FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nojin v Commonwealth of Australia [2012] FCAFC 192

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| ELIZABETH NOJIN ON BEHALF OF MICHAEL NOJIN Appellant | |

| AND: | First Respondent COFFS HARBOUR CHALLENGE INC (IN LIQUIDATION) Second Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: | sydney (via video link to melbourne) |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The orders made by Gray J on 16 September 2011 and 25 November 2011 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be ordered that:

“THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Second Respondent unlawfully discriminated against the Applicant in contravention of s 15 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 by imposing on the Applicant a requirement or condition that in order to secure a higher wage the Applicant undergo a wage assessment by the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The first respondent pay the applicant’s costs, as taxed if not agreed.

3. The amended application filed on 27 February 2009 be otherwise dismissed.”

3. The first respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal, such costs to be taxed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1111 of 2011 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | GORDON PRIOR Appellant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent STAWELL INTERTWINE SERVICES INC Second Respondent |

| JUDGES: | BUCHANAN, FLICK AND KATZMANN JJ |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 21 DECEMBER 2012 |

| WHERE MADE: | sydney (via video link to melbourne) |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is upheld.

2. The orders made by Gray J on 16 September 2011 and 25 November 2011 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be ordered that:

“THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Second Respondent unlawfully discriminated against the Applicant in contravention of s 15 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 by imposing on the Applicant a requirement or condition that in order to secure a higher wage the Applicant undergo a wage assessment by the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The first respondent pay the applicant’s costs, as taxed if not agreed.

3. The amended application filed on 27 February 2009 be otherwise dismissed.”

3. The first respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal, such costs to be taxed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1110 of 2011 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | ELIZABETH NOJIN ON BEHALF OF MICHAEL NOJIN Appellant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent COFFS HARBOUR CHALLENGE INC (IN LIQUIDATION) Second Respondent |

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 1111 of 2011 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | GORDON PRIOR Appellant |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent STAWELL INTERTWINE SERVICES INC Second Respondent |

| JUDGES: | BUCHANAN, FLICK AND KATZMANN JJ |

| DATE: | 21 December 2012 |

| PLACE: | sydney (via video link to melbourne) |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BUCHANAN J:

Introduction

1 These cases were brought by or on behalf of two intellectually disabled men, Mr Michael Nojin and Mr Gordon Prior. Mr Nojin and Mr Prior each worked in an Australian Disability Enterprise (“ADE”). The proceedings concern complaints that, by using a particular tool to measure their work contribution, and ultimately to assess their wages, the ADEs in which Mr Nojin and Mr Prior worked discriminated against them in their employment, compared to other disabled persons who were not, as they are, intellectually disabled.

2 Mr Nojin suffers from cerebral palsy and has a moderate intellectual disability. He also has epilepsy. Mr Nojin worked in an ADE known as Coffs Harbour Challenge Inc (“Challenge”). Prior to the proceedings at first instance Mr Nojin had worked at Challenge for close to 25 years. Challenge is now in liquidation, but that does not affect the conduct of the proceedings as the Commonwealth of Australia, which is also a party to the proceedings, has agreed that if Challenge is liable for discrimination as alleged, the Commonwealth will bear the liability.

3 Mr Prior is classified as legally blind, although he has some vision. He also has a mild to moderate intellectual disability. Mr Prior worked in an ADE known as Stawell Intertwine Services Inc (“SIS”). Prior to the proceedings at first instance, Mr Prior had worked at SIS for about two years.

4 Whether the allegations of discrimination against Mr Nojin and Mr Prior should be accepted depends upon the operation of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (“the Act”), in the form it took between 2005 and 2008.

5 At that time s 15(2) of the Act provided:

(2) It is unlawful for an employer or a person acting or purporting to act on behalf of an employer to discriminate against an employee on the ground of the employee’s disability or a disability of any of that employee’s associates:

(a) in the terms or conditions of employment that the employer affords the employee; or

(b) by denying the employee access, or limiting the employee’s access, to opportunities for promotion, transfer or training, or to any other benefits associated with employment; or

…

(d) by subjecting the employee to any other detriment.

6 Section 4 of the Act defined “disability” to mean:

(a) total or partial loss of the person’s bodily or mental functions; or

(b) total or partial loss of a part of the body; or

(c) the presence in the body of organisms causing disease or illness; or

(d) the presence in the body of organisms capable of causing disease or illness; or

(e) the malfunction, malformation or disfigurement of a part of the person’s body; or

(f) a disorder or malfunction that results in the person learning differently from a person without the disorder or malfunction; or

(g) a disorder, illness or disease that affects a person’s thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgment or that results in disturbed behaviour;

and includes a disability that:

(h) presently exists; or

(i) previously existed, but no longer exists; or

(j) may exist in the future; or

(k) is imputed to a person.

7 Sections 5 and 6 of the Act supplied further legislative content to the phrase “on the ground of…disability” as used in s 15 of the Act. Section 5 provided that discrimination on the ground of a disability occurred where, because of his or her disability, a person was treated less favourably than someone without the disability. This is generally known as direct discrimination. The present case does not concern direct discrimination. It concerns indirect discrimination.

8 Section 6 of the Act dealt with indirect discrimination. At the relevant time it provided:

6 For the purposes of this Act, a person (discriminator) discriminates against another person (aggrieved person) on the ground of a disability of the aggrieved person if the discriminator requires the aggrieved person to comply with a requirement or condition:

(a) with which a substantially higher proportion of persons without the disability comply or are able to comply; and

(b) which is not reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the case; and

(c) with which the aggrieved person does not or is not able to comply.

9 This statutory test in s 6 had four components which require attention in the present case. First, it is necessary to identify the relevant “requirement or condition” with which the aggrieved person must comply. The authorities indicate that the requirement or condition must be identified with some precision (Australian Iron and Steel Pty Limited v Banovic (1989) 168 CLR 165 at 185; Waters v Public Transport Corporation (1991) 173 CLR 349 at 393, 406-7; Catholic Education Office v Clarke (2004) 138 FCR 121 (“Clarke”) at 143). Secondly, in order to succeed, an aggrieved person must establish that “a substantially higher proportion of persons without the disability” were able to comply with the requirement or condition. Thirdly, an aggrieved person bears the onus of establishing that the requirement or condition was not reasonable in the circumstances. Finally, the aggrieved person must have in fact been unable to comply with the requirement or condition.

10 Rates of pay for disabled workers (including those with intellectual disabilities) employed at ADEs are fixed in accordance with an award made by the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (now Fair Work Australia). The award, at the relevant time, enabled employers to pay disabled workers rates of pay assessed as a percentage of the rate of pay fixed for a Grade 1 worker. The Grade 1 rate was the lowest rate of pay under the award. Other features of the award will be mentioned in due course.

11 The present case concerns the use of the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool (“BSWAT”) to determine the wage rates of both Mr Nojin and Mr Prior. BSWAT examined both a disabled worker’s “productivity” (by reference to work actually performed) and also the extent to which a disabled worker possessed identified “competencies”. An assessment of competencies (as the term is here used) does not relate necessarily, and often will not relate, to work actually carried out, or the way it is performed. Rather, an assessment of competencies tests more general knowledge, and perhaps aptitude. I shall, in the discuss which follows, refer to competencies as incorporated in BSWAT, but it will become clear from the later discussion that, in my view, the use of the term in this context refers to something that is more theoretical than practical.

12 Broadly speaking the challenge made in the present proceedings was that examination of competencies proceeded by reference to questions involving abstract concepts, which intellectually disabled persons would find more difficult to answer correctly or successfully than disabled persons who are not intellectually disabled. One difficulty for the appellants’ case was that the wage rates of all disabled persons at the two establishments in question were assessed using BSWAT. In that sense Mr Nojin and Mr Prior were able to “comply” with any requirement or condition that their work contribution be assessed in accordance with BSWAT. Hence the focus of attention was placed on the idea that they (and other intellectually disabled persons) were less able than non-intellectually disabled persons to obtain “higher” results leading to higher pay. Formulated in this way the case faced some conceptual difficulties. However, this was the characterisation of “requirement or condition” which was necessary for the case to satisfy s 6(a) and (c) of the Act. I will return to examine this part of the case in more detail in due course.

13 In addition, it was necessary for the appellants to establish that use of BSWAT was “not reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the case” (s 6(b)). Examination of this issue will require some consideration of the circumstances in which BSWAT was introduced, the extent to which it is now applied in ADEs and elsewhere, and the significance of the fact that it assessed competencies as well as productivity.

14 The trial judge concluded that use of BSWAT was not indirectly discriminatory of Mr Nojin or Mr Prior. That conclusion proceeded from findings made by the trial judge that Mr Nojin and Mr Prior were not less able than other disabled people (not intellectually disabled) to comply with the relevant requirement or condition, and that, in any event, it was reasonable for their wages to be assessed using BSWAT.

The key issues

15 The written submissions of the respondents identified the issues for resolution on the appeal, in a way accepted by the appellants, as follows:

1. In both proceedings, the Appellants’ Notices of Appeal set out 21 grounds of appeal. Within these grounds, there are effectively two issues:

(a) Whether the trial judge erred in identifying the requirement or condition alleged to have been imposed by each of the Second Respondents (respectively, Challenge and SIS) and the extent to which each of the Appellants could comply with this requirement or condition, for the purposes of s.6 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (the Act) (Grounds 1-7); and

(b) Whether, to the extent that any condition or requirement was imposed on the Appellants by each of the Respondents (with which they could not comply), the trial judge erred in failing to determine that such a condition or requirement was not reasonable, for the purposes of s.6 of the Act (Grounds 8-21).

16 A third issue was raised by a Notice of Contention filed by the respondents which challenged a finding by the trial judge that s 45 of the Act did not provide a good defence to the respondents if the appellants had been successful in establishing that use of BSWAT was indirectly discriminatory.

17 Section 45, so far as here relevant, provided:

45 This Part does not render it unlawful to do an act that is reasonably intended to:

…

(b) afford persons who have a disability or a particular disability, goods or access to facilities, services or opportunities to meet their special needs in relation to:

(i) employment, … ; and

(ii) the provision of…services … ; or

…

(iv) the administration of Commonwealth laws and programs; …

(c) afford persons who have a disability or a particular disability, grants, benefits or programs, whether direct or indirect, to meet their special needs in relation to:

(i) employment, … ; or

(ii) the provision of…services … ; or

…

(iv) the administration of Commonwealth laws and programs; …

Disabled employment

18 Broadly speaking, there are two environments in which wage-earning employment opportunities are available for disabled people: open employment and employment with an ADE. In open employment settings a majority of the workforce consists of persons without disabilities; at ADEs workers with disabilities comprise a majority of the workforce.

19 The wages available to disabled people are generally well below those available to non-disabled people. ADEs grew out of what were previously known as sheltered workshops. Sheltered workshops were generally located in large segregated settings, and their purpose was to provide a ‘work-like’ environment where people with disabilities could engage in activities outside their living environment. In more recent times, the purpose of ADEs has been to provide meaningful paid employment for people who, due to their disability, may find it difficult to obtain employment in the open labour market. Initially the provision of any form of remuneration for those supported by the sheltered workshop environment was very ad hoc. The task of arriving at a national and reasonably uniform approach to assessing wages, both in open employment and in ADEs, came into focus after the establishment by the Federal government in 1988 of a “Disability Task Force”. The Disability Task Force was established to oversee implementation of income support measures in a “Disability Reform Package” introduced by the Federal government. In that context, a Wages Subcommittee was established to advise the Disability Task Force.

20 The 1990/1991 Federal budget provided for further consideration of the development of a supportive wage system for people with disabilities. To that end, in January 1992 a report authored by Mr Don Dunoon, a consultant with New Futures Pty Limited, with the assistance of Ms Jennifer Green from the Australian Catholic University, Sydney, was provided to the Wages Subcommittee. The report recorded that “supported employment services” usually provided employment opportunities to individuals with an intellectual disability, although they might have other disabilities as well. It recorded that:

Supported employment services have, since their establishment from the mid-1980s, provided real opportunities for people with significant disabilities, particularly of an intellectual nature, to gain access to jobs in open employment.

21 In addition, some employment opportunities were offered by sheltered workshops themselves. These various arrangements, as I said earlier, produced a variety of methods for addressing the question of remuneration for disabled people. The authors of the report stated:

In the view of the consultants, it is preferable to have the one system for all persons with disabilities, for reasons of simplicity and consistency. This is especially so in view of the fact that many people with disabilities have complex disabilities, perhaps including some combination of physical, intellectual, psychiatric and sensory disabilities. Obviously, any requirement for such people to be assessed through different systems should be avoided.

22 The authors of the report stated that a principle that must be recognised by all parties was that “the effects of a disability on job performance can only be determined in the context of a particular individual in a particular job and workplace environment”. However, the authors also considered that “an individual should preferably be assessed on at least three tasks/competencies”. They also said:

In considering the work value of…jobs, the first point to note is that the concern is with the worth of the job performed, not the efficiency or productiveness of the worker with disability in comparison with co-workers.

(Emphasis in original.)

23 This approach appears to be the forerunner of a philosophy now reflected in BSWAT and in other tools which set out to measure both productivity in a particular job and competencies assessed more generally against “industry standards”. However, in terms of practical application, the idea of measuring or assessing competencies rather than, or in addition to, productivity was not immediately embraced, and still does not apply in open employment.

24 In October 1994 a Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission approved a model clause to be inserted in various federal awards requiring the use of a nominated tool to assess the wages of disabled workers in open employment (“the SWS tool”). The SWS tool was, and remains, a productivity-based assessment tool.

25 It is important to note that the ultimate entitlement to wages for persons like Mr Nojin and Mr Prior, and others employed in ADEs, is now also founded upon a federal award. And as will be seen, use of BSWAT is now permitted in ADEs by the award, although not in open employment. One question which arises in the present case (after a number of others have been addressed) is whether use of BSWAT was reasonable in the case of Mr Nojin and Mr Prior, or whether a tool like the SWS tool should have been used, as it still is in open employment.

26 In June 1995 a “Supported Wage System Handbook” was published by the Supported Wage Management Unit of the Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health. It commenced its description of the wage assessment process with the following statement:

A productivity-based wage essentially requires a standard to be set of the productivity needed for award-level pay; and then an assessment of the worker’s achievement against that standard.

27 Again, this basic principle is an important one to bear in mind in the discussion which follows. The comparison contemplated by this approach is between the tasks for which an award rate of pay is actually fixed and the work actually carried out by a (disabled) worker. As mentioned, consistently with this approach the SWS tool remains the only one which is approved for use in open employment.

28 In 2001 a new award was made which related directly to work done by disabled people in the Business Services sector. The Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union Supported Employment (Business Enterprises) Award 2001 (“the award”) provided, by clause 14.1:

14.1 Upon appointment, an employee will be graded by the employer in one of the grades in Schedule A having regard to the employees skills, experience and qualifications.

and by clause 14.3:

14.3 Employees with a disability will be paid such percentage of the rate of the employees grade as equals the skill level of the employee assessed as a percentage of the skill of an employee who is not disabled.

(Emphasis added.)

29 Schedule A of the award identified work at the Grade 1 level in the following way:

SCHEDULE A

1. CLASSIFICATIONS

1.1 Grade 1

…

1.1.2 An employee at this level performs basic routine duties essentially of a manual nature and to their level of training. Persons at this level exercise minimal judgement and work under direct supervision whilst undergoing structure training to Grade 2.

1.1.3 Examples of duties at this Grade include basic cleaning within a kitchen or food preparation area including cleaning of dishes and utensils, labouring, sorting, packing, labeling, clipping, assembly document preparation and routine basic assembly tasks.

30 Having regard to the provisions of clause 14.3, the assessment of a wage for a disabled worker at this point in time involved a comparison of applied skills at a basic level of actual work. It involved the sort of assessment required by the SWS tool, which was used in open employment. It did not involve an assessment of the kind represented by the competency component of BSWAT.

31 However, notwithstanding the regime which was represented by the award, where wage outcomes were to be measured by a productivity comparison with work at a Grade 1 level, further reviews were underway in relation to the Business Services sector.

32 In 2000 a report was prepared by KPMG Consulting on behalf of the Department of Family and Community Services and ACROD (a disability services advocacy group). It addressed the Business Services sector in which the work previously carried out by sheltered workshops was continuing. It commenced:

The Business Services Review has established that Business Services have an important role to play in the provision of real employment options for people with disabilities. To achieve this end, it should be now formally recognised that Business Services are required to provide ongoing employment support while concurrently operating and maintaining commercially viable businesses.

The Business Service Review has identified, for the first time, the competing demands confronted by Business Services in meeting their dual objectives. These demands are more complex than those confronted by any small business or for that instance, any other provider of disability support.

33 A matter of key importance in the report was the question of the commercial viability of enterprises in the Business Services sector. The following passages emphasise the dual role played by such enterprises:

A new paradigm for Business Services

The evolution of Business Services over time has lead to an ambiguity about their role and function within the specialised employment system and within the broader labour market. Shifts in policy directions have exacerbated this ambiguity which has left many Business Services unclear about their core roles and functions.

Business Services must have at their core, a dual focus, the provision of supported employment and the operation of a commercially viable business. Their duality of focus demands that they balance two effectively competing requirements to achieve success.

As part of such a model the target population for Business Services appears best determined by individual choice and ability and willingness to participate in work activities. This ensures that, consistent with the Commonwealth’s stated policy objectives for people with disabilities, opportunities for employment remain available not only to people with low support need but also to those with high support needs who wish to be employed.

Provision of employment

A Business Service’s capacity to provide good employment conditions for its employees (that is people with disabilities) is dependent, in the main, on its ability to develop and maintain a commercially viable enterprise.

For Business Services industry, this pre-condition is difficult to achieve. Currently only 53% of the industry breaks even or is able to return a profit.

Financial performance has a direct impact on the ability of Business Services to meet the costs associated with the provision of comprehensive employment conditions.

So in order for Business Services to fulfil their obligations as an employer, financial viability must be addressed concurrently with the establishment of a consistent approach to industry-based employment conditions.

Linkages with the employment and income security system

As employers, Business Services have strong links with the labour market – they are subject to the similar pressures and demands as many employers and have many characteristics that are common to small businesses. Their fundamental difference however is their duality of focus.

34 On the present appeal, some emphasis was placed by the respondents on the fact that the Business Services sector is substantially underwritten by funding from the Federal government and upon the idea, captured in the extracts above, that the “commercial” environment for many ADEs is challenging. Presumably, these matters are thought to suggest and justify careful management of scarce resources. So much may be accepted. The case for the appellants is not founded upon any suggestion that scarce resources should be squandered.

35 In the 2000 KPMG report, a number of recommendations were made. Recommendation 8 read:

Recommendation 8: That in employing people with disabilities with varying skill levels, that remuneration is linked to an individual’s productivity and to an agreed industry-wide system for assessing general work competencies.

36 There was reference in the report to perceived difficulties with the use of the SWS tool as the sole measure for wage assessment. Reference was made to “concerns about the use of productivity as the sole determinant of wages”. It was said:

In recent times there has been a move towards wage systems that involve a mix of productivity assessment and competency assessment as a means of addressing fluctuating output. Such an approach can also provide the means by which an individual’s suitability for employment can also be assessed. The introduction of competencies can enable the recognition of the skills an employee has attained as well as rewarding productivity.

(Emphasis added.)

37 The consideration I have emphasised in the passage above is not one which has any role to play in the present proceedings. Mr Nojin was a long-term employee of his ADE. There was no suggestion that the contribution of either Mr Nojin or Mr Prior to the commercial effort of their respective ADEs was inappropriate or that they were otherwise unsuitable for employment in that environment. The issues between the parties were contested in a broader context – namely, the suitability of BSWAT as a measure of work value. The last sentence in the extract above makes it clear that introducing competencies as a consideration provides an increased dimension to the achievement which would be recognised, and at the same time required, from a worker. This new requirement need not be related to work actually being done. However, as I have already said, it is important to appreciate also that this particular issue must be resolved in the further context set by the operation of the award. It is the award which states the legal entitlement to a payment. The issue in the present case is not being resolved in a regulatory vacuum filled only by competing theories and wage-fixing philosophies.

38 Around this time, the Department of Family and Community Services commissioned Health Outcomes International Ltd (“HOI”) to conduct a research project examining a range of different wage assessment tools, strategies and processes for people with a disability working in Business Services. In May 2001 HOI published a report entitled “A Guide to Good Practice Wage Determination”. The report recorded:

There has been a significant amount of research and development focused on the assessment and payment of ‘fair’ wages for people with disabilities. Until relatively recently, this work concentrated on people with disabilities in open employment settings. Previously, Business Services had tended to pay wages to employees based on historical arrangements or ad hoc assessment processes.

There is a large number of wage assessment and payment strategies that have been developed for workers with disabilities. The content, structure and rationale for these processes have varied significantly. For example, some wage assessment processes are rigorously researched, tested and published as organisational policies, whereas other systems are much less sophisticated and structured. There is an identified need to develop wage assessment processes for people in Business Services that are fair, appropriate to the worker, industry and the employer, use valid assessment techniques and comply with relevant legislation and standards.

Given that all Business Services in Australia are funded under the same system, it seems both logical and appropriate to develop guidelines that promote a nationally consistent wage determination system. Such a system is likely to ‘borrow’ from a range of current wage determination processes, but for some Business Services, is likely to represent a significant change in business operation.

39 The advantages and disadvantages of the SWS tool and other tools were discussed, as well as the general advantages and disadvantages of productivity models against competency-based assessment. The report also considered hybrid models which measure or assess both productivity and competencies. The conclusion was:

The research team concludes that a hybrid model represents the most appropriate method of wage determination in Business Services. However, the team is reluctant to recommend any of the existing assessment tools as the absolute best practice method of wage assessment for all services.

40 The report then said:

It is recognised that there is great variability in wage determination practice within the Business Service sector, and the research team was reluctant to recommend any single assessment process reviewed as suitable for application across the sector. It may be preferable, however, to design and implement a single assessment tool specifically for Business Services to enhance consistency in what is currently an extremely diverse sector.

41 It might be noted at this point that testing for, measuring or assessing competencies is not the same thing as testing for, measuring or assessing competency in a given task. The latter endeavour relates to skills, and the application of those skills. It may be expected to be reflected in some aspect of, or conclusion about, productivity. The former endeavour borrows from “industry standards”, so-called, usually found in training matrices or packages designed to provide increased recognition or avenues to higher pay. The idea of this kind of assessment is that an employee may be more “valuable” to an employer than a crude measure of productivity might suggest.

42 However worthwhile such an approach may or may not be in considering “work value” over a range of tasks of increasing importance, complexity or seniority, on one view the present case does not even enter that territory, at least so far as it applies in ordinary wage fixing terms. The present case is about the payment of a fraction only of the minimum possible wage rate in an award that is linked to the performance of the most basic of tasks.

43 That is not to gainsay the legitimacy, from a management perspective, of moving towards a more uniform mechanism for wage assessment which might allow the establishment of broad relativities across the Business Services sector. Obviously, such an endeavour is legitimate and probably worthwhile. However, it is not the issue presented by the current proceedings. In the current proceedings BSWAT was defended as directly applicable to the task of comparing the work value of an individual disabled worker in an ADE with that of an average Grade 1 worker, for the purpose of fixing a wage that was some fraction of the Grade 1 benchmark wage in the award. It is in that context that the matters at present in dispute must be resolved.

44 After presentation of its report in May 2001, HOI set about constructing a hybrid competencies and productivity wage assessment tool. In 2002 an early version of BSWAT was trialled. After the trial, revisions were made. They were made because the results in the initial trials suggested wage outcomes which were viewed by the authors as being too high. Trials of a revised BSWAT produced more modest results which were regarded as acceptable. In December 2002 HOI produced a final report entitled “Wage Tool for Business Services” which recommended the introduction of BSWAT. The HOI report stated “that the [BSWAT] is suitable for application in both open and supported employment environments”. The report predicted that “[a]n overall increase in income will be achieved by the vast majority of workers”. As the evidence in the present case showed, this prediction seems not to have been well-founded. Moves began to achieve an award variation to permit the use of BSWAT and other hybrid tools.

45 In 2005 the award was varied. The new provisions permitted assessment of wages in Business Services by a range of tools, not just those which assessed productivity. Clause 14 (including clause 14.3) was removed. The relevant replacement provisions were:

14. WAGE RATES

14.1 Upon appointment, an employee will be graded by the employer in one of the grades in Schedule A having regard to the employees skills, experience and qualifications.

…

14A. WAGE ASSESSMENT – EMPLOYEES WITH A DISABILITY

14A.1.1 ... an employee with a disability will be paid such percentage of the rate of pay of the relevant Grade in clause 14.2 as assessed by a wage assessment tool nominated in clause 14A.4 chosen by a supported employment service.

…

14A.4 Wage Assessment Tools

It is desirable that a wage assessment tool sought to be included in this award satisfy disability services standard 9 (Standard 9) and relevant key performance indicators as determined or approved under section 5A of the Disability Services Act 1986 (DSA KPI’s) as amended from time to time. The wage assessment tools described in this clause satisfy Standard 9 and the DSA KPI’s.

The following wage assessment tools can be chosen by a supported employment service to assess an employee with a disability:

14A.4.1 The Business Services Wage Assessment Tool, as defined by reference to the material contained in Exhibit B2 in Australian Industrial Relations Commission proceedings number C2004/4617;

…

14A.4.9 The Supported Wages System, as described in the decision of a Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, 10 October 1994, Print L5723; …

46 In total eleven possible wage tools were mentioned. At the time of the proceedings at first instance the number had grown to 22. Most of the tools measure or assess competencies as well as productivity. In the present case there was evidence that BSWAT is the single most common wage assessment tool used in ADEs. In open employment only the SWS tool continues to be permitted.

47 In those ADEs which adopted BSWAT, in order for employees to gain a wage increase it was no longer enough for them to increase their productivity alone. It was necessary to achieve a total score which would result in a higher percentage of the Grade 1 rate of pay than their existing wage rate represented. The argument put for the appellants in the present case is that the nature of BSWAT made it more difficult for intellectually disabled people to do this than for disabled workers who are not intellectually disabled. In particular, in the case of Mr Nojin and Mr Prior it has been contended that, in important ways, BSWAT did not measure their skill in their actual job.

48 Various reviews have been carried out since BSWAT was first approved for use. None recommended cessation of its use. Generally, use of BSWAT has been supported. However, it seems clear that no detailed or rigorous assessment of the use of BSWAT has been undertaken by reference to the particular concerns expressed in the present proceedings.

49 Importantly, in the 2005 version of the award, clause 14A.2.1 provided:

14A.2.1 No employee with a disability will have their rate of pay reduced as a result of a wage assessment made pursuant to clause 14A.1.1 as at 11 May 2008, or any variation of the award arising from the decision of the Commission in PR961607 [the award variation decision which permitted the use of BSWAT].

50 The effect of this provision was that existing employees, such as Mr Nojin and Mr Prior, could not have their wages reduced by the adoption or use of BSWAT. This has a particular significance for the way in which the appellants framed the requirement or condition which they alleged was indirectly discriminatory in the present case. I shall mention the issue again in that context.

51 In the judgment under appeal, the trial judge traced the development of BSWAT in detail. There seems no doubt that in the quarters charged with assessing how pay rates should be fixed for disabled persons, and amongst those charged with the development of an appropriate tool for that purpose, there was considerable (although by no means universal) support for the notion of a “hybrid” assessment involving measures of both productivity and competencies. The Australian Industrial Relations Commission appears to have been persuaded to acceptance of that philosophy, as does the union movement. Strikingly, representatives of intellectually disabled people represent the other side of the record.

52 The trial judge regarded the level of support for the use of BSWAT as very significant. He said at [86]:

86 A circumstance of great weight in the present cases is the history of the development of the BSWAT … The BSWAT has been developed specifically for the purpose of assessing the wages of disabled persons employed in ADEs. It has the approval of the Commonwealth. It has been endorsed by both the AIRC and the AFPC. It has been found to comply with Standard 9 of the Disability Services Standards. It has also been found to be in conformity with the Guide to Good Practice Wage Determination. Further, the BSWAT has received these endorsements with the support of the trade union that has had the carriage of applications to formalise and improve the methods of fixing, and the rates of, wages for employees with disabilities, the LHMU. The BSWAT is also supported by the trade union movement generally through the ACTU, employers generally, and employers in ADEs through ACROD.

53 The trial judge went on to refer to the differences of opinion amongst the experts, with which I shall deal in more detail in due course. There was a detailed evaluation of the criticisms made of BSWAT. The trial judge’s conclusions were expressed in the following paragraph:

98 In summary, the BSWAT has been developed as a tool for performing the very task for which it was used in assessing the wage levels of Mr Nojin and Mr Prior. It is not possible to set aside the very considerable support the BSWAT has in the ADE sector, or the considered opinions of consultants who have been called upon to examine the BSWAT, or to prefer the equally legitimately-held views of those who disagree with that body of opinion. The determination of wage levels for employees in ADEs by a method involving assessment of competencies is appropriate. So is the assessment of those competencies by means of question and answer, as well as observation. The disadvantages of the BSWAT arising from the “all or nothing” approach to each competency and the subjective nature of the assessments do not outweigh these considerations to the point of making such requirements or conditions as the BSWAT imposes not reasonable. Section 6(b) of the Disability Discrimination Act does not call for perfection. A system less than perfect can nonetheless be reasonable in the circumstances of a case. I cannot find that the requirements or conditions said to be inherent in the application of the BSWAT in the present cases were not reasonable.

Assessment of Mr Nojin and Mr Prior

54 Challenge began to use BSWAT when it was introduced in mid-2004. All supported employees other than Mr Nojin were assessed at that time. Mr Nojin’s representatives initially resisted a valuation of his work using BSWAT. Ultimately, an assessment was carried out in May 2005 and there was subsequently a further assessment on 12 August 2005. Prior to the first assessment Mr Nojin was being paid $1.85 per hour. At his first assessment his wage was assessed at $2.46 per hour, but in the subsequent assessment it was assessed at $1.79. In those circumstances his wage was maintained at $1.85.

55 One of the services offered by Challenge, in which Mr Nojin was employed, was secure document destruction. There were some other services also offered on a fairly small scale. As described by the trial judge, Mr Nojin was asked to perform three tasks during his BSWAT assessments:

pamphlet collation, which involved inserting flyers into pamphlets, the flyers and pamphlets already being on hand; pen assembly, which involved fitting a ballpoint ink insert into a wooden pen casing, with the inserts and casings already on hand; and feeding one crate of pre-sorted documents through a mechanical shredder.

56 The tasks were simple, repetitive and involved no element of decision-making. There was no need to apply abstract concepts to the work that was being done. The work was, in each case, work that involved simple physical manipulation of limited items.

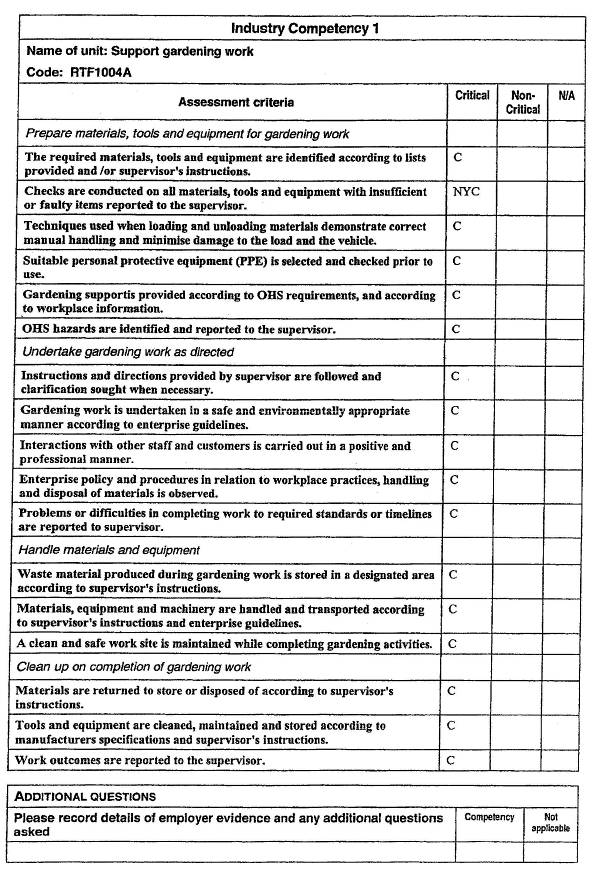

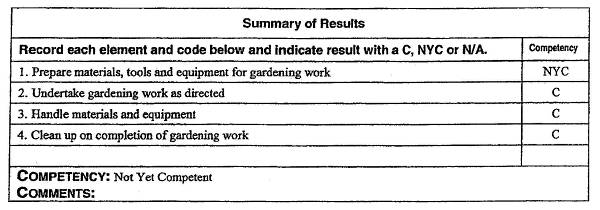

57 SIS had 20 people in supported employment and another 75 people in day programs. One of the services that SIS offered with its employed workers was essentially a lawn mowing business. The employees were engaged in “whipper snipping, lawn mowing, raking and mowing and general maintenance work around people’s gardens”.

58 At the time of his first assessment, Mr Prior’s time was split evenly between mowing lawns and some other general gardening tasks. At the time of his second assessment, 90% of Mr Prior’s time was spent actually mowing lawns, and 10% of his time was spent raking and disposing of leaves. Mr Prior worked under direct supervision. His productive effort was measured by timing him. For example, Mr Prior took 14 minutes and 10 seconds on his first assessment to mow a 5 x 10 metre area of lawn (with the catcher on correctly). The comparator, his supervisor, took 9 minutes to mow a similar area. Again, in Mr Prior’s case, the routine and relatively simple nature of the tasks he was required to perform may be seen.

59 Mr Prior left SIS on 9 August 2008 and now works in open employment at Stawell Dry Cleaners. He is regarded as an excellent employee in that position. He is earning about five times his assessed wage under BSWAT.

60 BSWAT provided a means of measuring and assessing productivity and competencies. Each counted for 50% of the final assessment. So far as it measured productivity, BSWAT was similar to the SWS tool. No complaint is made about that aspect of its use.

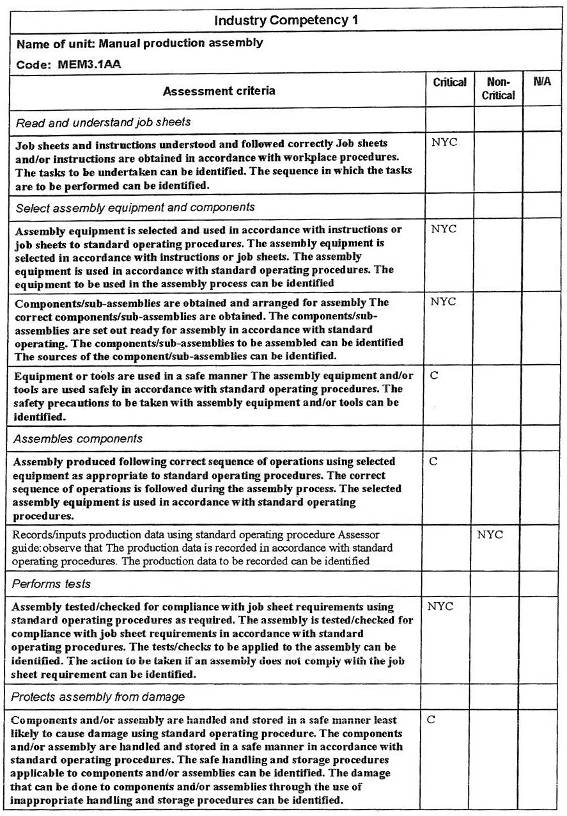

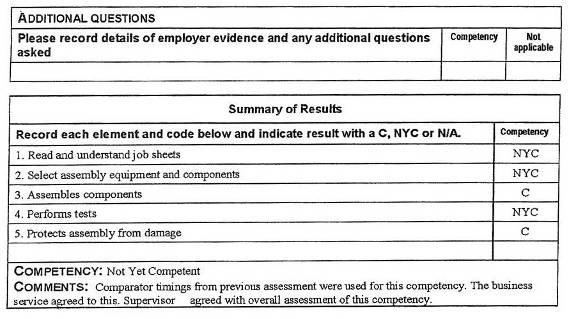

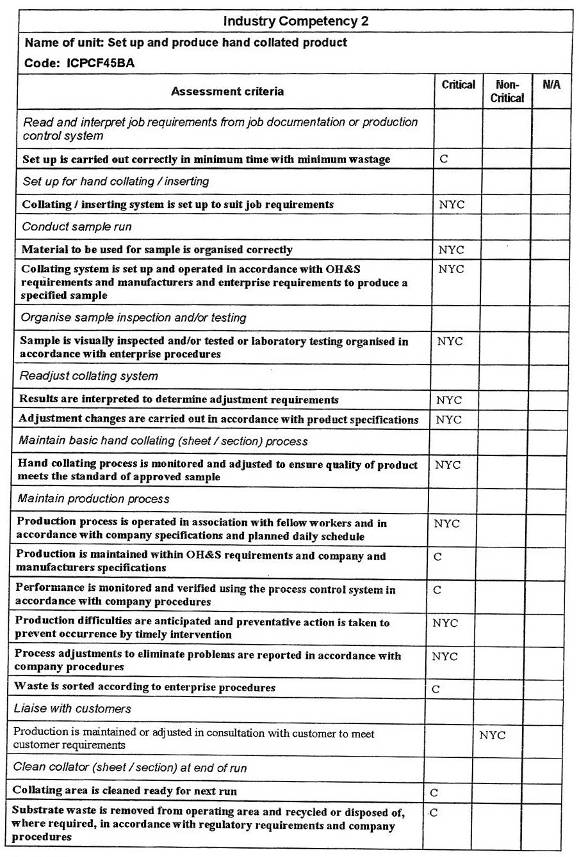

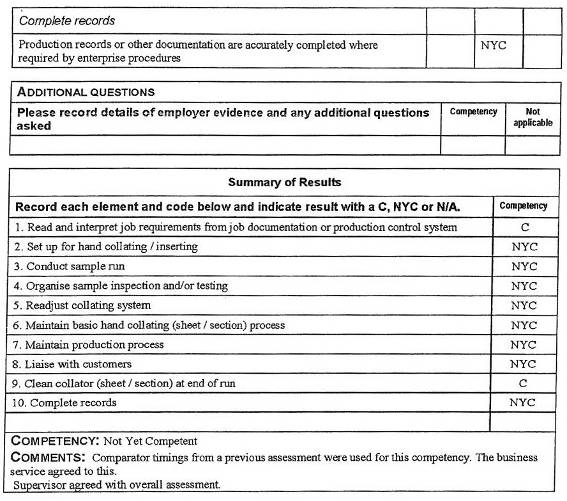

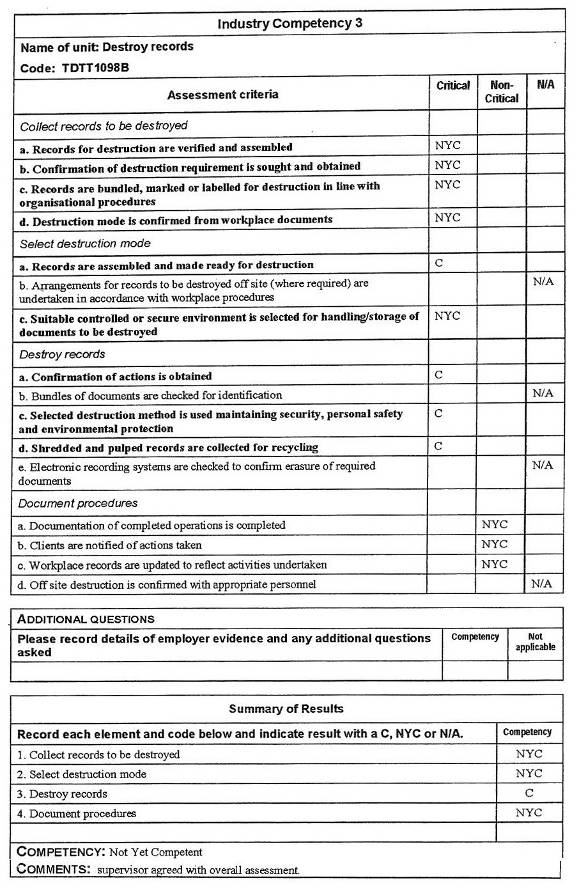

61 So far as it measured competencies, BSWAT dealt with two areas of competencies: core competencies and industry competencies. There were four core competencies and four industry competencies. For each unit of competency questions were provided to the assessor, together with indicative areas of acceptable response. The details will be appreciated from a study of the relevant forms, which will be set out shortly.

62 All the questions and assessment criteria under each core competency were classified as “critical”. The significance of this was that an incorrect response to any of those questions or criteria resulted in an assessment of “not yet competent” (“NYC”) for that core competency. In other words, an incorrect response to a single question or criterion under any of the core competencies would result in a score of 0 for that competency, irrespective of how many of the remaining questions were answered correctly. This aspect of BSWAT was referred to in the evidence as “all or nothing”. Having regard to the fact that there were eight competencies to be scored, and that the competency component comprised 50% of a worker’s overall score, each competency carried a final value of 6.25%.

63 In relation to industry competencies, the position was more complicated. First, it was assumed that every job done by a disabled worker could be measured against at least four “industry” competencies. An industry competency could be applicable provided at least one person in the workplace was required to exercise it, whether or not the employee in question was required to do so. If four industry competencies could not be identified and tested in this way, any shortfall (i.e. 6.25% each time) was simply scored 0. Mr Nojin was assessed against only three identified industry competencies (losing 6.25% from his final score at the outset). Mr Prior was tested against only one identified industry competency (losing 18.75% from his final score at the outset).

64 The second complication was that not every question or assessment criterion under each industry competency was classified as “critical”. Although most questions and criteria were regarded as critical, a number were classified as “non-critical”. An assessment of NYC for a non-critical component would not prevent the worker from being assessed as “competent” (“C”) overall for that unit of competency. Nevertheless, in order to score at all for an industry competency, it was necessary to be scored C on every “critical” element of an industry competency.

65 Using this approach Mr Nojin obtained a C score for one core competency (6.25%), NYC for three core competencies (0 each), NYC for three industry competencies (0 each) and 0 for the non-existent fourth industry competency. Mr Prior scored NYC for each of the four core competencies (0 each), NYC for one industry competency (0) and 0 for three non-existent industry competencies. In Mr Prior’s case, this meant that he scored 0 for competencies, with the result that his productivity score was effectively halved to reach his overall score.

The core competencies

66 Reproduced hereunder are the forms used when applying BSWAT to assess core competencies, as reproduced in the judgment of the trial judge.

| Follow Workplace Health and Safety Practices | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Conduct Work Safely | |

| • Protective clothing or equipment is identified and used appropriately | |

| • Basic safety checks on equipment are undertaken prior to operation | |

| • Set up and organise work station in accordance with OH&S standards | |

| • Follow safety instructions | |

| • Manual handling tasks are carried out accurately to recommended safe practice | |

| • Waste is disposed of safely in accordance with the requirements of the workplace and OH&S legislation | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What do you do if you or someone else hurts themselves at work? • Tell supervisor • Get help e.g. Nurse, ring ambulance, get first aid officer • Turn off machinery, remove from danger | |

| Why do you use/wear protective clothing or equipment? • noise • using machines • working with pesticides/chemicals • dust • sun | |

| What would make your workplace unsafe? • spills • faulty equipment • poor surfaces etc (refer to range of variables) | |

| What do you do when you notice something is unsafe at work? • remove the hazard • report to appropriate personnel • fill in relevant documentation | |

| What do you do if the fire alarm goes off? • exit the workplace following evacuation procedures • assemble in designated area • wait for further instructions | |

| Why is it important to follow evacuation procedures? • ensures orderly evacuation • workplace can be assessed for safety • all employees can be accounted for | |

| What are some of the ways you move objects in the workplace? • manual lifting • trolley • pallet jack • forklift | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments: | |

| Communicate in the Workplace | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Gather and respond to information | |

| • Instructions are correctly interpreted | |

| • Clarification is sought from appropriate personnel when required | |

| • Workplace interactions are conducted in a constructive manner | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What work have you been asked to do today? • Clarify work requirements with supervisor | |

| In what order should the work be completed? • Clarify work requirements with supervisor | |

| What do you do if you are unsure about what work needs to be done? • Clarify with appropriate person | |

| What workplace meetings do you attend? • OH&S • Work performance/review/Individual Employment Plan • Work group/staff meetings • Union meetings | |

| What are these meetings for? • Worker to describe role and function of different meetings | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments: | |

| Work with others | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Participate in group processes | |

| • Co-workers’ individual differences are taken into account eg. o Respect for others’ personal space and property, o Cultural, physical and/or cognitive differences are respected, o Tolerance of others in the workplace. | |

| • Worker adapts to changing work roles (observe worker in different roles to confirm) | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| What are some other jobs that people do here? • Has an understanding of what other workers do in the workplace | |

| How can you help others at work? • Do own job well • Be on time, keep area clean and tidy • Help others when they require it (e.g. busy, complex work, etc) • Make suggestions for improvement | |

| If you had a disagreement with someone in the workplace, what would you do? • Discuss it with the person • Ask for assistance from your supervisor • Make a formal complaint | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments: | |

| Apply quality standards | |

| Workplace Observation | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| Assess quality of own work | |

| • Work instructions are followed and tasks performed in accordance with quality requirements | |

| • Non compliant materials or products are identified and isolated | |

| Questions | |

| Assessment criteria: | Scoring |

| How do you know if a part/service is faulty? • Can describe non-compliant products/services | |

| What do you do if the part/service is faulty? • Isolate non-compliant part • Report to supervisor • Document, where necessary • Identify causes and possible solutions | |

| Why is it important not to make too many mistakes? • Waste materials • Waste time • Possibly damage equipment • Poor customer service | |

| Additional Questions | |

| Please record details of employer evidence and any additional questions asked | Scoring |

| Competency: Comments: | |

67 In both his initial BSWAT assessment and his reassessment, Mr Nojin was assessed as competent for “Follow Workplace Health and Safety Practices”. For “Communicate in the Workplace” he was assessed as competent for each element except “What workplace meetings do you attend?” and “What are these meetings for?”. Accordingly he scored 0 for this competency. Evidence was given at the trial by Mr Ian Wade, who at the relevant time was the General Manager of Challenge, to the effect that Mr Nojin in fact attended and participated satisfactorily in such meetings. Mr Nojin’s failure to respond adequately to questions about the issue is apparently what told against him. In relation to “Work with others” Mr Nojin was scored C for every element except “What are some other jobs that people do here?”, a matter which is not self-evidently of much importance to his assigned tasks, in light of his satisfactory response to the other questions. He scored 0 for this competency as a result. Mr Nojin also scored 0 for “Apply quality standards” although he was observed to satisfactorily carry out his assigned tasks and satisfactorily answered the question “What do you do if the part/service is faulty?”.

68 Mr Prior’s responses to questions about the four core competencies are set out in the judgment under appeal at [20]-[27]. In both his first BSWAT assessment and his reassessment, Mr Prior was scored NYC on each one. For “Follow Workplace Health and Safety Practices” Mr Prior answered all questions satisfactorily but failed, in the observation of the assessors on each occasion, to carry out all the necessary safety checks and preparatory steps. Mr Prior is legally blind as well as intellectually disabled. His equipment is checked by a supervisor. He is not expected to check it himself. The respondents relied on the fact that the difficulty here did not relate to Mr Prior’s intellectual disability but to his physical disability. Even if that proposition is accepted, it does little to instil confidence in the reliability and practicality of the assessment required under BSWAT.

69 As to the second core competency Mr Prior was assessed, by two assessors, to satisfy all elements except the observational criterion “Instructions are correctly interpreted”. In each case Mr Prior was observed to require instructions to be repeated as he is forgetful or becomes confused. Evidently, as required, Mr Prior did deal capably with his intellectual disability by seeking clarification when required. His was a task that was, in any event, performed under supervision. This gap between reality and theory cost Mr Prior a further 6.25% in his final score.

70 It would be unproductive and unduly time consuming to simply replicate further the summary made by the trial judge. Some of Mr Prior’s difficulties appeared to arise from his impaired eyesight; some arose from his intellectual disability. Those which arose from his impaired eyesight saw him marked down for things he was, in fact, not required to do. Those which arose from his intellectual disability penalised his inability to respond adequately to questions which did not affect the work he actually did, such as “How can you help others at work?”, to which Mr Prior responded (apparently inappropriately) that he would try not to get involved. After some prompting Mr Prior said he would help them finish the job. This was apparently not regarded as an appropriate response either.

71 I accept that the issues in the present case may not be resolved by reference to any concern about the way in which the BSWAT assessment was actually carried out in Mr Prior’s case. The concern I have is a more fundamental one than that. The assessment required by BSWAT explored matters with which, on the expert evidence to be referred to later, intellectually disabled people would struggle. Mr Prior’s difficulties in this area cannot fairly be attributed to his blindness. The matters I have referred to are practical examples that give direct support to the criticisms made by the appellants of the use of BSWAT.

Industry competencies for Mr Nojin

72 Mr Nojin’s three selected industry competencies were (and were assessed in his initial BSWAT assessment) as follows:

73 Mr Nojin achieved identical industry competency scores in his reassessment. Mr Nojin was assessed NYC on all three competencies. The expectations inherent in these assumed competencies may readily enough be compared with the three simple and repetitive tasks that Mr Nojin was actually required to do, and which were measured in the productivity side of the BSWAT assessment.

74 On his first assessment Mr Nojin’s tasks were: pamphlet collation (40%); pen assembly (10%); and document shredding (50%). On his second assessment his tasks were: pamphlet collation (40%); pen assembly (10%); preparing documents for shredding (30%); and document shredding (20%). The trial judge found that the increased complexity of the additional tasks “dragged down” Mr Nojin’s productivity score from 27.48% to 16.54% (on the productivity side of the BSWAT assessment alone). It may be seen that, even on the productivity side, Mr Nojin struggled to approach anything near 100% of the productivity of an average Grade 1 worker. It does not seem surprising, in light of the fact that Mr Nojin’s diminished productivity may be seen as the consequence of his intellectual disability, that he was also unable to present as universally competent in each of the “critical” aspects of the three “industry” competencies. Some of those elements appear to me to assume capacities that Mr Nojin self-evidently does not possess. If that is so he was condemned to failure by the very content and nature of the test, with the result that all opportunity to score above zero in the area of industry competencies was denied to him in advance of his actual assessment.

Industry competencies for Mr Prior

75 Mr Prior’s single selected industry competency was (and was assessed in his initial BSWAT assessment) as follows:

76 The result here is striking. Mr Prior scored 0 because he did not carry out checks. This seems fairly clearly to be the result of his physical handicap, as the respondents submitted. It also appears to be the same deficiency that told against him in relation to the first core competency. I accept that this may represent an example of BSWAT operating against the interests of a worker with a physical disability, but the issue in the present case does not turn on whether such workers are, in some circumstances, also disadvantaged by BSWAT. In both his initial BSWAT assessment and reassessment Mr Prior did not achieve a score on any competency, core or industry. Those failures are not all attributable to his physical disability. It is an aspect of BSWAT, in its application to Mr Prior, that his assessed productivity score of over 50% was halved due to Mr Prior scoring 0 on the competency side of his BSWAT assessment. As I conclude later, the very use of BSWAT, with those outcomes and consequences, must be assessed by reference to its impact on the capacity of intellectually disabled workers to respond effectively to it.

The expert evidence

77 The trial judge received expert evidence from four people. One expert witness was Ms Louise Boin, a neuropsychologist whose evidence was, in all relevant respects, accepted by the trial judge as unchallenged. I refer to it later. The other three experts gave evidence concurrently. They each provided a written report, they contributed to a joint document disclosing the extent of their agreement and disagreement, and they gave oral evidence concurrently.

78 Mr Richard Giles is a principal of Evolution Research and was engaged by HOI as a consultant at the outset of the project to develop a wage assessment tool for Business Services. He was one of the persons who developed, tested and refined BSWAT. He is a staunch supporter of BSWAT and of the notion embedded in it that it is legitimate, practical and relevant to assess competencies as well as productivity when fixing wages for disabled workers. The competencies included in BSWAT were developed by reference to “industry based competencies” drawn from a range of industry training packages. Mr Giles’ written report said:

Competency based wage assessments focus on the abilities of the person being assessed without necessarily focusing on their productivity or the speed with which they undertake tasks. Competency based assessment is the foundation of industry led training programs and as such is seen as a critical component of wage assessment for the Business Services sector.

79 As I indicated earlier, during the development of BSWAT an initial trial of the draft wage tool in 19 Business Services sites produced results which were regarded as yielding wage outcomes that were too high. The tool was revised. A number of changes were made. One change was to more closely align the competency-based component with a Certificate II level of competency rather than a Certificate I level, thus raising the standard to be satisfied. Mr Giles justified the changes in his written report in this way:

An initial trial of the draft wage tool in 19 Business Service sites in four different states showed that whilst the productivity element was appropriate, the competency element did require refinement. In effect, the competency based component was seen to be too rudimentary for operation in a number of the industry settings. This was effectively a change in the ‘pitch’ of the competency based components and led to them being more closely aligned with a Certificate II level of competency rather than a Certificate I level. It was agreed by the project team and by the steering group that this was a more accurate reflection of a full wage earner in an open employment setting, and where their skills were expected to be.

80 The Australian Quality Training Framework (“AQTF”), which was referred to frequently in the expert evidence, is part of the National Training Framework. It was used, for example, in the TAFE (Technical and Further Education) systems. It assisted the construction of course curricula and training packages. AQTF is built into the Australian Qualifications Framework (“AQF”) which is a quality assured national framework of qualifications in the school, vocational education and training, and higher education sectors in Australia. The 10 level system spans the range from Certificate I to a doctoral degree (eg. Ph.D). Certificates I and II levels refer to training for basic vocational skills and knowledge, post-secondary school. Assessment by reference to Certificate II levels rather than Certificate I therefore assumes, first, knowledge and competency transmitted usually by some post-secondary school training or experience, and achievement at least part way up the scale which the overall scheme reflects.

81 Evaluation of the standard of knowledge, understanding and ability to communicate that knowledge and understanding at a Certificate II level (i.e. a little under the level in some trade courses) was bound, on the expert evidence in the present case, to present a further disadvantage to intellectually disabled people. This is a matter to which some of the experts directed particular attention.

82 Mr Giles explained the units of competency which were chosen for BSWAT in the following way in his written report:

17. d. (i) … the competency assessment component incorporates four core units of competency. They are occupational health and safety, working with others, communication in the workplace, and applying quality standards. During the design phase of the BSWAT it was found that these core units of competency (with different titles in different industry training packages) are common to all industries. As such, these were considered to reflect the range of skills and knowledge applicable to all workers in any setting.

The core units of competency in the BSWAT therefore reflect an amalgamation of relevant performance criteria from a range of industry training packages. Assessment of the core units of competency are made by a combination of direct observation, questioning and the review of third party evidence. In order to streamline the assessment process, the core units of competency include those performance criteria deemed most critical to the performance of duties in the Business Service environment. As such, they are all deemed critical, and to achieve competency in each of these units all performance criteria must be achieved.

17. d. (ii) Up to four industry-specific units of competency are chosen in accordance with the tasks performed by the worker. It is recognised that not all workers perform a range of duties broad enough to allow for the selection of four industry-based competencies, but based on the review of industry expectations it was deemed that a worker in an open employment setting, (i.e. achieving a full award rate of pay) would be expected to perform at least four industry-specific competency duties.

(Emphasis added.)

83 Two matters might here be noted. First, development of core competencies using industry/training packages (if that is what in fact occurs) is not the same as expecting that, and assessing whether, such competencies are possessed by an individual who will only receive some fraction of the award wage rate for the lowest work grade contemplated by the award. The two concepts are not necessarily in the same field of examination. Secondly, any concept of “industry expectations” must be adjusted to the practical circumstance, already mentioned on a number of occasions, that what is required to be assessed is what percentage of a rate of pay at the minimum award level a disabled worker should receive for performing tasks that are, by their very nature, basic and routine.

84 Mr Paul Cain is the Director of Research and Strategy at the National Council on Intellectual Disability. In his report he recorded that the initial BSWAT trial involved 83 participants. In that trial, the average competency score was higher than the average productivity score (64%:46%). That provided an overall score of 54%, resulting in an average wage of $6.11 per hour. In a revised trial involving 81 participants, after the adjustments referred to by Mr Giles, the average competency score dropped below the average productivity score (26%:43%) providing an overall score of 34% and a reduced average hourly wage of $4.13. Data current to October 2008 showed that the ratio had declined again, with average competency as tested by BSWAT now well below average productivity (8%:38%), producing an average overall score of 23% and an average hourly wage of $3.20. Mr Cain recorded that the actual average hourly wage of initial trial participants in 2002 was $3.42 compared to $3.20 for those assessed by BSWAT in 2008. That is, on a comparison of actual hourly wage data, average wages have actually fallen between 2002 and 2008 and are certainly much lower than the indicators given by either of the trials. Mr Cain made the following points in his written report:

118 There is incoherence between the BSWAT assessment scores of productivity and competency. The lack of correlation between BSWAT productivity and competence scores is concerning given the assumption that skill generates productivity. There should be a strong correlation between the competency scores and the productivity scores. The lack of such a correlation suggests that there is a flaw in the BSWAT design.

…

122 The competency component of the BSWAT bears little relationship to the productivity assessment and operates to diminish wages for employees with disability. The lack of relationship with the competency assessment to actual work tasks suggest that the BSWAT competency component is measuring skills and knowledge not directly relevant to the job tasks that employees are employed to perform.

…

129 In my review of the employment literature for people with intellectual disability, I am unaware of any method where on-the-job competency or productivity of people with intellectual disability is measured by interview or via vocational assessments. The literature is invariably concerned with the training of discrete job tasks towards an employer agreed standard of quantity and quality. Performance data is collected during training to track outcomes and to assist a review of the effectiveness of instructional techniques. An interview is not evidence of competence or productivity in the completion of a job task. People with intellectual disability will struggle with question and answer tests that require effective communication and comprehension. Many people with intellectual disability will find a formal interview difficult and intimidating.

(Emphasis added.)

85 Mr Cain also pointed out that in research carried out by Mr Giles’ own team, Evolution Research, it was revealed that the notion incorporated in BSWAT of a fixed four industry competency units did not accord with reality at the wage level taken as the starting point for assessment of pay in ADEs. Under BSWAT arrangements competencies must be identified which have a counterpart in industry. If four industry competencies against which a worker can be assessed cannot be identified, the worker’s score is automatically discounted to reflect the absence of competency. This is despite the fact that in open employment non-disabled workers at the Grade 1 level were found to have, on average, only 2.8 competencies. Mr Cain pointed out:

101 If BSWAT were to be applied to comparable jobs in open employment, the average worker with 2.8 competencies would have their wages discounted below the award wage. The average workers would only be able to meet a maximum of 2 industry competencies. Workers would be given a ‘0’ for two industry competencies as the BSWAT demands 4 industry competency units to be included in the wage calculation. The workers would have their award wage discounted by at least 12.5% …

102 The BSWAT applies an industry competency assessment that is not comparable to standards of award based wages in open employment by expecting workers with disability to meet a higher number of industry specific competencies than people without disability.

86 Mr Phil Tuckerman is the Director of Jobsupport, an organisation that provides vocational training, placement and ongoing support services for people with an IQ less than 60. He has been closely involved in the development of wage assessment tools including the SWS tool, which is widely used for intellectually disabled persons and persons with other disabilities in open employment. His written report included the following:

35 The weighted productivity assessment used in the Supported Wage System [the SWS tool] is strictly productivity-based. Workers with a disability are assessed to compare their output relative to that of non-disabled co-workers on the tasks that make up their job. In the Supported Wage System there is no separate rating or discounting for ‘competency’, or to reflect the fact that the range of tasks which the disabled worker is able to perform is likely to be more narrow than the range of tasks performed by a non-disabled co-worker. The Supported Wage System uses the lowest pay classification under the relevant award or agreement that contains all the tasks performed by the worker.

36 The Supported Wage System ensures that the employer pays a worker with a disability exactly the same amount that a non-disabled co-worker on the same award or agreement classification would receive for producing the same volume of work.

37 I was a member of the reference group for the 2001 Supported Wage System Review. The review found that both employers and workers with a disability were satisfied with the Supported Wage System approach.

38 [Data current to October 2008 collected by the Department of Family and Community Services showed] BSWAT competency scores far lower than productivity scores. Surely if the competencies were relevant to the job they should have been trained to criteria prior to the BSWAT assessment. The low competency scores raise questions about the relevance of the competencies, the adequacy of the training services provided for their workers with a disability on the competencies and the methods used to assess the competencies.

87 Prior to giving oral evidence the three experts produced a joint document. The joint document identified areas of agreement and disagreement.

88 Mr Giles’ views were referred to in the following terms:

Richard Giles rejects that positions held by people with disability are only process oriented positions, limited in their scope and can only be assessed by productivity. Many positions held by people with disability are positions where knowledge and skill is key. These positions offer diversity and interest to the person with disability and move away from the notion that positions filled by people with disability can only be process driven.

Assessment of productivity fails to identify and reward a person’s level of skill, flexibility and worth to the organisation …

…

The BSWAT provides a balance that recognises the two fundamental aspects of work – competency and productivity. Competency is not a discounting of a person’s wage unless there is an inherent expectation that a person with disability is not capable of achieving this. I find this perception difficult to accept, as I know of and can provide evidence of many people with disability who can achieve the level of competency outlined in the BSWAT. Having an intellectual disability does not automatically preclude a person from having the ability to achieve competency.

(Emphasis added.)

89 Mr Tuckerman and Mr Cain expressed their views quite differently:

Phil Tuckerman and Paul Cain believe their role, as expert witnesses, is to give evidence relevant to the claims raised by the applicants. The applicants are people with intellectual disability performing process-based work. We have therefore confined our comments to matters relevant to this population and this type of work. Issues such as how workers with disability are paid to perform knowledge-based jobs within a productivity based wage system are not relevant to this case.

Phil Tuckerman and Paul Cain argue that an Award rate of pay only requires employees to achieve the volume of productive output in terms of quantity and quality per job task as agreed by the employer.

The productive output required is determined by comparison to the volume of productive output achieved by an employee paid the full award rate for completing the same job task.

It is important that any sub-award wage calculation results in the person with disability receiving the same income for the same volume of work output that a co-worker without a disability on the same award level would receive. This is the basis of the Supported Wage System (SWS).

…

We reject the notion of discounting wages for jobs with a narrow range of tasks. Jobs performed by people with and without disability in the regular labour market for award rates of pay contain a range of tasks from narrow to broad. A multi-skilled job, or a job with a broad range of tasks, is not an Award requirement or an employer standard.

…

… the AQTF system of competency is not a universal standard applied by employers as the BSWAT asserts. Employers are most concerned with productive output rather than the meeting of competency assessments. We consider it unfair for a pro-rata award wage assessment to expect people with disability to meet standards not applied to all workers doing the same work at the same Award classification.

Competency assessment has poor correlation with productive value and can distort wage outcomes to the detriment of employers and employees.

…

The majority of the people whose wage is determined by pro-rata award wage assessment tools are people with intellectual disability. Both applicants in this matter have intellectual disability. The majority of the jobs that this population perform are process jobs, not knowledge based jobs, due to the impact of their disability.

(Emphasis added.)

90 These observations by Mr Giles, and by Messrs Tuckerman and Cain, raise an important point for the present case. The present case is about Mr Nojin and Mr Prior. In some respects their circumstances must remain in focus. However, any examination of whether it is reasonable to use BSWAT, even in their cases, cannot be undertaken without an appreciation of the more general context.

91 That said, in my view the differences between the experts reveal a more fundamental disagreement about how to evaluate work which must, under the award, be measured by reference to a known benchmark. That benchmark is process oriented. It involves minimal decision making. It is not knowledge based. In my view, those circumstances require less weight to be given to Mr Giles’ opinions than to the shared opinion of Mr Tuckerman and Mr Cain.

92 Disagreement about competency assessment is reflected in the following entries in the joint report:

4.1. AQTF Industry Competency

There is disagreement about the use of industry competency assessment for the purposes of a pro-rata award based wage assessment.

Richard Giles submits that the AQTF industry competencies have been developed by industry to promote correct processes and safety within the workplace. BSWAT competencies are set at certificate level 2 and would be attainable by employees earning the full award rate in the open labour market. He also submits that this level of competency would be reflective of a base level expectation by employers for payment of a full award rate of pay.

…

Paul Cain and Phil Tuckerman, as stated above, reject the AQTF industry competency assessment as a valid assessment of pro-rata award wages. The fact that employers do not apply AQTF industry competencies to all employees at entry and low award level jobs makes it inappropriate that this standard be uniformly applied to employees with disability to determine an award-based wage. It is reasonable, however, to expect skills required by the employer, directly related to the job, to be trained with the assistance of an employment service provider.