FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Cheedy on behalf of the Yindjibarndi People v State of Western Australia [2011] FCAFC 100

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| NED CHEEDY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE YINDJIBARNDI PEOPLE Appellant | |

| AND: | First Respondent FMG PILBARA PTY LTD ACN 106 943 828 Second Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

AND DIRECTS THAT:

2. The appellants file and serve any submissions on the question of costs by 26 August 2011.

3. The respondents file and serve written submissions in response on the question of costs by 2 September 2011.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | WAD 193 of 2010 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | NED CHEEDY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE YINDJIBARNDI PEOPLE Appellant |

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent FMG PILBARA PTY LTD ACN 106 943 828 Second Respondent WINTAWARI GURUMA ABORIGINAL CORPORATION (WC97/89) Third Respondent |

| JUDGES: | NORTH, MANSFIELD AND GILMOUR JJ |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 12 AUGUST 2011 |

| WHERE MADE: | PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1 The appeal is dismissed.

AND DIRECTS THAT:

2. The appellants file and serve any submissions on the question of costs by 26 August 2011.

3. The respondents file and serve written submissions in response on the question of costs by 2 September 2011.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | WAD 192 of 2010 WAD 193 of 2010 |

| ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| BETWEEN: | NED CHEEDY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE YINDJIBARNDI PEOPLE Appellant |

| AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent FMG PILBARA PTY LTD ACN 106 943 828 Second Respondent

WINTAWARI GURUMA ABORIGINAL CORPORATION (WC97/89) Third Respondent |

| JUDGES: | NORTH, MANSFIELD AND GILMOUR JJ |

| DATE: | 12 AUGUST 2011 |

| PLACE: | PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 These appeals concern future act determinations made under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Act). The appellants are the registered native title claimants of land in the Pilbara in Western Australia. The National Native Title Tribunal (the Tribunal) determined under s 38(1) of the Act that the first respondent, the State of Western Australia (the State) may grant certain mining leases to the second respondent, FMG Pilbara Pty Ltd (FMG).

2 On appeals to this Court, McKerracher J dismissed the appeals and upheld the determinations. The issues raised on these appeals from the orders made by McKerracher J are whether he erred in failing to hold:

(a) that s 38 and s 39 of the Act which govern the making of determinations of the Tribunal are beyond the power of the Commonwealth because they are laws for prohibiting the free exercise of the appellants’ religion contrary to s 116 of the Constitution;

(b) the Tribunal erred by failing to construe s 38 and s 39 of the Act in accordance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and

(c) the Tribunal made certain jurisdictional errors in making the determinations.

THE FUTURE ACTs provisions

3 One aim of the Act is to address the tension arising following its enactment between rights and interests then asserted by aboriginal people and the claims of others to undertake acts on the land which are inconsistent with those rights and interests. This aim is expressed in the Preamble to the Act as follows:

It is particularly important to ensure that native title holders are now able to enjoy fully their rights and interests. Their rights and interests under the common law of Australia need to be significantly supplemented. In future, acts that affect native title should only be able to be validly done if, typically, they can also be done to freehold land and if, whenever appropriate, every reasonable effort has been made to secure the agreement of the native title holders through a special right to negotiate. It is also important that the broader Australian community be provided with certainty that such acts may be validly done.

4 The proposed grant of mining leases in the present case are future acts because they are to be granted after 1 January 1994, and they would be partly or wholly inconsistent with the native title rights and interests asserted by the appellants (s 233(1)(a)(ii) and (c)(ii)(C), and s 227). The grants would be invalid unless validated by a provision in the Act (s 24AA).

5 The Act provides for two ways relevant to these appeals by which a future act will be valid. First, the Act provides for a special right to negotiate process. The State must serve a notice of intention to do the future act (s 29). Then, the Act provides that the future act will be valid if an agreement is reached between the parties after negotiation in good faith (s 28(1)(a)).

6 The second and alternative way that a future act will be valid is, where no agreement is reached, the issue is determined by an arbitral body. If six months have passed since the notification day and no agreement has been reached, a negotiating party may apply to an arbitral body for a determination under s 38 of the Act (s 35). Where the future act is done by a State and no arbitral body has been established under State law, the Tribunal is the arbitral body (s 27(2)(b)). In the present case the Tribunal is the arbitral body. The Tribunal must then determine that the future act either must not be done, may be done, or may be done subject to conditions (s 38(1)).

THE FACTS

7 On 8 August 2003, the Tribunal registered an application for determination of native title made by the appellants in respect of 2788 square kilometres in the Pilbara in an area between Paraburdoo and Marble Bar in Western Australia. The registered native title rights and interests included the right to possess, occupy, use and enjoy the area as against the world, the right to control access of others to the area, and the right to take, use and enjoy the resources of the area, other than minerals and petroleum, for various purposes including for cultural, religious, spiritual, ceremonial and/or ritual purposes.

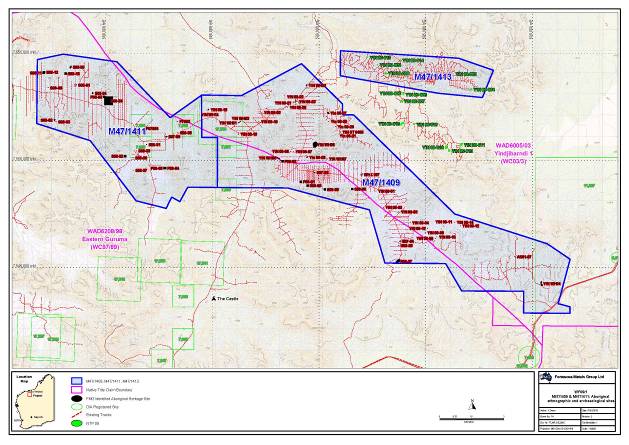

8 On 19 December 2007, the State gave notice under s 29 of the Act of the proposed grant of mining lease M47/1409 to FMG comprising 6838.04 hectares located 45 km west of Wittenoom. The proposed lease area is overlapped as to 74.35 per cent by the native title application.

9 On 30 January 2008, the State gave notice under s 29 of the Act of the proposed grant of mining lease M47/1411 to FMG comprising 3500.47 hectares located 58 kilometres west of Wittenoom. The lease area was overlapped as to 4.98 per cent by the native title application.

10 On 23 April 2008, the State gave notice under s 29 of the Act of the proposed grant of mining lease M47/1413 to FMG comprising 1037.12 hectares located 45 kilometres west of Wittenoom. The lease area was overlapped entirely by the native title application.

11 The area of proposed mining lease M47/1409 was overlapped as to 25.65 per cent by a native title determination in favour of the Eastern Guruma People. The area of the proposed mining lease M47/1411 was overlapped as to 95.02 per cent by the native title determination in favour of the Eastern Guruma People. The native title is held by the Wintawari Guruma Aboriginal Corporation.

12 The lease areas, their relation to each other, and to the registered native title claim are depicted in the diagram below.

13 On 28 November 2008, being a date more than six months after the s 29 notice was given, FMG applied under s 35 in respect of M47/1413 for a future act determination under s 38 of the Act. The application was made on the basis that the negotiation parties had not reached agreement within six months of the State giving notice of its intention to grant the lease.

14 On 23 January 2009, being more than six months after the s 29 notice was given, FMG applied under s 35 in respect of M47/1409 and M47/1411, for a future act determination under s 38 of the Act on the basis that the negotiation parties had not reached an agreement within the designated time.

15 In view of the native title determinations in favour of the Eastern Guruma People in respect of parts of the area of the proposed mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411, the Wintawari Guruma Aboriginal Corporation was a party to the inquiry by the Tribunal. However, it made no submissions and took no part in the appeal to the primary judge or in appeal WAD 193 of 2010.

RELEVANT STATUTORY PROVISIONS following a future act inquiry

16 The kind of future act determinations which the arbitral body must make is prescribed by s 38(1) which requires that:

… the arbitral body must make one of the following determinations:

(a) a determination that the act must not be done;

(b) a determination that the act may be done;

(c) a determination that the act may be done subject to conditions to be complied with by any of the parties.

17 Section 39(1), (2) and (3) provide the criteria for making arbitral body determinations as follows:

(1) In making its determination, the arbitral body must take into account the following:

(a) the effect of the act on:

(i) the enjoyment by the native title parties of their registered native title rights and interests; and

(ii) the way of life, culture and traditions of any of those parties; and

(iii) the development of the social, cultural and economic structures of any of those parties; and

(iv) the freedom of access by any of those parties to the land or waters concerned and their freedom to carry out rites, ceremonies or other activities of cultural significance on the land or waters in accordance with their traditions; and

(v) any area or site, on the land or waters concerned, of particular significance to the native title parties in accordance with their traditions;

(b) the interests, proposals, opinions or wishes of the native title parties in relation to the management, use or control of land or waters in relation to which there are registered native title rights and interests, of the native title parties, that will be affected by the act;

(c) the economic or other significance of the act to Australia, the State or Territory concerned, the area in which the land or waters concerned are located and Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders who live in that area;

(e) any public interest in the doing of the act;

(f) any other matter that the arbitral body considers relevant.

Existing non native title interests etc.

(2) In determining the effect of the act as mentioned in paragraph (1)(a), the arbitral body must take into account the nature and extent of:

(a) existing non native title rights and interests in relation to the land or waters concerned; and

(b) existing use of the land or waters concerned by persons other than the native title parties.

Laws protecting sites of significance etc. not affected

(3) Taking into account the effect of the act on areas or sites mentioned in subparagraph (1)(a)(v) does not affect the operation of any law of the Commonwealth, a State or Territory for the preservation or protection of those areas or sites.

THE REASONING OF THE TRIBUNAL

18 On 13 August 2009 the Tribunal made a determination under s 38(1)(c) of the Act that, subject to the imposition of certain conditions, the grant of mining lease M47/1413 to FMG may be done.

19 On 27 August 2009 the Tribunal made a determination under s 38(1)(c) of the Act that, subject to the imposition of certain conditions, the grant of mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411 to FMG may be done.

20 The Tribunal delivered separate reasons in each application. However, much of the argument was common to both applications. The Tribunal therefore set out its reasons at length in matter WF08/31 concerning mining lease M47/1413 and adopted those reasons where the same issues arose in WF09/1 relating to mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411.

21 Separate issues arose in relation to the sites of and ceremony connected with the sacred stones, called gandi on the area of mining lease M47/1413, and sites of and ceremony connected with the collection of ochre on the area of mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411. The Tribunal dealt with those issues separately in reasons related to the relevant mining leases.

22 The following description of the reasons of the Tribunal relates to WF08/31. Following that description, the separate issues concerning the ochre sites addressed by the Tribunal in WF09/1 will be dealt with.

The Section 116 Issue

23 The Tribunal first considered the argument of the appellants based on s 116 of the Constitution which provides:

The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth. [Emphasis added]

24 The appellants contended that mining on the land would prevent the exercise of their religion. Section 38 and s 39 of the Act should be construed, it was said, to avoid invalidity as a result of the sections failing to comply with s 116. Hence, the appellants submitted that, by operation of s 116 of the Constitution, the Tribunal should determine that the grants not be made, or made only on condition that the appellants and FMG reach an agreement about the activities to be conducted on the land.

25 The Tribunal accepted, for the purpose of argument, that the beliefs and practices of the appellants amounted to a religion. It considered that Kruger v Commonwealth of Australia (1996) 190 CLR 1 (Kruger) established that a law is a law for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion within the meaning of s 116 where that is the purpose, rather than the effect, of the law. The Tribunal held that s 38 and s 39 of the Act did not have the intention, design, purpose or effect of prohibiting or seeking to prohibit the free exercise of religion. Consequently, the Tribunal held that it was not bound by the operation of s 116 to determine that the mining leases could not be granted or only granted on the condition that the appellants’ consent.

The International Instruments Issue

26 The Tribunal then rejected the appellants’ argument that international instruments relating to indigenous people should be used to construe s 38 and s 39. It held that no occasion arose for the use of international instruments because there was no ambiguity to be resolved in the interpretation of s 38 and s 39.

The Section 39 considerations

27 Following the discussion of the s 116 and the international instruments issues, the Tribunal set out the evidence relied upon by each of the parties and their submissions.

28 There was evidence from FMG about the extent and method of the mining operation which it intends to conduct on the area of the lease. It aims to extract 100 million tonnes of iron ore. The iron ore varies in thickness from a few metres to 60 metres. It will be extracted using an open pit mine method. Strips of a minimum width of 100 metres would be exposed, and the pit walls would be up to 60 metres deep. Stockpiles would be necessary. The Tribunal concluded that the mining operation would create a significant ground disturbance to most of the areas of the proposed leases.

29 The State said that it intended to impose four extra conditions on mining lease M47/1413 in order to provide certain protections in favour of the appellants. Those extra conditions would be:

1. Any right of the native title party (as defined in Sections 29 and 30 of the Native Title Act 1993) to access or use the land the subject of the mining lease is not to be restricted except in relation to those parts of the land which are used for exploration or mining operations or for safety or security reasons relating to those activities.

2. If the grantee party gives a notice to the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee under section 18 of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (WA) it shall at the same time serve a copy of that notice, together with copies of all documents submitted by the grantee party to the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee in support of the application (exclusive of sensitive commercial and cultural data), on the native title party.

3. Where the grantee party submits to the State Mining Engineer a proposal to undertake developmental/productive mining or construction activity, the grantee party must give to the native title party a copy of the proposal, excluding sensitive commercial data, and a plan showing the location of the proposed mining operations and related infrastructure, including proposed access routes.

4. Upon assignment of the mining lease the assignee shall be bound by the conditions.

30 Next, the Tribunal set out in full the two affidavits sworn by Mr Michael Woodley filed on behalf of the appellants. He was accepted as a senior law man who spoke on behalf of the appellants. His evidence was uncontested and the Tribunal said that it accepted this evidence.

31 Having set out the evidence and submissions of each of the parties, the Tribunal addressed each of the requirements of s 39(1) and (2) of the Act. In its consideration of the matters to be addressed under s 39(1)(a)(i) of the Act, the Tribunal recounted and analysed much of the evidence relied upon by the appellants. It used that evidence and analysis in its later consideration of the other matters which had to be addressed under s 39(1) of the Act. In this section of its reasons the Tribunal observed that the land was unallocated Crown land, and the appellants had exercised their native title rights and interests without interference by the activities of others in the past or the present. The Tribunal said:

[48] In his affidavits, Mr Woodley gives eloquent testimony to the sincerity and depth of the attachment of the Yindibarndi People to the country, including the area of the proposed lease. He explains, in a comprehensive fashion, the foundation of the Yindjibarndi People’s ownership of Yindjibarndi country, telling some of the stories which led to the creation of the country and recounting the laws which are imposed upon the Yindjibarndi in the maintenance of their religious obligations to the creation spirit (Marrga) the sun god (Minkala) and their ancestors. In his first affidavit he makes the fundamental point that the Yindjibarndi

‘do not see, or feel, ourselves as being separate from the country because we were put into that country and we remain in it’ (1.8)

Mr Woodley goes on to recount the creation story of the Yindjibarndi, to outline the law or Birdarra of the Yindjibarndi and the obligations that it imposes upon the Yindjibarndi. The fundamental obligation according to Mr Woodley is to protect that country and ensure that strangers do not enter the country without acknowledging the law and ancestors of the Yindjibarndi. The obligation is absolute:

‘It doesn’t matter if we were unable to stop the Law from being broken, it is our duty to ensure it is not.’ (3.2)

…

[51] Mr Woodley believes that by allowing the three proposed mining leases to be granted and used by the grantee party in the way that is proposed, without agreement or consent of the Yindjibarndi People, will demonstrate to the Yindjibarndi, once again, that they are powerless to protect their religious practices and beliefs and are, consequently, not worthy of the country that has been entrusted to them.

32 Then, the Tribunal referred to the evidence concerning the collection of gandi as follows:

[52] Mr Woodley also makes specific references to the impact of the grant of the proposed lease M47/1413. He says that the Ganyjingarringunha is a river that runs through Ganbulanha and that the Ganyjingarringunha Yaaya, is the eastern part of this river which runs through the middle of M47/1413. … These areas within M47/1413 are used each year to collect the Gandi (sacred stones) for use in our Birdarra Law ceremonies (5.8).

[53] Mr Woodley deposes that one of the places where the Yindjibarndi go each year to collect Gandi is within the area of the proposed lease and that if the grantee party was allowed to mine there, they would destroy these areas.

33 The Tribunal then observed:

[55] Mr Woodley concludes at 5.13 of his first affidavit by stating that the grant of the proposed lease would prevent the Yindjibarndi from

‘exercising our right and our religious obligation to occupy, use, possess and enjoy the three areas to the exclusion of all that those that we invite to share with us in its use’

34 About the effect of the mining leases on the enjoyment of the registered native title rights and interests under s 39(1)(a)(i) the Tribunal said:

[59] I think it clear from the evidence of Mr Woodley that, notwithstanding the significant religious and spiritual enjoyment of the area that will be disrupted by the grant of the proposed lease, there will indeed be a significant physical interruption to access and enjoyment of the area and their exclusion from a substantial part of it for a significant period of time. Setting aside the matters I need to address in relation to s 39(1)(a)(ii) - (v) which will be dealt with below, the evidence before the Tribunal is that the native title party visit the area of the proposed lease on an annual basis, largely for the purpose of collecting the Gandi and ochre and to conduct Wuthurru ceremonies. The evidence of this access and use is sketchy and general compared to the evidence given by Mr Woodley relating to the cultural affront and religious offence the Yindjibarndi feel because of the access and use of the area without their sanction. I do accept that the first of the extra conditions proposed by the Government party will mitigate the impact of the interruption to the exercise of native title rights, but that interruption will be substantial.

35 The attention of the Tribunal was next directed to the effect of the mining leases on the way of life, culture and traditions of the appellants under s 39(1)(a)(ii). Mr Woodley deposed to the despair which would be felt in the community if the appellants were not able to manage their land by controlling access to it as their cultural obligations dictated. The Tribunal observed that if the lack of acknowledgment by society of the appellants’ right to control their land was destructive of their culture, it would not have survived so far. The Tribunal concluded at [62]:

As with a number of other factors which will be dealt with in this determination, the question, ultimately, is one of balance. In this circumstance, it is my view that the evidence suggests that there will be some disruption or effect upon the Yindjibarndi’s view of the potency and strength of its culture and traditions, but there will be no real or tangible interference with the way of life of the Yindjibarndi.

36 The discussion concerning the effect of the mining leases on the development of the social, cultural and economic structures of the appellants under s 39(1)(a)(iii) which followed has little bearing on the issues in contention and need not be described further in these reasons.

37 The Tribunal next considered the effect of the mining leases on the freedom of the appellants to access the area and the freedom of the appellants to carry out rites, ceremonies or other activities of cultural significance in accordance with their traditions under s 39(1)(a)(iv). The Tribunal accepted the evidence that the appellants visited the area annually to gather gandi. Then, the Tribunal said at [67]:

There is no specific reference in Mr Woodley’s affidavit as to whether or not the ceremonies themselves are conducted within the area of the proposed lease, only that the Gandi are collected from the area for use in Birdarra Law ceremonies. Whilst I accept the Government party’s contention (at 44) that “freedom of access” is ensured subject to the first extra condition which may be imposed on the proposed lease, I again note the proposed mining operations will impact the majority of the area of the proposed lease.

38 The Tribunal then referred to three archaeological survey reports prepared for FMG with the assistance of the appellants. The Tribunal noted that there was no reference to the gandi in those reports, and it considered reasons why there was no such reference. The Tribunal continued at [68]:

The reports do identify a significant number of areas which are both of archaeological and ethnographic importance and recommend that certain sites be avoided or to the extent that they are to be interfered with, that prior consultation take place between the Yindjibarndi and the grantee party.

39 The Tribunal concluded in relation to s 39(1)(a)(iv):

[69] … My impression of the evidence from the native title party is that Gandi can be found throughout Yindjibarndi country, including those areas within the proposed lease, but by no means limited to that area. If the Gandi were to be destroyed or interfered with there may well be impact on the capacity of the native title party to conduct ceremonies. However, in my view such destruction or interference is highly unlikely. I have come to that view because the grantee party has conducted comprehensive surveys of the land which has resulted in a considerable amount of information relating to the location of sites and artifacts within the area of the proposed lease and which recommends that no interference could occur without compliance with the AHA requirements and in consultation with the Yindjibarndi. I have been provided with no evidence to suggest that the grantee party will not continue to ensure that it abides by the recommendations that have previously been provided to it, including the need for further consultation with the Yindjibarndi before any mining activities are undertaken. The discussion below relating to s 39(1)(a)(v) is, in my view, directly linked to the question of access for ceremonial purposes and needs to be considered before I can reach conclusions about the extent of the impact of the grant of the proposed lease.

40 Next, in its consideration of the effect of the grant of the mining lease on any area or site on the land of particular significance to the appellants under s 39(1)(a)(v) the Tribunal referred to the evidence of Mr Woodley that one of the collection places for gandi was in the area which will be affected by the grant of mining lease M47/1413. The Tribunal was concerned that the place where gandi were collected was not referred to in the three archaeological reports which were in evidence. The Tribunal said at [72]:

If there is a specific place where the Gandi stones are found, that place should have been identified in at least one of the three reports conducted by the archaeological consultants on behalf of the grantee party and with participation from members of the native title party. If it was not, it should be in the future and, presumably, it will be protected. As I have said earlier, it appears that the Gandi are found across the Yindjibarndi land. It is not clear to me whether they are scattered randomly across that country, or found in individual localised pockets which can be identified and protected. If it is the former, there may be significant difficulties for the grantee party in overcoming the requirement of the AHA [Aboriginal Heritage Act]. However, the evidence before me currently, specifically in relation to the proposed lease, is that there is one place within that area where the Gandi are collected. I am concerned about the anomaly created by Mr Woodley’s evidence of the collection of the Gandi on various areas, including the proposed lease, but there being no mention of Gandi in any of the reports. … The evidence in relation to the Gandi on the proposed lease is insufficiently specific for me to make a determination one way or the other as to their locality, albeit that I accept that if there are Gandi in the vicinity, they are no doubt of particular significance to the Yindjibarndi.

41 The Tribunal examined the evidence about the effect of the mining leases on the conduct of ceremonies related to the collection of ochre or gandi and concluded that there was no evidence that there were any particular ceremonies which had to be conducted within the area of the proposed lease. The Tribunal continued at [74]:

The balance of the evidence, however, suggests that the areas where the ochre quarries and Gandi are located are within the proposed lease and are areas of particular significance to the native title party. The extensive nature of the grantee party’s activities on the proposed lease may make it difficult to access these areas, even though there is no evidence to suggest that the grantee party would attempt to deliberately exclude them. … Although they are unidentified, it would seem, if the areas where Gandi are collected within the proposed lease can be identified, they could be protected also.

42 The Tribunal explained how the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (WA) (the AHA) provided for protection of aboriginal sites and how it would mitigate the potential threat to places of significance to the appellants. The AHA makes it an offence to excavate, destroy or damage such a site without authority. If authority is sought, the AHA requires consultation with indigenous stakeholder groups. The Tribunal determined that the second and third extra conditions proposed to be included in the mining lease by the State would require FMG to give notice to the appellants of the location of mining operations and of any application for authority under the AHA (at [77]). This would then allow the appellants to become involved in the consultation. The Tribunal said:

[78] I accept that the grantee party fully understand their obligations under the AHA and has complied with them to date. I am satisfied they will continue to do so and take whatever action is necessary to avoid interference with sites of particular significance to the native title party in accordance with their traditions.

43 The Tribunal briefly considered, under s 39(1)(b), the interests, proposals, opinions or wishes of the appellants in relation to the management, use or control of land or waters in relation to which there are registered native title rights and interests that would be affected by the mining leases. It also considered, under s 39(1)(c), the economic or other significance of the mining leases to Australia, the State, the area in which the land or waters concerned are located and to the appellants who live in the area under s 39(1)(c). Nothing turns on this discussion in these appeals.

44 Under s 39(1)(e) the Tribunal concluded that, because the mining industry is of considerable economic significance to Western Australia and Australia, the public interest was served by the grant of the mining leases. The Tribunal came to this conclusion by adopting the findings on public interest expressed in the decision of the Tribunal in Western Australia v Thomas (1996) 133 FLR 124.

45 The only matter to which the Tribunal had regard under s 39(1)(f) was the environmental impact of the grant of the mining lease. There was no evidence on that subject.

46 The Tribunal concluded that:

[90] … the grant of the proposed lease, without condition, would have a significant impact on the capacity of the native title party to access and use the area within the proposed lease for a variety of purposes, including general access, as well as to the conduct of ceremonies and the protection of sites. A determination that the act may be done will also have a significant impact on Yindjibarndi morale by undermining their belief in their capacity to protect their country in accordance with their traditional laws, customs and religious beliefs. On the other hand, I find that the grantee party and the Government party have demonstrated a willingness to cooperate fully in ensuring that, as far as the law requires, that the native title party’s rights and interests will be affected as little as possible in the circumstances. The proposal of the Government party to impose the four extra conditions will significantly mitigate the impact of the grant of the proposed lease on the interests of the native title party. As discussed earlier, it is my view that the Tribunal ought to make the determination on condition that these four extra conditions are imposed. I come to this conclusion by way of the information that has been collected in the various heritage surveys which have been conducted on behalf of the grantee party and of which the grantee party now has actual notice. The imposition of the first and, to a lesser extent, the second and third extra conditions, which the Government proposes to impose on the grant of the proposed lease will have an additional protective effect.

47 What now follows is reference to the reasons of the Tribunal in WF09/1 relating to the proposed grant of mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411 insofar as they differ from the reasons given in WF08/31.

48 The mining method proposed in these areas is the same as the method proposed in the area of proposed mining lease M47/1413, save that the aim in this case is to extract 400 million tonnes from the drainage valleys in the Hamersley Range in the areas of each of the proposed mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411.

49 The Tribunal recorded the evidence specific to WF08/31 at [38] as follows:

There is a Maliya (honey) Thalu [site] located not far from the area where FMG wants the Tenements, and each year this Thalu is worked by [Yindjibarndi] men from the Banaga and Burungu Galharra groups. The ochre that we need to work this Thalu comes from the ochre quarry that is located in the area covered by M47/1409 … Working the Maliya Thalu in Yindjibarndi country requires that we access and use the ochre quarry which is located in the area covered by M47/1409. If FMG is allowed to use the tenements in the way that it plans to, there will be no ochre left at that place and we will not be able to work the Maliya Thalu

50 As to the effect of the mining leases on the appellants’ enjoyment of the registered native title rights and interests under s 39(1)(a)(i), the Tribunal concluded at [36]:

[T]he evidence before the Tribunal is that the Yindjibarndi native title party visit the area of the proposed leases on an annual basis to conduct Thalu and Wuthurru ceremonies and to collect ochre from the area of M47/1409. The evidence of this access and use is sketchy and general compared to the evidence given by Mr Woodley relating to the cultural affront and religious offence the Yindjibarndi feel because of the access and use of the area without their sanction. I do accept that the first of the extra conditions proposed by the Government party will mitigate the impact of the interruption to the exercise of native title rights, but that interruption will be substantial.

51 In its consideration of the effect of the mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411 on the appellants’ freedom of access and freedom to carry out rights and ceremonies under s 39(1)(a)(iv), the Tribunal referred to the evidence of Mr Woodley of the existence of an ochre quarry on the area of the mining lease M47/1409. It found no evidence of ceremonies being conducted on the area of that proposed lease. The ochre quarries were not recorded on the archaeological reports conducted by FMG with the assistance of the appellants. The Tribunal said that those reports seemed comprehensive. The Tribunal considered reasons why the site of the ochre quarry was not recorded in the reports. It said at [43]:

I have come to the view, however, that because the grantee party has conducted a number of surveys of the land which has resulted in the collation of a considerable amount of information relating to the location of sites and artefacts within the area of the proposed leases, and in which recommendations are made in relation to non interference within those sites without the compliance of AHA requirements and in consultation with the Yindjibarndi, the effect of the grant will be considerably mitigated. I have been provided with no evidence to suggest the grantee party will not continue to ensure that it abides by the recommendations that have previously been provided to it, including the need for further consultation with the Yindjibarndi before mining activities are undertaken. In addition, the second and third extra conditions proposed by the Government party will assist the Yindjibarndi native title party in dealing with these matters.

52 Just as in WF08/31 the Tribunal regarded its consideration under s 39(1)(a)(iv) as relevant to the effect of the mining leases on areas or sites of particular significance under s 39(1)(a)(v). The Tribunal said [47]:

In any event, I consider that the mitigating effect of the AHA, as I have set out in FMG Pilbara 2 at [75] – [77], the knowledge that the grantee party has of both registered sites and other sites identified within its surveys, and the information it has been provided with in relation to the ochre sites during the course of this proceedings, together with the four extra conditions, which the Government party intends to impose, will have a significant protective effect on the capacity of the Yindjibarndi native title party to conduct ceremonies and protect sites of particular significance, despite the grant of the proposed leases to the grantee party.

53 The Tribunal continued at [48]:

I accept that the grantee party fully understands their obligations under the AHA and has complied with them to date. I am satisfied that they will continue to take whatever action is necessary, particularly in light of the amount of information they have in their possession, to ensure avoidance of interference with sites of significance or interruption of the conduct of ceremonial activity in accordance with the Yindjibarndi native title party’s traditions, as far as it is possible to do so. I would also recommend that if the ochre quarry relevant to the conduct of the Maliya Thalu can be identified, that it ought to be given specific protection, and access to it by the Yindjibarndi native title party maintained.

54 As in WF08/31 the Tribunal concluded that the proposed grant of the mining leases would, without conditions, have a significant effect on the appellants’ capacity to access and use the land for ceremonial purposes and to collect ochre. However, the demonstrated willingness of the State and FMG to cooperate with the appellants, and the imposition of the four extra conditions, the Tribunal considered, would significantly mitigate the impact of the mining leases on the appellants.

THE REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

Introduction

55 On 11 September 2009, the appellants filed a notice of appeal from the determination in relation to the grant of mining lease M47/1413. This appeal was nominated WAD 161 of 2009.

56 On 14 October 2009, the appellants filed a notice of appeal from the determination in relation to the grant of the mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411. This appeal was nominated WAD 168 of 2009.

57 The appeals were brought under s 169(1) of the Act which provides:

A party to an inquiry relating to a right to negotiate application before the Tribunal may appeal to the Federal Court, on a question of law, from a decision or determination of the Tribunal in that proceeding.

58 The primary judge heard both appeals together. Of the seven grounds of appeal which were substantially the same in each appeal, only the first two grounds are relevant to the present appeal.

59 By the first ground, the appellants contended that “the Tribunal erred by determining that s 38 and s 39 of the Act did not have the intention, design, purpose or effect of prohibiting or seeking to prohibit the free exercise of the applicants’ religion, contrary to s 116 of The Constitution”.

60 Both the State and FMG filed Notices of Contention which contended that:

If (which is denied) the learned Tribunal Member erred in determining that sections 38 and 39 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) do not have the intention, design, purpose or effect of prohibiting or seeking to prohibit the free exercise of the applicant’s religion, contrary to section 116 of the Constitution, then the First Respondent contends that the learned Tribunal Member was nevertheless correct in finding that sections 38 and 39 do not contravene section 116 of the Constitution because:

(1) The test for inconsistency between Commonwealth legislation and section 116 of the Constitution is whether or not the legislation in question has the purpose of prohibiting the free exercise of religion; and

(2) Sections 38 and 39 do not have that purpose; and

(3) The learned Tribunal Member found, in substance, that sections 38 and 39 do not have that purpose.

(4) The making of a decision by the Tribunal is not an act which prohibits or affects the free exercise of the Appellant’s religion; and

(5) If any act is capable of having the effects contended for by the Appellant it could only be the grant, pursuant to the Mining Act 1978 (WA) of the mining lease the subject of the determinations; and

(6) Section 116 of the Constitution does not apply to State legislation or administrative acts done thereunder.

61 Notices of a Constitutional Matter under s 75B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) were served on the State and Commonwealth Attorneys, inter alia, in relation to the s 116 issue. No intervention was sought in response to the notices.

62 By the second ground of appeal the appellants contended that the Tribunal erred in law in determining that international instruments were irrelevant to its inquiry because there is no relevant ambiguity in s 39 of the Act.

The Section 116 Issue

63 The primary judge rejected the appellants’ contention that the effect or result of the Tribunal’s application of s 38 and s 39 of the Act was that the appellants were prevented from carrying out their religious obligation to manage and control the land and ensure that strangers did not enter without agreement and other identified religious observances.

64 The primary judge said that the argument relied on the wrong test for inconsistency between s 38 and s 39 of the Act, on the one hand, and s 116 of the Constitution on the other. He said that the effect or result of the application of a statute is not the primary test for assessing whether the statute is consistent with s 116. Section 116 directs attention primarily to the purpose of the impugned law rather than to its effect or result. He said that it may be that the effect of the law, in some circumstances, could assist in construing its purpose but the effect of the law is not the starting point. He then concluded that there was no indication that the purpose of s 38 or s 39 of the Act was for prohibiting the free exercise of religion.

65 The primary judge then referred to Kruger where the High Court considered the validity of a Northern Territory ordinance which authorised the removal of aboriginal children from their families and communities. The Ordinance was challenged on a number of grounds including inconsistency with s 116. The challenge was rejected and the Court confirmed that the word “for” in the expression in s 116 “for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion” directs attention to the objective or purpose of the legislation. The primary judge relied on the following passages from the judgments in Kruger.

66 Gummow J (with whom Dawson and McHugh JJ agreed) said at 160:

“Purpose” refers not to the underlying motive but to the end or object the legislation serves.

67 Brennan CJ said at 40:

… none of the impugned laws on its proper construction can be seen as a law for prohibiting the free exercise of a religion … To attract invalidity under s 116, a law must have the purpose of achieving an object which s 116 forbids. None of the impugned laws has such a purpose …

68 Toohey J said at 86:

It may well be that an effect of the Ordinance was to impair, even prohibit the spiritual beliefs and practices of the Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory, … But I am unable to discern in the language of the Ordinance such a purpose.

69 At 132, Gaudron J said:

The use of the word “for” indicates that purpose is the criterion and the sole criterion selected by s 116 for invalidity. Thus, purpose must be taken into account. Further, it is the only matter to be taken into account in determining whether a law infringes s 116.

70 The primary judge said that to the extent that a question of law arose the decision of the Tribunal was consistent with the authorities on s 116. He said that the laws may have descriptive or limiting effects on religious freedom without contravening the protection in s 116.

71 The primary judge then held that a further difficulty with the s 116 argument for the appellants was that s 116 is directed at Commonwealth legislation. The complaint of the appellants was not against the enactment or content of s 38 or s 39 but rather against the decision made by the Tribunal. The appellants contended that s 116 acts to modify the effect of s 38 and s 39 by limiting the kinds of determinations the Tribunal may make to only those which do not impair religious freedom. His Honour held that s 116 is directed to the making of Commonwealth laws not with their administration or with executive acts done pursuant to those laws. Section 116, he held, is not capable of regulating or invalidating the Tribunal’s decision. The relevant inquiry is whether the Commonwealth was able to enact s 38 and s 39.

72 The primary judge said that a law which authorises administrative acts or decisions which prohibit the free exercise of religion will only be a law for prohibiting the free exercise of religion and invalid pursuant to s 116 if the purpose and content of the law is established. Neither s 38 or s 39, nor the Tribunal’s determinations prohibit religious freedom because they do not prohibit anything. If any act did, it would be the grant of the mining leases. Those grants are separate administrative acts and subject to separate considerations and controls. The grants are made under the Mining Act 1978 (WA) (the Mining Act) which, being State legislation is not subject to s 116.

73 The primary judge then said that if the Tribunal did identify the relevant test as one of “intention, design, purpose or effect”, giving the widest possible interpretation of the test rather than confining the question to the purpose of the legislation, the same result would have followed as if the Tribunal had applied the more confined test.

74 Finally, the primary judge said that the Tribunal found as a fact that the grant of the mining leases, subject to conditions, would not interfere with the religious freedom of the appellants. On the evidence before it the Tribunal found that the religious beliefs and observances of the appellants, like the religious beliefs and observances of others, do not need to be fully realised in order to achieve compliance with the religious system or orthodoxy of the appellants. The appeal from the Tribunal to the Court under s 169 of the Act is limited to questions of law. The primary judge found that there was no error of law disclosed in respect of this finding of fact. It was made having regard to the evidence led before the Tribunal and was open to the Tribunal.

The International Instruments Issue

75 The primary judge rejected the appellants’ argument that the Tribunal erred in concluding that the terms of the ICCPR and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN Declaration) could not be used to construe s 38 and s 39 of the Act because there was no relevant ambiguity in these statutory provisions.

76 Before the Tribunal the appellants argued that the guarantee of religious freedom enshrined in s 116 of the Constitution is also enshrined in Art 18 and Art 27 of the ICCPR. The primary judge observed that, in accordance with those entitlements, the appellants have the right to enjoy their culture, practise their religion, and manifest their religious beliefs, observances and practices. Article 18 of the ICCPR further provides that the freedom to manifest ones religion or beliefs may be limited only as is necessary to protect public safety, order, health, morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. The appellants’ right to freely practise religion was reaffirmed by the recent government endorsement of the UN Declaration.

77 The primary judge accepted that merely because the ICCPR and the UN Declaration had not been incorporated into domestic law did not mean that their acceptance had no significance for Australian law. He referred to the well known passages in the judgment of Mason CJ and Deane J in Minister of State for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Teoh (1995) 183 CLR 273 at 286 – 288 (Teoh), of Brennan J in Mabo v Queensland [No 2] (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 42 and of Gummow and Hayne JJ in Kartinyeri v Commonwealth (1998) 195 CLR 337 at [97], which hold that courts should favour a construction of legislation which conforms with Australia’s obligations under a treaty or convention, particularly where the legislation is enacted after, or in contemplation of, the entry into or ratification of the relevant international instrument. The canon of construction applies where the legislative provision is ambiguous, although there are strong reasons for rejecting a narrow view of the concept of ambiguity. The primary judge also approached the construction of s 38 and s 39 of the Act on the presumption referred to in Coco v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 427 at 437, namely, that parliament does not intend to abrogate human rights and fundamental freedoms unless it makes its intention clear by unmistakeable and unambiguous language.

78 However, the primary judge concluded:

107 The difficulty for the appellant is that no ambiguity has been identified. In the absence of a relevant ambiguity, there can be no scope for considering the relevance of any international instrument such as the ICCPR.

108 Further, assuming some unidentified ambiguity existed, the Yindjibarndi have not articulated how the interpretation adopted by the Tribunal (assuming it adopted an interpretation) was inconsistent with the ICCPR.

THE NOTICES OF APPEAL

79 On 20 July 2010, the appellants filed a Notice of Appeal from the orders made by the primary judge in WAD 161 of 2009 dismissing the challenge to the Tribunal’s determination in respect of the proposed grant of mining lease M47/1413. This appeal is WAD 192 of 2011.

80 On 20 July 2010 the appellants filed a Notice of Appeal from the orders made by the primary judge in WAD 168 of 2009 dismissing the challenge to the Tribunal’s determination in respect of the proposed grant of mining leases M47/1409 and M47/1411. This appeal is WAD 193 of 2010.

81 The original Notices of Appeal were subsequently amended and replaced with Amended Notices of Appeal filed on 18 November 2010. Several of the grounds of appeal in the Amended Notices of Appeal were not addressed in the written submissions of the appellants but were not expressly abandoned. Further, the oral argument on the hearing of the appeal relied on grounds which were not pleaded in the Amended Notices of Appeal. Some of these grounds had not been argued before the primary judge and no application was made at the hearing of the appeal for those arguments to be relied upon at the hearing of the appeals.

82 The conduct of the appeals in these respects was so disorganised and below an acceptable standard that we have reluctantly drawn attention to the matter. In the result, the hearing of the appeals was confused and took longer than was necessary. The State and FMG were not given proper notice of the arguments to be relied upon. Consequently, they were not able to be of as much assistance to the Court as would have been the case if the appellants’ written submissions had reflected the arguments to be relied upon.

83 In order to bring some definition to the arguments upon which the appellants intended to rely, during the hearing of the appeals, the Court required the appellants to prepare Further Amended Notices of Appeal. This was done on 7 December 2010, the second and final day of the hearing of the appeals. As the State and FMG did not oppose the filing of the Further Amended Notices of Appeal, leave was given to the appellants to do so.

84 The grounds of appeal in each of the Further Amended Notices of Appeal followed the same structure. However, within that structure, the grounds in WAD 192 of 2010 relate to the arguments concerning the gandi, whilst the grounds in WAD 193 of 2010 relate to the arguments concerning the use of ochre. The grounds of appeal are set out in the following section of the reasons at the beginning of the consideration of the argument relating to those grounds. Where the grounds in WAD 193 of 2010 diverge from the grounds in WAD 192 of 2010, the divergence is shown in brackets.

Consideration

The Section 116 Issue

85 Ground 1 of the Further Amended Notices of Appeal stated:

The Court erred in law in finding that the National Native Title Tribunal (“Tribunal”) had made no error in determining that sections 38 and 39 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“NTA”) do not have the intention, design, purpose or effect of prohibiting or seeking to prohibit the free exercise of the applicant’s religion, contrary to section 116 of the Constitution.

Particular A

The Tribunal failed to adopt a liberal construction of s. 116 of the Constitution and failed to consider, in respect of such construction, the effect of:

i. Australia’s accession to the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”);

ii. Articles 18 and 27 of the ICCPR; and

iii. Australia’s endorsement of the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Particular B

The Appellants’ traditional beliefs and practices constitute a “religion” within Section 116.

Particular C

Section 116 applies to and overrides all powers vested in the Parliament to make laws, including Section 51(26).

Particular D

As a constitutional guarantee of a fundamental human right, Section 116 is to be interpreted liberally and not pedantically, such that laws do not achieve indirectly what the Section prohibits directly.

Particular E

The prohibition clause of Section 116 extends to laws, including Section 38 and 39 (“the Sections”) of the NTA:

i. which have incidental but undue effects upon the Appellant’s exercise of their religion;

ii. where those effects are not proportionate or adapted to the objects of the NTA

such that the Sections reveal a purpose prohibited by Section 116.

Particular F

The Tribunal’s interpretation and application of the Sections and consequent damaging effects upon the Appellants’ exercise of their religion has the result that, to the extent that the Sections allegedly authorised such damaging effects, the Sections, and the tribunal’s exercise of power, are both beyond power and invalid.

86 The appellants’ case was considered by the Tribunal and the primary judge on the basis that the appellants’ use of ochre and gandi are religious practices. This approach has not been contested by the State or FMG. Further, if the ochre and gandi sites are dug up in the process of mining iron ore, the appellants will be prevented from continuing to access the ochre and gandi. But, a number of steps are necessary before that outcome will eventuate. The future act determinations by the Tribunal were one step. But they alone will not prevent the appellants continuing their religious practices. FMG will only have authority to mine if the State exercises its power under the Mining Act to grant the mining leases. Western Australian State law also provides for yet a further step, namely, an application under the AHA for authority to excavate or disturb an aboriginal site. Only if FMG obtains authority to interfere with the ochre and gandi sites would the appellants be prevented from continuing to observe those religious practices.

87 Thus, there are a series of actions under Commonwealth and State legislation which must be taken before the appellants’ religious practices are impacted. No doubt for this reason the appellants’ argument accepted that s 38 and s 39 of the Act did not directly achieve a prohibition on the free exercise of religion. The contention, therefore, was that s 38 and s 39 resulted in or had the effect of prohibiting the free exercise by the appellants of their religion.

88 The question thus became whether s 116 of the Constitution operates to invalidate Commonwealth laws which have the indirect effect of prohibiting the free exercise of religion.

89 The primary judge answered this question in the negative. He relied on Kruger. We agree that each of the judges in Kruger, in the passages extracted by the primary judge and which are referred to in these reasons at [66] – [70], establish that the test for invalidity under s 116 is whether the Commonwealth law in question has the purpose of prohibiting the free exercise of religion.

90 In a passage which addresses the application of s 116 to a factual issue comparable to the present, Gummow J said at 161:

The withdrawal of infants, in exercise of powers conferred by the 1918 Ordinance, from the communities in which they would otherwise have been reared, no doubt may have had the effect, as a practical matter, of denying their instruction in the religious beliefs of their community. Nevertheless, there is nothing apparent in the 1918 Ordinance which suggests that it aptly is to be characterised as a law made in order to prohibit the free exercise of any such religion, as the objective to be achieved by the implementation of the law.

91 The Ordinance in Kruger giving power to the Chief Protector of Aboriginals to remove aboriginal children from their families and communities did not directly prohibit religious instruction to those children. The fact that it may have had the effect as a practical matter did not render the Ordinance invalid by reason of a contravention of the prohibition in s 116.

92 Similarly, in the present case, there is nothing on the face of s 38 and s 39 to suggest that they have the object of prohibiting the free exercise of religion. Section 38 specifies the kind of determinations which the arbitral body may make. Section 39 sets out the mandatory criteria which must be addressed by the arbitral body in the course of its inquiry. Some of the mandatory considerations such as the freedom to carry out rites, ceremonies, and other activities of cultural significance in accordance with traditions, which appears in s 39(1)(a)(iv), demonstrate a concern by the legislature with the protection of religious freedom.

93 It follows from the application of the test for invalidity under s 116 of the Constitution explained in Kruger that the appellants’ challenge to s 38 and s 39 on this basis cannot succeed. The primary judge was correct to so hold.

94 The appellants face two further obstacles to success on their case concerning s 116.

95 The Tribunal found as a fact that the appellants access to, and practices concerning, ochre and gandi would be affected as little as possible because the State and FMG had demonstrated a willingness to cooperate fully to that end, and the imposition of the four extra conditions in the mining leases would mitigate the impact of mining on the land. There was thus a finding of fact that the free exercise of religion of the appellants would not be prohibited by the grant of the mining leases on condition. That finding was challenged before the primary judge. He rejected the challenge because the appeal to him under s 169 of the Act was limited to questions of law. He found that there was no legal error made by the Tribunal in arriving at that view of the facts. The finding was open on the evidence before the Tribunal. On the appeal to this Court the appellants do not take issue with the primary judge’s conclusion on this argument. That means that the Tribunal’s finding of fact that the grant of the mining leases on condition will not prohibit the free exercise of the appellants’ religion stands. It follows that the construction argument under s 116 does not arise. There was simply no prohibition on the free exercise of the appellants’ religion. No occasion for the application of s 116 arose. We agree with his Honour’s reasoning on this argument.

96 Finally, we agree with the primary judge that the complaint of the appellants is essentially directed to the determinations of the Tribunal and the consequent grant by the State of the mining leases under State legislation. Section 116 applies to the making of laws by the Commonwealth. It does not apply to the determinations made by the Tribunal, to legislation enacted by State governments, or to actions of the State taken under State legislation. To the extent that the appellants complain about these matters, s 116 has no application.

Use of International Instruments

97 Ground 6 of the Further Amended Notices of Appeal stated:

The Court erred in law in determining that the Tribunal made no error when it held that International Instruments were not relevant to its inquiry because there is no relevant ambiguity in section 39 of the NTA.

Particulars

a. The Tribunal failed to consider and take into account, in addition to the concept of “ambiguity”, principles of statutory interpretation which require that:

i. a statute be interpreted and applied, as far as its language permits, so that it is in conformity and not in conflict with the established rules of international law; and

ii. a statutory provision be interpreted on the presumption that the parliament does not intend to abrogate human rights and fundamental freedoms unless such intention is made unmistakably clear.

b. The Tribunal misapprehended the meaning of “ambiguity” in respect of ss. 39(1) of the NTA.

98 The appellants contended on appeal that the primary judge erred by failing to hold that the Tribunal wrongly concluded that the international instruments, namely, the ICCPR and the UN Declaration, where not relevant to its inquiry because there was no relevant ambiguity in s 38 and s 39 of the Act.

99 The error made by the Tribunal, so the appellants contended, was that it failed to “take into account in addition to the concept of ‘ambiguity’ principles of statutory interpretation which require that a statute be interpreted, so far as its language permits so that it is in conformity and not in conflict with the established rules of international law” [emphasis added].

100 The contention is based on the passage in the judgment of Mason CJ and Deane J in Teoh at 287 – 288 as follows:

Where a statute or subordinate legislation is ambiguous, the courts should favour that construction which accords with Australia’s obligations under a treaty or international convention to which Australia is a party, at least in those cases in which the legislation is enacted after, or in contemplation of, entry into, or ratification of, the relevant international instrument. That is because Parliament, prima facie, intends to give effect to Australia’s obligations under international law.

…

It is accepted that a statute is to be interpreted and applied, as far as its language permits, so that it is in conformity and not in conflict with the established rules of international law. The form in which this principle has been expressed might be thought to lend support to the view that the proposition enunciated in the preceding paragraph should be stated so as to require the courts to favour a construction, as far as the language of the legislation permits, that is in conformity and not in conflict with Australia’s international obligations. That indeed is how we would regard the proposition as stated in the preceding paragraph. In this context, there are strong reasons for rejecting a narrow conception of ambiguity. If the language of the legislation is susceptible of a construction which is consistent with the terms of the international instrument and the obligations which it imposes on Australia, then that construction should prevail. So expressed, the principle is no more than a canon of construction and does not import the terms of the treaty or convention into our municipal law as a source of individual rights and obligations. [Emphasis added]

101 From this passage the appellants extracted the emphasised sentence “If the language of the legislation is susceptible of a construction which is consistent with the terms of the international instrument and the obligations which it imposes on Australia, then that construction should prevail”. At certain points in the argument the appellants appeared to rely on this sentence as establishing a stand alone canon of statutory construction which is not dependent on the existence of ambiguity in the provision under consideration. Rather, Australia’s international obligations are a touchstone against which the words of a provision are to be construed. Applying this approach to s 39 led the appellants to state in their Amended Outline of Submissions at [6.10]:

The Appellants submit that the language of s 39(1)(a)(ii), which required the Tribunal to take into account the effect of the grant of the mining lease on “the way of life, culture and traditions” of the Appellants, puts beyond doubt the question of whether this provision is susceptible of a construction that is consistent with the terms of the ICCPR; Article 27 of which, is directed towards the right to enjoy one’s culture and religion. Accordingly, the Appellants submit that the Tribunal, like the primary judge, was obliged to construe s 39(1)(a)(ii), in a way that ensures conformity with the relevant provisions of ICCPR. Similar contentions are made in respect of the Tribunal’s consideration under s 39(1)(a)(ii) NTA of the development of the Appellants’ “social and cultural structures”, its consideration under s 39(1)(a)(iv), in respect of rites, ceremonies and other activities of cultural significance, and its consideration of “public interest” and “other considerations”, pursuant to 39(1)(e) and (f) respectively, each of which is, in the Appellants’ submission, susceptible of a construction that is consistent with the terms of the ICCPR and Australia’s obligations thereunder.

102 This attempt at analysis reveals the confusion in the argument.

103 Article 27 of the ICCPR provides:

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language.

104 The appellants argued that s 39 can be construed consistently with this obligation. When asked by the Court in the course of oral submissions how s 39 should be construed consistently with Art 27, counsel responded that s 39 required the Tribunal to make a determination which allowed the appellants to continue to enjoy their culture or practise their religion.

105 The difficulty with this approach is that the plain language of s 38 and s 39 is inconsistent with a mandatory requirement that the Tribunal allow for the enjoyment of culture or practice of religion. Section 39 prescribes those matters which the Tribunal is required to consider in making its determination. Section 38 allows the Tribunal to determine that the future act be done, not be done, or be done subject to conditions. The language of these two sections leaves no room for the contention that the Tribunal is bound to come to a particular decision favouring the freedom to enjoy culture or practise religion. Thus, even applying the stand alone test proposed by the appellants, Art 27 can have no part to play in the construction of s 38 and s 39 of the Act because the two sets of provisions are directed to quite different subjects and the international obligations can provide no assistance to the construction of provisions which govern the scope of the Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

106 In any event, neither logic nor the judgment in Teoh support the use of Australia’s international obligations in the interpretation of the provisions under consideration in the absence of any ambiguity in the language of the provisions.

107 If a provision has a clear meaning then that meaning either reflects Australia’s international obligations or it does not. There is no scope for the application of any canon of construction to establish the meaning. But where there is more than one possible meaning of the provision, the canon of construction favouring Australia’s international obligations is available to identify the intended meaning. In other words, the canon of construction only has work to do where the provision is open to more than one interpretation. This is the reason for the reference in the judgment in Teoh to the use of the canon of construction for the purpose of resolution of ambiguity.

108 Thus, the primary judge was correct to hold that a statutory provision will be construed so as to conform with Australia’s international obligations only in order to resolve ambiguity in the language of the provision.

109 As explained earlier in these reasons, there is no relevant ambiguity in s 38 and s 39 of the Act, and hence no occasion for resort to the international obligations contained in the ICCPR or the UN Declaration arose. The primary judge was correct to so determine.

110 Further, it was a necessary part of this construction argument that the appellants demonstrate that the determinations of the Tribunal denied them their freedom to practise their religion. On the construction advocated by the appellants s 38 and s 39 did not allow that result. But the Tribunal found as a fact that the determinations it made, subject to certain conditions, would not result in preventing the appellants from exercising their religion. In order to succeed on this construction argument, the appellants therefore had to establish that the Tribunal erred in concluding that the grant of the mining leases on condition would not prevent the exercise of their religion. For this reason, the original Notices of Appeal challenged those findings by stating the challenges as particulars of the construction grounds of appeal. When the Amended Notices of Appeal were further amended in the course of the hearing of the appeal, the terms of these particulars where elevated to separate grounds of appeal, rather than as particulars of the construction ground. In that form they are considered in the following section of these reasons for judgment. We conclude in that section that those grounds cannot be sustained. In other words, it was open to the Tribunal to conclude that the grant of the mining leases on condition does not prevent the free exercise of religion practised by the appellants. This conclusion provides a further reason why the construction argument cannot succeed. Even if s 38 and s 39 are construed to conform with Australia’s international obligations to allow the appellants free exercise of their religious practices, the determinations do not prevent those practices.

Ground 2

111 Ground 2 of the Further Amended Notices of Appeal stated:

The Tribunal failed to take into account properly or at all material facts, namely:

Particulars

i. the obligation imposed on senior members of the Appellant in accordance with their religious beliefs, to find and collect the sacred stones (“Gandi”) [to use ochre from the ochre quarry] situated in the land and waters the subject of the Tribunal’s Determination for use in the religious initiation ceremonies performed by them each year [at the nearby Thalu];

ii. the relationship between the religious ceremonies performed by senior members of the Appellant’s society (which were the subject of uncontested evidence) and the traditional authority structures within that society, which depends upon the performance of those ceremonies as the principal means (pursuant to the religious beliefs of that society) for controlling the behaviour and actions of its members; and

iii. the impact of its determination, upon the said authority structures.

112 Ground 2(i) of the Amended Notice of Appeal in WAD 161 of 2009 stated that the Tribunal failed to take into account properly or at all the religious obligation imposed on senior Yindjibarndi in relation to the finding and collection of gandi.

113 The evidence accepted by the Tribunal established that the gandi had been found on the area of the proposed lease in the past. It also established that the appellants sang four ritual songs associated with the collection of the gandi. Had the appellants specified the locations where gandi are to be found the Tribunal said that it would have ensured that those locations where protected.

114 In oral submissions, the appellants took issue with the conclusion of the Tribunal in relation to gandi “that there is no evidence to suggest that there are particular ceremonies which must be conducted within the area of the proposed lease”. This argument focused on the ceremony said to accompany the collection of gandi, rather than the practice of collecting gandi.

115 At some points in the oral argument the error made by the Tribunal was said to be that it failed to consider the ritual singing ceremony related to the gandi. As the sentence quoted in the previous paragraph of these reasons shows, the argument was untenable. The Tribunal considered the issue of the conduct of ritual related to gandi on the area of the proposed lease, and concluded that there was no evidence that such ritual had to be conducted there.

116 At certain other times during the oral argument the error made by the Tribunal was said to be that, although the Tribunal considered the issue, it wrongly concluded that there was no evidence that ceremonies connected with gandi, as distinct from the collection of gandi, had to be conducted on the land.

117 An argument in this form was not put to the primary judge. The appellants did not raise it directly in the original Notice of Appeal, nor was it addressed in written submissions. The oral argument does not reflect Ground 2(i) in the Further Amended Notice of Appeal in WAD 161 of 2009. No leave to raise it for the first time on appeal was sought. There is thus no good reason why the matter should be considered for the first time on appeal. In any event, the appellants’ evidence contained in the two affidavits of Mr Woodley bear out the correctness of the Tribunal’s finding. Mr Woodley speaks of the physical collection of the gandi on the area of proposed lease M47/1413 but does not say that the ritual singing takes place at the time or place of collection.

Ground 2(i) of WAD 193 of 2010

118 The argument under this ground relates to the collection of ochre and mirrored the argument under ground 2(i) in appeal WAD 192 of 2010 in relation to gandi. It should be resolved in the same way.

119 In the course of its consideration under s 39(1)(a)(iv) of the Act the Tribunal described the evidence concerning the Maliya Thalu ceremony in which ochre collected on the proposed mining lease M47/1409 was used. It said at [40]:

In the first affidavit of Mr Woodley, he refers specifically to the Maliya Thalu which is located

‘not far from the area where FMG wants the Tenements’.

In his first affidavit it is said by Mr Woodley that ochre for these ceremonies is acquired from the quarry which is located within the area covered by M47/1409 (3.8). Mr Woodley further deposes that the ochre required for the Maliya Thalu ceremony must be acquired from the ochre quarry located within M47/1409 and as the grant of M47/1409 to the grantee party will inhibit or prevent the Yindjibarndi native title party from obtaining ochre from that place, the Yindjibarndi People will be unable to properly conduct the Maliya Thalu (3.10). The point is reiterated in paragraph 5.9 where Mr Woodley deposes to the fact that the Ganyjingarringunha (the river) runs through M47/1409 and that located within the area is an ochre quarry which is used each year for the Maliya Thalu ceremony and other Birdarra ceremonies.

120 Then at [41] the Tribunal concluded:

There are no specific references to ceremonies being conducted within M47/1409.

121 The Tribunal went on to say that the discussion which followed concerning the protection of sites of significance under s 39(1)(a)(v) of the Act was directly linked to the question of access for ceremonial purposes and “needs to be considered before I can reach any conclusions about the extent of the impact of the grant of the proposed lease”.

122 Then at [47] the Tribunal said:

[T]he evidence set out in relation to ceremonial activity, clearly indicates that there is an ochre quarry within the area which needs to be accessed in order to properly perform the Maliya Thalu in accordance with Yindjibarndi Law. If that ochre quarry had been precisely located in the evidence set out, I would be inclined to make it a condition that that quarry should not be interfered with without the consent of the Yindjibarndi native title party and that access should be ensured, except in circumstances where safety is imperilled.

123 The appellants argued that the conclusion that there were no specific references to ceremonies being conducted on proposed mining lease M47/1409 was wrong. There was evidence, so it was contended, that the extraction of ochre was itself a ritual or, alternatively, the extraction of ochre was an integral part of the ceremony in which it was used.

124 The same criticisms apply to the way the appellants raised this argument as are set out in [117]. But again there is no point in dwelling on those criticisms, substantial though they be, because the argument may be dealt with shortly.

125 The appellants did not point to any evidence which demonstrated that there was specific reference to ceremonies related to ochre being conducted on proposed mining lease M47/1409.