ingredient, said carbostyril derivative or salt thereof.

50 In the section of US 528 which describes the invention, it is said that schizophrenia is the most common type of psychosis caused by an excessive neurotransmission activity of the dopaminergic nervous system in the central nervous system. The observations continue as follows:

Heretofore, a number of drugs, having the activity for blocking the neurotransmission of dopaminergic receptor in the central nervous system, have been developed, the example for said drugs are phenothiazine-type compounds such as Chlorpromazine; butyrophenone-type compounds such as Haloperidol; and benzamide-type compounds such as Sulpiride. These known drugs are now used widely for the purpose of improving so-called positive symptoms in the acute period of schizophrenia such as hallucinations, delusions and excitations and the like ….

51 The observations continue with a reference to, among other things, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia:

However, many of these drugs are considered as not effective for improving so-called the negative symptoms which are observed in the chronic period of schizophrenia such as apathy, emotional depression, hypopsychosis and the like. In addition to the above, these drugs give important side-effects such as akathisia, dystonia, Parkinsonism dyskinesia and late dyskinesia and the like, which are caused by blocking the neurotransmission of dopaminergic receptor in the striate body. Furthermore, other side-effects such as hyperprolactinemia and the like given by the drugs are become [sic] other problems …

52 The specification continues with the observation that, under the circumstances described, the development of drugs for treating schizophrenia having safety and clinical effectiveness, have been “eagerly expected”. The observations continue:

The present inventors have made an extensive study for the purpose of developing drugs for treating schizophrenia, which would be not only effective for improving the negative symptoms, but also effective for improving the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, furthermore such drugs would have less side-effects as compared with those shown by drugs known in prior art. As the result, the present inventors have successfully found carbostyril derivatives having strong activity for blocking neurotransmission of dopaminergic receptor. As to the side-effects given by known drugs for treating schizophrenia are for example, in the case of phenothiazine-type drugs, the orthostatic hypotension and hypersedation on the basis of strong a-blocking activity; and in the case of drugs having strong activity for blocking neurotransmission of dopaminergic receptor, the side-effects are so-called extrapyramidal tract syndromes such as catalepsy, akathisia, dystonia and the like caused by the blocking neurotransmission of dopaminergic receptor in the atriate body.

53 The objects of the invention in US 528 are said to be as follows:

(1) to provide novel carbostyril derivatives and salts thereof;

(2) to provide processes for preparing said carbostyril derivatives and salts thereof; and

(3) to provide a pharmaceutical composition for treating schizophrenia.

54 The claims in US 528 include the following claims:

16. A pharmaceutical composition for treating schizophrenia containing, as the active ingredient, a carbostyril compound or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof of claim 1 and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

17. The pharmaceutical composition of claim 16, wherein the carbostyril compound or salt thereof is [aripiprazole].

55 The primary judge noted that EP 141 contained a similar claim and that, in addition, EP 141 contained, in claim 32, a Swiss type claim directed to the use of aripiprazole for the preparation of a drug useful for the treatment of schizophrenia.

Serper

56 Serper is an article entitled “Novel Neuroleptics Improve Attentional Functioning Schizophrenic Patients: Ziprasidone and Aripiprazole” by Serper et al. This article was published in CNS Spectrums 2(8) (1997). Under the heading “Overview”, the authors state:

Attentional dysfunction has long been recognized as a core feature of schizophrenic (SZ) illness. It has been consistently found that SZ patients manifest significant deficits in their ability to sustain their attention over time, as well as their ability to focus their attention on target stimuli when distractors are present. SZ attentional deficits are found across all developmental periods and clinical states including in children at high risk for the disorder, acutely ill patients, and remitted outpatients. These cognitive deficits, however, have been shown to improve over the course of neuroleptic treatment.

Numerous studies have confirmed that SZ performance, particularly on the digit span distraction task (a measure of selective attention) and the Continuous Performance Test (CPT: a measure of sustained attention), is highly responsive to classical neuroleptic treatment. For example, Oltmanns et al found that neuroleptic-withdrawn SZ patients showed a significant decline in their selective attention performance on the digit span distraction task from their stabilized medication baseline. Additionally, SZ patients’ digit span attentional performance has been found to be associated with higher serum neuroleptic levels in patients who were receiving neuroleptic treatment.

…

The finding that antipsychotic drugs improve attentional processes has led researchers to hypothesize, in much the same way they did for psychotic symptoms, that dopamine (DA) dysfunction underlies SZ attentional deficits. A recent model, for example, postulated that SZ attentional impairment is attributable to hypodopaminergic functioning in the prefrontal regions of the cortex.

Novel neuroleptics hold great promise in achieving further significant improvement in SZ attentional functioning because they preferentially increase prefrontal DA activation. Few studies to date have examined SZ attentional functioning during the course of novel neuroleptic treatment. Therefore, we compared attentional functioning of SZ patients receiving either typical or novel neuroleptics (ie, aripiprazole or ziprasidone) at both medication-free baseline and 30 days after receiving novel or classical neuroleptic treatment. We hypothesized that SZ patients receiving novel neuroleptics would demonstrate significant improvement in attentional functioning compared with patients receiving typical neuroleptic treatment.

(Citations omitted.)

57 The primary judge found, and it is not in dispute, that the reference in these passages to “neuroleptic” treatment, is to treatment with antipsychotic drugs, and that the reference to “classical neuroleptic” is to typical antipsychotic drugs, and the reference to “novel neuroleptic” is to atypical antipsychotic drugs.

58 The primary judge said that Serper addressed a study involving the treatment of 21 patients who presented with an acute episode of schizophrenia. Five of the patients received aripiprazole and four received ziprasidone. The remaining 12 patients received an unidentified typical antipsychotic drug. The primary judge found that patients in both groups suffered chronic schizophrenia. In dealing with the results of the study, the authors state:

Consistent with the study hypothesis, the present results found that SZ patients receiving novel neuroleptic treatment showed superior performance in CPT reaction time and in digit span immediate recall compared with SZ patients receiving traditional neuroleptic therapy. The present study also found that all patients receiving classical or novel neuroleptic therapy showed significant improvement in selective and sustained attentional functioning. These results are consistent with past investigations examining SZ attentional improvement following typical neuroleptic treatment and further support the notion that SZ attentional impairment, like many SZ symptoms, is mediated by mesostriatal DA pathways.

(Citations omitted.)

59 The authors conclude as follows:

Overall, the present results suggest that enhanced attentional performance obtained while on novel neuroleptic medication may enable SZ patients to further advance their functioning in important life domains.

Saha

60 Saha is an article entitled “Safety and Efficacy Profile of Aripiprazole, A Novel Antipsychotic” by Saha et al. The article was published in 1999 in Schizophrenia Research 36(1-3). The article states that aripiprazole is a novel antipsychotic which was going through worldwide Phase 3 development. The article states that a unique feature of aripiprazole is its agonistic effect at presynaptic dopamine receptors with a postsynaptic dopamine D2 antagonistic effect. The article refers to a Phase 2 study which was a completed double-blind, four-week, placebo-and-haloperidol-controlled study conducted in a total of 307 acutely relapsing hospitalised schizophrenia patients. The article states:

In this study aripiprazole fixed doses of 2 mg, 10 mg, and 30 mg per day were administered. Based on the last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis, aripiprazole was superior to placebo in improving the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)‒total for each dose group, and the 30-mg dose showed significant effect also for PANSS-negative score. The related items of PANSS were clustered and were analysed (LOCF) to determine the effect of aripiprazole on the following dimensions: excitement, depression, and cognitive function. On each of these dimensions the aripiprazole doses showed improvement over baseline, starting from week 1 to the last visit. In addition, at last visit, improvement for excitement and depression was statistically significant compared to placebo for each aripiprazole dose group; and for cognition, the aripiprazole 30-mg dose also showed statistically significant improvement over placebo.

61 The primary judge said that PANSS is used to evaluate the severity of the symptoms of schizophrenia in patients, and the efficacy of medications used to treat schizophrenia. The scale includes a list of seven positive symptoms, seven negative symptoms and 16 general psychopathology symptoms. The primary judge then referred to the evidence before him and, in particular, the evidence of Professor Singh and Dr O’Dea. The authors of the Saha article expressed the following conclusion:

An impressive effectiveness and a favourable safety profile indicate that aripiprazole should be a substantial addition to the new generation antipsychotics.

62 Keefe is an article entitled “The Effects of Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs on Neurocognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Review and Meta-analysis” by Keefe et al. The article was published in Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 25, No 2 (1999).

63 The abstract in the article is as follows:

Cognitive deficits are a fundamental feature of the psychopathology of schizophrenia. Yet the effect of treatment on this dimension of the illness has been unclear. Atypical antipsychotic medications have been reported to reduce the neurocognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia. However, studies of the pattern and degree of cognitive improvement with these compounds have been methodologically limited and have produced variable results, and few findings have been replicated. To clarify our understanding of the effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia, we have (1) reported on newly established standards for research design in studies of treatment effects on cognitive function in schizophrenia, (2) reviewed the literature on this topic and determined the extent to which 15 studies on the effect of atypical antipsychotics met these standards, (3) performed a meta-analysis of the 15 studies, which suggested general cognitive enhancement with atypical antipsychotics, and (4) described the pharmacological profile of these agents and considered the pharmacological basis for their effects on neurocognition. Finally, we suggest directions for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

64 Keefe contains a discussion on the positive relationship between cognitive improvement and drugs that bind to serotonin receptors which “may facilitate or impair certain cognitive functions, depending on the location and subtype of the affected receptors”.

65 Serper is one of the 15 studies which were the subject of the meta-analysis performed by Keefe. Serper is referred to in the body of the article. Keefe reports that none of the 15 studies that were reviewed met all of the recently developed standards for the assessment of cognitive change in schizophrenia. It notes that most importantly, only three of the 15 studies used double-blind methodology.

66 Keefe drew the following conclusions from the meta-analysis and review of the studies:

Despite a conservative statistical approach, correcting the results of each study for the number of statistical comparisons made, the meta-analysis conducted in this study suggests that atypical antipsychotics, when compared with conventional antipsychotics, improve cognitive functions in patients with schizophrenia. Verbal fluency, digit-symbol substitution, fine motor functions, and executive functions were the strongest responders to novel antipsychotics. Attention subprocesses were also responsive; learning and memory functions were the least responsive.

Novelty

67 The primary judge noted that the respondent relied on each of EP 141/US 528, Serper and Saha as novelty-defeating.

68 The primary judge referred to the reverse infringement test and the need for a clear description of, or a clear direction, recommendation or suggestion to do or make, something that would infringe the patentee’s claim if carried out after the grant of the patentee’s patent, in order for the prior art to be anticipatory. There is no dispute about the accuracy of his Honour’s statements of principle.

69 The primary judge recorded the respondent’s submission to be as follows. The use of aripiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia, as taught in the relevant prior art documents, would have resulted, inevitably, in the treatment of a patient’s cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia, including in the circumstances referred to in claim 7 of the 722 Patent and, according to the teaching in the Patent, this would have involved the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. It followed (so the submission proceeds) that it is not necessary for any of the prior art documents to make reference to an association between the 5-HT1A receptor subtype and the treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia in order for the prior art document to constitute an anticipation.

70 The primary judge acknowledged that there were limitations on the “inevitable result” test, particularly where the invention claimed is a new method of medical treatment involving the administration of a known compound for a hitherto unknown and unexpected, but nevertheless useful, therapeutic use. In this context, his Honour referred to the influence of the decision of the Enlarged Board in MOBIL/Friction Reducing Additive (G02/88) [1990] EPOR 73 (“Mobil”) on the question of anticipatory disclosure in United Kingdom patent jurisprudence. In Mobil, the issue was the patentability of an additive for oil that was known for rust prevention in engines. The patentee was allowed to claim the use of the known additive for a new purpose, namely, friction reduction. The new purpose and the undisclosed technical effect was sufficient to confer novelty on the invention as claimed.

71 The primary judge then referred to two United Kingdom cases which had identified limits to the Mobil principle (Baker Norton; Actavis UK Ltd v Janssen Pharmaceutical NV [2008] FSR 35 (“Actavis”)). More information about the old use (Baker Norton at [277] per Jacob J) or merely explaining the mechanism which underlies a use already described in the prior art (Actavis at [99] per Floyd J) is not of itself sufficient to give rise to novelty. In Baker Norton, Jacob J said (at 277):

It is implicit in what Laddie J said, I think, that Mobil has its limits. It should be remembered that Mobil was treated as a case where the new use was different from the old. Perhaps a clearer example is BASF/Triazole derivatives (T231/85) [1989] OJ EPO 74 of the discovery that a particular compound (previously used for influencing plant growth) also controlled fungi. One can imagine cases where it was used for one purpose or the other. The purposes do not necessarily overlap. That is simply not the case here. All you have is more information about the old use. In due course no doubt more information about the exact mode of action of taxol will emerge. No-one could obtain a patent for its use simply by adding “for” at the end of the claim and then adding the newly discovered details of the exact mode of action.

In Actavis, Floyd J said (at [99]):

In my judgement, merely explaining the mechanism which underlies a use already described in the prior art cannot, without more, give rise to novelty. In MOBIL, the technical effects which underlay the new and old uses were different and distinct. So also in Mr Alexander’s example about disease X and disease Y. It is not the case that every discovery about the mode of action of a drug can be translated into a new purpose and claimed as such.

72 The primary judge said that these United Kingdom cases provided valuable insights in analysis which assist in considering closely similar questions arising under Australian patent law.

73 The primary judge found that EP 141/US 528 disclosed the following:

(1) aripiprazole, amongst other carbostyril derivatives, was used as a drug for the treatment of schizophrenia generally and it was a useful alternative to earlier generation drugs, including three mentioned in claims 1 and 7, being chlorpromazine, haloperidol and sulpiride, including in the chronic period of the illness; and

(2) at the priority date, the person skilled in the art would have understood that when EP 141/US 528 refer to aripiprazole’s utility in treating negative symptoms, those symptoms included at least some of the symptoms which claims 1 and 7 of the 722 Patent characterise as cognitive impairment.

74 The primary judge found that EP 141/US 528:

(1) did not disclose that aripiprazole is a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor;

(2) makes no reference to 5-HT1A receptors or the action of aripiprazole on 5-HT1A receptors or the serotonergic system more generally; and

(3) makes no express reference to switching or the use of aripiprazole as third line treatment where a patient’s cognitive impairment has failed to respond to other identified antipsychotics.

75 The primary judge said that if he followed the reasoning in the United Kingdom cases of Baker Norton and Actavis, he would conclude that neither the association feature nor the failure to respond feature were sufficient to give rise to novelty. He considered that it was appropriate to follow the reasoning in those cases. The essence of his Honour’s approach was to hold that (as he put it) claim 7 merely partitioned something that is old under the guise that the part it takes and claims as an invention is new. He said that claim 7 is directed to an old therapeutic use, not a new one. His Honour said that claim 7 claims a then known substance, aripiprazole, for its then known therapeutic purpose, the treatment of schizophrenia, with only some of the symptoms of schizophrenia and only some occasions of use referred to in the claim. His Honour said that the same was true of claim 1. His Honour said the association feature was new information about the disorders, but that the disorders were part of the then known symptoms of schizophrenia. The association feature was no more than an elucidation of the action of the known carbostyril compounds, including aripiprazole, in treating schizophrenia, and a contribution to knowledge of the possible aetiology of those particular symptoms. These “accretions to knowledge” without more, do not provide novelty of invention (at [321]).

76 The primary judge said that, in any event, he did not accept that the knowledge provided by the association feature defined a free-standing essential feature of the invention which is to be considered as meaningfully adding to the identification of the specific forms of cognitive impairment referred to. The association feature could not confer novelty (at [322]).

77 The primary judge held that the failure to respond feature did not confer novelty. The disclosures in EP 141/US 528 did not limit the use of carbostyril compounds, including aripiprazole, to a particular line of treatment and there would be no reason why a person skilled in the art at the priority date and therefore aware that switching was a feature of clinical practice would read the disclosures down.

78 The primary judge tested his conclusion by asking whether EP 141/US 528 contained a clear description of, or a clear direction, recommendation or suggestion to do or make, something that would infringe the patentee’s claim if carried out after the grant of the patentee’s patent. He answered that question in the affirmative (at [326]).

Serper

79 We do not need to set out in any detail his Honour’s conclusions in relation to Serper. His Honour concluded that it was an anticipation and the important point is that his reasoning in relation to the association feature and the failure to respond feature was materially the same as it was in relation to EP 141/US 528 (at [332]).

Saha

80 The primary judge first considered a contention by the appellants that Saha did not disclose the effectiveness of treating cognitive impairment. He rejected that contention for the reasons he gave and which we do not need to repeat. Thereafter, he applied similar reasoning in relation to Saha as he had in relation to EP 141/US 528 (at [337]).

Inventive Step

81 The primary judge held that the invention as claimed lacked an inventive step, having regard to the common general knowledge at the priority date and Saha, or Keefe and Serper, treated as combined information. It is not necessary to summarise in detail the primary judge’s reasons for reaching this conclusion because (subject to one matter which we will identify) the appellants’ grounds of challenge to his reasons in relation to inventive step are limited to the consequences of his “flawed” construction. As we have said, the complaint by the appellants that the skilled person would not have combined Keefe and Serper was abandoned during their oral submissions.

82 The primary judge set out the respondent’s formulation of the Cripps question in relation to claim 7 as follows:

[W]hether the person skilled in the art (a team including a psychiatrist and if necessary the medicinal chemist and pharmacologist suggested by the Applicant), in light of the common general knowledge combined with s 7(3) information would have been led as a matter of course to try the method as claimed in claim 7 (to administer aripiprazole) in the expectation it would have been beneficial in treating a patient with chronic or treatment-resistant schizophrenia (or one of the other disorders listed in the claim) with cognitive impairment symptoms that had failed to respond to two or more of the other listed antipsychotics.

83 He said that the appellants formulated the Cripps questions with reference to both claims 1 and 7 and that he did not think that, as a matter of substance, the appellants’ formulations differed in any way that would lead to a materially different inquiry.

84 We are not sure his Honour is correct in viewing the appellants’ Cripps questions as being materially the same as the respondent’s (see Appellants’ Closing Submissions paragraphs 194 and 195), but at all events, the appellants submit on the appeal that the Cripps question in relation to claim 7 should have been as follows:

Would the notional research group at 29 January 2001, in the light of the common general knowledge alone or combined with s 7(3) information, directly be led as a matter of course to try aripiprazole for a method of treating a patient suffering from:

(a) disorders of the central nervous system associated with [the] 5-HT1A receptor sub-type,

(b) which disorder

(i) is selected from cognitive impairment caused by treatment-resistant schizophrenia, cognitive impairment caused by inveterate schizophrenia, or cognitive impairment caused by chronic schizophrenia, and

(ii) fails to [respond] to antipsychotic drugs selected from chlorpromazine, haloperidol, sulpiride, fluphenazine, perphenazine, thioridazine, pimozide, zotepine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or amisulpride,

comprising administering to said patient a therapeutically effective amount of aripiprazole, in the expectation that it might well produce a useful result?

(Emphasis in original.)

85 The primary judge said that the invention is for the treatment of at least one of the identified forms of cognitive impairment and necessarily, for a medicament containing aripiprazole that had been produced for such treatment. Again, he made the point that the discovery that aripiprazole’s action at the 5-HT1A receptor is the reason or one of the reasons for that utility cannot provide an inventive step when Saha had already disclosed that aripiprazole was useful in treating cognitive impairment in patients suffering from chronic schizophrenia. His Honour repeated the point he had previously made that this discovery provided no more than an elucidation of why aripiprazole was useful and, perhaps, an explanation of why it had the beneficial effects reported in Saha (at [439]). His Honour’s analysis in relation to Serper/Keefe was relevantly the same (at [458]).

86 The appellants’ submission is that their construction of the claims is correct and it means that their formulation of the Cripps question rather than that adopted by the primary judge is the correct one. The appellants’ submission is that the correct formulation of the Cripps question raised a specific problem and that there was no evidence before the primary judge that any person skilled in the art would try aripiprazole, or even if they might have, that they would have done so with any expectation that it might well be useful.

87 As far as the failure to respond feature is concerned, the primary judge rejected the suggestion that there was anything inventive about the feature. His Honour made findings as to the relevant common general knowledge at the priority date which were based on the respondent’s submissions and which he records as not being contested by the appellants. The common general knowledge at the priority date included the following:

(1) that some patients suffered from refractoriness in which positive, negative and neurocognitive symptoms did not respond to treatment with antipsychotics;

(2) that a number of treatment-resistant and treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients displayed symptoms that did not respond adequately to a variety of known effective classes and doses of typical or atypical antipsychotic drugs;

(3) the switching of patients undergoing treatment with antipsychotic drugs to other atypical antipsychotic drugs;

(4) switching antipsychotics in an attempt to improve cognitive impairment in schizophrenic patients; and

(5) switching the medication of a patient with chronic or treatment-resistant schizophrenia, where the patient’s symptoms and signs of schizophrenia had failed to respond to two or more existing antipsychotics.

88 The primary judge concluded that, in light of that common general knowledge, a person skilled in the art and with the benefit of the information in Saha (at [440]) or Keefe/Serper (at [458] and [466]) would have been directly led as a matter of course to try aripiprazole as a method of treatment, with the expectation that it might well be useful, where the patient’s cognitive impairment had failed to respond to previous medication. The invention as claimed, therefore, lacked an inventive step.

Issues on the Appeal

89 As we have said, the appellants contend that the primary judge made five errors. The first alleged error relates to the primary judge’s construction of the association feature and the failure to respond feature. The second and third alleged errors relate to the primary judge’s construction of the association feature. The first three alleged errors, insofar as they relate to the association feature, overlap and it is convenient to deal with them together.

90 The first alleged error is that the primary judge gave no effective meaning to the association feature and, thus, notionally put it to one side. The second alleged error is that the primary judge gave no effective meaning to the association feature because he proceeded on the premise that all of the disorders named in the claims are disorders of the central nervous system, associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype when (so the appellants contend) that premise was contrary to the teachings of the 722 Patent and the evidence. The third alleged error is that the primary judge should have resolved the question of whether, and the extent to which, the disorders named in the claims are in fact “disorders of the central nervous system associated with [the] 5-HT1A receptor subtype” and that he should have done that by reference to the “extensive body of scientific evidence put forward by both parties”.

91 As we understand it, the steps in the appellants’ argument are as follows. First, the claims should have been construed such that the association feature was an essential feature or integer of the claims. The reason for this is that not all cases of cognitive impairment caused by the disorders named in the claims are disorders of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. Contrary to his Honour’s conclusion that the teaching in the 722 Patent was to the effect that the forms of cognitive impairment were disorders of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype, in fact, the teaching in the 722 Patent did not proceed on the basis that all forms of cognitive impairment resulting from the named disorders are disorders of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. Secondly, even if the teachings in the 722 Patent are not as the appellants contend or not necessarily as the appellants contend, the primary judge needed to determine the factual question of whether all forms of cognitive impairment resulting from the named disorders are disorders associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. The appellants contend that the teachings in the 722 Patent are only one item of evidence, a point made by the High Court, albeit in the context of admissions as to prior art and common general knowledge in Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd [No 2] [2007] HCA 21; (2007) 235 CLR 173 at [105]-[111]. The appellants contend that the primary judge needed to decide the question otherwise his construction of the claims would proceed on an incorrect factual premise. This, they contend, is in fact what happened in this case. Thirdly, the appellants contend that the primary judge should have decided the factual question in the negative, that is to say, that not all forms of cognitive impairment resulting from the named disorders are disorders of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. Had the primary judge addressed the factual question and had he decided in the way in which the appellants contend that he should have decided it, then he would have construed the claims so that the association feature was an essential feature or integer. Furthermore, had the primary judge identified the association feature as an essential feature or integer, then the prior art would not be novelty defeating and the Cripps question (as reformulated by the appellants), would be answered in the negative. The final step in the appellants’ argument is that any difficulty for them in proving infringement if the association feature is an essential feature is more apparent than real. In view of the restriction in the claims to the use of aripiprazole as a third or later line treatment (assuming the primary judge’s construction) the effectiveness of aripiprazole as such treatment after other antipsychotic drugs which target different receptors have been tried is sufficiently likely to be due to an association between the disorder and the 5-HT1A receptor subtype as to justify an injunction.

92 The arguments advanced by the appellants on the appeal involve a departure from the way in which the appellants conducted their case in the Court below. We accept that in the Court below, the appellants argued for a broad meaning to be given to the word “association” in the claims, but nevertheless they did argue that there is a relationship between the disorders named in the claims and the 5-HT1A receptor subtype, albeit that it is sufficient that it is “implicated in, or plays a role in, the disorders” (at [141]). The respondent’s case below was that the association or link or connection could not be established. The appellants’ submission on the appeal seems to be raising a third alternative, that is, that the association exists in some cases and not in others. We would also make the observation that it is hardly surprising that the primary judge reached the view that the teachings of the 722 Patent support the conclusion that the claims take the particular forms of cognitive impairment as being disorders of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype, having regard to the appellants’ arguments in the Court below.

93 The approach to the construction of claims in a patent specification is well-established.

94 We start with the well-known passage in the speech of Lord Russell of Killowen in Electric and Musical Industries, Ltd and Boonton Research Corporation, Ltd v Lissen, Ltd and another (1939) 56 RPC 23 (“EMI v Lissen”) at 39:

The function of the claims is to define clearly and with precision the monopoly claimed, so that others may know the exact boundaries of the area within which they will be trespassers. Their primary object is to limit, and not to extend, the monopoly. What is not claimed is disclaimed. The claims must undoubtedly be read as part of the entire document, and not as a separate document. Nevertheless, the forbidden field must be found in the language of the claims, and not elsewhere. It is not permissible, in my opinion, by reference to some language used in the earlier part of the specification to change a claim which by its own language is a claim for one subject-matter into a claim for another and a different subject-matter, which is what you do when you alter the boundaries of the forbidden territory. A patentee who describes an invention in the body of a specification obtains no monopoly unless it is claimed in the claims. As Lord Cairns LC said, there is no such thing as infringement of the equity of a patent (Dudgeon v Thomson, L.R. App Cas. 34).

95 In Martin v Scribal Proprietary Limited (1954) 92 CLR 17 at 97, Taylor J said:

Plain language must be given its plain meaning, and clear words in a claim must not be tortured into an unnatural meaning by importing passages from the body of the specification. (See Lord Russell’s speech in Electrical & Musical Industries, Ltd. v Lissen, Ltd.). The claims also must be construed without an eye on the alleged infringer’s acts. (So said Greene LJ in R.C.A. Photophone Ltd. v Gaumont British Picture Corporation). On the other hand, it is right to construe a claim with an eye benevolent to the inventor and with a view to making the invention work — this is an application of the old doctrine ut res magis valeat quam pereat — and it is illustrated in Nobel’s Case; and, where the language of a claim is obscure or doubtful, the doubt may sometimes be resolved by referring to words in the body of the document to explain it. This is known as the dictionary principle. (See Lord Haldane’s Speech in British Thomson- Houston Coy., Ltd. v Corona Lamp Works, Ltd.).

(Citations omitted.)

(This passage was referred to with approval by Gummow J in Sartas No 1 v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd and Another (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 486.)

96 The Full Court in Kinabalu Investments at [45] provided the following summary of the applicable principle:

• a specification should be given a purposive construction rather than a purely literal one;

• the hypothetical addressee of the specification is the non inventive person skilled in the art before the priority date;

• the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning the hypothetical addressee would attach to them, both in the light of the addressee’s own general knowledge and in the light of what is disclosed in the body of the specification;

• as a general rule, the terms of the specification should be accorded their ordinary English meaning;

• evidence can be given by experts on the meaning those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases, and on unusual or special meanings given by such persons to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning;

• however, the construction of the specification is for the court, not for the expert. In so far as a view expressed by an expert depends upon a reading of the patent, it cannot carry the day unless the court reads the patent in the same way.

97 Lord Tomlin made the following observations about the proper role of expert evidence in determining issues of construction in British Celanese, Ltd v Courtaulds, Ltd (1935) 52 RPC 171 (“British Celanese”) at 196:

The area of the territory in which in cases .of this kind an expert witness may legitimately move is not doubtful. He is entitled to give evidence as to the state of the art at any given time. He is entitled to explain the meaning of any technical terms used in the art. He is entitled to say whether in his opinion that which is described in the specification .on a given hypothesis as to its meaning is capable of being carried into effect by a skilled worker. He is entitled to say what at a given time to him as skilled in the art a given piece of apparatus or a given sentence on any given hypothesis as to its meaning would have taught or suggested to him. He is entitled to say whether in his opinion a particular operation in connexion with the art could be carried out and generally to give any explanation required as to facts of a scientific kind.

He is not entitled to say nor is Counsel entitled to ask him what the Specification means, nor does the question become any more admissible if it takes the form of asking him what it means to him as an engineer or as a chemist. Nor is he entitled to say whether any given step or alteration is obvious, that being a question for the Court.

98 The appellants began their submissions by referring to the fact that, although it is open to a court to hold that an express feature is not an essential feature, that in fact is done very rarely and the Court must be cautious in holding that an express feature is an inessential feature or integer (Blanco White TA, Patents for inventions and the protection of industrial designs (5th ed, Stevens, 1983) at [2-111]); Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Ltd v Gambro Pty Ltd and Another [2005] FCAFC 220; (2005) 67 IPR 230 at [87]; Root Quality at [43] per Finkelstein J; EMI v Lissen at 39 per Lord Russell of Killowen). We do not question that proposition, but it seems to us that it really is a question of characterisation. It might be one thing to say that a limitation is not essential. However, it seems to us that to say something is descriptive or an addition to existing knowledge is in a different category. Cases such as Baker Norton and Actavis make that clear. The other point to note is that the primary judge did not ignore the association feature. His Honour referred to the feature as part of the description of an essential feature, being the disorders to be treated. The disorders and the association with the identified receptor defined one essential feature, they are to be read together and not treated as separate features or integers (at [145]).

99 The starting point in a construction issue is the words of the claims. As we understand it, the appellants’ case is that the claims should be read so as to recognise two classes of cognitive impairment caused by the forms of schizophrenia identified, namely those associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype and those not associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype. We do not think that that is a construction of the claims which immediately suggests itself, having regard to the structure of the claims. The wording of the claims suggests to us that (to take one example) treatment-resistant schizophrenia resulting in (i.e., as a symptom) cognitive impairment is a disorder of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype and not that the reference to association with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype is intended as a limitation. In other words, we would read the reference as descriptive of the disorders identified. Had the intention been to specify a further limitation or restriction on the disorders which are the subject of the claims, then one might have expected to see an additional subparagraph rather similar to the way the appellants seek to formulate the Cripps question (at [84] above). The wording of the claims supports the primary judge’s construction, but it is also appropriate to consider the teachings of the 722 Specification.

100 The teachings in the 722 Specification are as follows:

(1) The invention as claimed is said to relate to a method of treating a patient suffering from a disorder of the central nervous system associated with the 5-HT1A receptor subtype.

(2) The related art is said to include US Patent No 5, 006, 528 and European Patent No 367, 141.

(3) It has been reported that aripiprazole binds with high affinity to dopamine D2 receptors and with moderate affinity to dopamine D3 and 5-HT7 receptors and that aripiprazole possesses presynaptic dopaminergic autoreceptor agonistic activity, postsynaptic D2 receptor antagonistic activity, and D2 receptor partial agonistic activity.

(4) It has not been reported that compounds in the invention as claimed have agonistic activity at 5-HT1A receptor subtype.

(5) It has been reported that:

- therapeutic interventions using 5-HT1A receptor ligands may be useful drug treatments for alcohol abuse;

- 5-HT1A agonist drugs may be useful for the treatment and/or prophylaxis of disorders associated with neuronal degeneration resulting from ischemic events in mammals;

- 5-HT1A receptor hypersensitivity could be the biological basis for the increased frequency of migraine attack in stressful and anxious conditions;

- that another compound that is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist has neuroprotective, anxiolytic and anti depressant-like effects in animal models;

- that 5-HT1A receptor agonists appear to be broad spectrum antiemetic agents.

(6) Serotonin plays a role in several neurological and psychiatric disorders.

(7) Buspirone which is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist is efficacious in treating a variety of symptoms associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (“ADHD”), and that combined use of a D2 receptor agonist and 5-HT1A agonist provides effective treatments for ADHD and Parkinson’s disease.

(8) That 5-HT1A agonists or partial agonists have been found to be effective in the treatment of:

- cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease or senile dementia;

- Alzheimer’s disease by improving memory;

- short term memory in patients in need of treatment;

- depression and certain primary depressive disorders;

- motor disorders such as neuroleptic induced parkinsonism and extrapyramidal symptoms.

(9) Aripiprazole, because of its potent, partial agonistic activities at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors, can be used to manage psychosis in geriatric patients, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease or senile dementia, and may improve extrapyramidal symptoms.

(10) Typical antipsychotic drugs, such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol, are effective in treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia which include hallucinations, delusions and the like. Atypical antipsychotic drugs, such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine have other activities in addition to their DA-receptor blocking activities and less extrapyramidal side effects. In contrast to typical antipsychotic drugs, it has been reported that atypical antipsychotic drugs are more effective against the negative symptoms and cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia.

(11) There are patients who have schizophrenia who do not respond adequately to a variety of known effective classes and doses of typical or atypical antipsychotic drugs (treatment-resistant, treatment-refractory, inveterate or chronic schizophrenic patients).

(12) Cognitive impairment exists separately from the psychic symptoms in a schizophrenic individual and may disturb the socially adaptable behaviour of these individuals. Therefore, medical treatment is quite important.

(13) Clozapine is an antipsychotic drug that is effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia and it has been reported to be effective against cognitive impairments in treatment-resistant schizophrenics. The 5-HT1A receptor has been demonstrated to play a role in the therapeutic efficacy of clozapine against treatment-resistant schizophrenia and cognitive impairments.

(14) There is a passage which refers to the role of the 5-HT1A receptor in treatment-resistant schizophrenia and cognitive impairments. Although lengthy, it is important, and we set it out in full:

Further, in accordance with progress in molecular pharmacology, it is clearly understood that 5-HT1A receptor agonistic activity or 5-HT1A receptor partial agonistic activity plays an important role in treatment-resistant schizophrenia and cognitive impairments (A. Newman-Tancredi, C. Chaput, L. Verriele and M. J. Millan: Neuropharmacology, Vol. 35, pp. 119, (1996)). Additionally, it was reported that the number of 5-HT1A receptor is increased in the prefrontal cortex of chronic schizophrenics who were classified treatment-resistant. This observation was explained by a compensatory process where by the manifestation of severe symptoms of chronic schizophrenia are a result of impaired neuronal function mediated by hypofunctional 5-HT1A receptors (T. Hashimoto, N. Kitamura, Y. Kajimoto, Y. Shirai, O. Shirakawa, T. Mita, N. Nishino and C. Tanaka: Psychopharmacology, Vol. 112, pp S35, (1993)). Therefore, a lowering in neuronal transmission mediated through 5-HT1A receptors is expected in treatment-resistant schizophrenics. Thus the clinical efficacy of clozapine may be related to its partial agonist efficacy at the 5-HT1A receptors (A. Newman-Tancredi, C. Chaput, L. Verriele and M. J. Millan: Neuropharmacology, Vol. 35, pp. 119, (1996)). 5-HT1A receptor agonistic activity may be related to the clinical effects of clozapine, and this hypothesis is supported by a positron emission tomography study in primates which showed that clozapine interacts with brain 5-HT1A receptors at a therapeutically effective dose (Y.H. Chou, C. Halldin and L. Farde: Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol., Vol. 4 (Suppl. 3), pp. S130, (2000)). Furthermore tandospirone, which is known as a selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist, improved cognitive impairments in chronic schizophrenic patients (T. Sumiyoshi, M. Matsui, I. Yamashita, S. Nohara, T. Uehara, M. Kurachi and H.Y. Meltzer: J. Clin. Pharmacol., Vol. 20, pp. 386, (2000)). While, in animal tests, all reports do not always suggest that 5-HT1A receptor agonist activity may be related to cognitive impairment, however, 8-OH-DPAT (8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin), which is known as a selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist, improves learning and memory impairments induced by scopolamine known as a muscarinic receptor antagonist, suggesting a relationship between 5-HT1A receptor agonistic activity and improvements in cognitive impairments (M. Carli, P. Bonalumi, R. Samanin: Eur. J. Neurosci., Vol. 10, pp. 221, (1998); A. Meneses and E. Hong: Neurobiol. Learn. Mem., Vol. 71, pp. 207, (1999)).

(15) Two atypical antipsychotic drugs which were marketed after clozapine are risperidone and olanzapine and as to those drugs:

(a) it has been reported that they improve treatment-resistant schizophrenia or cognitive impairments in treatment-resistant schizophrenics;

(b) in contrast to clozapine, which it had been reported was moderately effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia, risperidone and olanzapine were not consistently superior to typical antipsychotic drugs in their effectiveness against treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Thus, risperidone and olanzapine bind with lower affinity to human 5-HT1A receptors at clinical effective doses.

(Our emphasis.)

(16) Therefore, at present, it is understood that clozapine is effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

(17) The Patent provides:

As explained above 5-HT1A receptor agonistic activity is important for improving treatment-resistant schizophrenia or cognitive impairment caused by treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

(18) Clozapine, although effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia, has severe side-effects and the development of a safe antipsychotic drug with potent, full or partial agonist activity at 5-HT1A receptors is “earnestly desired”.

(19) Aripiprazole binds with a high affinity and displays a potent, partial agonist activity at the 5-HT1A receptors and it has higher intrinsic activity (about 68%) as compared with that of clozapine. Therefore, the compound in the present invention has a 5-HT1A receptor agnostic activity that is more potent than the agnostic activity of clozapine.

(20) Aripiprazole may be “a potent and safer drug therapy” and “a potent and highly safe drug therapy” where a patient fails to respond to other typical or atypical antipsychotic drugs and there are 12 drugs listed.