FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 190

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| TPG INTERNET PTY LTD (ACN 068 383 737) Appellant | |

| AND: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed in part.

2. The parties are directed to bring in a minute of proposed relief within a date to be fixed by the Court.

3. In the event that the parties cannot agree the terms of such a minute, there will be liberty to apply to relist the appeal for the parties to make submissions on the question of penalty and consequential relief, if any.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | VID 455 of 2012 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | TPG INTERNET PTY LTD (ACN 068 383 737) Appellant |

| AND: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Respondent |

| JUDGES: | JACOBSON, bennett & gilmour JJ |

| DATE: | 20 December 2012 |

| PLACE: | sydney |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 The principal issue which arises in this appeal is whether the primary judge was in error in finding that advertisements published in the course of a substantial advertising campaign were misleading and deceptive. The advertisements were published by the appellant, TPG Internet Pty Ltd (TPG).

2 TPG is a member of the TPG Telecom Limited group of companies which carry on business as providers of telephone and internet services to residential customers throughout Australia. One of the services provided by TPG is an asymmetric digital subscriber line (ADSL) broadband service known as ADSL2+.

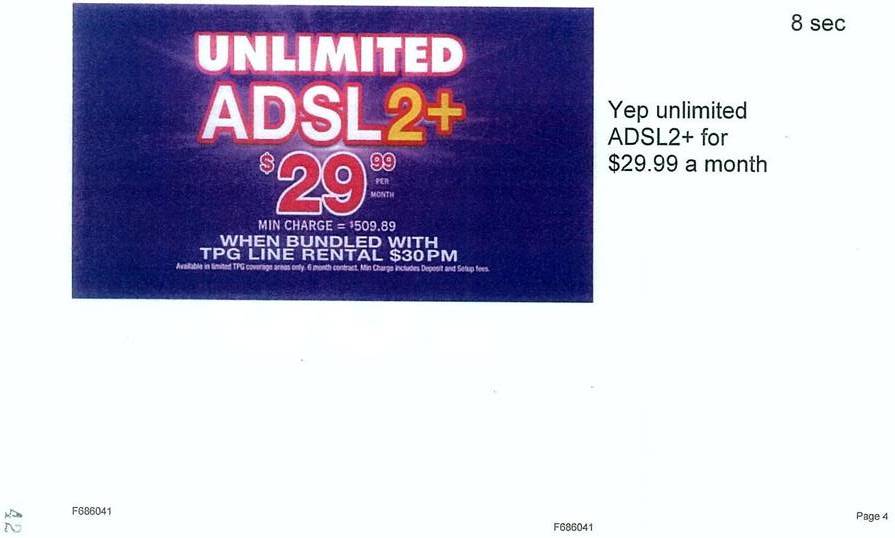

3 The ADSL2+ service is offered under a number of different types of plans under which customers may subscribe to the service. One such plan is offered without download limits and is therefore attractive to broadband users. In the language commonly used by suppliers and consumers of such services, it is known as unlimited ADSL2+.

4 In order to use the ADSL2+ service, a consumer requires an active home telephone line to provide broadband connection to the internet.

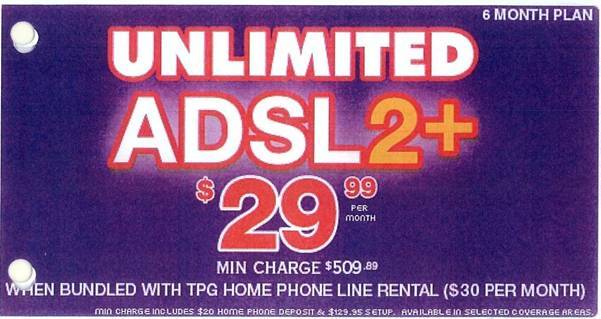

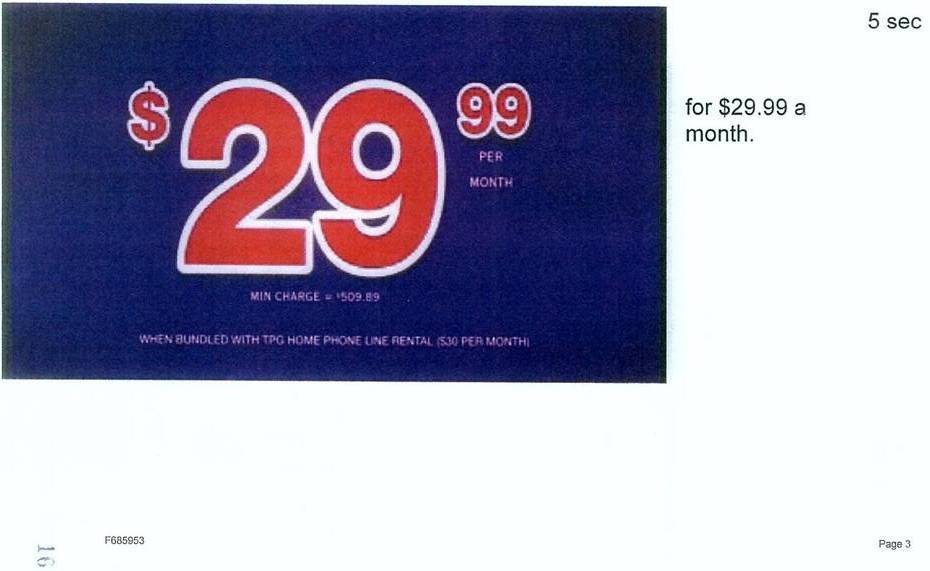

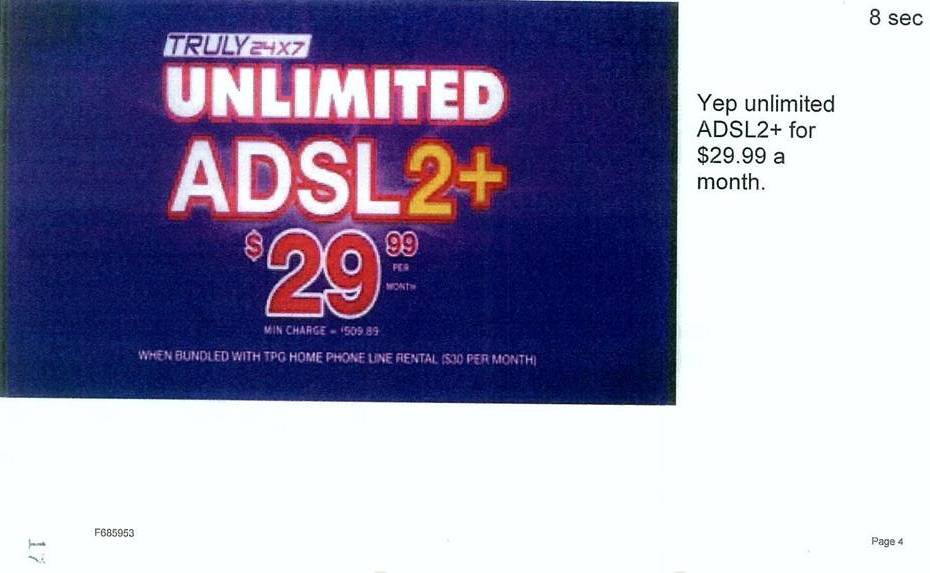

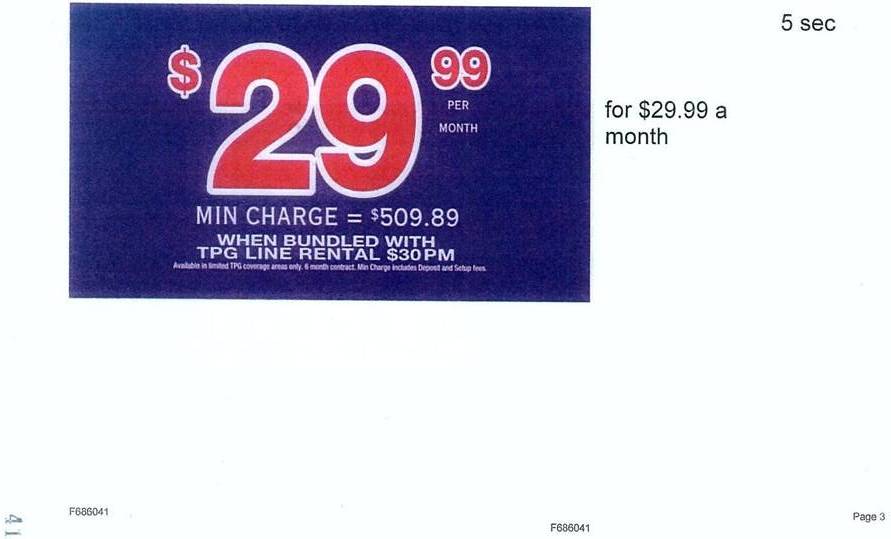

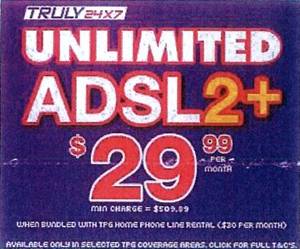

5 In September 2010 TPG launched a national advertising campaign for ADSL2+ in which it highlighted, as a principal feature in each form of advertising media used in the campaign, an offer to provide customers with unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 per month.

6 The advertisements went on to say, although in a less prominent manner, that the advertised rate of $29.99 per month, was only available to persons who bundled the ADSL2+ service with a home telephone line from TPG at an additional $30 per month.

7 In early October 2010, shortly after the commencement of the advertising campaign, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) wrote to TPG expressing a number of concerns about the form of TPG’s newspaper advertisements. The ACCC’s principal concern was that the bundling condition was said to have been stated in small, difficult to read print, which was insufficient to qualify the “dominant headline representation” in TPG’s advertisements.

8 The ACCC therefore considered that TPG’s advertisements amounted to misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the Act) and that the advertisements contained false or misleading representations as to the price of services in breach of s 53(e) of the Act.

9 In addition, TPG’s advertisement stated in what the ACCC considered to be fine print, that the “min charge” for the advertised service was $509.89. This minimum charge came about because the $29.99 monthly rate was only available to customers who entered into a contract for a minimum of 6 months. The sum of $509.89 consisted of the monthly fee for ADSL2+ for 6 months together with telephone line rental for the 6 month period as well as a set up fee of $129.95 and a deposit of $20 for telephone call charges.

10 The ACCC considered that the manner in which the minimum charge was displayed in the advertisements may also constitute contraventions of the provisions of the Act referred to above as well as a contravention of s 53C of the Act. That section required TPG to specify the minimum charge “in a prominent way” as a single figure. The ACCC was of the view that the sum of $509.89 was not displayed in a prominent way as required by that section.

11 Shortly after it received notice of the ACCC’s concerns, but without accepting the correctness of them, TPG amended the form of all of the advertisements used in the first three weeks of its advertising campaign. That phase of the campaign lasted from 25 September 2010 to 7 October 2010. It comprised advertisements that were published on national television stations, capital city radio stations, national and capital city newspapers and on the internet. We will refer to the advertisements that were published in this phase of the campaign as “the initial advertisements”.

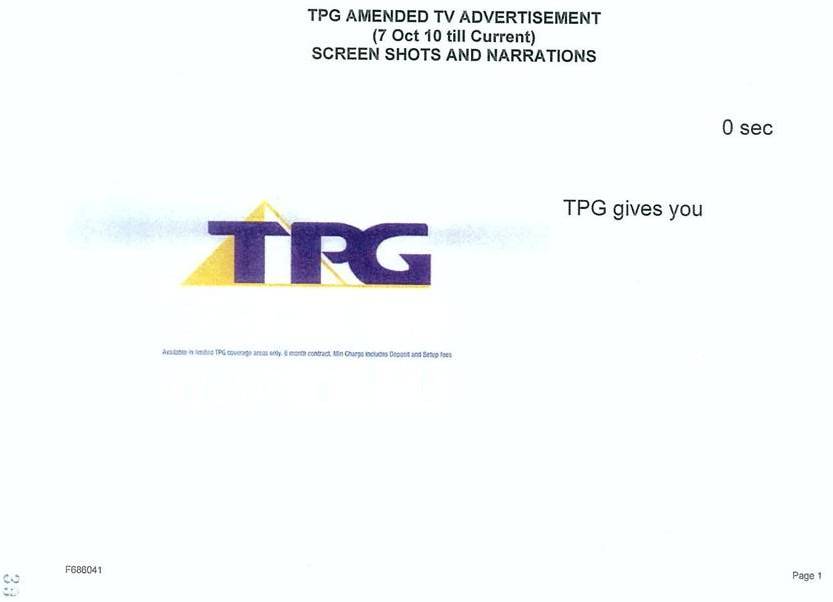

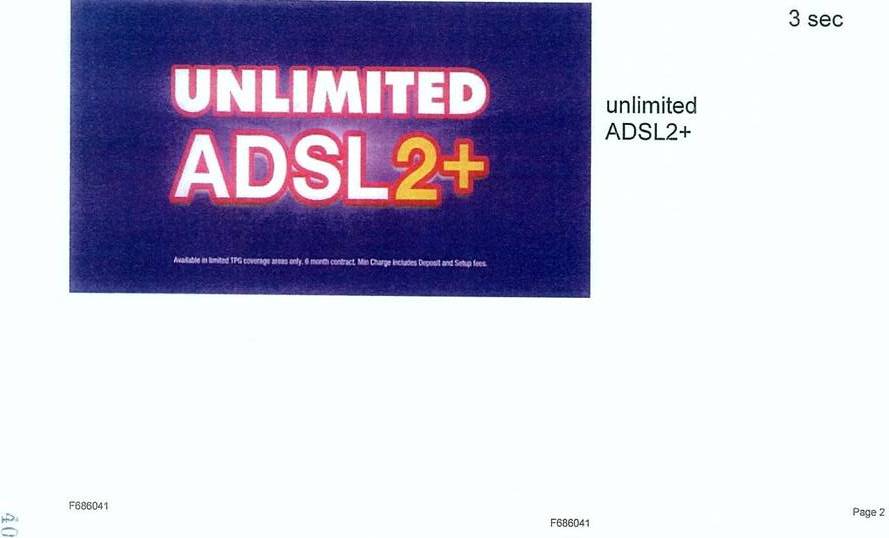

12 The second phase of TPG’s advertising campaign ran from 7 October 2010 and continued for a period of approximately 13 months. The campaign was expanded beyond the media employed in the first phase of the campaign to include advertisements published in brochures, as well as on public transport and billboards.

13 The amended advertisements published by TPG in the second phase of the campaign were intended to meet the ACCC’s complaints about the form of the initial advertisements. We will refer to the amended form of the advertisements as “the revised advertisements”.

14 TPG’s advertising campaign was extensive. The total sum expended by TPG in the various forms of media in which the advertisements were published was $8.9 million.

15 The primary judge found that all of the initial advertisements and all of the revised advertisements (except for those which were published in a brochure) conveyed a representation to the relevant class of consumers that they could purchase unlimited ADSL2+ from TPG without being obliged to acquire any additional service and without the need to pay any additional charge. His Honour also found that all of the initial advertisements conveyed a representation that consumers could purchase unlimited ADSL2+ from TPG without any obligation to pay a set-up charge for that service.

16 Thus, his Honour found that all of those advertisements constituted conduct by TPG that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in breach of s 52 of the Act when published before 1 January 2011 and in breach of s 18 of Sch 2 Australian Consumer Law (ACL) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) when published after that date.

17 His Honour also found that all of those advertisements contained false representations with respect to the price of goods or services and false representations concerning the existence of a condition in breach of ss 53(e) and (g) of the Act and ss 29(1)(i) and (m) of the ACL.

18 In addition, his Honour found that the initial television, newspaper and internet advertisements did not specify in a prominent way, the single price for TPG’s ADSL2+ service of $509.89 in contravention of s 53C of the Act. The ACCC did not claim that the revised advertisements contravened s 53C.

19 The primary judge’s findings on the question of liability were made in his reasons for judgment delivered on 4 November 2011: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Limited [2011] FCA 1254. In a second set of reasons handed down on 15 June 2012, his Honour ordered a number of forms of relief including declarations, injunctions, corrective advertising and pecuniary penalties totalling $2 million, comprised of $600,000 for the initial advertisements and $1,400,000 for the revised advertisements.

20 TPG appeals, with one exception, against the orders made by the primary judge. The exception is that TPG does not appeal against that part of Order 2 made on 15 June 2012 which declares that TPG’s initial television advertisements contravened s 53C of the Act.

Issues in the appeal

21 Most of the issues in relation to the question of liability are not concerned with matters of principle. Rather, they raise issues of the proper application of established legal principles to the facts of the case.

22 The issues of liability that are raised on the appeal may be summarised as follows:

First, did the initial advertisements and the revised advertisements convey a representation to the ordinary or reasonable member of the relevant class of persons, that is to say consumers of broadband internet services, that TPG was offering to supply unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 without the need to bundle that service with the purchase of a home telephone line from TPG for an additional $30 per month.

Second, did the initial advertisements convey a representation to consumers of broadband internet services that TPG was offering to supply unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 per month without any obligation to pay an up-front set-up fee of $129.95.

Third, was the single price of $509.89 displayed in a prominent way, within the meaning of s 53C of the Act, in the initial print and internet advertisements.

23 The principal issues arising in that part of the appeal which addresses the relief ordered by the primary judge may be summarised as follows:

First, did the order of a pecuniary penalty of $2 million (as allocated between the contraventions in respect of the initial advertisements and the revised advertisements) disclose any error of principle in the primary judge’s exercise of discretion in accordance with the well-established principles stated in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 504-505.

Second, was the primary judge in error in finding that TPG’s conduct involved nine classes of contraventions of the Act or the ACTL (as applicable).

Third, was the primary judge correct in taking into account in his assessment of the quantum of the pecuniary penalty, the terms of, or the possible breach of, an undertaking given by TPG to the ACCC under s 87B of the Act in relation to an allegation made by the ACCC about an advertising campaign conducted by TPG for its mobile telephone services plan.

Fourth, is the primary judge’s finding that TPG’s conduct resulted in loss and damage to its competitor open to be set aside on appeal.

Fifth, was there any error of principle in the terms of the injunction ordered by the primary judge.

Sixth, was there any error of principle in the exercise of the primary judge’s discretion to order TPG to publish corrective advertising.

24 Needless to say, the issues which address questions of relief do not strictly arise for consideration if we are of the view that the primary judge’s findings of contraventions of the Act and the ACL, and his declarations with respect to those contraventions, are set aside.

Representative samples of the advertisements

25 It is clear that TPG published a very large number of advertisements in each of the forms of media used in the first and second phase of the campaign. This is particularly so in the second phase of the campaign which lasted for over a year. We were not, of course, taken to every advertisement but argument on the appeal proceeded upon the basis of samples of the advertisements to which we were taken by Mr O’Bryan SC who appeared for TPG.

26 Whilst emphasising the extent of the campaign and the fact that there were some differences from time to time in the form of the advertisements, Ms Strong SC, who appeared for the ACCC, conceded that the examples to which we were taken by Mr O’Bryan were fairly representative of the advertisements that were the subject of the primary judge’s findings.

27 We will therefore consider each of the initial and revised advertisements to which we were taken. It seems to us that the effect of the approach of counsel for the parties was that those advertisements covered the field of both phases of TPG’s advertising campaign. Accordingly, we will determine the appeal on the basis of the advertisements which we will describe below.

Initial television advertisement

28 The initial television advertisement was described by the primary judge at [44] – [46].

29 Annexure A to his Honour’s judgment contains a sample of the screen shots of the advertisement but, as his Honour observed, the advertisement must be watched in order to discern the impression that it conveys.

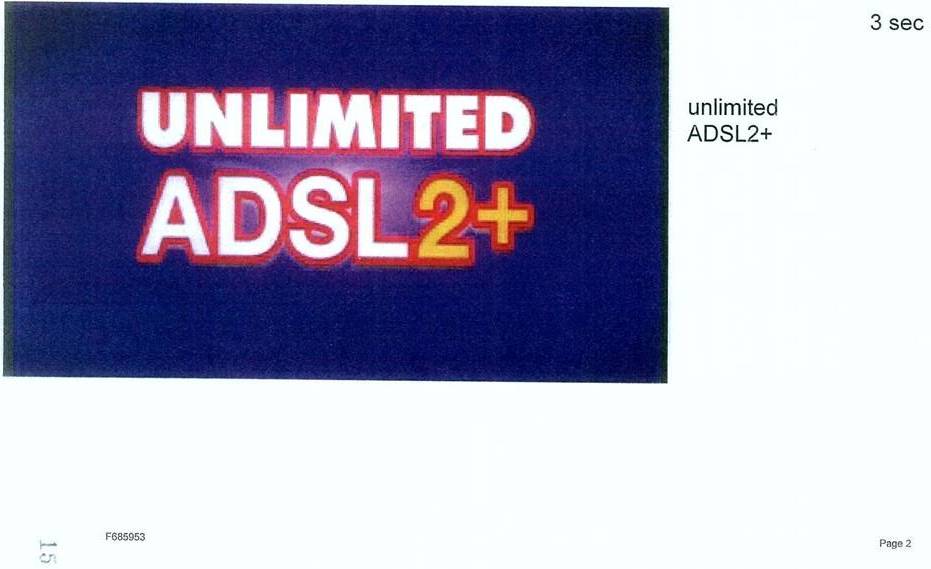

30 We were taken to a different example of the initial television advertisement which shows the screen shots and narrative. We will annex it as Annexure 1 to our judgment. The actual advertisement was also played for us in open court on a television screen and we viewed it again after the hearing in chambers.

31 The initial advertisement is 15 seconds in duration. As the primary judge observed, in the first ten seconds, the on-screen visuals are accompanied by a voiceover spoken by “an excited young female voice” stating that:

TPG gives you unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 a month. Yep, unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 a month.

32 The words spoken in the voiceover, and the precise time in the advertisement when the voiceover appears in conjunction with the visuals can be seen in the sample of the screen shots and narrative which are Annexure 1.

33 Annexure 1 to the original of our judgment is in colour so that the actual colours of the graphics, and their contrasts and background as described in the primary judgment at [45] can be seen in the annexure.

34 The primary judge said at [46] that the on-screen information, the size of the font and the effect of the voiceover take the viewer’s eye away from the information on the screen, other than the $29.99 message.

35 The primary judge said at [47] that the message of the voiceover, reiterated on screen, namely unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 a month is “plainly the dominant message.”

36 This finding by the primary judge, which reflects his approach to each of the initial and revised advertisements in each different form of media, raises the central issue in the appeal.

Revised television advertisements

37 His Honour stated that the revised television advertisement had the “same dominant message” as the initial advertisement. He said that the revised advertisement was similar to the initial advertisement, although with larger font or graphics for the information about the bundling condition. The similarity can be seen in Annexure B to the primary judgment which contains a sample of the revised advertisement.

38 We annex, as Annexure 2 to our judgment, the sample of the screen shots and narrative to which we were taken.

Initial radio advertisements

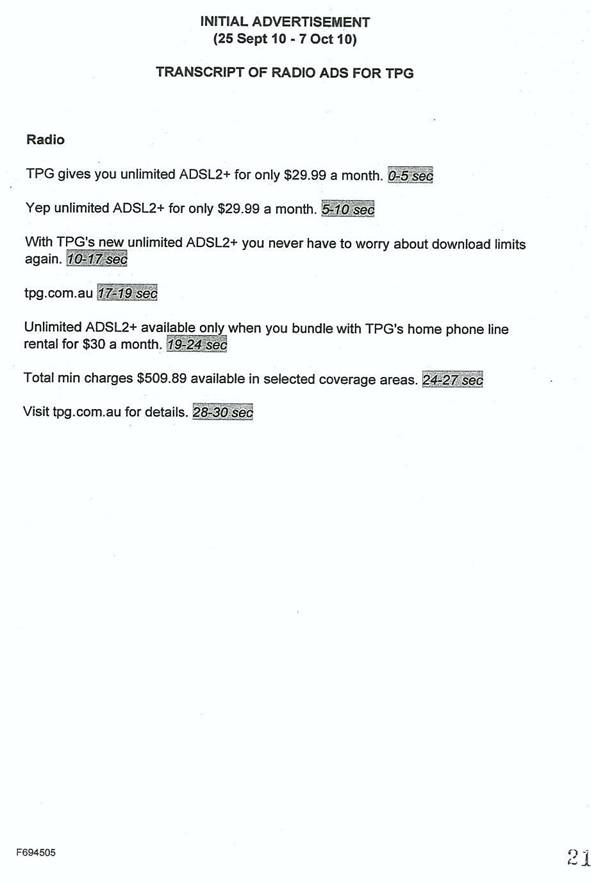

39 The primary judge described the initial radio advertisement at [49] – [50]. He observed that it has two distinct parts. The first part consists of the same words spoken by the same voice, and in the same tone, as those in the initial television advertisement set out at [31] above. The words and the tone emphasise TPG’s offer of unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 per month.

40 The second part of the radio announcement is spoken by a different person. That person has a male voice. The primary judge described it as a “rapid-fire” statement of the other terms of TPG’s offer. Those words state, in particular, the bundling condition and the total minimum charges that apply.

41 A transcript of the advertisement is Annexure C to the primary judgment. We were taken to a form of the transcript which records the time at which, and the period for which, the various words in the advertisements are spoken. The words “rapid fire section below” which appear in Annexure C to the primary judgment are not contained in the version of the transcript which was before us on the appeal.

42 We annex, as Annexure 3 to our judgment, the transcript which was addressed in argument before us. We listened to the advertisement several times in the course of the appeal.

The revised radio advertisement

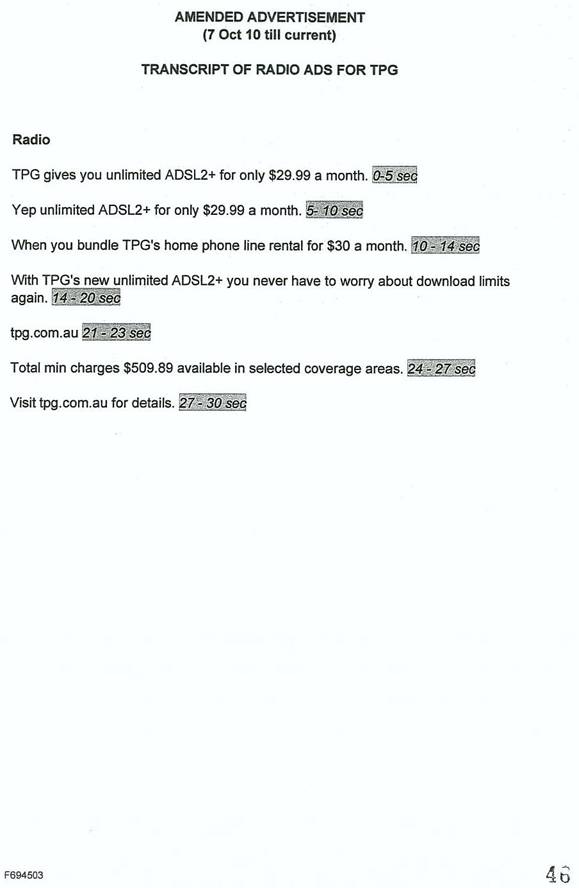

43 The revised radio advertisement consists of two parts spoken by the same female and male voices, and in the same separate tones and speeds, as in the initial advertisement.

44 However, in the revised form of the advertisement, the requirement that customers bundle the service with TPG’s home telephone line for $30 a month is spoken in the first part of the advertisement by the “excited” female voice. The second part of the advertisement states the total “min charges”.

45 The primary judge annexed, as Annexure D the revised transcript, including his interpolation of the words “rapid fire section”. We were taken to a form of the transcript which incorporates time references for the spoken words. We annex a copy as Annexure 4. We of course listened to the revised advertisement a number of times.

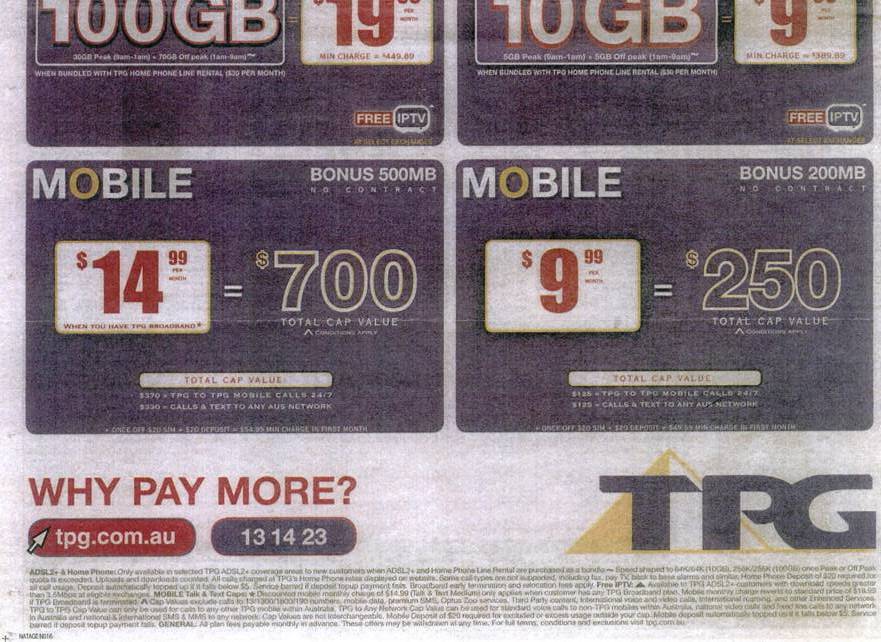

Initial print advertisement

46 The initial print advertisement appeared in a number of different formats. We were taken to two typical examples. One appeared in the Daily Telegraph on 30 September 2010. We were taken to a colour copy as well as a tear-sheet of the original.

47 We annex a colour copy of the Daily Telegraph advertisement which is Annexure 5 to our judgment. This annexure is very similar to the document which is Annexure E to the primary judgment.

48 The advertisement depicted in Annexure 5 forms only a small part of the page on which it appears. The full page contains two sports news items and a large photograph, as well as another photograph and other material. The advertisement occupies the lower 5cm of the page which is approximately 40cm long.

49 The colours employed in the advertisement in the Daily Telegraph (and in the other example of the initial print advertisement) are similar to those used in the television advertisements. The advertisement appears on a purple background with the text “unlimited ADSL2+” and “$29.99” in large white, yellow and red graphics. The graphics are outlined in contrasting red or white and stand out against the purple background.

50 The words which describe the bundling condition are in much smaller white font, immediately below the reference to “ADSL2+”. The description of the “min charge” is also in white font. It is in slightly smaller font than that which describes the bundling condition but both are perfectly legible against the purple background.

51 The description of various conditions to the service at the foot of the advertisement appears on plain newsprint. It is in black font and can be read quite easily by a person who takes the trouble to read it. The statements in this portion of the advertisement include a further description of the bundling condition.

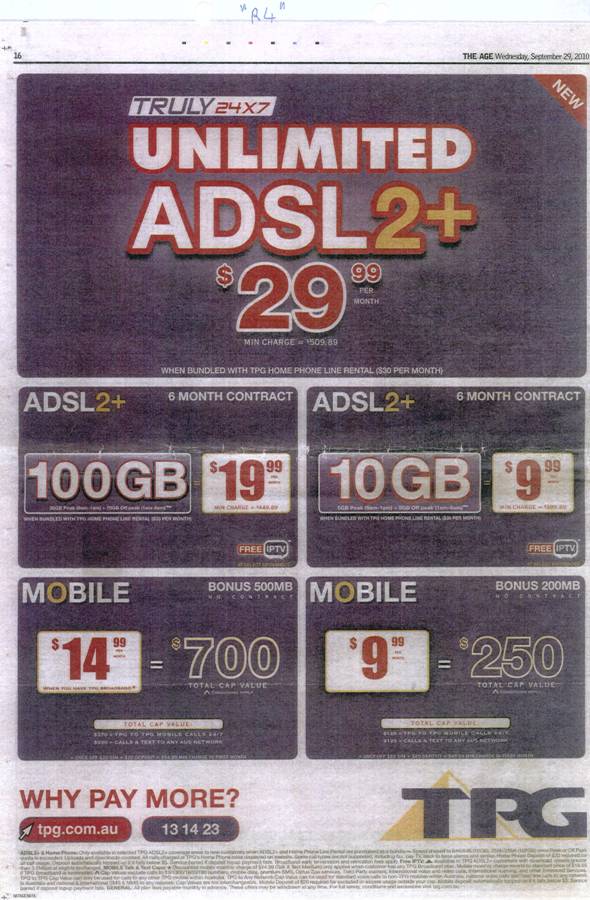

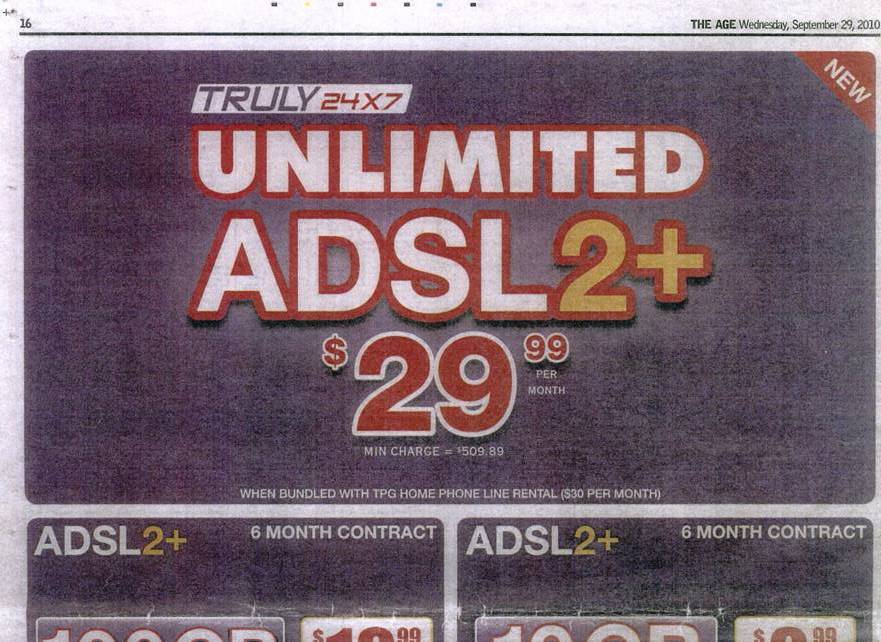

52 The other example of the initial print advertisement appeared in The Age on 29 September 2010. It is much larger than the Daily Telegraph advertisement and appears on a full page of an insert in The Age comprising the “Money” section of the newspaper.

53 The advertisement the subject of these proceedings appears at the top of the page. We annex a copy of the full page (reduced from A3 to A4) as Annexure 6 and annex a larger version (across two pages) as Annexure 6A.

54 The colour and form of this advertisement is very similar to that of the Daily Telegraph but it is approximately three times larger so that the graphics, including the bundling condition and the “min charge” are correspondingly larger than in the Daily Telegraph.

55 The balance of the page in The Age consists of other advertisements for TPG services consisting of limited ADSL2+ and mobile telephone. All are in the same, or similar colour composition to the advertisement at the top of the page for unlimited ADSL2+.

56 The description of the conditions at the foot of the page, which includes a description of the bundling condition, is in a similar font to that which appears in the Daily Telegraph.

The revised print advertisement

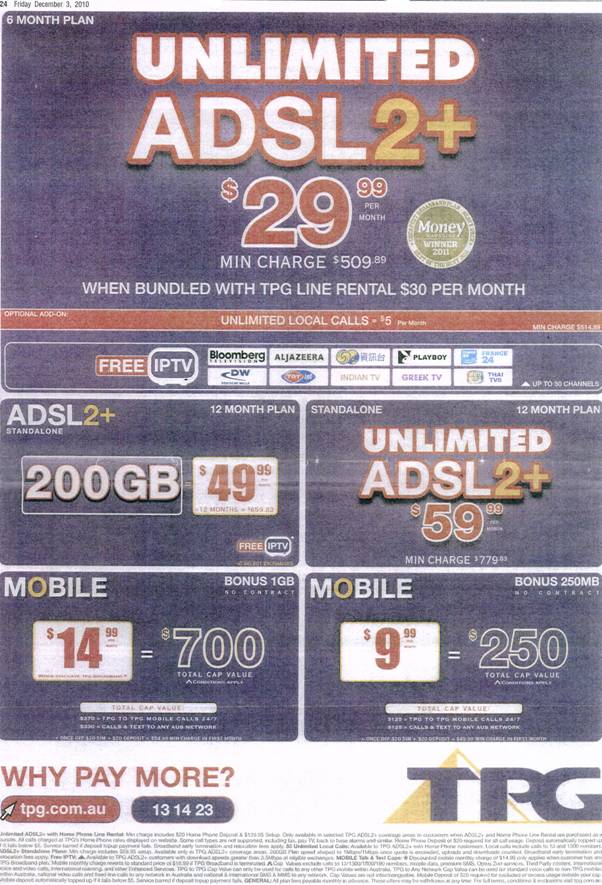

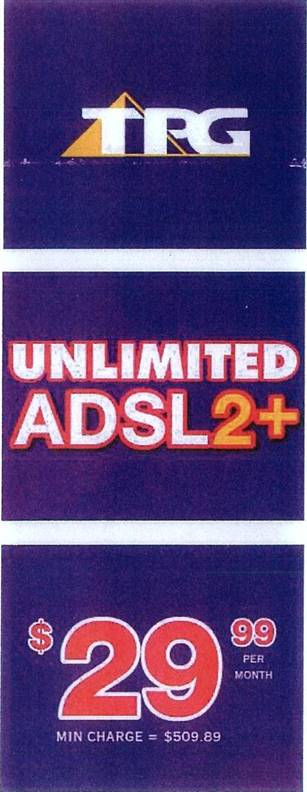

57 We were taken to two examples of the revised print advertisement. One appeared in The Age on 25 January 2011. It is similar in form to that which appeared in the initial advertisement in the Daily Telegraph but the coloured portion is twice the size of the initial advertisement. Notably, the bundling condition and the “min charge” appear in very much larger font than in the initial form of the advertisement.

58 We attach a copy of the revised print advertisement in The Age as Annexure 7. The primary judge annexed, as Annexure F, a different form of the revised advertisement. That annexure, although in a different format, shows the larger font size of the bundling condition and “min charge”.

59 The other example of the revised print advertisement to which we were taken was a full page advertisement which appeared in MX newspaper on 3 December 2010. It is similar in format to the initial advertisement which appeared in The Age but the bundling condition and minimum charge are set out in much larger font in the revised advertisement than that in which it appeared in the initial form of the advertisement.

60 We attach a copy of the revised advertisement appearing in MX newspaper as Annexure 8.

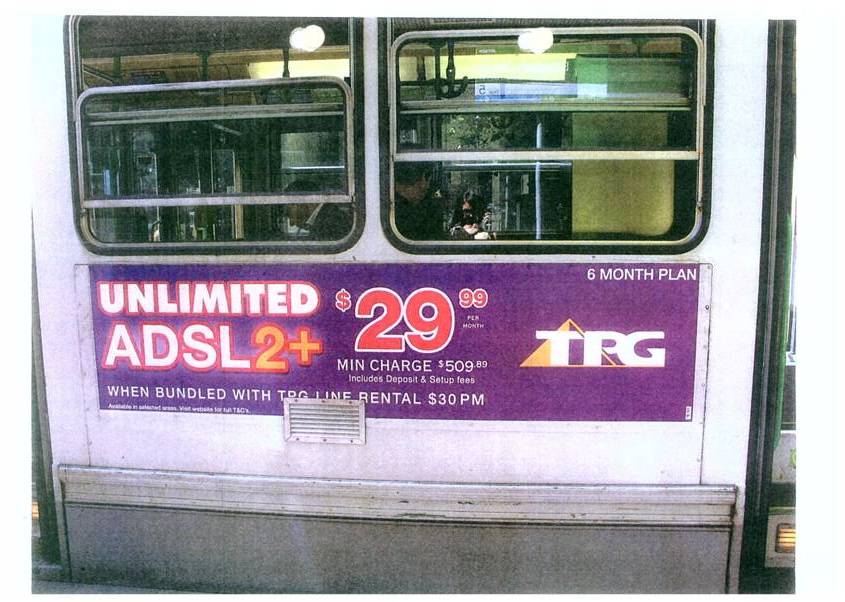

Initial public transport

61 The form of the initial public transport advertisement to which we were taken appeared on the side of a tram. The format, including colour scheme and layout of information is much the same as that which appeared in the television and print advertisements, although without the small print information at the foot of the print advertising.

62 We attach as Annexure 9 a copy of this advertisement. The bundling condition, although partly obscured by a vent, is in a white font. Although smaller in size and less colourful than the words which describe what the primary judge called the “dominant message”, they can be seen quite clearly in the advertisement.

63 So too, the words and figures “min charge $509.89” can be seen clearly below the bold red figures $29.99.

Revised public transport

64 The example of the revised public transport advertisement to which we were taken appeared on a bus during December 2010. We attach a copy as Annexure 10.

65 The form, colour and layout is similar to the television and print advertisements. The bundling condition is stated in large white font. So too is the statement of the minimum charge.

Initial online

66 We were taken to an example of the initial online advertisement which appeared on a website of a real estate agency information service. We attach as Annexure 11 a series of four pages comprising screenshots of the advertisement.

67 When a viewer accesses the computer screen, he or she sees the information which appears on the third and fourth pages of the annexure in the form of a banner. The banner remains on the screen throughout the advertisement. It is in similar colours and layout to the television and print advertisement. It contains the usual prominent statement which the primary judge called the dominant message about unlimited ADSL2+.

68 The bundling condition and statement of minimum charge appear in white font below the bold and colourful message about unlimited ADSL2+. This white font is quite small, although it can be seen at the bottom of the banner.

69 The other parts of the online advertisement revolve on the screen. The first page remains on screen for two to three seconds. That page contains the words “unlimited ADSL2+” and $29.99” in bold colours, similar to that of the other advertisements to which we have referred.

70 The words “min charge” and the figures $509.89 appear in smaller almost white colour against the purple background.

71 The second page of the advertisement remains on the screen for 9 seconds. It repeats the unlimited ADSL2+ message in large bold font. The statement of the minimum charge and the bundling condition are in almost white font.

Revised online

72 The example of the revised online advertisement to which we were taken is Annexure 12. It appeared on TPG’s website.

73 The revised advertisement is similar to the initial form of the advertisement. The second page of the advertisement is the static banner. The first page is much larger than the banner. It has the usual bold and colourful statement about unlimited ADSL2+. The bundling condition and the statement of minimum charge appear almost white in font that is much larger than the corresponding words on the banner, and much larger than in the initial form of the advertisement.

The legislation

74 The Act was substantially amended by the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 2) 2010 (Cth) (Amendment Act No 2). The short title of the Act is now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA): see s 1 of the CCA, which was amended by s 3 and Sch 5, item 2 of Amendment Act No 2. The consumer law provisions of the Act were, essentially, repealed and reproduced in Sch 2 to the CCA (known as the Australian Consumer Law, for which we have used the acronym ACL), which is applied as a law of the Commonwealth to the conduct of corporations under Part XI, Div 2, Subdiv A of the CCA.

75 By Sch 7, item 6(1) of the Amendment Act No 2, the Act as in force immediately before the commencement of that item (1 January 2011), continues to apply to acts and omissions before that date, and by item 7(1) the Act continues to apply to or in relation to this proceeding, because the proceeding was commenced before that date.

76 Section 76E was added to the Act by the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Act (No 1) 2010 (Cth) (Amendment Act No 1), by provisions commencing on 15 April 2010: s 2(1) and Sch 2, item 1 of Amendment Act No 1. Section 76E was repealed by Amendment Act No 2. However, in its form prior to 1 January 2011, it continues to apply to conduct after 15 April 2010 up to and including 31 December 2010: Sch 7, cll 6 and 7 of Amendment Act No 2. The equivalent pecuniary penalty provision is now contained in s 224 of the ACL.

77 The primary judge granted declaratory and injunctive relief, imposed a pecuniary penalty under s 76E of the Act (and s 224(1) of the ACL) of $2 million in total, and made corrective advertisement and adverse publicity orders under s 86C and s 86D of the Act (and s 246 and s 247 of the ACL).

The relevant legal principles on the issue of liability

78 The principles which govern the question of whether conduct is misleading or deceptive are now so well settled that they need hardly be repeated. The question is one of fact to be determined objectively upon the basis of the impugned conduct viewed as whole: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [25], [102]; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Limited v Puxu Pty Limited (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199.

79 As Gibbs CJ emphasised in Puxu at 199, it is wrong to select some words of the corporation, which if viewed alone, would be likely to mislead, if those words when viewed in their context, are not capable of misleading. Thus, as his Honour went on to say:

... where the conduct complained of consists of words it would not be right to select some words only and to ignore others which provided the context which gave meaning to the particular words.

80 That principle has been stated and applied in a stream of appellate and first instance authorities which have considered whether an advertisement offends the requirements of s 52 of the Act.

81 It is not necessary to refer to all of those authorities. It is sufficient to refer to the observations of Sheppard J in the seminal authority of Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 FCR 1. His Honour said, at 4, that it is not appropriate to take part of an advertisement and endeavour to ascertain in isolation the meaning of each of the critical words or phrases. He continued by saying:

Rather, an attempt should be made to measure the veracity of its message by reading it in context.

82 In making those observations Sheppard J recognised that one needs to take into account the fact that many readers or viewers of an advertisement would not make a close study of it but would read the advertisement fleetingly and observe its general thrust.

83 A number of authorities have dealt with the question of whether an advertisement that contains a potentially misleading “primary statement” which is corrected or qualified elsewhere in the advertisement is nevertheless misleading. The principle which has been said to apply to those cases is that the qualifying material must be sufficiently prominent or conspicuous to prevent the primary statement from being misleading: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities & Investments Commission (2004) 49 ACSR 369 at [51]; Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 205 ALR 402 at [37].

84 That principle seems to us to be no more than an application of the overarching rule that it is necessary to look at the whole of the advertisement in its full context.

85 Where, as in the present case, the advertisements were directed at members of a class in a general sense, the enquiry is concerned with the impact of each advertisement on the hypothetical reasonable member of the class of persons to whom the advertisement was directed: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [103]; Campbell v Backoffice at [26].

86 The questions which arise under ss 53(e) and (g) of the Act and ss 29(1)(i) and (m) of the ACL do not raise any legal principles other than those to which we have referred above. This is because those sections are concerned with misleading representations as to the price of services and the existence of any condition. The answer, in relation to each advertisement, turns upon whether we are of the view that the primary judge was in error in finding that the advertisements were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

87 The only issue of legal principle which arose at the trial in relation to the construction of s 53C was as to the meaning of the requirement in s 53C(1)(c) that the corporation is to specify “in a prominent way” the single price for the services.

88 The parties to the appeal accept the construction given to the word “prominent” by the primary judge at [126]. His Honour there said that “prominent” in s 53C of the Act means that the single price is required to stand out so as to “strike the attention”, “be conspicuous”, “be easily seen” or “be very noticeable”. He accepted that there was no requirement that the single price be as conspicuous as the specification of the $29.99 monthly charge which constituted a representation as to part of the consideration for the supply of the relevant services.

89 We will proceed to consider the appeal on the basis of the principles stated above.

90 The primary judge’s findings do not turn on disputed conversations or questions of credit. We are in as good a position as his Honour to determine the proper factual findings to be made in relation to each of the advertisements.

91 We must of course give respect and weight to his Honour’s factual findings but if we reach the conclusion that he was wrong, we are required, in the exercise of the appellate jurisdiction, to give effect to that conclusion: see Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [25]; Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [24] – [27].

General observations

92 The parties to the appeal did not dispute the primary judge’s statement of the legal principles.

93 Nor was there any real dispute that his Honour correctly identified the target audience. He accepted that the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class to whom the advertisements were directed was a person who knew at least enough about broadband internet services to know that ADSL2+ was a faster and more desirable service than others such as ADSL1 or dial-up: see his Honour’s observations at [27] – [28].

94 His Honour went on, at [28] – [29] to qualify these remarks by stating that the target audience would include persons who do not have a high level of knowledge about broadband internet and that the audience would include persons who were first-time users of internet services.

95 Senior counsel for TPG sought to challenge this finding. He submitted that the first-time users of internet services would be persons such as the very elderly, or persons living in remote areas who have had no exposure to the internet in their lives. By contrast, he submitted the target audience would be persons who were “savvy” about what is involved in internet plans.

96 Ultimately, we do not think that anything turns on this debate. Of course, it is necessary to identify the class and to consider the matter by reference to all who come within it, including “the astute and the gullible” and “men and women of various ages”: see Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202. Here, the class includes not only the experienced and technology savvy users, both young and old, but also those persons colourfully described by Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Limited [2010] FCA 1177 at [28] as the “vulgarians”.

97 As Perram J said in that case, the point has surely been reached where consumers must be taken to have a certain degree of background knowledge of internet usage and to know that broadband plans ordinarily have usage limits. But the “vulgarians” will be drawn to unlimited plans, simply to have the largest plan that is available.

98 What is particularly important in the present case is that consumers to whom the advertisements were directed must also be taken to have some familiarity with the market for the provision of broadband services. In particular, they would know that services such as ADSL2+ are offered for sale as either “bundled” or “stand alone”. That was the view which was adopted by Ryan J in an application for interlocutory relief in the present matter: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Limited [2010] FCA 1478 at [16].

99 The evidence to which the primary judge referred at [33], that a percentage of the target audience is likely to have a lower level of interest in broadband internet bundled with a home telephone line, was not in dispute. It was supported by the agreed facts that the percentage of consumers with a fixed home telephone line has been falling since 2005, particularly amongst 18-24 year olds living away from home.

100 But it does not provide an answer to the critical question which is whether, having regard to the principles referred to above, the ordinary or reasonable consumer would be led into error by the advertisements, read or viewed as a whole, in their full context. This carries with it the question of whether a “significant proportion” of the class would be misled: National Exchange at [21] – [23], [70].

The critical question

101 The primary judge answered the critical question by finding that the dominant message in each of the relevant advertisements was that the reader or viewer could acquire ADSL2+ for $29.99 per month without incurring an obligation to acquire any additional service or to pay any further charges.

102 On that approach, the ordinary or reasonable reader would be misled unless the misleading dominant message was corrected by a sufficiently clear and prominent statement which prevented the inaccurate dominant message from being misleading, or likely to mislead or deceive.

103 In our respectful view, that was not the correct approach to adopt when considering the advertisements. It is true, as Sheppard J said in Tobacco Institute, that many persons will only absorb the general thrust. But this is not a mandate for ignoring the rule that the whole of the advertisement must be considered in its full context.

104 It seems to us that the primary judge’s emphasis on the “dominant message” led him into error. The authorities which have considered advertisements containing a misleading “primary” or “dominant” statement do not depart from the overarching rule that it is necessary to look at the whole of the advertisement. Also, in those cases, the primary statement was flagrantly misleading when read in light of the inconspicuous fine print.

105 Moreover, to approach the question as one based solely upon the “dominant message” does not take into account the need to have regard to the attributes of the hypothetical reader or viewer. As we have said, these attributes include knowledge of the “bundling” method of sale commonly employed with this type of service, as well as knowledge that setup charges are often applied.

106 This is the prism through which the critical question of the overall impact of the commercials on the ordinary and reasonable consumer must be considered. It produces a different answer to that reached by the primary judge in almost all of the advertisements because the consumer must be taken to have read or viewed the advertisements with knowledge of the commercial practices of bundling and setup charges.

Was the initial television advertisement misleading?

107 The context of this advertisement is a short television clip with heavy emphasis on the offer of unlimited ADSL2+ and the price of $29.99. This is done by projecting the product and its price in colours which feature them very noticeably against the purple background. That part of the message is also emphasised by the voiceover which, when combined with colourful graphics, has the effect of focussing the viewer’s attention on the product, namely unlimited ADSL2+ and the price of $29.99 per month.

108 The evanescent nature of a television advertisement makes more pertinent the observation of Sheppard J in Tobacco Institute that many viewers would look at it fleetingly and absorb its general thrust rather than to take in the other information which can be seen in the advertisement.

109 As the primary judge said, the size of the graphics or font in which the bundling condition and minimum charges are stated and the overall thrust of the advertisement detracts attention from them.

110 But a degree of robustness is required. The legislation does not operate for the benefit of those who fail to take care of their own interests: Puxu at 199; Nike at [102].

111 Once the attributes of the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable viewer are taken into account, we doubt that such a person would be misled. As we have said, that person is taken to know that the service may be offered as bundled with another and that some form of connection is required to receive the service. He or she is also taken to know that setup charges are often made.

112 Nevertheless, we accept that the matter may be one of fact and degree, so that in considering the fleeting nature of the advertisement, and giving appropriate respect and weight to the primary judge’s finding of fact, we are not convinced he was wrong in coming to the view that the advertisement was misleading.

The revised televised advertisement was not misleading

113 In our view, the revised advertisement was not misleading. The larger font or graphics in which the bundling condition and the minimum charge are depicted could not be missed except by a perfunctory viewing.

114 In any event, the fact that the ordinary or reasonable viewer knows that services may be offered as a “bundle” and that setup charges are often made, provides a complete answer to the contention that the advertisement is misleading.

The initial radio advertisement was not misleading

115 The “rapid-fire” section of the advertisement can be heard quite clearly. Its content could not be ignored except by a listener who failed to pay any attention to it.

116 Moreover, the attributes of the ordinary or reasonable listener, to which we have referred, provide a complete answer to the suggestion that the advertisement is misleading.

The revised radio advertisement was not misleading

117 The bundling condition is stated in the first part of the advertisement. If anything, the initial form of the advertisement was perhaps clearer to a listener because the second part of the advertisement drew attention to the conditions upon which unlimited ADSL2+ was available for $29.99 per month.

118 Nevertheless, as we have said, the attributes of the ordinary or reasonable viewer provide a complete answer.

The initial print and revised advertisements were not misleading

119 The short answer, in both instances, is that the ordinary or reasonable viewer with the attributes we have described would not be misled.

120 Whilst the emphasis of the advertisements, both through the use of colours and size of font and graphics is upon unlimited ADSL2+ at $29.99 per month, the bundling condition and the minimum charge are able to be seen. They are quite plain in the revised advertisement.

The initial and revised public transport advertisements were not misleading

121 Advertisements displayed through this medium are more evanescent than in newspapers or print media but usually less so than television.

122 The bundling condition and minimum charge can be seen clearly in both the initial and revised advertisements. They were not misleading for the reasons given in relation to the print advertisements.

The initial and revised online advertisements were not misleading

123 Online viewers tend to browse on that medium and therefore to look at advertisements more quickly than in print media.

124 The bundling condition and the minimum charges are much clearer in the revised advertisement than in the initial ones where the font or graphics showing that condition were quite small. Nevertheless, for the reasons stated above, we consider that the advertisements were not misleading.

Section 53C of the Act

125 TPG appeals against the primary judge’s finding that the initial print and initial online advertisements contravened s 53C. TPG does not appeal against the adverse finding made in relation to the initial television advertisements. No question of breach arises in respect of any of the revised advertisements.

126 Mr O’Bryan submitted that the primary judge erred in his approach to the application of s 53C(1)(c) of the Act to the advertisements by adopting what amounted to a comparative test. He drew attention to the primary judge’s statements in [134] and [135] that the main part of the message, namely unlimited ADSL2+ for $29.99 per month, dominates the advertisement.

127 The effect of his submission was that the primary judge had erroneously adopted the test stated in s 53C(4) which was excluded in the present case by s 53C(5) because the services were to be supplied under a contract for periodic payments.

128 We do not consider that his Honour applied the test stated in s 53C(4). He correctly construed the word “prominent” in s 53C(1)(c) as being “conspicuous” or the other expressions synonymous with that word. Moreover, he specifically stated at the end of [126] that there was no requirement that the single price be as conspicuous as the specification of the $29.99 monthly charge.

129 However, the essential question which arises is whether the purposive construction adopted by his Honour at [130] correctly reflects the language of s 53C(1)(c) which requires only that the single price be specified in a prominent way.

130 For convenience, we will set out his Honour’s remarks at [130] in full:

It follows that the purpose of this section is that sufficient prominence be given to the single price such that an impression is not created that the service is being offered for sale at a lower price than it is. Accordingly, where a prominent component price is specified, such as the $29.99 per month in this matter, the minimum charge is also required to stand out, be conspicuous, be easily seen or very noticeable. It is not though required to be as prominent as the monthly charge.

131 In our opinion, the first sentence of that paragraph puts an impermissible gloss on the subsection. But the second and third sentences are, in our view correct. All that his Honour sought to emphasise is that the question of whether the single price is prominent or conspicuous depends upon the overall context.

132 That seems to us to be borne out by his Honour’s findings at [137]. He said in that paragraph that the specification of the minimum charge did not stand out so as to be conspicuous or strike the attention and was not easily seen or very noticeable. He concluded by saying: “[f]ar from being prominent, each specification is better described as unobtrusive.”

133 We can see no appellable error in this conclusion.

Relief

134 An appellate review of the imposition of a penalty, being a discretionary decision, requires the finding of error in the manner set out in House v The King at 504-505 per Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ. The penalty is not to be disturbed only on the basis that the appeal Court may have come to a different conclusion.

135 The ACCC contends that the total penalty imposed is appropriate, and to the extent that there is a “range”, having regard to the remarks of the Full Court in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249 (Singtel), it is approximately comparable with the penalty imposed in that decision which was based on similar conduct.

136 Even assuming liability in respect of all the advertisements, as the primary judge found, we consider the overall penalty imposed to be outside the appropriate range of penalties for the established contraventions. Whilst it is strictly unnecessary for us to consider all of his Honour’s orders on the question of relief, we will do so briefly because our views on those questions will inform a determination of the relief which is appropriate for the limited number of contraventions which we have upheld.

Penalty – relevant matters

137 Section 76E(2) of the Act provided and s 224(2) of the ACL provides:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under Part VC/Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

138 The “relevant matters” referred to in s 76E(1) of the Act and s 224(1) of the ACL incorporate the same non-exhaustive mandatory considerations that are expressly provided for determining a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 76(1) of the CCA.

139 The established principles to be applied by the Court in determining penalties under s 76(1) of the CCA are broadly applicable in determining a penalty under s 76E of the Act and s 224(1) of the ACL.

140 French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited (1991) 13 ATPR 41-076 at 52,152-52,153 identified the following matters:

1. the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

2. the amount of loss or damage caused;

3. the circumstances in which the conduct took place;

4. the size of the contravening company;

5. the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market;

6. the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

7. whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

8. whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

9. whether the company has shown disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

141 Those considerations have since been approved with the following extensions by Full Courts of this Court: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 290, 292-294 and 297 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ and J McPhee & Son (Australia) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2000) 172 ALR 532 at [158] and [163]:

(a) similar conduct in the past;

(b) effect on the functioning of the market and other economic effects of the conduct;

(c) the financial position of the contravening company; and

(d) whether the conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

142 In determining the appropriate penalty, it is also relevant to take into account the “totality principle”; the total penalty for related contraventions ought not to exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved: Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Limited (1995) 17 ATPR 41-375 at 40,169 per Burchett J. This approach was adopted by Mansfield J in ACCC v Rural Press Ltd (2001) 23 ATPR 41-833 at [19] and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 929 at [22].

143 A penalty must not be so high as to be oppressive: NW Frozen Foods at 293, referring to Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chain Saws (Aust) Pty Ltd (1978) 2 ATPR 40-091 at 17,896. In considering what may constitute oppression, Merkel J stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) (2005) 215 ALR 281 at [9] that:

… a penalty that is no greater than is necessary to achieve the object of general deterrence, will not be oppressive.

144 There is also the parity principle to be considered. Similar contraventions should incur similar penalties, other things being equal, albeit that “other things are rarely equal where contraventions of the Trade Practices Act [or CCA] are concerned”: NW Frozen Foods at 295.

Assessment of Penalty

145 The process to be applied in arriving at a particular penalty figure was considered in the context of criminal sentencing by the High Court in Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357. That process is also applicable to the assessment of pecuniary penalties under s 76 of the Act: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd (2005) 27 ATPR 42-070 at [68].

146 In Markarian, Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ held:

(a) the Court's assessment of the appropriate penalty is a discretionary judgment based on all relevant factors (at [27]);

(b) "… careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick." (at [31]);

(c) it will rarely be appropriate for a Court to start with the maximum penalty and proceed by making a proportional deduction from that maximum (at [31]);

(d) the Court should not adopt a mathematical approach of increments or decrements from a pre-determined range, or assign specific numerical or proportionate value to the various relevant factors (at [37] citing Wong v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [74]-[76] per Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ);

(e) it is not appropriate to determine an "objective" sentence and then adjust it by some mathematical value given to one or more factors such as a plea of guilty or assistance to authorities (at [37]);

(f) the Court "may not add and subtract item by item from some apparently subliminally derived figure" to determine the penalty to be imposed (at [39]); and

(g) since the law strongly favours transparency, accessible reasoning is necessary in the interests of all, and, while there may be occasions where some indulgence in an arithmetical process will better serve the end, it does not apply where there are numerous and complex considerations that must be weighed (at [39]).

Number of Contraventions

147 It is trite that each advertisement constitutes a separate infringement of the Act, and is punishable by a fine of up to $1.1 million. Nor is it in dispute that in the context of a wide ranging advertising campaign, the appropriate approach is to determine the number of categories of infringing conduct. The primary judge adopted the ACCC’s submission that there were nine classes of contraventions based upon the four different types of initial advertisements and the five different types of revised advertisements, and having regard to the differences between the advertisements in terms of degree of disproportion between the “dominant” and “qualifying” messages, the duration of the advertisements, the reach of the advertisements and the different media in which the advertisements appeared.

148 TPG contends that there are three different messages that are said to contravene the Act or CCA – (i) the “no bundling condition”, (ii) the no set-up fee in the initial advertisements, and (iii) the failure to prominently display the single price in the initial advertisements. We will refer to these as categories of contraventions.

149 The ACCC contends that the approach taken by the primary judge was consistent with that followed by the Federal Court in Singtel. We do not accept this. As was made clear in Singtel, although the Optus campaign was informed by a single strategy it was implemented in different ways. It was not the case there that the same conduct gave rise to all the contraventions or to all of the 11 categories of contravention identified. Rather, different conduct was involved in each category of contraventions. Optus also engaged in different acts of contravention within each medium. For example, as the Full Court observed, each of the three television advertisements promoted a different product and did so with different advertising content. The content of each message was different.

150 The present case is distinguishable. The content of the advertisements across the range of media was broadly the same and the vice complained of and found to be established by the primary judge was essentially the same in each case.

151 We think it arguable, assuming the correctness of the findings of the primary judge, that there are actually only two categories of contravention; first that ADSL2+ can be purchased for $29.99 per month without more and second, the failure to display the single price in the initial advertisement prominently. Nonetheless, we shall accept the categorisation contended for by TPG.

152 Whilst there were, in a sense, two advertising campaigns, one for only 12 days, the other for approximately 13 months, there was really only one campaign when the nature of the impugned conducted is considered.

153 Pursuant to s 76E of the Act and s 224 of the ACL, the Court may impose a pecuniary penalty in respect of a contravention of s 53 of the Act (for conduct up to 31 December 2010) and s 29 of the ACL (for conduct from 1 January 2011).

154 By s 76E(3) of the Act (and s 224(3) of the ACL), the maximum penalty for a body corporate for each contravention of the above provisions is $1.1 million.

155 Accordingly, whilst the total maximum penalty for nine contraventions was $9.9 million, the appropriate maximum penalty may be viewed as $3.3 million in the context of the conclusion which we have come as to their being three categories of contraventions.

The s 87B undertaking

156 In 2009 the TPG provided the ACCC with a s 87B undertaking. The undertaking stated that the ACCC had alleged that there had been a breach of the Act. The undertaking acknowledged that there “may have” been a contravention of the Act. TPG undertook to do a number of things, including to not engage in misleading or deceptive conduct generally. TPG had never been found to have engaged in the conduct that was alleged in the undertaking and it did not admit that it had engaged in that conduct. Further, it was never alleged at trial that it had breached that undertaking or that such a breach would be relevant to the imposition of the penalty.

157 The primary judge determined that the undertaking was of relevance to the pecuniary penalty and to the injunction. The primary judge not only took the undertaking into account on the questions of the injunction and the pecuniary penalty but also found that the undertaking had been breached, noting that TPG had not submitted to the contrary. Nothing turns on this last point as the question whether the undertaking had been breached was not an issue at the trial.

158 The undertaking ought not have been taken into account. Section 87B of the Act sets out the process to be invoked in the event that a breach of undertaking is alleged. That statutory process was not invoked in this case.

159 The circumstances in which an act or omission takes place for the purpose of s 76E(2)(b) of the Act can only be circumstances that are relevant for the determination of what pecuniary penalty ought be imposed. The existence of the undertaking, where the facts underlying the undertaking were never proved and no breach was ever alleged, was not a relevant circumstance.

Third party loss and damage

160 Loss and damage to a third party is a mandatory consideration on the question of penalty: see s 76E of the Act. The onus of proof lies with the ACCC: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761 at [27]-[28]. TPG contends that there was no evidence of any loss or damage and the primary judge’s findings that loss was likely to have been suffered by TPG’s competitors was based entirely upon speculation and not on evidence.

161 In respect to the few customer complaints that exist, TPG contends that the primary judge’s finding that they were related to the allegedly infringing conduct, was not open on the evidence before him. The customers who raised the issue were largely confused, it seems, by what they may have been told by salespeople.

162 The primary judge’s main findings on loss and damage related to the loss and damage that, the primary judge found, TPG’s industry competitors may have suffered. However, there was no direct evidence and no evidence sufficient to ground an inference that a material number of customers were signed by TPG as a result of the misleading characteristics of the advertisements, rather than simply because of the advertisements themselves. Not everyone who saw or heard the advertisements would have been misled by them. Further, the evidence demonstrated that the charging structure was explained to customers in some detail before they signed up and any misunderstanding is likely to have been clarified at that stage. Moreover, the evidence established that the ADSL2+ product being offered by TPG was cheaper than any commensurate product being offered on the market. In circumstances where the vast majority of customers already had a phone line and were paying about $30 per month for it, there is no basis to conclude that a significant number of customers who signed with TPG would have done anything different if the advertisements were not misleading. The handful of customer complaints in evidence were not directed to the conduct of which the ACCC complained. There were no complaints by competitors.

Pecuniary Penalty

163 There is no explanation in the penalty judgment as to how the various components of the penalty of $2 million were arrived at. In any event, in total, they are outside the appropriate range both in terms of the components and the total penalty sum. As we have mentioned, each of the contraventions more or less contain the same vice(s) alleged by the ACCC. It would be artificial in these circumstances to allocate different penalties for each contravention within each category. Indeed we think that the three categories of contraventions can each be viewed as having the same quality of contravention inviting equal penalties. We regard them as at the lower end of the range of serious conduct. Whilst contraventions were found to have occurred, it is of significance that TPG made changes to the content of the initial advertising campaign to meet the concerns of the ACCC. Nonetheless, those attempts were held to have failed. However, this was not a case of a corporation acting deliberately or covertly in contravention of legislative requirements. Against a total maximum penalty of $1.1 million for each category, we consider an appropriate penalty to be $250,000 for each, a total of $750,000. We consider, having regard to the principle of totality that an overall penalty of $500,000 would have been appropriate.

Injunctions

164 The primary judge ordered that, for a period of three years, TPG “prominently” disclose the total monthly prices of any bundled internet services and “prominently” disclose the bundling condition.

165 TPG challenges orders 4 and 5 which use the term “prominently”.

166 The orders impose an obligation on TPG which the law does not impose. The requirements of ss 52 and 53 of the Act, on one hand, and s 53C on the other, are different and ought not be confused. The orders should not have been made.

Corrective advertising

167 TPG’s challenge to the orders of the primary judge that it undertake corrective advertising in various newspapers as well as on all websites it controlled is not contested to the extent that those orders are yet to be complied with. Corrective notices, in a slightly modified form (by agreement between the parties) to those ordered by the primary judge, were posted on a hyperlink to TPG’s website at www.tpg.com.au and were also sent by TPG to all its existing customers. This was done in accordance with orders made by Marshall J on 12 July 2012 which also operated to stay the orders of the primary judge that TPG publish corrective advertising in six daily newspapers on two separate days.

168 The ACCC, in these circumstances, does not press for the outstanding publication orders of the primary judge to be maintained. We do not think it necessary to consider TPG’s submissions in support of this ground of appeal. It is sufficient that we conclude that the ACCC’s position is an implicit acknowledgment, correctly so, that the fact of past publication and the passage of time since the relevant conduct means there is little or no utility in maintaining the orders of the primary judge the subject of the stay orders by Marshall J. Those orders of the primary judge will be set aside.

Penalty

169 The only contraventions which remain, following the disposition of the appeal, are breach of ss 52, 53(e) and 53(g) of the Act in relation to the initial television advertisement and s 53C of the Act in relation to the initial television, print and online advertisements. The question remains as to what, if any, penalty ought be imposed and what, if any, consequential orders should be made. The parties should be given the opportunity first to confer about these issues.

170 Accordingly, we direct that the parties confer in relation to what penalties and consequential orders, if any, ought be imposed in light of these reasons and if able to reach agreement, to then bring in a minute of proposed relief within a date to be fixed by the Court.

Orders

171 There will be orders that the appeal be allowed in part and that the parties bring in a minute of proposed relief within a date to be fixed by the Court. Thereafter the Court will determine the relief to be granted. In the event that the parties cannot agree the terms of such a minute, there will be liberty to apply to relist the appeal for the parties to make submissions on the question of penalty and consequential relief, if any.

| I certify that the preceding one hundred and seventy-one (171) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justices Jacobson, Bennett, and Gilmour JJ. |

Associate:

Annexure 1

Annexure 2

Annexure 3

Annexure 4

Annexure 5

Annexure 6

Annexure 6A

Annexure 7

Annexure 8

Annexure 9

Annexure 10

Annexure 11

Annexure 12