FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC [2015] FCAFC 179

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

PRODUCT MANAGEMENT GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 131 987 034) Appellant | |

AND: | Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 December 2015 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for leave to appeal be granted.

2. The appeal is dismissed.

3. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of and incidental to its application for leave to appeal and its appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 30 of 2015 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | PRODUCT MANAGEMENT GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 131 987 034) Appellant |

AND: | BLUE GENTIAN LLC Respondent |

JUDGES: | KENNY, nicholas AND BEACH JJ |

DATE: | 14 December 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KENNY AND BEACH JJ:

1 Product Management Group Pty Ltd (PMG) has sought leave to appeal from the primary judge’s orders made on 19 December 2014 which gave effect to his reasons delivered on 8 December 2014. The primary judge made declarations that PMG’s Pocket Hose product (the Pocket Hose) infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of Australian Innovation Patent 2012101797 (the First Patent) and claims 1, 2 and 5 of Australian Innovation Patent 2013100354 (the Length Patent) held by Blue Gentian LLC (Blue Gentian). His Honour also dismissed PMG’s cross-claim for invalidity. Invalidity had been asserted based upon, inter alia, a lack of an innovative step by reason of the disclosures in US Patent 6,523,539.

2 Before us PMG has principally submitted that the primary judge erred by:

(a) misconstruing the claims, and accordingly erroneously finding that the claims were infringed; and

(b) failing to apply the correct test for assessing innovative step.

3 In our opinion, leave to appeal should be granted (as we said at the hearing of the appeal) but the appeal dismissed.

PROCEEDINGS BELOW

4 The proceeding at first instance concerned a claim by Blue Gentian and Brand Developers Aust Pty Ltd (allegedly the exclusive licensee) that PMG had infringed or authorised the infringement of the First Patent and the Length Patent, both titled “Expandable and Contractible Hose” (the Patents). The position of Brand Developers Aust Pty Ltd can be put to one side given the nature of the issues raised before us.

5 Blue Gentian contended that PMG had directly infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent. PMG owns and operates a business supplying in Australia a garden hose marketed under and by reference to the name “Pocket Hose” (the Pocket Hose). Blue Gentian alleged that PMG directly infringed the Patents because it imported, offered for sale or otherwise disposed of, sold or otherwise disposed of, and kept for the purpose of selling or otherwise disposing of, the Pocket Hose in Australia without the relevant licence or authority to do so, or authorised others to do so. Further, Blue Gentian alleged that PMG indirectly infringed the Patents pursuant to s 117(2)(c) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act).

6 PMG, by way of cross-claim, alleged that the Patents were invalid and liable to be revoked. In particular it alleged that:

(a) Claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent were anticipated by US Patent 6,523,539, titled “Self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen mask” (the McDonald Patent). At first instance the primary judge rejected the lack of novelty argument. PMG does not challenge that finding.

(b) Claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent did not involve an innovative step in light of the McDonald Patent. At first instance the primary judge rejected the lack of innovative step argument. That finding has been challenged on appeal (appeal grounds 1, 4 and 5(a)).

(c) Particular claims of each of the Patents were not fairly based on the matter described in the respective specifications of those Patents. Further, particular claims of each of the Patents were not clear and succinct. Further, particular claims of the First Patent did not describe the invention fully. At first instance the primary judge rejected all such arguments. PMG no longer challenges such findings (appeal grounds 2 and 3 have not been persisted with).

7 The issues of infringement and validity were heard and determined separately and before any questions of pecuniary relief.

8 Blue Gentian relied on the evidence of Mr William Hunter, who was a qualified mechanical engineer who had worked in the area of product development and engineering design in relation to a wide range of products over the last 28 years, both within industry and as a consultant. Mr Hunter made three affidavits, namely: (a) the first affidavit dated 25 July 2013 addressing whether there had been an infringement of the First Patent; (b) the second affidavit dated 3 September 2013 addressing whether there had been an infringement of the Length Patent; and (c) the third affidavit dated 19 December 2013 responding to PMG’s evidence in chief on invalidity, and evidence in answer on infringement.

9 PMG relied on the evidence of Professor Steven Armfield, who was a Professor of Computational Fluid Dynamics and Head of the School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering at the University of Sydney. Professor Armfield made two affidavits, namely: (a) the first affidavit dated 15 November 2013 responding to Mr Hunter’s first and second affidavits and addressing what was disclosed in the McDonald Patent; and (b) the second affidavit dated 23 January 2014 responding to Mr Hunter’s third affidavit.

10 Further, a joint expert report was also prepared and tendered of Professor Armfield, Mr Hunter and Mr Michael Elmore, consultant, dated 28 January 2014 (the Joint Report). As Mr Elmore was not called, his contribution to the Joint Report was not relied upon by the parties and put to one side.

the patents

11 Before proceeding further, it is appropriate to discuss the Patents; we have drawn, in part, upon the summary given by the trial judge in his reasons ([9] to [24]).

12 The First Patent and the Length Patent essentially have the same text in the body of their specifications. Further, the claims differ in substance in only a few respects. The Patents claim a garden hose that expands substantially in length (the First Patent) or two to six times (the Length Patent) when the water faucet it is coupled to is turned on. The hose returns to its original length after use.

13 The elongation is achieved by reason of the garden hose having an elastic inner tube and an inelastic outer tube which are only attached at their ends, such that when the faucet is turned on water pressure causes the inner tube to engorge, expanding in length and diameter to the point where it is constrained by the length and diameter of the inelastic outer tube. A “water flow restrictor” (or a “fluid flow restrictor” referred to in the claims of the First Patent) in, or attached to, the far end of the hose causes an additional increase in water pressure in the hose (compared to a hose with no such water flow restrictor).

14 When the faucet is turned off, the water drains from the garden hose and the resulting decrease in water pressure allows the inner tube to contract. The outer tube reduces in length by catching on the rubbery surface of the inner tube and gathering tightly in folds along the length of the hose.

15 The perceived advantages of garden hoses made in accordance with the Patents are that they have the ability to expand their length when in use without bursting, they are lightweight and easy and convenient to pack, transport and store, and do not kink in use.

(a) The body of each specification

16 The field of the invention of the First Patent, which similarly applies to the Length Patent, is described in the First Patent as follows:

The present invention relates to a hose for carrying fluid materials. In particular, it relates to a hose that automatically contracts to a contracted state when there is no pressurized fluid within the hose and automatically expands to an extended state when a pressurized fluid is introduced into the hose. In the contracted state the hose is relatively easy to store and easy to handle because of its relative short length and its relative light weight, and in the extended state the hose can be located to wherever the fluid is required. The hose is comprised of an elastic inner tube and a separate and distinct non-elastic outer tube positioned around the circumference of the inner tube and attached and connected to the inner tube only at both ends and is separated, unattached, unbonded and unconnected from the inner tube along the entire length of the hose between the first end and the second end.

17 The background section ([0002] to [0004]) describes problems encountered with garden hoses. The identified problems relate to storage, such as the need for a reel or a container, and to tangling, kinking and the weight of the hose. The Patents state that it would be of great benefit to have a hose that is light in weight, expandable and contractible in length and kink-resistant.

18 Following a discussion listing numerous items of prior art hoses (the McDonald Patent is listed only in the Length Patent at [0026]), a summary of the invention starts at [0030] of the First Patent and [0031] of the Length Patent. Following the summary of the invention, the Patents set out a detailed description and several figures.

19 The invention is described as a hose comprising an inner tube inside an outer tube. The outer tube is secured to the inner tube only at the ends. The hose expands when connected to a pressurised water supply such as a water faucet. The hose can expand longitudinally, and in the case of the Length Patent, by up to six times in length. On release of the pressurised water from the inner tube, the inner tube will contract. The inner tube could be made of rubber while the outer tube could be made of an inelastic relatively soft fabric like woven nylon, which gathers in folds about the inner tube when the inner tube is contracted.

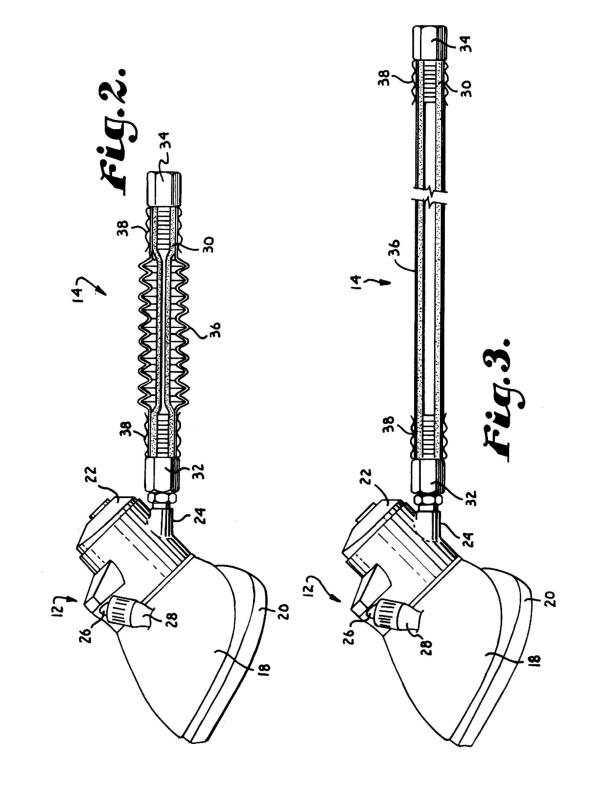

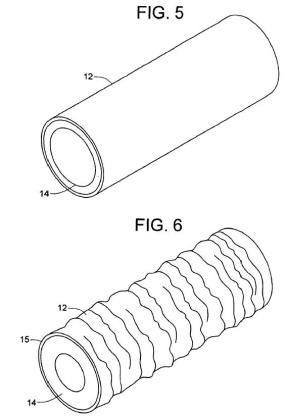

20 Figures 5 and 6 of the Patents (as set out below) show the invention in its unexpanded and in its expanded states. In relation to the notations, number 12 refers to the outer tube, number 14 refers to the inner tube and number 15 refers to the space between the inner and outer tubes.

21 In the unexpanded state, when there is no fluid pressure within the hose, the inner tube is in a relaxed condition. There are no forces being applied to expand or stretch it. In this state the outer tube is folded, compressed and tightly gathered around the outer circumference of the inner tube. When the hose is connected to a water supply and the supply is turned on, fluid pressure is applied, expanding the inner tube. The inner tube will expand laterally (also referred to as radially) and will also expand longitudinally (also referred to as axially), i.e. along the length of the hose. As the inner tube expands the wall thickness of the inner tube material is reduced. If the expansion is not constrained, the wall would become too thin and would likely rupture. The lateral expansion is therefore constrained by the diameter of the outer tube. The longitudinal expansion is similarly constrained by the length of the outer tube. As the water inflates the inner tube, the hose expands longitudinally and the folds of the outer tube unfurl until it is smooth (see figures 5 and 6 of the Patents, reproduced above). In this state the hose is ready to be used. The hose may also have a fluid flow restrictor, such as a nozzle or sprayer:

(a) attached to the second coupler, e.g. a trigger nozzle; and/or

(b) within the second coupler (which can be a narrower bore than the bore of the hose).

22 When water is allowed to flow within the hose the pressure inside will drop to some extent but there will be enough pressure remaining in the hose to keep it expanded in use.

23 The Patents describe the various benefits of the invention, including:

(a) savings in weight, since it contracts without the need for metal components, and since a conventional 50 foot garden hose is said to weigh 12 lbs (5.4 kg) whereas the Patents describe a hose which “may only weigh less than 2 pounds” (0.9 kg);

(b) the hose automatically contracts when there is no pressure in the inner tube;

(c) the empty hose of the invention can be readily stored without kinking or becoming entangled as most conventional hoses do; and

(d) savings in time, because the hose contracts automatically from its expanded condition thus avoiding the need to carry or drag the hose, or the need for a hose reel, for storage.

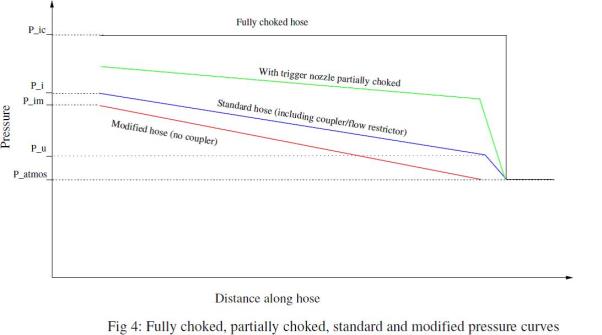

(b) The claims

24 The claims of the First Patent are as follows:

1. A garden hose including:

a flexible elongated outer tube constructed from a fabric material having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow;

a flexible elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow, said inner tube being formed of an elastic material;

a first coupler secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes for coupling to a pressurized water faucet;

a second coupler secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes for discharging water;

the inner and outer tubes being unsecured to each other between first and second ends thereof; and

said second coupler also coupling said hose to a fluid flow restrictor or including a fluid flow restrictor so that the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said inner tube, said increase in water pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby substantially increasing a length of said hose to an expanded condition and said hose contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler.

2. The water hose of claim I, wherein said inner tube and said outer tube are made from materials which will not kink when said inner and said outer tubes are in their contracted condition.

3. The water hose of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein said first coupler is a female coupler and said second coupler is a male coupler.

4. The water hose of any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the outer tube is unattached, unconnected, unbonded, and unsecured to the elastic inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube between the first end and the second end so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube when the hose expands and contracts.

5. The water hose of any one of claims 1 to 4, wherein the outer tube catches on a rubbery outer surface of the elastic inner tube and automatically becomes folded, compressed and tightly gathered around the outside circumference of the entire length of the contracted inner tube.

25 The claims of the Length Patent are as follows:

1. A garden hose including:

a flexible fabric material elongated outer tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow;

a flexible elastic material elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow;

a first coupler for connection to a water faucet, secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes, and a second coupler for discharging water, secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes, said outer and inner tubes being unattached, unconnected. unbonded, and unsecured to each other along their entire lengths between the first end and the second end so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube when the hose expands or contracts; and

a water flow restrictor connected to or being in the second coupler for increasing water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said hose, said increase in fluid pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby increasing a length of said hose by 2 to 6 times to an expanded condition and said hose being contracted to a decreased length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler.

2. The garden hose of claim 1, wherein said garden hose is at least 10 feet long.

3. The garden hose of claim 1 wherein the hose increases in length by 4 to 6 times.

4. The garden hose of any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the first coupler is a female coupling for connection to a water faucet, and the second coupler is a male coupling for discharging water.

5. The garden hose of claim 1 wherein, when the extended elastic inner tube begins to contract from its expanded length, the unattached, unbonded, unconnected and unsecured fabric material outer tube catches on a rubbery outer surface of the inner tube material, causing the outer tube to automatically become randomly folded, compressed and tightly gathered around an outside circumference of the entire length of the contracted inner tube.

26 His Honour divided up the relevant integers for claim 1 of each Patent in the tables set out below. In part, this was a reflection of how the case was argued before him by the parties. But it must be said that to so divide up these integers in this way may have had the tendency to produce various difficulties with construction that we will later address in more detail. Instead of the last paragraph of claim 1 of the First Patent being treated as a whole, it was divided into the tabulated integers numbered 1.7 to 1.9. Instead of the penultimate paragraph of claim 1 of the Length Patent being treated as a whole, it was divided into the tabulated integers numbered 1.4 to 1.6. Instead of the last paragraph of claim 1 of the Length Patent being treated as a whole, it was divided into the tabulated integers numbered 1.7 to 1.9. There is nothing inherently wrong with such divisions, provided that such divisions do not distract from reading each particular claim as a whole. Moreover, reading each claim as a whole, as the hypothetical skilled addressee is expected to do, is more likely to give such an addressee an appreciation of what is really meant by the words used rather than some literal and grammatically parsed construction devoid of practicality and context.

27 The integers of claim 1 of the First Patent were described as follows:

1.1 | A garden hose including: |

1.2 | a flexible elongated outer tube constructed from a fabric material having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow; |

1.3 | a flexible elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow, said inner tube being formed of an elastic material; |

1.4 | a first coupler secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes for coupling to a pressurized water faucet; |

1.5 | a second coupler secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes for discharging water; |

1.6 | the inner and outer tubes being unsecured to each other between first and second ends thereof; and |

1.7 | said second coupler also coupling said hose to a fluid flow restrictor or including a fluid flow restrictor so that the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said inner tube, |

1.8 | said increase in water pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby substantially increasing a length of said hose to an expanded condition and |

1.9 | said hose contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler. |

28 The integers of the Length Patent were described as follows:

1.1 | A garden hose including: |

1.2 | a flexible fabric material elongated outer tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said outer tube being substantially hollow; |

1.3 | a flexible elastic material elongated inner tube having a first end and a second end, an interior of said inner tube being substantially hollow; |

1.4 | a first coupler for connection to a water faucet, secured to said first end of said inner and said outer tubes, and |

1.5 | a second coupler for discharging water, secured to said second end of said inner and said outer tubes, |

1.6 | said outer and inner tubes being unattached, unconnected, unbonded, and unsecured to each other along their entire lengths between the first end and the second end so that the outer tube is able to move freely with respect to the inner tube along the entire length of the inner tube when the hose expands or contracts; and |

1.7 | a water flow restrictor connected to or being in the second coupler for increasing the water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said hose, |

1.8 | said increase in fluid pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby increasing a length of said hose by 2 to 6 times to an expanded condition and |

1.9 | said hose being contracted to a decreased length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler. |

CONSTRUCTION

29 There is no disagreement as to the nature of the invention claimed. It is a garden hose.

30 Similarly, the identification of the relevant skilled addressee is not in dispute.

31 The field of the invention relates to:

… a hose that automatically contracts to a contracted state when there is no pressurized fluid within the hose and automatically expands to an extended state when a pressurized fluid is introduced into the hose.

32 The skilled addressee is a person with a working knowledge of the materials used for, and the design and manufacture of, hoses. He or she would also have an understanding of fluid mechanics. The general physical principles applying to garden hoses similarly apply to all hoses.

33 The primary judge regarded both Mr Hunter and Professor Armfield as relevant skilled addressees, and that identification is not in dispute.

(a) Principles of construction

34 The relevant principles of construction are not in doubt.

35 A claim is to be construed from the perspective of a person skilled in the relevant art as to how such a person, who is neither particularly imaginative nor particularly inventive (or innovative), would have understood the patentee to be using the words of the claim in the context in which they appear. A claim is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge before the priority date.

36 In construing the claims, a generous measure of common sense should be used (Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (2013) 101 IPR 11 at [108] per Middleton J and Streetworx Pty Ltd v Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd (2014) 110 IPR 82 at [58] to [69] per Beach J). Further, ordinary words should be given their ordinary meaning unless a person skilled in the art would give them a technical meaning or the specification ascribes a special meaning (Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 at [39] per Greenwood and Nicholas JJ).

37 The body of the specification may be used in the following fashion in construing a claim:

The claim should be construed in the context of the specification as a whole even if there is no apparent ambiguity in the claim (Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (2012) 290 ALR 47 at [222] per Middleton J and more generally Welch Perrin and Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 616); even the ordinary meaning of words may vary depending on the context, which the specification may provide;

Nevertheless, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of the monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to these words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification (Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86 at [67]; Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44]); and

More particularly, if a claim is clear and unambiguous, to say that it is to be read in the context of the specification as a whole does not justify it being varied or made obscure by statements found in other parts of the specification.

38 Now the specification may stipulate the problem in the art before the priority date and the objects of the invention that are designed to address or ameliorate this. Nevertheless, what is being construed are the claims. The specified objects may be useful in construing a claim in context. Nevertheless, the specified objects are not controlling in terms of construing a claim.

39 A claim should be given a “purposive” construction. Words should be read in their proper context. Further, a too technical or narrow construction should be avoided. A “purposive rather than a purely literal construction” is to be given (Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd at [41] per Greenwood and Nicholas JJ). Further, the integers of a claim should not be considered individually and in isolation. Further, a construction according to which the invention will work is to be preferred to one in which it may not (Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly and Co (2005) 68 IPR 1 at [250]).

40 But to give a claim a “purposive” construction “does not involve extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims” (Sachtler GmbH and Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd (2005) 221 ALR 373 at [42] per Bennett J). To apply a “purposive” construction does not justify extending the patentee’s monopoly to the “ideas” disclosed in the specification (GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare (UK) Ltd (2013) 305 ALR 363 at [60]).

41 Finally on this aspect, it is useful to set out Lord Hoffmann’s observation in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] RPC 9 at [34] where he said:

“Purposive construction” does not mean that one is extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. And for this purpose, the language he has chosen is usually of critical importance. The conventions of word meaning and syntax enable us to express our meanings with great accuracy and subtlety and the skilled man will ordinarily assume that the patentee has chosen his language accordingly. As a number of judges have pointed out, the specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s own choosing. Furthermore, the words will usually have been chosen upon skilled advice. The specification is not a document inter rusticos for which broad allowances must be made. On the other hand, it must be recognised that the patentee is trying to describe something which, at any rate in his opinion, is new; which has not existed before and of which there may be no generally accepted definition. There will be occasions upon which it will be obvious to the skilled man that the patentee must in some respect have departed from conventional use of language or included in his description of the invention some element which he did not mean to be essential. But one would not expect that to happen very often.

42 His Lordship also said at [35] that:

I do not think that it is sensible to have presumptions about what people must be taken to have meant, but a conclusion that they have departed from conventional usage obviously needs some rational basis.

(b) Integers of claims — primary judge’s construction

43 His Honour made findings on construction (reasons at [37] to [81]) relevant to, inter alia, the following integers:

(a) a garden hose (integer 1.1 in the Patents);

(b) a water/fluid flow restrictor causing an increase in pressure between the couplers (integer 1.7 of the Patents);

(c) said increase in water/fluid pressure (integer 1.8 of the Patents); and

(d) substantially increasing a length of said hose/increasing a length of said hose by two to six times (integer 1.8 of the Patents).

44 His Honour accepted that these phrases and passages had to be considered in the context in which they appeared. As his Honour said, the Patents were for a garden hose. A skilled addressee would know how a garden hose worked and how it was used and this knowledge had to be applied in the construction of the claims. The skilled addressee would know, as the first paragraph of the Patents indicated, that expansion is to occur when a pressurised fluid is introduced into the hose — for example, when a water tap is turned on and water enters the hose.

45 Because of their direct or indirect relevance to the appeal grounds, we propose to set out in detail his Honour’s findings on construction on integers 1.1, 1.7 and 1.8 of the Patents, although it is only integer 1.8 that has been the subject of a specific challenge before us on the question of construction. But his Honour’s construction of integer 1.8 is to be read with his construction of integer 1.7.

Garden hose (integer 1.1)

46 His Honour considered ([39] and [40]) that whatever else was referred to in the specification, the claims all described the invention as either a “garden hose” (claims 1 to 5 of the Length Patent, and claim 1 of the First Patent) or a “water hose” (claims 2 to 5 of the First Patent). It was clear that “water hose” was used synonymously with “garden hose” as it is described as a “water hose of claim 1” of the First Patent.

47 His Honour held that the proper construction of “garden hose” was a hose capable of being used as a garden hose and performing the functions one would ordinarily expect a garden hose to perform — for example, being attached to a water source and being suitable for watering a garden. That construction was not in doubt before us.

Water/fluid flow restrictor causing an increase in pressure between the couplers (integer 1.7)

48 His Honour referred to the fact that integer 1.7 of the Patents required a fluid flow restrictor (the First Patent) or a water flow restrictor (the Length Patent) (reasons at [46] to [64]):

which “creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said inner tube” (the First Patent); or

“for increasing the water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler within said hose” (the Length Patent).

49 The restrictor in either case could be connected to the second coupler or incorporated within.

50 His Honour held that the word “creates” means “causes” or “generates”. His Honour referred to the fact that there was some debate about this. His Honour stated that the debate was raised late in the proceedings by Professor Armfield as to the term “creates”, which Professor Armfield preferred to interpret as “maintains”. Professor Armfield made reference to the water pressure being created in Sydney by the Warragamba Dam which was up in the mountains, and not created by the faucet. Therefore, he considered that there was just a modifying or maintaining of the water pressure in the hose. His Honour said that this was probably technically correct. But his Honour said that that is not what was meant by the claim in the First Patent when it used the word “creates”. His Honour said that, in simple terms, when there was, for instance, a complete flow restrictor, the water pressure in the hose was caused or generated by, say, the use of a nozzle.

51 His Honour addressed the submissions of the parties before him in this context.

52 PMG had submitted that a change in the geometry of the flow path introduced by the second coupling could also constitute a fluid flow restrictor with respect to the First Patent; the same principles applied in respect of the phrase “water flow restrictor” in the Length Patent claims. It also submitted that the integer was not capable of a sensible construction. That is because the principles of fluid mechanics dictated that in a hose such as that described in the Patents, water pressure would either be reduced between the entry and exit points if the fluid exited at atmospheric pressure, or be constant if there was no fluid flow. Further, PMG submitted that the Patents did not explain how water pressure could be increased between the first and the second couplers. It submitted that the skilled addressee would understand that it was not possible to increase the pressure between these points.

53 Blue Gentian submitted that this integer meant that a fluid flow restrictor must be present at the outlet end of the hose which created an increase in the water pressure between the first and second couplers, compared with the pressure that would exist if there was no such fluid flow restrictor. It also submitted that “a ‘fluid flow restrictor’ or ‘water flow restrictor’ could only comprise a ‘change in the geometry of the flow path introduced by the second coupling’ if it also constitute[d] a reduction in the tube diameter that a person skilled in the art would consider provide[d] a practical (i.e., not insignificant) restriction to fluid flow”.

54 Blue Gentian submitted that the skilled addressee would consider whether the narrowing of the tube diameter caused by the flow restrictor was likely to have the practical effect of restricting the flow of the fluid in question and increasing the water pressure, and whether he or she would naturally describe it as a water or fluid flow restrictor.

55 His Honour considered that there were two elements to the construction of the integer: the flow restrictor and the effect that it had on the water pressure within the hose.

56 His Honour said that it should be self-evident that the component coupled to the second downstream coupler, or the coupler itself, must restrict the flow of water. He said that the specification was not explicit about what the flow restrictor must be and describes in [0055] of the Patents that “[a]nything that restricts the flow of fluid within the hose can be employed …”. Nozzles with various amounts of restriction and sprayers are offered as examples. He said that the specification specifically contemplated that the flow restrictor may be an L-shaped nozzle with a pivoting on-off handle which operates an internal valve which permits, limits or stops the flow of water. His Honour said that this indicated that the specification contemplates a flow restrictor that permits various levels of flow restriction.

57 His Honour then said that it follows that a water or fluid flow restrictor is any component coupled to or integrated within the second downstream coupler, or the downstream coupler itself, if it restricts the flow of fluid. His Honour said that this should not be controversial.

58 However, his Honour said that construction of the second element — that is, the function of the water or fluid flow restrictor — was more complex.

59 His Honour said that, in general terms, the dispute was whether the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in pressure “from” the first coupler “to” the second coupler (PMG’s construction) or whether the increase relates to an increase in pressure as measured within the hose that is located between the first and second couplers as compared to a hose without a flow restrictor (Blue Gentian’s construction).

60 His Honour then referred to figure 4 in Appendix A of the Joint Report (reproduced below), which the experts agreed was an accurate representation of the change in water pressure along the hose in various states, namely, the hose completely choked off, with a partially choked nozzle, with a standard hose (with the first coupler attaching the hose to the tap and the second coupler/flow restrictor), and with a modified hose (without a second coupler/flow restrictor). It is appropriate at this point to interpolate our own description (modified from Annexure A) of some of the variables used. The variables on the vertical (y) axis are the following. P_atmos is atmospheric pressure and is the pressure within the hose before the introduction of the water (black dotted line). When pressurised water from the faucet is introduced into the hose the hose fills with water and becomes elongated. The water entering the hose inlet is at pressure P_i, which is above P_atmos. P_i is determined by the pressure in the trunk main, which may be considered for present purposes to be a constant. If the hose is a standard hose with a second coupler/flow restrictor, the pressure reduces from P_i as the fluid passes along the hose (blue line). The pressure change occurs in the direction of flow partly as a result of friction between the fluid and the hose wall. As the fluid passes through the second coupler/flow restrictor, the increased friction partly leads to a more rapid change in pressure to P_u. If you modify the hose and remove the second coupler/flow restrictor, the fluid enters the hose at P_im (red line). The flow velocity increases, leading to greater frictional effects. P_im is accordingly less than P_i. Take another case where you have the hose with the second coupler/flow restrictor with a nozzle (adjustable) and you close it off completely. The pressure is shown on figure 4 as P_ic. And as there is no flow, there is no pressure drop; there are no frictional effects (see black line). Alternatively, if the nozzle operates as a partial choke, there will be some pressure change (green line). Before proceeding further we should make one other point here concerning frictional effects. For the invention the subject of the Patents, you are dealing with an inner tube and an outer tube which are flexible. When you have flow through the inner tube, you have frictional effects, which cause an expansion of the hose (both lateral and longitudinal). In other words, friction has two causal dimensions, being its effect on fluid pressure and its effect producing expansion.

61 His Honour said that it was correct that when water is introduced into the hose there is a reduction in pressure from the upstream end of the hose to the point at which the water exits the hose. Therefore, his Honour said that if he was to accept PMG’s construction, the integer would be a “scientific nonsense”. His Honour said that it is clear that there is no increase of pressure from the first coupler “to” the second coupler — in the three conditions of the hose where there is water flowing out of the hose (that is, the hose with a partially choked nozzle, with a second coupler that restricts flow, and with no second coupler) the water pressure decreases along the length of the hose.

62 His Honour recognised that the two experts disagreed as to the interpretation to give to this integer. Professor Armfield (who supported PMG’s construction) took a “literal” approach to the interpretative task accepting that his approach led to a “scientific impossibility”.

63 His Honour noted however that during cross examination, Professor Armfield accepted that it was a “reasonable” use of language to describe the “increase” in pressure as shown in the difference between the red and blue lines in figure 4 reproduced above as being the relevant increase created by the fluid flow restrictor.

64 In his Honour’s view, Mr Hunter, who supported Blue Gentian’s construction, took a common sense approach to interpreting claim 1 in the context of it being a garden hose. Mr Hunter’s interpretation of the integer required that the water flow restrictor caused an increase in water pressure between the two couplers, and that it was this overall water pressure increase from the hose’s original condition (prior to attachment to a faucet) to its pressurised condition that had to “substantially increase” the length of the hose. His Honour did not consider (as was submitted by PMG) that Mr Hunter changed his position as the proceeding developed.

65 His Honour concluded that the words in dispute, properly understood in the context of a garden hose, could be readily understood if read in this common sense way. His Honour said that it could be seen from the above figure that while the pressure decreases along the length of the hose, it is still greater at the position of the second coupler if there was a flow restrictor than if there was not.

66 His Honour said that, furthermore, the distance between the couplers was the entirety of the hose. His Honour said that another way of looking at “between said first coupler and said second coupler” would be to consider it as a way of describing the hose as a singular item. When looking at the above figure, generally, the water pressure within the hose with a flow restrictor is always greater than the water pressure without a flow restrictor. His Honour concluded that this construction accorded with the words of the integer.

67 In summary, his Honour concluded that presented with two constructions of an integer, where one was a scientific nonsense and the other a plausible construction, then provided the principles of construction were followed, the plausible construction should be favoured. His Honour said that he did not consider that by adopting Blue Gentian’s construction he was extending the patentee’s monopoly, or reading into the claims words by reference to the purpose of the monopoly. His Honour said that he was interpreting the claims in a manner consistent with the wording, and in a manner which gave sense to the operation and function of a garden hose. His Honour said that a skilled addressee, having common general knowledge of a garden hose, its design and use, would readily read claim 1 in the manner interpreted by Mr Hunter.

68 His Honour’s construction of integer 1.7 is not generally in issue. But it is important to be clear on his Honour’s findings concerning integer 1.7 as they bear upon the construction of integer 1.8 and PMG’s challenge to his Honour’s construction of integer 1.8. Before proceeding further, we would also note that PMG has not challenged his Honour’s general approach to construction as set out in the preceding paragraph, albeit in the context of considering integer 1.7. His Honour in dealing with integer 1.8 continued, consistently, with that same general approach. At all times he sought to identify what the skilled addressee would look for, namely, a plausible construction consistent with the context, and which avoided a construction that was a scientific nonsense or scientifically implausible.

Said increase in water / fluid pressure (integer 1.8)

69 His Honour considered integer 1.8 (reasons at [65] to [78]) and the phrase “said increase in water / fluid pressure”. As his Honour described it, integer 1.8 of the First Patent describes:

said increase in water pressure expanding said elongated inner tube longitudinally along a length of said inner tube and laterally across a width of said inner tube thereby substantially increasing a length of said hose to an expanded condition

(emphasis added)

70 Integer 1.8 of the Length Patent reads in similar terms, but it speaks of “fluid” pressure, rather than water pressure.

71 His Honour said that the construction of “said increase in water pressure” turned on whether the word “said” was to be as construed as referring to only the increase in water pressure between the first coupler and the second coupler within the inner tube created by the fluid flow restrictor alone (PMG’s construction) or whether it also included the increase in pressure created by the introduction of pressurised water from the faucet — that is, the increase in pressure was not limited to the increase caused by the fluid flow restrictor (Blue Gentian’s construction).

72 His Honour said that PMG’s construction referred back to the previous use of the words “increase in water pressure” as defined and limited by the language of the immediately preceding integer 1.7, so that the relevant “increase in water pressure” was limited to that caused by the relevant fluid flow restrictor only.

73 Contrastingly, for Blue Gentian’s construction, the word “said” referred back to the words “increase in water pressure” more generally, including the increase that resulted from the first coupler being connected to the “pressurized water faucet” which had been opened.

74 His Honour then discussed the evidence of the experts. Professor Armfield’s evidence in chief was that where water flows through the hose, the expansion of the hose is caused principally by frictional effects within the inner tube (that is, the friction between the fluid and the wall of the hose) with the flow restrictor only making a minor contribution to the expansion of the hose.

75 Mr Hunter’s evidence was generally that it was upon the application of pressurised water from a faucet that frictional effects or the flow restrictor, or a combination of both, caused the lateral and longitudinal expansion of the hose.

76 His Honour said that he found Mr Hunter’s evidence persuasive, whose evidence was confirmed, so his Honour considered, by some of the evidence of Professor Armfield.

77 His Honour said that in cross-examination, Professor Armfield accepted that the skilled addressee would consider the effect on the hose of the overall increase in water pressure, and not just that which was contributed to by a fluid flow restrictor. Professor Armfield accepted that the words “expanded condition” in the claim referred to the hose once it had been expanded by having pressurised water introduced into it. Professor Armfield accepted that, for a dynamic system (that is, with water flowing) the expansion would be caused by both the fluid flow restrictor and the frictional effects caused by the flow of water through the hose itself, and that the skilled addressee would be aware of this. Professor Armfield also accepted that integer 1.9 of the claim, “said hose contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler” referred to the overall decrease in pressure as the pressure inside the hose returned to atmospheric pressure. This was the “corollary” of the “substantial increase” that resulted in the “expanded condition” of the hose from its initial state where the internal pressure started at atmospheric pressure.

78 His Honour said that Professor Armfield had said in re-examination that the decrease in water pressure mentioned in integer 1.9 was referring to the same water pressure as the phrase in integer 1.7 “the fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure between said first coupler and said second coupler” — that is, the entire water pressure increase or decrease between the couplers, not just that caused by the fluid flow restrictor.

79 His Honour said that it was to be noted that the percentage contribution of the fluid flow restrictor to the overall increase in water pressure could vary, according to the type of fluid flow restrictor and degree of restriction it provided. His Honour said that Blue Gentian’s construction permitted this whereas PMG’s more literal construction required the measurement of the contribution to expansion made by a fluid flow restrictor, and the issue further arose as to what usage or flow conditions were present. His Honour said that this added complexity pointed against PMG’s construction. On PMG’s construction, how would anyone know or establish for a particular hose what was within or without claim 1? At the least, to so establish would be a difficult forensic exercise. We agree with his Honour’s point to some extent but such an argument cannot dictate what construction to use.

80 His Honour then said that he thought the argument concerning the construction of integer 1.7 was slightly distracting. The claims were for the assembly of a garden hose. There must be a fluid flow restrictor as required by the claim — being in the second coupler, and/or connected to the second coupler and it must be causative of an increase in water pressure in the hose. His Honour said that the skilled addressee would recognise that, when there are substantial flows of water through the hose, the frictional effects within the inner tube of the hose were an additional significant cause of the increase in water pressure within the hose.

81 Accordingly, his Honour construed “said increase in water / fluid pressure” to be the result of frictional effects and the presence of a flow restrictor. In other words, the phrase was not limited to the increase caused by the fluid flow restrictor.

82 The other aspect of integer 1.8 dealt with the requirement of substantially increasing a length of said hose/increasing a length of said hose by two to six times, which aspect we will put to one side for the moment.

appeal Ground 6: Construction and infringement

(a) PMG’s contentions

83 PMG contended that his Honour should have found that integer 1.8 of claim 1 of the Patents required the “said increase in water pressure” to be brought about by the flow restrictor (and not by other means) and to “substantially” increase the length of the hose (in the case of the First Patent) or to increase the length of the hose “by 2 to 6 times” (in the case of the Length Patent). It is said that the specification of each Patent provided context for the meaning of “substantial” in the claims including explaining that the hose could expand up to 4 to 6 times its relaxed or unexpanded length.

84 PMG contended that his Honour inconsistently construed “an increase in water pressure” and “for increasing the water pressure” in integer 1.7 of the Patents (which the judge found was “created” by the flow restrictor) ([60] and [64]) and the “said increase in water pressure” and “said increase in fluid pressure” in integer 1.8 (which the judge found was the result of frictional effects and the presence of a flow restrictor, not limited to the increase caused by the flow restrictor) ([78]).

85 PMG contended that the pressure increase referred to in integer 1.7 of each Patent must be the same as the pressure which expands the inner tube in integer 1.8 and increases the length of the hose, given the use of the word “said” in integer 1.8. In other words, “said” was to be construed literally. We note at this point that this was the only substantive argument raised by PMG to support its construction. PMG referred to Memcor Australia Pty Ltd v GE Betzdearborn Canada Company (2009) 81 IPR 315 at [31] per Jagot J, where it was found that “said” referred back to the first mentioned item in a claim. But we do not consider that that case takes the debate before us very far as the word “said” in that case had to be construed in the light of the integers and claims that her Honour was then dealing with. PMG also contended that its construction was consistent with dictionary definitions: “said” means “named or mentioned before” (Macquarie Dictionary, 4th ed) and “already named or mentioned” (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 5th ed). We can agree with those literal meanings. But again, we are required to consider “said” in the context of the claims before us. PMG also referred to Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd v Coretell Pty Ltd (2011) 93 IPR 188 where a particular construction of the word “device” was rejected in part because it would lead to the same word having different meanings in different parts of the claim (see at [76] to [78] per Bennett, Gilmour and Yates JJ). But again we do not consider that that case is of much assistance, except to recognise that in construing the same word or phrase used in a claim(s), consistency should be maintained unless there is a good reason to depart therefrom i.e. where the skilled addressee would take a practical and scientific approach consistent with the context rather than a literal approach that was inconsistent therewith.

86 Moreover, PMG contended that in construing the claim (and in particular, the extent to which the fluid flow restrictor was responsible for increasing the length of the hose), his Honour relied heavily on the evidence of Mr Hunter (see [71] and [72]). PMG contended that Mr Hunter’s analysis was antithetical to a proper approach to construction, since it was premised on the basis that “All of the integers of the claim must be read with an understanding of the Patent Specification in mind, and not in isolation” (see the Joint Report, page 5, lines 123-124). PMG also contended that because the specification did not expressly provide that the increase in water pressure needed to occur as the result of the fluid flow restrictor only, Mr Hunter inappropriately read the claim down (see the third affidavit of Mr Hunter at [5.3]; Joint Report, page 5, lines 123 to 155). But even assuming PMG’s criticisms to have some force, none of those points establish that his Honour was in error in his ultimate construction of integer 1.8.

87 PMG then contended, as noted in Kimberly-Clark v Multigate Medical Products at [45] per Greenwood and Nicholas JJ, that a patentee is “presumed” to have good reason for introducing a limitation into a claim. But that passage does not use the language of presumption. Rather, their Honours said that “[a] patentee may have good reason for introducing a limitation into a claim”. We do not consider that it is useful to talk about presumptions in this context.

88 PMG also said that the consistory clause of the First Patent was broader than the claim. Accordingly, so it was said, it may be inferred that the claim was deliberately narrower than the description of the invention in the specification. Paragraph [0036] of the First Patent provided that the increase in fluid pressure expands the elongated inner tube thereby increasing the length of said hose to an expanded condition and that the hose is contracted to a decreased length. But the claim only provides that both the increase and decrease in length are substantial. But assuming this to be so does not assist in our view in construing integer 1.8. Further, we also do not consider that the difference in the language of [0037] significantly assists either party one way or the other.

89 PMG further contended that it would be possible to have a hose in which the fluid flow restrictor was alone responsible for a substantial increase in the length of the hose, as it said Professor Armfield explained (T 156 lines 23 to 27). We interpolate here that what Professor Armfield said was that it was “not necessarily a nonsense”. PMG said that an example of such a hose is also given in the specification of each Patent, at [0054]. In that example, the pressure at the nozzle (the relevant fluid flow restrictor) is 35 PSI and it is that 35 PSI which is said to be “enough pressure to cause” the hose to be “expanded to its maximum length”. It is said that this description is consistent with the wording of the claims. We do not agree that [0054] provides support for PMG’s submission in this respect.

90 Further, PMG contended that integer 1.9 calls for a substantially decreased length when there is a decrease in water pressure. But this was not a corollary of the increase caused by the flow restrictor. That is, there was no equivalence between the decrease or its cause and the increase and its cause. It is said that contrary to his Honour’s finding (see [73] and [117]), Professor Armfield did not accept that the decrease was the corollary of the “substantial increase” that resulted in the “expanded condition” of the hose. It was also said that there would not be a decrease in water pressure unless the hose was emptied. If the tap is turned off and the hose is blocked the pressure will be maintained. It is only when the pressure is released by the fluid flowing out of the hose (through the flow restrictor) that there is a decrease in length (Patents at [0058]).

91 Finally, PMG also put the argument that the expression “said increase in water pressure” meant that one comparator must start with water being in the hose under some pressure, which is then compared with another scenario where there is an increase of that pressure. In other words, one of the comparators was not a scenario where there was no water in the hose and hence no water pressure. It was said that to take that scenario and then introduce water into the hose was not an increase in water pressure, but rather the creation of water pressure. Building on that foundation, PMG then said that the only comparator scenarios that the “said increase in water pressure” could refer to were the difference between the red and blue lines depicted in the figure referred to earlier. That is, the comparator scenarios were between the water pressure measured in the “modified hose (no coupler)” scenario as compared with the “standard hose (including coupler/flow restrictor)” scenario. Accordingly, so the argument went, the reference to “said increase” must be a reference to the effect produced only by the restrictor added to or being part of the second coupler.

92 But the difficulty with PMG’s belated contention is that:

(a) it was only put for the first time on appeal and accordingly was not dealt with by the parties or the primary judge below;

(b) it was not dealt with by or put to any of the expert witnesses;

(c) it was accepted by the parties and the witnesses below (and the primary judge) that the words “increase in water pressure”, putting to one side the word “said” for a moment, could be a reference to a scenario where one of the comparators was the situation starting with where there was no water in the hose as compared with a scenario where water was introduced.

93 Accordingly, we have put this final and late argument to one side given that to permit it to be now raised would cause inherent unfairness.

(b) Analysis

94 In our opinion, his Honour was correct to construe integer 1.8 such that the “said increase in water pressure” was a reference to the overall increase in water pressure within the hose resulting from the tap turned on.

95 When water flows through the hose, there will be resistance to the water flow. The resistance is caused by two factors (Joint Report and reasons at [70] to [77]). First, it is caused by the frictional effects of the water flowing past the walls of the inner tube of the hose. Second, it is caused by the fluid flow restrictor in the downstream coupler or attached thereto. A skilled addressee would be aware that in a dynamic system where water is flowing through the hose, expansion will be caused by both the restrictor and the frictional effects caused by the flow through the hose (reasons at [77]).

96 If a trigger nozzle is attached to the hose, and acts as a fluid flow restrictor, it will affect pressure. Further, frictional effects from fluid flow will also affect pressure. But when the nozzle restricts or chokes flow to zero, frictional effects will be negligible.

97 For the purposes of integer 1.8, the “said increase in water pressure” is not just limited to an increase in pressure caused by the fluid flow restrictor which integer 1.7 is referring to. It is an increase which is caused by both:

(a) the presence of the restrictor; and

(b) friction caused by the flow of water through the hose.

98 PMG’s construction relies on a literal view of the word “said”. But a number of observations may be made.

99 First, the language “said increase in water pressure” should be construed in the overall context of that paragraph of claim 1, indeed the entirety of claim 1 itself.

100 Second, the language “said increase in water pressure” should be construed in the overall context of the specification. Although the specification and the claims explain that the inclusion of a fluid flow restrictor is necessary, the language of the specification describes the overall pressure increase within the hose (from the restrictor and the frictional effects although the latter is not expressly mentioned); see the Patents at [0001], [0030], [0031], [0048], [0051], [0053], [0054], [0058] and [0063].

101 Third and relatedly, some support for his Honour’s construction comes from the expression “expanded condition”. This refers to the expanded hose by having pressurised water introduced into it. But the expansion is from the two pressure effects that we have identified.

102 Fourth and relatedly, integer 1.9 uses the language “contracting to a substantially decreased or relaxed length when there is a decrease in water pressure”. This is a reference to an overall decrease in water pressure within the hose where the water pressure reduces down to atmospheric pressure and the hose relaxes (see reasons at [73], [74] and [117] and Professor Armfield’s evidence at T 195 line 27 to T 196 line 17). The words “substantially decreased or relaxed length” in integer 1.9 is the converse of the expansion referred to in integer 1.8. The reference to “decrease in water pressure” in integer 1.9 is the converse of “said increase in water pressure” in integer 1.8.

103 Fifth, PMG does not offer any practical or scientific reason supporting its literal view.

104 Sixth, PMG has made reference to the fact that “said” appears 22 times in claim 1 of each of the Patents. It is asserted that on each occasion it “clearly refers” to an item which was previously mentioned. First, that assertion seeks to foreclose the issue under discussion. Second, perhaps the frequency of use may in fact demonstrate over-use or, at least, increase the risk of an inadvertent use.

105 Seventh, PMG has asserted that “said” is a word of reference and not a technical term that needs expert evidence. But that assertion rather distorts the issue. One is considering the word in the context of integer 1.8, more broadly claim 1, and even more broadly the specification. In looking at the word in these contexts and how a skilled addressee would construe claim 1, expert evidence is useful and probative.

106 Eighth, PMG has asserted that Blue Gentian’s approach is “misconceived” as it begins with the field of the invention and a paraphrase of the invention rather than the words of the claim. We consider there to be nothing in that criticism. After all, integer 1.1 is for a “garden hose”. That is both the language of claim 1 and the context within which the claim is to be construed.

107 Ninth, it is true that neither in the claim nor in the body of the specification is express reference made to frictional effects. But for a skilled addressee, such frictional effects are likely to be a given and not necessary to make express reference thereto. Perhaps this is why integers 1.7 and 1.8 are expressed the way they are. They proceed on the undoubted basic knowledge of the skilled addressee and hence no reference needed to be made.

108 Tenth, Professor Armfield accepted in the Joint Report at lines 89 to 94 that there was an incorrect use in language in claim 1 dealing with the use of the word “increase”. If that be accepted, it is less of a step to accept that there were other imprecisions in the use of language — for example, one of the uses of the word “said”.

109 Eleventh, his Honour was quite entitled to rely upon (see at [71] and [72]) the evidence of Mr Hunter generally (third affidavit at [5.3] to [5.7] and Joint Report at lines 117 to 133 and 223 to 303), even if some aspects were not properly expressed within the framework of the proper constructional approach to be used. To accept such imperfections is not to deny the force of his evidence as to how a person skilled in the art would look at the claims practically and in context in terms of his experience with the design and dynamics of hoses.

110 Twelfth, Professor Armfield accepted that the skilled addressee reading the specification and claims would consider the effect on the hose of the overall increase in pressure from the two causes (restrictor and frictional effects) and not just the one cause (restrictor). His Honour was entitled to rely upon that evidence (see at [73] and [77]).

111 In summary, we consider that the present case is one of those exceptional cases where a skilled addressee would not construe the integer with the word “said” in such a literal way. First, to a skilled addressee it would make little, if any, scientific or technical sense. It does not accord with how the operation of a garden hose and the causes of an “increase” in pressure would be understood. Second, a skilled addressee reading the integer and claim in the context of the specification as a whole would not use such a literal interpretation. Third, the skilled addressee when reading integer 1.8 in the context of and with integers 1.7 and 1.9 would appreciate that a literal meaning of “said” was not being used. This is one of those occasions referred to by Lord Hoffmann as not expected to happen very often. Moreover, and again to use his language, there is a “rational basis” in the present case for departing from the literal use of the word “said”. His Honour departed from this literal use, and we see no error in his approach.

112 Alternatively, although his Honour did not so find, another way to read integer 1.8, accepting for the sake of the argument that “said” is to be construed as contended for by PMG, is perhaps to read “said increase in water pressure” caused by the restrictor as not being the sole cause for the expansion of the hose but only a cause. This is also consistent with integer 1.9. It is also how a skilled addressee might read it practically and in context. Further, it is also consistent with the use of the indefinite article “an” in integer 1.7, which uses the expression “fluid flow restrictor creates an increase in water pressure”. That language does not negate other causes as also producing an increase in pressure. It is not expressed as “fluid flow restrictor creates the increase in water pressure”. Further, on that construction, the word “thereby” in integer 1.8 would be read as “thereby together with other causes”. It would have also been open to his Honour to have construed claim 1 of each Patent accordingly.

appeal Ground 7: Indirect Infringement

(a) Introduction

113 Blue Gentian at trial claimed that PMG directly infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent by importing, offering to sell and otherwise disposing of, selling or otherwise disposing of and keeping a garden hose marketed as the Pocket Hose. The earliest date of alleged infringement was 15 November 2012. The publication dates of the First Patent and the Length Patent were 17 January 2013 and 18 April 2013 respectively.

114 Blue Gentian at trial also asserted that PMG had indirectly infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent pursuant to inter alia s 117(2)(c) of the Act because the Pocket Hose had been supplied together with instructions for use, where such use would infringe the Patents.

115 In relation to indirect infringement s 117 relevantly provided as follows:

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

(a) if the product is capable of only one reasonable use, having regard to its nature or design — that use; or

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product — any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; or

(c) in any case — the use of the product in accordance with any instructions for the use of the product, or any inducement to use the product, given to the person by the supplier or contained in an advertisement published by or with the authority of the supplier.

116 The supply of a product with instructions, which would infringe a claim if used as instructed, would also constitute infringement under s 117(2)(c); see Beadcrete Pty Ltd v Fei Yu (t/as Jewels 4 Pools) (No 2) (2013) 100 IPR 188 at [126]–[128] per Jagot J, referred to with approval on appeal (Fei Yu (t/as Jewels 4 Pools) v Beadcrete Pty Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 516 at [82] to [86] per Dowsett, Middleton and Robertson JJ).

(b) His Honour’s findings

117 His Honour stated in his reasons ([203]) that PMG did not challenge Mr Hunter’s conclusion in his first and second affidavits that the Pocket Hose had each of the features of claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent, and 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent (assuming the construction issues to have been found in favour of Blue Gentian). He also stated that Professor Armfield confirmed that he did not disagree with any of those conclusions.

118 His Honour also stated that Professor Armfield conducted a number of experiments on the Pocket Hose in which the hose approximately doubled in length from the contracted state to the expanded state. His Honour stated that on the basis of the construction of claim 1 of each of the Patents that he favoured, there would be a substantial increase in the length of the garden hose, or an increase in the length of the garden hose by, relevantly, at least a factor of two.

119 Accordingly, on his Honour’s interpretation of claim 1, he held that direct infringement was established.

120 As to the question of indirect infringement, his Honour made the following findings. His Honour found ([211]) that Professor Armfield accepted that where the trigger nozzle completely blocked flow, the features of claim 1 were satisfied since the fluid flow restrictor was responsible for the entire elongation of the hose to its “expanded condition”. This resulted because the closed trigger nozzle “redistribute[d] that pressure in a way that the upstream pressure [was] greater than it otherwise would be”. He further accepted that even if PMG’s and Professor Armfield’s construction of “said increase” in integer 1.8 was correct, the Pocket Hose with a closed trigger nozzle attached had all the features of claim 1.

121 His Honour referred to the fact ([212]) that Professor Armfield also confirmed that the experiments that he had designed involved conducting all measurements at a state of equilibrium, and that was consistent with his understanding of what the claims required to be measured. He further confirmed that position specifically in relation to the closed trigger nozzle (zero flow) condition.

122 Relating to the elements of s 117(2)(c), his Honour found ([213]) that the instructions supplied by PMG with the Pocket Hose instructed a user to connect one end of the hose to a tap, connect the other end of the hose to a spray nozzle, (with the nozzle in the off position), and turn on the water supply and allow the hose to fully expand before using the hose.

123 On this basis, and even on PMG’s and Professor Armfield’s approach to the construction of integer 1.8, his Honour found that the use of the Pocket Hose as instructed involved use of a garden hose having all of the features of the pleaded claims.

124 His Honour said that accordingly PMG had supplied the product, where the use of the product was to be in accordance with instructions given to the consumer by PMG, which instructions taught the use of a trigger nozzle in a closed position which then entailed an infringing use of the product.

125 In summary, his Honour held ([216]) that claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent, and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent were directly infringed (if Blue Gentian’s and his Honour’s construction of integer 1.8 applied), and indirectly infringed pursuant to s 117(2)(c) of the Act (even if PMG’s construction of integer 1.8 applied).

(c) PMG’s arguments on indirect infringement

126 PMG contended that the judge erred in finding that Professor Armfield accepted that where the trigger nozzle of the Pocket Hose completely blocked flow, the features of claim 1 were satisfied, even if Professor Armfield’s approach to construction was accepted. PMG contended that Professor Armfield made no such concession. It contended that in any event, the evidence was that the flow restrictor was only responsible for an average 22% increase in the length of the hose where the fluid flow restrictor was a plug connected to the second coupler and completely blocked flow. It was said that such expansion could not be seen as substantial. We will address that contention later.

127 More generally, Professor Armfield’s evidence was that the expansion of the hose was caused largely by frictional losses, with the flow restrictor making only a minor contribution (see his Honour’s reasons at [70]). Mr Hunter’s evidence was that frictional loss or the flow restrictor or a combination of both caused expansion [71]. This evidence was accepted by the judge [72]. But of course in the scenario where the trigger nozzle completely blocked flow, there would be no relevant frictional effects, which is the relevant scenario on the indirect infringement case under discussion.

(d) Analysis

128 In our opinion, even if the primary judge’s construction of integer 1.8 was incorrect, his Honour was correct in finding that PMG nonetheless indirectly infringed the Patents pursuant to s 117(2)(c) by its sale of the Pocket Hose with instructions to use it with a trigger nozzle fully closed. The instructions supplied by PMG with the Pocket Hose “instruct[ed] a user to connect one end of the hose to a tap, connect the other end of the hose to a spray nozzle, (with the nozzle in the off position), and turn on the water supply and allow the hose to fully expand before using the hose” (reasons at [213]). Those instructions were not preliminary to use but part of use. In any event, for a standard suburban garden, you might want to carry the hose to different parts of the garden to water with the tap turned on, but with no water released until you arrived at the desired location within the garden to then open the nozzle. At the least, that would be a sensible water saving measure.

129 As his Honour correctly found, even on PMG’s construction of integer 1.8, PMG infringed claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the First Patent and claims 1, 2 and 5 of the Length Patent because:

(a) where the trigger nozzle completely blocks the flow of water, the “fluid flow restrictor is responsible for the entire elongation of the hose to its ‘expanded condition’” (reasons at [211]); and

(b) experiments showed that the Pocket Hose doubled in length from the contracted state to the expanded state which amounted to a “substantial increase” in the length of the garden hose within the meaning of the First Patent and an increase in the length of the garden hose by “at least a factor of two” within the meaning of the Length Patent (reasons at [204]).

130 When the fluid flow restrictor is fully choked (as occurs with a trigger nozzle used in accordance with PMG’s instructions), there is no flow of water through the hose and hence no relevant frictional effects. In that scenario, and in the context of determining infringement, the proper comparison (as his Honour rightly made) was between:

(a) the length of the hose in its original condition (prior to the tap being turned on); and

(b) the length of the hose after the tap was turned on with the hose fully choked by the trigger nozzle.

In either comparator there is no water flowing through the hose and no relevant frictional effects. The experimental evidence adduced before his Honour demonstrated that there was a doubling in the length of the hose caused by the fully choked trigger nozzle (in accordance with PMG’s instructions for the use of the Pocket Hose with a trigger nozzle). This met the requirements of claim 1 of both Patents (reasons at [214]) even on PMG’s construction of integer 1.8 in relation to the “said increase” aspect.

131 PMG has asserted that the evidence demonstrated that the fully choked flow restrictor was only responsible for an “average 22% increase” in the length of the hose. PMG contended that this did not amount to a substantial increase or increase of at least a factor of two within the meaning of the latter aspect of integer 1.8. But we agree with Blue Gentian that that percentage increase used the wrong comparator for the purposes of calculation. It measured the difference between:

(a) the hose with a fully choked fluid flow restrictor (equivalent to a trigger nozzle in the closed position) (zero flow and no frictional effect); and

(b) a hose with the fluid flow restrictor removed but with the water tap still on (water flow with frictional effect).

132 But that comparison ignored the introduction of a substantial frictional effect caused by the flow of water in the comparator (b) scenario thereby generating PMG’s advantageous mathematical outcome of 22%. But that comparator was erroneous. Integer 1.8 is addressing what causes the expansion. In order to get the expansion produced by the fully choked case as instructed for the Pocket Hose, one is moving from the starting position (and true comparator) being the length of the hose in its original condition prior to the tap being turned on.

133 In our opinion, no error has been demonstrated in his Honour’s analysis of indirect infringement, even assuming in favour of PMG its construction of integer 1.8. But in any event, its construction of integer 1.8 is incorrect. Accordingly, there has also been direct infringement as his Honour found.

grounds 1, 4 and 5(a) of notice of appeal: Innovative Step

134 PMG has contended that the Patents lacked an innovative step when compared with the disclosure in the McDonald Patent. The publication date of the McDonald Patent was 2 January 2003. The priority date of each of the Patents is 3 April 2012.

(a) The McDonald Patent

135 The McDonald Patent is entitled “Self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen mask” (reasons at [91] to [95]).