FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Tamawood Limited v Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) [2015] FCAFC 65

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and submit within 14 days agreed or competing proposed orders which reflect the reasons for judgment published today.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 235 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 Respondent |

JUDGES: | GREENWOOD, JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 MAY 2015 |

WHERE MADE: | SYDNEY VIA VIDEO-LINK TO BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and submit within 14 days agreed or competing proposed orders which reflect the reasons for judgment published today.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 240 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | SHANE ANDREW O’MARA Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 First Respondent MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Second Respondent RAYMOND JOHN MCDONALD SWEENEY Third Respondent |

JUDGES: | GREENWOOD, JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 MAY 2015 |

WHERE MADE: | SYDNEY VIA VIDEO-LINK TO BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and submit within 14 days agreed or competing proposed orders which reflect the reasons for judgment published today.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 223 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 Appellant |

AND: | HABITARE DEVELOPMENTS PTY LTD (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) (RECEIVERS AND MANAGERS APPOINTED) ACN 122 935 497 First Respondent BLOOMER CONSTRUCTIONS (QLD) PTY LTD ACN 071 344 100 Second Respondent PETER FREDERICK O'MARA Third Respondent DAVID GAVIN JOHNSON Fourth Respondent WAYNE NORMAN BLOOMER Fifth Respondent MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Sixth Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 235 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 240 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | SHANE ANDREW O’MARA Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 First Respondent MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Second Respondent RAYMOND JOHN MCDONALD SWEENEY Third Respondent |

JUDGES: | GREENWOOD, JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ |

DATE: | 18 MAY 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY VIA VIDEO-LINK TO BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

greenwood j:

1 These proceedings are concerned with three appeals (and related notices of contention) arising out of a judgment in this Court in proceedings in which the appellant in the first appeal, Tamawood Limited (“Tamawood”), claimed, put simply and relevantly for present purposes, relief against a developer, Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (“Habitare”), and its related entities, Habitare’s architects, Mondo Architects Pty Ltd (“Mondo”), and Habitare’s builder, Bloomer Constructions (Qld) Pty Ltd (“Bloomer”), arising out of contended infringements (and authorisations of those infringements) of Tamawood’s copyright subsisting in plans for particular project homes described as the Torrington and the Conondale/Dunkeld (which I will call the “Dunkeld”) by two-dimensional and three-dimensional reproduction of the copyright works.

2 Relief was also claimed in the principal proceeding against a number of individuals: Mr Peter O’Mara, a director of Habitare; Mr David Johnson, another director of Habitare (although Mr Johnson’s trustee in bankruptcy did not appear in the principal proceedings to resist Tamawood’s claims against Mr Johnson); and Mr Wayne Bloomer, a director of Bloomer. Apart from Tamawood’s original proceedings, Mondo brought proceedings against Habitare, Mr Peter Speer who worked for Habitare, and Mr Shane O’Mara (Mr Peter O’Mara’s son) who also worked for Habitare, for contended contraventions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) which, of course, is now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

3 I have had the benefit of reading in draft the joint reasons for judgment of Jagot and Murphy JJ. In those reasons, their Honours set out in more precise detail the various parties to the primary proceedings and the nine issues agitated before the Full Court in respect of the three appeals and the notices of contention. I set out those nine issues and my position on each issue at [92] to [100] of these reasons.

4 In these reasons, I propose to address the question of whether Tamawood’s copyright in the plan for the Conondale/Dunkeld duplex was infringed in the way contended for by Tamawood on appeal.

5 A short synopsis of the background facts (particular aspects of which will need to be examined in a little detail) is, for present purposes, this. Tamawood is a company which produces plans for low cost project housing in Australia which it uses for building dwellings on relevant sites. Habitare was at all relevant times a company involved in the construction of “low-cost, intensive housing projects in Brisbane”: Tamawood Limited v Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (No 3) [2013] FCA 410 (the “primary judgment”) at [7]. In 2005, Habitare (through related entities continued reference to which is no longer relevant), engaged in discussions with Tamawood with a view to Tamawood producing plans for low cost housing to be built by Tamawood for Habitare at two sites described as Hamish Street, Calamvale in Brisbane and Gawler Street/Norris Road, Brackenridge in Brisbane.

6 Plans relating to the two sites were produced by Tamawood for a single-storey duplex called the Dunkeld, and a two-storey duplex called the Torrington. Habitare then lodged applications with the Brisbane City Council so as to obtain development approval for a housing development on each site. Habitare, with Tamawood’s agreement, lodged Tamawood’s plans for the Torrington and the Dunkeld with the Brisbane City Council as part of the development approval application. The Brisbane City Council issued a development approval for the Hamish Street development on 7 July 2006. Condition 1 of the development approval was, relevantly, in these terms:

Carry out the approved development generally in accordance with the approved drawing(s) and/or document/s.

GUIDELINE

The condition refers to the approved plans, drawings and documents to which the approval relates and is the primary means of defining the extent of the approval. Approved Plans, drawings and Documents are stamped referred to in the Approval and are dated to reflect the date of approval by the Council’s Delegate.

7 The Brisbane City Council issued a development approval for the Gawler Street/Norris Road development on 1 March 2006. Condition 1 of the approval is in the same terms as Condition 1 quoted at [6] of these reasons.

8 Habitare and Tamawood were ultimately unable to agree upon the terms and conditions of a commercial engagement under which Tamawood would build houses based on its plans on each site for Habitare. Habitare did not use Tamawood to construct dwellings on either site. In order to develop plans for dwellings to be built on each site, Habitare approached Mondo to develop house plans for construction on each site. In order to comply with Condition 1 of each development approval, the dwellings to be constructed on each site were required to be “generally in accordance with the approved drawing(s) and/or document/s”. The approved drawings were the Tamawood plans. Mondo prepared plans for dwellings for each site to enable building certificates to be obtained for construction. Those building certificates were obtained by Habitare based on the Mondo plans. Habitare ultimately engaged Bloomer to construct or complete construction of dwellings on each site. Structures reflecting a three-dimensional reproduction of the Mondo plans were erected on each site.

9 Although the plans for dwellings on each site were required to be generally in accordance with the approved drawings (and thus Tamawood’s drawings for Torrington and Dunkeld), Mr Raymond Sweeney, a director of Mondo, gave evidence before the primary judge in an affidavit sworn 20 September 2011, that the parameters of the development approval included such things as the gross floor area; the size, shape and height of the dwellings; the number of dwellings; the distances between dwellings; and the distances between the dwellings and the boundaries. Mr Sweeney also gave evidence that based on his experience as an architect, the internal design of the dwellings is not “evaluated” or taken into account by the Brisbane City Council in the development assessment process except where it creates an impact on one of the assessment parameters. At [200], the primary judge notes the evidence of Mr Scott Richards (set out in an expert report) to the effect that amendments which can be considered as “generally in accordance with” an approved development (for the purposes of the Integrated Planning Act 1997 (Qld)) relate to:

… less substantial matters that have no bearing on town planning generally and no impact on town planning criteria or development assessment matters (para 4.2.14). Materially, Mr Richards opines further that such amendments can include amendments to internal layouts, such as removal of walls and rearrangement of rooms, but that more substantial amendments proposed to an approved development would require lodgement of a new development application (para 4.2.14 and para 4.2.27).

[emphasis added]

10 At [201], the primary judge observes, however, that Mondo was under some pressure to produce documents which “generally accorded” with the plans of Tamawood which had already received development approval.

11 Arising out of these events, Tamawood contended that the Mondo plans for the single-storey and two-storey duplexes infringed its copyright in the Dunkeld and Torrington plans respectively with the result that the two-dimensional drawings and the three-dimensional structures on the sites were reproductions in a material form of Tamawood’s copyright works in each case. As mentioned, Tamawood maintained proceedings against the developer (Habitare), the builder (Bloomer), Mr Bloomer, the directors of Habitare (Mr Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson) and Mondo.

12 In the result, the primary judge ultimately made a number of declarations on 7 May 2014 arising out of the trial of the action and the reasons for judgment published on 7 May 2013. The relevant declarations were these:

2. … in making [the two-storey] drawings for the purposes of the Habitare developments at the Calamvale and Brackenridge sites, Mondo infringed [Tamawood’s] copyright in the Torrington drawings.

3. … in building dwellings at the Calamvale and Brackenridge sites in accordance with Mondo’s [two-storey] drawings, the Habitare Respondents infringed [Tamawood’s] copyright in the Torrington drawings.

4. … the Habitare Respondents authorised Mondo’s infringement of [Tamawood’s] copyright in the Torrington drawings …

5. … the Habitare Respondents authorised Bloomer Constructions’ innocent infringement of [Tamawood’s] copyright in the Torrington drawings in providing to Bloomer Constructions the [two-storey] drawings created by Mondo for use in the construction of dwellings at [the] Calamvale and Brackenridge sites.

6. … the Habitare Respondents engaged in a common design to infringe [Tamawood’s] copyright [in the Torrington drawings].

7. … [Tamawood] is not entitled to any additional damages pursuant to section 115(4) of the Copyright Act.

13 Apart from these declarations, the primary judge granted two injunctions and made costs orders. In the orders made on 7 May 2014, the “Habitare Respondents” are defined to mean Habitare and three Habitare entities no longer relevant for present purposes. As appears from the declarations, the primary judge found for Tamawood in respect of the Torrington two-storey plan but not the single-storey Dunkeld plan. The primary judge rejected Habitare’s contention (and that of Mr Shane O’Mara) that Tamawood had conferred upon Habitare and Mondo a licence (contractual or non-contractual) for the purposes of s 36(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the “Act”) to exercise the reproduction right in s 31(1) of the Act in Tamawood’s plans. The primary judge also dismissed Tamawood’s claims against the directors of Habitare, Mr Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson for authorisation of Habitare’s infringement of Tamawood’s copyright in the Torrington plans. As reflected in the declarations, the primary judge found that Tamawood was not entitled to any additional damages pursuant to s 115(4) of the Act as against Habitare or the directors of Habitare or Mondo in respect of conduct in connection with the Torrington plans. The primary judge also made declarations on 26 November 2013 in these terms:

1. In building dwellings at the Calamvale and Brackenridge sites in accordance with Mondo’s [two-storey] drawings, Bloomer Constructions innocently infringed [Tamawood’s] copyright in the Torrington drawings.

2. Wayne Norman Bloomer authorised Bloomer Constructions’ innocent infringement of the applicant’s copyright in the Torrington drawings referred to in the preceding order.

3. In respect of the infringements of [Tamawood’s] copyright by Bloomer Constructions and Wayne Norman Bloomer those respondents made out a defence under s 115(3) of the [Act], commonly known as “innocent infringement”.

14 In the Mondo proceedings, the primary judge found contraventions of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) by Habitare and found that Mr Speer and Mr Shane O’Mara were knowingly concerned in Habitare’s contraventions and thus also liable to Mondo in respect of those contraventions by Habitare.

15 In their draft reasons for judgment, Jagot and Murphy JJ identify nine issues that arise on these appeals (and the notices of contention) for determination. I agree that these proceedings before the Full Court raise those nine issues and I will not repeat at this point in these reasons a list of each separate question. Apart from later setting out my position on each of the nine issues before the Full Court, the principal question I propose to address in these reasons is this: If Tamawood is not precluded by reason of the pleadings in the proceeding and the way in which the case was conducted before the primary judge from arguing that an inference of indirect copying by Mondo should be drawn, did the primary judge err in finding that Mondo did not infringe Tamawood’s copyright in the Dunkeld plan?: Issue 3 before the Full Court.

16 I should immediately say that I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ that Tamawood is not precluded, by reason of the pleadings or the conduct of the case before the primary judge, from arguing that an inference of indirect copying by Mondo should be drawn. The question then is whether having regard to all the relevant circumstances such an inference should be drawn. For my part, I respectfully disagree with the views of Jagot and Murphy JJ on that question. In my view, Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan does not infringe the copyright subsisting in Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan for the reasons set out in these reasons.

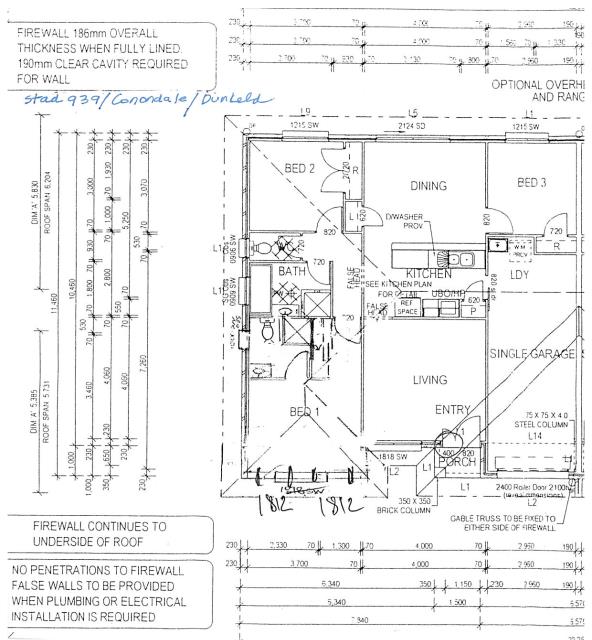

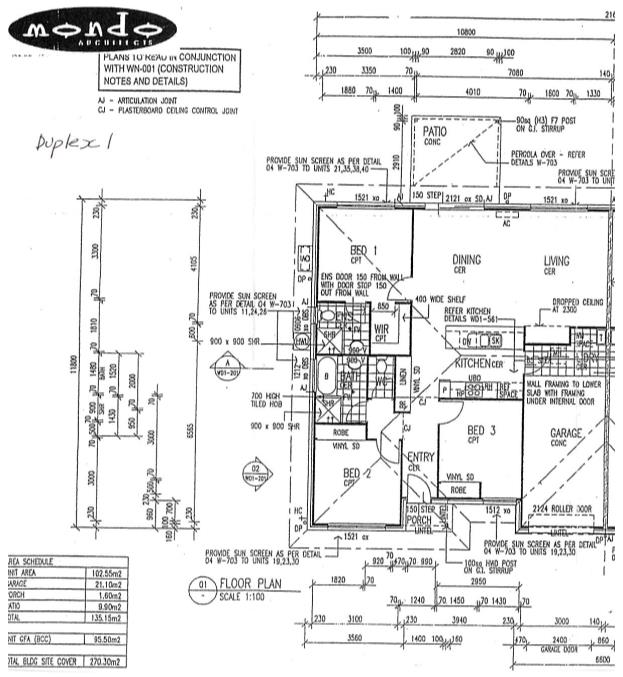

17 In the course of the appeal, counsel for Tamawood handed up to the members of the Court (with copies to the parties) two enlarged plans which frame, at least so far as the plans are concerned apart from other contextual issues, the question of whether Mondo’s plan for a single-storey duplex (Duplex 1) is a reproduction in a material form of Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan. The plan in suit is called the Dunkeld plan but that plan is sometimes known as “Stad 939” and also Conondale/Dunkeld. Each enlarged plan is a plan for a single-storey duplex. Each plan contains a layout for such a duplex on each side of a concrete block common wall and thus the floor plan for the right-hand side of that common wall is a mirror image of the plan for the left-hand side of the common wall. It is therefore only necessary to have regard to the plan for the left-hand side of the duplex in each case. In the reasons for judgment of the primary judge, there are many A4 reproductions of plans which are very difficult to read. Similarly, annexed A4 plans to affidavits are difficult to read. No doubt for this reason, counsel for Tamawood delivered up an enlargement of the two immediately relevant plans in suit on this issue. Accordingly, I have incorporated within these reasons the plan for the left-hand side of each of the enlarged plans as delivered up by counsel for Tamawood. The first plan set out below is Tamawood’s copyright work in suit labelled “Stad 939/Conondale/Dunkeld” and the second plan set out below is Mondo’s plan for its Duplex 1:

Stad 939 Conondale/Dunkeld

Mondo’s Duplex 1

18 I will return to each of these plans later in these reasons.

Some relevant principles

19 In S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 472, Gibbs CJ observed (with Mason J agreeing at 478 and Brennan J agreeing at 491) that the notion of reproduction for the purposes of copyright law involves two elements: resemblance to, and actual use of the copyright work, or put another way, a “sufficient degree” of objective similarity between the two works in suit and “some causal connection” between, in this case, Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s plan. The Chief Justice then adopted at 472 the observations of Lord Reid in Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 W.L.R. 273 at 276 that “[b]roadly, reproduction means copying, and does not include cases where an author or compiler produces a substantially similar result by independent work without copying” [emphasis added]. These two issues of a “sufficient degree of objective similarity” between the two works and “some causal connection” between them are discrete yet overlapping issues.

20 The issues are discrete in the sense that in the absence of some causal connection, objective similarity (or for that matter a high degree of reconciliation) between the two works does not give rise to reproduction for the reasons Lord Reid identifies. They overlap, however, because an assertion of a causal connection between the claimant’s work and that of the contended infringer is often made on the footing that an inference of access to and use of the claimant’s work (in the absence of an admission) ought to be drawn because of, generally, a high degree of similarity or striking similarity between the two works (coupled with opportunity (access)) and often also coupled with a failure by the contended infringer to adequately explain that party’s assertions of independent origination (authorship) of the work said to infringe: an analysis sometimes called “probative similarity” (Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd (“Eagle Homes v Austec”), (1999) 87 FCR 415, Lindgren J at [84], Finkelstein J agreeing at [111].

21 The issues are also discrete in the sense that once the issue of a causal connection is made good (absent an admission) by reason of an inference drawn based upon the degree of similarity (relevant in the particular case) between the two works, a further question must nevertheless be addressed of whether there is a “sufficient degree” of objective similarity so as to amount to reproduction of the copyright work in suit: sometimes called the “second limb” or more commonly “substantial similarity” (Eagle Homes v Austec at [85]).

22 Care needs to be taken with the use of the “rolled up” term “copying”. Generally, when the term “copying” is used in the authorities, the term is used in the context of the making of a finding of fact of whether a causal nexus has been made good between the two works. That is to say, use of the copyright work consciously or unconsciously “although it must be said that in the case of works such as architectural plans it would be surprising to find many cases of unconscious copying”: Clarendon Homes (Aust) Pty Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd (“Clarendon v Henley Arch”) (1999) 46 IPR 309, Heerey, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ at [24].

23 Once the causal link is made good a further question is whether the whole or a substantial part of the copyright work has been reproduced.

24 In Clarendon v Henley Arch, the Full Court said this at [27]:

The question whether, in the absence of an admission, copying (that is a causal nexus between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work) is established is not the same as the question whether, once copying has been established, the whole or a substantial part of the plaintiff’s work has been appropriated. We accept that very often the two issues will overlap. But nevertheless they are discrete issues and the answer to one does not necessarily produce an answer to the other. For example, in order to prove that there has been a copying it is usual to attempt to show opportunity, that is access to the plaintiff’s work, and such similarities between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work as makes independent creation by the defendant unlikely. Such similarities may or may not be substantial. They can include common error, sometimes deliberately inserted in the plaintiff’s work. Paradoxically, there will be occasions where dissimilarities may provide the basis for an inference of access and copying.

[emphasis added]

25 See also Tamawood Limited v Henley Arch Pty Ltd (2004) 61 IPR 378, Wilcox and Lindgren JJ at [44]; Pacific Gaming Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Leisure Industries Pty Ltd (“Pacific Gaming v Aristocrat”) (2001) 116 FCR 448, Sackville, Finn and Kenny JJ at [19].

26 Whether a causal link is made good is a question of fact.

27 To the extent that proof of a causal link rests upon an inference drawn from primary facts of access, opportunity and objective similarities between the relevant works, the objective similarities would normally need to be “sufficiently great” (Pacific Gaming v Aristocrat at [19]) or in the case of project home plans “[i]t is understandable that in such cases of project home plans there will be an emphasis on the need for close similarity if infringement [an observation made in the context of probative similarity or causal link] is to be proved”: Eagle Homes v Austec at [84].

28 However, the two elements of causal link and sufficient objective similarity “are but aspects of ‘reproduction’” and it can be “artificial to consider them separately … where actual copying [access to and use of the copyright work] is found to have occurred”: Eagle Homes v Austec at [98]. That follows because a finding of copying “can add significance to objective similarity”: Eagle Homes v Austec at [98].

29 It should also be remembered that the notion of reproduction of a work in a material form (s 31(1)(a)(i) of the Act) includes a reference to reproduction of a substantial part of the work (s 14(1) of the Act) and thus the greater includes the lesser in the sense that the Act recognises a distinction between the “undifferentiated whole of a copyright work” (for example, a floor plan for a project home) and a substantial part of the undifferentiated whole of that work: see Eagle Homes v Austec at [70]. Thus, the copyright owner might seek to establish reproduction by showing “a sufficient degree of objective similarity” in the undifferentiated whole of the plan, or alternatively, by showing a substantial part of the work has been reproduced, or both.

30 Where the issue is whether the undifferentiated whole of the copyright work has been reproduced (rather than the isolation of a particular part of the work and then an examination of the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the part said to be taken), the question to be determined in circumstances where the copyright work is not precisely or exactly taken, is how closely must the impugned work resemble the copyright work before reproduction is made out. The answer, put generally, is that “a sufficient degree of objective similarity” in the circumstances of each case must be proved. The sufficiency of that degree is, however, influenced by the overlapping nature of the otherwise discrete questions.

31 In Eagle Homes v Austec, Lindgren J at [85] (Finkelstein J agreeing at [111]), in the context of a finding of actual copying (that is, opportunity, access and probative similarity) found error in reasoning to the following effect: because project home plans are simple drawings of the “commonplace”, lack “marked originality” and can be expected to have some similarities (as project home plans share certain features), it follows that sufficient objective similarity could not exist in the absence of a very close resemblance between the two project house plans. Lindgren J regarded that reasoning as flawed which led his Honour to also observe, in the context of a causal link made good by subjective copying, as follows at [86]:

It is reasonable, therefore, to think that copyright law is concerned to protect against subjective copying and that where subjective copying occurs there can be expected to be found an infringement, unless it transpires that the product is so dissimilar to the copyright work that the copyright work can no longer be seen in the work produced.

[emphasis added]

32 And at [91], Lindgren J also observed:

In no case concerning project homes of which I am aware where there has been such a finding of actual copying, has it been held that nonetheless the copier will not have infringed copyright unless there is in addition an extraordinarily close resemblance between his or her drawing and the copyright work. Rather, I think that the issue of sufficient objective similarity simply poses in the case of project homes, as in other cases, the usual question whether the copyright drawing can still be seen embedded in the allegedly infringing drawing, that is, whether the allegedly infringing drawing has adopted the “essential features and substance” of the copyright work: Hanfstaengl v Baines & Co [1895] AC 20 at 31 (Lord Shand) …

[emphasis added]

33 Thus, the Full Court regarded the issue, in the case of project home plans, of whether sufficient objective similarity exists as simply raising the usual question which is: Can the copyright drawing still be seen embedded in the impugned drawing or, put another way: has the impugned drawing adopted the essential features and substance of the copyright work?

34 Thus, the notion that there must be, in the case of plans for project homes, an extraordinarily close resemblance between the copyright work and the impugned work is “too stringent” a test for determining a sufficient degree of objective similarity so as to amount to reproduction. In expressing the test in the way described, Lindgren J for the Full Court was seeking to demonstrate that the near absolutism of exact reproduction (as a test) reflected in the reasoning of the primary judge (in that case) of the need for “extraordinarily close resemblance” as the measure of a sufficient degree of objective similarity (in a case of proven copying) unnecessarily goes beyond, as a matter of principle, the statutory concept of reproduction as explained in the authorities.

35 His Honour’s adoption of terms of emphasis such as embedded in, essential features and substance of the work, simply reflect the notion that what is required in cases involving plans for project homes (like any other copyright work) is a sufficient degree of objective similarity in the particular circumstances of the particular case measured by reference to the essential features and substance of the copyright work in suit as expressed in the form of the floor plan (in this case) and the form of expression of the impugned plan by the contended infringer.

36 Three other things should be mentioned.

37 First, where reproduction is sought to be made good by reference to objective similarities in the undifferentiated whole of Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan, and Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan (should a causal link be made good) reproduction (that is, a sufficient degree of objective similarity) might find expression, in part, in the “layout and traffic flows and the shapes, proportions and interrelationships of the rooms and other spaces – elements which permeate the whole of the project home”: Eagle Homes v Austec at [74].

38 Second, where the contended infringer has not reproduced the precise or exact expression of the copyright work, and a sufficient degree of objective similarity between two works is sought to be made out by reference to elements such as those described at [37] of these reasons, questions will arise of whether, simply, ideas reflected in the copyright work have been engaged with, adopted and used resulting in the expression of the contended infringer’s plan or whether the very expression of the copyright work has been reproduced due to the sufficiency of the degree of objective similarity between the two works.

39 It is in this sense that causal connection and objective similarity also overlap yet remain discrete questions to be addressed.

40 Third, in Eagle Homes v Austec, Lindgren J (Finkelstein J agreeing) said that where subjective copying occurs an expectation of a finding of infringement arises (that is, an expected finding of a sufficient degree of objective similarity arises) unless the contended infringing work is so dissimilar to the copyright work that that work can no longer be seen in the impugned work. Reproduction is made out by an applicant when a sufficient degree of objective similarity is made good and the contended infringer has made actual use of the copyright work either directly or through an intermediary instructor. Actual use of the copyright work will necessarily “add significance” (see [28] of these reasons) to a finding of sufficiency of objective similarity, as will a finding of attempted obfuscation by a putative infringer of his or her use of the copyright work in bringing the impugned work into existence.

41 If the reference to so dissimilar that the copyright work can no longer be seen in the impugned work simply means (as it seems to me it does so mean) that the requirement of a sufficient degree of objective similarity is satisfied (in circumstances of subjective copying) when the essential features of the copyright work can still be seen in the impugned work (either as a whole or as to a substantial part), I would agree that such a formulation is an accurate statement of the test for reproduction, informed as it is, by subjective copying. If, however, Lindgren J’s formulation of the test (in the circumstances his Honour identifies) assumes an expected starting point of sufficiency of objective similarity unless the impugned work is so dissimilar that there is no element of similarity between the two works, such a test does not accurately reflect, in my view, the proper test and ought not to be adopted for determining whether the Duplex 1 plan bears a sufficient degree of objective similarity to the Dunkeld plan. For one thing, the notion that the copyright work can “be seen” in the contended infringing work or that one can look through the infringing work, like a milky window, and see the copyright work in the contended infringing work, might simply mean that one can see the ideas contained within the copyright work in the infringing work. There is nothing unlawful in using the ideas in one work as the foundation for the expression of one’s own work expressed by reason of the work, skill, effort and judgement of the author of the contended infringing work.

The appeal

42 At this point, it is necessary to say something about the methodological approach adopted by the primary judge to determining infringement.

43 I am satisfied, respectfully, that the primary judge fell into error by adopting an approach characterised by Lindgren J in Eagle Homes v Austec as “artificial” (see [28] of these reasons) of almost entirely separately considering first, whether reproduction of the Tamawood plans in suit had been made out (by reason of whether a sufficient degree of objective similarity was evident as between the relevant plans) and then considering as an entirely independent question whether a causal connection had also been made out.

44 If there is any sequence as such to the inquiry to be made (recognising, however, that no answer to a particular question in the sequence forecloses asking the other questions as each question overlaps with the other) it is probably this. Logically, the first question (in the absence of an admission) is whether initially there appears to be a sufficient degree of resemblance between Tamawood’s plans and those of Mondo. Taking into account the answer to that question, the next question is whether a causal connection has been made out informed by considerations such as Mondo’s opportunity to secure access to and use of Tamawood’s drawings and apparent similarities (particularly an apparent, high degree of objective similarity in the case of floor plans for low cost project homes) coupled with an assessment of any contended explanation of the similarities by the putative infringer: “probative similarity”.

45 The next question, where actual copying is found to have occurred on whatever ground made out, is whether the Mondo plans exhibit a sufficient degree of objective similarity so as to constitute reproduction of the copyright work recognising that a finding of copying can add significance to objective similarity: see [24]-[28] of these reasons as to the overlapping nature of these questions.

46 Thus, it is necessary to consider whether the primary judge’s error as described at [43] of these reasons leads to the result contended for by Tamawood on the appeal.

47 In the appeal, Tamawood says that the findings of the primary judge concerning the Torrington plan are relevant findings of fact bearing upon Mondo’s conduct concerning copying and reproduction of the Dunkeld plan. At [173], the primary judge found “substantive duplication” of the Torrington plan by Mondo’s Duplex 2 and Duplex A drawings (“D2/DA”) and also found that, although there is some variation in the arrangement of the first floor rooms, the drawings have “very similar content”. At [174], the primary judge found a sufficient degree of objective similarity to support a finding of substantial reproduction of the Torrington plan in Mondo’s D2/DA drawings.

48 The primary judge then made observations concerning the question of substantial reproduction of the Dunkeld plan by Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan. I will return to that matter later in these reasons.

49 The primary judge then considered the question of causal connection between Tamawood’s copyright works in suit and Mondo’s conduct so as to form a view about “copying”. The primary judge made the following findings about the Tamawood and Mondo plans in a general sense before turning specifically to the Torrington and Dunkeld plans.

50 At [191], Habitare requested Mondo to prepare drawings for the Calamvale and Brackenridge sites. At [192], those Mondo plans needed to be generally in accordance with the plans the subject of the Brisbane City Council Development Approval for each site. At [193], Mr Sweeney (Mondo) met with Mr Speer and Mr Shane O’Mara (both of Habitare) on 21 June 2006. Mr Sweeney was told that Habitare would not be engaging Tamawood as builder and was asked whether Mondo could prepare construction drawings based on the Development Approval drawings in order to obtain building approvals. At [194], by June 2006, Habitare and Mondo were both concerned about “copyright issues” in Mondo preparing plans for Habitare generally in accordance with Tamawood’s plans the subject of the Development Approvals. At [194], Mr Speer and Mr Shane O’Mara represented to Mr Sweeney that there were no outstanding issues between Habitare and Tamawood concerning use of Tamawood’s plans. At [195], Mondo produced its plans for Habitare for each site with the intention that its plans be generally in accordance with the approved Tamawood drawings, after Mondo had been shown the Tamawood drawings. Thus, at [195], an inference arose that Mondo’s plans were “copied” from the Tamawood plans.

51 As to the Torrington plan specifically, the primary judge made these findings.

52 At [198], Mondo’s D2/DA drawings were the result of copying the Torrington drawings, intentional or otherwise. At [199], “precursor Mondo designs” (that is, Mondo’s precursor plans to its D2/DA drawings) were “significantly different” in “many respects” from the Torrington plan yet Mondo’s D2/DA plans “have very similar content” (at [173]) to the Torrington plan. Moreover at [199], Mondo’s D2/DA plans represent “some departure” from Mondo’s earlier versions of its plans for a two-storey duplex, with “no real explanation given” by Mondo for the changes. At [200], Mondo’s D2/DA plans were created so as to satisfy Habitare’s need for plans “generally in accordance with the Tamawood plans”. At [201], having accepted Habitare’s retainer, Mondo was under “some pressure” to “produce documents” which generally accorded with Tamawood’s plans which had already received Development Approval.

53 The primary judge notes at [201], Mr Speer’s evidence that a new Development Approval process would “take too long” and that the dilemma put by Mr Speer to Mr Sweeney was that new plans were needed substantially in accordance with the existing approvals yet the new plans must not give rise to “copyright problems” with Tamawood. At [203], Mr Keiler (an architect at Mondo) gave evidence that Mondo’s plans would have to fit the “footprint” of the Development Approval. At [204], the “direct similarities” between the Torrington plan and Mondo’s D2/DA plan are “significant”, notwithstanding that “similarities” in plans for project houses “arise out of functional necessity” such that independently-created plans may well bear similar features.

54 As to the authorship of Mondo’s D2/DA design, the primary judge at [204] observes that it is clear from Mr Keiler’s evidence that the D2/DA plan was created by him “shortly after” Tamawood’s brochure drawings were printed by Mondo from the Tamawood website and reviewed by Mr Keiler; Mr Keiler’s work occurred either contemporaneously with or shortly after he received copies of the Development Approvals from Habitare; and his work occurred contemporaneously with his discussions with Habitare personnel in order to discuss Habitare’s requirements.

55 Thus, at [205], the primary judge says this:

While the brief to Mondo was to produce plans “generally in accordance with” the Tamawood plans, this is a circumstance where the objective similarities between the Torrington and Duplex 2/Duplex A designs are sufficiently great, and the prior access by Mondo to Tamawood’s work sufficiently clear, such that the Court should draw the inference of copying: [Pacific Gaming v Aristocrat at 454].

[emphasis added]

56 As to the question of objective similarities between Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s Duplex 1, the primary judge at [182] observes that there are “important differences” between the two “designs”. Six such differences are identified by the primary judge. They are these:

• In the [Dunkeld] the entry opens immediately into a living area. In Duplex 1 the entry opens into a hallway, which allows access to Bedrooms 2 and 3 and the bathroom, and leads to the kitchen.

• In the [Dunkeld], Bedroom 3 is at the back of the dwelling, accessed through the Dining room. In Duplex 1 Bedroom 3 is at the front of the dwelling, abutting the garage.

• In the [Dunkeld], the position of Bedroom 1 (with its ensuite) and Bedroom 2 are reversed compared with the positioning of those rooms in Duplex 1.

• In the [Dunkeld] access to Bedrooms 1 and 2 and the bathroom is from a hallway accessed from the kitchen. In the Duplex 1, access to Bedroom 1 is from the Dining room.

• In the [Dunkeld], the Living and Dining rooms are separated by the Kitchen. In Duplex 1, the Dining and Living rooms are one open space, at the rear of the dwelling.

• In Duplex 1 an outside patio is accessed from the Dining room. No such patio exists on the [Dunkeld] drawings.

57 Having regard to the evidence of Tamawood’s expert, Mr Miller, the primary judge at [184] said this:

In my view, the quality of the differences between the [Dunkeld] and Duplex 1 means that, for all intents and purposes, the designs represent quite dissimilar dwellings.

[emphasis added]

58 At [185], the primary judge said this:

While the overall shape of the duplex building is very similar in all three designs (in particular the Dunkeld and Duplex B):

• The Conondale does not feature an ensuite to Bedroom 1, whereas the Duplex B has that feature.

• The Duplex B features Bedrooms 2 and 3 at the front of the dwelling, unlike the Conondale/Dunkeld.

• Bedroom 1 and the ensuite in Duplex B are at the back of the dwelling, unlike in the Conondale/Dunkeld drawings.

• The Kitchen in Duplex B is not in the middle of the dwelling unlike the Conondale/Dunkeld design, but abutting the common wall, and the Laundry is accessed through the Kitchen.

• The middle of the dwelling in the Duplex B is dominated by a Family/Living space, unlike the Conondale/Dunkeld design.

[emphasis added]

59 Apart from reliance placed by the primary judge upon Mr Miller’s evidence, the primary judge also said this at [186]:

Again, looking at the quality of the plans, in my view they represent significantly different dwellings.

[emphasis added]

60 At [187], the primary judge found in these terms:

Accordingly, not only is there no reproduction in whole of the Conondale/Dunkeld in the Duplex 1 or in Duplex B, but it cannot be said that there is reproduction of a substantial part of those designs.

[emphasis added]

61 The primary judge’s ultimate conclusion at [188] is in these terms:

It follows that in my view Tamawood’s claims involving infringement of its copyright in Conondale/Dunkeld drawings cannot be substantiated.

62 The primary judge then considered, in any event, whether a causal connection had been made out between Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan. As to that, the primary judge said this at [208]:

In the absence of reproduction, I am satisfied that there is no causal connectivity between those Tamawood drawings and the Mondo Duplex 1.

[emphasis added]

63 The primary judge also said this at [209] concerning a drawing produced by Mondo in February 2006 described as Drawing 3 to Exhibit RJS-13 to the affidavit of Mr Sweeney sworn 20 September 2011:

In relation to exhibit RJS13-3 produced by Mondo in February 2006, while in my view there are strong similarities between this design and the Dunkeld, this Mondo plan was not used by Mondo or Habitare as a design “generally in accordance” with the development approval. Duplex 1 was the design so used. I am not persuaded that any inference of relevance should be drawn from the existence of RJS13-3, other than the possibility of this design representing progressive internal experimentation in designs by Mondo including by reference to the work of competitors (but evidently, in relation to this design, not used).

[emphasis added]

64 Tamawood contests the finding of fact of no causal connection to the Dunkeld plan due to the primary judge’s error in the approach to fact finding. Tamawood says these things.

65 First, having regard to the drawings and plans contained in a document described as “Mondo Architects Schedule of Additional Drawing References in the Evidence of Mr Sweeney” (“Schedule of Mondo Drawings”) handed up to the Full Court (with copies to the parties) together with documents described as 12A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J and K (also handed up) based on Exhibits RJS-11, RJS-12 and RJS-13 to Mr Sweeney’s affidavit of 20 September 2011, Tamawood contends that nothing in the work of Mondo prior to the early part of 2006 demonstrates drawings similar to the Dunkeld plan.

66 Second, in February 2006, Mondo produced the drawing in CAD form at RJS13-3. That plan exhibits “strong similarities” to the Dunkeld plan (see [63] of these reasons and the finding at [209] of the primary judge’s reasons).

67 Third, the drawing of February 2006 emerged from Mondo at a time when Habitare was seeking to re-engage with Mondo and at this time Habitare requested Mondo to prepare architectural drawings and cost those drawings.

68 Fourth, the reason Mondo’s February 2006 drawings exhibit, as found, “strong similarities” to the Dunkeld plan (and represent a departure from prior Mondo drawings) is explained by the circumstance that Habitare’s Development Approvals (of 1 March 2006 and 7 July 2006; see [6] and [7] of these reasons) would be based upon Tamawood’s plans and thus other architectural designs, having no approved application to each site and thus no utility for either site, would be of no interest or relevance to Habitare.

69 Fifth, Mr Keiler, for Mondo, played a central role in engaging with Habitare personnel in early 2006 and was largely responsible for creating the February 2006 drawing at RJS13-3 (which is a departure from Mondo’s drawings prior to that time). Tamawood relies upon Mr Keiler’s concessions in cross-examination that his engagement with Habitare involved some “toing and froing” consisting of either sending Habitare designs by email or engaging in face-to-face meetings with Habitare and receiving feedback from Habitare about the ideas presented by Mr Keiler to Habitare.

70 Sixth, Tamawood says that by February 2006 Mondo had produced a drawing that, first, had emerged out of Mr Keiler’s engagement with Habitare as described and, second, represented a significant departure from that which went before within Mondo. Thus, the so-called “toing and froing” between Mr Keiler and Habitare must, it is said, have resulted in the Habitare people examining Mr Keiler’s sketches and designs and telling him the layout of the floor plan they wanted and where the rooms were to go on that floor plan. In doing so, Habitare was, it is said, “working directly” from Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and thus instructing Mr Keiler in the essential features of the Dunkeld plan it wanted to see adopted in the Mondo plans.

71 Seventh, Habitare had good commercial reasons for so instructing Mondo because it knew that each Development Approval was conditioned upon carrying out each development generally in accordance with the approved Tamawood drawings. Getting on with each project was important, it is said, because, as Mr Speer said in his evidence, Habitare had settled the purchase of the development sites and “interest was ticking away, [and] it was costing us a lot of money”: see [202] of the primary judge’s reasons.

72 Eighth, the constraints imposed by the Development Approvals meant that Habitare found it necessary to review and be familiar with Tamawood’s plans; retain the same “footprint” for the duplex homes and ensure that any changes from the Tamawood drawings as might be reflected in the Mondo drawings for each site were small or largely inconsequential.

73 Finally, Tamawood says that the objective similarities between Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s Duplex 1 are such that the Dunkeld plan can be seen embedded in Mondo’s plan (to use the language of Lindgren J) and one can look through Mondo’s plan and see the Dunkeld plan: see [32] of these reasons. Thus, there is said to be a sufficient degree of objective similarity between the two drawings having regard to Habitare’s use of the Tamawood plan by instructing or, in effect, filling up Mondo with the essential features of the Dunkeld plan.

74 Mondo supports the finding of the primary judge at [184] that the floor plans for the Dunkeld and Duplex 1 project homes represent quite dissimilar dwellings and the finding at [186] that looking at the quality of the plans, they represent significantly different dwellings. Mondo also says that by 6 April 2006 it had produced its Duplex 1 plan (see the plan described as “Duplex Single Option 3”, plan at p 17 (also marked p 261), Schedule of Mondo Drawings) well before it ever saw Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan.

75 The case put against Mondo, however, is that by reason of the exchanges (which seem as to real particularity largely content free “toing and froing”) between Mr Keiler and Habitare in the early part of 2006, Mondo produced by February 2006 (although apparently not specifically for the two project sites in issue in the proceedings) a drawing (RJS13-3) which represents a departure from Mondo’s genetic footprint of floor plan designs to that time and one which, as found by the primary judge at [209], bears “strong similarities” to Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan. That plan is at [207] of the primary judge’s reasons.

76 I agree that the plan at [207] represents both a departure from Mondo’s earlier work and that the arrangement of rooms and the “layout and traffic flows and the shapes, proportions and interrelationships of rooms and other spaces – elements which permeate the whole of the project home” (see [37] of these reasons) reflect strong similarities with Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan, as the primary judge found. It also seems very likely that the Mondo plan at RJS13-3 produced in February 2006 (so close to the impending Development Approval for Gawler/Norris Road on 1 March 2006), emerged out of Mondo in circumstances where Habitare personnel were acting in their dealings with Mondo, by reference to the Dunkeld plan which Habitare had before it. It seems that Mr Keiler’s authorship of the plan at RJS13-3 was as a result of Habitare pressing strongly for a plan generally as close as possible to Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan that would be the subject of the upcoming Development Approvals and the blunt reality that undertaking a new Development Approval process would “take too long” and cause additional “interest costs” to run should a new process need to be undertaken. It seems very likely that Mr Speer instructed Mr Keiler in the features and content of RJS13-3 with some real precision drawn from Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan.

77 I thus accept that an inference is open that the explanation for the emergence of CAD drawing RJS13-3 out of Mondo’s office by February 2006 in a form that was strikingly similar to the Dunkeld plan is that Mr Keiler was giving effect to Habitare’s instructions given with precise reference to the Dunkeld plan.

78 Tamawood, however, does not rely upon RJS13-3 as the contended infringing Mondo drawing. It relies upon RJS13-3 so as to demonstrate “copying” based on instructions to Mr Keiler from Habitare.

79 The question then is this: Once it is accepted (by drawing the inference) that Mondo’s February 2006 drawing emerged out of access to and use by Habitare of Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan resulting in precise instructions to Mondo about the essential features of that plan (and thus a causal connection to the Dunkeld plan), does the Mondo plan said to infringe in these proceedings depicted at [17] of these reasons (which is not RJS13-3) reveal a sufficient degree of objective similarity so as to constitute reproduction of Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan recognising the significance copying adds to objective similarity?

80 Just as the drawing at RJS13-3 reveals a departure from Mondo’s earlier drawings, Mondo’s Duplex 1 said to infringe represents a departure from RJS13-3. The primary judge finds at [209] that RJS13-3 was not used by Mondo or Habitare. Mondo made changes to the floor plan to bring about Duplex 1. Is there a sufficient degree of objective similarity between Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan recognising the role Habitare had earlier played in instructing Mondo about the content of the Dunkeld plan so as to produce RJS13-3?

81 The important considerations in answering that question seem to me to be these.

82 First, although the Development Approval for each site required Mondo to retain the “footprint” for the duplex, the layout, traffic flows within the house and the proportions and inter-relationships of rooms and other spaces was not dictated by the footprint.

83 Second, as to the requirement that the Mondo plan be generally in accordance with the approved drawings, it does not seem to be asserted that that condition would necessarily bring about or require use of a drawing in the development on each site that would be characterised as a reproduction in a material form of the Tamawood drawings. There seems to be some latitude or flexibility to use a drawing generally in accordance with the approved drawings. Each drawing, generally, contained a number of elements: three bedrooms (and thus a structure and plan designed to accommodate a number of individuals who would normally populate three residential bedrooms in a low cost project home); an ensuite attached to one of those bedrooms (described as Bedroom 1); a bathroom immediately adjacent to a second bedroom and separated by a wall, immediately next to the ensuite so as to utilise, no doubt, plumbing connections to “wet areas”; two of the bedrooms and wet areas along an external side wall; a toilet; a living room; a dining room; a kitchen; a laundry and a garage.

84 Is a floor plan (other than Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan), which incorporates these general features, one which might properly be described as generally in accordance with the approved plans without necessarily being a reproduction in a material form of the approved plans? No party seems to suggest that a plan generally in accordance with the Development Approval must necessarily be an infringement of the Dunkeld plan. Tamawood contends, however, that Mondo’s particular plan is a reproduction of the Dunkeld plan recognising the two aspects of reproduction: see [28] of these reasons.

85 Third, the Dunkeld plan at [17] of these reasons shows an arrangement of rooms and spaces dictating shapes and traffic flows in the following way. The plan shows a porch entry into a living room. Thus, one immediately enters into a large living space. Across the diagonal space from the entry door, is a “false head” entry to the kitchen sited in the centre point of the house. The kitchen looks onto and serves the dining room. Thus, entry into the house engages the amenity of the living room which leads to the kitchen and across the kitchen space to the dining room. The left side wall of the living room divides off the main bedroom at the front of the house (described as Bedroom 1). That wall continues to the rear of the house dividing the dining room from Bedroom 2. That wall contains a “false head” entry and exit through a space in that wall from the kitchen into an area that provides spatial access to a number of rooms. The possibilities are, to the left, passage past the bathroom and entry through a door into Bedroom 1; passage to the toilet; passage to the bathroom or passage to an entry door to Bedroom 2. The laundry is located to the right of the kitchen behind the garage and is located between the kitchen on one side and the block common wall on the right hand side. To the right of the dining room and behind the laundry space is Bedroom 3. The single garage is represented by the space between the block common wall on the right hand side of the diagram and the living room wall on the left side. The footprint for the duplex has the dimensional characteristics reflected in the drawing at [17]. The dimensions of each room are also set out in the floor plan at [17]. In the Dunkeld, the main bedroom at the front of the house has an ensuite bathroom. Apart from the ensuite bathroom servicing the main bedroom, the plan provides for an entirely separate toilet and a separate bathroom.

86 Fourth, Mondo’s Duplex 1 has a footprint which reflects different dimensions as to the footprint itself and other dimensional differences. For example, Tamawood’s Dunkeld is 11.125 metres wide and 11.460 metres deep. Mondo’s Duplex 1 is 10.800 metres wide and 11.800 metres deep. In the Mondo plan, entry is from a porch through the front door into an entry corridor. The three bedrooms making up the duplex are clustered together in the sense that they are all positioned away from the block common wall where the mirror image duplex sets out the living space for the immediate neighbour. In the Mondo plan, one enters by the entry corridor which has a bedroom to the left and a bedroom to the right. On the right hand front side is Bedroom 3 and on the left hand front side is Bedroom 2. Having entered the dwelling, the passageway continues between Bedrooms 2 and 3 to the end of Bedroom 3 and into the kitchen which is sited in the centre of the dwelling. The kitchen engages with the amenity of a combined dining and living room which in turn provides access and entry to a large patio area immediately adjacent to the dining room. The patio area is a quite substantial space.

87 The amenity of the house involves an L shape cluster of bedrooms and wet areas to the left of the structure along the external wall and the third bedroom at the front of the house. It involves another L shaped cluster of what might be described as the societal amenity of the house of food preparation, cooking, dining, entertaining and living consisting of the kitchen and the combined open space of a living and dining room to the back of the structure inter-relating with a patio and pergola.

88 The traffic flows draw a person down the entry hallway into the bedroom cluster or alternatively into the integrated kitchen, dining, living and patio areas. Access into the wet areas involves a different spatial arrangement to that of the Dunkeld. Rather than moving through a false head entry from what otherwise amounts to the mid-point of the kitchen wall into a space serving access to Bedroom 1, the bathroom, the toilet and Bedroom 2, a person moves from the kitchen into the end of the entry corridor so as to gain access to either the separate bathroom or the separate toilet or Bedroom 2. Access to Bedroom 1 is by a doorway directly into that bedroom from the dining room.

89 For my part, having regard to the layout and traffic flows and the shapes, proportions and inter-relationships of rooms and other spaces being the elements which permeate the whole of Mondo’s Duplex 1 project home, I am not satisfied that there is a sufficient degree of objective similarity between Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan and Mondo’s Duplex 1 plan so as to constitute reproduction of the Dunkeld plan in a material form. Nor am I satisfied that Mondo’s plan reproduces a substantial part of the Dunkeld plan. There is no doubt that both plans show an arrangement of two bedrooms and wet areas in conjunction with one another on the external wall of the duplex (that is, in the plans at [17]) on the left hand external wall of the dwelling. In that sense, both plans reflect the idea of an arrangement of rooms as far away as possible from the common block wall between the two dwellings which share that common block wall. There would be no rational point in the notion of locating Bedrooms 1 and 2 and the wet areas along the common block wall immediately next to Bedrooms 1 and 2 and the wet areas of the mirror image duplex.

90 The idea in each plan is to place the two principal bedrooms and wet areas on the exterior walls of each duplex for the obvious reason. The particular arrangement of those rooms and wet areas is not, however, in the same terms and for my part I do not regard the location and inter-relationship of those bedrooms and wet areas as a reproduction of a substantial part of the Dunkeld plan. In any event, during the course of oral submissions before the Full Court emphasis was placed by Tamawood upon the notion that reproduction had occurred independently of any question of reproduction of a substantial part. Both limbs remained alive recognising, however, the nature of reproduction as discussed at [29] of these reasons.

91 For my part, I would dismiss Tamawood’s appeal from the orders of the primary judge dismissing its claim of copyright infringement of the Dunkeld plan.

The nine issues before the Full Court

Issue One

92 Did the primary judge err in finding that the conduct of Habitare (and those associated with it) and Mondo was not authorised by a licence? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Two

93 Is Tamawood precluded from arguing that an inference of indirect copying by Mondo should be drawn by reason of the pleadings and the way the case was run before the primary judge? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Three

94 If Tamawood is not so precluded, did the primary judge err in finding that Mondo did not infringe the copyright in Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan? The primary judge did not fall into error.

Issue Four

95 Did the primary judge err in finding that Mondo was precluded from arguing that it was an “innocent infringer” within s 115(3) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)? I generally agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Five

96 Did the primary judge err in finding that Mr Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson of Habitare did not authorise Habitare’s infringements of Tamawood’s Torrington and Dunkeld plans? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ as to the Torrington infringement.

Issue Six

97 Did the primary judge err in finding that Mr Peter O’Mara, Mr Johnson and/or Mondo are not liable for additional damages under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Seven

98 Did the primary judge err in finding that the Bloomer parties were “innocent infringers” under s 115(3) of the Copyright Act? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Eight

99 Did the primary judge err in respect of the costs orders made in favour of the Bloomer parties? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

Issue Nine

100 Did the primary judge err in finding Mr Shane O’Mara liable to Mondo for misleading and deceptive conduct? I agree with the observations of Jagot and Murphy JJ.

101 The parties ought to confer and submit within 14 days agreed or proposed competing orders reflecting the position adopted by the majority judges, including submissions with respect to costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and one (101) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Greenwood |

Associate:

Dated: 15 May 2015

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 223 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 Appellant |

AND: | HABITARE DEVELOPMENTS PTY LTD (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) (RECEIVERS AND MANAGERS APPOINTED) ACN 122 935 497 First Respondent BLOOMER CONSTRUCTIONS (QLD) PTY LTD ACN 071 344 100 Second Respondent PETER FREDERICK O'MARA Third Respondent DAVID GAVIN JOHNSON Fourth Respondent WAYNE NORMAN BLOOMER Fifth Respondent MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Sixth Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 235 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 Respondent |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 240 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | SHANE ANDREW O’MARA Appellant |

AND: | TAMAWOOD LIMITED ACN 010 954 499 First Respondent MONDO ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ACN 085 992 990 Second Respondent RAYMOND JOHN MCDONALD SWEENEY Third Respondent |

JUDGES: | GREENWOOD, JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ |

DATE: | 18 MAY 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY VIA VIDEO-LINK TO BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ:

THE ISSUES

102 This matter involves three appeals and four notices of contention between multiple parties arising from orders consequential on two judgments (Tamawood Ltd v Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (No 3) (2013) 101 IPR 225; [2013] FCA 410, referred to below as the principal judgment and Tamawood Ltd v Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (No 6) [2013] FCA 1383, referred to below as the costs judgment).

103 Despite this apparent complexity, there are nine issues which arise for determination. To understand these issues it is necessary to identify the parties and the claims between them.

104 Tamawood Ltd (Tamawood) designs and builds project homes.

105 Habitare Developments Pty Ltd (Habitare), now in liquidation, was a developer of low cost, high density housing. Habitare used other subsidiary companies, in this case Eight March Pty Ltd (as trustee of the Eight March discretionary trust) and First Priority Developments Pty Ltd, to acquire and develop sites. It is unnecessary to distinguish between Habitare and its subsidiary companies for the purposes of this matter and thus all references below are to Habitare despite the fact that the relevant company might have been one of the subsidiaries.

106 Peter O’Mara was a director of Habitare. David Johnson was also a director and the financial officer of Habitare. Mr Johnson was declared bankrupt on 14 July 2014. His trustee in bankruptcy was notified of this matter and advised that he did not intend to appear.

107 Shane O’Mara is Peter O’Mara’s son and worked for Habitare.

108 Peter Speer also worked for Habitare.

109 Mondo Architects Pty Ltd (Mondo) is a firm of architects. Raymond Sweeney is a director of Mondo. Shane Keiler is an employee of Mondo who prepares architectural plans.

110 Bloomer Constructions (Qld) Pty Ltd is a building company. Wayne Bloomer is a director and the principal of this company. Together, they are referred to below as the Bloomer parties.

111 Habitare, through its subsidiaries, owned and wished to develop two sites with low cost housing, one at Hamish Street, Calamvale and the other at Gawler Street/Norris Road Brackenridge. Habitare entered into discussions with Tamawood about designing and building the low cost housing. Tamawood prepared plans including plans for housing known as the Conondale/Dunkeld (referred to below as the Dunkeld), a single storey duplex, and the Torrington, a two storey duplex. With Tamawood’s agreement, Habitare lodged Tamawood’s plans with the Brisbane City Council (the Council) and obtained development approvals for the development of each site based on those plans. Habitare did not use Tamawood to construct the buildings on either site. It approached Mondo to prepare construction plans. The conditions of the development approvals required, amongst other things, the buildings to be constructed “generally in accordance with” the Tamawood plans. Mondo prepared plans for the two sites to enable building certificates to be obtained. Building certificates were obtained based on the Mondo plans. Habitare, after its initial builder went into liquidation, engaged the Bloomer parties to complete the construction of the buildings on each site. The Bloomer parties did so.

112 Insofar as now relevant, Tamawood claimed that Mondo’s plans infringed copyright in Tamawood’s plans for the Dunkeld and the Torrington houses. Tamawood sued Habitare, Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson of Habitare, Mondo, and the Bloomer parties in respect of the alleged infringements of copyright under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the Copyright Act). Mondo sued Habitare, Mr Speer and Shane O’Mara for misleading and deceptive conduct under the (then in force) Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth).

113 The primary judge found for Tamawood against Habitare and Mondo but only in respect of the Torrington plan, not the Dunkeld plan. In so doing, the primary judge rejected an argument by Habitare and parties associated with it, including Shane O’Mara, that Tamawood had authorised Habitare’s acts under a contractual licence, and another argument by Mondo that Tamawood had authorised Habitare’s and thus Mondo’s acts under a non-contractual licence.

114 The primary judge rejected Tamawood’s claims against Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson for authorisation of Habitare’s infringement of Tamawood’s copyright in the Torrington plan.

115 The primary judge rejected Tamawood’s claim that it was entitled to orders against Habitare, Peter O’Mara and Mr Johnson and Mondo for additional damages under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act.

116 The primary judge found the Bloomer parties to be “innocent infringers” under s 115(3) of the Copyright Act but concluded that Mondo was not entitled to argue that it was also an “innocent infringer”. Her Honour ordered Tamawood to pay the costs of the Bloomer parties including costs on an indemnity basis from 2 September 2011 onwards, the date on which a letter offering to settle the proceedings had been sent by the solicitor for the Bloomer parties to the solicitor for Tamawood.

117 The primary judge found Habitare liable to Mondo for misleading and deceptive conduct and that Mr Speer and Shane O’Mara were “knowingly concerned” in Habitare’s conduct and thus also liable to Mondo in this regard.

118 The issues that arise on the appeals and the notices of contention, against this background, may be summarised as follows:

(1) Did the primary judge err in finding that the conduct of Habitare (and those associated with it) and Mondo was not authorised by a licence?

(2) Is Tamawood precluded from arguing that an inference of indirect copying by Mondo should be drawn by reason of the pleadings and the way the case was run before the primary judge?

(3) If Tamawood is not so precluded, did the primary judge err in finding that Mondo did not infringe copyright in Tamawood’s Dunkeld plan?

(4) Did the primary judge err in finding that Mondo was precluded from arguing that it was an “innocent infringer” within s 115(3) of the Copyright Act?

(5) Did the primary judge err in finding that Peter O'Mara and Mr Johnson of Habitare did not authorise Habitare’s infringements of Tamawood’s Torrington and Dunkeld plans?

(6) Did the primary judge err in finding that Peter O’Mara, Mr Johnson and/or Mondo are not liable for additional damages under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act?

(7) Did the primary judge err in finding that the Bloomer parties were “innocent infringers” under s 115(3) of the Copyright Act?

(8) Did the primary judge err in respect of the costs orders made in favour of the Bloomer parties?

(9) Did the primary judge err in finding Shane O’Mara liable to Mondo for misleading and deceptive conduct?

119 It is convenient to deal with the primary judge’s reasons by reference to each of the nine issues set out above, given that her Honour was dealing with a much broader dispute between the parties.

ISSUE 1 – THE LICENCE

Primary judge’s reasons

120 The primary judge dealt with the licence issue at [95] to [150] of the principal judgment. The primary judge concluded that Tamawood had granted to Habitare a licence (albeit a bare rather than a contractual licence) authorising Habitare to use the Tamawood plans “in the application to the Brisbane City Council for development approval” (at [147]). However, “once Habitare resolved that it would not engage Tamawood to build those dwellings and took steps to engage someone else, Habitare was no longer entitled to use the” Tamawood plans (at [149]). The primary judge also noted that if the licence was contractual, contrary to the conclusion she had reached, then in any event the contractual licence would have been “subject to a similar term” (at [150]).

121 In reaching these conclusions the primary judge observed that there was little evidence about the dealings between Tamawood and Habitare. She relied, in particular, on the following evidence:

A conversation between representatives of Tamawood and Habitare in which Habitare’s representatives said Habitare wanted Tamawood to build the duplexes on the Calamvale and Brackenridge sites using plans of Tamawood in which the Tamawood representative said “[w]e are happy to form a relationship where we will invest our drafting time and our money on the understanding that we be appointed as the builders and we will then work together” and the Habitare representative said Habitare was happy and Tamawood should “go ahead and prepare the plans for the two projects” (at [102]).

Subsequent discussions between representatives of Tamawood and Habitare in which it was said that Tamawood would be appointed the builder for the development of the two sites (at [103]).

Tamawood’s business model, in which Tamawood builds houses in accordance with its plans (at [104]).

The fact that when Habitare realised it could not resolve outstanding issues relating to Tamawood being appointed the builder (Tamawood having already given Habitare the plans to use for the development application), Habitare then “went elsewhere to get new plans done” (at [110]).

The fact that Habitare and Tamawood “took it for granted” that Tamawood would be appointed the builder for the projects, that being understood by “all parties” (at [112]).

The fact that despite numerous meetings between Habitare and Tamawood the relationship came to an end because three issues could not be resolved, being whether there should be separate contracts for each building or a single contract for each project, whether Tamawood should be paid progressively or on a lump sum basis, and the timing for completion of the building works (at [113]).

Shane O’Mara’s submissions

122 Shane O’Mara emphasised the following evidence in support of his contention that there was a contractual rather than a bare licence:

…Mr Souter-Robertson [Tamawood] told Mr Speer [Habitare]:

We are happy to form a relationship where we invest our drafting time and our money on the understanding that we be appointed as the builders and we will then work together.

Mr Speer said:

“I am more than happy with that. So go ahead and prepare the plans for the two projects.”

Mr Souter-Robertson gave evidence that:

In the same meaning Shane said words to the effect:

How much is it going to cost to get these plans from you so that we can pass them to our own town planner who is going to do the application to the Council. Our town planner will be Harvey Property Consultants.

I said words to the effect:

We know Harvey Property Consultants. We don’t charge for you using our plans to get the development approval from Council as long as we build the duplexes as soon as the plans are approved and the civil works are underway.

Shane said:

Of course Tamawood will be the builder.

Mr Mizikovsky [Tamawood] gave the following evidence:

… This then lead to the second issue namely the question of what would happen if Habitare got the building approvals and then Tamawood decided to increase its prices. I was asked by either Peter Speers [sic] or Peter O’Mara in words to the effect

‘What happens if we get the building approvals and then Tamawood decides to increase prices’.

I replied in words to the effect: “The prices for Tamawood designs are all electronically updated and continuously displayed on Tamawood’s website and therefore the margins that Habitare will be paying will remain constant and any price changes will be in common with the remainder of the industry.

…

I can also recall another similar conversation in relation to the second issue with Peter [sic] Speers [sic] and Peter O’Mara in which I said words to the effect ‘you can use our plans because the price is always available on our website’.

123 As it was put for Shane O’Mara, after these discussions Tamawood handed over its plans and Habitare used those plans to obtain the development approvals.

124 According to the submissions for Shane O’Mara:

From those interactions, the following points of agreement may be identified:

(a) Tamawood would provide drawings to Habitare “on the understanding [sic] that [Tamawood] would be appointed builders”;

(b) Tamawood would not charge for provision of the drawings;

(c) Tamawood would be appointed builder;

(d) the price to be charged for each dwelling would be whatever Tamawood generally charged for such a construction at the time that construction commenced.

125 Further, whether or not the licence was contractual or bare, the term implied by the primary judge (that the licence would automatically terminate on Habitare deciding not to appoint Tamawood the builder), it was submitted, failed to satisfy any of the five criteria for the implication of a term (obviousness, clarity, fairness, necessity, and consistency with express terms, see BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings (1977) 180 CLR 266 at 283). Accordingly, it was contended that:

The term is unnecessary because the parties agreed on an exchange of rights: Tamawood would provide the drawings, and receive the right to be engaged when building commenced in return. The term to be implied suggests a right on the part of Habitare unilaterally to refuse to appoint Tamawood as builders, having exploited the valuable opportunity the drawings provided to obtain the development approval. It would be difficult to draw this from the interactions described above. In the absence of any such right on the part of Habitare, what was the need for the suggested implied term? Tamawood would have had a remedy in damages for breach of contract.