FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Compton v Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 106

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | RAMSAY HEALTH CARE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave to appeal be granted.

2. The appeal be treated as instituted and heard instanter.

3. The appeal be allowed.

4. Orders 1 and 2 of the orders made on 3 December 2015 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be ordered that:

(a) The separate question (raised by the interim application filed 8 July 2015) whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment of the Supreme Court of New South Wales upon which the creditor’s petition is based, be determined in the affirmative.

(b) The interim application otherwise be dismissed.

(c) The costs of the interim application be reserved.

5. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the application for leave to appeal and the appeal.

6. If either party seeks a variation of orders 4(c) or 5 above, written notice be given to the Court and the other party within two (2) business days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

1 It is beyond doubt that a court exercising jurisdiction in bankruptcy has a discretion to accept a judgment as satisfactory proof of a debt owed to a creditor petitioning for a sequestration order. In the present case, the primary judge determined as a separate question whether he should ‘go behind’ the judgment and inquire into the debt himself. His Honour decided not to and the debtor seeks leave to appeal. Broadly speaking, two issues are raised by the draft notice of appeal: first, whether his Honour erred by finding that the discretion to ‘go behind’ the judgment was “not enlivened”, and second, whether he erred in concluding that, if it were, the discretion should not be exercised in the debtor’s favour.

Overview

2 On 4 June 2015, Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Ltd (Ramsay Health Care) filed a creditor’s petition in this Court seeking a sequestration order under s 43 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Bankruptcy Act) against the estate of Adrian John Compton. The act of bankruptcy relied upon was that Mr Compton had failed to comply with the requirements of a bankruptcy notice. The bankruptcy notice required payment by Mr Compton of a judgment of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in favour of Ramsay Health Care in the amount of $9,810,312.

3 The Supreme Court judgment arose from a proceeding in which Ramsay Health Care sued Mr Compton for $9,810,312 on a guarantee of the obligations of Compton Fellers Pty Ltd (in liquidation) which had traded as MediChoice (MediChoice). In that proceeding, Mr Compton did not dispute the quantum of the claim. Rather, he contended that, although he had signed certain pages, those pages did not pertain to the guarantee but were signed as stand-alone documents intended to signify his assent to a different proposed guarantee. Mr Compton’s defence also included a plea of non est factum because, as it was put by his counsel at the trial, the transaction to which he committed himself was radically different from the one he believed he was entering into, being a guarantee which would not expose him to personal liability for amounts which might become due by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care under an agreement between those companies. The Supreme Court rejected each of Mr Compton’s contentions and gave judgment for Ramsay Health Care against Mr Compton in the amount claimed: Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Limited v Adrian Compton [2015] NSWSC 163.

4 Mr Compton did not pay the judgment debt and consequently Ramsay Health Care served him with a bankruptcy notice. He failed to comply with the bankruptcy notice within the time stipulated in the notice and consequently Ramsay Health Care filed its petition.

5 In the proceeding in this Court, Mr Compton asked the Court to separately determine whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment. A hearing took place which was, in effect, the hearing of the separate question. The primary judge answered that question in the negative.

6 Mr Compton has applied for leave to appeal. It was ordered that the application for leave to appeal, and any appeal, be heard concurrently.

7 For the reasons that follow, the application for leave to appeal should be granted and the appeal allowed. In summary, the evidence before the primary judge established, and Ramsay Health Care conceded, that there was an “open question” whether MediChoice in fact owed any money to Ramsay Health Care and thus whether Mr Compton owed a debt to Ramsay Health Care pursuant to the guarantee. In these unusual circumstances, there were substantial reasons for questioning whether behind the judgment there was in ‘truth and reality’ a debt owing to Ramsay Health Care and thus the question whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment should have been answered in the affirmative.

The creditor’s petition

8 The creditor’s petition stated that Mr Compton owed Ramsay Health Care the amount of $9,810,312 for judgment obtained pursuant to an order made by the Supreme Court of New South Wales. It was stated that Mr Compton had failed to comply within the required time with the requirements of a bankruptcy notice or to satisfy the Court that he had a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand equal to or more than the sum claimed in the bankruptcy notice, being a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand that he could not have set up in the action in which the judgment referred to in the bankruptcy notice was obtained.

9 The bankruptcy notice required payment within 21 days of a judgment debt of $9,810,312 payable by Mr Compton to Ramsay Health Care as ordered by the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

10 Mr Compton filed a notice dated 7 July 2015 stating grounds of opposition to the creditor’s petition. The notice stated that Mr Compton intended to oppose the creditor’s petition on the following grounds:

1. Contrary to section 52(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) no debt is or was really owed by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care] because the judgment is not founded on a debt that in truth and reality was or is owed by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care];

2. Further, to prevent a miscarriage of justice the Court should exercise its discretion to go behind the judgment upon which the Creditor’s Petition is based and consider whether the amount of the claimed debt as a whole is actually owed by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care];

3. The claimed debt is pursuant to a guarantee given by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care] in respect of the obligations of [MediChoice] to [Ramsay Health Care], but in reality no money is owed by [MediChoice] to [Ramsay Health Care].

4. In light of 1 and 3 above, [Ramsay Health Care] should not have entered judgment against [Mr Compton] in the Supreme Court of NSW proceedings number 2014 / 164906 for the amount of the judgment, and at all, because in truth and reality no money was owing by [MediChoice] to [Ramsay Health Care] and [Ramsay Health Care] should have been aware of that at the time final judgment was entered against [Mr Compton] in those Supreme Court proceedings or some earlier time.

The interim application

11 On 8 July 2015, Mr Compton filed an interim application. The orders sought in the interim application included:

1. Pursuant to rule 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), an order that there be a separate determination of the question of whether the Court should exercise its discretion to go behind the judgment upon which the Creditor’s Petition in this proceeding is based and consider whether the amount of the claimed debt as a whole is actually owed by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care] on the basis that it is not owed by [MediChoice] to [Ramsay Health Care];

2. Further, and in the alternative, an order that the Court exercise its discretion to go behind the judgment upon which the Creditor’s Petition in this proceeding is based and consider whether the amount of the claimed debt as a whole is actually owed by [Mr Compton] to [Ramsay Health Care] on the basis that it is not owed by [MediChoice] to [Ramsay Health Care] …

12 The interim application also sought an order for the production of a report prepared by KPMG regarding the question of what moneys were owing as between MediChoice (which was in liquidation) and Ramsay Health Care, and leave to issue a subpoena, but these aspects of the interim application were not pursued at the hearing before the primary judge and can be put to one side.

13 Although the interim application sought an order that there be a separate determination of a question as set out above, there does not appear to have been any formal determination of whether the question should be determined separately (cf Wolff v Donovan (1991) 29 FCR 480 at 486-487 per Lee and Hill JJ). But both parties proceeded on the basis that the question whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment would be decided separately and filed affidavit material and made submissions at the hearing before the primary judge directed to answering that question only. In other words, both parties approached the matter on the basis that this was a preliminary investigation into whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment and that, if the question were answered in the affirmative, there would be a second hearing at which further evidence would be adduced and witnesses cross-examined as to the moneys owing as between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care (cf Corney v Brien (1951) 84 CLR 343 at 358 per Fullagar J). In the event, the primary judge determined the question in the negative.

14 In support of the interim application, Mr Compton relied on four affidavits of Anna Stevis, a former director of MediChoice; two affidavits of Richard Albarran, one of three joint liquidators of MediChoice; and an affidavit of David Ingram, another one of the liquidators of MediChoice. In opposition to the interim application, Ramsay Health Care filed an affidavit of Caitlin Murray, a solicitor, and an affidavit of Michael Hirner, the Group Financial Controller for Ramsay Health Care. None of the deponents was cross-examined.

15 Ms Murray’s affidavit provided details and documents relating to the Supreme Court proceeding. The substance of her evidence was as follows.

16 The Supreme Court proceeding was commenced in 2014 by Ramsay Health Care against MediChoice and Mr Compton. MediChoice was subsequently placed into voluntary administration and then liquidation and did not take an active role in the proceeding. In his Commercial List Response, Mr Compton did not put quantum in issue. Prior to trial, Mr Compton served (amongst other things) an affidavit of Ms Stevis sworn on 21 November 2014 (Stevis Supreme Court Affidavit) and an affidavit he had sworn himself. The Supreme Court proceeding was heard on 18, 19 and 23 February 2015. Mr Compton was represented by solicitor and counsel. At the hearing, Ramsay Health Care relied on a certificate of debt which stated that the amount owing under the guarantee was $9,810,312. The only evidence which was read by Mr Compton was Mr Compton’s affidavit. In other words, the Stevis Supreme Court Affidavit was not read. No submissions were made in relation to the quantum of the alleged debt.

17 A copy of the Supreme Court judgment was exhibited to Ms Murray’s affidavit. As set out in the judgment, Ramsay Health Care sued Mr Compton for the amount of the alleged debt pursuant to a guarantee and indemnity which Ramsay Health Care claimed Mr Compton provided in respect of the obligations of MediChoice under a distribution and group purchasing agreement (the Agreement).

18 Ramsay Health Care alleged that on 8 November 2012, Mr Compton bound himself as guarantor in its favour on the terms of a written instrument entitled, Guarantee and Indemnity (the Guarantee). Clause 3.1 of the Guarantee provided that the guarantor irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed to Ramsay Health Care the payment of the Guaranteed Money on time and in accordance with the Agreement. “Guaranteed Money” was defined as meaning all money that MediChoice was or may be liable to pay Ramsay Health Care on any account whatever under, in relation to or arising from MediChoice’s performance, or purported performance, of its obligations under the Agreement. On 8 November 2012, Mr Compton appended his signature to a document headed, Signing page. Ramsay Health Care itself later signed an electronically transmitted copy of the same page bearing Mr Compton’s (electronically transmitted) signature. On 28 November 2012, Mr Compton appended his signature to a second signing page in the same form as the 8 November 2012 version.

19 Ramsay Health Care claimed that by his signatures Mr Compton bound himself to the Guarantee. Mr Compton admitted signing but denied that his signature on the signing pages was assent to the Guarantee because, he said, the signing pages did not pertain to the Guarantee but were signed as stand-alone documents intended to signify his assent to a different proposed guarantee under which he would not incur any personal liability to Ramsay Health Care.

20 The judge, Hammerschlag J, noted that “[q]uantum is not in dispute” and that counsel for Mr Compton ultimately articulated Mr Compton’s defence as follows. First, he denied that the signing pages pertained to, or were connected with, the Guarantee transmitted to him on 7 November 2012. Second, he pleaded non est factum on the footing that (if his signatures did pertain to the Guarantee) the transaction to which he was committing himself was radically different from the one he believed he was entering into, namely a guarantee which would not expose him to personal liability for amounts which might become owing by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care under the Agreement.

21 His Honour noted that Mr Compton’s evidence consisted of his own affidavit and some documents, and that Mr Compton’s affidavit was read without him being required for cross-examination due to his apparent indisposition for medical reasons when the hearing commenced. His Honour also noted that, the Court having refused an application made on Mr Compton’s behalf to adjourn the hearing, Ramsay Health Care had elected to proceed on the basis that his affidavit be read without Mr Compton having to be available for cross-examination.

22 His Honour held that Ramsay Health Care was entitled to succeed because:

(a) the evidence established clearly that both the first and second signing pages were part of the Guarantee or related to, and related only to, the Guarantee; by his signatures, Mr Compton communicated to Ramsay Health Care consent to be bound by the terms contained in it; and

(b) Mr Compton had fallen well short of establishing that his mind did not go with his signatures; indeed, his own evidence showed that it did.

23 Accordingly, there was judgment for Ramsay Health Care against Mr Compton in the amount of $9,810,312.

24 In the Stevis Supreme Court Affidavit which, as noted above, was not read in the Supreme Court proceeding, Ms Stevis annexed a statement of the amount owed by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care that had been submitted to Ramsay Health Care. This stated that MediChoice owed Ramsay Health Care the substantially smaller sum of $2,264,824.

25 However, in an affidavit filed by Mr Compton in support of the interim application in this Court, Ms Stevis said that she had conducted an analysis and reconciliation of moneys owed between Ramsay Health Care and MediChoice and, when all moneys were accounted for as between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care, MediChoice did not owe any money to Ramsay Health Care; rather, Ramsay Health Care owed at least $2,449,000 to MediChoice. The affidavit described the schedules underpinning the analysis. It did not refer to the Stevis Supreme Court Affidavit; nor did it explain why the result of the analysis was markedly different from the statement annexed to the Stevis Supreme Court Affidavit.

26 In Mr Albarran’s first affidavit (sworn 7 July 2015), filed by Mr Compton in support of the interim application, Mr Albarran stated that, as part of carrying out the liquidation of MediChoice, he and the other two joint liquidators (Mr Kijurina and Mr Ingram) had endeavoured to reconcile the accounts of MediChoice to determine whether money was owed by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care or, in the alternative, whether money was owed by Ramsay Health Care to MediChoice. Mr Albarran explained that, in order to carry out the reconciliation, they needed to obtain financial records from various entities that were involved in the transactions between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care said to give rise to the debts claimed by Ramsay Health Care in the Supreme Court proceeding and a subsequent proof of debt lodged by Ramsay Health Care in the liquidation of MediChoice. After referring to certain financial documents that had been provided by Ms Stevis, Mr Albarran stated that the liquidators had received documents from a Chinese supplier and that documents had been requested from Clifford Hallam (CH2), a third party entity that acquired pharmaceutical products from MediChoice for supply to or for Ramsay Health Care. Mr Albarran stated that if Mr Compton could obtain the documents requested from CH2 through the use of the processes of the Court, then he and the other liquidators were prepared to undertake an examination of those documents to assess what they disclosed in relation to amounts owing as between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care. Mr Albarran referred to the amount claimed by Ramsay Health Care from Mr Compton in the Supreme Court proceeding and stated:

However, using the documents that are currently before Mr Kijurina, Mr Ingram and I, including but not limited to the documents provided by the Chinese supplier and the CH2 documents provided by Ms Stevis, it appears on our preliminary calculations that it is more likely than not, if those documents are accurate, that [Ramsay Health Care] owes more money to [MediChoice] than [MediChoice] would owe to [Ramsay Health Care]. On the documents that the Liquidators currently hold, based on our calculations from those documents, it appears more likely that [Ramsay Health Care] is a debtor of [MediChoice] rather than a creditor. Once again, this is based on the assumption that the documents we have are accurate and our calculations are accurate. This position may change upon the completion of our investigations and/or the receipt of further documents, including but not limited to, the documents held by CH2, to verify our findings.

(Emphasis added.)

27 Annexed to Mr Albarran’s first affidavit was a letter dated 12 May 2015 which the liquidators had sent to Mr Compton giving a brief indication of their investigations to that point.

28 In Mr Albarran’s second affidavit, he stated that the liquidators had received a box of documents from Ramsay Health Care and had been asked by Ramsay Health Care to substantiate the figure claimed in its proof of debt; that the documents contained calculations and workings which the liquidators had not previously reviewed in respect of Ramsay Health Care’s proof of debt; that the accounting work required to finalise the liquidators’ findings was complex; that he estimated that it would take approximately one or two months for the liquidators to finalise their position with respect to the quantum owing between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care; and that, at the time of swearing his affidavit, he stood by the statements in his first affidavit.

29 Mr Ingram stated in his affidavit that he had read and agreed with the contents of each of Mr Albarran’s affidavits. He also said that, at the time of swearing his affidavit, the liquidators had still not received a copy of the report or workings of KPMG commissioned by Ramsay Health Care into the MediChoice business, nor any documents directly from CH2. He annexed a letter sent to the solicitor acting for Ramsay Health Care setting out questions that the liquidators had in relation to the documents provided by Ramsay Health Care in support of Ramsay Health Care’s proof of debt claim and estimated that within about two weeks of receiving a substantive response from Ramsay Health Care the liquidators might be able to make an adjudication in relation to Ramsay Health Care’s proof of debt.

30 As noted above, Ramsay Health Care filed two affidavits in connection with the interim application. The affidavit of Ms Murray has been described above. The other affidavit was of Mr Hirner, the Group Financial Controller. He stated that Ramsay Health Care had received from MediChoice invoices totalling $3,431,604 which had not been paid. He stated that Ramsay Health Care accepted some of these invoices and disputed others. He stated that the reason Ramsay Health Care had not paid those invoices was because MediChoice was indebted to Ramsay Health Care in the amount of $9,810,312. He stated that Ramsay Health Care accepted that, in the liquidation of MediChoice and any bankruptcy of Mr Compton, when Ramsay Health Care submitted a proof of debt, the amount of the unpaid and undisputed invoices outstanding to MediChoice would need to be set off by the relevant liquidator and trustee.

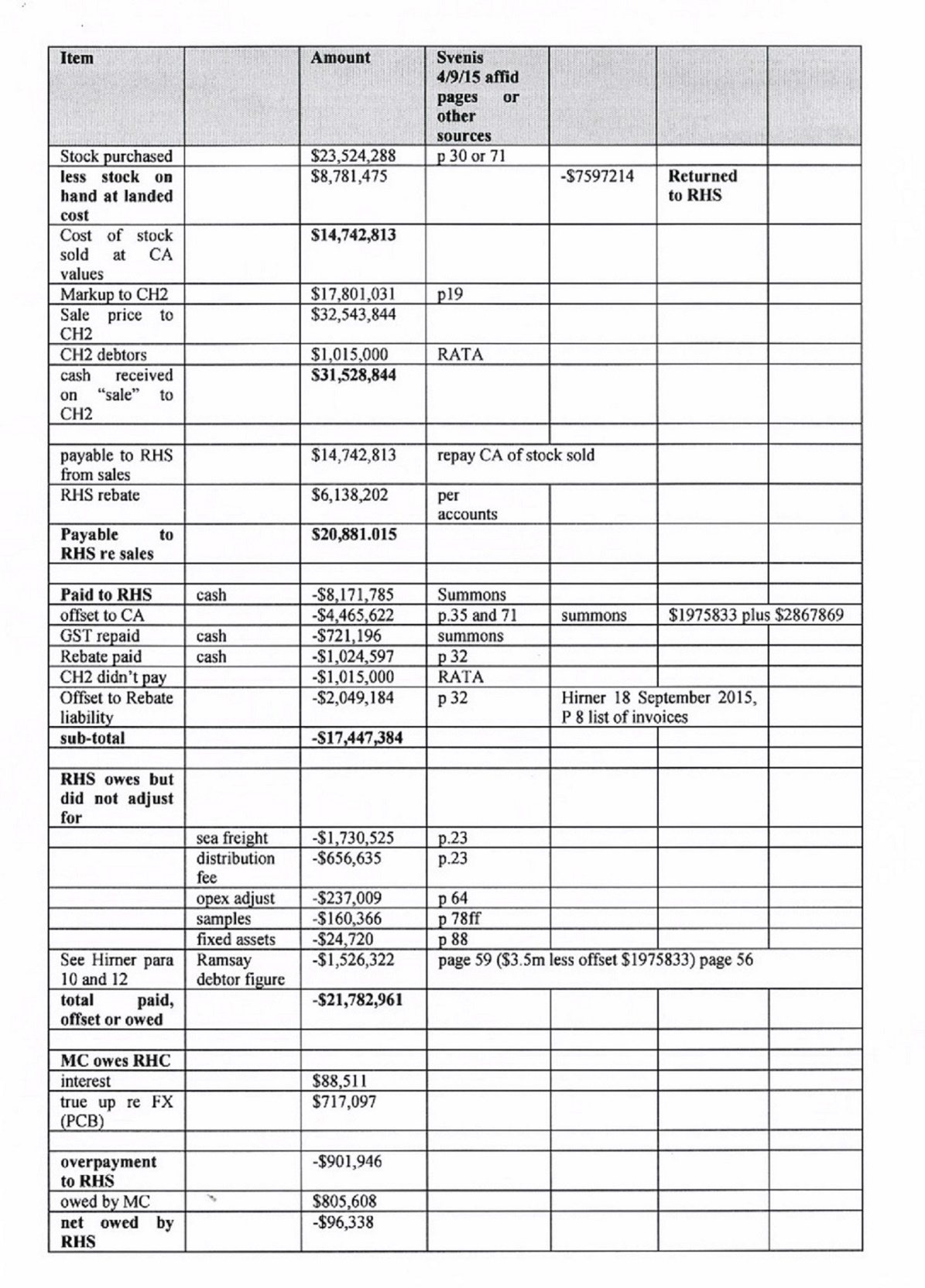

31 At the hearing before the primary judge, senior counsel for Mr Compton handed up a table, referred to as a “reconciliation”, which summarised the effect of the evidence of Ms Stevis and Mr Hirner filed in connection with the interim application. The table is reproduced in [10] of the reasons of the primary judge and below:

32 The effect of the evidence summarised in the first 10 rows is that an amount of $20,881,015 was payable by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care. The effect of the next six rows is that an amount of $17,447,384 was to be deducted, with the result that approximately $3.4 million was payable by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care at this stage of the calculation. The effect of the next seven rows was that the amount to be deducted (from the amount of $20,881,015) rose to $21,782,961, producing an excess of approximately $900,000. Thus, if the figures representing deductions were correct, Ramsay Health Care would owe MediChoice approximately $900,000, rather than MediChoice owing money to Ramsay Health Care.

33 As recorded in the reasons of the primary judge (at [10]), senior counsel for Ramsay Health Care did not put in issue the proposition that the factual details in the affidavits resulted in the calculations undertaken in the table; what was not accepted on behalf of Ramsay Health Care was the factual accuracy or reliability of those details. Further, the primary judge recorded (at [11]) that senior counsel for Ramsay Health Care accepted that:

(i) the table was basically correct down to the line disclosing the amount payable to Ramsay Health Care in the sum of $20,881,015;

(ii) the indebtedness of Mr Compton was for an amount less than the judgment amount; and

(iii) it was an “open question” as to whether the calculations set forth with respect to “offsets”, “rebates” and the like were factually correct.

The decision of the primary judge

34 The primary judge described the proceeding before the Supreme Court and noted that quantum had not been in dispute (at [7]-[9]).

35 After setting out the reconciliation table and the position of Ramsay Health Care in relation to the table (discussed above), his Honour said that the primary line of opposition pursued on behalf of Ramsay Health Care was that, in the circumstances, the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment was not enlivened or, alternatively, as a matter of discretion, the Court ought not do so (at [11]).

36 The primary judge noted that the evidence filed in this Court included the affidavit of Mr Hirner and an affidavit of Ms Stevis stating that Ramsay Health Care owed MediChoice at least $2,449,000 (at [12]). He also noted that a number of investigations and inquiries as to the competing claims had been conducted and were still being conducted.

37 His Honour discussed, at [13]-[16], the principles to be applied, referring to the decisions of Corney v Brien (1951) 84 CLR 343 and Wren v Mahony (1972) 126 CLR 212, and setting out passages from Ahern v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (Qld) (1987) 76 ALR 137 at 147-148 per Davies, Lockhart and Neaves; Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Jeans (2005) 3 ABC(NS) 712; [2005] FCA 978 at [17]-[22] per Hely J; and Katter v Melham (No 2) (2014) 319 ALR 646 at [69]-[73], [77]-[79] per Wigney J.

38 In paragraphs [17]-[26], his Honour set out his reasons for concluding that the Court should not ‘go behind’ the judgment of the Supreme Court. There were two alternative reasons, namely:

(a) the circumstances in which the discretion should be exercised had not been enlivened; and

(b) even if that conclusion were erroneous, as a matter of discretion, the Court ought not do so.

39 In paragraph [18], his Honour said that it would be a mistake to construe the phrase, “fraud or collusion or miscarriage of justice” (referred to by Fullagar J in Corney v Brien (1951) 84 CLR 343 at 356-357) as artificially confining the circumstances in which the discretion to ‘go behind’ a judgment may be exercised. He said that the manner in which Fullagar J expressed himself should not be construed as an exhaustive statement of the circumstances in which the discretion may be enlivened, as recognised by Wigney J in Katter at [70].

40 The primary judge stated at [19] that the concern of the Court must constantly remain whether it is just to permit a judgment debtor to ‘go behind’ a judgment and show that there is “in truth and reality” no debt due to the petitioning creditor, citing Wren v Mahony at 224. His Honour also stated that bankruptcy, it must constantly be recalled, is not mere inter partes litigation, citing Ahern at 148.

41 In paragraph [20], the primary judge stated:

In the circumstances of the present case, it is respectfully concluded that no circumstances have been exposed which would make it just to “go behind” the judgment of the Supreme Court. Even if it be accepted that the “reconciliation” relied upon by Mr Compton raises an “open question” as to the extent of any liabilities that may be owed either by Mr Compton to Ramsay Health Care or by Ramsay Health Care to Mr Compton, the discretion to “go behind” the judgment is not enlivened in circumstances where:

• Mr Compton was represented by Counsel in the proceeding in the Supreme Court;

• there was available evidence that had been filed in that Court addressing the quantum of any liability that may be owed; and

• a forensic decision was made to confine the issue to be resolved by that Court to the enforceability of the guarantee.

Moreover, and even though Mr Compton had not attempted in his affidavit filed in that proceeding to put in issue the quantum of any liability:

• no prejudice was occasioned by his inability to attend the Supreme Court proceeding and be cross-examined on his affidavit. The transcript of that proceeding records the fact that Senior Counsel for Ramsay Health Care consented to his affidavit being relied upon.

The observations of Barwick CJ in Wren v Mahoney, it is respectfully considered, are not to be read as any qualification to the statement of general principle as formulated by Fullagar J in Corney v Brien.

42 In such circumstances, his Honour concluded, there would be no “miscarriage of justice” and no “injustice” in holding Mr Compton to the manner in which he conducted the proceeding in the Supreme Court (at [21]).

43 The primary judge also held that, even if that conclusion were erroneous, the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment would not have been exercised in favour of Mr Compton and stated (at [22]):

The decision to refuse to exercise that discretion in his favour is founded upon:

• the same considerations that have dictated the former conclusion;

together with such further considerations as that:

• the factual materials upon which the “reconciliation” has now been carried out were available to Mr Compton at the time of the Supreme Court hearing. The “reconciliation” now available to this Court could have been undertaken – either in whole or in part – and presented to the Supreme Court for consideration. Although that factual material may have been available as at the date of the Supreme Court hearing, it must nevertheless be recognised that what was not available at that time were the subsequent inquiries and expressions of opinion by the liquidators of MediChoice – including an opinion expressed in May 2015 that the liquidator was “currently in the process of completing my investigations into the Company’s affairs” and that “based on investigations completed to date, I consider the indebtedness of the company to Ramsay is likely to be a figure significantly less than the amount of the judgement, and there is a prospect that Ramsay may in fact be indebted to the Company”; and

• no explanation has been advanced on behalf of Mr Compton as to why the quantum of any indebtedness was not put in issue before the Supreme Court or why the “reconciliation” now available was not previously undertaken.

Other considerations taken into account when exercising the discretion include:

• the fact that Ramsay Health Care now accepts that the indebtedness is a sum less than $9,810,312.33 but maintains that there remains outstanding an indebtedness of a significant amount;

• reservation as to whether the “reconciliation” provides “substantial reasons for questioning whether behind the judgment there is in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor”. There remains, for example, a disturbing discrepancy between the evidence of Ms Stevis given in the Supreme Court proceeding and the evidence now given in this Court. The analysis now undertaken by Ms Stevis calculates an amount owing by Ramsay Health Care in an amount of at least $2.4 million. Previously, her evidence in the Supreme Court was that the amount owing to Ramsay Health Care Services was $2,264,824.17. In any contested hearing as to the quantum of any indebtedness, questions would have arisen with respect to the admissibility of her evidence; and

• the fact that there also remain a number of outstanding inquiries and investigations as to the competing claims being made. The relevance of such inquiries and investigations is simply to underline the fact that there is no certainty as to the factual merits of those competing claims and, more relevantly, the absence of any relatively reliable factual foundation to question whether in “truth and reality” there remains a debt owing to Ramsay Health Care, albeit not a debt in the sum of $9,810,312.33 as claimed in the Creditor’s Petition.

Albeit of lesser importance, a further matter of relevance is:

• the fact that Mr Compton has provided no evidence as to his current solvency.

44 In paragraph [23], the primary judge recognised that the fact that there has been “a hearing on the merits where both parties appeared” does not preclude the exercise of the discretion to ‘go behind’ a judgment, referring to Ahern at 147. His Honour referred to circumstances where this might occur and then stated that “normally a party is bound by the manner in which he conducts a hearing”.

45 His Honour said that, as a practical matter, it perhaps mattered not whether the ultimate conclusion was best reached by the route of concluding that the discretion was not enlivened or that the discretion — even if enlivened — should not be exercised; the considerations relevant to each route of analysis substantially overlapped and the result of each analysis was the same (at [24]).

46 In paragraph [26], his Honour addressed a submission put on behalf of Mr Compton:

To the extent that it is submitted on behalf of Mr Compton in his written submissions that “it would be a serious injustice to bankrupt Mr Compton in respect of guaranteeing a debt that is not owed and in respect of a judgment that should never have been entered against him”, it is concluded that there would be no “injustice” to Mr Compton. He has participated in a three day hearing before the Supreme Court of New South Wales in circumstances where there was available evidence as to the quantum of any indebtedness in the event that Ramsay Health Care could proceed upon the guarantee executed by him in November 2012. He made a forensic decision not to put the quantum of any indebtedness in issue in circumstances where he was represented by both Counsel and solicitors. And the highest that such evidence as is now available to this Court reaches as to the quantum of any indebtedness is that there remains an “open question” whether there is any indebtedness. Although there are undoubtedly cases where the making of a sequestration order may well be open to question (e.g., Hacker v Weston [2015] FCA 363 at [73]), it certainly cannot be said in the present case that judgment “should never have been entered against” Mr Compton upon the evidence placed before the Supreme Court.

The application for leave to appeal and draft notice of appeal

47 The application for leave to appeal is a lengthy document, comprising six grounds challenging the decision of the primary judge, and two grounds relating to leave to appeal. The six grounds challenging the primary judge’s decision were, in summary:

(a) Ground 1. The primary judge erred in concluding at [21] of the reasons that, by holding Mr Compton to his failure to challenge the existence or amount of the debt in the Supreme Court proceeding, there would be no “miscarriage of justice” and no “injustice” in not going behind the Supreme Court judgment and, accordingly, the Court’s jurisdiction was not enlivened. The primary judge erred because such a challenge to quantum in the Supreme Court was not in fact possible on the evidence of Ms Stevis, as that evidence stood at the time of the Supreme Court trial.

(b) Grounds 2, 3 and 4. The primary judge erred at [21] and [22], further or in the alternative at [17]-[21] of the reasons, on the basis that the primary judge did not take into account the following material facts in the process of reaching those conclusions:

(i) the opinion of the liquidators of MediChoice that it was more likely than not that MediChoice did not owe any money to Ramsay Health Care, was not available to Mr Compton until after judgment was entered in the Supreme Court;

(ii) the evidence of Ms Stevis available at the trial in the Supreme Court indicated that at least $2.4 million was owing by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care, but her subsequent, detailed analysis finding that MediChoice did not owe any money to Ramsay Health Care, was not available to Mr Compton until after judgment in the Supreme Court proceeding, nor had Ms Stevis expressed that opinion in the Supreme Court proceeding;

(iii) because Ms Stevis had concluded before the Supreme Court trial that at least $2.4 million was owing by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care, the amount owing was of such a magnitude that there was, or may have been, no practical benefit to Mr Compton to challenge the quantum in the Supreme Court proceeding (because, whether the judgment amount was $9.8 million or $2.4 million, he would not be able to pay it);

(iv) at the time of refraining from challenging quantum in the Supreme Court proceeding, Mr Compton did not have the benefit of the concession made by Mr Hirner (in his affidavit filed in relation to the interim application) that the amount owing by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care was not $9.8 million and was to be reduced by up to $3.4 million; and

(v) no evidence was filed by Ramsay Health Care challenging the methodology adopted by Ms Stevis or the facts on which her affidavit was based.

(c) Ground 5. The primary judge erred at [22]-[24] of the reasons, in considering whether to exercise the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment, by finding (at [22]) that there was an absence of any relatively reliable factual foundation to question whether in truth and reality there remained a debt owing to Ramsay Health Care in that:

(i) the primary judge found (at [26]) that, taking the evidence of the liquidators and Ms Stevis at its highest, whether there was any indebtedness remained an “open question”;

(ii) in finding (at [22]) that there was no certainty as to the opinion expressed by the liquidators that it was more likely than not that MediChoice did not owe any money to Ramsay Health Care, the primary judge did not expressly take into account that Ramsay Health Care did not challenge by cross-examination the liquidators’ affidavits and the uncertainty arose in whole or substantial part from the failure of Ramsay Health Care to respond to requests for information by the liquidators;

(iii) although the primary judge expressed concerns (at [22]) as to the inconsistency between the analysis of Ms Stevis before and after the Supreme Court trial, the primary judge did not expressly take into account that the analysis of Ms Stevis in her affidavits in connection with the interim application was significantly more extensive than that expressed in her affidavit filed in the Supreme Court proceeding; or that Ramsay Health Care did not challenge by cross-examination Ms Stevis’s evidence.

(d) Ground 6. The primary judge erred at [22]-[26] of the reasons in considering whether to exercise the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment, by not taking into account:

(i) the matters set out above;

(ii) if the opinions expressed by the liquidators in their evidence were correct, that there was no basis for the debt alleged by Ramsay Health Care and the consequent injustice of bankrupting Mr Compton;

(iii) if the evidence of Ms Stevis filed in connection with the interim application were correct, that there was no basis for the debt alleged by Ramsay Health Care, and the consequent injustice of bankrupting Mr Compton.

48 These six grounds were replicated in Mr Compton’s draft notice of appeal.

Leave to appeal

49 Although the decision of the primary judge was formally interlocutory (as it was made on return of Mr Compton’s interim application), it followed a hearing which was, in effect, the hearing of a separate question, namely whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment of the Supreme Court. In all likelihood the adverse determination of this question would determine the outcome of the creditor’s petition. In these circumstances, the decision was one determining a substantive right (cf Decor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1991) 33 FCR 397 at 398-399 per Sheppard, Burchett and Heerey JJ) and it is appropriate for leave to appeal to be granted.

Going behind a judgment

50 The appeal raises issues concerning the power of a court of bankruptcy to ‘go behind’ a judgment upon which the petitioning creditor relies. In particular, the issues concern a situation where the judgment debtor contends that, in ‘truth and reality’, no debt is owing, notwithstanding that he appeared at, and participated in, a contested trial where the issue now sought to be raised could have been, but was not, raised.

51 The starting point for the consideration of these issues is the relevant provisions of the Bankruptcy Act and first s 43, which deals with the jurisdiction to make a sequestration order:

43 Jurisdiction to make sequestration orders

(1) Subject to this Act, where:

(a) a debtor has committed an act of bankruptcy; and

(b) at the time when the act of bankruptcy was committed, the debtor:

(i) was personally present or ordinarily resident in Australia;

(ii) had a dwelling-house or place of business in Australia;

(iii) was carrying on business in Australia, either personally or by means of an agent or manager; or

(iv) was a member of a firm or partnership carrying on business in Australia by means of a partner or partners or of an agent or manager;

the Court may, on a petition presented by a creditor, make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

(2) Upon the making of a sequestration order against the estate of a debtor, the debtor becomes a bankrupt, and continues to be a bankrupt until:

(a) he or she is discharged by force of subsection 149(1); or

(b) his or her bankruptcy is annulled by force of subsection 74(5) or 153A(1) or under section 153B.

52 Section 52 of the Act relevantly provides:

52 Proceedings and order on creditor’s petition

(1) At the hearing of a creditor’s petition, the Court shall require proof of:

(a) the matters stated in the petition (for which purpose the Court may accept the affidavit verifying the petition as sufficient);

(b) service of the petition; and

(c) the fact that the debt or debts on which the petitioning creditor relies is or are still owing;

and, if it is satisfied with the proof of those matters, may make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

…

(2) If the Court is not satisfied with the proof of any of those matters, or is satisfied by the debtor:

(a) that he or she is able to pay his or her debts; or

(b) that for other sufficient cause a sequestration order ought not to be made;

it may dismiss the petition.

53 As we have already observed, it is well established that, by reason of the matters referred to in s 52(1) and (2), the Court has power to ‘go behind’ a judgment upon which a petitioning creditor relies to see whether there is, in ‘truth and reality’, a debt owing. We interpolate that some judgments refer to s 52(1) (or the comparable provision of the former Act, namely s 56(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth)) as the source of the power (for example, Corney v Brien at 347), while others refer to s 52(2) (for example, Wren v Mahony at 232 per Menzies J); see Colvin C, “Assailing a Judgment Relied Upon in a Bankruptcy Notice” (1986) 2 Australian Bar Review 164 at 169.

54 In In re Fraser; Ex parte Central Bank of London [1892] 2 QB 663, Lord Esher MR said (at 636):

The Court of Bankruptcy can go behind the judgment, and can inquire whether, notwithstanding the judgment, there was a good debt. In so doing, the Court of Bankruptcy does not set aside the judgment. If I may use the expression, the Court goes round the judgment, and inquires into the subject matter.

55 Referring to Ex parte Lennox; In re Lennox (1885) 16 QBD 315, his Lordship explained the rationale for the power in the following, oft-cited passage (at 636):

The decision is based upon the highest ground — viz., that in making a receiving order, the Court is not dealing simply between the petitioning creditor and the debtor, but it is interfering with the rights of his other creditors, who, if the order is made, will not be able to sue the debtor for their debts, and that the Court ought not to exercise this extraordinary power unless it is satisfied that there is a good debt due to the petitioning creditor. The existence of the judgment is no doubt prima facie evidence of a debt; but still the Court of Bankruptcy is entitled to inquire whether there really is a debt due to the petitioning creditor.

56 Also in In re Fraser; Ex parte Central Bank of London, Kay LJ said (at 637-638):

In Ex parte Bryant [1 V & B at p 214], Lord Eldon said: “Proof upon a judgment will not stand merely upon that, if there is not a debt due in ‘truth and reality,’ for which the consideration must be looked to.”

57 The power to ‘go behind’ a judgment was considered in detail by the High Court in Corney v Brien and Wren v Mahony. In Corney v Brien, a joint judgment was delivered by Dixon, Williams, Webb and Kitto JJ; Fullagar J delivered a concurring judgment. The joint judgment contained the following passage (at 347-348):

Section 56(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act 1924-1950 provides that the court at the hearing shall require proof of the debt of the petitioning creditor. Under this provision the Court of Bankruptcy has undoubted jurisdiction to go behind a judgment obtained by default or compromise or where fraud or collusion is alleged and inquire whether the judgment is founded on a real debt. In Ex parte Kibble [(1875) LR 10 Ch 373, at p 376] Sir W.M. James LJ said: “It is the settled rule of the Court of Bankruptcy, on which we have always acted, that the Court of Bankruptcy can inquire into the consideration for a judgment debt”. Sir G Mellish LJ said: “It is quite clear that in the Court of Bankruptcy the consideration for a judgment may be investigated, particularly when the judgment has gone by default” [(1875) 10 Ch 373, at p 378]. This case was discussed and followed in Ex parte Lennox [(1885) 16 QBD 315], where the reasons why the Court of Bankruptcy will go behind a judgment debt are fully discussed. Lindley LJ said that “the Court of Bankruptcy will not allow itself to be put in motion at the instance of a person who is not a real creditor” [(1885) 16 QBD 315, at p 329]. In In re Fraser [(1892) 2 QB 633, at pp 637, 638] Kay LJ said: “It is old law in bankruptcy that, neither upon an attempt to prove a debt, nor upon a petition for an adjudication of bankruptcy or a receiving order against a debtor, is a judgment against him for the debt conclusive. In Ex parte Bryant [(1813) 1 V & B 211, at p 214 [35 ER 83, at p 84]] Lord Eldon said: ‘Proof upon a Judgment will not stand merely upon that, if there is not a Debt due in Truth and Reality, for which the Consideration must be looked to’.” In In re Gooch [(1921) 2 KB 593, at p 603] Scrutton LJ said: “The county court registrar held quite correctly that he was at liberty to go behind the judgment, and see whether there was a good debt to support it”. In In re a Debtor [(1929) 1 Ch 125, at p 127] Astbury J said “True it is that the Bankruptcy Court may, upon a prima-facie case being shown, go behind a judgment for the purpose of satisfying itself that the debt enforceable thereunder was a real debt.” In Petrie v Redmond, a case in this Court [(1942) 13 ABC 44, at pp 48, 49; (1943) QSR 71, at pp 75, 76], Latham CJ said: “The court (that is, the Court of Bankruptcy) is entitled to go behind the judgment and inquire into the validity of the debt where there has been fraud, collusion or miscarriage of justice. … Also the court looks with suspicion on consent judgments and default judgments.”

58 In his judgment, Fullagar J explained that, generally speaking, a judgment at law for a sum of money creates an obligation of its own force; the pre-existing obligation merges in the new obligation so created and, for most purposes as between the parties, it is conclusive evidence of the existence of the obligation which it creates (at 353). However, his Honour said it had been “well settled for very many years” that a court having jurisdiction in bankruptcy “will in many cases… ‘go behind’ the judgment and inquire into the existence of the debt upon which it is said to be founded” (at 353-354). He described the general power of the court of bankruptcy to investigate the foundation of a judgment as “unquestioned and unquestionable”. In the course of a detailed consideration of the cases, his Honour said:

[I]n later cases the rule is stated in the widest terms and without any reference to “consideration”. Thus in Ex parte Lennox; In re Lennox [(1885) 16 QBD 315, at p 326], Cotton LJ treats Ex parte Kibble; In re Onslow [(1875) LR 10 Ch 373, at p 373] as having decided “that, for the purpose of deciding whether there ought to be an adjudication of bankruptcy, the court will, on the application of the debtor, enter into the question whether a judgment is sufficient evidence of a debt — whether, when the facts behind the judgment are known, there is sufficient evidence to satisfy the court that a debt really existed”.

59 After considering other cases, his Honour said (at 356-357):

I have already quoted the statement of the principle by Cotton LJ in Ex parte Lennox; Re Lennox [(1885) 16 QBD 315, at p 326]. When the learned Lord Justice used the word “will”, it is obvious that he did not mean “will always” or “will as a matter of course”, and, with respect, I think that the whole trend of the cases before and since shows that he did not state the power, or the purpose for which the power might be used, too widely. No precise rules exist as to what circumstances call for an exercise of the power, but certain things are, I think, clear enough. If the judgment in question followed a full investigation at a trial on which both parties appeared, the court will not reopen the matter unless a prima-facie case of fraud or collusion or miscarriage of justice is made out. In In re Flatau; Ex parte Scotch Whisky Distillers Ltd [(1888) 22 QBD 83, at p 86] Fry LJ said: “This power has never, so far as I am aware, been extended to cases in which a judgment has been obtained after issues have been tried out before a court”.

(Emphasis added.)

60 When the emphasised sentence in the above passage is read in context, we do not consider it to represent an exhaustive statement of the circumstances in which a court of bankruptcy may or should ‘go behind’ a judgment which follows a “full investigation at trial on which both parties appeared”. The cases discussed by Fullagar J in his judgment do not suggest as much. Nor does the joint judgment. The proposition that was advanced in In re Flatau; Ex parte Scotch Whisky Distillers Ltd (1888) 22 QBD 83 was that in every case a court of bankruptcy is bound to go behind the judgment and inquire into the validity of the debt. That was the proposition which was rejected at 85 per Lord Esher MR with whose judgment Fry LJ agreed. As Besanko J observed in Goyan v Motyka [2009] FCA 776 at [53], the principles must be applied flexibly in view of “the myriad of circumstances” that might arise.

61 In Wren v Mahony, the leading judgment was delivered by Barwick CJ, with whom Windeyer and Owen JJ agreed. Menzies and Walsh JJ dissented. The legislation before the Court was the Bankruptcy Act 1966. Sub-sections (1) and (2) of s 52 were in substantially the same terms as they are at present. After setting out key passages from Ex parte Lennox; In re Lennox, In re Fraser; Ex parte Central Bank of London, In re Flatau; Ex parte Scotch Whisky Distillers Ltd and In re Hawkins; Ex parte Troup [1895] 1 QB 404, Barwick CJ said (at 223):

I have made these several quotations in order to emphasize the dominant place the mandatory words of s 52(1) occupy in relation to the making of a sequestration order and that the resolution of the question whether or not the proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt is satisfactory does not concern only the immediate parties to the petition.

62 After this passage, Barwick CJ said that the learned judge in bankruptcy appeared to have had some reservation as to the existence of the court’s power to examine the consideration for the judgment and seemed to think that whether or not he should consider whether there was a debt due to the petitioning creditor “rested merely in discretion” (at 223-224). Barwick CJ noted that in In re Flatau; Ex parte Scotch Whisky Distillers Ltd, Lord Esher, in emphasising that the bankruptcy court did not go behind a judgment as a matter of course but only if appropriate circumstances were shown to exist, used the word “discretion” (at 224). Barwick CJ said that Lord Esher, in using that expression, was not intending to weaken the emphasis he had always placed on “the need for the Court of Bankruptcy to be satisfied of the existence of the petitioning creditor’s debt”; rather, “he was pointing out that the Bankruptcy Court could in general accept a judgment debt as sufficient proof of that debt particularly where it resulted from a fully heard contest between parties but that it always had the power to go behind the judgment and if the case was a proper one should do so” (at 224). Barwick CJ then said (at 224-225):

The judgment is never conclusive in bankruptcy. It does not always represent itself as the relevant debt of the petitioning creditor, even though under the general law, the prior existing debt has merged in a judgment. But the Bankruptcy Court may accept the judgment as satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor's debt. In that sense that court has a discretion. It may or may not so accept the judgment. But it has been made quite clear by the decisions of the past that where reason is shown for questioning whether behind the judgment or as it is said, as the consideration for it, there was in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor, the Court of Bankruptcy can no longer accept the judgment as such satisfactory proof. It must then exercise its power, or if you will, its discretion to look at what is behind the judgment: to what is its consideration. It is not the law, in my opinion, that whether in any case the Court of Bankruptcy will consider whether there is satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt is a mere matter of its own discretion. Nothing in Corney v Brien [(1951) 84 CLR 343] lends support for such a view. Rather the emphasis is upon the paramount need to have satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt. The Court's discretion in my opinion is a discretion to accept the judgment as satisfactory proof of that debt. That discretion is not well exercised where substantial reasons are given for questioning whether behind that judgment there was in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioner.

(Emphasis added.)

63 The judgment of Barwick CJ in Wren v Mahony represents the judgment of a majority of the High Court. It has not been questioned since. It does not appear to us to be saying anything different from the joint judgment in Corney v Brien or, for that matter, the judgment of Fullagar J in that case. But if, and to the extent that, there is any difference, it is Wren v Mahony that represents the law on the subject which this Court is to apply. Importantly, in the sentence emphasised in the above passage, Barwick CJ said that “where reason is shown for questioning whether behind the judgment … there was in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor” then the court of bankruptcy can no longer accept the judgment as satisfactory proof. The Chief Justice did not see this as a “mere matter” of the court’s discretion. Rather, “the emphasis is upon the paramount need to have satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt”.

64 It may be noted that, in the last sentence of the passage set out above, Barwick CJ said that, in a case where “substantial reasons” are given for questioning whether behind the judgment there was in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioner, the discretion (to accept the judgment as satisfactory proof of the debt) would not be well exercised. We do not consider there to be any inconsistency between that sentence and the sentence which is emphasised in the above quotation. The last sentence of the quoted passage provides an example of a case where the discretion (to accept the judgment as satisfactory proof of the debt) would not be well exercised.

65 The principles relating to ‘going behind’ a judgment have been considered in several decisions of the Full Court of this Court, including Ahern v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (Qld) (1987) 76 ALR 137; Olivieri v Stafford (1989) 24 FCR 413; Evans v The Heather Thiedeke Group Pty Ltd (unreported; 28 September 1990); Wolff v Donovan (1991) 29 FCR 480; Udovenko v Mitchell (1997) 79 FCR 418; and Joossé v Commissioner of Taxation (2004) 137 FCR 576. In Ahern, Davies, Lockhart and Neaves JJ said (at 147-148):

It is well established that a court exercising bankruptcy jurisdiction has undoubted discretion to go behind a judgment, particularly one obtained by default or compromise or where fraud or collusion is involved and inquire whether the judgment is founded on a real debt: Corney v Brien (1951) 84 CLR 343. Where the judgment is by default the court will go behind the judgment if there is a bona fide allegation that no real debt underlies the judgment: Corney v Brien. Even where the judgment was obtained following a hearing on the merits where both parties appeared, if there are substantial reasons for questioning whether behind the

judgment there is in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor, the court will go behind the judgment and inquire into the consideration for it: Wren v Mahony (1972) 126 CLR 212 per Barwick CJ, with whose reasons Windeyer and Owen JJ agreed; Menzies and Walsh JJ dissenting.

(Emphasis added.)

66 After quoting the passage from Wren v Mahony set out in [62] above, Davies, Lockhart and Neaves JJ continued (at 148):

It is also well established that in general a court exercising jurisdiction in bankruptcy should not proceed to sequestrate the estate of a debtor where an appeal is pending against the judgment relied on as the foundation of the bankruptcy proceedings provided that the appeal is based on genuine and arguable grounds: Re Rhodes; Ex parte Heyworth (1884) 14 QBD 49; Bayne v Baillieu (1907) 5 CLR 64 and Re Verma; Ex parte DCT (1985) 4 FCR 181.

These cases rest on the broad principle that before a person can be made bankrupt the court must be satisfied that the debt on which the petitioning creditor relies is due by the debtor and that if any genuine dispute exists as to the liability of the debtor to the petitioning creditor it ought to be investigated before he is made bankrupt. Bankruptcy is not mere inter partes litigation. It involves change of status and has quasi-penal consequences.

67 The passages from the cases set out above emphasise that s 52(1)(c) and (2) of the Bankruptcy Act require there to be satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt, and that where reason is shown for questioning whether behind the judgment there is in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor, the court of bankruptcy can no longer accept the judgment as such satisfactory proof. The cases rest on the particular nature of bankruptcy litigation or, more accurately, the effect of a bankruptcy order. In addition to the serious consequences for the debtor mentioned in Ahern above, it has consequences for non-parties in that it also interferes with the rights of other creditors.

Disposition of the appeal

68 The primary judge gave two alternative reasons for his conclusion that the Court should not ‘go behind’ the judgment: first, that the circumstances in which the discretion should be exercised had not been enlivened; and, secondly, as a matter of discretion, the Court ought not do so: see [38] above. The authorities discussed above do not support such an approach. While they accept that in some cases it may be appropriate to investigate, as a preliminary matter, whether or not the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment (see Corney v Brien at 358; Wolff v Donovan at 486-487), they do not suggest that, if that preliminary investigation takes place, there are two stages of analysis. In our respectful view, if there is a preliminary investigation into whether or not to ‘go behind’ a judgment (as there was in this case), there is but one issue to be addressed, namely whether or not the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment.

69 As we indicated at [41] above, the primary judge considered that the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment was not enlivened because Mr Compton was represented by counsel in the Supreme Court proceeding; there was available evidence that had been filed in that Court addressing the quantum of any liability that may be owed; and a forensic decision was made to confine the issue to be resolved by that Court to the enforceability of the guarantee. The matters upon which his Honour relied focused on the way in which Mr Compton conducted his case in the Supreme Court rather than on the central issue, which was whether reason was shown for questioning whether behind the judgment there was in truth and reality a debt due to the petitioning creditor. Had the focus been on that issue, the answer would have been quite different, for the evidence disclosed substantial reasons for questioning whether Mr Compton was indebted to Ramsay Health Care. Quite apart from the evidence of Ms Stevis, there was the evidence of Mr Albarran, confirmed by Mr Ingram, both liquidators of MediChoice, that on his calculations based on the documents in their possession (see [26] and [29] above), it was more likely that Ramsay Health Care was indebted to MediChoice than that MediChoice was indebted to Ramsay Health Care. If that were correct, then there would be no debt owed to Ramsay Health Care by Mr Compton pursuant to the guarantee. Furthermore, senior counsel for Ramsay Health Care accepted that it was an “open question” as to whether the calculations set forth in reconciliation table with respect to “offsets”, “rebates” and the like were factually correct (see [33] above); if those calculations were correct, then no debt was owed to Ramsay Health Care by MediChoice and thus no debt was owed to Ramsay Health Care by Mr Compton.

70 It is true that Mr Compton had the opportunity to challenge the quantum of any indebtedness to Ramsay Health Care in the Supreme Court proceeding and chose not to do so. No evidence was filed in connection with the interim application seeking to explain why that decision was made. Although the analysis and reconciliation carried out by Ms Stevis in her affidavit described in [25] above had not been carried out before the Supreme Court proceeding was tried, it may be assumed that the factual materials underpinning that analysis and reconciliation were available before the Supreme Court trial and so the analysis and reconciliation could have been conducted. However, the focus for the bankruptcy court is not on the forensic choices made by the parties in the litigation which resulted in the judgment, but on the requirement that there be satisfactory proof of the petitioning creditor’s debt.

71 We do not consider the judgment of Hely J in Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Jeans (2005) 3 ABC(NS) 712; [2005] FCA 978, referred to by the primary judge, to be inconsistent with these principles. In that case, on the third day of the trial, the debtor asserted for the first time that he had not executed the guarantee as guarantor. Thereafter, application was made to the trial judge for leave to withdraw the debtor’s admission that he had duly executed the guarantee as guarantor and for leave to amend the pleadings to allege that a bank officer who had purportedly witnessed the debtor’s signature to the guarantee had forged that signature. The trial judge refused the leave sought. An appeal to the Full Court from that judgment was dismissed, and special leave to appeal to the High Court from the judgment of the Full Court was refused. Hely J considered, as a preliminary question, whether the Court ought to exercise its discretion to ‘go behind’ the judgment on which the creditor’s petition was based. His Honour determined the question in the negative. He considered the relevant principles at [13]-[16] and [21] in terms which are consistent with our discussion. The debtor contended that there had not been a fully contested hearing on the merits because he was precluded from raising as an issue in the proceeding his contention that he did not sign the guarantee as guarantor. He submitted that the case was analogous to a default judgment and substantial reasons had been given for questioning whether there really was a debt due to the petitioning creditor. His Honour rejected the submission, holding (at [18]) that the circumstances were far removed from a case in which a judgment was entered by default. There had been a fully contested hearing before the trial judge on the issue of the debtor’s liability under the guarantee, after the debtor had a reasonable opportunity to raise whatever grounds he wished to rely upon.

72 Hely J did say (at [18]) that “[a]s is always the case, the scope of the contest was determined by the respective cases put forward by the parties, who are ordinarily bound by the way in which they have chosen to conduct the proceedings.” But this statement should be read in the context of his Honour’s earlier discussion of the principles.

73 In the next paragraph, his Honour stated that the matters on which the debtor relied as enlivening the power of the Court to go behind the judgment of the trial judge were the same matters upon which he unsuccessfully relied in support of his application to withdraw his admission. He concluded (at [21]) that the fact that the debtor was shut out from raising the defence on which he now sought to rely because the proper administration of justice so required provided an insufficient foundation for the Court to go behind the judgment regularly obtained.

74 The facts of the present case are somewhat different. Here, Mr Compton was not shut out from raising the issue of quantum in the Supreme Court proceeding — rather, he chose not to — and the matters he relied on in seeking to ‘go behind’ the judgment were not the same as the matters that he had sought to rely on (successfully or unsuccessfully) in that proceeding. In any event, while it is generally the case in litigation that parties are held to the way in which they conduct their case, s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act requires proof that the debt on which the petitioning creditor relies is still owing, as Hely J recognised in his discussion of the principles. Similarly, the observations of Wigney J in Katter v Melham (No 2) (2014) 319 ALR 646 at [78] are to be read in the context of the discussion of the principles at [69]-[79] of that judgment.

75 The primary judge’s reasons for concluding that, even if the first basis were erroneous, the discretion to ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment would not have been exercised in favour of Mr Compton, are set out in [43] above. His Honour relied on the same considerations that had dictated the former conclusion, together with further considerations. The further considerations included that the factual materials upon which the reconciliation table was based were available to Mr Compton at the time of the Supreme Court proceeding and no explanation had been advanced on his behalf to explain why the quantum of indebtedness was not then put in issue or why the reconciliation had not previously been undertaken.

76 In relying on these matters, the primary judge again focused on Mr Compton’s conduct of the Supreme Court proceeding, rather than on whether there were reasons for questioning whether behind the judgment debt there was in truth and reality a debt due to Ramsay Health Care. His Honour referred to the “disturbing discrepancy” between what Ms Stevis said in the affidavit from her which was filed, though not read, in the Supreme Court proceeding and the evidence she gave in this Court. But there was no cross-examination of any of the deponents on the hearing of the interim application. Nor did Ramsay Health Care file evidence which critiqued either the methodology or the factual basis of Ms Stevis’s evidence in this Court. Further, Ms Stevis’s conclusion that Ramsay Health Care in fact owed money to MediChoice, rather than the other way around, was supported by the opinion of the liquidators. The primary judge relied on the fact that there remained a number of outstanding inquiries and investigations as to the moneys owing as between MediChoice and Ramsay Health Care. But at this point, given the nature of the inquiry (a preliminary investigation as to whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment), the outstanding matters did not need to be resolved. To the extent that the primary judge considered that there was no reliable factual foundation to question whether there was in ‘truth and reality’ a debt owing, we would respectfully disagree.

77 As noted in paragraph [46] above, the primary judge concluded that there would be no “injustice” in bankrupting Mr Compton in the circumstances, given that he participated in a three day hearing in the Supreme Court; there was available evidence as to the quantum of any indebtedness to Ramsay Health Care; and he made a forensic decision not to put the question of quantum of any indebtedness in issue in circumstances where he was represented by counsel and solicitors. These reasons again focus on Mr Compton’s conduct of the Supreme Court proceeding rather than on whether there was reason for questioning whether behind the judgment debt there was in truth and reality a debt due to Ramsay Health Care. The primary judge said that “the highest that such evidence as is now available to this Court reaches as to the quantum of any indebtedness is that there remains an ‘open question’ whether there is any indebtedness”. This observation suggests that, if his Honour had applied the right test, he would have come up with a different answer.

78 For these reasons, we conclude that the primary judge erred. Given this conclusion, we consider afresh the question whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the Supreme Court judgment upon which the creditor’s petition is based. In considering this question, it is relevant to take into account that the judgment of the Supreme Court followed a fully contested hearing, at which Mr Compton appeared, and that he could have, but did not, raise the issue of the quantum of any indebtedness to Ramsay Health Care in that proceeding. Further, no explanation has been provided in the evidence as to why the issue of quantum was not raised in that proceeding. Nevertheless, this is an unusual case because there was no trial on the question of quantum and the evidence filed in connection with the interim application demonstrates, as Ramsay Health Care acknowledged, that there is an “open question” whether any debt is in fact owed by MediChoice to Ramsay Health Care and thus whether any debt is owed by Mr Compton to Ramsay Health Care pursuant to the guarantee (see [25]-[29], [31]-[33], [69] above). These circumstances demonstrate that there are substantial reasons for questioning whether behind the judgment debt there is in ‘truth and reality’ any debt owing to the petitioning creditor.

79 It follows that the question whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment of the Supreme Court should be answered in the affirmative.

Conclusion

80 For the reasons set out above, leave to appeal will be granted and the appeal allowed. Orders 1 and 2 of the orders made by the primary judge on 3 December 2015 (which were to the effect that the interim application be dismissed and Mr Compton pay Ramsay Health Care’s costs of the interim application) should be set aside. In lieu thereof, it should be ordered that the separate question (raised by the interim application) — whether the Court should ‘go behind’ the judgment of the Supreme Court of New South Wales upon which the creditor’s petition is based — be determined in the affirmative, and that the interim application otherwise be dismissed.

81 Costs should follow the event. The costs of the interim application should be reserved, pending the hearing of the petition. We will make orders to this effect. However, as the matter of costs was not the subject of submissions, if either party seeks a variation of these orders, written notice may be given to the Court and the other party within two business days. In that event we will make orders for the filing of evidence and submissions and, unless either party, for good cause, requests an oral hearing, we will determine the question on the papers.

I certify that the preceding eighty-one (81) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Siopis, Katzmann and Moshinsky. |