FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Esso Australia Pty Ltd v The Australian Workers’ Union [2016] FCAFC 72

ORDERS

ESSO AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ABN 49 000 018 566) Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave to appeal be granted.

2. Declaration 4 made on 13 August 2015 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be declared:

“4. By operation of s 413(5) of the FW Act, from 6.01 pm on 6 March 2015 until 6.00 pm on 20 March 2015, all industrial action organised by the respondent and taken by the Esso employees in support of claims in relation to bargaining for a replacement enterprise agreement or enterprise agreements for the Esso Gippsland (Barry Beach Marine Terminal) Enterprise Agreement 2011, the Esso Gippsland (Longford and Long Island Point) Enterprise Agreement 2011 and the Esso Offshore Enterprise Agreement 2011 was unprotected industrial action.”

3. The appeal be otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 470 of 2015 | ||

BETWEEN: | THE AUSTRALIAN WORKERS’ UNION Appellant | |

AND: | ESSO AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ABN 49 000 018 566) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | SIOPIS, BUCHANAN AND BROMBERG JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 25 May 2016 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave to appeal be granted.

2. Declaration 3 made on 13 August 2015 be set aside.

3. The appeal be otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SIOPIS J:

1 I have had the considerable benefit of reading the reasons for judgment of Buchanan J. I agree with those reasons and with the orders proposed by Buchanan J.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Siopis. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BUCHANAN J:

Introduction

2 These two appeals, respectively by Esso Australia Pty Ltd (“Esso”) and The Australian Workers’ Union (“AWU”), a federally registered organisation of employees, arise from declarations and orders made by Jessup J on 13 August 2015 for reasons which were published on 24 July 2015 (Esso Australia Pty Ltd v The Australian Workers’ Union [2015] FCA 758; (2015) 253 IR 304).

3 In the proceedings before the primary judge Esso alleged that the AWU contravened a number of provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (“FW Act”) when it organised industrial action at Esso’s plant at Longford, Victoria.

4 The primary judge recorded the general nature of the activities in which the industrial action was organised as follows (at [2]-[7]):

2 The applicant [Esso] is in the business of the exploration for and the production of oil and gas, the refining of petroleum and the supply of fuels, including natural gas. Relevantly to the present proceeding, the applicant operates three onshore facilities in Gippsland, and a number (presently 23) of offshore platforms, and associated infrastructure, in Bass Strait. The onshore facilities are at Longford, Long Island Point and Barry Beach.

3 The Longford Plant is the onshore receiving point for all of the crude oil and gas produced by the applicant’s offshore platforms in Bass Strait. It consists of three separate gas plants, a crude oil stabilisation plant and an ethylene glycol plant. Two pipelines run 220 km from Longford to Long Island Point, carrying crude oil for storage and distribution and gas liquids for final processing and distribution. These pipelines are managed and maintained by Longford-based personnel.

4 Hydrocarbons recovered from the seafloor are initially separated, at the offshore platforms, into two streams consisting of unstabilised crude oil and raw gas. These streams are piped separately to the plant at Longford, where impurities are removed and the two streams processed into stabilised products. These products are methane gas, which is sold directly to customers as natural gas, heavier hydrocarbon liquids (ethane and LPG), and stabilised crude oil. The LPG and the crude oil are sent for further processing and storage at Long Island Point.

5 Operations (ie as distinct from maintenance) personnel employed by the applicant at the facilities referred to are represented industrially by the respondent. They, and other personnel, are covered by industrial agreements approved under the FW Act, namely –

• the Esso Gippsland (Longford and Long Island Point) Enterprise Agreement 2011, which covers employees at two of the applicant’s onshore processing operations (Longford and Long Island Point);

• the Esso Offshore Enterprise Agreement 2011, which covers employees at the applicant’s offshore oil and gas platforms; and

• the Esso Gippsland (Barry Beach Marine Terminal) Enterprise Agreement 2011, which covers employees at the applicant’s Barry Beach Marine Terminal.

The nominal expiry date of each of these agreements (see FW Act, s 186(5)) was 1 October 2014.

6 Since about June 2014, the applicant and the unions representing its employees, including the respondent, have been engaged in bargaining for the making of a new enterprise agreement, or agreements, to take the place of those referred to in the previous paragraph. The respondent is a bargaining representative for the applicant’s operations employees. It is clear that much has happened in that bargaining, including, at times, proceedings in the Fair Work Commission (“the Commission”). Save to the extent mentioned below, it is not necessary to refer further to those proceedings.

7 I shall further address the applicant’s operations in some detail in the next section of these reasons, but, by way of broad introduction, I indicate now that the setting for the controversy which has led the parties to court is the return to operational service of items of plant or equipment which have earlier been taken out of service to have some work, such as repair, maintenance or upgrading, carried out on them. That work will normally have been carried out either by the applicant’s own maintenance personnel or by specialised contractors. The present case is not directly concerned with this work. The employees whose work is directly relevant, rather, are the operational personnel employed by the applicant. They control and monitor the plant and equipment in its normal operating state. They also have responsibilities at the point of removing plant and equipment from service for work to be done on it, and at the point of returning plant and equipment to service after the work has been completed. The industrial action organised at Longford which became the subject of this case was directed to the latter area of activity.

(Emphasis added.)

5 As to the character of the operation at Longford, the primary judge said (at [8]):

8 The applicant’s operations at Longford involve the processing of highly toxic, volatile, pressurised and flammable products. Plant and equipment required to process these products involves heat, flame and pressure. Potential ignition sources are adjacent to highly flammable hydrocarbons. The risk of fire or explosion is ever-present …

6 In the period after the nominal expiry date of the three agreements had passed, the AWU gave a number of notices of intention to take “protected industrial action” (see FW Act s 413(4) and s 414) to assist its claims for new enterprise agreements, or for a single enterprise agreement. The course of those notifications, and some consequent proceedings before the Fair Work Commission (“FWC”) are described in the primary judgment. It is not necessary to repeat all those details in this judgment.

7 On Esso’s application, the FWC made a number of orders under s 418 of the FW Act that industrial action stop, or not occur. When some forms of industrial action continued, Esso commenced proceedings in this Court alleging various contraventions of the orders made by the FWC, and of the FW Act.

8 Esso’s case was partially successful. The orders made on 13 August 2015 reflect that partial success in the form of declarations that the AWU contravened the provisions of the FW Act in particular respects. There were to be further proceedings to consider questions of penalty and compensation.

9 The orders made on 13 August 2015 were interlocutory, rather than final, orders. Leave to appeal is required in order to challenge them.

10 Esso sought leave to appeal about particular respects in which its application did not succeed. The AWU sought leave to appeal about particular respects in which Esso’s application did succeed. At the hearing, the parties were informed that leave to appeal would be granted. Arguments on the appeals were then taken.

11 The primary judgment is detailed and thorough. It will not be possible to adequately extract, or summarise, it in all respects. However, it is possible to trace the legal issues presented by the two appeals by commencing with questions concerning the validity and operation of certain orders made by the FWC under s 418 of the FW Act, and then moving progressively to the other legal issues which are presented for decision by the two appeals.

12 For the time being, the legal issues may be described and discussed without being diverted to any particular extent by which appeal most directly concerns them.

Section 418

13 The first issue in the appeals concerns the proper construction of s 418(1) of the FW Act. Resolution of that question of construction does not depend upon the particular facts of the case. Once that task has been undertaken, other matters concerning the application of further provisions of the FW Act to the facts of the case may be considered.

14 Although some historical matters will need attention in connection with the initial issue of construction, an attempt should first be made to construe s 418(1) of the FW Act in its present, overall, statutory context.

15 The FW Act establishes a scheme for the negotiation and making of enterprise agreements (see generally Part 2-4 of “Chapter 2—Terms and conditions of employment”) and (in some circumstances) workplace determinations (see generally Part 2-5 of Chapter 2). Enterprise agreements and workplace determinations, when made, must specify a term of not more than four years (s 186(5), s 272(2)).

16 Section 417(1) and (2) of the FW Act provide:

417 Industrial action must not be organised or engaged in before nominal expiry date of enterprise agreement etc.

No industrial action

(1) A person referred to in subsection (2) must not organise or engage in industrial action from the day on which:

(a) an enterprise agreement is approved by the FWC until its nominal expiry date has passed; or

(b) a workplace determination comes into operation until its nominal expiry date has passed;

whether or not the industrial action relates to a matter dealt with in the agreement or determination.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

(2) The persons are:

(a) an employer, employee, or employee organisation, who is covered by the agreement or determination; or

(b) an officer of an employee organisation that is covered by the agreement or determination, acting in that capacity.

17 Industrial action, where that term is used in the FW Act, is given the meaning assigned by s 19 of the FW Act:

19 Meaning of industrial action

(1) Industrial action means action of any of the following kinds:

(a) the performance of work by an employee in a manner different from that in which it is customarily performed, or the adoption of a practice in relation to work by an employee, the result of which is a restriction or limitation on, or a delay in, the performance of the work;

(b) a ban, limitation or restriction on the performance of work by an employee or on the acceptance of or offering for work by an employee;

(c) a failure or refusal by employees to attend for work or a failure or refusal to perform any work at all by employees who attend for work;

(d) the lockout of employees from their employment by the employer of the employees.

Note: In Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union v The Age Company Limited, PR946290, the Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission considered the nature of industrial action and noted that action will not be industrial in character if it stands completely outside the area of disputation and bargaining.

(2) However, industrial action does not include the following:

(a) action by employees that is authorised or agreed to by the employer of the employees;

(b) action by an employer that is authorised or agreed to by, or on behalf of, employees of the employer;

(c) action by an employee if:

(i) the action was based on a reasonable concern of the employee about an imminent risk to his or her health or safety; and

(ii) the employee did not unreasonably fail to comply with a direction of his or her employer to perform other available work, whether at the same or another workplace, that was safe and appropriate for the employee to perform.

(3) An employer locks out employees from their employment if the employer prevents the employees from performing work under their contracts of employment without terminating those contracts.

Note: In this section, employee and employer have their ordinary meanings (see section 11).

(Emphasis in original.)

18 Thus, a wide range of industrial action is prohibited during the nominal term of an enterprise agreement.

19 Outside the nominal term of an enterprise agreement or workplace determination, industrial action is not, as such, prohibited by the FW Act. Some forms of industrial action, if stated conditions are met, may in addition be or become “protected industrial action”.

20 Section 418 finds its place in the statutory arrangements which revolve around the notion of protected industrial action. I shall return to the text of s 418 shortly.

21 Three forms of protected industrial action are identified by s 408 of the FW Act. They relate to industrial action which is organised or engaged in for supporting or advancing claims in relation to an enterprise agreement, or in response to such action, or in response to the response. The three forms of protected industrial action are employee claim action for the agreement (see more particularly s 409), employer response action (see more particularly s 411) and employee response action (see more particularly s 410). Each form of industrial action must, in order to be protected industrial action, meet the “common requirements” stated in s 413.

22 Section 413 provides:

413 Common requirements that apply for industrial action to be protected industrial action

Common requirements

(1) This section sets out the common requirements for industrial action to be protected industrial action for a proposed enterprise agreement.

Type of proposed enterprise agreement

(2) The industrial action must not relate to a proposed enterprise agreement that is a greenfields agreement or multi-enterprise agreement.

Genuinely trying to reach an agreement

(3) The following persons must be genuinely trying to reach an agreement:

(a) if the person organising or engaging in the industrial action is a bargaining representative for the agreement—the bargaining representative;

(b) if the person organising or engaging in the industrial action is an employee who will be covered by the agreement—the bargaining representative of the employee.

Notice requirements

(4) The notice requirements set out in section 414 must have been met in relation to the industrial action.

Compliance with orders

(5) The following persons must not have contravened any orders that apply to them and that relate to, or relate to industrial action relating to, the agreement or a matter that arose during bargaining for the agreement:

(a) if the person organising or engaging in the industrial action is a bargaining representative for the agreement—the bargaining representative;

(b) if the person organising or engaging in the industrial action is an employee who will be covered by the agreement—the employee and the bargaining representative of the employee.

No industrial action before an enterprise agreement etc. passes its nominal expiry date

(6) The person organising or engaging in the industrial action must not contravene section 417 (which deals with industrial action before the nominal expiry date of an enterprise agreement etc.) by organising or engaging in the industrial action.

No suspension or termination order is in operation etc.

(7) None of the following must be in operation:

(a) an order under Division 6 of this Part suspending or terminating industrial action in relation to the agreement;

(b) a Ministerial declaration under subsection 431(1) terminating industrial action in relation to the agreement;

(c) a serious breach declaration in relation to the agreement.

(Emphasis added in s 413(4).)

23 Section 414 provides:

414 Notice requirements for industrial action

Notice requirements—employee claim action

(1) Before a person engages in employee claim action for a proposed enterprise agreement, a bargaining representative of an employee who will be covered by the agreement must give written notice of the action to the employer of the employee.

(2) The period of notice must be at least:

(a) 3 working days; or

(b) if a protected action ballot order for the employee claim action specifies a longer period of notice for the purposes of this paragraph—that period of notice.

Notice of employee claim action not to be given until ballot results declared

(3) A notice under subsection (1) must not be given until after the results of the protected action ballot for the employee claim action have been declared.

Notice requirements—employee response action

(4) Before a person engages in employee response action for a proposed enterprise agreement, a bargaining representative of an employee who will be covered by the agreement must give written notice of the action to the employer of the employee.

Notice requirements—employer response action

(5) Before an employer engages in employer response action for a proposed enterprise agreement, the employer must:

(a) give written notice of the action to each bargaining representative of an employee who will be covered by the agreement; and

(b) take all reasonable steps to notify the employees who will be covered by the agreement of the action.

Notice requirements—content

(6) A notice given under this section must specify the nature of the action and the day on which it will start.

(Emphasis added in s 414(6).)

24 Thus, at least one requirement to be met, if industrial action is to be protected industrial action, is that notice be given which specifies the nature of the action and when it will commence.

25 One important consequence of the fact that action is protected industrial action is stated by s 415:

415 Immunity provision

(1) No action lies under any law (whether written or unwritten) in force in a State or Territory in relation to any industrial action that is protected industrial action unless the industrial action has involved or is likely to involve:

(a) personal injury; or

(b) wilful or reckless destruction of, or damage to, property; or

(c) the unlawful taking, keeping or use of property.

(2) However, subsection (1) does not prevent an action for defamation being brought in relation to anything that occurred in the course of industrial action.

26 It is in the context set by the foregoing provisions that s 418 operates. The essential premise for its operation, and the effectiveness of the orders which it permits, is that the requirements for protected industrial action have not been met. Section 418 provides:

418 FWC must order that industrial action by employees or employers stop etc.

(1) If it appears to the FWC that industrial action by one or more employees or employers that is not, or would not be, protected industrial action:

(a) is happening; or

(b) is threatened, impending or probable; or

(c) is being organised;

the FWC must make an order that the industrial action stop, not occur or not be organised (as the case may be) for a period (the stop period) specified in the order.

Note: For interim orders, see section 420.

(2) The FWC may make the order:

(a) on its own initiative; or

(b) on application by either of the following:

(i) a person who is affected (whether directly or indirectly), or who is likely to be affected (whether directly or indirectly), by the industrial action;

(ii) an organisation of which a person referred to in subparagraph (i) is a member.

(3) In making the order, the FWC does not have to specify the particular industrial action.

(4) If the FWC is required to make an order under subsection (1) in relation to industrial action and a protected action ballot authorised the industrial action:

(a) some or all of which has not been taken before the beginning of the stop period specified in the order; or

(b) which has not ended before the beginning of that stop period; or

(c) beyond that stop period;

the FWC may state in the order whether or not the industrial action may be engaged in after the end of that stop period without another protected action ballot.

(Emphasis in original.)

27 Section 418 calls for an assessment by the FWC about whether industrial action (i.e. as defined in s 19) that is happening, threatened etc or being organised is, or would be, protected industrial action. That assessment by the FWC could not be legally conclusive, but it is an important preliminary step nevertheless (see Re Cram; Ex parte The Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company Proprietary Limited (1987) 163 CLR 140 at 149). The assessment to be made by the FWC requires identification of the existing or potential industrial action as a matter of fact, or probable fact.

28 The requirement on which s 418 operates is that the FWC may conclude that the industrial action is not protected or would not be protected if it took place although it may not be possible, in some cases of industrial action which is being organised or threatened, to say with any certainty what action is proposed because it cannot be assumed that notice of the kind referred to in s 414(6) has been provided. In fact, no steps at all may have been taken to attempt to meet the “common requirements” for protected industrial action.

29 Nevertheless, the power of the FWC under s 418(1) is to order that the industrial action stop or not occur or not be organised, even though the FWC does not need to specify the particular industrial action (s 418(3)).

30 Is it open to the FWC under s 418 simply to order that no industrial action (i.e. as defined by s 19), which is not protected industrial action, occur for a specified period (the stop period)? In my view, it is not.

31 First of all, I see no reason to doubt that the FWC must, for the purpose of its own assessment, make some attempt to identify the existing or potential industrial action. Then it must form a view whether that existing or potential industrial action is or would be protected industrial action.

32 Perhaps in a case where the industrial action was occurring, threatened or being organised during the term of an enterprise agreement or workplace determination, little would turn on the precise character of the industrial action but, on the other hand, s 417 needs nothing by way of assistance from s 418.

33 The more critical case (perhaps the only practical case) for the invocation of s 418 will arise from concern about industrial action (actual or potential) outside the nominal term of an enterprise agreement or workplace determination. In such a case, as I have said, some effort must be made by the FWC, before issuing an order, to establish that the statutory foundation for the order is present. Similarly, the scope of the order cannot simply be at large because it must be directed at the industrial action (existing or potential) which has been identified.

34 In my view, it is an abdication of the responsibilities of the FWC to make an order which simply states that industrial action must not occur which is not protected industrial action. If industrial action is not protected industrial action then the immunity from suit given by s 415 will not apply. An order under s 418 does not adjust the operation of s 415. An order under s 418 need not be complied with if industrial action is, or would be, protected industrial action (s 421(2)). However, otherwise, breach of an order under s 418 is an offence (see s 675) whether or not supported by an injunction under s 421.

35 My view is reinforced by consideration of the operation of s 419, which forms part of the scheme of the same Division of Part 3-3 of Chapter 3 of the FW Act.

36 Section 407 identifies the employees and employers, to which Part 3-3 applies, to be national system employees and national system employers, terms which are defined by ss 13 and 14(1) (relevantly) as follows:

13 Meaning of national system employee

A national system employee is an individual so far as he or she is employed, or usually employed, as described in the definition of national system employer in section 14, by a national system employer, except on a vocational placement.

Note: Sections 30C and 30M extend the meaning of national system employee in relation to a referring State.

(Emphasis in original.)

14 Meaning of national system employer

(1) A national system employer is:

(a) a constitutional corporation, so far as it employs, or usually employs, an individual; or

(b) the Commonwealth, so far as it employs, or usually employs, an individual; or

(c) a Commonwealth authority, so far as it employs, or usually employs, an individual; or

(d) a person so far as the person, in connection with constitutional trade or commerce, employs, or usually employs, an individual as:

(i) a flight crew officer; or

(ii) a maritime employee; or

(iii) a waterside worker; or

(e) a body corporate incorporated in a Territory, so far as the body employs, or usually employs, an individual; or

(f) a person who carries on an activity (whether of a commercial, governmental or other nature) in a Territory in Australia, so far as the person employs, or usually employs, an individual in connection with the activity carried on in the Territory.

Note 1: In this context, Australia includes the Territory of Christmas Island and the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (see paragraph 17(a) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901).

Note 2: Sections 30D and 30N extend the meaning of national system employer in relation to a referring State.

(Emphasis in original.)

37 Section 419 operates with a very similar mechanism to s 418. It provides:

419 FWC must order that industrial action by non-national system employees or non-national system employers stop etc.

Stop orders etc.

(1) If it appears to the FWC that industrial action by one or more non-national system employees or non-national system employers:

(a) is:

(i) happening; or

(ii) threatened, impending or probable; or

(iii) being organised; and

(b) will, or would, be likely to have the effect of causing substantial loss or damage to the business of a constitutional corporation;

the FWC must make an order that the industrial action stop, not occur or not be organised (as the case may be) for a period specified in the order.

Note: For interim orders, see section 420.

(2) The FWC may make the order:

(a) on its own initiative; or

(b) on application by either of the following:

(i) a person who is affected (whether directly or indirectly), or who is likely to be affected (whether directly or indirectly), by the industrial action;

(ii) an organisation of which a person referred to in subparagraph (i) is a member.

(3) In making the order, the FWC does not have to specify the particular industrial action.

38 Section 419, therefore, is concerned with conduct (industrial action) by persons normally outside the operation of the FW Act which potentially causes “substantial loss or damage to the business of a constitutional corporation”. Like the basis upon which s 418 operates, s 419 states the satisfaction of the FWC about that matter as the foundation for its obligation to make an order. In the case of s 419, it is quite clear that the FWC could not simply make an order in general terms stopping all industrial action regardless of its effect. That would be to use the power for a purpose which was not its intended one. Such an order would be ultra vires in my view.

39 Similarly, orders made under s 418 are confined within the statutory limits for which the power is granted. The order must relate to the industrial action which triggers the statutory obligation.

40 Without resort to history or authority, therefore, I would construe s 418(1) as limited to orders where, so far as the circumstances permit, the order operates in relation to, and is confined to, the industrial action (existing or potential) which the FWC has decided is not, or would not be, protected industrial action, having regard to the reasons for that conclusion which may be quite particular.

41 What, then, of history and authority?

42 In the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (“WR Act”) when it was enacted, s 127(1) provided a power to the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (“AIRC”), similar to that in s 418 of the FW Act, but referring only to industrial action, without reference to protected industrial action. In Metal Trades Industry Association of Australia v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union [1997] FCA 1355; (1997) 77 IR 87 (“MTIA”), Marshall J considered an order which was made simply prohibiting industrial action as defined by s 4 of the WR Act. Marshall J refused to grant an interim injunction restraining breach of the order, in part because (at 92):

… the order is void because it fails to adequately specify the particular conduct which it seeks to prohibit. …

43 By later amendments to the WR Act in 2006, the effect of s 127 was replaced by s 496 of the WR Act. Section 496(1) and (9) are a sufficient parallel with s 418(1) and (3) of the FW Act. In Transport Workers’ Union of New South Wales v Australian Industrial Relations Commission (2008) 166 FCR 108 (“TWU”), Gray and North JJ considered the effect of s 496(1) of the WR Act. An order had been made which simply prohibited industrial action by reference to the definition of that term in s 420 of the WR Act, although excluding protected industrial action. The AIRC had not found that industrial action was threatened etc; but that it was occurring. Gray and North JJ said (at [21] and [24]):

21 In the present case, it appeared to Senior Deputy President Hamberger that industrial action, not being protected action, was happening. So much is evident from [6] of the Senior Deputy President’s reasons. There was no finding that it appeared to the Commission that industrial action was threatened, impending or probable, or was being organised. On that basis, the Commission was limited to making an order that the industrial action stop. …

…

24 For present purposes, it is enough to say that, in the absence of any finding other than that industrial action, not being protected action, by employees was happening, the Commission had no power to go beyond the making of orders that the industrial action stop. Without it appearing to the Commission that industrial action was threatened, impending or probable, the Commission was under no duty, and had no power, to make any order that the industrial action not occur. Similarly, in the absence of a finding that the industrial action was being organised, the Commission had no duty, and no power, to make an order that the industrial action not be organised.

44 Later, their Honours said (at [39]):

39 It is also necessary to bear in mind that the duty of the Commission to make orders is confined by s 496(1) of the WR Act to orders that “the industrial action stop, not occur and not be organised”. The reference to “the” industrial action is a reference to industrial action that appears to the Commission to be happening, to be threatened, impending or probable, or to be in the process of being organised. It is necessary for the Commission to identify the industrial action that appears to it to be happening, threatened, impending or probable, or being organised, and to make orders that that industrial action stop, not occur or not be organised, as the case may be. Section 496(1) contains neither a duty nor a power to make orders that any act or omission that might possibly fall within the definition of “industrial action” in s 420 of the WR Act stop, not occur or not be organised. The Commission’s duty, and power, is limited to the industrial action that is the subject of the application before it.

(Emphasis added.)

45 One difficulty with their Honours’ analysis and conclusion (which was to a similar effect to Marshall J in MTIA) is that no reference was made to s 496(9). Section 496(9) appeared to have been introduced to address, and overcome, the conclusion of Marshall J in MTIA. The absence of any discussion of its operation in TWU makes that latter case an unsafe authority on this issue, as is the judgment in MTIA.

46 However, those difficulties do not attend the judgment under appeal, where the primary judge dealt with all of them.

47 Before I turn to that, I should mention that reference was made in argument to what was said about s 418(3) of the FW Act (the counterpart of s 496(9) of the WR Act), in the Explanatory Memorandum:

1689. In making an order to stop or prevent industrial action, FWA does not have to specify the particular industrial action (subclause 418(3)). This is intended to allow FWA to make effective orders that do not require the separate identification of each particular instance of industrial action.

48 I regret to say that, like so many paraphrases of this kind, this statement does not assist much although it does to my mind suggest that some specificity was contemplated – e.g. sufficient to disclose the legal operation of the order and provide sufficient certainty to allow compliance with it.

49 The FWC orders considered by the primary judge, to some extent or other, prohibited industrial action by reference to the statutory definition (here s 19 of the FW Act).

50 Relevant parts of the primary judge’s reasoning about the construction of s 418(1) and (3) included the following (at [107]-[111], [114]-[116]):

107 … the obligation to make orders, expressed in the main clause of the sentence which constitutes subs (1), is to be read distributively. That is to say, for example, unless the Commission had found that unprotected industrial action was being organised, the Commission would have no power to order that it not be organised. This is one aspect of the view about s 496(1) taken by Gray and North JJ in Transport Workers’, notwithstanding that this dimension of the subsection was then expressed less clearly than it is in s 418(1) of the FW Act: see (166 FCR at 120-121 [17]).

108 … subs (3) permits the Commission to frame its order in a way that does not “specify the particular industrial action”. That is to say, it is permissible for the industrial action to be identified without specification of whether it is, or would be, a work stoppage, a ban, or something else. But that does not mean that the Commission can go beyond the findings made under subs (1). Nor, in my view, does it mean that the Commission can frame its order by reference to “industrial action”, without more. The order which it is required to make may not extend beyond “the” industrial action which has been found to be happening, to be threatened, etc.

109 If these observations are sound ones, the question will inevitably arise: if the Commission is limited to the industrial action which was the subject of its findings under s 418(1), but is not required to specify the form that the industrial action being prohibited by its order might take, how is it to be expected to identify the subject-matter of its prohibition? A ready, but rather unsatisfying, answer to that question would be to say that the operation of s 418 in the way I have expressed it is sufficiently clear to make recourse to practical issues such as this both unnecessary and impermissible as on matters of construction. A more satisfying answer would be to recognise that the section contemplates that the Commission must, or at least will normally, identify the industrial action in some way. This may involve specifying the particular industrial action: the existence of subs (3) does not mean that the Commission may not so proceed. Or it may make use of some other identifier which makes sense to the parties in the facts of the case, such as the purpose of the action, the place in which it is to occur, the timing of the action, or something else. The point here is that the existence of subs (3) does not, as a matter of construction, involve the proposition that the Commission no longer need identify the industrial action which is being prohibited by its order, or the conclusion that, in making its order, the Commission may travel beyond the scope of “the” industrial action, the subject of its findings under subs (1).

110 … Although the issue does not arise for resolution in the present case and I have not been addressed upon it, I would offer the tentative view that the mere inclusion of a term in an order that the order did not apply to protected industrial action, made in circumstances where the Commission had not made a positive finding that the industrial action which it had found to be happening etc was not, or would not be, protected industrial action, would not be within power under the section.

111 Applying the foregoing legal analysis to the facts of the case, I commence with the order made by the Commission on 17 February 2015 (see para 38 above). Reading the definition of “industrial action” (cl 3.1) into the operative provision (cl 4.1), the order prohibited the respondent from organising, and the employees from engaging in, any industrial action within the definition in s 19 of the FW Act, including action of the kinds referred to in paras (a)-(d) of cl 3.1, but excluding action of the kinds referred to in paras (e)-(g) of that clause. For the reasons I have given above, I consider that, if the definition had referred only to the overtime ban the subject of para (d) – the subject, and the only subject of the Commission’s findings under subs (1) – the order would have been within power under s 418. On the other hand, if it had referred only to the definition in s 19, or to that definition together with the inclusions set out in paras (a)-(c), the order would have been beyond power. Either way, in my view, the exclusionary provisions of paras (e)-(g) would not affect the result.

…

114 I would add that the specific inclusion of industrial action of the kind referred to in cl 3.1(d) bespeaks an intention on the part of the Commission that, whatever else might be conveyed by the terms of the order, there should be no doubt but that that industrial action was caught thereby. It is as though the Commission contemplated that there might be persons bound by the order who were unaware of the terms of s 19 of the FW Act, or to whom the legislative jargon used in paras (a)-(c) might not be familiar. The reference to the overtime ban at Longford in para (d) had the purpose, I infer, of putting up in lights the specific matter which had brought the parties to the Commission. There is every reason to suppose that the Commission intended that this aspect of the order, if no other, should operate.

115 It will be clear from my reasons above that I take the view that the Commission’s order of 5 March 2015 had, and has, no valid operation.

116 With respect to the Commission’s order of 6 March 2015, the position is, mutatis mutandis, the same as that reached above in relation to the order of 17 February 2015. The Commission had found that the respondent was organising, and that its members were implementing, bans on equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing. Paragraphs (a) and (b) of cl 3.1 of the order referred specifically to industrial action of that kind and, by reason of the operation of s 46(2) of the AI Act, the order was within power to that extent. The order did, however, have no wider valid operation.

(Bold emphasis added.) (Italic emphasis in original.)

51 The primary judge thus applied a “blue pencil” test confining two orders within the statutory limits which he had identified, and preserving their operation with respect to the industrial action which had been adequately identified by the FWC, namely (order made on 17 February 2015):

3. DEFINITIONS

3.1 For the purposes of this Order, ‘Industrial Action’ has the meaning prescribed by section 19 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Act) and includes:

…

(d) … a ban on the performance of overtime contrary to the Esso Gippsland (Longford and Long Island Point) Enterprise Agreement 2011 and contrary to custom and practice regarding availability for and the performance of overtime;

…

(Emphasis in original.)

and (order made on 6 March 2015):

3. DEFINITIONS

3.1 Subject to 3.2, for the purposes of this Order, ‘Industrial Action’ has the meaning prescribed by section 19 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Act) and includes:

(a) the performance of work in a manner different from that in which it is customarily performed, or the adoption of a practice in relation to work the result of which is a restriction or limitation on, or a delay in, the performance of equipment testing, air freeing, and leak testing;

(b) a ban, limitation or restriction on the performance of work on the performance of equipment testing, air freeing, and leak testing.

…

52 Orders which lacked that kind of specificity were found to be invalid.

53 The orders set out above, which the primary judge found to be valid, are accepted to have been validly made, at least to that extent. Esso argued that s 418(3) required that they not be so confined but in my view they provide a very good illustration of the practical operation of s 418(3) which supports the approach taken by the primary judge.

54 The orders which survived identify industrial action by its nature and character. There is no doubt that the identification of that industrial action in that way is meaningful for the parties. At the same time, it may fairly be said that the orders do not (in this instance) identify the “particular industrial action” which will be prevented by their terms. It should be emphasised that orders of this kind may descend to that level of particularity if the FWC thinks it appropriate, but they need not do so. What they may not do is move beyond the industrial action identified as the foundation for making the order as required by s 418(1).

55 In my respectful view, the approach taken by the primary judge was the correct one. The orders made by the FWC were valid only to the extent identified.

56 The primary judge found that the AWU had breached the s 418 order made on 6 March 2015 in three respects. Those findings were reflected in the following declarations made on 13 August 2015:

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent contravened section 421(1) of the FW Act by contravening clause 4.1 of the Third s 418 Order, by its conduct in organising unprotected industrial action to be taken by the Longford members in the form of a ban on air freeing and leak testing from 6:00 pm on 6 March 2015 until 9:30 am on 7 March 2015.

2. The respondent contravened section 421(1) of the FW Act by contravening clause 4.1 of the Third s 418 Order, by its conduct in organising unprotected industrial action to be taken by the Longford members in the form of a ban on the manipulation of bleeder valves from 9:30 am on 7 March 2015 until the making of the Court’s interim order on 17 March 2015.

3. The respondent contravened section 421(1) of the FW Act by contravening clause 5.1(a) of the Third s 418 Order, by its conduct in failing to prepare a Written Notice as soon as practicable following 6:00 pm on 6 March 2015, as required by clause 5.1(a) of the Third s 418 Order.

57 In the next two sections of the judgment I will deal first with aspects of the subject matter of declarations 1 and 2 and then with declaration 3.

De-isolation

58 The next issue concerns the contention by the AWU that those parts of the order made on 6 March 2015, which had been found not to fail for non-compliance with s 418 of the FW Act, nevertheless failed to identify industrial action which was not, or would not be, protected industrial action. Specifically, “a ban, limitation or restriction on the performance of work on the performance of equipment testing, air freeing, and leak testing” (cl 3.1(b) of the order made on 6 March 2015) was said by the AWU to be protected industrial action because it was embraced by a notice of intended industrial action given on 3 February 2015, as follows:

…

Employee claim action:

…

e) An indefinite ban on the de-isolation of equipment by employees covered by the Agreements commencing at 12.01 a.m. on Thursday, 12 February 2015.

…

59 In an application for an order under s 418 relating to this issue on 5 March 2015, Esso said:

4.4 Following the issuance of the Notice, the Employees engaged in a ban on the performance of de-isolation of equipment at the Longford Plant.

4.5 Esso responded by arranging for its managerial and supervisory employees to carry out that task.

4.6 Since 2 March 2015, the Employees have expanded their ban to testing procedures associated with the recommissioning of plant and equipment. In particular, the Employees have refused to perform equipment testing, air freeing, and leak testing (the Action).

4.7 In recent days, Esso managers have pointed out to the AWU that the Action is not protected industrial action because it is not covered by the Notice. The AWU, through the local delegate Rob Steed and the Victorian Branch Secretary Ben Davis, confirmed that: (i) the Action was in place; and (ii) the Action would continue because the AWU regarded the Action as part of the notified ban on de-isolation of equipment.

60 The respective positions of the parties may be seen clearly enough from this extract. Esso was saying that the notified ban on de-isolation of equipment did not include equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing, but had as a matter of practice been extended to those activities subsequently. The AWU said that the notified ban had always, in terms, so extended.

61 The FWC agreed with the position put by Esso, and made the order on 6 March 2015 which contained the part of the order on that day which the primary judge found survived the challenge to validity based on s 418.

62 The primary judge also found that the work of equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing did not fall within the notified ban on de-isolation of equipment.

63 The result was that the AWU breached s 421 of the FW Act by contravening an order made under s 418.

64 The specific factual allegations of contravention relating to this issue were stated as follows (at [118]):

118 The contraventions of s 418 orders alleged against the respondent are the following:

(a) organisation of a ban on air freeing and leak testing imposed by its members at Longford on and from 2 March 2015;

…

(d) organisation of a ban on the performance of bleeder valve manipulation “as part of air freeing and leak testing” imposed by its members at Longford on and from 7 March 2015.

65 The primary judge’s ultimate findings were as follows (at [119]-[120], [126]):

119 With respect to allegation (a) on this list, the only valid order under s 418 which applied to the ban on air freeing and leak testing was that made on 6 March 2015. That order came into effect at 6 pm that day. It was not until about 9.30 am on 7 March 2015 that Mr Jones, conformably with the advice which he had received from Mr Tschugguel, informed Mr Lloyd that he would perform leak testing. I infer that members of the respondent would also have performed air freeing if required (subject, of course, to the ban covered by allegation (d) on the list). There was, therefore, a period of about 15 hours during which members of the respondent at Longford maintained a ban on air freeing and leak testing in contravention of the Commission’s order of 6 March 2015. It is uncontroversial that the respondent organised that ban.

120 With respect to allegation (d) on the list above, there was a ban on the performance of bleeder valve manipulation, although the respondent would regard the applicant’s qualifier “as part of air freeing and leak testing” as tendentious. The ban, of course, was imposed only when valves had to be manipulated in preparation for – or, as the respondent would have it, as an element of – the “de-isolation of equipment”, the term used in the respondent’s s 414 notice. In the context of the Commission’s order of 6 March 2015, the question is not whether the manipulation of bleeder valves was part of air freeing and leak testing, but whether the ban on the manipulation of bleeder valves amounted to the adoption of a practice in relation to work the result of which was a restriction or limitation on, or a delay in, the performance of air freeing or leak testing within the meaning of cl 3.1(a) of that order. The question needs only to be stated in those terms for an affirmative answer to be self-evident. I would hold that, by organising this ban, the respondent contravened the order of 6 March 2015 from about 9.30 am on 7 March 2015 until the making of the court’s interim order of 17 March 2015.

…

126 Because they were not covered by any notice under s 414, the respondent’s bans on air freeing and leak testing, and later on bleeder valve manipulation associated with those functions, were not protected industrial action within the meaning of the FW Act.

66 Those findings followed an extensive discussion of the positions put by Esso and the AWU about the meaning conveyed by the notice of 3 February 2015 and, in particular, what was meant and should be understood by a reference to a “ban on the de-isolation of equipment”.

67 Important aspects of that discussion, and the evidence relied upon by the parties, concerned the significance of parts of Esso’s Work Management System (“WMS”) manual.

68 When the primary judge introduced his discussion of what was conveyed by the notice he said (at [66], [69]-[70]):

66 As mentioned above, on 3 February 2015 the respondent notified the applicant of a ban on the “de-isolation of equipment”. An important question is whether that notification covered the respondent’s members’ refusal to carry out air freeing and leak testing and, from 7 March 2015, their refusal to manipulate bleeder valves.

…

69 The applicant’s complaint is not that the respondent’s notice of 3 February 2015 was bad for want of sufficient specificity. Indeed, the applicant says that it well understood what was conveyed by the notice: the de-isolation of equipment in the defined sense under the WMS manual, which involved, it is said, both positive and negative aspects. Positively, the WMS manual provided a definition which referred to unlocking and moving isolation valves, reconnecting systems, removing blinds, and unlocking electrical switches to their normal operating state. Negatively, the WMS manual provided separate definitions of “air freeing” and “leak testing”, thereby suggesting that these operations were not the same as de-isolations. Either way, it is said, the respondent’s notice should be understood as a reference to de-isolation of equipment as such, and as not including air freeing, leak testing or the manipulation of bleeder valves preparatory to, or associated with, those tasks.

70 By contrast, it was submitted on behalf of the respondent that the term “de-isolation of equipment” had an accepted, and well-understood, meaning at Longford. It was by reference to that meaning that the applicant’s management would have understood the respondent’s notice of 3 February 2015. In considering this submission, it is necessary to commence with the purely factual question whether there was such an accepted and well-understood meaning, both on the part of the operators employed by the applicant and on the part of the managers whose function it was to consider what was conveyed by the notice.

69 His Honour then referred to aspects of the evidentiary case for both parties which he had earlier set out in detail (at [8]-[28]). Further detail was given (at [71]-[83]). Then, the primary judge said (at [84]):

84 All things considered, I am not persuaded that, in a normal operational setting at Longford, the term “de-isolation of equipment” had an accepted, and well-understood, meaning as proposed by the respondent [the AWU]. To the contrary, at least in a practical context involving the identification of work and tasks, the term related to de-isolation as such. When air freeing and pressure testing were required to be carried out, they were referred to in terms – either those terms or, in the case of the former, “purging”, and, in the case of the latter “leak testing”.

70 This conclusion was seen by the primary judge to be consistent with the operational practices and directions contained in the WMS manual, which set out in detail the procedures and processes relevant in relation to the “work permit” systems and isolation procedures. The primary judge had earlier observed at [11]:

11 The detailed processes in relation to work permits and isolation procedures are prescribed in a separate procedures manual, called the Work Management System (“WMS”) manual. All operations personnel employed by the applicant have been trained in the provisions of this manual, and refresher training is also undertaken. The WMS manual is available at the relevant workplaces, in both electronic and paper forms. Some of the relevant definitions contained in the WMS manual are the following: …

71 Some definitions in the WMS manual were as follows (there arranged alphabetically):

De-isolations | Unlocking and moving isolation valves, reconnecting systems, removal of blinds, and unlocking electrical switches to their normal operating state. |

… | … |

Equipment testing | The process of temporarily de-isolating equipment and energizing to a live-state for operational testing or fault finding. |

… | … |

Air freeing | Removing oxygen from process equipment to prevent flammable mixtures occurring when hydrocarbons are reintroduced. |

… | … |

Leak testing | Introducing pressure to the system to confirm that integrity has been restored and there are no leaks. |

… | … |

(Italics in original.)

72 The introduction to Section 4.6 of the WMS manual, “Reinstating Facility Systems and Equipment” included:

Introduction | This section describes the procedures and precautions to be followed when reinstating equipment and facilities and defines personnel responsibilities. The general sequence of events, when reinstating equipment and facilities, is as follows: |

• Recommissioning | |

Note: Recommissioning is an activity that takes place throughout the reinstatement. Mechanical completion checks must be made before and after equipment testing, air freeing, leak testing, and de-isolating. | |

• Equipment testing | |

• Air freeing | |

• Leak testing | |

• Removing energy isolations (mechanical, electrical, instrument) | |

• Removing temporary defeats | |

• Acceptance testing | |

… |

73 The WMS goes on, in pages of detailed instructions, to deal separately with “Recommissioning”, “Equipment Testing”, “Leak Testing” and “Air Freeing”, before addressing procedures for “Removing Energy Isolations”. A general procedure is then stated as follows:

Energy isolation removal procedure | The following general procedure regarding energy isolation removal should be followed: |

• Upon completion of all recommissioning, leak testing, and air freeing, the Permit Holder brings the Isolation Control Certificate to the Area Operator or CCR and advises that the system is ready to be de-isolated. | |

• The Isolating Authority and Area Authority must confirm that it is safe to perform the requested de-isolations. | |

• The Area Operator must confirm that the isolated system has been recommissioned, leak tested, and air freed, if required. | |

• The Area Operator must confirm that no other planned or ongoing work requires any of the existing isolation points to remain isolated. | |

• The Area Operator collects the original and all copies of the Isolation Control Certificate and requests the Area Authority to approve for reinstatement. The Area Authority approves the de-isolation activities to commence. | |

• For remote locations where the Area Authority is not present, the Area Operator or Permit Holder acts as the Area Authority and approves the de-isolation activities to commence. | |

• Once the Area Authority or designate has approved the de-isolation: | |

• The Permit Holders remove their Functional lock(s) from the isolation control point (ICP). | |

• The Area Operator removes his or her Functional lock from the ICP. | |

• The Isolating Authority obtains the key(s) from the ICP and removes the locks and tags the isolation points. | |

• The Area Operator is responsible for coordinating the de-isolating of the equipment. | |

• The Isolation Control Certificate (ICC) is closed out. |

(Emphasis added.)

74 Before the primary judge, Esso emphasised the separate identification of different stages in the overall recommissioning process, whereby equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing were not subsumed within the notion or process of de-isolation. Rather, before energy isolations are removed, any necessary equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing occurs.

75 The case for the AWU focussed on the part in the overall process which is played by a safety feature known as the Isolation Control Certificate (“ICC”). The AWU sought, at first instance and on appeal, to emphasise the importance of this feature and the alleged understanding of its purpose and function possessed by operators.

76 The primary judge (at [19]) referred to use of the ICC as follows:

19 Section 4.5 of the WMS manual refers to an electronic artefact known as the Isolation Control Certificate (“ICC”). There are designated persons responsible for preparing and issuing the ICC to record the fact that the isolation has been requested and approved. The ICC becomes part of the work permit documentation. According to the WMS manual, the ICC “must be used to document the isolation and approval of equipment or systems and will be used to track the status of all isolations”. …

and then went on to describe those arrangements in greater detail.

77 The AWU placed particular significance on a specific stage of that process, identified by an ICC heading in a drop down electronic version which was “De-isolation in Progress”.

78 The written submissions by the AWU in the present appeal accepted:

5. The purpose of a s. 414 notice is to enable an employer which is to become affected by protected action “to take appropriate defensive action”: Davids Distribution v NUW (1999) 91 FCR 463 (Davids) at 495 [87].

6. The description of the “nature of the action” should be in “ordinary industrial English”: Davids at [88]. Because such notices are often drawn by non-lawyers acting without legal advice, an approach to their interpretation that places a “premium on legalism” is to be eschewed: Davids at [86]; CFMEU v Yallourn Energy Pty Ltd (2000) 100 IR 52 at [21]; Tidewater Marine Australia Pty Ltd v MUA [2014] FCA 172 at [19]. An assessment of the adequacy of the description of the industrial action “must take account of all the circumstances and examine expressions used in the context of whether the concepts embodied in the expressions are well recognised in workplace relations”: CEPU v Pinnacle Career Development Pty Ltd (2010) 190 FCR 581 at [58].

7. Applying these authorities to the facts, the task of this Court is therefore to ascertain “the meaning which the [notice] would convey to a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation in which they were at the time [the notice was served]”: Maggbury P/L v Hafele Aust P/L.

(Footnote omitted.)

79 However, the AWU’s written submissions went on to pursue the issue as follows:

11. It was the AWU’s case that these various steps are referred to at Longford collectively as “de-isolation” because they are performed while the computerised work method known as the Isolation Control Certificate (ICC) is designated ‘de-isolation in progress’.

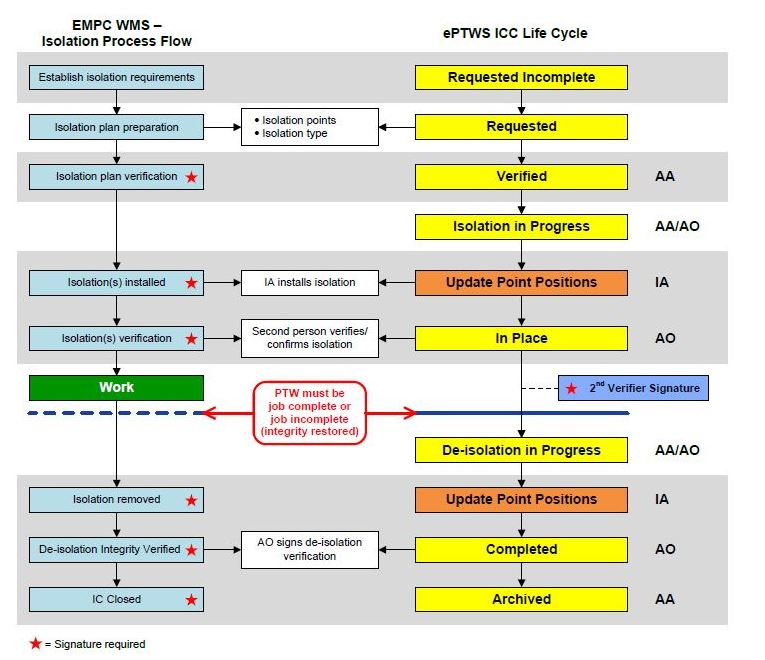

12. The ICC forms part of Esso’s Work Management System manual (WMS). The role of an ICC is explained on page 4-43 of the WMS. ICC’s are described in s.4.5.1 of WMS as the document by which energy isolations are managed. Section 4.5 (page 4-36) of the WMS describes the process of isolation, listing a series of actions that need to be taken. Isolation is a process. De-isolation is the re-instatement of the equipment to service, and it is submitted that, as a matter of consistency of interpretation, it too should be seen as a process. This proposition is confirmed in WMS at 4-38 which sets out the isolation process flow at Figure 4-7. It will be seen that that figure identifies a stage of “isolation in progress” and a later stage of “de-isolation in progress”.

(Emphasis added.) (Footnote omitted.)

80 By contrast, Esso submitted:

13 Turning to the AWU’s specific criticisms of the primary judge’s approach to this issue:

(a) … The AWU places almost total reliance on the ICC. In its terms, nothing in the ICC advances the AWU’s case. Paragraph 12 advances a flipside type of argument, but the terms of the WMS are directly inconsistent with the submission. The flipside “de-isolation process” as the AWU would have it, is actually called “Reinstating Facility Systems and Equipment” in the WMS, and within this process, equipment testing, air freeing, leak testing and de-isolating are clearly separate activities;

…

(c) … The ICC does not describe any whole process as “de-isolation”. There is an electronic status on a computer called “de-isolation in progress”, but that is as far as the ICC goes. The AWU’s submission was that this defined or captured all reinstatement activities, but the evidence did not reflect the submission. …

(Emphasis added.) (Footnotes omitted.)

81 That part of the WMS manual which explained the ICC recorded:

Isolation Control Certificate | The Isolation Control Certificate (ICC) must be used to document the isolation and approval of equipment or systems and will be used to track the status of all isolations. |

… | |

… The ICC performs the following functions: | |

• Lists the location of the isolation points and their normal status. | |

• It is a record of any fittings (such as analyzer points, sample points and plugs) that have been removed or moved from their normal state to ensure that they are reinstated. | |

• It is a record of all drain, vent, and bleed points for valve integrity tests. (Operation of these valves does not need to be recorded as an amendment on the ICC but would be checked when returning equipment to service.) | |

• Authorizes any temporary de-isolation for equipment testing (Sanction to Test). | |

• Authorizes and records each de-isolated point. | |

• As necessary, includes attachments of marked-up P&IDs, electrical diagrams, and isolation plans/procedures. |

(Emphasis added.)

82 The primary judge rejected the contention by the AWU of an “accepted, and well understood meaning” that extended the notion of de-isolation to equipment testing, air freeing or leak testing and found that the prevalent understanding about what de-isolation involved was governed by the WMS.

83 In his conclusions about this part of the case, the primary judge rejected the idea that the ICC had significance as any form of work instruction in its own right and he rejected the suggestion that de-isolation extended either generally to equipment testing, or to manipulation of particular valves in connection with that work:

89 Returning to the respondent’s reliance on the ICC, of the two presently contentious senses in which the term “de-isolation of equipment” might have been understood by the applicant as recipient of the notice of 3 February 2015, that referred in the WMS manual is, in my view, the more natural one. It refers to the de-isolation of equipment as such, and is, therefore, more closely aligned with the specific tasks which would, in the normal course, be carried out by operators, and which the applicant would understand to be the subject of the ban. By contrast, the ICC is concerned not with tasks or functions but with recording the positions of points at particular stages in the process of taking some equipment out of, and of returning it to, service. Insofar as it deals with the points that must be changed from one state to another, it records what has been done rather than, for example, instructing what should be done. Nowhere is this clearer than in the evidence of Mr Jackson. In short, of the two documents, the WMS manual is the more closely related to the work as such, and is the more directly concerned with marking out de-isolation as an activity of work.

90 For the above reasons, I would reject the proposition that the expression “de-isolation of equipment” in the respondent’s notice of 3 February 2015 would reasonably have been understood by the applicant as referring to every aspect of operators’ work that would be performed during the period that the ICC was headed “[De-isolation] in Progress”. To the contrary, in my view it would have been so understood as referring to the specific function of de-isolation as such. It would not have been so understood as encompassing equipment testing, air freeing or leak testing. Nor did it refer to the manipulation of valves associated with those activities, notwithstanding that such manipulations were mentioned on the ICC. It follows that the respondent’s ban on work of that kind was not protected industrial action within the meaning of the FW Act.

(Emphasis added.)

84 In my view, those conclusions reflected the evidence to which the primary judge referred. I will refer to that evidence in more detail shortly.

85 It is convenient, however, to make the observation at this point that, stripped of the attempt to colour the meaning of the WMS instructions by some subjective interpretation of them (which seems, if I might say so, to be foreign to the use to be made of instructions of this kind, having regard to safety implications) the AWU’s case could not ultimately depart from the terms of the WMS manual. Its argument about the role and significance of the ICC was one which was necessarily confined by the use of the ICC within the procedures directed by the WMS manual.

86 No error was shown in the understanding of the primary judge which was recorded by him at [89]. He had a particular advantage as the trier of the facts. Furthermore, as I shall return to mention, I have considerable reservations about the notion that an enterprise in Esso’s position can be told what its safety procedures signify as a matter of purely textual debate or subjective assertion.

87 First, however, I shall endeavour to trace, in a little more detail, some of the other evidentiary strands with which it was necessary for the primary judge to deal in his comprehensive discussion of this issue.

88 The course of the industrial dispute which was revealed in evidence before the primary judge, and referred to in his findings, was also consistent with his understanding of the process of de-isolation. It is apparent that the AWU modified its position about the extent of the bans it had imposed, in response to Esso’s success in having members of staff perform some of the necessary work.

89 Initially, after the advice given on 3 February 2015, which took effect on 12 February 2015, AWU members banned de-isolation work in the sense referred to in the WMS. The effect of that action, and Esso’s response, was referred to as follows by Mr James Kristeff, Maintenance Superintendent at Longford:

44. The de-isolation ban commenced on 12 February 2015 as notified, and has not ceased.

45. The ban had a paralysing effect on all work that governed by the WMS. Consequently, Esso was forced to decide whether it was able to continue to operate the Longford Plant safely.

46. On 25 February 2015, Esso decided to make the following alternative arrangements to cope with the de-isolation ban:

(a) instruct appropriately qualified managerial staff to perform de-isolations; and

(b) triage and prioritise certain work so that managerial staff could perform critical de-isolations.

47. Esso consulted with supervisors prior to making a decision as to whether to implement this proposal.

48. Following that consultation, on 26 February 2015, Esso implemented this arrangement. Managerial staff began to perform the de-isolation in lieu of employees. That is:

(a) operators performed recommissioning work, equipment testing, air freeing, and leak testing;

(b) supervisors then stepped in to perform the de-isolation; and

(c) the operator would then step in and complete the work by removing any temporary defeats and perform acceptance testing, and thereby move to close out the work permit.

49. This enabled Esso to move through the critical work activities. It significantly reduced the impact of the de-isolation ban.

90 The primary judge recorded (at [44]):

44 … in response to the respondent’s ban on the “de-isolation of equipment”, the applicant had instructed its supervisors to perform de-isolations. It seems that there were at least two, and possibly more, de-isolations performed by supervisors in the period which followed the respondent’s notice of 3 February 2015. Ross Dunbar, the Operations Superintendent – Gas Asset of the applicant (whose normal responsibilities lie in the area of the applicant’s offshore facilities but who was temporarily working at Longford in the co-ordination of de-isolation activities at this time) said in his affidavit that the first de-isolation by a supervisor was done on 19 February 2015. Robert Steed, an operations technician and a delegate of the respondent, said in his affidavit that de-isolations were done by supervisors on 26 February and 3 March 2015. It is sufficient to find that, by the latter date at the latest, it would have been apparent to the respondent and its members at Longford that the applicant had developed a modus operandi by which equipment de-isolations, banned by the respondent since 12 February 2015, could be done by supervisors.

91 Mr Kristeff said:

50. On 2 March 2015, operators began to advise their supervisors that they would not perform air freeing or leak testing required to be performed before de-isolations.

51. I am informed that on 4 March 2015 a meeting occurred between Esso managerial staff and AWU representatives to discuss this issue. At that meeting were Rob Mackie (Longford Plant Operations Superintendent), Ross Dunbar (Operations Superintendent – Gas Asset), Rob Steed (AWU delegate), and Kain Jackson (an AWU member who refused to perform air freeing/leak testing), amongst others. I am advised and believe that Rob Steed:

(a) advised that it was the AWU’s position that the de-isolation ban included air freeing/leak testing; and

(b) confirmed that all 81 members of the AWU were aligned to that position.

52. I am informed that there was a 30 minute break between the meeting to allow Esso and the AWU to reconsider their positions. When the meeting was recommenced, I am informed that the AWU representatives:

(a) confirmed their position; and

(b) advised that their members would refuse to perform air freeing/leak testing if requested to do so.

53. On the basis of this information provided to me, I decided to call Ben Davis, AWU Victorian Branch Secretary, that evening. Melinda Fairbanks, Human Resources, was present when I telephoned Mr Davis. In that conversation:

(a) I said that air freeing, purging and pressure testing (i.e. leak testing) are not classified as de-isolations;

(b) I invited Mr Davis to consult with his members and delegates at Esso about the position that has been taken; and

(c) Mr Davis advised that he would consult his delegates at Esso.

54. Mr Davis called me and Ms Fairbanks shortly afterwards and said that it was the AWU’s view that the ban on air freeing/leak testing was part of the de-isolation ban.

92 The primary judge recorded the following (at [45]-[46]):

45 Over the period 28 February to 2 March 2015, preparations began for the de-isolation of the Gas Plant 1 rich oil fractionator tower. The scoping of these works included operations supervisors reviewing the ICC and drawings, and walking the process lines in the field. On 3 March 2015, as part of these preparations, supervisors were involved in de-isolating the rich oil fractionator tower level bridle, which was required to allow the tower de-isolation to commence the following day.

46 At about 4:45 pm on 4 March 2015, Messrs Dunbar and Mackie met with Messrs Steed and Jackson. Mr Steed told Messrs Dunbar and Mackie that it was the respondent’s position that the de-isolation ban included air freeing and leak testing, and that all members of the respondent were aligned to that position. After a 30 minute break in this meeting, Mr Steed reiterated that this was the respondent’s position, and that its members would refuse to perform air freeing or leak testing if required to do so. James Kristeff, the Maintenance Superintendent at Longford telephoned Mr Davis, who confirmed what Mr Steed had said.

93 However, after proceedings in the FWC on 6 March 2015, the AWU’s position was further refined. The FWC recorded the respective parties’ positions on 6 March 2015 as follows:

…

In this present matter, the AWU considers that the bans in (e) referred to on air-testing, equipment testing, air-freeing and leak testing as included within that paragraph. Esso disagrees.

…

Various phrases were used by the AWU to describe their understanding, including “custom and practice” and “the ordinary usage in the workplace.” A number of phrases were used. The employer on the other hand relies on the definitions used in safety manuals produced by them in accordance with their extremely important obligations to provide a safe workplace. These obligations are in any sense critical. Their ability to function depends on implementation of proper safety procedures.

…

94 The FWC concluded that equipment testing, air freeing and leak testing was not notified in the notice on 3 February 2015, and the s 418 order made on that day prohibited bans on that work.

95 Then the AWU’s position changed. The AWU then commenced to contend that although such work was not banned as such, manipulation of any valve listed on an ICC for the purpose of that work fell within the earlier notification.

96 The primary judge traced the development of this new position. On 7 March 2015, particular work (air freeing and leak testing) was scheduled and three employees were assigned to perform it. The primary judge said (at [55]-[64]):

55 One of those employees was Gary Jones, an operator and a member of the respondent. On the morning of 7 March 2015, the members of his shift held a meeting. They were addressed by their delegate, Karl Tschugguel. He informed them of the Commission’s order, and what it required. He said that they were not to ban air freeing and leak testing work. There followed a discussion about what could be done without breaching the order. The operators decided that, if points were listed on the ICC, they were de-isolation work and were covered by the ban. They decided that, under the ban, it was open to them to refuse to manipulate the points or valves.

56 At approximately 9:00 am, Mr Lloyd met with Mr Jones. They discussed the leak testing to be performed on the propane header, the pressure rating on the vessels, and the scope of the work generally. Mr Lloyd came away from those discussions with the understanding that Mr Jones was going to perform the leak testing.

57 Mr Jones then spoke to Mr Tschugguel, and informed him that Mr Lloyd had requested that he perform leak testing work on the propane header. He sought clarification as to what he could and could not do as part of the protected industrial action. He told Mr Tschugguel that a bleeder valve on the propane header would have to be manipulated before he could conduct pressure testing. Mr Tschugguel then asked Mr Jones to access a computer to check the electronic ICC. Having done so, Mr Jones said that the ICC was “in place”, and that it also listed the bleeder valve as a tagged valve. The valve was also tagged “in the field”. On the basis of this information, Mr Tschugguel advised Mr Jones that, if a supervisor manipulated the bleeder valve and recorded “de-isolation in progress” on the ICC, both on the computer and in the field, he should comply with the Commission’s order and perform the pressure test.