FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Curtis v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 144

Table of Corrections | |

20 April 2015 | In paragraph 1 and the legislation cited field on the cover page, “Bankruptcy Regulations 1966 (Cth)” has been replaced with “Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth)”. |

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

Appellant | |

AND: | SINGTEL OPTUS PTY LIMITED (ACN 052 833 208) First Respondent OFFICIAL RECEIVER Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 October 2014 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant is to pay the respondents’ costs of and incidental to the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 688 of 2014 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

BETWEEN: | LEON CURTIS Appellant |

AND: | SINGTEL OPTUS PTY LIMITED (ACN 052 833 208) First Respondent OFFICIAL RECEIVER Second Respondent |

JUDGES: | MANSFIELD, GLEESON, BEACH JJ |

DATE: | 30 october 2014 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

The Court:

1 The issue the subject of the present appeal concerns the validity of a bankruptcy notice issued by the Official Receiver under s 41(1) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act) and regs 4.01 and 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth) (the Regulations).

2 On 25 February 2014 the Official Receiver, on the application of the first respondent creditor (Optus), electronically issued a bankruptcy notice BN 169768 in respect of a judgment debt owed by the appellant debtor (Curtis) to Optus (bankruptcy notice). Curtis unsuccessfully challenged the validity of the bankruptcy notice in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia. His principal ground of challenge was that the bankruptcy notice was said to be invalid because it did not have attached to it at the time of issue a copy of the relevant judgment or order.

3 On the present appeal, Curtis has persisted with that ground of challenge. The issues that arise for our consideration are the following: (a) first, whether it is a requirement of the Act and the Regulations that the copy judgment or order be attached to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue; (b) second, whether there was such an attachment at the time of issue; (c) third, if there was any defect, whether s 306(1) of the Act operated to validate the bankruptcy notice. Moreover, these issues are required to be considered in the context of the electronic mode of issue used in the present case.

4 In summary, in our view the challenge fails. It is a requirement of the Act and the Regulations that at the time of issue, a bankruptcy notice must have attached to it a copy of the relevant judgment or order. But that requirement was satisfied in the present case, notwithstanding the electronic mode of issue that was used. The appeal must be dismissed.

Legislative scheme

5 Section 40 of the Act prescribes when an act of bankruptcy has been committed. Paragraph 40(1)(g) provides that an act of bankruptcy occurs when a creditor, who has obtained against a debtor a final judgment or final order (which has not been stayed), has served on the debtor (in Australia) a bankruptcy notice, and the debtor does not within the time specified in the notice “comply with the requirements of the notice or satisfy the Court that he or she has a counter‑claim, set-off or cross demand equal to or exceeding the amount of the judgment debt or sum payable under the final order…”.

6 Subsections 41(1)-(3) of the Act relevantly provide:

41 Bankruptcy notices

(1) An Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice on the application of a creditor who has obtained against a debtor:

(a) a final judgment or final order that:

(i) is of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) is for an amount of at least $5,000; or

(b) 2 or more final judgments or final orders that:

(i) are of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) taken together are for an amount of at least $5,000.

(2) The notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations.

(3) A bankruptcy notice shall not be issued in relation to a debtor:

(a) except on the application of a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order within the meaning of paragraph 40(1)(g) or a person who, by virtue of paragraph 40(3)(d), is to be deemed to be such a creditor;

(b) if, at the time of the application for the issue of the bankruptcy notice, execution of a judgment or order to which it relates has been stayed; or

(c) in respect of a judgment or order for the payment of money if:

(i) a period of more than 6 years has elapsed since the judgment was given or the order was made; or

(ii) the operation of the judgment or order is suspended under section 37.

…

Regulations 4.01-4.02 of the Regulations provide:

4.01 Application for bankruptcy notice

(1) Subject to subregulation (2), to apply for the issue of a bankruptcy notice, a person must lodge with the Official Receiver:

(a) an application in the approved form; and

(b) 1 of the following documents in relation to the final judgment or final order specified by the person on the approved form:

(i) a copy of the sealed or certified judgment or order;

(ii) a certificate of the judgment or order sealed by the court or signed by an officer of the court;

(iii) a copy of the entry of the judgment or order certified as a true copy of that entry and sealed by the court or signed by an officer of the court.

…

4.02 Form of bankruptcy notices

(1) For the purposes of subsection 41(2) of the Act, the form of bankruptcy notice set out in Form 1 is prescribed.

(2) A bankruptcy notice must follow Form 1 in respect of its format (for example, bold or italic typeface, underlining and notes).

(3) Subregulation (2) is not to be taken as expressing an intention contrary to section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.

Note: Under section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901, where an Act prescribes a form, then, unless the contrary intention appears, strict compliance with the form is not required and substantial compliance is sufficient; see also paragraph 46(1)(a) of that Act for the application of that Act to legislative instruments other than Acts.

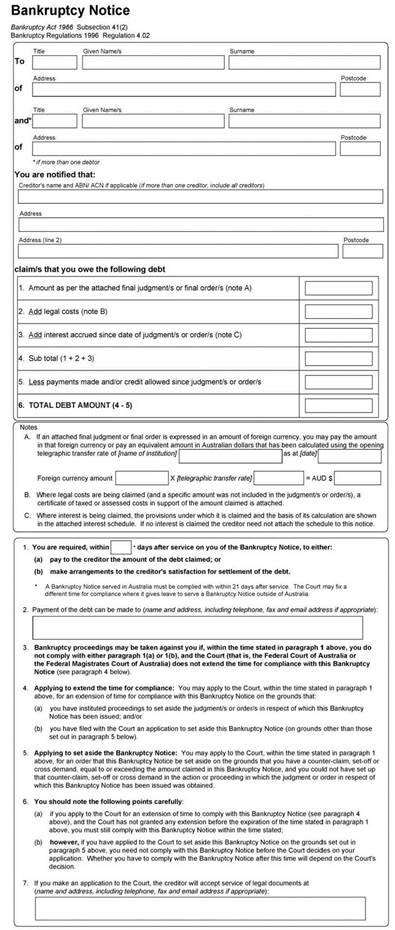

Form 1 of Sch 1 of the Regulations (Form 1) is the prescribed form of a bankruptcy notice and provides:

|

|

|

7 Form 1 does not require identification of the judgment in the text of Form 1 itself. Nevertheless, various of its features refer to the underlying judgment or orders. On the first page of Form 1 a creditor can select the type of debt claimed as being one or more of several items, inter-alia, “1. Amount as per the attached final judgment/s or final order/s (note A)”. Item 3 also refers to interest accrued since the date of judgment. Item 5 refers to payments made and credits allowed since the judgment. Further, Note A provides “[i]f an attached final judgment or final order is expressed in an amount of foreign currency, you may pay the amount in that foreign currency or pay an equivalent amount in Australia dollars…”. Note C provides “[w]here interest is being claimed, the provisions under which it is claimed and the basis of its calculation are shown in the attached interest schedule. If no interest is claimed the creditor need not attach the schedule to this notice”.

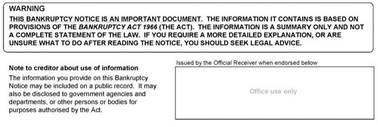

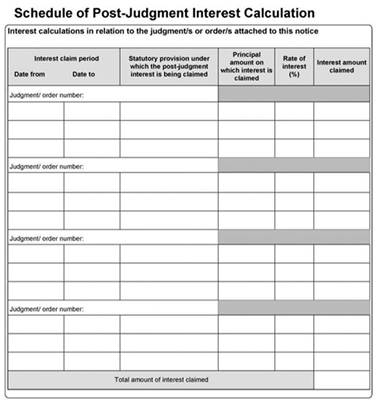

8 Further, on the second page of the Form 1, there are various other statements. Paragraph 4 is a note notifying the debtor concerning applying to extend the time for compliance and providing that this can be applied for where there has been “instituted proceedings to set aside the judgment/s or order/s”. Paragraph 5 is a note referring to applying to set aside the bankruptcy notice, in the circumstance where there is a counter-claim, set off or cross-demand, equal to or exceeding the amount claimed in the bankruptcy notice which the debtor could not have set up in the action or proceeding “in which the judgment or order in respect of which this Bankruptcy Notice has been issued was obtained”. The third page of Form 1, being a schedule of post-judgment interest calculation provides for “[i]nterest calculation in relation to the judgment/s or order/s attached to this notice”.

9 Regulation 16.01 of the Regulations provides:

16.01 Service of documents

(1) Unless the contrary intention appears, where a document is required or permitted by the Act or these Regulations to be given or sent to, or served on, a person (other than a person mentioned in regulation 16.02), the document may be:

(a) sent by post, or by a courier service, to the person at his or her last‑known address; or

…

(e) sent by facsimile transmission or another mode of electronic transmission:

(i) to a facility maintained by the person for receipt of electronically transmitted documents; or

(ii) in such a manner (for example, by electronic mail) that the document should, in the ordinary course of events, be received by the person…

10 Section 306 of the Act provides:

306 Formal defect not to invalidate proceedings

(1) Proceedings under this Act are not invalidated by a formal defect or an irregularity, unless the court before which the objection on that ground is made is of opinion that substantial injustice has been caused by the defect or irregularity and that the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of that court.

(2) A defect or irregularity in the appointment of any person exercising, or purporting to exercise, a power or function under this Act or under a personal insolvency agreement entered into under this Act does not invalidate an act done by him or her in good faith.

Federal Circuit Court proceedings

11 On 4 April 2014, Curtis filed an application in the Federal Circuit Court seeking to set aside the bankruptcy notice. The primary judge granted leave for the Official Receiver to intervene in that proceeding.

12 In that application, Curtis sought a declaration that the bankruptcy notice was not a valid and effectual bankruptcy notice issued pursuant to s 41 of the Act, reg 4.02 of the Regulations and the prescribed form of notice at the time of its issue because at the time of issue the bankruptcy notice did not have attached to it a copy of the final judgment or order relied upon. Curtis sought an order that the bankruptcy notice be set aside. The relevant final judgment or order was a judgment/order of the Supreme Court of New South Wales made in proceeding 2011/00139541 against Curtis and entered on 17 October 2013 (the final judgment or order).

13 Optus opposed that application on the grounds that at the time of issue by the Official Receiver, the bankruptcy notice did have attached to it a copy of the final judgment or order and was therefore valid. In the alternative, Optus contended that all that was required was for the judgment or order to be attached to the notice at the time of service, not issue. There was no dispute that at the time the bankruptcy notice was served on Curtis by Optus, a copy of the final judgment or order was attached. In the alternative, Optus argued that if the final judgment or order was not attached and this constituted a defect, then this was a formal defect or irregularity within the meaning of s 306 of the Act.

14 The Official Receiver submitted that the Act was silent as to the alleged requirement to attach the final judgment or order at the time of issue, and that it was open to the Official Receiver not to attach the final judgment or order to the bankruptcy notice.

15 The procedures generally followed by the Official Receiver in electronically issuing a bankruptcy notice at the relevant time were explained in the following terms (see [12] of the primary judge’s reasons):

The creditor registers its details with the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA), being the government agency responsible for the administration of the personal insolvency system, to gain access to online services on AFSA’s website.

The creditor logs into the AFSA website and submits a bankruptcy notice for approval using AFSA’s online services; the creditor is required to complete a number of ‘fields’ which correspond with the details required by Form 1. The first screen requires the creditor to complete details of the final judgment or order of a Court upon which it relies for the issuing of the notice. The creditor is then required to upload a copy of the sealed or certified final judgment or order of a Court evidencing the debt owed by the debtor.

The creditor reviews the online application before submitting it online, including viewing a draft copy of the bankruptcy notice online prior to submission. The creditor must pay the prescribed fee.

Upon receipt of the application a delegate of the Official Receiver reviews the online application to ensure that all requirements under the Act and Regulations have been met. If the form appears to comply with those requirements, the notice is approved and endorsed by the delegate.

Upon approval by the delegate, the system automatically generates a covering letter to the creditor and a bankruptcy notice in the prescribed form, containing details as entered into the online fields by the creditor.

The system then automatically creates and sends an email to the email address supplied by the creditor with its application. Attached to the email is a covering letter, the endorsed bankruptcy notice and a copy of the final judgment or order which the creditor uploaded with its application, as documents in pdf format. The system inserts into the endorsed bankruptcy notice a unique Bankruptcy Notice number, issued date and signature of the Official Receiver in the ‘Office use only” field.

These procedures were followed in the present case.

16 After following that procedure, Minter Ellison, solicitors for Optus, received an automatic email from AFSA of the type and with the attachments so described.

17 Before the primary judge, Curtis tendered an exhibit identified as “A1” being a coloured copy of a screen-shot showing an email sent from the email address svc-resolve-smtp@afsa.gov.au to Ben Pascoe (being an employee of Minter Ellison) on 25 February 2014 at 16:35 titled “Bankruptcy Notice Accepted for Leon CURTIS Bankruptcy Notice Number: 169768, Issued on 25-Feb-2014 [SEC=UNCLASSIFIED]” with three portable document files accompanying the email as follows (see [15] of the primary judge’s reasons):

(a) a covering letter from AFSA;

(b) the Bankruptcy Notice; and

(c) copy orders of the Supreme Court of NSW dated 17 October 2013.

The message contained in the email stated:

Please find attached correspondence from the Australian Financial Security Authority.

This email was sent via an automated system, please do not reply to this email address. Contact details for reply are included in the attached correspondence…

18 The primary judge held that the bankruptcy notice was valid.

19 In summary, he made the following findings:

First, that the electronic mode of issue of the bankruptcy notice of the type adopted by the Official Receiver did not strictly conform to relevant provisions of the Act and the Regulations (at [6] and [31]-[40]), if the Act and Regulations were considered in isolation;

Second, if the Act and Regulations were considered with the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth) (Electronic Transactions Act), then the electronic mode of issue of a bankruptcy notice of the type adopted by the Official Receiver could conform to relevant provisions of the Act and Regulations (at [6] and [41]-[54]);

Third, there was electronic attachment of a copy of the relevant judgment or order to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue (at [54]);

Fourth, in any event, on one view of his Honour’s analysis (at [72]-[84]), it is not a requirement to attach to the bankruptcy notice a copy of the relevant judgment or order at the time of issue (there is some doubt as to what his Honour precisely held in this respect (cf [6] and [31]));

Fifth, if there was a defect, then s 306(1) of the Act operated to validate the bankruptcy notice in any event (at [55]-[71]).

20 Accordingly, on 19 June 2014 the primary judge ordered that the application be dismissed. Time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice was extended for 21 days from that date. It was further extended until the delivery of judgment by the NSW Court of Appeal in Curtis v SingTel Optus Pty Ltd (2013/342608) (2014) 311 ALR 494; [2014] NSWCA 266. The time for compliance has now expired, so that an available act of bankruptcy has now arisen, assuming the bankruptcy notice to be valid.

The present APPEAL

21 This appeal has been brought by way of a notice of appeal filed on 10 July 2014. Curtis seeks orders setting aside the primary judge’s dismissal of the application with costs, an order that the bankruptcy notice be set aside and an order that Optus and the Official Receiver pay the costs of the appeal and proceedings below.

22 There are 6 grounds of appeal expressed as follows:

1. His Honour the learned trial judge in applying Practice Note CM 6 – Electronic Technology in Litigation of the Federal Court of Australia (Judgment [26] and [33]) and the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Judgment [41]-[54]) did so in circumstances where that document and its implications were not the subject of any argument before him, whereby the Appellant was denied natural justice in being able to propound any argument to deal with those issues, in circumstances where:

(a) the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice in question was not a court proceeding;

(b) the obligation to issue the Bankruptcy Notice was that of the Official Receiver, by herself or her duly authorised delegate, and not the computer system maintained by the Australia Financial Services Administration [sic];

(c) procedural operation of such computer system was not an act of the Official Receiver or a delegate of the Official Receiver.

2. The Learned trial judge ought to have relisted the hearing of the Application in respect of the issues addressed by him in paragraph 1 above.

3. The learned trial judge erred in law in determining that the requirements of s. 41(2) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966, Regulation 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations and the prescribed Form, Form 1, set out in the Schedule to the Bankruptcy Regulations made the attachment of the relevant orders or documents referred to in Regulation 4.01 (1) (b) of the Bankruptcy Regulations was [sic] a matter made essential by the Act and Regulations.

4. The learned trial judge erred in law in determining that the [sic] if there was a defect in the Bankruptcy Notice it was capable of being cured by the operation of s. 306 of the Bankruptcy Notice (Judgment [69] by reference to the consideration in [55]-[68]).

5. The learned trial judge erred in law in determining that the time was not at the time of the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice (Judgment [83] and [84])

6. The learned trial judge ought to have determined that:

(a) the requirement of the attachment of the relevant order (referred to in Regulation 4.01 (1) (b) of the Bankruptcy Regulations to the Bankruptcy Notice by reference to the [sic] s. 41 (2) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966, Regulation 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations and the prescribed Form, Form 1, set out in the Schedule to the Bankruptcy Regulations was a matter made essential by the said requirements.

(b) the provisions of s. 306 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 were not available to cured any defect in the Bankruptcy Notice; (c) the validity of the Bankruptcy Notice in question was to be determined at the time of the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice by the Official Receiver, by herself or her delegate.

23 Optus filed a notice of contention expressed, inter alia, as follows:

3. The First Respondent contends that the electronic delivery of bankruptcy notices is valid having regard to the Bankruptcy Act and Bankruptcy Regulations without relying on the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth).

4. The First Respondent also contends that the electronic delivery of bankruptcy notices by the Official Receiver is valid having regard to s. 41 of the Bankruptcy Act and s. 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations, as all that is required is that the judgment/order be attached at the time of service rather at the time of issue.

24 The Official Receiver filed a notice of contention in broadly similar terms.

THE PARTIES’ PRINCIPAL ARGUMENTS

25 Essentially, the parties’ arguments on appeal were a re-run of their arguments below, but with additional submissions concerning the Electronic Transactions Act. Curtis submitted that s 41(2), reg 4.02 and Form 1 required a copy of the final judgment or order to be attached to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue – that time being the administrative act of the Official Receiver generating the bankruptcy notice and emailing it to Optus. Curtis submitted that as the bankruptcy notice did not have attached to it a copy of the relevant final judgment or order at the time of issue, it breached an essential requirement. Curtis relied on Walsh v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 156 CLR 337 (Walsh v DCT) at 340 to contend that the validity of the bankruptcy notice must be determined as at the time of issue, and that as it was defective at the time of issue in a matter made essential by the terms of the Act, or it was defective because it could have reasonably misled the debtor as to what was necessary to comply, then the notice was a nullity (Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988) 165 CLR 71 (Kleinwort) at 79). Accordingly, s 306(1) of the Act could not ‘cure’ the alleged failure to attach the final judgment or order. Curtis also contended that s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) (AIA) did not assist to cure the defect.

26 Curtis also argued that the primary judge’s reliance on the Court’s Practice Note CM 6 – Electronic Technology in Litigation issued on 1 August 2011 and the Electronic Transactions Act denied him procedural fairness, as these materials were not referred to by the parties below.

27 Optus contended that at the time of issue, the bankruptcy notice had attached to it an electronic copy of the final judgment or order, alternatively that the electronic attachment of the final judgment or order by email was substantially compliant with reg 4.02(2). Accordingly, the bankruptcy notice complied with the Act and the Regulations. Alternatively, Optus put that if the alleged failure to attach was found to be a defect, then it was a formal defect or irregularity as the debtor could not have been misled. The defect was thus curable by s 306(1) as no substantial injustice was caused (Prudential-Bache Securities (Australia) Ltd v Warner [1999] FCA 1143 (Prudential-Bache)). In the alternative, Optus adopted the reasoning of the primary judge that the electronic delivery of the bankruptcy notice was validated by reason of ss 8 and 11 of the Electronic Transactions Act. In the further alternative, Optus contended that in any event there was no requirement for a copy of the judgment to be attached to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue.

28 The Official Receiver adopted the submissions of Optus. It submitted that reg 4.01 did not require the Official Receiver to attach the final judgment or order when issuing the bankruptcy notice. It submitted that reg 4.02 only deals with the form and content of the notice, rather than requiring any attachment of a final judgment or order to the notice. Counsel for the Official Receiver also referred to reg 16.01 of the Regulations, regarding the sending of documents by electronic transmission, as supporting validity.

Must a copy of the judgment be attached on Issue?

29 In our view, attaching a copy of the final judgment or order to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue was a requirement of s 41(2) and reg 4.02(2).

30 It is appropriate to begin with some general observations relating to the significance of the final judgment or order in this context.

31 First, the final judgment or order on which the bankruptcy notice is based is a foundational element. So much is made plain by ss 41(1) and 41(3) which stipulate it as a necessary condition to the issue of the bankruptcy notice by the Official Receiver. Paragraph 40(1)(g) also reinforces the point in describing the relevant act of bankruptcy. The statutory language requires identification of the judgment as a condition of issue. The act of bankruptcy has the judgment as its fundamental substratum. Moreover, the steps that a debtor might take to extend the time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice or to set it aside first requires identification of the final judgment or order.

32 Second, and relatedly, the Official Receiver’s administrative act in issuing a notice requires an identified final judgment or order. In the absence of attaching the final judgment or order, the identification of the foundation of the administrative act by the Official Receiver in issuing the bankruptcy notice would not be able to be adequately ascertained.

33 Third, Form 1 is not comprehensible without a copy of the final judgment or order being attached. On its face, and without the final judgment or order being attached, it would not provide to the reader, including the debtor, details of the principal debt. A reader of the notice at the time of issue, including the debtor, could not make sense of the notice without such an attachment to work out the debt relied upon. One purpose that a bankruptcy notice must serve is to convey to the debtor how the debt that is alleged to be owing is said to have arisen (see Kyriackou v Shield Mercantile Pty Ltd (2004) 138 FCR 324 at [38] per Weinberg J). Further, the bankruptcy notice would not enable the reader, including the debtor, to take the steps referred to in paras 4 and 5 on the second page of Form 1, if the information set out in the notice was the only available information.

34 Generally, in our view, the features referred to at [7]-[8] above demonstrate the significance of identifying the final judgment or order and the necessity to attach it to the notice at the time of issue.

35 There are many authorities that refer to the importance of attaching a copy of the final judgment or order at the time of service (see for example Thompson v Metham [1999] FCA 935 at [26] per Katz J; Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Horvath (1999) 161 ALR 441; [1999] FCA 143 at [12]-[14] per Finkelstein J; Re Scerri (1998) 82 FCR 146 at 149 per Beaumont J and American Express International Inc v Held [1999] FCA 321 at [14] per Kenny J). The parties did not contest that such was an essential requirement at the time of service, and that it had been satisfied in the present case. Rather, the respondents to the appeal submitted that it was not a requirement at all (let alone essential) at the time of issue, a submission which may on one view have been accepted by the primary judge (see at [72]-[84]) although the matter is unclear. We disagree with the respondents’ contention.

36 The validity of the bankruptcy notice is to be assessed at the time of issue (see Walsh v DCT at 340 per Gibbs CJ). As his Honour said, “the notice must be understood as speaking as at the date of its issue”. What was required at this time?

37 Subsection 41(2) requires that the notice must be in the form prescribed by the Regulations. Subregulation 4.02(2) provides that the bankruptcy notice “must follow Form 1 in respect of its format (for example, bold or italic typeface, underlining and notes)”. Nevertheless, reg 4.02(3) indicates that only substantial compliance is necessary.

38 First, reg 4.02(2) contains a mandatory requirement in relation to the notice’s “format”. Format is a reference to visual appearance and layout. Examples are given as to format such as “bold or italic typeface, underlining and notes”. The examples given are not limiting. In our view they include the stipulation or requirement for particular attachments, contrary to the submissions of the respondents; Adams v Lambert (2006) 228 CLR 409 (Adams v Lambert) at [11]-[14] arguably makes this plain. We cannot see why the prescription for attachments is not addressing visual appearance and layout. Moreover, when reg 4.02(2) states that a notice “must follow Form 1”, we would have thought that a natural reading would also include following Form 1 in terms of the necessary attachments. In any event, putting to one side the question of “format”, s 41(2) is expressed more broadly in any event. In our view, for the bankruptcy notice to “be in accordance with the form” embraces what the form requires as necessary attachments.

39 Second, in our view, the attachments that are required form a necessary part of the notice and are to be read together with the notice. So much is apparent from the consideration of the interest calculation attachment in Adams v Lambert at [11]-[14]. A fortiori in relation to the attachment concerning the fundamental substratum of the notice i.e. the final judgment or order.

40 Third, the earlier form of notice under the previous regulations originally required details of the judgment to be stipulated on the face of the notice. This was altered to the present requirement to deal with the identification by way of attachment. Now there is little doubt that the previous stipulation was mandatory. We do not glean any legislative intention at the time of the change in form to diminish the significance of the identification of the final judgment or order at the time of the issue of the bankruptcy notice. Lee J in Australian Steel Company (Operations) Pty Ltd v Lewis (2000) 109 FCR 33 (Australian Steel Company) at [51]-[69] discussed such changes and queried whether the copy judgment needed to be attached at the time of issue, but he left the matter open (see at [72]-[75]). Lee and Gyles JJ were in dissent, although the High Court in Adams v Lambert ultimately preferred their approach, but on other aspects not relevant to this precise question.

41 Fourth, if it be accepted that attaching a copy of the judgment or order to the bankruptcy notice is mandated at the time of service (see the authorities referred to at [35]), we do not see why such a requirement is not mandated at the time of issue; s 41(2) and reg 4.02(2) both speak at the time of issue. In other words, whatever statutory provision dictates this mandatory requirement at the time of service also dictates this at the time of issue.

42 Generally, in our view, a copy of the judgment was required to be attached at the time of issue. We will elaborate on whether the requirement was essential when we later address s 306.

Was a copy of the judgment attached at the time of issue?

43 There are several matters to consider in the present case. What was the time of issue and what constituted the act of issue? Further, at that time, was a copy of the judgment attached?

44 The concept of “issue” requires an external act in the nature of a sending out or delivery. It is required to be more than just the internal decision making process or internal acts of the issuer (see Prudential-Bache Securities at [18]-[19] per Emmett J; Nash v Thomas (2012) 204 FCR 415 at [26] per Finn J and Circle Credit Co-Op Ltd v Lilikakis (2000) 99 FCR 592 at 593 per Heerey J).

45 In our opinion, the sending of the 25 February 2014 email with the various attachments was the act that culminated in the issue of the bankruptcy notice. Physical sending or delivery could have constituted the act of issue. But in the present case such acts were constituted electronically.

46 No party contended that electronic sending or delivery could not constitute an act of issue. Rather, the contention of Curtis was that there had not, using such an electronic mode, been the necessary attaching of a copy of the judgment to the bankruptcy notice. As to the electronic communication via email, we do not need to consider whether the issue was the sending of the email or its receipt. As the communication would have been almost instantaneous, there is little difference for present purposes.

47 The real issue between the parties turned upon the question as to whether a copy of the judgment was attached to the bankruptcy notice by such a copy being one of the attachments to the email, along with the notice and the accompanying letter. Clearly, all 3 documents were attached to the email. The question was whether 2 of the 3 pdfs could be considered as being attached to each other for the purposes of compliance with reg 4.02.

48 First, it seems to us that reg 16.01 arguably permitted the issuing of the bankruptcy notice by electronic transmission. To the extent that the primary judge held that the Act and the Regulations did not envisage such a mode, we do not agree (see at [6], [31]-[40]); in fairness to his Honour, it remains unclear to us whether this regulation was drawn to his Honour’s attention. Now reg 16.01 refers to a document being given or sent, but does not expressly refer to issuing. However, as we have said, issuing requires an external act such as a giving or sending. Accordingly, in our view reg 16.01 arguably applies. But of course, reg 16.01 does not itself answer the question of attachment, that is, whether if an electronic mode is used, what the concept of attachment or attaching is to be taken as embracing in that context.

49 Second, even absent reg 16.01, the Electronic Transactions Act permitted the issuing of the bankruptcy notice by electronic means (see ss 3(b), 5, 8, 9 and 11). His Honour referred to these provisions in his reasons (see [41]-[54]), although apparently the parties did not draw them to his Honour’s attention and he heard no argument thereon. Curtis, in grounds of appeal 1 and 2, complains of a lack of procedural fairness. We do not accept this given the appellant’s right of appeal and that this is essentially a legal question. But even if the complaint has validity, we are in the position of being able to deal with the provisions of the Electronic Transactions Act for ourselves (s 28 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)); we have heard full argument from the parties. But like reg 16.01, the provisions of the Electronic Transactions Act do not greatly assist. They provide generally that using an electronic mode is permissible and that invalidity does not flow from using such a mode. But such provisions do not directly assist in answering the question as to whether the required attachment has occurred. The specific requirement for attachment in reg 4.02 and Form 1 is not addressed in the general provisions of the Electronic Transactions Act.

50 His Honour (at [24]) dealt with the question of “attached” by referring to various dictionary definitions. The Oxford English Dictionary gives various meanings to the transitive verb, being:

“To tack on; to fasten or join” (item 5a)

“To connect or join on functionally” (item 6a)

Further, “attached” does not necessarily mean physically fastened (Stroud’s Judicial Dictionary of Words and Phrases (8th ed, Sweet and Maxwell, 2012) at p 239). His Honour in this context also referred to Practice Note CM 6, although we do not find this of much assistance in the present context.

51 The question is whether the pdf of the copy judgment could be treated as “attached” to the pdf of the bankruptcy notice, both being attached (together with the letter) to the email. Now clearly they were both attached to the email. The question is whether they were attached to each other. In our view, they were so attached. They were attached to the same email and electronically proximate to each other. Both were sent together rather than separately. Moreover, the one electronic communication (the email and attachments) was not divisible electronically at the time of issue or immediate receipt. Later, of course, one could choose to separately open each pdf and print hard copies separately. But at the time of electronic issue, the bankruptcy notice and the copy judgment or order were together and not separated. In one sense they were electronically “glued” together. They were electronically “fastened” to each other. Short of the two documents being constituted in the one pdf, they were as close electronically as they could be. Further, if they had been constituted in the one pdf, then it might have been argued that they were one and the same document, rather than being a notice with an attachment. Moreover, the fact that each pdf was itself attached to the email does not entail that each pdf could not also be attached to each other.

52 It was put that as the accompanying letter was also attached to the email in a separate pdf, that the above reasoning might suggest that the letter was attached to the bankruptcy notice. In one sense it may have been, but that did not invalidate the bankruptcy notice; that was not a defect, alternatively s 306(1) would apply to cure such a formal defect or irregularity. In any event, such an argument does not appear to have been run below.

53 In summary, in our view, at the time of issue the copy judgment was attached to the bankruptcy notice. That conclusion is sufficient to dispose of this appeal.

Has there been substantial compliance in any event?

54 Alternatively, even if the copy judgment was not, strictly speaking, attached, reg 4.02(3) makes it plain that strict compliance is not required. Substantial compliance is sufficient (see s 25C of the AIA and also Bank of Melbourne Ltd v Hannan (1997) 78 FCR 249 at 251-252 per Northrop ACJ, Trustees of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary v Weir (2000) 98 FCR 447 at [16] per Beaumont, Burchett and Hely JJ and Australian Steel Company at [88] per Lee J and [110]-[111] per Gyles J).

55 In other words, the mandatory obligation of reg 4.02(2) only requires substantial compliance. If there has been substantial compliance, then there is no defect and, accordingly, s 306(1) does not then need to be considered.

56 To the same effect, one could also argue, as an anterior point to any consideration of regs 4.02(2)-(3), that the words “in accordance with” in s 41(2) as distinct from just the word “in” permits of some degree of flexibility, so that only substantial compliance with the form is required. And if this is accepted, one never gets to reg 4.02(3) (see Farrugia v Farrugia (2000) 99 FCR 16 at [61]-[68] per Katz J). But for present purposes, it matters little which route is used. The short point is that only substantial compliance is required.

57 In our view, even if it is said that the copy judgment was not strictly attached to the notice at the time of issue, nevertheless there has been substantial compliance. The act of issue electronically delivered the copy judgment together with the bankruptcy notice. It is as if two documents had been physically handed over the counter and it being said “here is the bankruptcy notice with the copy judgment referred to”. They were electronically together. Indeed, the only way they could have been closer, electronically, is for one pdf to have been used or, perhaps, for the bankruptcy notice to embody a hyperlink to the copy judgment. The latter course would be problematic for 2 reasons. First, it would change the face of Form 1. Second, on service of the physical notice, there would be absent the physical attachment; hyperlinks are only relevant in an electronic medium. As to the one pdf question, in our view, using two pdfs rather than one pdf is substantial compliance. We do not see a substantial difference between using two pdfs rather than one pdf; indeed, as we have said, it might be said that if you had used only one pdf, then you would have had only one document and not a notice with the copy judgment attached. As we have said earlier, there has been literal compliance. But if we are wrong, in our view there has been substantial compliance. Accordingly, the bankruptcy notice is valid without any need to rely upon s 306(1).

Does section 306(1) otherwise apply if there is a defect?

58 Given our conclusions, we do not strictly need to express a view concerning the application of s 306(1). But in deference to the parties’ arguments and given that the primary judge dealt with the application of s 306(1), we will express our views, briefly.

59 In our view, and contrary to the respondents’ submissions and the view of the primary judge, if the copy judgment was not attached to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue and there had not been substantial compliance, then the bankruptcy notice would be a nullity. The defect or irregularity would not be cured by s 306(1).

60 What is a “formal defect or irregularity” in a bankruptcy notice for the purpose of s 306(1)?

61 A defect is substantive and not formal if the defect is such that the bankruptcy notice fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Act (Kleinwort at 79 per Mason CJ and Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ). In such a case, the notice is a nullity.

62 What is a requirement made essential by the Act? In order to determine that question, one needs to consider the legislative purpose of the Act generally, the purpose of the provisions relating to bankruptcy notices, the purpose of the particular requirement and whether it was the legislative purpose that failure to comply with such a requirement should necessarily invalidate the bankruptcy notice. Further, one needs to evaluate the significance or importance of the defect in the circumstances of the case (Adams v Lambert at [26]-[29]).

63 Generally, it seems to us that the attaching of a copy of the judgment or order to the bankruptcy notice at the time of issue is essential. We have set out the significance of the judgment as a foundation for the issue of the notice and the significance of the judgment debt being properly identified (see [31]-[34]). Further, the authorities referred to at [35] demonstrate such a requirement to be essential at the time of service. Equally, we would consider that the requirement is essential at the time of issue, for that is when validity needs to be assessed. Not to have the copy judgment so attached at the time of issue entails that the foundation for the notice and the basis for the administrative act of issue has not been properly identified. Moreover, the notice on its face would be incomplete and uncertain in an essential respect.

64 There is another reason why s 306(1) does not apply.

65 A defect is substantive and not formal if the defect is reasonably capable of misleading the debtor (Kleinwort at 79 per Mason CJ and Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ). In our view, not to attach a copy of the final judgment or order at the time of issue is reasonably capable of misleading the debtor. Validity in this respect is to be determined at the time of issue, not just at the time of service. The fact that the debtor may not have been actually misled, because it was in fact attached at the time of service, but not at the time of issue, is not to the point.

66 At the time of issue, without the attachment, a reader, let alone the debtor, could not know from the face of the notice what the basis of the debt was, the basis of the administrative act of issue by the Official Receiver or the steps that the debtor could take as identified in paras 4 and 5 on the second page of the notice. By having the identity of the debt and, as a consequence, the subject matter of the notice open, uncertainty is created about the basis of the notice and the steps that might be taken in terms of necessary steps to set aside the judgment or to set up a counterclaim that could not have been set up in the action leading to the judgment; something which is uncertain is capable of misleading (cf Kleinwort at 80).

67 For the above reasons, if there was a defect in not attaching a copy of the judgment to the bankruptcy notice and there was not substantial compliance as envisaged by reg 4.02(3), then such a defect would not be cured by s 306(1).

Conclusion

68 In summary, the bankruptcy notice is valid. The bankruptcy notice, albeit electronically created and issued, had attached to it a copy of the relevant judgment at the time of issue; alternatively, there was substantial compliance with that requirement. No question under s 306(1) arises.

69 The appeal will be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding sixty-nine [69] numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Mansfield, Gleeson and Beach. |

Associate: Dated: 30 October 2014