FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2015] FCAFC 50

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

First Appellant SPEEDY DEVELOPMENT GROUP PTY LTD Second Appellant | |

AND: | AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Appeal dismissed with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 149 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED Appellant |

AND: | LUCIO ROBERT PACIOCCO First Respondent SPEEDY DEVELOPMENT GROUP PTY LTD Second Respondent |

JUDGES: | ALLSOP CJ, BESANKO J and MIDDLETON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 april 2015 |

WHERE MADE: | sydney (heard in MELBOURNE) |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Appeal allowed.

2. Declarations 1 and 2, and order 3 made by the Court on 13 February 2014 be set aside.

3. Order 6 made by the Court on 13 February 2014 be set aside, and in lieu thereof it be ordered that, for the purpose of s 33ZB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), orders 4 and 5 made by the Court on 13 February 2014 bind the parties and group members, other than those who opted out of the proceeding.

4. The order of the Court made on 19 March 2014 be set aside, and in lieu thereof it be ordered that the applicants pay the respondent's costs of the proceeding at first instance (other than costs, if any, specifically ordered in interlocutory proceedings), subject to any variation that may be made pursuant to application by Mr Paciocco and Speedy Development Group for such variation to be file and served together with any supporting material on or before 4 pm Monday 13 April 2015.

5. The respondents pay the appellant's costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 141 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | LUCIO ROBERT PACIOCCO First Appellant SPEEDY DEVELOPMENT GROUP PTY LTD Second Appellant | |

AND: | AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED Respondent | |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | ||

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | ||

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 149 of 2014 | |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED Appellant |

AND: | LUCIO ROBERT PACIOCCO First Respondent SPEEDY DEVELOPMENT GROUP PTY LTD Second Respondent |

JUDGES: | ALLSOP CJ, BESANKO J and middleton j |

DATE: | 8 april 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY (HEARD IN MELBOURNE) |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ALLSOP CJ

1 These are two appeals from orders of the Court made on 13 February and 19 March 2014 consequent upon reasons delivered by the primary judge (Gordon J) on 5 February 2014, following a five day hearing in December 2013. (See Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2014] FCA 35.)

2 Though I have reached a different conclusion to the primary judge on a number of matters in the Australia New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) appeal (VID 149 of 2014), I wish to pay tribute to the meticulous detail and clarity that mark her Honour's reasons in respect of a large and factually and legally complex commercial case.

3 The organisation of these reasons is as follows:

The nature of the proceeding

4 The proceeding brought by Mr Lucio Paciocco and a company controlled by him, Speedy Development Group Pty Ltd (SDG), was a representative proceeding under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) in which they sought to set aside bank fees charged by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) on various bases. The fees were referred to in the primary judgment as Exception Fees; and the contractual provisions justifying them were referred to as Exception Fee Provisions.

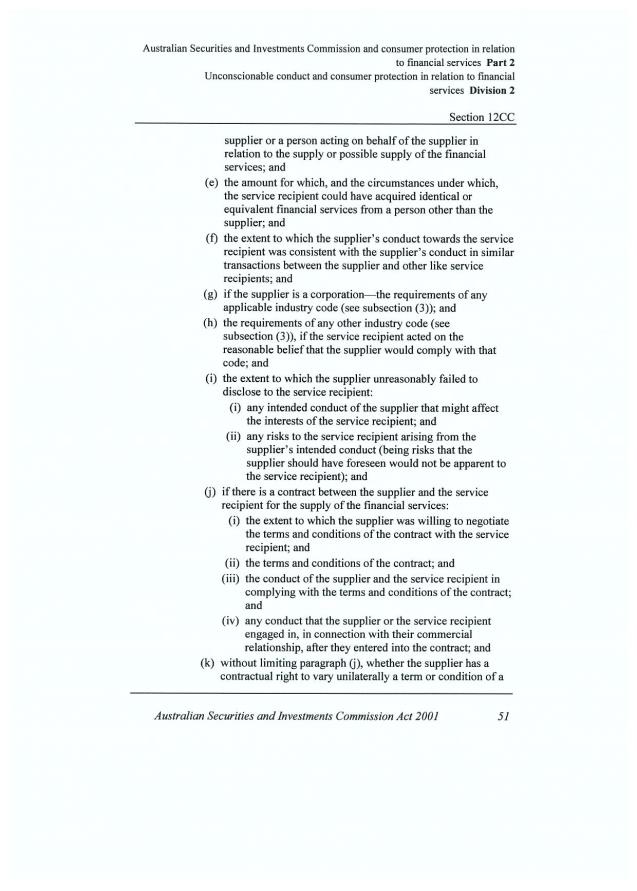

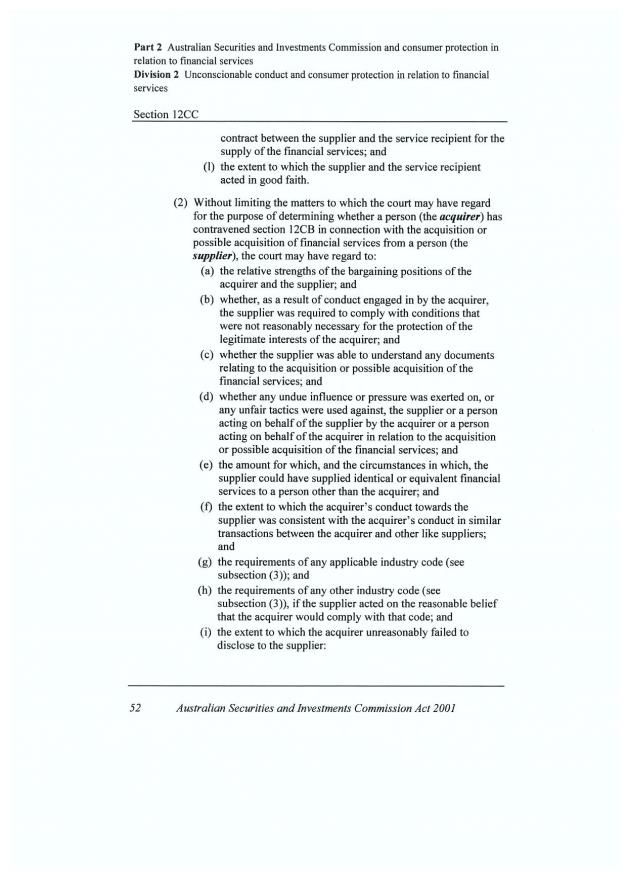

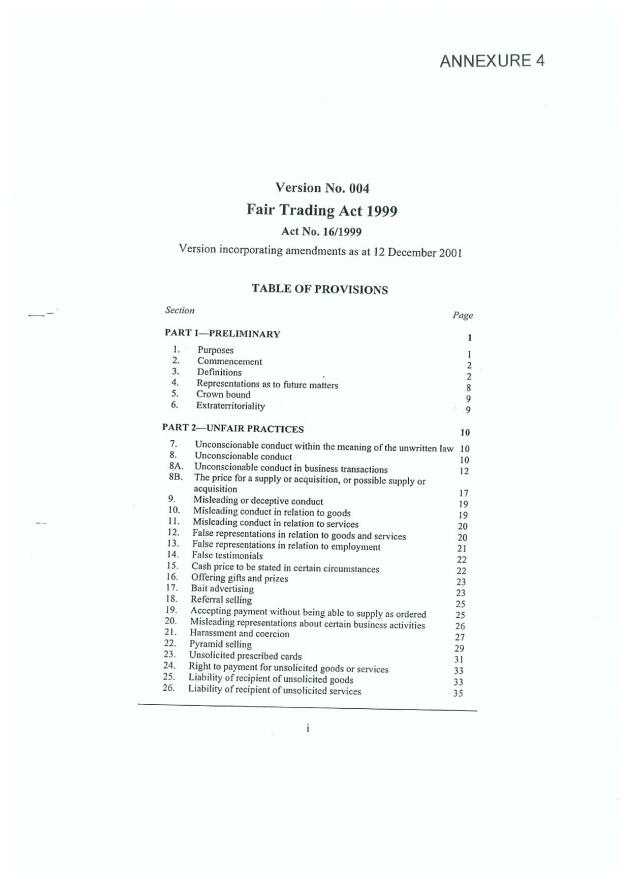

5 The attack on the fees was made on the basis that they were either penalties at common law or equity; or were the product of unconscionable conduct by ANZ within the meaning of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act), ss 12CB and 12CC, or the Fair Trading Act 1999 (Vic) (the FT Act), ss 8 and 8A; or were unjust under the National Credit Code in Schedule 1 to the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth); or as unfair contract terms under the FT Act, s 32W and the ASIC Act, s 12BG.

6 For the following reasons ANZ's appeal should be allowed and that of Mr Paciocco and SDG dismissed.

7 It is appropriate to say at the outset that the case was run by Mr Paciocco and SDG, both below and on appeal, for the benefit not only of themselves but also of those in the group. No aspect of the penalties case was limited to them as applicants. In relation to the statutory claims, some aspects of facts attended the consideration of Mr Paciocco's claims, but he propounded those claims on his own behalf, as well as on behalf of the group.

The accounts and fees in question

8 The proceeding concerned three accounts held by Mr Paciocco – a consumer deposit account and two consumer credit card accounts, and one account held by SDG – a business deposit account. Using abbreviations to maintain the privacy of Mr Paciocco and SDG, the accounts were as follows and as referred to by the primary judge:

(1) Mr Paciocco's consumer deposit account being an Access Advantage Account, called Savings Account 156;

(2) Mr Paciocco's first consumer credit card account being a Low Rate MasterCard account, called Card Account 9522;

(3) Mr Paciocco's second consumer credit card account being another Low Rate MasterCard account, called Card Account 9629; and

(4) SDG's business deposit account being a Business Classic Account, called Business Account 58555.

9 Savings Account 156 was opened in June 1997 and from June 2009 had an overdraft facility with a limit of $500.

10 Card Account 9522 was opened in June 2006 with a credit limit of $15,000 that was increased to $18,000 in November 2009.

11 Card Account 9629 was opened in July 2009 with a credit limit of $4,000.

12 Business Account 58555 was opened in December 2008 and from April 2011 had an overdraft of $10,000 that was increased to $49,999 in November 2011.

13 The fees that were charged were of five kinds. For Mr Paciocco's accounts, they were honour fees, dishonour fees, non-payment fees, late payment fees and overlimit fees; and for SDG's account, they were honour fees, dishonour fees and non-payment fees. The terms of these fees were not in dispute and will be described later. The primary judge found the late payment fees to be penalties and the balance of the fees not to be penalties; and her Honour found that none of the statutory provisions applied to impugn ANZ's conduct or the fees.

14 The trial was limited to a determination of the claims in relation to the fees: (a) in the case of Savings Accounts, from May 2004 to 14 December 2009; (b) in the case of Card Accounts, after March 2004; and (c) in the case of Business Accounts, after August 2004. To the extent that the period after December 2009 was relevant (for Card Accounts and Business Accounts) the relevant terms were different before and after December 2009.

15 Before December 2009, the following were the contractual terms of the fees:

(a) Late Payment Fee: the terms of Card Account 9522 were set out in [53]-[57] of her Honour's reasons, as follows:

53 The relevant contractual documents comprised a Letter of Offer dated 16 June 2006 (para 4 of Annexure 2), 'ANZ Credit Card Conditions of Use' dated September 2006 (para 5 of Annexure 2) (September 2006 Conditions of Use) and 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' dated August 2006 (August 2006 Fees and Charges Booklet) (para 6 of Annexure 2).

54 The Letter of Offer dated 16 June 2006, under the heading "Minimum Repayment", stated:

Each month you are required to pay [the amount] by the Due Date shown on [the] statement of account.

55 The September 2006 Conditions of Use similarly stated:

The account holder must make the 'Minimum Monthly Payment' shown on each statement of account by the 'DUE DATE' shown on that statement of account.

56 Under the heading "Credit Fees and Charges", the Letter of Offer went on to state:

Late Payment Fee: A fee of $35 will be charged to your credit card account if the "Monthly Payment" plus any "Amount Due Immediately" shown on the statement of account is not paid within 28 days of the end of the "Statement Period" shown on that statement.

57 The Late Payment Fee was imposed by the August 2006 Fees and Charges Booklet:

Late Payment Fee $35

Charged to ANZ Low Rate MasterCard … if the "Monthly Payment" plus any "Amount Due Immediately" shown on the statement of account is not paid within 28 days of the end of the "Statement Period" shown on that statement.

Thus, the fee was charged 28 days from the end of the Statement Period if the minimum monthly repayment was not made by that date. The terms and conditions required that the minimum monthly payment be paid by the Due Date, which was 14 or 25 days from the end of the Statement Period. Thus there was a 14 day or 3 day period between the Due Date and the date on which a fee was charged if payment was not made – in effect, a grace period of 14 or 3 days.

(b) Overlimit Fee: the terms of Card Account 9629 and Card Account 9522 were set out in [59]-[62] of the reasons, as follows:

59 For the Overlimit Fee on Card Account 9629 and the Overlimit Fee on Card Account 9522, the contractual documents comprised:

1. in relation to the Exception Fee on 12 August 2009 on Card Account 9629 (Exception Fee 12), a Letter of Offer dated 24 July 2009 (para 7 of Annexure 2); and

2. in relation to the Exception Fee on 6 September 2009 on Card Account 9522 (Exception Fee 13), the Letter of Offer dated 16 June 2006 (para 4 of Annexure 2);

3. in relation to both Exception Fees:

(a) 'ANZ Credit Cards Conditions of Use' dated July 2009 (July 2009 Conditions of Use) (para 8 of Annexure 2); and

(b) 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' dated July 2009 (July 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet) (para 9 of Annexure 2).

60 The July 2009 Conditions of Use stated in cl 2:

The Credit Limit

(a) Your credit limit is set out in the Letter of Offer and is for the credit card account. If ANZ issues more than one credit card for use on your credit card account no separate limit applies for each credit card. The account holder can ask ANZ to increase or decrease the credit limit at any time. ANZ is not required to agree to any request to increase the credit limit. ANZ is not required to agree to any request to decrease the credit limit if the decrease would result in the outstanding balance exceeding the credit limit.

(b) You must not exceed the credit limit unless ANZ has consented in writing or ANZ otherwise authorises the transaction which results in the account holder's outstanding balance exceeding the credit limit. By authorising a transaction which results in the account holder's outstanding balance exceeding the credit limit, ANZ is not increasing the account holder's credit limit. If you exceed your credit limit, you must pay the amount by which the outstanding balance exceeds the credit limit immediately.

(c) Any withdrawal, transfer or payment from the credit card account will be made firstly from any positive (Cr) balance and secondly from any available credit in the credit card account.

(Emphasis added.)

61 Both Letters of Offer, under the heading "Credit Fees and Charges", stated:

Overlimit Fee: A fee of $35 will be charged to your credit card account at the end of the "Statement Period" shown on the statement of account if the balance of the account exceeds the "Credit Limit" during that statement period. Charged at a maximum of once per statement period.

[Note that the Letter of Offer dated 24 July 2009 stated that "A fee of $35* will be charged…" and "… account exceeds the "Credit Limit"# during that statement period…". Neither party contended that the matters referred to in the "*" or "#" had any substantive relevance to this case.]

62 The July 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet imposed the fee:

Overlimit Fee $35

• Charged at the end of the "Statement Period" shown on the statement of account if the balance of the account exceeds the "Credit Limit" during that statement period …

• Charged at a maximum of once per "Statement Period"

Thus, the fee was charged at the end of the Statement Period if the account balance exceeded the Credit Limit at any time during the Statement Period. It was charged once irrespective of the number of transactions that brought about the exceeding of the limit. The terms and conditions provided that a customer must not overdraw the account unless ANZ has consented in writing or otherwise authorises the transaction.

(c) Honour Fee: the terms of Savings Account 156 were set out in [63] and [65]-[66] of the reasons, as follows:

63 Mr Paciocco was charged three Exception Fees on Saving Account 156 – a Saving Honour Fee on 15 September 2008 (Exception Fee 1), a Non-Payment Fee on 26 September 2008 (Exception Fee 2) and a Non-Payment Fee on 27 January 2009 (Exception Fee 3). All three Exception Fees were charged pursuant to the same contractual documents: A Signature Card for opening Saving Account 156 dated 10 June 1997 (para 1 of Annexure 2), 'ANZ Saving & Transaction Products – Terms and Conditions dated August 2008' (August 2008 Terms and Conditions) (para 2 of Annexure 2) and 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' dated August 2008 (August 2008 Fees and Charges Booklet) (para 3 of Annexure 2).

…

65 Clause 2.12 of the August 2008 Terms and Conditions for Saving Account 156 provided:

Provision of Credit

ANZ does not agree to provide any credit in respect of your account without prior written agreement. Depending on your account type, credit can be provided through an ANZ Equity Manager facility, an Overdraft facility or an ANZ Assured facility. It is a condition of all ANZ accounts that you must not overdraw your account without prior arrangements being made and agreed with ANZ.

…

If a debit would overdraw your account, ANZ may, in its discretion, allow the debit on the following terms:

• interest will be charged on the overdrawn amount at the ANZ Retail Index Rate plus a margin (refer to 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' booklet for details);

• an Honour Fee may be charged for ANZ agreeing to honour the transaction which resulted in the overdrawn amount (refer to 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' booklet for details);

• the overdrawn amount, any interest on that amount and the Honour Fee will be debited to your account; and

• you must repay the overdrawn amount and pay any accrued interest on that amount and the Honour Fee within seven days of the overdrawn amount being debited to your account.

…

(Emphasis added.)

66 The imposition of the Honour Fee was also addressed in the August 2008 Fees and Charges Booklet:

Honour Fee

• Payable on each occasion that ANZ honours a drawing where sufficient cleared funds are not available in the account or when the credit limit on your account is exceeded. $35

…

The Honour Fee is payable on the date of the excess and drawings include those made at a branch, by cheque, or electronic banking. Electronic banking includes Internet, Phone, EFTPOS, Periodical Payments, Direct Debits and ATMs.

The fee was charged once per day, irrespective of the number of transactions where ANZ honoured a drawing when insufficient cleared funds were available or a credit limit was exceeded.

(d) Non-Payment or Dishonour Fee: the terms of Savings Account 156 were set out in [67]-[68] of the reasons:

67 Clause 2.7 of the August 2008 Terms and Conditions provided:

A Periodical Payment Non-Payment Fee is charged if you have authorised a Periodical Payment that is not made because there are insufficient cleared funds in your account.

68 The imposition of the Non-Payment Fee was also addressed in the August 2008 Fees and Charges Booklet. For "Periodical Payments", it stated that the "Non-payment fee" was $35.

16 After December 2009, the following were the contractual terms of the fees:

(a) Late Payment Fee: the terms of Card Account 9629 – were set out in [72]-[75] of the reasons as follows:

72 For the Late Payment Fee on 12 January 2010 on Card Account 9629 (Exception Fee 14), the contractual documents comprised the Letter of Offer dated 24 July 2009 (para 10 of Annexure 2), 'ANZ Credit Cards Conditions of Use' dated December 2009 (December 2009 Conditions of Use) (para 11 of Annexure 2) and 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' dated December 2009 (December 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet) (para 12 of Annexure 2).

73 The 24 July 2009 Letter of Offer, under the heading "Credit Fees and Charges", stated:

Late Payment Fee

A fee of $35* will be charged to your credit card account if the "Monthly Payment" plus any "Amount Due Immediately" shown on the statement of account is not paid within 28 days of the end of the "Statement Period" shown on that statement.

[Note that the material referred to in the asterisk had no substantive relevance to this case.]

74 The fee level was set in the December 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet:

Late Payment Fee $20

• Charged to your credit card account if the "Minimum Monthly Payment" plus any amount "Payable Immediately" shown on the statement of account is not paid by the "Due Date" shown on that statement.

75 The other Late Payment Fees charged on the Card Accounts after December 2009 were charged pursuant to different contractual documents. There is no dispute that the terms in those documents were not materially or substantively different from those applicable to Exception Fee 14.

Thus, the Late Payment Fees on the card accounts after December 2009 were substantially the same. The fee was charged if the minimum monthly payment plus any amount payable immediately was not paid by the Due Date.

(b) Overlimit Fee: the Terms of these fees in the Card Accounts were various and set out at [76]-[81] of the reasons, as follows:

76 For the Overlimit Fee charged on 12 May 2010 on Card Account 9629 (Exception Fee 15), the contractual documents comprised the Letter of Offer dated 24 July 2009 (para 10 of Annexure 2), 'ANZ Credit Cards Conditions of Use' dated March 2010 (March 2010 Conditions of Use) (para 13 of Annexure 2) and the December 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet (para 12 of Annexure 2).

77 Clause 2 of the March 2010 Conditions of Use stated:

The Credit Limit

(a) Your credit limit is set out in the Letter of Offer and is for the credit card account. If ANZ issues more than one credit card for use on your credit card account no separate limit applies for each credit card. The account holder can ask ANZ to increase or decrease the credit limit at any time. ANZ is not required to agree to any request to increase the credit limit. ANZ is not required to agree to any request to decrease the credit limit if the decrease would result in the outstanding balance exceeding the credit limit.

(b) From time to time, there may be a debit made to your credit card account which, if processed, would temporarily result in the outstanding balance exceeding your credit limit. ANZ has an Informal Overlimit service to help you in these circumstances.

(c) When a debit is initiated which, if processed, would result in the outstanding balance temporarily exceeding your credit limit, you make a request for an Informal Overlimit amount. ANZ will consider your request for an Informal Overlimit amount and, if both the debit and the account holder satisfy ANZ's credit criteria for Informal Overlimit amounts, ANZ will allow the debit to be processed as an Informal Overlimit amount, on the following terms:

• interest will be charged on the Informal Overlimit amount at the applicable interest rate for purchases, cash advances and other payments (see Condition (19));

• an Overlimit Fee will be charged (refer to the Letter of Offer for details);

• the Informal Overlimit amount, any interest on that amount and any Overlimit Fees will be debited to your credit card account; and

• you must repay the Informal Overlimit amount on the earlier of:

- the time shown for payment of 'Overdue/Overlimit' amount on the next statement of account after the Informal Overlimit amount is debited to your credit card account; and

- the day that is 60 days after the day on which the Informal Overlimit amount is debited to your credit card account.

(d) By processing a debit as an Informal Overlimit amount, ANZ is not increasing the account holder's credit limit.

(e) Any withdrawal, transfer or payment from the credit card account will be made firstly from any positive (Cr) balance and secondly from any available credit in the credit card account. An Informal Overlimit amount will only be provided if there is no available credit in the credit card account and both the debit and the account holder satisfy ANZ's criteria for Informal Overlimit amounts.

(f) If you want to avoid exceeding your credit limit, you should ask ANZ:

- how to have ANZ decline transactions you initiate that will take you over your credit limit – please note that this service is not available for all transaction types (for example, it is not available for a transaction that is not electronically authorised such as a purchase that is manually debited to your credit card account if EFTPOS is not available). Please ask for our Overlimit Credit Card Opt Out Form;

- about ways in which you can monitor the balance of your credit card account; or

- if you have longer-term, ongoing borrowing needs, how to apply for an increase to the account holder's credit limit or for information about other products that may suit your needs.

(Emphasis added.)

78 The 'ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges' dated November 2011 (November 2011 Fees and Charges Booklet) set the fee for Overlimit Fees 19-22 and 24-26. There was no dispute that the relevant Exception Fee Provisions in the December 2009 Fees and Charges Booklet and the November 2011 Fees and Charges Booklet were not materially or substantively different. They provided:

Overlimit Fee $20

• Charged to your credit card account at the end of the "Statement Period" shown on the statement of account if we agree to provide an Informal Overlimit amount during that statement period. The Overlimit Fee is charged at a maximum of once per statement period.

79 The other Overlimit Fees charged on the Card Accounts in this period were charged pursuant to different contractual documents. Some of the provisions were redrafted. In the 'ANZ Credit Cards Conditions of Use' dated June 2010 (para 14 of Annexure 2) (and in all subsequent versions) a preamble was added to the document under the heading "Important things to know about using your ANZ credit card", which included the following:

Fees

We tell you which fees can apply to your credit card account in the Letter of Offer that we sent to you, and you can also find these in the ANZ Personal Banking Account Fees and Charges booklet which is available on anz.com or at any ANZ branch.

Some of the key fees you need to know are below:

…

Fees that apply when you do something, or request us to do something for you

We provide you with services on your credit card account and sometimes there are fees for doing so. The most common service fees are:

…

• Late Payment Fee

• Overlimit Fee (not applicable to ANZ Visa PAYCARD and ANZ Rewards Visa PAYCARD accounts, or if you hold an ANZ Access Basic Account)

You can avoid some of these fees:

You can avoid a Late Payment Fee by paying the Minimum Monthly Payment shown on your statement by the due date

• We have convenient services available to you that make it easy to make your minimum payment on time such as CardPay Direct – please ask us for details.

You can avoid an Overlimit Fee by staying within your approved credit limit

• We tell you what your credit limit is on your Letter of Offer that we sent you, and it's also shown on your monthly account statement

• Sometimes you might have a transaction that temporarily causes you to exceed your credit limit. In this situation, we want to help you avoid embarrassing moments such as being declined while purchasing your groceries. Where you and the transaction which would exceed your credit limit satisfy our criteria, we will provide you with a convenient service to cover your payment needs – we call this service an Informal Overlimit facility. An Overlimit Fee will be charged for this service.

• You can also ask us to decline certain transactions so that you don't exceed your credit limit. Please see clause 2 in this booklet for further information.

80 For some of the Overlimit Fees (Exception Fees 29, 30, 32, 33 and 35), the Fees and Charges Booklet was amended with effect from June 2012 (para 15 of Annexure 2) as follows:

Overlimit Fee $20

A. Charged to your credit card account at the end of the "Statement Period" shown on the statement of account where:

• any type of debit is initiated on your credit card account that would cause you to exceed your credit limit during the Statement Period; and

• we agree to provide you with an Informal Overlimit amount to allow this debit to be charged to your credit card account.

81 For Exception Fees 39, 40, 43 and 44, the Fees and Charges Booklet was amended with effect from March 2013 and for the balance of the Overlimit Fees (Exception Fees 48 and 50), the Fees and Charges Booklet was amended with effect from July 2013. No party suggested that there was any material or substantive difference between the documents.

In substance, in December 2009, the terms and conditions were redrafted so that it was clearly stated that the initiation of a debit which would take the account outside its limits was a request for an informal overdraft to be considered by the ANZ; there was no express obligation that the customer must not overdraw the account.

(c) Honour Fees: the terms of Business Account 58555 were set out at [83]-[88] of the reasons, as follows:

83 For the Business Honour Fees charged on 4 March 2010 and 9 July 2010 (Exception Fees 51 and 52), the contractual documents comprised a Signature Card regarding the opening of Business Account 58555 dated 15 December 2008 (para 16 of Annexure 2), a Company/Formal Trust Account Authority for the account dated 15 December 2008 (para 17 of Annexure 2), 'Business Transaction Accounts Terms and Conditions – ANZ Business Banking' dated December 2009 (December 2009 Terms and Conditions) (para 18 of Annexure 2) and 'Transaction Accounts Fees and Charges – ANZ Business Banking' dated December 2009 (December 2009 Business Fees and Charges Booklet) (para 19 of Annexure 2).

84 One of the applicable provisions in the December 2009 Business Terms and Conditions provided:

If you satisfy ANZ's credit criteria for an Informal Overdraft facility, ANZ will agree to your request by allowing the debit to be processed as an Informal Overdraft, on the following terms:

• If the balance of your Informal Overdraft facility exceeds $50 at the time of your request, or will exceed $50 once the debit requested is processed, you will be charged an Informal Overdraft Assessment Fee on the day on which the debit is processed (or if that day is not a business day, on the next business day). The Informal Overdraft Assessment Fee (referred to in your bank statements and in the 'ANZ Business Banking Transaction Accounts Fees and Charges' booklet as an 'Honour Fee') is payable immediately.

85 The Honour Fee was set by the December 2009 Business Fees and Charges Booklet as follows:

Honour Fee $37.70

Charged for considering a request for an Informal Overdraft where you satisfy ANZ's credit criteria for an Informal Overdraft, and the balance of your Informal Overdraft facility exceeds $50 at the time of your request or will exceed $50 after the debit requested has been processed.

(b) Other Honour Fees (Exception Fees 53-61 and 72)

86 For Exception Fees 53-61 and 72, the contractual documents comprised the documents at [83] above (or materially and substantively the same documents) as well as 'Finance Conditions of Use – ANZ Business Banking' dated August 2011 (para 22 of Annexure 2) (or a later version which was materially and substantively the same) and 'Finance Fees and Charges – ANZ Business Banking' dated December 2009 (or a later version which was materially and substantively the same).

87 For Exception Fees 53 and 54, the applicable provisions included the two provisions extracted at [84]-[85] above as well as the terms of an Overdraft Facility Letter of Offer for $10,000 dated 28 April 2011 (para 20 of Annexure 2) which stated:

A fee is charged if the balance of your Overdraft facility exceeds $50 or will exceed $50 after a requested debit has been processed. This fee is for considering a request for an Informal Overdraft where you satisfy ANZ's credit criteria.

88 For Exception Fees 55-61 and 72, the applicable provisions again included the two provisions extracted at [84]-[85] above. The Overdraft increased to $49,999 pursuant to an Overdraft Facility Letter of Offer dated 29 November 2011 (para 21 of Annexure 2). The relevant provision from that Letter of Offer provided that "[a]n Honour Fee of $37.70 is payable if ANZ pays drawings on your account in excess of the Facility Limit. This fee is payable on the date of the excess drawing".

Thus, the fee was expressed to be charged for considering a request for an informal overdraft, but would be charged once per day irrespective of the number of transactions.

(d) Dishonour Fees: the terms of Business Account 58555 were set out at [89]-[91] of the reasons, as follows:

(c) Dishonour Fees (Exception Fees 62-71)

89 For Exception Fees 62-71, the contractual documents comprised the documents at [86] above (or materially and substantively the same documents) as well as the Overdraft Facility Letter of Offer dated 29 November 2011 at [88] above.

90 The parties accepted that the contractual documents were materially and substantively similar to the December 2009 Terms and Conditions and the December 2009 Business Fees and Charges Booklet: see [83] above. The December 2009 Terms and Conditions provided:

At the Bank's discretion, a cheque may be dishonoured or payment refused where:

• there are insufficient funds in the account of the drawer;

…

ANZ may charge a dishonour fee.

…

If you do not satisfy ANZ's credit criteria for an Informal Overdraft, ANZ will decline your request and will not allow the debit to be processed. You will be charged an Informal Overdraft Assessment Fee (referred to in your bank statements and in the 'ANZ Business Banking Transaction Accounts Fees and Charges' booklet as an 'Outward Dishonour Fee') and this fee is payable immediately.

91 The December 2009 Business Fees and Charges Booklet provided:

Outward Dishonour Fee $37.70 per dishonour

Charged for considering a request for an Informal Overdraft where you do not satisfy ANZ's credit criteria for an Informal Overdraft.

The fee was thus expressed to be charged per transaction for considering a request for an informal overdraft where the ANZ's credit criteria were not satisfied.

Penalties

17 It is convenient to deal with the question of penalties first. Mr Paciocco and SDG, as well as ANZ, appeal against the primary judge's conclusions.

18 It is convenient first to identify the approach of the primary judge and then consider the challenges to her Honour's reasoning and approach leading to her conclusion.

The approach of the primary judge

General principles

19 From [13]-[48] of the reasons, the primary judge set out the relevant principles in the light of the High Court's decision in Andrews v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2012] HCA 30; 247 CLR 205 (Andrews (HC)). As her Honour pointed out, the principal operative conclusion from Andrews (HC) was that the doctrine of penalties in Equity had not been subsumed in the common law leading to the necessity to consider the question at common law and in Equity.

20 Prior to her discussion of the principles at common law and Equity, the primary judge set out at [15] of the reasons a structure of analysis which she employed as follows:

15 To assist in understanding the form and substance of the following analysis, a particular stipulation may (not must) be considered by reference to the following steps:

1. Identify the terms and inherent circumstances of the contract, judged at the time of the making of the contract: Dunlop at 86-87 and AMEV-UDC Finance Limited v Austin (1986) 162 CLR 170.

2. Identify the event or transaction which gives rise to the imposition of the stipulation: Dunlop at 86-87 and Andrews High Court at [12].

3. Identify if the stipulation is payable on breach of a term of the contract (a necessary element at law but not in equity). This necessarily involves consideration of the substance of the term, including whether the term is security for, and in terrorem of, the satisfaction of the term.

4. Identify if the stipulation, as a matter of substance, is collateral (or accessory) to a primary stipulation in favour of one contracting party and the collateral stipulation, upon failure of the primary stipulation, imposes upon the other contracting party an additional detriment in the nature of a security for, and in terrorem of, the satisfaction of the primary stipulation.

5. If the answer to either question 3 or 4 is yes, then further questions arise (at law and in equity: see Andrews High Court at [77]) including:

5.1 Is the sum stipulated a genuine pre-estimate of damage?

5.2 Is the sum stipulated extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved?

5.3 Is the stipulation payable on the occurrence of one or more or all of several events of varying seriousness?

These questions are necessarily interrelated.

6. If the answer to question 5 is that the sum stipulated is not a genuine pre-estimate of damage and is extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have been sustained by the breach, or the failure of the primary stipulation upon which the stipulation was conditioned, then the stipulation is unenforceable to the extent that the stipulation exceeded that amount. Put another way, the party harmed by the breach or the failure of the primary stipulation may only enforce the stipulation to the extent of that party's proved loss: Andrews High Court at [10].

21 A number of points relevant to the arguments on appeal need to be noted at this point. First, at [21] of the reasons, her Honour emphasised that whether a provision is a penalty at law is a question of construction that must be determined as a matter of substance viewing the contract as a whole; and the provision is judged at the time the contract is made.

22 Secondly, at [14] of the reasons, her Honour noted that although the circumstances that enliven the doctrine at common law and in Equity are different (breach of contract at law, and a collateral or accessory stipulation in Equity) common to both is that the provision will not be a penalty (at law or in Equity) unless it is "extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved." This point was the subject of some elaboration at [39]-[45] of the reasons. Importantly, at [39] of the reasons, the primary judge noted the essential element (at law or in Equity) of the sum being extravagant, exorbitant and unconscionable, referring to Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company Limited v New Garage and Motor Company Limited [1914] UKHL 1; [1915] AC 79 at 86-87; Ringrow Pty Ltd v BP Australia Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 71; 224 CLR 656 at 669 [31]-[32]; Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding Company v Don Jose Ramos Yzquierdo Y Castaneda [1905] AC 6 at 10 and 17; AMEV-UDC Finance Ltd v Austin [1986] HCA 63; 162 CLR 170 at 197 and 201; and Story J, Commentaries on Equity Jurisprudence, as Administered in England and America (13th Ed, Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1886) Vol 2.

23 In dealing with the position at law, the primary judge referred to Dunlop at 86-87, 97 and 101-102. In discussing the position in Equity, the primary judge noted the essential question identified by the High Court in Andrews HC at [10]: whether, as a matter of substance, the collateral or accessory stipulation operates in the nature of a security for, and in terrorem of, the satisfaction of the primary stipulation, in the sense that the collateral stipulation, upon the failure of the primary stipulation, imposes an additional detriment on the first party to the benefit of the second party. The identification of the existence of such a collateral stipulation involves recognising the "operative distinction" (Andrews (HC) at [80]-[82]) between such a stipulation and one giving rise consensually to an additional obligation in exchange for an additional benefit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pty Ltd v Greenham [1966] 2 NSWR 717 at 723-724 and 727.

24 In relation to this distinction, the High Court in Andrews (HC) at [80] quoted from French v Macale (1842) 2 Drury and Warren 269 at 275-276, in which passage Lord St Leonards said that the distinction was to be drawn "according to the true construction of the contract".

25 The primary judge further noted in this discussion of the position in Equity that the distinction between a penalty and a genuine pre-estimate of damages made by Lord Dunedin in Dunlop at 86 was a product of Equity jurisprudence: Andrews (HC) at [15]. It was the availability of compensation which generated the equity upon which the court intervenes: Andrews (HC) at [11]. Her Honour elaborated upon this critical distinction in an important section of her reasons at [40]-[42]. Though her Honour did not deal with the matter quite in the following terms in those paragraphs, the following can be seen to be the approach she was describing. Even if it be wrong to attribute the following to her Honour in these paragraphs, the following, nevertheless, represents an approach that is relevant to the resolution of this appeal and an approach that is, for the reasons later discussed, correct. The requirement for extravagance and unconscionability and its distinction from a genuine pre-estimate of damage must require the latter concept to be a broad objective one, not limited to a clause expressly said to be a genuine pre-estimate of damage or containing a sum actually fixed in amount by reference to contemporaneous considerations concerned with such. Rather, if extravagance and unconscionability, on the one hand, and a genuine pre-estimate, on the other, are to operate as the relevant universe of discourse, the latter must be a descriptive phrase used to explain a sum paid upon breach of a term or pursuant to a collateral stipulation upon the failure of the primary stipulation that is not extravagant and not out of all proportion to the compensation for the breach or failure of the stipulation. The penal character of the provision is derived from the extravagance of the relationship between the payment and the possible loss capable of compensation. If there is no such extravagance present, the provision failure of which (by breach or not) admits of compensation is taken to be a genuine pre-estimate of damage, and not penal in character. This is so, even if the parties do not express the clause to be an agreed pre-estimate of damage and even if the parties did not negotiate or set the amount payable by reference to an estimate of damage.

26 The legitimacy of the above approach is central to dealing with ANZ's appeal and its argument that the primary judge failed to address the question of extravagance and exorbitance prospectively, that is ex ante, in the manner that she said was necessary in [43]-[45] of the reasons, as follows:

43 How then does equity and the common law distinguish between provisions that are penal rather than compensatory? In AMEV, after acknowledging that equity and the common law have long maintained a supervisory jurisdiction not to rewrite contracts imprudently made but to relieve against provisions which are so unconscionable or oppressive that their nature is penal rather than compensatory, the High Court stated that the test to be applied in drawing that distinction (at 193):

is one of degree and will depend on a number of circumstances, including (1) the degree of disproportion between the stipulated sum and the loss likely to be suffered by the plaintiff, a factor relevant to the oppressiveness of the term to the defendant, and (2) the nature of the relationship between the contracting parties, a factor relevant to the unconscionability of the plaintiff's conduct in seeking to enforce the term.

That test was subject to an important qualification that "[t]he courts should not, however, be too ready to find the requisite degree of disproportion lest they impinge on the parties' freedom to settle for themselves the rights and liabilities following a breach of contract": at 193-194.

44 In assessing whether the stipulated sum is extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison to the maximum loss that might be suffered from the breach (or failure of the primary stipulation), the Court may receive evidence addressing the quantum of loss that may have been suffered, assessed as at the date of contract: Elberg v Fraval [2012] VSC 342 at [99]ff citing Robophone Facilities v Blank [1966] 1 WLR 1428.

45 That task is simply stated but not necessarily straightforward. It is for the Applicants to prove that the stipulated sum was extravagant and unconscionable but, as ANZ sought to do here, that does not prevent ANZ from seeking to establish that the stipulated sum was not extravagant and unconscionable: Clydebank at 16 and Ringrow at [27]. A calculation of the maximum loss that might be suffered from the non-performance of a primary stipulation involves a forward-looking or hypothetical assessment.

27 At [46]-[48] of the reasons, the primary judge discussed the correct approach in Equity once a provision is found to be penal: to relieve the burdened party of the penal effect of the provision by restricting the party with its benefit to compensation for loss actually suffered by it from the failure of the provision. This assessment is made ex post. So, the provision is unenforceable only to the extent that the amount stipulated exceeded the quantum of loss or damage proved to have been sustained by the breach or failure: see Andrews (HC) at [10] resolving the apparent discordance in AMEV-UDC Finance Ltd v Austin between the approach of Mason and Wilson JJ at 192-193 (favouring the unenforceability or voidness of penal provisions) and the approach of Deane J at 199-203 (limiting the unenforceability to that which exceeds the true damnification), in favour of the views of Deane J. At [48] of the reasons, her Honour said the following:

…Equity assesses the quantum of loss or compensation based on what is just and equitable, or fair and reasonable, in all the circumstances. …

28 It will be necessary to consider the scope of this compensation and its relationship to the ex ante assessment of what is extravagant or exorbitant. In this regard, it is to be borne in mind that the approach of Equity was, as Mason and Wilson JJ said in AMEV-UDC at 190, that the actual damage suffered was assessed in an action at common law such as in an action of covenant, or upon a special issue quantum damnificatus which could be joined in an action on the case. On the other hand, the ex ante assessment of extravagance or exorbitance can be seen to be infused by notions of disproportion to, and unconscionable excess over, the legitimate interests of the covenantee represented by "the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have followed from the breach": Dunlop at 87 (para 4(a)).

The wider framework in which to consider the provisions

29 After identifying the relevant contractual provisions at [49]-[91] of the reasons (as to which, see above) the primary judge considered the wider framework of the contractual provisions in question. The requirement for the proper context for the examination of the provision was derived from the requirement, as Lord Dunedin said in Dunlop at 86-87, of examining the provision in the "inherent circumstances" of each particular contract.

30 At [92]-[102] of the reasons, the primary judge referred to three bodies of context that were relevant: (a) the applicable regulatory framework that was described by her Honour in Andrews v ANZ [2011] FCA 1376; 211 FCR 53 at [87]-[134]; (b) the established principles concerning the banker and customer relationship summarised by her Honour in Andrews 211 FCR 53 at [81]-[82]; and (c) various "inherent circumstances" of each contract relied on by Mr Paciocco and SDG.

31 It is unnecessary to say anything about the regulatory framework at this stage. Neither side referred to her Honour's discussion of this in Andrews 211 FCR 53, nor indicated any error in that regard.

32 As to the principles concerning the relationship of banker and customer, the primary judge rejected the submission of Mr Paciocco and SDG that they were merely historical, saying that they were to be seen as inherent in the arrangement. In particular, the core banking law principles inherent in the arrangement included the following set out at [93] of the reasons and taken from Andrews 211 FCR 53 at [82]:

1. A savings or deposit account is in law a loan to the banker: Pearce v Creswick (1843) 2 Hare 286; Dixon v Bank of New South Wales (1896) 17 LR (NSW) Eq 355; Khan v Singh [1936] 2 All ER 545. The bank borrows the money and proceeds from the customer and undertakes to repay them on demand. The bank's undertaking includes a promise to pay any part of the amount due against the written order of the customer addressed to the branch of the bank where the account is kept: Joachimson at [127]. Conversely, the bank will not pay any part of the amount due to the customer without such an order or some other compulsion or entitlement recognised by law;

2. The issue of a cheque by a customer, or the giving of a payment instruction or withdrawal request to its bank, which would have the effect of overdrawing a customer's account, is construed as a request by the customer for an advance or loan from the bank, and the bank has a discretion to approve or disapprove the loan: Cuthbert v Robarts, Lubbock & Company [1909] 2 Ch 226 at 233; Barclays Bank Ltd v W J Simms Son & Cooke (Southern) Ltd [1980] 1 QB 677 at 699-700; Ryan v Bank of New South Wales [1978] VR 555 at 577; Narni Pty Ltd v National Australia Bank Ltd [1998] VSC 146 at [37] and Narni Pty Ltd v National Australia Bank Ltd [2001] VSCA 31 at [21];

3. A written order by a customer which requires the bank to pay a greater amount than the balance standing to the credit of the customer may be declined. There is no obligation on the bank to pay a cheque unless there is a sufficient balance in the account to pay the entire amount or unless overdraft arrangements have been made which are adequate to cover the amount of the cheque: Bank of New South Wales v Laing [1954] AC 135 at [154]; Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc [2008] EWHC 875 (Comm) at [45] and Narni [2001] VSCA 31 at [12];

4. If a customer with no express overdraft facility draws a cheque which causes his account to go into overdraft, the customer, by necessary implication, requests the bank to grant an overdraft on its usual terms as to interest and other charges: Lloyds Bank plc v Voller [2000] 2 All ER (Comm) 978 at 982.

33 At [95] of the reasons, the primary judge noted the four main "inherent circumstances" relied on by Mr Paciocco and SDG: (a) the lack of negotiation of the terms and their unilateral provision by ANZ; (b) the charging by other banks of similar fees; (c) the right of ANZ unilaterally to vary the terms and conditions; and (d) the determination of the quantum of the fees by ANZ and the fact that it did not do so by reference to any amount that would have been recovered in damages.

34 These considerations were accepted by ANZ; but it relied on a number of other considerations which were identified at [96]-[102] of the reasons. The first was the size of ANZ's business which included six million retail depositors, two million consumer credit card accounts and over half a million business accounts. These considerations dictated the nature and manner in which the contracts were offered, entered into and administered.

35 Secondly, the standard terms, offer letters and other documentation were all available to customers, at the time of opening accounts, in leaflets with statements, and in letters when honour fees were invoked. The accounts could be terminated at will; and it was up to the customer whether to engage in transactions.

36 Thirdly, customers had it within their power to avoid the fees. Apart from monitoring their own behaviour, they could "switch off" or opt out of the ability, except in certain circumstances, to overdraw their accounts and so avoid fees. Further, they could close accounts which did not permit or limit the right to overdraw.

Whether the provisions were penalties

37 With this background, her Honour then turned, in Part 6 of the judgment, to the analysis as to whether the different exception fees were penalties.

38 This analysis was done by reference to the two periods (pre and post-December 2009) and by reference to late payment fees and fees other than late payment fees.

Late Payment Fee – pre December 2009

39 The primary judge said that ANZ only maintained a formal submission, in relation to both periods, that the fee was not payable upon breach of contract. Her Honour proceeded to deal with the relevant provisions from [113] and from [180] of the reasons.

40 At [114] and [181] of the reasons, the primary judge rejected the submission of ANZ (that was renewed on appeal) that the fees were payable upon a further period of credit necessarily extended by it to the customer because of an absence of timely payment. Her Honour concluded at [114] of the reasons, referring to the provisions at [53]-[57] of the reasons (see [15(a)] above), as follows:

… A plain reading of the contractual documents and the applicable Exception Fee Provisions leads to the conclusion that the Late Payment Fee was payable upon breach by the customer of his contractual obligation to make payment by a stated date: see [53]-[57] above. Contrary to the submission of ANZ, the stipulation was not a fee payable upon a further period of credit necessarily extended by the bank to the customer because of the absence of timely payment. The credit had already been extended. It was the repayment of the credit, or at least part of the credit, already extended that ANZ was seeking. Put another way, no further credit was extended.

See also [181].

41 At [115] and [182] of the reasons, the primary judge said that if not payable upon breach, the late payment fee provision was collateral to the primary stipulation to pay by the due date.

42 At [116] and [182] of the reasons, the primary judge concluded that at law and in Equity the collateral stipulation was, as a matter of substance, to be viewed, as security for or in terrorem of, the satisfaction of the primary stipulation. This conclusion flowed from the express language, the subject matter of the stipulation (from not paying money), and from the fact that the payment was not for further credit.

43 It will be important, in due course, when dealing with the complaints of ANZ on its appeal to appreciate that her Honour can be taken to have incorporated her reasoning in Andrews 211 FCR 53 where she dealt in detail (at [239]-[251]) with the argument of ANZ, which was formally maintained and repeated. Thus, the expression used by the primary judge at [114]-[116] of the reasons, should be understood in the light of the more detailed treatment of the argument in Andrews 211 FCR 53 at [239]-[251].

44 These conclusions at [114], [115], [116], [181] and [182] are challenged on appeal. For the reasons expressed later, that challenge fails.

45 The primary judge then returned to extravagance, exorbitance and unconscionability with which she dealt at [117]-[169]. It is to be recalled that, on a number of occasions ([14], [15 (5.2)], [39] and [45] of the reasons), the primary judge referred to the essentiality of the party impugning the provision as penal to demonstrate (whether at law or in Equity) that the provision is extravagant or exorbitant and unconscionable in amount. ANZ contends that, in this section, the primary judge made a fundamental error by failing to deal with this question, either at all, or on the correct basis of a forward looking, ex ante analysis.

46 The primary judge began the analysis at [117] of the reasons by stating once again the further "and essential" element of a penalty (at law or in Equity) that the stipulated sum be extravagant, exorbitant and unconscionable. ANZ points out that, at this point in the reasons as supporting material, her Honour referred to the earlier parts of her reasons dealing not only with "Extravagant, Exorbitant and Unconscionable" (Part 4E), but also that dealing with "Loss and Damage" (Part 4F). The latter is the ex post calculation of loss in fact, once a provision has been characterised as penal.

47 The primary judge then, at [119], examined three categories of factual consideration that were said to be relevant to the question of extravagance and unconscionability. The first category were some features of the late payment fee. One feature was that the same fee was payable regardless of whether the late payment was of a short or long period or of a trifling or large amount. At [119], her Honour said, the test in para 4(c) in Dunlop was engaged – the so-called third rule of construction because there was a presumption (but no more) that the stipulation was a penalty because a single sum was payable by way of compensation on the occurrence of one or more or all of several events, some of which may occasion serious, and others trifling damage. The primary judge then continued at [119] of the reasons:

… As a result, there necessarily was a degree of disproportion between the stipulated sum and the loss likely to have been suffered by ANZ…

48 The primary judge continued at [120]-[121] of the reasons:

120 That degree of disproportion cannot be considered in isolation. Other contractual terms must be considered. In particular, it must be recalled that, in addition to the late payment fee, the same contractual documents entitled ANZ, amongst other things, to charge (which it did) annual interest of 12.24% on the specific outstanding amount.

121 That leads to the second rule of construction referred to by Lord Dunedin in Dunlop and described by him as conclusive: see [18(4)(b)] above. The first part of that rule of construction was applicable to the Late Payment Exception Fees – the breach (or failure of the stipulation) consisted only in not paying a sum of money. The question which then arose was whether the second part of that rule was met – is the sum stipulated a sum greater than the sum which ought to have been paid? The Applicants said it was, ANZ said it was not. Before turning to that aspect, it is necessary to consider the other categories of facts and matters identified by the Applicants.

49 Thus, at this point of the reasons, her Honour's approach was that, given the circumstances here were that the breach or failure was the failure to pay a sum of money (which could be $0.01, late by one day, or a large sum, late by weeks), the question of the "degree of disproportion" and the question whether the provision was penal fell to be considered by reference to whether or not no more was paid by the fee as the stipulated sum than the sum which ought to have been paid.

50 That exercise was dealt with by her Honour at [131]-[176] being the "quantitative assessment" by reference to the expert evidence of Mr Inglis and Mr Regan. Central to her Honour's approach was her conclusion, drawn from para 4(c) of Dunlop and Lord Elphinstone v Monkland Iron and Coal Co (1886) 11 AC 332 (see [119] of the reasons) that the provision was prima facie a penalty; and her conclusion as to the relevance of para 4(b) of Dunlop that given the fee was payable for the non-payment of a sum of money, the question was whether the sum was greater than the sum which ought to have been paid: Dunlop at 87 (see [121] of the reasons). The rebuttal of that presumption arising from para 4(a) of Dunlop and the enquiry required by para 4(b) of Dunlop was, her Honour said at [139], to be executed by undertaking an enquiry as:

… to what extent (if any) did the amount stipulated to be paid exceed the quantum of the relevant loss or damage which can be proved to have been sustained by the breach, or the failure of the primary stipulation, upon which the stipulation was conditioned: see [48] and [126]-[130] above.

51 By this expression of the matter, the primary judge did not consider it necessary to undertake a forward looking, ex ante, analysis in part because of the relevance and application of the third and second tests in paras 4(c) and (b) of Dunlop, respectively. The relevance and application of the third test (4(c)) reflects the acceptance by the primary judge that some breaches would lead to trifling damage. The second test (4(b)) is one that depends upon a comparison between the sum in the stipulation and the sum "which ought to have been paid". Given this was a nominal money sum, any argument by ANZ that some greater amount was payable (in damages for the breach or failure) was taken by her Honour to be an ex post calculation, not the forward looking, ex ante, calculation of the "greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have followed from the breach" (for the purposes of para 4 (a) in Dunlop). One aspect of that conclusion was what her Honour described as ANZ's admission that the late payment fee was not a genuine pre-estimate of damage. At [129] of the reasons, the primary judge said the following in relation to her rejection of the utility of examining certain ANZ documents said to show the bank's intention:

That documentation does not assist in the resolution of the question to be answered in this case. Having determined that the Exception Fee Provisions relating to Late Payment Fees were prima facie a penalty at law and in equity and given that ANZ admitted that the Late Payment Fee was not a genuine pre-estimate of damage, the question left to be determined is to what extent (if any) did the amount stipulated to be paid exceed the quantum of the relevant loss or damage which can be proved to have been sustained by the breach, or the failure of the primary stipulation, upon which the stipulation was conditioned: see [48] above. Again, none of those matters identified answered or assisted in answering that question.

52 That analysis (as well as the conclusion in [139]) was the subject of complaint by ANZ on appeal. Its central submission was that the primary judge, wrongly substituted without justification in all the circumstances an ex post calculation of actual damage from the breaches by Mr Paciocco and SDG for the correct ex ante enquiry of the greatest loss that could be proved to have followed from a breach. For the reasons that follow, that central submission should be accepted.

53 The clarity of the primary judge's language that the question left to be determined was an ex post analysis of the damage caused by the breaches in question (by Mr Paciocco and SDG) is to be noted. There was an attempt in submissions on appeal by Mr Paciocco and SDG to construct from some of the language used elsewhere in the reasons an argument that the primary judge did engage in a forward looking analysis of the greatest conceivable damages that might flow from such a breach. For reasons to which I will come, that argument must fail: principally because, as at this point in the reasons, the primary judge did not say that she was undertaking that task.

54 Before turning to the calculation of the sums, her Honour dealt at [122]-[130] of the reasons, with various other matters raised by Mr Paciocco and SDG as relevant. The inherent circumstances that her Honour had considered at [92]-[102] of the reasons (and discussed at [30]-[36] above) were also relevant to her conclusion as to the penal character of the provision and fees. At [123] of the reasons, her Honour said:

However, taken as a whole, these circumstances provide further support for the conclusion that, at least on its face, the late payment provision and fee is penal. ANZ was able to impose these fees because of the inequality of bargaining power between the Bank and its customer (here Mr Paciocco). The terms were contained in printed forms, which the customer had no opportunity to negotiate. There was no agreement between "people contracting on equal terms": English Hop Growers v Dering [1928] 2 KB 174 at 181.

55 The primary judge refused, however, to give any weight to certain business records of ANZ which Mr Paciocco and SDG said were relevant. These were records that were said to demonstrate ANZ's state of mind and commercial intention in levying the fees. The primary judge rejected these documents for a number of reasons: their selectivity (see [128] of the reasons); that the enquiry as to extravagance was objective not subjective (see [126] of the reasons); and the importance of what her Honour took to be ANZ's admission that the late payment fee was not a genuine pre-estimate of damage (see [129] of the reasons).

56 Given the nature of the subject matter, it is convenient to deal with the detail of her Honour's ex post quantitative analysis when dealing with ANZ's arguments on appeal. At [173] of the reasons, the primary judge concluded that ANZ suffered some loss or damage by each late payment exception fee event of no more than $3, though, for some fees, the damage was $0.50. This was comprised of operational collection costs (to the extent they existed) rounded up. The balance over this was penal and recoverable.

Late Payment Fee – post December 2009

57 The same approach applied to the late payment fees after December 2009. The loss in respect of each event was calculated at $0.50: see [234]-[242] of the reasons.

The other fees – Honour, Overlimit and Non-Payment Fees: pre-December 2009

58 The primary judge dealt with the position before December 2009, in respect of the honour fee in Savings Account 156 at [188]-[212] of the reasons, with the overlimit fees on the Card Accounts at [213]-[229] of the reasons, and with non-payment fees at [230]-[233].

The Savings Account Honour Fee

59 The terms of the provision were set out at [63] and [65]-[66] of the reasons: see [15(c)] above. Her Honour referred to as relevant the other circumstances discussed at [117]-[130] of the reasons: see [46]-[48] and [54]-[55] above. Her Honour then referred to what were the uncontentious "exception fee events": see [190]-[195] of the reasons.

60 At [196]-[204] of the reasons, the primary judge construed the honour fee as not payable on breach of contract. Mr Paciocco and SDG focused in their submissions upon the statement by ANZ in its terms and conditions that it was a required condition of all accounts that the customer must not overdraw an account without prior arrangements being made and agreed with ANZ. The primary judge rejected that focus as too narrow, noting that the relevant term (cl 2.12 of the August 2008 Terms and Conditions: ([65] of the reasons and [15(c)] above) deals with the discretion of ANZ to deal with a debit that would overdraw the account. This discretionary conduct by ANZ was, her Honour said, to be placed into the framework of the banker and customer relationship, with the consequence that it was to be viewed as set out at [198] of the reasons:

198 …

1. A withdrawal or payment instruction given by a customer that would have the effect of overdrawing the customer's account or exceeding the account credit limit is to be construed as a request from the customer for an advance or loan from ANZ. ANZ may approve or decline the request in its discretion: Andrews Trial at [82], [177], [279], [306] and [322].

2. The overdrawing of a customer account (whether a deposit account or a credit card account) was not a unilateral action by the customer, but was an action that required the consensual conduct of ANZ and the customer: for example, see [191] above. For the transaction to proceed, ANZ had to agree to and approve or authorise the transaction: Andrews Trial at [182], [280], [291], [307] and [323].

3. Overdrawing the account could not constitute a breach by the customer of a contractual obligation. Such transactions fell within the express provisions of the applicable contractual terms which stated that ANZ may allow or authorise such transactions, or were outside the contractual terms because ANZ approved the transaction: Andrews Trial at [182], [280], [291], [307] and [323].

4. It was not a breach of contract for ANZ's customers to give a withdrawal or payment instruction to ANZ that would have the effect, if honoured, of overdrawing the customer's account or exceeding the account credit limit. The relevant provisions of the customer contracts did not impose a contractual obligation not to give such an instruction. In fact, the relevant provisions stated expressly that ANZ may allow or authorise such a transaction: Andrews Trial at [185], [186], [208], [214], [328] and [331].

5. Honour and overlimit fees (as will become relevant later) were charged by ANZ as a consequence of a customer issuing a withdrawal or payment instruction to ANZ that would have the effect, if honoured, of overdrawing the customer's account or exceeding the account credit limit and ANZ approving or authorising the instruction. The fees were charged in respect of ANZ's decision concerning the request for additional borrowing: Andrews Trial at [182], [183], [187], [279], [280], [291], [306], [307] and [328]. The honour fee in respect of consumer accounts was charged once per day, regardless of how many transactions that occurred on that day overdrew the account (Andrews Trial at [187]) and the overlimit fee in respect of card accounts was charged once per month, at the end of a statement period, if the balance of the account exceeded the credit limit during the statement period: Andrews Trial at [277]. Honour and overlimit fees were not charged by ANZ upon a breach of contract by the customer.

This analysis is equally applicable to the Exception Fee Provisions in this case: see [65]-[66] above in relation to Exception Fee 1, and in respect of other Honour and Overlimit Fees to be discussed later in these reasons, see [60]-[62] (Overlimit Fee), [77]-[79] (Overlimit Fee), [84]-[88] (Business Honour Fee) and [248] (Overlimit Fee); see also Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc [2008] EWHC 875 (Comm) at [76]-[80].

61 Thus, there was no breach.

62 Mr Paciocco and SDG attacked this approach on appeal. For the reasons later set out, that attack fails.

63 The primary judge then (from [200] of the reasons) examined whether the fee was collateral or accessory to a primary stipulation. The primary judge rejected the submission that from all the circumstances it was clear that the event ANZ was seeking to discourage was exceeding the limit. The rejection (at [202] of the reasons) was because the fee was not payable upon the failure of a stipulation – ANZ was not bound to meet the request. Her Honour said at [202]:

Those contentions are rejected. They are rejected because the Honour Fee is not payable upon failure of a stipulation. ANZ was not bound to meet the customer's request. The liability to pay the fee arose as a result of, and in exchange for, something more than and different from that which had existed up to that point in time. Properly construed, the provision which entitled ANZ to charge the Honour Fee did not impose a fee to be regarded as security for performance by the customer of other obligations to ANZ. It was a fee charged in accordance with pre-existing arrangements according to whether ANZ chose to provide something more and further to the customer. In the present case, it was a fee charged by ANZ for authorising payments upon instructions by Mr Paciocco upon which ANZ otherwise was not obliged to act: see [33]-[38] above.

64 This reasoning can be seen to be founded upon the substantive importance of the principles to the banker customer relationship to which her Honour had referred. This is the subject of significant attack on appeal. For the reasons later set out, that attack fails.

65 At this point in the reasons ([203]-[204]), the primary judge discussed the relevance of so-called "shadow limits". Shadow limits (as explained by the primary judge at [101] of the reasons) were informal limits that enabled the customer (unless he or she opted out of the arrangement) to be given additional credit upon the payment of the relevant fee. This permitted, as the primary judge said at [203], the ANZ to deal with the discretionary credit arrangement (and the fee) automatically.

66 At [205]-[208] of the reasons, the primary judge rejected the contention (though it was unnecessary to do so) that the honour fee was unconscionable.

The Card Account Overlimit Fee

67 The terms of these provisions were set out at [59]-[62] of the reasons: see [15(b)] above. Again, her Honour referred to as relevant the other circumstances discussed at [117]-[130] of the reasons: see [46]-[48] and [54]-[55] above. Her Honour then referred to what were the uncontentious "exception fee events": see [214]-[219] of the reasons.

68 At [220]-[227] of the reasons, the primary judge construed the overlimit fee as neither payable upon breach of a term or as collateral (or necessary) to a primary stipulation. This was for the same reasons as her Honour reached this conclusion in respect of the honour fee. Her Honour saw it (see [222] of the reasons) as substantially the same, notwithstanding the differences in nomenclature. The clause provided for what was said to be prohibited: overdrawing and the consequences in cost thereof. The customer chose to initiate the transaction that the ANZ could choose to honour, for a fee. The essence of the reasoning was set out with clarity in [224] and [225] of the reasons as follows:

224 An overlimit fee was not charged in order to secure the performance of a primary stipulation not to overdraw the account or initiate an overdraw transaction. Rather, the customer was entitled to initiate such a transaction and the fee was payable in respect of ANZ's consideration of and decision in respect of the request for a further advance. The fee was charged if ANZ chose to allow the transaction and thereby approve the request for additional borrowing. Moreover, an overlimit fee was charged once per month, regardless of how many transactions occurred in that month which caused the credit limit to be exceeded: see [61]-[62] above. The fee was not payable upon a failure of a stipulation. It was payable in respect of ANZ's response to the request for further borrowing. Indeed, it was not payable each time that a request and response was made. It was only payable once per month.

225 As was the position with Saving Account 156, it was within ANZ's power to prevent Mr Paciocco from overdrawing his Card Accounts. There was no necessity for ANZ to accommodate such informal requests for additional borrowings and exercise any discretion with respect to the requests. ANZ could have elected not to permit Mr Paciocco to overdraw at all. Instead of preventing overdraw transactions, ANZ anticipated and planned for such transactions and developed procedures and systems to assess and determine whether to allow the overdrawing to occur. The fact that ANZ chose to accommodate these informal requests, when there was no necessity for it to do so, supports the conclusion that the overlimit fee cannot be characterised as security for the performance of a stipulation, especially a stipulation not to overdraw the credit limit. As noted above, the overlimit fee was a consensual additional obligation in the card account and not a penalty. The term imposed a fee in circumstances where Mr Paciocco had the right to initiate a transaction that would exceed the credit limit, thereby seeking further accommodation from ANZ, and the fee was payable for ANZ's consideration and approval of the relevant instruction.

69 The primary judge again concluded (though not needing to do so) for the same reasons as related to the honour fee, that this fee was not extravagant or unconscionable.

Non-Payment Fee

70 At [230]-[233] of the reasons, the primary judge dealt with certain fees that ANZ accepted were charged without contractual authority.

The other fees – Honour, Overlimit and Non-Payment Fees: post December 2009

71 Once again, the terms of the provisions, and the fee exception events for all these fees were not in dispute: see [16] above, and see [244], [255]-[257] and [268]-[269] of the reasons. Once again, in respect of each of these fees, the primary judge referred to as relevant the other circumstances discussed at [117]-[130] of the reasons.

Overlimit Fee

72 Mr Paciocco's case was that, whilst this was not payable on breach of contract, cf cl 2 of the March 2010 Conditions of Use at [16(b)] above, the fee (and the provision for it) was collateral or accessory to a primary stipulation in favour of ANZ.

73 The primary judge rejected this submission for the same reason that she had rejected the submission concerning the honour fee (to which this fee was substantially the same). Again, it is appropriate to use her Honour's own clear words in [249]-[250] of the reasons to reveal the reasoning:

249 That action required (as the clause stated) the consensual conduct of ANZ and Mr Paciocco. For the transaction to proceed, ANZ had to agree to and authorise the transaction: see [192]-[195] above. The overdraw transaction was a request by the customer for an advance or loan from ANZ which ANZ had the discretion to approve or disapprove: see [93] above. The overlimit fee became payable upon the customer initiating an overdraw transaction and ANZ exercising its discretion to approve the loan. The card account expressly contemplated the occurrence of overdraw transactions and stipulated that ANZ had a discretion to authorise the transaction and allow it to proceed. The overlimit fee was not charged in order to secure the performance of a primary stipulation not to overdraw the account or initiate an overdraw transaction. Rather, the customer was entitled to initiate such a transaction and the fee was payable in respect of ANZ's consideration of and decision in respect of the request for a further advance. The fee was charged if ANZ chose to allow the transaction and thereby approve the request for additional borrowing. Moreover, an overlimit fee was charged once per month, regardless of how many transactions occurred in that month which caused the credit limit to be exceeded: see [78]-[79] above. The fee was not payable upon a failure of a stipulation. It was payable in respect of ANZ's response to the request for further borrowing. Indeed, it was not payable each time that a request and response was made. It was only payable once per month.

250 As was the position with Saving Account 156, it was within ANZ's power to prevent Mr Paciocco from overdrawing his Card Accounts. There was no necessity for ANZ to accommodate such informal requests for additional borrowings and exercise any discretion with respect to the requests. ANZ could have elected not to permit Mr Paciocco to overdraw at all. Instead of preventing overdraw transactions, ANZ anticipated and planned for such transactions and developed procedures and systems to assess and determine whether to allow the overdrawing to occur. The fact that ANZ chose to accommodate these informal requests, when there was no necessity for it to do so, supports the conclusion that the Overlimit Fee cannot be characterised as security for the performance of a stipulation, especially a stipulation not to overdraw the credit limit. As noted above, the Overlimit Fee was a consensual additional obligation in the card account and not a penalty. The term imposed a fee in circumstances where Mr Paciocco had the right to initiate a transaction that would exceed the credit limit, thereby seeking further accommodation from ANZ and the Overlimit Fee was payable for ANZ's consideration and approval of the relevant instruction.

74 The primary judge again (though not needing to do so) concluded, for the same reasons as related to the honour fee, that this fee was not extravagant or unconscionable.

Business Honour Fee

75 Again, it was accepted by Mr Paciocco and SDG that this fee was not payable upon breach of the terms at [16(c)] above. Again, his case was that the fee was collateral or accessory to a primary stipulation in favour of ANZ.

76 The primary judge again rejected these submissions for the same reasons as she rejected the same submissions for the honour fee and the overlimit fee: see [260]-[264] of the reasons.

77 For the same reasons as related to the honour fee, the primary judge concluded (though it was unnecessary to do so) that the fee was not extravagant or unconscionable.

Business Dishonour Fee

78 Again, Mr Paciocco and SDG accepted that this fee was not payable upon breach; but was collateral or necessary to a primary stipulation in favour of ANZ.

79 Again this was rejected on the basis that, in substance, the fee was (like the honour fee) payable for the consensual giving of credit: [271]-[272] of the reasons.