FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

BlueScope Steel Limited v Gram Engineering Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 107

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 26 August 2014 |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties file within 14 days short minutes of orders disposing of the appeal and cross-appeal, and dealing with the costs of the appeal, or in the absence of agreement, short submissions.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1141 of 2013 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) Appellant GRAM ENGINEERING PTY LTD (ACN 002 193 311) Cross-Appellant |

| AND: | GRAM ENGINEERING PTY LTD (ACN 002 193 311) Respondent BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) Cross-Respondent |

| JUDGES: | BESANKO, MIDDLETON AND YATES JJ |

| DATE: | 26 August 2014 |

| PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BESANKO AND MIDDLETON JJ:

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

1 The appellant and cross-respondent, BlueScope Steel Limited (‘BlueScope’) is a well-known manufacturer of flat steel products in Australia. It is now a separate company, but was previously a division of BHP Billiton Limited, and operated under the name, John Lysaght (Australia) Pty Ltd.

2 The respondent and cross-appellant, Gram Engineering Pty Ltd (‘Gram’) produces and sells steel fencing panel sheets which are used primarily for backyard privacy fencing in homes throughout Australia. Gram sells its fencing panel sheets in competition with BlueScope.

3 Historically, a vexing problem for manufacturers of fence sheeting was how to design fencing that looked the same regardless of which side it was viewed – that is, it did not have a bad side.

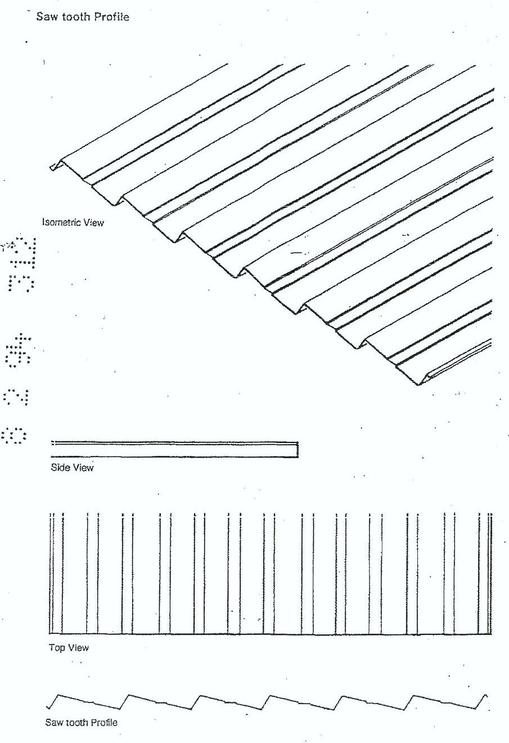

4 In 1993, Mr Mann, Managing Director of Gram, came up with a design of a fencing sheet with what has come to be called a sawtooth or zig-zag profile with six repeating pans or units (‘the Design’), which dealt with the so called good side, bad side problem as it looked the same from both sides.

5 Pursuant to the Designs Act 1906 (Cth) (‘the Act’), Gram applied for registration of the Design on 8 February 1994, which was registered on 26 August 1994 (‘AU 121344S’) and expired 16 years later on 8 February 2010.

6 The fencing panel sheet was manufactured by Gram substantially in accordance with the Design on or about 12 September 1995 and was sold under the name ‘GramLine’.

7 The GramLine fencing sheet was very successful commercially. By 2002, the GramLine range commanded 35-40 per cent of the Australian market for fencing panel sheets.

8 In 2002, BlueScope launched its own symmetrical six-pan sawtooth fencing panel under the name ‘Smartascreen’.

9 In 2011, Gram commenced proceedings against BlueScope claiming under s 30(1)(a) of the Act that the Smartascreen was either an ‘obvious’ or ‘fraudulent imitation’ of the Design. BlueScope, by cross-claim, challenged the validity of the Design pursuant to s 17 of the Act. The infringement and invalidity claims fall to be determined under the Act rather than the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (‘the New Act’): see ss 150, 151(3) and 156(3) of the New Act.

10 The primary judge in Gram Engineering Pty Ltd v Bluescope Steel Limited [2013] FCA 508 upheld the validity of the Design and found that the Smartascreen applied an obvious imitation to the Design. The primary judge further held that there was insufficient evidence to support a finding of fraudulent imitation.

11 BlueScope appealed this decision challenging certain findings the primary judge made in the context of validity and his conclusion that the Smartascreen product was an obvious imitation of the Design. Gram, by cross-appeal, challenged the primary judge’s finding that the Smartascreen product was not a fraudulent imitation of the Design.

12 For the reasons below, the appeal and cross-appeal should be dismissed.

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS

13 As the parties are challenging many of the findings of fact made by the primary judge, we make a few preliminary observations on the role of appellate courts in this situation.

14 The task of an appellate court when there is dispute over the primary judge’s findings of fact is complex and involves balancing a number of considerations.

15 There is often a relative disadvantage in an appellate court in attempting to assess matters of degree and impression as compared to a trial judge. The degree of deference to be given to a primary judge’s findings will vary to the extent that the trial judge has a relative advantage over an appellate court.

16 There is a real danger where much turns on findings of fact, that without proper restraint, appeals would be treated as an opportunity to simply have another attempt to re-run the trial. This should not be allowed to occur.

17 Where factual findings are reasonably open, an appellate court is not justified in setting those findings aside because the appellate court merely differs from the trial judge’s view of those facts. Nevertheless, the Court also has a constitutional duty to reach its own conclusions on factual matters, and not shrink from giving effect to them.

18 These considerations, amongst others, were mentioned in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (2011) 197 FCR 67 at 77-80 [25]-[35].

19 These principles are particularly relevant in this case, as the primary judge made a number of findings of fact based upon his assessment of the evidence and impression of the witnesses. It is primarily against those findings of fact both parties appeal or cross-appeal.

20 As will become apparent, we have concluded that the primary judge was correct in his ultimate findings of fact, and we can find no material error in his application of the relevant principles of law.

SCOPE OF MONOPOLY

21 The primary judge’s conclusion that the Design was valid was not challenged by BlueScope on the appeal. However, the primary judge’s assessment of the significance of the prior art was challenged on the appeal as part of BlueScope’s challenge to his Honour’s conclusion that BlueScope’s Smartascreen product infringed the Design. BlueScope submitted that the primary judge’s conclusions as to the scope of the monopoly which he had reached by reference to the prior art were incorrect and that that led his Honour to conclude erroneously that BlueScope’s Smartascreen product infringed the Design.

22 The connection between the scope of the monopoly protected by a registered design, including questions of novelty and originality on the one hand and questions of infringement on the other, has been discussed in a number of cases. The principles are not controversial and it is sufficient to refer to the following observations of Lockhart J in Dart Industries v Decor Corporation (1989) 15 IPR 403 (‘Dart Industries’) at 409:

The scope of a registered design must be determined with reference to the background of the prior art at the priority date and questions of infringement and novelty or originality are connected. In Hecla Foundry Co v Walker, Hunter & Co (1889) 14 App Cas 550 Lord Herschell said at 555: “… one may be able to take into account the state of knowledge at the time of registration, and in what respects the design was new or original, when considering whether any variations from the registered design which appear in the alleged infringement are substantial or immaterial.”

Where novelty or originality is discovered in slight variations, there cannot be infringement without a very close resemblance between the registered design and the article alleged to be an infringement of the design. Lloyd-Jacob J in Rosedale Associated Manufacturers Ltd v Airfix Products Ltd [1956] RPC 360 at 364 said that the court would have regard to what was “known and old”, and: “… if the particular features which provide a novel conception have not been reproduced in the alleged infringement, the similarity of appearance between the article complained of and the registered design if present must necessarily reside in the common possession of characteristics which are free to everybody to employ.” See also Macrae Knitting Mills Ltd v Lowes Ltd (1936) 55 CLR 725 per Dixon J at 731 and L J Fisher & Co Ltd v Fabtite Industries Pty Ltd (1978) 49 AOJP 3611 per Fullagar J at 3620.

23 As we discuss later, in the context of validity, the primary judge found that the dominant visual features of the Design were the six modules or pans and the amplitude, wavelength and angles: at [202]-[212]. When he came to consider infringement, the primary judge found that BlueScope’s Smartascreen product had these visual features: at [324].

24 In challenging the primary judge’s conclusion on infringement, BlueScope challenged his conclusion as to the dominant visual features of the Design. It challenged his conclusion that the Design showed a vertical orientation for the fencing sheet and submitted that it showed no particular orientation. It challenged his assessment of the prior art and the significance he placed on the fact that there were six modules or pans. As counsel for BlueScope put it at one point, a proper assessment of the prior art would have meant, ‘the sixness [i.e., the presence of six pans] of itself is going to retreat into the background’.

25 In those circumstances, it is necessary to consider carefully the primary judge’s reasons with respect to validity.

The judgment below

26 The primary judge approached the challenge to the validity of the Design in the conventional way by first construing the Design and then making findings as to what made it new or original as compared to the prior art base. There seemed to be no significant dispute as to the principles of law to apply, including the interpretation of s 17 of the Act.

27 The Design representations which accompanied the registration were as follows:

28 The primary judge first dealt with the overriding principles of construction of a design (at [200]-[204]):

(a) a design is the mental picture of a shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation of the article to which it is to be applied;

(b) construction is a question of fact for the Court to determine by the eye alone;

(c) expert evidence may be led to assist the Court;

(d) the Court is to apply an ‘instructed eye’ to the design - that is the Court must be made aware of the characteristics of the article to which the design is applied, and the manner in which such articles would normally be found in trade, commerce and in use; and

(e) however, considerations of utility have no relevance to the proper construction of a design.

29 Applying those principles and in light of the expert evidence led, the primary judge found that the primary feature was the sawtooth pattern consisting of six identical repeating pans, oriented vertically. The sawtooth pattern was the product of the unique proportions of the wavelength, amplitude and angles of each sawtooth module: see [202]-[212.

30 The primary judge held that the zig-zag within the zig-zag or stiffener, that is the feature in the centre of each pan, was a secondary feature. Likewise, the flanges at the end of the sheet, as they would not be visible when applied to a fencing panel sheet because the flanges overlap at each end with the flanges of adjacent panels: see [217]-[220].

31 The Design was embodied in the GramLine sheet except that the stiffener was more prominent in the GramLine sheet, and the stiffener was oriented in the opposite direction (which can be understood by looking at the sawtooth profile design representation) to the Design: [221]-[222].

32 The primary judge then turned to assessing the novelty or originality of the Design.

33 The primary judge first looked at the text of s 17 of the Act which states that a design must not be registered unless it was ‘new or original’, and then to the principles established by case law for ascertaining novelty and originality. The principles distilled by the primary judge were (at [231]-[239]):

(a) there must be something special or distinctive about the appearance which captures and appeals to the eye;

(b) there must be substantial novelty having regard to the nature of the article to which the design is to be applied;

(c) in determining whether a design is new or original involves a comparison between the design and the prior art as necessary;

(d) it is not possible to define the degree to which the design must differ from the prior art – it is a question of fact for the Court to determine;

(e) one must look at the prior art and the design as a whole when comparing them – the question is whether an article made in accordance with the design would be substantially similar to an article made in accordance with the prior art; and

(f) novelty and originality, like construction, is to be decided by applying the ‘instructed eye’.

34 BlueScope presented 10 examples of the prior art at trial which it submitted challenged the novelty and originality of the GramLine sheet.

35 Applying his construction of the Design, the primary judge held that if each of the items of prior art were applied to a fencing panel sheet, they would have a different appearance to the Design. The reasons were that when vertically oriented (as he had construed the Design), the sheeting looked the same regardless of which side it was viewed and none of the prior art had this feature; none had the same combination of six pans with the proportions and angles of the Design; the prior art had features intended to perform specific purposes for the articles to which those designs related (e.g. cladding, siding, roofing); and none had a sawtooth within a sawtooth feature: see [244]-[259].

36 The primary judge then dealt with ss 17(1)(a) and 17(1)(b).

37 The primary judge interpreted s 17(1)(a) as being concerned with designs in respect of articles where the design differs in immaterial details or common trade features from a design in respect of ‘the same article’. The primary judge decided that the words ‘the same article’ in s 17(1)(a) were intended to distinguish it from s 17(1)(b) which deals with ‘any other article’: see [263]. In essence, s 17(1)(a) involved a comparison with prior art that was intended to be applied to fencing panels, whereas s 17(1)(b) involved a comparison with any other articles.

38 The primary judge held that with respect to s 17(1)(a), the only piece of prior art that made any reference to fencing was the so-called design 23 which was ‘devised particularly as a roof sheet but it may have other application such as a wall or fence sheeting’ (see [72], [264]).

39 Then, applying the principles of novelty and originality, the primary judge held at [260] ff that with respect to s 17(1)(a) the Design was new or original. The primary judge’s reasons were:

(a) design 23 was not a publication in respect of an article of fencing sheeting. It focused entirely upon roofing: [265];

(b) the Design did not differ from the prior art only in immaterial details ‘or features commonly used’ in the trade – the shape configuration and pattern of the Design captured or appealed to the eye and was special and distinctive: [266]-[268];

(c) it was well established that a design made up entirely of features found in the prior art may be new or original provided that those features have been combined so as to produce a design that has a sufficiently distinctive appearance: [269]-[272]; and

(d) there was no evidence that the prior art was used on fencing panel sheets before the priority date of the Design: [276].

40 The primary judge then dealt with s 17(1)(b). BlueScope relied on a number of designs for sidings and roofing in this regard: see [76]-[83].

41 The primary judge noted that there were two approaches to interpreting s 17(1)(b) based on whether patent law principles of ‘obviousness’ were incorporated within it.

42 The two tests are the ‘Ricketson test’ and the ‘Lahore Test’ as described by Allsop J (as his Honour then was) in Mining Equipment Pty Ltd v Mining Supplies Australia Pty Ltd (2001) 52 IPR 513 at [51] and [58]-[59]:

(a) the Ricketson test (or the patent test) is whether the adaptation would be obvious to a skilled but unimaginative craftsman possessed of the common general knowledge in the field and faced with the task of conceiving a design to apply to a particular article; and

(b) the Lahore test (or the visual test) is that a claim of novelty or originality may fail either because (i) the shape has already been applied to the article, or (ii) because the shape has already been applied to an article of ‘analogous character’.

43 The primary judge applied both tests and found that under the patent approach, the evidence did not establish that there was any designer in the field, interested in the area of fencing panel sheets, who had any knowledge of the sawtooth shaped Design before its priority date. Similarly, under the visual test there would be no difference because even if any of the items of prior art were to be applied to a fencing panel sheet, the resulting design would have had a different visual appearance from that which is the subject of the Design: see [289]-[306].

44 Consequently, the Design satisfied the requirements for novelty and originality pursuant to s 17(1)(b).

Consideration

45 As we have said, BlueScope has challenged the primary judge’s findings primarily in relation to the construction of the Design and the application of that construction when comparing the Design to the prior art. These two considerations overlapped in the presentation of argument.

46 The construction of the design was for the Court to determine, with the aid of expert evidence. The design was to be looked at with an ‘instructed eye’. When construing the design with an ‘instructed eye’, consideration needs to be given to the manner in which the article to which the design is applied would normally be found in trade, commerce and in use: see Firmagroup Australia Pty Ltd v Byrne & Davidson Doors (Vic) Pty Ltd (1986) 11 FCR 415.

47 The primary judge, in interpreting the Design, adopted this approach. We specifically do not accept the submission of BlueScope that the primary judge construed the Design by reference to one particular use. The primary judge, as we will endeavour to explain, determined the scope of the Design by looking at the design representations made in context. BlueScope have disclosed no error of the primary judge in this regard.

48 We now turn to the specific errors said to be made by the primary judge in his construction of the Design and application of s 17. As we have indicated, to a large extent these issues overlapped, and the primary judge’s approach to infringement followed upon his construction of the Design.

Orientation of the design

49 The primary judge’s findings were that the instructed eye reading the Design would understand that it was for a vertical infill sheet which was to fit in a frame with posts and rails: at [202]; and therefore that the sawtooth pans run vertically down the face of the sheet: at [245].

50 BlueScope contended that this construction is impermissible and has the effect that fencing panels supplied for use horizontally with a modified post and rail system would not infringe the Design.

51 While considerations of utility are not relevant, designs cannot be construed without context. It is often the case that features of the article to which the design applies, will serve both visual and functional purposes. Where this is the case, the implication of BlueScope’s submission is that the feature’s appearance and utility must be divorced. However, a design without context is a meaningless drawing. As Lockhart J observed in Dart Industries 15 IPR 403 at 408, the design is ‘the mental picture of the shape, configuration, pattern, or ornament of the article to which it has been applied’ (emphasis added). It is inescapable that the Design is for sheet metal fencing and the construction of the Design must reflect this.

52 There was argument about the symmetry of the sheeting. The sheeting has a two-fold (that is the object appears the same after 180- and 360-degrees of rotation) rotational symmetry about an axis parallel to the grooves but no rotational symmetry about an axis perpendicular to the grooves.

53 The symmetry is the result of the flanges at the end of each panel and the fact that the success of GramLine was in part due to the fact that the fence had no bad side – that is it looked the same regardless of what side you looked at it.

54 These features affect both the appearance and function of the article to which the Design is applied. It is undeniable that when oriented horizontally, the utility of the article is compromised in that the flanges act as a join between two sheets and the stiffener provides rigidity when oriented vertically. However, crucially, for present purposes, the appearance of the Design changes.

55 These two features have a completely different effect on the appearance of the Design if oriented horizontally and used as fencing sheets, and lead to the conclusion that the pans were vertically oriented. It was entirely open for the primary judge make this finding and we see no error in this conclusion.

Number of repeating pans

56 BlueScope submitted that the primary judge erred in his finding that the number of repeating pans would necessarily make an important contribution to the overall appearance of the Design.

57 BlueScope also submitted that the primary judge ought to have had regard to the potential for the prior art to be repeated to achieve six pans.

58 The evidence below was that the prior art had no articles with six pans: see [3], [64]-[83]. Furthermore, the experts agreed that changing the number of pans per width affects the visual appearance: [214]-[215] and [306].

59 In essence, a six-pan design is inherently different to a two-pan design, in that it has four more pans. By joining three two-pan sheets in order to compare it to a six-pan design, one is comparing three articles of one two-pan design joined together, and, one six-pan article. This is not comparing the prior art as registered, used or published as required by the Act.

60 In addition, while there are no dimensions in the Design, the instructed eye would be aware of industry practice concerning the size of the sheeting, and consequently, a two-pan design of the same size of a six-pan design would appear different.

61 It follows from the above that we see no error in the primary judge’s reasoning in this regard.

The combination of amplitude, wavelength and angles

62 BlueScope submitted that the primary judge erred when finding that the particular combination of amplitude, wavelength and angles gave the Design novelty or originality over the prior art.

63 The combination of the amplitude, wavelength and angles create the sawtooth effect. While the primary judge found that design 4 had some degree of similarity to the Design (at [79]), the primary judge also found that the angles were different ([257]) and that this affected the appearance. A side-by-side comparison bore this out. Other designs did not have the rotational symmetry discussed above, which affected the appearance of the design.

64 As a result, the primary judge has not erred in this regard.

Sawtooth within a sawtooth

65 The primary judge decided that this was a secondary feature based on his own impression and the expert evidence (from both parties’ experts) that it had less visual impact than the sawtooth shape or that it was barely noticeable in the profile view representation.

66 BlueScope challenged this conclusion and submitted that it is a strong visual feature when viewed from the isometric or top view. Furthermore, none of the prior art had that feature although some had a decorative element in the middle of the pan.

67 In our opinion, the primary judge committed no error when deciding that the sawtooth within a sawtooth was a secondary feature. When compared with the other features of the Design, it was of lesser significance and its amplitude is substantially smaller than that of the zig-zag shape of the pan.

Design 23 and section 17(1)(a)

68 We turn specifically now to design 23. Only one article of the prior art made any reference to being used as fencing. Design 23 states that it has been designed particularly as a roof sheet ‘but it may have other applications such as wall or fence sheeting’: see [264]. The primary judge found that this did not amount to a publication in respect of an article of fencing panel sheet as the design focussed entirely upon roofing: [265].

69 We agree with the primary judge’s characterisation of design 23 as not being the ‘same article’ as the Design. Design 23 was designed particularly as cladding and it should be treated as such.

70 Even if we were to disagree with the primary judge in this regard, design 23 differs from the Design in the following ways: it has two pans, does not possess the rotational symmetry, does not have the sawtooth within a sawtooth feature and the flanges at the end of the sheet are manifestly different. These differences are more than immaterial details or features commonly used in the relevant trade.

Conclusion in relation to the scope of the monopoly

71 It follows from the above, the primary judge was correct in his approach to determining the scope of the monopoly.

72 We should also say that when looking at this issue, the Design and the prior art must be looked at as a whole. Breaking down the Design and the prior art into its constituent elements may be helpful in the comparison, but it must not be allowed to obscure the general appearance of the Design and prior art. As the primary judge noted a number of times, the orientation, the number of pans, or modules, and the combination or amplitude, wavelengths and angles of the Design distinguish it from the prior art. In our view, the primary judge correctly applied s 17 of the Act in determining the central question before him of whether the Design was new or original, and correctly described the extent of the monopoly.

INFRINGEMENT

73 We now turn to infringement.

The judgment below

74 Having found that the Design was valid, the primary judge had to then decide if there had been any infringement, and if so, whether that infringement was an obvious or fraudulent imitation.

75 The primary judge discussed the authorities concerning obvious imitation: see [308]-[312].

76 The primary judge also observed that fraudulent imitation differs from obvious imitation in three respects: at [313]-[315]. First, the degree of correspondence between the impugned design and the registered design need not be as close as in obvious imitation. Secondly, fraudulent imitation requires that the application of the design be made with knowledge of the existence of the registered design, or with reason to suspect it. Thirdly, fraudulent imitation must be deliberately based upon the registered design (there is no necessity for changes between the impugned design and the registered design to be made for the purpose of disguising copying).

77 The primary judge then turned to the evidence and found (at [324]) that BlueScope applied an obvious imitation to the Design.

78 The primary judge’s reasons were that the dominant feature of the Smartascreen was the overall zig-zag shape, the GramLine and the Smartascreen could nest (in that they could be stacked on top of each other, albeit imperfectly) and lastly the commercial justification for developing and launching the Smartascreen product was to compete with Gram.

79 A physical sample of the Smartascreen product was in evidence.

80 Below is a photograph of the Smartscreen product, which was also in evidence:

Considerations

81 Based on the primary judge’s construction of the Design, the key question was whether the ridge/valley effect and the microfluting of the Smartascreen product sufficiently set it apart from the GramLine product.

82 There is no need to repeat the relevant law concerning obvious imitation as the primary judge set it out correctly. However, we should point out the key considerations:

(a) an obvious imitation is one which is not the same as the registered design but is a copy that is apparent to the eye notwithstanding slight differences;

(b) the question is one of substance and is looked at by examining the essential features of the design;

(c) it is a visual comparison, and mathematical comparisons or measurement of ratios, (which form no part of the mental picture of the shape or configuration of the design) should not to be applied; and

(d) questions of infringement are not to be determined by a narrow or overly technical approach.

83 BlueScope submitted that the primary judge erred in that he resolved the above issue by deciding which experts’ opinion he preferred.

84 This is an incorrect characterisation of the primary judge’s reasons.

85 The analysis of infringement is binary – Smartascreen either infringed the design of the GramLine sheet or it did not. Given there was expert evidence, it was inevitable that the primary judge was going to prefer the evidence of one over the other when reaching his own conclusion.

86 It is true that the primary judge did compare Mr Wightley’s and Mr Richardson’s expert opinions in this regard at [317]-[323], and he stated that essentially the issue of infringement involves resolving the two expert’s opinions: see [316]. However, immediately following this analysis of their opinions, the primary judge goes on to proffer his own opinion (at [324]):

In my opinion, when the Smartascreen panel is viewed as a whole the dominant visual feature is the repeating sawtooth profile consisting of six pans or modules, and the amplitude, wavelength and angles. These features give it a striking physical similarity to the Design and the GramLine product. This is so notwithstanding the difference in the Smartascreen panel consisting of the ridge/valley effect and the micro-fluting. In my opinion those features are comparatively slight and are not sufficient to detract from the overall visual picture of the Design and the GramLine product which I have described above.

87 The primary judge then explained his conclusion in relation to Mr Wightley and Mr Richardson’s evidence. This approach is considered and methodical and could hardly be dismissed as freeing itself from the responsibility of undertaking its own analysis in accordance with established principle. We see no error in the primary judge’s approach.

88 BlueScope challenged the fact that the primary judge was guided by the fact that the products were nestable.

89 This analysis involves a physical comparison and not a visual test, but this was acknowledged by the primary judge: at [336]. Furthermore, the products do not completely nest: [334]. Nevertheless, the nesting qualities are instructive. As has been discussed at length, the combination of amplitudes, wavelengths and angles create the sawtooth profile. For the GramLine and Smartascreen sheets to nest, albeit imperfectly, they must by logical extension, have similar amplitudes, wavelengths and angles. This is clearly helpful in deciding if Smartascreen is an obvious imitation of GramLine, and it was entirely open for the primary judge to be assisted by the nesting properties of the two articles. It is further relevant because as noted above, an obvious imitation is not one which is the same as the design, but one that is an imitation apparent to the eye notwithstanding slight differences.

90 With respect to the substance of Mr Wightley and Mr Richardson’s evidence, the main difference was the significance of the ridge/valley effect at the rake of the pan and the microfluting. Mr Richardson thought that they were visually very striking and noticeable from all angles (at [318]-[320]), whereas, Mr Wightley thought that while they were noticeable, they were not the most visually dominant feature. The six-pan sawtooth profile was the most visually dominant feature: at [321].

91 The primary judge accepted Mr Wightley’s evidence because he found flaws in Mr Richardson’s methodology (see [325]-[333]). Mr Richardson said that the design could be read either as an overall zig-zag shape or as a repetition of the two forms namely the ridge/valley effect and the microflulting. In cross-examination, Mr Richardson conceded that the appropriate view of the Smartascreen product was in the eye of the beholder. There were only two outcomes open to the primary judge in regard to the characterisation of the Smartascreen product – either that he support the sawtooth profile as the dominant feature, or that it be read as a repetition of the ridge/valley effect with the microfluting.

92 Given the primary judge formed the view that the most dominant visual feature was the six-pan sawtooth profile, it was open for the primary judge to prefer Mr Wightley’s evidence. The primary judge’s view was supported by Mr Wightley as his evidence was that he did not notice the ridge/valley effect until he had the opportunity for a closer examination, and also by Mr Richardson, who in cross-examination conceded that at some angles and under certain lighting conditions, the microfluting was not or barely visible.

93 We agree that the primary judge’s findings that the appearance of the Smartascreen supports a conclusion of obvious imitation. On the basis of the evidence before the primary judge, and his own impression, it was open and in our opinion correct to find that the Smartascreen product was an obvious imitation of the Design.

94 However, the primary judge erred in considering the commercial objectives that BlueScope may have had for developing and launching the Smartascreen product. BlueScope’s commercial objectives do not inform any analysis of the appearance of the Smartascreen sheet. It is a visual comparison between the registered design and the infringing design that is the appropriate way to consider the question of infringement.

95 However, it is clear that commercial objectives did not form a material part of the primary judge’s final analysis.

FRAUDULENT IMITATION

The judgment below

96 Given the primary judge found that the Smartascreen was an obvious imitation, he only briefly dealt with fraudulent imitation.

97 The primary judge stated that fraudulent imitation differed from obvious imitation in three ways as mentioned above: at [76].

98 The primary judge noted that he must be satisfied that some person or persons on behalf of BlueScope deliberately copied the Design, or based the design of the Smartascreen product on the Design: [348].

99 The primary judge had to determine whether the Smartascreen was a fraudulent imitation of the Design without the evidence of Mr Field. Mr Field was a draftsman working in research and development of the predecessor company to BlueScope, Lysaght (which company we will refer to as BlueScope, even though at the time the company was called Lysaght). He was specifically involved in trying to design a symmetrical fencing profile for BlueScope and in an internal memo discussed designing a ‘Gram look alike’: see [96]-[199]. Clearly his direct evidence would have greatly assisted the primary judge. The primary judge found that Gram’s delay in bringing the proceeding had meant that Mr Field was not able to give evidence because of his advanced age and ill health. Therefore, the primary judge had to rely on inferences that could be drawn from documentary evidence and his impression of BlueScope’s other witnesses.

100 The primary judge distilled his investigation into whether there was fraudulent imitation as follows:

348. … I must be satisfied that some person or persons on behalf of Bluescope deliberately copied the Design, or based the design on [sic] the Smartascreen product or [sic] the Design.

349. This requires proof of the requisite degree of knowledge of the Design itself and what amounts to proof of copying. The case is not a straightforward one because it ultimately depends upon the proposition that the combined pressures and instructions communicated by Ms Marlin to the R&D Department brought about a copy of the design.

350. The difficulty is not so much in proof of knowledge, but rather in proof of who (if anyone) actually copied Gram’s Design.

101 The primary judge then considered carefully the evidence of Ms Marlin, Mr Seccombe, Mr Gallaty and Ms Fathinia, who were employees of BlueScope involved in either the Research and Development, or Marketing departments. We will discuss their evidence in more detail below, but the primary judge found there to be insufficient evidence of fraudulent imitation.

Consideration

102 Gram submitted that the primary judge erred in that he required there to be proof of ‘deliberate copying’ to make out fraudulent imitation, and that in any event, the evidence established that there was deliberate copying.

Deliberate copying

103 The primary judge stated (at [373]) that for him to be satisfied of fraudulent imitation, he would need ‘to find that it [the Design] was deliberately copied’.

104 Gram criticises this on the basis that ‘deliberate copying’ imparts an additional requirement of deliberateness into the test for fraudulent imitation.

105 The High Court dealt with fraudulent imitation in Polyaire Pty Ltd v K-Aire Pty Ltd (2005) 221 CLR 287 (‘Polyaire’).

106 With respect to whether deliberateness is a requirement, it is instructive first to look at the submissions of the parties and the true issue before the High Court. Senior Counsel for Polyaire submitted (at 289-290) that:

Fraudulent imitation is established where the author of the accused design knowingly, consciously or deliberately copies or bases his design on the registered design, with the requisite degree of knowledge of the owner’s rights in relation to the design if, by visual comparison, the resulting design is an imitation of the registered design. The trial judge applied that test. [HAYNE J. Does your submission depend on the fraudulent imitation being conscious use?] Yes. [HAYNE J. What use?] Having the design before you, appreciating the features involved in it, and allowing those features to be carried over into the infringing design, at least in a form sufficient that that design is an imitation of those features. (emphasis added)

107 It was on the basis of the need for ‘conscious use’ that the High Court said in Polyaire at 295-296:

17. [T]he application of a “fraudulent imitation” requires that the application of the design be with knowledge of the existence of the registration and of the absence of consent to its use, or with reason to suspect those matters, and that the use of the design produces what is an “imitation” within the meaning of par (a) [s 30(1)(a)]. This, to apply the general principle recently exemplified in Macleod v The Queen, is the knowledge, belief or intent which renders the conduct fraudulent.

18. This construction of par (a) of s 30(1) is consistent with the approach to the term “fraudulent” taken by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Turbo Tek Enterprises Inc v Sperling Enterprises Pty Ltd. Their Honours rejected a submission that it was necessary to show that the alleged infringer had actual knowledge of the fact of registration…

The Full Court held that it was sufficient that the alleged infringer had reason to believe or strongly suspected that an article which it had imported and marketed embodied a design that was registered, or in respect of which an application was pending. (emphasis and citations omitted)

108 It is true that the High Court stated that the infringer did not necessarily require actual knowledge of the registration of the design.

109 However, this only concerns the issue of knowledge of the registration of the design. The issue of the actual imitation of the design needs also to be considered.

110 The High Court in Polyaire at 296-297 cited with evident approval Farwell J in Dunlop Rubber Co Ltd v Golf Ball Developments Ltd (1931) 48 RPC 268 at 279-280. His Lordship dealt with what ‘fraudulent’ meant in the context of fraudulent imitation and contrasted the deliberate intention to steal the property of the owner of the registered design (which is not required for fraudulent imitation), with imitation deliberately based upon the registered design, which is fraudulent imitation.

111 Specifically, the High Court at 297, cited Farewell J as follows:

But fraudulent imitation seems to me to be an imitation which is based upon, and deliberately based upon, the registered design, and is an imitation which may be less apparent than an obvious imitation; that is to say, you may have a more subtle distinction between the registered design and a fraudulent imitation, and yet the fraudulent imitation, although it is different in some respects from the original, and in respects which render it not obviously an imitation may yet be an imitation perceptible when the two designs are closely scanned and accordingly an infringement. (emphasis added)

112 Importantly, the High Court after citing Farwell J, and in upholding the trial judge, indicated that:

Bensanko J [the trial judge] expressly adopted what had been said by Farwell J in Dunlop Rubber. Dunlop rubber had been followed by Morton J in Lewis Falk Ltd v Henry Jacobwitz (1944) 61 RPC 116 and by Jenkins J in W H Dean & Son Ltd v G L Howarth & Coy Ltd (1948) 66 RPC 1.

113 Further, in Dart Industries, Lockhart J (Jenkinson and Gummow JJ concurring) said at 411-412:

The essence of fraudulent imitation is that the respondent’s design has knowingly, consciously or deliberately been based on or derived from the registered design and neither dishonest intent nor deliberate or conscious intention to copy is a necessary element. (emphasis added)

114 It seems clear the Full Court contemplated that the design must be knowingly, consciously or deliberately used or copied.

115 In our opinion, it must be shown that there was deliberate, in the sense of conscious, copying for there to be fraudulent imitation. If imitation imports the notion of making use of the registered design, there must be at least a conscious use of the registered design before it could be concluded there was fraudulent imitation.

116 Therefore, the primary judge proceeded on the correct basis assessing the evidence to see if there was a person or persons on behalf of BlueScope who fraudulently imitated the Design.

Findings of fact

117 Gram also submitted that the evidence before the primary judge was sufficient to find that BlueScope deliberately copied the Design, and the primary judge should have so found.

118 As a preliminary matter, Gram submitted that the primary judge relied too heavily on the so-called gravity of the matters alleged when he considered the question of fraudulent imitation. Gram submitted that it was not required to prove actual dishonesty to establish fraudulent imitation and that in the circumstances the primary judge overemphasised the gravity of the matters alleged. They were not as grave as he considered them to be. We reject this criticism. As we have said, the primary judge formulated the test as to fraudulent imitation correctly and he applied it correctly. The allegation of a fraudulent imitation was a more serious one than an allegation of an obvious imitation and the primary judge was entitled to take that matter into account.

119 We turn then to the evidence before the primary judge.

120 The evidence of Ms Marlin, Mr Seccombe, Mr Gallaty and Ms Fathinia was summarised by the primary judge: at [351]-[390].

121 The two central findings were that Mr Seccombe’s ‘shiplap’ drawing was not a deliberate copy of the GramLine product, and that Mr Gallaty’s 17 November 2000 sawtooth drawing was not a deliberate copy of the GramLine product. It is these findings that require further investigation.

Mr Seccombe

122 Mr Seccombe was the head of the Research and Development department of BlueScope and worked on the Millennium Project.

123 On 13 October 2000, Mr Seccombe prepared some concept drawings for a symmetrical fence profile – one described as a ‘shiplap style’ and another as ‘paling style’: see [130]-[132]. The primary judge found that he would have been aware of the GramLine product when he prepared his drawing: [352]. Mr Seccombe conceded there was similarity between his shiplap drawing and the GramLine product but denied that it was intended to look like the GramLine product. Mr Seccombe’s evidence was that the similarity was a coincidence as a result of the fact that there were only so many ways the shiplap profile can be drawn with manufacturing constraints in mind: at [133]-[135] and [359]-[360].

124 The primary judge was reluctant to accept mere coincidence as the reason between the similarity, but instead decided that the similarity was more likely because the shiplap drawing was based upon profiles drawn by Mr Field in 1996 rather than with an eye to GramLine: [362]-[364]. In the absence of Mr Field, the primary judge could not dismiss a connection between the drawings.

Mr Gallaty

125 Mr Gallaty worked in the Research and Development department of BlueScope and worked on the Millennium Project, and was responsible for most of the drawings which formed part of the Millennium Project. The purpose of the Millennium Project was to design a symmetrical fencing profile and it commenced some time on 1999: [103] ff – Section D The Millennium Project.

126 Mr Gallaty prepared a sawtooth drawing on 17 November 2000, the ‘Cascade 2000’: at [145]. The primary judge held that this was guided by Mr Seccombe’s shiplap drawing (at [365]) and also that he was aware of the GramLine product at this stage: [367]-[368].

127 The primary judge found that the similarities between the sawtooth drawing of 17 November 2000 and GramLine were because of the decision to prepare the design drawings with six pans and given manufacturing constraints on the size of the product, it would necessarily result in a similar configuration to the GramLine product: see [375].

128 Having regard to the same matters the primary judge took into account when addressing Mr Seccombe’s drawing, he was not persuaded that Mr Gallaty’s sawtooth drawing of 17 November 2000 was deliberately copied from, or derived from or based upon Gram’s Design: [381].

129 The primary judge reached that conclusion with reservations because of the striking similarities, and the fact it was designed to look like the GramLine product. However, the absence of Mr Field who was involved in the process, precluded a finding of deliberate copying: [382].

Ms Marlin, Ms Fathinia and Mr Field

130 The evidence of Mr Seccombe and Mr Gallaty must be viewed in the context of Ms Marlin and Ms Fathinia’s evidence. Furthermore, it must be viewed in the context of a memorandum prepared by Mr Field.

131 Ms Marlin was the Business Development manager in the Marketing Division of BlueScope, involved in the instructions that were given to Research and Development from late 2000 to late April 2001.

132 Ms Marlin wrote notes where she stated the need to ‘match or better competitor’s product’ in terms of visual appearance to meet the serious competition from Gram: see [121] and [123], [355], [356]. When these notes were produced was a matter of contention, but the commercial imperative was clear (see [357]), and she was aware of the GramLine product by at least August 2000.

133 The primary judge noted that while Ms Marlin did not accept that she instructed the Research and Development department to design a sawtooth profile, or one that looked like the GramLine, that was the effect of her instructions: see [359].

134 Ms Marlin prepared a Discussion Paper on 26 April 2001 where the ‘Cascade 2000’ was one of two preferred options, was said to have a similar appearance to GramLine, and would therefore be accepted by the market. Furthermore, it was the cheaper alternative and would be a quick-fix to BlueScope’s commercial predicament: see [183] ff and [387].

135 Ms Fathinia worked on the ‘Millennium Project’ while working in the Research and Development department of BlueScope.

136 Ms Fathinia was involved in competitor testing and wrote a report on 14 September 2000 outlining tests carried out on the GramLine fencing, among other competitors’ fences: at [126]. The primary judge accepted that these tests were to test the strength of the fences, however, it showed that BlueScope was aware of the Design – the details of which appeared in the report: at [127]-[128].

137 Ms Fathinia also prepared documents which stated that the objectives of developing a new fence sheet for BlueScope were to improve BlueScope’s fencing market share, match or better competitor’s product (the product must look the same from both sides), and she suggested that BlueScope conduct market and technical assessments: [156]-[160].

138 Mr Field prepared a memo dated 15 November 2000 where he said that ‘we’ were in the process of designing a ‘Gram look alike’ and paling type profile: at [369]. The primary judge decided that ‘we’ must include Mr Gallaty as they sat in adjacent desks, were both involved in the design process and Mr Field was Mr Gallaty’s senior draftsman. The primary judge decided that reference to a ‘Gram look alike’ alone was not sufficient to establish fraudulent imitation, there had to be evidence of actual copying of GramLine.

139 Had Mr Field been able to give evidence, the primary judge would have been able to determine whether or not there was fraudulent imitation with greater certainty. His evidence would have been helpful in determining what Mr Seccombe and Mr Gallaty’s drawings were derived from or based on.

140 There can be no doubt that BlueScope’s Research and Development were under instructions at least to design a product to compete with the GramLine product and that it was to look similar to it, in that it was to have the rotational symmetry we described above.

141 However, consistent with the law on fraudulent imitation there must be something further, namely at least a consciousness on the part of Mr Seccombe or Mr Gallaty to base or derive, or copy GramLine when they prepared their drawings. Furthermore, while Mr Seccombe and Mr Gallaty were responsible for the drawings that are alleged to apply a fraudulent imitation to the Design, neither of them were responsible for the memo or discussion paper that referred to GramLine.

142 The primary judge expressed his view that the drawings were similar to the GramLine sheet but explained the similarities by reference to other drawings, precluding a finding of fraudulent imitation.

143 It must be recalled that the primary judge was at a distinct advantage in that he could assess the credit of Ms Marlin, Mr Seccombe, Mr Gallaty and Ms Fathinia.

144 The findings of fact the primary judge made in relation to Mr Seccombe and Mr Gallaty were not only available to be made, but we can see no error in the approach taken in the assessing of the evidence by the primary judge.

145 The finding that Mr Seccombe’s drawings are derived from Mr Field’s earlier drawings in 1996 and not the GramLine product, is a conclusion reasonably open to the primary judge in the absence of evidence from Mr Field, and in light of the similarity between the drawings themselves.

146 Similarly, it is plausible and a conclusion reasonably open to the primary judge that Mr Gallaty’s drawing was derived from Mr Seccombe’s drawings, and the similarity was coincidental and caused by manufacturing constraints.

147 We see no reason to interfere with the findings of fact made by the primary judge.

148 Finally, we should mention that BlueScope handed to the Court a document titled ‘Appellant’s Contentions on Fraudulent Imitation’. In the document, BlueScope made contentions to the effect that the primary judge erred in making certain findings and submissions about the proper construction of other findings made by the primary judge. The Court indicated that it would receive the document as a Notice of Contention insofar as that was its proper character. As it happens, we have not needed to set out the contentions in any detail because we uphold the findings and conclusions of the primary judge in relation to fraudulent imitation for the reasons we have given.

CONCLUSION

149 In light of our findings in relation to the scope of the monopoly, obvious imitation and fraudulent imitation, the appeal and cross-appeal will be dismissed.

150 The parties are to file within 14 days short minutes of orders disposing of the appeal and cross-appeal, and dealing with the costs of the appeal, or in the absence of agreement, short submissions.

| I certify that the preceding one hundred and fifty (150) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Besanko and Middleton. |

Associate:

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1141 |

ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

| BETWEEN: | BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) Appellant GRAM ENGINEERING PTY LTD (ACN 002 193 311) Cross-Appellant |

| AND: | GRAM ENGINEERING PTY LTD (ACN 002 193 311) Respondent BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) Cross-Respondent |

| JUDGES: | BESANKO, MIDDLETON, YATES JJ |

| DATE: | 26 August 2014 |

| PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

YATES J:

151 I have had the considerable advantage of reading the reasons prepared by Besanko and Middleton JJ in this matter. I agree with their Honours that the appeal and cross-appeal should be dismissed.

152 I wish to make some observations of my own in relation to the primary judge’s findings and conclusions concerning the question of whether the design of the accused article – the Smartascreen fencing panel sheet (the Smartascreen product) – is an obvious imitation of the Design. In order to do so, it is necessary to discuss the primary judge’s findings and reasoning in relation to the construction of the Design in the context of his Honour’s consideration of the novelty or originality of the Design.

Novelty or originality

Introduction

153 Although the validity of the Design was a live issue at trial, Bluescope did not appeal from the primary judge’s finding that the Design was new or original over the prior art, which consists of 10 designs (designated as Designs 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, 18, 19 and 23 respectively), and the designs of other products such as Bluescope’s Trimdeck and Custom Orb products. However, on appeal, Bluescope challenged the basis on which the primary judge arrived at that finding. In essence, Bluescope submitted that the primary judge erred in his construction of the Design.

154 Bluescope’s challenge focused on two important findings made by the primary judge. The first was that the Design is to be construed as “one in which the sawtooth pans extend vertically down the face of the sheet”: see at [245]. The second was that the visual appearance of any given sawtooth design (that is, as applied to a fencing panel sheet) will be substantially affected by the amplitude, wavelength and angles of the sawtooth in combination with the number of modules (or pans) created thereby: see at [250].

155 When considering the overall appearance of a fencing panel sheet to which the Design has been applied, the second finding should not be considered in isolation from the first finding concerning the orientation of the Design, specifically the vertical orientation of the six pans. The primary judge reasoned that the vertical orientation of the pans has a substantial effect on the three-dimensional appearance of a fencing panel sheet made in accordance with the Design, particularly in that, in that orientation, the sheet has a symmetrical appearance, “causing it to look the same from both sides”: see at [245]. This last mentioned finding is a reference to the fact that, in that orientation, a fencing panel sheet to which the Design has been applied will have the same appearance, front and back, when the sheet is rotated 180° about its vertical axis.

156 The significance of these challenges by Bluescope is that, if successful, the novelty or originality of the Design over the prior art would lie substantially with two features of the Design which the primary judge considered to be of secondary importance.

157 The first is the feature of a “sawtooth within a sawtooth”. The primary judge described this as a “subtle” feature that is, nevertheless, one that should be recognised as a new visual feature: see at [259]. Functionally, this feature acts as a “stiffener” which prevents “oil canning” – the process of deformation of a sheet due to buckling in the course of manufacture or installation.

158 The second feature is the appearance of the flanges on each side of the fencing panel sheet. Each flange functions to enable a “lap joint” to be formed, so that the fencing panel sheet can be conveniently joined with other fencing panel sheets to which the Design has been applied.

159 If, as Bluescope contended, the novelty or originality of the Design is to be found substantially in these two features, it would follow that the comparison between the Design and the design of the Smartascreen product, when considering whether the latter is an obvious imitation of the former, should have proceeded on a fundamentally different basis to the comparison which the primary judge, in fact, undertook. This is because, as the primary judge also recognised (see at [29]), questions of infringement, and novelty or originality, are connected.

160 In Dart Industries Inc v DÉcor Corporation Pty Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 403 Lockhart J (at 409-410) observed:

The scope of a registered design must be determined with reference to the background of the prior art at the priority date and questions of infringement and novelty or originality are connected. In Hecla Foundry Co v Walker, Hunter & Co (1889) 14 App Cas 550 at 55 Lord Herschell said : “… one may be able to take into account the state of knowledge at the time of registration, and in what respects the design was new or original, when considering whether any variations from the registered design which appear in the alleged infringement are substantial or immaterial.”

Where novelty or originality is discovered in slight variations, there cannot be infringement without a very close resemblance between the registered design and the article alleged to be an infringement of the design. Lloyd-Jacob J in Rosedale Associated Manufacturers Ltd v Airfix Products Ltd [1956] RPC 360 at 364 said that the court would have regard to what was “known and old”, and: “… if the particular features which provide a novel conception have not been reproduced in the alleged infringement, the similarity of appearance between the article complained of and the registered design if present must necessarily reside in the common possession of characteristics which are free to everybody to employ.” See also Macrae Knitting Mills Ltd v Lowes Ltd (1936) 55 CLR 725 at 731 per Dixon J and L J Fisher & Co Ltd v Fabtite Industries Pty Ltd (1978) 49 AOJP 3611 at 3620 per Fullagar J.

Small differences between the registered design and the prior art will generally lead to a finding of no infringement if there are equally small differences between the registered design and the alleged infringing article. On the other hand, the greater the advance in the registered design over the prior art, generally the more likely that a court will find common features between the design and the alleged infringing article to support a finding of infringement: Kevi A/S v Suspa-Verein UK Ltd [1982] RPC 173 at 179 per Falconer J; Firmagroup v Byrne & Davidson, supra, at 38; D Sebel & Co Ltd v National Art Metal Co Pty Ltd (1965) 10 FLR 224 at 229 per Jacobs J; Russell-Clarke, Designs, 5th ed, pp. 85–7; Blanco White on Patents and Designs, 4th ed, pp 326–7; and Ricketson, The Law of Intellectual Property, p 493.

The trial judge paid regard to the importance of prior art and did so, in my opinion, correctly when he said [Dart Industries Inc v Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1988) 11 IPR 134 at 139]: “The significance of relevant prior art is that the scope of protection of a registered design will depend upon the extent to which its features are seen to be novel or original against the background of prior knowledge.”

161 Further, Bluescope submitted that the “sawtooth within a sawtooth” feature is a “visually striking” and “important” feature (as opposed to the “secondary” and “subtle” feature found by the primary judge) which was not present in the prior art or, indeed, the design of the Smartascreen product.

162 Given this setting, it is convenient to return to consider the correctness of the two findings concerning the primary judge’s construction of the Design which Bluescope has challenged.

Vertical orientation

163 Bluescope advanced a number of submissions when challenging the primary judge’s finding that the Design is to be considered as one in which the sawtooth pans extend vertically down the face of the fencing panel sheet. These submissions can be summarised as follows:

Orientation is not a feature of shape or configuration.

The Design should not be construed by reference to one particular use of the article to which the Design will be applied. Bluescope submitted that the primary judge went further than construing the Design with an “instructed eye”.

The primary judge “read into the Design” other features, such as posts and rails.

The primary judge was wrong to rely on Mr Wightley’s evidence because, amongst other things, Mr Wightley took into account considerations of utility.

The primary judge erred in finding that the vertical orientation of the Design gave it novelty or originality over the prior art. Bluescope submitted that the prior art articles are only relevant in respect of their shape, not the orientation of the articles to which those shapes have been applied.

Vertical orientation is not a feature of the Design. Bluescope submitted that if vertical orientation is a feature of the Design, it does not confer novelty or originality over the prior art because symmetrical Z-shaped designs were not novel or original.

164 In order to appreciate the thrust of Bluescope’s submissions, it is important to distinguish between how an article to which a design has been applied may be orientated irrespective of its design, and how a design, properly construed, is intended to be applied to the article in respect of which it is registered. In other words, the design itself may have a specific orientation which, when properly applied to the relevant article, imparts the orientation in which the article should be viewed. In this way, the orientation of a design may be a substantial contributing factor to the appearance of the article to which it has been applied.

165 In the present case, the primary judge found that the Design has a specific orientation. In arriving at that conclusion, the primary judge correctly noted that there is no express mention in the registration that the pans have a vertical orientation. Nevertheless, his Honour found that a proper reading of the Design indicates that orientation.

166 In my respectful view, the primary judge was plainly correct in coming to that conclusion. Here, the accompanying representations illustrating the Design unequivocally show that the flanges are located at the sides of the sheet, not at the top and bottom ends of the sheet. This means that the pans must have a vertical orientation. This is not a reading of the Design which necessarily requires the assistance of expert evidence. In my view, it is the obvious conclusion to be drawn from looking at the accompanying illustrations, particularly the second illustration representing a side view of the sheet, which clearly shows a flange as a side element.

167 Mr Halpern (one of Bluescope’s witnesses) gave evidence that he read the representations as depicting the pans running vertically because the end forms (that is, the flanges) are designed to overlap adjoining sheets within (I infer, vertically within) posts and rails. Mr Wightley (Gram’s expert witness) gave evidence to the same effect. He pictured the pans in a vertical orientation meeting or overlapping in a neat way to form a continuous fence fitting together at the edges between posts and rails.

168 The primary judge’s reference to Mr Halpern’s and Mr Wightley’s conception of the vertically orientated sheets fitting within posts and rails appears to be the reason for Bluescope submitting that the primary judge read into the Design “features and requirements … which do not and cannot form part of the monopoly of the Design”.

169 Mr Wightley also gave evidence that, if installed horizontally, a fencing panel sheet made according to the Design would be likely to buckle or deform. In other words, the “stiffeners” (that is, the “sawtooth within a sawtooth” feature) would not perform their apparently intended function. The primary judge’s reference to this evidence is the reason for Bluescope submitting that the primary judge impermissibly took into account questions of utility when construing the Design.

170 In my view, the primary judge did not err in taking Mr Halpern’s and Mr Wightley’s evidence into account, in the particular way in which his Honour did, when construing the Design.

171 First, I do not accept that the primary judge read into the Design features and requirements that were not part of the Design. Rather, the primary judge treated the Design for what it truly is – a design for a fencing panel sheet. The description of the article as a panel sheet conveys, as a matter of ordinary language, the notion that the article to which the Design is intended to be applied, is one to be supported by or enclosed within some structure, frame or border. In the context of fencing (a fencing panel sheet), this would clearly include, but would not necessarily be confined to, a structure, frame or border provided by posts and rails. But, by referring to Mr Halpern’s and Mr Wightley’s evidence in this regard, the primary judge did not thereby incorporate additional features, such as posts and rails, into his construction of the Design itself.

172 Secondly, Mr Wightley’s evidence that the “sawtooth within a sawtooth” feature has an apparent functional significance, as well as a visual significance, plainly assists in understanding whether the Design has a specific orientation. This appreciation is not tantamount to judging the validity of the Design, in terms of its novelty or originality, by its utility as opposed to its appearance. Whether or not the “sawtooth within a sawtooth” feature would usefully act as a stiffener and would, by reason of such utility, distinguish the fencing panel sheet of the Design from prior fencing panel sheets or other analogous items, is not a question that is relevant to the novelty or originality of the shape or configuration claimed as the Design: Moody v Tree (1892) 9 RPC 333. Clearly, the primary judge did not treat utility in that way. However, his Honour correctly reasoned (at [209]) that it would be artificial to exclude from the construction of the Design an appreciation, through the instructed eye, that one of its visual features also has an apparently intended functional significance. When one has that appreciation, the presence of the “sawtooth within a sawtooth” feature assists in understanding whether the Design has a specific orientation. If so, the question is whether the Design, as so construed (that is, with its specific orientation), is new or original as a matter of, relevantly, shape or configuration applied to a fencing panel sheet. This is the correct question, which the primary judge addressed.

173 In my view, it is beside the point that, as Bluescope suggested in argument, someone might seek to install a fencing panel sheet to which the Design has been applied, in a fashion in which the pans run horizontally and not vertically. This is not the intended use of an article made according to the Design. In the case of the commercial embodiment of the Design (the GramLine product), the use of the sheet with the pans running horizontally is not a use that was promoted or, indeed, suggested by Gram. Moreover, in relation to the Smartascreen product, such use is not a use of that product that was promoted or suggested by Bluescope. The aberrant use of an article to which the Design or an alleged imitation of it has been applied, can be put to one side.

174 The vertical orientation of the pans distinguishes the Design from the prior art designs having sawtooth or sawtooth-like profiles. The prior art designs do not reveal, at the relevant time, the existence of a fencing panel sheet of a sawtooth design where the pans extend vertically down the face of the sheet, let alone such a fencing panel sheet which is symmetrical in appearance, front and back, when viewed in that orientation. The prior art cladding, represented by Designs 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, 18, 19 and 23 – which the primary judge described, collectively, as simulated or faux weatherboard (but which also include roofing elements) with pans running across the width of the articles – has a horizontal orientation. In that orientation, these designs do not present a symmetrical appearance, front and back. Further, these designs possess other features, not found in the Design, which materially contribute to the appearance of the articles to which each is intended to be applied, and which further distinguish them from the Design. The prior art designs represented by products such as the Trimdeck and Custom Orb products do not present a sawtooth appearance.

The sawtooth design

175 Bluescope’s submissions dealt separately with the primary judge’s findings concerning, first, the significance of the number of vertical pans in the Design and, secondly, the significance of the particular appearance of the sawtooth shape of the Design.

176 Bluescope submitted that the primary judge erroneously regarded the number of pans as being relevant to the novelty or originality of the Design. Bluescope submitted that it is the repeating pattern of the pans that provides a visually striking feature, not the number of pans in the Design. Bluescope also submitted that the primary judge did not have regard to “the potential for the prior art to be repeated to achieve six panels across the same (hypothetical) panel width”, or consider a comparison with “designs of the same relative scale”.

177 In my view, the primary judge did not err by taking into account, when assessing novelty or originality, the number of pans per fencing panel sheet shown in the Design. The number of pans is plainly part of the combination that is claimed as the Design. The Design is not merely one for a fencing panel sheet having an indefinite number of repeating pan-like elements. Rather, it is for a fencing panel sheet having six vertically orientated pans, bounded on each side of the sheet by flanges having a particular appearance. As the statement of monopoly makes clear, only the longitudinal extent of the fencing panel sheet “is to be disregarded”. The longitudinal extent of the fencing panel sheet, in the context of the accompanying representations of the Design, is plainly a reference to the length of the sheet, top to bottom, in its vertical orientation.

178 With respect to the amplitude, wavelength and angles of the sawtooth shape, Bluescope submitted that, when a side-by-side comparison of the prior art designs with the Design is undertaken, the range of amplitude, wavelength and angles that give the Design its novelty is “narrow”. Bluescope relied, in particular, on Designs 2, 4 and 6 of the prior art which, it submitted, are examples of sawtooth shapes having similar amplitude, wavelength and angles to the amplitude, wavelength and angles of the sawtooth shape of the Design. However, to argue that particular prior art designs exhibit sawtooth shapes having similar amplitudes, wavelengths and angles to the Design does not advance matters significantly when other features of the Design distinguish it from the prior art designs. Whilst as a matter of systematic exposition, one can describe and compare, in turn, separate features of shape or configuration in given designs, it is, of course, the combination of features – the overall appearance – of a design which is important.

179 As Young J put the matter in Ullrich Aluminium Pty Ltd v Dias Aluminium Products Pty Ltd (2006) 153 FCR 437 at [64]:

… Even if one or other piece of prior art contains a particular feature that is similar to that found in the registered design, does the blending together of a number of features of that kind, alongside other features of style, configuration or pattern, result in a combination that has a special and distinctive appearance which is new or original? ...

180 The primary judge was mindful of this fact, noting at [255] that none of the items of prior art relied upon by Bluescope had the same combination of six pans with the proportions and angles shown in the representations of the Design. His Honour’s reasons also make clear that this particular finding was not divorced from, and should not be seen in isolation from, his Honour’s finding concerning the orientation of the six pans: none of the prior art designs had “sawtooth pans that extend vertically down the face of the sheet”: see at [245] and [246].

Overall conclusion on novelty or originality

181 The features of the Design identified by the primary judge are features of substance, all of which contribute materially (although in different ways) to the overall shape or configuration of the fencing panel sheet to which the Design is to be applied. In my respectful view, the primary judge’s analysis does not reveal any error in his Honour’s identification of those features or with respect to the significance which his Honour gave them, as a matter of design construction.

182 Similarly, the differences noted by the primary judge, when comparing the Design with the prior art designs, are differences of substance, all of which contribute materially (although in different ways) to distinguishing the Design from the prior art designs, in terms of novelty or originality. In my respectful view, the primary judge’s analysis does not reveal any error in his Honour’s identification of those differences or with respect to the significance which his Honour gave them, as a matter of design comparison.

183 The primary judge’s assessment of these features and differences plainly informed his Honour’s understanding of the scope of the monopoly in the Design, when considering the question of obvious imitation.

Obvious imitation

184 The foundation for Bluescope’s challenge to the primary judge’s finding that the design of the Smartascreen product is an obvious imitation of the Design, is its contention that the scope of the monopoly in the Design is narrow and:

… is found in the distinguishing sawtooth-within-a-sawtooth feature in the middle of each pan together with a particular combination of amplitude, wavelength and angles.

185 Bluescope submitted that it is these features of the Design that must be considered when assessing infringement. In other words, it submitted that when comparing the Design and the design of the Smartascreen product, it is the presence or absence of these features in the design of the Smartascreen product that is critical to the analysis of whether that design is an obvious imitation of the Design.

186 The following matters should be noted.

187 First, in confining the comparison in this way, Bluescope seeks to put to one side the fact that the Design is one in which the sawtooth shape defines six vertically orientated pans bounded at the sides of the sheet by flanges of a particular shape, such that the sheet is symmetrical in appearance when viewed from front and back. However none of the prior art designs exhibits this combination. Each prior art design is of a markedly different appearance. Yet, this combination is, undoubtedly, a fundamental part of the design of the Smartascreen product.

188 Secondly, Bluescope’s contention that the sawtooth shape of the Design is formed by a particular combination of amplitude, wavelength and angles is undoubtedly correct. But this does not mean that the amplitude, wavelength and angles of the sawtooth shape of the Design should be confined to the very narrow limits that Bluescope’s contention seems to imply. One sawtooth shape may closely resemble another in appearance, even though the former does not possess the same amplitude, wavelength and angles of the latter. The issue is one of eye appeal, not geometric identity or exactitude. Further, the sawtooth shape of the Design, and the sawtooth shape of the design of the Smartascreen product, should not be considered in isolation from the particular combination referred to in the preceding paragraph.

189 There are, however, two features of the design of the Smartascreen product to which reference should be made.

190 The first is that the rendering of the sawtooth shape in the design of the Smartascreen product includes a “ridge/valley” feature. This feature is visible in the image of the Smartascreen product reproduced at [53] of the primary judge’s reasons. It is also identified in Figure 6 in an affidavit made by Bluescope’s expert, Mr Richardson. Figure 6 is reproduced at [61] of the primary judge’s reasons. The ridge/valley feature is identified by the letters A and B. This feature affects the appearance of the sawtooth shape in the design of the Smartascreen product. It also affects the amplitude, wavelength and angles of that shape. Bluescope submitted that the Smartascreen sawtooth profile is “more complex and subtle with more bends and angle changes than the Design”.

191 The second feature is that the design of the Smartascreen product has “micro-fluting” on the face of each pan. This feature can also been seen in the photograph reproduced at [53], and in Figure 6 (see letter C) reproduced at [61], of the primary judge’s reasons.